Ricinus communis as a Sustainable Alternative for Biodiesel Production: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bias Assessment in Studies

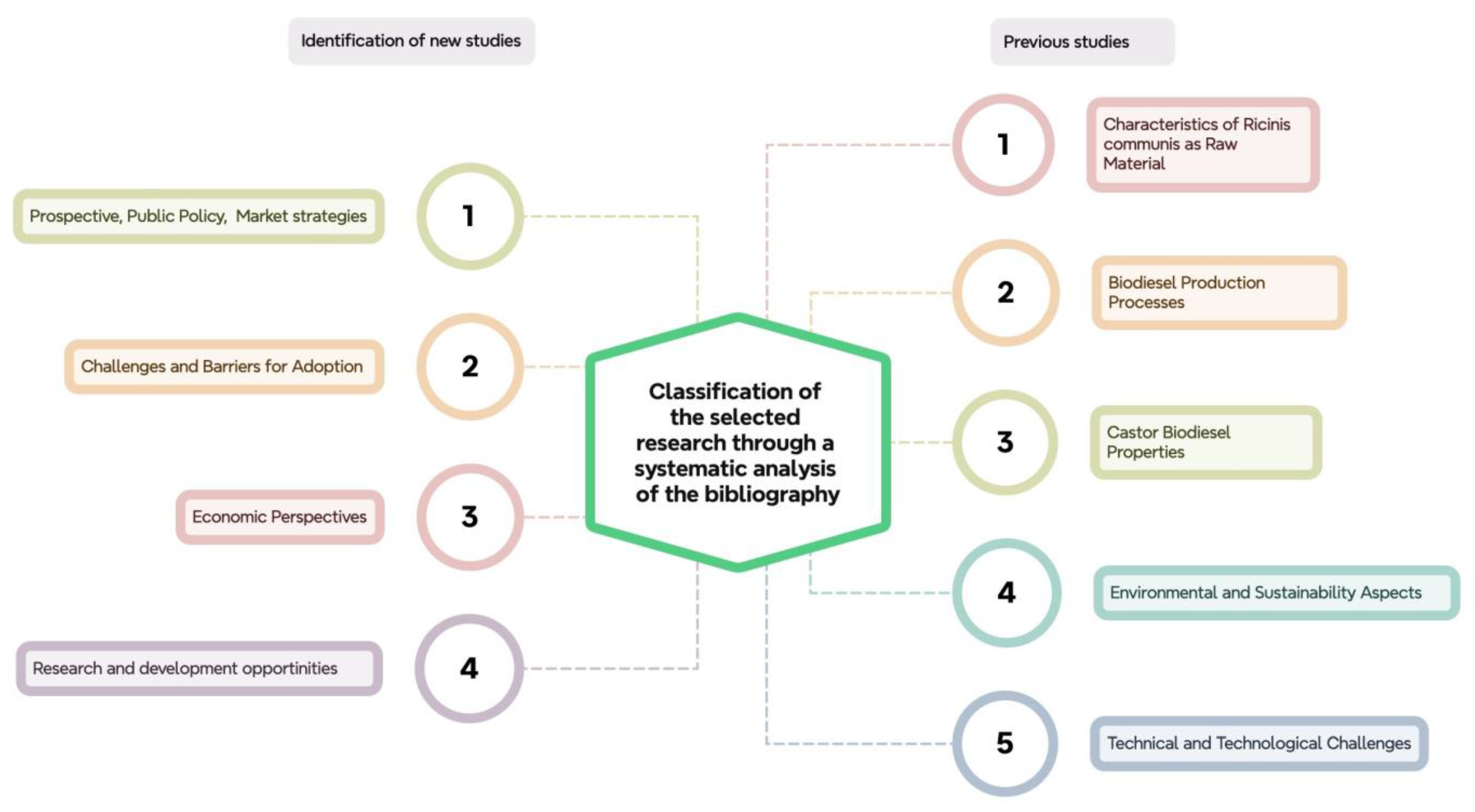

2.2. Analysis and Structure

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Ricinus communis as Raw Material

3.1.1. Oil Composition and Fatty Acid Profile

3.1.2. Agronomic Yield and Productivity

3.1.3. Elicitation

3.2. Biodiesel Production Processes

3.2.1. Conventional Alkaline Transesterification

3.2.2. Heterogeneous Catalysis

3.2.3. Enzymatic Processes

3.2.4. Supercritical Processes

3.3. Castor Biodiesel Properties

3.3.1. Detailed Physicochemical Characteristics

3.3.2. Combustion Properties and Emissions

3.3.3. Oxidative Stability and Storage

3.3.4. Property Improvement Strategies

3.4. Environmental and Sustainability Aspects

3.4.1. Use of Marginal Lands and Socio-Environmental Impacts

3.4.2. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

3.4.3. Waste Management and Circular Economy

3.5. Technical and Technological Challenges

3.5.1. Challenges in Biodiesel Production

3.5.2. Processing Challenges

3.5.3. Agronomic Challenges

3.6. Research and Development Opportunities

3.6.1. Advanced Genetic Improvement

3.6.2. Innovate Processing Technologies

3.7. Economic Perspectives

3.7.1. Economic Competitiveness

3.7.2. Policies and Regulations

3.8. Challenges and Barriers for Adoption

3.8.1. Technical

3.8.2. Economic

3.8.3. Regulatory

- Sustainability certification: Sustainability certification schemes for biofuels may not include specific criteria for castor grown on marginal lands, limiting access to premium markets [43].

- Safety regulations: The presence of ricin in seeds requires special safety protocols in processing, increasing costs and regulatory complexity [66].

- Trade barriers: Tariffs and non-tariff barriers can limit international trade of castor biodiesel, especially between developing and developed countries [80].

3.9. Prospective

3.9.1. Priority Research Directions

3.9.2. Public Policy

3.10. Market Strategies

3.10.1. Development of Niche Markets and Specialized Applications

3.10.2. Product Diversification, Supply Chains, and Strategic Alliances

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2024. IEA Publications. 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2024 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Jeswani, H.K.; Chilvers, A.; Azapagic, A. Environmental sustainability of biofuels: A review. Proc. R. Soc. A 2020, 476, 20200351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera Flores, M.M.; Sánchez Castro, M.A.; Ávila Vázquez, V.; Correa Aguado, H.C.; García Torres, J. Evaluation of the lipase from castor bean (Ricinus communis L.) as a potential agent for the remediation of used lubricating oil contaminated soils. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2022, 20, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAOSTAT Statistical Database; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Chakrabarty, S. Castor (Ricinus communis): An Underutilized Oil Crop in the. In Agroecosystems: Very Complex Environmental Systems; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; p. 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, A.; Ying, S.; Lu, J.; Xie, Y.; Amoanimaa-Dede, H.; Boateng, K.G.A.; Chen, M.; Yin, X. Castor oil (Ricinus communis): A review on the chemical composition and physicochemical properties. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 41, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setayeshnasab, M.; Sabzalian, M.R.; Rahimmalek, M. The relation between apomictic seed production and morpho-physiological characteristics in a world collection of castor bean (Ricinus communis L.). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, S.S.; Navarro, I.P.; González, M.D. ¿Cómo hacer una revisión sistemática siguiendo el protocolo PRISMA?: Usos y estrategias fundamentales para su aplicación en el ámbito educativo a través de un caso práctico. Bordón Rev. Pedagog. 2022, 74, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios Serna, K.V.; Orozco Núñez, D.M.; Pérez Navas, E.C.; Conde Cardona, G. Nuevas recomendaciones de la versión PRISMA 2020 para revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Acta Neurológica Colomb. 2021, 37, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Figueroa, C.; Cea, M.; Paneque, M.; González, M.E. Oil content and fatty acid composition in castor bean naturalized accessions under Mediterranean conditions in Chile. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.K.; Borugadda, V.B.; Reshad, A.S.; Bhalerao, M.S.; Tiwari, P.; Goud, V.V. Comparative study of physicochemical and rheological property of waste cooking oil, castor oil, rubber seed oil, their methyl esters and blends with mineral diesel fuel. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2021, 4, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, Y.A.; Fenta, F.W.; Birhan, Y.S. Fatty Acid Composition and Physicochemical Properties of Ricinus communis Seed Oil Grown from Jabi Tehinan Woreda, Ethiopia. Eur. J. Biophys. 2024, 12, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Chang, X.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Y. Castor oil-based adhesives: A comprehensive review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 209, 117924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-González, C.S.; Gómez-Falcon, N.; Sandoval-Salas, F.; Saini, R.; Brar, S.K.; Ramírez, A.A. Production of biodiesel from castor oil: A review. Energies 2020, 13, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilian, Y.; Babaeian, M.; Caballero-Calvo, A. Optimization of castor bean (Ricinus communis L.) cultivation methods using biostimulants in an arid climate. Euro-Mediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 2023, 8, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, E.S.G.; Abd Allah, S.A.; Bahnasawy, A.H.; Hashish, H.M.A. Enhancing bio-oil yield extracted from Egyptian castor seeds by using microwave and ultrasonic. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llaven Valencia, G.; Borbon Gracia, A.; Ochoa Espinoza, X.M.; Antuna Grijalva, O.; Hernández Hernández, A.; Coyac Rodríguez, J.L. Productividad de higuerilla (Ricinus communis L.) en el norte de Sinaloa. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agrícolas 2019, 10, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamariz, M.N.B.; Calzada, R.T.; Cohen, I.S.; Hernández, A.F.; Valle, M.Á.V.; Sandoval, A.P. Castor seed yield at suboptimal soil moisture: Is it high enough? Cienc. Investig. Agrar. 2019, 46, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazoglou, E.G.; Alexopoulou, E.; Papadopoulos, G.K.; Economou-Antonaka, G. Tolerance to drought and water stress resistance mechanism of castor bean. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, U.; Gul, M.F.; Aslam, M.U.; Rehman, F.U.; Farooq, U. Do structural and functional traits modulation determine the ecological fate of castor bean (Ricinus communis L.) under variable pedospheric and atmospheric conditions? S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 177, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huibo, Z.; Yong, Z.; Rui, L.; Guorui, L.; Jianjun, D.; Qi, W.; Fenglan, H. Analysis of the mechanism of Ricinus communis L. tolerance to Cd metal based on proteomics and metabolomics. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0272750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, A.; Awan, M.I.; Sadaf, S.; Mahmood, A.; Javed, T.; Shah, A.N.; Siuta, D. Sulfur enhancement for the improvement of castor bean growth and yield, and sustainable biodiesel production. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 905738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales-Serna, R.; Arellano-Arciniega, S.; Nava-Berumen, C.A.; Jiménez-Ocampo, R.; Espinoza, S.S.; Borja-Bravo, M.; Martínez-Reyes, E. Productividad y calidad del grano de higuerilla cultivada en el Centro-Norte de México. Ecosistemas Recur. Agropecu. 2023, 10, e3223. [Google Scholar]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Ali, N.; Akmal, M.; Alotaibi, M.; Refay, Y.; Dindaroglu, T.; Abdul-Wajid, H.H.; Battaglia, M.L. Drought stress impacts on plants and different approaches to alleviate its adverse effects. Plants 2021, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieb, M.; Gachomo, E.W. The role of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in plant drought stress responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, A.; Shahnazari, A. The effect of deficit irrigation strategies on the efficiency from plant to es-sential oil production in peppermint (Mentha piperita L.). Front. Water 2021, 3, 682640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angassa, K.; Tesfay, E.; Weldmichael, T.G.; Kebede, S. Response surface methodology process optimization of biodiesel production from castor seed oil. J. Chem. 2023, 2023, 6657732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitbani, F.O.; Tjitda, P.J.P.; Wogo, H.E.; Detha, A.I.R. Preparation of ricinoleic acid from castor oil: A review. J. Oleo Sci. 2022, 71, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yuan, H.; Ma, X.; Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Peng, Q.; Tan, Y. Synthesis of high molecular weight poly (ricinoleic acid) via direct solution polycondensation in hydrophobic ionic liquids. RSC Sustain. 2024, 2, 2541–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibar, M.E.; Hilal, L.; Çapa, B.T.; Bahçıvanlar, B.; Abdeljelil, B.B. Assessment of homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts in transesterification reaction: A mini review. ChemBioEng Rev. 2023, 10, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, D.A.; Amin, A.K.; Wijaya, K.; Triyono, T.; Trisunaryanti, W.; Fitroturokhmah, A.; Oh, W.C. MgO/γ-Alumina and CaO/γ-Alumina Catalysts for The Transesterification of Castor Oil (Ricinus communis) into Biodiesel. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2024, 43, 1622–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Xiao, Y.; Abulizi, A.; Okitsu, K.; Maeda, Y.; Ren, T. Surfactant-modified ZnFe2O4/CaOPS porous acid-base bifunctional catalysts for biodiesel production from waste cooking oil and process optimization. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschona, A.; Spanou, A.; Pavlidis, I.V.; Karabelas, A.J.; Patsios, S.I. Optimization of enzymatic transesterification of acid oil for biodiesel production using a low-cost lipase: The effect of transesterification conditions and the synergy of lipases with different regioselectivity. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 8168–8189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Bravo, S.G.; Aguilera-Vázquez, L.; Castañeda-Chávez, M.D.R.; Gallardo-Rivas, N.V. Condiciones del proceso de transesterificación en la producción de biodiésel y sus distintos mecanismos de reacción. TIP Rev. Espec. Cienc. Químico-Biológicas 2022, 25, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toldrá-Reig, F.; Mora, L.; Toldrá, F. Developments in the use of lipase transesterification for biodiesel production from animal fat waste. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaheldeen, M.; Mariod, A.A.; Aroua, M.K.; Rahman, S.A.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Fattah, I.R. Current state and perspectives on transesterification of triglycerides for biodiesel production. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.S.; Kumar, N.; Gautam, R. Supercritical transesterification route for biodiesel production: Effect of parameters on yield and future perspectives. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2021, 40, e13685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Gómez, L.; Ladero, M.; Calvo, L. Enzymatic production of biodiesel from alperujo oil in supercritical CO2. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2021, 171, 105184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, L.M.; Shago, M.I.; Burhanudden, R.H.; Suleiman, G. Physicochemical analysis and characterization of biodiesel production from Ricinus communis seed oil. FUDMA J. Sci. 2021, 5, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, S.; Jule, L.T.; Gudata, L.; Nagaraj, N.; Shanmugam, R.; Dwarampudi, L.P.; Ramaswamy, K. Preparation and characterization analysis of biofuel derived through seed extracts of Ricinus communis (castor oil plant). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, D.; Abdulkadir, M.; Befekadu, A. Production of biodiesel from mixed castor seed and microalgae oils: Optimization of the production and fuel quality assessment. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1536160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayi, B.A.; Khamisu, A.I.; Abubakar, T.S.; Shitu, I.G. Biodiesel production from castor oil and analysis of its physical properties. J. Found. Appl. Phys. 2023, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Carrino, L.; Visconti, D.; Fiorentino, N.; Fagnano, M. Biofuel production with castor bean: A win–win strategy for marginal land. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Cho, H. Combustion and emission of castor biofuel blends in a single-cylinder diesel engine. Energies 2023, 16, 5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuepeng, S.; Klinkaew, N.; Thumanu, K.; Theinnoi, K.; Sukjit, E.; Dearn, K. Effects of castor oil as lubricity enhancer on friction and wear characteristics of piston engine running on diesohol. Int. J. Engine Res. 2025, 6, 1305–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longanesi, L.; Pereira, A.P.; Johnston, N.; Chuck, C.J. Oxidative stability of biodiesel: Recent insights. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2022, 16, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrat, M.A.; Rasul, M.G.; Khan, M.M.K.; Mofijur, M.; Ahmed, S.F.; Ong, H.C.; Vo, D.N.; Show, P.L. Techniques to improve the stability of biodiesel: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2209–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, K.J.; Hernández-Sierra, M.T.; Báez, J.E.; Rodríguez-deLeón, E.; Aguilera-Camacho, L.D.; García-Miranda, J.S. On the tribological and oxidation study of xanthophylls as natural additives in castor oil for green lubrication. Materials 2021, 14, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aengchuan, P.; Wiangkham, A.; Klinkaew, N.; Theinnoi, K.; Sukjit, E. Prediction of the influence of castor oil–ethanol–diesel blends on single-cylinder diesel engine characteristics using generalized regression neural networks (GRNNs). Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanuskar, S.; Naik, S.N.; Pant, K.K. Castor oil-based derivatives as a raw material for the chemical industry. In Catalysis for Clean Energy and Environmental Sustainability: Biomass Conversion and Green Chemistry-Volume 1; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 209–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotovuša, M.; Pucko, I.; Racar, M.; Faraguna, F. Biodiesel produced from propanol and longer chain alcohols—Synthesis and properties. Energies 2022, 15, 4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidane, G.; Makonnen, B.T. Dryland Agriculture and Climate Change Adaptation in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Case of Policies, Technologies, and Strategies in Ethiopia. 2024. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/141481 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Khan, I.; Ali, S.M.; Chattha, M.U.; Barbanti, L.; Calone, R.; Mahmood, A.; Albishi, T.S.; Hassan, M.U.; Qari, S.H. Neem and castor oil–coated urea mitigates salinity effects in wheat by improving physiological responses and plant homeostasis. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 3915–3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, J.; Andres, C.; Assaad, F.F.; Bellon, S.; Coquil, X.; Doetterl, S.; Dierks, J. Syntropic farming systems for reconciling productivity, ecosystem functions, and restoration. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, e314–e325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijekoon, W.; Priyashantha, H.; Gajanayake, P.; Manage, P.; Liyanage, C.; Jayarathna, S.; Kumarasinghe, U. Review and prospects of phytoremediation: Harnessing biofuel-producing plants for environmental remediation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severino, L.S.; da Silva Mendes, B.S.; Saboya, R.D.C.C.; Barros, L.A.; de Farias Marinho, D.R. Nutrient content of solvent-extracted castor meal separated in granulometric fractions by dry sieving and applied as organic fertilizer. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 161, 113178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, P.J.M.; da Silva, R.M.; Neto, C.A.C.G.; Gomes e Silva, N.C.; Souza, J.E.D.S.; Nunes, Y.L.; Sousa dos Santos, J.C. An overview on the conversion of glycerol to value-added industrial products via chemical and biochemical routes. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022, 69, 2794–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Singh, N.K.; Sharma, A.; Lim, W.H.; Palamanit, A.; Alhussan, A.A.; El-kenawy, E.S.M. Bio-oil yield maximization and characteristics of neem-based biomass at optimum conditions along with feasibility of biochar through pyrolysis. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 085104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbani, N.H.A.; Meelad, A.; Mohammed, A.; Kwadikha, A.; Tweib, S. Biodiesel Production from Castor Oil. Al-Khwarizmi Eng. J. 2025, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldetensy, H.Z.; Zeleke, D.S.; Tibba, G.S. Study of the impact on emissions and engine performance of diesel fuel additives made from cotton and castor blended seed oils. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obayomi, K.S.; Bello, J.O.; Ogundipe, T.A.; Olawale, O. Extraction of castor oil from castor seed for optimization of biodiesel production. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 445, p. 012055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleque, A.; Cetin, S.Y.; Hassan, M.; Sulaiman, M.H.; Rosli, A.H. A systematic review on corrosive-wear of automotive components materials. J. Tribol. 2022, 35, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pilu, S.R.; Ghidoli, M.; Padovani, D. Preliminary characterization of a worldwide collection of castor bean (Ricinus communis L.) Germplasm. In Scientific Conference on Breeding to Meet Environmental and Societal Challenges; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; p. 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jigyasu, D.K.; Patidar, O.P.; Shabnam, A.A.; Kumar, A. Castor Plant in Ericulture: Opportunities and Challenges. In Ricinus communis: A Climate Resilient Commercial Crop for Sustainable Environment; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafaro, V.; Testa, G.; Patanè, C. Castor: A Renewed Oil Crop for the Mediterranean Environment. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landoni, M.; Bertagnon, G.; Ghidoli, M.; Cassani, E.; Adani, F.; Pilu, R. Opportunities and challenges of castor bean (Ricinus communis L.) genetic improvement. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wu, D.I.; Yang, T.; Sun, C.; Wang, Z.; Han, B.; Wu, S.; Yu, A.; Chapman, M.A.; Muraguri, S.; et al. Genomic insights into the origin, domestication and genetic basis of agronomic traits of castor bean. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilvel, S.; Manjunatha, T.; Lavanya, C. Castor breeding. In Fundamentals of Field Crop Breeding; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 945–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, I.; Sagadevan, S.; Murugan, B.; Muraza, O. Castor oil (Ricinus communis). Biorefinery Oil Prod. Plants Value-Added Prod. 2022, 1, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houshyar, E.; Mahmoodi-Eshkaftaki, M.; Ghani, A.; Arazo, R. Optimized biodiesel production from Ricinus communis oil using CaO, C/CaO and KOH catalysts under conventional and ultrasonic conditions. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2024, 26, 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.Y. Reaction Kinetics Mechanisms of Novel Intensified Transesterification Methods via Microturbulence and Micro-Level Diffusion for Biodiesel Production. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK, 2021. Available online: http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/id/eprint/456809 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Awogbemi, O.; Desai, D.A. Recent advances in purification technologies for biodiesel-derived crude glycerol. Int. J. Ambient Energy 2025, 46, 2533373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, M. The making of speculative biodiesel commodities on the agroenergy frontier of the Brazilian Northeast. Antipode 2020, 52, 1794–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilves, R.; Küüt, A.; Allmägi, R.; Olt, J. The Impact of RED III Directive on the Use of Renewable Fuels in Transport on the Example of Estonia. Rigas Tech. Univ. Zinat. Raksti 2024, 28, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, M.; Lal, S.; Khan, O.; Ahmad, M.; Lal Meena, S.; Salvi, B.L. Sustainable regulatory framework for ethanol and biodiesel blending with petro-fuels in India to meet fuel demand: A review of biofuel policies. Biofuels 2025, 16, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.C.C. Policy, regulation, development and future of biodiesel industry in Brazil. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 4, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Salas, F.; Méndez-Carreto, C.; Ortega-Avila, G.; Barrales-Fernández, C.; Hernández-Ochoa, L.R.; Sanchez, N. A biorefinery approach to biodiesel production from castor plants. Processes 2022, 10, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busari, R.A.; Olaoye, J.O.; Adebayo, E.S.; Fadeyibi, A. Development and evaluation of a combined roaster expeller for castor seeds for biodiesel production. Res. Agric. Eng. 2022, 68, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RL, M.; Mishra, A.K. Market efficiency and price risk management of agricultural commodity prices in India. J. Model. Manag. 2023, 18, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichare, S.A.; Morya, S. Exploring waste utilization potential: Nutritional, functional and medicinal properties of oilseed cakes. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1441029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocyigit, E.; Kocaadam-Bozkurt, B.; Bozkurt, O.; Ağagündüz, D.; Capasso, R. Plant toxic proteins: Their biological activities, mechanism of action and removal strategies. Toxins 2023, 15, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Kong, F.; Zhang, B.; Xie, Q.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, H. Research Progress on Castor Harvesting Technology and Equipment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monika; Pathak, V.V.; Banga, S. A comprehensive analysis of refining technologies for biodiesel purification. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, V. Strategies for the Transformation of Waste Cooking Oils into High-Value Products: A Critical Review. Polymers 2025, 17, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramovic, J.M.; Marjanović Jeromela, A.M.; Krstić, M.S.; Kiprovski, B.M.; Veličković, A.V.; Rajković, D.D.; Veljković, V.B. Castor oil extraction: Methods and impacts. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2025, 54, 60–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Sabri, M.A.; Aresta, M.; Dibenedetto, A.; Dumeignil, F. Sustainable synergy: Unleashing the potential of biomass in integrated biorefineries. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2025, 9, 338–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipkoech, R.; Takase, M.; Ahogle, A.M.A.; Ocholla, G. Analysis of properties of biodiesel and its development and promotion in Ghana. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Aguilar, F.A.; Mena-Cervantes, V.Y.; Hernandez-Altamirano, R. Analysis of public policies and resources for biodiesel production in México. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 196, 107762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Kumar, A.; Singla, A.; Dewan, R. Production and tribological characterization of castor based biodiesel. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 10942–10949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamood ur Rehman, M.; Hussain, M.; Akhter, P.; Jamil, F. Breaking Barriers in Biodiesel: From Feedstock Challenges to Technological Advancements. Chem. Afr. 2025, 8, 2225–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwer, A.; Hussain, M.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.A.H.; Inayat, A.; Rafiq, S.; Khurram, M.S.; Ul-Haq, N.; Shah, S.N.; Din, A.A.; Ahmad, I.; et al. Suitability of biofuels production on commercial scale from various feedstocks: A critical review. ChemBioEng Rev. 2022, 9, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, S.; Sarma, S.J.; Brar, S.K. A comprehensive review of castor oil-derived renewable and sustainable industrial products. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2023, 42, e14008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, A.G.; Vázquez, V.Á.; Flores, M.M.A.; Cerrillo-Rojas, G.V.; Correa-Aguado, H.C. Sustainable castor bean biodiesel through Ricinus communis L. lipase extract catalysis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 1297–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasannakumar, P.; Sankarannair, S.; Prasad, G.; S, P.; P, V.; S, S.; Shanmugam, R. Bio-based additives in lubricants: Addressing challenges and leveraging for improved performance toward sustainable lubrication. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 17969–17997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Kasture, J.; Dangate, M.S. Production of Bio-Diesel and By-Product Processing. In Biomass and Solar-Powered Sustainable Digital Cities; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research | Records Identified in Databases | Duplicate Records | Records for Screening | Excluded Records | Records Selected by Title and Abstract | Records Excluded Due to Their Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospects and scientific advances for the production of biodiesel from R. communis | 1840 | 60 | 1780 | 1030 | 750 | 657 |

| Property | Castor Biodiesel | Soybean Biodiesel | Palm Biodiesel | ASTM D6751 | EN 14214 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density at 15 °C (kg/m3) | 920–940 | 870–890 | 860–880 | 860–900 | 860–900 |

| Kinematic viscosity at 40 °C (mm2/s) | 14–18 | 3.5–4.5 | 4.0–5.0 | 1.9–6.0 | 3.5–5.0 |

| Flash point (°C) | 260–290 | 178–190 | 164–180 | >130 | >120 |

| Cloud point (°C) | −2 to +5 | −2 to +3 | 13–16 | - | - |

| Pour point (°C) | −9 to −3 | −7 to −2 | 12–15 | - | - |

| Cetane number | 38–42 | 50–55 | 58–62 | >47 | >51 |

| Iodine number (g I2/100 g) | 82–88 | 120–140 | 50–55 | <120 | <120 |

| Heating value (MJ/kg) | 37.2–39.1 | 39.5–40.2 | 39.8–40.3 | - | - |

| Challenges | Problem | Author |

|---|---|---|

| Phase separation during transesterification | Delaying the settling of glycerol | Obayomi et al. [61] |

| Physical properties | Conventional water washing | Osorio-González et al. [14] |

| Presence of free fatty acids and water | Corrosion in carbon steel equipment | Maleque et al. [62] |

| Challenges | Problem | Author |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic variability | Inconsistent oil content and yield | Pilu et al. [63] |

| Pest-resistant | Vulnerable to specific threats | Jigyasu et al. [64] |

| Raising production costs and limiting viability | Plant morphology and capsule dehiscence | Cafaro et al. [65] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-González, M.; Ramos-López, M.A.; Villagómez-Aranda, A.L.; Rodríguez-Morales, J.A.; Campos-Guillén, J.; Mariscal-Ureta, K.E.; Amaro-Reyes, A.; Valencia-Hernández, J.A.; Saenz de la O, D.; Zavala-Gómez, C.E. Ricinus communis as a Sustainable Alternative for Biodiesel Production: A Review. Fuels 2025, 6, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels6040090

Martínez-González M, Ramos-López MA, Villagómez-Aranda AL, Rodríguez-Morales JA, Campos-Guillén J, Mariscal-Ureta KE, Amaro-Reyes A, Valencia-Hernández JA, Saenz de la O D, Zavala-Gómez CE. Ricinus communis as a Sustainable Alternative for Biodiesel Production: A Review. Fuels. 2025; 6(4):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels6040090

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-González, Miriam, Miguel Angel Ramos-López, Ana L. Villagómez-Aranda, José Alberto Rodríguez-Morales, Juan Campos-Guillén, Karla Elizabeth Mariscal-Ureta, Aldo Amaro-Reyes, Juan Antonio Valencia-Hernández, Diana Saenz de la O, and Carlos Eduardo Zavala-Gómez. 2025. "Ricinus communis as a Sustainable Alternative for Biodiesel Production: A Review" Fuels 6, no. 4: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels6040090

APA StyleMartínez-González, M., Ramos-López, M. A., Villagómez-Aranda, A. L., Rodríguez-Morales, J. A., Campos-Guillén, J., Mariscal-Ureta, K. E., Amaro-Reyes, A., Valencia-Hernández, J. A., Saenz de la O, D., & Zavala-Gómez, C. E. (2025). Ricinus communis as a Sustainable Alternative for Biodiesel Production: A Review. Fuels, 6(4), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels6040090