Abstract

In today’s evolving society, meaningful development cannot be fully realized without acknowledging the vital role of the electronics sector, especially as it functions within informal markets. These markets have become more than just centers of commerce; they serve as informal learning grounds where many young people acquire entrepreneurial skills, develop resilience, and find alternatives to social vices. For many, informal entrepreneurship is not just an option but a means of survival and self-empowerment. Despite their growing relevance, the link between the entrepreneurial abilities nurtured in these informal markets and actual business performance has not been adequately examined. This study, therefore, aimed to explore how informal electronics entrepreneurs in a developing economy navigate their environment, overcome challenges, and create wealth through vision, innovation, and calculated risk-taking. Anchored in institutional theory, the research employed a qualitative approach, using cluster, purposive, and simple random sampling to select participants from key informal business units. Interviews were conducted, transcribed, and analyzed using QSR NVivo 12, allowing for deep insight into the lived experiences of the entrepreneurs. Findings revealed that 78% of participants emphasized practical suggestions that aid informal business survival, such as customer-driven innovations, adaptive strategies, and avoiding confrontations with regulatory agencies. Key attributes such as foresight, adaptability, and risk management accounted for 66% of the variance in corporate success. Strategic and innovative approaches are enabling informal firms to endure and prosper, since 61% of respondents associated these competencies with organizational success. The new BSP framework, which integrates institutional and contingency theories, illustrates how informal enterprises endure by conforming to or opposing institutional pressures and adjusting to environmental changes. The results indicate that, when properly understood and supported, the informal electronics sector may develop sustainably. This study demonstrates that informal entrepreneurship is influenced by formal regulations, informal norms, and local enforcement mechanisms, therefore enhancing institutional theory and elucidating business behavior in developing nations. The Business Survival Paradigm [BSP] illustrates how informal enterprises navigate institutional obstacles to endure. It advocates for policies that integrate the official and informal sectors while fostering sustainable development. The paper advocates for ongoing market research to assist informal firms in remaining up-to-date. It implores authorities to acknowledge the innovative potential of the informal sector and to provide supportive frameworks for sustainable growth and formal transition where feasible.

1. Introduction

The rise in informal entrepreneurship in many economies, especially in developing countries, is the result of a complex combination of personal, social, political, and institutional variables [1]. As a result, there is a growing notion that employment is steadily falling in numerous formal sectors of the economy [2], which is a disturbing trend with far-reaching consequences for society’s general welfare. As official work possibilities grow limited, particularly among young and low-skilled populations, people are more drawn to entrepreneurial initiatives outside of the traditional economic system. This is consistent with the claims of [3] and the [4] who both note that the growth of informal companies is a responsive mechanism targeted at mitigating economic downturns. Ref. [5] supports this viewpoint, noting that informal entrepreneurship, although created out of need in many circumstances, has a high possibility of success owing to its adaptability. Informal entrepreneurs are often strongly immersed in the social fabric of their communities, tailoring their business operations to the people’s local needs and cultural expectations. This tight relationship with society allows them to stay adaptable and sensitive to market developments and customer behavior. As a result, informal economic activity emerges not just as a means of survival, but also as a potential contributor to economic growth.

From a broader perspective, the rise in informal entrepreneurship represents a type of social resilience. According to [6], sectors such as the informal electronics market are critical to human development and innovation, providing forums for practical learning, skill development, and knowledge sharing. This is consistent with the results of [7] whose empirical study demonstrates how such marketplaces serve as incubators for technical intelligence, especially among adolescents and underprivileged populations. However, the viability of these firms is not assured, especially in contexts characterized by weak institutions. Ref. [8] warned that institutional flaws such as uneven regulatory regulations, a lack of access to capital, and poor infrastructure might stymie the development and sustainability of informal businesses. These limits, rather than weakening entrepreneurs’ commitments, often encourage imaginative modifications that enable such enterprises to endure despite systemic inefficiencies.

Exploring the human motives for informal entrepreneurship reveals that they go beyond just economic distress. While conventional views characterize informal entrepreneurs as “necessity-driven”, emerging approaches, such as those offered by [9,10,11], show a wider motivational spectrum. Many people join the informal sector for a variety of reasons, including ambition, identification of opportunities, autonomy, and a desire for flexible work arrangements. The range of entrepreneurial motivations demonstrates that informal entrepreneurs do not have uniform aims. Ref. [12] corroborated this more nuanced approach, arguing that the surge in informal entrepreneurship is an intentional and strategic decision made by many people, driven by reasons other than poverty or unemployment. These include unhappiness with restrictive corporate settings, sociopolitical disenfranchisement, distrust of official institutions, and even cultural preferences for self-employment and community trading [13]. To summarize, informal entrepreneurship must be seen as a dynamic interaction of human impulses, institutional restrictions, and wider social shifts. As more people adopt informal entrepreneurial methods, they not only provide for themselves and their families, but also make a significant contribution to their communities’ economic and social well-being. This multifaceted knowledge transforms the narrative from one of marginalization and informality to one of innovation, relevance, and promise. Ref. [14] used empirical methodologies to verify the skills and predicted commercial success of entrepreneurs using a quantitative approach. This established a tight relationship between the two mentioned criteria. It also necessitates the confirmation of a stream of qualitative research methods by a thorough examination of nations deemed less developed.

Despite substantial discussion of entrepreneurship in formal settings, there is a huge vacuum in understanding how informal entrepreneurs, particularly in the electronics industry, use their abilities for survival, wealth accumulation, and greater societal impact.

Prior research [13,15,16] has identified the informal market as a training ground for aspiring entrepreneurs; however, few studies have examined the specific competencies that promote business success in these unregulated arenas, or how these practices significantly enhance youth empowerment and societal advancement [17]. This research fills the gap by investigating how informal entrepreneurs use their entrepreneurial talents, such as vision, creativity, and risk-taking, to not only survive but also thrive in challenging and unpredictable environments. The research, which is based on institutional theory and uses qualitative techniques to extract lessons from real-life events, investigates the often-overlooked ingenuity and adaptive strategies of informal participants.

The paper explains how the informal electronics market promotes youthful entrepreneurship and helps social stability by instilling critical entrepreneurial skills. It investigates the inventive ways that informal entrepreneurs manage regulatory limitations and adapt to the changing economic scene. The study emphasizes the need for constant market research in maintaining competitiveness, forecasting future trends, and assisting policymakers in adopting more flexible and supportive economic policies. Furthermore, ref. [18] showed that vision, innovation, and risk-taking have a major impact on personal wealth accumulation as well as overall corporate performance. Building on previous arguments, this study strengthens the informal market’s resilience and provides the groundwork for future research into policy alignment, innovation transfer, and formalization paths for these critical but often ignored firms.

Understanding the appropriate theoretical foundations is critical for developing strategies that successfully promote economic growth, especially in the face of insurmountable business risks [19,20]. Scholars’ efforts have resulted in the creation of this predicament, as they continue to investigate various new methods to generate money. As a result, the purpose of this research is to investigate entrepreneurial skills in order to establish the amount of money that informal entrepreneurs may generate.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Leveraging Institutional Theory

The use of institutional theory in informal entrepreneurship reveals a complicated and changing link between social structures and entrepreneurial behavior [21], especially considering the complex and dynamic nature of Nigeria’s informal sector. When applied to the Nigerian context, institutional theory, which traditionally explains the influence of formal rules and norms on behavior [22,23,24], reveals a more intricate understanding of how informal entrepreneurs skillfully navigate regulatory voids, socio-cultural expectations, and economic instability. The business environment in Nigeria, especially in large cities like Lagos, Aba, and Onitsha, is characterized by a weak formal institutional structure [25,26,27,28]. In such markets, it has been characterized by the presence of weak enforcement of property rights, bureaucratic red tape, corruption, inconsistent taxation, and an overstretched infrastructure system as they often create institutional voids that make formal business operations unattractive or even unviable [29]. In response, entrepreneurs have not opted out of the system out of rebellion but rather have opted into informal structures that are more predictable, locally responsive, and socially embedded [26,30]. This responsiveness to context is exactly where institutional theory becomes not just relevant but indispensable.

Risk-taking, in such settings, is not driven by abstract calculations or textbook logic. It is highly contextual and emotionally intelligent, molded by a survivalist mindset and guided by socio-cultural feedback loops. In many Nigerian communities, especially in the southwest and southeast commercial zones, risk-taking is seen as a sign of courage and ambition [28]. Young men are celebrated for venturing into the uncertain world of trade or apprenticeship, even without formal backing. This cultural perception becomes a cognitive institution, an internalized belief system that encourages informal entrepreneurs to experiment, even when the formal safety nets are missing [10,31]. Additionally, institutional theory helps to explain the widespread mimicry and adaptation observed among informal business owners [32]. A successful trader in the Alaba International Market, for example, quickly becomes a model for others. Within days, surrounding shops begin to adopt similar product lines, marketing strategies, and pricing models. This is institutional isomorphism in action; a response not to formal pressures, but to social and competitive pressures within a bounded yet dynamic informal system [33,34]. It becomes clear that institutional legitimacy in Nigeria’s informal economy is not derived from compliance with state agencies, but from social visibility, customer loyalty, and peer recognition.

The distinction between formal and informal institutions is especially critical in Nigeria’s context. Formal institutions are riddled with laws, licensing procedures, and tax policies [17]. They are often erratic or perceived as extractive rather than enabling. In contrast, informal institutions are associated with family ties, ethnic associations, trade unions, and religious networks. They are more dependable and accessible. These provide capital, manpower, and protection, and even dispute resolution mechanisms that the state fails to offer consistently [35,36]. Risk-taking, entrepreneurial vision, and strategic planning are all embedded in these localized, informal institutional matrices. In cities like Aba, for instance, entrepreneurs in the electronics and garment sectors frequently rely on Igbo apprenticeship systems, which are deeply rooted in communal trust, loyalty, and shared success [36]. This system functions almost like a parallel institution, complete with onboarding, mentoring, evaluation, and succession structures. Such alternative institutions fill the void left by government inefficiencies, and institutional theory must be stretched to acknowledge this legitimacy. This is not informality in the negative sense but entrepreneurial governance in motion.

The societal narratives of self-reliance and hustle culture also shape the vision of informal entrepreneurs [37]. In Nigeria, where youth unemployment remains persistently high [hovering above 40% in many states], the informal sector has become the default economic absorber [25]. Entrepreneurs do not only imagine better futures for themselves, but they create micro-pathways of survival for others, often building networks of apprentices, family staff, and loyal customers. Their vision is socially conditioned but economically consequential [38,39]. Yet, the lack of formal institutional support limits the scalability of these visions. Many informal entrepreneurs express frustrations about being unable to access formal credit, government incentives, or technical training simply because they lack a business registration number. This tension between vision and structural constraint further illustrates the complexity that institutional theory helps us unpack [39,40].

It is essential to recognize that institutional theory should not regard formal institutions as inherently superior. Researchers including [30,41] emphasize that informal institutions are not simply residual entities. They tend to be more functional, more trusted, and more resilient. In Nigeria, these institutions facilitate business continuity during periods of fuel scarcity, political unrest, currency devaluation, and supply chain disruptions. This demonstrates that informality constitutes a distinct form of order rather than disorder [16]. The application of institutional theory to Nigeria’s informal entrepreneurship illustrates a complex, adaptive, and socially embedded entrepreneurial ecosystem. Businesses function within a complex network of informal institutions that govern behavior, influence risk-taking, and establish legitimacy. This theory must evolve to acknowledge the creative, strategic, and survivalist logic of informal enterprises as valid systems rather than aberrations to be formalized. These enterprises provide significant insights into economic resilience, community-based capitalism, and grassroots innovation.

Institutional pressures can create challenges by generating voids, which render businesses susceptible to risks such as exploitation and market volatility [42]. Informal entrepreneurs respond to challenges by employing innovative strategies for resource management and risk mitigation. The absence of formal recognition limits growth opportunities, thereby enhancing the importance of informal institutions, which provide alternative mechanisms for resource mobilization and risk management [30,43,44,45,46,47,48].

The interaction between formal and informal institutions, particularly in contexts with institutional gaps, significantly influences the relationship among institutional theory, risk-taking, and vision in informal businesses. Social norms and cognitive beliefs frequently compensate for the shortcomings of institutional frameworks, significantly influencing entrepreneurs’ perceptions and responses to risk. The formulation of effective strategies for sustained economic success relies on a comprehension of these theoretical foundations, especially in contexts characterized by persistent business uncertainty. Institutional theory provides a valuable framework for analyzing the survival and strategic approaches of informal enterprises. Informal entrepreneurs operating within systems characterized by unreliable or absent formal institutions often refine their vision and tenacity out of necessity. The interaction between institutional constraints and entrepreneurial creativity indicates a viable alternative pathway to economic growth, one defined by evidence of wealth creation and successful adaptation. A greater knowledge of the interplay between formal and informal institutions, molded by prevalent norms and attitudes, should help to guide more focused support systems for these entrepreneurs.

Building on this basis, it is crucial to take into account the environmental concerns that affect the informal business sector even more.

2.2. Issue Description

The theoretical scenario has shed light on the entrepreneurial mindset in informal markets; nonetheless, earlier studies have highlighted the need for external environmental elements in affecting business results. Small businesses’ success and growth depend on infrastructure, employment security, access to financing, availability of venture opportunities [14,49]. Their approach also emphasizes the need to change the informal structure by including it more intentionally with supportive systems. These talks highlight the need for not just knowing the internal capabilities of informal entrepreneurs but also handling the outside factors either supporting or improving their company paths.

The study of [6] was able to conceptualize the reforms that can be placed into the business practice system of an informal entrepreneur using the potential framework. The study of [29] posits that brands of products or services have been used to identify what businesses are about. This was the notion that led to the portrayal of economic growth in society via business engagement. The perception of [50] further portrayed a possible problem steaming from taking risks and being creative because of the modus operandi of the informal business sector operations. The business settings of the informal enterprise had parameters identified by [51] and this collaborates the basis of business operations as a way to attain wealth. In all of these, it was also found that in the formal business setting, the identified replication of the study in qualitative engagement in a developing society was missing in identified scholarly works [52,53,54,55,56].

It must be stated that the absence of a clearly defined aim for unregistered businesses has led to the challenges of extending business operations and maintaining their counterparts in the formalized business structure. This posits that formalized businesses are noted to continuously expand in the gathering of more business outlets as a reflection of wealth attainment [30,38,44,57,58] but the likewise could not be propounded for the informal business.

Hitherto, studies linked to the consideration of the influence of a vision’s impact on informal enterprises resulted in a limited knowledge of effective techniques to assist the success of informal entrepreneurs. It is on this premise that [9] claims that the consequence of this imbalance is that the informal sector continually experiences hitches in full economic participation. Nonetheless, the effect of risk-taking actions on innovation outcomes is difficult for businesses to understand as the required data to enable the development of effective strategies is limited concerning developing nations. It is believed that the attainment of creativity is achieved by purposeful risk-taking, and this is greatly hindered by the lack of expertise in this subject [59].

The ability of an individual to recognize opportunities in the informal economy and search for a major component in the environment known as the risk element while turning it into a profitable venture is what earns the phrase informal entrepreneurs [34]. This was earlier stated in the Porter and Lawler model when matching the abilities and traits of individuals to the requirements of the available career by putting the right person in the right career [42]. To this end, an individual who is visionary, innovative, and a risk-taker may be eager to start a business in an informal market, despite the visible limitations. The requiem of strategies designed to restrict the influx of informal entrepreneurs calls for concern as its designed limitation serves as a springboard that motivates the development of engaged informal entrepreneurs, creating a perception that the relevance of entrepreneurial ability could waylay the path of wealth creation possibilities. This study thus flourishes on the will to emphasize the wealth attainment possibility ingrained in the entrepreneurial skills of those working in the informal market. At its heart, it aims to create a significant link between the inclinations for wealth generation and the particular skill sets, intuition, and adaptive behaviors that define informal entrepreneurs. The research emphasizes the sometimes neglected contributions of small entrepreneurs to more general economic growth by doing so, particularly in settings where institutional support systems are either lacking or non-existent.

2.3. The Concept of Informal Entrepreneurship in a Developing Nation

Grasping this link calls for a thorough examination of the essence of informal entrepreneurship, especially with developing countries. Around the world, entrepreneurship has been generally acknowledged as a major engine of job creation, innovation, and economic development [60,61]. But in poor nations, entrepreneurship sometimes assumes a different shape, one driven by need, limited resources, and institutional disparities. Informal entrepreneurship not only responds to poverty and unemployment but also provides a venue for innovation, resilience, and wealth generation in its own right.

It must be noted that certain criteria are expected to be in place for an intending practicing entrepreneur. The criteria include psychological traits, education, the entrepreneur’s desire, among other elements [62]. Ref. [35] argued that the primary goal of all countries is to develop and maintain their population size and economic power. This is dependent on identifying possibilities that may be used by resilient and innovative entrepreneurs. To accomplish this goal, all countries must have a conducive climate that promotes the success of entrepreneurs in their business pursuits [29,63]. This will result in a multiplier impact on the nation’s economic growth via the advancement of a commercial economy. A feat, such as this, can be attained by factoring in the practicing medium of such entrepreneurial acts [44], and the informal sector in a developing nation such as Nigeria is not excused. Therefore, the required understanding of entrepreneurship practiced in Nigeria’s informal sector cannot be fully captured into economic gain for the nation if the socio-cultural perspective is excused.

2.4. Social–Cultural Perspective

The majority of the research on entrepreneurship have focused on either the actions of individual entrepreneurs or the processes of startups [54,64,65,66,67]. In recent times, the pursuit of new economic ventures by individuals, also known as entrepreneurial activity, has been on a spike. This comes from the point of a dwindling reduction in big companies via the efficient combination of resources to combinations of entrepreneurs. The expected benefit of these combined entrepreneurs is the attainment of economic benefits to the immediate society before the larger environment [68,69,70]. There tends to be a cultural adoption of business engagement in the community where it is practiced. This affirms that a different approach culminating from the sociological concept as put forward by [30] and stated by [33] tends to be the silent unraveling of business disposition in respective locations using informal tactics. This indicates that society, supported by culture, influences the development of entrepreneurs and methods of economic participation, regardless of an established framework. This characteristic is directly associated with the predominance of informal entrepreneurship in developing countries, especially in Nigeria. In this context, understanding the dynamics of informality in entrepreneurship requires a thorough examination of the informal sector, particularly in areas where official institutions and rules are often absent or unattainable. The Nigerian informal sector is a prolific arena for economic activity, sustaining millions despite operating within a mostly uncontrolled framework.

2.5. The Nigerian Informal Sector

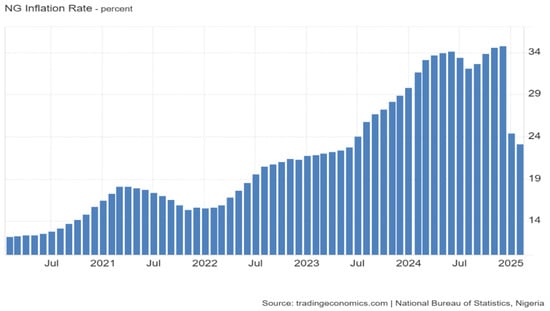

The informal sector in Nigeria consists of economic activities that, while legal, function outside the regulatory framework of governmental agencies. These enterprises frequently remain unregistered, lack oversight, and are omitted from formal economic planning, tax compliance, and statistical records. The lack of formal recognition is attributed to various factors, including bureaucratic challenges, regulatory barriers, and the need for adaptable business models that can thrive despite these constraints [8,33,55,71]. The informal sector in Nigeria plays a crucial role in employment generation and entrepreneurship promotion, significantly influencing the overall economy while functioning outside traditional regulatory frameworks. The referred “inform sector” does not capture hidden activities that are clandestinely performed in the informal pathways based on its characterized criminal structure. On this note, the informal sector refers to business activities that are carried out to relieve the burden of the formal sector with unqualified requirements for practice [72]. Ref. [7] made it known that the informal sector comes with a 58% contribution to the total Nigeria economy as of 2018. This makes it a great contributor to the Nigerian economy. The literature of [10,73] recaptured the fact that on average, the informal sector was estimated to be 38% for transitioning countries, while developing nations, such as Nigeria, have a whooping number of 41%. This projection must have been surpassed with the current hyperinflation in 2024, as shown in Table 1 and displayed in Figure 1 [34].

Table 1.

Inflation trends from year 2020 to 2025.

Figure 1.

Inflation trends from 2020 to 2025. Source: National Bureau of Statistics, Nigeria (https://tradingeconomics.com/nigeria/inflation-cpi, accessed on 16 March 2024).

The perception of informality in entrepreneurship stems from the need to fully grasp both the concept and practice of informality within the economy. This understanding presents a significant challenge for statisticians, social scientists, development practitioners, and policymakers, especially given the crucial role the informal sector plays in the lives of millions of business owners. The informal sector is often described as transient, with entrepreneurs constantly navigating an evolving landscape [72,73]. This fluidity makes it difficult to pin down exact measures and characteristics, yet it remains essential that the informal sector be studied with the utmost priority. Not only does it provide a livelihood for those affected by unemployment, but it also helps mitigate social vices that might otherwise have exacerbated social problems, despite criticisms that it may also contribute to such issues.

2.6. Entrepreneurial Ability in Electronics Informal Market

The existence of informal markets, especially within the electronics sector, is directly related to the economic benefits they provide. These markets represent dynamic environments in which formal and informal entrepreneurs coexist, characterized by significant financial transactions and extensive goods exchange [74]. The markets chosen for this study exemplify economic ecosystems in which patronage and commodity circulation are central to entrepreneurs’ livelihoods. In these contexts, entrepreneurial skills are essential, facilitating adaptation, innovation, and survival in the face of challenges presented by a predominantly unregulated environment [15]. Recognizing the entrepreneurial traits that flourish in this context is crucial for understanding the role of informal enterprises in personal survival and their contribution to the national economy. It must be noted that [75] stated that such markets are regarded with the fame of irregularities and insincerity. Previous research indicates that informal entrepreneurs are involved in business activities which have emerged from the market as they were deemed sufficient for self-sustainability, amongst other needs [29,33]. The dynamic nature of the market results from the products that are deemed of continuous relevance by the informal entrepreneurs. They have been linked with respective customers who see the sold services/products as cheap and relatively subsidized. In other words, this attribute of conviction comes from the informal entrepreneurs’ displayed abilities [76]. The literature from [50,77,78] made it known that the attributes of informal entrepreneurs decide the survival and running of their businesses, as they are known to go along with their pursuits of new economic endeavors. These business acts range from the necessity of the inculcation of self-employment to the creation of big organizations with incremental monetary gains as the target. This indicates the tendency of the involved business to perform well and serve as encouragement for continuity.

2.7. Business Performance

The activities of entrepreneurs in the informal sectors call for deep-seated reasons for the influx into it to be studied [37,43,79,80,81]. Possibly, there must be a rationale for the increase in the activities occurring in the informal sector despite the continuous creation of diverse governmental instruments that have been made to exist with the mindset of restriction or transitioning viable business activities in the nation’s formal sector [82]. Ref. [83] stated that the influx of participation in the informal sector comes with profit linked to business performance. This is coupled with high annual sales, employment, and productivity growth when compared with businesses that are registered in the same location when compared with the latter as there seem to be ongoing gray activities [82,84]. This is believed to transit to the creation of wealth achieved in the market.

2.8. Wealth Creation

With the yearning for wealth in place, the need for an opportunity to be identified must be a prerequisite and this can only be established by wealth creation tendencies by employing the right strategies [66]. The postulation by [73] claims that the challenge lies in differentiating between necessity entrepreneurs and opportunity entrepreneurs. Necessity entrepreneurs can be referred to as individuals who are driven into entrepreneurship because they have no other options or are dissatisfied with existing alternatives. This happens while they are opportunity entrepreneurs, willing to pursue entrepreneurship [73,78]. Moreover, the studies conducted by [85,86] investigated the motivations of formal entrepreneurs, and they found out that the differentiation between opportunity-driven and necessity-driven motives does not exist. Their results suggest that both might coexist at the same time. Furthermore, their research suggests that the balance between these drives might change with time.

Often reflecting a significant shift in their approach and mindset, entrepreneurs tend to migrate from need-driven desires to opportunity-driven ones [41,87]. Most economies, according to this study, operate under a push–pull dynamic in which need and opportunity drive entrepreneurial activity. Ongoing and fluctuating participation in informal entrepreneurship shows the dual impact of both men and women engaging in these businesses to attain financial security. Informal entrepreneurship is sustained by the balance between need and opportunity, hence highlighting its vital role in personal and economic success.

2.9. Opportunities for Recognition and Wealth Creation

An essential aspect enabling entrepreneurs to go beyond basic survival is the capacity to identify and exploit possibilities within their surroundings. This capability is essential for transcending poverty and surpassing fundamental needs [88]. The informal sector is crucial in this process, providing pathways for economic advancement, particularly in developing nations where conventional work options are limited. The informal sector serves as a crucial support system for people marginalized from the official labor market, facilitating wealth creation and the development of improved futures. This highlights the need to acknowledge the prospects inside the informal sector, not just for subsistence but also for comprehensive economic advancement and development. Consequently, it is said that the informal sector provides a buffer for those who are anticipated to possess organized financial capabilities and partake in vices, since they may struggle to meet their basic necessities.

Ref. [88] concentrated on the Oyo Kingdom. They examined its prevalent typologies and reflected that the IEOs [International Entrepreneurial Orientations], characterized by communal effort, reduced the cost prices of products, coupled with low patronage recorded as the major challenge of IEOs. This resulted from the frequent migration of young people to other cities for livelihood due to the slight industrial development in the area. It is on this note that the discovered problem results in a certified need for migration as it hinges on the identification of a viable market.

Ref. [89] promoted the possibility of diverse differences occurring in the steps of the transformation of the knowledge economy [KE] in countries like South Korea, Singapore, and Finland, which can be characterized by several key factors. From the author’s point of view, in as much as the transformation was gradual and continuous, rather than sudden or abrupt, it was welcomed. Secondly, it must be driven by a combination of top-down and bottom-up initiatives. This transcends the need for both policymakers and institutions to be in active participation in shaping the transformation that will imbibe individuals and organizations. Ref. [89] agreed that a pivotal stance emerges from effective communication, and this is a critical component of the transformation process.

All stakeholders, including citizens, employees, employers, private and public sectors, judiciary, legislation, security, and safety agencies, as well as neighboring countries, allies, and partners, are involved in the communication efforts that resulted in a successful economic climate [90]. With all these in place, the need for an opportunity to be in place through identification must be a prerequisite, which is further established by wealth creation and success attained by employing the rightful strategies needed [10,91]. This was initially brought about by [58]’s stand on the difficulty experienced in the differentiation emanating from necessity entrepreneurs [a result of choices, which are absent or unsatisfactory] and “opportunity” entrepreneurs [doing so out of choice] [58,92].

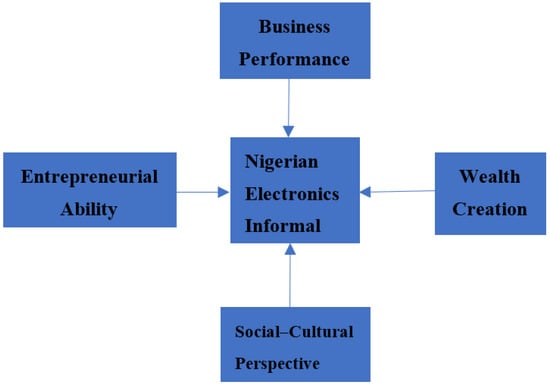

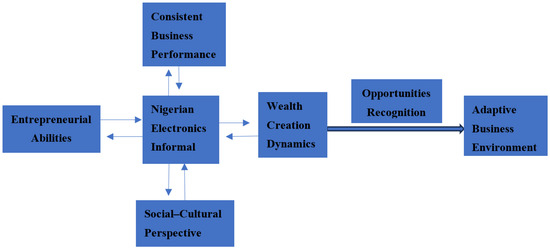

In addition to the pioneering studies on informal entrepreneurs’ motives, [74,86] questioned the separateness of opportunity and necessity drivers on the argument that both can be co-present. This becomes a shift in the need for a balance of these entrepreneurial motives over time for informal business operations. This comes from a pressing necessity to be opportunity-driven [41,87]. However, the study concludes that in most economies, it is a reflection of the pull and push effect, which is a reflection of necessity and opportunity drivers when explaining their rationale for participating in informal entrepreneurship either for men or women. Building on this premise, there is a pressing need to establish a qualitative framework for understanding how developing societies can foster entrepreneurial growth, particularly in the context of wealth creation through opportunity detection. The understanding of the above writeup is better displayed with the conceptualized schematic framework shown in Figure 2 below. This is where the role of entrepreneurial ability becomes central, as it enables individuals to recognize and act upon opportunities that can lead to economic advancement.

Figure 2.

A conceptual framework of the institutionalized structure of the informal sector of perceived entrepreneurial abilities and business performance for the Business Survival Paradigm. Source: Designed by the author based on study conceptualization, 2025.

2.10. Wealth-Creating Entrepreneurial Strategies: The Contingency Escape Route

To further contextualize the enduring influence of entrepreneurial capability on company success, it is crucial to amalgamate institutional theory with contingency theory [19]. Institutional theory elucidates the institutions and norms influencing entrepreneurial conduct, while contingency theory presents a framework that considers the many contexts in which entrepreneurs function [93]. This combination facilitates a more thorough comprehension of how wealth acquisition may be realized. The contingency approach highlights that entrepreneurial practices successful in one setting may need modification in another. By acknowledging and adapting to the evolving dynamics of the business environment, entrepreneurs may more effectively address obstacles and capitalize on opportunities, hence fostering wealth creation and enduring economic success [10].

This is premised on the standpoint of [94] adopting a strategic fit to enact the environmental and organizational contingencies in predicting the changes for business performance via adopting dynamic strategies. While the study of [94] was on formalized institutions, this study is premised on informal business operations. Furthermore, the stance of Robinson and McDougall in their special issues, as depicted by [78], showed that the contingency theory and strategic fit were relevant to business creation. This was further explained in the terms that the institution of industrial organization economics, strategic management, and the practice of entrepreneurship were encumbered by premised environmental factors, in the form of market barriers, leading to the possibility of new businesses being affected. Investigations from different authors have shown that value creation for businesses come as a strand of four drivers and they are entwined as efficiency, complementarity, lock-in, and novelty [95,96]. The above concept is adopted with the notion of having the understanding that the business in the trade-in of the informal sector is expected to follow the sequence, with the understanding that the following occurs:

- Efficiency is made in the way customers are treated when they patronize the informal business.

- The business engagement is carried out with the mindset of having complementary services and products, thereby producing the pathways of bundle patronization over time.

- In the need to retain customers, strong incentives are utilized with the notion of having repeat business.

- Uniqueness starts from the services rendered being novel services that previously had unrecognizable value.

The findings from [97] made it clear that innovative businesses are integrating their business operations, and this can be related to informal businesses, though the research was for internet-related businesses [96]. It is on this basis that the four concepts must be entrenched into a business to arrive at the value creation ability.

According to [97], the primary objective of an entrepreneur is to generate profit while simultaneously safeguarding oneself from any possible problems that may arise. Nonetheless, ref. [56] posited that creating wealth via entrepreneurship is not about being wealthy quickly, which may be a one-time transaction; rather, it is about making the most of possibilities while minimizing risks to achieve success despite disappointments. To better understand the stratagem, the adoption from [97] is re-enacted as the following strategies are placed forward and listed below:

- Keep an eye out for potential changes in advance.

- Adaptability in terms of strategy.

- Establishing efficient strategies for the distribution of resources for operations that have been consolidated.

- Revolutionary ideas and the expansion of the company.

- Employing prudent financial judgment and taking precautions to reduce hazards.

There are several alternative strategies and approaches for quitting the firm. To put it another way, ref. [9] made it known that individuals may acquire the knowledge necessary to become more financially successful by engaging in the practice of proactive opportunity identification. Notably, inexperienced business owners may benefit from the irrationality that exists in a chaotic environment since it works in their favor [98]. This acknowledges that informal entrepreneurs who are skilled in their craft can evaluate the market, predict the preferences of their customers, and see trends that others may miss. The ability to foresee this aspect in the business environment places forward the term “business opportunity” [99].

Putting these results into the act of preparedness to grasp opportunities before competitors do is what breeds the acts of being proactive in the involved entrepreneur approach. Ref. [96] discussed the possibility of a consequence from the agility hypothesis, placing it on the inflexible plans that premise the potential to become outmoded in a fast-paced 21st century business environment. The ability to alter and modify one’s strategy in response to new information or difficulties should be a key concern for every informal entrepreneur in the use of said entrepreneurial ability to obtain wealth. Furthermore, the use of strategic agility, which is the ability to change and adjust the business-related plan, is necessary for having a modified plan that takes into consideration unforeseen circumstances [9,50,98,100,101]. The attainment of this is what brings about continuous wealth creation ability and independent profit attainment without the influx of contribution from external environment forces.

The practice of entrepreneurship is placed on the notion of knowledge attainment as depicted by [35]. This is explored for the maximization of capital. It is this that makes the difference in the use of time, human, and financial resources. Further evidence is shown in the reduced expenses and planned savings which can upend the survival instinct when the plan goes awry. The position of [46] makes it known that the use of networks and agreements is required to finetune the optimization of resources that will result in advantages.

When it comes to overcoming obstacles, successful informal business owners develop methods, processes, and structures that are resilient by fortifying their plans as a means of accomplishing this goal, using the existing supply business chains [29,99]. This helps the business investments improve operational efficiency and devise backup plans to ensure continuous functioning even in the face of calamitous events.

In the case of informal entrepreneurs adopting the urge to reduce their dependence on any one source of income by diversifying their revenue sources, the sales of new goods or services or by entering new markets is the mode of operation. This tends to create the modus operandi. Refs. [73,89] claimed that businesses are better equipped to withstand fluctuations in the market as a result of innovation and diversity. This contributes to the expansion of the business. In retrospect, it can be seen as the use of visioneering, an aspect of entrepreneurial ability.

Using [82]’s adoption, the process of accumulating wealth involves not only the acquisition of financial resources but also the assurance of their safety. This results in the essential component of practicing financial discipline to enhance risk mitigation. This is from the point of noting that financial acumen may be shown by entrepreneurs in several ways, including the capacity to handle debt responsibly, maintain a substantial cash reserve, and safeguard oneself against the possibility of incurring financial losses [102,103,104]. It is vital to use risk mitigation strategies, such as diversifying assets or hedging, against market dynamics to ensure that the business always survives.

The use of financial ability is believed to create a climate of endurance while having the right to weather through difficult times without jeopardizing its prospects for future success [9]. This requires the prospect of having foresight while the imposed barriers are made to thrive. Establishing an aspect of the emergency escape route enacts a reliable backup plan with evacuation protocol in place. This is in addition to the notion that businesses might be negatively impacted by a wide range of risks, including natural catastrophes and economic downturns [104]. Therefore, it is essential to make preparations for these potential outcomes via the use of contingency planning, though major techniques might end up not being successful [105].

Invariably, the attainment of wealth creation comes from the ability to spur value creation [43], and this can be sourced from the innate action of engaging in the use of cultural entrepreneurship in times of dispersal to make ends meet [105]. This pathway is what triggers the use of a contingency plan to arrive at the least expected mode of business survival instinct. On this, a contingency, which comes from the unplanned pathway of survival, becomes the paradigm of the day.

Considering the informal entrepreneurial practice, it can be deduced that there is a necessity for a crack that they [informal entrepreneurs] must relate and respond to on an impromptu basis on the path to good performance of their businesses. This makes the constitution theory adoption to serve as a foundation of bracing the institutional theory of entrepreneurial abilities to lead to the required business performance from the enacted survivals paradigms of the businesses.

3. Methodology

The study utilized a cross-sectional strategy to collect and evaluate data from informal electronics entrepreneurs in South West Nigeria at a certain period. This method was chosen because it enables the investigation of entrepreneurial capability’s influence on wealth generation, business performance over time, and the understanding of the informal electronics sector. Mixing cluster, purposive, and snowball selection ensures a complete and representative study of the research population, despite its unregistered and transitory nature.

3.1. Study Area

The study focused on informal entrepreneurs in South West Nigeria who specialized in electronics products. The population studied made it difficult to ascertain an accurate summative single figure. This is premised on the characterization of being unregistered business operators. Further investigations were conducted to obtain an estimate of the population using the respective heads of the business associations in the various markets, but they were unwilling to share the information. With this view, the visible proposition of these locations characterized the informal business owners as vast though not officially registered but always on the move. However, this study considered all informal electronic entrepreneurs operating in the markets listed below using cluster sampling.

The chosen markets are as follows: the Computer Village, situated in Ikeja, a vibrant district of Lagos, and Fagbese Adenle located in Osogbo, inside the state of Osun. The Ayo Fayose Modern Market is located in Ado-Ekiti, inside Ekiti State, whereas the Olukayode Shopping Complex is situated in Akure, a city within Ondo State. Okelewo Market is located in Abeokuta, the capital city of Ogun State, while the Bola Ige International Market is situated in Ibadan, the capital city of Oyo State. This study focused on the influence of entrepreneurial ability on wealth creation in the informal sector while dissecting the possible linkage along the lines of business performance in the electronics market. The electronic markets located in the southwestern states of Nigeria were chosen for the study because of their high level of patronization compared to other markets in the selected locations. The justification for the selected markets was based on the high-level requirements of information technology and the difficulty in income realization by the government.

In the discussion of electronics sales and repairs. employment generation tendencies that occur in Computer Village, Ikeja, alongside other listed markets as listed above, serve as the hub for electronics procurement and services. It must be noted that these markets are regarded as the hub for the purchase and services of electronics products, especially home appliances in Nigeria and West Africa [3]. Concurrently, Computer Village, Ikeja, is regarded as the largest ICT accessories and services market in Africa [53,80].

3.2. Sampling

With the geographical location of the study as southwestern Nigeria, the activities of the informal electronics entrepreneurs were determined as the main study epicenter with a focus on their ability to sell and the rendering of services of electronics products. It is possible that other products, which were not electronics, were being sold, but the majority of the entrepreneurs involved in said locations focused on electronic products. The research adopted cluster, purposive, and simple sampling. They were adopted for the study because the investigation was not quantitative as it aimed at discovering and explaining the participants’ real-life cases and experiences from the selected units of analysis at the single level [informal business entrepreneur]. This attempt was focused on providing the researcher with research evaluation based on the research objective instead of the established generalization or conceptual existence arguments [49,64,95,97]. The purposive sample was used to choose an entrepreneur who worked as an informal electronics entrepreneur, has been in the market for over a year, and mostly participated in electronic business. Conversely, the cluster sampling method was derived from the distribution of the population over seven distinct electronics marketplaces in the southwest region. The researcher used the clustering sampling technique to choose market regions where respondents were known to operate in big clusters. The choice was made using the purposive sampling approach to help the researcher locate informal entrepreneurs who were motivated to attain the given aims.

Complimenting this research, the use of snowballing was adopted with the idea that the initially selected interviewees allowed me to interact with other identified key participants in the markets. I had to make use of these strategies as I observed that they [identified informal entrepreneurs] were quite difficult to interact with based on the demands of the market. Using the understanding of [58], these are the major markets identified in South West Nigeria that have large cluster concerning electronics sales and repairs.

Ref. [2]’s opinion on the adoption of a cross-sectional design was adopted as a strong foundation for the study’s methodology from its collection and investigation of all measurement variables at point in time. Selection of the research locations was based on the six markets having varying degrees of saturation with informal electronics entrepreneurs. This served as the basis for this study. Based on the recommendations of [54,69], the study employed a mix of snowball and link-tracing population estimate methodologies to provide an accurate assessment of the population to conduct effective interviews. It turned out that this hybrid strategy, which is also known as the quasi-percentile method, helped reach the targeted population.

A gatekeeper, someone who has attained power and influence inside these markets, was included [97]. Such power is mainly with making an influence to obtain information at little or no hard task. Therefore, in this study, the gatekeepers were utilized to acquire truthful replies from the determined key participants [13,106]. When considering the hidden nature of these enterprises and the difficulties in acquiring trustworthy information, it was determined that this was required. Periodic observations were also carried out on three distinct days to arrive at an estimate of the number of informal entrepreneurs present at each market. These observations included a busy Saturday as well as a Thursday, which is the environmental day for the markets. Based on these observations, it was discovered that there were consistent alterations and inconsistencies in the manner in which the companies worked at certain places, such as physical storefronts. It was essential to have this knowledge to comprehend the dynamics of informal entrepreneurship in certain marketplaces.

To conduct an interview, ref. [38] posited that its occurrence is premised on the arrival of twenty interviews, especially when it is to aid or support the research from gathering the initial theoretical framework. To this end, five interviews were strategically employed in every location, aside from Lagos State, owing to its population size. This was designed to reflect each strategic location in the markets. Government-recognized streets in the market were chosen for interviewee selection. The number of selected interviewees in the respective locations was numerically placed, as depicted in Table 2, while their characteristics are displayed in Table 3 below.

Table 2.

Market distribution of conducted sampled interviews.

Table 3.

Distribution of conducted interview on business location codification.

3.3. Utilized Instruments

The study adopted both unstructured and semi-structured interviews which were carried out once. The unstructured interview aimed to have a broader view of the participant’s knowledge of the market before the participation of key participants in the market. This establishes the knowledge of the interviewees as being in line with the research objective of the study after obtaining the knowledge of the concept of the informal electronics market. Furthermore, the adopted theoretical underpinning of the study serves as an inductive method that resulted in thematic coding, in which the transcribed codes were conscripted. This was initially conducted with [49]’s notion of ensuring the stabilization of a theory. Therefore, with this study, the testing of the institutional theory was brought forward via theoretical saturation, as the description enacted by [57] is laid forward on grounded theory.

The semi-structured data aided in understanding the interviewees’ views while following the opinion of [13]; the generated codes were based on the interviewees’ narratives.

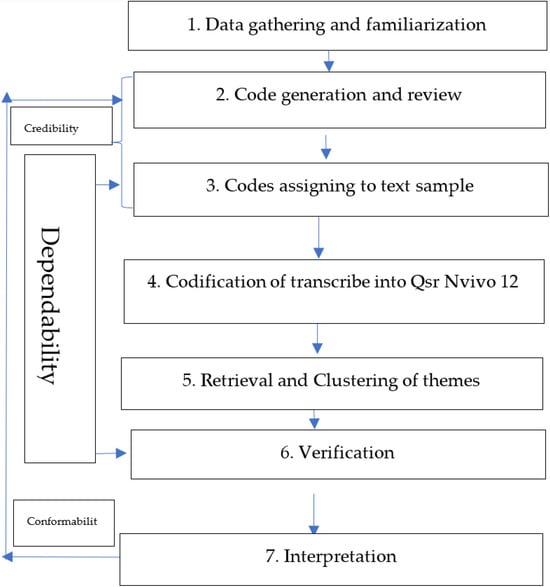

3.4. Research Data

A structured interview was used to capture the informal entrepreneurs’ perception of the performance achieved based on the initial motivation obtained to conduct business in the informal business sector. Five respondents were selected from each market [consisting solely of electronic business owners who were informal entrepreneurs and were known to have been in that market for five or more years] for the interview; 11 interviews were conducted due to the population size. Based on [70], the identification was made to be on the significant norms, ideas, and conceptualization compared the semantic levels that view data meaning at a superficial level. Structured entrepreneurs were interviewed for the structured interview. This was conducted in all selected markets. QSR Nvivo software (Nvivo 12R2) was used to analyze the transcripts with the notion of the adoption of deductive and inductive mechanisms from the direction given by [15]. This research was gathered via the interview procedure using the steps illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Adapted steps taken for data analysis. Source: [95].

The gathering of data for the generation of codes from the study theory was in line with the review process in rewriting the codes on the application of data to the code in steps 1–3. This ensured that the initial code was credible for further evaluation analysis. The data were entered in stage four into the QSR Nvivo. The use of the software in this analysis further confirmed the initial codes enacted in stages 1–3. This led to theme clustering and verification against the stance taken from the semantics level, looking at the superficial meaning of the data alone. The aversion of this brought about the identification of the significant norms, ideas, and conceptualization from the initial coding exercise [70].

Based on the study’s reliability testing, the intercoder reliability was used to determine the association of the generated codes with the transcribed data. According to [107], a 70% benchmark was expected, while for this study, 86% was found to be in sync with its agreement. It must be noted that [58] posited in their argument that reliability revalidation is better suited using judges, and in the case of this study, two judges confirmed they evaluated the quotes extracted from the study against the theme generated. They further validated the reliability obtained using the cross-case analysis of supporting evidence as above.

The data process was a step-by-step approach that reflected the analyzed reported data [dependability check] in line with the use of conformability checks in examining the data linked to its interpretation. The guide below was in sync with the description of the codes, which were in line with aiding the data codification. The data are not available in this research but can be provided upon request [both the transcript and audio files].

3.5. Ethical Considerations

Throughout the research project, the utilized information provided by the participants remained anonymous. The researcher refrained from asking or making remarks that might be seen as misleading. This was part of the research protocol for the study. The owners of the chosen informal businesses granted the researcher’s ethics authorization. A communication link was sent out to the participants, through which they were provided with information about the purpose and justification for their participation in the study, as well as the likelihood that their data would be shared with others. While the researcher was producing the report utilized in the study, the expectations of the market were met by the agreed maintenance of maintaining the participant anonymity. This was by the gatekeeper who was concerned about the personal safety of the market participants. Additionally, the researcher represented each market with numbered tags that were identifiable. According to the Declaration of Helsinki, the interview guide used to collect data was subjected to the anticipated local legislation and institutional requirements. This study took place in an informal setting where verbal consent is considered appropriate and sufficient. Thus, these respondents were approached in their respective communal spaces with the understanding that obtaining written consent might have been cumbersome or intrusive. It must be noted that based on cultural contexts, the respondents considered verbal agreements as binding as written ones; they felt more comfortable giving consent verbally. Every step of the research process was broken out for the participants, and they were allowed to withdraw from the study if they felt they were no longer comfortable. The confidentiality and security of the data were preserved since the data obtained were anonymized, inputted, and stored in a secure electronic platform. The interview lasted from about 35 min to 1 h. The summary of the interviewees’ profiles and summary is reflected in Table 2 and Table 3 above.

4. Presentation and Analysis of the Results

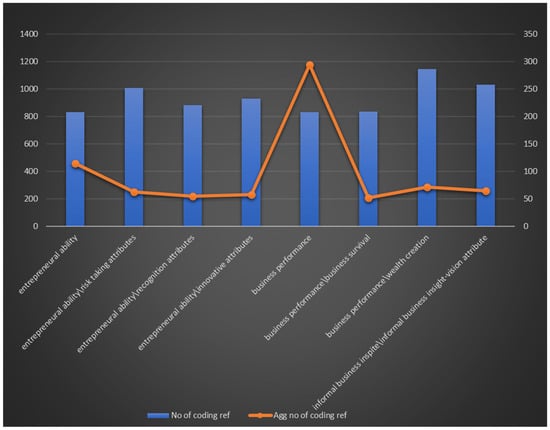

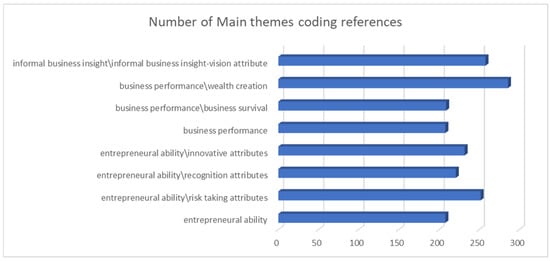

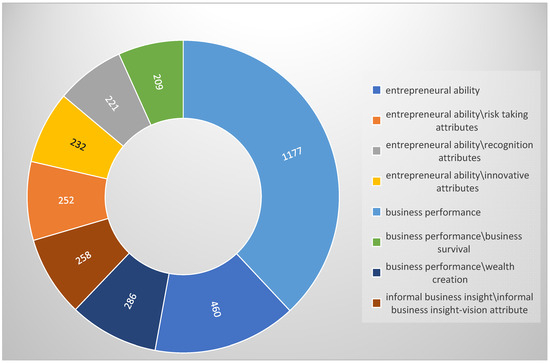

Thirty-six informal entrepreneurs were interviewed to relate their perceptions of how and why they decided to operate the informal electronics market. Each interviewee represents one case study, and the analysis cuts across the six states in the southwest. This led to three themes related to entrepreneurial ability and business performance of informal entrepreneurs in the electronics market. Using the NVivo software (12R2) for thematic analysis, the identification, analysis, and reporting patterns within the data were made from unstructured interviews [audio and video translated into transcripts] by finding themes and extracting meaning. The main themes that emerged from the process were business performance, entrepreneurial ability, and informal business survival. These themes were relatable to the generated number of codes during the analysis and represented in Table 4, which depicts the number of main themes in line with the coding references. Interviewees were coded alongside the states in which they were interviewed and the numerical order of how the interviews occurred in line with the expected aggregation of the coding references from each parameter are displayed in Table 5 and pictorially displayed in Figure 4. Also, in giving an illustrative representation of this occurrence, the pie chart display of an aggregate number of themes and sub-themes coding references is captured in Figure 3 for easier display and comprehension. The coded themes were further coded to obtain a subcode. This led to reference coding at two stages, the first stage and the second stage, which could be termed aggregate-coded references. Therefore, this study has a first-level child and aggregate-coded nodes, and Table 4 is made to reflect this.

Table 4.

Main themes, parents nodes, child nodes, node categorization, and supporting coding ratio.

Table 5.

Coding references and aggregate coding references.

Figure 4.

Themes, sub-themes, and nodes categorization reference.

4.1. Theme One: Business Performance

The determination of continuation and possibly the incremental provision of services comes down to the perceived notion of a commercial show. Node business performance is grouped into business survival and wealth creation. The child node, business survival, was attributed to the alignment of business existence with the informal entrepreneurs’ presence in the market. This was also a requirement for meeting needs. This was reflected in the number of references, tallying to 209, as opposed to wealth creation having 286. Figure 5 depicts the central dispersion of the themes as they converge on business performance. This further translates to the importance that the aim of attaining good business performance is believed to be the source of measuring other tendencies, even when not placed at the forefront. Opinions that expressed how they were able to survive despite stiff competition from formal entrepreneurs are as follows:

Figure 5.

Themes, sub-themes, and nodes coding references.

“I accept the fact that life’s challenges are unavoidable, as I have come to understand that I must survive.” I view every difficulty not as an enemy, but as a teacher who has helped shape my character and sharpen my determination. Being surrounded by things that do not hurt me would give me strength and confidence. Despite the challenges I face, I view them as opportunities to grow stronger and wiser. As I face challenges head-on, I unearth hidden sources of strength and determination. In the end, these events shaped me into someone who can handle even more difficult situations.”

- Ogun Appendix 5-1

“Ensuring that the family’s basic needs are met and their financial stability is maintained, I am taking on the responsibility of supporting their aspirations and desires. My actions are guided by a strong sense of duty towards their welfare. I strive to bring stability and hope to those around me, which is why I am motivated by love and a sense of duty to make sacrifices. My daily objective is to guarantee that they have the resources to lead a life of comfort and opportunity, rather than just getting by. Instead of being seen as a burden, the trust placed in me serves as a source of strength and motivation, driving me to work tirelessly. Being involved in this position fills me with a sense of satisfaction and honour, as I am aware that my diligent efforts contribute to the improved prospects of those dear to me.”

- Ondo Appendix 6-1

The reflection of wealth creation was noted concerning the survival basis but is against the growth of the business with emphasis on performance, thereby maintaining the current stand of informality in the business. Opinion polls that reflect the question of what has been attained by working in the market were a source of income and wealth creation. This also reflects an underlying basis of business nosiness survival codification coming from wealth creation. Thus, it recounts the need to invest in the business or develop one’s self mentally in the engaged business.

“Source of income. This has allowed me to meet the financial needs of my marriage and family with ease.” I am grateful for the stable income I receive from my job, which allows me to meet my responsibilities and support my family. Here, I can discuss important matters and plan my path for the future. Now that I have a better grasp of things, I can confidently pursuing my family’s and my own goals in this field.”

- Lagos Appendix 4-8

“I now feel completely independent and capable of handling all aspects of my life on my own. I am confident in my ability to handle my academic and personal development because of this sense of independence, which has encouraged me to continue my education. By furthering my education, I am enhancing my understanding and paving the way for future achievements.”

- Ogun Appendix 5-1

“Through allocating my savings towards my business, I have achieved the realization of my aspiration and established a prosperous company from its inception.” Not only did this firm help me attain financial independence, it also helped a lot of individuals who were previously unemployed find meaningful work. The fact that I am in control of a large workforce makes me proud since I am in charge of a group that contributes to the company’s growth and longevity, ensuring the organization’s overall success.”

4.2. Theme Two: Entrepreneurial Ability

The display of entrepreneurial ability by informal entrepreneurs in the electronics market allows for the patronization of entrepreneurial services or goods. Node entrepreneurial ability involves innovation, recognition, risk-taking, and vision attributes. During coding, risk-taking attributes were further classified into explorative attributes and poverty reduction. The innovative attributes (232) had the highest reference, reflecting the ability to turn tides around and see that the possibility in any situation was a required element by the participating entrepreneurs in the informal market. Other elements include recognition (221) and risk-taking (252) attributes. The evidence for innovative attributes are as follows:

“Respect, with its origins in Yoruba culture, is a cornerstone of my business operations. In order to uphold this cultural standard, I always treat my customers with the highest degree of respect and care. Because of the mutually respectful relationships we’ve established, my clients have faith in me and continue to be loyal to me. My clients love doing business with me because they know they will always be treated with kindness and respect. We distinguish ourselves and they return because of that.”

- Lagos appendix 4-7

“I provide superior services by continuously enhancing my business skills.” I am in great demand among customers who put a high value on professionalism and expertise because I have devoted myself to the development of my creative talents. This has resulted in my being widely sought after by these customers. My proficiency has risen, which has led to an increase in the exposure of my company, which in turn has led to an increase in the number of consumers who are searching for excellent products and services.”

- Lagos appendix 4-3

4.3. Theme Three: Informal Business Survival Suggestions

Possible suggestions for formal entrepreneurship transit are obtained from informal entrepreneurs in the electronics market. From the node stats, 31 references showcase intent to transit with the requirements expected to be met. Traceable links established vision attributes (208) with informal business survival suggestions and entrepreneurial abilities. The evidence for this suggestion is as follows:

“Unlocking the potential of the next generation of skilled professionals relies on equipping young individuals with targeted training.” By investing in their development, you not only equip them with indispensable business acumen but also equip them with the confidence to enter the entrepreneurial realm. The proactive approach of registering one’s own business not only strengthens the economy but also creates new opportunities for innovation and development.”

- Ekiti recording 1-1

“Government should look into its policies and favourable policies to all sectors should be made not just considering one sector alone because it’s all interchangeable.”

- Lagos Appendix 4-1

“It is important to maintain a consistent approach to policies to promote stability and long-term progress, rather than allowing each new government to make changes solely to showcase their effectiveness. Consistent policies promote trust and predictability, allowing businesses and citizens to confidently plan for the future. When policies are consistently maintained, they foster a conducive environment for substantial progress and mitigate the upheaval that accompanies frequent changes in course.”

- Lagos Appendix 4-2

Figure 6 illustrates how all the themes converge around business performance and entrepreneurial abilities, reflecting a grounded reality. This convergence underscores the belief that strong business performance is not just an end goal but also a benchmark for identifying the key traits an entrepreneur must possess. These traits seen as usable and practical abilities form the backbone of wealth creation within informal entrepreneurship, where creativity, resilience, and adaptability play vital roles.

Figure 6.

Pie chart display of aggregate number of coding references for themes and sub-themes.

4.4. Validating the Impact of Entrepreneurial Ability on Wealth Creation

This study examined the impact of entrepreneurial ability on the wealth creation of informal entrepreneurs operating in the electronic market in six southwestern states of Nigeria. Refs. [102,103,104,105,106] posited that it was possible to be a businessperson and not an entrepreneur, but it was impossible to be an entrepreneur and not have a reference to business activities. The positions of references [107,108,109] made it known that to be recognized as an entrepreneur, certain qualities are required to turn risks into earnings.

To this end, the study requires the measurement of the entrepreneurial ability of informal entrepreneurs [manipulative and avoidance abilities] alongside wealth creation to be included in such qualities required to measure informal business performance.

The perception of the presence of the informal market is a training ground for business development among youths and survival for those avoiding wrong acts in society. This makes the eradication of such a sector an impossible task because of the possibility of keeping societal vices at bay.

Operating in the market showed that it was necessary to be equipped with informal entrepreneurial ability associated with the market. Such abilities include manipulating tactics and the use of avoidance in harnessing income from customers and evasion from governmental agencies. Ref. [47] noted the stratagem employed by informal entrepreneurs in resisting agencies while simultaneously playing along market trends to systematically work around the laws created to keep them at bay. Such tactics could involve befriending the regulators and, in the cause of the study, the street urchins.

The position of this study shows that 62.17% of the variations in wealth creation are explained by entrepreneurial ability [i.e., risk-taking and innovation], and this was noted to be in sync with Ondo Appendix 6-1 making his position known when asked “How have you been able to turn policies that are made against you into your own profitable advantage?” and he retorted with the following:

“To ensure that its policies are inclusive and beneficial to all sectors of the economy, the government should review and adjust them. It is imperative to develop policies that are not industry-specific, but rather adopt a comprehensive approach, in light of the interdependence of numerous sectors. If the government adopts a comprehensive approach, it may facilitate balanced development and mitigate the adverse impacts on industries that would otherwise remain undetected. This inclusive strategy promotes economic stability and prosperity by facilitating the growth of all sectors in tandem. If we had a more comprehensive understanding of the interactions between various industries, we could develop more equitable and effective regulations.”

- Ondo appendix 6-1

This highlights the importance of entrepreneurial projects in fostering corporate success. It underscores the necessity of internal entrepreneurial skills for overcoming challenges and facilitating progress. The enhancement and cultivation of these skills may significantly improve the sustainability and efficacy of informal businesses.

5. Research Discussion

This study enhances the current literature by confirming that the informal market, especially in the electronics sector, functions as a dynamic and frequently unstable environment. In this market, businesses must consistently adapt to survive due to high competition, changing regulations, and a dynamic consumer base. The findings are consistent with [7], who emphasized the complexity of this sector. The challenges present in this environment require the implementation of a survival paradigm, which relies significantly on entrepreneurial skills and business performance. Entrepreneurial skills are crucial for attaining the growth objectives of informal businesses, irrespective of societal and economic regulations. Participants’ responses in this study highlighted the essential role of entrepreneurial skills in securing business survival. The Business Survival Paradigm [BSP] was developed as a framework enabling informal enterprises to endure and prosper in the face of environmental challenges. The findings align with the research of [49], reinforcing the significance of entrepreneurial capabilities for the survival and success of informal businesses.

5.1. Theoretical Findings

This research advances institutional theory by demonstrating how the interaction between formal structures [rules, regulations] and informal norms [values, practices] influences the behavior and survival strategies of informal entrepreneurs in the electronics market. Institutional theory offers a framework for understanding the operational environment, characterized by formal agencies and informal enforcement mechanisms such as street urchins. In contexts where regulations are rigorously enforced, informal entrepreneurs frequently either comply or creatively adapt to circumvent interference, thereby supporting the theory’s assertion that both formal and informal institutions shape business behavior [77,110]. This research introduces the Business Survival Paradigm [BSP] as a conceptual framework based on institutional and contingency theories. Institutional theory elucidates the alignment or resistance of businesses to external pressures, while contingency theory further develops this understanding by highlighting adaptability. It examines how informal businesses modify their strategies in response to environmental conditions to ensure performance and survival.

This study, through a dual-theory framework, identifies essential entrepreneurial competencies, vision, innovation, risk-taking, strategic planning, customer relationship management, and resilience as critical to the performance of informal businesses. These abilities are associated with outcomes including financial growth, customer satisfaction, and market relevance. BSP represents a practical model for the survival and wealth creation of informal businesses, highlighting policy implications for the integration of supportive structures that connect formal and informal sectors in developing economies.

5.2. Practical Findings

This study enhances practical understanding by demonstrating how informal entrepreneurs in Nigeria’s electronics markets utilize essential entrepreneurial skills to navigate and succeed in a competitive and uncertain landscape. A consistent observation is the strategic application of entrepreneurial vision and planning. Informal entrepreneurs typically possess a well-defined vision that directs their long-term objectives and informs strategic decisions, enabling them to maintain focus in the face of market volatility. This strategic foresight reflects insights from formal business studies [111] and illustrates its application in informal contexts. Innovation and adaptability are essential for addressing market demands and technological changes. Entrepreneurs demonstrated innovation in product offerings, marketing strategies, and operational models, thereby maintaining the relevance and competitiveness of their businesses. The findings corroborate the work of [44,46], demonstrating that informal markets can sustain continuous innovation driven by necessity.