Abstract

Biobutanol is becoming more relevant as a promising alternative biofuel, primarily due to its advantageous characteristics. These include a higher energy content and density compared to traditional biofuels, as well as its ability to mix effectively with gasoline, further enhancing its viability as a potential replacement. A viable strategy for attaining carbon neutrality, reducing reliance on fossil fuels, and utilizing sustainable and renewable resources is the use of biomass to produce biobutanol. Lignocellulosic materials have gained widespread recognition as highly suitable feedstocks for the synthesis of butanol, together with various value-added byproducts. The successful generation of biobutanol hinges on three crucial factors: effective feedstock pretreatment, the choice of fermentation techniques, and the subsequent enhancement of the produced butanol. While biobutanol holds promise as an alternative biofuel, it is important to acknowledge certain drawbacks associated with its production and utilization. One significant limitation is the relatively high cost of production compared to other biofuels; additionally, the current reliance on lignocellulosic feedstocks necessitates significant advancements in pretreatment and bioconversion technologies to enhance overall process efficiency. Furthermore, the limited availability of biobutanol-compatible infrastructure, such as distribution and storage systems, poses a barrier to its widespread adoption. Addressing these drawbacks is crucial for maximizing the potential benefits of biobutanol as a sustainable fuel source. This document presents an extensive review encompassing the historical development of biobutanol production and explores emerging trends in the field.

1. Introduction

As the climate crisis worsens and the world’s population grows, there is a growing demand for low-emissions technologies for energy supply, such as wind turbines, solar panels, anaerobic digestion, biomass heating, and residue valorization. Biofuel production has become one of the most viable substitutes to conventional fossil fuels, and it is playing a fundamental role in clean energy production [1]. In 2022, the demand for biofuels reached 4.3 EJ (1.7 × 1011 L), and, according to IEA, it is projected to achieve 10 EJ by 2030 under a scenario of 11% growth per year [2]. Biofuels have numerous applications, including transportation, heat generation, and electricity production [3]. They offer several benefits over petroleum-based fuels, such as reduction in carbon dioxide emissions, the ability to use residues as feedstock, a lower potential for greenhouse gases, greater environmental sustainability, and increased energy mix diversification [4]. Currently, bioethanol and biodiesel represent the vast majority of biofuel production worldwide, being 2.5 EJ and 1.4 EJ respectively [2].

Most of the fossil fuels used for transportation consist of liquid hydrocarbons, mainly gasoline (C4–C12) and diesel (C9–C25). Thus, biofuels like bio-alcohols and biodiesel can be viable substitutes for conventional liquid fossil fuels, and, currently, they are produced on a large scale in most of the developed countries in the world, using edible commodities such as sugarcane, corn starch, and palm oil as raw material. Polysaccharide-rich biomasses are the most attractive feedstock for biofuels production due to their ease of use [5]. First-generation biofuels are those that are produced from this kind of edible feedstock [6], and they conflict with the food industry, posing economic and sustainability barriers [7]. As a result, first-generation biofuels are limited and only represent 3% of transport fuel consumption worldwide [8]. To overcome this issue, the use of non-edible biomass as feedstock is the most investigated approach for biofuel synthesis, and, from this perspective, the final products obtained are known as second-generation biofuels [9].

Biomass, in the context of bioenergy, refers to the biodegradable components found in materials and waste originating from biological sources like agriculture (including animal and plant matter), forestry, and related industries. It also encompasses the biodegradable portion of industrial and municipal waste [10]. Biomass can be classified based on its composition (lignocellulosic, rich in protein, rich in sugars, or starchy), origin (agriculture, forestry, waste, etc.), and final use (transport biofuels, biomass for heat and power generation, and biomass for biorefineries and intermediates or energy carriers) [11]. Residual biomass from agroindustry or municipal waste could have a significant role in bioenergy and biofuel production, given the great availability of waste and the slight environmental impact on soil, as no lands are required for crops and there is no competition with food and other manufacturing sectors [12,13,14]. Therefore, the primary feedstock used to produce second-generation biofuels is usually low-value biomass, predominantly lignocellulosic materials, which possess high contents of cellulose and hemicellulose. Furthermore, residual oils and fats (yellow grease and residues from the slaughter industry) are also utilized [6]. Biofuels, such as biohydrogen [15], biomethane [16], biogas [17], biodiesel, bioethanol [18], and biobutanol [19], can be produced through biological (e.g., fermentation and anaerobic digestion), chemical (e.g., transesterification), or physical treatment (e.g., pyrolysis, gasification, hydrothermal reaction) of non-edible biomass. Therefore, second-generation biofuels represent a promising alternative to fossil fuels for energy production. Additionally, biomass valorization can reduce the amount of waste disposed of in dumping grounds, thereby reducing the environmental impact on soils. This is particularly important for the energy sector, which is currently seeking sustainable and environmentally friendly energy alternatives due to climate change [20]. Among all these energy carriers, the main concern relates to liquid biofuels, as they represent 40% of world energy consumption [21].

Alcohols, such as methanol, ethanol, and butanol, are considered sustainable biofuels since they can be produced by biological processes using renewable raw materials as feedstock. Due to the existence of hydroxyl groups, alcohols can supply a greater quantity of oxygen to the combustion process, improving the theoretical air requirement, enhancing heat of evaporation, and reducing PM and NOx emissions [22]. The benefits of blending bio-alcohols, mainly ethanol, and conventional fossil fuels, especially gasoline, are widely reported in the literature [23]. For this reason, many nations, such as China, the United States, Brazil, India, Colombia, and Mexico, have implemented laws to mix gasoline with bio-alcohols as a measure to combat climate change [24].

One of the most promising biofuels compared to others, such as bioethanol, is butanol (C4H9OH), which is formed by four carbon atoms and one hydroxyl group. This is caused by its high combustion heat, boiling point, and capacity to mix with gasoline in higher proportions without requiring any change in prevailing Otto-cycle engines [25]. These characteristics give butanol many advantages over other conventional fuels. Furthermore, butanol has a broad range of other applications as an intermediary for different manufactured products (polymers, brake fluids, lubricants, synthetic rubber, epoxies, paints, etc.) and is employed in the cosmetics and pharmaceutical industries [26].

Currently, most of the butanol produced worldwide is obtained from petroleum-derived chemicals, making this industry susceptible to fluctuations in crude oil prices due to conflicts in producing countries, environmental policies, and financial speculation, among other factors [27]. The global market volume of n-butanol, the most widely commercialized isomer, reached 5.2 million metric tons in 2021. Projections indicate that this market is expected to continue its growth trajectory over the next decade [28].

In addition to other methods, butanol can be synthesized via acetone–butanol–ethanol (ABE) fermentation, which is an anaerobic bioprocess that utilizes strains of the solventogenic bacteria. ABE fermentation involves the conversion of various carbon sources into solvents, including butanol, acetone, and ethanol, through metabolic pathways within the Clostridia bacteria. This process offers an alternative and sustainable approach to produce butanol, further highlighting the versatility of Clostridia strains in biotechnological applications. This method has been known for more than a century, and after the First World War, it became an important way to produce acetone, which was utilized for cordite synthesis before falling into disuse caused by the rise of the petrochemical industry in the 1950s [29]. Nonetheless, biobutanol is still unable to compete with the petrochemical industry because of its high manufacturing costs. As a result, researchers are actively focused on overcoming these limitations to enhance the profitability of the entire procedure [30]. To approach these barriers, researchers usually work on improving ABE fermentation processes, novel pretreatment technologies, and choosing low-cost biomass and non-edible waste materials, mostly agricultural and municipal residues, as feedstock. Butanol also exhibits lower corrosiveness than other liquid biofuels, reducing engine wear and facilitating its adoption in the automotive industry. Another significant advantage is its ability to blend in higher proportions with gasoline without compromising engine performance, making it a potentially more efficient fuel than ethanol [29].

To address these economic barriers, researchers have focused on optimizing fermentation processes, improving bacterial strains to enhance yields and butanol tolerance, and developing new pretreatment technologies to make non-edible biomass more accessible and cost-effective for biobutanol production. Additionally, the use of non-food residues holds the potential to further reduce costs and make biobutanol production more environmentally sustainable. This document reviews recent advances in biobutanol production, focusing on its use as an energy alternative, its production from low-cost raw materials, pretreatment, detoxification, fermentation, and recovery processes, and finally, emerging trends and novel approaches in this field.

2. Biobutanol as an Advanced Fuel Option

Biobutanol presents promising prospects as an energy source due to its thermodynamic and ecological advantages, which typically surpass those of other common fuels. Butanol can be utilized as an independent fuel or mixed with gasoline at different ratios. It is important to highlight that using high blending levels (up to 85%) of butanol may require engine modifications due to its low vapor pressure [31]. Compared to ethanol, butanol’s miscibility is quite superior, as ethanol can only be blended in concentrations of up to 15% without requiring changes in conventional engines. Additionally, butanol has an energy content that is equivalent to gasoline and 30% higher than that of ethanol [32]. Some of the most important properties of biobutanol, compared to those of other fuels, are shown in Table 1. Nevertheless, parameters such as the performance properties of GI motors, emissions, combustion conditions, and material compatibility must be considered to evaluate the feasibility of using this biofuel.

In general, the blending of bio-alcohols with gasoline has been shown to have positive effects on motor performance, combustion conditions, and pollutant emissions. Comparing butanol to other bio-alcohols like methanol, ethanol, and propanol, butanol exhibits numerous advantages in key parameters such as brake thermal efficiency (BTE), brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC), and carbon monoxide emissions. Generally, blending bio-alcohols with gasoline has shown positive effects on motor performance, combustion conditions, and pollutant emissions. However, when specifically comparing butanol to ethanol, methanol, and propanol, butanol stands out with its superior performance in terms of BTE, BSFC, and carbon monoxide emissions [33]. The current approach focuses on utilizing butanol–gasoline blends to enhance engine performance and environmental characteristics. Butanol has been proven to be an effective additive for gasoline, making it a favorable choice for improving the overall qualities of engines [26]. Table 2 shows some research conducted on this respect. The information shown in the table demonstrates that the addition of butanol to gasoline yields positive effects on engine performance, with observed increases of 2–12% in brake thermal efficiency (BTE) and 1–11% in brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC). Additionally, CO and NOx emissions were reduced in most cases, consistent with previous findings. Thus, the effects of butanol as a gasoline additive are predominantly positive.

Table 1.

Properties of butanol compared to those of other fuels [30]. The table shows a list of the most important features of butanol, compared to other biofuels (ethanol, and methanol) and gasoline.

Table 1.

Properties of butanol compared to those of other fuels [30]. The table shows a list of the most important features of butanol, compared to other biofuels (ethanol, and methanol) and gasoline.

| Properties | Petroleum-Based | Oil-Based | Bio-Alcohols | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gasoline | Diesel | FAME (Biodiesel) | Bio-Oil [34] | Methanol | Ethanol | Butanol | |

| Molecular formula | C4–C12 | C9–C20 [35] | C6–C22 [36] | - | CH3OH | C2H5OH | C4H9OH |

| Molecular weight (g/gmol) | 95–120 | 190–220 [37] | ≈295 [38] | - | 32 | 46 | 74 |

| Mass composition of C, H, O (%) | 86, 14, 0 | 86.8, 13.2, 0 [39] | 76.2, 12.6, 11.2 [39] | 54, 5, 34 | 37.5, 12.5, 50 | 52, 13, 35 | 65, 13.5, 21.5 |

| Heating Value (MJ/kg) | 44–46 | 43 [39] | 20.8–45.6 [40] | 16–20 | 22.7 [41] | 24.8 [41] | 36.4 [42] |

| Boiling point (°C) | 200 | ≈ 163–357 [35] | 340–375 [36] | - | 65 | 78 | 118 |

| Freezing point (°C) | −40 | −3 a −9 b [43] | −25 to 26 a −28 to 18 b | −10 to −20 b | −97 | −114 | −89 |

| Heat of vaporization (MJ/kg) | 0.36 | - | - | - | 1.20 | 0.92 | 0.43 |

| Energy density (MJ/L) | 32 | 36.3 [39] | 33.75 [39] | - | 16 | 19 | 30 |

| Density (Kg/m3) | 760 | 820–860 [44] | 860–890 [44] | 1200–1300 | 796 | 790 | 810 |

| Air: fuel ratio | 15:1 | 14.5:1 [35] | 13:1 | - | 7:1 | 9:1 | 12 |

| Cetane number | - | 40–45 [39] | 45–55 [39] | - | - | - | - |

| Motor octane number (MON) | 90 | - | - | - | 92 | 89 | 78 |

| Rating octane number (RON) | 95 | - | - | - | 106 | 107 | 96 |

| Flash point (°C) | −40 | 55–65 [40] | >150 [40] | 60–80 | 12 | 13 | 35 |

| Lubricity (µm) | - | 448 [43] | 351–567 [39] | - | 1100 | 1057 | 591 |

| Auto-ignition temperature (°C) | 257 | 210 | - | - | 463 | 423 | 397 |

a Cloud point: The temperature at which fuel begins to exhibit a cloudy appearance because of wax solidification. b Pour point: The temperature at which the wax content in the fuel reaches a level that causes gelation, rendering the fuel non-pumpable.

Table 2.

Effects of different types of butanol blending on environmental and performance parameters. The table shows some research about the effects on combustion performance (brake thermal efficiency (BTE) and brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC)) and emissions of pollutants (carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), hydrocarbons (HC), and nitrogen oxides (NOx)) using butanol blended with gasoline in different types of engines.

Table 2.

Effects of different types of butanol blending on environmental and performance parameters. The table shows some research about the effects on combustion performance (brake thermal efficiency (BTE) and brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC)) and emissions of pollutants (carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), hydrocarbons (HC), and nitrogen oxides (NOx)) using butanol blended with gasoline in different types of engines.

| Fuel Blending | Engine Features | BTE | BSFC | CO | CO2 | HC | NOx | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-Butanol 20% | Four-cylinder SI engine. 1000–5000 RPM | ≈▼2% | ≈▲8% | ≈▼9.07% | ≈▲3.21% | ≈▼18.86% | ≈▼6.41% | [45] |

| Sec-butanol 20% | ≈▲2% | ≈▲15% | ≈▼8.87% | ≈▲5.17% | ≈▼17.67% | ≈▼20.26% | ||

| Tert-butanol 20% | ≈▲2% | ≈▲10% | ≈▼3.07% | ≈▲2.33% | ≈▼12.50% | ≈▼27.79% | ||

| Iso-butanol 20% | ≈▲4% | ≈▲11% | ≈▼14.54% | ≈▲15.53% | ≈▼18.80% | ≈▲43.55% | ||

| n-butanol 10% | Four cylinders turbocharged GDI engine. Urban conditions (throttle opening 10% and 35%), using GT-power simulations software. 1000–5000 RPM | ≈▲1.5% | - | ≈▼3% | - | ≈▲10% | ≈▼1.5% | [46] |

| n-butanol 20% | ≈▲3.2% | - | ≈▼4% | - | ≈▲2% | ≈▼2.1% | ||

| n-butanol 30% | ≈▲3.5% | - | ≈▼5% | - | ≈▲28% | ≈▼3.9% | ||

| n-butanol 40% | ≈▲4.2% | - | ≈▼5% | - | ≈▲34% | ≈▼4.5% | ||

| n-butanol 100% | ≈▲10.3% | - | ≈▼20% | - | ≈▲85% | ≈▼10% | ||

| Iso-butanol 10% | Single cylinder 2600 RPM. The wide-open throttle condition was investigated at three different compression ratios (CR): 9:1, 10:1, and 11:1. | ≈▲1% | ≈▲5% | ≈▼4% | ≈▲5% | ≈▼8% | - | [47] |

| Iso-butanol 30% | ≈▲2% | ≈▲11% | ≈▼13% | ≈▲12% | ≈▼25% | - | ||

| Iso-butanol 50% | ≈▲12% | ≈▲15% | ≈▼30% | ≈▲22.5% | ≈▼27% | - | ||

| n-butanol 10% | 10 hp single cylinder 3000 RPM Uncoated | ≈▲2% | ≈▲1% | ≈▼5% | - | ≈▼10% | ≈▲5% | [48] |

| n-butanol 15% | ≈▲2% | ≈▲1.4% | ≈▼9% | - | ≈▼14% | ≈▲10% | ||

| n-butanol 10% | 10 hp single cylinder 3000 RPM Ceramic coated | ≈▲5.6 | ≈▲1% | ≈▼4% | - | ≈▼12% | ≈▲2% | |

| n-butanol 15% | ≈▲5.6 | ≈▲1% | ≈▼7% | - | ≈▼19% | ≈▲10% | ||

| n-butanol 25% | Four stroke spark ignition engines, under operation conditions of variable engine speed (between 1250 and 3000 RPM). | ≈▲3.6% | ≈▼2% | ▼27.8% | ▼15.9% | ▼3.9% | [41] | |

| n-butanol 50% | ≈▲1.8% | ≈▲2.4 | ▼39.1% | - | ▼28% | ▼1.6% | ||

| n-butanol 2.5% | Four cylinders SI engine operating at different loads and speeds (3000–5000 RPM). | - | ≈▼7.2% | ≈▼4.8% | - | ≈▼16% | ≈▼10.3% | [49] |

| n-butanol 5% | - | ≈▼1% | ≈▼7.8% | - | ≈▼25% | ≈▼3.9% | ||

| n-butanol 7.5% | - | ≈▲5% | ≈▼8% | - | ≈▼15% | ≈▲13.5% |

Not only have the effects of blending butanol with gasoline been extensively researched, but investigations on butanol–diesel–biodiesel blends have also been conducted. The literature presents diverse results regarding engine performance; however, it has been proven that butanol blending leads to a reduction in the emissions of PM, CO, CO2, NOx, and other compounds. Zhang and Balasubramanian [50] evaluated the effects of mixing n-butanol at 5%, 10%, and 15% v/v with 20% palm oil methyl ester blended with ultralow sulfur diesel fuel mixed with B20. The findings indicated an increase in BTE at medium and high engine loads, while BSFC increased across all scenarios. The inclusion of n-butanol led to decreased emissions of PM2.5 and PAHs, which are known for their carcinogenic and cytotoxic properties. These favorable results could be associated with the high oxygen content present in n-butanol. In a study by Xiao et al. [51] focusing on iso-butanol/biodiesel blends, an augmentation in BSFC and BTE was observed, indicating improved evaporation and atomization performance. However, iso-butanol blending was found to increase NOx and HC emissions, albeit with varying impacts depending on engine loads. This is due to the higher biodiesel content compared to diesel and the elevated combustion temperatures. At low loads, the behavior was different, with reductions in NOx emissions directly proportional to the concentration of iso-butanol in the blends. This occurs because at lower loads, the in-cylinder temperature is lower, promoting incomplete combustion and thereby reducing NOx emissions. A similar trend is observed in HC emissions, primarily because the cetane number of the blends decreases as the iso-butanol concentration in the biodiesel increases. The combustion performance and gas emissions have been evaluated not only based on engine load, but also in relation to torque. Thakkar et al. [52] investigated an innovative ternary mixture of petro-diesel, castor oil methyl ester, and n-butanol, analyzing its effects on combustion, performance, and emission concentrations. The results showed a higher BTE at torques between 5 and 10 Nm, attributed to butanol’s favorable properties, such as lower density and viscosity, which enhance atomization and improve combustion efficiency. However, a blend of 10% biodiesel and 20% butanol (B10Bu20) significantly reduced BTE at torques above 20 Nm, primarily due to the lower cetane number and calorific value of the fuel. Low n-butanol blend ratios (<15%) led to reduced CO emissions, while higher blend ratios resulted in increased CO concentrations due to lower combustion temperatures, consequently decreasing NOx emissions. The study concluded that the best results were obtained with a blend of 15% biodiesel and 15% n-butanol (B15Bu15), and using more than 15% butanol in diesel engines could adversely affect engine performance. Overall, the effects of butanol on diesel engines depend on various factors, including engine load, heat value, cetane number, cooling effect, torque, and biodiesel source. Table 3 shows some impacts on combustion and emissions related to butanol isomers. However, the consensus in the literature suggests that butanol improves performance and emissions characteristics due to its beneficial oxygenation and physicochemical properties [53].

Table 3.

Comparison of butanol isomers and their combustion efficiency, emissions, and application in engines [54].

In addition, it is worth noting that the biological process employed for biobutanol production also yields acetone and ethanol as byproducts. Consequently, prior to utilizing biobutanol, it must undergo separation and purification procedures to isolate it from the other fermentation byproducts. This necessity for separation and purification entails the application of specialized techniques. An alternative approach involves using a blend of the three solvents, acetone, butanol, and ethanol (ABE), as an additive for conventional fossil fuels, especially gasoline. Dinesha et al. [55] carried out a study investigating the impact of ABE–gasoline blends on a SI engine, considering varying blend percentages and engine speeds. They observed significant reductions of 51% and 14% in CO and HC emissions, respectively, for the ABE10 blend at 2000 rpm, while no substantial differences in BTE were noted, although NOx emissions were shown to be 40% higher under the same conditions. However, the blends used in this study are synthetic and do not originate from an ABE fermentation process, followed by solvent separation and purification. One of the most common issues in ABE recovery is the formation of heterogeneous azeotropes between water and butanol, typically occurring at temperatures of 91.7–92.4 °C with a water content of 38 wt%. This makes separation challenging, and the presence of water in the final fuel can reduce its calorific value and combustion efficiency. Limited research has been conducted to evaluate emissions and performance characteristics using non-synthetic ABE blends, indicating that this approach requires more exhaustive investigation [56].

Additionally, certain strains of solventogenic bacteria can also produce IBE [57]. Guo et al. [58] conducted a comparative experiment to evaluate the combustion performance and emissions of SI engines using ABE, IBE, and n-butanol blends with gasoline. Their findings revealed that IBE blends exhibited the best results in terms of BTE, achieving values 2.5% higher than those of pure gasoline port injections, particularly at an 80% direct injection ratio. IBE blends also demonstrated improved power performance, while ABE blends exhibited reduced particulate matter emissions. Therefore, the direct utilization of ABE and IBE in internal combustion engines shows promise as a potential solution to overcome the drawbacks associated with the recovery process. Although numerous investigations have been carried out in this area with promising results, they are still in the early stages. Veza et al. [59] provided a comprehensive review of the primary findings on the use of ABE in gasoline and diesel engines, encompassing its impacts on performance, combustion, and emissions.

In recent decades, numerous countries, including the United States, Canada, Sweden, India, Australia, Thailand, China, Peru, Paraguay, and Brazil, have enacted legislation mandating the blending of alcohols, predominantly ethanol, with gasoline and diesel. These laws permit ethanol blends of up to 15% without requiring any modifications to conventional engines [60]. However, a key advantage of butanol, in comparison to ethanol, lies in its ability to be blended with gasoline at higher concentrations, reaching up to 85%. This is primarily due to its lower vapor pressure [61]. Furthermore, it is possible to directly supply and store butanol using existing gasoline pipelines, providing additional logistical convenience [62].

Finally, it is important to note that, in terms of ecological footprints, it is difficult to establish a comparison, as the overall carbon and water footprints depend on the feedstock selected, pretreatments, and separation techniques for each case [63]. According to the EPA [64], 2.35 kg of CO2eq is produced when 1 L of gasoline is burned. Using the energy density shown in Table 1, it is possible to calculate the emissions per unit of energy, resulting in 73.43 g CO2eq MJ−1 for gasoline. For corn and lignocellulosic ethanol, this value is +51.4 g CO2eq MJ−1 [65] and + 28–44 g CO2eq MJ−1 [66], respectively. These results are estimated considering the different emissions during the overall process of gasoline and bioethanol production, from feedstock selection and transportation to the final product supply [63]. That is the reason why lignocellulosic bioethanol proves to be more sustainable in terms of carbon emissions. Both corn ethanol and lignocellulosic ethanol produce lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions compared to gasoline. For biobutanol, the results for corn-derived biobutanol range from +79 g CO2eq MJ−1 to +122 g CO2eq MJ−1, while for sugarcane-derived biobutanol, they range from −55 g CO2eq MJ−1 to +18 g CO2eq MJ−1 [67]. It is noted that sugarcane butanol represents much lower GHG emissions compared to sugarcane biobutanol, despite being a first-generation biofuel. This is because sugarcane processing generates bagasse, which is usable for energy to support butanol production, enabling energy self-sufficiency and potential electricity export. In contrast, corn processing yields Dried Distillers Grains with Solubles (DDGS), used as animal feed, making the corn plant reliant on external energy. On the other hand, corn biobutanol requires more energy for pretreatment steps since starch needs to be converted to sugars before ABE fermentation [67]. Then, although both corn and sugarcane biobutanol are biofuels from renewable sources, the first generates GHG emissions similar to gasoline. Therefore, even considering all the advantages in terms of combustion performance, biofuels can still have a carbon footprint equal to or higher than conventional fossil fuels. For lignocellulosic biobutanol, there is limited information in the literature. Levasseur et al. [68] estimated the GHG emission of biobutanol from a Kraft dissolving pulp mill at ≈72–113 g CO2eq MJ−1. This indicates that, regardless of whether biobutanol is produced from cellulosic or starchy feedstocks, it does not necessarily mean that the overall CO2eq emissions will be lower than those of gasoline. More investigation is required in this respect to properly compare GHG emissions of biobutanol to other biofuels.

Regarding the water footprint, the situation differs. King and Webber [69], along with Scown et al. [70], documented that the water footprint required to produce gasoline from conventional petroleum sources is approximately 13 L per liter (L H2O/L) of gasoline. Referring to the data presented in Table 1, a water footprint in terms of MJ can be calculated, resulting in 416 H2O/MJ for gasoline. For biobutanol derived from wheat straw, corn grain, corn stover, and pine, the water footprints are 271, 108, 240 [71], and 145.96 [72] L H2O/MJ, respectively, which are significantly lower than that of gasoline. Similar results are reported for lignocellulosic ethanol, with a range of 72–120 H2O/MJ [66]. Typically, water footprint calculations involve breaking down the entire process, from raw material extraction to final product transport, and estimating water requirements at each stage. Additionally, water usage is categorized as either direct or indirect. Direct water refers to freshwater consumed throughout the production process, while indirect water is incorporated in inputs, materials, and activities across the process. Furthermore, water is classified into three types based on origin and use: (i) green water, which is rainwater stored in the soil and absorbed by plants; (ii) blue water, encompassing groundwater and surface water; and (iii) gray water, used for pollutant removal and meeting environmental standards [73]. However, few studies address the water footprint of biobutanol, and those available typically perform comparative analyses with other biofuels, excluding conventional fossil fuels [72]. It is crucial to examine these differences to identify stages or processes with higher water consumption and to obtain quantitative metrics on the sustainability of biobutanol compared to other fuels. Therefore, even though the carbon footprints from the biobutanol and bioethanol processes may not necessarily be lower than those of conventional fossil fuels, the situation is different when it comes to water requirements, representing an advantage over gasoline.

Butanol has gained attention in recent years as an alternative biofuel, particularly in the maritime sector. Its potential as a renewable fuel is due to several characteristics that make it appealing for use in navigation. First, butanol can be produced from biomass through fermentation processes. This production from renewable resources contributes to the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions compared to traditional fossil fuels. Being biodegradable and less toxic, butanol presents significant environmental advantages, making it a more sustainable option for the maritime industry [74].

3. Brief History of Biobutanol Production

The traditional process is ABE fermentation, also called solventogenic fermentation. This was a powerful industry during the first half of 20th century, especially after 1915 when Weizmann isolated an anaerobic bacteria named Clostridium acetobutylicum, from which an efficient process for the synthesis of acetone, ethanol, and butanol was developed [75]; this had strategic importance not just in the West (United Kingdom, France and the United States), but also in Asia (Japan and Taiwan) [76]. This industry had a significant impact on World War I, because it was the most profitable supply of acetone, which was used in cordite production, and later became a process utilized worldwide for the synthesis of solvents using renewable feedstock, such as potato starch. Nevertheless, this industry went into decline in the late 1950s due to the rise of the petrochemical industry, as ABE fermentation was unable to compete because of its low yields and high operation costs [77].

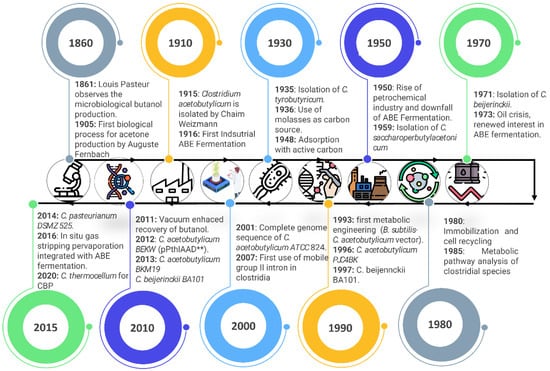

After the oil crisis in 1973, there was a global interest in reducing the dependence on fossil fuels, so fermentative processes for alcohols, especially ethanol, using renewable and agricultural resources grew significantly in countries like the United States and Brazil [78]. Consequently, at the beginning of the 2000s, ABE fermentation attracted the attention of researchers in the framework of sustainable development, as this method can be carried out using renewable sources and represents a promising opportunity to reduce the dependence on fossil fuels [79]. On the other hand, due to the current high production costs, manufacturers tend to focus on the development of chemical applications of higher economic value; for example, butanol can be used for the manufacturing of a wide range of polymers and plastics, and as solvent in paintings and chemical stabilizer [80]. Figure 1 shows the most remarkable events in biobutanol’s production history.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the most important events in biobutanol production across the last century. Adapted from [81]. The figure shows a timeline describing the most important achievements related to biological production of ABE (acetone–butanol–ethanol) throughout history. The double asterisks (**) indicate the nomenclature of the mutant strain used in the study by Jang et al. Specifically: pPthlAAD** refers to a plasmid expressing the mutated version (D485G) of the adhE1 gene, under the control of the Pthl promoter. This plasmid was introduced into a previously modified strain (BEKW), resulting in the final strain BEKW(pPthlAAD**) or BEKW**, which exhibited significantly higher butanol production efficiency.

4. Overall Biobutanol Production Process

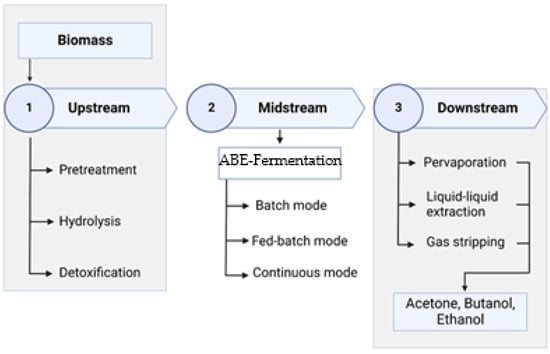

A typical biobutanol production process is based on three main stages: upstream, midstream, and downstream, as shown in Figure 2. The kind of biomass selected as feedstock determines the type of upstream process and its number of steps. Since midstream ABE fermentation requires reducing sugars and optimal conditions for bacteria such as pH, temperature, turbidity, and moisture, among others, this first stage in the biobutanol production process is focused on obtaining sugars from the biomass [82].

Figure 2.

Conventional ABE fermentation process stages. The figure shows the traditional steps for biobutanol production, which is similar to that of other byproducts obtained by fermentation.

The traditional ABE fermentation process is carried out in batch-type reactors, with initial substrate concentrations of approximately 60 gL−1. After a reaction time of between 36 and 72 h, a concentration of <20 gL−1 of solvents (acetone, butanol, and ethanol) is obtained, resulting in a productivity of between 0.5 and 0.6 gL−1h−1 and an efficiency of 0.3. These results are very low compared to the production of bioethanol, which reaches a productivity of between 2 and 3 gL−1h−1 and, in addition to that, the final concentration of the product can reach 130 gL−1 or higher [78]. These limitations are mostly due to the toxicity of microorganisms towards solvents, specifically butanol, which begins to inhibit cell activity from concentrations of 5–10 gL−1. In addition to the above, substrate pretreatments also produce hundreds of inhibitors, such as hydroxymethylfurfural and lignin derivatives, which are also toxic to bacteria. That is why recent research on this topic focuses on overcoming these barriers and turning the biological production of butanol into an economically viable industry [83]. Table 4 presents different approaches to overcome the most common hurdles for biobutanol production.

Table 4.

Drawbacks of ABE fermentation and different strategies to overcome them. Adapted from [84]. This table shows some of the most common obstacles in biobutanol production, and the approaches reported in the literature to overcome them.

4.1. Feedstock Selection for Biobutanol Production

The first substrates used in the biobutanol production process were biomasses rich in starch and sugars. At the beginning of the century, and prior to the process proposed by Weizmann, Auguste Fernbach patented a fermentation methodology to obtain acetone and butanol as a byproduct, in which he used potato starch as raw material, and which was a precursor to the traditional ABE fermentation process [80]. For his part, Weizmann found that C. acetobutylicum was able to operate successfully using rice, wheat, oats, rye, potatoes, and corn as substrate, without requiring the addition of nutrients or stimulants [85]. In the industry that followed and prevailed during the first half of the 20th century, substrates such as cassava, sugar cane and soy molasses, cheese whey, Jerusalem artichokes, liquefied corn starch, apple pulp, and algae biomass were used. During the second half of the 20th century, molasses, which were one of the most used substrates in the ABE fermentation industry, began to be used as livestock feed, increasing its value in the market. This, along with the high costs of other traditional raw materials, contributed to the decline of this industry [82].

Considering the selection of carbon sources, biobutanol production follows the same trends of other biofuels, and the raw materials for ABE fermentation can be classified in four generations. The first uses food crops, such as sugarcane, maize, and cereal grains, requiring simple pretreatment processes, obtaining higher yields and productivity, but occupying large lands for cultivation, and competing with the food industry. Starchy materials, such as cassava, potatoes, and sweet potatoes, are the most used for first-generation butanol production [86,87,88,89,90]. Beyond that, it is rare to find other kinds of first-generation feedstock for biobutanol production in the literature, with some exceptions. Niglio et al. [91] used commercial corn syrup, evaluating the individual performance of three Clostridium strains, obtaining the best results with C. saccharobutylicum, showing a titer butanol concentration of 12.46 gL−1, a yield of 0.30 g/g, and a productivity of 0.19 gL−1h−1. They also improved fermentation using a fed-batch mode.

Second-generation biobutanol utilizes non-edible biomass, which can predominantly be obtained from agricultural, forestry, and municipal residues. The advantages of using this type of raw material are its low cost and minimal impact on the food supply. However, the major challenges lie in obtaining fermentable sugars. Complex physicochemical processes are required to break down the recalcitrant structures of this biomass, and detoxification steps are necessary to remove inhibitors, which increase costs and reduce productivity [29]. Most of the research in this field focuses on lignocellulosic and hemicellulosic biomass. Wheat straw [92], rice straws [93,94,95], barley straws [96], and corn stover [97,98,99]; potato [100], orange [101], and pineapple peels [102]; and fruit pomace [103], bagasse [104], bamboo [105], palm kernel cake [106], corncob [107,108,109], and lettuce residues [110], are some of the most commonly reported substrates in the literature. Nevertheless, several studies have explored feedstocks other than lignocellulosic biomass. Ebrahimian et al. [111] utilized municipal solid waste to produce biobutanol, along with hydrogen, butanediol, ethanol, and biogas, achieving a yield of 121.9 g of butanol per kg of the biodegradable fraction of municipal solid waste. Díez et al. [112] evaluated the effect of nutrient supplements (cysteine, yeast extract, and salts) using cheese whey as a substrate, obtaining a butanol titer of 9.11 gL−1, a yield of 0.31 g of butanol per g of lactose, and a conversion rate of 49% under optimal nutritional supply conditions. Glycerol has also been employed as a biobutanol feedstock due to its high availability as a byproduct of biodiesel production through transesterification. Initial studies using this substrate yielded low butanol titers; therefore, subsequent research focused on optimizing fermentation conditions [113]. Recently, T. Chen et al. [114] utilized a novel Clostridium strain to ferment glycerol and employed an in situ membrane-coupled pervaporation process for butanol recovery, resulting in high titer concentrations of butanol (41.9 gL−1), primarily attributed to the thin polydimethylsiloxane layer used. The co-utilization of lignocellulosic and non-lignocellulosic biomass has also been investigated. Branska et al. [115] used wheat straw hydrolysates as a carbon source and chicken feathers as a nitrogen supply for bacteria. No detoxification steps were employed and the hydrolysis of both substrates was carried out simultaneously. Among the thirteen solventogenic strains tested, C. beijerinckii was able to produce a final butanol titer of 4.6 gL−1.

4.2. Upstream

As mentioned above, the trend in feedstock selection primarily focuses on lignocellulosic biomass. However, owing to its recalcitrant structure, a suitable pretreatment process is required to facilitate the biodegradation of the cell wall structure by microbes and enzymes [116]. Pretreatment steps involve the removal of lignin from biomass, thereby rendering hemicellulose and cellulose accessible for microbial attack. However, these polysaccharides remain challenging for assimilation by microorganisms. Consequently, an additional hydrolysis step is essential to break down cellulose and hemicellulose into reducing sugars before proceeding to fermentation stages [117].

The objective of pretreatment and hydrolysis is to obtain fermentable sugars from the feedstock, which can be utilized as a carbon source for microorganisms in subsequent bioprocessing steps. This is done to ensure that (i) the sugars can be assimilated by the selected strain and (ii) there is no concentration of byproducts that can inhibit microbiological activity. Generally, pretreatment can be categorized into four main types: (i) physical or mechanical treatment, such as milling, microwave, ultrasound, pyrolysis, and pulse electric field; (ii) chemical treatment, including the use of diluted or concentrated acids, ionic liquids, mild alkalis, deep eutectic solvents, organosolv, and ozonolysis; (iii) physicochemical treatment, which includes steam explosion, liquid hot water, ammonia fiber expansion (AFEX), CO2 explosion, and oxidative pretreatment; and, finally, (iv) biological treatment, which refers to the use of living organisms such as fungi, yeast, and bacteria to treat the biomass [118].

Hydrolysis is typically performed using enzymatic or acid reactions. Acid hydrolysis can easily dissolve lignin without prior chemical pretreatment. However, the byproducts of this reaction (i.e., acetic acid, formic acid, hydroxymethylfurfural, phenolic compounds, etc.) tend to be toxic to microorganisms. Enzymatic hydrolysis, on the other hand, avoids these drawbacks, but it requires different enzymes and specific conditions (pH, temperature, etc.) for each substrate due to the high specificity of enzymes. The inhibitors generated during pretreatment and hydrolysis processes can completely halt microbial activity or reduce yields and productivity. Therefore, a detoxification step is necessary to facilitate subsequent biological processes. Detoxification techniques widely reported in the literature include electrodialysis [119], evaporation [120], overliming [121] adsorption [122], and combinations thereof [123,124,125]. Table 5 summarizes some of the recent research findings on the production of biobutanol using different pretreatment and detoxification processes.

Table 5.

Comparison of pretreatment and detoxification processes in different biobutanol production studies. This table shows some research on biobutanol production, focusing on the upstream processes, specifically in pretreatment and detoxification stages.

4.3. Midstream—ABE Fermentation

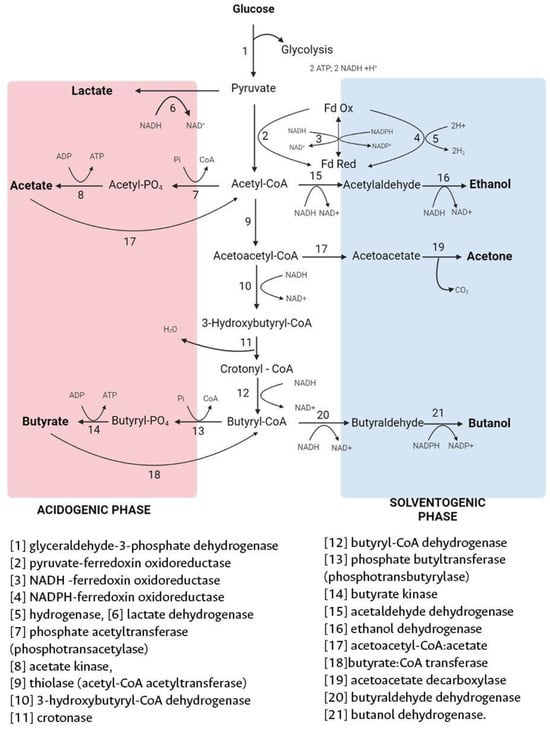

Solventogenic bacteria belonging to the Clostridium genus, including C. pasteurianum, C. acetobutylicum, and C. beijerinckii, are widely utilized for the biological synthesis of butanol. These anaerobic bacteria possess similar metabolic pathways capable of fermenting a broad range of carbon substrates, such as disaccharides (sucrose, cellobiose, lactose, etc.), pentoses (xylose and arabinose), hexoses (glucose, galactose, and fructose), and starch fuels [79]. In ABE fermentation, Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 (the most investigated organism in this respect), the same strain isolated by Weizmann in the early 20th century, predominantly produces three types of compounds: solvents (acetone, ethanol, and butanol), organic acids (acetate, lactate, and butyrate), and gases (carbon dioxide and hydrogen) [137,138]. Consequently, ABE fermentation is characterized by two distinct phases: acidogenesis and solventogenesis [137]. Figure 3 illustrates a typical metabolic pathway for solvent-producing clostridial bacteria, highlighting the sequence of metabolites and enzymes involved. During acidogenesis, the bacteria undergo exponential growth, utilizing glucose for biomass generation and producing acetic and butyric acid as byproducts. The synthesis of these acids is essential for ATP generation, which is necessary for cellular metabolism [139]. Subsequently, in the solventogenesis phase, triggered in response to the high acid concentration in the environment [78], acetate and butyrate are re-assimilated as substrates for solvent biosynthesis, leading to a cessation of bacterial growth [140]. The primary product of this stage is butanol, along with a mixture of acetone and ethanol, with a typical molar ratio of 6:3:1, respectively. The solvents affect the bacterial cell membrane, and once the concentration of butanol and other products reaches a certain level (>13 gL−1), bacterial metabolism is inhibited [139,141].

Figure 3.

Metabolic pathway for clostridial acetone–butanol–ethanol production from Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. Enzymes are marked using numbers. Adapted from [142]. This figure shows the metabolic steps of Clostridium acetobutylicum to produce solvents, and the phases of the fermentation. The enzyme used in every step is marked using numbers.

Most of the research focused on ABE fermentation uses batch mode due to its simplicity and suitability for small scale production, since it requires less maintenance and monitoring. Fed-batch and continuous fermentation processes have been also explored, and each mode represents different advantages and drawbacks. In addition to its versatility, batch mode represents a low risk of contamination and strain mutation. The fed-batch process has shown the best results for substrate inhibition, a prolonged logarithmic and stationary phase for the microorganisms, and the possibility of using concentrated substrates; however, consequently, the solvent concentration its higher, resulting in product inhibition. Thus, fed-batch mode is usually integrated with separation processes [143,144,145,146]. Continuous fermentation enhances the productivity and reduces biobutanol inhibition of the strains by removing the no-production time from the bioreactor sterilization and inoculum preparation, but it requires close process control [29]. The performance of several studies of biobutanol synthesis using various strains and fermentation methods is shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Performance of different strains for biobutanol synthesis utilizing various feedstocks and fermentation modes. This table shows some investigations of ABE fermentation, detailing the microorganisms and raw material used, the upstream processes, fermentation mode, and the solvent concentration, yield, and productivity. The abbreviations used in the table are as follows: DF: direct fermentation. DFiR: direct fermentation with in situ recovery. IBE: isopropanol–n-butanol–ethanol. SHF: separate hydrolysis and fermentation. SHFiR: separate hydrolysis and fermentation with in situ recovery. SSF: simultaneous saccharification and fermentation. SSFiR: simultaneous saccharification and fermentation with in situ recovery.

4.4. Downstream

The separation and purification of biobutanol present greater complexity and higher costs compared to the conventional downstream stages of ethanol production for several reasons. Firstly, the concentration of butanol in the fermentation broth is significantly lower, typically around 2 w/w%, in contrast to the 15 w/w% concentration of ethanol. This disparity poses challenges for efficient separation. Secondly, the boiling point of the butanol/water azeotrope is very close to that of water (93 °C vs. 100 °C) at atmospheric pressure, making distillation-based separation more difficult compared to the ethanol/water azeotrope, which has a boiling point of 78.2 °C. Lastly, the final concentration of butanol in the distilled aqueous azeotrope is only 55.5 w/w%, which is notably lower than the 95.5 w/w% concentration achieved for ethanol. These factors contribute to the increased complexity and higher costs associated with the separation and purification of biobutanol [155]. Hence, it is crucial to develop cost-effective and efficient separation or recovery techniques for biobutanol production to enhance its economic feasibility. The successful implementation of such techniques would not only address the complexities and higher costs associated with biobutanol separation and purification, but also contribute to the overall viability and competitiveness of biobutanol as a sustainable biofuel.

The ABE separation process can be categorized into four main methods: vapor-, liquid-, adsorbent-, and membrane-based techniques. Table 7 provides an overview of this classification, detailing the physicochemical principle and the advantages and disadvantages of every technique. The technologies for ABE separation were recently reviewed by Cai et al. [156].

Table 7.

Summary, advantages, and drawbacks of techniques for ABE separation. Adapted from [156]. This table shows the different processes and technologies employed for the separation and purification of solvents (acetone, butanol, and ethanol), detailing their advantages and drawbacks.

5. New Approaches and Trends for Biobutanol

5.1. Use of Microalgae as Feedstock

Microalgae consist of an extensive number of autotrophic organisms and, like starchy crops, can be used for energy valorization through direct oil recovery, and as feedstock for the production of byproducts, via the fermentation process [157]. Microalgae can grow faster than terrestrial crops due to their higher photosynthetic efficiency, and they do not compete with the food industry since they can be cultivated using ponds, seawater, and wastewater, and do not need land like conventional agriculture. Furthermore, as microalgae are photosynthetic, they can reduce CO2 emissions, and their biomass can provide valuable substrates for fermentative bacteria, such as starch, carbohydrates, and glycerol. Third-generation biofuels are those that are produced from microalgae biomass and represent a remarkable advantage, since they address the conversion of atmospheric CO2 to energy carriers [158]. The use of this raw material presents significant advantages, such as the high growth rate of algae, high oil content, the substantial incorporation of atmospheric CO2 into algal biomass during the cultivation stage, the possibility of using typically unproductive water sources such as saline or wastewater, and minimal land requirements [159]. Although third-generation biomasses have chemical compositions similar to those of first-generation biomasses, it is important to emphasize that this classification of liquid biofuels is primarily based on the origin of raw materials. Therefore, the fact that algal biomass is non-edible and does not compete with the food industry gives biofuels produced from it their own category, separate from those derived from energy crops or lignocellulosic biomasses [160,161]. Several species can be chosen for biofuel production; nevertheless, the desirability of each one depends on the starch, lignin, hemicellulose, and the convertible sugars from the cell wall [162]. Onay [163] reviewed the novel studies of biobutanol from microalgae. Finally, the term fourth-generation biofuel is used by several researchers for various types of biofuels or their production technologies, which includes fuels obtained from genetically modified algae, photobiological solar fuels, and electrofuels [164]. For biobutanol, there is little investigation using fourth-generation feedstock, and most of it focuses on the use of micro- and macroalgae biomass as a raw material [165].

Various algal species have been investigated for their potential in biobutanol production. Microalgae, including Chlorella [166,167,168], Neochloris [169], and Nannochloropsis [170], have demonstrated high lipid content, making them suitable candidates for biobutanol production. Efficient pretreatment methods are required to disrupt the rigid algal cell wall structure, thus facilitating the acquisition of fermentable sugars or lipids. Various physical, chemical, and biological pretreatment techniques, including thermal, mechanical, enzymatic, and acid/alkali treatments, have been employed to improve the accessibility of algal biomass for subsequent hydrolysis [171]. Table 8 shows some research on ABE fermentation using algal biomass.

The possibility of employing microalgae for biofuel synthesis is hindered by various barriers, necessitating more research in genetic engineering to optimize productivity and develop favorable strains. Out of 40,000 microalgae species, only 3000 have shown biofuel potential. Manipulating photon conversion efficiencies can reduce land requirements and fuel production costs. To facilitate genetic manipulation, expressed sequence tag (EST) databases containing nuclear, mitochondrial, and chloroplast genome data have been established. These databases serve as a window for introducing genetic modifications that enhance biofuel traits in algae. Consequently, more than 30 strains have been successfully genetically transformed using such constructions [172].

Table 8.

Some studies on biobutanol production using algal biomass. This table shows the results of some studies that used algal biomass to produce biobutanol, describing the algae strain, mode of fermentation, and the titer concentration obtained.

Table 8.

Some studies on biobutanol production using algal biomass. This table shows the results of some studies that used algal biomass to produce biobutanol, describing the algae strain, mode of fermentation, and the titer concentration obtained.

| Strain Used for ABE Fermentation | Microalgae Species as Substrate | Type of Pretreatment | Titer Concentration of Butanol gL−1 | ABE Concentration (gL−1) | Source |

| C. acetobutylicum | Chlorella vulgaris JSC-6 | Alkali/acidic treatment with H2SO4 and NaOH | 13.1 | 19.9 | [168] |

| C. acetobutylicum ATCC824 | Biodiesel microalgae residues (Chlorella sorokiniana CY1) | Microwave. 2% H2SO4 heated at 121 °C, 60 min, and then 2% NaOH was added, during 60 °C. | 3.9 | 6.3 | [166] |

| C. acetobutylicum ATCC824 | Chlorella sorokiniana | Dilute acid using H2SO4 at 0.5, 1.5, and 2% (w/v) at 121 °C. Enzymatic hydrolysis using α-amylase and amyloglucosidase. | 2.5 | 7.2 | [167] |

| C. acetobutylicum | Chlorococcum humicola | Dilute acid with 5% (w/v) H2SO4, and neutralization using CaCO3. | - | - | [173] |

| C. acetobutylicum ATCC824 | Neochloris aquatica | Pretreated with 1% NaOH, followed with 3% of H2SO4. | 12 | 19.6 | [169] |

| (C. acetobutylicum + C. thermocellum) a (C. beijerinckii + C. thermocellum) b | Stichococcus sp. | Milling with mortar and pestle. Soaking in 2% H2SO4. Enzymatic hydrolysis with β-glucosidase. | 7.4 a 8 b | 12.3 a 14 b | [174] |

| Not specified | Nannochloropsis gaditana | Acid treatment using H2SO4, H3PO4 and HCl (1, 2, 3, 4 and 5%). | 3 | - | [170] |

| C. acetobutylicum CGMCC1.0134 | Chlorella vulgaris | Dilute acid with 2% (v/v) H2SO4. Autoclave at 121 °C. Neutralization with NaHCO3. | 8.5 | 14.2 | [175] |

a Production from C. acetobutylicum + C. thermocellum using milling with mortar and pestle pretreatment. b Production from C. acetobutylicum + C. thermocellum using enzymatic hydrolysis with β-glucosidase.

5.2. Electron Donors in Fermentation to Enhance Butanol Productivity

To enhance yield and productivity in biobutanol production, the optimization of the production medium has been suggested. One approach is the addition of reducing agents or electron acceptors, which can improve the productivity and yield of the strain. These agents have an impact on the redox potential, ATP, and co-factors like NADH, thereby influencing the expression of specific genes. By acting as electron donors, reducing agents enable the metabolic flux towards the aimed metabolite or final product [176]. Chandgude et al. [177] evaluated the effects of ascorbic acid, L-cystine, and dithiothreitol on ABE fermentation employing a fed-batch mode using a strain of Clostridium acetobutylicum. They observed an augmentation in NADH, butanol dehydrogenase, and ATP levels, which led to improved ABE titers and yields. For L-cysteine and dithiothreitol, the final solvent concentration was twice as high as that of the controls, achieving 24.33 and 22.98 gL−1 with solvent yields of 0.38 and 0.37 gg−1, respectively, demonstrating that addition of reducing agents enhances the utilization of the substrate (glucose), leading to better solvent production. Similar findings were obtained by Ding et al. [178], who added sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) as an electron receptor to a 7 L fermenter, using C. acetobutylicum and corn meal medium as substrate, increasing the final butanol concentration to 12.96 gL−1, which was 34,8% higher than the control.

5.3. Improving ABE Fermentation Using Co-Cultures

To overcome the hurdles in biobutanol production, a promising approach is to use Clostridium co-cultures. This involves introducing a second strain into a Clostridium culture to perform the desired functions. In nature, microbes form ecological networks and interact with each other to carry out complementary roles. Taking inspiration from these natural systems, the utilization of Clostridium co-culture has gained attention as a viable approach to facilitate complex operations that are challenging to achieve with a single strain. By distributing tasks among different microorganisms and employing the unique strengths of multiple strains, Clostridium co-culture holds the potential to significantly enhance the efficiency of biobutanol production [179].

One of the approaches used for Clostridium co-culture is the use of cellulolytic strains. In this process, the cellulolytic strain is responsible for producing reducing sugars, including glucose, from lignocellulosic biomass. These monosaccharides can then be utilized by the solventogenic bacteria for its own growth and solvent production [180]. Wen et al. [181] optimized a co-culture from C. thermocellum and C. beijerinckii to produce solvents from alkali-extracted cobs after a simple pretreatment, obtaining a butanol titer of 10.9 gL−1 and a productivity of 0.101 gL−1h−1. This study did not add butyrate to the medium, which is an important highlight, since co-cultures with some solventogenic bacteria fail to produce solvents and require butyric acid feeding to carry out solventogenesis. These co-culture techniques can use other kinds of microorganisms, not just bacteria. Tri & Kamei [182] utilized the white-rot fungus Phelbia sp. MG-60. This genre of fungi can produce ethanol from lignocellulosic biomass; then, the approach used in this study is to knock out the pyruvate decarboxylase gene to produce the KO77 transformant line. This resulted in the inhibition of ethanol fermentation, accompanied by a substantial accumulation of saccharified cellobiose and glucose from cellulose. Thus, C. saccharoperbutylacetonicum was used with the aim of producing butanol. The results show that KO77 co-culture considerably improved the solvent titer, achieving 3.2 gL−1 of butanol, compared to 2.5 gL−1 from MG-60 culture.

Another approach in Clostridium co-cultures is enhancing the oxygen tolerance of solventogenic strains [183]. For ABE fermentation, it is necessary to eliminate the oxygen present in the medium due to its toxicity to bacteria. Therefore, bubbling with inert gases, reducing agents, and complex equipment are required to guarantee anaerobiosis. Then, co-culturing aerobic organisms with Clostridium strains could be an efficient technique to remove oxygen from the medium [179]. Bacillus is popular in this respect because of its high oxygen consumption rates during the growth phase. C. acetobutylicum and C. beijerinckii were studied for a co-culture with Bacillus subtilis by Oliva et al. [184], using agave hydrolysates as substrate. They demonstrated that co-culturing increased the final butanol titer up to 8.28 gL−1 for C. acetobutylicum, which was 37% higher than one-strain ABE fermentation. Mai et al. [185] used corn mash, a starchy substrate, as feedstock for co-culturing Bacillus Cereus CGMCC 1.895 and C. beijerinckii. The B. cereus strain has amylase; thus, it could help in both hydrolyzing the corn flour and depleting the oxygen in the medium, without requiring any pretreatment for biomass. Pure C. beijerinckii ABE fermentation achieved just 1.5 gL−1 of butanol, but the co-culture increased the titer up to 10.52 and 6.78 gL−1 for solvents and butanol, respectively. Furthermore, by analyzing the behavior of dissolved oxygen levels, it was shown that the presence of B. cereus led to the consumption of oxygen in the broth, resulting in the required anaerobic environment for C. beijerinckii. In addition to Bacillus, other microorganisms have been used for co-culturing with clostridium, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae [86], Nesterenkonia sp. [186,187], and Caldibacillus debilis [188].

In addition to feedstock cost and oxygen tolerance, co-cultures can also approach the problem of low butanol titer and yield of ABE fermentation. Increased solvent production can be achieved by the addition of a partner strain [179]. For example, Saccharomyces cerevisiae have the capacity to secrete secondary metabolites such as amino acids and organic acids under stress conditions, such as high temperature, and hypertonic conditions [189]. Research has demonstrated that certain species of anaerobic bacteria can utilize amino acids as a primary source of energy. This can promote microbial metabolism and enhance the yield of byproducts [190]. Wu et at. [191] studied the effect of addition of S. cerevisiae on ABE fermentation using a butanol-resistant C. beijerinckii strain. The results showed an augmentation in final butanol titer and productivity, which were 203% and 155% compared to the monoculture control. Moreover, quantification of amino acids conducted throughout fermentation revealed that the addition of yeast at optimal levels can enhance butanol manufacturing by intensifying the accumulation of aspartic and aromatic acids. Luo et al. [192] demonstrated that butyrate re-assimilation and butanol tolerance could be enhanced by adding certain amino acids. They also utilized a C. acetobutylicum/S. cerevisiae co-culture system, achieving high concentrations of ABE and butanol of 24.8 gL−1 and 16.3 gL−1, respectively, showing great potential for butanol production.

5.4. In Situ Recovery and Multi-Stage Separation

Although the separation techniques mentioned above have demonstrated positive results in separating ABE from dilute aqueous solutions of fermentation broth, the bacterial growth inhibition in up to 13 gL−1 is still a challenge to overcome [193]. Thus, the main approach to overcome this drawback is to integrate fermentation and separation processes, utilizing integrated stages to extract solvents and concentrate them. Table 9 shows some investigations reported in the literature in this respect.

In addition to what is shown in Table 9, there are other emerging technologies for biobutanol separation and purification, for example, dividing-wall columns (DWCs), which are distillation columns that consolidate the functions of two conventional columns within a single shell. The separation of a three-component (or more) mixture into its individual constituents is facilitated by incorporating a vertical wall in the middle of the column [194]. For biobutanol, Patraşcu et al. [195] proposed a novel heat pump-assisted azeotropic dividing-wall column for solvent separation. The process was simulated using Aspen Plus, and the results demonstrated that this approach could achieve a 60% energy saving compared to conventional separation techniques. Additionally, despite the higher costs associated with the addition of a compressor, the payback period is only 10 months, making it economically feasible and sustainable.

Table 9.

Performance of in situ recovery and multi-stage methods for solvent separation. This table shows some investigations that used in situ recovery or multi-stage methods for solvent extraction and purification following ABE fermentation. The concentration of solvents before and after the process are detailed. The nomenclature of the table is detailed as follows: a: ABE (acetone–butanol–ethanol). b: Butanol. c: IBE (Isopropanol-n-butanol-ethanol).

Table 9.

Performance of in situ recovery and multi-stage methods for solvent separation. This table shows some investigations that used in situ recovery or multi-stage methods for solvent extraction and purification following ABE fermentation. The concentration of solvents before and after the process are detailed. The nomenclature of the table is detailed as follows: a: ABE (acetone–butanol–ethanol). b: Butanol. c: IBE (Isopropanol-n-butanol-ethanol).

| Fermentation Operation Mode | Separation Technique | Approach | Solvent in the Reactor (gL−1) | Concentrated Solvent (gL−1) | References |

| Solvents of laboratory grade were used. | Gas stripping–condensation | The ABE recovery system integrates gas stripping and a two-stage condensation process, incorporating an absorption section aiming the recovery of butanol. | 20 a 13 b | 204 a 113 b | [196] |

| Fed-batch | In situ extraction–gas stripping | Oleyl acid is used for liquid–liquid extraction in the medium. Then, butanol is continuously removed by nitrogen stripping. The productivity of ABE fermentation is enhanced. | - ≈20 b | 109.4 a 63.8 b | [197] |

| Batch | - - | 360–460 a 200–250 b | |||

| Immobilized fed-batch | Gas stripping–pervaporation | An immobilized bioreactor is connected to a condenser to recycle its vapor phase. After an initial fermentation of 30 h, the gas stripping process was initiated, and the first condensate was collected. Then, this condensate is separated by pervaporation using a hydrophobic polydimethylsiloxane membrane. | ≈17–22 a 10–12 b | 177.6 a 108.3 b | [198] |

| Fed-batch | Pervaporation and salting-out | The permeate was treated and separated using salting-out after the in situ recovery of ABE by pervaporation. | - | 805.5 a 486.7 b | [199] |

| Fed-batch | Gas stripping and salting-out | Recovery of solvents from a stage of gas stripping condensate was achieved using K4P2O7 and K2HPO4. | ≈12–14 a ≈9–10 b | 747.6 a 520.3 b | [200] |

| Fed-batch fermentation with cell immobilization | Pervaporation–pervaporation | Following a first-stage pervaporation, the permeate was utilized for feeding the second-stage pervaporation, which used hydrophilic and hydrophobic membranes in this study. The permeate obtained from the second stage was collected. | ≈20–23 a 8.9 b | 671.1 a 515.3 b | [201] |

| Batch | Gas stripping–pervaporation | Butanol was continuously extracted from the fermentation broth using gas stripping, followed by further concentration of the extracted butanol through pervaporation. | ≈16.5 c ≈10 b | 712.4 c 558.9 b | [202] |

| An aqueous butanol solution, close to the current tolerance limit for biofuel microbes. | Membrane vapor extraction | In membrane vapor extraction, the feed and solvent liquids remain unconnected, separated by vapor. A semi-volatile aqueous solute (butanol) undergoes vaporization at the upstream side of a membrane. It then diffuses as a vapor through the membrane pores, subsequently condensing and dissolving into a high-boiling nonpolar solvent that is favorable to the solute but not to water. | 20 b | 970 b | [203] |

a ABE, b Butanol, c IBE.

6. Conclusions

Biobutanol possesses significant potential in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and contributing to renewable solutions. Research in the discipline of the environment and energy alternatives is crucial, as these domains are closely intertwined and essential for addressing humanity’s needs. Biorefineries provide a remarkable alternative for producing environmentally friendly fuels from low-cost biomass that are plentifully available and can be processed with lower energy requirements and contamination. Lignocellulosic materials play an essential role in achieving carbon neutrality in the biofuel sectors. ABE fermentation, which emerged as a significant industry in the 20th century, is now advancing with novel methods and technologies, focusing on isolating and developing new strains capable of yielding higher production and exhibiting resistance to toxic compounds and fermentation conditions. By researching novel pretreatment processes for the efficient removal of lignocellulose, together with conversion of second-generation substrates into biobutanol and enhancing biofuel quality, biorefinery approaches have the potential to become promising pathways for achieving carbon neutrality in fuel generation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A.S.-E. and C.A.G.-F.; methodology, V.A.S.-E.; software, V.A.S.-E. and K.T.C.-T.; validation, C.A.G.-F. and K.T.C.-T.; formal analysis, V.A.S.-E. and K.T.C.-T.; investigation, K.T.C.-T. and V.A.S.-E.; resources, C.A.G.-F.; data curation, C.A.G.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A.S.-E.; writing—review and editing, V.A.S.-E.; visualization, V.A.S.-E. and K.T.C.-T.; supervision, C.A.G.-F.; project administration, C.A.G.-F.; funding acquisition, C.A.G.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MINCIENCIAS with the financial funds approved by the project titled “Implementation of a hydrothermal biorefinery to produce chemical products with high added value, using residual biomass from agro-industrial processes, in an intersectoral alliance (academy-industry)”, Call 914. Contract 101-2022, code 1101-914-91642.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| ABE | Acetone–butanol–ethanol |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BSFC | Brake specific fuel consumption |

| BTE | Brake thermal efficiency |

| CO | Carbon monoxide |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| DF | Direct fermentation |

| DFiR | Direct fermentation with in situ recovery |

| FAME | Fatty acid methyl ester |

| H2O | Water |

| HC | Hydrocarbons |

| IBE | Isopropanol–n-butanol–ethanol |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| NOX | Nitrogen oxides |

| PAH | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| RPM | Revolutions per minute |

| SHF | Separate hydrolysis and fermentation |

| SHFiR | Separate hydrolysis and fermentation with in situ recovery |

| SSF | Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation |

| SSFiR | Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation with in situ recovery |

References

- IHS Markit. Integrated Intelligence for the Biofuels Sector Including Market Reporting, Price Assessment, Trends Analysis, and Medium to Long-Term Fundamentals-Based Forecasting Across the Biofuels Value Chain. Available online: https://ihsmarkit.com/products/biofuels.html?utm_source=google&utm_medium=ppc&utm_campaign=PC021957&utm_term=biodieseloutlook&utm_network=g&device=c&matchtype=b (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- IEA. Biofuels. Low-Emission Fuels. Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/low-emission-fuels/biofuels (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Ward, V.C.A. Biofuels. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Godoy, L.; Barrera-Martínez, I.; Ayala-Mendivil, N.; Aguilar-Juárez, O.; Arellano-García, L.; Reyes, A.L.; Méndez-Zamora, A.; Sandoval, G. Biofuels. In Biobased Products and Industries; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 125–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Mishra, K.; Srivastava, M.; Srivastava, K.R.; Gupta, V.K.; Ramteke, P.W.; Mishra, P.K. Role of Compositional Analysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Efficient Biofuel Production. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Abdelaziz, O.Y.; Hulteberg, C.P.; Riisager, A. New synthetic approaches to biofuels from lignocellulosic biomass. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 21, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Nelson, E.; Tilman, D.; Polasky, S.; Tiffany, D. Environmental, economic, and energetic costs and benefits of biodiesel and ethanol biofuels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11206–11210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandel, A.K.; Singh, O.V. Weedy lignocellulosic feedstock and microbial metabolic engineering: Advancing the generation of ‘Biofuel’. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 89, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, R.; Gupta, A.; Pant, G.; Chaubey, K.K.; Kumar, G.; Patrick, N. Second-generation biofuels: Facts and future. In Relationship Between Microbes and the Environment for Sustainable Ecosystem Services; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 3, pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of Council of 23 April 2009 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources and Amending and Subsequently Repealing Directives 2001/77/EC and 2003/30/EC. 2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32009L0028 (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Sánchez, J.; Curt, M.D.; Robert, N.; Fernández, J. Biomass Resources. In The Role of Bioenergy in the Bioeconomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 25–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlat, N.; Fahl, F.; Dallemand, J.-F. Status and Opportunities for Energy Recovery from Municipal Solid Waste in Europe. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 2425–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situmorang, Y.A.; Guan, G. Power Production from Biomass. In Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loha, C.; Karmakar, M.K.; Chattopadhyay, H.; Majumdar, G. Renewable Biomass: A Candidate for Mitigating Global Warming. In Encyclopedia of Renewable and Sustainable Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.; Islam, M.A.; Mishra, P.; Yousuf, A.; Faizal, C.K.M.; Khan, M.M.R. Technical difficulties of mixed culture driven waste biomass-based biohydrogen production: Sustainability of current pretreatment techniques and future prospective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.T.; Thanarasu, A.; Kumar, P.S.; Periyasamy, K.; Raghunandhakumar, S.; Periyaraman, P.; Devaraj, K.; Dhanasekaran, A.; Subramanian, S. Potential pre-treatment of lignocellulosic biomass for the enhancement of biomethane production through anaerobic digestion—A review. Fuel 2022, 318, 123593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J.R. Biomass gasification as an industrial process with effective proof-of-concept: A comprehensive review on technologies, processes and future developments. Results Eng. 2022, 14, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, B.; Luo, L.; Zhang, F.; Yi, Y.; Shan, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Lü, X. A review on recycling techniques for bioethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 149, 111370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, A.; Goswami, S.; Sultana, A.; Katiyar, N.K.; Athar, M.; Dubey, L.; Goswami, L.; Hussain, C.M.; Kareem, M.A. Waste biomass to biobutanol: Recent trends and advancements. In Waste-to-Energy Approaches Towards Zero Waste; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 393–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekman, S.K. Biofuels in the U.S.—Challenges and Opportunities. Renew Energy 2009, 34, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S.H.; Abdulla, R.; Jambo, S.A.; Marbawi, H.; Gansau, J.A.; Faik, A.A.; Rodrigues, K.F. Yeasts in sustainable bioethanol production: A review. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2017, 10, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Sahu, S.K.; Panda, A.K. Current status and prospects of alternate liquid transportation fuels in compression ignition engines: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwer, R.; Pasupuleti, S.R.; Bhurat, S.S.; Gugulothu, S.K.; Rathore, N. Blending of ethanol with gasoline and diesel fuel—A review. Mater. Today Proc. Oct. 2022, 69, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, P.; Subramanian, K.A.; Mathai, R. Experimental study on unregulated emission characteristics of a two-wheeler with ethanol-gasoline blends (E0 to E50). Fuel 2020, 262, 116504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Dubey, A. Biobutanol: An Alternative Biofuel. In Advances in Biofeedstocks and Biofuels; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D. Bio-butanol as a new generation of clean alternative fuel for SI (spark ignition) and CI (compression ignition) engines. Renew Energy 2020, 147, 2494–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Han, J.; Lee, J. Renewable Butanol Production via Catalytic Routes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, L. Global n-Butanol Market Volume 2015–2029. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1245211/n-butanol-market-volume-worldwide/ (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Karthick, C.; Nanthagopal, K. A comprehensive review on ecological approaches of waste to wealth strategies for production of sustainable biobutanol and its suitability in automotive applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 239, 114219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Wu, R.; Sui, Y.; Chen, C.; Xin, F.; Zhou, J.; Dong, W.; Jiang, M. Current status and perspectives on biobutanol production using lignocellulosic feedstocks. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 7, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.C.; Suryawanshi, P.G.; Kataki, R.; Goud, V.V. Current challenges and advances in butanol production. In Sustainable Bioenergy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 225–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]