A Game-Theoretic Kendall’s Coefficient Weighting Framework for Evaluating Autonomous Path Planning Intelligence

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- We construct a three-dimensional evaluation metric system encompassing safety, efficiency, and comfort, explicitly modeling interdependencies among these metrics while ensuring observability and applicability across both “white-box” and “black-box”.

- (2)

- Since intelligence evaluation metrics are often interdependent, we accordingly select the improved Analytic Network Process (ANP) for subjective weighting due to its capacity to model metric correlations and feedback loops, and employ the CRITIC method for objective weighting as it effectively quantifies data contrast and conflict through standard deviation and correlation analysis.

- (3)

- We introduce a game-theoretic optimization model that dynamically balances subjective and objective weights by minimizing deviations through Nash equilibrium, while rigorously evaluating internal consistency using Kendall’s coefficient (for expert consensus) and coefficient of variation (for data stability). This framework harmonizes expert knowledge with data-driven insights, enhances robustness through credibility-weighted vector fusion, and significantly improves ranking consistency compared to conventional combination methods.

2. Problem Description

3. Solution

3.1. Evaluation Metrics

3.2. Game-Theoretic Kendall’s Coefficient Weighting Framework

3.2.1. Framework

- (1)

- Subjective Weighting Method: Expert judgments are aggregated and refined to derive subjective weights, explicitly accounting for interdependencies among evaluation metrics. This stage employs an enhanced group Analytic Network Process incorporating outlier filtering and optimization-based consensus fusion to enhance credibility.

- (2)

- Objective Weighting Method: Data-driven weights are computed by quantifying both the inherent contrast intensity (dispersion) within each metric and the conflict (redundancy) between metrics based on their correlation structure.

- (3)

- Combination Weighting Method: The subjective and objective weight vectors are optimally combined using a Nash equilibrium model minimizing deviation. Crucially, Kendall’s coefficient and the coefficient of variation are introduced to dynamically adjust the combination coefficients, assigning greater weight to the vector demonstrating higher internal consistency.

3.2.2. Implementation

| Algorithm 1 GTKC |

| Require: Expert evaluation matrix , Objective index data Ensure: Optimal combination weights

|

4. Experiment

4.1. Experimental Design

4.1.1. Test Scenarios

4.1.2. Logic of Progressive Verification

4.1.3. Comparative Methods

4.1.4. Algorithms Under Evaluation

4.1.5. Experimental Procedure

4.2. Case 1: Effectiveness

4.2.1. Experimental Setup

4.2.2. Results and Analysis

- Comparison between AHP-EWM (0.0602) and ANP-CRITIC (0.0925) indicates that accounting for inter-metric relationships substantially influences weight allocation, leading to a 53.65% increase in weight for .

- Further comparison between ANP-CRITIC (0.0925) and GTKC (0.1047) shows that the GTKC weight exceeds the ANP-CRITIC weight by 13.19%. This difference arises from the GTKC framework’s dynamic determination of combination coefficients (subjective-to-objective ratio = 1.27), prioritizing the more credible subjective weights derived via the improved ANP process.

- The ANP-CRITIC weight (0.1061) is 32.63% higher than the AHP-EWM weight (0.08), again underscoring the impact of considering metric interdependencies.

- The GTKC weight (0.1289) surpasses the ANP-CRITIC weight (0.1061) by 21.49%. This increase is attributed to GTKC’s consistency-driven adjustment (subjective-to-objective ratio = 1.29), favoring the more reliable subjective weights.

4.3. Case 2: Stability

4.3.1. Experimental Setup

4.3.2. Results and Analysis

- AHP: Algorithm scores demonstrated clear stratification but exhibited significant fluctuations, particularly for and .

- AHP-EWM: Evaluation values showed substantial discrepancies between algorithms, with SAC displaying pronounced upward score volatility.

- ANP-CRITIC: Moderate differences were observed between algorithm scores, and A2C showed considerably reduced fluctuations compared to AHP.

- GTKC: Algorithm scores were relatively well-differentiated and exhibited patterns broadly similar to those under ANP-CRITIC, suggesting comparable stability.

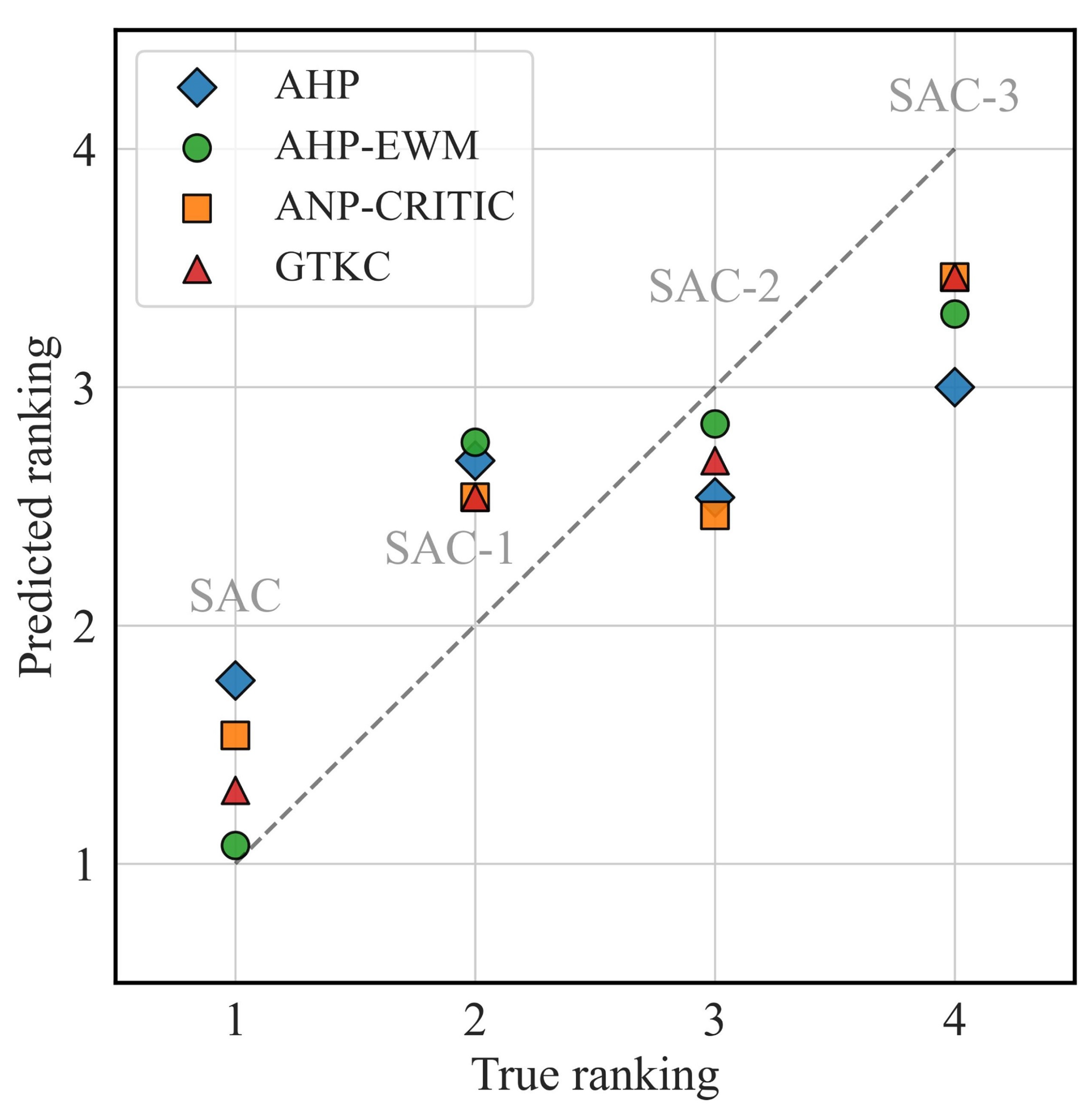

4.4. Case 3: Ranking Consistency

4.4.1. Experimental Setup

4.4.2. Results and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abed, E.H.; Fu, J.H. Local feedback stabilization and bifurcation control, I. Hopf bifurcation. Syst. Control Lett. 1986, 7, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Online Iterative Learning Enhanced Sim-to-Real Transfer for Efficient Manipulation of Deformable Objects. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 19th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI), Timisoara, Romania, 19–24 May 2025; pp. 000015–000016. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Ren, Y.; Pan, R.; Wang, L.; Chen, J. Fair and efficient electric vehicle charging scheduling optimization considering the maximum individual waiting time and operating cost. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 9808–9820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, M.; Hou, S.; Lu, H.; Luo, C.; Shi, Y. Robot Path Planning in Unknown Environments based on a Learning-guided Optimization Approach. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2025, forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, R. Autonomous Vehicles Testing Considering Utility-Based Operable Tasks. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2023, 28, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallaoui, S.; Aglzim, E.H.; Chaibet, A.; Kribèche, A. Thorough review analysis of safe control of autonomous vehicles: Path planning and navigation techniques. Energies 2022, 15, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ibáñez, J.R.; Pérez-del Pulgar, C.J.; García-Cerezo, A. Path planning for autonomous mobile robots: A review. Sensors 2021, 21, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, B.; Li, J.; Liu, T.; Xing, Y.; Lv, C.; Cao, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Hashemi, E. Risk assessment and mitigation in local path planning for autonomous vehicles with LSTM based predictive model. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 19, 2738–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wu, K.; Shen, R.; Yu, X.; Huang, S. An efficient and accurate A-star algorithm for autonomous vehicle path planning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 73, 9003–9008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Tang, J.K.T.; Bibi, K.; Xiao, S.; Ho, H.P.; Yuan, W. Robust cognitive capability in autonomous driving using sensor fusion techniques: A survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 25, 3228–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Xiang, C.; Qie, T. A model predictive trajectory tracking control strategy for heavy-duty unmanned tracked vehicle using deep Koopman operator. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 159, 111698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, K.G.; Nuevo-Gallardo, C.; Ulecia, J.M.S.; Pozas, B.M.; Bandera, C.F. Digital Twin Implementation Based on a White-Box Building Energy Model: A Case Study on Blind Control for Passive Heating. Energy Build. 2025, 349, 116454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Wei, C.; Jian, S.; Ji, Z. Preference-based deep reinforcement learning with automatic curriculum learning for map-free UGV navigation in factory-like environments. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2025, 70, 102147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xiong, G.; Song, W.; Gong, J.; Chen, H. Test and evaluation of autonomous ground vehicles. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2014, 6, 681326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilone, G.; Longo, L. Notions of explainability and evaluation approaches for explainable artificial intelligence. Inf. Fusion 2021, 76, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.N.; Meng, K.W.; Gao, L. The Entropy-Cost Function Evaluation Method for Unmanned Ground Vehicles. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 410796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, R.; Agrawal, R. Performance evaluation of weights selection schemes for linear combination of multiple forecasts. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2014, 42, 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Bai, X.; Hong, X. Site selection of nursing homes based on interval type-2 fuzzy AHP, CRITIC and improved TOPSIS methods. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 42, 3789–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H. A novel multi-criteria decision-making model for building material supplier selection based on entropy-AHP weighted TOPSIS. Entropy 2020, 22, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Qiao, J.; Huang, X.; Song, S.; Hou, H.; Jiang, T.; Rui, L.; Wang, J.; Sun, J. Apache IoTDB: A Time Series Database for Large Scale IoT Applications. ACM Trans. Database Syst. 2025, 50, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, S.; Na, X.; Sun, Y.; He, Y. Real-time continuous activity recognition with a commercial mmWave radar. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 24, 1684–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, J. An integrated architecture for intelligence evaluation of automated vehicles. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 145, 105681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Wen, H.; Deng, Y.; Chow, A.H.; Wu, Q.; Kuo, Y.H. A mixed-integer programming-based Q-learning approach for electric bus scheduling with multiple termini and service routes. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 162, 104570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Feng, S. Adaptive safety performance testing for autonomous vehicles with adaptive importance sampling. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2025, 179, 105256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. Scalable evaluation methods for autonomous vehicles. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnusdei, L.; Krstić, M.; Palmi, P.; Miglietta, P.P. Digitalization as driver to achieve circularity in the agroindustry: A SWOT-ANP-ADAM approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 882, 163441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Li, B.; Chen, X. Group Decision-Making Method of Entry Policy During a Pandemic. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2024, 29, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilham, N.I.; Dahlan, N.Y.; Hussin, M.Z. Optimizing solar PV investments: A comprehensive decision-making index using CRITIC and TOPSIS. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 49, 100551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritschy, C.; Spinler, S. The impact of autonomous trucks on business models in the automotive and logistics industry–a Delphi-based scenario study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 148, 119736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Heuvel, E.; Zhan, Z. Myths about linear and monotonic associations: Pearson’sr, Spearman’s ρ, and Kendall’s τ. Am. Stat. 2022, 76, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, J.; Moon, H.; Park, C.; Seo, J.; Eo, S.; Koo, S.; Lim, H. A survey on evaluation metrics for machine translation. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrevski, M.; Skočaj, D. Dynamic adaptive dynamic window approach. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2024, 40, 3068–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, I.; Borhan, N.; Rahiman, W. Smoothing RRT Path for Mobile Robot Navigation Using Bioinspired Optimization Method. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2024, 32, 2327–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, T. Deep reinforcement learning based mobile robot navigation: A review. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2021, 26, 674–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Ma, G.; Chen, Z.; Gao, J.; Li, P. Averaged Soft Actor-Critic for Deep Reinforcement Learning. Complexity 2021, 2021, 6658724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlova-Sergieva, V. Approach for the Assessment of Stability and Performance in the s-and z-Complex Domains. Automation 2025, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, C.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Q.; She, L.; Qing, D.; Cao, C. Urban flood risk assessment based on a combination of subjective and objective multi-weight methods. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, N.; Luo, W.; Wu, R.; Lan, H.; Qin, Y.; Su, Q. Safety evaluation of commercial vehicle driving behavior using the AHP—CRITIC algorithm. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. (Sci.) 2023, 28, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.H. Integrating subjective–objective weights consideration and a combined compromise solution method for handling supplier selection issues. Systems 2023, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, F.; Xing, H.; Li, X.; Yuan, F.; Lu, Z.; Li, X.; Ge, W. 3D geological suitability evaluation for urban underground space development based on combined weighting and improved TOPSIS. Nat. Resour. Res. 2022, 31, 693–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Algorithm | Intervention Magnitude | Intelligence Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAC | 0 | 1 | |

| SAC-1 | +60 ms | 2 | |

| SAC-2 | +160 ms | 3 | |

| SAC-3 | +380 ms | 4 | |

| SAC | 0 | 1 | |

| SAC-N1 | 0.01 | 2 | |

| SAC-N2 | 0.05 | 3 | |

| SAC-N3 | 0.10 | 4 |

| Method | Metric Weights | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstacle Collision Rate | Average Lateral Acceleration | Task Completion Time | Average Speed | Total Trajectory Length | Energy Consumption | Average Acceleration | Average Curvature | |

| AHP | 0.0747 | 0.0890 | 0.0506 | 0.2967 | 0.2877 | 0.0926 | 0.0485 | 0.0601 |

| AHP-EWM | 0.2792 | 0.0631 | 0.0602 | 0.1813 | 0.2474 | 0.0659 | 0.0530 | 0.0499 |

| ANP-CRITIC | 0.0811 | 0.0889 | 0.0925 | 0.1216 | 0.1473 | 0.1212 | 0.1690 | 0.1785 |

| GTKC | 0.0975 | 0.1060 | 0.1047 | 0.1348 | 0.2074 | 0.1349 | 0.1004 | 0.1143 |

| Weight (%) | 20.22% | 19.24% | 13.19% | 10.86% | 40.80% | 11.30% | −40.59% | −35.97% |

| Method | Metric Weights | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstacle Collision Rate | Average Lateral Acceleration | Task Completion Time | Average Speed | Total Trajectory Length | Energy Consumption | Average Acceleration | Average Curvature | |

| AHP | 0.0747 | 0.0890 | 0.0506 | 0.2967 | 0.2877 | 0.0926 | 0.0485 | 0.0601 |

| AHP-EWM | 0.1682 | 0.0593 | 0.0800 | 0.2029 | 0.2958 | 0.0664 | 0.0728 | 0.0546 |

| ANP-CRITIC | 0.1033 | 0.0766 | 0.1061 | 0.1306 | 0.1356 | 0.1055 | 0.1751 | 0.1673 |

| GTKC | 0.1211 | 0.0868 | 0.1289 | 0.1424 | 0.1872 | 0.1204 | 0.1108 | 0.1025 |

| Weight (%) | 17.23% | 13.32% | 21.49% | 9.04% | 38.05% | 14.12% | −36.72% | −38.73% |

| AHP | AHP-EWM | ANP-CRITIC | GTKC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAC | 1.77 | 1.08 | 1.54 | 1.31 | |

| SAC-1 | 2.69 | 2.77 | 2.54 | 2.54 | |

| SAC-2 | 2.54 | 2.85 | 2.46 | 2.69 | |

| SAC-3 | 3.00 | 3.31 | 3.46 | 3.46 | |

| MAE | 0.73 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.42 | |

| 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.00 | ||

| SAC | 1.00 | 1.10 | 1.20 | 1.00 | |

| SAC-N1 | 2.25 | 2.30 | 1.90 | 2.10 | |

| SAC-N2 | 3.50 | 3.30 | 3.10 | 3.20 | |

| SAC-N3 | 3.25 | 3.30 | 3.80 | 3.70 | |

| MAE | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| 0.80 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Method | Metric Weights | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstacle Collision Rate | Average Lateral Acceleration | Task Completion Time | Average Speed | Total Trajectory Length | Energy Consumption | Average Acceleration | Average Curvature | |

| AHP | 0.0747 | 0.0890 | 0.0506 | 0.2967 | 0.2877 | 0.0926 | 0.0485 | 0.0601 |

| AHP-EWM | 0.0764 | 0.0676 | 0.0329 | 0.1876 | 0.1980 | 0.0531 | 0.1825 | 0.2021 |

| ANP-CRITIC | 0.1290 | 0.0940 | 0.0630 | 0.1199 | 0.1049 | 0.0872 | 0.1993 | 0.2026 |

| GTKC | 0.1394 | 0.1107 | 0.0787 | 0.1334 | 0.1706 | 0.1051 | 0.1268 | 0.1353 |

| Weight (%) | 8.06% | 17.77% | 24.92% | 11.26% | 62.63% | 20.53% | −36.38% | −33.21% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, Z.; Yang, J.; Yuan, R.; Su, G.; Lei, M. A Game-Theoretic Kendall’s Coefficient Weighting Framework for Evaluating Autonomous Path Planning Intelligence. Automation 2025, 6, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040085

Dong Z, Yang J, Yuan R, Su G, Lei M. A Game-Theoretic Kendall’s Coefficient Weighting Framework for Evaluating Autonomous Path Planning Intelligence. Automation. 2025; 6(4):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040085

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Zewei, Jingxuan Yang, Runze Yuan, Guangzhen Su, and Ming Lei. 2025. "A Game-Theoretic Kendall’s Coefficient Weighting Framework for Evaluating Autonomous Path Planning Intelligence" Automation 6, no. 4: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040085

APA StyleDong, Z., Yang, J., Yuan, R., Su, G., & Lei, M. (2025). A Game-Theoretic Kendall’s Coefficient Weighting Framework for Evaluating Autonomous Path Planning Intelligence. Automation, 6(4), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040085