Automated and Concurrent Synthesis of Fractional-Order QFT Controllers for Ship Roll Stabilization Using Constrained Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

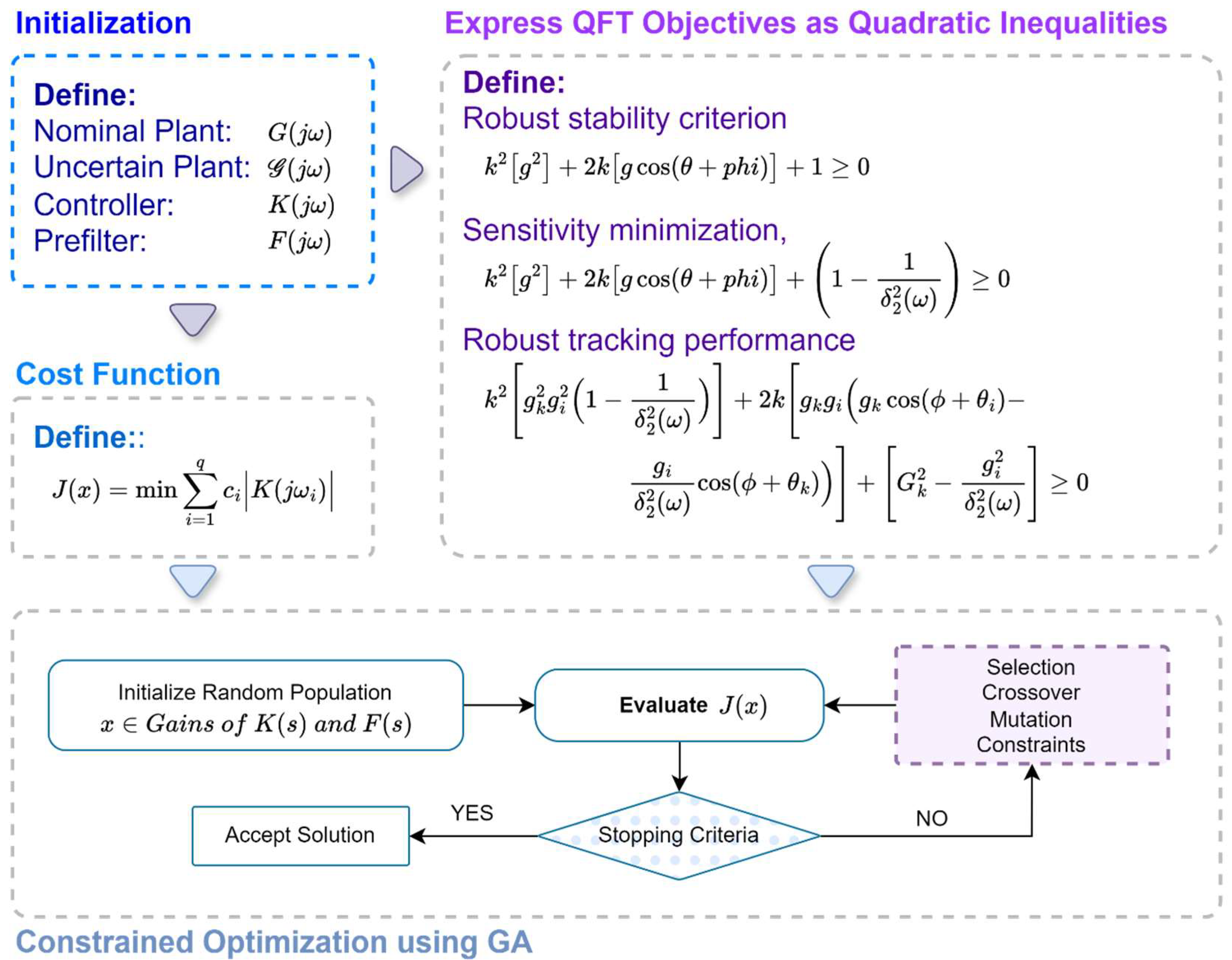

- A bounds- and template-free constrained optimization-based procedure is proposed for the simultaneous synthesis of a fractional order QFT controller and pre-filter, wherein the design bounds are expressed as quadratic inequalities, which should be complied with at each design frequency, while minimizing the feedback cost constrained by QFT bounds.

- (b)

- The proposed method also gives freedom to the control designer to pre-specify the controller and pre-filter structure at the beginning of the process, which otherwise is not possible in the conventional QFT design.

- (c)

- The proposed technique examines the synthesis of a fractional QFT controller and pre-filter for fin stabilization of the ship rolling [27]. The ship roll stabilization is one of the critical problems in marine engineering, as it directly impacts the vessel safety, operational efficiency, and passenger comfort, wherein excessive roll can lead to cargo shift, reduced propulsion efficiency, and increased risk of capsizing in extreme conditions. The attained results exhibit better performance specifications when compared to classical PID, QFT, , IMC, and MPC controllers.

- (d)

- A comprehensive robustness analysis using sensitivity analysis and Monte Carlo simulations is also included to validate the robustness of the controllers by subjecting the plant to normally distributed random perturbations.

2. Background

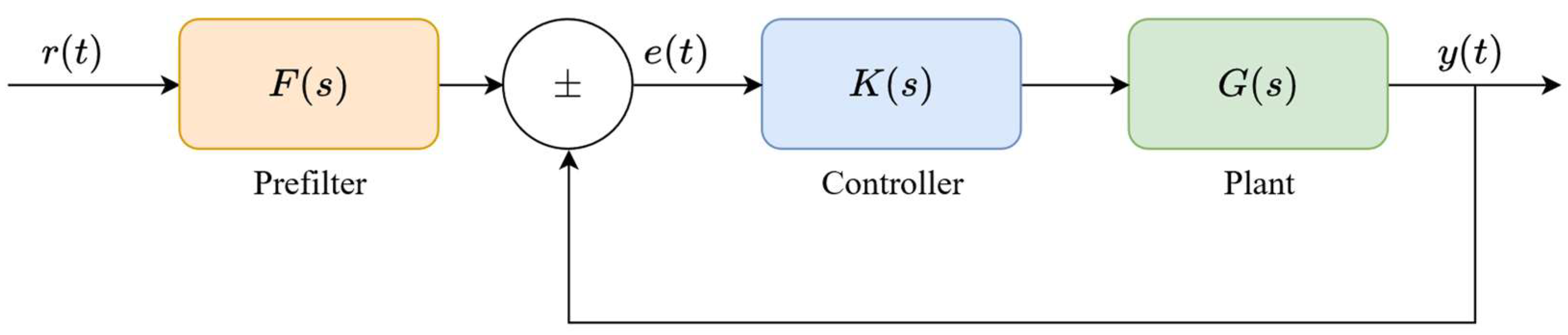

2.1. Quantitative Feedback Theory

2.2. Fractional Order PID Controller

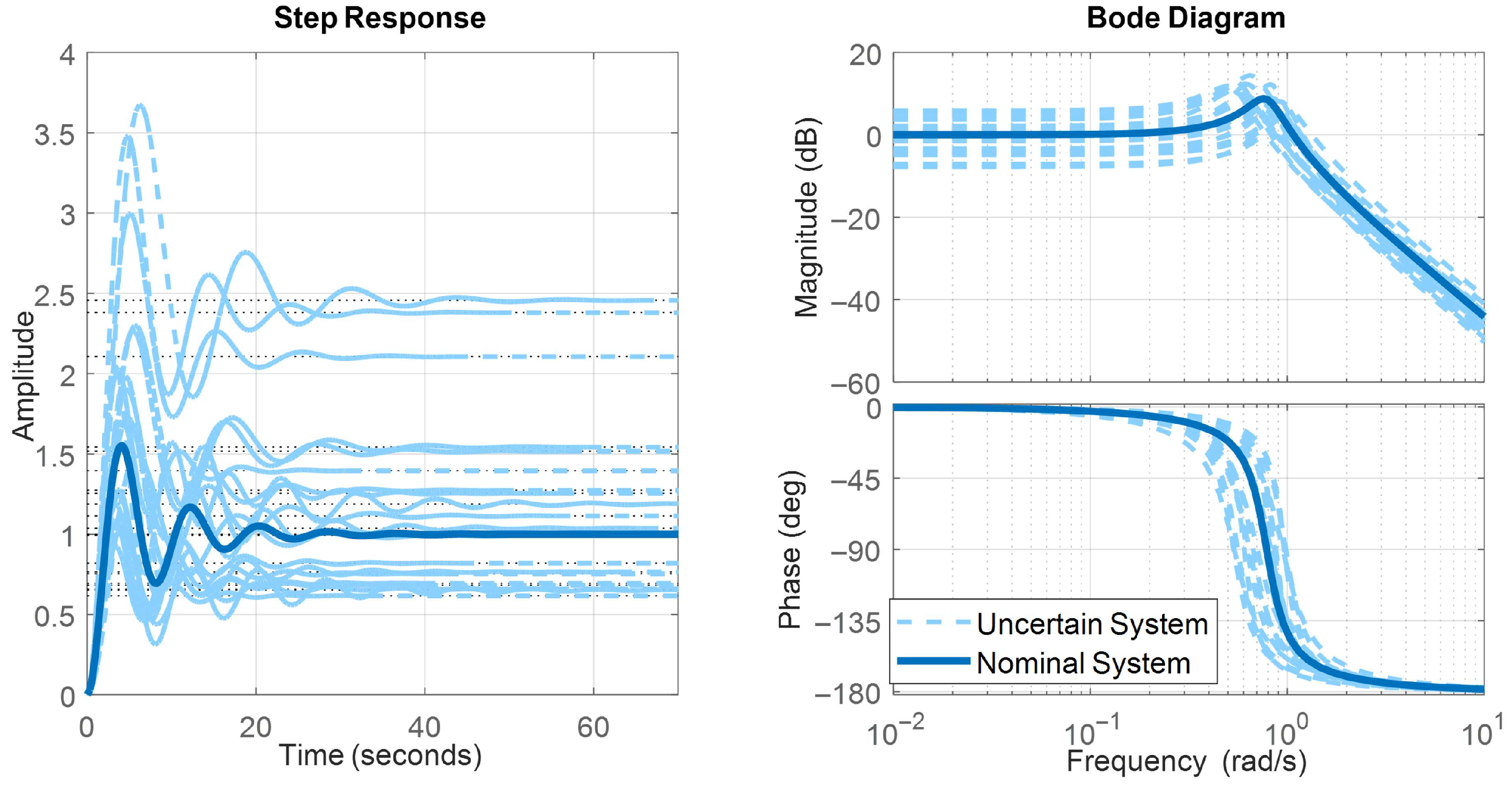

2.3. Mathematical Model of the Ship Roll

3. Constrained Optimization-Based Simultaneous QFT Controllers Synthesis

3.1. Robust Stability

3.2. Plant Output Disturbance Rejection

3.3. Tracking Performance

4. Results

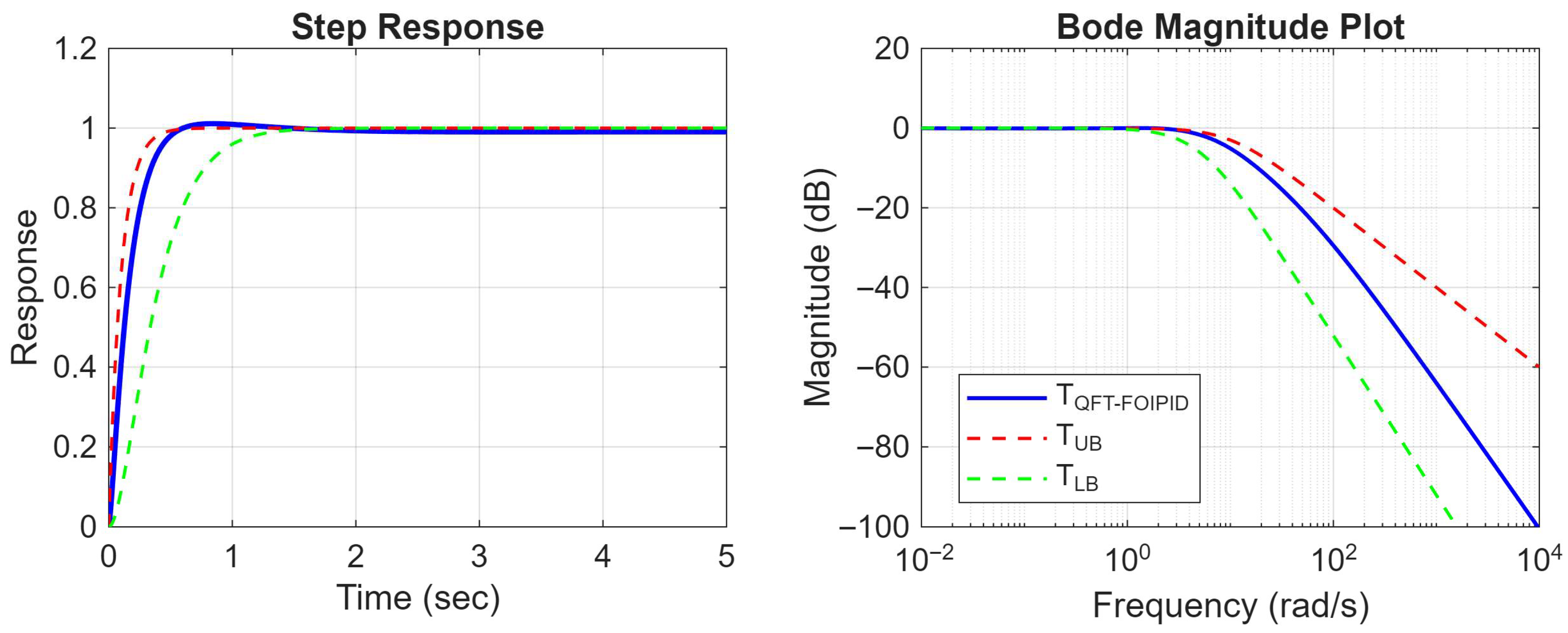

4.1. Closed Loop Response with Nominal Plant Parameters

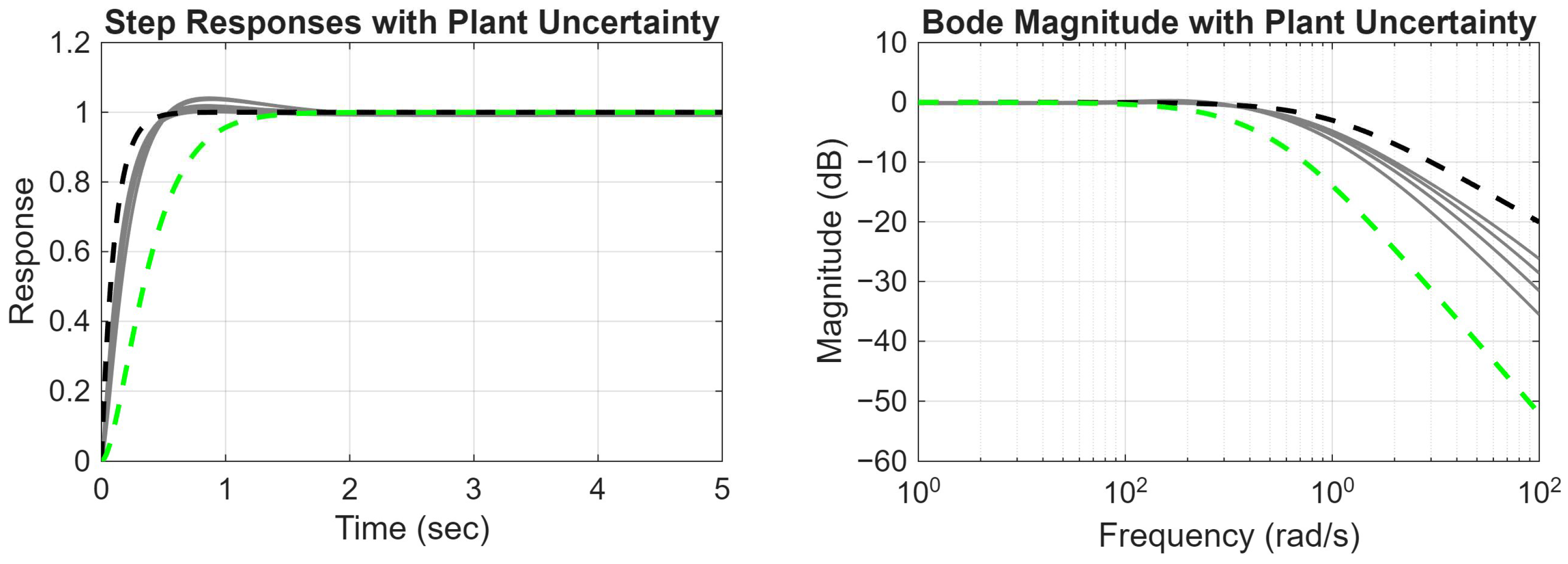

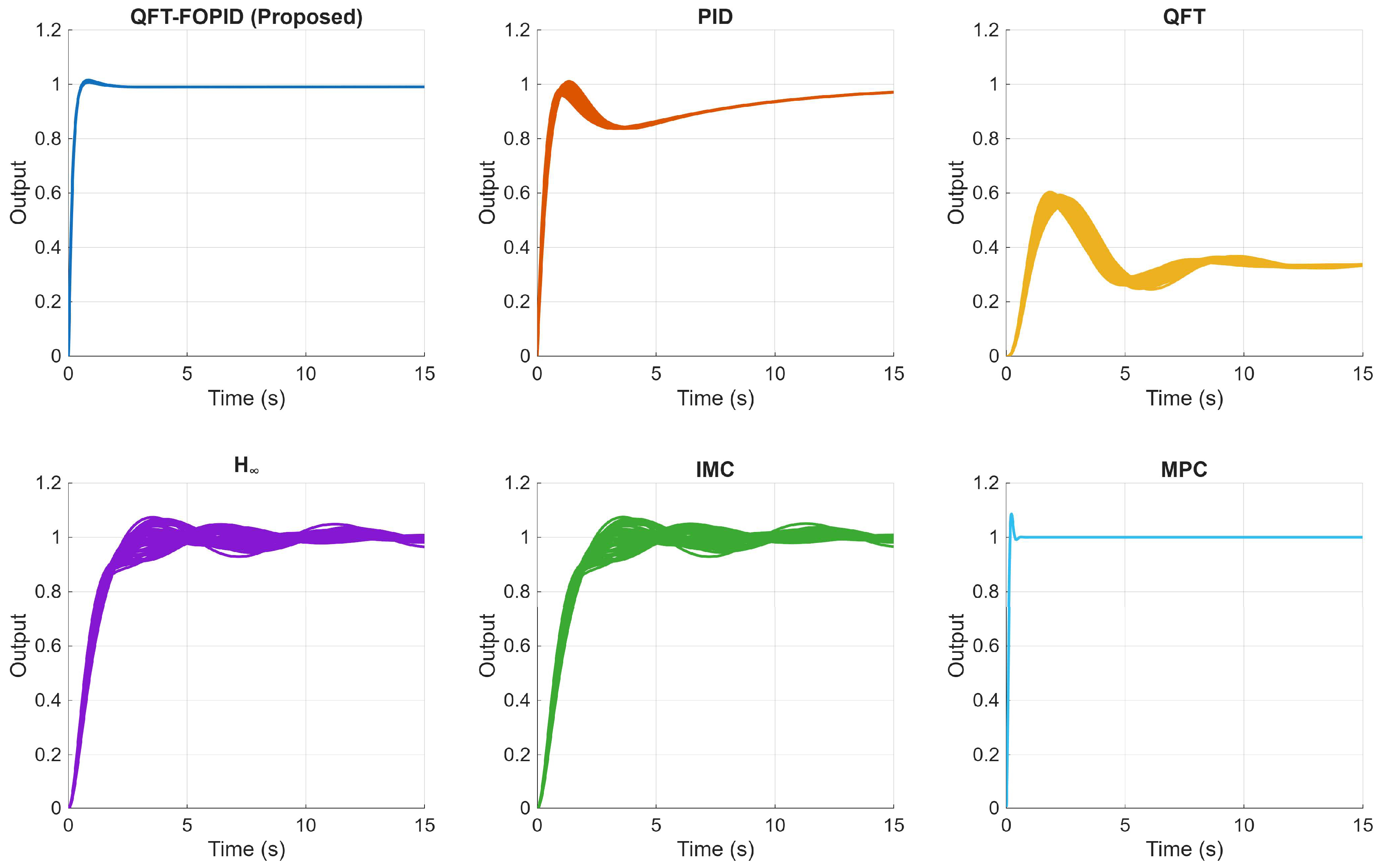

4.2. Closed Loop Response with Uncertain Plant Parameters

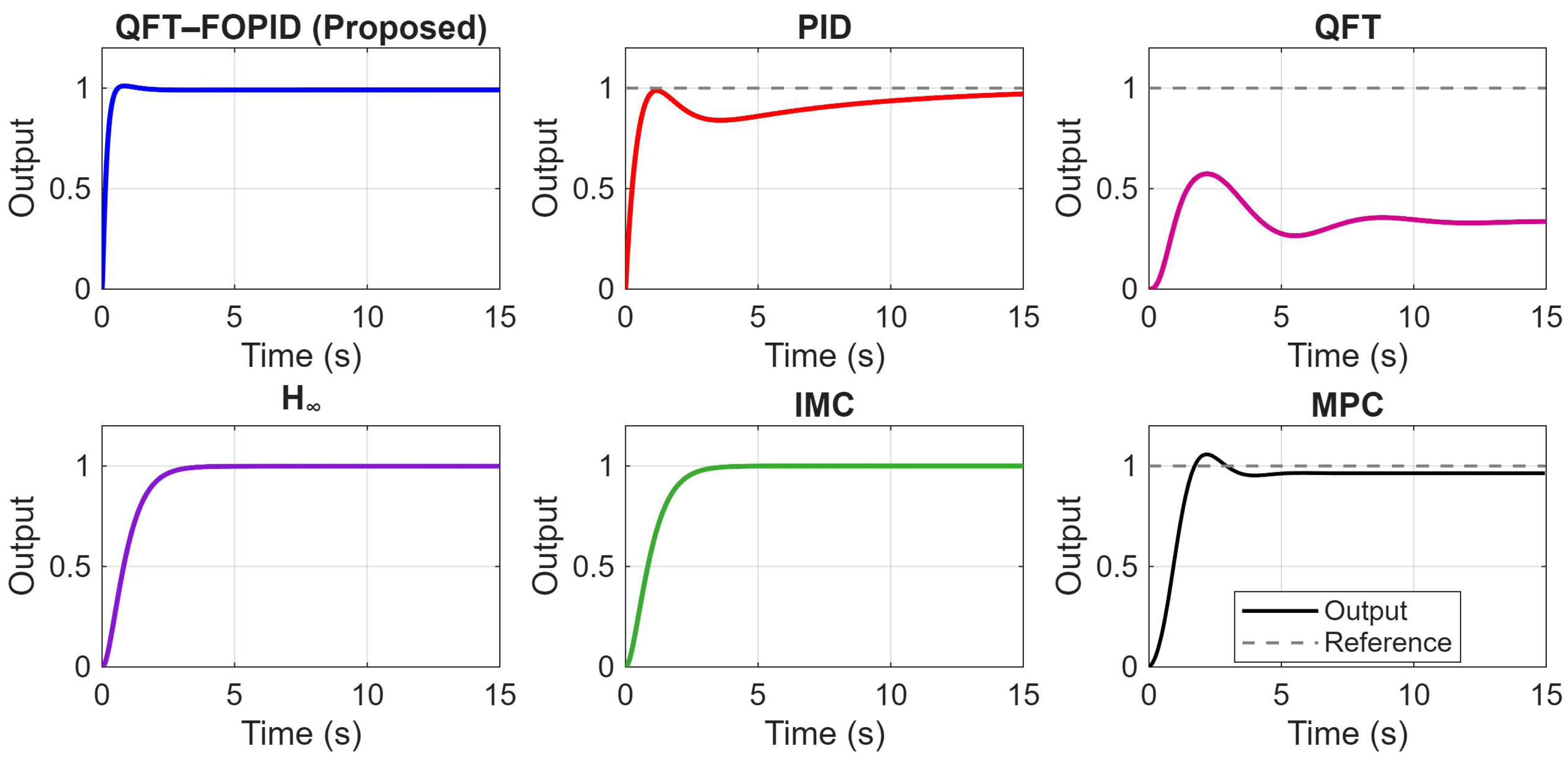

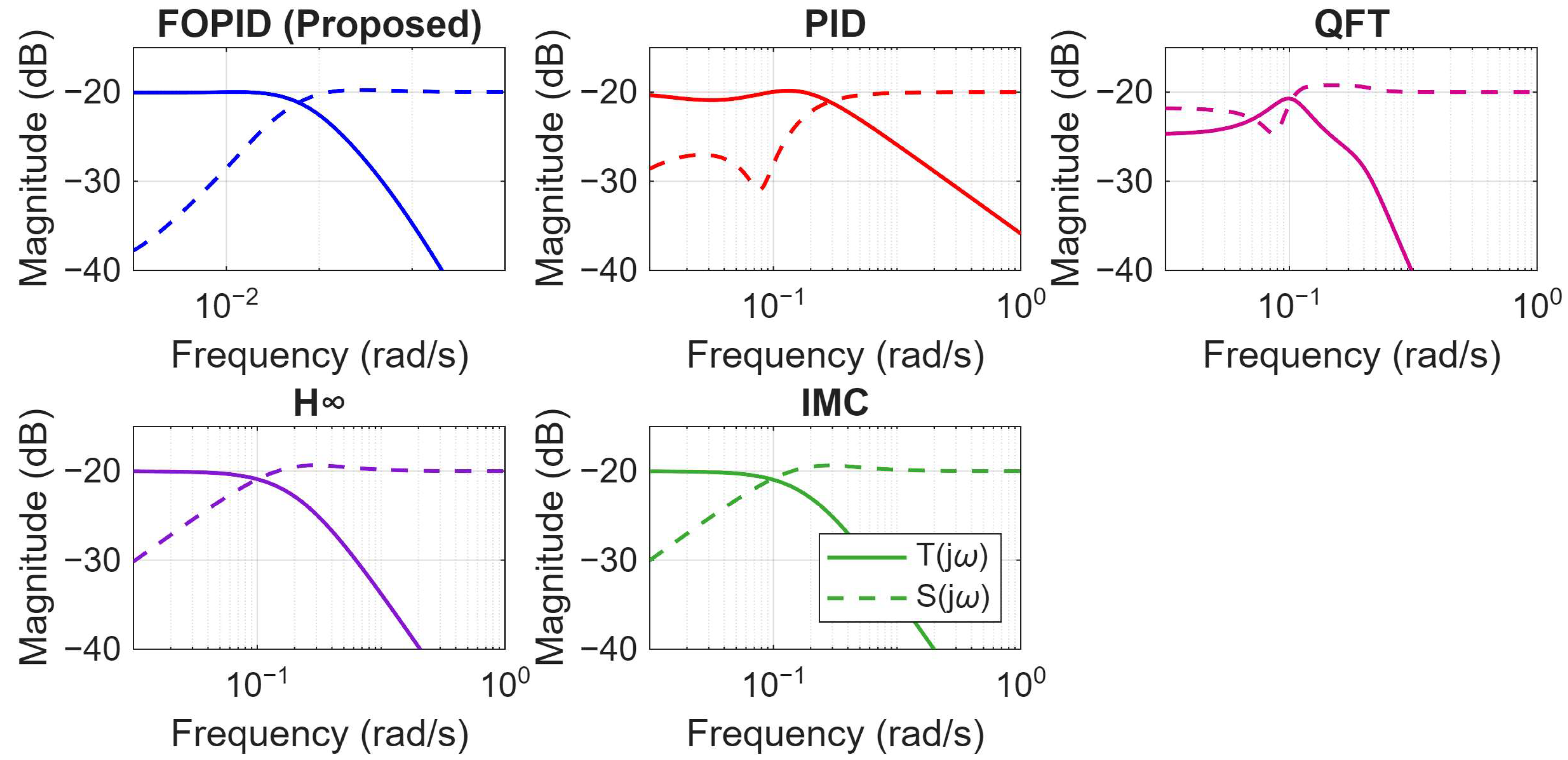

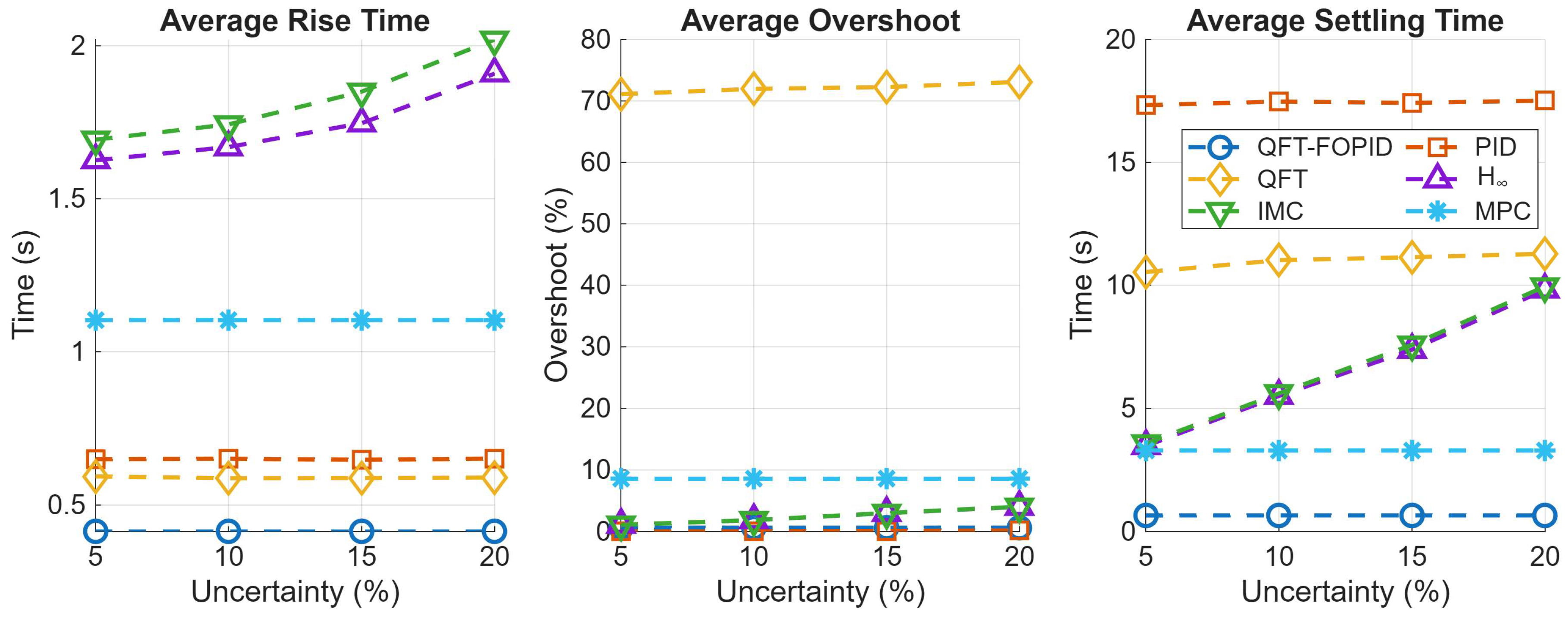

5. Comparison of the Proposed Controllers with Existing Works

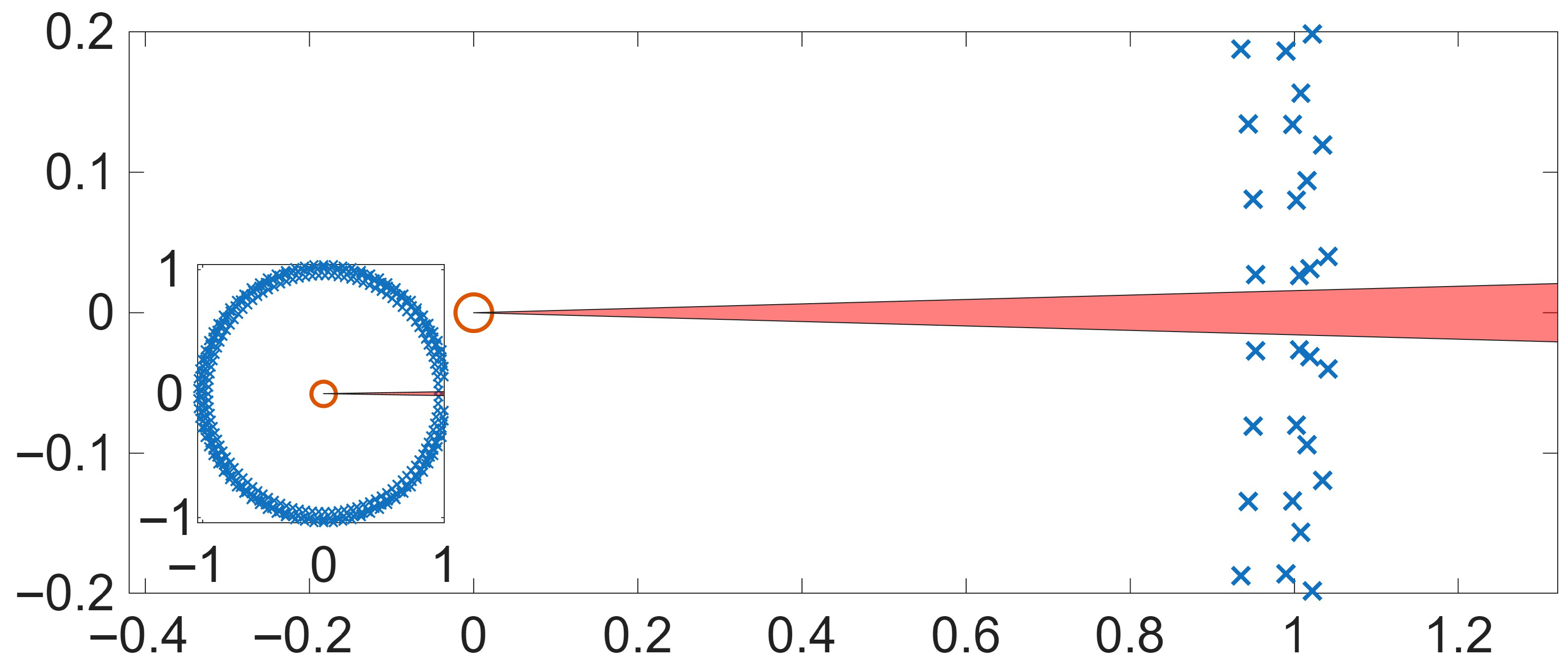

6. Sensitivity Analysis and Monte Carlo Simulations

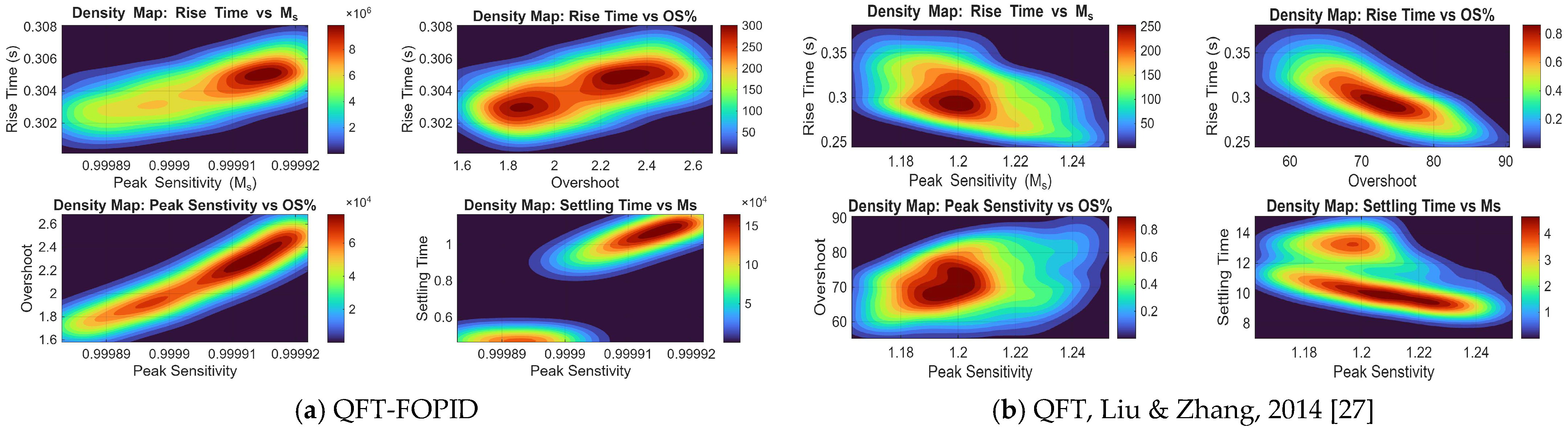

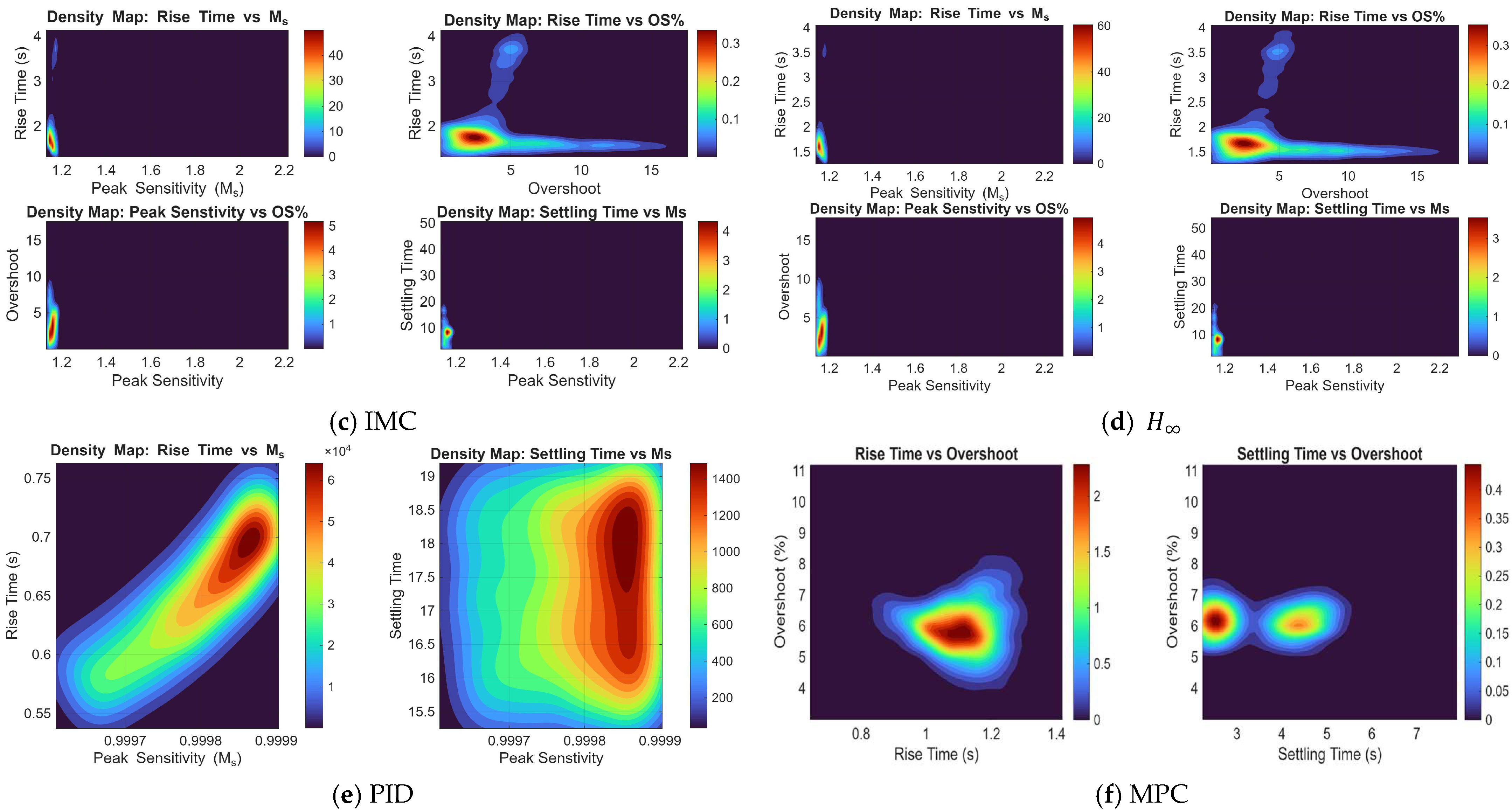

6.1. Sensitivity Analysis to Parametric Uncertainties

6.2. Monte Carlo Simulations for Uncertain Plant

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garcia-Sanz, M. Robust Control Engineering: Practical QFT Solutions; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gera, A.; Horowitz, I. Optimization of the Loop Transfer Function. Int. J. Control 1980, 31, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chait, Y.; Chen, Q.; Hollot, C.V. Automatic Loop-Shaping of QFT Controllers via Linear Programming. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 1999, 121, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaniv, O.; Nagurka, M. Automatic Loop Shaping of Structured Controllers Satisfying QFT Performance. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 2004, 127, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandakumar, R.; Halikias, G.D.; Zolotas, A. Robust Control Design of a Hydraulic Actuator Using the QFT Method. In Proceedings of the 2007 European Control Conference (ECC), Kos, Greece, 2–5 July 2007; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 2908–2915. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, K.K.; Dinh, Q.T. Self-Tuning of Quantitative Feedback Theory for Force Control of an Electro-Hydraulic Test Machine. Control Eng. Pract. 2009, 17, 1291–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sanz, M.; Guillén, J.C. Automatic Loop-Shaping of QFT Robust Controllers Via Genetic Algorithms. IFAC Proc. 2000, 33, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-H.; Ballance, D.J.; Feng, W.; Li, Y. Genetic Algorithm Enabled Computer-Automated Design of QFT Control Systems. In Proceedings of the 1999 IEEE International Symposium on Computer Aided Control System Design (Cat. No. 99TH8404), Kohala Coast, HI, USA, 27 August 1999; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 492–497. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Er, L. GA Based Automatic Design and Optimization of QFT Controller. In Proceedings of the 2006 1st International Symposium on Systems and Control in Aerospace and Astronautics, Harbin, China, 19–21 January 2006; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.-S.; Chung, C.-S. Automatic Loop-Shaping of QFT Controllers Using GAs and Evolutionary Computation. In AI 2005: Advances in Artificial Intelligence, Proceedings of the Australasian Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Sydney, Australia, 5–9 December 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 1096–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.; Xue, D. Automatic Loop Shaping in Fractional-Order QFT Controllers Using Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Control and Automation, Christchurch, New Zealand, 9–11 December 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 2182–2187. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiee, A.; Batmani, Y.; Ahmadi, F.; Bevrani, H. Robust Load-Frequency Control in Islanded Microgrids: Virtual Synchronous Generator Concept and Quantitative Feedback Theory. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 5408–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, A.; Batmani, Y.; Bevrani, H.; Kato, T. Robust Mimo Controller Design for VSC-Based Microgrids: Sequential Loop Closing Concept and Quantitative Feedback Theory. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 13, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ghosh, A. Comparison of Quantitative Feedback Theory Dependent Controller with Conventional PID and Sliding Mode Controllers on DC-DC Boost Converter for Microgrid Applications. Technol. Econ. Smart Grids Sustain. Energy 2022, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Dai, L.; Li, A.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, Z. Active Disturbance Rejection Generalized Predictive Control of a Quadrotor UAV via Quantitative Feedback Theory. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 37912–37923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, S.P.; Roy, P. Quantitative Feedback Theory-Based Multi-Variable Robust Control for Soil Quality Improvement in a Drip Irrigated Field. J. Process Control 2023, 123, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, S.P.; Sinha, A.; Baishya, S.; Roy, P. Robust Control of Water Quality in Intensive Aquaculture Using Multi-Variable Quantitative Feedback Theory: From an Indian Context. Asian J. Control 2023, 25, 2790–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Roy, P. Quantitative Feedback Theory Based Robust Control of Biomass and Substrate Concentrations in a Biochemical Reactor Exhibiting Bifurcation. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2025, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, K.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Wang, C.; Yu, B.; Liu, Y.; Kong, X. Force Compensation Control for Electro-Hydraulic Servo System with Pump–Valve Compound Drive via QFT–DTOC. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 37, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itika, R.E.; Belachew, H.Z.; Tegegn, D.F.; Salau, A.O. Improving Industrial Boiler Efficiency with Quantitative Feedback Theory-Based Controllers. Adv. Control Appl. Eng. Ind. Syst. 2025, 7, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S. Enhanced Speed Control of Pipeline Pigs with Adjustable Bypass Using Quantitative Feedback Theory and Cascade PID Algorithm. J. Pipeline Sci. Eng. 2025, 5, 100231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfia, S.N.; Jeyasenthil, R.; Kobaku, T.; Bussa, V.K. Robust Virtual Inertia Control of a Microgrid Using Quantitative Feedback Theory. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE North-East India International Energy Conversion Conference and Exhibition (NE-IECCE), Silchar, India, 4–6 July 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, F.; Lu, G. Optimization of Active Disturbance Rejection Controller for Distillation Process Based on Quantitative Feedback Theory. Processes 2025, 13, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katal, N.; Verma, P.; Mahapatro, S.R. Optimal and Simultaneous Synthesis of Fractional Order QFT Controllers and Prefilters for Non-Minimum Phase Hydro Power Systems. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 045321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chait, Y.; Yaniv, O. Multi-Input/Single-Output Computer-Aided Control Design Using the Quantitative Feedback Theory. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 1993, 3, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katal, N.; Narayan, S. Simultaneous Design of Quantitative Feedback Theory-Based Robust Controllers and Pre-Filters Using Constrained Optimization. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2023, 11, 3016–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, Z. Design of Fin Stabilizer Control System Based on Quantitative Feedback Theory. In Proceedings of the 2014 9th International Conference on Computer Science & Education, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 22–24 August 2014; pp. 1032–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, I.M. Synthesis of Feedback Systems; Academic Press: London, UK, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Hori, Y. Fractional-Order Control: Theory and Applications in Motion Control [Past and Present]. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2007, 1, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepljakov, A. FOMCON: Fractional-Order Modeling and Control Toolbox. In Fractional-Order Modeling and Control of Dynamic Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 107–129. [Google Scholar]

| Performance Metric | Nominal Plant | Uncertain Plant |

|---|---|---|

| Rise Time (s) | 0.310 | 0.320 |

| Settling Time (s) | 0.780 | 1.570 |

| Overshoot Percentage | 2.01 | 5.40% |

| Gain Margin | Inf. | Inf. |

| Phase Margin | 179.88 | 102.88 |

| Peak Complementary Sensitivity | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Peak Sensitivity | 1.059 | 1.06 |

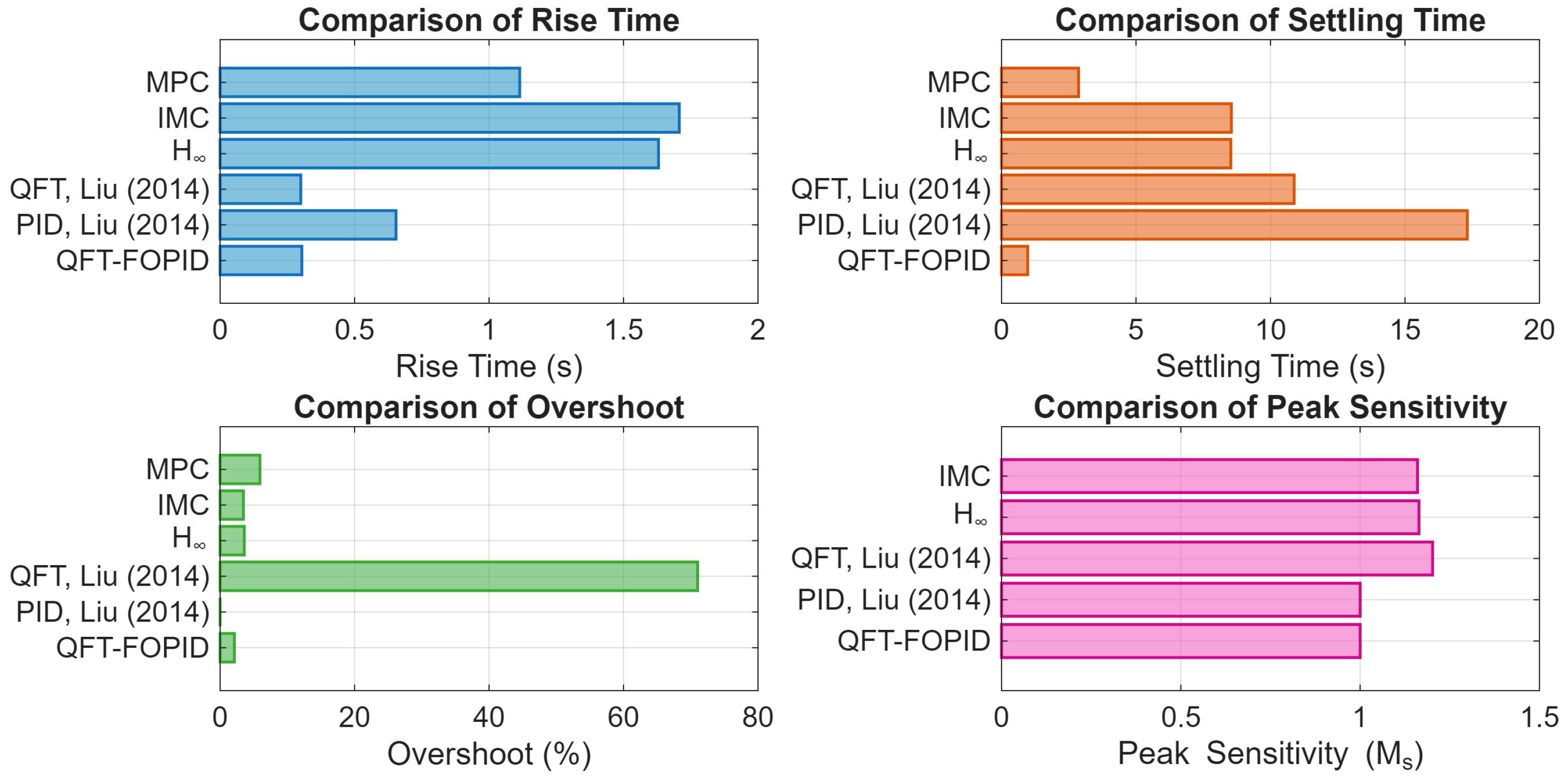

| Performance Metric | Proposed | PID [27] | QFT [27] | IMC | MPC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rise Time (s) | 0.310 | 0.651 | 0.591 | 1.613 | 1.679 | 1.110 |

| Settling Time (s) | 0.780 | 17.313 | 10.279 | 2.814 | 2.918 | 3.30 |

| Overshoot Percentage % | 2.01 | 0 | 71.045 | 0 | 0 | 5.786 |

| Gain Margin | Inf. | Inf. | 7.392 | 122.684 | Inf. | - |

| Phase Margin | 179.88 | 150.299 | 4.099 | 76.229 | 76.365 | - |

| Peak Comp. Sensitivity | 1.00 | 1.038 | 0.858 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Peak Sensitivity | 1.059 | 1 | 1.194 | 1.16 | 1.154 | - |

| Uncertainty | Controller | Rise Time (s) | Overshoot (%) | Settling Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5% | QFT-FOPID | 0.414 | 0.63 | 0.656 |

| PID [27] | 0.650 | 0.00 | 17.327 | |

| QFT [27] | 0.593 | 71.10 | 10.536 | |

| 1.626 | 1.10 | 3.472 | ||

| IMC | 1.693 | 1.10 | 3.574 | |

| MPC | 1.103 | 8.55 | 3.289 | |

| 10% | QFT-FOPID | 0.414 | 0.61 | 0.656 |

| PID [27] | 0.651 | 0.02 | 17.473 | |

| QFT [27] | 0.588 | 71.96 | 11.018 | |

| 1.669 | 1.85 | 5.503 | ||

| IMC | 1.743 | 1.87 | 5.603 | |

| MPC | 1.103 | 8.55 | 3.289 | |

| 15% | QFT-FOPID | 0.414 | 0.61 | 0.656 |

| PID [27] | 0.648 | 0.08 | 17.419 | |

| QFT [27] | 0.588 | 72.26 | 11.137 | |

| 1.747 | 3.00 | 7.381 | ||

| IMC | 1.850 | 3.02 | 7.575 | |

| MPC | 1.103 | 8.55 | 3.289 | |

| 20% | QFT-FOPID | 0.414 | 0.62 | 0.656 |

| PID [27] | 0.651 | 0.18 | 17.513 | |

| QFT [27] | 0.590 | 73.11 | 11.279 | |

| 1.909 | 4.01 | 9.815 | ||

| IMC | 2.021 | 4.04 | 9.948 | |

| MPC | 1.103 | 8.55 | 3.289 |

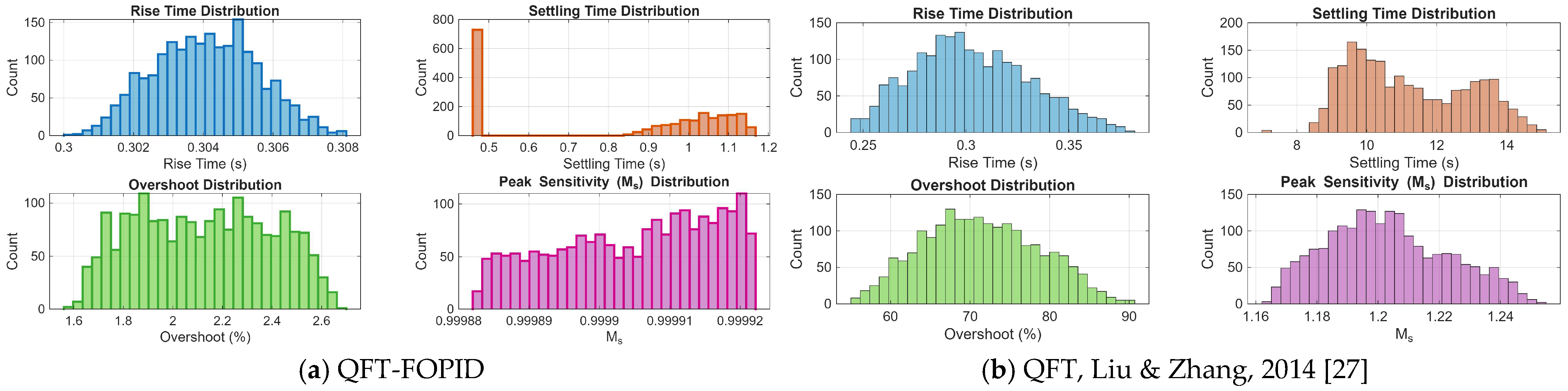

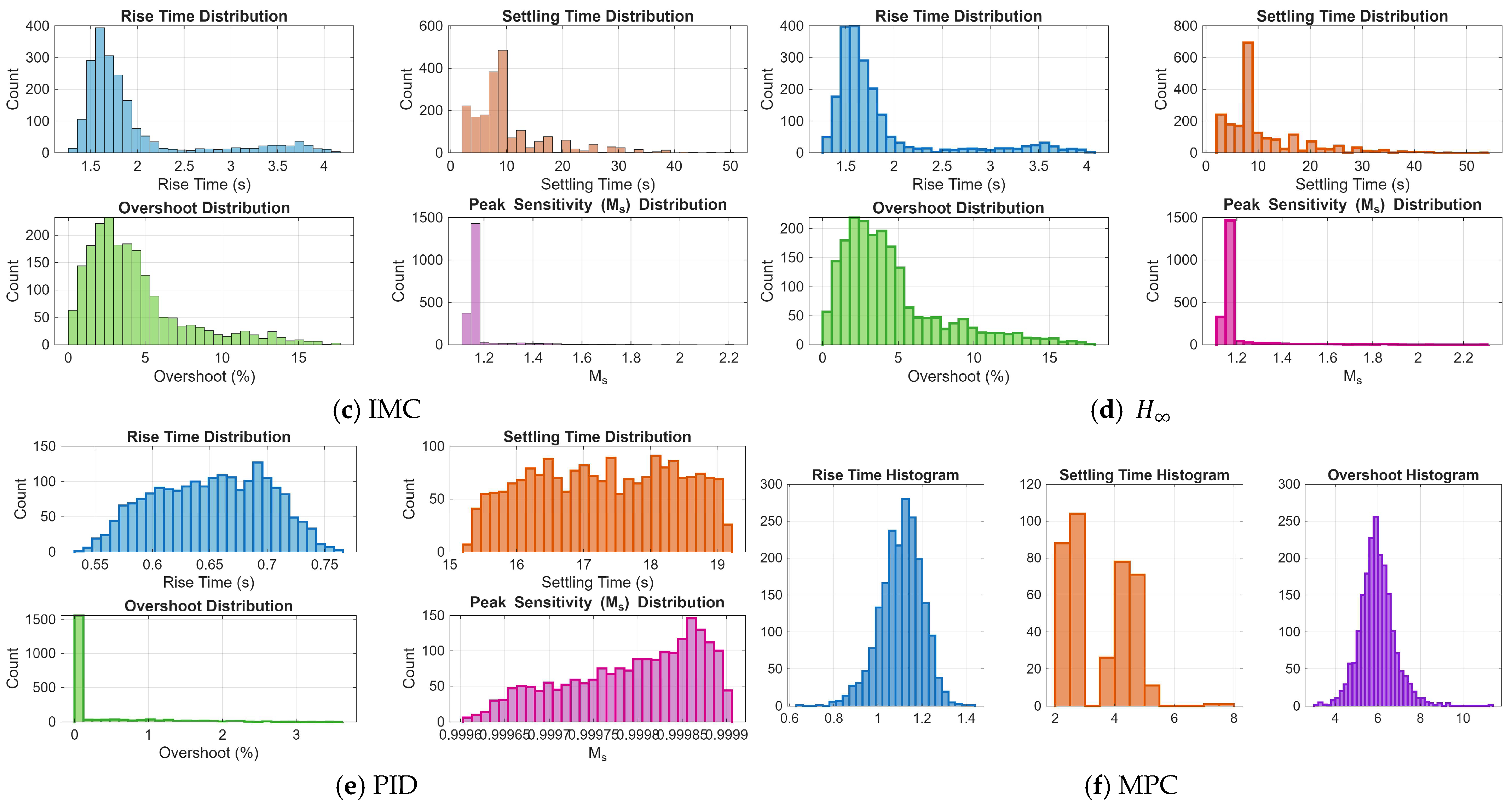

| Controller | Metric | Median | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QFT | Rise time (s) | 0.304 | 0.304 | 0.001 |

| Settling time (s) | 0.974 | 0.832 | 0.280 | |

| Overshoot (%) | 2.129 | 2.125 | 0.268 | |

| Peak Sensitivity | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0 | |

| PID [27] | Rise time (s) | 0.654 | 0.651 | 0.049 |

| Settling time (s) | 17.317 | 17.303 | 1.066 | |

| Overshoot (%) | 0 | 0.245 | 0.571 | |

| Peak Sensitivity | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| QFT [27] | Rise time (s) | 0.300 | 0.303 | 0.028 |

| Settling time (s) | 10.879 | 11.203 | 1.678 | |

| Overshoot (%) | 71.019 | 71.401 | 7.215 | |

| Peak Sensitivity | 1.202 | 1.203 | 0.020 | |

| Rise time (s) | 1.630 | 1.83 | 0.582 | |

| Settling time (s) | 8.526 | 10.634 | 7.494 | |

| Overshoot (%) | 3.591 | 4.456 | 3.346 | |

| Peak Sensitivity | 1.164 | 1.188 | 0.102 | |

| IMC | Rise time (s) | 1.707 | 1.941 | 0.640 |

| Settling time (s) | 8.546 | 10.317 | 7.280 | |

| Overshoot (%) | 3.467 | 4.293 | 3.253 | |

| Peak Sensitivity | 1.160 | 1.184 | 0.104 | |

| MPC | Rise time (s) | 1.114 | 1.106 | 0.094 |

| Settling time (s) | 2.866 | 3.480 | 1.036 | |

| Overshoot (%) | 5.924 | 5.958 | 0.808 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Katal, N.; Mahapatro, S.R.; Verma, P. Automated and Concurrent Synthesis of Fractional-Order QFT Controllers for Ship Roll Stabilization Using Constrained Optimization. Automation 2026, 7, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation7010002

Katal N, Mahapatro SR, Verma P. Automated and Concurrent Synthesis of Fractional-Order QFT Controllers for Ship Roll Stabilization Using Constrained Optimization. Automation. 2026; 7(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation7010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleKatal, Nitish, Soumya Ranjan Mahapatro, and Pankaj Verma. 2026. "Automated and Concurrent Synthesis of Fractional-Order QFT Controllers for Ship Roll Stabilization Using Constrained Optimization" Automation 7, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation7010002

APA StyleKatal, N., Mahapatro, S. R., & Verma, P. (2026). Automated and Concurrent Synthesis of Fractional-Order QFT Controllers for Ship Roll Stabilization Using Constrained Optimization. Automation, 7(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation7010002