Abstract

This research presents a synthesis of social entrepreneurship (SE) in rural communities with a tourism vocation, adopting a systemic perspective applied to the case of Yecapixtla, Morelos, Mexico. Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) was used to diagnose the current state of the SE system in the Food and Beverage (F&B) sector, considering its alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The study included direct observation, field notes, and systemic modelling tools such as the structured problem situation and the rich picture, in order to interpret the relationships among the actors involved. The results show that SE plays a strategic role in the sustainability of the destination, but it faces conflicting relationships with government actors and structural limitations that hinder its consolidation. Optimal relationships were identified among community actors, as well as opportunities to improve tourism governance. The study concludes that the systemic approach enables a clearer view of the conflicts, capacities, and opportunities within the system, highlighting the need to create systemic strategies that strengthen SE as a driver of sustainable development.

1. Introduction

The challenges of the twenty-first century have made it clear that protecting and preserving natural resources such as water, soil, and air is essential for the survival and well-being of human societies. At present, it is imperative to incorporate sustainable factors and initiatives into enterprises so that they reduce their environmental impact in the production of goods and the provision of services. Addressing these environmental challenges means tackling and correcting the problems that arise during decision-making and in the development of processes. However, it is essential to implement a holistic approach that complements methods and guidelines, so that enterprises can be both profitable and sustainable [1].

Meeting the social, ecological, and ethical principles of business development remains a challenge, even for enterprises committed to socially responsible practices [2]. This situation highlights the importance of considering social entrepreneurship (SE), a social model in which social and environmental objectives are closely linked and occupy a central place in the development of business dynamics.

SE has gained relevance in recent years due to the virtues of its development, which seek socio-environmental benefit, especially in communities that combine organisational activities for both profit and non-profit purposes [3]. This form of entrepreneurship is characterised by its ability to address diverse challenges through collaborative approaches, involving different actors who are part of that environment.

This research aims to diagnose the current state of actors involved in the SE system within the Food and Beverage (F&B) sector in the rural tourism community of Yecapixtla, Morelos. The purpose is to offer a systemic perspective on how these enterprises contribute to sustainability within tourism dynamics, particularly in contexts where natural resources are vulnerable. The selection of SE initiatives in the F&B sector reflects the need for them to adapt to rapid environmental changes and the increasing demand for sustainable operations.

1.1. Literature Review

In the academic sphere, SE represents a continuously growing field of research, driven by the emergence of innovative models focused on value creation [4]. There are different concepts and approaches in the academic literature that define it. According to Ledi [5], SE refers to social enterprises, whether for-profit or non-profit, that aim to balance the creation of social value with the application of business strategies designed to address social problems while ensuring financial sustainability. With a similar approach, Zhang et al. [6] point out that SE can integrate the efficiency, innovation, and resources of traditional enterprises with the goals of non-profit organisations, enabling the identification and implementation of social, economic, and ecological values in their activities.

Peredo and McLean [7] defined SE as a model oriented towards maximising social value with the aim of generating well-being and promoting the common good within a specific community. Zulfiqar et al. [8] identified SE as a component of the solution to economic crises, providing innovative responses to unresolved social problems. Furthermore, it highlights its close relationship with the creation of social value, whose purpose is to improve societies and communities in order to enhance individual well-being.

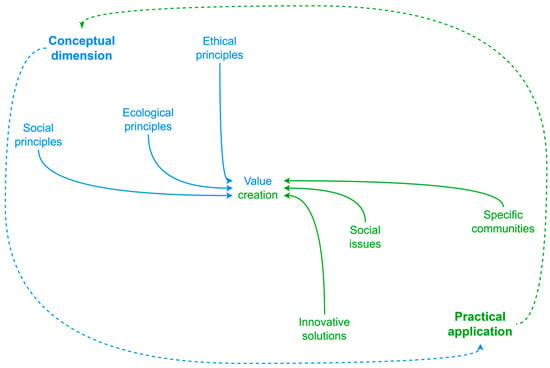

In this regard, SE has made considerable progress in its understanding and application within both academic and business fields. This type of entrepreneurship cannot be understood solely from a conceptual perspective. While social and ecological components are central to its structure, its core essence lies in translating these values into concrete, context-specific actions. Figure 1 illustrates the two-dimensional relationship of SE, integrating values and principles that guide its purpose so they can be translated into practical application.

Figure 1.

Construct of values and praxis of SE. Source: author’s own work.

In its practical dimension, values take shape through innovative and collaborative solutions that address specific social problems aimed at contributing to the well-being of concrete communities. Wang et al. [9] reinforced this idea by describing SE as a long-term solution to meet social needs through the creation, development, and implementation of opportunities oriented towards community benefit.

Under this perspective, SE is presented as a dynamic model that not only responds to immediate needs but also has a lasting impact on communities. Jørgensen et al. [10] highlighted how SE, when applied to tourism dynamics, could contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to mitigate climate change, adapt to its impacts, and promote sustainable solutions to protect the planet. This is particularly evident in developing regions, where SE fosters job creation, self-employment, and the strengthening of local development. Similarly, Dahles et al. [11] recognised SE as a key catalyst for sustainable communities due to its capacity to address environmental issues and promote local participation. In this sense, rural tourism-oriented communities possess the necessary characteristics to enhance the strengths of SE, as noted by Mottiar [12], making it an essential tool for both socioeconomic and environmental development.

Therefore, this framework not only highlights the relationship between conceptual values and their practical implementation but also supports the relevance of SE from a comprehensive approach to balancing social, environmental, and economic objectives. This integration not only aligns with the SDGs but also demonstrates how SE can be adapted to specific contexts, such as rural communities with a tourism vocation. Given the dynamic nature of SE and its growing alignment with the SDGs, it is important to explore the contexts in which these initiatives can thrive.

Rural tourism has increasingly been recognised as a fertile context for fostering sustainable development through local entrepreneurial efforts. The development of tourism in rural communities represents an opportunity to strengthen the local economy, revitalise cultural identity, and promote sustainable development. Current research has shown that the expansion of rural tourism can generate positive impacts in these areas by improving infrastructure, the environment, and mitigating the effects of economic recession [13,14]. However, to ensure a balanced interaction, effective management is required to address the challenges associated with tourism activity, as well as external support for the development of structures and infrastructures that enable long-term sustainable solutions [15].

To understand the complex relationship between the components that influence rural tourism, it is necessary to adopt a comprehensive approach that examines the specific attributes and resources of the rural community. This approach must highlight the interventions needed to achieve regional and local objectives, ensuring that tourism is not only a source of income but also a mechanism to strengthen social cohesion and community well-being [16].

Within this context, the integration and active participation of the local population is a key element in maintaining balance and thus ensuring long-term sustainability. Involving communities in the planning and execution of tourism strategies contributes to the preservation of rural authenticity and facilitates the intergenerational transmission of local culture. This, in turn, enriches visitors’ experiences by offering authenticity and cultural depth [17,18].

The importance of promoting a systemic approach that fosters the inclusion of vulnerable groups, strengthens rural entrepreneurship, and increases the competitiveness of tourism destinations has become an initiative that benefits all stakeholders involved [19]. The integration of innovative processes is fundamental to consolidating tourism as an effective tool for sustainable development, ensuring its positive impact on the community [20].

1.2. Social Entrepreneurship and Its Alignment with the SDGs

The SDGs were adopted in 2015 by the United Nations as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. These 17 goals provide a comprehensive framework for addressing social, economic, and environmental challenges on a global scale. The SDGs represent a global call to action aimed at eradicating poverty, safeguarding the environment, and improving quality of life and opportunities for people worldwide [21]. Aligning practices, public policies, and activities with the SDGs offers significant benefits by promoting balanced development that encompasses fundamental aspects such as those mentioned above. Moreover, their adoption strengthens communities, stimulates local economies, and fosters responsible innovation, contributing to a more sustainable world. To maximise their impact, it is crucial to identify specific goals that respond to the particular challenges of each place. In this regard, the integration of the SDGs can generate significant progress in rural communities with a tourism vocation, as long as those goals are selected in alignment with the key components of the system under study.

In this article, the selected SDGs are essential for addressing the problems identified in rural communities with a tourism vocation, particularly those related to the system under study. These selected goals enable the articulation of a comprehensive approach that encompasses social, economic, and environmental dimensions for the common good.

1.2.1. SDG 1: Addressing Poverty Through SE in Rural Tourism

The COVID-19 pandemic represented a significant setback in the development progress achieved so far, with an additional 90 million people falling into extreme poverty during 2020. By 2023, it was reported that only 47% of the global population had access to some form of social protection, while in low-income countries, this coverage drops to just 23% [22]. In this context, various conceptual frameworks have emerged as key tools for understanding community livelihoods in regions rich in natural resources. These frameworks, originally designed to address rural poverty in the Global South [23], offer a comprehensive approach to analysing and tackling the socio-economic challenges present in these areas. The goal of eradicating poverty in all its forms is particularly relevant for rural communities with a tourism vocation, where conditions of vulnerability are often more pronounced.

While several recent contributions have advanced the conceptualisation of SE in tourism contexts, these discussions often lack consensus regarding the boundaries of the concept. As Dees [24] pointed out, social entrepreneurship entails a combination of social missions and market-based practices, which is further nuanced in rural tourism by place-based constraints. Sharir and Lerner [25] also highlighted the importance of institutional support and actor-specific capabilities in SE success, dimensions often overlooked in descriptive frameworks.

The integration of SE presents itself as an effective strategy for promoting income generation and local employment. This combination of factors not only improves living conditions but also fosters social equity and sustainable development in such communities, thereby contributing directly to the achievement of SDG 1.

1.2.2. SDG 8: Fostering Decent Work and Local Economic Growth

The economic disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fragility of the global economy, highlighting the need for more resilient and sustainable economic models. This scenario also opened a window of opportunity to explore innovative alternatives that promote decent employment and inclusive growth, which aligns with SDG 8 [26]. In this context, SE emerges as a key tool for building more equitable and supportive recovery. Its ability to integrate ethical and sustainable values into business practices makes it an essential mechanism for strengthening local economies, especially in communities with a tourism vocation.

Economic dynamism and the generation of decent employment depend directly on the implementation of business models that prioritise sustainability and inclusion. One example of this is the Fair Trade Model, which emerged in 1988 as a social movement aimed at supporting coffee producers in Mexico. This model seeks to promote economic growth by integrating small producers from developing countries into global markets [27]. Over time, this approach has expanded and influenced other sectors, encompassing a diversity of products and ethical practices that prioritise sustainability and equity across global supply chains.

From a theoretical perspective, Schumpeter’s proposal on radical innovation is key to studying the dynamics of developing economies. This approach emphasises market plasticity and uncertainty as catalysts for innovation, highlighting how entrepreneurship acts as a transformative agent. According to Schumpeter, entrepreneurs revolutionise economic structures from within and drive continuous processes of creativity that generate new economic opportunities and foster the emergence of disruptive business models [28].

1.2.3. SDG 12: Promoting Responsible Production Through Circular Models

According to a report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), plastic accounts for 85% of the waste that reaches the oceans. It is projected that by 2040, plastic emissions into aquatic ecosystems could nearly triple, reaching between 23 and 37 million tonnes annually [29]. However, the impact of this crisis is not evenly distributed. Rural communities, whose livelihoods often depend on vulnerable natural resources, face specific challenges. This situation highlights the urgency for countries to prioritise sustainable practices, including waste reduction and the minimisation of food loss.

Promoting SE can play a key role by encouraging economic models that optimise the use of natural resources, reduce environmental impact, and contribute to the fulfilment of SDG 12 through the incorporation of circular economy principles focused on sustainability [30].

Thus, entrepreneurship for community well-being focuses on establishing multidimensional well-being as its central objective, promoting various types of entrepreneurship: commercial, social, and institutional. This approach, based on a bottom-up strategy, holds greater potential to generate long-term sustainable value compared to traditional models. Examples of its application can be observed in mining regions of Antioquia, Colombia, where it has contributed to transforming underdeveloped local economies. Furthermore, by integrating responsible consumption and production practices, its contribution to SDG 12 is reinforced, highlighting the importance of balancing economic development with environmental sustainability [31].

1.2.4. SDG 13: Climate Resilience Through Sustainable Tourism

The increase in global temperature by 1.1 °C above pre-industrial levels represents a global warning that demands a restructuring of human development as we know it. According to the United Nations [22], this rise has intensified both the frequency and magnitude of climate-related disasters, affecting an average of 151 million people annually between 2015 and 2021. If this trend continues, it is estimated that global temperature could exceed 1.5 °C by 2035.

Climate action has become an urgent necessity, and its success depends on the collaboration of all stakeholders. The alignment of climate policies with the values of younger generations may foster an identity rooted in sustainable behaviours and reduce the social pressure that can hinder the adoption of pro-climate actions [32].

In this context, sustainability indicators—such as those related to economy and society—play a key role in evaluating and monitoring the impact of human activities on the environment, providing essential tools to achieve long-term sustainability goals [33]. One of the sectors where these indicators are particularly relevant is tourism, due to its considerable environmental impact. Through the adoption of sustainable practices, tourism has the potential to contribute to climate change mitigation. In rural communities, where tourism and economic activities place significant pressure on ecosystems, the implementation of strategies based on these indicators is essential to minimise negative effects and strengthen resilience, thereby ensuring long-term sustainability [34].

1.2.5. SDG 17: Strategic Partnerships to Advance Rural Sustainability

Financial reforms are an urgent necessity, particularly considering that 23% of national statistics institutes in low-income countries face severe programme deficits. To address this issue, a stimulus plan for the SDGs has been proposed, with annual funding of USD 500 billion until 2030 [22]. Despite the existence of voluntary regulatory frameworks, internal accountability regarding SDG compliance remains a challenge. According to Franco and Abe [35], these efforts must be complemented with external monitoring mechanisms, such as sustainability reports, which are often aligned with the principles of international networks and allow for a more objective assessment of progress in sustainable development. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that many companies adopting a sustainability approach base their actions on scattered initiatives—frequently in the form of corporate philanthropy—reflecting the absence of a cohesive strategy that effectively integrates the SDGs into their operations.

The success of effective SDG implementation, particularly in rural communities with a tourism vocation, depends on the articulation of strategic partnerships between governments, businesses, academia, and civil society. Such collaborations enable the creation of synergies that maximise the impact of sustainable initiatives and ensure their long-term viability.

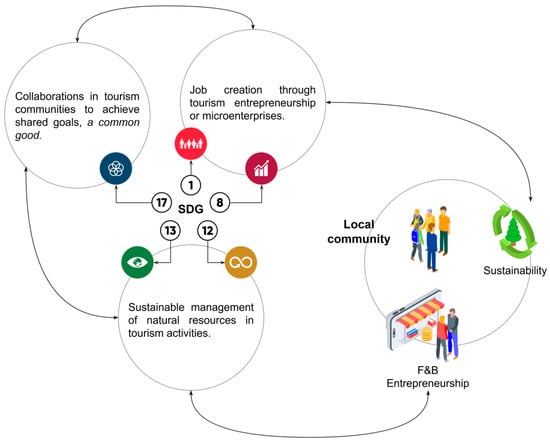

Figure 2 illustrates how these goals interact within the context of rural communities with a tourism vocation. It represents a systemic approach in which social, economic, and environmental elements are interconnected, demonstrating that the achievement of the selected SDGs does not occur in isolation, but rather through the integration of collaborative strategies that maximise their impact on sustainable development.

Figure 2.

SDGs in the dynamics of rural communities with tourism vocation. The numbers correspond to SDGs referenced in the figure: 1 (No poverty), 8 (Decent work and economic growth), 12 (Responsible consumption and production), 13 (Climate action), and 17 (Partnerships for the goals). Source: author’s own work.2. Methods.

This combination of elements emphasises the importance of selecting goals that respond to local needs and strengthen the capacity of communities to address global challenges from a local and sustainable perspective.

These elements provide a comprehensive conceptual framework that supports the application of a systemic methodology, which will be further detailed in the following section.

1.3. Case Study Description

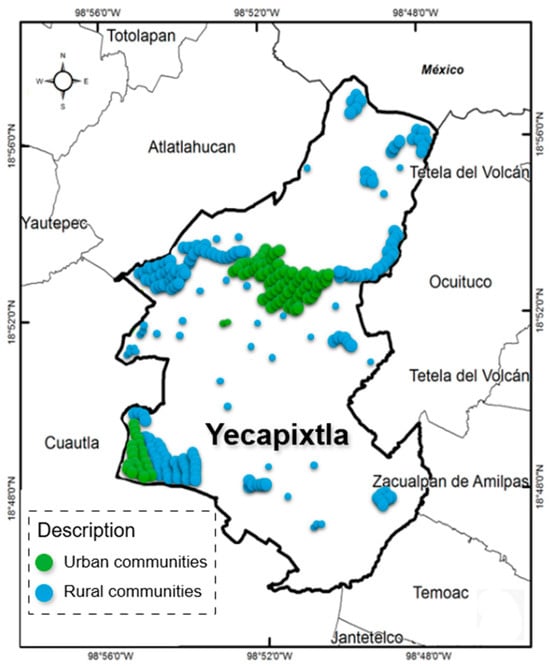

Yecapixtla is a municipality located in the northeast of the state of Morelos, Mexico, with a territorial area of 173.2 km2 and an altitude ranging between 1300 and 2200 metres above sea level (Figure 3). Its population amounts to 56,083 inhabitants, with a growth of 19.8% over the last decade [36], and a projection indicating a sustained upward trend towards 2030 [37]. The local economy is mainly based on commerce (47.25%), services (34.91%), and manufacturing (17.19%) [38], with a total of 2309 registered economic units. The economically active population represents 67% of inhabitants over the age of 12 [39].

Figure 3.

Geographical map of Yecapixtla. Source: INEGI [40].

Yecapixtla’s productive sector is mainly composed of small and medium-sized enterprises, with commerce and services as its primary economic activities. As of 2024, 2309 economic units were registered, most of which belong to the micro, small, and medium-sized enterprise category [41]. Within the services sector, 806 economic units were identified, which provide employment to approximately 1935 people.

The services sector in Yecapixtla includes activities such as tourism-related services, F&B establishments, and retail businesses, while manufacturing involves food processing, artisanal production, and small-scale construction materials. These sectors contribute significantly to local employment and entrepreneurship. Such activities play a fundamental role in the local economy by promoting self-employment and encouraging the development of businesses aimed at both serving the local population and supporting tourism [42].

Beyond its economic relevance, Yecapixtla stands out as a cultural and gastronomic destination in the state of Morelos. It is widely known for its traditional dish cecina (salted and dried beef), which attracts thousands of visitors annually, particularly during the local fair. Additionally, its historic 16th-century convent and well-preserved colonial architecture contribute to its appeal as a rural tourism destination. These distinctive characteristics make Yecapixtla a suitable context for examining the role of social entrepreneurship in the Food and Beverage sector, within a community that blends cultural heritage with tourism-driven dynamics.

From a development perspective, Yecapixtla faces challenges in managing its economic growth and attracting foreign investment. Nevertheless, its strategic location and productive diversification represent a key opportunity to strengthen local tourism, contributing to its consolidation as a sustainable and resilient destination.

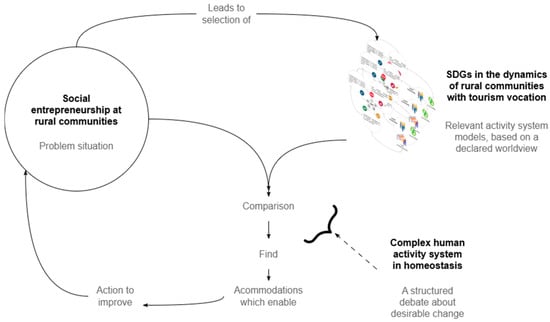

Given the growing emphasis on sustainable development and the need to strengthen local economies, it is essential to adopt comprehensive approaches to study social enterprises in rural communities with a tourism vocation. This research adopted a systemic approach through the use of SSM [43], a flexible tool used to address problems with high social content from a phenomenological and hermeneutic perspective. In this context, SSM enables the development of a comprehensive diagnosis that facilitates the identification of solutions to the challenges associated with SE in the F&B sector in the rural community of Yecapixtla, Morelos.

This methodological process begins with the identification of the actors and entities that make up the system under study, considering the environmental, economic, and social context in which they operate. Based on this identification, the relationships among the system’s elements are studied and interpreted with the aim of developing a comprehensive diagnosis of the current situation.

Subsequently, a structural diagram of the system is constructed, in which each component is represented through specific icons, facilitating the visualisation of their interactions. This graphical representation is complemented by systemic mapping, known as a rich picture, which enables the identification of key relationships and critical factors that influence the issue. This is accompanied by the selection and comparison of relevant activity system models to identify those that best fit the system under study.

In addition, this research considered the SDGs within the dynamics of rural communities with a tourism vocation, allowing for the structuring of a critical discourse on the desirable and feasible changes within the system. Figure 4 illustrates the application of SSM in this context, detailing the study procedure for the implementation of solutions.

Figure 4.

Soft System Methodology in action. Source: modified from Checkland [44]. Note: The background element is a referential depiction of Figure 2, used here to contextualise the systemic process. It does not contain new data.

In this representation, SE in rural communities is examined through the lens of human activity systems, facilitating a process of reflection, comparison, and adjustment that supports the implementation of improvement actions. These actions are aimed at strengthening SE within the F&B sector by promoting innovative practices and enhancing the competitiveness of rural tourism destinations.

Fieldwork was conducted in four stages between July and October 2024. These included exploratory visits, engagement with local food businesses, and observation of social and economic dynamics in the community. A total of four on-site visits were carried out, combining informal conversations, stakeholder mapping, and non-participant observation. Field notes were systematically recorded in a diary and supplemented by structured observation guides and categorisation formats. This process enabled the identification of patterns, constraints, and tensions within the system, using criteria including the frequency of interactions, the roles of actors, and their alignment with sustainability practices.

To strengthen the diagnosis, direct observation in Yecapixtla focused on SE initiatives within the F&B sector. This stage offered insights into the functioning of the system and its interaction with the local tourism environment considering actor relationships, fluctuations in demand (weekdays, weekends, and festivals), and spatial or logistical barriers. These empirical tools made it possible to interpret how social, economic, and environmental dynamics are interwoven in the everyday practices of SE initiatives, some of which are already aligned with the SDGs, while others show potential to evolve in that direction.

2. Results

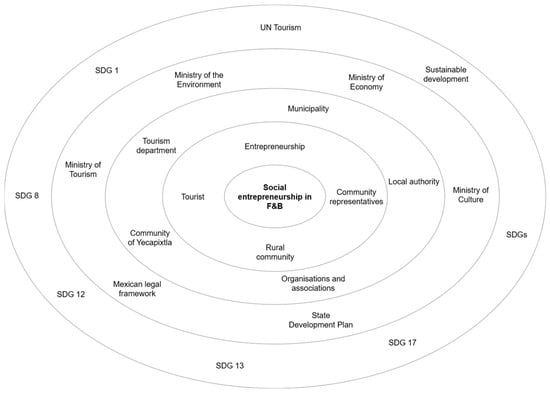

The following results address the main research objective by identifying the dynamics, relationships, and institutional factors that influence the functioning of the SE system in the F&B sector of Yecapixtla. Through the application of SSM, a structured interpretation of the current problem situation was developed by identifying and mapping key stakeholders and their relationships. Figure 5 outlines this systemic situation, positioning the various actors according to their degree of influence and level of participation within the SE system in the F&B sector. Although the figure primarily focuses on stakeholder interactions, it reflects the essence of a problem situation as defined by SSM: one that is not isolated or linear, but rather emerges from the dynamics of relationships, tensions, and misalignments between the actors involved.

Figure 5.

Structured stakeholder relationships in the SE system. Source: author’s own work.

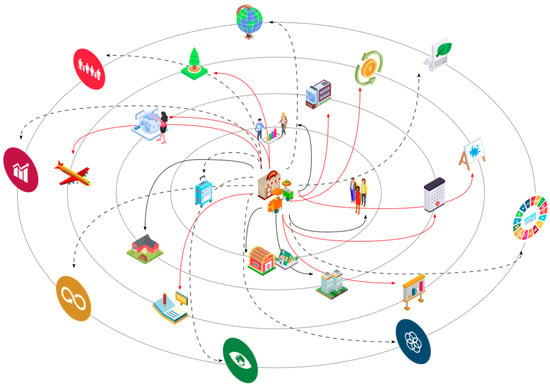

Structuring the problem enabled the construction of the rich picture (Figure 6), which includes both previously identified formal elements and additional actors who directly influence the SE dynamics. It also allowed for the interpretation of the interrelationships among the actors within the system under study, as well as the tensions and opportunities that form part of the current context.

Figure 6.

System rich picture. Source: author’s own work. Note: Solid black lines indicate optimal relationships, dotted lines indicate fragmented ones, and red lines reflect conflicting relationships.

Figure 6 illustrates a synthesis of the relationships among the actors that make up the SE system in the tourist community of Yecapixtla. The rich picture of the system under study is characterised by the integration of three types of relationships, according to their degree of influence and impact. The relationships among actors were classified as optimal, fragmented, or conflicting based on a systemic interpretation supported by the application of SSM and direct observation during fieldwork.

This interpretation considered how frequently stakeholders interacted, how collaborative their practices were, and how well institutional and community goals aligned. These relationship types are visually represented in the rich picture: solid black lines indicate optimal relationships, characterised by active collaboration, constant communication, and shared goals. These are concentrated within the system in focus, reflecting the community’s efforts to shift towards a more sustainable tourism dynamic. Dotted lines represent fragmented relationships, where interaction is sporadic or coordination mechanisms are weak or absent. This is evident in the limited adoption of public policies aligned with the SDGs (1, 8, 12, 13, and 17), and the insufficient recognition of SE initiatives by governmental institutions. Red lines, in turn, represent conflicting relationships, often shaped by tensions, disagreements, or institutional practices that interfere with the system’s functioning. These are predominantly associated with government actors and agencies responsible for managing, coordinating, and planning tourism dynamics.

Furthermore, to provide a more detailed interpretation of the relationships between the system’s components, Table 1 presents the classification of actors based on their position within the system.

Table 1.

Levels of interpretation of the system under study.

The application of SSM revealed the complexity of the tourism dynamic within the system under study by illustrating how actors interact and influence one another. This systemic perspective enabled the identification of patterns, tensions, and opportunities for strengthening local sustainability. While no formal case studies were included, the findings are grounded in direct field observation and the modelling of actor relationships. This methodological approach offers contextual insights into the social, institutional, and territorial dynamics of the case study, supporting progress toward more collaborative and resilient tourism governance in communities such as Yecapixtla.

3. Discussion

The application of SSM allowed a comparison between theoretical assumptions and the observed reality, reinforcing the usefulness of a systemic approach to diagnosing and interpreting SE dynamics in rural tourism communities. The methodological tools used in the process included the rich picture, the classification of actors, and direct observation. Together, these tools facilitated the identification of key relationships that support the system, as well as the factors that limit its homeostasis.

The complexity of activity across the macro-environment, environment, and system in focus demonstrates that, despite the adoption of sustainable practices by entrepreneurs in Yecapixtla, structural conditions continue to constrain their effectiveness and continuity. While SE is defined as a model that integrates and balances social, environmental, and economic goals, its performance in rural contexts is not linear. It became evident that SE initiatives in the F&B sector face considerable challenges in establishing optimal relationships with other actors. The presence of conflicting relationships with government bodies and international organisations indicates a disconnection between regulatory frameworks, public policies, and the actual needs of entrepreneurs in Yecapixtla. This lack of homeostasis within the system also compromises the achievement of the selected SDGs.

Thus, SE in Yecapixtla cannot be understood merely as a business strategy, as its creation and organisation emerge in a context of tension between local and institutional actors. This highlights the need to consolidate a platform that brings together all relevant stakeholders and acknowledges the cultural, economic, and environmental specificities of the community.

Rural tourism could help improve living conditions in Yecapixtla by implementing tangible strategies adapted to the nature of the place. Therefore, adopting a systemic approach presents an opportunity to enhance tourism governance in Yecapixtla, along with the need to create structural conditions that enable SE initiatives to operate effectively and with greater influence. The creation of sustainability indicators tailored to Yecapixtla would provide a benefit at the “environment” level within the system under study, by offering measurements that reflect the reality of the elements contributing to sustainable development, thereby directly supporting the achievement of the identified SDGs. Such reflections are essential for moving towards more equitable and sustainable development models in rural contexts, where SE can act as a true agent of change.

These findings resonate with previous studies, such as those by Dahles et al. [11] in Cambodia and Wang et al. [9] in rural China, which have highlighted the structural and institutional limitations often faced by social entrepreneurship in tourism contexts. Similarly to the disconnection observed in Yecapixtla, other studies have found that even when public policies formally support sustainability, there is often a lack of coordination and continuity at the local level. The systemic approach adopted in this study particularly through the use of SSM allowed for the identification of such limitations not merely as isolated challenges, but as emergent properties of the system itself. This methodological perspective offers a valuable lens for understanding the underlying relationships and tensions that shape the effectiveness of SE initiatives in rural tourism communities.

Based on the systemic diagnosis conducted, certain strategic orientations can be proposed as future pathways for addressing the challenges identified. These may include the promotion of local governance platforms that enhance collaboration between SE actors and institutions, the formulation of context-specific sustainability indicators, and the encouragement of participatory planning processes that reflect the cultural and economic characteristics of the territory.

In this regard, local public authorities such as the Municipal Tourism Office and the Economic Development Council could play a central role in coordinating SE efforts and aligning them with sustainability agendas. Implementation mechanisms might include participatory forums, periodic monitoring of progress toward SDGs, and local training programmes that promote entrepreneurial competencies. While these strategies were not directly implemented in the present study, they emerge as relevant considerations for future research and policy design aimed at consolidating SE as a driver of sustainable development in tourism-oriented rural communities. Knowledge transfer mechanisms, such as collaborative training initiatives, joint planning sessions, and feedback loops between community organisations and institutional actors, can also be instrumental in closing the gap between strategic public agendas and local implementation.

4. Conclusions

This study enabled the identification of the current state of SE in Yecapixtla, Morelos, as well as the key actors involved in its dynamics. The findings revealed that optimal relationships are primarily concentrated among community actors, whereas conflicting relationships are mainly associated with government institutions and external entities. SE initiatives in the F&B sector were shown to play a strategic role in sustaining the tourism destination; however, they face significant challenges to becoming consolidated, especially due to the lack of supportive public policies and limited institutional continuity.

The application of SSM allowed the diagnosis of conflicts, discontinuities, and opportunities within the system. Based on the analysis, the promotion of local governance platforms that enhance stakeholder collaboration and support the achievement of the SDGs through a territorial approach is recommended. This research confirms the relevance of SE as a potential driver of sustainable development in rural tourism-oriented communities, provided that the necessary structural and governance conditions are established to ensure its continuity.

Future studies could benefit from applying semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders and integrating sustainability indicators tailored to the local context, in order to improve the capacity to monitor progress towards the SDGs. These aspects represent promising lines of inquiry for future research focused on strengthening the role of SE as a catalyst for sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T.-P.; methodology and validation, I.B.-P. and R.T.-P.; formal analysis, Z.P.-M.; investigation and resources, M.L.R.-E., Z.P.-M. and L.M.H.-S.; data acquisition, L.M.H.-S. and I.B.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.P.-M., M.L.R.-E. and R.T.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article is supported by Instituto Politécnico Nacional, México, through the project SIP 3420, granted by Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado and Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI), México.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the nature of the research, which did not involve experiments on humans or animals, but consisted of observational and participatory methods in public settings with no risk to participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants in a way that required informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the collaboration of the local community in Yecapixtla, particularly the social entrepreneurs who shared their time and knowledge during the fieldwork. We also thank the support of the postgraduate programme in Systems Engineering at Instituto Politécnico Nacional for facilitating academic infrastructure and guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Serzante, M.; Khudozhnyk, A. Reviewing Sustainability Measurement Methods for Enterprises. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latter, S.; Bruce, F.; Baxter, S. A Conscious Convergence: Leading Innovation Through Design Thinking. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Online, 16–17 September 2021; Academic Conferences International Limited: Manchester, UK, 2021. ISBN 9781914587108. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, G.; Monticelli, J.M.; Bortolaso, I.V.; Hidalgo, G.; Monticelli, J.M.; Bortolaso, I.V. Social Capital as a Driver of Social Entrepreneurship. J. Soc. Entrep. 2024, 15, 182–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Chauhan, S.; Paul, J.; Jaiswal, M.P. Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledi, K.K. SDG Motivation and Social Entrepreneurial Intentions. The Moderating Roles of Institutional and Social Support. J. Soc. Entrep. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Gao, Y.; Dong, Y. Paths out of Poverty: Social Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1062669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peredo, A.M.; McLean, M. Social Entrepreneurship: A Critical Review of the Concept. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, S.; Athar, M.; Khan, M.K.; Azfar, M.; Muhammad, A.; Iqbal, B.; Asmi, F.; Science, M. Opportunity Recognition Behavior and Readiness of Youth for Social Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Res. J. 2019, 11, 20180201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Huang, K. How Does Social Entrepreneurship Achieve Sustainable Development Goals in Rural Tourism Destinations? The Role of Legitimacy and Social Capital. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 0, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, M.T.; Hansen, A.V.; Sørensen, F.; Fuglsang, L.; Sundbo, J.; Jensen, J.F. Collective Tourism Social Entrepreneurship: A Means for Community Mobilization and Social Transformation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 88, 103171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahles, H.; Khieng, S.; Verver, M.; Manders, I. Social Entrepreneurship and Tourism in Cambodia: Advancing Community Engagement. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 816–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottiar, Z. Exploring the Motivations of Tourism Social Entrepreneurs. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1137–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Knight, D.W.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zi, M. Rural Tourism and Evolving Identities of Chinese Communities in Forested Areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kang, Y.; Park, J.; Kang, S.E. The Impact of Residents’ Participation on Their Support for Tourism Development at a Community Level Destination. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, L.N.A.; Simatele, M.D. Food Security and Coping Strategies of Rural Household Livelihoods to Climate Change in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 692185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.-P.; Gurau, C.; Lasch, F. Entrepreneurship, Tourism and Regional Development: A Tale of Two Villages. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2014, 26, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Zhu, D.; Cheng, S.; Li, Q. “It Is My Place”: Residents’ Community-Based Psychological Ownership and Its Impact on Rural Tourism Participation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 0, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, E.M.B.P.; Xie, Y.; Ahmad, S. Rural Residents’ Participation Intention in Community Forestry-Challenge and Prospect of Community Forestry in Sri Lanka. Forests 2021, 12, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.Z.; Patiño, A.R.; Tejeida, P.R. Capítulo 4: Una Perspectiva Sistémica Del Emprendimiento En El Fortalecimiento de Los Vínculos Urbano-Rurales En El Turismo. In Ciudades y Comunidades Sustentables: Buenas Prácticas en Turismo; Fondo Editorial de la Universidad Nacional Experimental Sur del Lago, Jesús María Semprum (UNESUR): Santa Bárbara de Zulia, Venezuela, 2024; pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Erazo, C.P.; del Río-Rama, M.d.l.C.; Miranda-Salazar, S.P.; Tierra-Tierra, N.P. Strengthening of Community Tourism Enterprises as a Means of Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: A Case Study of Community Tourism Development in Chimborazo. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations SDGs. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/es/goals (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- United Nations Informe de Los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Spec. Ed. 2023, 83, 1–80. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2023_Spanish.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Franco, I.B.; Minnery, J. SDG 1 No Poverty Building Sustainable Communities: A Framework for Supporting Community Livelihoods and Poverty Alleviation in Resource Regions. In Actioning the Global Goals for Local Impact: Towards Sustainability Science, Policy, Education and Practice; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dees, J.G. The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship. In Kauffman Found; Stanford Univercity: Stanford, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sharir, M.; Lerner, M. Gauging the Success of Social Ventures Initiated by Individual Social Entrepreneurs. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal8#progress_and_info (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Ribeiro-Duthie, A.C. SDG 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth. In Actioning the Global Goals for Local Impact: Towards Sustainability Science, Policy, Education and Practice; Franco, I.B., Chatterji, T., Derbyshire, E., Tracey, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 117–133. ISBN 978-981-32-9927-6. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 0203202058. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. From Pollution to Solution: A Global Assessment of Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; ISBN 978-92-807-3881-0. [Google Scholar]

- Smitskikh, K.V.; Titova, N.Y.; Shumik, E.G. The Model of Social Entrepreneurship Dynamic Development in Circular Economy. Univ. Y Soc. 2020, 12, 248–253. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, I.B.; Newey, L. SDG 12 Responsible Consumption and Production. Sustainable Community Development through Entrepreneurship: Corporate-Based versus Wellbeing-Centred Approaches to Responsible Production. In Actioning the Global Goals for Local Impact: Towards Sustainability Science, Policy, Education and Practice; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, I.B.; Tapia, R.; Tracey, J. SDG 13 Climate Action. In Actioning the Global Goals for Local Impact: Towards Sustainability Science, Policy, Education and Practice; Franco, I.B., Chatterji, T., Derbyshire, E., Tracey, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 219–228. ISBN 978-981-32-9927-6. [Google Scholar]

- Magazzino, C.; Zoundi, Z. Enhancing Climate Action Evaluation Using Artificial Neural Networks: An Analysis of SDG 13. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, A.; Ahmed, I.; Johnson, T.; Tang, L.; Alston, M. Localizing Sustainable Development Goal 13 on Climate Action to Build Local Resilience to Floods in the Hunter Valley: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, I.B.; Abe, M. SDG 17 Partnerships for the Goals. In Actioning the Global Goals for Local Impact: Towards Sustainability Science, Policy, Education and Practice; Franco, I.B., Chatterji, T., Derbyshire, E., Tracey, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 275–293. ISBN 978-981-32-9927-6. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI Yecapixtla, Morelos. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/?ag=070000170030#collapse-Resumen (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- CONAPO Mapa Interactivo de Indicadores de Población En México Con Base En La Conciliación Demográfica de México 1950-2019 y Proyecciones de La Población de México y Las Entidades Federativas 2020–2070. Available online: https://conapo.segob.gob.mx/work/models/CONAPO/pry23/PP/index.html (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Data Mexico Yecapixtla, Municipality of Morelos. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/en/profile/geo/yecapixtla (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- INEGI Demografía y Sociedad de Yecapixtla, Morelos. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/?ag=070000170030#collapse-Indicadores (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- INEGI Mapa de Yecapixtla, Morelos. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/?ag=070000170030#collapse-Mapas (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Data Mexico Workforce and Salaries by Occupation. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/en/profile/geo/yecapixtla#economy (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- INEGI Directorio Estadístico Nacional de Unidades Económicas. Yecapixtla, Morelos. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/mapa/denue/?ag=17030 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Checkland, P. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice: Includes a 30-Year Retrospective. In Systems Thinking, Systems Practice: Includes a 30-Year Retrospective; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Checkland, P. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).