Automatic Classification of Gait Patterns in Cerebral Palsy Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Cerebral Palsy

2.2. Fuzzy Systems

2.3. Ensemble Learning

2.4. Model Performance on Imbalanced Datasets

2.5. Approaches to Imbalanced Datasets

3. Zero-Order Autonomous Learning Multiple Model (ALMMo-0) Classifier

| Algorithm 1 ALMMo-0 training algorithm. |

|

4. Proposed Approach

4.1. ALMMo-0 (W)

| Algorithm 2 ALMMo-0-W training algorithm. |

|

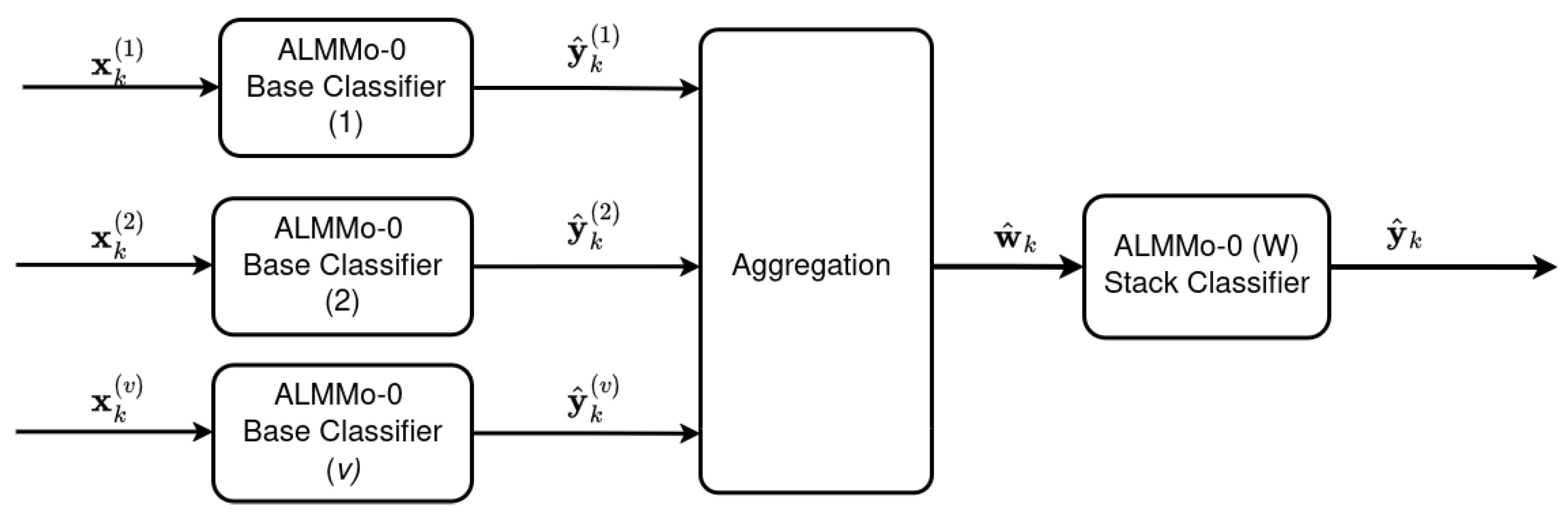

4.2. Ensemble Architecture

5. Results

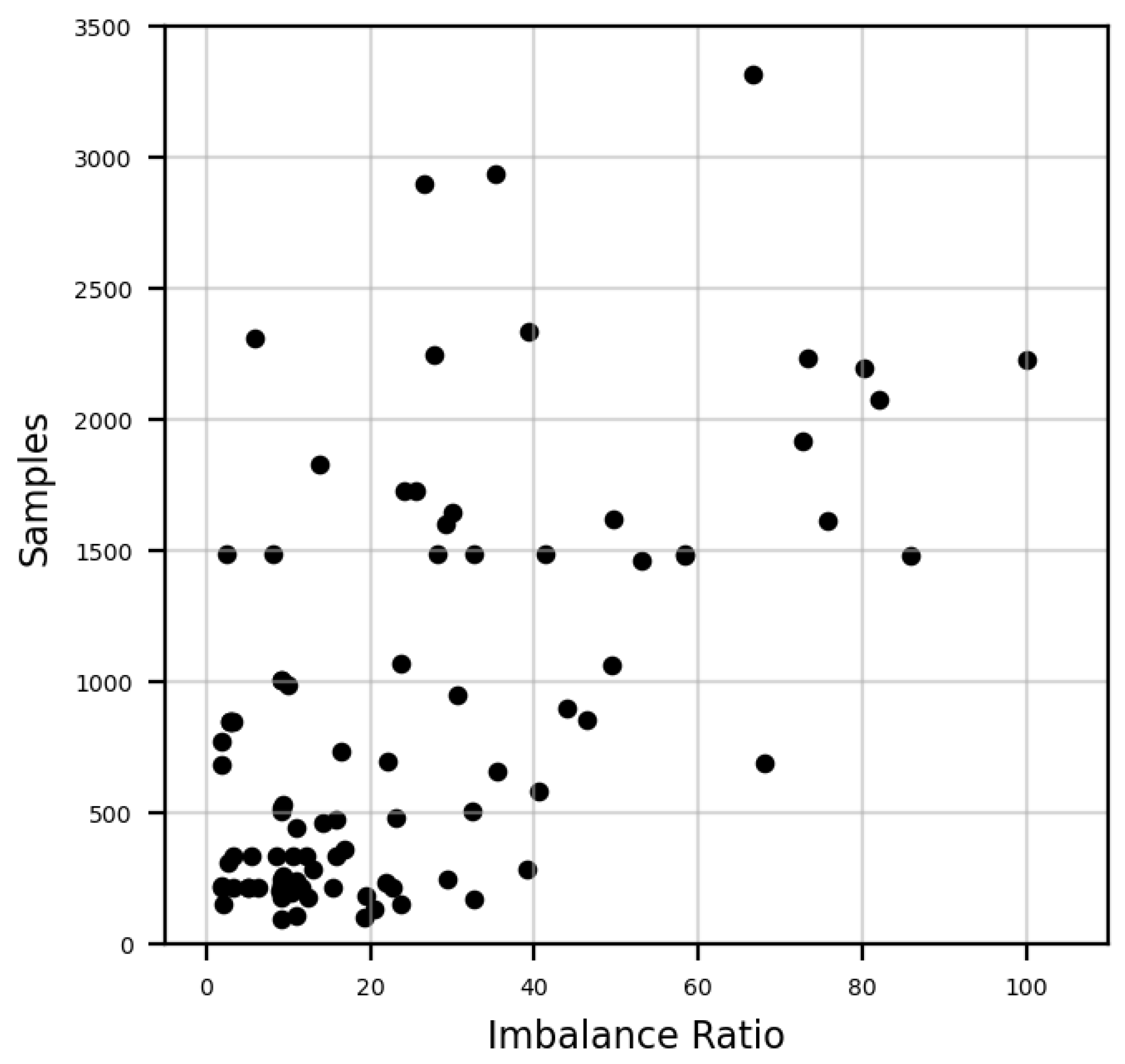

5.1. Benchmark Datasets

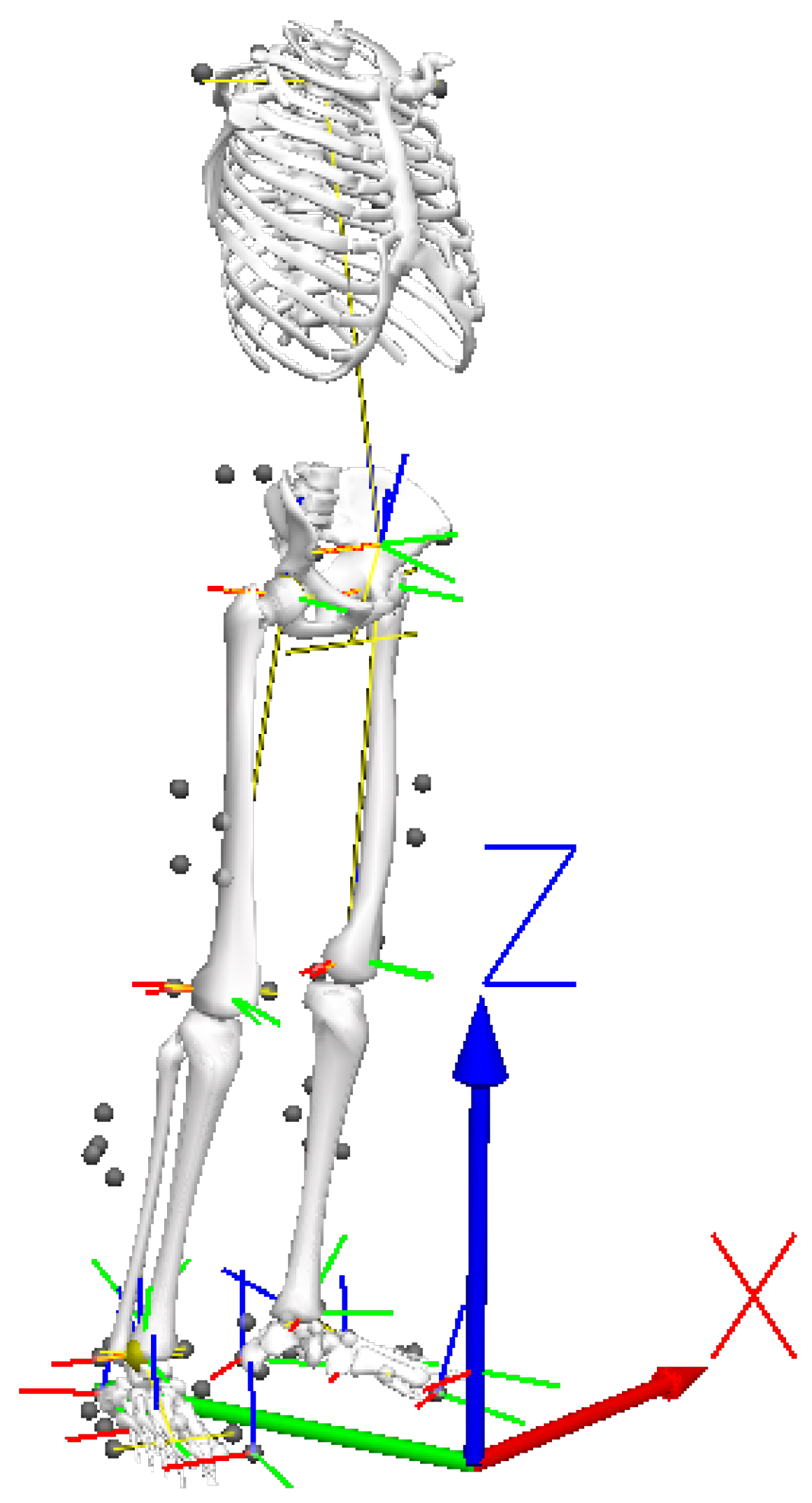

5.2. Spastic Diplegia Dataset

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lughofer, E.; Pratama, M. Evolving multi-user fuzzy classifier system with advanced explainability and interpretability aspects. Inf. Fusion 2022, 91, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilpin, L.H.; Bau, D.; Yuan, B.Z.; Bajwa, A.; Specter, M.; Kagal, L. Explaining Explanations: An Overview of Interpretability of Machine Learning. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouifak, H.; Idri, A. On the performance and interpretability of Mamdani and Takagi-Sugeno-Kang based neuro-fuzzy systems for medical diagnosis. Sci. Afr. 2023, 20, e01610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilaskar, S.; Ghatol, A.; Chatur, P. Medical decision support system for extremely imbalanced datasets. Inf. Sci. 2017, 384, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.M.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Survey on deep learning with class imbalance. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, V.; Fernández, A.; García, S.; Palade, V.; Herrera, F. An insight into classification with imbalanced data: Empirical results and current trends on using data intrinsic characteristics. Inf. Sci. 2013, 250, 113–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barella, V.H.; Garcia, L.P.; De Souto, M.C.; Lorena, A.C.; De Carvalho, A.C. Assessing the data complexity of imbalanced datasets. Inf. Sci. 2021, 553, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, E.; Angelov, P.; Gu, X. Autonomous Learning Multiple-Model zero-order classifier for heart sound classification. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 94, 106449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škrjanc, I.; Iglesias, J.A.; Sanchis, A.; Leite, D.; Lughofer, E.; Gomide, F. Evolving fuzzy and neuro-fuzzy approaches in clustering, regression, identification, and classification: A Survey. Inf. Sci. 2019, 490, 344–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelov, P.; Gu, X. Autonomous learning multi-model classifier of 0-Order (ALMMo-0). In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Evolving and Adaptive Intelligent Systems, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 31 May–2 June 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax, M.; Damiano, D.; Dan, B.; Jacobsson, B. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. Suppl. 2007, 109, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rodda, J.M.; Graham, H.K.; Carson, L.; Galea, M.P.; Wolfe, R. Sagittal gait patterns in spastic diplegia. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2004, 86, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodda, J.; Graham, H.K. Classification of gait patterns in spastic hemiplegia and spastic diplegia: A basis for a management algorithm. Eur. J. Neurol. 2001, 8, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terano, T.; Asai, K.; Sugeno, M. Applied Fuzzy Systems; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, J.M.C.; Kaymak, U. Fuzzy Decision Making in Modeling and Control; World Scientific Inc.: Singapore, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Angelov, P.; Zhou, X. Evolving Fuzzy-Rule-Based Classifiers from Data Streams. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2008, 16, 1462–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Angelov, P.P. Self-organising fuzzy logic classifier. Inf. Sci. 2018, 447, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelov, P.P.; Gu, X.; Principe, J.C. Autonomous Learning Multimodel Systems from Data Streams. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2018, 26, 2213–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Angelov, P.; Zhao, Z. Self-organizing fuzzy inference ensemble system for big streaming data classification. Knowl. Based Syst. 2021, 218, 106870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X. Multilayer Ensemble Evolving Fuzzy Inference System. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 29, 2425–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, R.; Salgado, C.M.; Curto, S.; Carvalho, J.P.; Vieira, S.M.; Finkelstein, S.N. Daily prediction of ICU readmissions using feature engineering and ensemble fuzzy modeling. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 79, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, C.M.; Vieira, S.M.; Mendonça, L.F.; Finkelstein, S.; Sousa, J.M. Ensemble fuzzy models in personalized medicine: Application to vasopressors administration. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2016, 49, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Purohit, A. A Survey on Methods for Solving Data Imbalance Problem for Classification. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 127, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejatian, S.; Parvin, H.; Faraji, E. Using sub-sampling and ensemble clustering techniques to improve performance of imbalanced classification. Neurocomputing 2018, 276, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, A. Survey of resampling techniques for improving classification performance in unbalanced datasets. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.06048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Peng, L.; Ma, K.; Zhao, C.; Ji, K. A signature-based assistant random oversampling method for malware detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 18th IEEE International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications/13th IEEE International Conference on Big Data Science and Engineering, TrustCom/BigDataSE 2019, Rotorua, New Zealand, 5–8 August 2019; pp. 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusa, J.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M.; DIttman, D.J.; Napolitano, A. Using Random Undersampling to Alleviate Class Imbalance on Tweet Sentiment Data. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 16th International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration, IRI 2015, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–15 August 2015; pp. 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; García, S.; Herrera, F.; Chawla, N.V. SMOTE for Learning from Imbalanced Data: Progress and Challenges, Marking the 15-year Anniversary. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2018, 61, 863–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Q.; Zhao, X.; Ma, Z. A Novel Method for Identification of Glutarylation Sites Combining Borderline-SMOTE With Tomek Links Technique in Imbalanced Data. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2022, 19, 2632–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lango, M.; Stefanowski, J. Multi-class and feature selection extensions of Roughly Balanced Bagging for imbalanced data. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2018, 50, 97–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Ge, Y.; Xiao, K.; Wang, X.; Quan, X. Feature selection for high-dimensional imbalanced data. Neurocomputing 2013, 105, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Li, Q.; Guo, W.; Ren, C.; Li, C.; Liu, R.; Zou, J. Self-adaptive cost weights-based support vector machine cost-sensitive ensemble for imbalanced data classification. Inf. Sci. 2019, 487, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lin, Y.; Min, F.; Liu, D. Cost-sensitive active learning through statistical methods. Inf. Sci. 2019, 501, 460–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, D.; Teles, J.; Raposo, M.R.; Veloso, A.P.; João, F. Test-Retest Reliability of a 6DoF Marker Set for Gait Analysis in Cerebral Palsy Children. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithm | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| ALMMo-0 | - | - |

| ALMMo-0 (W) | Maximum iterations | 100 |

| Optimization metric | Geometric Mean | |

| F1-Score | ||

| Matthews Correlation Coefficient | ||

| Decision Tree | Split quality criterion | Gini impurity |

| Split strategy | Best split | |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | K | 5 |

| Distance metric | Euclidean | |

| Support Vector Machine | Regularization parameter | 1.0 |

| Kernel type | RBF | |

| Kernel Coefficient | 2.0 |

| Metric | Definition |

|---|---|

| Recall | |

| Precision | |

| Specificity | |

| Balanced Accuracy | |

| Geometric Mean | |

| F1-Score | |

| Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

| Compared Against Algorithm on Metric | Algorithm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALMMo-0 | ALMMo-0 (W) | ||||

| Weight Optimization Metric | |||||

| Geometric Mean | F1-Score | Matthews Correlation Coefficient | |||

| ALMMo-0 | Balanced Accuracy | - | 62/378/60 +2.1 ± 11.1% (0.05) | 52/412/36 +1.7 ± 9.2% (0.00) | 53/403/44 +1.8 ± 9.7% (0.01) |

| Recall | - | 85/415/0 +8.8 ± 22.7% (0.00) | 62/438/0 +5.4 ± 17.8% (0.00) | 69/431/0 +6.4 ± 19.3% (0.00) | |

| Precision | - | 21/382/97 −3.3 ± 10.5% (1.00) | 25/412/63 −1.1 ± 6.0% (1.00) | 20/404/76 −1.6 ± 7.2% (1.00) | |

| Decision Tree | Balanced Accuracy | 187/161/152 +11.6 ± 32.4% (0.01) | 190/159/151 +12.6 ± 33.1% (0.00) | 191/160/149 +12.4 ± 33.2% (0.00) | 190/160/150 +12.5 ± 33.2% (0.00) |

| Recall | 173/228/99 +10.8 ± 45.6% (0.00) | 199/223/78 +17.6 ± 47.4% (0.00) | 187/228/85 +14.7 ± 47.2% (0.00) | 191/226/83 +15.7 ± 47.3% (0.00) | |

| Precision | 141/188/171 −2.9 ± 42.1% (0.85) | 131/185/184 −4.9 ± 41.2% (0.99) | 135/186/179 −3.9 ± 41.4% (0.95) | 133/186/181 −4.0 ± 41.4% (0.96) | |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | Balanced Accuracy | 179/176/145 +12.0 ± 29.5% (0.00) | 191/174/135 +13.0 ± 30.0% (0.00) | 192/174/134 +12.9 ± 29.9% (0.00) | 189/174/137 +12.9 ± 29.9% (0.00) |

| Recall | 203/239/58 +18.9 ± 39.1% (0.00) | 230/229/41 +25.2 ± 42.0% (0.00) | 225/231/44 +23.3 ± 40.8% (0.00) | 227/230/43 +23.9 ± 41.3% (0.00) | |

| Precision | 103/216/181 −8.6 ± 36.0% (1.00) | 105/210/185 −10.2 ± 36.3% (1.00) | 99/215/186 −9.5 ± 35.6% (1.00) | 101/212/187 −9.6 ± 35.6% (1.00) | |

| Support Vector Machine | Balanced Accuracy | 237/133/130 +22.8 ± 39.7% (0.00) | 245/133/122 +23.5 ± 39.5% (0.00) | 240/133/127 +23.6 ± 39.7% (0.00) | 245/133/122 +23.6 ± 39.8% (0.00) |

| Recall | 135/217/148 +7.3 ± 46.0% (0.10) | 149/222/129 +12.0 ± 46.8% (0.00) | 146/221/133 +10.2 ± 46.3% (0.01) | 147/220/133 +10.7 ± 46.6% (0.00) | |

| Precision | 260/160/80 +18.2 ± 44.4% (0.00) | 258/156/86 +16.7 ± 43.7% (0.00) | 259/158/83 +17.6 ± 43.9% (0.00) | 258/157/85 +17.5 ± 44.0% (0.00) | |

| Compared Against Algorithm on Metric | Algorithm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALMMo-0 | ALMMo-0 (W) | ||||

| Weight Optimization Metric | |||||

| Geometric Mean | F1-Score | Matthews Correlation | |||

| ALMMo-0 | Geometric Mean | - | 60/381/59 +2.5 ± 12.6% (0.01) | 50/412/38 +1.8 ± 9.7% (0.01) | 52/403/45 +2.0 ± 10.5% (0.01) |

| F1-Score | - | 45/380/75 −0.9 ± 11.1% (0.84) | 46/412/42 +0.5 ± 7.2% (0.03) | 47/405/48 +0.2 ± 7.9% (0.10) | |

| Matthews Correlation | - | 43/378/79 −2.0 ± 14.5% (0.95) | 43/385/72 −0.4 ± 9.2% (0.11) | 44/379/77 −0.7 ± 10.8% (0.29) | |

| Decision Tree | Geometric Mean | 193/167/140 +10.9 ± 40.9% (0.00) | 199/165/136 +12.6 ± 40.5% (0.00) | 196/166/138 +11.9 ± 41.5% (0.00) | 196/166/138 +12.1 ± 41.3% (0.00) |

| F1-Score | 162/168/170 −0.7 ± 39.5% (0.36) | 164/167/169 −0.4 ± 39.2% (0.30) | 164/167/169 −0.0 ± 39.6% (0.18) | 165/167/168 −0.0 ± 39.5% (0.19) | |

| Matthews Correlation | 175/160/165 −2.2 ± 41.5% (0.39) | 163/168/169 −2.4 ± 41.5% (0.37) | 164/169/167 −1.7 ± 41.4% (0.26) | 165/169/166 −1.8 ± 41.3% (0.28) | |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | Geometric Mean | 189/190/121 +16.8 ± 36.9% (0.00) | 204/185/111 +18.2 ± 37.3% (0.00) | 201/188/111 +17.9 ± 37.1% (0.00) | 202/187/111 +17.9 ± 37.1% (0.00) |

| F1-Score | 147/191/162 +0.5 ± 32.7% (0.56) | 159/185/156 +0.6 ± 33.5% (0.40) | 158/189/153 +1.2 ± 33.0% (0.28) | 158/188/154 +1.1 ± 33.0% (0.32) | |

| Matthews Correlation | 134/176/190 −2.7 ± 35.3% (0.99) | 129/193/178 −2.6 ± 35.5% (0.98) | 135/194/171 −1.9 ± 34.8% (0.97) | 132/193/175 −1.9 ± 34.6% (0.97) | |

| Support Vector Machine | Geometric Mean | 243/147/110 +25.8 ± 45.8% (0.00) | 253/145/102 +27.2 ± 44.7% (0.00) | 247/147/106 +26.8 ± 45.4% (0.00) | 250/146/104 +26.9 ± 45.4% (0.00) |

| F1-Score | 263/148/89 +18.4 ± 42.5% (0.00) | 267/146/87 +18.7 ± 41.8% (0.00) | 264/148/88 +19.1 ± 42.1% (0.00) | 264/147/89 +19.0 ± 42.2% (0.00) | |

| Matthews Correlation | 264/144/92 +16.0 ± 45.2% (0.00) | 253/152/95 +16.1 ± 44.5% (0.00) | 255/153/92 +16.6 ± 44.4% (0.00) | 257/152/91 +16.8 ± 44.1% (0.00) | |

| Metric | F-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Balanced Accuracy | 42.46 | 0.000 |

| Recall | 60.36 | 0.000 |

| Precision | 11.49 | 0.000 |

| Geometric Mean | 84.67 | 0.000 |

| F1-Score | 18.05 | 0.000 |

| Matthews Correlation | 23.91 | 0.000 |

| Group | Samples | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals | Legs | Gait Cycles | |

| Control | 25 (81%) | 50 (85%) | 183 (87%) |

| Patient | 6 (19%) | 9 (15%) | 27 (13%) |

| Split | Gait Cycles | Class Imbalance Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Patient | |||||

| Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | |

| 1 | 147 | 36 | 20 | 7 | 7.4 | 5.1 |

| 2 | 149 | 34 | 20 | 7 | 7.5 | 4.9 |

| 3 | 150 | 33 | 20 | 7 | 7.5 | 4.7 |

| 4 | 142 | 41 | 20 | 7 | 7.1 | 5.9 |

| 5 | 144 | 39 | 21 | 6 | 6.9 | 6.5 |

| Ensemble Algorithms | Metric | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Model | Stack

Model |

Balanced

Accuracy | Recall | Precision |

Geometric

Mean | F1-Score |

Matthews

Correlation |

| ALMMo-0 | ALMMo-0 | 0.943 ± 0.078 | 0.886 ± 0.156 | 1.000 ± 0.000 | 0.938 ± 0.085 | 0.933 ± 0.091 | 0.929 ± 0.097 |

| ALMMo-0 (W) (Geometric Mean) | 0.924 ± 0.073 | 1.000 ± 0.000 | 0.700 ± 0.283 | 0.919 ± 0.080 | 0.798 ± 0.195 | 0.767 ± 0.222 | |

| ALMMo-0 (W) (F1-Score) | 0.950 ± 0.112 | 0.900 ± 0.224 | 1.000 ± 0.000 | 0.941 ± 0.131 | 0.933 ± 0.149 | 0.935 ± 0.144 | |

| ALMMo-0 (W) (Matthews Correlation) | 0.967 ± 0.075 | 0.933 ± 0.149 | 1.000 ± 0.000 | 0.963 ± 0.082 | 0.960 ± 0.089 | 0.956 ± 0.099 | |

| Decision Tree | Decision Tree | 0.827 ± 0.140 | 0.738 ± 0.232 | 0.668 ± 0.270 | 0.815 ± 0.154 | 0.686 ± 0.234 | 0.630 ± 0.284 |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | K-Nearest Neighbors | 0.808 ± 0.127 | 0.767 ± 0.325 | 0.437 ± 0.095 | 0.781 ± 0.157 | 0.517 ± 0.106 | 0.488 ± 0.131 |

| Support Vector Machine | Support Vector Machine | 0.914 ± 0.093 | 0.829 ± 0.186 | 1.000 ± 0.000 | 0.905 ± 0.105 | 0.897 ± 0.117 | 0.892 ± 0.119 |

| Angle Feature | Metric | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint | Axis |

Balanced

Accuracy | Recall | Precision |

Geometric

Mean | F1-Score |

Matthews

Correlation |

| Ankle | X | 0.766 ± 0.152 | 0.667 ± 0.312 | 0.397 ± 0.108 | 0.741 ± 0.173 | 0.485 ± 0.148 | 0.425 ± 0.206 |

| Y | 0.961 ± 0.010 | 1.000 ± 0.000 | 0.386 ± 0.069 | 0.961 ± 0.010 | 0.554 ± 0.073 | 0.595 ± 0.059 | |

| Z | 0.754 ± 0.220 | 0.667 ± 0.312 | 0.600 ± 0.303 | 0.737 ± 0.225 | 0.598 ± 0.243 | 0.497 ± 0.387 | |

| Hip | X | 0.964 ± 0.030 | 0.960 ± 0.055 | 0.578 ± 0.067 | 0.963 ± 0.030 | 0.720 ± 0.062 | 0.730 ± 0.061 |

| Y | 0.884 ± 0.023 | 0.847 ± 0.065 | 0.350 ± 0.069 | 0.882 ± 0.024 | 0.491 ± 0.066 | 0.511 ± 0.055 | |

| Z | 0.870 ± 0.135 | 0.843 ± 0.205 | 0.656 ± 0.275 | 0.866 ± 0.140 | 0.724 ± 0.232 | 0.678 ± 0.278 | |

| Knee | X | 0.985 ± 0.022 | 0.980 ± 0.045 | 0.834 ± 0.099 | 0.984 ± 0.023 | 0.899 ± 0.061 | 0.898 ± 0.062 |

| Y | 0.751 ± 0.109 | 0.600 ± 0.224 | 0.520 ± 0.292 | 0.727 ± 0.121 | 0.523 ± 0.171 | 0.473 ± 0.214 | |

| Z | 0.923 ± 0.059 | 0.907 ± 0.130 | 0.447 ± 0.127 | 0.921 ± 0.062 | 0.587 ± 0.112 | 0.606 ± 0.100 | |

| Pelvis | X | 0.929 ± 0.065 | 0.893 ± 0.123 | 0.557 ± 0.128 | 0.927 ± 0.069 | 0.681 ± 0.122 | 0.686 ± 0.122 |

| Y | 0.661 ± 0.156 | 0.367 ± 0.217 | 0.800 ± 0.447 | 0.540 ± 0.307 | 0.500 ± 0.289 | 0.466 ± 0.390 | |

| Z | 0.689 ± 0.165 | 0.548 ± 0.334 | 0.287 ± 0.144 | 0.645 ± 0.214 | 0.373 ± 0.195 | 0.291 ± 0.244 | |

| Moment Feature | Metric | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint | Axis |

Balanced

Accuracy | Recall | Precision |

Geometric

Mean | F1-Score |

Matthews

Correlation |

| Hip | X | 0.907 ± 0.069 | 0.847 ± 0.139 | 0.541 ± 0.096 | 0.902 ± 0.075 | 0.656 ± 0.096 | 0.657 ± 0.101 |

| Y | 0.839 ± 0.073 | 0.727 ± 0.130 | 0.470 ± 0.191 | 0.829 ± 0.081 | 0.562 ± 0.172 | 0.551 ± 0.171 | |

| Z | 0.814 ± 0.086 | 0.667 ± 0.170 | 0.454 ± 0.087 | 0.795 ± 0.109 | 0.538 ± 0.116 | 0.523 ± 0.127 | |

| Knee | X | 0.919 ± 0.044 | 0.880 ± 0.084 | 0.502 ± 0.061 | 0.917 ± 0.045 | 0.637 ± 0.060 | 0.643 ± 0.063 |

| Y | 0.911 ± 0.044 | 0.927 ± 0.083 | 0.296 ± 0.074 | 0.910 ± 0.044 | 0.445 ± 0.082 | 0.488 ± 0.074 | |

| Z | 0.963 ± 0.004 | 1.000 ± 0.000 | 0.388 ± 0.047 | 0.962 ± 0.004 | 0.557 ± 0.047 | 0.598 ± 0.036 | |

| Pelvis | X | 0.966 ± 0.026 | 0.940 ± 0.055 | 0.850 ± 0.074 | 0.965 ± 0.027 | 0.891 ± 0.048 | 0.887 ± 0.049 |

| Y | 0.865 ± 0.051 | 0.795 ± 0.075 | 0.733 ± 0.208 | 0.861 ± 0.053 | 0.749 ± 0.116 | 0.706 ± 0.144 | |

| Z | 0.852 ± 0.164 | 0.767 ± 0.325 | 0.633 ± 0.217 | 0.830 ± 0.196 | 0.673 ± 0.239 | 0.643 ± 0.271 | |

| Removed Base Model | Metrics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Joint | Axis | Balanced Accuracy | Recall | Precision | Geometric Mean | F1-Score | Matthews Coefficient |

| Angle | Ankle | X | 0.907 ± 0.096 | 0.847 ± 0.150 | 0.772 ± 0.032 | 0.897 ± 0.054 | 0.775 ± 0.124 | 0.768 ± 0.093 |

| Y | 0.902 ± 0.072 | 0.839 ± 0.032 | 0.772 ± 0.089 | 0.892 ± 0.042 | 0.774 ± 0.041 | 0.763 ± 0.032 | ||

| Z | 0.907 ± 0.065 | 0.847 ± 0.117 | 0.767 ± 0.062 | 0.897 ± 0.068 | 0.773 ± 0.022 | 0.766 ± 0.098 | ||

| Hip | X | 0.902 ± 0.131 | 0.840 ± 0.021 | 0.768 ± 0.053 | 0.892 ± 0.065 | 0.770 ± 0.143 | 0.760 ± 0.060 | |

| Y | 0.904 ± 0.107 | 0.843 ± 0.085 | 0.773 ± 0.061 | 0.894 ± 0.150 | 0.775 ± 0.081 | 0.766 ± 0.083 | ||

| Z | 0.904 ± 0.039 | 0.843 ± 0.132 | 0.766 ± 0.105 | 0.894 ± 0.080 | 0.769 ± 0.022 | 0.761 ± 0.053 | ||

| Knee | X | 0.901 ± 0.096 | 0.839 ± 0.064 | 0.761 ± 0.079 | 0.891 ± 0.037 | 0.765 ± 0.109 | 0.756 ± 0.031 | |

| Y | 0.907 ± 0.109 | 0.849 ± 0.132 | 0.769 ± 0.112 | 0.897 ± 0.086 | 0.775 ± 0.107 | 0.766 ± 0.102 | ||

| Z | 0.903 ± 0.063 | 0.841 ± 0.114 | 0.771 ± 0.065 | 0.893 ± 0.075 | 0.773 ± 0.046 | 0.763 ± 0.140 | ||

| Pelvis | X | 0.903 ± 0.102 | 0.841 ± 0.123 | 0.768 ± 0.086 | 0.892 ± 0.041 | 0.771 ± 0.045 | 0.761 ± 0.137 | |

| Y | 0.909 ± 0.126 | 0.855 ± 0.130 | 0.762 ± 0.101 | 0.902 ± 0.041 | 0.775 ± 0.062 | 0.767 ± 0.146 | ||

| Z | 0.909 ± 0.040 | 0.850 ± 0.116 | 0.775 ± 0.041 | 0.899 ± 0.107 | 0.778 ± 0.028 | 0.771 ± 0.138 | ||

| Moment | Hip | X | 0.903 ± 0.112 | 0.843 ± 0.100 | 0.768 ± 0.054 | 0.893 ± 0.057 | 0.771 ± 0.100 | 0.762 ± 0.081 |

| Y | 0.905 ± 0.078 | 0.846 ± 0.120 | 0.770 ± 0.089 | 0.895 ± 0.087 | 0.774 ± 0.092 | 0.765 ± 0.093 | ||

| Z | 0.905 ± 0.044 | 0.847 ± 0.117 | 0.771 ± 0.054 | 0.896 ± 0.059 | 0.774 ± 0.100 | 0.765 ± 0.026 | ||

| Knee | X | 0.903 ± 0.148 | 0.842 ± 0.110 | 0.769 ± 0.054 | 0.893 ± 0.129 | 0.772 ± 0.062 | 0.762 ± 0.021 | |

| Y | 0.903 ± 0.069 | 0.841 ± 0.110 | 0.775 ± 0.141 | 0.893 ± 0.038 | 0.776 ± 0.023 | 0.766 ± 0.069 | ||

| Z | 0.902 ± 0.103 | 0.839 ± 0.120 | 0.772 ± 0.136 | 0.892 ± 0.090 | 0.774 ± 0.058 | 0.763 ± 0.124 | ||

| Pelvis | X | 0.902 ± 0.064 | 0.840 ± 0.050 | 0.761 ± 0.117 | 0.891 ± 0.054 | 0.765 ± 0.117 | 0.756 ± 0.067 | |

| Y | 0.904 ± 0.028 | 0.844 ± 0.075 | 0.764 ± 0.061 | 0.894 ± 0.024 | 0.769 ± 0.094 | 0.761 ± 0.041 | ||

| Z | 0.905 ± 0.075 | 0.845 ± 0.106 | 0.766 ± 0.106 | 0.895 ± 0.031 | 0.771 ± 0.075 | 0.762 ± 0.100 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ventura, R.B.; Sousa, J.M.C.; João, F.; Veloso, A.P.; Vieira, S.M. Automatic Classification of Gait Patterns in Cerebral Palsy Patients. Automation 2025, 6, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040071

Ventura RB, Sousa JMC, João F, Veloso AP, Vieira SM. Automatic Classification of Gait Patterns in Cerebral Palsy Patients. Automation. 2025; 6(4):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040071

Chicago/Turabian StyleVentura, Rodrigo B., João M. C. Sousa, Filipa João, António P. Veloso, and Susana M. Vieira. 2025. "Automatic Classification of Gait Patterns in Cerebral Palsy Patients" Automation 6, no. 4: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040071

APA StyleVentura, R. B., Sousa, J. M. C., João, F., Veloso, A. P., & Vieira, S. M. (2025). Automatic Classification of Gait Patterns in Cerebral Palsy Patients. Automation, 6(4), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/automation6040071