Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Male Reproductive Health: A Mini Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

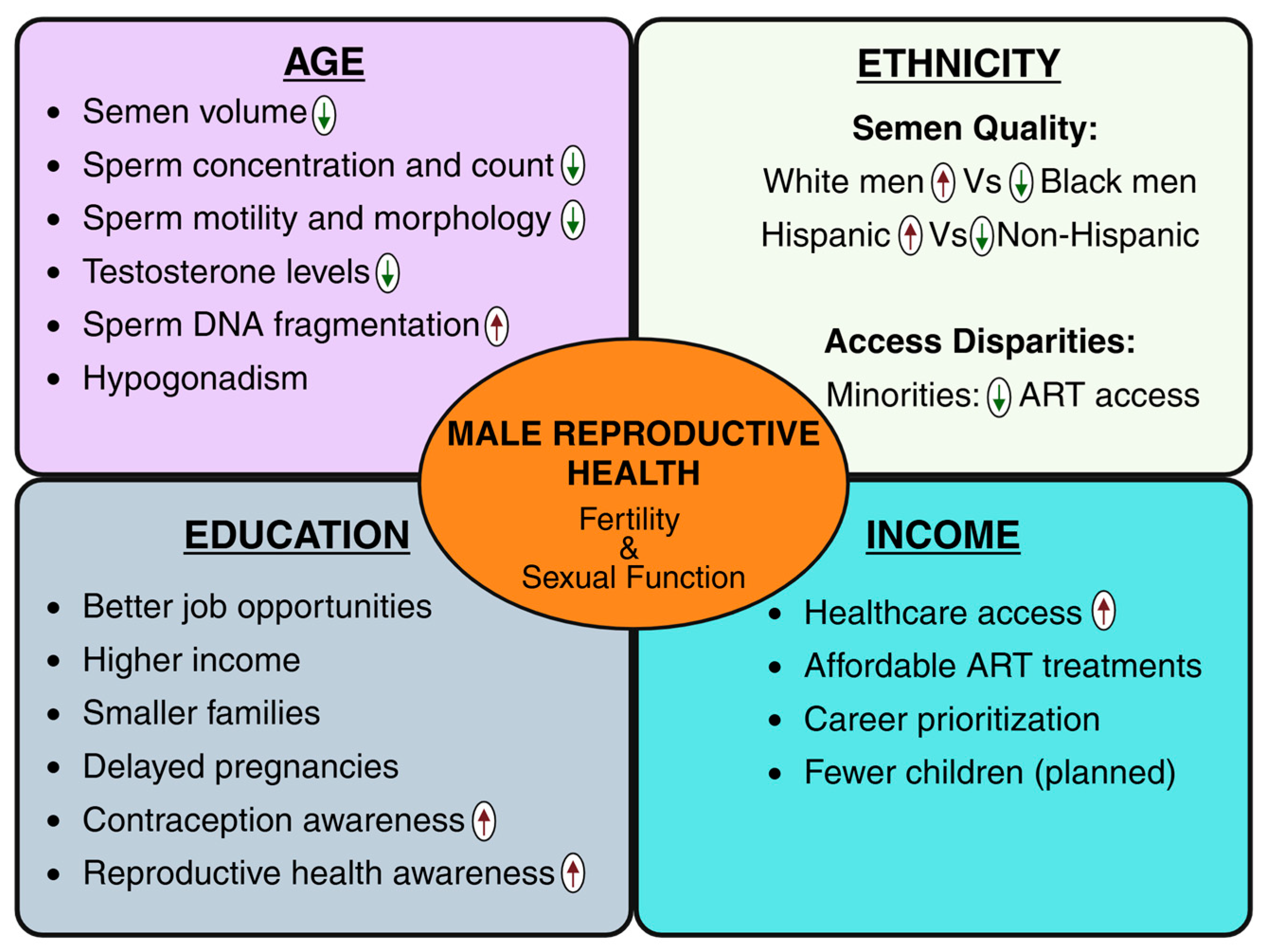

2. Key Socioeconomic Demographic Factors and Male Reproductive Health

3. SES and Male Reproductive Health: Perspectives from Developed and Developing Countries

4. SES Determining Men’s Access to Infertility Treatment and ART

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SES | socioeconomic status |

| ART | assisted reproductive technology |

| DHT | dihydrotestosterone |

| IUI | intrauterine insemination |

| IVF | in vitro fertilization |

| LMICs | low- and middle-income countries |

References

- Levine, H.; Jørgensen, N.; Martino-Andrade, A.; Mendiola, J.; Weksler-Derri, D.; Mindlis, I.; Pinotti, R.; Swan, S.H. Temporal trends in sperm count: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2017, 23, 646–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inhorn, M.C.; Patrizio, P. Infertility around the globe: New thinking on gender, reproductive technologies and global movements in the 21st century. Hum. Reprod. Update 2015, 21, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainberg, J.; Kashanian, J.A. Recent advances in understanding and managing male infertility. F1000Research 2019, 8, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Baskaran, S.; Parekh, N.; Cho, C.L.; Henkel, R.; Vij, S.; Arafa, M.; Panner Selvam, M.K.; Shah, R. Male infertility. Lancet 2021, 397, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avvisati, F. The measure of socio-economic status in PISA: A review and some suggested improvements. Large Scale Assess. Educ. 2020, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordkap, L.; Priskorn, L.; Bräuner, E.V.; Marie Hansen, Å.; Kirstine Bang, A.; Holmboe, S.A.; Winge, S.B.; Egeberg Palme, D.L.; Mørup, N.; Erik Skakkebaek, N.; et al. Impact of psychological stress measured in three different scales on testis function: A cross-sectional study of 1362 young men. Andrology 2020, 8, 1674–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Nangia, A.K.; Dupree, J.M.; Smith, J.F. Limitations and barriers in access to care for male factor infertility. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 105, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurewicz, J.; Hanke, W.; Radwan, M.; Bonde, J.P. Environmental factors and semen quality. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2009, 22, 305–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molarius, A.; Berglund, K.; Eriksson, C.; Lambe, M.; Nordström, E.; Eriksson, H.G.; Feldman, I. Socioeconomic conditions, lifestyle factors, and self-rated health among men and women in Sweden. Eur. J. Public Health 2006, 17, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytaç, I.A.; Araujo, A.B.; Johannes, C.B.; Kleinman, K.P.; McKinlay, J.B. Socioeconomic factors and incidence of erectile dysfunction: Findings of the longitudinal Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpey, N.C.; Gaglioti, A.H.; Rosenbaum, M.E. How Socioeconomic Status Affects Patient Perceptions of Health Care: A Qualitative Study. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2017, 8, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, C.; Konstantinidis, T. A Review of the Relationship between Socioeconomic Status Change and Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, S.; Balasubramaniam, K.; Jarbøl, D.E.; Søndergaard, J.; Haastrup, P.F. Socioeconomic status and barriers for contacting the general practitioner when bothered by erectile dysfunction: A population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudsari, R.L.; Sharifi, F.; Goudarzi, F. Barriers to the participation of men in reproductive health care: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskenazi, B.; Wyrobek, A.J.; Sloter, E.; Kidd, S.A.; Moore, L.; Young, S.; Moore, D. The association of age and semen quality in healthy men. Hum. Reprod. 2003, 18, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, L. AB19. Testosterone replacement therapy: How safe is it? Transl. Androl. Urol. 2014, 3 (Suppl. 1), AB19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Davies, N.M.; Howe, L.D.; Hughes, A. Testosterone and socioeconomic position: Mendelian randomization in 306,248 men and women in UK Biobank. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf8257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, A.; Kumari, M. Testosterone, risk, and socioeconomic position in British men: Exploring causal directionality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 220, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanbanadaki, H.; Kim, B.; Fendereski, K.; Horns, J.J.; Ramsay, J.M.; Jimbo, M.; Gross, K.X.; Pastuszak, A.W.; Hotaling, J.M. Racial/Ethnic differences in male reproductive health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of semen parameters and hormonal profiles in the United States. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaco, S.; Modi, D. Genetics of the human Y chromosome and its association with male infertility. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, M.J.; Huffman, P.J.; Haney, N.M.; Kohn, T.P. Y-Chromosome Microdeletions: A Review of Prevalence, Screening, and Clinical Considerations. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2021, 14, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellke, N.; Badreddine, J.; Rhodes, S.; Thirumavalavan, N.; Abou Ghayda, R. The Racial and Socioeconomic Characteristics of Men Using Mail-in Semen Testing Kits in the United States. Urology 2023, 180, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.B.; Jarvi, K.A.; Lajkosz, K.; Smith, J.F.; Lo, K.C.; Grober, E.D.; Lau, S.; Bieniek, J.M.; Brannigan, R.E.; Chow, V.D.W.; et al. One size does not fit all: Variations by ethnicity in demographic characteristics of men seeking fertility treatment across North America. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamborini, C.R.; Kim, C.; Sakamoto, A. Education and Lifetime Earnings in the United States. Demography 2015, 52, 1383–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkwananzi, S. Gender differentials of contraceptive knowledge and use among youth—Evidence from demographic and health survey data in selected African countries. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2022, 3, 880056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheynkin, Y.; Jung, M.; Yoo, P.; Schulsinger, D.; Komaroff, E. Increase in scrotal temperature in laptop computer users. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilacqua, A.; Izzo, G.; Emerenziani, G.P.; Baldari, C.; Aversa, A. Lifestyle and fertility: The influence of stress and quality of life on male fertility. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyanda, A.E.; Dinkins, B.J.; Osayomi, T.; Adeusi, T.J.; Lu, Y.; Oppong, J.R. Fertility knowledge, contraceptive use and unintentional pregnancy in 29 African countries: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gago, L.C.; Greenberg, D.R.; Kumar, S.; Panken, E.J.; Horns, J.J.; Ramsay, J.; Brannigan, R.E.; Hotaling, J.M.; Halpern, J.A. Environmental PM2.5 Exposure and Socioeconomic Deprivation Are Independent Risk Factors for Impaired Semen Parameters. Urology, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodprasert, W.; Toppari, J.; Virtanen, H.E. Environmental toxicants and male fertility. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 86, 102298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapke, E.T.; Magalhaes, D.P.; Dalvie, M.A.; Mandrioli, D.; Perry, M.J. Environmental and occupational pesticide exposure and human sperm parameters: A Navigation Guide review. Toxicology 2022, 465, 153017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, P.; Banerjee, R. Environmental toxins: Alarming impacts of pesticides on male fertility. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2014, 33, 1017–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ombelet, W. Global access to infertility care in developing countries: A case of human rights, equity and social justice. Facts Views Vis. Obgyn 2011, 3, 257–266. [Google Scholar]

- Hopcroft, R.L. Number of Childbearing Partners, Status, and the Fertility of Men and Women in the U.S. Front. Sociol. 2018, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, D.; Edlund, L. Trivers-Willard at birth and one year: Evidence from US natality data 1983–2001. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2007, 274, 2491–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enstad, S.; Rankin, K.; Desisto, C.; Collins, J.W., Jr. Father’s Lifetime Socioeconomic Status, Small for Gestational Age Infants, and Infant Mortality: A Population-Based Study. Ethn. Dis. 2019, 29, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horns, J.J.; Fendereski, K.; Ramsay, J.M.; Halpern, J.; Iko, I.N.; Ferlic, E.; Emery, B.R.; Aston, K.; Hotaling, J. The impact of socioeconomic status on bulk semen parameters, fertility treatment, and fertility outcomes in a cohort of subfertile men. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 120, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Roode, T.; Sharples, K.; Dickson, N.; Paul, C. Life-Course Relationship between Socioeconomic Circumstances and Timing of First Birth in a Birth Cohort. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persily, J.; Stair, S.; Najari, B.B. Access to infertility services: Characterizing potentially infertile men in the United States with the use of the National Survey for Family Growth. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 114, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrie, R.; Ghosh, S.; Narvekar, N.; Vigneswaran, K.; Wang, Y.; Savvas, M. Socioeconomic status and fertility treatment outcomes in high-income countries: A review of the current literature. Hum. Fertil. 2023, 26, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manvelyan, E.; Abittan, B.; Shan, W.; Shahani, D.; Kwait, B.; Rausch, M.; Blitz, M.J. Socioeconomic disparities in fertility treatments and associated likelihood of livebirth following in vitro fertilization. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 308, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- eClinicalMedicine. The current status of IVF: Are we putting the needs of the individual first? eClinicalMedicine 2023, 65, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Präg, P.; Mills, M.C. Assisted Reproductive Technology in Europe: Usage and Regulation in the Context of Cross-Border Reproductive Care. In Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, Causes, and Consequences; Kreyenfeld, M., Konietzka, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 289–309. [Google Scholar]

- Dupree, J.M. Insurance coverage for male infertility care in the United States. Asian J. Androl. 2016, 18, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.A.; Menke, M.N.; Haefner, J.K.; Moniz, M.H.; Perumalswami, C.R. Geographic access to assisted reproductive technology health care in the United States: A population-based cross-sectional study. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 107, 1023–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Disparities in access to effective treatment for infertility in the United States: An Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 116, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brautsch, L.A.S.; Voss, I.; Schmidt, L.; Vassard, D. Social disparities in the use of ART treatment: A national register-based cross-sectional study among women in Denmark. Hum. Reprod. 2023, 38, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhard, R.S.; Ritenour, C.W.M.; Goodman, M.; Vashi, D.; Hsiao, W. Awareness of and attitudes towards infertility and its treatment: A cross-sectional survey of men in a United States primary care population. Asian J. Androl. 2014, 16, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpahan, C.; Ibrahim, R.; William, W.; Kandar, P.S.; Darmadi, D.; Khaerana, A.S.A.; Supardi, S. “Am I Masculine?” A metasynthesis of qualitative studies on traditional masculinity on infertility. F1000Research 2023, 12, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, F.; Talebi, M.; Jandaghian-Bidgoli, M.; Shaterian, N.; Dehghankar, L. Surviving and thriving: Male infertility through the lens of meta-ethnography. Discov. Soc. Sci. Health 2025, 5, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badreddine, J.; Sellke, N.; Rhodes, S.; Thirumavalavan, N.; Abou Ghayda, R. The association of socioeconomic status with semen parameters in a cohort of men in the United States. Andrology 2024, 12, 1722–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braverman, A.M.; Davoudian, T.; Levin, I.K.; Bocage, A.; Wodoslawsky, S. Depression, anxiety, quality of life, and infertility: A global lens on the last decade of research. Fertil. Steril. 2024, 121, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, Z.; Fakari, F.R.; Hakimzadeh, A.; Hajian, S.; Fakari, F.R.; Nasiri, M. Prevalence of depression in infertile men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Panner Selvam, M.K.; Baskaran, S.; Cho, C.L. Sperm DNA damage and its impact on male reproductive health: A critical review for clinicians, reproductive professionals and researchers. Expert. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2019, 19, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadson, A.K.; Sauerbrun-Cutler, M.T.; Eaton, J.L. Racial Disparities in Fertility Care: A Narrative Review of Challenges in the Utilization of Fertility Preservation and ART in Minority Populations. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirubarajan, A.; Patel, P.; Leung, S.; Prethipan, T.; Sierra, S. Barriers to fertility care for racial/ethnic minority groups: A qualitative systematic review. F&S Rev. 2021, 2, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morshed-Behbahani, B.; Lamyian, M.; Joulaei, H.; Rashidi, B.H.; Montazeri, A. Infertility policy analysis: A comparative study of selected lower middle- middle- and high-income countries. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, A.; Taylor, S.; Glass, B. Inequity of Access: Scoping the Barriers to Assisted Reproductive Technologies. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.F.; Ma, G.X.; Miranda, J.; Eng, E.; Castille, D.; Brockie, T.; Jones, P.; Airhihenbuwa, C.O.; Farhat, T.; Zhu, L.; et al. Structural Interventions to Reduce and Eliminate Health Disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, S72–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, A.; Betancourt, T.; Kergoat, Y.; Servilli, C.; Say, L.; Kobeissi, L. A systematic review of sexual and reproductive health interventions for young people in humanitarian and lower-and-middle-income country settings. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kapoor, R.; Panner Selvam, M.K.; Sikka, S.C. Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Male Reproductive Health: A Mini Review. Reprod. Med. 2025, 6, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6040044

Kapoor R, Panner Selvam MK, Sikka SC. Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Male Reproductive Health: A Mini Review. Reproductive Medicine. 2025; 6(4):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6040044

Chicago/Turabian StyleKapoor, Rishik, Manesh Kumar Panner Selvam, and Suresh C. Sikka. 2025. "Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Male Reproductive Health: A Mini Review" Reproductive Medicine 6, no. 4: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6040044

APA StyleKapoor, R., Panner Selvam, M. K., & Sikka, S. C. (2025). Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Male Reproductive Health: A Mini Review. Reproductive Medicine, 6(4), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6040044