Stage IIIa Lung Cancer Treatment by the Combined Tomotherapy and Infusion of Autologous Peripheral-Blood-Mononuclear-Derived Lymphocytes: A Case Report of Aged Patient

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Preparation of Cytokine-Activated Autologous Lymphocytes

2.2. Treatment

2.3. Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CTC | Circulating Tumor Cells |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte |

| CTV | Clinical Target Volume |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| EGFR | Epithelial Growth Factor Receptor |

| EpCAM | Epithelial cell adhesion molecule |

| GTV | Gross Tumor Volume |

| ITV | Internal Target Volume |

| NKT | Natural Killer T-like (cells) |

| nPCT | Neoadjuvant PolyChemotherapy |

| NSCLC | Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer |

| PBMC | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| PTV | Planning Target Volume |

| TIL | Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte |

| TTV | Total Tumor Volume |

References

- Rodriguez Alvarez, A.A.R.; Yuming, S.; Kothari, J.; Digumarthy, S.R.; Byrne, N.M.; Li, Y.; Christiani, D.C. Sex disparities in lung cancer survival rates based on screening status. Lung Cancer 2022, 171, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, C.D.; Schiller, J.H.; Boffetta, P.; Cai, J.; Connolly, C.; Kerpel-Fronius, A.; Kitts, A.B.; Lam, D.C.L.; Mohan, A.; Myers, R.; et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) Early Detection and Screening Committee. Air pollution and lung cancer: A review by International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Early Detection and Screening Committee. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassymbekova, F.; Glushkova, N.; Dunenova, G.; Kaidarova, D.; Kissimova-Skarbek, K.; Wengler, A.; Zhetpisbayeva, I.; Shatkovskaya, O.; Andreyeva, O.; Davletov, K.; et al. Burden of major cancer types in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, A.M.; Laversanne, M.; Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Parkin, D.M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. The GLOBOCAN 2022 cancer estimates: Data sources, methods, and a snapshot of the cancer burden worldwide. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 156, 1336–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Wu, L.; Li, J.; Zheng, S.; Huang, M. A Visual Analysis of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Lung Cancer From 2013 to 2023. Cancer Control. 2024, 31, 10732748241266490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Qin, Y.; Shangguan, J.; Wei, D.; Wu, M.; Chen, D.; Yu, J. Sex-specific Difference for Small Cell Lung Cancer from Immunotherapy Advancement. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2024, 60 (Suppl. 2), S13–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, A.; Maji, A.; Potdar, P.D.; Singh, N.; Parikh, P.; Bisht, B.; Mukherjee, A.; Paul, M.K. Lung cancer immunotherapy: Progress, pitfalls, and promises. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shao, J.; Dong, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zou, Z.; Chen, F.; Yan, J.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Liu, B.; et al. Advanced HCC Patient Benefit From Neoantigen Reactive T Cells Based Immunotherapy: A Case Report. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 685126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Jiang, J.; Mao, W.; Bai, M.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, J. Treatment strategies and molecular mechanism of radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2024, 591, 216858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganina, A.; Askarov, M.; Kozina, L.; Karimova, M.; Shayakhmetov, Y.; Mukhamedzhanova, P.; Brimova, A.; Berikbol, D.; Chuvakova, E.; Zaripova, L.; et al. Prospects for Treatment of Lung Cancer Using Activated Lymphocytes Combined with Other Anti-Cancer Modalities. Adv. Respir. Med. 2024, 92, 504–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Li, H.; Ma, Q.; Liu, J.; Ren, F.; Song, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, K.; Li, N. Synergies between radiother-apy and immunotherapy: A systematic review from mechanism to clinical application. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1554499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnaik, A.A.; Hamid, O.; Khushalani, N.I.; Lewis, K.D.; Medina, T.; Kluger, H.M.; Thomas, S.S.; Domingo-Musibay, E.; Pavlick, A.C.; Whitman, E.D.; et al. Lifileucel, a Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Therapy, in Metastatic Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2656–2666, Erratum in J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2972. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.01866.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaria, R.; Knisely, A.; Vining, D.; Kopetz, S.; Overman, M.J.; Javle, M.; Antonoff, M.B.; Tzeng, C.D.; Wolff, R.A.; Pant, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e006822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, A.J.; Lee, S.M.; Doger de Spéville, B.; Gettinger, S.N.; Häfliger, S.; Sukari, A.; Papa, S.; Rodríguez-Moreno, J.F.; Graf Finckenstein, F.; Fiaz, R.; et al. Lifileucel, an Autologous Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Monotherapy, in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Resistant to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 1389–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, R.L.; Leidner, R.S.; Chung, C.H.; Jimeno, A.; Lee, S.M.; Sukari, A.; Nieva, J.J.; E Grilley-Olson, J.; Redman, R.; Wong, S.J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of one-time autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cell therapy in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzinger, C.; Zuckermann, A.; Kopp, C.; Schöllhammer, A.; Imhof, M.; Zwölfer, W.; Baumgartner, I.; Magometschnigg, H.; Weissinger, E.; Wolner, E. Treatment of non-healing skin ulcers with autologous activated mononuclear cells. Eur. J. Vasc. Surg. 1994, 8, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogado, J.; Pozo, F.; Troule, K.; Sánchez-Torres, J.M.; Romero-Laorden, N.; Mondejar, R.; Donnay, O.; Ballesteros, A.; Pacheco-Barcia, V.; Aspa, J.; et al. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Predict Therapeutic Efficacy of Immunotherapy in NSCLC. Cancers 2022, 14, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rosa, C.; Iommelli, F.; De Rosa, V.; Ercolano, G.; Sodano, F.; Tuccillo, C.; Amato, L.; Tirino, V.; Ariano, A.; Cimmino, F.; et al. PBMCs as Tool for Identification of Novel Immunotherapy Biomarkers in Lung Cancer. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyikanov, D.; Zaitsev, A.; Vasileva, T.; Wang, I.; Sokolov, A.A.; Bolshakov, E.S.; Frank, A.; Turova, P.; Golubeva, O.; Gantseva, A.; et al. Comprehensive peripheral blood immunoprofiling reveals five immuno-types with immunotherapy response characteristics in patients with cancer. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 759–779.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, K.K.; Cattaneo, C.M.; Weeber, F.; Chalabi, M.; van de Haar, J.; Fanchi, L.F.; Slagter, M.; van der Velden, D.L.; Kaing, S.; Kelderman, S.; et al. Generation of Tumor-Reactive T Cells by Co-culture of Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes and Tumor Organoids. Cell 2018, 174, 1586–1598.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Huang, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, C. Novel research model for in vitro immunotherapy: Co-culturing tumor organoids with peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, G.; Rath, B.; Stickler, S. Significance of circulating tumor cells in lung cancer: A narrative review. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2023, 12, 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.C.; Lai, G.G.Y.; Saw, S.P.L.; Chua, K.L.M.; Takano, A.; Ong, B.H.; Koh, T.P.T.; Jain, A.; Tan, W.L.; Ng, Q.S.; et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA with ultradeep sequencing of plasma cell-free DNA for monitoring minimal residual disease and early detection of recurrence in early-stage lung cancer. Cancer 2024, 130, 1758–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhood, B.; Najafi, M.; Mortezaee, K. CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: A review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 8509–8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.; Wu, C.J. Dynamics and specificities of T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2023, 23, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, T.; Almodovar, M.T. Immunotherapy in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: A Review. Port. J. Card. Thorac. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 30, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, K.; Kumar, P.; Choonara, Y.E. The paradigm of stem cell secretome in tissue repair and regeneration: Present and future perspectives. Wound Repair Regen. 2025, 33, e13251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenauer, M.; Mildner, M.; Hoetzenecker, K.; Zimmermann, M.; Podesser, B.K.; Sipos, W.; Berényi, E.; Dworschak, M.; Tschachler, E.; Gyöngyösi, M.; et al. Secretome of apoptotic peripheral blood cells (APOSEC) confers cytoprotection to cardiomyocytes and inhibits tissue remodelling after acute myocardial infarction: A preclinical study. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2011, 106, 1283–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovhannisyan, L.; Riether, C.; Aebersold, D.M.; Medová, M.; Zimmer, Y. CAR T cell-based immunotherapy and radiation therapy: Potential, promises and risks. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mireștean, C.C.; Iancu, R.I.; Iancu, D.T. Radiotherapy and Immunotherapy–A Future Partnership towards a New Standard. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, A.J.; Khasraw, M.; Byrne, J.D.; Reitman, Z.J. Enhancing adoptive cell therapy: Future strategies for immune cell radioprotection in neuro-oncology. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puebla-Osorio, N.; Fowlkes, N.W.; Barsoumian, H.B.; Xega, K.; Srivastava, G.; Kettlun-Leyton, C.; Nizzero, S.; Voss, T.; Riad, T.S.; Wong, C.; et al. Enhanced tumor control and survival in preclinical models with adoptive cell therapy preceded by low-dose radiotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1407143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obertopp, N.; Bekker, R.A.; Grass, G.D.; Zelenka, T.; Thomas, A.; Potez, M.; Ali, J.; Blauvelt, J.; Hall, A.M.; Hall, M.S.; et al. Local Single-Dose Radiation Improves Adoptive Cell Therapy With Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2025, 123, 1102–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Li, Y.; Muluh, T.A.; Wang, Y. Combination of CAR-T cell therapy and radiotherapy: Opportunities and challenges in solid tumors (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2023, 26, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Jiang, W.; Wang, J.; Zhou, B.; Ding, W.; Liu, S.; Huang, H.; Chen, G.; Sun, X. Application of individualized multimodal radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy in metastatic tumors. Front. Immunol. 2023, 13, 1106644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Wu, H.; Ma, D. Characterization of Circulating Tumor Cells in Breast Cancer Patients. Clin. Lab. 2023, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francini, S.; Duraes, M.; Rathat, G.; Macioce, V.; Mollevi, C.; Pages, L.; Ferrer, C.; Cayrefourcq, L.; Alix-Panabières, C. Circulating Tumor Cell Detection by Liquid Biopsy during Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer Surgery: A Pilot Study. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Huang, Q.; Bu, J.; Zhou, J.; Huang, Z.; Li, J. Circulating Tumor Cells Counting Act as a Potential Prognostic Factor in Cervical Cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 19, 1533033820957005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Xu, K.; Tartarone, A.; Santarpia, M.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, G. Circulating tumor cells can predict the prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer after resection: A retrospective study. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Date | Action |

|---|---|

| April–May 2024 | A central tumor of the left lung is revealed, with moderate mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Bronchoscopy. Histology: high-grade squamous cell intraepithelial carcinoma. |

| End of May 2024 | Multidisciplinary group concluded with diagnosis: Central cancer of the upper lobe of the left lung. T3N1M0 St IIIA. EGOC 0–1. Neoadjuvant polychemotherapy (nPCT) is recommended. |

| End of May–End of August | Four courses of nPCT: paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 +AUC5 (carboplatin). first course: 30.05–03.06.2024 second course: 20.06–24.06.2024 third course: 30.07–03.08.2024 fourth course: 20.08–24.08.2024 |

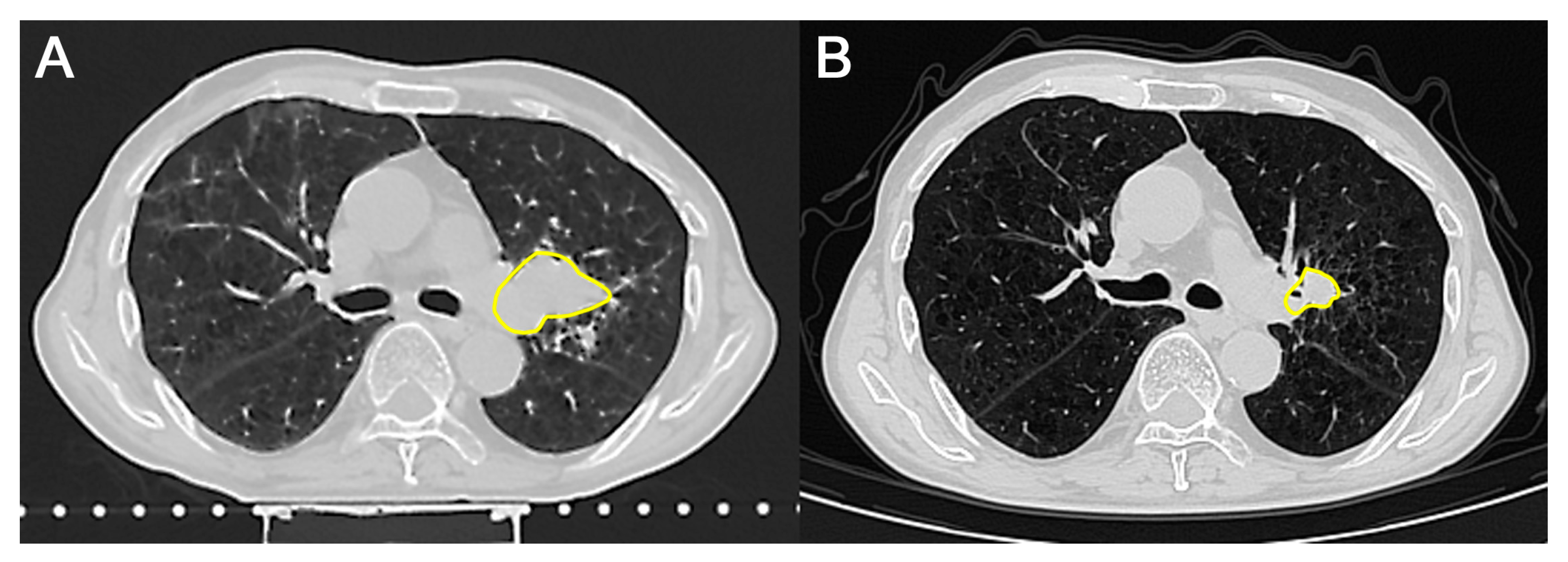

| 11 July 2024 | Chest CT scan shows positive dynamics after three courses of nPCT. |

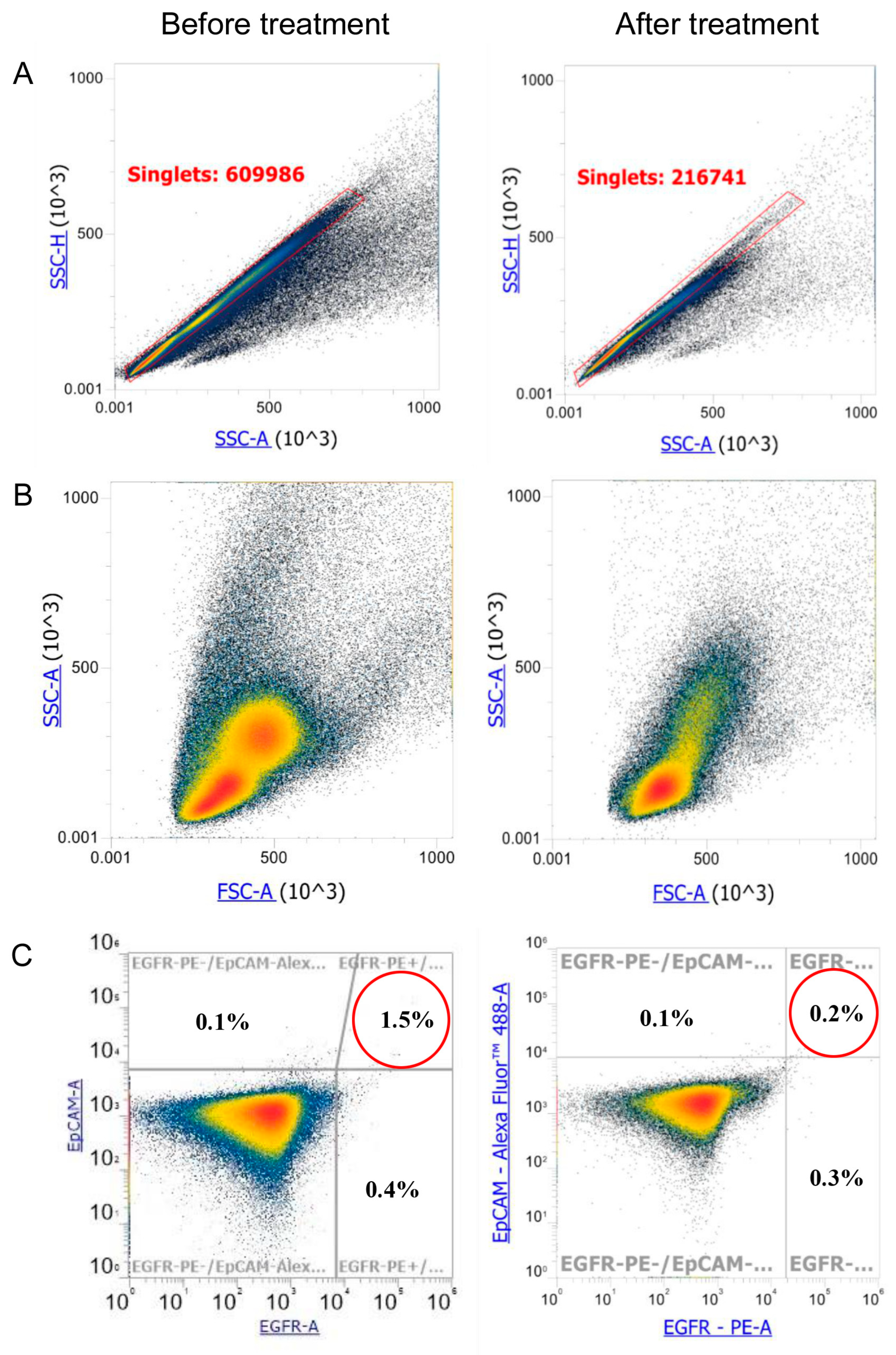

| 8 October 2024 | Chest CT scan shows negative dynamics due to an increase in the size of the mass. Single adenopathy of the tracheobronchial lymph nodes on the left. Consultation by radiologist. Circulating Tumor Cell (CTC) measurement (before combined treatment). |

| 17 October 2024 | Taking of PMBC for lymphocyte isolation and culture (apheresis). |

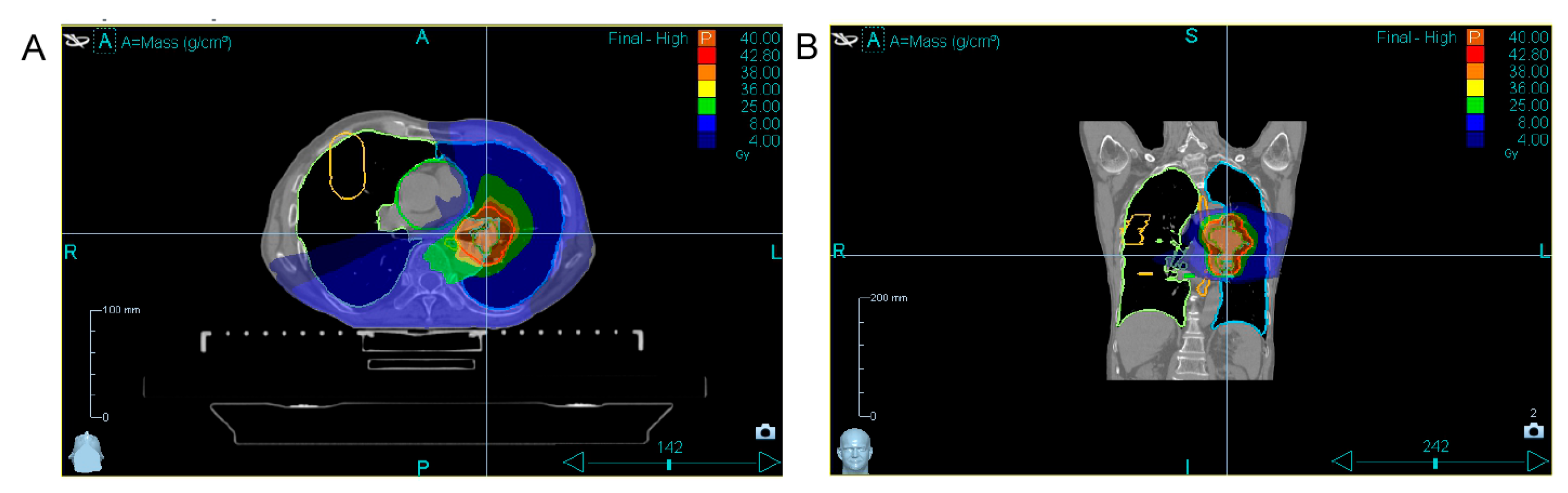

| 24 October– 4 November 2024 | Combined tomotherapy + immunotherapy treatment. Tomotherapy: ROD-5Gy, SOD-40Gy (8 fractions, 1 fraction per day except weekends). Immune cell therapy: 24 October—first infusion of autologous activated T lymphocytes. 31 October—second infusion of autologous activated T lymphocytes. |

| 19 December 2024 | Chest CT scan shows positive dynamics; the tumor decreased in size. CTC measurement (after combined treatment). |

| Stage | What Was Performed | What Was Used |

|---|---|---|

| Apheresis | Collection of mononuclear cells | The device for apheresis Terumo Optia |

| Culture | (1) Ficoll density gradient centrifugation, a layer with lymphocyte cells is separated (2) Preparation of cytokine cocktail for addition to culture medium (3) Cultivation of the lymphocytes in the cocktail in an incubator at 37 °C and 95% humidity, 95% air + 5% CO2 | Ficoll solution, density 1.077 DMEM medium, FBS serum, Cef 3 antibiotic Cytokines from day 0 in culture till infusion to the patient (also replenished at day 3 and day 10 in culture): IL-7 (20 ng/mL), IL-15 (20 ng/mL), SCF (20 ng/mL), Flt3 (20 ng/mL), IL-2 (20 ng/mL) Cytokines added one day before infusion to the patients: IL-12 (5 ng/mL) |

| Infusion | (1) Premedication: intravenous drip during ~20 min (2) Infusion of activated lymphocytes to the patient during ~2 h | 8 mg dexamethasone 200 mL 0.9% saline Blood infusion system (with filter) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brimova, A.; Ganina, A.; Kozina, L.; Berikbol, D.; Askarov, M.; Shayakhmetov, Y. Stage IIIa Lung Cancer Treatment by the Combined Tomotherapy and Infusion of Autologous Peripheral-Blood-Mononuclear-Derived Lymphocytes: A Case Report of Aged Patient. Transplantology 2025, 6, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6040037

Brimova A, Ganina A, Kozina L, Berikbol D, Askarov M, Shayakhmetov Y. Stage IIIa Lung Cancer Treatment by the Combined Tomotherapy and Infusion of Autologous Peripheral-Blood-Mononuclear-Derived Lymphocytes: A Case Report of Aged Patient. Transplantology. 2025; 6(4):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6040037

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrimova, Aigul, Anastasia Ganina, Larissa Kozina, Daulet Berikbol, Manarbek Askarov, and Yerzhan Shayakhmetov. 2025. "Stage IIIa Lung Cancer Treatment by the Combined Tomotherapy and Infusion of Autologous Peripheral-Blood-Mononuclear-Derived Lymphocytes: A Case Report of Aged Patient" Transplantology 6, no. 4: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6040037

APA StyleBrimova, A., Ganina, A., Kozina, L., Berikbol, D., Askarov, M., & Shayakhmetov, Y. (2025). Stage IIIa Lung Cancer Treatment by the Combined Tomotherapy and Infusion of Autologous Peripheral-Blood-Mononuclear-Derived Lymphocytes: A Case Report of Aged Patient. Transplantology, 6(4), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6040037