1. Introduction

Most studies and explorations in space have been carried out by scientists via numerous ground stations and large balloons launched into the air, which have revealed some of the secrets of the distant atmosphere, encouraging them to develop these balloons and replace them with similar missiles carrying various devices. Scientists have tried to launch these carriers into space such that the collected data could be transmitted to the ground station [

1]. This was achieved by Soviet astronomers with the launch of the first artificial satellite (Sputnik-1-) on 4 October 1957, which settled into a 96 min orbit around the Earth. This was followed by the American Pioneer and Explorer satellites (-1-Major and Explorer) in 1958, with which the Van Allen radiation zones surrounding the Earth were discovered.

When scientists saw the great benefits achieved by these small space stations, they developed them, increased their number, and adjusted their orbits to obtain broader and more accurate information about the Sun. These satellites have significant impacts on the Earth’s geosphere and climate [

2].

Classification of satellite orbits: After satellites are launched by propellant rockets, they enter their trajectory—which is theoretically similar to the trajectory of planetary satellites, except that it is close to the surface of the Earth—and are subjected to various disturbances that lead to deviation from their trajectory. This necessitates compensating for this deviation, usually using solar energy [

3] and programmed mechanical techniques. Thus, their orbits are often elliptical and classified as follows.

Super High Earth Orbit (SHEO): The altitude of this orbit is more than 36,000 km, and its rotation time is more than the duration of the stellar day, which is approximately 23 h, 56 min, and 4 s. These qualities are characteristic of the high Earth orbit, which is also known as the super synchronous orbit [

4]. Satellites placed in these orbits are outside the influence of the geomagnetic field (magnetosphere), the weak impact of the flattening of the Earth, and the suppression of the atmosphere, so they are more stable than previous ones and have a longer life. Most of these satellites in these orbits are used for astronomical research [

5].

High Earth Orbit (HEO): The height of these orbits is about 36,000 km, where the satellite completes one cycle within 24 h; its speed is equal to the speed of the Earth, so it appears to be constant in the sky. These satellites are used for communications and television broadcasting. Examples include the synchronous, ground, and fixed orbits [

6].

Mid-Earth Orbit (MEO): The altitude of this orbit varies between 20,000 and 10,000 km, and the duration of the satellite’s cycle is approximately 12 h. It completes two cycles per day, so it is sometimes called the Semi-Synchronous Orbit. Satellites in this orbit can be observed from the Earth station for two or more hours, which is the duration taken to cross the planetarium which the observer can see. Examples of such satellites include those of the Global Positioning System (GPS) and GLONASS. The satellites of the Global Positioning System are artificially placed at an altitude of almost 20,000 km and orbit the Earth twice a day. They are used for civil and military purposes, as well as determining sunrise and sunset times and their locations [

7].

Low Earth Orbit (LEO): The altitude of satellites in such orbits varies between 800 and 300 km, their rotation time is less than 225 min, and their speed reaches up to approximately 7.6 km/s to overcome the force of gravity due to their proximity to the Earth’s surface. Because of this high speed, they cannot be monitored from a ground station for more than 10 min. They rapidly pass through the planetarium that the observer sees. Because of their proximity to the Earth’s surface, these moons are exposed to orbital disturbances caused by the braking force of the atmosphere and the flattening of the Earth, so they are unstable moons and relatively short-lived. Examples include satellites for remote sensing, weather, photography, and reconnaissance [

8]. This type is the subject of this study.

Adaptive Optical System (AOS): Optical systems can be divided into conventional and unconventional systems, depending on the nature of their adaptation to the surrounding conditions and the associated effects on image quality. Traditional systems (passive systems) produce images whose quality depends on the type of optical system and the type of surrounding conditions, such as weather conditions, movement, vibration of the system, and movement of the body. One of the most important factors causing wave front disturbance is the difference in the refractive index of the atmospheric layers as a result of the difference in their density. This must be taken into account when using terrestrial astronomical observatories that receive images coming from space through the atmosphere [

9].

As for non-traditional systems, called adaptive optical systems (adaptive optical systems), their parameters change depending on the external stimuli surrounding them to maintain image quality. This technology was invented for the purpose of improving observation imagery by reducing disturbances (e.g., turbulence in light waves coming from the source). This technique is used in many devices, such as ground-based and space observers, as well as ordinary and digital cameras. Visual adaptation is carried out by measuring the disturbance in the foreground. These techniques include the use of mirrors or deformable lenses that change the shape of the received wave front to remove any disturbance, as shown in

Figure 1, thus producing a high-quality image. Another technique uses small optical parts (segments) that can move on multiple axes and are assembled into an adapted optical system whose parameters change automatically depending on the type of disturbance present in the received wave front. These parts can be mirrors, lenses, or any other part of the system capable of adjusting its parameters [

10].

Adaptive visual systems are divided into two types: ordinary adaptive visual systems, which are optical systems that change parameters and self-process images; and active optical systems, which process images in a very short time without the need to move the parts of the system. An adaptive optical system consists of three main parts: 1. a wave front sensor that measures turbulence in a wave; 2. a computer that calculates corrective signals for the wave front based on the sensor data; and 3. corrective devices that are used to determine the wave front’s turbulence equation [

11].

These three components are used in astronomical observations, allowing several hundred images to be processed per second. In the simplest case, the corrective devices are made up of one mirror and can be moved on two perpendicular axes, with which the motion of the image caused by atmospheric influences can be equalized with respect to the wind, temperature changes, and changes in air density, and so on. Other second-order corrections include deviations from the focus and actual photo correction, such as a mirror with an elastic surface that can be changed or a mirror made from a crystalline liquid [

12]. A flexible mirror can be used to equalize the light wave front incident on the telescope. By controlling a mirror, changes occur in the caliber beam of the laser that the telescope sends into the atmosphere.

The main medium for transmitting light waves to astronomical telescopes is the atmosphere. Since outer space is almost devoid of matter and is at an almost constant temperature, it is considered a homogeneous free medium. The Earth’s atmosphere is a large, nonlinear, and inhomogeneous medium (a nonlinear and anisotropic medium) that is constantly changing in a random way, which affects light as it propagates through it. The model providing a description of the nature of wave front disturbances entering the atmosphere was first proposed by a Russian mathematician named Andrei Kolmogorov (Kolmogorov [

13]), which is supported by a variety of experimental measurements and has been widely used in simulations of astronomical vision. Kolmogorov’s theory of turbulence in the atmosphere is based on the assumption that turbulence changes the refractive index, which affects the visual field or the electric field being diffused in the atmosphere [

14].

Adaptive optics in reflecting astronomical observatories modulate the curvature of a mirror when changing its position and inclination. Astronomical observatories are built with a large mirror at the top to accumulate sufficient light to capture clear images of celestial bodies. For this reason, certain types of ceramic glass are used. They are characterized by a low coefficient of thermal expansion, and are thin and lightweight, allowing for the formation of an image in a mirror. However, this may cause the mirror to lose some of its balance and change its shape, resulting in low-contrast images that are not fully clear. To correct these poor-quality images, the mirror rests on substrates such as pistons that move via a controller. Small piston units can be raised or lowered such that the differences in the curvature of the mirror’s surface are equalized; thus, the shape of the mirror can be adjusted to produce a clear image [

15].

Visual object tracking: Visual object tracking is a field of computer vision that is concerned with determining the status of a target object in each frame of a video. It is a subject of active research due to the many challenges and problems involved in tracking, and it has applications in various fields such as autonomous driving, space, military, entertainment, and security, among others [

16].

In recent decades, a large number of stalking algorithms have been developed, most notably NCC, Mean shift, MDNet, MOSSE, and others, which use various techniques to solve stalking problems. Because of the diversity of methods and techniques, we decided to focus on stalking algorithms. Deep learning techniques are used for several reasons: deep learning techniques have recently been widely used in stalking research, and a large amount of data is available to train deep learning models, such as GOT and LASOT 10k. Moreover, deep learning techniques tend to show better performance when compared to traditional techniques.

The emergence of many deep learning applications has made it possible to perform real-time tasks efficiently [

17]. This study examines the satellites of the Egyptian Space Agency in LEO to determine the amount of deviation caused by space debris and ground control errors. This study is divided into two parts: the first addresses adaptive optics and the proposed optical spectral analyzer, while the second focuses on computer vision and deep learning algorithms to develop an integrated system which is capable of tracking targets in orbit (LEO).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the methodology, including the design and implementation of the proposed optical adaptive optics system and the development of a stalking algorithm.

Section 4 presents the results and testing of the comprehensive optical hardware and software algorithms, followed by the conclusions.

2. Methodology of Proposed System

In this section, we review the design of the adaptive optics of the proposed system, with the following steps: 1. Designing and simulating an adapted optical system, a parabola-shaped ground-based reflecting telescope consisting of six hexagonal mirror segments forming a segmented primary mirror and a small hexagonal shape that can move along three axes. 2. Simulating a turbulent wave front entering the system by using an imaginary surface that distorts the waveform. 3. Using the ZEMAX program to change the parameters of the optical system, such as the focal length and radius, to correct wave front deformation and obtain a high-quality image. 4. Comparing the image formed by the adapted optical system to the conventional (non-adapted) system using the image evaluation tools provided by the ZEMAX program, and developing a tracking algorithm. This research focuses on single-object tracking without prior information about the target, known as general object tracking. In this context, we define the tracking process as estimating the status of the target object in successive frames of a video based only on its appearance in the first frame.

The AOS-corrected images are used directly as input to the SwinTrack-Tiny model. The deep learning tracker was trained on GOT-10k data but evaluated on the AOS-enhanced image sequence, ensuring that temporal template updates are applied to aberration-free frames.

The condition of the object can be represented by a rectangle surrounding it in each frame of the video, referred to as the bounding box; it is manually selected in the first frame, and what is inside the rectangle is the template. After selecting the template in the first frame, a new frame from the video is chosen, and the task is to estimate the surrounding rectangle for the object in the new frame. For this purpose, we truncate the area around the target location in the previous frame by a certain size (for example, four times the previous surrounding rectangle), and this area is referred to as the search window.

2.1. The Optical System Design and Implementation

Optical design refers to the calculation of variable optical parameters that meet a range of performance requirements and constraints, including cost and manufacturing constraints. Performance parameters include types of surface shapes (e.g., spherical, aspheric, plane), the radius of the curvature, the distance to the next surface (thickness), the type of materials used (glass, plastic, or mirrors), and the diameter of the input hole (entrance pupil diameter). The requirements for optical design are as follows [

17]:

Optical performance, which includes determining special parameters—such as the design size, location, and alignment—that influence the overall shape of the design. It also includes the evaluation of the quality of the optical system, which is assessed by a set of analysis methods provided by optical design programs, with the most important analysis methods being the optical transfer function, optical transition function, enclosed energy (accumulated energy), and the ray propagation diagram of a point object (spot diagram).

Material requirements (material applications), such as weight, static size, dynamic size, and center of gravity, and comprehensive configuration requirements.

Environmental requirements (environmental applications such as temperature, pressure, vibration, humidity, and radiation intensity of the system). Design limitations can include the edge thickness of the lens or the mirror, the minimum and maximum distances between the lenses, the maximum angles of entry and exit of rays to and from the optical system, and the type of glass from which the refractive index and dispersion are determined [

18].

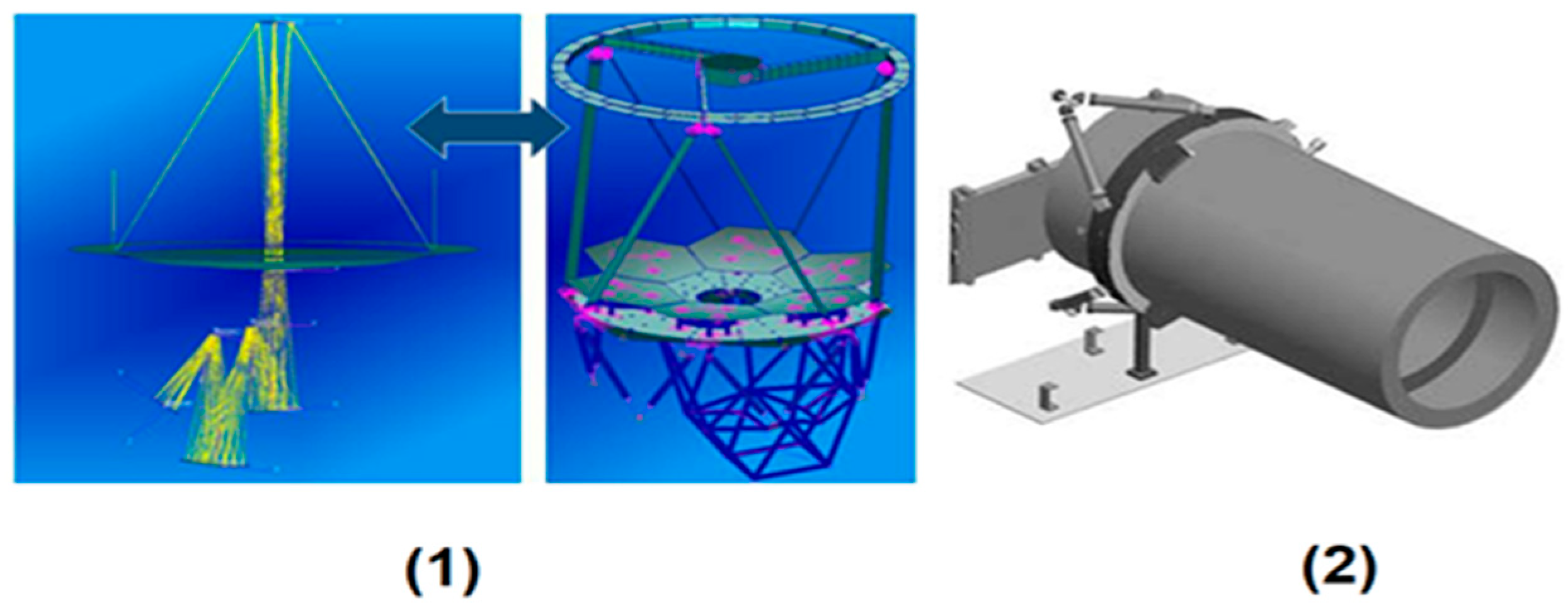

The optical system of the light-reflecting telescope consists of a set of six hexagonal segmented mirrors designed to form a parabolic mirror that reflects light toward the focal point in front of the mirror. The hexagonal shape of the mirrors gives freedom of movement to these parts along three axes (three axes of freedom) and provides a packing factor of 100%, as shown in

Figure 2.

A spectral analyzer was placed at the focal plane to discriminate star and satellite signals. The analyzer employs a 450–850 nm diffraction grating module calibrated with a reference star to ensure spectral purity.

The following equation can be used to represent the picture plane intensity distribution [

19]:

where the variables in the spatial domain are x and y. The 2D object’s distribution function is represented by the symbol O(x, y). The picture intensity distribution on the defocus planes is represented by

(x,y). On the defocus plane, the point spread function (PSF) is represented as

The relationship in the frequency domain can be expressed as follows using Fourier optics:

One way to express the generalized pupil function is

For each hexagon sub-mirror of the segmented telescope, the pupil is denoted by P (xj, yj) in the equation above. The pupil center coordinates of each sub-mirror are represented by xj, y. The circular domain function characterizes the mask’s form. The center coordinates of every mask are xsj, ysj. A mask is used to alter the pupil’s form; if the mask is positioned at the exit pupil plane, the non-opaque part of the mask controls the pupil’s shape. The information in the frequency domain may be modified to separate the impacts of tip/tilt faults and piston errors by adjusting the pupil’s shape. The aberration of the sub-mirror is denoted as ΔΦ; (x, y), which may be written as Zernike polynomials [

20]:

The PSF is recorded in the optical system using a generalized pupil function and an inverse Fourier transform:

The PSF of a single sub-aperture is

. The complex

may be obtained by taking the 2D Fourier transform of

:

The adapted optical system works to give flexibility in the main parameters of the design to be changeable in proportion to the distorted wave coming to it, and it corrects the distortion by changing the parameters. This is achieved by making the hexagonal mirrors move diagonally (decenter movement) to diverge and move closer to the center of the system to give a field of view (field of view) variant of the system.

The mirrors also move axially (tilt movement)—i.e., on the axes of their three hexagonal shapes—to give a variable ball radius of the system. The average wavelength of visible light (550 nm) was used in a direction perpendicular to the system, with an angle of incidence, followed by multiple uses of different angles of incidence to measure the effect of the angle of incidence on the quality of the image of an adapted optical system, as shown in

Figure 3(1).

The location of the actuators behind the mirrors in the proposed system improves the motor performance and accuracy, potentially increasing the power and speed of the micro-motor, which may provide additional benefits for AOS applications. Piezoelectric actuators could be integrated along the surface of the adaptive mirror in the form of an equilateral triangle, which can adjust the focal length of the adaptive optical system. In this concept, the actuators located below or on the back of the DM are lightweight and very efficient at relatively low power, since their small mass and high dynamic performance do not have frictional force.

Figure 3(2) shows the shape of the deformation resulting from stirring; the principal regulation of the closed-loop system relies on a leaky integrator.

The voltages were directly reconstructed from the measured slopes utilizing a reconstruction matrix derived from the truncated SVD technique. The condition number was established at an RMS error = 1.7746 × 10−0.8 to optimize accuracy and robustness. The tracker was constructed using a combination of a hexapod and a PDSM-241. The hexapod executed low-frequency tip/tilt adjustment at approximately 1 Hz, but the PDSM managed high-frequency correction at a rate of 2000 Hz, making it especially effective for brilliant stars.

In

Figure 3, the positions of the moving system behind the mirrors have been replaced.

Figure 4 illustrates the moving angles for each mirror separately, and

Figure 5 shows the base of the actuator motor in the proposed optical system.

The mirror included three actuators positioned 120 degrees apart and divided by h′. The mirror’s side length for PSMT is 300 mm, h is 235.2 mm, and h′ is 271.58 mm, where the actuators are the linear displacements of a certain section. The formula below provides the segment’s tip, tilt, and piston [

21]:

Equation (7) was derived following the segmented parabolic reflector adjustment method described by Wang et al. [

21]. The rotation matrix transformation between the actuator displacement vectors and mirror surface orientation was applied to compute the tip, tilt, and piston parameters for each segment.

Figure 6 shows (1) the path of the incident rays on the proposed optical system (2) and the mechanical design of the proposed adaptive optical system head. The following is a summary of this architecture: a main hexagonal mirror with six segments. A micrometric movement is presented in each section to enable precise placement.

An additional monolithic mirror is included, along with a deployable front chamber that can be rolled up for launch; once unrolled, it may be used to fine-tune the secondary mirror’s location in space, making adjustments at the entrance pupil and at the intermediate and exit pupil planes. Segmented mirrors are used for correction in both scenarios. The mirror primarily corrects the line of sight in the intermediate pupil and the nonmetric defaults in the exit pupil after in-flight phase retrieval algorithm analysis. The mirrors are made of carbon and ceramic materials, which are highly stable, as summarized in

Table 1.

The optical arrangement determines how the suggested structure will be configured. An alt-azimuthal mount will be used in the proposed system to maintain accurate tracking and pointing at wind speeds of up to 20 m/s. The suggested frame, which is made of extremely rigid steel, will maintain the optical components’ precise alignment regardless of the telescope’s orientation. All components of the mechanical system that are exposed to sunlight will be coated using a white TiO

2 paint to reduce thermal deformation.

Figure 7 displays the mechanical system setup for the suggested system, which consists of the elevation portion and the azimuth part, which are the two primary components. The mechanical system’s overall height.

The location of the hexagonal mirrors is as follows: the central piece (central segment) is placed at the location (x) 210 mm, while the second piece is adjacent to the central one, as shown in the table. The one at x = −270 mm and z = 209 mm is placed at the center segment, so the six pieces are arranged similarly to form the hexagonal telescope.

Table 2 shows the location coordinates of all six hexagonal mirrors.

The mechanical design depends on the durability of the materials used to ensure the stability of the mirrors and the absence of vibrations, which affect the formed image. The mechanical system also contains a moving system that directs the optical system in the desired direction.

Figure 8 presents the implementation of the proposed optical system, and

Figure 9 presents the proposed optical telescope in an optical protective fiber dome.

2.2. The Proposed Deep Learning Model

Most modern pursuits use only spatial information, such as the appearance of the target, as in Pig Track and others. However, there have been some attempts to take advantage of temporal information, as in the STARK algorithm, by inserting an image. The SwinTrack algorithm, which is the basic model used in our research, relies only on the template taken from the first frame as the first input and the search window as the second input. These changes are not taken into account.

Unlike STARK, which fuses temporal features through end-to-end retraining, our model employs a lightweight attention fusion block for online template updates. This achieves temporal robustness without increasing inference complexity.

The basic idea of this research is to take advantage of temporal information, as in the [

22] STARK algorithm, to modify the [

23] SwinTrack model. The image of the object generated by stalking, referred to as the dynamic template or the new template, is taken as the third input to the algorithm. As shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, which show the modification we made to the new pig backbone algorithm via the template, our algorithm extracts the attributes of the Pig Track. Thus, the attributes of the primary template and the attributes of the new template need to be merged and processed. We had several options to integrate the attributes of the new template.

The first option, as in STARK supplements and Pig Track supplements, is to concatenate the attributes of the three inputs into one string and use it as an input to the model, enabling it to capture both temporal and spatial information. This option requires an adjustment in the number of PE spatial coding weights, and therefore we will have to train these new weights with full-model training, with 23 million weights for the Pig Track-T10 model. Using our GPU NVIDIA GeForce 2080 Ti and 300 epochs, as in the original model trained on the [

24] Got10k dataset, this process may take more than a month. Therefore, a second method, in which we take advantage of the weights of the original, pre-trained model, is needed. The second option is to merge and modify the attributes of the primary template with the attributes of the template.

This method preserves the dimensions of the encoder’s input. The method proposed here is to apply basic dependency in the converter, which is the attentional dependency. On the one hand, the follower of attention ensures that the dimensions are preserved. By choosing the second option, we used the crosscutting attention follower by choosing the attributes of the modified query template and the primary template as the key and value, so the input can be determined according to the following equations [

25].

Equations (8) and (9) adapt the multi-object motion estimation relations introduced by Fang et al. [

25]; while the original work addresses relative-depth estimation, we reformulated its attention weight expression to define temporal correlation between the primary and updated templates:

where

q is a value of IUO, and p is the output of the classification grid expressing the probability of the existence of the object. The predicted perimeter rectangle is the real perimeter rectangle in the training ground data truth.

In order to train the regression network, we use the error follower generalized IOU according to the following equation:

For 0–1 = IOU, negative samples representing the background are ignored during training, and more importance is given to samples with a high probability by weighing the error GIOU. As in the STARK algorithm, an error follower consisting of the sum of the two previous weighted error followers is used to train the overall model. The weights of the model are determined using an algorithm.

3. Results and Discussion

In these experiments, we chose to train the model on the 10-GOT training dataset for the stalking process. GOT stands for Generic Object Tracking, and as it consists of more than 1000 images, it is called 10-GOT. The dataset contains more than 105 million defined perimeter rectangles and has a total size exceeding 60 GB. The videos are divided into 563 object categories and 87 movement patterns, aiming to cover as many real-life challenges as possible.

Figure 12 shows some samples from the 10-GOT dataset.

The 10-GOT dataset uses the one-shot protocol: there is no intersection between the training data and the test data in terms of the object class, except for space impurities.

Figure 13 shows the number of items and the number of videos in each collection, where the collection was tested on 420 videos, consisting of 84 object categories and 31 movement categories.

As mentioned, the basic model in our research is Pig Track, which was used in all our tests. Pig Transformer-Tiny, which uses the current Pig Track-Tiny, was the chosen model. We used the weights of the pre-trained model on the GOT-10k dataset only. The model was trained in order to add a self-attention block to combine the attributes of the primary template with the new template, as mentioned earlier. In this section, we discuss the training and test results of two experiments during the training phase; the primary template, the new template, and the search window were randomly selected from the real values of the training set from one video, as in the STARK algorithm.

To generate error curves and track system performance during training, we used the Wandb library.

Figure 14 shows the sample number on the horizontal axis, while the epoch number is on the vertical axis. It shows the values of the learning rate and training rate during the training process.

Figure 15 expresses the change in the error. We observe a decrease in the mean error curves due to the change in the weights of the model during training on the dataset.

The model was tested on the validation set after each epoch during the training process.

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 show the error curves of the classification and regression networks and the total error curve. As in the mean error curves during training, the mean error of the model on the validation data decreases after each epoch.

In the second experiment, a cross-sectional attention block with eight heads was implemented. The weights of the trained model in the first experiment were used as elementary weights, and during training, the weights were frozen except for the block weights. Training was performed using the GPU NVIDIA GeForce 3060 Ti, with 9 epochs, a batch size of 1, and selective sampling.

A reduction in RMS wave front error from 1.77 × 10−3 to 8.2 × 10−4 resulted in a 1.6% improvement in SR0.5, demonstrating that enhanced optical correction yields measurable tracking accuracy gains.

We present the results of the model testing for the previous two experiments in the validation group and test group. Since we do not have the real values of the test set and the test set does not intersect with the training and validation sets in terms of the purpose, model evaluation on the test set will be the most important because it determines the generalizability of the model.

Table 3 and

Table 4 show the test results on the 10-GOT validation set for the basic algorithm, Pig Track-Tiny, and the two experiments described earlier. Since we added an attention follower with four vertices and temporal information, we coded the model in the first experiment using SwinTrack-t4 and the model of the second experiment using 18 SwinTrack, including an attention follower with eight heads.

From

Table 4, comparing the previous algorithms in terms of speed (measured in FPS, frames per second), we observe that the attention block with template updates every 30 frames did not affect the speed for four heads, but updating every 10 frames reduced the speed by 8 FPS when using eight heads. The performance did not improve in the test on the validation data; however, when comparing the algorithms on the test set via the GOT-10k server, the performance in both experiments improved. In the first SwinTrack-t4 experiment, the percentage increased by 0.8 and 1.6% for SR0.5. The difference in the results for the test and validation groups can be explained by the overlap between the training group and the validation group.

The original model was trained for 300 epochs, while our first test model was trained for 40 epochs, and the second test model for only 9 epochs. This explains the underfitting on the training set, which overlaps with the validation set. At the same time, the weights of the basic model were frozen, and only the weights of the attention block were adjusted in the modified model, explaining the improved performance on the test set, which differs from the training and validation data. In the second 18-Pig Track experiment, the performance improved by 0.2 for AO and by 0.6 for SRos; this slight improvement in performance can be explained by the fact that the model was not sufficiently trained, as it was trained only for 9 epochs due to technical problems with the NVIDIA GeForce 2080 GPU.

It is expected that the second model’s performance will improve even more if the model is trained for longer. In both experiments, we observe a decrease in the SR0.75 value by 1.6% for the first model, and by 1.2 for the second model; this means that the tracking accuracy is lower than the basic model, but the number of frames being tracked is greater. Thus, updating the target image and combining it with the primary images in such a way may make the supplements more robust but less accurate.

As for the evaluation curves,

Figure 19 and

Figure 20 show the success and accuracy curves for the three models mentioned earlier. For the validation group, where the SwinTrack-18 model is green, the SwinTrack-t4 is blue, and the original SwinTrack-Tiny is orange, the performance of the modified models did not improve, which explains the presence of the curves of the two modified models below the original SwinTrack-Tiny model.

Using the images taken from the proposed system, we tested the previous algorithms on several videos from the validation group. The tracking results are shown in the following images, where the color of the rectangles corresponds to a specific algorithm as follows:

Large objects in green are close to the observatory target as they pass through the orbit assigned to them according to the Earth’s field.

Small objects in red are far from the observatory target as they pass through the orbit assigned to them according to the Earth’s field.