Abstract

This work presents a nonlinear aerodynamic model that describes the dynamics of a coaxial-rotor MAV. We have designed seven control laws based on linear and nonlinear controllers for path-following with a coaxial-rotor MAV in the presence of unknown disturbances, such as wind gusts. The linear controllers include Proportional–Derivative (PD) and Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID). The nonlinear techniques encompass nested saturation, sliding mode control, second-order sliding mode, high-order sliding mode, and adaptive backstepping. The results are shown after multiple computer simulations.

1. Introduction

The coaxial-rotor MAV (Mini Aerial Vehicle) is an unmanned aerial vehicle that has gained significant acceptance in the research area due to the compact structure of its components (fuselage, ailerons, motors, etc.). Another advantage is the wide variety of applications for these unmanned aerial systems. By the side of the research area with the coaxial-rotor MAV, the focus is on design control laws, trajectory following, aerodynamic structure research, materials analysis, and other related areas. The former is necessary to realize applications in the real world, such as surveillance, target acquisition, and area reconnaissance [1,2].

On the other hand, there are some disadvantages in the use of coaxial-rotor MAVs; some of them are that the design of the electronic systems should be small, and satisfy every necessity to achieve a stable flight. Another disadvantage is the aerodynamic structure design; for example, the distance between the top motor and the bottom motor must be sufficient but not too long to avoid inter-rotor wash interference, thereby obtaining a fixed yaw angle and preventing rotation in the z-axis during hover flight.

Finally, these coaxial-rotor MAVs are affected by wind gusts just like other UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles). Additionally, there are many areas of research related to coaxial-rotor systems.

Research in the scientific literature includes work on coaxial-rotor UAVs that aim to overcome some of the earlier mentioned disadvantages. For instance, in [3], fuzzy logic theory combined with sliding mode methodology is used to stabilize the longitudinal attitude of a small coaxial-rotor UAV. The control algorithm is designed to decouple the mathematical model of the coaxial-rotor UAV. This controller design helps to suppress modeling errors and external interference. The results in [3] are based on computer simulations. In [4], they combined the sliding mode control and PID control algorithm to stabilize the attitude of coaxial-rotor aircraft; the use of the two control laws combined is to achieve a steady flight and to maintain the hover position. The mathematical model of the coaxial-rotor craft in [4] considers the blade element theory to calculate the brandishing motion of the blades; the results of sliding mode with PID control in [4] are presented in experiments. Other studies focus on researching the aerodynamics of the coaxial-rotor and the external forces acting on the coaxial-rotor UAV [5], and even propose a better aerodynamic structure to carry generic payloads for various civil and agricultural applications; the results are presented numerically by computer [5]. A combinatorial control method based on sliding mode, coupled with a PID control, is proposed in [6]. The dynamical model is divided into two subsystems: a fully actuated subsystem and an underactuated subsystem. The control objective is to control the position and attitude tracking of a coaxial-rotor aircraft; the results are presented in numerical simulations and experiments. In [7], an dynamic observer is presented to deal with the uncertainties and disturbances and design a control law to stabilize a ducted coaxial-rotor UAV.

In [8], a coaxial-rotor is presented that is designed to be small, like a package, and to launch with other systems; they even developed a complete nonlinear aerodynamic model for the coaxial-rotor UAV, but once it was simplified, the objective in [8] was the application of a discrete Kalman filter to estimate the aerodynamic coefficients. Ref. [9] developed a compact coaxial-rotor to be launched with other propulsion systems, and the coaxial-rotor system even included a rotary-wing mechanism to achieve the rotations in roll and pitch angles, the control strategy used a cascade feedback controller, and for the first time it was tested in a wind tunnel and later tested at arbitrarily large attitude angles to demonstrate the control robustness.

In [10], a coaxial drone is presented, adding two servo motors to the aerodynamic structure to control the roll and pitch angles. A nonlinear dynamic model has been developed for the six degrees of freedom of the coaxial drone. A nonlinear control allocation approach is proposed, and its results are presented in numerical simulations and validated through real-world experiments.

To achieve the control objective of trajectory tracking despite the sensor noise, uncertainty in the model parameters, and external perturbations, in [11], a nonlinear robust backstepping sliding mode controller is proposed to control the attitude and the position of a coaxial-rotor aircraft; the results are presented in numerical and flight experiments. On the other hand, in [12], a control algorithm is proposed to stabilize the position and attitude of a coaxial-rotor drone. However, without knowing the mathematical model of its dynamics, the control approach in [12] employs an optimal model-free fuzzy controller and estimates the unknown dynamics. The results are shown in numerical simulations.

In this work, a dynamic mathematical model is developed that describes the coaxial-rotor MAV. This dynamic model includes the external disturbances by wind gusts, but in the controllers design, such disturbances are not considered to analyze the control responses in the path-following subject to unknown wind gusts, and we carry out a comparison between linear and nonlinear controllers. Then, the control laws that do not feel the disturbances in this work are the linear controllers, Proportional–Derivative (PD) and Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID), and the nonlinear controllers based on nested saturation, with the sliding modes methodologies based on first, second, and high-order.

It should be noted that we are proposing an adaptive backstepping control to handle these unknown disturbances and improve path-following with the coaxial-rotor MAV. This is the only controller in this work that accounts for unknown disturbances by designing an adaptation law based on the Euler angles and angular rates for the roll and pitch angles, before aiming to eliminate or reduce the effects of wind gusts.

This work is organized as follows: Section 2 shows the mathematical aerodynamic model to define the coaxial-rotor MAV; Section 3 presents the linear and nonlinear controllers design. Section 4 shows the simulation results obtained after several tests. Finally, Section 5 presents the discussion and the future work.

2. Coaxial-Rotor MAV Mathematical Model

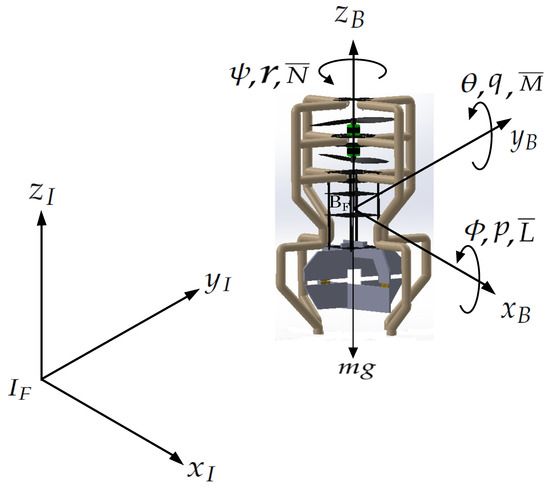

In this section, the mathematical model that describes the coaxial-rotor MAV dynamics based on the Newton–Euler formulation [13,14,15,16,17,18] is presented. The Earth’s curvature is not considered due to the coaxial-rotor MAV flying short distances. To obtain the mathematical model, two coordinate frames are considered— and (see Figure 1)—with knowledge as the inertial fixed frame and the body frame, respectively. The body frame is fixed and attached to the center of gravity of the coaxial-rotor MAV [19,20]. The general coordinates for the coaxial-rotor MAV are defined as . The mathematical model of the coaxial-rotor MAV is given by:

with the translation coordinates relative to the inertial frame ; is the gravitational force. The translational velocity is defined by in with respect to . The mass of the coaxial-rotor MAV is represented by m. The forces working in the coaxial-rotor MAV are given by . The Euler angles are defined with , and is the angular velocity in (see Figure 1). The torques working in the coaxial-rotor MAV are [21,22]. The inertial moments matrix is given by . The matrix is defined as [23]

Figure 1.

Coordinate systems on the coaxial-rotor MAV.

To obtain the orientation of the coaxial-rotor MAV, it is necessary to define a rotation matrix as :

Then, the Newton–Euler equations in a stable flight (hover flight) for a coaxial-rotor MAV are given by:

with , , , , , .

where are the inertial moments defined in the matrix . The actuator moments are given by , which are the control inputs to generate the roll, pitch, and yaw angles, respectively. The angular velocities of the motors are defined with and , and the inertia moment of the propellers are given by and . Finally, the aerodynamic moments are in roll angle, in pitch angle, and for yaw angle (see Figure 1).

Remark 1.

We designed a 3D model in SolidWorks 2026 to calculate the inertial constant values . The SolidWorks model is shown in Figure 1.

3. Linear and Nonlinear Controllers Design

To follow the desired trajectory with the coaxial-rotor MAV, in this work, the control laws are designed only for the pitch and roll angles; it is considered that the yaw angle is zero (the two brushless motors in the coaxial-rotor MAV operate at the same speed). Then, to know which controller presents the better performance in the presence of unknown wind gust perturbations, let us decouple Equations (8) and (9) to obtain pure roll and pitch angles, but considering the unknown wind gust perturbations in the mathematical model. Thus, the equations to define a pure roll angle with perturbations are defined by:

where , is the air density, the velocity in hover flight is defined as V, the aileron area is defined with S, b is the aileron span, and defined the aerodynamic coefficient in roll angle. We have added to the aerodynamic model some unknown wind gust perturbations , and is applied to compensate the units of measurement. The angular limits for the roll angle are .

The same procedure is used to define the equations for a pure pitch angle with perturbations.

where , is the average aileron length, and is the aerodynamic coefficient in pitch angle. The angluar limits for the pitch angle are .

The desired trajectory to follow by the coaxial-rotor MAV is defined as:

where and are the desired position in the x-axis and the y-axis, respectively. is a positive constant value to define the circumference amplitude of the desired trajectory, t is the time, and w defines the frequency. are the desired roll and pitch angle, respectively.

To regulate the altitude of the coaxial-rotor MAV, a PID controller is defined by:

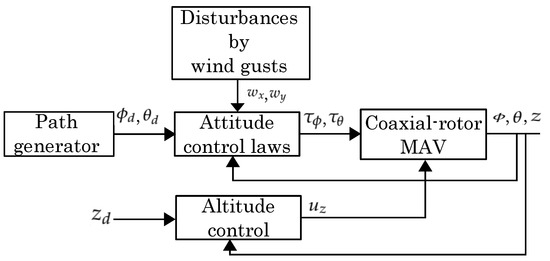

with , z is the actual altitude obtained from Equation (7), and is the desired altitude, m is the total mass of the coaxial-rotor MAV, g is the gravitational constant. The control scheme is presented in the Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Control scheme for attitude and altitude.

Remark 2.

It should be mentioned that the unknown perturbation by wind gusts ( and ) is not considered in the control laws design to compare the performance and robustness of the controllers in the presence of unknown perturbations. Except in the adaptive backstepping controller, a wind gust estimation is proposed to eliminate or reduce the unknown perturbation defined in (14)–(17).

3.1. Roll Angle Controllers Design

Thus, to design the linear controllers Proportional–Derivative (PD) and Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) for the roll angle, let us define an error , with as the desire roll angle, and defines the actual roll angle in the coaxial-rotor MAV. The PD control law for roll angle is given by [24,25]:

where . The PID controller in pitch and roll angles for the coaxial-rotor MAV is defined as:

with . To design the nested saturation control in the roll angle, it is necessary to perform a linear transformation to transform the system (14) and (15) [26]:

Then,

with , and . Let us define a saturation function with a limit a:

where a is a constant positive value; then, for the system (14) and (15) with the linear transformation (25) and the saturation function (26), the controller by nested saturation for roll angle to achieve global asymptotic stability is defined as:

The first-order sliding mode control to stabilize the roll angle is defined from a sliding manifold , and deriving the sliding manifold we have . Then, to stabilize the roll angle defined with the system (14) and (15) using the first-order sliding mode control methodology [27,28], we use:

where are the controller gains, and the sign function is defined as:

For the design of the second-order sliding mode, a first-order robust differentiator is necessary, because a real-time derivative is sensitive to noise at the time of performing the derivative action. The robust real-time differentiator [29] is given by

with and as real-time estimates of and , respectively. and are constant values to adjust the estimations. Then, to stabilize the roll angle with the second-order sliding modes [30], the controller obtained is:

where are positive gains to adjust the second-order sliding mode controller. To design the high-order sliding mode, it is necessary to have a second-order robust differentiator [31], and it is given by:

where , , and are real-time estimations of , , and . The constant values to adjust the estimations are defined by . Finally, the high-order sliding mode controller to stabilize the roll angle in the coaxial-rotor MAV is defined by:

with as positive constant values. For the adaptive backstepping control in roll angle [32,33,34], we consider the complete system (14) and (15), that is, we consider the unknown perturbation () to design the adaptation law, and we estimate to reduce or eliminate the external perturbations in the coaxial-rotor MAV. Then, the error in roll angle is defined as , and to begin with the adaptive control design, a Lyapunov candidate function is defined as:

Deriving (36):

The new error is , where . Then, the derivative of (36) is , due to the second term of the being not negative definite. To continue with the design of the adaptive controller, we have to define a new Lyapunov candidate function given by:

where are the adaptation gains, which are definite positive constants. Then, deriving (39):

Deriving the error :

Considering (40)–(42), the adaptive control law is given by:

Thus,

with . The adaptation equation for the perturbations by wind gusts is given by:

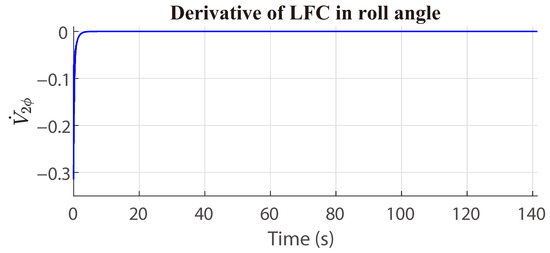

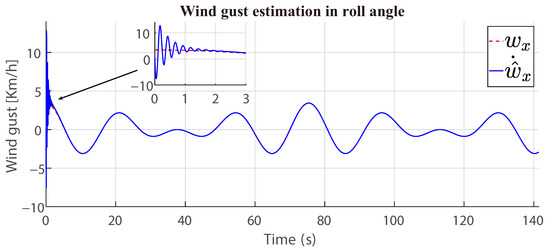

The Equation (44) is negative definite (see Figure 3). It is possible to achieve definite global stability with the adaptive control law (43) for the system (14) and (15), which defines the roll angle in the coaxial-rotor MAV. Finally, the adaptation gain is defined by , and it bounded; Figure 4 presents the convergence of the wind gust estimation ().

Figure 3.

Response of in roll angle.

Figure 4.

Convergence of the wing gust estimation .

3.2. Pitch Angle Controllers Design

To control the pitch angle, the same methodologies presented above are used, but applied to the system (16) and (17). Thus, the pitch error for pitch is given by , with as the desired pitch angle, and defines the actual pitch angle. Thus, the linear controller PD and PID are given by:

where are positive definite gains. The nested saturation control for pitch angle is developed with the methodology presented in the Equations (23)–(26). Thus, the nested saturation control to stabilize the pitch angle is given by:

To achieve the desired pitch angle with the first-order sliding mode control (SMC), a sliding manifold is defined as . Then, we follow the methodology used for roll angle and SMC. The first-order sliding mode for pitch angle is defined as:

where are positive values to tune in the controller. To design the second-order sliding mode, the same structure of the robust differentiator (29) and (30) is used to obtain and , respectively. Thus, the second-order sliding mode control applied to the pitch angle is given by:

with the controller gains as . Finally, to design the high order sliding mode controller to stabilize the pitch angle in the coaxial-rotor MAV, we use the same robust differentiator defined in (32)–(34) to obtain , , and , respectively:

where are positive constant. To design the adaptive backstepping law in pitch angle, it is necessary to follow the methodology presented from (36) to (45). Let us define the adaptive control law in pitch angle as:

Then, the final derivative of the Lyapunov candidate function in pitch angle is:

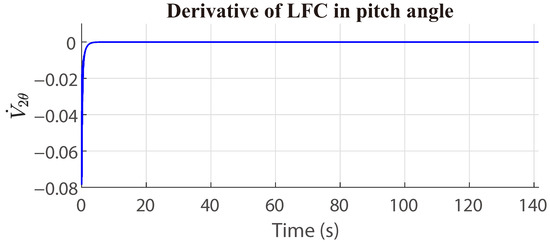

where are positive definite gains to tune the adaptive controller. The response of is presented in the Figure 5. The adaptation equation for the perturbations by wing gusts is given by:

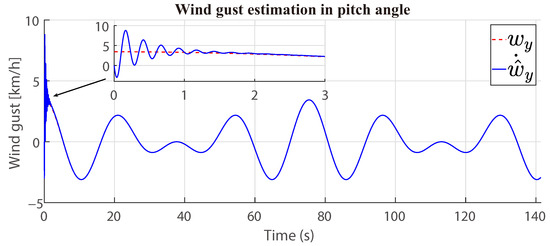

with as the adaptation gain for the pitch angle, and is bounded. The convergence of is presented in the Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Response of in pitch angle.

Figure 6.

Convergence of the wing gust estimation .

4. Simulation Results

To do the comparison between the linear and nonlinear control laws, we have used the to know the error of every controller applied to the coaxial-rotor MAV. The for the error is defined as:

The same is applied to calculate the control effort of each control law, and it is defined as:

represents the roll and pitch angles in the coaxial-rotor MAV, respectively.

4.1. Roll Angle Response

In Figure 7, the roll angle response is presented with the different linear and nonlinear controllers. We can observe oscillations resulting from the external perturbation (wind gusts). The PD, PID, and nested saturation controllers have presented more oscillations. Still, the perturbations in these control laws are oscillating on the desired roll angle to achieve the desired trajectory with the coaxial-rotor MAV. On the other hand, nonlinear controllers based on sliding mode methodologies and adaptive backstepping have shown better performance than PD, PID, and the nested saturation control when disturbances are present.

Figure 7.

Response in roll angle (with disturbances).

Furthermore, it is appreciated that the sliding mode methodologies achieve the desired roll angle, but the second-order sliding mode (2SM) and high-order sliding mode (HOSM) achieve the desired roll angle with an overdamped signal form. On the other hand, we can see that the first-order sliding mode (SM) and the adaptive backstepping presented a critically damped signal form to achieve the desired roll angle.

The controller that presented a small error in roll angle is the adaptive backstepping, and the significant error given with the second-order sliding mode control (2SM); see Table 1.

Table 1.

error and control effort in roll angle.

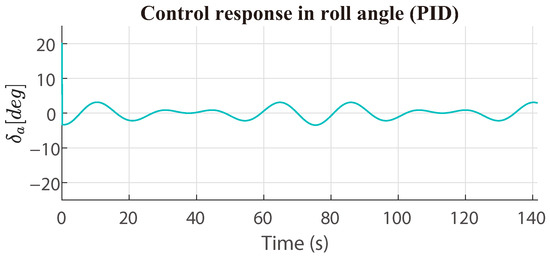

The PD and PID controllers applied a smaller control effort in comparison with the other control techniques in roll angle. Still, the adaptive backstepping is close to the control effort values presented with the PD and PID controllers; see Table 1. The Figure 8 and Figure 9 present the PD and PID control signals in the presence of the disturbances, respectively. The control signal response for the nested saturation control is presented in Figure 10.

Figure 8.

PD control response in roll angle (with disturbances).

Figure 9.

PID control response in roll angle (with disturbances).

Figure 10.

Nested saturation control response in roll angle (with disturbances).

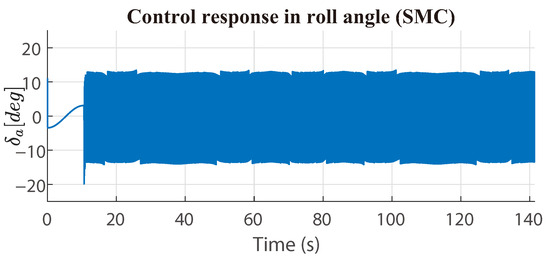

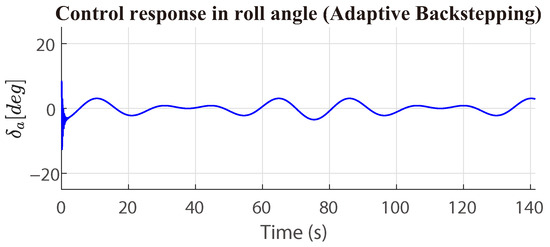

Analysing the control effort in the Table 1, the first-order sliding mode control (SM) presented a considerable control effort to achieve the control objective in the roll angle, and presented a bigger chattering effect in comparison with the second-sliding mode control (2SM), and the high-order sliding mode (HOSM); see the Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13. The control signal response for the backstepping adaptive law is presented in Figure 14.

Figure 11.

First-order sliding mode control response in roll angle (with disturbances).

Figure 12.

Second-order sliding mode control response in roll angle (with disturbances).

Figure 13.

High-order sliding mode control response in roll angle (with disturbances).

Figure 14.

Adaptive backstepping control response in roll angle (with disturbances).

4.2. Pitch Angle Response

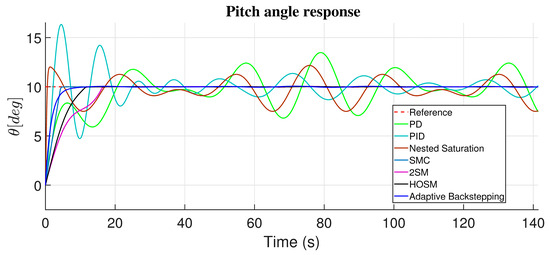

The pitch angle responses with the linear and nonlinear controllers are presented in Figure 15. The linear controllers PD and PID presented oscillations on the desired pitch angle, and the same signal is given by the nested saturation control, which occurred due to the wind gusts. The second-order sliding mode (2SM) achieves the desired pitch angle as an overdamped signal. The first-order sliding mode control (SM), adaptive backstepping technique, and the high-order sliding mode (HOSM) achieve the desired pitch angle as a critically damped signal form; see the Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Response in pitch angle (with disturbances).

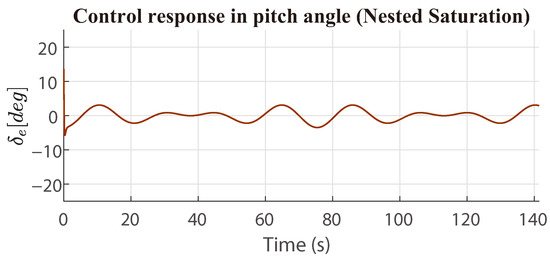

The control law with a small error presented in pitch angle is the adaptive backstepping, which can be appreciated in the Table 2. The PD control presents a significant error in pitch angle. Figure 16 and Figure 17 present the control signal response in the presence of disturbances in the PD and PID controllers, respectively. The control signal for the nested saturation control can be appreciated in Figure 18.

Table 2.

error and control effort in pitch angle.

Figure 16.

PD control response in pitch angle (with disturbances).

Figure 17.

PID control response in pitch angle (with disturbances).

Figure 18.

Nested saturation control response in pitch angle (with disturbances).

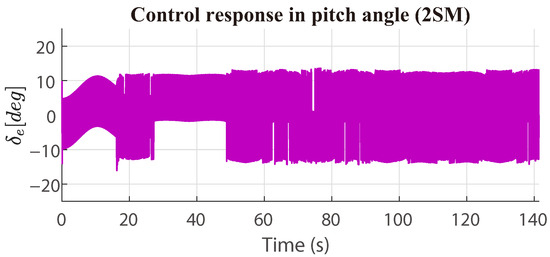

The PID control presented a small control effort to achieve the desired pitch angle, and the first-order sliding modes applied a considerable control effort to achieve the desired pitch angle; see Table 2. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 19, Figure 20 and Figure 21, the first-order sliding mode control exhibits the most significant chattering effect compared to the second-order sliding mode (2SM) and high-order sliding mode (HOSM) controllers.

Figure 19.

First-order sliding mode control response in pitch angle (with disturbances).

Figure 20.

Second-order sliding mode control response in pitch angle (with disturbances).

Figure 21.

High-order sliding mode control response in pitch angle (with disturbances).

The control signal for the adaptive backstepping technique can be appreciated in Figure 22.

Figure 22.

Adaptive backstepping control response in pitch angle (with disturbances).

4.3. Trajectory Follow by the Coaxial-Rotor MAV

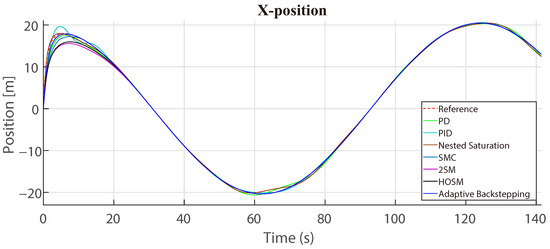

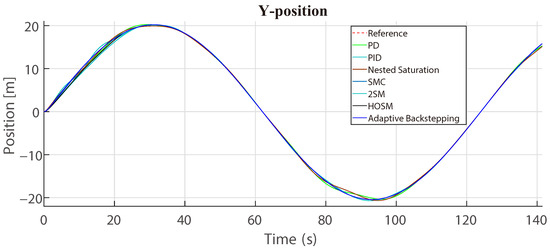

In Figure 23 and Figure 24, the trajectory followed by the coaxial-rotor MAV and every linear and nonlinear controller in the x-axis and y-axis, respectively, are presented. The altitude is affected by the disturbances caused by wind gusts, which can be seen in Figure 25. Finally, in Figure 26, the complete trajectory to follow by the coaxial-rotor MAV is presented.

Figure 23.

Controllers response in X-axis (with disturbances).

Figure 24.

Controllers response in Y-axis (with disturbances).

Figure 25.

Controllers response in Z-axis (with disturbances).

Figure 26.

Trajectory in 3D (with disturbances).

5. Discussion

In this work, a comparison is presented between seven controllers in path-following applied to a coaxial-rotor MAV, including linear and nonlinear control laws. The linear controllers are Proportional–Derivative (PD) and Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID). The nonlinear controllers include nested saturation, sliding mode methodologies based on first-, second-order, and high-order systems, as well as the adaptive backstepping technique.

The control laws were designed for path-following through stabilizing the roll and pitch angles. The yaw angle is considered constant when the motors are operating at the same velocity; consequently, the yaw angle remains unchanged during path-following. The altitude control in the coaxial-rotor MAV was achieved using a PID control.

In roll angle, the PID control at the first twenty seconds presented an initial overshoot bigger than the nested saturation control. After twenty seconds, some oscillations persisted due to the disturbances by wind gusts, and the PD control in roll angle presented oscillations too. Still, the nested saturation control presented a slight oscillation in magnitude, in comparison with the PD and PID control (the same signal responses are obtained in the pitch angle).

The three methodologies based on sliding modes achieved the desired roll angle in an overdamped signal form, and the controllers based on sliding mode presented an acceptable response in the presence of unknown disturbances. Still, the control signal has presented the undesired chattering effect. The chattering impact was reduced but not eliminated by the high-order sliding mode control in the roll angle (the same effect is presented in the pitch angle).

The better control response to follow the desired path has been presented by the adaptive backstepping. With this adaptive control law, it was possible to achieve the desired roll and pitch angles in a critically damped signal form. Still, in these controllers, an adaptation law was designed to estimate the disturbances caused by wind gusts, and the control law considers it.

The control laws that presented a minor error in roll and pitch angles were the adaptive backstepping, and the bigger error in roll and pitch angles was given by the second-order sliding mode and the PD, respectively.

The PD and PID controllers demonstrated a smaller control effort in roll angle. Still, the smaller control effort signal in pitch angle was presented by the PID control, and the second place of control effort in roll angle was the adaptive backstepping. With the first-order sliding mode control, a bigger control effort was required in roll and pitch angles to achieve the control objective.

In conclusion, for this work, the better response in path-following with the coaxial-rotor MAV was achieved by the adaptive backstepping control, because the adaptive backstepping technique presented the smallest error for the control objective in roll and pitch angles than the other control techniques presented in this work. Furthermore, the adaptive backstepping required only more control effort than the PD and PID controllers, and it presented non-oscillatory behavior in the presence of external disturbances.

Future work should involve completing the electronic system for the prototype coaxial-rotor MAV to conduct experiments and test the seven control laws developed in this work in real flights. It should be mentioned that we have finished the physical prototype coaxial-rotor MAV (aerodynamic structure), which is the same as we developed in the Solid Works software; see Figure 1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.E.F. and J.A.S.E.; methodology, A.T.E.F.; software, I.G.E.; validation, A.T.E.F. and I.G.E.; formal analysis, J.A.O.S.; investigation, A.T.E.F.; resources, I.G.E. and J.A.S.E.; data curation, J.A.S.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T.E.F.; writing—review and editing, J.A.S.E. and I.G.E.; visualization, J.A.S.E.; supervision, J.A.O.S.; project administration, J.A.O.S.; funding acquisition, A.T.E.F. and J.A.O.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MAV | Mini Aerial Vehicle |

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| SO(3) | Special Orthogonal Group in 3D |

| PD | Proportional–Derivative |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative |

| SMC | Sliding Mode Control |

| 2SM | Second-order Sliding Mode |

| HOSM | High Order Sliding Mode |

References

- Prior, S.; Bell, C. Empirical Measurements of Small Aerial Co-Axial Rotor Systems. J. Sci. Innov. 2011, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, P.; Jeyan, J. Hover Performance Analysis of Coaxial Mini Unmanned Aerial Vehicle for Applications in Mountain Terrain. Vilnius Gedim. Tech.-Univ.-Aviat. 2022, 26, 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Wei, Y.; Wang, W.; Deng, H. Longitudinal Attitude Control Decoupling Algorithm Based on the Fuzzy Sliding Mode of a Coaxial-Rotor UAV. Electronics 2019, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, K.; Deng, H.; Li, D. Research on the Control Algorithm of Coaxial Rotor Aircraft based on Sliding Mode and PID. Electronics 2019, 8, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Kanani, A.; Panchal, N.; Mathur, H. Dynamic Analysis of Coaxial Rotor Systems. Int. J. Mech. Prod. Eng. Res. Dev. 2020, 10, 1433–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Deng, H.; Pan, Z.; Li, K.; Chen, H. Research on a Combinatorial Control Method for Coaxial Rotor Aircraft Based on Sliding Mode. Def. Technol. 2022, 18, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Su, C. Dynamic Observer-based H-infinity Robust Control for a Ducted Coaxial-rotor UAV. IET Control Theory Appl. 2022, 16, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehl, A.; Rafaralahy, H.; Boutayeb, M.; Martinez, B. Aerodynamic Modelling and Experimental Identification of a Coaxial-Rotor UAV. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2020, 68, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, H.; Benedict, M.; Kang, H. Design, development, and flight testing of a tube-launched coaxial-rotor based micro air vehicle. Int. J. Micro Air Veh. 2022, 14, 17568293221117189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xiao, J.; Zheng, Y.; Alagappan, N.; Feroskhan, M. Design, Modeling, and Control of a Coaxial Drone. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2024, 40, 1650–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Hao, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, L. The Control Algorithm and Experimentation of Coaxial Rotor Aircraft Trajectory Tracking Based on Backstepping Sliding Mode. Aerospace 2021, 8, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glida, H.; Chelihi, A.; Abdou, L.; Sentouh, C.; Perozzi, G. Trajectory Tracking Control of a Coaxial Rotor Drone: Time-delay Estimation-based Optimal Model-free Fuzzy Logic Approach. ISA Trans. 2023, 137, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H.; Poole, C.; Safko, J. Classical Mechanics; Adison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, P.; Lozano, R.; Dzul, A. Modelling and Control of Mini-Flying Machines; Springer: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, L.; Dzul, A.; Lozano, R.; Pégard, A. Quad Rotorcraft Control: Vision-Based Hovering and Navigation; Springer: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, O.M. Intermediate Dynamics for Engineers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ardema, M.D. Newton-Euler Dynamics; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, J.J. Introduction to Robotics Mechanics and Control, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education International: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stengel, R.F. Flight Dynamics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, M. Flight Dynamics Principles, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, B.; Lewis, F.; Johnson, E. Aircraft Control and Simulation, 3rd ed.; Jhon Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mclean, D. Automatic Flight Control Systems; Prentice Hall International: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza-Fraire, T.; Dzul, A.; Parada, R.; Sáenz, A. Design of Control Laws and State Observers for Fixed-WIng UAVs: Simulation and Experimental Approaches; Elsevier: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, R.; Santibañez, V.; Loría, L. Control of Robot Manipulators in Joint Space; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata, K. Modern Control Engineering, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Teel, A. Global stabilization and restricted tracking for multiple integrators with bounded controls. Syst. Control Lett. 1992, 18, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H. Nonlinear Systems, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shtessel, Y.; Edwards, C.; Fridman, L.; Levant, A. Sliding Mode Control and Observation; Birkhäuser: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Levant, A. Robust exact differentition via sliding mode technique. Automatica 1998, 34, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, A. Construction principles of 2-sliding mode design. Automatica 2007, 43, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, A. Higher-order sliding modes, differentiation and output-feedback control. Int. J. Control 2003, 76, 924–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åström, K.; Wittenmark, B. Adaptive Control, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kristić, M.; Kanellakopoulos, I.; Kokotović, P. Nonlinear and Adaptive Control Design; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Wen, C.; Zhou, J. Adaptive Backstepping Control of Uncertain Systems with Actuator Failures, Subsystem Interactions, and Nonsmooth Nonlinearities; CRC Press: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).