Comparative Study of Different Modelling Approaches for Progressive Collapse Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

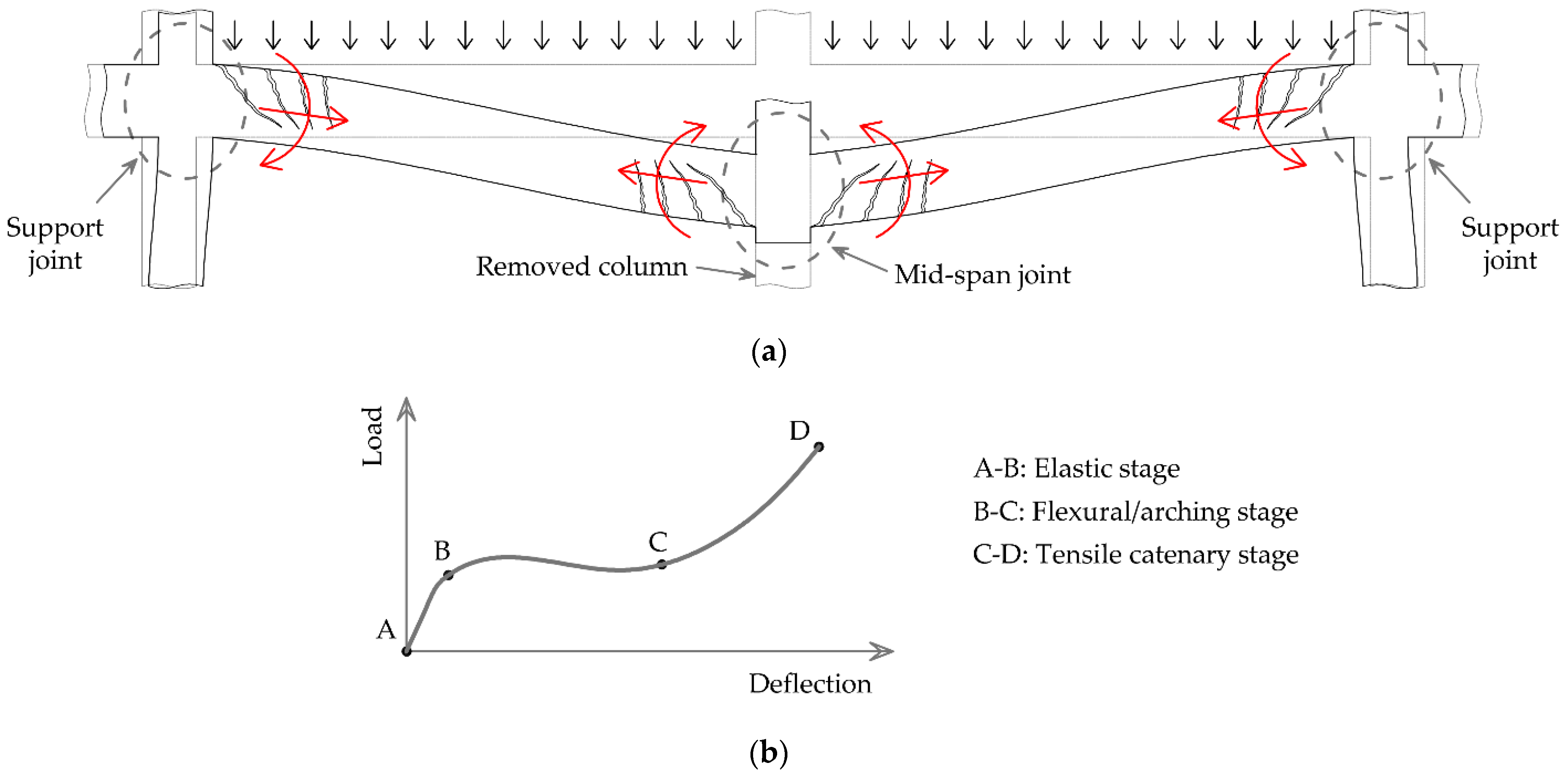

2. Methodology

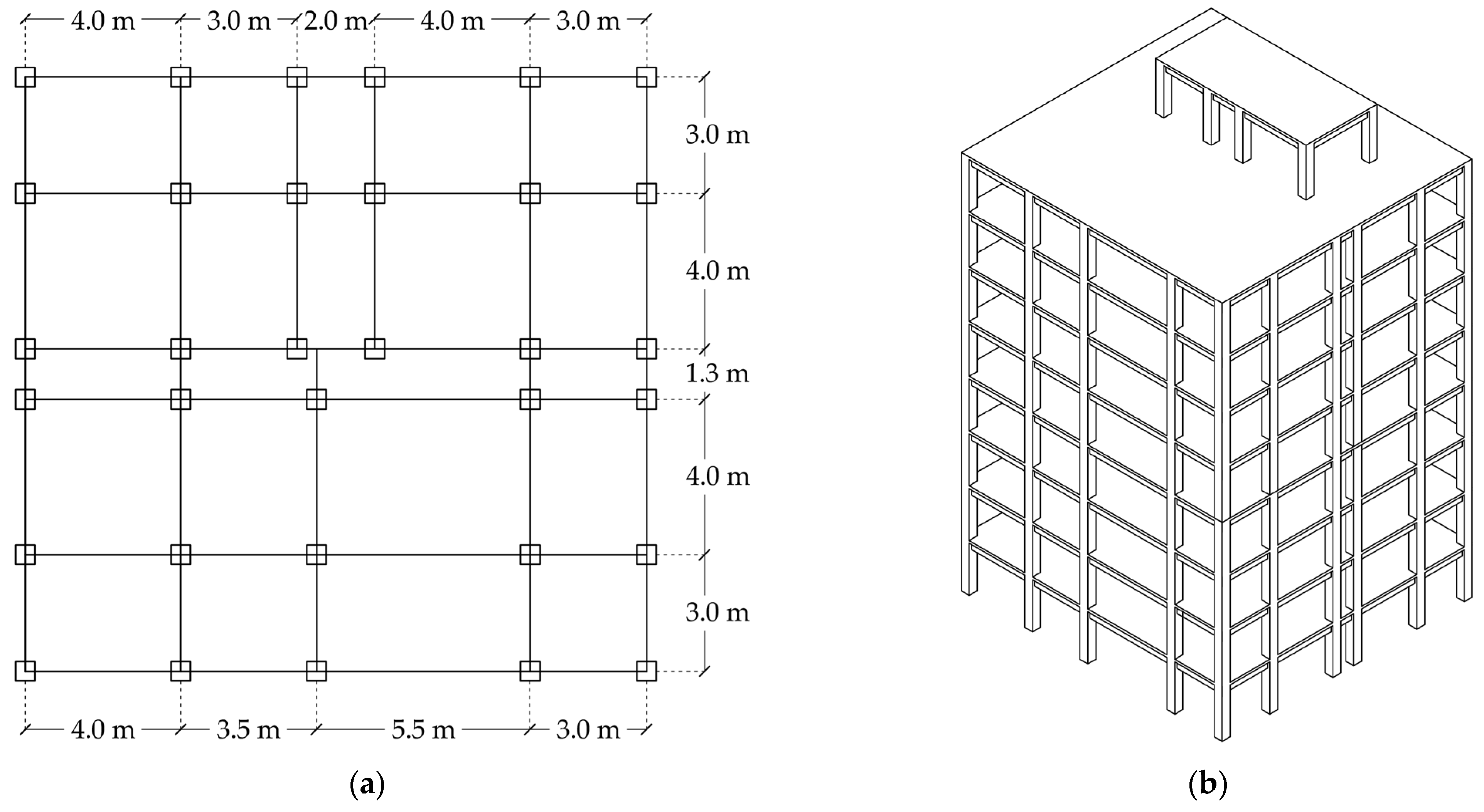

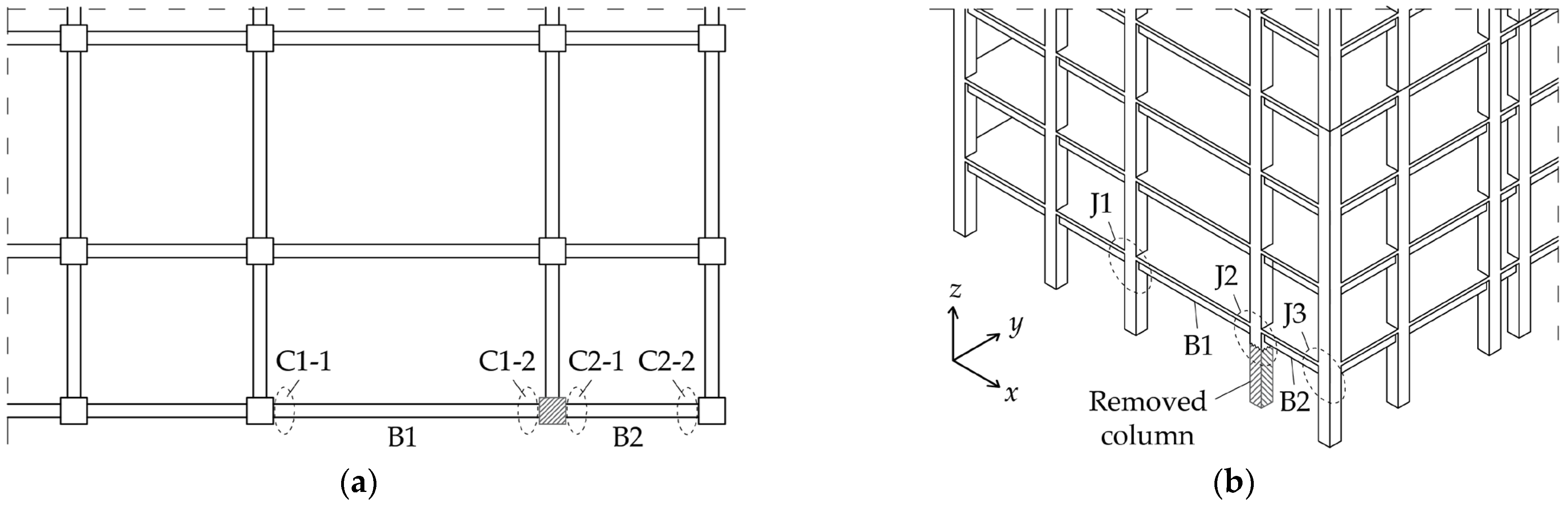

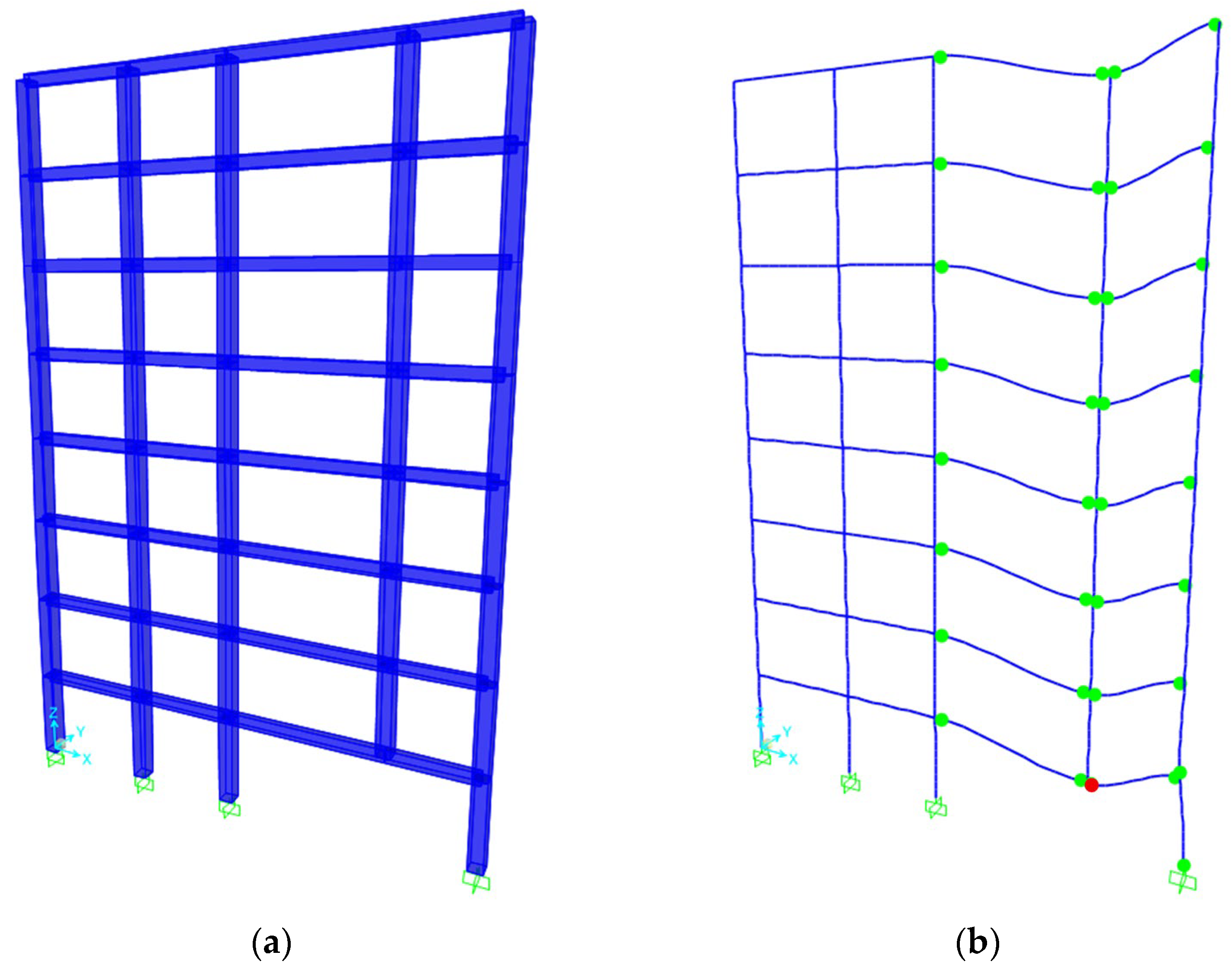

2.1. Prototype Structure

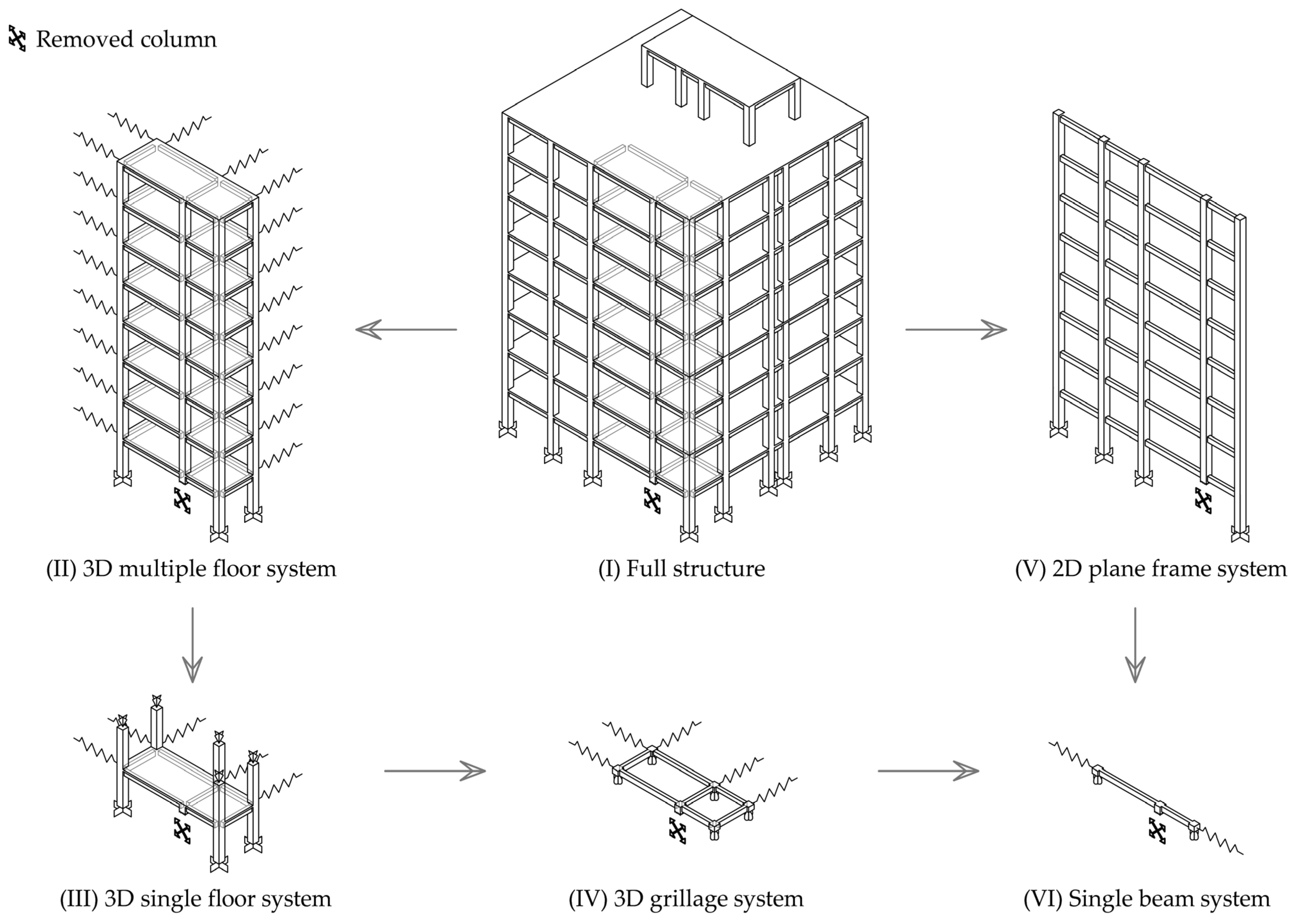

2.2. Modelling Approaches

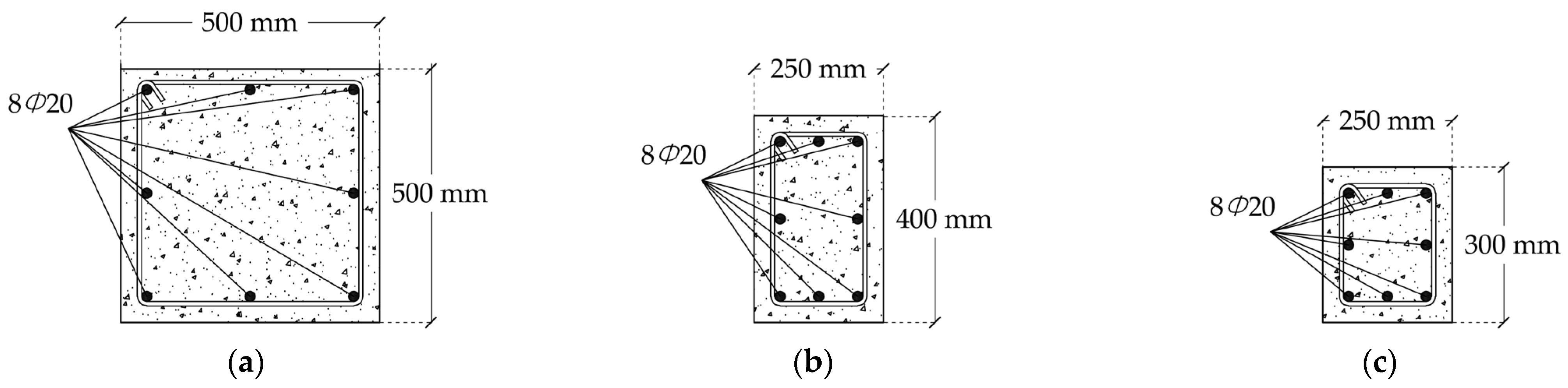

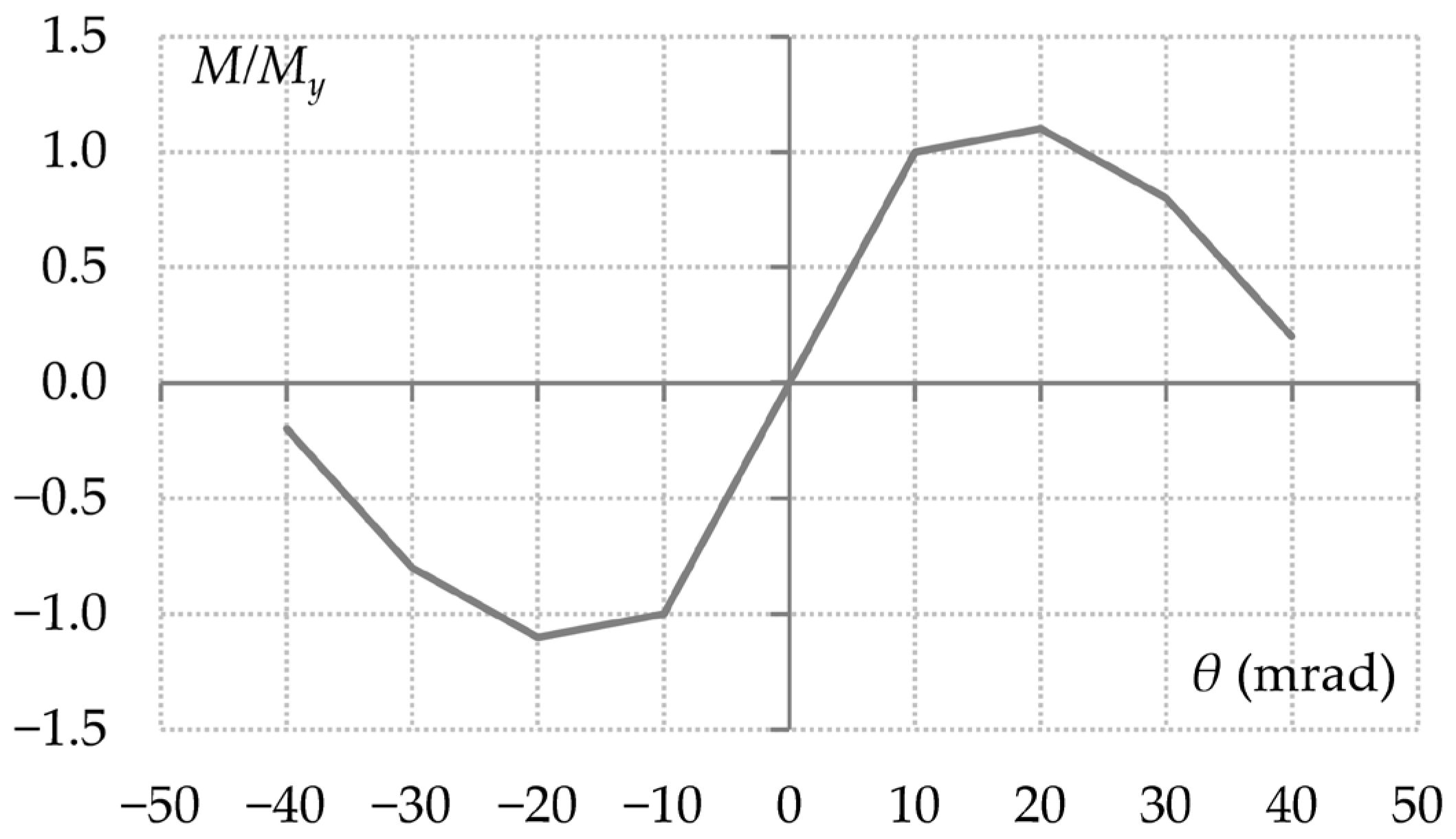

2.3. Material Modelling and Plastic Hinge Definition

2.4. Analysis Approach

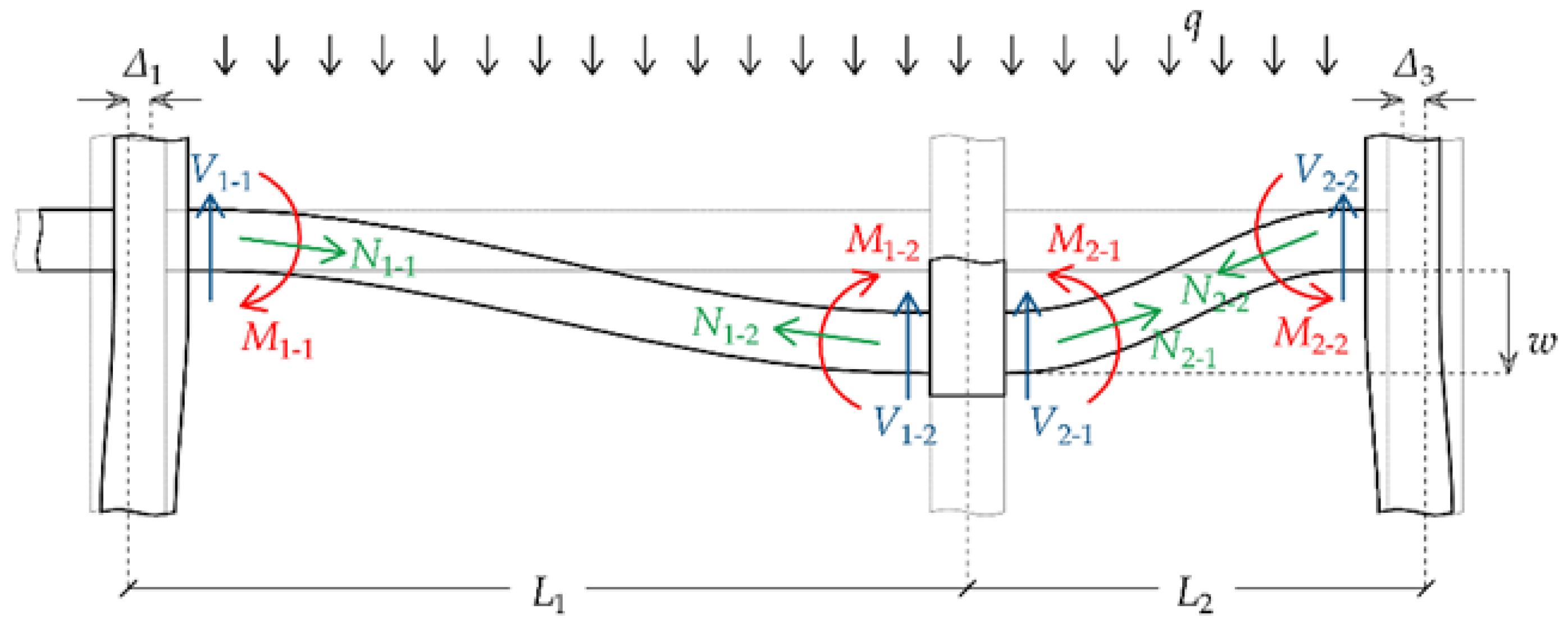

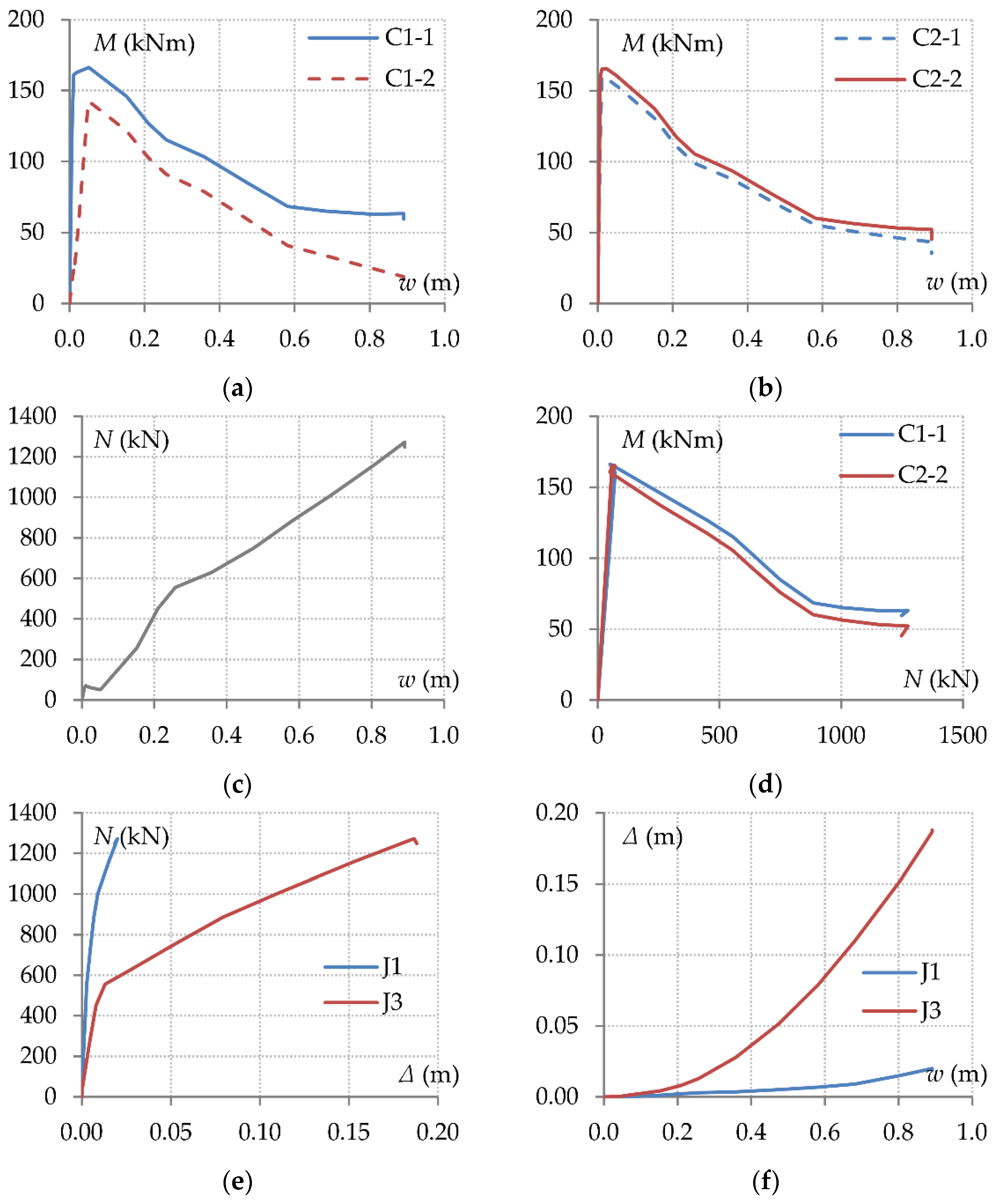

- Vertical displacement of joint J2, denoted by w.

- Horizontal displacements of joints J1 and J3, denoted by Δ1 and Δ3, respectively.

- Bending moments at the ends of beam B1 (i.e., M1-1 and M1-2) and beam B2 (i.e., M2-1 and M2-2).

- Shear forces at the ends of beam B1 (i.e., V1-1 and V1-2) and beam B2 (i.e., V2-1 and V2-2).

- Axial forces at the ends of beam B1 (i.e., N1-1 and N1-2) and beam B2 (i.e., N2-1 and N2-2).

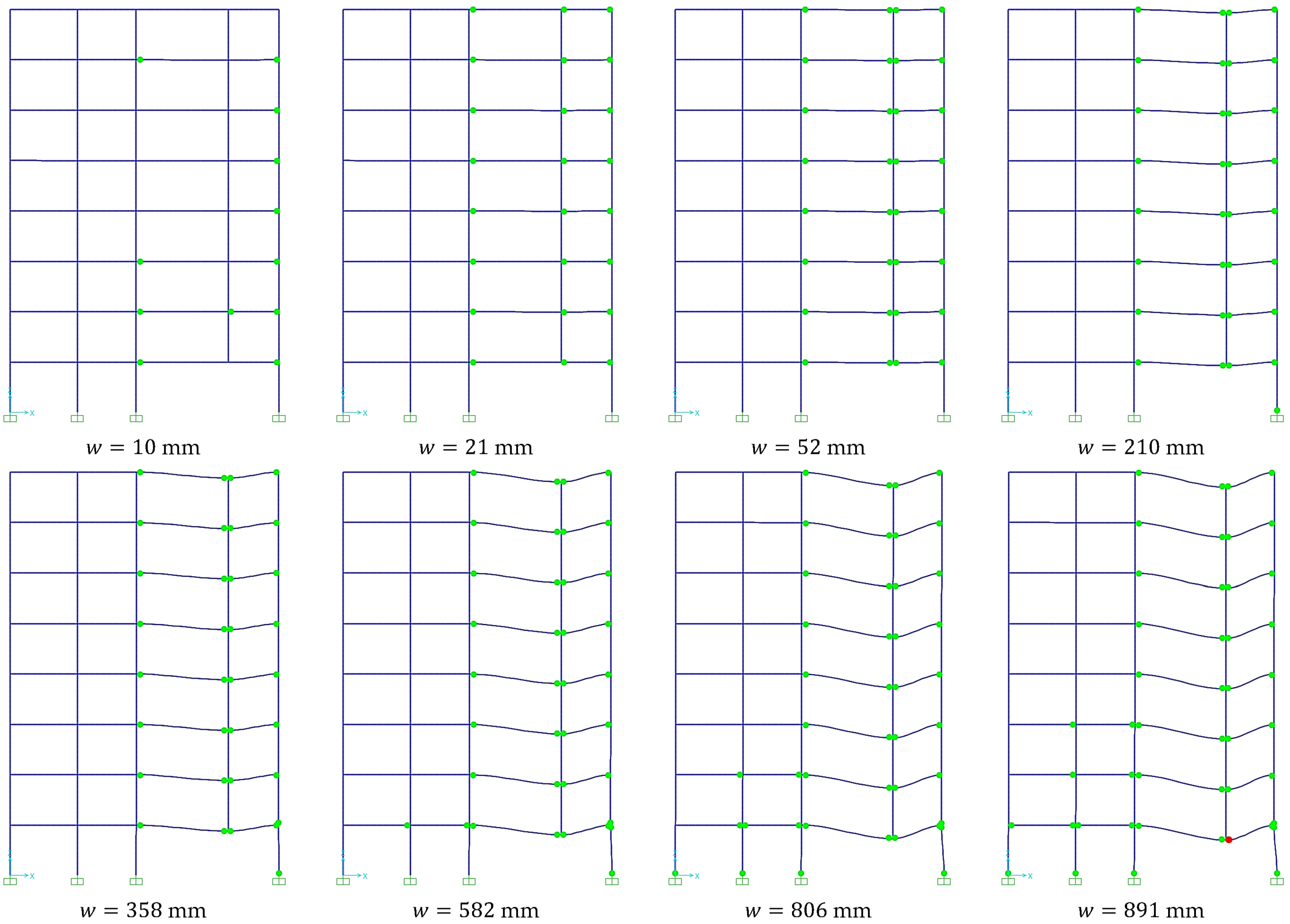

3. Analysis of Full-Structure Model

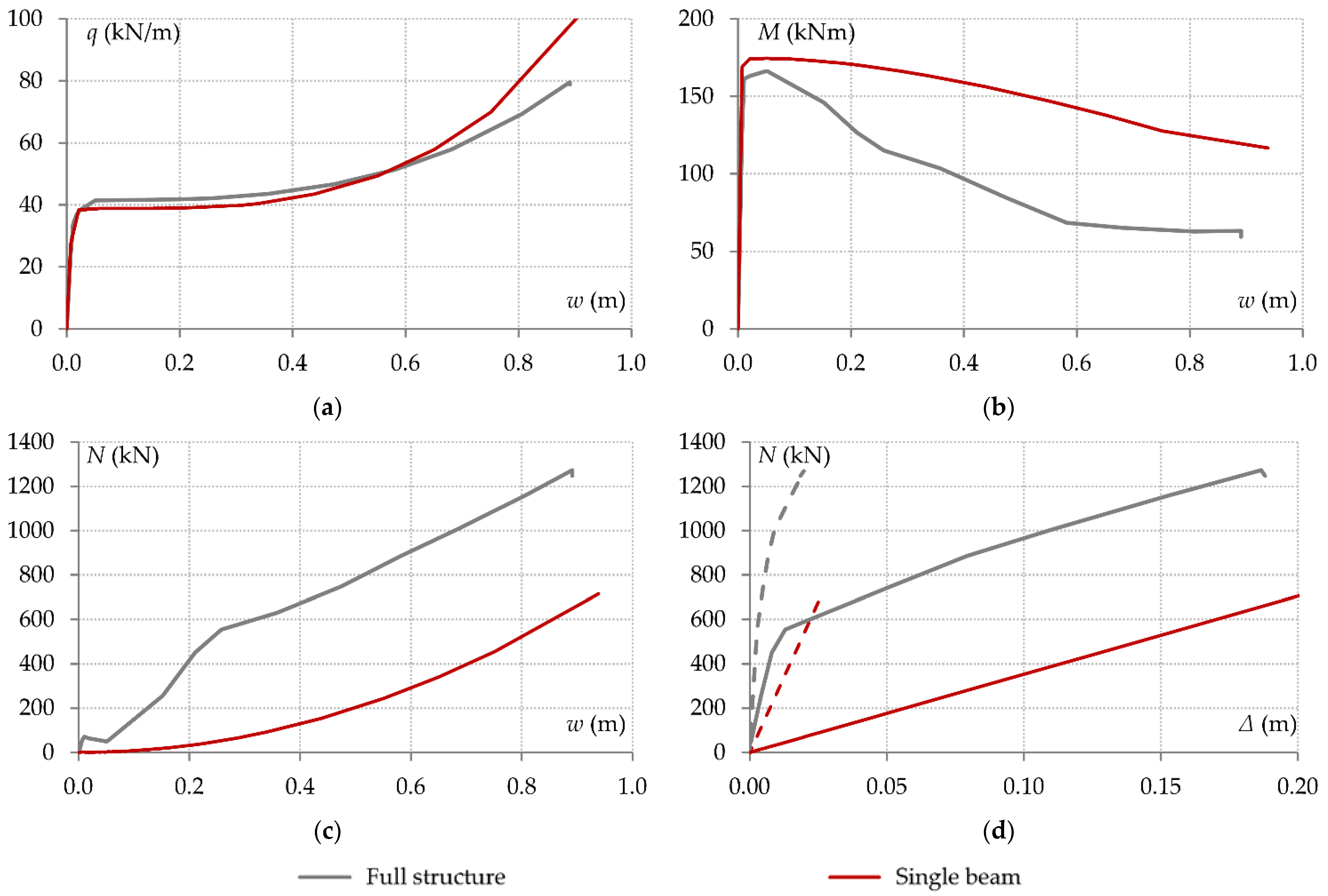

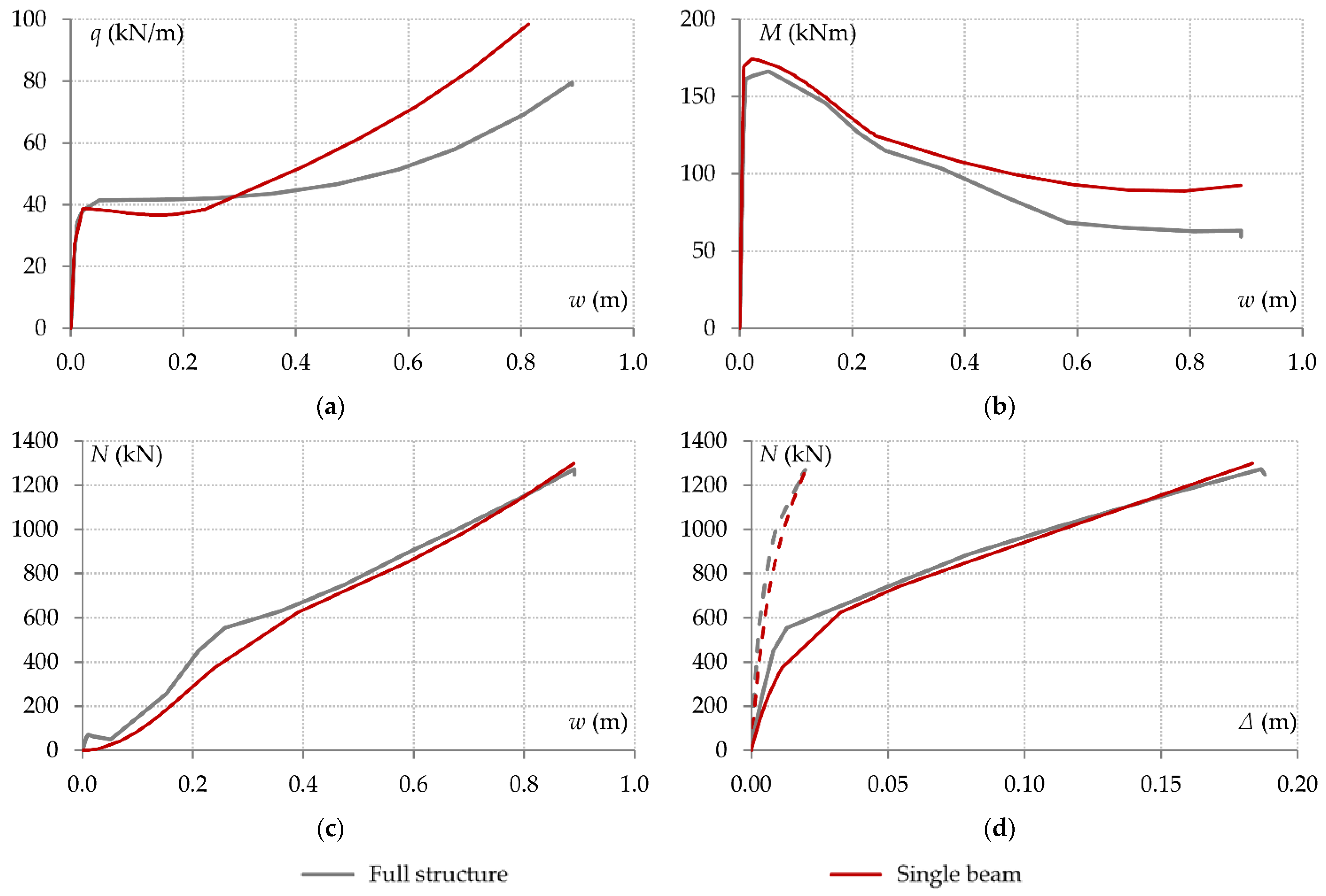

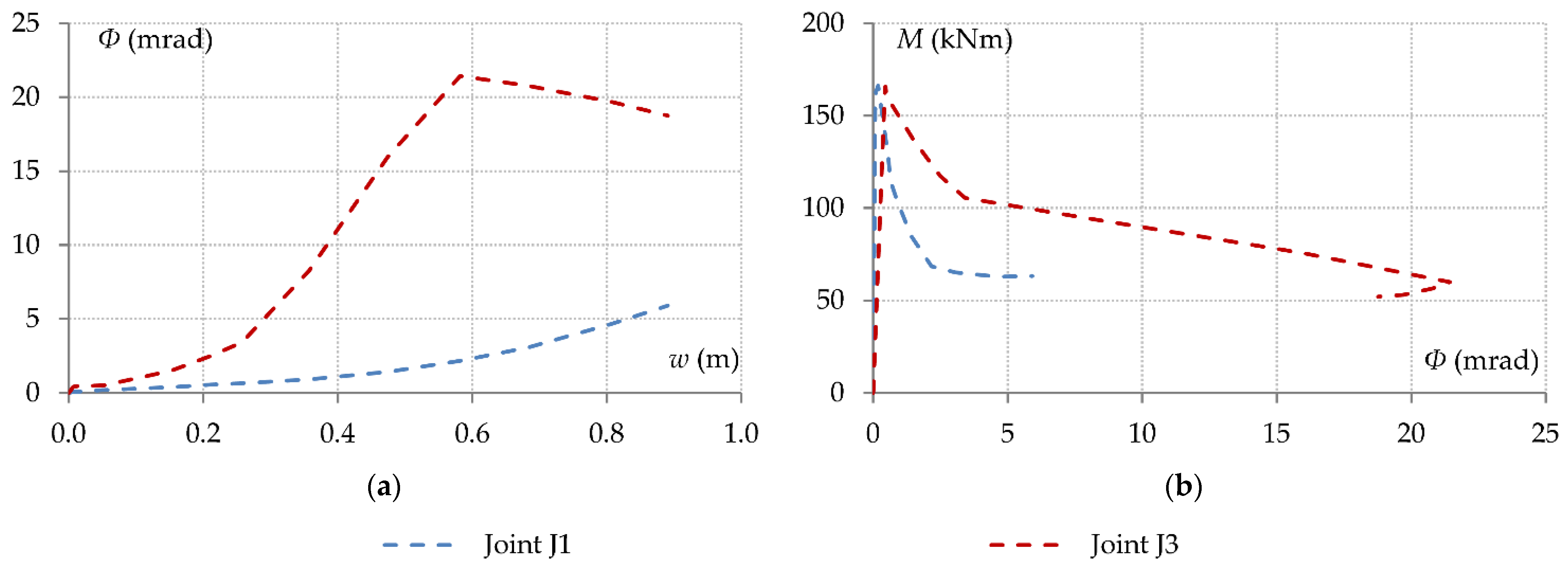

3.1. Response of Beams B1 and B2

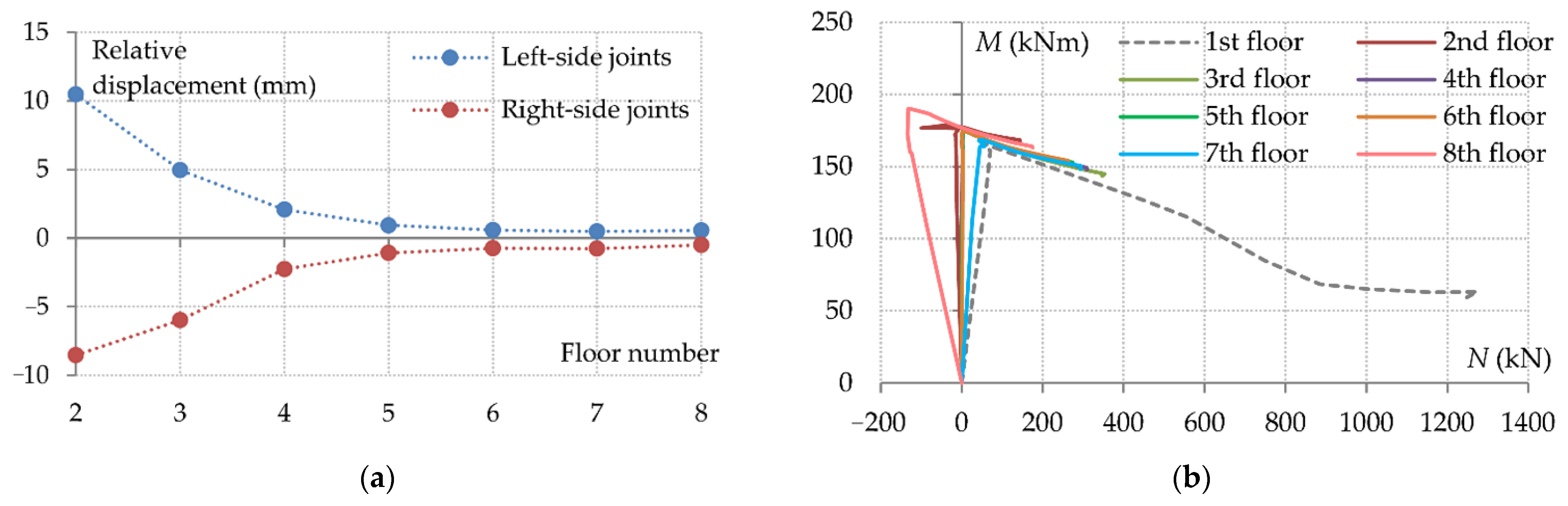

3.2. Contribution of the Upper Floors

4. Analysis of Reduced 3D and 2D Models

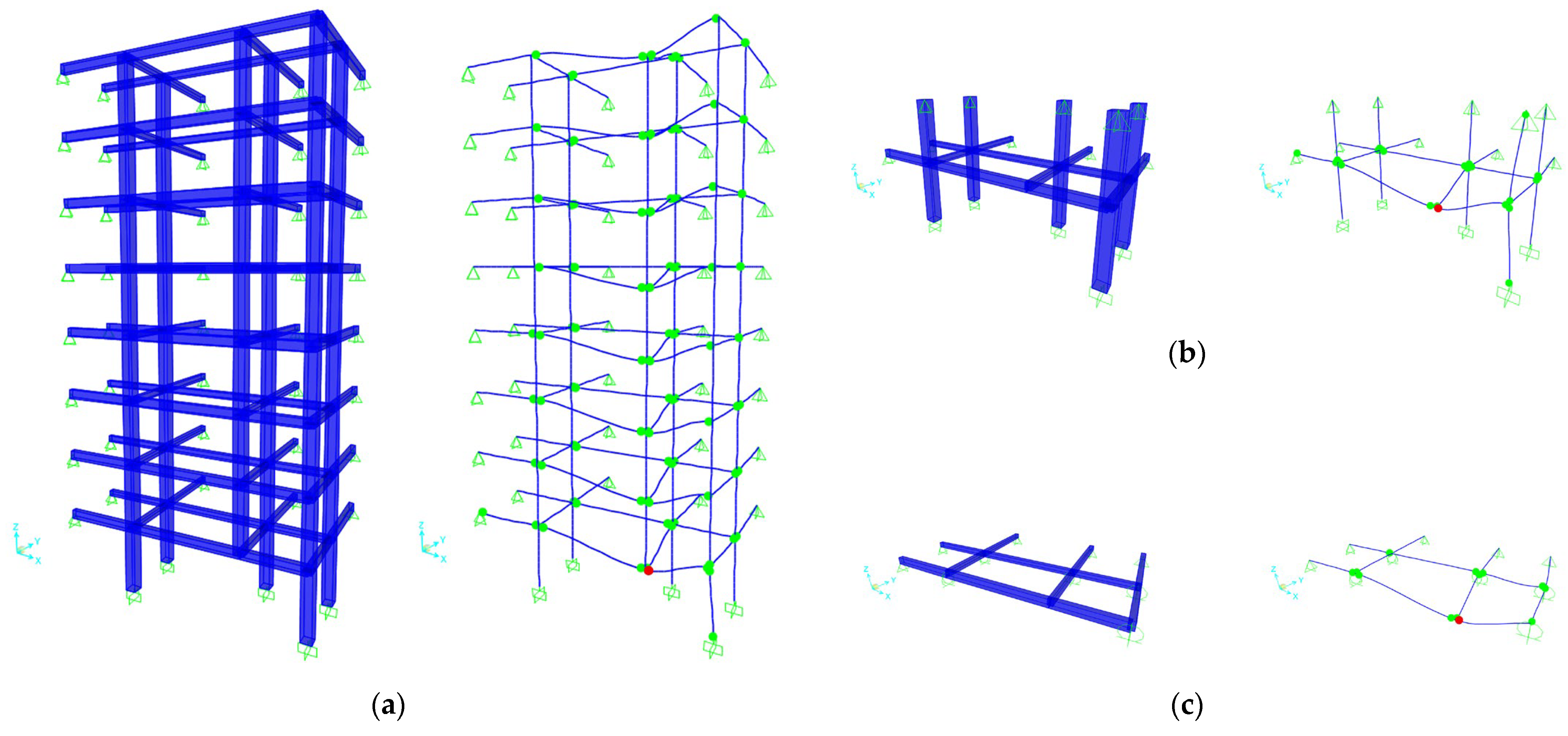

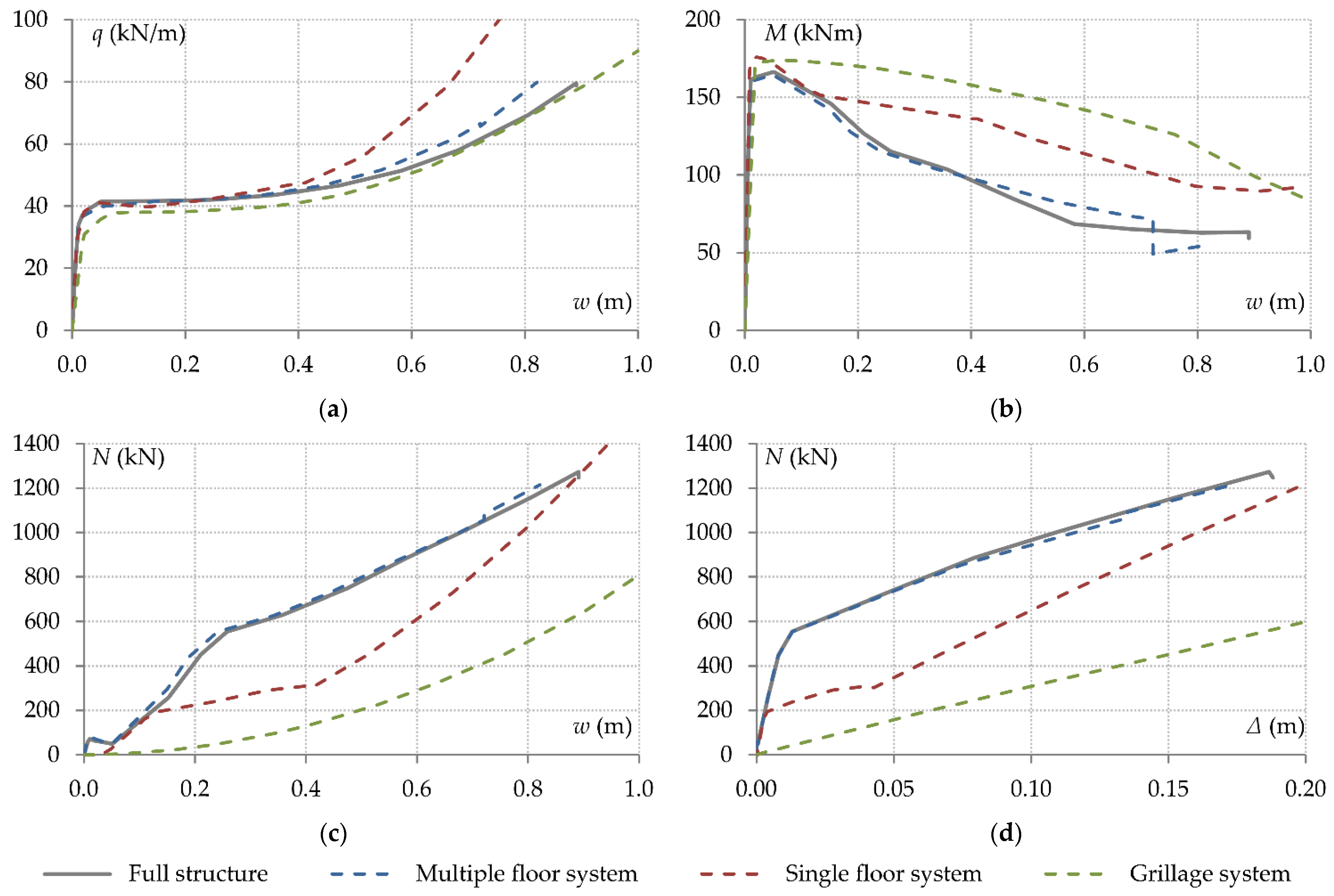

4.1. Three-Dimensional Structural Systems

4.1.1. Multiple Floor System

4.1.2. Single Floor System

4.1.3. Grillage System

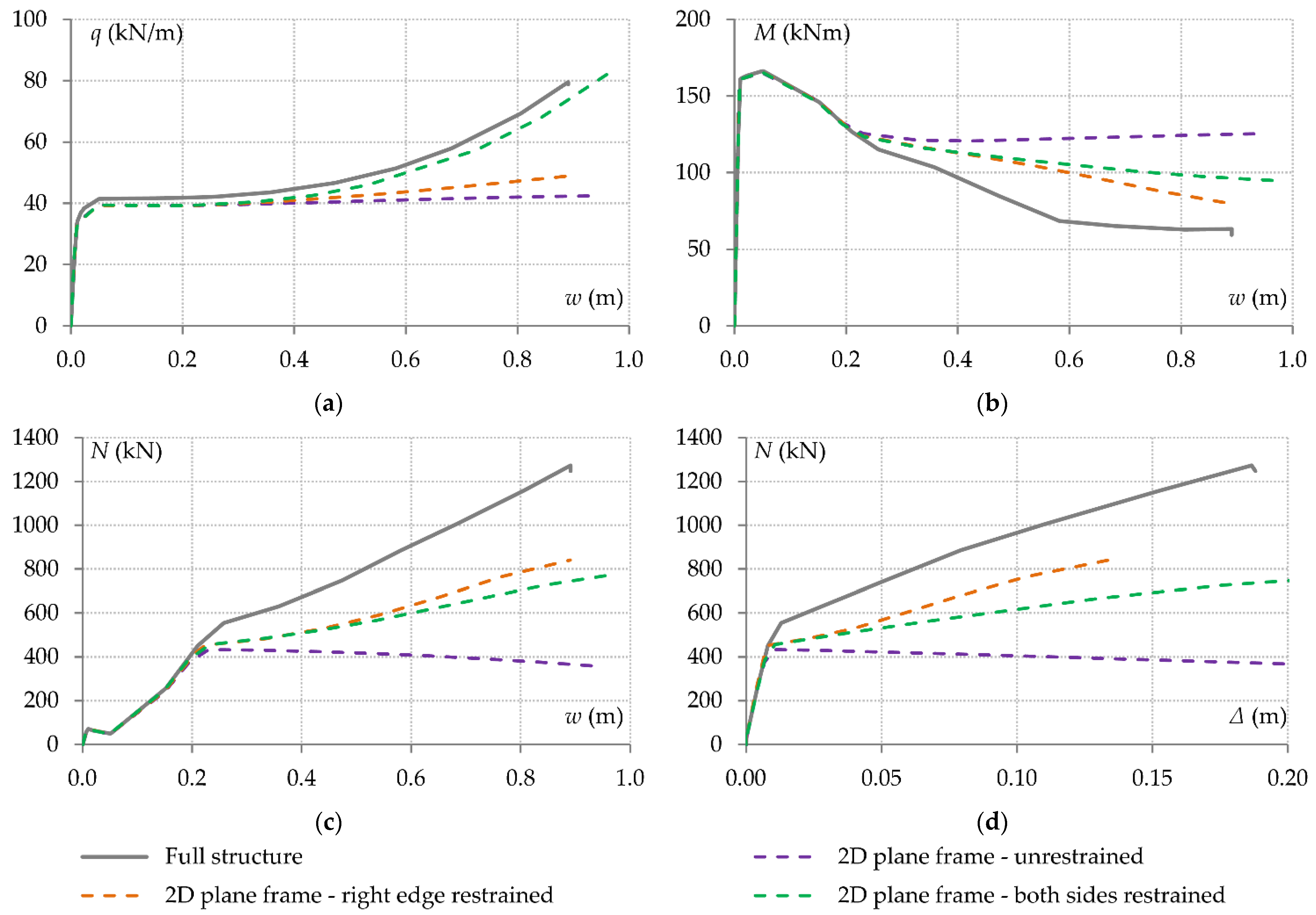

4.2. Multi-Storey Plane Frame

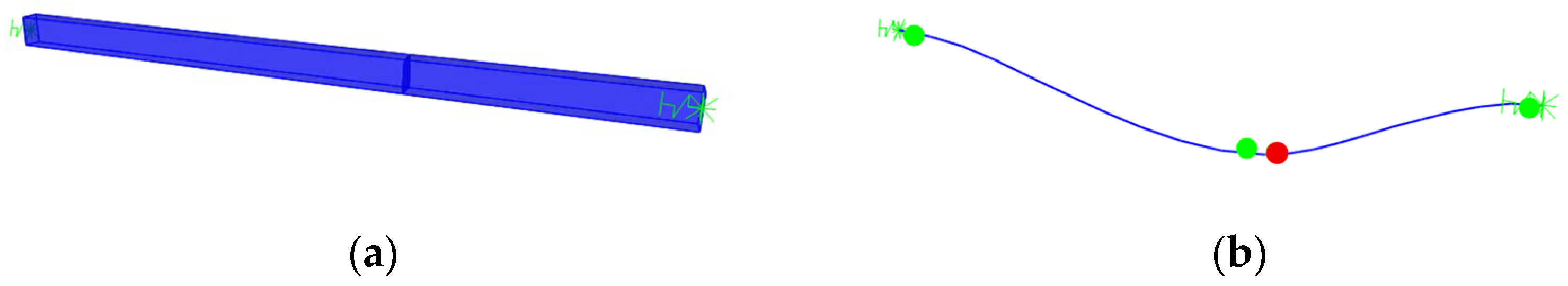

5. Double-Span Beam System

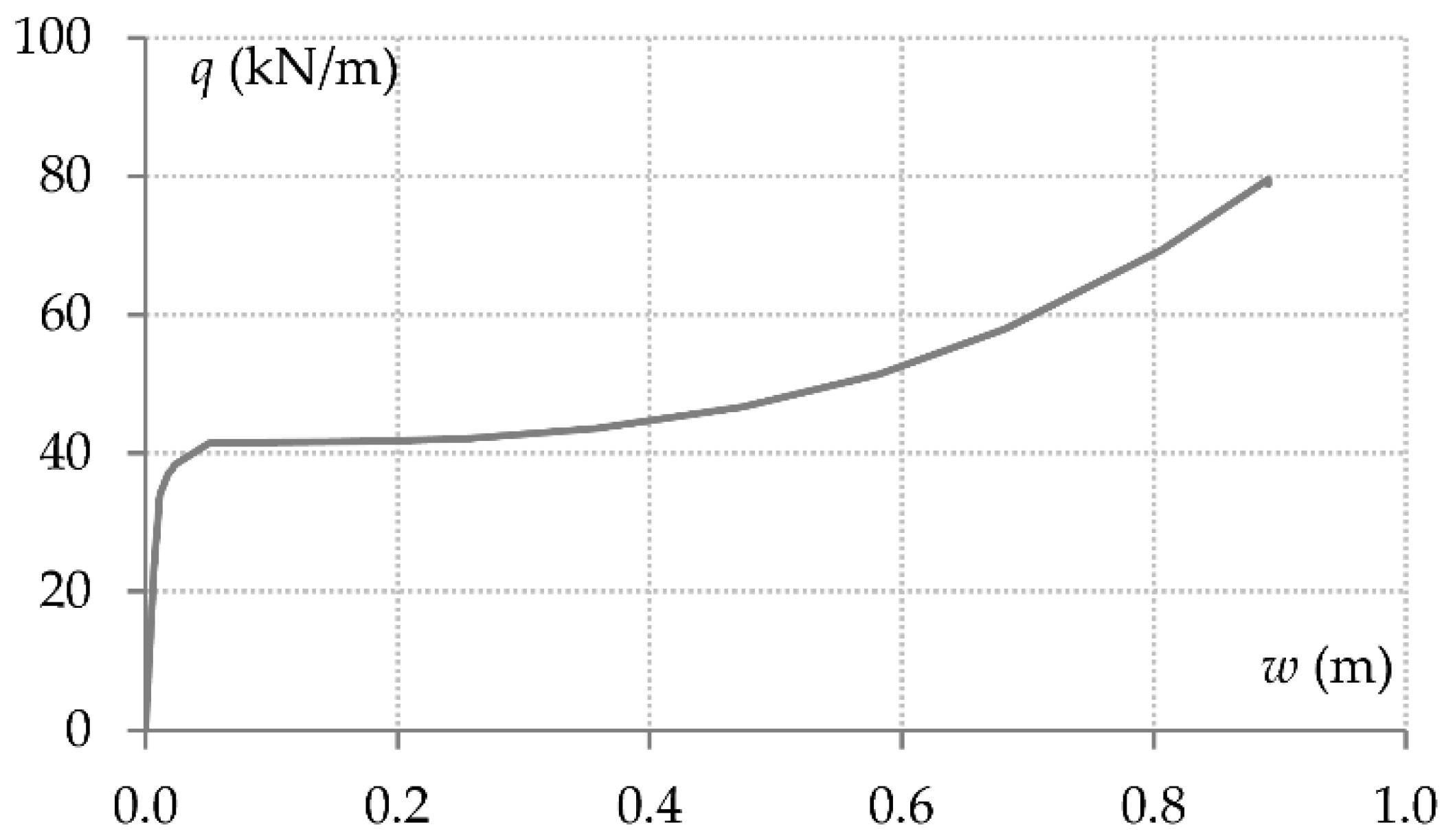

5.1. Simulation of Axial Restraint Through Linear Elastic Springs

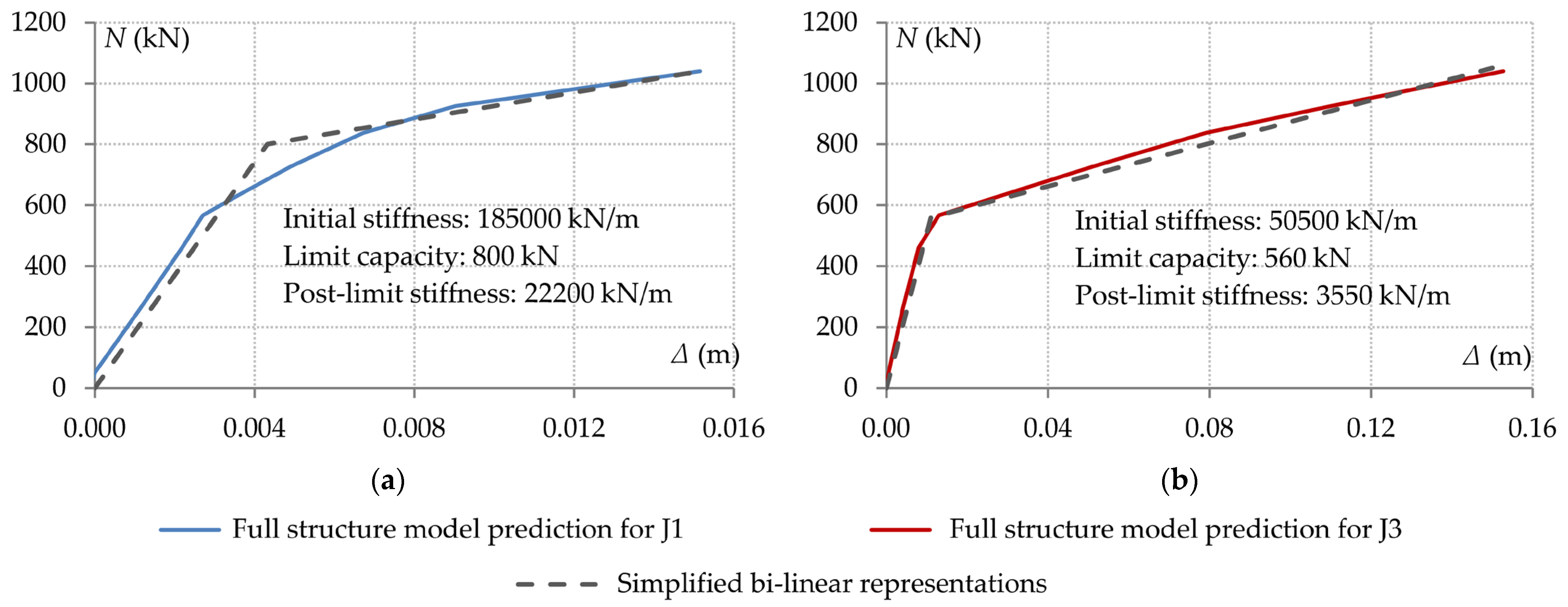

5.2. Simulation of Axial Restraint Through Bi-Linear Links

6. Conclusions

- The axial displacement of the supports of the system that is directly affected by the column loss is significantly influenced by material nonlinearity due to the formation of plastic hinges in adjacent structural elements. As a result, the relationship between the support axial displacements and the axial forces transferred from the end connections is highly nonlinear. The axial restraint is also governed by the redundancy of the structure on either side of the directly affected area, the out-of-plane flexural stiffness of the transverse beams and the in-plane bending stiffness of the surrounding columns.

- In a ground-floor column removal scenario, the ground-floor neighbouring columns are subject to considerably higher bending moments and deformations due to their support boundary restraints, compared with upper-floor columns. Consequently, the axial forces in the upper-floor beams are substantially smaller than those in the first-floor beams. Therefore, the responses of the beams of different floors are governed by very different load-resistance mechanisms.

- A 3D multiple-floor model can describe structural performance with reasonable accuracy. A 3D single-floor model, on the other hand, does not capture the effects of axial restraint adequately. The resistance of the supports to horizontal displacement decreases significantly when the strength of the neighbouring elements is exhausted. However, at large deformation stages, the support axial stiffness increases due to geometric nonlinear effects, which is not representative of the actual structural behaviour. In a grillage model, a reasonable approximation of the load–deflection response was obtained in this study, but it was shown that this resulted from an inaccurate representation of the contributions of different load resistance mechanisms.

- Plane frame models fail to reproduce boundary conditions sufficiently. Key elements of the surrounding structure, such as the transverse beams, are omitted. The representation of axial restraint through linear elastic springs will most likely lead to incorrect results, as the axial deformation of the supports varies nonlinearly. This approximation may also result in incorrect assessment of the contribution of the different load resistance mechanisms, similar to the limitations observed in the grillage model.

- In the double-span beam model, the axial restraint should be simulated with sufficient accuracy. Since the resistance provided by the supports against horizontal displacements varies nonlinearly with respect to the increase in the beam tensile force, linear elastic springs cannot describe the boundary conditions accurately. Instead, by employing suitable links with bi-linear force–deformation characteristics, a more representative approximation is obtained. However, it is found that, although the beam axial force is described accurately, connection bending moments may deviate from actual values. This shows that another parameter that influences the progressive collapse response is the rotational stiffness provided to the support joints from the surrounding structure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elkady, N.; Nelson, L.A.; Weekes, L.; Makoond, N.; Buitrago, M. Progressive collapse: Past, present, future and beyond. Structures 2024, 62, 106131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.R. Preventing disproportionate collapse. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2006, 20, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starossek, U. Progressive Collapse of Structures; Thomas Telford: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianidis, P.; Nethercot, D. Considerations for robustness in the design of steel and composite frame structures. Struct. Eng. Int. 2017, 27, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, G.V.; Izzuddin, B.A. The ‘sudden column loss’ idealisation for disproportionate collapse assessment. Struct. Eng. 2010, 88, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Tan, K.H. Structural behavior of RC beam-column subassemblages under a middle column removal scenario. J. Struct. Eng. 2013, 139, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, N.S.; Tan, K.H.; Lee, C.K. Experimental studies of 3D RC substructures under exterior and corner column removal scenarios. Eng. Struct. 2017, 150, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianidis, P.M.; Nethercot, D.A.; Izzuddin, B.A.; Elghazouli, A.Y. Robustness assessment of frame structures using simplified beam and grillage models. Eng. Struct. 2016, 115, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Wang, B. Evaluation of progressive collapse resistances of RC frame with contributions of beam, slab and infill wall. Structures 2023, 53, 1463–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianidis, P.M.; Nethercot, D.A.; Izzuddin, B.A.; Elghazouli, A.Y. Progressive collapse: Failure criteria used in engineering analysis. In Proceedings of the 2009 Structures Congress, Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–2 May 2009; ASCE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1811–1820. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, W.-J.; He, Q.-F.; Xiao, Y.; Kunnath, S.K. Experimental study on progressive collapse-resistant behavior of reinforced concrete frame structures. ACI Struct. J. 2008, 105, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Tan, K.H. Experimental and numerical investigation on progressive collapse resistance of reinforced concrete beam column sub-assemblages. Eng. Struct. 2013, 55, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianidis, P.M.; Nethercot, D.A.; Izzuddin, B.A.; Elghazouli, A.Y. Modelling of beam response for progressive collapse analysis. Structures 2015, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, A.T.; Cao, D.K. Numerical and simplified analytical investigation on RC frame behaviours under progressive collapse scenarios. Structures 2022, 44, 880–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1991-1-7; Eurocode 1: Actions on Structures—Part 1–7: General Actions—Accidental Actions. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- GSA. General Services Administration, Alternate Path Analysis and Design Guidelines for Progressive Collapse Resistance; GSA: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- UFC 4-023-03; Unified Facilities Criteria—Design of Buildings to Resist Progressive Collapse. DoD (Department of Defense): Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Qian, K.; Li, B. Performance of three-dimensional reinforced concrete beam column substructures under loss of a corner column scenario. J. Struct. Eng. 2013, 139, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, W.; Gu, L. A three-dimensional analytical framework for progressive collapse response of RC frames under column loss scenario. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 106, 112608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiroglu, S.; Sasani, M. Progressive collapse-resisting mechanisms of reinforced concrete structures and effects of initial damage locations. J. Struct. Eng. 2014, 140, 04013073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianidis, P.M.; Nethercot, D.A.; Izzuddin, B.A.; Elghazouli, A.Y. Study of the mechanics of progressive collapse with simplified beam models. Eng. Struct. 2016, 117, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, N.S.; Tan, K.H.; Lee, C.K. Effects of rotational capacity and horizontal restraint on development of catenary action in 2-D RC frames. Eng. Struct. 2017, 153, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Zhong, W.-H.; Meng, B.; Zheng, Y.-H.; Duan, S.-C. Effect of various boundary constraints on the collapse behavior of multi-story composite frames. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Li, B. Slab effects on response of reinforced concrete substructures after loss of corner column. ACI Struct. J. 2012, 109, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyvani, L.; Sasani, M.; Mirzaei, Y. Compressive membrane action in progressive collapse resistance of RC flat plates. Eng. Struct. 2014, 59, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianidis, P.M.; Nethercot, D.A. Simplified methods for progressive collapse assessment of frame structures. J. Struct. Eng. 2021, 147, 04021183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Li, S.; Wang, S. Effect of infill walls on mechanisms of steel frames against progressive collapse. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2019, 162, 105720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, T.; Zeng, B.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, L.; Chang, D. Progressive collapse resistance of prestressed concrete frame structures with infill walls considering instantaneous column failure. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2024, 33, e2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, J.G.P.; de Oliveira, I.X.; Shauer, N.; Oliveira, H.L.; Siqueira, G.H. Comparison of displacement-based and force-based formulations for modeling collapse of infill and bare frames. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 113923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Lan, X.; Li, Z.; Fu, F. Effects of steel braces on robustness of steel frames against progressive collapse. J. Struct. Eng. 2021, 147, 04021180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadallah, M.; Almustafa, M.K.; Dogangün, A.; Nehdi, M.L. Performance of X and inverted V bracing systems in controlling progressive collapse of reinforced concrete buildings. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 105812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianidis, P.; Bellos, J. Survey on the role of beam-column connections in the progressive collapse resistance of steel frame buildings. Buildings 2023, 13, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Li, L.; Zhong, W.; Tan, Z.; Du, Q. Improving Anti-Progressive Collapse Capacity of Welded Connections Based on Energy Dissipation Cover-Plates. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2021, 188, 107051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregoli, G.; Vasdravellis, G.; Karavasilis, T.L.; Cotsovos, D.M. Static and Dynamic Tests on Steel Joints Equipped with Novel Structural Details for Progressive Collapse Mitigation. Eng. Struct. 2021, 232, 111829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Li, H.; Liew, J.-Y.R.; Li, S.; Kong, D.-Y. Enhancing the Collapse Resistance of a Composite Subassembly with Fully Welded Joints Using Sliding Inner Cores. J. Struct. Eng. 2024, 150, 04024059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, I.; Yang, J.; Bhatta, S.; Wang, F.; Liu, Q.F. Factors influencing the progressive collapse resistance of RC frame structures. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 27, 100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolghadr Jahromi, H.; Vlassis, A.G.; Izzuddin, B.A. Modelling approaches for robustness assessment of multi-storey steel-composite buildings. Eng. Struct. 2013, 51, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrone, F.; Shan, L.; Kunnath, S.K. Modeling of RC Frame Buildings for Progressive Collapse Analysis. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2016, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.-J.; Yi, F.; Zhou, Y. Experimental Studies on Progressive Collapse Behavior of RC Frame Structures: Advances and Future Needs. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2021, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F. Progressive Collapse Analysis of High-Rise Building with 3-D Finite Element Modeling Method. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2009, 65, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senderovich, S.; Brodsky, A. Numerical analysis of RC frames under column removal: A review of current methods and development of a reduced-order approach. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 108, 112847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huanga, H.; Huang, M.; Zhang, W.; Guo, M.; Liu, B. Progressive collapse of multistory 3D reinforced concrete frame structures after the loss of an edge column. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2022, 18, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mander, J.B.; Priestley, M.J.N.; Park, R. Theoretical Stress–Strain Model for Concrete under Confinement. J. Struct. Eng. 1988, 114, 1804–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulay, T.; Priestley, M.J.N. Seismic Design of Reinforced Concrete and Masonry Buildings; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotakos, T.B.; Fardis, M.N. Deformation of Reinforced Concrete Members at Yielding and Ultimate. ACI Struct. J. 2001, 98, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Bayrak, O. Plastic Hinge Length of Reinforced Concrete Columns. ACI Struct. J. 2008, 105, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.D.; Park, R.; Priestley, M.J.N. Moment–Curvature Relationships for Reinforced Concrete Members. J. Struct. Eng. 2008, 134, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar]

- Park, R. Evaluation of Ductility of Structures and Structural Assemblages from Laboratory Testing. Bull. N. Z. Natl. Soc. Earthq. Eng. 1989, 22, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Kunnath, S.K. Simplified Progressive Collapse Simulation of RC Frame-Wall Structures. Eng. Struct. 2010, 32, 3153–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanishvili, S.; Agnew, E. Comparison of various procedures for progressive collapse analysis. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2006, 20, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, K.; El-Tawil, S. Pushdown resistance as a measure of robustness in progressive collapse analysis. Eng. Struct. 2011, 33, 2653–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinay, M.; Rao, P.K.R.; Dey, S.; Swaroop, A.H.L.; Sreenivasulu, A.; Rao, K.V. Evaluation of progressive collapse behavior in reinforced concrete buildings. Structures 2022, 45, 1902–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.-L.; Tan, L.; Long, B.; Kang, S.-B. Numerical investigations of progressive collapse behaviour of multi-storey reinforced concrete frames. Buildings 2023, 13, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Iyela, P.M.; Su, Y.; Atlaw, M.M.; Kang, S.-B. Numerical predictions of progressive collapse in reinforced concrete beam-column sub-assemblages: A focus on 3D multiscale modeling. Eng. Struct. 2024, 315, 118485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.-H.; Tan, Z.; Song, X.-Y.; Meng, B. Anti-Collapse Analysis of Unequal Span Steel Beam–Column Substructure Considering the Composite Effect of Floor Slabs. Adv. Steel Constr. 2019, 15, 377–385. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianidis, P.M.; Nethercot, D.A. Modelling of connection behaviour for progressive collapse analysis. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2015, 113, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkholy, S.; Shehada, A.; El-Ariss, B. Innovative scheme for RC building progressive collapse prevention. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 154, 107638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, S.; Kolchunov, V.; Fedorova, N.; Tuyen Vu, N. Experimental and numerical investigations of RC frame stability failure under a corner column removal scenario. Buildings 2023, 13, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mbah, T.K.; Stylianidis, P.M.; Ioannou, A.I. Comparative Study of Different Modelling Approaches for Progressive Collapse Analysis. Modelling 2025, 6, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040146

Mbah TK, Stylianidis PM, Ioannou AI. Comparative Study of Different Modelling Approaches for Progressive Collapse Analysis. Modelling. 2025; 6(4):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040146

Chicago/Turabian StyleMbah, Tony K., Panagiotis M. Stylianidis, and Anthos I. Ioannou. 2025. "Comparative Study of Different Modelling Approaches for Progressive Collapse Analysis" Modelling 6, no. 4: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040146

APA StyleMbah, T. K., Stylianidis, P. M., & Ioannou, A. I. (2025). Comparative Study of Different Modelling Approaches for Progressive Collapse Analysis. Modelling, 6(4), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040146