A Retrospective Analysis of a Single Center’s Experience with Hand-Assisted Retroperitoneoscopic Living Donor Nephrectomy: Perioperative Outcomes in 50 Consecutive Cases

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Imperative for Minimally Invasive Living Donor Nephrectomy

1.2. Comparing Surgical Approaches: Transperitoneal vs. Retroperitoneal

1.3. The Rationale for Hand-Assistance in Retroperitoneoscopic Surgery (HARP-DN)

1.4. Study Objective

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Cohort

2.2. Preoperative Donor Evaluation

- Medical and Psychosocial Assessment: A dedicated living donor team, comprising transplant surgeons, nephrologists, social workers, a living donor coordinator, performed a thorough medical history, a complete physical examination, and a detailed psychosocial assessment. This was to confirm the donor’s voluntary and altruistic motivation and to assess their social support system.

- Immunological Assessment: Standard immunological testing included ABO blood group typing, Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) typing, and panel reactive antibody (PRA) screening to determine donor–recipient compatibility.

- Laboratory Evaluation: A comprehensive panel of laboratory tests was performed, including a complete blood count, a comprehensive metabolic panel, liver function tests, a coagulation profile, viral serologies and urine analysis with microscopy.

- Anatomical and Functional Imaging: All donors underwent preoperative, contrast-enhanced, multiphasic computed tomography angiography (CT-AG) with 3D vascular and ureteral reconstruction. This imaging modality is the gold standard for providing a detailed roadmap of the renal parenchyma, delineating the number and course of renal arteries and veins, identifying any vascular or urological anomalies, and assessing the relationship of the kidneys to adjacent structures.

2.3. Kidney Selection Criteria

2.4. Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Donor Demographics: Age (years), gender, Body Mass Index (BMI, calculated as kg/m2), Preoperative serum creatinine levels (mg/dL) and anatomical abnormalities.

- Intraoperative Variables: Total operating time (minutes), defined as the duration from skin incision to final skin closure 1; warm ischemia time (WIT, seconds), defined as the interval from the clamping of the renal artery to the initiation of cold graft perfusion on the back table.

- Postoperative Clinical Course: Postoperative hemoglobin decrease (g/dL), calculated as the difference between the preoperative baseline and values at 24 h post-surgery; time to resumption of oral diet (days); total length of hospital stay (days); requirement for allogeneic blood transfusions (units); and type of analgesic requirement in the first 48 h post-surgery.

- Donor Renal Function: Serum creatinine (mg/dL) measured at the time of hospital discharge.

- Donor Complications: All perioperative complications occurring within 90 days of the surgical procedure were recorded.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Operative Technique

2.6.1. Patient Preparation and Positioning

2.6.2. Creation of Retroperitoneal Space and Port Placement

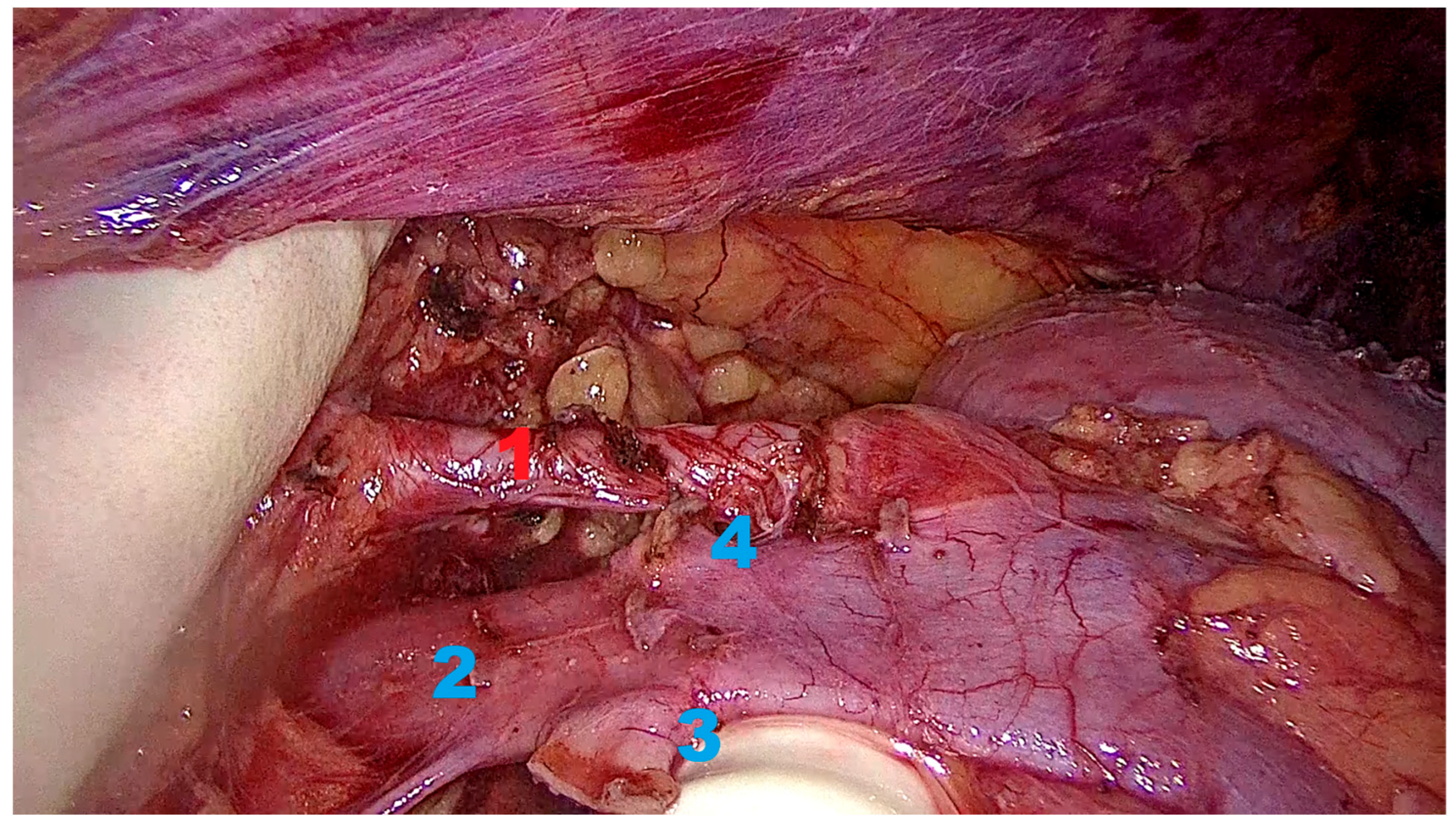

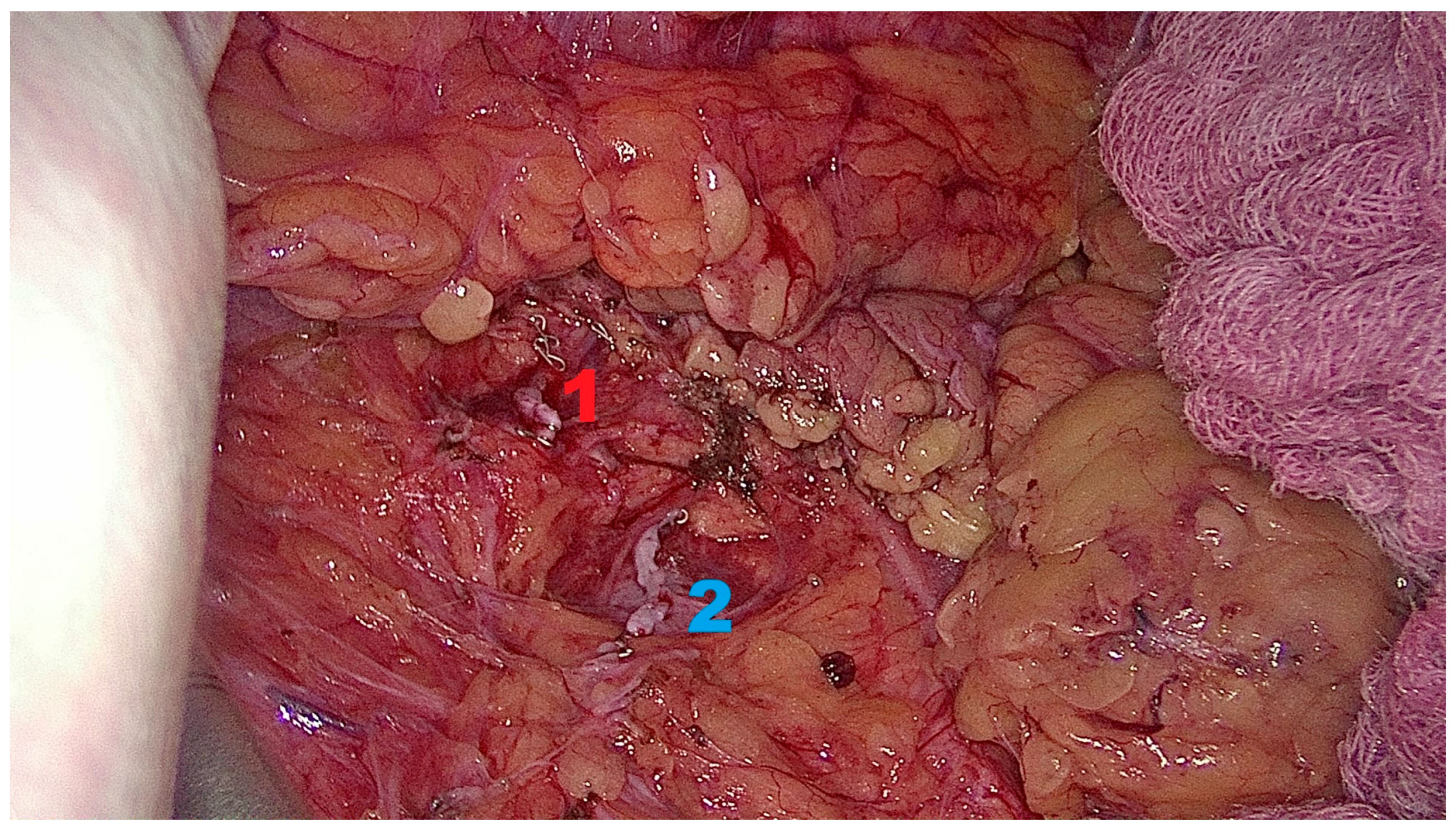

2.6.3. Kidney Mobilization and Hilar Dissection

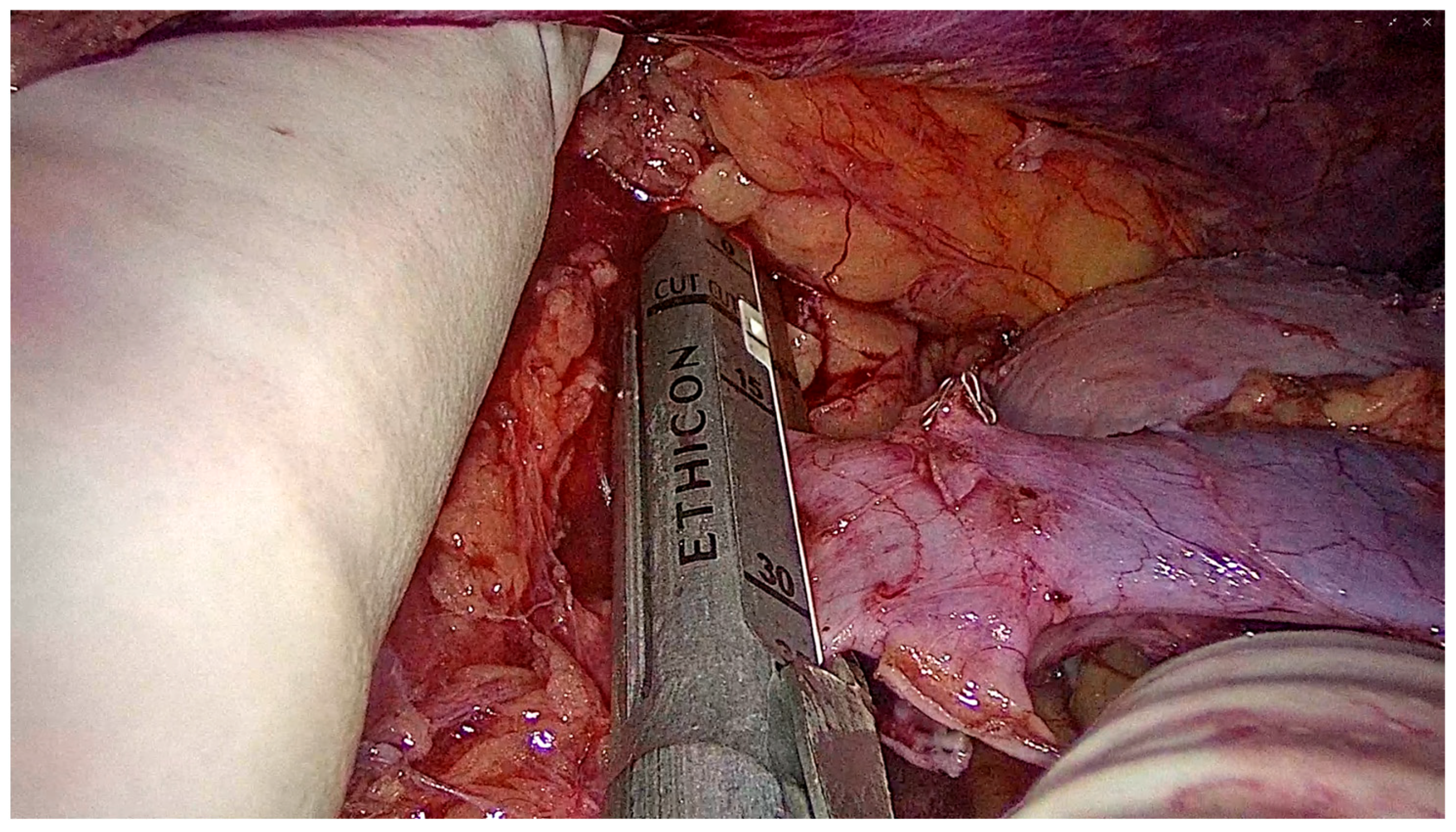

2.6.4. Graft Procurement and Extraction

2.6.5. Closure

3. Results

3.1. Donor Demographics and Operative Characteristics

3.2. Perioperative Outcome

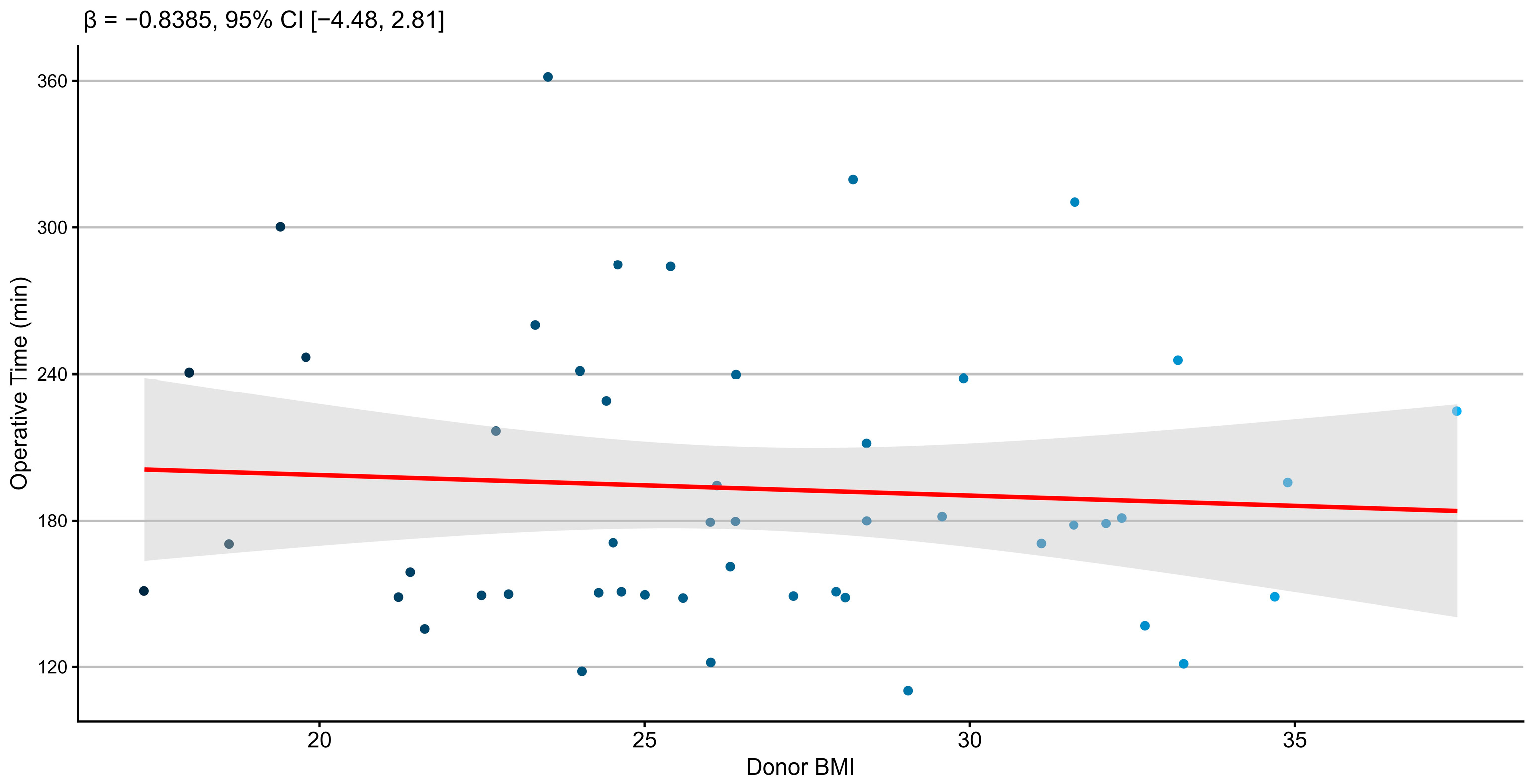

3.2.1. Association Between Donor BMI and Operative Time

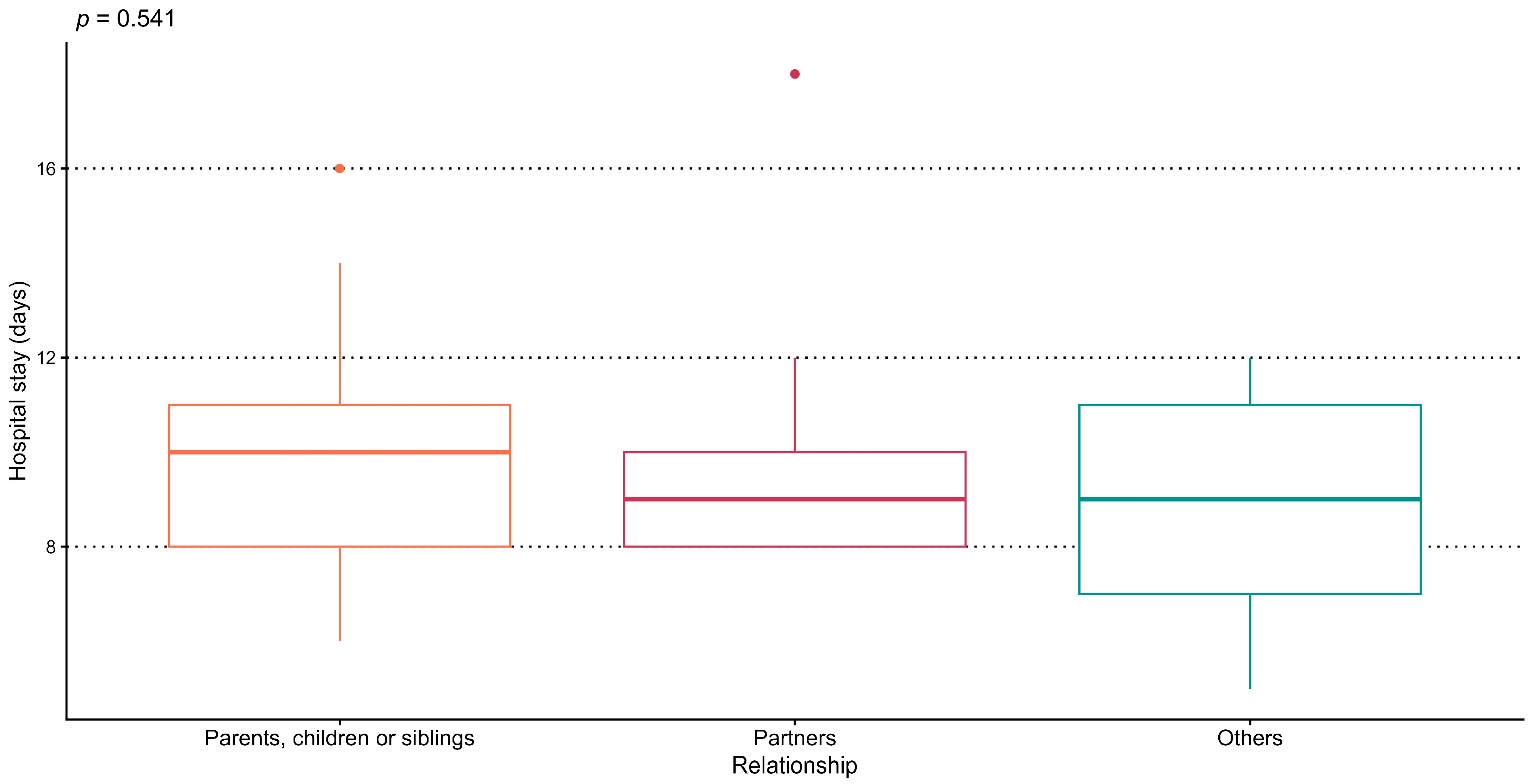

3.2.2. Association Between Donor–Recipient Relationship and Length of Hospital Stay

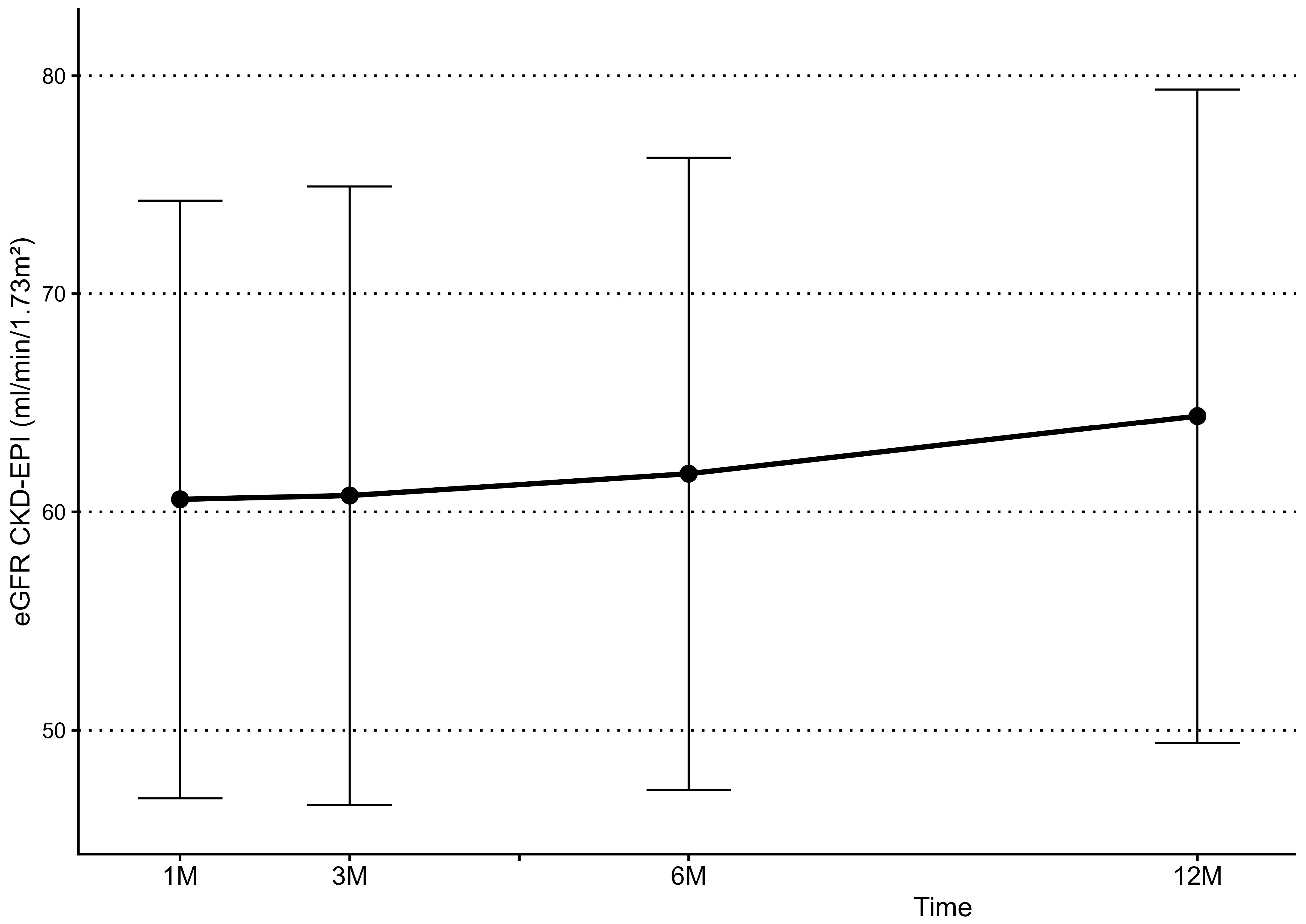

3.3. Kidney Function Follow-Up

3.4. Donor Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Toapanta, N.; Comas, J.; Revuelta, I.; Manonelles, A.; Facundo, C.; Pérez-Saez, M.J.; Vila, A.; Arcos, E.; Tort, J.; Giral, M.; et al. Benefits of Living Over Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation in Elderly Recipients. A Propensity Score Matched Analysis of a Large European Registry Cohort. Transplant. Int. 2024, 37, 13452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, J.; Luke, A.; Wallace, D.; Callaghan, C.; Sharples, L.D. Comparison of outcomes after living and deceased donor kidney transplantation: UK national cohort study. Br. J. Surg. 2025, 112, znaf162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigue, J.R.; Schold, J.D.; Mandelbrot, D.A. The decline in living kidney donation in the United States: Random variation or cause for concern? Transplantation 2013, 96, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentine, K.L.; Kasiske, B.L.; Levey, A.S.; Adams, P.L.; Alberú, J.; Bakr, M.A.; Gallon, L.; Garvey, C.A.; Guleria, S.; Li, P.K.-T.; et al. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors. Transplantation 2017, 101 (Suppl. S1), S1–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liyanage, L.; Muzaale, A.; Henderson, M. The true risk of living kidney donation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2019, 24, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.H.; Sanni, A.; Rix, D.A.; Soomro, N.A. Laparoscopic versus open nephrectomy for live kidney donors. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 11, CD006124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecoanet, P.; Chammas, M.F., Jr.; Sime, W.N.; Guillemin, F.; Karam, G.; Ladrière, M.; Eschwège, P.; Mitre, A.I.; Frimat, L.; Hubert, J. Minimally Invasive and Open Donor Nephrectomy: Lessons Learned From a French Multicenter Experience. Transplant. Proc. 2022, 54, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, L.E.; Ciseck, L.J.; Moore, R.G.; Cigarroa, F.G.; Kaufman, H.S.; Kavoussi, L.R. Laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy. Transplantation 1995, 60, 1047–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Dagnæs-Hansen, J.; Kristensen, G.H.; Stroomberg, H.V.; Sørensen, S.S.; Røder, M.A. Surgical Approaches and Outcomes in Living Donor Nephrectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Focus 2022, 8, 1795–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Xie, X.; Wang, H.; Yin, H.; Fang, C.; Dai, H. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic versus open donor nephrectomy for kidney transplantation: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2020, 12, 5993–6002. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, A.; Gupta, N.; Kumar, A.; Kapoor, R.; Dubey, D. Transperitoneal laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy: Current status. Indian J. Urol. 2007, 23, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Qi, P.; Ren, X.; Zheng, D.; He, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yue, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, N.; et al. Transperitoneal vs retroperitoneal laparoscopic radical nephrectomy: A double-arm, parallel-group randomized clinical trial. BMC Urol. 2024, 24, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Ochoa, C.; Feldman, L.S.; Nguan, C.; Monroy-Cuadros, M.; Arnold, J.; Boudville, N.; Cuerden, M.; Dipchand, C.; Eng, M.; Gill, J.; et al. Perioperative Complications During Living Donor Nephrectomy: Results From a Multicenter Cohort Study. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2019, 6, 2054358119857718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, W.; Gao, B.; Wang, G.; Lian, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y. Safety and Efficacy of Right Retroperitoneal Laparoscopic Live Donor Nephrectomy: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. Ann. Transplant. 2020, 25, e919284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohei, N.; Kazuya, O.; Hirai, T.; Miyauchi, Y.; Iida, S.; Shirakawa, H.; Shimizu, T.; Ishida, H.; Tanabe, K. Retroperitoneoscopic living donor nephrectomy: Experience of 425 cases at a single center. J. Endourol. 2010, 24, 1783–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, T.; Hotta, K.; Iwami, D.; Harada, H.; Morita, K.; Tanabe, T.; Sasaki, H.; Fukuzawa, N.; Seki, T.; Shinohara, N. Safety and Efficacy of Retroperitoneoscopic Living Donor Nephrectomy: Comparison of Early Complication, Donor and Recipient Outcome with Hand-Assisted Laparoscopic Living Donor Nephrectomy. J. Endourol. 2018, 32, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilidis, P.; Papalois, V. Retroperitoneoscopic Standard or Hand-Assisted Versus Laparoscopic Standard or Hand-Assisted Donor Nephrectomy: A Systematic Review and the First Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2020, 12, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadström, J.; Lindström, P. Hand-assisted retroperitoneoscopic living-donor nephrectomy: Initial 10 cases. Transplantation 2002, 73, 1839–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, M.E.; Vinson, A.J.; Skinner, T.A.A.; Kiberd, B.A.; Tennankore, K.K. The Impact of Combined Warm and Cold Ischemia Time on Post-transplant Outcomes. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2023, 10, 20543581231178960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosario Almonte, N.; Esqueda-Mendoza, A.; Mendoza Arcila, M.E.; Rendon Dosal, H.; Marique Canche, N.Z. Pure Laparoscopic Versus Hand-Assisted Nephrectomy: Comparative Outcomes in Living Kidney Donors. Cureus 2025, 17, e79191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmaraezy, A.; Abushouk, A.I.; Kamel, M.; Negida, A.; Naser, O. Should hand-assisted retroperitoneoscopic nephrectomy replace the standard laparoscopic technique for living donor nephrectomy? A meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2017, 40, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumdermpadetsuk, R.R.; Alvino, D.M.L.; Kaul, S.; Fleishman, A.; Eckhoff, D.E.; Pavlakis, M.; Lee, D.D. Impact of Donor Warm Ischemia Time on Graft Survival for Donation After Circulatory Death Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation 2025, 109, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, S.C.; Cho, E.; Foster, C.; Liao, P.; Bartlett, S.T. Laparoscopic donor nephrectomy: The University of Maryland 6-year experience. J. Urol. 2004, 171, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavic, M.S. Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery—HALS. Jpn. Soc. Lang. Sci. 2001, 5, 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.; Zheng, Q.; Xu, L.; Zhao, W.; Li, G.; Ding, G. Management of major vascular injury in laparoscopic urology. Laparosc. Endosc. Robot. Surg. 2020, 3, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, S.; Inoue, T.; Matsuura, S.; Horikawa, Y.; Kakinuma, H.; Saito, M.; Kumazawa, T.; Tsuchiya, N.; Satoh, S.; Habuchi, T. Outcome of right hand-assisted retroperitoneoscopic living donor nephrectomy. Urology 2006, 67, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjertsen, H.; Sandberg, A.K.; Wadström, J.; Tydén, G.; Ericzon, B.G. Introduction of hand-assisted retroperitoneoscopic living donor nephrectomy at Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge. Transplant. Proc. 2006, 38, 2644–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, E.B.; Soykan Barlas, I.; Dayangac, M. Hand-assisted retroperitoneoscopic donor nephrectomy offers more liberal use of right kidneys: Lessons learned from 565 cases—A retrospective single-center study. Transpl. Int. 2021, 34, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBray, B.J.; Thompson, J.J.; Shaffer, D.; Hale, D.A.; Rega, S.A.; Feurer, I.D.; Forbes, R.C. Incisional Hernia Development after Live Donor Nephrectomy: Impact of Surgical Technique. Kidney360 2023, 4, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, K.; Boudville, N.; Dew, M.A.; Geddes, C.; Gill, J.S.; Jassal, V.; Klarenbach, S.; Knoll, G.; Muirhead, N.; Prasad, G.V.R.; et al. The long-term quality of life of living kidney donors: A multicenter cohort study. Am. J. Transplant. 2011, 11, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dols, L.F.; Kok, N.F.; D’aNcona, F.C.; Klop, K.W.; Tran, T.K.; Langenhuijsen, J.F.; Terkivatan, T.; Dor, F.J.; Weimar, W.; Dooper, I.M.; et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing hand-assisted retroperitoneoscopic versus standard laparoscopic donor nephrectomy. Transplantation 2014, 97, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troppmann, C.; Daily, M.F.; McVicar, J.P.; Troppmann, K.M.; Perez, R.V. The transition from laparoscopic to retroperitoneoscopic live donor nephrectomy: A matched pair pilot study. Transplantation 2010, 89, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruszat, R.; Sulser, T.; Dickenmann, M.; Wolff, T.; Gürke, L.; Eugster, T.; Langer, I.; Vogelbach, P.; Steiger, J.; Gasser, T.C.; et al. Retroperitoneoscopic donor nephrectomy: Donor outcome and complication rate in comparison with three different techniques. World J. Urol. 2006, 24, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xie, J.L.; Zhou, C.; Chen, X. Technical modifications of hand-assisted retroperitoneoscopic living donor nephrectomy: A single-center experience. Transplant. Proc. 2012, 44, 1218–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Zheng, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y. The learning curve for modified hand-assisted retroperitoneoscopic living donor nephrectomy. BMC Urol. 2024, 24, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronek, J.P.; Chang, R.W.; Morsy, M.A. Hand-assisted retroperitoneoscopic living donor nephrectomy: First UK experience. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2006, 21, 2674–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundqvist, P.; Feuk, U.; Häggman, M.; Persson, A.E.; Stridsberg, M.; Wadström, J. Hand-assisted retroperitoneoscopic live donor nephrectomy in comparison to open and laparoscopic procedures: A prospective study on donor morbidity and kidney function. Transplantation 2004, 78, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dols, L.F.; Kok, N.F.; Terkivatan, T.; Tran, T.K.; D’ANcona, F.C.; Langenhuijsen, J.F.; Borg, I.R.Z.; Alwayn, I.P.; Hendriks, M.P.; Dooper, I.M.; et al. Hand-assisted retroperitoneoscopic versus standard laparoscopic donor nephrectomy: HARP-trial. BMC Surg. 2010, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjøen, G.; Øyen, O.; Holdaas, H.; Midtvedt, K.; Line, P.D. Morbidity and mortality in 1022 consecutive living donor nephrectomies: Benefits of a living donor registry. Transplantation 2009, 88, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klop, K.W.J.; Kok, N.F.M.; Dols, L.F.C.; Dor, F.J.M.F.; Tran, K.T.C.; Terkivatan, T.; Weimar, W.; Ijzermans, J.N.M. Can right-sided hand-assisted retroperitoneoscopic donor nephrectomy be advocated above standard laparoscopic donor nephrectomy: A randomized pilot study. Transpl. Int. 2014, 27, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercimek, M.N.; Ozden, E.; Gulsen, M.; Kalayci, O.; Yakupoglu, Y.K.Y.; Bostancı, Y.; Sarikaya, S. The learning curve for pure retroperitoneoscopic donor nephrectomy by using cumulative sum analysis. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2023, 17, E369–E373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kacar, S.; Gurkan, A.; Akman, F.; Varýlsuha, C.; Karaca, C.; Karaoglan, M. Multiple renal arteries in laparoscopic donor nephrectomy. Ann. Transplant. 2005, 10, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Bhattacharya, S.; Sirota, M.; Laiudompitak, S.; Schaefer, H.; Thomson, E.; Wiser, J.; Sarwal, M.M.; Butte, A.J. Assessment of Postdonation Outcomes in US Living Kidney Donors Using Publicly Available Data Sets. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e191851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, G.; Hedican, S.P.; Gee, J.R.; Bruskewitz, R.C.; Nakada, S.Y. Meta-analysis of the complications of laparoscopic renal surgery: Comparison of procedures and techniques. J. Urol. 2006, 175, 1208–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matas, A.J.; Rule, A.D. Long-term Medical Outcomes of Living Kidney Donors. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2022, 97, 2107–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 47.2 ± 12.6 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 32 (64%) |

| Male | 18 (36%) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 26.38 ± 4.87 |

| Preoperative Serum Creatinine (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 0.80 ± 0.13 |

| Renal Arteries (from CT-AG), n (%) | |

| Single | 41 (82%) |

| Multiple (≥2) | 9 (18%) |

| Outcome Measure | Value |

|---|---|

| Operating Time (min), mean ± SD | 192.4 ± 57.7 |

| Warm Ischemia Time (s), median (IQR) | 110 (90–150) |

| Intraoperative Complications, n (%) | 2 (4%) |

| Renal vein bleeding (intraoperative) | 1 (50%) |

| Epigastric vessels bleeding (revision) | 1 (50%) |

| Conversion to Open Surgery, n (%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hemoglobin Decrease at 24 h (g/dL), mean ± SD | 2.38 ± 0.90 g/dL |

| Blood Transfusion Required, n (%) | 2 (4%) |

| Time to Oral Diet (hours), median (IQR) | 26 (20–40) |

| Analgesics used in early postoperative setting, n (%) | |

| Metamizole | 31 (62%) |

| Pethidine | 19 (38%) |

| Length of Hospital Stay (days), mean ± SD | 9.6 ± 2.4 |

| Released on POD (days), mean ± SD | 7.6 ± 2.4 |

| Outcome Measure | Value |

|---|---|

| Pre-operative Serum Creatinine (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 0.8 ± 0.13 mg/dL |

| Pre-operative eGFR (CKD-EPI) (ml/min/m2), mean ± SD | 100.6 ± 13.43 mL/min/m2 |

| Serum Creatinine at Discharge (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 1.09 ± 0.30 mg/dL |

| eGFR (CKD-EPI) at Discharge (ml/min/m2), mean ± SD | 76.26 ± 25.21 mL/min/m2 |

| Serum Creatinine—1 month after nephrectomy (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 1.26 ± 0.33 mg/dL |

| eGFR (CKD-EPI)—1 month after nephrectomy (ml/min/m2), mean ± SD | 58.58 ± 21.31 mL/min/m2 |

| Serum Creatinine—6 months after nephrectomy (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 1.21 ± 0.24 mg/dL |

| eGFR (CKD-EPI)—6 months after nephrectomy (ml/min/m2), mean ± SD | 63.01 ± 15.71 mL/min/m2 |

| Serum Creatinine—12 months after nephrectomy (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 1.20 ± 0.21 mg/dL |

| eGFR (CKD-EPI)—12 months after nephrectomy (ml/min/m2), mean ± SD | 63.52 ± 13.71 mL/min/m2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adandedjan, D.; Gala, I.; Kalanin, R.; Baltesova, T.; Katuchova, J.; Bena, L.; Hulik, S. A Retrospective Analysis of a Single Center’s Experience with Hand-Assisted Retroperitoneoscopic Living Donor Nephrectomy: Perioperative Outcomes in 50 Consecutive Cases. Transplantology 2025, 6, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6040038

Adandedjan D, Gala I, Kalanin R, Baltesova T, Katuchova J, Bena L, Hulik S. A Retrospective Analysis of a Single Center’s Experience with Hand-Assisted Retroperitoneoscopic Living Donor Nephrectomy: Perioperative Outcomes in 50 Consecutive Cases. Transplantology. 2025; 6(4):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6040038

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdandedjan, David, Igor Gala, Rastislav Kalanin, Tatiana Baltesova, Jana Katuchova, Luboslav Bena, and Stefan Hulik. 2025. "A Retrospective Analysis of a Single Center’s Experience with Hand-Assisted Retroperitoneoscopic Living Donor Nephrectomy: Perioperative Outcomes in 50 Consecutive Cases" Transplantology 6, no. 4: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6040038

APA StyleAdandedjan, D., Gala, I., Kalanin, R., Baltesova, T., Katuchova, J., Bena, L., & Hulik, S. (2025). A Retrospective Analysis of a Single Center’s Experience with Hand-Assisted Retroperitoneoscopic Living Donor Nephrectomy: Perioperative Outcomes in 50 Consecutive Cases. Transplantology, 6(4), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/transplantology6040038