4.3. Multiclass Metrics

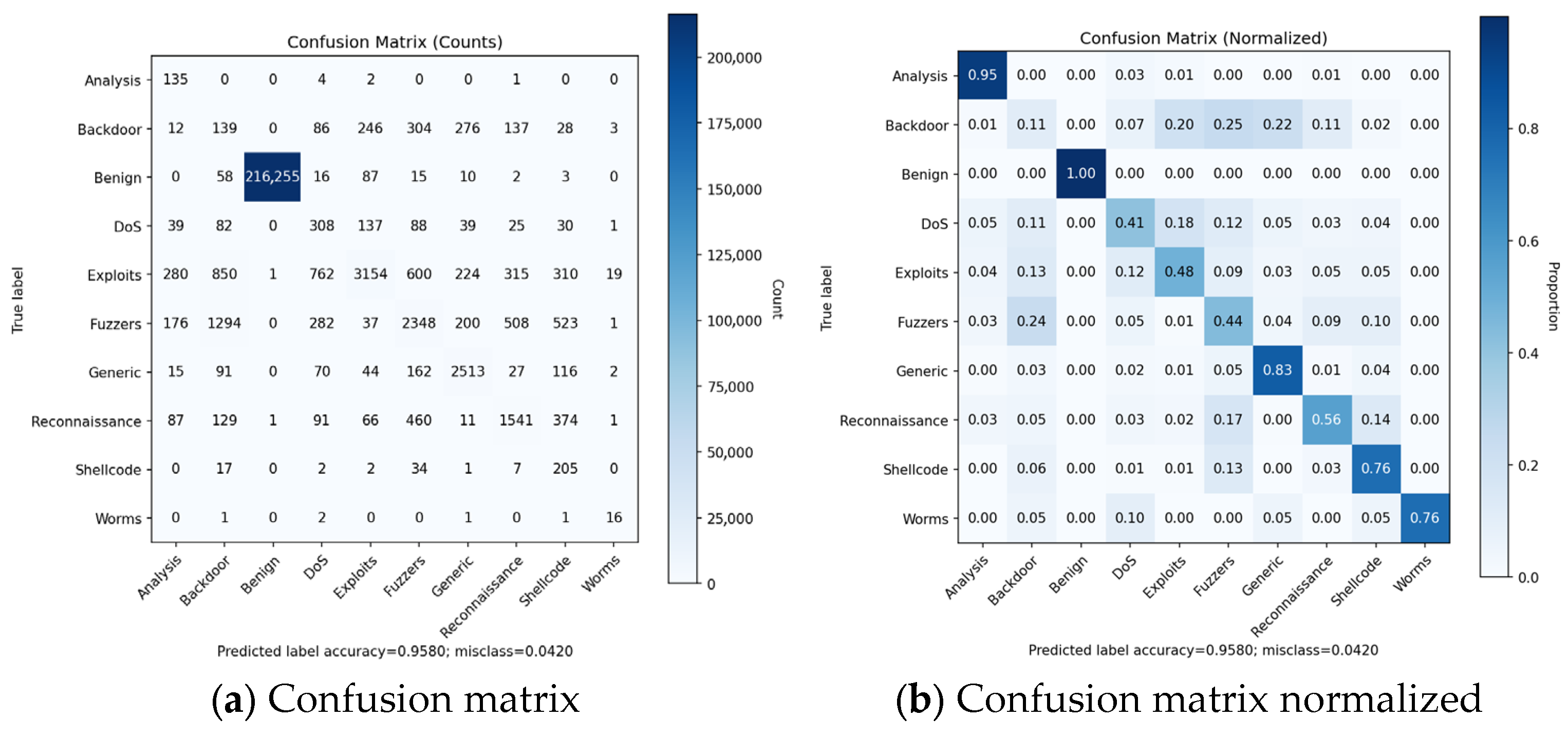

On the NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 the confusion matrix and derived metrics show a clear split between classes that the model learns reliably and those for which performance is substantially weaker (

Figure 7). Benign traffic dominates the dataset, and the model achieves excellent detection for this class (Precision = 1.00, Recall = 0.999, FAR = 0.0), which is expected due to heavy class imbalance and highly separable feature profile.

For the attack classes Backdoor, Shellcode, Analysis, and Worms model, precision is low (0.052–0.372), as seen in

Table 6, indicating a high rate of false positives. This is consistent with their extremely small sample counts in the dataset, which limits the model’s ability to learn class-specific patterns from similar attack categories, such as Backdoor being misclassified as Fuzzers or Exploits. These classes also exhibit the highest FPR (Backdoor FAR = 0.011, Fuzzers FAR = 0.007, and Shellcode FAR = 0.006), and the model incorrectly assigns Benign or other attack flows to these categories. Classes with moderate frequency and structured behavioral signatures Generic, Reconnaissance, and Exploits show a more balanced performance. For example, Generic achieves the highest F1 of 0.796 among attack classes and a low FAR of 0.003, with Reconnaissance and Exploits indicating partial but not complete separation from neighboring classes. Their corresponding FPR values 0.004 and 0.003 suggest that FP is kept constrained.

For DoS and Fuzzers, Recall remains limited (0.411 and 0.437) and their FAR is higher (0.006 and 0.007) than in other classes. This follows from both their internal heterogeneity and high overlap in byte/packet-rate statistics with Exploits and Generic classes. The model consistently confuses high-volume bursts across these classes. Across all attack types, the macro-F1 of 0.484 highlights the gap between overall Accuracy (dominated by Benign) and the model’s ability to accurately classify minority attack categories. The macro-FPR of 0.004 demonstrates that even though global FP are low, mentioned attack classes exhibit misclassification into other attack types, driven by dataset imbalance and overlapping feature distributions.

Figure 8 shows FPR for all classes.

The normalized confusion matrix translates those figures into Recall, while the model ranks nearly all classes well (as seen on ROC curve on

Figure 9a). Exploits and DoS have the lowest Recall, with errors primarily in Backdoor, Fuzzers, and Shellcode. Despite that, the ROC curves are uniformly high, with micro-average AUC = 0.999. The conclusion is that even difficult classes can be separated with very low FP rates. This indicates residual errors in the confusion matrix come from the temporal validation rather than a lack of discriminative signal.

The Precision–Recall plot (

Figure 9b) demonstrates class imbalance. The micro-average AP is 0.991 reflects the dominance of Benign and excellent precision. While Exploits, Generic, Reconnaissance achieve a high average precision that is consistent with their strong AUCs. Backdoor and DoS with low precision demonstrate their observed confusions into neighboring traffic types. The very low AP for Backdoor indicates high false positives, particularly from Fuzzers. DoS exhibits a similar pattern with confusion to Fuzzers and Shellcode.

While confusion matrices and ROC curves show that the model separates most attack classes effectively, the macro-F1 and per-class PR metrics highlight weaknesses for Backdoor, DoS, and Fuzzers. These classes are rare in NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 and display substantial intra-class variability, producing overlapping flow signatures with higher-frequency attacks and that limit their discriminability and class separation. To better understand this, we examined class-wise PR curves and observed that these classes require substantially different operating thresholds to balance precision and recall. While full threshold calibration lies outside the scope of this study, the curves indicate that per-class thresholding could meaningfully improve recall for rare attacks without inflating false positives across the remaining classes. This context clarifies that the observed performance gaps reflect dataset-driven constraints rather than a specific deficiency of the temporal GNN formulation.

Our model separates classes in the NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 dataset extremely well in a ranking sense, but the performance suffers under the heavy imbalance. The confusion matrix shows where mistakes prevail, while the PR curves quantify the precision cost of pursuing a higher recall on these rare classes. These views together justify the use of class-aware threshold calibration if recall on Exploits and DoS must be raised, and they also motivate targeted future and graph refinements for Backdoor to reduce its false positives without eroding precision in neighboring classes.

4.4. SHAP Feature Importance

The errors across classes observed in the confusion matrix align closely with the SHAP feature importance patterns, shown in

Figure 10. For the classes with the weakest performance such as Backdoor, DoS, and Fuzzers, SHAP reveals that their feature signatures are not strongly differentiated from other high-volume or burst-pattern attack classes. These classes exhibit broad distributions across byte-based and packet-based metrics (e.g., OUT_BYTES, IN_PKTS, SRC_TO_DST_SECOND_BYTES), indicating that the GNN does not identify a dominant, class-specific marker. This lack of distinctive flow-level patterns corresponds directly to their high FPRs (Backdoor FAR = 0.011, DoS FAR = 0.006, Fuzzers FAR = 0.007), where flows from these minority classes are frequently absorbed into more volumetric classes such as Exploits or Generic. Attack types with clear SHAP peaks on protocol features, Reconnaissance (DNS query types), Shellcode (ICMP codes), and Generic (with consistent TTL ranges), achieve significantly better F1 and lower FAR. Spider chart shows sharp spikes for these classes in features like DNS_QUERY_TYPE_255, ICMP_IPV4_TYPE_2, and TTL metrics, reflecting stable behavioral signatures that the GNN reliably captures. This explains their comparatively higher discriminability despite the dataset imbalance.

Backdoor and Analysis with their slightly higher FPR (FAR of 0.052 and 0.181) show no unique SHAP-dominant features. Their signatures largely overlap with multiple attack classes, especially those shaped by high-volume or mixed-protocol patterns. The SHAP plot reveals that these classes lack distinctive markers on both protocol categories and packet-size distributions, resulting in misclassification.

Finally, classes with moderate recall but moderate precision (such as Worms) show SHAP signatures are dominated by a small subset of features (specific ICMP types), suggesting that the GNN identifies their behavior only when these rare indicators are present. This explains high recall (0.762 for Worms) paired with the moderate precision of 0.372 where the model recognizes distinctive spikes but struggles when flows deviate from these forms.

In contrast, attack classes with clear SHAP peaks on protocol specific features, such as Reconnaissance, Shellcode (L7_PROTO types), and Generic (DNS type), achieve significantly better F1 and lower FAR. The spider chart shows sharp spikes for these classes in fields like DNS_QUERY_TYPE_255 and L7_PROTO, reflecting stable behavioral signatures that the GNN captures. This explains their comparatively higher discriminability despite the dataset imbalance. This is further seen per each class in

Figure 11a–j.

Although it is informative of what features are important for predictions for the specific class, Figure provide insight on potential problems in the detection of classes that are overlapping in specific features. To understand the reason behind such behavior, separate analysis is needed to understand what drives its predictions.

Results on

Figure 11a–j provide additional information on what shared predictors drive model confusion. The Backdoor SHAP plot shows that the top features L7_PROTO_37.0, SRC_TO_DST_IAT_AVG, DST_TO_SRC_IAT_AVG (inter-arrival time averages), SRC_TO_DST_AVG_THROUGHPUT, and MIN_TTL are not Backdoor specific within NF-UNSW-NB15-v3. Inter-arrival based metrics and throughput summaries appear across many attack classes (e.g., Exploits and Fuzzers), giving Backdoor a feature signature with no dominant discriminator. As a result, the GNN often assigns flows with protocol 37 to Backdoor, leading to systemic false positives. This matches the confusion matrix, where Backdoor predictions spread over many unrelated classes. For DoS, SHAP identifies MIN_TTL, MAX_TTL, L7_PROTO_37.0, and SHORTEST_FLOW_PKT as the strongest contributors. These TTL-based features are common across multiple high-volume classes, including Generic and Exploits, and do not indicate DoS uniquely. The model therefore misses many normal or Exploits-like flows with odd TTL ranges to DoS, explaining the elevated FP rate. The lack of DoS-specific indicators (sustained packet flooding patterns, consistent throughput spikes) in the dataset further weakens this class’s separability.

Fuzzers shows SHAP peaks at MAX_TTL, MIN_TTL, L7_PROTO_37.0, L7_PROTO_13.0, DST_TO_SRC_AVG_THROUGHPUT, and SRC_TO_DST_SECOND_BYTES. This signature overlaps with Exploits, Generic, and DoS flows. TTL instability and protocol-categories dominate the attribution, making the model sensitive to benign protocol variations and causing normal traffic with uncommon TTL and protocol combinations to be mislabeled as Fuzzers. In all three high-FPR classes, SHAP reveals broad, non-distinctive feature profiles, dominated by generic TTL irregularities, protocol-category (L7_PROTO_*), and basic throughput or inter-arrival statistics.

Because these signals are shared across multiple attack classes and even some benign traffic, the GNN lacks precise decision boundaries, leading to systematic false positives. The model correctly amplifies discriminative features when they exist (e.g., DNS types for Reconnaissance, ICMP types for Shellcode), but for Backdoor, DoS, and Fuzzers the dataset does not provide sufficiently unique patterns, which is directly reflected in the SHAP distributions.

The global signed SHAP, seen in

Figure 12a–j, show how contribution characteristics influence predictions. Fuzzers and Backdoors exhibit a negative contribution in NUM_PKTS_1024_TO_1514_BYTES feature whose contribution decreases the class score, while other classes provide insight consistent with mean SHAP.

In the SHAP summary heatmap, shown in

Figure 13, columns are normalized per feature, so each column aggregates the relative evidence that a single feature provides across classes. Red cells mark the class for which that feature contributes the most to our TE-G-SAGE model decision, while blue indicates a minimal contribution. The cell values represent the mean absolute SHAP magnitude (|SHAP|), capturing the strength of a feature’s influence but not its direction (i.e., whether it pushes probability toward or away from a class). Interpreted this way, columns with a single intense red band reveal better class separation, whereas columns with several warm rows indicate shared cues across classes, which is a likely source of confusion at any fixed operating threshold and a plausible explanation for the cross-class errors observed in the confusion matrix.

4.5. Comparison with Other Models

On the NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 temporal test window, XGBoost attains the highest accuracy and F1, driven by the best precision among the three models, whereas our TE-G-SAGE achieves the highest recall (

Table 7). GCN underperforms on all class-aware metrics. Given the strong class imbalance and the dominance of Benign flows, the small spread in accuracy across models is expected. The more discriminative signals are the class-aware metrics (precision, recall, F1). The pattern indicates a classic precision–recall trade-off: TE-G-SAGE recovers more true attacks (highest recall) at the expense of more false alarms (lower precision), while XGBoost is more conservative (higher precision) but misses more attacks (lower recall). GCN is the worst performing, with both low precision and low recall, yielding the lowest F1. All models achieve excellent results. XGBoost is strongest on average AUC, while our TE-G-SAGE remains competitive on Fuzzers, Shellcode, Worms, and DoS (e.g., Worms 0.998, Shellcode 0.992 and DoS 0.979), but shows the widest gap on Backdoor with 0.929. Taken with the earlier findings, TE-G-SAGE has slightly lower AUCs on the hardest classes but still demonstrates a strong ranking, consistent with its recall advantage under chronological evaluation.

The edge-aware TE-G-SAGE aggregates relational context with two-hop neighborhoods and detects attack patterns that manifest across connections, e.g., distributed scans, DoS fan-outs, or multi-stage exploits, raising the probability of hitting true positives in rare classes. This relational sensitivity explains the higher recall. At the same time, several attack classes share the same high-leverage features (TTL, L7 protocols), as seen in the SHAP heatmaps. Our model message passing can amplify these signals, increasing cross-class confusion (e.g., between Exploits, Fuzzers, Backdoor, and DoS) and thereby lowering precision and F1. TE-G-SAGE trades more detections for more false alarms that is often desirable in analyst-in-the-loop settings where missed attacks are costlier than triaging extra alerts.

The GCN baseline is less aligned with our inductive, temporal setting and, in this configuration, makes weaker use of edge features than TE-G-SAGE. Its stronger tendency toward oversmoothing and the mismatch with the temporal split (new nodes/edges at test time) reduce both precision and recall, which translates to the lowest F1 despite competitive accuracy on benign-heavy data.

The confusion matrices and PR curves explain where the losses accumulate. Classes whose top-ranked features are shared remain entangled at the operating point, yielding lower precision for TE-G-SAGE. Classes with unique features (Generic through DNS type 255, Worms through ICMP codes, Shellcode through retransmissions) are separated more cleanly in both models. The high one-versus-rest ROC AUCs observed earlier imply that thresholding, not lack of separability, is the main driver of the precision and recall differences.

Our baseline choices XGBoost and GCN were selected to isolate the contribution of modeling NetFlow as a temporal, edge-aware graph. XGBoost represents a competitive non-graph learner that fully exploits engineered flow features, whereas GCN provides a graph baseline without edge attributes, illustrating the effect of incorporating flow-level information. More advanced GNN-IDS architectures would shift the focus away from our core objective: establishing a transparent, temporally faithful, inductive model with Shapley-value explanations. We therefore highlight advanced architectures such as TCG-IDS, E-ResGAT, and DLGNN as promising avenues for future work rather than direct baselines. Overall, the analysis emphasizes that minority-class limitations arise primarily from dataset characteristics and that temporal, edge-aware GNNs paired with SHAP offer a practical and interpretable foundation for flow-based intrusion detection.

4.6. Time Complexity

Time complexity per epoch and mini-batch edge classification with our model is dominated by neighbor aggregation and number of edges being sampled for each node (

Table 8). For a batch of

B seed edges, neighbor sampling builds a

K-hop subgraph with

Nk nodes at layer k dependent to a batch B and product of fan-outs

F. The edge classifier operates only on the

B seed edges which costs

per batch. Reading edge features adds an I/O cost

, which is linear in batch size for fixed

K, fan-outs

Fk, and hidden size

h. Overall time complexity per epoch is shown in

Table 9.

Memory usage is , proportional to the size of the sampled subgraph rather than to the full graph, which is the main benefit of mini-batch TE-G-SAGE compared to full-batch message passing.

Training and validation time scale predictably with graph size (

Figure 14), reflecting the cost of neighborhood sampling and message passing in our two-hop model. As the number of nodes increases from roughly 25% to 75% of the full NetFlow graph, total training time grows almost linearly, consistent with the expected

dependence of mini-batch where fan-outs dominate per-batch cost. Validation exhibits a steeper slope because it processes each batch without gradient optimization and uses full-window inference. This empirical trend confirms that the model maintains scalable behavior under increasing temporal windows, indicating that neighborhood sampling successfully bounds computational cost even in large NetFlow graphs.