Reliable Detection of Unsafe Scenarios in Industrial Lines Using Deep Contrastive Learning with Bayesian Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

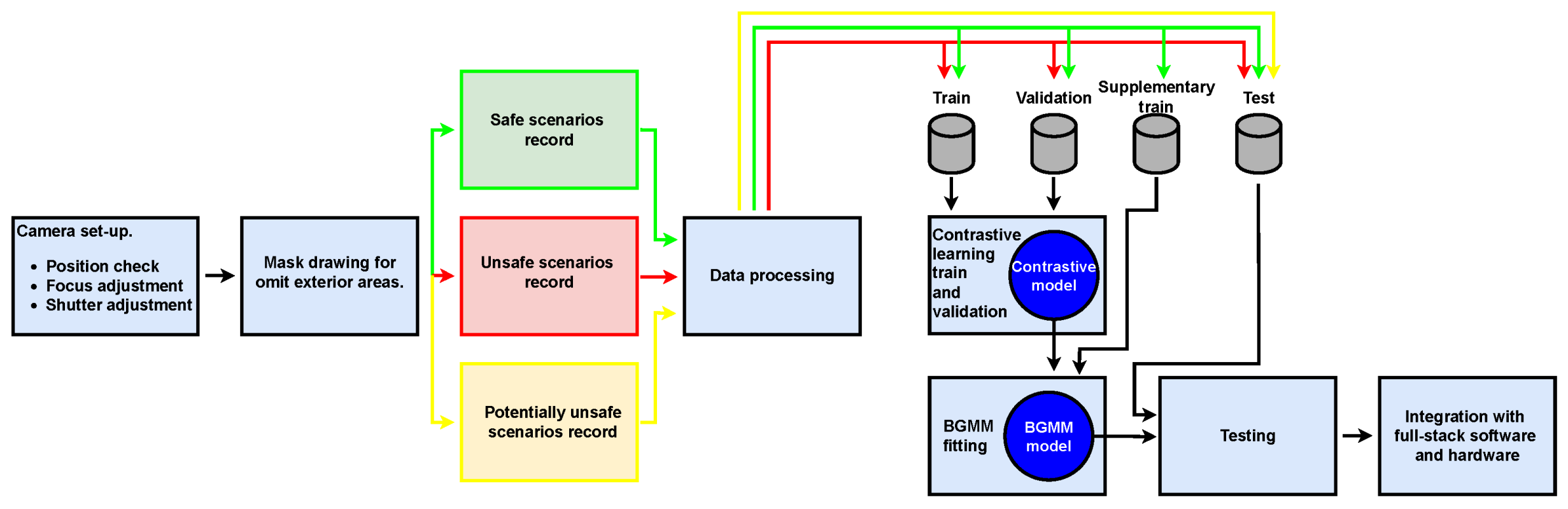

3. Methods

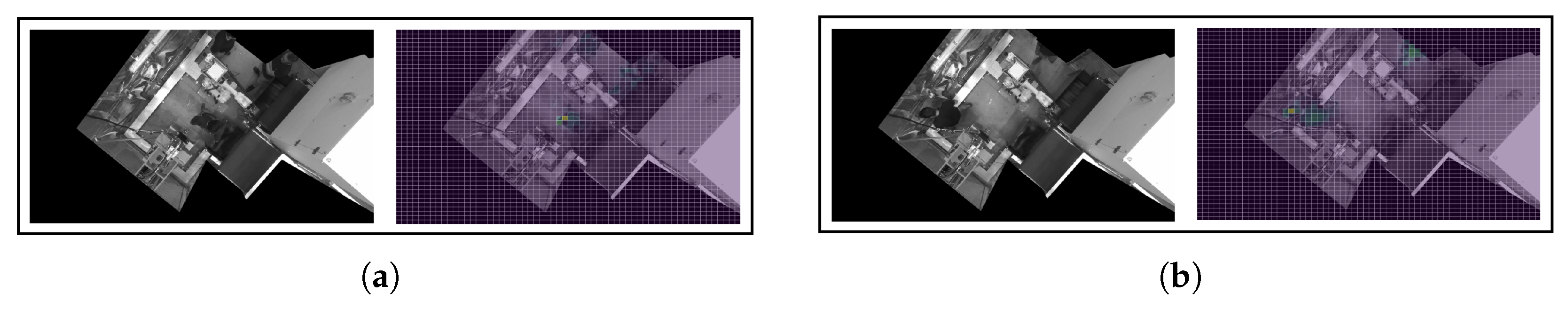

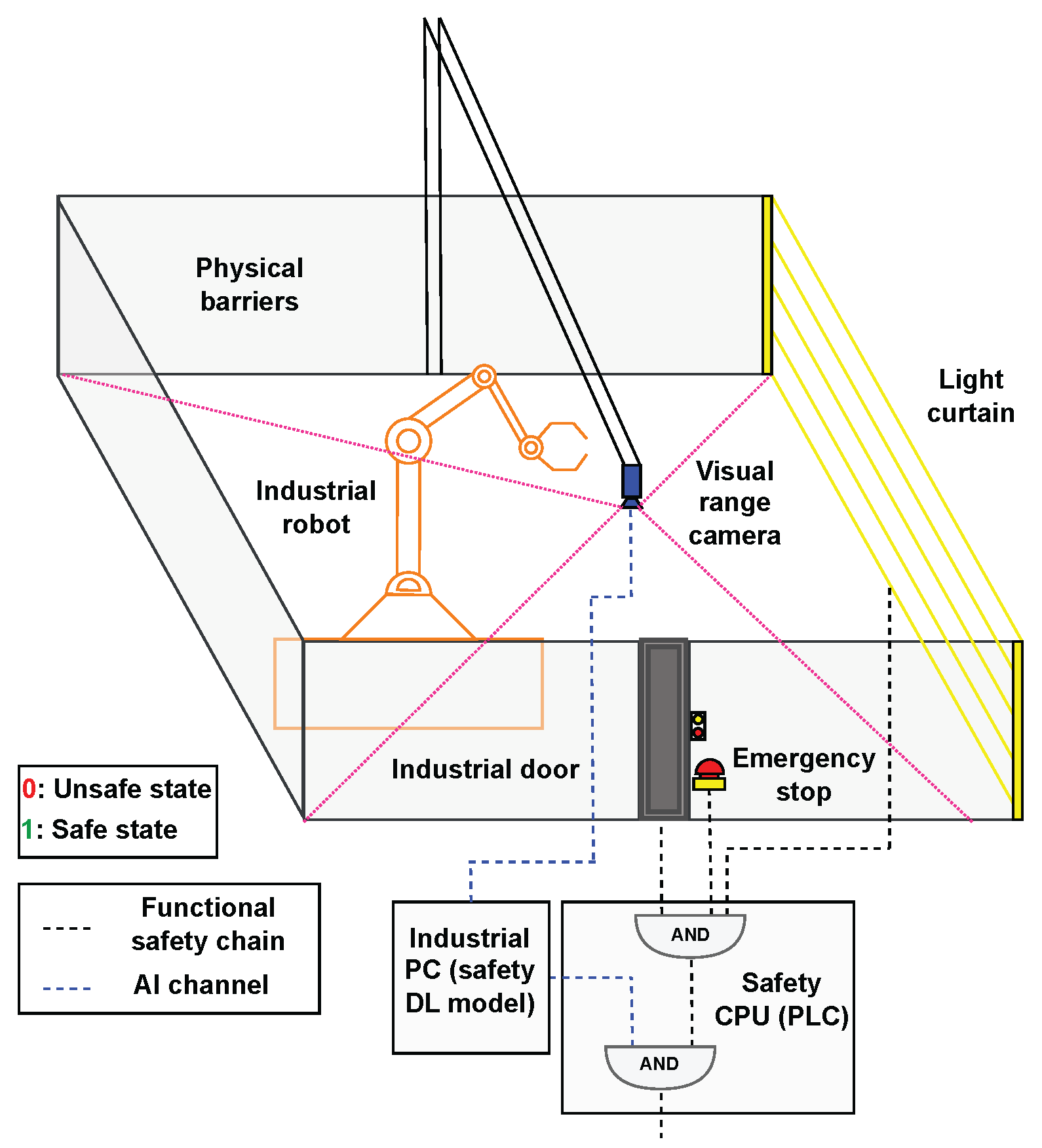

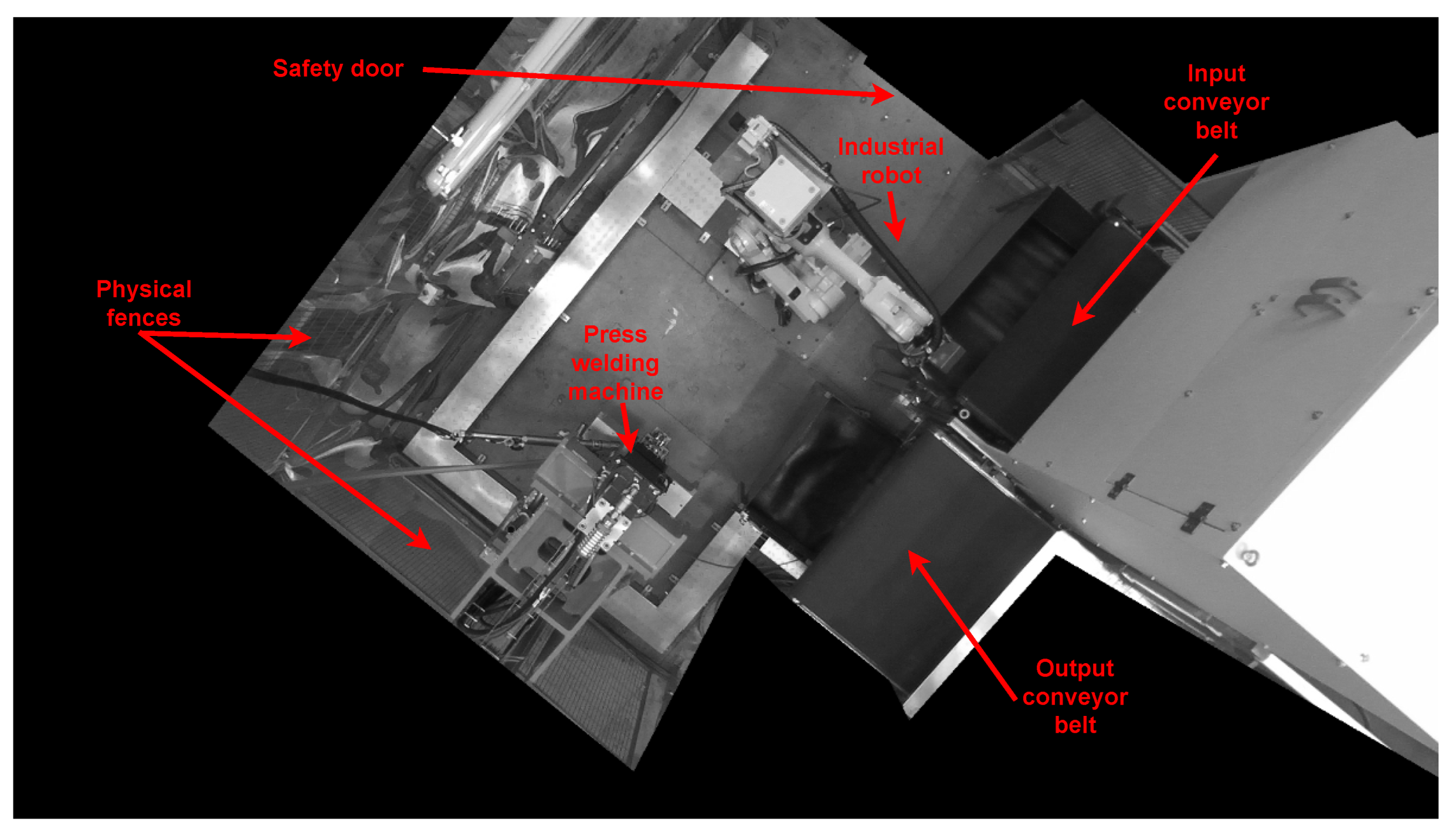

3.1. Industrial Configuration

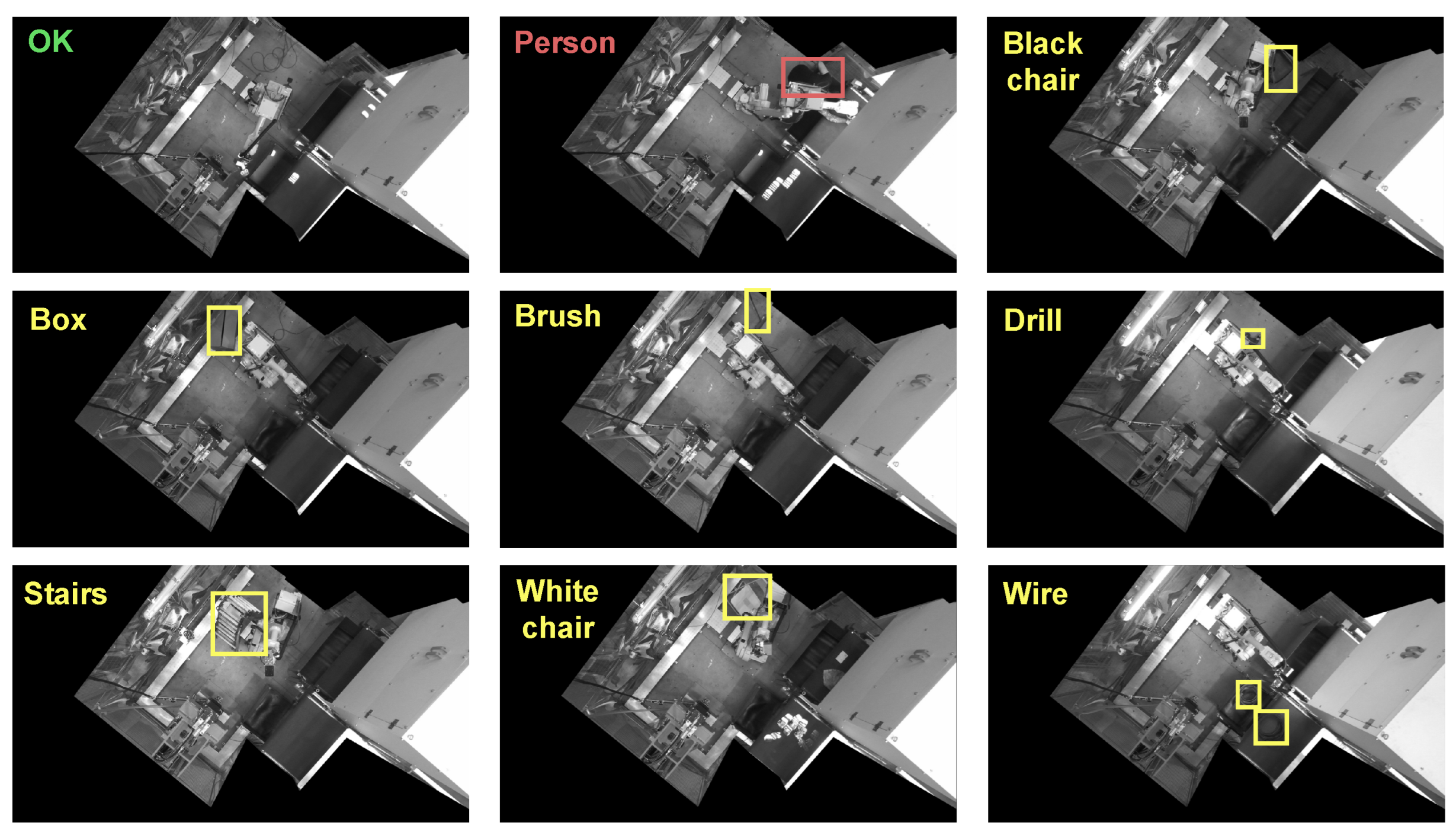

3.2. Dataset

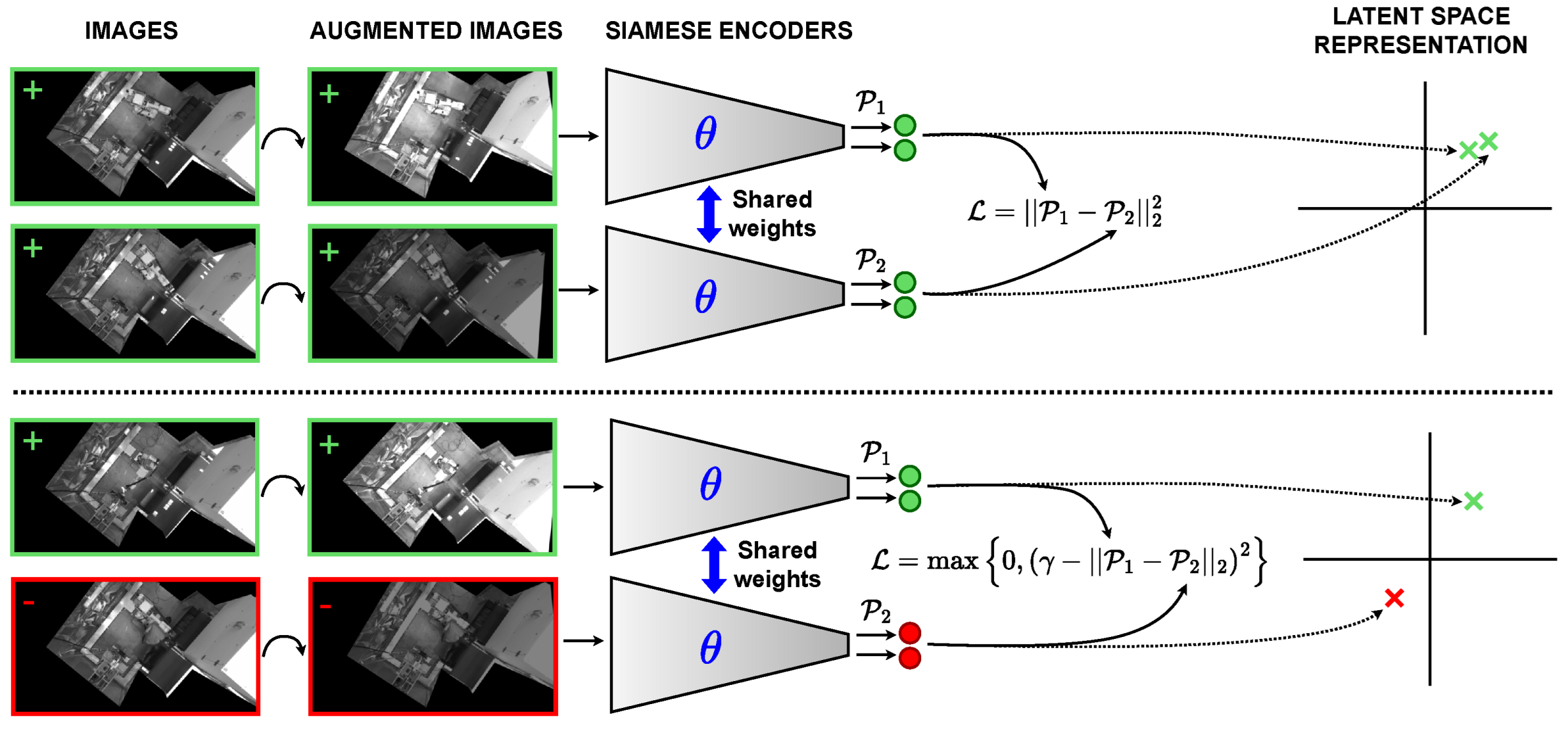

3.3. Supervised Deep Contrastive Learning

3.4. Training Specifications

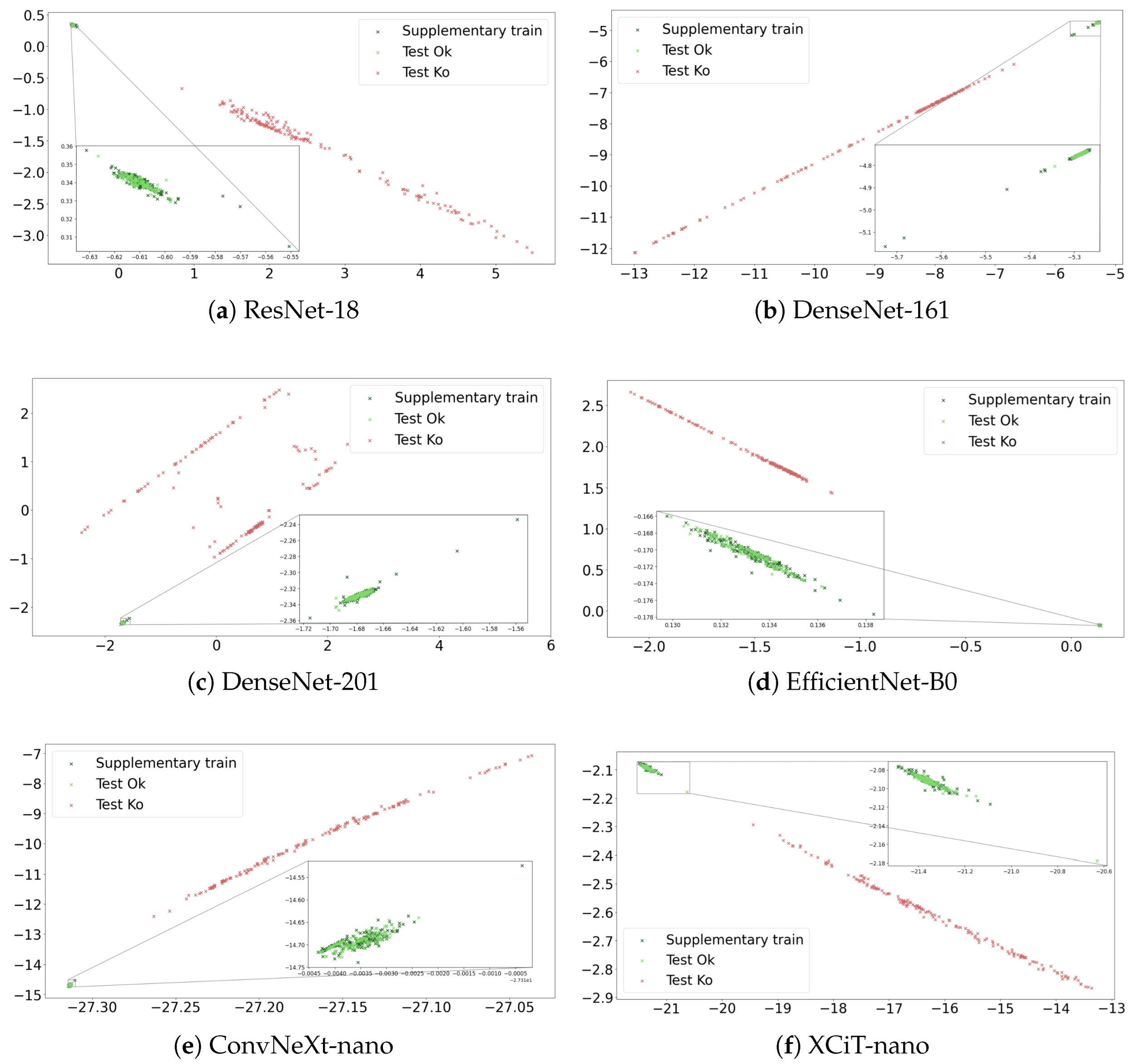

4. Experimental Results for the Base Safe/Unsafe Scenario

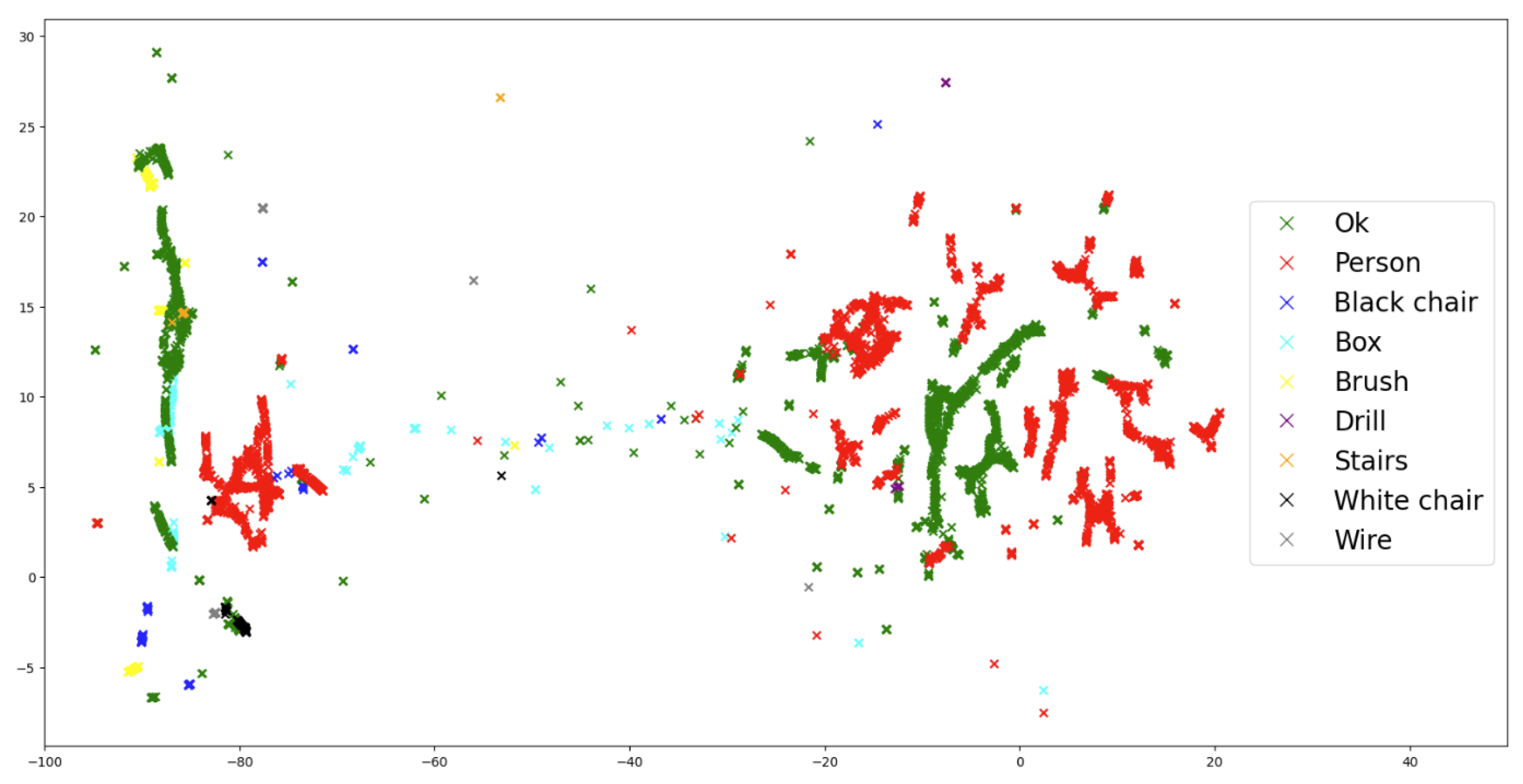

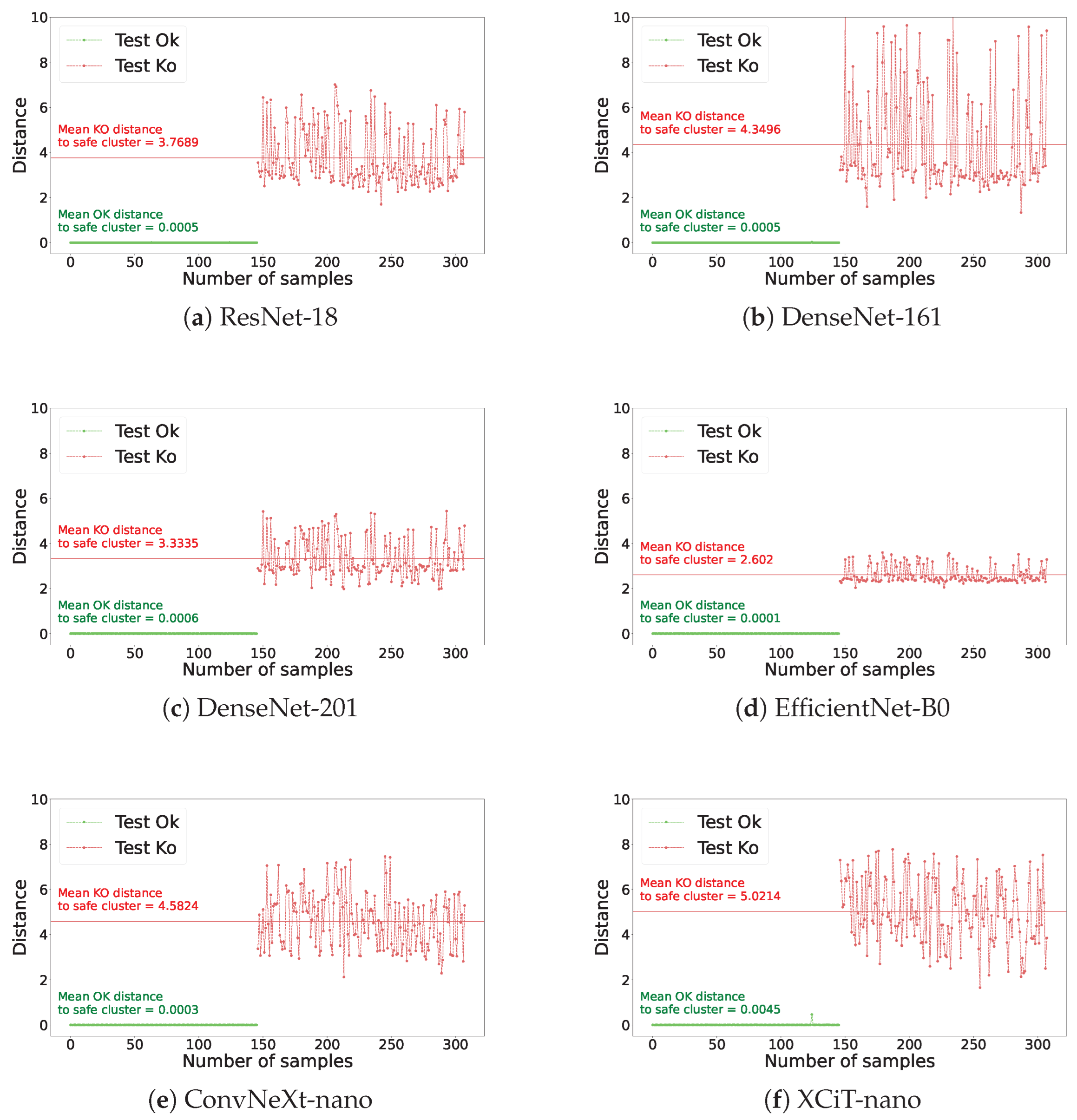

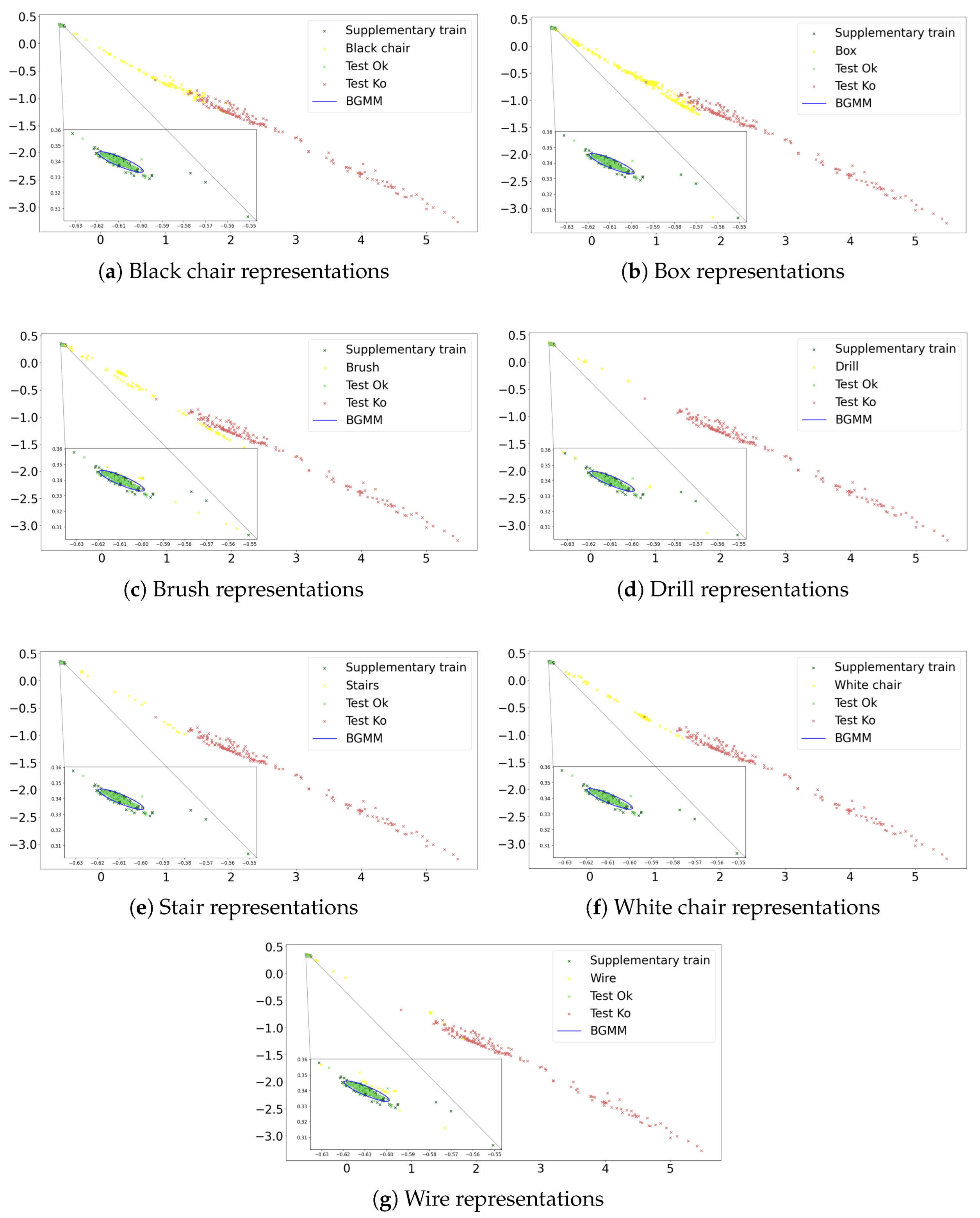

5. Generalization to Unknown Non-Legitimate Scenarios: Uncertainty Quantification

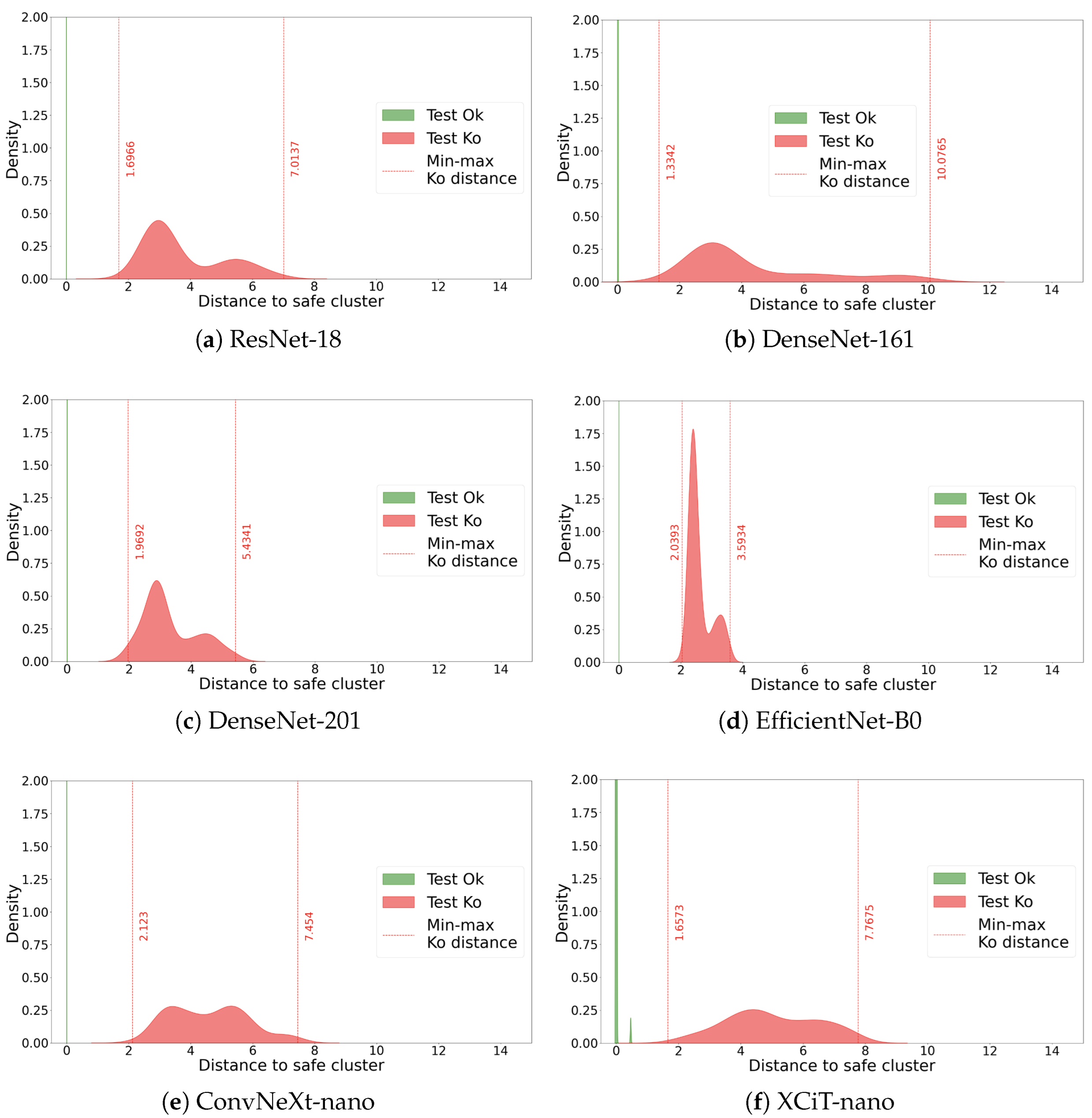

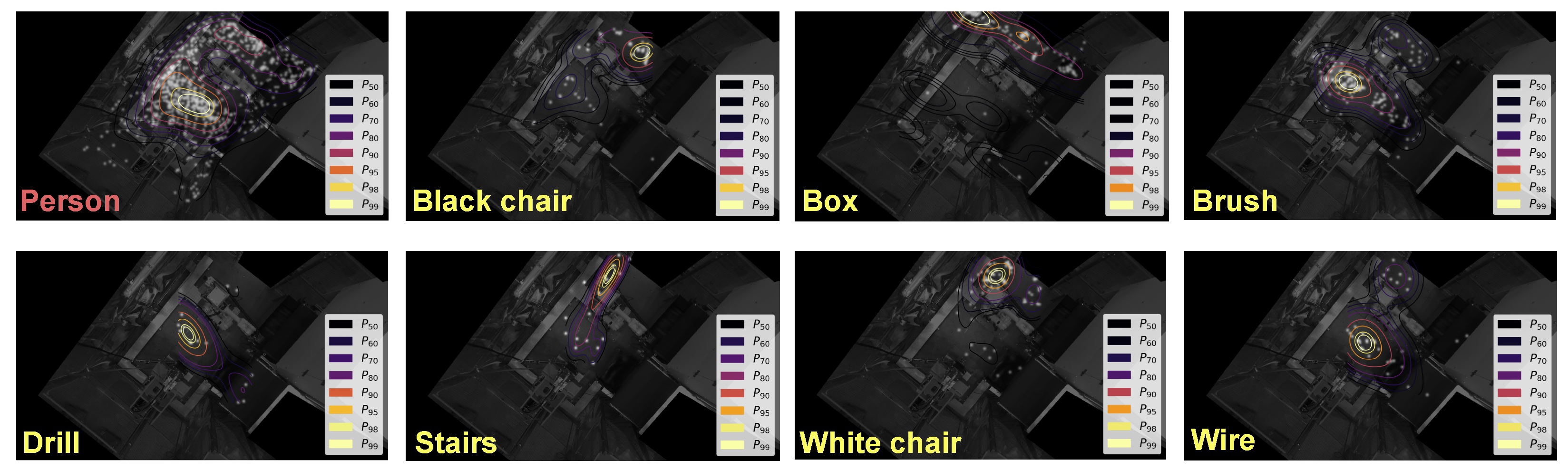

5.1. Bayesian Gaussian Mixture Model (BGMM)

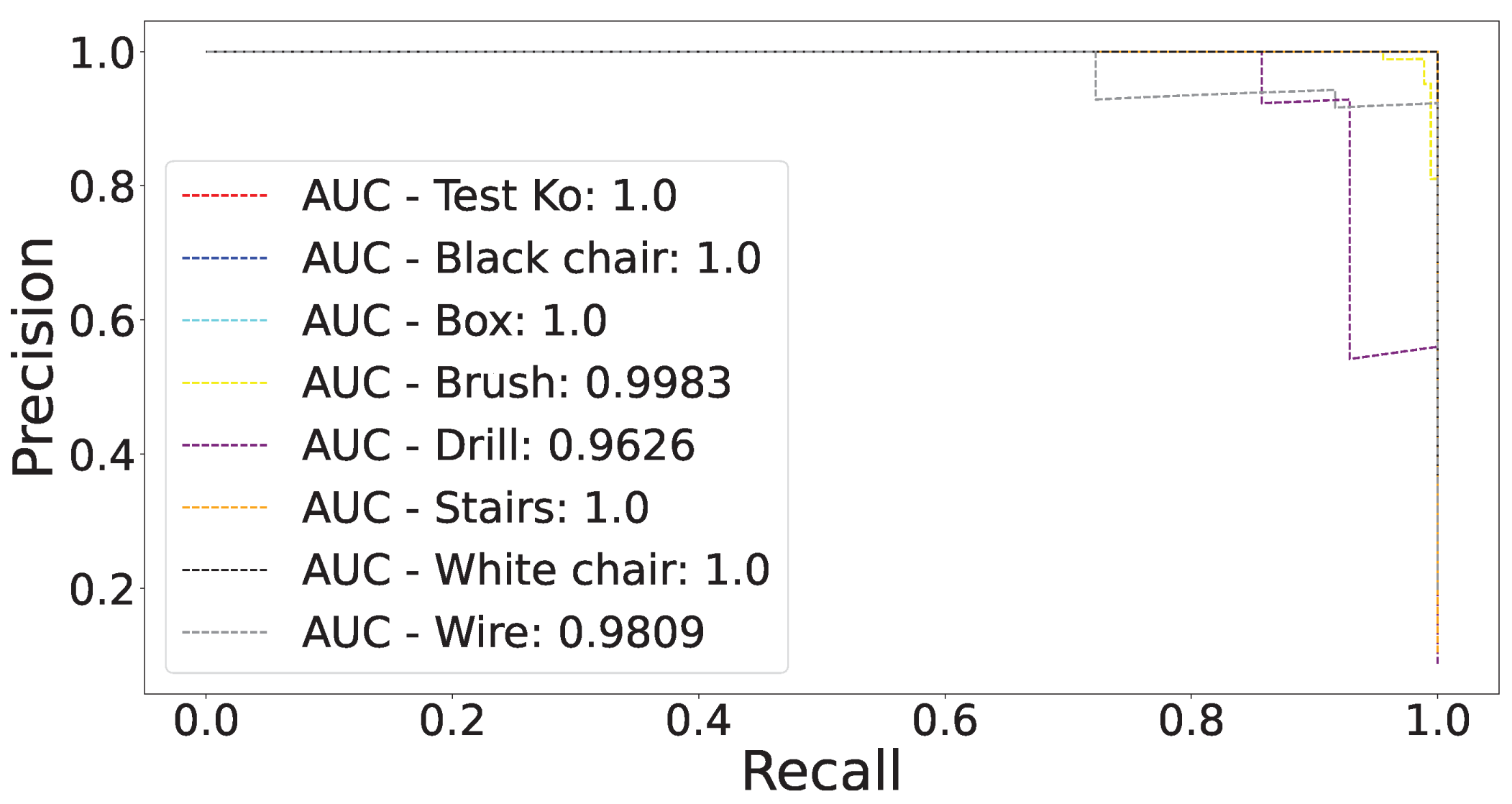

5.2. Results

5.3. Hybrid Latent Space for Performance Maximization

6. Confidence Against Uncertainty: Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI)

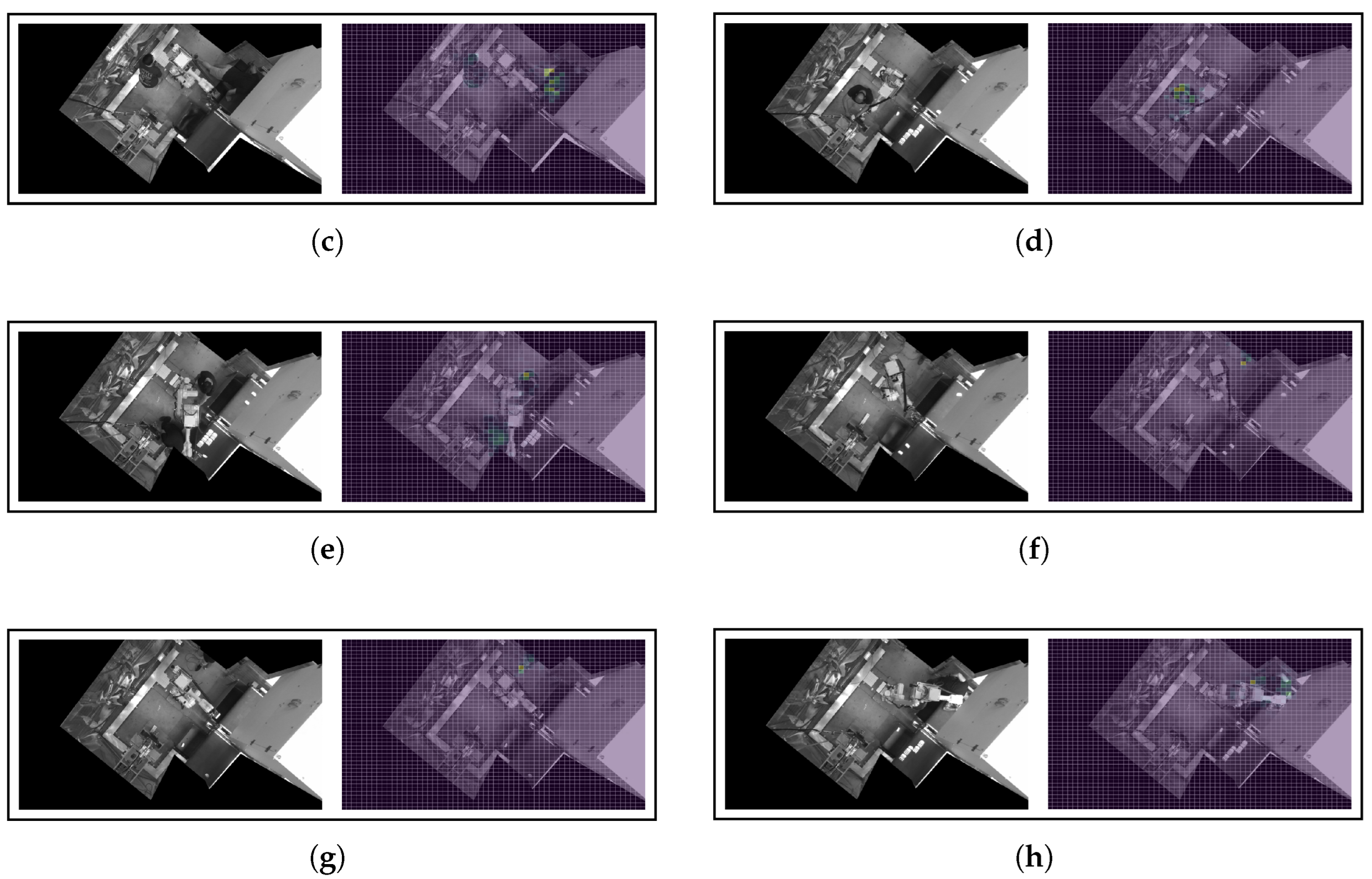

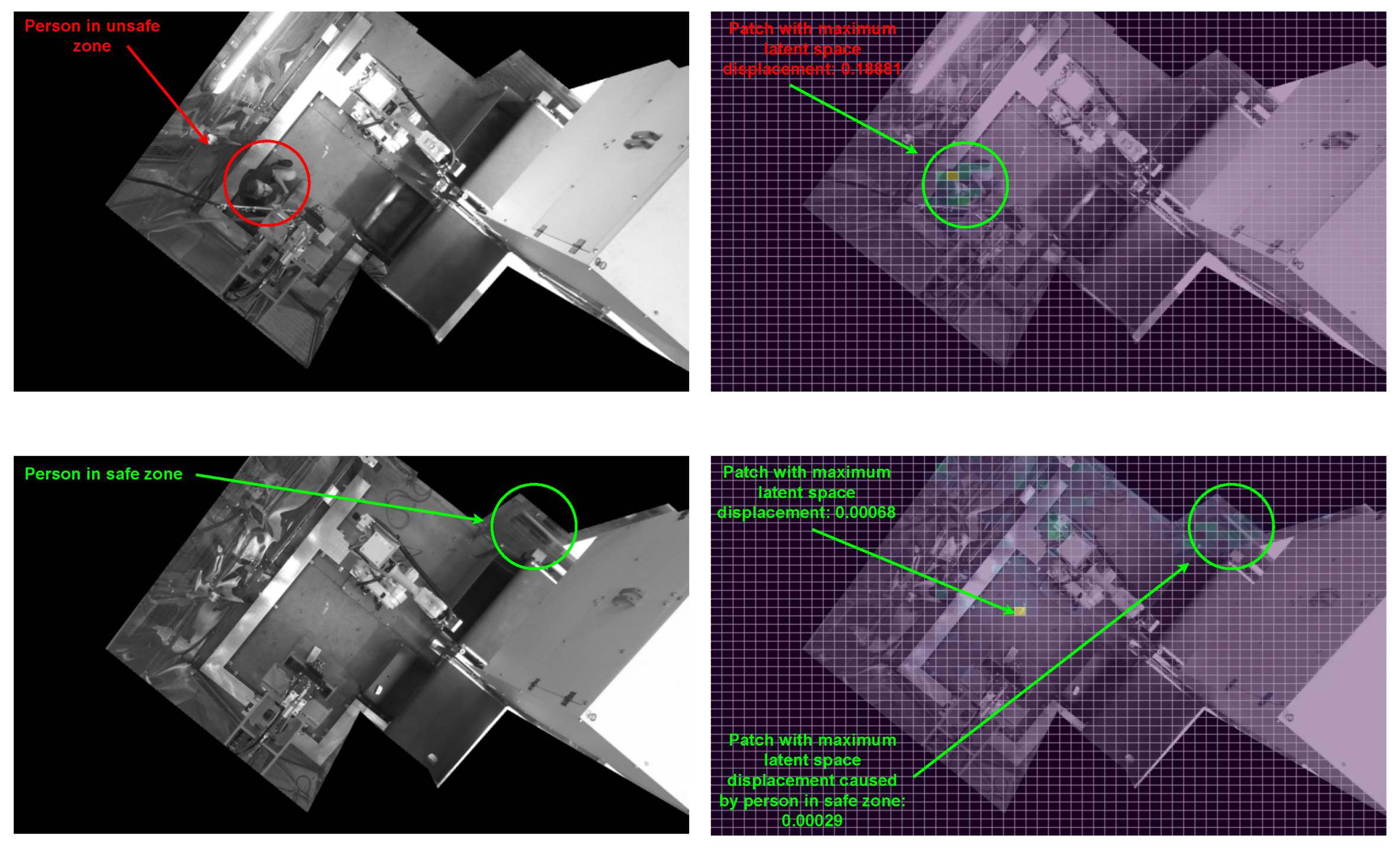

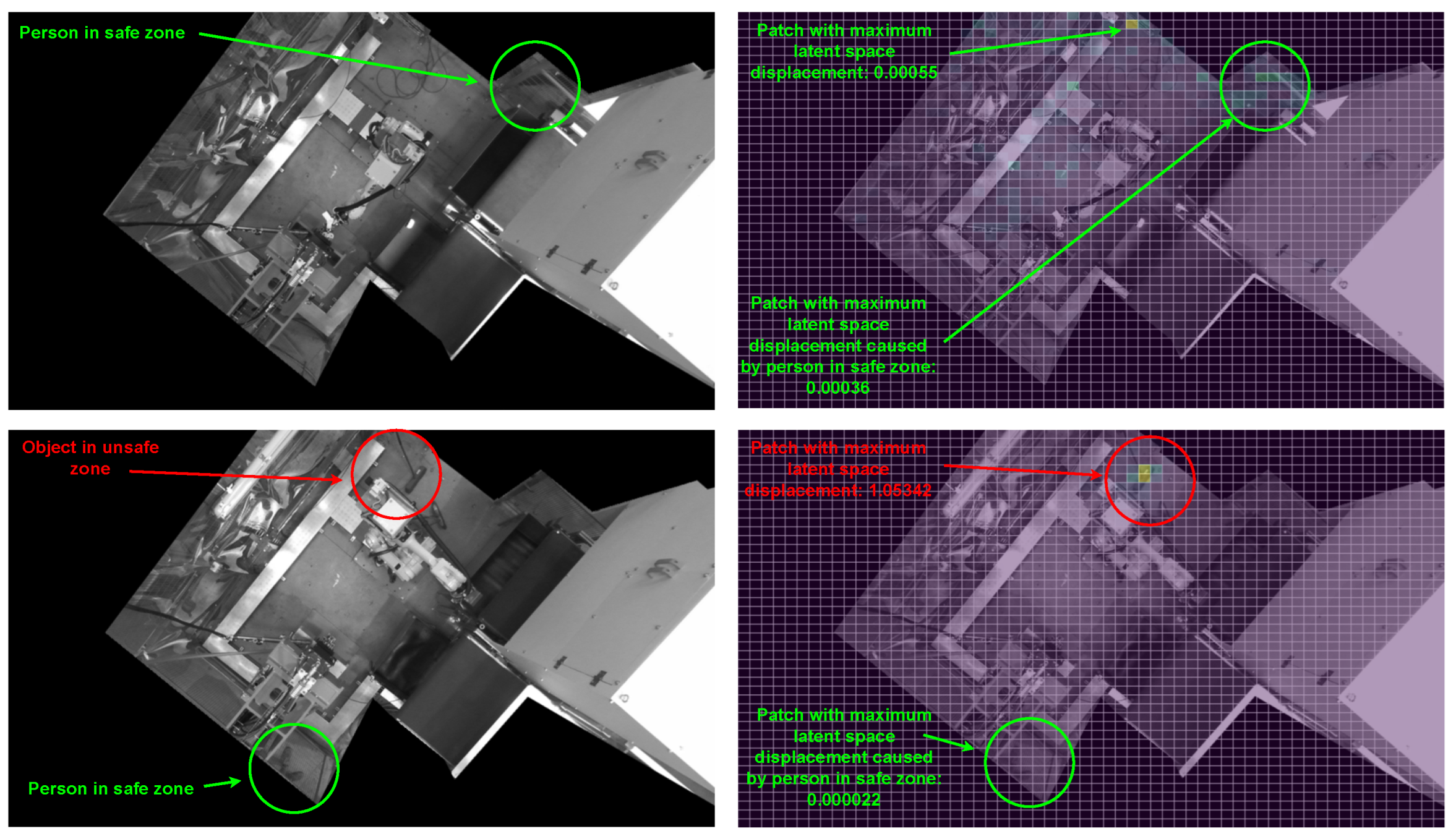

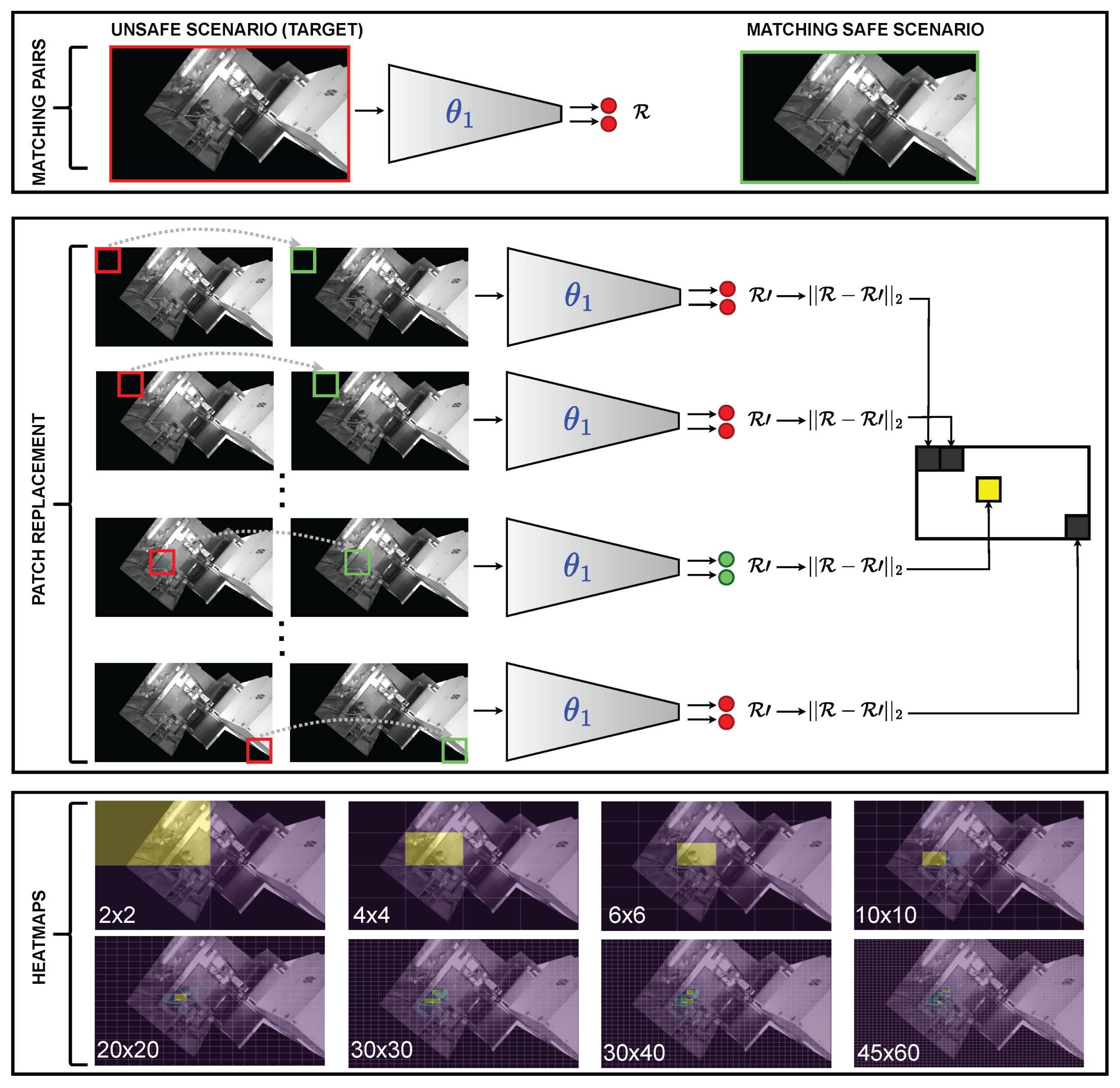

6.1. Input Feature Ablations

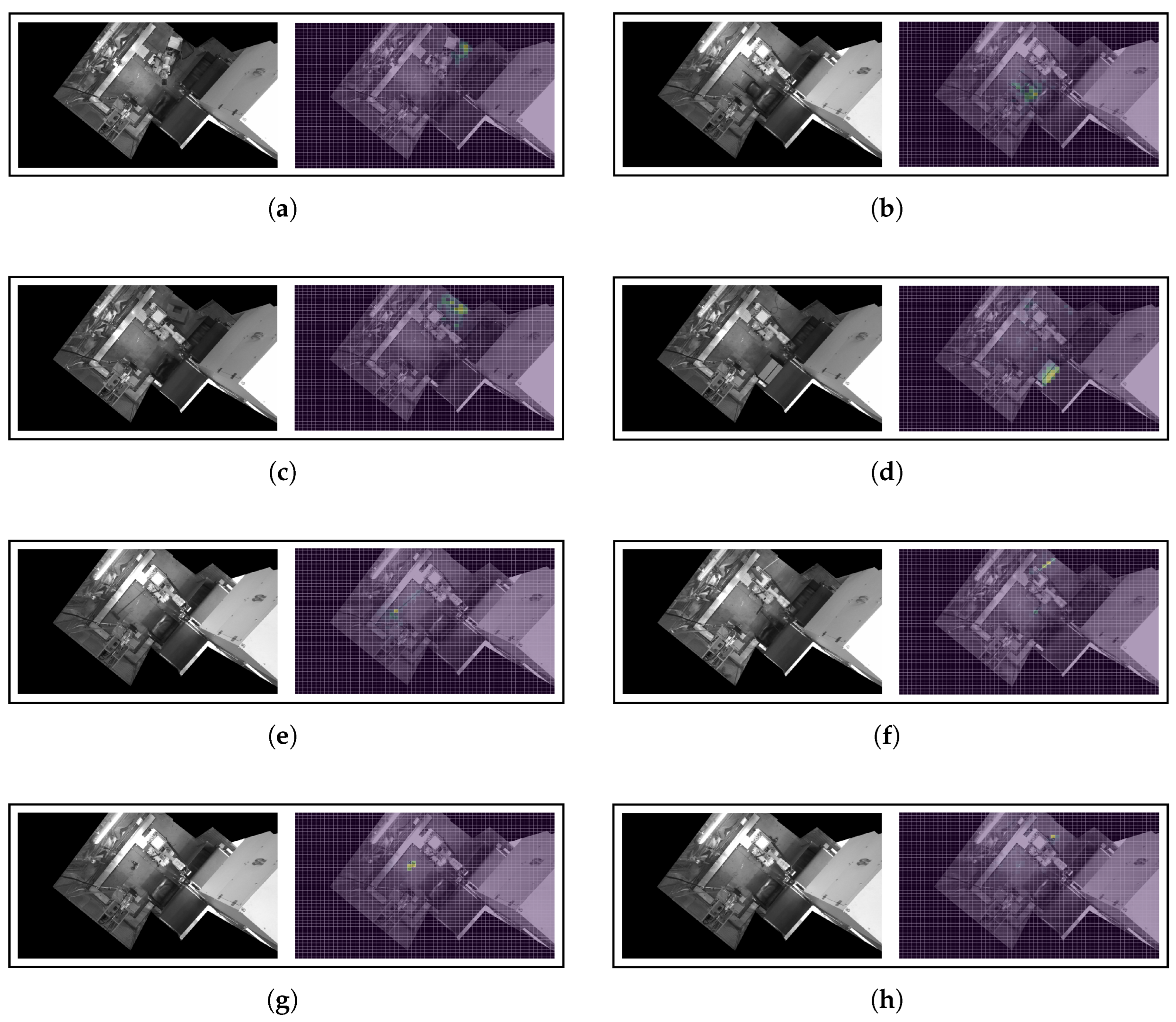

6.2. Saliency Maps

6.3. Discussion

7. Industrial Deployment

- Cycle-triggered-monitoring mode: the system will diagnose the safety of the industrial space only at the start of each production cycle.

- Continuous-monitoring mode: the safety check will be performed periodically every 50 milliseconds.

Limitations and Future Work

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEC | Architecture, engineering, and construction |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ANSI | American National Standards Institute |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BGMM | Bayesian Gaussian mixture model |

| CL | Contrastive learning |

| DL | Deep learning |

| EHSRs | Essential health and 46 safety requirements |

| EM | Expectation–maximization |

| FPS | Frame per second |

| ICS | Industrial control system |

| IPC | Industrial PC |

| OSHA | Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

| PaCMAP | Pairwise controlled manifold approximation projection |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PLC | Programmable logic controller |

| P–R | Precision–recall |

| t-SNE | t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding |

| XAI | Explainable artificial intelligence |

Appendix A. Overlapping Bell Curves

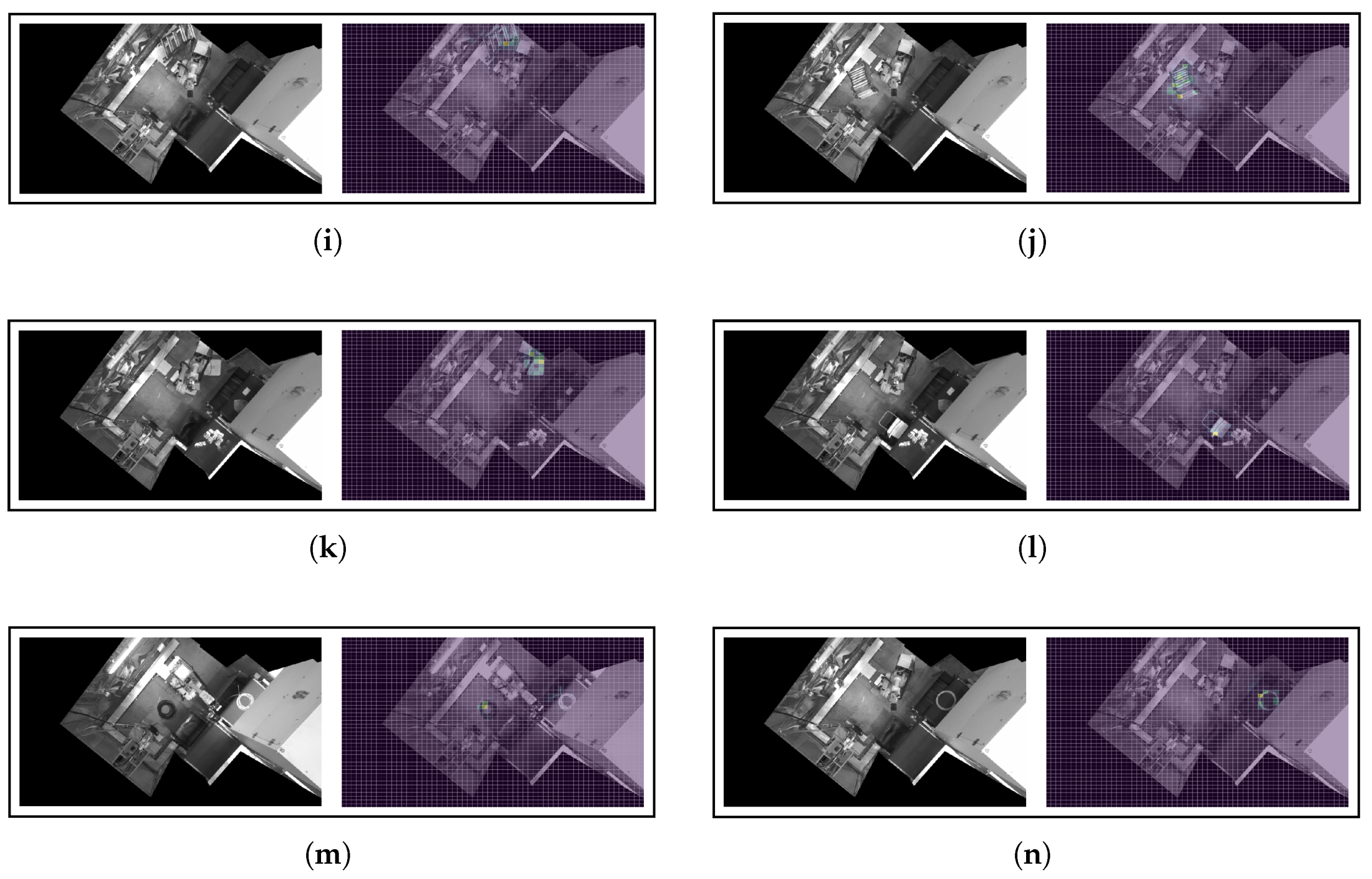

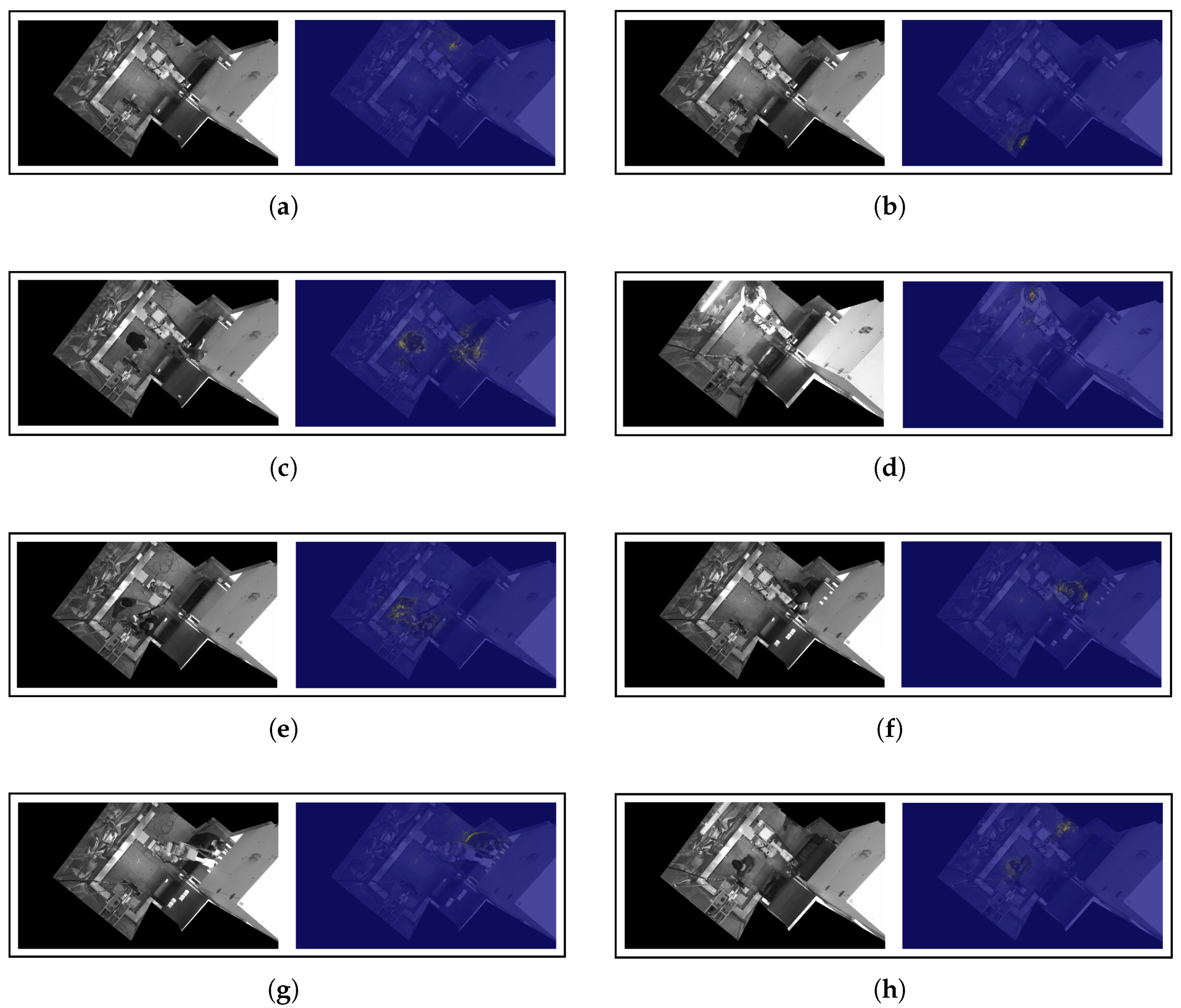

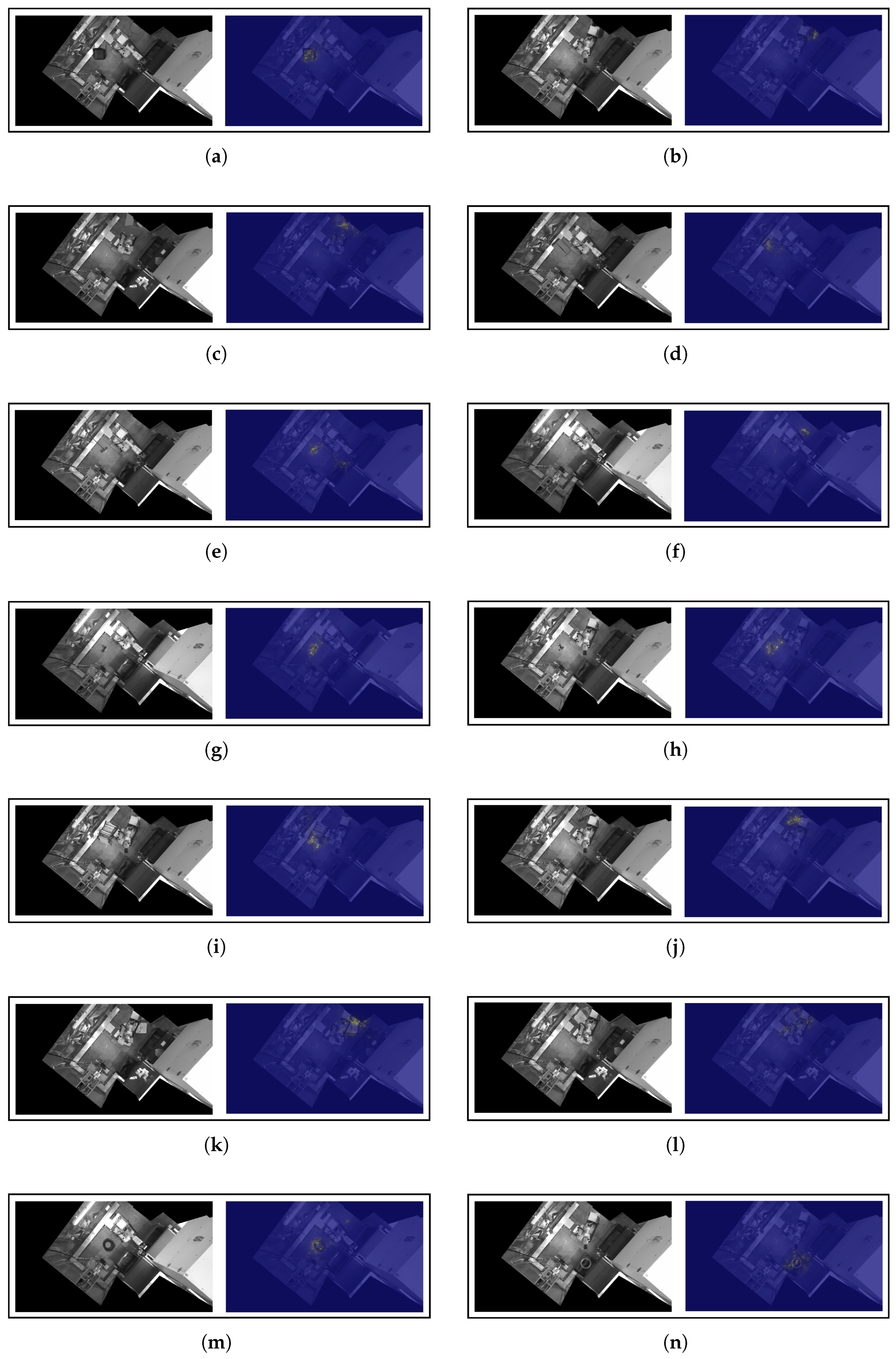

Appendix B. Interpretability Outputs

Appendix B.1. Input Feature Ablations

Appendix B.2. Saliency Outputs

References

- Bureau of Economic Analysis Number and Rate of Nonfatal Work Injuries in Detailed Private Industries. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/charts/injuries-and-illnesses/number-and-rate-of-nonfatal-work-injuries-by-industry-subsector.htm (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Eurostat Accidents at Work-Statistics by Economic Activity. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Accidents_at_work_-_statistics_by_economic_activity (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Eurostat Gross Value Added at Current Basic Prices, 2005 and 2024 (% Share of Total Gross Value Added). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Gross_value_added_at_current_basic_prices,_2005_and_2024_(%25_share_of_total_gross_value_added)_NA2025.png (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Bureau of Economic Analysis Value Added by Industry as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product. Available online: https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/?reqid=1603&step=2&Categories=GDPxInd&isURI=1&_gl=1*132dtfk*_ga*MTQyNTk0ODU2NS4xNzU2OTIwMzg5*_ga_J4698JNNFT*czE3NjQyNjg1NjIkbzIkZzEkdDE3NjQyNjg2MzUkajYwJGwwJGgw#eyJhcHBpZCI6MTYwMywic3RlcHMiOlsxLDIsNF0sImRhdGEiOltbImNhdGVnb3JpZXMiLCJHRFB4SW5kIl0sWyJUYWJsZV9MaXN0IiwiVFZBMTEwIl1dfQ== (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Lee, K.; Shin, J.; Lim, J.Y. Critical Hazard Factors in the Risk Assessments of Industrial Robots: Causal Analysis and Case Studies. Saf. Health Work 2021, 12, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 13849-1:2023; ISO Central Secretary. Safety of Machinery—Safety-Related Parts of Control Systems—Part 1: General Principles for Design. Standard, International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, CH, USA, 2023.

- IEC 62061:2021; IEC Central Secretary. Safety of Machinery—Functional Safety of Safety-Related Control Systems. Standard, International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, CH, USA, 2021.

- Fernández, J.; Valerieva, D.; Higuero, L.; Sahelices, B. 3DWS: Reliable segmentation on intelligent welding systems with 3D convolutions. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 36, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Cai, N.; Chen, K.; Xia, H.; Zhou, S.; Wang, H. GAN-based statistical modeling with adaptive schemes for surface defect inspection of IC metal packages. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 35, 1811–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardellicchio, A.; Nitti, M.; Patruno, C.; Mosca, N.; di Summa, M.; Stella, E.; Renò, V. Automatic quality control of aluminium parts welds based on 3D data and artificial intelligence. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 35, 1629–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.I.B.; Saraireh, L.; Rahman, A.; Al-Qarawi, S.; Mhran, A.; Al-Jalaoud, J.; Al-Mudaifer, D.; Al-Haidar, F.; AlKhulaifi, D.; Youldash, M.; et al. Personal Protective Equipment Detection: A Deep-Learning-Based Sustainable Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, T.S.; Srinivasan, S. Detection of safety wearable’s of the industry workers using deep neural network. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 80, 3064–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Demachi, K. A vision-based approach for ensuring proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in decommissioning of fukushima daiichi nuclear power station. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.P.; Wong, P.K.Y.; Luo, H.; Wang, M.; Leung, P.H. Vision-based monitoring of site safety compliance based on worker re-identification and personal protective equipment classification. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Zeng, X. Deep Learning-Based Workers Safety Helmet Wearing Detection on Construction Sites Using Multi-Scale Features. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisaezehra; Farooq, M.U.; Bhutto, M.A.; Kazi, A.K. Real-Time Safety Helmet Detection Using Yolov5 at Construction Sites. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2023, 36, 911–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barari, A.; Tsuzuki, M.; Cohen, Y.; Macchi, M. Editorial: Intelligent manufacturing systems towards industry 4.0 era. J. Intell. Manuf. 2021, 32, 1793–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alateeq, M.M.; Fathimathul, F.R.; Ali, M.A.S. Construction Site Hazards Identification Using Deep Learning and Computer Vision. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.; Selvakumari, S.; Praveena, S.; Rajiv, S. Deep Learning Enabled Smart Industrial Workers Precaution System Using Single Board Computer (SBC). Internet of Things for Industry 4.0; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; p. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S. Construction Site Safety Management: A Computer Vision and Deep Learning Approach. Sensors 2023, 23, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.C.; Ying, J.J.C. DeepSafety: A Deep Learning Framework for Unsafe Behaviors Detection of Steel Activity in Construction Projects. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Computer Symposium (ICS), Tainan, Taiwan, 17–19 December 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Dong, M.; Fang, T. Automatic detection of falling hazard from surveillance videos based on computer vision and building information modeling. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2022, 18, 1049–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahpour, N.; Moallem, M.; Narimani, M. Real-Time Safety Alerting System for Dynamic, Safety-Critical Environments. Automation 2025, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukicevic, A.M.; Petrovic, M.N.; Knezevic, N.M.; Jovanovic, K.M. Deep Learning-Based Recognition of Unsafe Acts in Manufacturing Industry. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 103406–103418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Hu, H.; Xu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, Z. Postural Ergonomic Assessment of Construction Workers Based on Human 3D Pose Estimation and Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, 18–21 December 2023; pp. 0168–0172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menanno, M.; Riccio, C.; Benedetto, V.; Gissi, F.; Savino, M.M.; Troiano, L. An Ergonomic Risk Assessment System Based on 3D Human Pose Estimation and Collaborative Robot. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, G.K.; Wang, X. Deep learning-based applications for safety management in the AEC industry: A review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.N.; Ku, Y.H.; Chou, Y.W.; Yu, H.S.; Lin, J.F. Safety Monitoring System of Stamping Presses Based on YOLOv8n Model. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 53660–53672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Kim, S.B.; Kim, H.W. Enhanced Anomaly Detection in Manufacturing Processes Through Hybrid Deep Learning Techniques. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 93368–93380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonci, A.; Fredianelli, L.; Kermenov, R.; Longarini, L.; Longhi, S.; Pompei, G.; Prist, M.; Verdini, C. DeepESN Neural Networks for Industrial Predictive Maintenance through Anomaly Detection from Production Energy Data. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.; Kim, S.; Jeon, G.; Kim, S.H.; Bae, K.; Kang, B.J. ReConPatch: Contrastive Patch Representation Learning for Industrial Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 2041–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Huang, J.; Di, D.; Su, A.; Fan, L. ToCoAD: Two-Stage Contrastive Learning for Industrial Anomaly Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 5012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.M.; Tufail, A.; Irshad, M.N. Survey of deep learning approaches for securing industrial control systems: A comparative analysis. Cyber Secur. Appl. 2025, 3, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, G.T.; Park, J.M.; Lee, K.S. Contrastive Learning-Based Anomaly Detection for Actual Corporate Environments. Sensors 2023, 23, 4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Agirre, I.; Perez-Cerrolaza, J.; Belategi, L.; Adell, A. AIFSM: Towards Functional Safety Management for Artificial Intelligence-based Critical Systems. In CARS@EDCC2024 Workshop-Critical Automotive Applications: Robustness & Safety; Hal Science: Leuven, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Etz, D.; Denzler, P.; Fruhwirth, T.; Kastner, W. Functional Safety Use Cases in the Context of Reconfigurable Manufacturing Systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 27th International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Stuttgart, Germany, 6–9 September 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Rudin, C.; Shaposhnik, Y. Understanding How Dimension Reduction Tools Work: An Empirical Approach to Deciphering t-SNE, UMAP, TriMap, and PaCMAP for Data Visualization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 22, 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Alemi, A.; Poole, B.; Fischer, I.; Dillon, J.; Saurous, R.A.; Murphy, K. Fixing a Broken ELBO. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; Dy, J., Krause, A., Eds.; Volume 80, pp. 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Khosla, P.; Teterwak, P.; Wang, C.; Sarna, A.; Tian, Y.; Isola, P.; Maschinot, A.; Liu, C.; Krishnan, D. Supervised Contrastive Learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Nice, France, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 18661–18673. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 13–18 July 2020; pp. 1597–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey on Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11976–11986. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Touvron, H.; Caron, M.; Bojanowski, P.; Douze, M.; Joulin, A.; Laptev, I.; Neverova, N.; Synnaeve, G.; Verbeek, J.; et al. Xcit: Cross-covariance image transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 20014–20027. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Sangineto, E.; Bi, W.; Sebe, N.; Lepri, B.; Nadai, M. Efficient training of visual transformers with small datasets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 23818–23830. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, R.; Bi, X.J. Transformers Meet Small Datasets. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 118454–118464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Taunk, K.; De, S.; Verma, S.; Swetapadma, A. A Brief Review of Nearest Neighbor Algorithm for Learning and Classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICCS), Madurai, India, 15–17 May 2019; pp. 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, M.; Calcagnì, A. Measuring Distribution Similarities Between Samples: A Distribution-Free Overlapping Index. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastore, M. Overlapping: A R package for Estimating Overlapping in Empirical Distributions. J. Open Source Softw. 2018, 3, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newburger, E.; Elmqvist, N. Comparing overlapping data distributions using visualization. Inf. Vis. 2023, 22, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. A survey on Bayesian inference for Gaussian mixture model. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.11753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Jordan, M.I. Variational inference for Dirichlet process mixtures. Bayesian Anal. 2006, 1, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Mienye, I.D.; Sun, Y. A Survey of Ensemble Learning: Concepts, Algorithms, Applications, and Prospects. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 99129–99149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Kora, R. A comprehensive review on ensemble deep learning: Opportunities and challenges. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 757–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, A.; Subhashini, R. A systematic review of Explainable Artificial Intelligence models and applications: Recent developments and future trends. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 7, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Abuhmed, T.; El-Sappagh, S.; Muhammad, K.; Alonso-Moral, J.M.; Confalonieri, R.; Guidotti, R.; Del Ser, J.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Herrera, F. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): What we know and what is left to attain Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence. Inf. Fusion 2023, 99, 101805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, M.; Khanal, A.; Estrada, R. Ai playground: Unreal engine-based data ablation tool for deep learning. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Visual Computing, San Diego, CA, USA, 5–7 October 2020; pp. 518–532. [Google Scholar]

- Meyes, R.; Lu, M.; de Puiseau, C.W.; Meisen, T. Ablation studies in artificial neural networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.08644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.; Yosinski, J.; Clune, J. Deep neural networks are easily fooled: High confidence predictions for unrecognizable images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 427–436. [Google Scholar]

- Merrick, L. Randomized ablation feature importance. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.00174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Deep inside convolutional networks: Visualising image classification models and saliency maps. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6034. [Google Scholar]

- Abhishek, K.; Kamath, D. Attribution-based XAI methods in computer vision: A review. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.14736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancona, M.; Ceolini, E.; Öztireli, C.; Gross, M. Gradient-Based Attribution Methods. In Explainable AI: Interpreting, Explaining and Visualizing Deep Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etz, D.; Frühwirth, T.; Kastner, W. Flexible Safety Systems for Smart Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Vienna, Austria, 8–11 September 2020; Volume 1, pp. 1123–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Nº of Images | Safety Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Ok | 2912 | ✓ |

| Ko (Person) | 3224 | ✗ |

| Black chair | 104 | ? |

| Box | 263 | ? |

| Brush | 180 | ? |

| Drill | 14 | ? |

| Stairs | 17 | ? |

| White chair | 85 | ? |

| Wire | 36 | ? |

| Dataset | Ok | Ko (Person) | Other Objects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Train | 2074 | 2296 | — |

| Validation | 484 | 766 | — |

| Supplementary train | 208 | — | — |

| Test | 146 | 162 | 699 |

| Test | ResNet-18 | DenseNet-161 | DenseNet-201 | EfficientNet-B0 | ConvNeXt-nano | XCiT-nano |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-18 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9983 | 0.9626 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9809 | 0.9928 |

| DenseNet-161 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9999 | 0.7192 | 0.9269 | 0.9094 | 1.0000 | 0.9824 | 0.9422 |

| DenseNet-201 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9999 | 0.9989 | 0.9322 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9732 | 0.9880 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9991 | 0.8805 | 0.3852 | 0.8955 | 0.9983 | 0.8243 | 0.8729 |

| ConvNeXt-nano | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9989 | 0.8584 | 0.6639 | 0.7703 | 1.0000 | 0.8539 | 0.8932 |

| XCiT-nano | 1.0000 | 0.9992 | 1.0000 | 0.6725 | 0.8856 | 0.8682 | 1.0000 | 0.9544 | 0.9225 |

| Model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-18 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9983 | 0.9626 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9809 | 0.9928 |

| DenseNet-201 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9999 | 0.9989 | 0.9322 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9732 | 0.9880 |

| Hybrid model | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9874 | 0.9984 |

| ResNet-18 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9983 | 0.9626 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9809 | 0.9928 |

| DenseNet-161 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9999 | 0.7192 | 0.9269 | 0.9094 | 1.0000 | 0.9824 | 0.9422 |

| Hybrid model | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9999 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9850 | 0.9981 |

| ResNet-18 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9983 | 0.9626 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9809 | 0.9928 |

| ConvNeXt-nano | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9989 | 0.8584 | 0.6639 | 0.7703 | 1.0000 | 0.8539 | 0.8932 |

| Hybrid model | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9999 | 0.9898 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9729 ✱ | 0.9953 |

| DenseNet-201 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9999 | 0.9989 | 0.9322 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9732 | 0.9880 |

| DenseNet-161 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9999 | 0.7192 | 0.9269 | 0.9094 | 1.0000 | 0.9824 | 0.9422 |

| Hybrid model | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9996 | 0.9449 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9766 | 0.9901 |

| XCiT-nano | 1.0000 | 0.9992 | 1.0000 | 0.6725 | 0.8856 | 0.8682 | 1.0000 | 0.9544 | 0.9225 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9991 | 0.8805 | 0.3852 | 0.8955 | 0.9983 | 0.8243 | 0.8729 |

| Hybrid model | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.8869 | 0.8882 | 0.9680 | 1.0000 | 0.9760 | 0.9649 |

| XCiT-nano | 1.0000 | 0.9992 | 1.0000 | 0.6725 | 0.8856 | 0.8682 | 1.0000 | 0.9544 | 0.9225 |

| ConvNeXt-nano | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9989 | 0.8584 | 0.6639 | 0.7703 | 1.0000 | 0.8539 | 0.8932 |

| Hybrid model | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.8352 ✱ | 0.9024 | 0.9427 | 1.0000 | 0.9703 | 0.9563 |

| ConvNeXt-nano | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9989 | 0.8584 | 0.6639 | 0.7703 | 1.0000 | 0.8539 | 0.8932 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9991 | 0.8805 | 0.3852 | 0.8955 | 0.9983 | 0.8243 | 0.8729 |

| Hybrid model | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9998 | 0.9253 | 0.6957 | 0.8993 | 1.0000 | 0.9032 | 0.9279 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Iglesias, J.; Buitrago, F.; Sahelices, B. Reliable Detection of Unsafe Scenarios in Industrial Lines Using Deep Contrastive Learning with Bayesian Modeling. Automation 2025, 6, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040084

Fernández-Iglesias J, Buitrago F, Sahelices B. Reliable Detection of Unsafe Scenarios in Industrial Lines Using Deep Contrastive Learning with Bayesian Modeling. Automation. 2025; 6(4):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040084

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Iglesias, Jesús, Fernando Buitrago, and Benjamín Sahelices. 2025. "Reliable Detection of Unsafe Scenarios in Industrial Lines Using Deep Contrastive Learning with Bayesian Modeling" Automation 6, no. 4: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040084

APA StyleFernández-Iglesias, J., Buitrago, F., & Sahelices, B. (2025). Reliable Detection of Unsafe Scenarios in Industrial Lines Using Deep Contrastive Learning with Bayesian Modeling. Automation, 6(4), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040084