Abstract

Diabetes-related distress (DRD) is defined as an emotional state experienced by people with diabetes (PWD) who are worried about their disease management, the emotional burden from the condition, and/or potential difficulties accessing care or support. The psychosocial aspect of diabetes management is a factor that directly influences patients’ well-being as well as the chronic management of the condition yet is not a primary clinical problem being addressed within the healthcare setting. This review advocates for a re-evaluation and subsequent adjustment of the current DRD screening methodology by implementing the five primary components (Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, Organizational, Community, and Public Policy) of the Socio-Ecological Model of Health (SEMH), bridging the gaps from a public-health perspective. We searched two electronic databases for studies published in the United States from 1995 to 2020 reporting the effects of social determinants of health (SDOH) on DRD. Articles that contained at least one of the five elements of the SEMH and focused on adults aged 18 years or older were included. SDOH, which include circumstances where individuals grow, work, and age, are highly influenced by external factors, such as the distribution of wealth, power, and resources. Current DRD screening tools lack the capacity to account for all major components of SDOH in a comprehensive manner. By applying the SEMH as a theory-based framework, a novel DRD screening tool addressing sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic background should be implemented to better improve diabetes management outcomes. By exploring the relationships between each level of the SEMH and DRD, healthcare professionals will be better equipped to recognize potential stress-inducing factors for individuals managing diabetes. Further efforts should be invested with the goal of developing a novel screening tool founded on the all-encompassing SEMH in order to perpetuate a more comprehensive diabetes treatment plan to address barriers within the SDOH framework.

1. Introduction

Diabetes is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States, affecting more than 34 million people [1,2]. Given the current diabetes epidemic and the lifelong battle following chronic disease diagnoses similar to diabetes, healthcare teams must aim to implement a holistic approach to patient care that guides patients to cope with the many complex challenges, e.g., the psychosocial aspect of disease management, and helps to address the social determinants of health (SDOH) when managing chronic conditions. Public health initiatives, such as Healthy People 2030, a time-oriented framework that intends to improve national health and wellness, seek to “reduce the burden of diabetes and improve quality of life for all people who have, or are at risk for, diabetes” [3].

Diabetes-related distress (DRD) is defined as an emotional state that arises when people with diabetes (PWD) worry about diabetes management, experience emotional burden resulting from diabetes, and/or feel frustrated getting access to care or support for diabetes management [4]. Considering that approximately half of the US population with diabetes is unable to meet standard treatment goals, it is not uncommon for many patients to feel diabetes burnout and gradually develop diabetes-related distress (DRD) [5]. By addressing DRD and taking SDOH into account, healthcare professionals can potentially contribute to reducing the burden of diabetes management.

Currently, there are two screening tools for DRD available to healthcare providers. The Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire, or PAID-20, was developed in 1995 as the first screening instrument for DRD [6]. In the original study, the sample population screened with PAID-20 demonstrated that increased levels of DRD correlated with higher HbA1c levels [6]. These results indicate the value of this 20-question screening tool in identifying psychosocial factors that contribute to the emotional burden of diabetes management. Once these psychosocial factors are acknowledged, the healthcare team may offer more targeted interventions to PWD and address suboptimal clinical outcomes [6].

A revision of the PAID-20 survey by Polansky and his team in 2005 led to the development of four primary domains of DRD: emotional, physician-related, regimen-related, and interpersonal. These four domains were further expanded into a new questionnaire, the Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS-17) [7]. DDS-17 employs a Likert scale similar to PAID-20 but instead opts for a 6-point system to capture patient responses [7]. At its initial review, DDS-17 did not show any significant differences among patients of various ethnicities, education, or sex [7]. However, recent studies have repeatedly shown considerable variations in DRD between males and females, socioeconomic status, and patients from different ethnicities, such as African American and Latino populations [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Due to the health inequities among patients with diabetes, some individuals face additional challenges when attempting to manage their diabetes. In order to identify and address the various challenges more effectively, PAID-20 and DDS-17 should be reassessed since their last revision was over 15 years ago, with the goal of incorporating the Socio-Ecological Model of Health (SEMH) as the widely agreed upon healthcare model to better address the SDOH associated with DRD [14].

2. Materials and Methods

The electronic databases of PubMed and Google Scholar were searched from 1995 to 2020 for evidence-based studies published in the United States that reported on the effects of SDOH on DRD. Articles that contained at least one of the five elements of the SEMH (Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, Organizational, Community, or Public Policy) and focused on adults aged 18 years or older were included. Articles that were not full-text or not published were excluded from this review.

3. Results

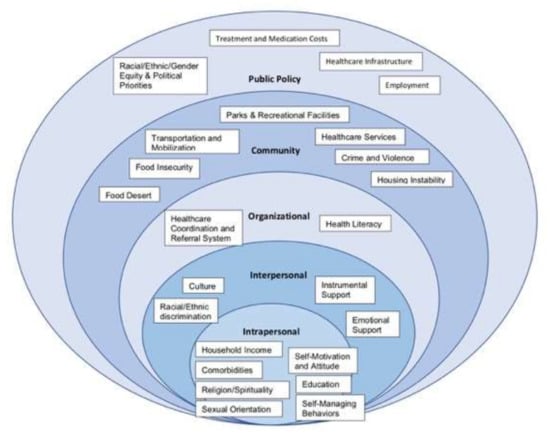

To provide a more holistic approach to diabetes care, screening methods for DRD should be revised to include questions relating to the five components of the SEMH: Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, Organizational, Community, and Public Policy (Table 1). The social and economic resources involved in each of these areas serve as the foundation of health and wellness opportunities in diverse patient populations, especially those managing chronic disease, such as diabetes. The SDOH include any circumstances in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age [15]. These conditions are shaped by a wider variety of forces, including the distribution of money, power, and resources at the local, national and global levels [15]. The SEMH is a theory-based framework for understanding how these SDOH can shape health-related issues [14]. Applying this system to diabetes management and DRD screening can help to identify useful points of intervention and provide a more comprehensive appreciation for how certain social problems are identified and addressed [14]. Additionally, the SEMH highlights how social issues can be sustained across various subsystems (e.g., an individual’s decisions and behaviors are a result of their social and physical surroundings) as illustrated in Figure 1. Once these adjustments are made to the DRD screening instruments, the specific underlying causes of DRD can be more apparent to both the patients and the healthcare providers so that specific treatment plans can be implemented to mediate those concerns. Through this model, we analyze and categorize the roles and functions that the SDOH play in patients with DRD.

Table 1.

Subcomponents of the socioecological model of health that are present or absent in the DDS-17 and PAID-20 questionnaires.

Figure 1.

The social determinants of health represented within each sector of the socioecological model of health.

4. Discussion

4.1. Intrapersonal

At the center of the SEMH are the individual factors relating to patient health and well-being that can be contributors to DRD. These intrapersonal components can be subdivided into those that are within the control of the patient (e.g., self-management, attitude, self-motivation) and those that are outside the control of the patient (e.g., education, household income, sexual orientation, comorbidities, religion, and spirituality). DRD can develop when these elements act as barriers to achieving successful healthcare outcomes. The following are just a few of the examples within the intrapersonal level of SEMH that can be identified and used to improve patients’ diabetes self-management.

4.1.1. Sexual Orientation

Sexual minorities, or individuals who identify as non-heterosexual, have higher rates of psychosocial distress than heterosexual individuals [16,17]. Within the intrapersonal construct, sexual orientation can serve as a barrier to diabetes care when patients withhold their sexual identity due to the fear of homophobia in the healthcare setting (e.g., insensitive comments, detached body language, non-inclusive dialogue) [18]. The decision to avoid intolerance can prevent patients from receiving appropriate preventative services, such as screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV), and hepatitis A and B [19]. Patients that do decide to “come out” might face a separate series of challenges, including access to healthcare and discrimination from providers [18]. In fact, sexual minorities with diabetes have higher levels of challenges incorporating diabetes care tasks into their lives than their heterosexual counterparts, such as attending annual screening exams, and many attribute their behavior to avoiding discrimination from their clinicians [20].

Consequently, the overall health of the LGBTQIA+ community is impaired by suboptimal health-related quality of life, increased psychosocial distress, and inadequate self-care behaviors (e.g., smoking) [16,17,21] The complex interplay between chronic disease management and stressors targeting sexual minorities can increase exposure to DRD, and therefore affect diabetes management. Redesigning DRD screening tools to include sexual orientation status recognizes the unique risk factors faced by sexual minorities with diabetes.

4.1.2. Self-Motivation and Attitude

As with many chronic conditions, a diabetes diagnosis is accompanied by various pathophysiological and psychological ramifications. In many cases, these psychological adversities can indirectly impact the outcomes of diabetes, resulting in difficulties for patients to manage this condition well [22]. In 2001, the cross-international Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes, and Needs (DAWN) study showed high reports of diabetes distress at the time of diagnosis due to the negative emotional aftermath that follows a life-changing diagnosis [23]. Interestingly, distress levels were also highly rated in patients that were diagnosed with diabetes nearly 15 years ago due to a separate set of circumstances, focusing on psychological and social factors as well as fear of future complications [23]. These findings show that DRD is a threat to the emotional and psychological well-being of patients from the moment they are diagnosed and continuing years into their treatment, putting patients at a higher risk of reduced medication adherence and self-care behaviors [24,25]. Additionally, these mental health implications have been shown to increase the risk for serious short- and long-term complications, which can result in blindness, amputations, stroke, cognitive decline, decreased quality of life, and even premature death [26].

Just as negative emotions can result in unmanaged diabetes, positive emotions can do the opposite. Retrospective reports from patients with diabetes have shown that reassuring messages from their healthcare providers and clear action plans are associated with lower levels of diabetes distress and better self-management at 1 to 5 years post-diagnosis [27]. This demonstrates how the mindsets and attitudes of both patients, and their providers can make a substantial difference in the treatment outcomes for patients with diabetes.

4.2. Interpersonal

Social support and interpersonal communication influence the burden of disease management by impacting stress levels and self-care behaviors. Supportive relationships can alleviate the worry, anxiety, and even physical sequelae associated with chronic diseases through assistance with self-care needs; support might include encouraging physical activity, providing healthy food, or even attending doctor’s appointments with the patient. Similarly, effective interpersonal communication within or outside the healthcare setting can improve the psychological health and wellness of patients. Positive discussions can create a safe space that encourages thoughts and feelings to be expressed, while the incorporation of prejudice, bias, and lack of cultural competence will likely define a negative dialogue. Patients with diabetes lacking adequate emotional support or facing barriers from their culture, race, or ethnicity are subject to increased distress and attenuated self-managing behaviors.

4.2.1. Instrumental Support

Instrumental support is defined as help received from others that is tangible and can be received in the form of seemingly simple actions aiding in diet, exercise, medication adherence, blood glucose monitoring, and managing medical appointments [28]. When thinking about disease management success, providers must understand that health promotion lies not just on the shoulders of patients but also on their families and communities. Social support can benefit patients’ health by buffering stress, increasing self-efficacy, and influencing changes in negative health behaviors [29]. The presence of a supportive social network has consistently been shown to positively affect a patient’s health status by increasing access to emotional, informational, and instrumental support [30]. Regarding chronic diseases such as diabetes, instrumental support has been directly linked to adherence to self-care behaviors [28].

Conversely, there can be negative outcomes that arise from non-supportive behaviors. Non-supportive behaviors are not just the absence of supportive behaviors but can be subdivided into two categories: sabotaging vs. miscarried helping behaviors. Sabotaging behaviors may come from family members who understand the patient may experience difficulties regarding their diabetes, yet do not help the patient with their self-care behaviors. Alternatively, miscarried helping behaviors consist of attempts from family members to aid diabetes self-care that ultimately produce conflicts [28]. Studies have shown that family members performing non-supporting behaviors were associated with less patient adherence to diabetes medications and worse glycemic management outcomes [28]. Patients with diabetes who may experience other sources of DRD can feel even more discouraged by non-supportive behaviors and further amplify the negative impacts associated with diabetes.

4.2.2. Cultural Barriers

A person’s culture is derived from their own ethnic group, instilling traditional foods, native dialects, and health beliefs within the individual [31]. Thus, when a patient’s culture differs from the mainstream environment of healthcare, cultural competency is required to bridge that gap.

When patients are newly diagnosed with diabetes, one of the main lifestyle changes they are recommended is to alter or restrict their usual food choices with guideline recommendations [31]. However, without providers adapting and modifying those recommendations to fit meals typical of the patient’s cultural background, adherence becomes difficult or distressing for patients [31]. Even if adaptations are suggested by healthcare providers, some cultures, such as that of many Chinese Americans, traditionally react to the onset of the disease by increasing food portions to nurture good health and comfort in the patient [32]. Subsequently, patients that do decide to modify and restrict their diet might begin to feel disconnected from friends and family during social gatherings, especially if culture emphasizes meal sharing [32]. In fact, concern and frustration regarding food limitations was reported as the main reason for DRD in African Americans [33].

Another type of cultural barrier may develop during patient-provider conversations when a patient’s culture believes traditional homeopathic treatments to be superior to Western practices [34]. Hispanic patients may consult family members or employ methods of folk healing when seeking more natural treatment options, such as medicinal plants (e.g., prickly pear cactus) for glycemic management [35]. Additionally, the misconception that insulin causes blindness is common within Hispanic culture due to the association of insulin with late-stage diabetes complications, thus creating resistance to initiating insulin pharmacotherapy [36]. Other common complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) recommended by healers or family members to manage diabetes are ginseng and aloe vera by Native Americans, noni juice by Pacific Islanders, prayer by African Americans, and vitamin supplements by Caucasians [35]. Healthcare professionals that are aware of the cultural context behind the use of CAMs can better understand their patients and use empathetic dialogue to discuss disease prognosis and the potential harm, adverse side effects, or DRD that can occur as a result of disease mismanagement.

Different cultures express a wide range of reactions to new diagnoses of diabetes, thus making it difficult for some patients with diabetes to follow newly recommended lifestyle modifications that are proposed by their providers. The varying ways in which cultures react to medical diagnoses can unintentionally delay patients’ treatment plans and act as a source of DRD. Additionally, a lack of effective communication between patients and providers in discussing and combating these potential problems that may arise can compound the issue and lead to additional DRD.

4.3. Organizational

The organizational aspect of the SEMH expands beyond the patient’s immediate social circle and into broader territories. This level encompasses institutions and services (such as health care service coordination and referrals) that ultimately influence patient behaviors, as well as systemic sources of health literacy [14].

4.3.1. Healthcare Service Coordination and Referrals

According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), when diabetes management goals are not achieved, referrals to other disease management sources should be considered, including Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support (DSMES) services or metabolic specialists [37]. Challenges regarding the referral system occur when primary care providers are unable to see the value of certain referral networks or when those networks are underutilized. Specifically, providers that do not recognize the value of DSMES services or have yet to establish DSMES referral networks ultimately inhibit any potential benefits those services may provide to individuals seeking increased diabetes knowledge [38,39]. In fact, previous data have shown that less than 7% of privately insured patients and less than 6% of Medicare beneficiaries were referred to receive DSMES services within the first year of their type 2 diabetes diagnosis [39].

In the primary care setting, the utilization of interdisciplinary teams provides patients with integrated and comprehensive treatment options to better manage glycemic and lipid markers as well as emotional distress [40]. A team of individuals specialized in diabetes education, health coaching, and depression was set up to deliver tailored treatment plans for patients with diabetes in a southern California clinic for one year; during this time, the intervention group showed significant improvements in DRD by nearly 10% [40]. Without the support of integrative care teams, patients are likely unable to adequately receive a comprehensive assessment of their well-being, further perpetuating the distressing effects on mental and physical health. Each participating member of a DSMES team can help to identify patients unknowingly struggling with DRD and work through the emotional burden of diabetes management to restore a sense of balance to the patient’s life [41]. Additionally, patients appropriately referred to metabolic specialists show decreased levels of DRD and greater physician satisfaction [42]. Facilitation among health care teams stratifies patients based on medical needs, so treatment plans are individualized to the patient’s lifestyle, leading to increased self-care behaviors [43].

Patients that are suboptimally referred to specialists or DSMES services by their primary care providers are often left devoid of the additional skills and coping behaviors necessary to manage the ongoing burden of diabetes, resulting in increased DRD. If the referring primary care providers do, however, decide to utilize the referral process, they must clearly explain to the patient the reason for the referral before the process begins and follow-up with the referred organization each time after the DSMES team sees the patient. Without these measures taking place, the referral process itself can be distressing to patients [44]. Departments lacking efficient and sufficient communication induce delayed treatment plans, redundant test ordering, and poor quality of overall care [44]. As such, disorganization within the referral process can lead to miscommunication among clinicians, contributing to DRD for patients.

4.3.2. Health Literacy

Health literacy is the ability of the patient to understand and appropriately apply health information; however, sometimes health organizations are roadblocks for patients to enhance their health literacy, including providers communicating ineffectively or not recognizing patient limitations, such as old age, disability, cultural norms, and language barriers [45].

Health literacy can be influenced by internal factors (e.g., education level, socioeconomic status, and language barriers) as well as external factors (e.g., navigating complicated and ever-changing medical guidelines, lack of clarity in diabetes education materials, and suboptimal delivery of care) [46]. Health literacy stands as one of the most significant predictors of self-care behavior in diabetes, from understanding verbal instructions in the clinic to written instructions on prescriptions and even comprehending the importance of the behavioral aspect of disease management (i.e., making appointments, ordering medical supplies, eating healthy, blood glucose monitoring) [47,48]. Though more common in patients with lower socioeconomic status, low levels of health literacy can affect all patients and have been shown to correlate with increased hospitalizations, emergency room visits, and decreased compliance to guideline recommendations for diabetes regarding diet, exercise, medication, and blood sugar testing [46]. Since decreased self-care behaviors put patients at a higher risk for DRD, health literacy determinants should be screened as potential sources of distress [47].

4.4. Community

Approaching the outer levels of the SEMH, we turn our attention to the community aspect of health and assess whether the availability and location of resources that promote health, social networks, and social norms has a distressful impact on patient health. Community-based subcategories that unknowingly play a role in diabetes care include the quality and access to health care services, transportation and mobilization, parks and recreation facilities, crime and violence, civic participation, housing inequality, food deserts and food insecurity [14]. Barriers within each of these categories can expose patients with diabetes to increased distress, ultimately impairing treatment success.

4.4.1. Crime and Violence

Physical activity is a cardinal element in diabetes management due to its many health benefits, but a patient’s perceived safety in their community is often an oversight for many providers. A recent study conducted in a low-income community showed that women who felt unsafe walking alone outdoors at night reported fewer steps per day [49]. Another recent study conducted in northern California highlighted that crime and violence disproportionately increase stress among African American and Latina women with diabetes more than men with diabetes, possibly due to increased fear of victim vulnerability [50]. The impact of these fears can also affect a patient’s mental health. High rates of neighborhood crime and violence have historically been related to increased stress among disadvantaged populations [50]. PWD who live in areas with heightened crime and violence are susceptible to this psychosocial stress, which can worsen self-care behaviors and glycemic management [50]. Additionally, a longitudinal study found that limited neighborhood safety is associated with long-term anxiety and depression [51]. Living in an unsafe environment negatively impacts physical and mental health, making it more difficult for patients with diabetes to achieve optimal blood glucose levels and further contributing to DRD.

One component of DRD involves lack of control about one’s self-management and neighborhood safety is often an uncontrollable factor influencing how often patients engage in physical activity. Perilous areas negatively affect physical and mental health, especially for those living in low-income communities. Therefore, inquiring of patients how safe they perceive their community to be will help providers understand the social barriers involved in diabetes management.

4.4.2. Food Insecurity

Food insecurity refers to the inability to afford or attain food, which may lead to the risk or reality of going hungry [52]. At the community level, nutritious food may be more expensive or limited than less healthy options due to the higher costs of preparing and transporting the products [53]. Eating a healthy diet is one of the daily self-care behaviors that PWD are asked to maintain, but this task becomes difficult when there is a lack of funds for or access to healthy foods. This is especially difficult for patients with lower socioeconomic backgrounds because they are more prone to experiencing low food security, ultimately resorting to unhealthy, inexpensive food in order to meet and afford their caloric demands [52,53]. PWD who opt to substitute healthy foods for less expensive, less nutritious alternatives has increased HbA1c levels and higher rates of obesity [52,54]. Additionally, decreased self-efficacy and increased levels of DRD have been associated with food insecurity [52,54]. PWD who have food insecurity may feel like they are unable to control what they can eat, and this feeling of helplessness can contribute to their DRD [54]. Healthy meal planning remains an issue for PWD with low SES, and those issues should be considered during conversations between providers and patients.

4.5. Public Policy

The public policy component of the SEMH embodies a wider set of forces that ultimately influences the course of diabetes care for patients in the United States. DRD can develop when policies related to treatment and medication costs, employment, equity, and healthcare infrastructure stand in the way of successful diabetes management.

4.5.1. Treatment and Medication Costs

The ADA estimated the cost of managing diabetes to be $327 billion in 2017 [55]. ADA also found that patients with diabetes accrued average medical expenditures of $16,752 per year, where $9601 was directly linked to diabetes management [55]. Other data showed that managing diabetes could cost patients 2.3 times more than those without the disease [2]. In addition, one out of every four dollars of U.S. healthcare expenditure was on diabetes-associated care [56]. With the ever-growing population of PWD, future medical costs to the entire system are only expected to increase.

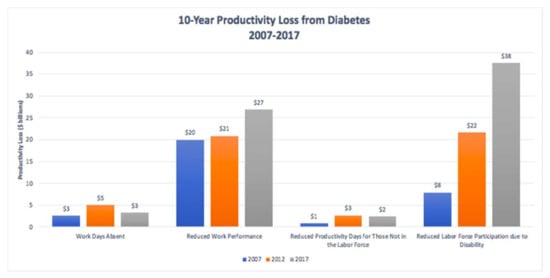

Every five years since 2007, the ADA has reported the financial burden of diabetes in the U.S., including both direct and indirect costs [55,57,58]. The indirect costs that contribute to a loss in productivity include absenteeism, presenteeism, disability, reduced productivity in unemployed PWD, and mortality. Comparing each of these aspects shows trending patterns during the years of data collection (Figure 2). The largest increase in productivity loss from diabetes during that time period was estimated to be $30 billion as seen in reduced labor force participation due to disability [55,57,58].

Figure 2.

Productivity loss in billions from workdays absent, reduced work performance, reduced productivity days for those not in the labor force, and reduced labor force participation due to disability—rounded to the nearest tenth (blue—2007, orange—2012, gray—2017) [55,58,59].

The cost of diabetes management is categorized into two broad categories: tangible and intangible, where tangible costs are subdivided as direct or indirect costs [59]. Direct costs of diabetes are expenses that are attributable directly to diabetes, including the costs for both inpatient and outpatient medical expenses, emergency room visits, medications, medical supplies, and laboratory tests [59,60]. Many patients cannot afford to pay for their medications (e.g., insulin) even if they have healthcare insurance coverage, significantly contributing to the development of DRD. Indirect costs include absenteeism (workdays missed from employees due to diminished health), presenteeism/productivity (decreased productivity at work), disability, early retirement, and premature death [60,61]; an example of this would be spending time away from work due to the various, necessary medical appointments. Performing less efficiently at work than people without diabetes means that this already vulnerable population becomes more susceptible to financial struggles, which may cause them to experience higher levels of distress, poorer diabetes management, and poorer health outcomes. While absenteeism costs within the U.S. healthcare infrastructure remained consistent, presenteeism has led to a productivity loss of $7 billion [55,57,58].

Intangible costs associated with diabetes include the emotional burden that results from living with diabetes, such as DRD, anxiety, and depression [62]. PWD distress has higher relative risk ratios for presenteeism and absenteeism than those without diabetes distress [63]. This may be due to the difficulties of balancing work life and diabetes management, fear of hypoglycemia, and/or reluctance to self-monitor blood glucose consistently at the workplace [64]. Public policy measures should be placed to ensure PWD are able to participate in the workforce without sacrificing proper diabetes management.

4.5.2. Employment

PWD are often part-time employed or not employed at all [65]. Between 1992 and 1994, the probability of unemployment was four times higher in women with diabetes and seven times higher in men with diabetes than those without the disease [65]. Members of the same research team conducted a second study that investigated the U.S. workforce between 1997 and 2005 to evaluate age-related differences between the two groups [66]. The research team found that the unemployment rate in PWD between 20 and 44 years was 3.4% higher than the cohort without diabetes, while those between the range of 45 to 64 years old with diabetes experienced 3.4% higher unemployment rates than the cohort without diabetes [66]. Higher unemployment rates in PWD suggest that managing this chronic disease puts them at a higher chance of experiencing economic hardship than the population without diabetes, thus translating into a source of distress. Therefore, employers should encourage individuals with diabetes to carry out safe health practices as recommended by their healthcare providers. Supportive work environments have been shown to facilitate greater efficiency at work and to reduce the number of absent days for PWD since their distress levels have been shown to be better managed [64].

5. Conclusions

The current screening tools, such as PAID-20 and DDS-17, do not comprehensively identify the complex nature and variety of sources that can contribute to or develop DRD. In order to provide optimal diabetes management, a novel screening tool based on the SEMH should be considered as a more comprehensive replacement to the current standards of DRD screening tools. Each of the five social circles outlined in the SEMH plays a specific role in a patient’s health and key components of each circle should be considered, when providing patient-centered diabetes management. We propose that any factor within the model can prevent patients with diabetes from effectively self-managing their condition and thus lead to increased DRD and suboptimal diabetes-related health outcomes. Since we have acknowledged some of the gaps of the DDS-17 and PAID-20 screening tools, our hope is for future efforts to design an enhanced screening instrument that incorporates questions based within each of the levels of the well-known SEMH to assess, anticipate, and evaluate DRD elements.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, N.F. and M.L.; writing—review and editing, C.Y., K.V. and S.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Heron, M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2017. Natl. Vital. Stat. Rep. 2019, 68, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, CA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/statistics-report.html (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Diabetes. Diabetes—Healthy People 2030. Available online: Health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/diabetes (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Kreider, K.E. Diabetes Distress or Major Depressive Disorder? A Practical Approach to Diagnosing and Treating Psychological Comorbidities of Diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2017, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beverly, E.A.; Ivanov, N.N.; Court, A.B.; Fredricks, T.R. Is diabetes distress on your radar screen? J. Fam. Pract. 2017, 66, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Polonsky, W.H.; Anderson, B.J.; Lohrer, P.A.; Welch, G.; Jacobson, A.M.; Aponte, J.E.; Schwartz, C.E. Assessment of Diabetes-Related Distress. Diabetes Care 1995, 18, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, W.H.; Fisher, L.; Earles, J.; Dudl, R.J.; Lees, J.; Mullan, J.; Jackson, R.A. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: Development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanayakkara, N.; Pease, A.; Ranasinha, S.; Wischer, N.; Andrikopoulos, S.; Speight, J.; De Courten, B.; Zoungas, S. Depression and diabetes distress in adults with type 2 diabetes: Results from the Australian National Diabetes Audit (ANDA) 2016. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houle, J.; Lauzier-Jobin, F.; Beaulieu, M.-D.; Meunier, S.; Coulombe, S.; Côté, J.; Lespérance, F.; Chiasson, J.-L.; Bherer, L.; Lambert, J. Socioeconomic status and glycemic control in adult patients with type 2 diabetes: A mediation analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2016, 4, e000184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, A.E. The “A to Z” of Managing Type 2 Diabetes in Culturally Diverse Populations. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebron, A.M.W.; Valerio, M.A.; Kieffer, E.C.; Sinco, B.R.; Rosland, A.-M.; Hawkins, J.; Espitia, N.; Palmisano, G.; Spencer, M. Everyday Discrimination, Diabetes-Related Distress, and Depressive Symptoms Among African Americans and Latinos with Diabetes. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2013, 16, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBrón, A.M.W.; Spencer, M.; Kieffer, E.; Sinco, B.; Palmisano, G. Racial/Ethnic Discrimination and Diabetes-Related Outcomes Among Latinos with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, L.R.; Sevick, M.A. Racial differences in diabetes-related psychosocial factors and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Pat. Pref. Adher. 2010, 4, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Max, J.L.; Sedivy, V.; Garrido, M. Increasing Our Impact by Using a Social-Ecological Approach; Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Family and Youth Services Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. Available online: www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Bränström, R.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Pachankis, J.E.; Link, B.G. Sexual Orientation Disparities in Preventable Disease: A Fundamental Cause Perspective. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptiste-Roberts, K.; Oranuba, E.; Werts, N.; Edwards, L.V. Addressing Health Care Disparities Among Sexual Minorities. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2017, 44, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnero, T.L. Providing Culturally Sensitive Diabetes Care and Education for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Community. Diabetes Spectr. 2010, 23, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroll, A.E.; Mosack, K.E. Physician Awareness of Sexual Orientation and Preventive Health Recommendations to Men Who Have Sex with Men. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2011, 38, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.; Tran, L.; Tran, L. Influence of sexual orientation on diabetes management in US adults with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2020, 47, 101177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, B.M.; Gordon, A.R.; Reisner, S.L.; Sarda, V.; Samnaliev, M.; Austin, S.B. Sexual orientation-related disparities in employment, health insurance, healthcare access and health-related quality of life: A cohort study of US male and female adolescents and young adults. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tareen, R.S.; Tareen, K. Psychosocial aspects of diabetes management: Dilemma of diabetes distress. Transl. Pediatr. 2017, 6, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovlund, S.E.; Peyrot, M.; DAWN International Advisory Panel. The Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes, and Needs (DAWN) Program: A New Approach to Improving Outcomes of Diabetes Care. Diabetes Spectr. 2005, 18, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, N.E.; Davies, M.J.; Robertson, N.; Snoek, F.J.; Khunti, K. The prevalence of diabetes-specific emotional distress in people with Type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2017, 34, 1508–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrot, M.; Burns, K.K.; Davies, M.; Forbes, A.; Hermanns, N.; Holt, R.; Kalra, S.; Nicolucci, A.; Pouwer, F.; Wens, J.; et al. Diabetes Attitudes Wishes and Needs 2 (DAWN2): A multinational, multi-stakeholder study of psychosocial issues in diabetes and person-centred diabetes care. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2012, 99, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducat, L.; Philipson, L.H.; Anderson, B.J. The Mental Health Comorbidities of Diabetes. JAMA 2014, 312, 691–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polonsky, W.H.; Fisher, L.; Guzman, S.; Sieber, W.J.; Philis-Tsimikas, A.; Edelman, S.V. Are patients’ initial expe-riences at the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes associated with attitudes and self-management over time? Diabetes Educ. 2010, 36, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayberry, L.S.; Osborn, C.Y. Family Support, Medication Adherence, and Glycemic Control Among Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMatteo, M.R. Social Support and Patient Adherence to Medical Treatment: A Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. 2004, 23, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciechanowski, P.; Russo, J.; Katon, W.J.; Lin, E.H.; Ludman, E.; Heckbert, S.; Von Korff, M.; Williams, L.H.; Young, B.A. Relationship Styles and Mortality in Patients with Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 33, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, K.D. Food, Culture, and Diabetes in the United States. Clin. Diabetes 2004, 22, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesla, C.A.; Chun, K.M.; Kwan, C.M. Cultural and Family Challenges to Managing Type 2 Diabetes in Immigrant Chinese Americans. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 1812–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, S.; Irby-Shasanmi, A.; De Groot, M.; Martin, E.; Lajoie, A.S. Understanding Diabetes-Related Distress Characteristics and Psychosocial Support Preferences of Urban African American Adults Living with Type 2 Diabetes: A Mixed-Methods Study. Diabetes Educ. 2018, 44, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundisini, F.; Vanstone, M.; Hulan, D.; DeJean, D.; Giacomini, M. Type 2 diabetes patients’ and providers’ differing perspectives on medication nonadherence: A qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Caballero, L.; Morello, C.M.; Chynoweth, M.E.; Prieto-Rosinol, A.; Polonsky, W.H.; Palinkas, L.A.; Edelman, S.V. Ethnic differences in complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with diabetes. Complement. Ther. Med. 2010, 18, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Amirehsani, K.A.; Wallace, D.C.; Letvak, S. The meaning of insulin to Hispanic immigrants with type 2 diabetes and their families. Diabetes Educ. 2012, 38, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care for Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, s33–s50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushforth, B.; McCrorie, C.; Glidewell, L.; Midgley, E.; Foy, R. Barriers to effective management of type 2 diabetes in primary care: Qualitative systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, e114–e127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, M.A.; Bardsley, J.K.; Cypress, M.; Funnell, M.M.; Harms, D.; Hess-Fischl, A.; Hooks, B.; Isaacs, D.; Mandel, E.D.; Maryniuk, M.D.; et al. Diabetes Self-management Education and Support in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Consensus Report of the American Diabetes Association, the Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of PAs, the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, and the American Pharmacists Association. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 1636–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortmann, A.L.; Walker, C.; Barger, K.; Robacker, M.; Morrisey, R.; Ortwine, K.; Loupasi, I.; Lee, I.; Hogrefe, L.; Strohmeyer, C.; et al. Care Team Integration in Primary Care Improves One-Year Clinical and Financial Outcomes in Diabetes: A Case for Value-Based Care. Popul. Health Manag. 2020, 23, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallayova, M.; Taheri, S. Targeting Diabetes Distress: The Missing Piece of the Successful Type 1 Diabetes Management Puzzle. Diabetes Spectr. 2014, 27, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuniss, N.; Kramer, G.; Müller, N.; Kloos, C.; Lehmann, T.; Lorkowski, S.; Wolf, G.; Müller, U.A. Diabetes-Related Burden and Distress is Low in People with Diabetes at Outpatient Tertiary Care Level. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2016, 124, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academy of Engineering (US); Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Engineering; The Health Care System; Reid, P.; Compton, W.D.; Grossman, J.H. (Eds.) Building a Better Delivery System: A New Engineering/Health Care Partnership. In A Framework for a Systems Approach to Health Care Delivery; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2005. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22878/ (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Gandhi, T.K.; Sittig, D.F.; Franklin, M.; Sussman, A.J.; Fairchild, D.G.; Bates, D.W. Communication breakdown in the outpatient referral process. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2000, 15, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Service. Healthy People 2030. 2020. Available online: https://health.gov/our-work/healthy-people-2030/about-healthy-people-2030/health-literacy-healthy-people (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Jansen, T.; Rademakers, J.; Waverijn, G.; Verheij, R.; Osborne, R.; Heijmans, M. The role of health literacy in explaining the association between educational attainment and the use of out-of-hours primary care services in chronically ill people: A survey study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinckus, L.; Dangoisse, F.; Broucke, S.V.D.; Mikolajczak, M. When knowing is not enough: Emotional distress and depression reduce the positive effects of health literacy on diabetes self-management. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, S.C.; Brega, A.G.; Crutchfield, T.M.; Elasy, T.; Herr, H.; Kaphingst, K.; Karter, A.J.; Moreland-Russell, S.; Osborn, C.Y.; Pignone, M.; et al. Update on Health Literacy and Diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2014, 40, 581–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, G.G.; McNeill, L.H.; Wolin, K.; Duncan, D.T.; Puleo, E.; Emmons, K.M. Safe to Walk? Neighborhood Safety and Physical Activity Among Public Housing Residents. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, A.; Mujahid, M.S.; Laraia, B.; Warton, E.M.; Blanchard, S.D.; Kelly, M.; Moffet, H.H.; Adler, N.; Schillinger, D.; Karter, A.J. Police-Recorded Crime and Perceived Stress among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). J. Hered. 2016, 93, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinette, J.W.; Charles, S.T.; Gruenewald, T.L. Vigilance at home: Longitudinal analyses of neighborhood safety perceptions and health. SSM Popul. Health 2016, 2, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, H.K.; Jacobs, E.A.; Lopez, A.; Tschann, J.; Fernandez, A. Food Insecurity and Glycemic Control Among Low-Income Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A.; Darmon, N. Food Choices and Diet Costs: An Economic Analysis. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, J.; Krieger, J.; Kiefer, M.; Hebert, P.; Robinson, J.; Nelson, K. The Relationship Between Food Insecurity and Depression, Diabetes Distress and Medication Adherence Among Low-Income Patients with Poorly-Controlled Diabetes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, M.C.; Herman, W.H. The Cost of Diabetes Care—An Elephant in the Room. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 929–932. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2007. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 596–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Toh, M.P.; Ko, Y. Cost-of-illness studies of diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 105, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breton, M.-C.; Guénette, L.; Amiche, M.A.; Kayibanda, J.-F.; Grégoire, J.-P.; Moisan, J. Burden of Diabetes on the Ability to Work. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, S.S.; Honeycutt, A.A.; Yang, W.; Zhang, P.; Khavjou, O.A.; Poehler, D.C.; Neuwahl, S.J.; Hoerger, T.J. Economic Costs Attributable to Diabetes in Each U.S. State. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2526–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, E.; Lockhart, S.; Davies, M.; Lindsay, J.R.; Dempster, M. Diabetes distress: Understanding the hidden struggles of living with diabetes and exploring intervention strategies. Postgrad. Med. J. 2015, 91, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, L.; Scuffham, P.A.; Hilton, M.F.; Ware, R.S.; Vecchio, N.; Whiteford, H.A. Health-related productivity losses increase when the health condition is co-morbid with psychological distress: Findings from a large cross-sectional sample of working Australians. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkarainen, P.; Moilanen, L.; Hänninen, V.; Heikkinen, J.; Räsänen, K. Work-related diabetes distress among Finnish workers with type 1 diabetes: A national cross-sectional survey. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2016, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunceli, K.; Bradley, C.J.; Nerenz, D.; Williams, L.K.; Pladevall, M.; Lafata, J.E. The Impact of Diabetes on Employment and Work Productivity. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 2662–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunceli, K.; Zeng, H.; Habib, Z.A.; Williams, L.K. Long-term projections for diabetes-related work loss and limitations among U.S. adults. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2009, 83, e23–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).