Abstract

A heart transplantation (HT) is performed when a patient’s heart health has been severely compromised. However, the health care needs of a patient throughout the transplantation process are also significant. In order to investigate these postoperative heart transplant challenges, this study has two objectives: to find which psychosocial and psychiatric variables relate to good prognosis at the end of the followup period and to assess cognitive status and quality of life at the end of the study. Therefore, we divided the sample according to the completion success and then studied and compared the differences in participants’ personality, coping mechanisms, locus of control, clinical, and epidemiological information. Cognitive function and quality of life assessments were also undertaken for participants who completed their followup period. Higher significant differences were found in openness to experience (personality), self-perceived support (locus of control), and positive reinterpretation (coping) among those who completed the followup period. On the other hand, a higher age and current or historical psychiatric diagnoses were more prevalent in the group who did not complete the followup period. Our assessment of the participants after the followup period showed normal levels of cognitive function and quality of life.

1. Introduction

A heart transplant (HT) is the indicated treatment for either severe heart disease or a refractory heart condition that has not responded to other treatments [1]. The number of people requiring this intervention has increased due to improvements in cardiac treatment, higher long-term survival rates in patients with cardiac diseases, and greater life expectancy. However, the number of heart donors has remained the same [2]. Therefore, the whole transplantation process, from the selection of individuals to the long-term health status, needs to be improved to make every transplantation successful.

Despite the potential health benefits of HTs, the procedure has multiple risks which must be addressed to decrease postoperative mortality. Due to its medical history, mortality risk, and the physical impact, HT has been reported as a chronic high-stress factor. The most reported consequences of HT include spiritual, psychological, and social impacts; the relationship between the donor and their new organ, quality of life, and coping mechanisms are also affected by HT [3]. The most relevant mental-health-related factors to consider following an HT procedure are psychiatric diagnoses, substance disorders, coping strategies, social support, and personality [4].

It has been widely reported that mental health conditions reduce life expectancy for a variety of reasons, such as mood, anxiety, and social support, because they affect health behavior. Consequently, it has been reported that mortality rates increase from 16% to almost 50% in the population with mental health disorders (either prior to the HT or onset after the surgery). Therefore, it is imperative to monitor these variables to maximize the chance of HT success [1].

However, the influence of these mental-health-related variables on long-term treatment remains unclear. It has been reported that the length of the treatment has an effect on the number of people who complete it. This happens because adherence to the recommended treatment tends to be lost, particularly when a change of habits is required. This is mediated by the patient’s personal variables, doctor–patient relationship, treatment, and illness characteristics [5].

First, this study aims to analyze which types of psychosocial and psychiatric features are associated with a completed long-term followup after an HT. Second, this study assesses cognitive status and quality of life eight years after the HT intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This quasi-experimentally designed research is based on a previous study, in which the original sample was assessed before and 12 months after an HT [4]. In this study, the 12-month followup period used in the previous research design was increased to a mean time of 99 months (eight years). After this followup period, the remaining sample was assessed once more. Finally, the original sample was divided into two groups and compared.

2.2. Sample

The candidates were patients from the cardiac unit of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona. A nonprobability sampling method was used. The patients were included in the study between January 2006 and December 2012.

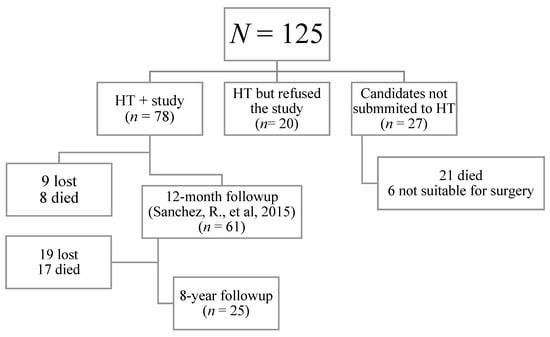

One hundred and twenty-five adult patients were suitable for the cardiac procedure, as shown in Figure 1. Seventy-eight patients were available for the study, 25 (32%) ended the eight-year followup and 53 (68%) did not. Patients withdrew from the experiment due to death (25 patients) or because they were no longer committed to the study (28 patients). Finally, the sample was divided into two groups: those who ended the followup (n = 25) and those who withdrew (n = 53).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the candidates.

The research met the ethical criteria of the Hospital Committee and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The patients had to fulfill the following inclusion criteria: (A) age between 18 and 75, (B) no intellectual disabilities or cognitive impairments, (C) signed consent form, and (D) fulfilment of general medical criteria for surgery suitability (having severe refractory heart failure, among other medical and surgical variables).

2.3. Procedure

The assessment consisted of the following instruments:

- a.

- Ad hoc clinical, epidemiological, and psychosocial form with medical and mental health history.

- b.

- Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID) and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM)—axis I disorders clinical version and axis II personality disorders of the American Psychiatry Association [6,7,8].

- c.

- Five-Factor Inventory, Revised Edition (NEO-PI-R), a self-reported 60-item questionnaire measuring extraversion, neuroticism, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. The Spanish validation of the inventory was used [9].

- d.

- The Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC), a self-reported 18-item Likert questionnaire with answers ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). This test assesses a person’s agency level in a variety of attributional styles. A “condition-specific” version of this questionnaire was used because it is suited to people with medical diseases. Those items can be applied to different topics: doctors, high-status people, chance, and internality. The Spanish adaptation of the questionnaire was used [10,11]

- e.

- Coping questionnaire (COPE), a 60-item self-reported questionnaire that assesses different ways of coping with problems and stress. Normally, COPE has 15 scales, but Gutiérrez et al. (2007) obtained three robust and generalizable second-order dimensions: engagement, disengagement, and help seeking. These scales were used in our study. The Spanish validation of the questionnaire was used [12,13].

- f.

- HADS, a 14-item self-report screening scale. It has three scales: global, depression, and anxiety. It reports the possible presence of clinically meaningful degrees of mood and anxiety disorders. The cutoff is 12 points for the global scale and 8 for the anxiety and depression scale [14,15].

- g.

- The Spanish version of a family functioning questionnaire (APGAR). This questionnaire can be administrated by a health-care professional or be self-reported. It has five Likert items and assesses the perception of the patient of their family functioning. The total score ranges from 1 (severe family dysfunction) to 10 (totally functional) [16].

- h.

- The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). This screening is administrated by a health-care professional and indicates the current severity of cognitive impairment. The normality cutoff is 27 points. The Spanish validation of the questionnaire was used [17].

- i.

- EuroQol-5D, a questionnaire that can be administrated by a health-care professional or be self-reported. It has five item dimensions: mobility, self-care, daily activities, pain, and mood. Additionally, it has one scale that estimates self-health perception status from 0, the worst, to 100, the best. The Spanish version of the questionnaire was used [18].

Patients were assessed on three occasions: (1) on the waiting list, baseline; (2) 12 months after the HT; (3) a mean time of eight years after the HT. On the first occasion, the clinical, epidemiological, and psychosocial data were collected. Additionally, SCID, DSM, NEO-PI-R, MHLC, COPE, HADS, and APGAR instruments were used. On the second occasion, HADS and APGAR questionnaires were administrated again. On the third occasion, the MMSE and EuroQol-5D tests were conducted.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Due to the lack of available samples from the group who withdrew, statistical analyses were performed using nonparametrical tests. If the variables were nominal, chi-squared tests were conducted. Additionally, to increase the scope of this study, the effect size was assessed using a Cramer’s test. If the variables were quantitative, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. All the statistical procedures were carried out using JASP 0.14.1 software (JASP team, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

3. Results

One hundred and twenty-five adult patients were suitable candidates for the cardiac procedure, as shown in Figure 1. Seventy-eight patients were available for sampling; 25 (32%) completed the eight-year followup, and 53 (68%) did not. Patients withdrew from the experiment due to death (25 patients) or because they were no longer committed to the study (28 patients).

The epidemiological and clinical characteristics of both groups (completed and withdrew) and their differences are shown in Table 1. A significant difference was found for age (when the surgery was performed). Although the current and historical psychiatric diagnoses were both significant variables, the size of the effect was greater in the historical rather than the current diagnosis.

Table 1.

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics.

The results of the HADS and APGAR questionnaires were split between those who ended the followup and those who did not. At the baseline, none of the participants showed significant differences. However, only the comparison between the results assessed at that moment is shown, as it was not possible to assess the group that withdrew from followup, and the available sample after 12 months was not sufficient for a comparison to be made. However, the APGAR score of the group that completed the followup, at the 12-month assessment, decreased to 8.0 ± 2.58.

The results of the tests completed during the waiting list are shown in Table 2. Personality and openness to experience were significantly higher among those who completed the follow-up period.

Table 2.

Results of the test of the waiting list.

Regarding support, there were statistically significant differences when considering the whole questionnaire; however, when performing a qualitative analysis, the difference occurs mainly in self-perceived support. Therefore, the statistical difference may be caused by self-perceived support. The effect size shown in this variable was 0.571. The interpretation of the effect size was condition specific, so the value in this field should be interpreted as a large effect.

Additionally, none of the scales of the coping system showed statistically significant differences except the positive reinterpretation, which was greater among those who completed the followup period.

Finally, the following tests were assessed only at the end of the followup period. The Mini-Mental State Examination showed a total score of 28.52 ± 1.5 (the total possible score is between 0 and 30). Among the different scales of the EuroQol-5D, only the EVA scale was used as a global indicator of the perceived self-health status. Its final score was 71.36 ± 20.82 (the total possible score is between 0 and 100).

4. Discussion

We found statistically significant differences in two of the most systematically reported variables, age and psychiatric diagnosis. This demonstrates that all variables do not have the same predictive power, and those top variables keep their prediction power even in small samples.

In a previous paper, Sánchez [4] studied the effect of neuroticism in the HADS score. Here, despite the evidence relating a poor prognosis to neuroticism, no difference was found. However, openness to experience and positive reinterpretation did have statistical differences. Greater scores for these areas were found among those who completed the study. This could be related to a better approach to, and understanding of, the surgery and its consequences.

This shows us that there are variables related to a poor prognosis (neuroticism) and, even when these variables are not present, a good prognosis is not necessarily implied because there are other variables related to a good prognosis (i.e., openness to experience and positive reinterpretation).

Adherence to the treatment, as expected, reduced over time. Additionally, since the medical team, the treatment, and the illness remained similar across all the participants, personal characteristics should explain the variability in adherence. We found statistical differences in openness to experience and positive reinterpretation. Those are variables that already have been reported as mediators of adherence, indicating good mood, adjustment to the illness, and quality of life [19].

Both current and past psychiatric diagnoses have been identified as relevant variables. This follows the current evidence. However, the effect size scores were higher in the previous diagnosis (0.41) than the current one (0.36). In future studies, these differences could be examined.

In light of the results gathered, the outcome was better when the age of the participant receiving an HT was lower. This could be related to better physical health but also to greater life expectancy and motivation [3].

On the other hand, positive perception of the prognosis seems to be related to a better treatment outcome, as the quality of the prognosis itself is not relevant if it is perceived as futile by the patient. This reveals the importance of the patient’s perception of their objective medical status. This may also explain the differences in social support, given that a favorable prognosis is associated with a positive self-perceived support.

The etiology of cardiac disease and the age of the illness’ onset have been widely reported as a notable sources of information for generating a prognosis. However, in our study, the influence of cardiac diagnosis was not as expected. An analysis with a large enough sample to perform parametrical statistics may yield different results.

Previous heart surgery seemed to have very little influence among both groups (Cramer = 0.007), even though the qualitative analysis showed that a greater number of people with prior cardiac surgery did not complete the study. Additionally, none of the scores of the HADS were significant, nor did they reach the cutoffs to be clinically depressed or anxious. However, the HADS scores of the sample reduced slightly a year after the surgery, so their anxiety and depression, albeit not clinically diagnosed in the first instance, improved.

In every group, assessment showed that the participants’ families were fully functional. However, there was a slight decrease between the preoperative scores and the 12-month postoperative scores. This might be explained by the consequences of the transplantation, such as the stress and new requirements placed upon the individuals and their families.

In the long term, both the cognitive function and the perceived health status remained preserved. The tests showed that there was no problem with cognitive function in the participants, since every mark was above the cutoff of 27. Additionally, the perceived health status was, on average, reported as good (the average score was 71 on a scale from 0 to 100).

Finally, some cardiac disease etiologies can affect quality of life even though the patient has been transplanted, such as systemic conditions [20]. However, in our final sample, all the participants reported a good quality of life regardless of the etiology.

Limitations

Since this research depends on the functioning of the heart transplant facilities, the methodology was affected. For example, a small sample was collected, and the characteristics and personal variables relied on the inclusion criteria of the health system and its functioning.

In addition, one goal of this study was to increase the length of the followup. However, this caused the experimental mortality to noticeably increase. Therefore, nonparametrical tests were necessary. In future investigations, the sample should be improved. Additionally, some way to either prevent withdrawal or understand why participants withdrew from the study should be implemented.

This study aimed to study the differences between two groups: those who completed the followup and those who did not. Sorting the sample from the data gathered at the end of the followup may be susceptible to bias. Furthermore, since there was a group that withdrew, there was missing information; therefore, the comparison between groups may have had some irregularities.

On the other hand, a better assessment at the end of the followup should be made using the same tests in every assessment moment.

5. Conclusions

The influence of negative variables such as mental health diagnosis has been widely reported. However, the lack of those variables may not be enough to explain a good prognosis, since openness to experience seems to be related to positive outcomes, and neuroticism is linked to unfavorable outcomes. In addition, two of the most systematically reported variables, age and psychiatric diagnosis, were significant in our sample. This could be caused by the differential weight of variables and their causality with regard to the final status of the patient, as most predictive variables keep their causality even in small samples. Finally, the reported quality of life of those who completed the followup was good and their cognitive functioning was preserved.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; L.P. and R.T.; methodology H.L.; L.P. and R.T.; validation; L.P. and H.L.; formal analysis; R.T.; investigation; R.S.-G.; M.C.; O.C.; B.d.H.-B.; M.A.C. and M.F.; resources; M.C. and M.A.C.; data curation; R.T.; B.d.H.-B. and O.C.; writing—original draft preparation; R.T.; writing—review and editing; R.T. and L.P.; visualization; R.T.; supervision; L.P. and H.L.; project administration; L.P.; funding acquisition; L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Hugo López Pelayo received funding from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Instituto de Salud Carlos III through a Juan Rodes contract (JR19/00025) to Hugo López-Pelayo, FEDER.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clinic of Barcelona (File number HCB/2016/0218 approved in April 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available at the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Spaderna, H.; Smits, J.; Rahmmel, A.; Weidner, G. Psychosocial and behavioral factors in heart transplant candidates—An overview. Transpl. Int. 2007, 20, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dornelas, E.; Sears, S. Living with heart despite recurrent challenges: Psychological care for adults with advanced cardiac disease. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarasa, M.M.; Olano-Lizarraga, M. Exploring the experience of living with a heart transplant: A systematic review of the literature. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2019, 42, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sánchez, R.; Baillès, E.; Peri, J.M.; Bastidas, A.; Pérez-Villa, F.; Bulbena, A.; Pintor, L. Assessment of psychosocial factors and predictors of psychopathology in a sample of heart transplantation recipients: A prospective 12-month follow-up. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2016, 38, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amigo, I. La adhesión a los tratamientos terapéuticos. In Manual de Psicología de la Salud, 4th ed.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 230–233. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatry Association. Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales (DSM-IV-TR), 4th ed.; Masson: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- First, M.B.; Gibbon, M.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Benjamin, L.S. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II); American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; Masson: Barcelona, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- First, M.B.; Spitzer, R.L.; Gibbon, M.; Williams, J.B.W. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Clinician Version (SCID-CV); American Psychiatry Association Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 1997; Masson: Barcelona, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Aluja, A.; García, O.; Rossier, J.; García, L.F. Comparison of the NEO-FFI, the NEO-FFI-R and an alternative short version of the NEO-PI-R (NEO-60) in Swiss and Spanish samples. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2005, 38, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallston, K.A.; Stein, M.J.; Smith, C.A. Form C of the MHLC scales: A condition-specific measure of locus of control. J. Pers. Assess. 1994, 63, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastor, M.A.; López, S.; Rodríguez, J.; Sánchez, S.; Salas, E.; Pascual, E. Expectativas de control sobre la experiencia de dolor: Adaptación y análisis preliminar de la escala Multidimensional de Locus de Control de Salud. Rev. Psicol. Salud 1990, 2, 91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, F.; Peri, J.M.; Torres, X.; Caseras, X.; Valdés, M. Three dimensions of coping and a look at their evolutionary origin. J. Res. Personal. 2007, 41, 1032–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.; Cruzado, J.A. La evaluación del afrontamiento: Adaptación española del Cuestionario COPE con una muestra de estudiantes universitarios. Análisis Modif. Conducta 1997, 23, 797–830. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Herrero, M.J.; Blanch, J.; Peri, J.M.; De Pablo, J.; Pintor, L.; Bulbena, A. A validation study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in a Spanish population. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2003, 25, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellón, J.A.; Delgado, A.; Luna, J.D.; Lardelli, P. Validity and reliability of the Apgar-family questionnaire on family function. Aten. Primaria 1996, 18, 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Blesa, R.; Pujol, M.; Aguilar, M.; Santacruz, P.; Bertran-Serra, I.; Hernández, G.; Peña-Casanova, J. Clinical validity of the ‘mini-mental state’ for Spanish speaking communities. Neuropsychologia 2001, 39, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdman, M.; Badia, X.; Berra, S. El EuroQol-5D: Una alternativa sencilla para la medición de la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en atención primaria. Aten. Primaria 2001, 28, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leedham, B.; Meyerowitz, B.E.; Muirhead, J.; Frist, W.H. Positive expectations predict health after heart transplantation. Health Psychol. 1995, 14, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nora, C.; Paldino, A.; Miani, D.; Finato, N.; Pizzolitto, S.; De Maglio, G.; Vendramin, I.; Sponga, S.; Nalli, C.; Sinagra, G.; et al. Heart Transplantation in Kearns-Sayre Syndrome. Transplantation 2019, 103, e393–e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).