1. Introduction

Concrete structure has become the preferred form for the main structural components of numerous infrastructure projects such as tunnels, bridges, and dams due to its excellent mechanical properties and durability [

1,

2,

3]. However, it is affected by multiple factors such as the complex external environment and inadequate maintenance management measures during the operation period after a tunnel is put into operation, resulting in the generation and expansion of cracks on the inner surface of the tunnel. These cracks will weaken the overall bearing capacity and water resistance of the tunnel structure, accelerate the corrosion of internal reinforcing bars and the deterioration of the structure, and seriously threaten the long-term operational safety of the tunnel [

4]. Advance identification and evaluation of cracks on the tunnel inner surface, coupled with the formulation of corresponding preventive maintenance strategies, can enhance structural durability, extend service life, and ensure long-term operational safety of the tunnel [

5]. Based on quantitative crack detection indicators (such as length and width), and combined with relevant specifications to classify risk levels, key data support can be provided for tunnel operation and management.

Traditional manual inspection of cracks relies on individual experience judgment and subjective perception, which has limitations such as low detection efficiency, long inspection cycle, and human subjectivity [

6]. With the development of the computer vision theory system and the continuous innovation of deep learning network architectures, the maturity of automated crack detection technology in the tunnel field has significantly improved [

7]. In this context, the application of machine vision to automated tunnel crack detection has exhibited a rapidly growing trend. Currently, deep learning-based crack detection methods can be broadly categorized into three types: classification algorithms designed specifically to determine the presence or absence of cracks, object detection algorithms that simultaneously address crack recognition and localization, and segmentation algorithms capable of achieving pixel-level differentiation between cracks and background [

8].

In the field of image classification, Lecun et al. [

9] proposed the LeNet-5 model, initially for handwritten character recognition and classification. Its innovative “convolution-pooling-full connection” architecture not only broke through detection accuracy but also laid the foundation for the CNN paradigm, providing a core framework for the development of CNN in the field of computer vision. Szegedy et al. [

10] proposed the classic deep convolutional neural network model GoogleNet, and the designed Inception deep convolutional network module helped the model achieve a 6.66% error rate in image classification tasks. Hoang [

11] constructed a network model integrating multiple support vector machines (SVM) and combined with the optimistic algorithm of artificial bee colony, achieving a classification accuracy of 96%. Que et al. [

12] improved the G-set network, introducing global average pooling layer and batch normalization layer, adjusting the Softmax classifier, optimizing the learning rate, activation function and convolution kernel size, and the experimental recognition accuracy was 0.9630, F1 score 0.9623. Among these studies, some methods have strong crack detection capabilities but low accuracy. While certain methods achieve high classification accuracy, they suffer from inadequate precision in crack classification criteria.

In the field of object detection, the YOLO (You Only Look Once) series models, with their unique design concepts and outstanding performance, have become a research hotspot in the field of object detection. Redmon et al. [

13] proposed the YOLOv1 model, which can directly predict bounding boxes and category probabilities from the complete image, with fast detection speed and high performance. The following year, Redmon et al. [

14] designed the Darknet-19 architecture, optimizing the loss function to reduce the difficulty of model learning, improve the effect of feature learning and stability; YOLOv2 model performed well in evaluations on datasets such as PASCAL VOC and COCO. YOLOv3 has adopted the Darknet-53 backbone network with 53 convolutional layers, which has a significant increase compared to YOLOv2’s 19 layers [

15]. Alipour [

16] identified that material property changes would notably diminish the crack detection accuracy of custom models, leading to the proposition of joint training, sequential training, and ensemble learning to build a cross-material robust model, where the experimental training accuracy of all three methods attained 97%. Adel et al. [

17] used the U-Net network to detect the distribution of concrete crack pits. The dataset was expanded from 1600 images to 6400 images by flipping and rotating and the model accuracy reached 99.65%. Yilmaz [

18] utilized YOLOv5, YOLOv8, and YOLOv11 models for the segmentation and quantification of mortar cracks, achieving a mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) of 81.2%, an accuracy of 95%, and an error rate of 4.1% in crack width measurement.

Pixel-level semantic segmentation classifies and labels the crack areas pixel by pixel, providing accurate geometric information for structural assessment and supporting detailed analysis [

19]. Hsieh et al. [

20] reviewed machine learning-based crack detection methods, evaluated 8 segmentation models, found that specific network structures can improve performance, and pointed out that solving the false-positive problem is the key to optimization. Zhang et al. [

21] proposed a crack visual detection system based on a context-aware deep semantic segmentation network: by adaptively sliding windows to locate image blocks, pixel labels are assigned through the SegNet encoder–decoder, and then integrated using the CAOPF scheme, enabling the detection of cracks in different environments. Wang et al. [

22] proposed a new pixel-level crack segmentation model called SegCrack, which uses a hierarchical-structured Transformer encoder to output multi-scale features; this model achieves an F1 score of 96.05% and an mIoU of 92.63%. Chen et al. [

23] designed a fully convolutional neural network, enhancing the representation of crack features through multi-level extraction and class feature optimization. Ma et al. [

24] proposed the CRTransU-Net underwater concrete crack real-time segmentation model, which can solve the problem of foreground-background imbalance, achieving a segmentation performance superior to U-Net and other models, and the quantitative results of crack geometric dimensions have a high degree of consistency. Kang et al. [

25] proposed an integrated method for automatic crack detection, location, and quantification, integrating Faster R-CNN to detect crack areas; experiments show that the average detection accuracy reaches 95%. Hang et al. [

26] improved the pixel-level detection accuracy by using vertical and horizontal compression attention modules and efficient channel attention upsampling. Currently, numerous studies exist on pixel-level semantic segmentation for crack images. While some achieve ideal detection accuracy, model recognition efficiency remains improvable. Furthermore, the majority of studies concentrate merely on segmentation and recognition, while related research and application schemes need further advancement in efficiently transforming segmentation results into quantitative references for structural safety assessment and underpinning subsequent engineering decisions.

In the field of quantitative analysis of the length and width of concrete cracks, KO et al. [

27] developed an open-source automatic detection software (ABECIS) specifically for external cracks in buildings. The software has a median error of 8.2% in the total estimated length of detected cracks. The research team also pointed out that in the future, the research direction will be further expanded to the prediction of crack width, depth, and other dimensional parameters. Patzelt et al. [

28] achieved quantitative analysis of cracks with a maximum area of 40 cm

2 through a series of technical processes including image preprocessing, machine learning algorithm design, and Python 3.14.2 script development. This method can automatically estimate the area, length, and width of cracks in a single workflow. Yuan et al. [

29] proposed a deep learning crack detection method called R-FPANet, which can automatically segment and quantify the shape of cracks at the pixel scale. The core improvement lies in the introduction of channel attention modules and position attention modules, which strengthen the dependency and correlation between features. Experimental results show that this method can quantitatively analyze core geometric parameters such as crack area, length, average width, and maximum width at the pixel level, with an average intersection-over-union (mIoU) of 83.07%. Feng et al. [

30] optimized and improved the CDDS network by leveraging the core architecture of SegNet to accurately extract fracture size parameters. Crack length is quantified as the cumulative count of skeleton pixels, while crack area is determined by the total number of pixels in the crack prediction mask. The average crack width is subsequently derived from the computed area. The network achieved a recall rate, precision rate, and F1 score of 80.45%, 80.31%, and 79.16%, respectively. Maslan et al. [

31] conducted automatic detection, size measurement, and position positioning research on transverse cracks in concrete runway plates based on the YOLOv2 model. The average accuracy (AP) of crack detection reached 0.89, meeting the requirements for practical deployment in engineering, and the method can further achieve position positioning of cracks within the concrete plate and the calculation of length, width parameters. Existing studies still have significant limitations in the quantitative dimension and scene adaptability of cracks. In response to problems such as dim lighting, illumination light obstruction, and complex crack distribution patterns in tunnel scenarios, the precise quantitative analysis of concrete cracks in complex tunnel environments remains a current research hotspot.

To achieve rapid and accurate identification of cracks on the inner surface of tunnel concrete, this study proposes an LiteSqueezeSeg network, which is an enhanced version of the open-source semantic segmentation model SqueezeNet. The core innovation lies in focusing on the “Lightweight Semantic Segmentation” as the core objective. Miao et al. [

32] previously conducted a comparative study between the LiteSqueezeSeg method and other lightweight models (e.g., MobileNet, GoogleNet), demonstrating that LiteSqueezeSeg has only half the number of parameters as GoogleNet and outperforms MobileNet in all three core evaluation metrics: accuracy, intersection over union (IoU), and F1-score. The proposed network is applied to the precise detection and quantitative measurement of concrete surface crack widths. Furthermore, the segmentation results are integrated with established industry standards to provide a scientific basis for monitoring and assessing tunnel structural conditions.

2. Crack Recognition

Deep learning technology builds a deep neural network model with multiple layers of nonlinear transformations to utilize massive data for automatic feature learning, enabling end-to-end automated processing of complex tasks. In the field of crack recognition, since cracks typically manifest as local, slender, and complex-edge-targets, convolutional neural networks, with their unique local receptive fields, weight sharing, and pooling operations, can efficiently extract spatial hierarchical features (such as edges, textures, shapes, etc.) from images, effectively improving the accuracy of small target recognition and the robustness of target extraction in complex backgrounds. Therefore, this study selects the convolutional neural network algorithm to conduct research on deep learning recognition of cracks. The open-source semantic segmentation model SqueezeSeg was improved specifically to enable it to effectively extract the local spatial features of cracks in the research.

2.1. Dataset Preparation

The labeled image serves as the foundation for pixel-level semantic segmentation. The Image Labeler tool was employed to perform pixel-level and region-level annotation on a total of 10,000 images in JPG format. Among these, 6000 images were sourced from the Surface Crack Detection public dataset, while the remaining 4000 were generated by augmenting approximately 500 tunnel inner surface images through geometric transformations, including rotation, flipping, and cropping. Targeted image processing techniques are adopted to preprocess the original images: the uneven lighting issue is corrected via a brightness equalization algorithm, surface impurity interference is eliminated using image denoising and stain segmentation technologies, and visual features of crack regions are enhanced by combining operations such as contrast enhancement and sharpening. Through the aforementioned preprocessing pipeline, the consistency of images and the distinguishability of target regions are effectively improved. The corresponding annotation labels are stored in PNG format.

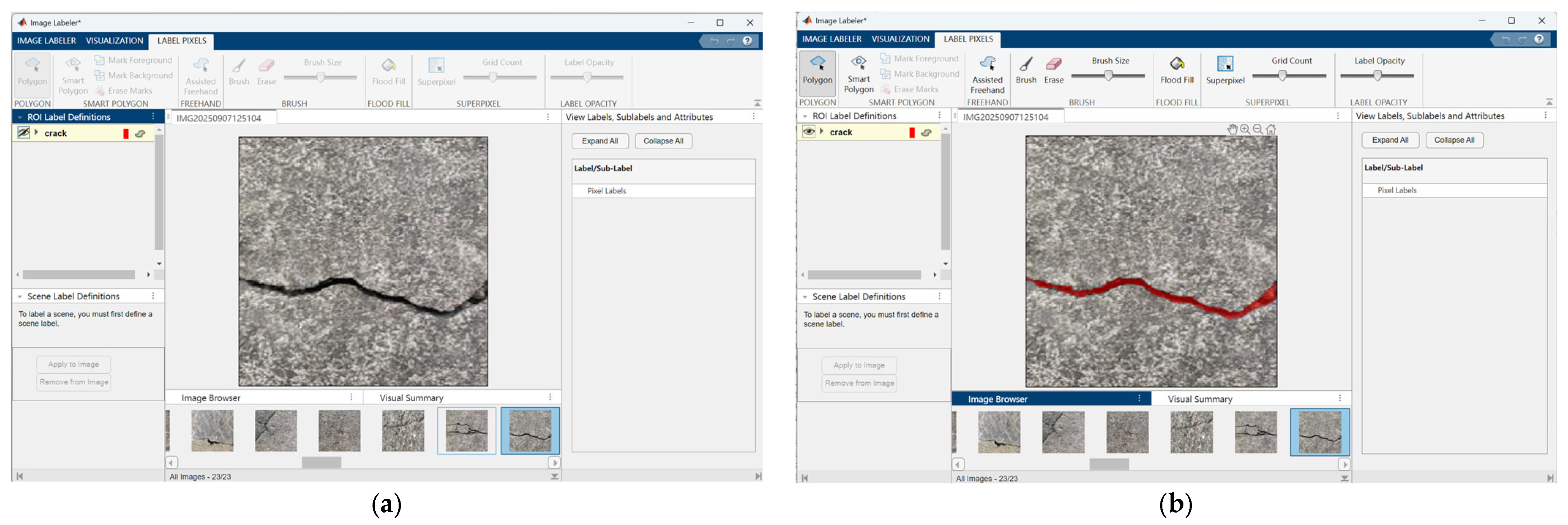

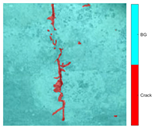

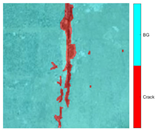

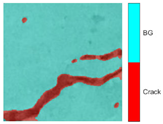

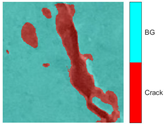

Figure 1 illustrates the image labeling process, presenting both the original and annotated images. Specifically,

Figure 1a displays an original textured image containing cracks; although the cracks are partially distinguishable within the complex background, they are not explicitly delineated. In contrast,

Figure 1b shows the annotated version produced using the pixel-level labeling tool, in which the crack regions are clearly highlighted in red. This enhanced visualization improves the prominence of the target cracks, thereby facilitating subsequent analysis and research efforts.

The cracks in the dataset are divided into three typical crack types on the tunnel inner surface: longitudinal cracks (accounting for 48% of the labeled samples), circumferential cracks (35%), and network cracks (17%).

To enhance the reliability of the results, we divided 4000 enhanced samples, of which 3200 were used for model training and 800 were used as an independent validation set specifically for verifying the generalization ability of the LiteSqueezeSeg model for unseen tunnel crack data.

2.2. LiteSqueezeSeg Network Model

Image semantic segmentation is a computer vision task that involves assigning precise category labels to every pixel within an image. In the context of crack detection in tunnel structures, achieving pixel-level accuracy necessitates that the model exhibits fine-grained discriminative capabilities at the boundaries between cracks and background regions. The LiteSqueezeSeg architecture employed in this study is a lightweight and efficient convolutional neural network (CNN). Compared to conventional large-scale semantic segmentation models such as Deeplabv3+ and Inceptionresnetv2, it has significantly fewer parameters, yet maintains competitive performance in crack segmentation tasks. This architecture effectively captures critical crack features—including texture and shape—enabling accurate differentiation between crack and non-crack pixels, thereby supporting reliable pixel-level detection in tunnel structural inspections.

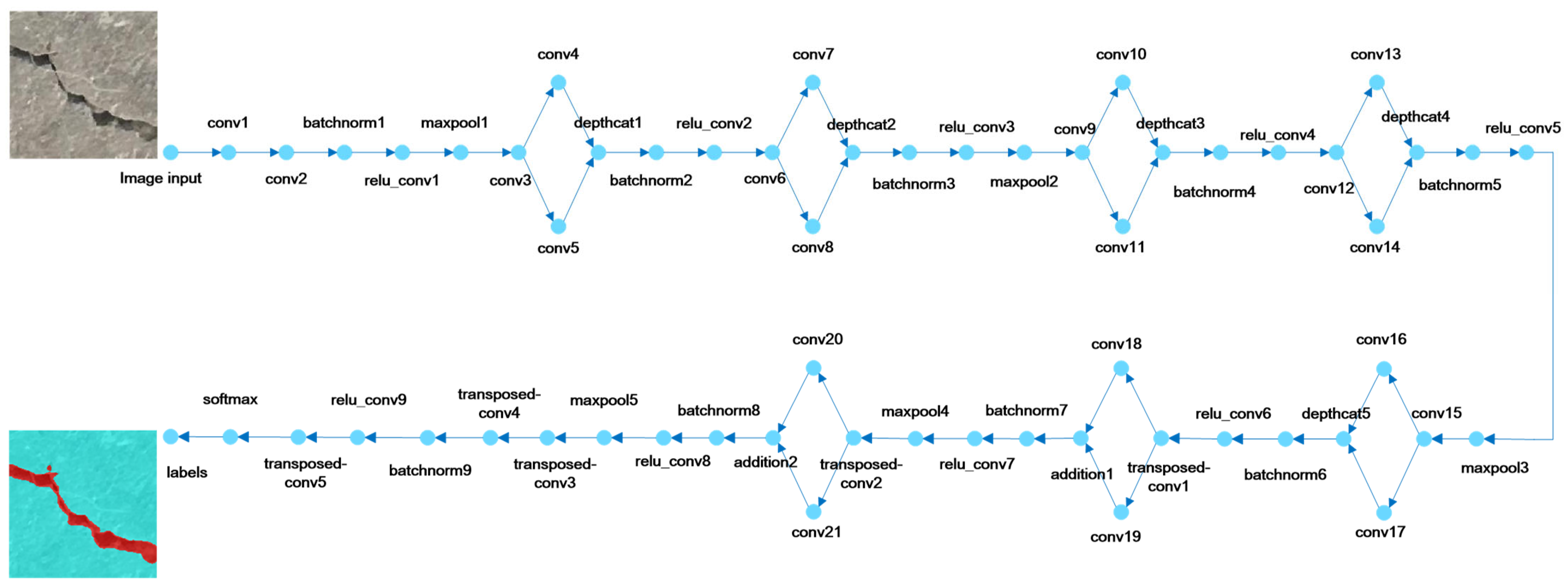

The network structure is illustrated in

Figure 2 and can be broadly divided into three stages: feature extraction, feature restoration, and classification. LiteSqueezeSeg is an enhanced deep neural network derived from SqueezeSeg, an open-source lightweight semantic segmentation model. Designed for crack recognition, it achieves high effectiveness with low computational overhead, making it suitable for deployment across diverse operational environments and applicable to crack identification, quantification, and segmentation tasks. In contrast, the original SqueezeNet architecture primarily consists of sequentially connected Fire Modules, where the encoder progressively reduces spatial resolution while increasing channel depth. Its decoder is relatively simplistic, typically employing transposed convolutions for direct upsampling; however, since the final output layer directly predicts the class map, certain architectural modifications are required to enable effective pixel-wise classification in deep network designs.

Building upon these foundations, LiteSqueezeSeg retains the parallel branching design of the Fire Module but adopts a more flexible configuration. On the one hand, it integrates an encoder–decoder framework with skip connections (inspired by U-Net), where the decoder performs multi-stage progressive upsampling; after each upsampling step, the generated feature map is element-wise fused with the corresponding feature map (matching spatial resolution) from the encoder pathway. On the other hand, LiteSqueezeSeg omits the rigid 1 × 1 squeezing step of the original SqueezeSeg while preserving SqueezeNet’s parallel branch structure—a targeted adjustment to the Fire Module that maximizes feature retention (avoiding spatial detail loss) without compromising lightweight performance or increasing computational complexity. This design integrates SqueezeNet’s efficient parallel convolutional branches with U-Net’s encoder–decoder architecture and element-wise addition fusion skip connections, achieving a balance between efficient computation and fine-grained segmentation, and thus overcoming the limitations of SqueezeSeg’s pure encoder design and U-Net’s high computational cost.

With the rapid advancement of deep learning technologies, crack detection approaches based on deep neural networks have increasingly demonstrated notable advantages. In particular, the LiteSqueezeSeg architecture has shown promising potential in the domain of crack detection. Given the critical role of crack morphology and width characteristics in structural health assessment, this study leverages the MATLAB Deep Learning Toolbox and the Deep Network Designer to develop a semantic segmentation model tailored for crack detection tasks using LiteSqueezeSeg. The proposed model not only effectively determines the presence of cracks in images but, more importantly, enables precise pixel-level localization and segmentation of crack regions. Experimental results indicate that the developed semantic segmentation network successfully reconstructs crack target areas, delivering high-quality pixel-level outputs that facilitate accurate measurement of crack geometric parameters—such as width and length—and support comprehensive structural health evaluation. In comparison with conventional crack detection methods, the proposed approach achieves comparable or superior detection accuracy while significantly enhancing model generalization and practical applicability. In terms of software configuration, this experiment was conducted using MATLAB on a Windows 11 operating system, with Deep Learning Designer serving as the primary deep learning framework. The LiteSqueezeSeg model employed in this study is an enhanced deep neural network architecture derived from the lightweight semantic segmentation model SqueezeSeg, capable of achieving high accuracy in crack recognition while maintaining low computational complexity.

2.3. Crack Recognition Effect Based on LiteSqueezeSeg Network Model

In the task of detection, the Intersection over Union (IoU) is adopted as the evaluation metric. This metric quantifies the degree of overlap between the predicted output and the ground truth, as defined in this study [

33]. Specifically, IoU is calculated as the ratio of the intersection area of the crack prediction and the ground truth to their union area in terms of pixels.

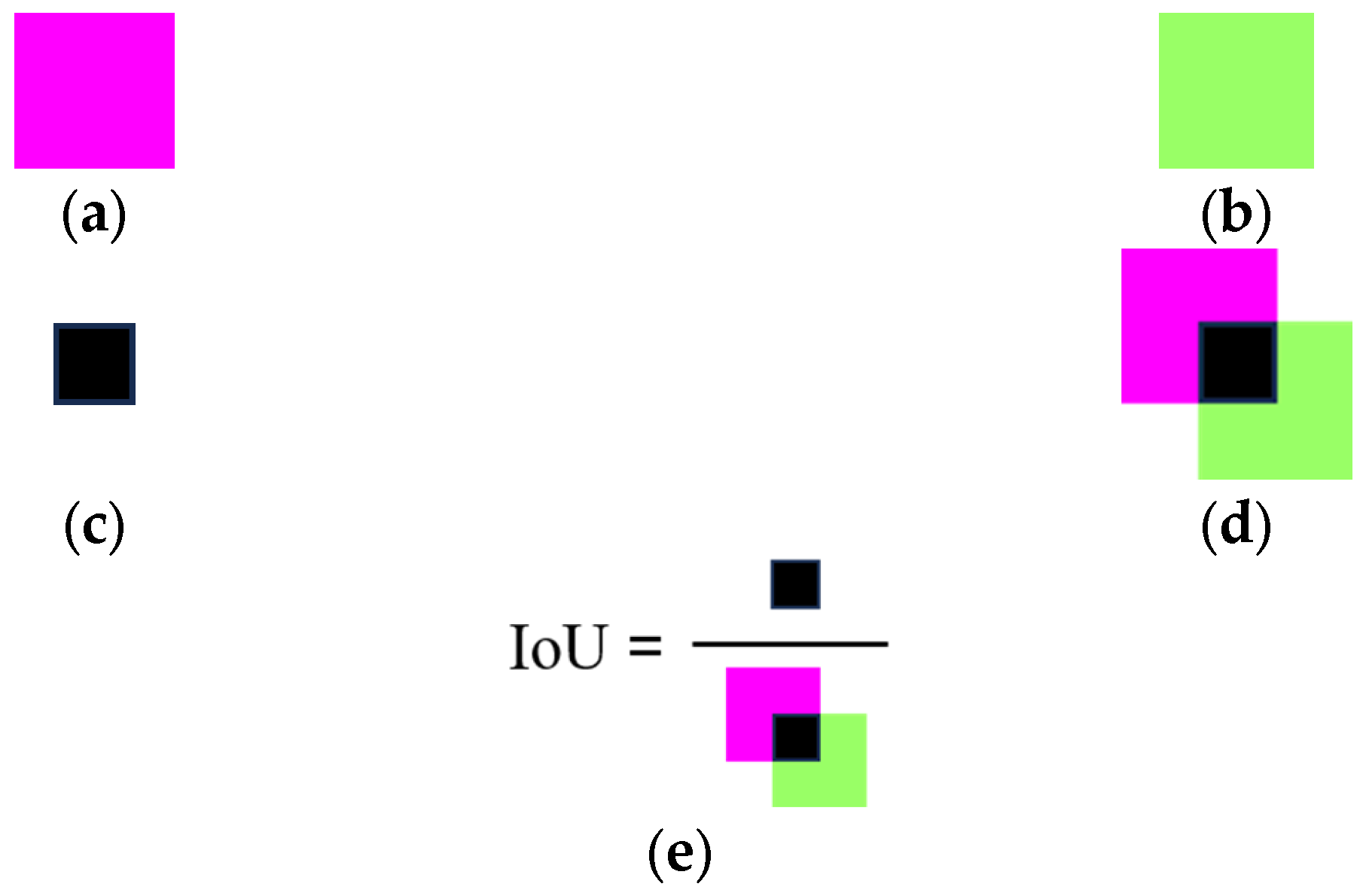

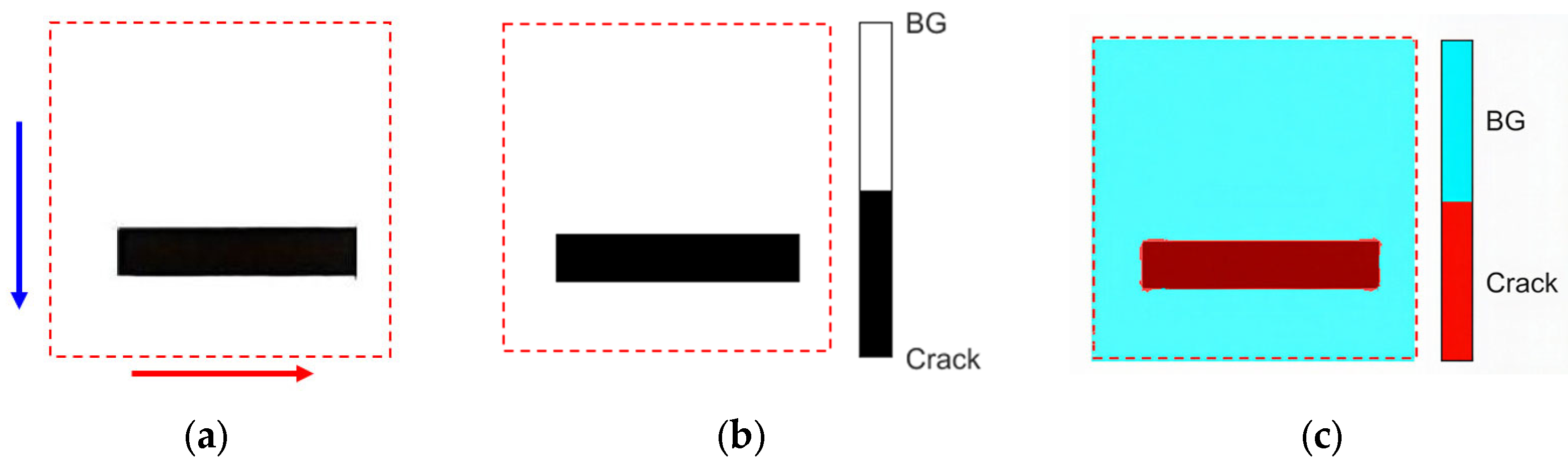

Figure 3 illustrates the conceptual definition of IoU:

Figure 3a depicts the pixels identified by the model (pink region);

Figure 3b represents the manually annotated pixels (green region);

Figure 3c highlights the overlapping pixels between the model-predicted and manually labeled regions (black region); and

Figure 3d displays the union of the two regions (comprising both pink and green areas). The formula presented in

Figure 3e formalizes IoU as the ratio of the intersecting pixel area to the total union pixel area. In this study, IoU serves as a quantitative measure of the spatial agreement between predicted crack segments and corresponding ground truth annotations. The IoU value ranges from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a higher degree of prediction accuracy.

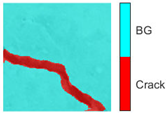

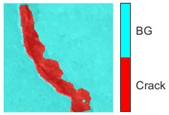

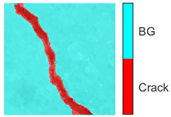

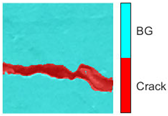

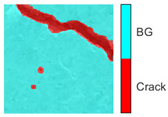

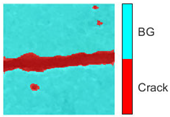

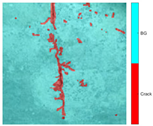

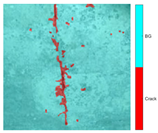

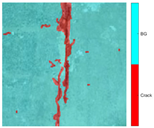

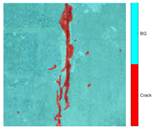

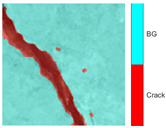

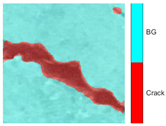

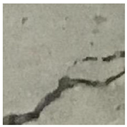

Table 1 presents the crack segmentation performance of the LiteSqueezeSeg model on representative images. The first column displays the original scene images containing cracks. The second column illustrates the model’s predicted segmentation, where cyan denotes the background (BG) and red indicates detected cracks (Crack). The third column shows manually annotated crack labels in black. The fourth column provides a visual comparison by overlaying the model’s predictions with the ground truth labels: magenta pixels represent false positives (crack predictions not matching the labels), green pixels indicate false negatives (labeled cracks not captured by the model), and black pixels denote true positives (overlapping regions between predictions and labels), thereby enabling an intuitive assessment of prediction accuracy. The fifth column quantifies the segmentation performance using the IoU metric, which measures the degree of overlap between predicted and actual crack regions. Higher IoU values correspond to greater segmentation accuracy. The reported IoU scores range from 0.72 to 0.84, reflecting the model’s robust and consistent performance in crack detection.

2.4. Performance Analysis Based on the LiteSqueezeSeg Network Model

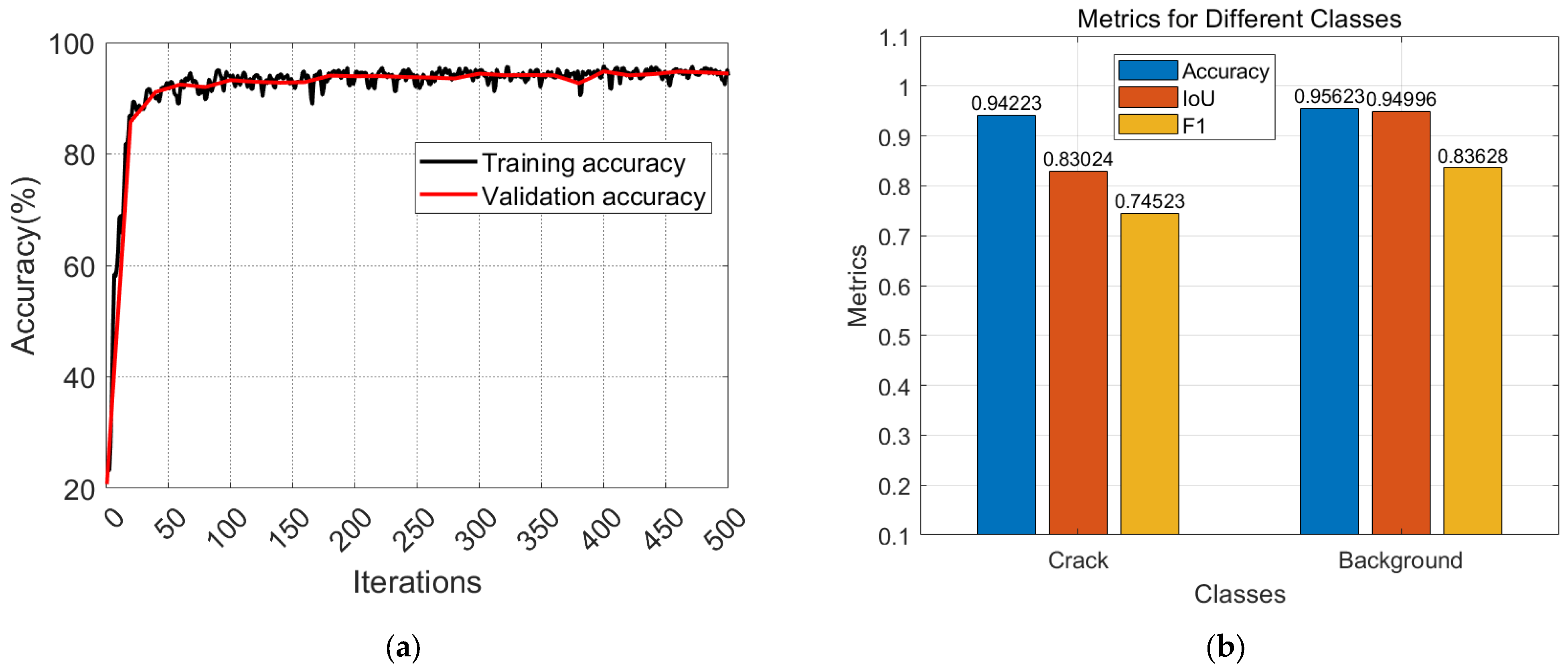

Figure 4 presents the training history and performance evaluation results of the LiteSqueezeSeg model. Specifically,

Figure 4a shows the training and validation histories with the training accuracy converging to approximately 95.15%. For the concrete structure crack identification task, Precision, Recall, and F1-score are the commonly used evaluation metrics [

34].

Accuracy refers to the proportion of correctly predicted positive and negative instances relative to the total number of instances, as defined by Equation (1):

where

TP denotes the number of true positives, representing cracks correctly identified;

TN denotes the number of true negatives, representing non-cracks correctly identified;

FP denotes the number of false positives, indicating non-cracks incorrectly classified as cracks; and

FN denotes the number of false negatives, referring to cracks that were missed during detection.

The accuracy rate is the proportion of the targets that are predicted as cracks among all the targets that are predicted as cracks, reflecting the model’s error detection ability. It mainly measures the degree of correct classification of the crack detection model for the tunnel entrance wall cracks. The calculation formula for the accuracy rate is Equation (2):

The recall rate is the proportion of the number of cracks that were correctly predicted among all the detected samples, reflecting the model’s ability to accurately detect cracks. The formula for calculating the recall rate is Equation (3):

The

F1 score is a comprehensive evaluation metric, which is the harmonic mean used to balance the accuracy and recall rates of crack detection. Generally, when the

F1 score is higher, it indicates that the model performance is better. The calculation formula for the

F1 score is as shown in Equation (4):

Figure 4b presents the quantitative evaluation results of crack and background regions in the test dataset across three core metrics:

Precision, IoU, and

F1 score, which serve as the primary criteria for benchmarking the segmentation performance of the model. Overall, the model exhibits significantly superior performance on the background class compared to the crack class across all three-evaluation metrics.

This phenomenon stems from two underlying aspects: on one hand, it is associated with the characteristics of crack pixels—their extremely low proportion and random distribution in the entire image; on the other hand, it is closely related to the morphological characteristics of cracks. Cracks typically feature narrow gaps and rough edges, which tend to be confused with noise and textures in the image. This substantially increases the risk of misclassifying such interferences as cracks, ultimately resulting in the model’s suboptimal performance across all evaluation metrics for the crack segmentation task.

The training results of the LiteSqueezeSeg model proposed in this study indicate that concrete cracks usually present as small-area distribution characteristics in images, and their spatial distribution is random. This characteristic leads to the model’s difficulty in correctly classifying minor interfering information such as voids and surface roughness points as crack targets during the segmentation process, thereby affecting the segmentation accuracy.

Table 2 presents the pixel count, total image pixel count, proportional frequency, and corresponding weight values for two categories, namely Crack and Background.

To mitigate the above class imbalance and misclassification issues, the model incorporates a class weight mechanism with the weight calculation Equation (5):

where

W represents the weight of either the crack or the background class; The “2” in the denominator is because this is a binary classification task (only two classes: crack and background);

fi denotes frequence,

i presents crack or background.

The weights are used to adjust the proportion of contributions of different classes in the loss function, with the core goal of increasing the proportion of the loss from low-frequency classes (e.g., cracks) in the total loss.

An exhaustive comparative analysis against contemporary state-of-the-art models is performed to highlight the superiority of our proposed architecture in lightweight design and high accuracy. The comparison parameters are shown in

Table 3:

The model achieves a remarkable balance between efficiency and performance: with only 3.4 million parameters (49% fewer than Mobilenetv2, 84% fewer than Resnet18, 89% fewer than U-Net, and 95% fewer than Inceptionresnetv2) and a latency of 16.33 ms (50% faster than Mobilenetv2, 11% faster than Resnet18, 59% faster than U-Net, and 85% faster than Inceptionresnetv2), it exhibits unparalleled lightweight characteristics. Meanwhile, our model maintains a high accuracy of 95.15%—surpassing Mobilenetv2 (94.71%) and Resnet18 (94.38%), and approaching the performance of U-Net (96.11%) and Inceptionresnetv2 (96.20%). Additionally, our model outperforms most counterparts in IoU and F1-score further demonstrating its superiority in comprehensive task performance. In summary, this model stands out as a lightweight yet high-performance solution, outcompeting existing architectures in efficiency while delivering competitive accuracy.

To verify the practical effectiveness of the proposed model in the real-world task of identifying cracks in tunnels,

Table 4 presents the image semantic segmentation results of MobileNetv2, Inceptionresnetv2, and LiteSqueezeSeg in complex tunnel scenarios (where the original images contain typical interference factors such as stains and texture disturb-ances). The experimental visualization results show that in such challenging environ-ments, the denoising ability and crack target recognition accuracy of our model are significantly better than those of MobileNetv2. Although its crack recognition accuracy is slightly lower than that of Inceptionresnetv2, LiteSqueezeSeg has a clear advantage in terms of parameter quantity, making it more suitable for deployment in tunnel scenarios.

Experimental results show that this mechanism effectively balances the training weights of crack and background classes, achieving a more balanced accuracy rate (ACC) for both classes, significantly reducing the risk of misclassification caused by minor interference and improving the reliability of the model’s recognition of crack targets.

4. Crack Warning Grading

The construction period of tunnels is long and the investment is large. The service life of the tunnels directly affects the long-term benefits of the infrastructure. Cracks are common diseases in tunnel structures. If not promptly warned and controlled, they will accelerate the erosion of the structure by environmental factors. Grading warning provides tunnel maintenance personnel with the health status of the tunnel at different risk stages, ensuring that they can take targeted intervention measures in time, effectively preventing the expansion of cracks and the deterioration of diseases, delaying the aging speed of the tunnel structure, and ensuring that the tunnel continues to perform core functions such as transportation and water conservancy within the designed service period, and guaranteeing the long-term stable performance of the tunnel.

In the field of tunnel engineering, the cracking and displacement of tunnel linings are important indicators for evaluating the structural safety of the tunnels. According to the Technical Specifications for Prevention of Cracks in Railway Tunnel Linings TB/T 2820.2-1997), the evaluation criteria for crack and displacement of the lining are shown in

Table 7.

Where Grade C (medium) cracks are defined as those with a length of less than 5 m and a width of less than 3 mm. Such cracks indicate a relatively minor level of structural damage and have negligible effects on the overall integrity of the tunnel structure. As stipulated in the relevant standards, Grade C defects require enhanced monitoring but do not necessitate structural reinforcement.

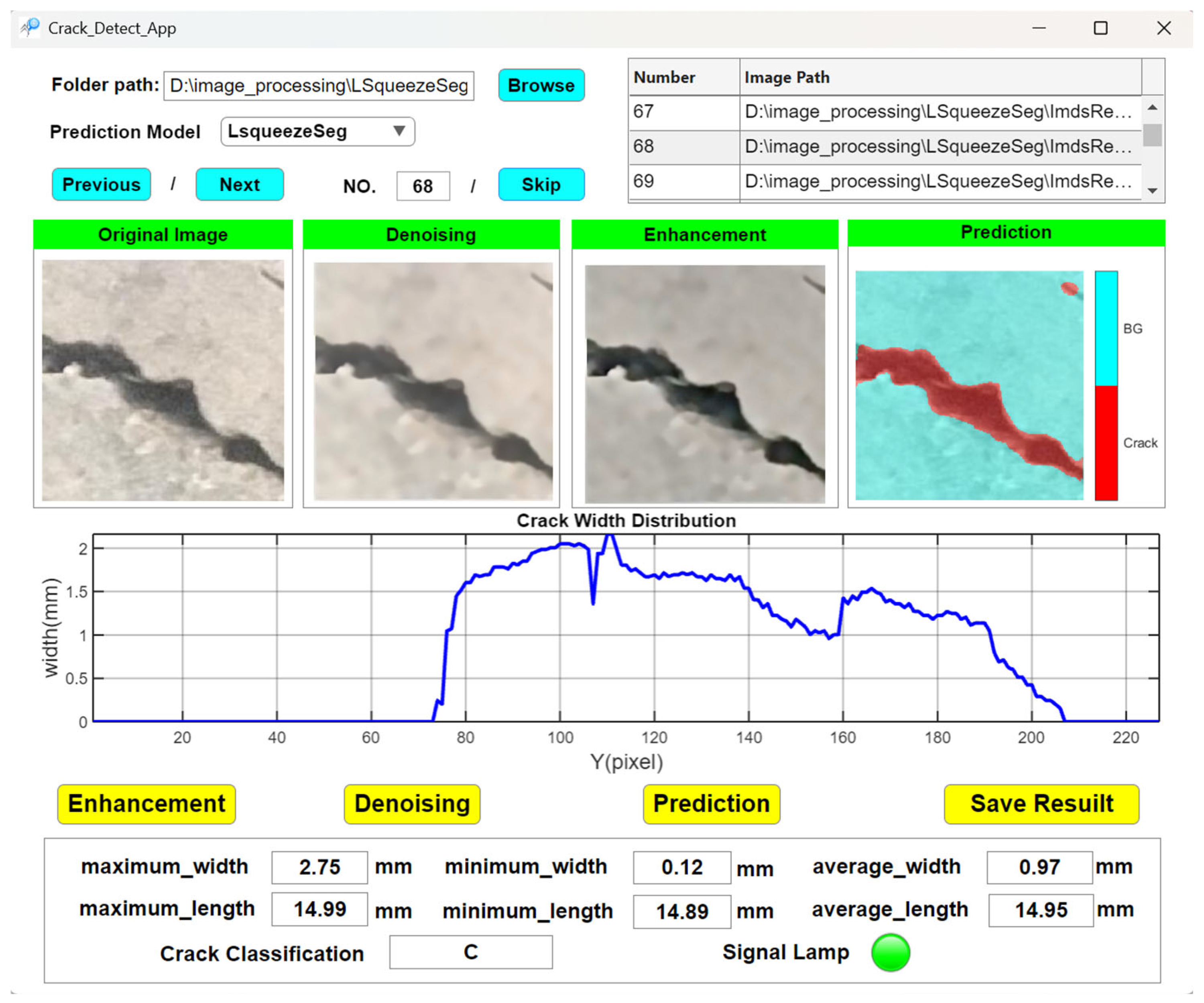

Based on the quantitative identification and analysis of cracks, this study has developed a specialized software system capable of automatically detecting and measuring crack dimensions. The software interface is shown in

Figure 11. In tunnel lining inspection, the system can accurately determine key geometric parameters such as crack length and width. According to the crack classification criteria specified in the TB/T 2820.21997 standard, cracks with a width of less than 3 mm are classified as Grade C defects. This result aligns with the defect classification system stipulated in relevant tunnel engineering standards, where Grade C defects have the least adverse impact on the tunnel structure and typically do not require structural reinforcement. Instead, dynamic control can be effectively maintained through enhanced monitoring. This indicates that the software system developed in this study can accurately identify and classify the severity of tunnel lining crack deterioration in accordance with current engineering standards, providing reliable technical support for the efficient and accurate assessment of tunnel lining structural conditions. Therefore, the system holds significant practical value for engineering applications.

The system’s identification and quantification modules work in synergy to support a comprehensive workflow encompassing automatic crack detection, geometric parameter measurement (e.g., maximum, minimum, and average width), and condition grading. Measurement results can be exported in the form of Excel files or image reports, facilitating subsequent condition assessment and informed maintenance decisions in practical engineering applications.

The software integrates identification and quantitative analysis modules, enabling a seamless workflow from automatic crack detection to quantitative measurement of crack parameters and subsequent condition assessment. It serves as an efficient tool for the rapid detection and scientific evaluation of tunnel lining cracks.

5. Discussion

This study focuses on the accurate mapping between pixel and physical dimensions for tunnel crack detection tasks and the optimization of lightweight segmentation models, verifying the effectiveness of the LiteSqueezeSeg model in crack recognition tasks as well as the reliability of the dimension conversion method combining camera calibration with laser ranging. However, there remain research directions that can be further expanded and deepened:

First, future research will expand the sample dataset for in-tunnel scenarios to address the issues of single-scene distribution and uneven sample distribution in the current dataset, thereby enhancing the model’s adaptability to complex in-tunnel environments.

Second, subsequent work will supplement refined annotations of Ground Sampling Distance (GSD) parameters, and integrate engineering parameters such as tunnel cross-sectional dimensions and shooting distance to further improve the quantitative system for pixel-physical dimension conversion.

Furthermore, future research will integrate public tunnel crack datasets with the self-constructed dataset developed in this study to conduct cross-dataset cross-validation. This approach aims to verify the model’s performance stability under different acquisition devices and tunnel environmental operating conditions, as well as to further evaluate its domain generalization capability.