An Update on Experimental Therapeutic Strategies for Thin Endometrium

Abstract

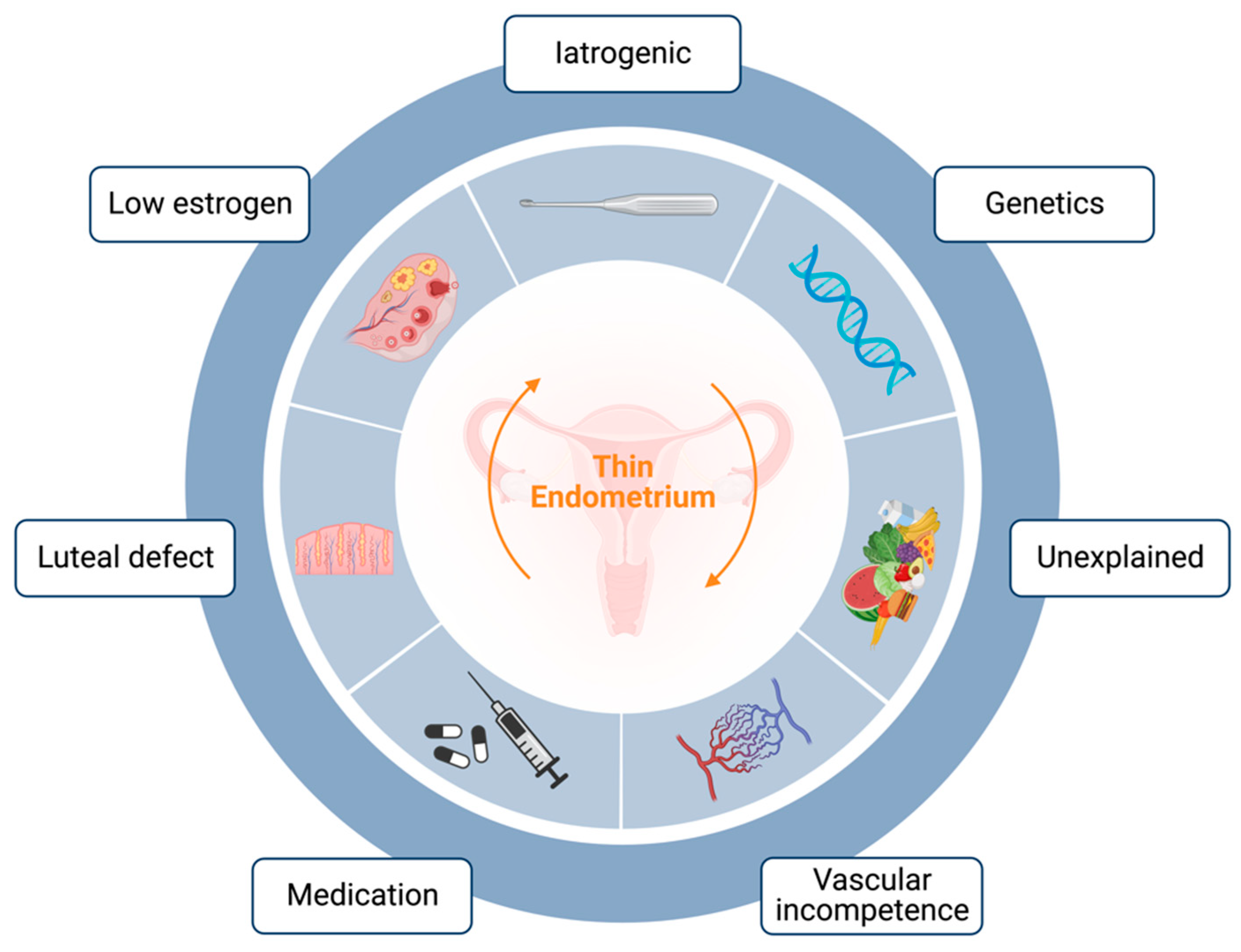

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Therapeutic Strategies

2.1. Platelet-Rich Plasma

2.2. Stem Cell Therapy

2.2.1. BMDSCs

2.2.2. ADSCs

2.2.3. UCMSCs

2.2.4. Other Stem Cell Sources

2.2.5. Stem-Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

| Reference | Cell Source | Study Design | Administration Protocol | Control Group (n) | Intervention Group (n) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nagori et al., 2011 [47] | Autologous BMDSCs | Case report | 0.7 mL BMDSCs infusion on cd2 | / | 1 | OP at 8th week of pregnancy |

| Zhao et al., 2013 [48] | Autologous BMDSCs | Case report | 1 × 107 BMDSCs infusion following hysteroscopic adhesion lysis | / | 1 | Spontaneous pregnancy after 3 months |

| Singh et al., 2014 [49] | Autologous BMDSCs | Prospective case series | 3 mL SVF sub-endometrial injection. After the exclusion of other causes of secondary amenorrhea | / | 6 | EMT increased, resume of menstruation in 5 patients |

| Santamaria et al., 2016 [50] | Autologous CD133+ BMDSCs | Prospective case series | 15 mL of saline suspension with selected CD133+ cells infusion; BMDSC delivered into the spiral arterioles via catheterization | / | 18 | EMT increased; 3 spontaneous pregnancies, 7 pregnancies after 14 EMT |

| Tan et al., 2016 [64] | Autologous MenSCs | Prospective case series | Instillation of 0.5 mL MenSCs suspension on cd16 | / | 7 | EMT increased; 2/4 CP; one spontaneous pregnancy after the second MenSCs transplantation |

| Cao et al., 2018 [62] | UC-MSCs | Prospective case series | 1 × 107 UC-MSCs on collagen scaffold following hysteroscopic adhesion lysis | / | 26 | EMT increased; improvement in endometrial proliferation, differentiation, and neovascularization; 10/26 CP, 8/10 LB |

| Sudoma et al., 2019 [57] | Autologous ADSCs | Prospective case series | A sub-endometrial injection every 5–7 days 3 times | / | 25 | EMT increased; 13/25 pregnancies, 9/25 live births |

| Lee et al., 2020 [58] | Autologous adipose-derived cells | Prospective case series | Transcervical instillation of autologous AD-SVF from adipose tissue | / | 6 | EMT increased; resume of menstruation in 2/5 patients, 1/5 pregnancies after EMT |

| Zhang et al., 2021 [63] | UC-MSCs | Self-controlled prospective study | A suspension of 1 × 107/mL (2 mL) UC-MSCs on collagen scaffolds, transplanted into the uterine cavity | / | 16 | Average EMT increased (p< 0.001); 3/15 CP, 2/3 LB |

2.3. Tissue Bioengineering

3. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liao, Z.; Liu, C.; Cai, L.; Shen, L.; Sui, C.; Zhang, H.; Qian, K. The Effect of Endometrial Thickness on Pregnancy, Maternal, and Perinatal Outcomes of Women in Fresh Cycles after IVF/ICSI: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 12, 814648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.E.; Hartman, M.; Hartman, A.; Luo, Z.C.; Mahutte, N. The Impact of a Thin Endometrial Lining on Fresh and Frozen-Thaw IVF Outcomes: An Analysis of over 40,000 Embryo Transfers. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 1883–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eftekhar, M.; Tabibnejad, N.; Tabatabaie, A.A. The Thin Endometrium in Assisted Reproductive Technology: An Ongoing Challenge. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2018, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, E.A.; Van Voorhis, B.; Kawwass, J.F.; Kondapalli, L.A.; Liu, K.; Dokras, A. Endometrial Thickness: How Thin Is Too Thin? Fertil. Steril. 2022, 118, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyalos, R.P.; Hubert, G.D.; Shamonki, M.I. The Mystery of Optimal Endometrial Thickness…never Too Thick, but When Is Thin…too Thin? Fertil. Steril. 2022, 117, 801–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Toukhy, T.; Coomarasamy, A.; Khairy, M.; Sunkara, K.; Seed, P.; Khalaf, Y.; Braude, P. The Relationship between Endometrial Thickness and Outcome of Medicated Frozen Embryo Replacement Cycles. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 89, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Le, A.W. A Study on the Estrogen Receptor α Gene Polymorphism and Its Expression in Thin Endometrium of Unknown Etiology. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2012, 74, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.W.; Wang, Z.H.; Yuan, R.; Shan, L.L.; Xiao, T.H.; Zhuo, R.; Shen, Y. Association of the Estrogen Receptor-β Gene RsaI and AluI Polymorphisms with Human Idiopathic Thin Endometrium. Genet. Mol. Res. 2013, 12, 5978–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, N.; Bentov, Y.; Chang, P.T.; Esfandiari, N.; Nazemian, Z.; Casper, R.F. Effect of Long-Term Combined Oral Contraceptive Pill Use on Endometrial Thickness. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 120, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonen, Y.; Casper, R.F. Sonographic Determination of a Possible Adverse Effect of Clomiphene Citrate on Endometrial Growth. Hum. Reprod. 1990, 5, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, R.F. It’s Time to Pay Attention to the Endometrium. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, 519–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Zhao, G.; Jiang, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Yao, S.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, D.; Deng, W.; et al. Deciphering the Endometrial Niche of Human Thin Endometrium at Single-Cell Resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2115912119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Fan, Y.; Wang, J.; Shi, R. Dysfunctional intercellular communication and metabolic signaling pathways in thin endometrium. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1050690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanyan, E.; Tsaturova, K.; Devyatova, E. Thin endometrium problem in IVF programs. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2020, 36, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Wu, M.; He, R.; Ye, Y.; Sun, X. Administration of growth hormone improves endometrial function in women undergoing in vitro fertilization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2022, 28, 838–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.L.; Xu, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhang, X.Y.; Li, D.D.; Zheng, L.W. Efficacy of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for infertility undergoing IVF: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2023, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, S.; Wei, C.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Shen, X.; Lin, X. Intrauterine administration of G-CSF for promoting endometrial growth after hysteroscopic adhesiolysis: A randomized controlled trial. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 37, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Luan, T.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, M.; Dong, L.; Su, Y.; Ling, X. Effect of sildenafil citrate on treatment of infertility in women with a thin endometrium: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060520969584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranisavljevic, N.; Raad, J.; Anahory, T.; Grynberg, M.; Sonigo, C. Embryo transfer strategy and therapeutic options in infertile patients with thin endometrium: A systematic review. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 2217–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.E.; Hartman, M.; Hartman, A. Management of Thin Endometrium in Assisted Reproduction: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2019, 39, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebovitz, O.; Orvieto, R. REVIEW—Treating Patients with “Thin” Endometrium-an Ongoing Challenge. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2014, 30, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharibeh, N.; Aghebati-Maleki, L.; Madani, J.; Pourakbari, R.; Yousefi, M.; Ahmadian Heris, J. Cell-Based Therapy in Thin Endometrium and Asherman Syndrome. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, X.J.N.; Fei, Y.Y.; Han, H.T.; Xu, J.; Cheng, L.; Li, X. Stem Cell Therapy in Liver Regeneration: Focus on Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 232, 108004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konen, F.F.; Schwenkenbecher, P.; Jendretzky, K.F.; Gingele, S.; Grote-Levi, L.; Möhn, N.; Sühs, K.W.; Eiz-Vesper, B.; Maecker-Kolhoff, B.; Trebst, C.; et al. Stem Cell Therapy in Neuroimmunological Diseases and Its Potential Neuroimmunological Complications. Cells 2022, 11, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.I.-K.; Diaz, R.; Borg-Stein, J. Platelet-Rich Plasma. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 27, 825–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Mikich, A.; de Oliveira, R.; Frantz, N. Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapy and Reproductive Medicine. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharara, F.I.; Lelea, L.-L.L.; Rahman, S.; Klebanoff, J.S.; Moawad, G.N. Review- A Narrative Review of Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) in Reproductive Medicine. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2021, 38, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, J.; Acharya, N. Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Promising Regenerative Therapy in Gynecological Disorders. Cureus 2022, 14, e28998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Song, H.; Lyu, S.W.; Lee, W.S. Platelet-Rich Plasma Treatment in Patients with Refractory Thin Endometrium and Recurrent Implantation Failure: A Comprehensive Review. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2022, 49, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.M.; Sánchez, J.; Sánchez, W.; Vielma, V. Platelet-Rich Plasma as an Adjuvant in the Endometrial Preparation of Patients with Refractory Endometrium. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2018, 22, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftekhar, M.; Neghab, N.; Naghshineh, E.; Khani, P. Can Autologous Platelet Rich Plasma Expand Endometrial Thickness and Improve Pregnancy Rate during Frozen-Thawed Embryo Transfer Cycle? A Randomized Clinical Trial. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 57, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, L.-N.N.; Pang, J.; Chen, J.; Liang, X. Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma Infusion Improves Clinical Pregnancy Rate in Frozen Embryo Transfer Cycles for Women with Thin Endometrium. Medicine 2019, 98, e14062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Shin, J.E.; Koo, H.S.; Kwon, H.; Choi, D.H.; Kim, J.H. Effect of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma Treatment on Refractory Thin Endometrium During the Frozen Embryo Transfer Cycle: A Pilot Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusumi, M.; Ihana, T.; Kurosawa, T.; Ohashi, Y.; Tsutsumi, O. Intrauterine Administration of Platelet-Rich Plasma Improves Embryo Implantation by Increasing the Endometrial Thickness in Women with Repeated Implantation Failure: A Single-Arm Self-Controlled Trial. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2020, 19, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, S.J.; Kwok, Y.S.S.; Nguyen, T.T.T.N.; Librach, C. Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma Improves the Endometrial Thickness and Live Birth Rate in Patients with Recurrent Implantation Failure and Thin Endometrium. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, M.; Mettler, L.; Jain, S.; Meshram, S.; Günther, V.; Alkatout, I. Management of a Thin Endometrium by Hysteroscopic Instillation of Platelet-Rich Plasma Into The Endomyometrial Junction: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, Y.; Singh, N.; Vanamail, P. Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma Optimizes Endometrial Thickness and Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Refractory Thin Endometrium of Varied Aetiology during Fresh and Frozen-Thawed Embryo Transfer Cycles. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2022, 26, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangaraju, B.; Mahajan, P.; Subramanian, S.; Kulkarni, A.; Mahajan, S. Lyophilized Platelet–Rich Plasma for the Management of Thin Endometrium and Facilitation of in-Vitro Fertilization. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2022, 27, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, N.; Ferreira, M.; Kulmann, M.I.; Frantz, G.; Bos-Mikich, A.; Oliveira, R. Platelet-Rich plasma as an effective alternative approach for improving endometrial receptivity—A clinical retrospective study. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2020, 24, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Qi, J.; Sun, Y. Platelet-Rich Plasma as a Potential New Strategy in the Endometrium Treatment in Assisted Reproductive Technology. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 707584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESHRE Working Group on Recurrent Implantation Failure; Cimadomo, D.; de los Santos, M.J.; Griesinger, G.; Lainas, G.; Le Clef, N.; McLernon, D.J.; Montjean, D.; Toth, B.; Vermeulen, N.; et al. ESHRE good practice recommendations on recurrent implantation failure. Hum. Reprod. Open 2023, 2023, hoad023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouhayar, Y.; Sharara, F.I. G-CSF and Stem Cell Therapy for the Treatment of Refractory Thin Lining in Assisted Reproductive Technology. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2017, 34, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyhanvar, N.; Zarghami, N.; Bleisinger, N.; Hajipour, H.; Fattahi, A.; Nouri, M.; Dittrich, R. Cell-Based Endometrial Regeneration: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.Y.; Sun, X.; Pan, H.X.; Wang, L.; He, C.Q.; Wei, Q. Cell Transplantation Therapies for Spinal Cord Injury Focusing on Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Advances and Challenges. World J. Stem Cells 2023, 15, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Jalil, F.; Jaleel, H.; Ghafoor, F. Bone Marrow Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis—A Concise Review of Past Ten Years. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 4619–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G.; George, N.P.; Hwang, J.S.; Park, S.; Kim, M.O.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, G. Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Applications in Neurodegenerative Disease Treatment and Integrated Omics Analysis for Successful Stem Cell Therapy. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagori, C.; Panchal, S.; Patel, H. Endometrial Regeneration Using Autologous Adult Stem Cells Followed by Conception by in Vitro Fertilization in a Patient of Severe Ashermans Syndrome. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2011, 4, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, A.; Tang, X.; Li, M.; Yan, L.; Shang, W.; Gao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, A.; Tang, X.; et al. Intrauterine Transplantation of Autologous Bone Marrow Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Followed by Conception in a Patient of Severe Intrauterine Adhesions. Open J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 3, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Mohanty, S.; Seth, T.; Shankar, M.; Bhaskaran, S.; Dharmendra, S. Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in Refractory Asherman’s Syndrome: A Novel Cell Based Therapy. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 7, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, X.; Cabanillas, S.; Cervelló, I.; Arbona, C.; Raga, F.; Ferro, J.; Palmero, J.; Remohí, J.; Pellicer, A.; Simón, C. Autologous Cell Therapy with CD133+ Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells for Refractory Asherman’s Syndrome and Endometrial Atrophy: A Pilot Cohort Study. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Uterine Infusion with Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improves Endometrium Thickness in a Rat Model of Thin Endometrium. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 22, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Z.; Qiong, Z.; Yonggang, W.; Yanping, L. Rat Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improve Regeneration of Thin Endometrium in Rat. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 587–594.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Huang, Z.; Lin, H.; Tian, Y.; Li, P.; Lin, S. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BMSCs) Restore Functional Endometrium in the Rat Model for Severe Asherman Syndrome. Reprod. Sci. 2019, 26, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervelló, I.; Gil-Sanchis, C.; Santamaría, X.; Cabanillas, S.; Díaz, A.; Faus, A.; Pellicer, A.; Simón, C. Human CD133(+) Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells Promote Endometrial Proliferation in a Murine Model of Asherman Syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 104, 1552–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, O.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Y. Aging and Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Therapeutic Opportunities and Challenges in the Older Group. Gerontology 2022, 68, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazini, L.; Rochette, L.; Amine, M.; Malka, G. Regenerative Capacity of Adipose Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs), Comparison with Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudoma, I.; Pylyp, L.; Kremenska, Y.; Goncharova, Y. Application of Autologous Adipose-Derived Stem Cells for Thin Endometrium Treatment in Patients with Failed ART Programs. J. Stem Cell Ther. Transplant. 2019, 3, 001–008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Shin, J.E.; Kwon, H.; Choi, D.H.; Kim, J.H. Effect of Autologous Adipose-Derived Stromal Vascular Fraction Transplantation on Endometrial Regeneration in Patients of Asherman’s Syndrome: A Pilot Study. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 27, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, F.T.; Peng, T.L.; Yu, Y.; Rong, L. Efficacy and Safety of Autologous Adipose Tissue-Derived Stromal Vascular Fraction in Patients with Thin Endometrium: A Protocol for a Single-Centre, Longitudinal, Prospective Self-Control Study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamura-Inoue, T.; He, H. Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Their Advantages and Potential Clinical Utility. World J. Stem Cells 2014, 6, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, I.; Goulielmaki, M.; Devetzi, M.; Panagiotidis, M.; Koliakos, G.; Zoumpourlis, V. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Preclinical Cancer Cytotherapy: A Systematic Review. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, X.; Tang, X.; Yan, G.; Wang, J.; Bai, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; et al. Allogeneic Cell Therapy Using Umbilical Cord MSCs on Collagen Scaffolds for Patients with Recurrent Uterine Adhesion: A Phase I Clinical Trial. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Shi, L.; Lin, X.; Zhou, F.; Xin, L.; Xu, W.; Yu, H.; Li, J.; Pan, M.; Pan, Y.; et al. Unresponsive Thin Endometrium Caused by Asherman Syndrome Treated with Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Collagen Scaffolds: A Pilot Study. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Li, P.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, D.; Xu, X.; Kong, L. Autologous Menstrual Blood-Derived Stromal Cells Transplantation for Severe Asherman’s Syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 2723–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Dai, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, S. Endometrial Stem Cells Repair Injured Endometrium and Induce Angiogenesis via AKT and ERK Pathways. Reproduction 2016, 152, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramoto, G.; Shimizu, T.; Takagi, S.; Ishitani, K.; Matsui, H.; Okano, T. Endometrial Regeneration Using Cell Sheet Transplantation Techniques in Rats Facilitates Successful Fertilization and Pregnancy. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 172–181.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, T.; Zhao, X.; Sun, H.; Li, X.; Lin, N.; Ding, L.; Dai, J.; Hu, Y. Regeneration of Uterine Horns in Rats Using Collagen Scaffolds Loaded with Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Endometrium-like Cells. Tissue Eng. Part A 2015, 21, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincela Lins, P.M.; Pirlet, E.; Szymonik, M.; Bronckaers, A.; Nelissen, I. Manufacture of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 965–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, G.G.R.; Zaidi, N.H.; Saini, R.S.; Ramirez Coronel, A.A.; Alsandook, T.; Hadi Lafta, M.; Arias-Gonzáles, J.L.; Amin, A.H.; Maaliw, R.R. The Developing Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Autoimmune Diseases: Special Attention to Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 122, 110531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhujel, B.; Oh, S.-H.; Kim, C.-M.; Yoon, Y.-J.; Kim, Y.-J.; Chung, H.-S.; Ye, E.-A.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.-Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Exosomes: A Novel Therapeutic Approach for Corneal Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabeeva, G.; Silachev, D.; Vishnyakova, P.; Asaturova, A.; Fatkhudinov, T.; Smetnik, A.; Dumanovskaya, M. The Therapeutic Potential of Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cell—Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Endometrial Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Qi, W.; Zheng, J.; Tian, Y.; Qi, X.; Kong, D.; Zhang, J.; Huang, X. Exosomes Derived from Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells Restore Functional Endometrium in a Rat Model of Intrauterine Adhesions. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 27, 1266–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, F. Exosomes Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells Reverse EMT via TGF-Β1/Smad Pathway and Promote Repair of Damaged Endometrium. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahim, N.; Mostafa, O.; El Dosoky, R.E.; Ahmed, I.A.; Saad, A.S.; Mostafa, A.; Sabry, D.; Ibrahim, K.A.; Farid, A.S. Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles/Estrogen Combined Therapy Safely Ameliorates Experimentally Induced Intrauterine Adhesions in a Female Rat Model. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Tang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, D.; Huang, J.; Lin, J. Exosomes Derived From CTF1-Modified Bone Marrow Stem Cells Promote Endometrial Regeneration and Restore Fertility. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 868734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egami, M.; Haraguchi, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Yamato, M.; Okano, T. Latest Status of the Clinical and Industrial Applications of Cell Sheet Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2014, 37, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Okano, T. Thermally-Triggered Fabrication of Cell Sheets for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 138, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Dong, S.; Ye, X.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, M.; Wang, S.; Ying, Y.; Chen, R.; et al. Synergistic Regenerative Therapy of Thin Endometrium by Human Placenta-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Encapsulated within Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lv, H.F.; Zhao, R.; Ying, M.F.; Samuriwo, A.T.; Zhao, Y.Z. Recent Developments in Bio-Scaffold Materials as Delivery Strategies for Therapeutics for Endometrium Regeneration. Mater. Today Bio 2021, 11, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shi, C.; Cai, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Han, H.; Shen, H. Human Acellular Amniotic Matrix with Previously Seeded Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Restores Endometrial Function in a Rat Model of Injury. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 5573594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldin, L.T.; Cramer, M.C.; Velankar, S.S.; White, L.J.; Badylak, S.F. Extracellular Matrix Hydrogels from Decellularized Tissues: Structure and Function. Acta Biomater. 2017, 49, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Martínez, S.; Campo, H.; de Miguel-Gómez, L.; Faus, A.; Navarro, A.T.; Díaz, A.; Pellicer, A.; Ferrero, H.; Cervelló, I. A Natural Xenogeneic Endometrial Extracellular Matrix Hydrogel Toward Improving Current Human in Vitro Models and Future in Vivo Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 639688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, M.; Bahrami, S.; Mirshekari, H.; Basri, S.M.M.; Nik, A.B.; Aref, A.R.; Akbari, M.; Hamblin, M.R. Microfluidic Systems for Stem Cell-Based Neural Tissue Engineering. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 2551–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, S.N.; Ingber, D.E. Microfluidic Organs-on-Chips. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnecco, J.S.; Pensabene, V.; Li, D.J.; Ding, T.; Hui, E.E.; Bruner-Tran, K.L.; Osteen, K.G. Compartmentalized Culture of Perivascular Stroma and Endothelial Cells in a Microfluidic Model of the Human Endometrium. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 45, 1758–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Coppeta, J.R.; Rogers, H.B.; Isenberg, B.C.; Zhu, J.; Olalekan, S.A.; McKinnon, K.E.; Dokic, D.; Rashedi, A.S.; Haisenleder, D.J.; et al. A Microfluidic Culture Model of the Human Reproductive Tract and 28-Day Menstrual Cycle. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Study Design | PRP Injection Protocol | Control Group (n) | Intervention Group (n) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molina et al., 2018 [30] | Prospective interventional study | 1 mL PRP infusion on HRT day 10, repeated after 72 h | / | 19 | EMT increased; CPR 73.7%, LBR 26.3% |

| Eftekhar et al., 2018 [31] | RCT | 0.5–1 mL PRP infusion on cd13, repeated after 48 h if EMT still <7 mm | 43 | 40 | EMT; IR increased; CPR/cycle increased (32.5 vs. 14.0%); OPR/cycle increased (27.0 vs. 14.0%) |

| Chang et al., 2019 [32] | Prospective cohort study | 0.5–1 mL PRP infusion on cd10, repeated every 3 days until EMT > 7 mm | 30 | 34 | EMT, IR, and CPR increased (p < 0.05) |

| Kim et al., 2019 [33] | Prospective interventional study | 0.7–1 mL PRP infusion from cd10, repeated 2 or 3 times until EMT > 7 mm | / | 22 | EMT increased (0.6 mm); IR 12.7%, CPR 30%, OPR/LBR 20% |

| Kusumi et al., 2020 [34] | Prospective cohort compared with the prior cycle | 1 mL PRP infusion on cd10 and cd12 | / | 36 | EMT increased; CPR 15.6% |

| Russell et al., 2022 [35] | Retrospective cohort compared with the prior cycle | 0.5–0.75 mL PRP infusion several times between cd10 and 15 until EMT > 7 mm | / | 85 | EMT, CPR (37 vs. 20%); LBR (19% vs. 2%) increased |

| Agarwal et al., 2020 [36] | Cross-sectional study | Hysteroscopic subendometrial injection with 4 mL PRP (1 mL per wall) 7–10 days after injecting leuprolide during the previous cycle | / | 32 | EMT increased; CPR, ORP, and LBR increased |

| Frantz N et al., 2020 [39] | Retrospective study | 0.5 mL PRP intrauterine infusion after 14 to 17 days of oral estradiol valerate, repeated 2–3 times every second day | / | 21 (24 IVF cycles) | EMT did not increase; CPR (66.7%), LBR (54%, 13 cycles) |

| Dogra et al., 2022 [37] | Prospective interventional study | 0.5–1 mL PRP infusion on HRT day 8, repeated 2–3 times every 48 h until EMT > 7 mm | / | 20 | EMT increased; IR, CPR, and LBR increased significantly in a fresh group |

| Gangaraju et al., 2023 [38] | Prospective interventional study | 0.8 mL lyophilized PRP infusion 2–3 days before FET | / | 9 | EMT increased; positive pregnancy outcomes in 8/9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, Y.; Frisendahl, C.; Lalitkumar, P.G.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K. An Update on Experimental Therapeutic Strategies for Thin Endometrium. Endocrines 2023, 4, 672-684. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines4040048

Tang Y, Frisendahl C, Lalitkumar PG, Gemzell-Danielsson K. An Update on Experimental Therapeutic Strategies for Thin Endometrium. Endocrines. 2023; 4(4):672-684. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines4040048

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Yiqun, Caroline Frisendahl, Parameswaran Grace Lalitkumar, and Kristina Gemzell-Danielsson. 2023. "An Update on Experimental Therapeutic Strategies for Thin Endometrium" Endocrines 4, no. 4: 672-684. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines4040048

APA StyleTang, Y., Frisendahl, C., Lalitkumar, P. G., & Gemzell-Danielsson, K. (2023). An Update on Experimental Therapeutic Strategies for Thin Endometrium. Endocrines, 4(4), 672-684. https://doi.org/10.3390/endocrines4040048