Numerical Simulation and Structural Optimization of Multi-Stage Separation Devices for Gas-Liquid Foam Flow in Gas Fields

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Models and Boundary Conditions

2.1. Interface Tracking and Multiphase Flow Solution (The VOF Model)

2.2. Population Balance Model (The PBM Model)

2.3. Euler Liquid Film Model

2.4. Solution Strategy and Inter-Model Coupling

- Flow Solution (VOF): In each time step, the solver first updates the flow field (velocity, pressure) and phase distribution (volume fraction) by solving the coupled VOF equations (Equations (1)–(6)).

- Bubble Dynamics (PBM): The updated flow field provides local parameters (e.g., turbulent dissipation rate) to the PBM. The PBM then solves its transport equation (Equation (7)) to update the bubble size distribution due to coalescence and breakup.

- Data Feedback: The new bubble size distribution from the PBM is used to calculate updated mixture properties (e.g., effective viscosity and density), which are fed back into the momentum equation (Equation (2)) for the next iteration/time step.

- Liquid Film Interaction: Concurrently, the Eulerian Liquid Film model interacts with the VOF model at the walls. Mass and momentum are transferred as source terms between the core flow (VOF domain) and the wall film (governed by Equations (8) and (9)) based on droplet impingement and film stripping events.

2.5. Model Assumptions and Limitations

3. Physical Model and Structural Optimization of the Separator

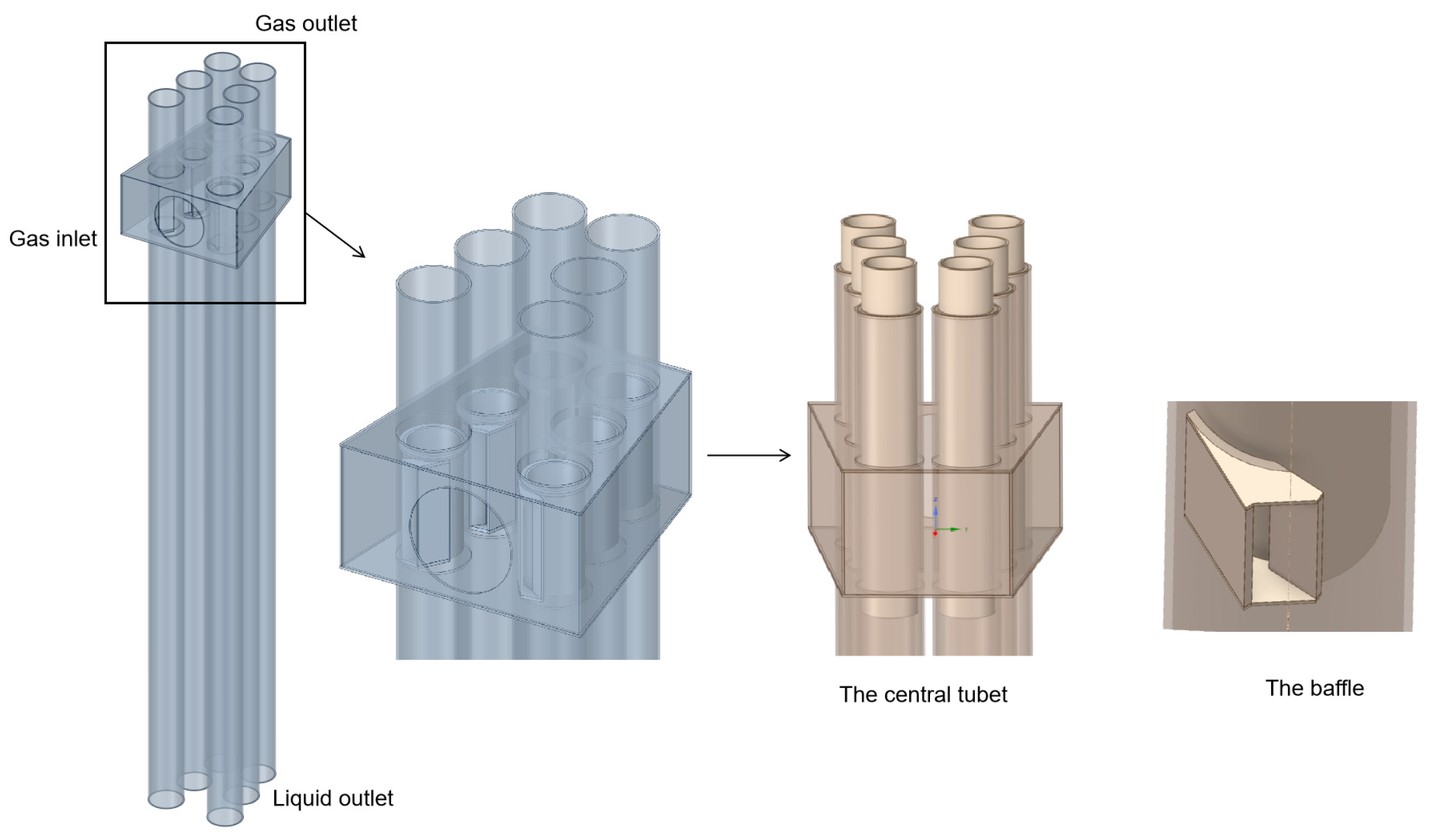

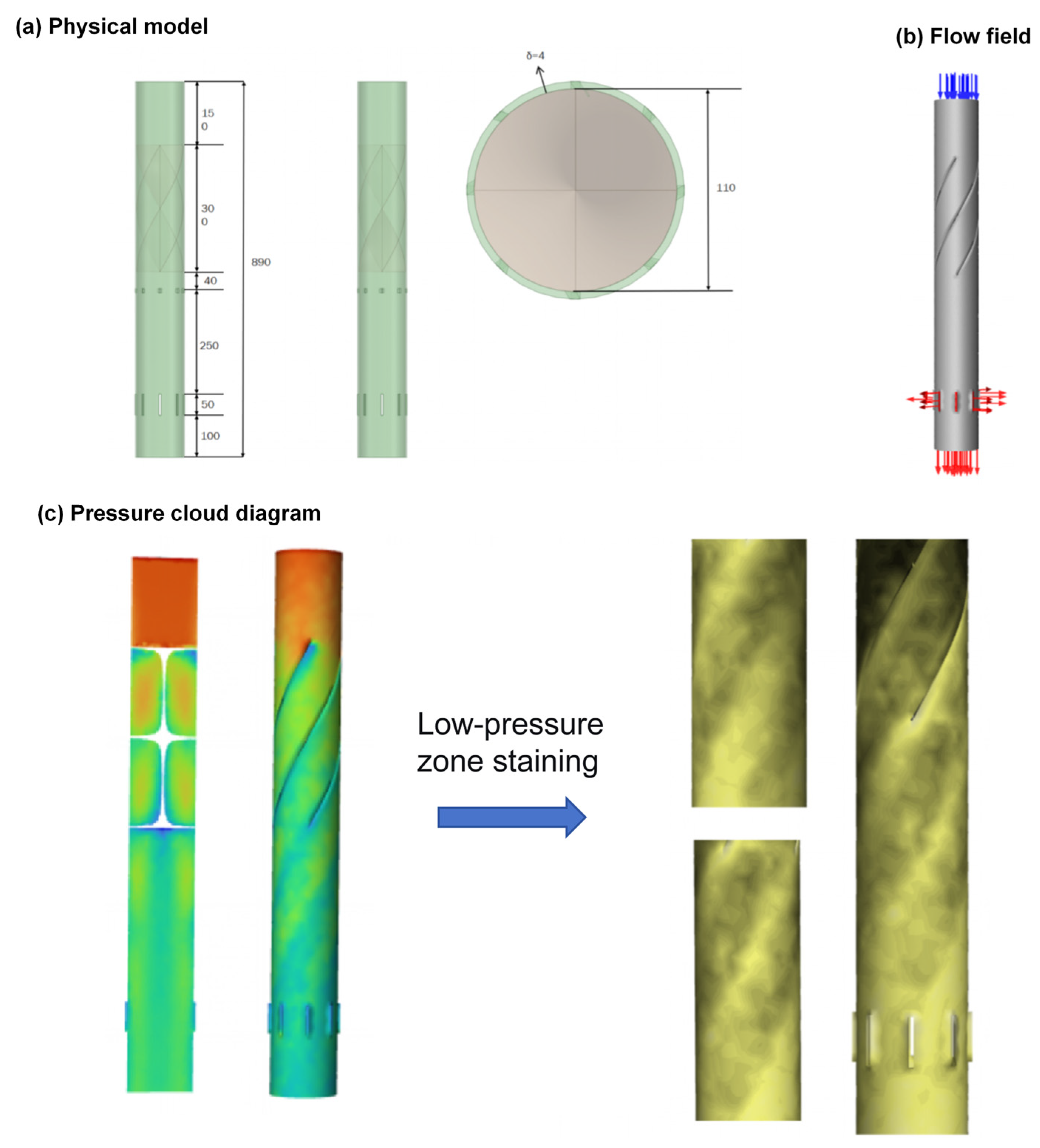

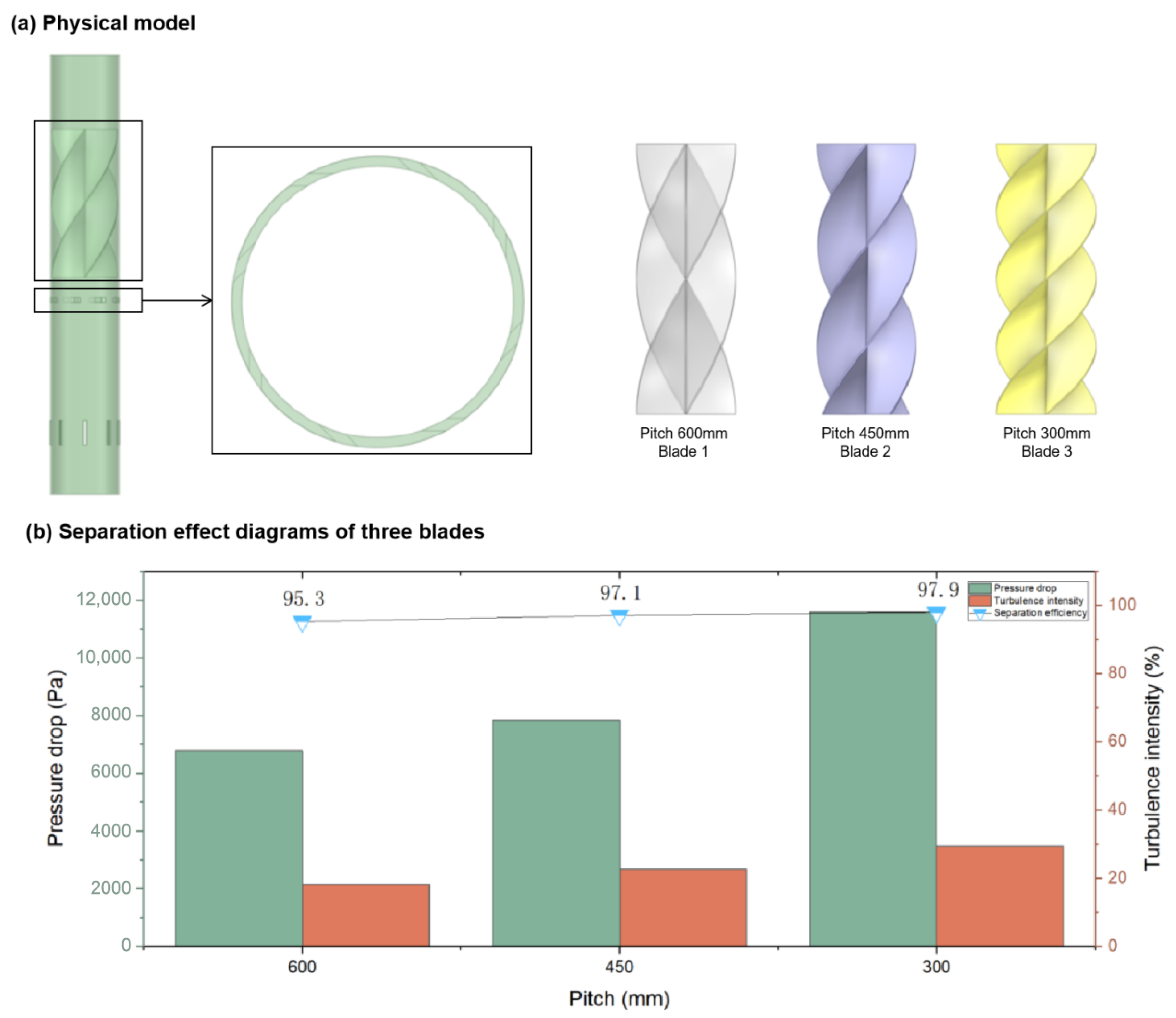

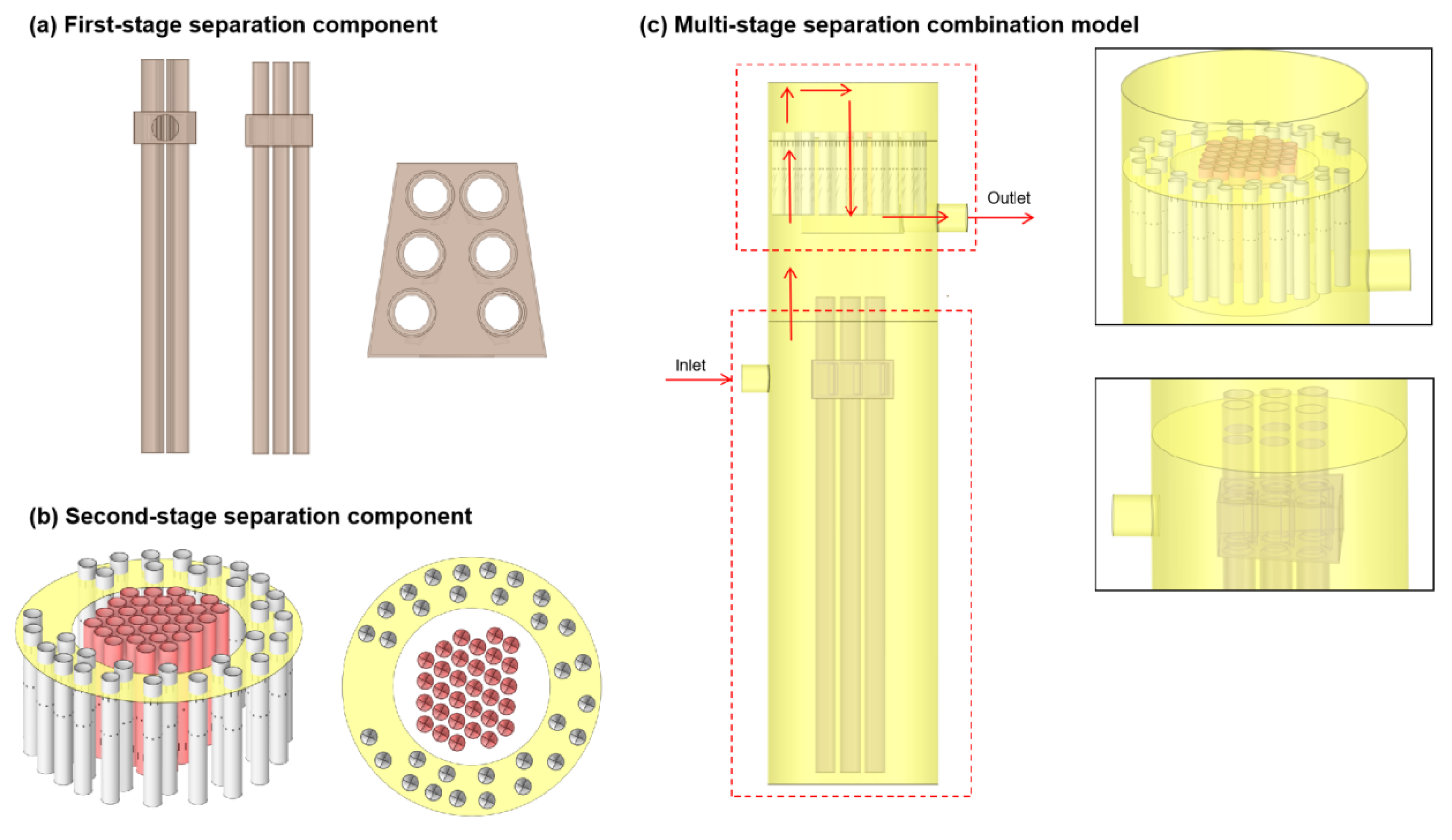

3.1. First-Stage Separation Cyclonic Defoaming Components

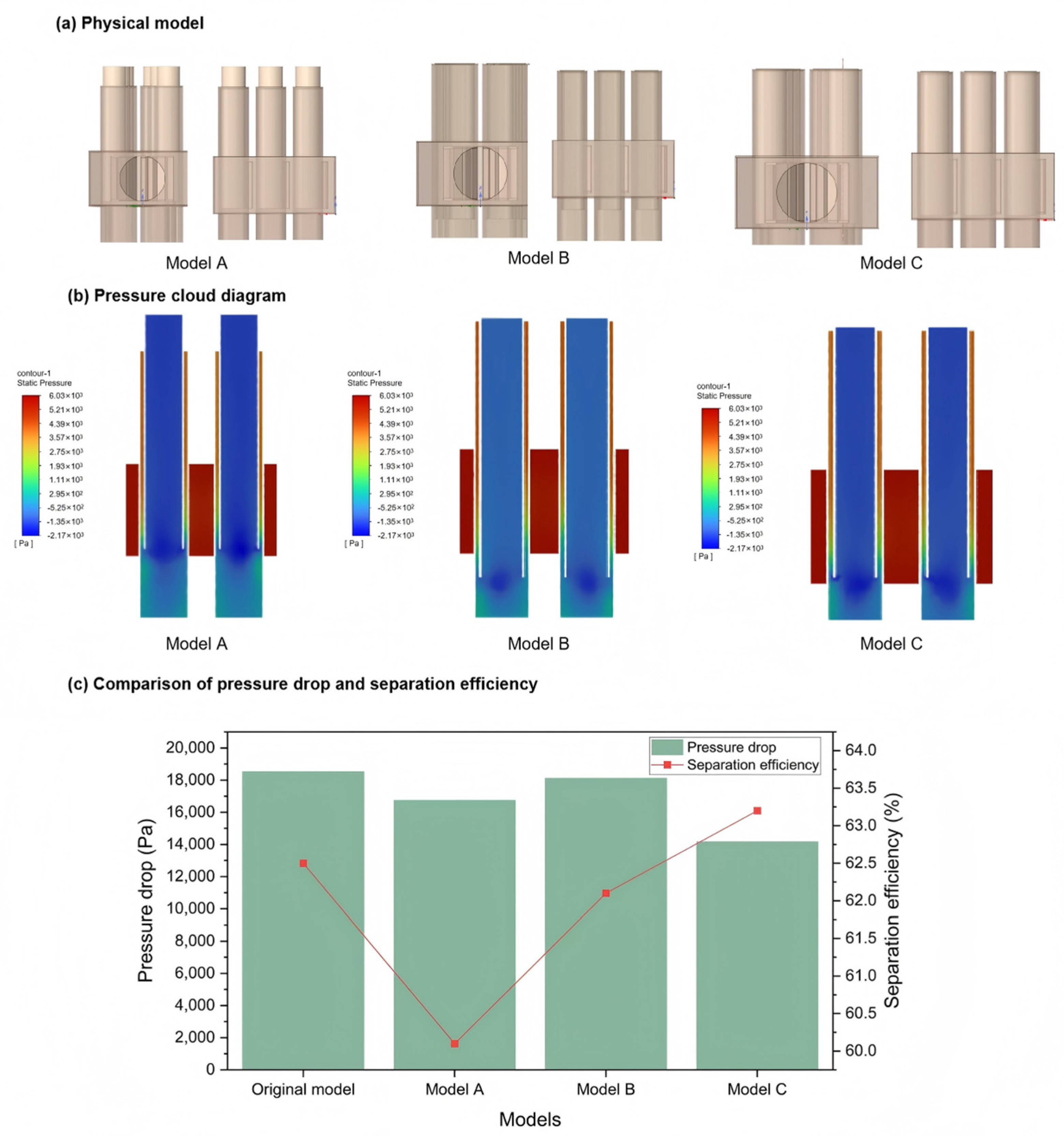

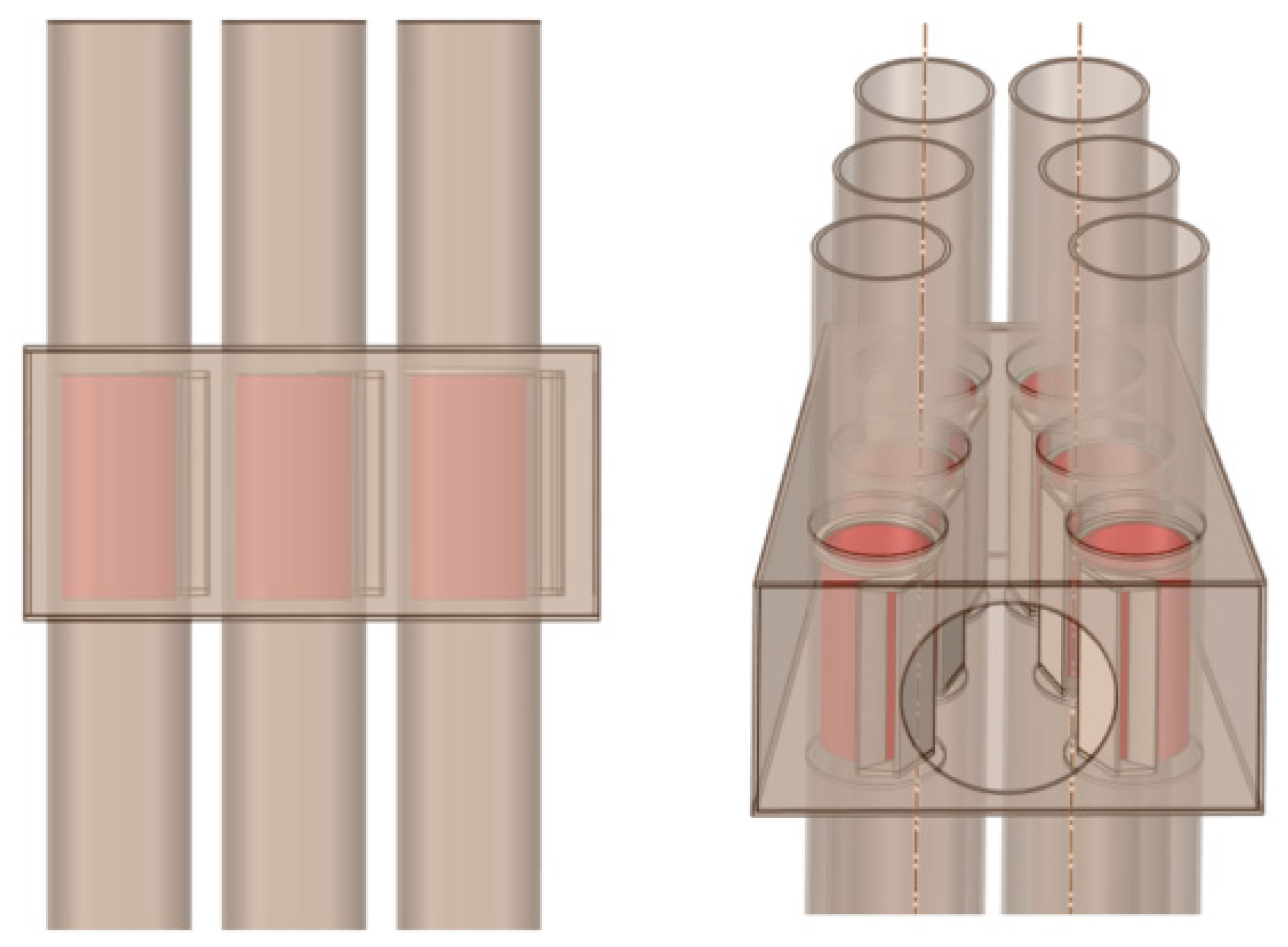

3.2. Second-Stage Separation Axial-Flow Cyclone Tube Model

3.3. Multi-Stage Separation Foam Separation Device Model

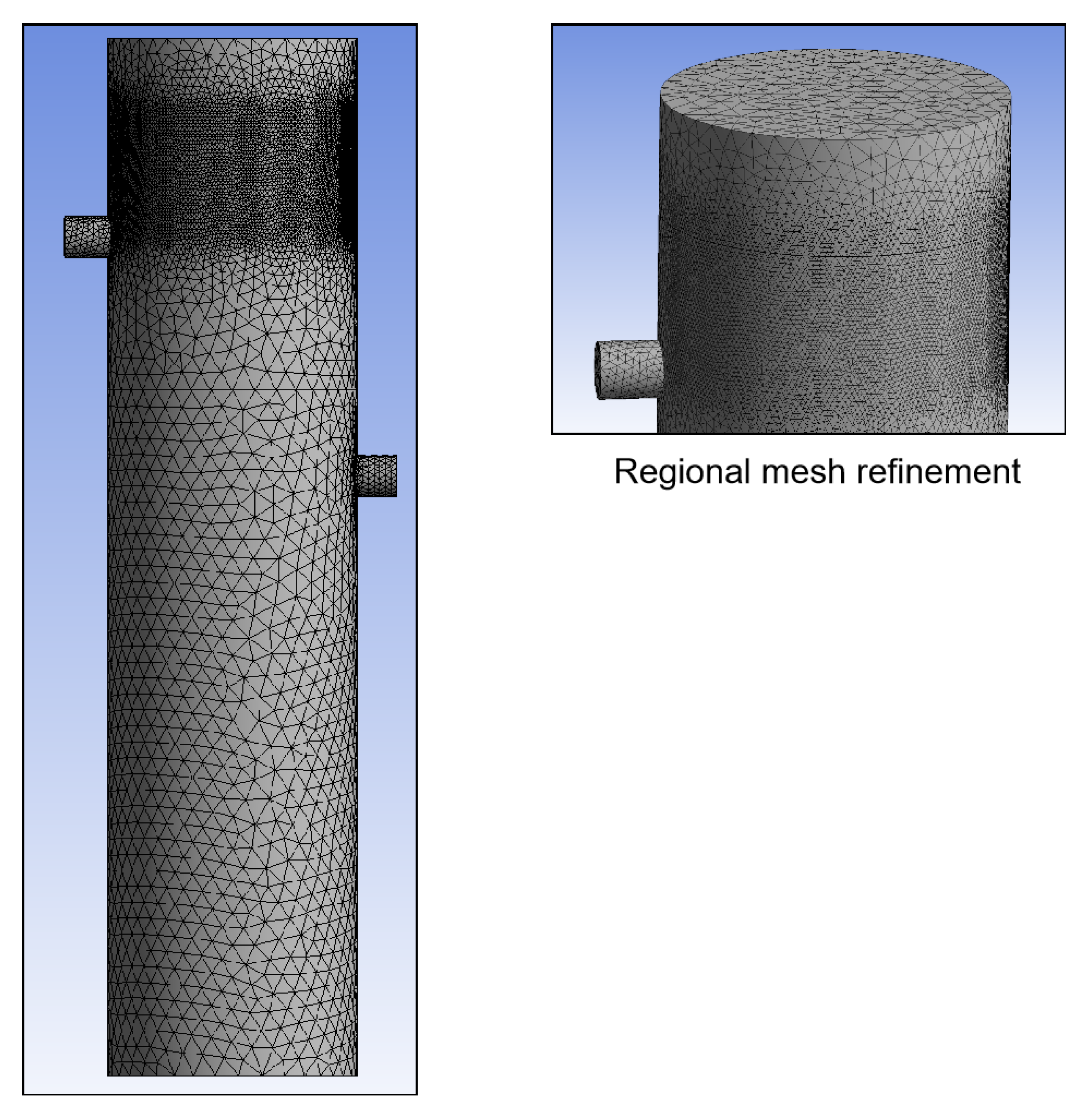

4. Verification of Mesh Independence and Reliability

5. Simulation Results

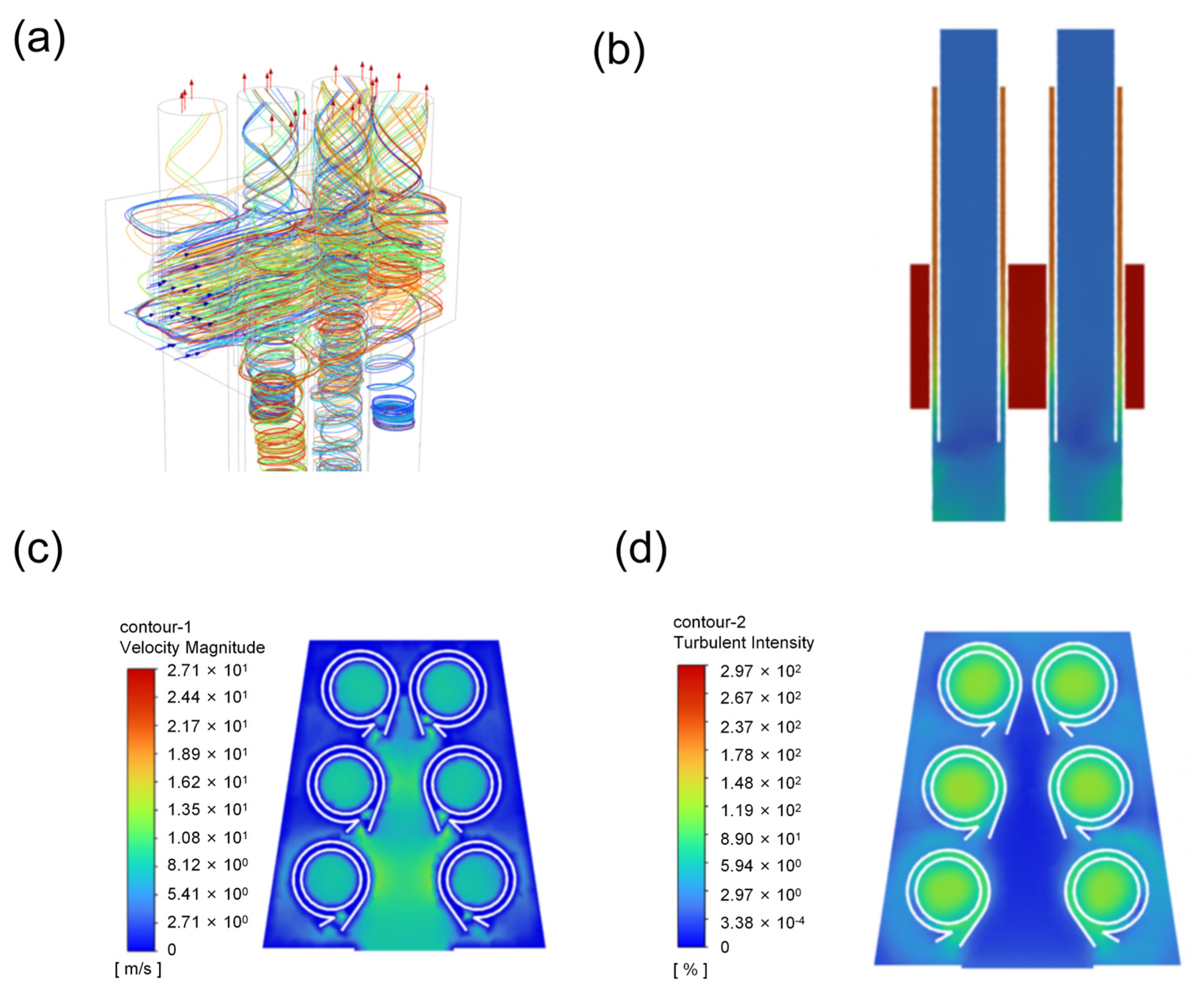

5.1. Flow Field Inside the Separator

5.2. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Separation Effect in the Non-Working Fluid Production Stage

5.2.1. The Influence of Working Pressure Changes on Separation Effect

5.2.2. The Impact of Droplet Volume Fraction at the Separator Inlet on Separation Performance

5.3. Analysis of Factors Affecting the Separation Effect in the Working Fluid Production Stage

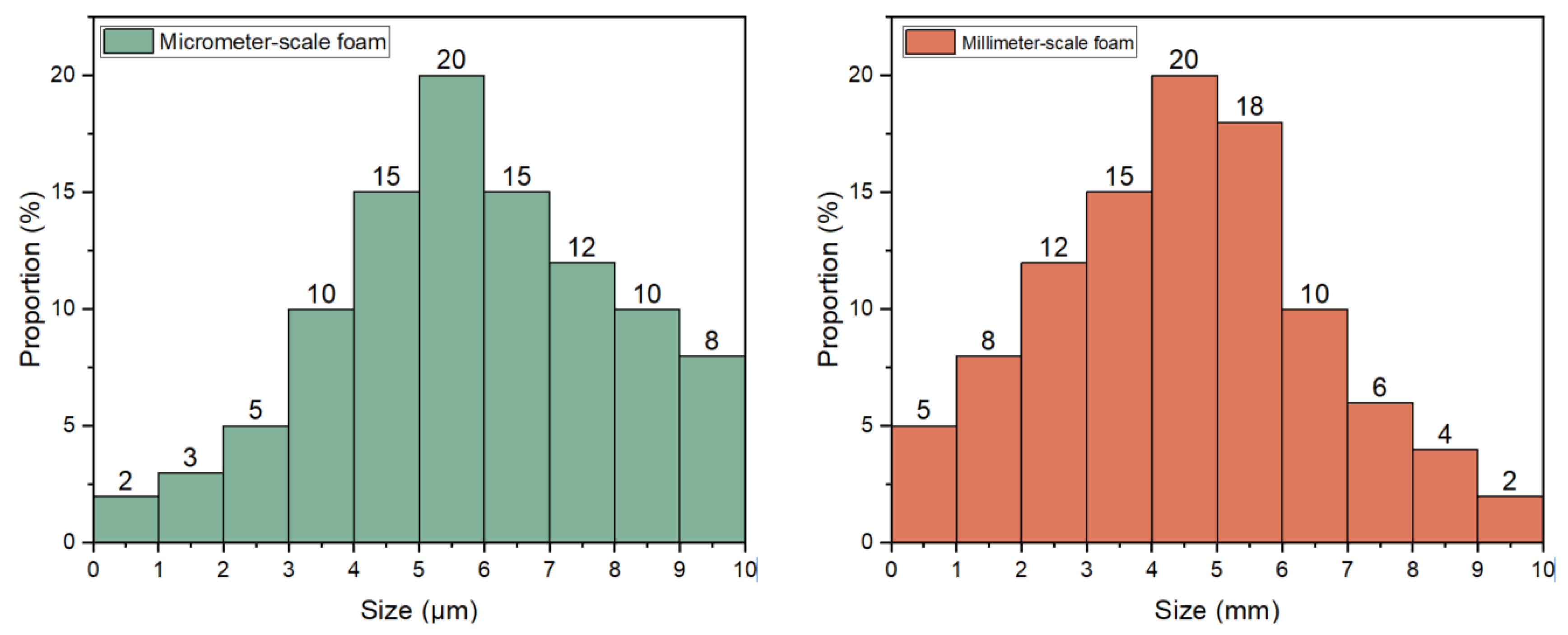

5.3.1. Separation Effect of Micrometer-Scale Foam

- (1)

- The effect of changes in working pressure on the separation effect

- (2)

- The influence of the foam volume fraction at the separator inlet on the separation effect

5.3.2. Separation Effect of Millimeter-Scale Foam

- (1)

- The impact of changes in working pressure on the separation effect

- (2)

- The effect of the volume fraction of foam at the separator inlet on the separation effect

5.3.3. Summary of the Gas-Liquid Foam Separation Effect of the Separator

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Density, kg/m3 | |

| Time, s | |

| Velocity vector composed of and , m/s | |

| Pressure, Pa | |

| Viscosity, Pa·s | |

| Gravitational acceleration, m/s2 | |

| Volume surface tension, N/m | |

| Surface tension, N/m | |

| Surface curvature | |

| Unit normal vector of the interface | |

| Volume fraction of the q-th phase in the calculation unit | |

| Density of the liquid phase, kg/m3 | |

| Density of the gas phase, kg/m3 | |

| Liquid-phase viscosity, Pa·s | |

| Gas-phase viscosity, Pa·s | |

| Foam number density function | |

| Sub-foam volume | |

| Original foam volume | |

| Volume growth (shrinkage rate) of the foam | |

| Foam coalescence rate | |

| Foam burst frequency | |

| h | Thickness of the liquid film, m |

| Surface gradient operator | |

| Average liquid film velocity, m/s | |

| Mass per unit area source | |

| Gravitational component parallel to the liquid film, m/s2 | |

| Shear stress at the gas-liquid interface, Pa | |

| Surface tension coefficient | |

| Pressure in the normal direction of the liquid film, Pa | |

| Pressure of the gas on the wall, Pa | |

| Gravity in the normal direction of the liquid film, Pa | |

| Liquid surface tension, Pa | |

| Surface normal vector |

References

- Ma, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J. Optimization of static defoaming structure in gas-liquid separator. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2021, 47, 9062–9075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, P.; Hurter, S.; Rudolph, V.; Firouzi, M. Comparison of flow dynamics of air-water flows with foam flows in vertical pipes. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2020, 119, 110216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backi, J.; Skogestad, S. A simple dynamic gravity separator model for separation efficiency evaluation incorporating level and pressure control. In Proceedings of the American Control Conference, Seattle, WA, USA, 24–26 May 2017; pp. 2823–2828. [Google Scholar]

- Denkov, N.; Marinova, K.; Tcholakova, S. Mechanistic understanding of the modes of action of foam control agents. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 206, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, A.; Liu, D.; Huang, S. Numerical simulation study of the flow field in the gas-liquid separation metering device. Oil-Gas Field Surf. Eng. 2019, 38, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.; Hornafius, J.S.; Dean, E.; Kazemi, H. Potential of Denver Basin oil fields to store CO2 and produce Bio-CO2-EOR oil. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2019, 81, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Bai, L.; Fu, J.; Qu, B.; Zhou, L. Comprehensive numerical and experimental analysis of dynamic gas-liquid separator with various oil-gas ratios. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2025, 214, 110332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B. Numerical simulation and experimental study of two-phase flow in downhole spiral gas-liquid separator. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1209743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sun, Z.; Geng, K.; Sun, M.; Wang, Z. Numerical analysis of a novel cascading gas-liquid cyclone separator. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 270, 118123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Ling, K. Modeling of Multiphase Flow with the Wellbore in Gas-Condensate Reservoirs Under High Gas/Liquid Ratio Conditions and Field Application. SPE J. 2025, 30, 1301–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Jiang, S.Y.; Duan, R.Q. An accurate continuous surface force model for particle methods. J. Tsinghua Univ. 2018, 58, 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, P.F.; Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Z.; Yang, J.D. Numerical simulation of two-phase transient flow based on a uniform bubble distribution model. China Rural Water Hydropower 2025, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Andrianov, A.; Rossen, W. Sweep efficiency in CO2 foam simulations with oil. In Proceedings of the 16th European Symposium on Improved Oil Recovery, Cambridge, UK, 12–14 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.L.; Xu, M.Q.; Chen, X.J.; Li, L.X. Research on flow characteristics of gas-liquid two-phase flow in centrifugal pump based on CFD. Chem. Eng. Equip. 2023, 7, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Study on the Dynamic Characteristics of Bubbles in Various Media Considering Viscous Effects. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, Zhenjiang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, T.; Sun, Z.Q.; Gen, K.; Sun, M.Z. Numerical simulation of a cascade gas-liquid cyclone separator. J. China Univ. Pet. 2023, 47, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.W. CFD-PBM Numerical Simulation of Tubular Gas-Liquid Cyclone Separator. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Institute of Petrochemical Technology, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Moncayo, J.A.; Dabirian, R.; Mohan, R.S.; Shoham, O.; Kouba, G. Foam break-up under swirling flow in inlet cyclone and GLCC©. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 165, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Lin, C.; Ren, L.; Dong, C.; Song, J. Residual oil evolution based on displacement characteristic curve. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, M.G.; Foroozesh, J. Effect of CO2 mass transfer on rate of oil properties changes: Application to CO2-EOR projects. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 180, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Teng, L.; Gu, S.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, D.; Ye, X.; Wang, J. Experimental study on dispersion behavior during the leakage of high pressure CO2 pipelines. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2019, 105, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Chen, J.; Song, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Jia, Z.; Xu, R. Experimental and numerical study of Upper Swirling Liquid Film (USLF) among Gas-Liquid Cylindrical Cyclones (GLCC). Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 358, 806–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, D.; Wu, Y.; Peterson, C.; Jarriel, S.; Mooney, M.; Tilton, N. The coupled dynamics of foam generation and pipe flow. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2019, 79, 108442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, S.; Negi, G.S.; Agarwal, J.R.; Bera, A.; Shah, M. Experimental and simulation studies for optimization of water-alternating-gas (CO2) flooding for enhanced oil recovery. Pet. Res. 2020, 5, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoori, H.; Mirzaee, R.; Esmaeilzadeh, F.; Vojood, A.; Dowrani, A.S. Pitting corrosion failure analysis of a wet gas pipeline. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2017, 82, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Liu, A.; Xu, Y.; Yan, C. Experimental study on a new gas-liquid separator for a wide range of gas volume fraction. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2020, 160, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, G. Optimization of a two-stage axial-flow cyclone separator focusing on energy consumption and separation efficiency. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2025, 216, 110432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mesh Scheme | Number of Nodes | Number of Elements | System Pressure Drop (Pa) | Stage 1 Separation Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse mesh | 312,455 | 1,452,890 | 8325 | 92.3 |

| Medium mesh | 489,722 | 2,345,671 | 7912 | 93.8 |

| Fine mesh | 690,888 | 3,268,755 | 7896 | 94.2 |

| Extra-fine mesh | 892,144 | 4,123,567 | 7894 | 94.2 |

| Inlet Velocity (m/s) | Separation Efficiency (%) | System Pressure Drop (Pa) | Turbulence Intensity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.0 | 89.5 | 5230 | 14.2 |

| 6.0 | 93.8 | 7890 | 18.5 |

| 8.0 | 95.2 | 12,450 | 22.7 |

| 10.0 | 94.1 | 18,920 | 28.3 |

| Separation Stages | Droplet Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Foam Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Droplet Separation Efficiency | Foam Separation Efficiency | Droplet Cumulative Separation Efficiency | Foam Cumulative Separation Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | 40 | 10 | 48.23% | 28% | 48.23% | 28% |

| 20.71 | 7.2 | |||||

| Stage 2 | 9.2 | 4.52 | 73.25% | 58.33% | 86.15% | 70% |

| 5.54 | 3 | |||||

| Stage 3 | 2.4 | 1.85 | 59.39% | 41% | 94.38% | 82.3% |

| 2.25 | 1.77 |

| Particle Size Range (mm) | Inlet Proportion | Separation Efficiency Per Stage | Foam Cumulative Separation Efficiency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | |||

| 1–2 | 13% | 4.8% | 24.7% | 36.2% | 65.7% |

| 3–4 | 27% | 19.5% | 55.6% | 9.8% | 84.9% |

| 5–6 | 38% | 45.3% | 29.5% | 2.3% | 77.1% |

| 7–8 | 16% | 70.8% | 14.7% | 0.9% | 86.4% |

| 9–10 | 6% | 90.5% | 7.6% | 0.4% | 98.5% |

| Weighted average | 100% | 28% | 58.33% | 41.0% | 82.3% |

| Pressure (MPa) | Outlet Droplet Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Separation Efficiency (%) | Pressure Drop (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.5 | 2.1 | 95.8 | 58 |

| 5 | 1.9 | 96.12 | 62 |

| 5.5 | 1.8 | 96.35 | 67 |

| 6 | 2 | 95.95 | 73 |

| 6.5 | 2.3 | 95.4 | 81 |

| Inlet Droplet Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Outlet Droplet Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Separation Efficiency (%) | Pressure Drop (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.38 | 96.20 | 58 |

| 30 | 1.12 | 96.27 | 61 |

| 50 | 1.8 | 96.35 | 67 |

| 60 | 2.45 | 95.92 | 72 |

| 80 | 4.92 | 93.85 | 78 |

| Pressure (MPa) | Inlet Droplet Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Inlet Foam Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Outlet Droplet Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Outlet Foam Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Droplet Separation Efficiency (%) | Foam Separation Efficiency (%) | Total Separation Efficiency /% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.5 | 40 | 10 | 2.45 | 6.82 | 93.88 | 31.80 | 80.46 |

| 5 | 40 | 10 | 2.18 | 5.97 | 94.55 | 40.30 | 83.72 |

| 5.5 | 40 | 10 | 1.92 | 5.15 | 95.20 | 48.50 | 86.85 |

| 6 | 40 | 10 | 2.06 | 6.33 | 94.85 | 36.70 | 82.78 |

| 6.5 | 40 | 10 | 2.37 | 7.42 | 94.08 | 27.60 | 79.22 |

| Inlet Droplet Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Inlet Foam Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Imported Foam Proportion | Outlet Droplets Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Outlet Foam Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Droplet Separation Efficiency (%) | Foam Separation Efficiency (%) | Total Separation Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 0 | 0 | 1.83 | / | 96.35 | / | 96.35 |

| 40 | 10 | 20% | 2.18 | 5.97 | 94.55 | 40.30 | 83.72 |

| 30 | 20 | 40% | 2.06 | 13.49 | 93.14 | 32.56 | 74.26 |

| 20 | 30 | 60% | 1.94 | 22.37 | 90.28 | 25.42 | 62.71 |

| 10 | 40 | 80% | 1.16 | 33.48 | 88.42 | 16.28 | 49.85 |

| Pressure (MPa) | Inlet Droplet Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Inlet Foam Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Outlet Droplet Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Outlet Foam Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Droplet Separation Efficiency (%) | Foam Separation Efficiency (%) | Total Separation Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.5 | 40 | 10 | 2.60 | 2.05 | 93.50 | 79.50 | 88.90 |

| 5 | 40 | 10 | 2.30 | 1.80 | 94.25 | 82.00 | 90.63 |

| 5.5 | 40 | 10 | 2.05 | 1.60 | 94.88 | 84.50 | 91.94 |

| 6 | 40 | 10 | 2.25 | 1.90 | 94.38 | 81.20 | 90.19 |

| 6.5 | 40 | 10 | 2.52 | 2.20 | 93.70 | 78.70 | 88.35 |

| Inlet Droplet Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Inlet Foam Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Imported Foam Proportion | Outlet Droplets Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Outlet Foam Volume Fraction (10−5 m3·m−3) | Droplet Separation Efficiency (%) | Foam Separation Efficiency (%) | Total Separation Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 0 | 0 | 1.90 | / | 96.20 | / | 96.20 |

| 40 | 10 | 20% | 2.30 | 1.80 | 94.25 | 82.30 | 90.63 |

| 30 | 20 | 40% | 2.15 | 3.80 | 92.83 | 81.00 | 88.10 |

| 20 | 30 | 60% | 1.98 | 6.22 | 90.10 | 79.33 | 83.36 |

| 10 | 40 | 80% | 1.25 | 9.18 | 87.50 | 77.25 | 79.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, Y.; Wang, F.; Wu, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, G. Numerical Simulation and Structural Optimization of Multi-Stage Separation Devices for Gas-Liquid Foam Flow in Gas Fields. Modelling 2025, 6, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040160

Lin Y, Wang F, Wu Y, Xu H, Zhou J, Yang J, Zhang X, Zheng G. Numerical Simulation and Structural Optimization of Multi-Stage Separation Devices for Gas-Liquid Foam Flow in Gas Fields. Modelling. 2025; 6(4):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040160

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Yu, Feng Wang, Yu Wu, Hao Xu, Jun Zhou, Junfei Yang, Xunjia Zhang, and Guodong Zheng. 2025. "Numerical Simulation and Structural Optimization of Multi-Stage Separation Devices for Gas-Liquid Foam Flow in Gas Fields" Modelling 6, no. 4: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040160

APA StyleLin, Y., Wang, F., Wu, Y., Xu, H., Zhou, J., Yang, J., Zhang, X., & Zheng, G. (2025). Numerical Simulation and Structural Optimization of Multi-Stage Separation Devices for Gas-Liquid Foam Flow in Gas Fields. Modelling, 6(4), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040160