Abstract

Background: Preeclampsia (PE) and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) are complex pregnancy disorders characterized by hypertension, proteinuria, increased blood glucose levels, and metabolic dysfunction. Methods: We investigated lymphocyte proliferation, immune function, key antioxidants, and metabolic and mitochondrial enzyme activities in women with PE and PE with GDM compared to normotensive pregnant (NP) controls. Lymphocyte proliferation was assessed following phytohemagglutinin (PHA) stimulation at varying concentrations (0.5, 2.5, and 5 µg/mL). Activities of key antioxidant enzymes, metabolic enzymes, and mitochondrial enzymes were measured. Other stress markers, including nitric oxide (NO) production and lipid peroxidation (TBARS), along with acetylcholine esterase (AChE) activity, and proinflammatory cytokine assays (IL-6 and TNF-α) were also evaluated from the PHA-induced lymphocytes. Results: Lymphocyte proliferation in response to PHA was significantly increased in PE and PE with GDM groups compared to NP, although low-dose PHA (0.5 and 2.5 µg/mL) moderately enhanced proliferation in NP. IL-6 and TNF-α levels were notably elevated in both disease groups. Antioxidant activities of SOD, GST, GPx and AChE, Citrate synthase, Cytochrome c oxidase, and NO production were significantly reduced in PE and PE with GDM, while hexokinase activity involved in glycolysis was elevated in both groups. Further, TBARS levels were elevated in the disease groups, particularly in PE with GDM. Conclusions: The findings arise from a clinical cross-sectional study and highlight significant immune alterations, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial impairment in PE and PE with GDM. The observed elevation in proinflammatory cytokines further underscore the role of immune activation in the pathogenesis of these complications, emphasizing the integrated immunometabolic shifts identified in this study, as potential molecular indicators for early intervention.

1. Introduction

Preeclampsia (PE) is a complex and multisystem disorder that arises after the 20th week of pregnancy and affects approximately 5–8% of pregnancies globally, making it the second leading cause of direct maternal and fetal mortality [1]. Clinically, it is characterized by new-onset hypertension (blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg) and proteinuria (urinary protein ≥300 mg/24 h), and in severe cases, it can lead to multi-organ dysfunction involving the liver, kidneys, hematologic system, and central nervous system [2]. Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is another common pregnancy complication which is defined as glucose intolerance with onset or first recognized during pregnancy. The prevalence of GDM ranges from 15 to 25% worldwide [3], and it is rising due to increasing obesity rates, sedentary behaviour, and poor dietary practices during pregnancy [4]. When GDM and PE coexist, they significantly elevate the risk of adverse outcomes, including fetal growth restriction (FGR), preterm birth (PTB), and long-term metabolic disorders in the offspring [5] mainly due to weight gain or obesity [5,6]. The pathophysiology of PE in the context of GDM may differ in important ways from PE alone. Aziz et al. (2024) demonstrated that dyslipidemia and glucose intolerance during late pregnancy are strongly associated with hypertensive and proteinuric features of PE in GDM women, implicating metabolic–vascular crosstalk in their etiology [7]. In PE, abnormal placentation and shallow trophoblast invasion drive a systemic inflammatory response [8,9], with increased Th1 cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-γ, and reduced regulatory T cells (Tregs), which disrupt maternal–fetal tolerance [10]. Similarly, GDM, associated with elevated proinflammatory cytokines and insulin resistance, linking metabolic dysregulation to vascular injury [11]. These immune alterations form a shared pathophysiological basis linking PE and GDM. Assessment of lymphocyte proliferation in response to mitogenic stimulation, such as phytohemagglutinin (PHA), can offer insight into the functional status of maternal immune cells during pregnancy. Altered lymphocyte responses may reflect impaired immunoregulation; this may serve as one of the characteristic factors of PE and GDM.

An imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and antioxidant defense leads to oxidative stress, which plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of both preeclampsia (PE) and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). During normal pregnancy, ROS act as signaling molecules for placental development. However, in PE, defective spiral artery remodeling and placental hypoxia lead to maternal vascular malperfusion (ischemia) injury, excessive ROS generation, and damage to placental tissue [12]. In GDM, hyperglycemia enhances ROS production through glucose oxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction. Antioxidant enzymes, including catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione S-transferase (GST), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), are crucial for neutralizing ROS. Reduced activities of some of these enzymes in PE and GDM indicate compromised redox homeostasis [13].

Mitochondria, essential for ATP generation and redox balance, are increasingly implicated in pregnancy-related complications. In PE, several studies have documented impaired mitochondrial respiration, reduced ATP production, and elevated oxidative stress in placental tissues [14]. Mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to excessive ROS production and cellular apoptosis, thereby contributing to systemic inflammation and endothelial injury. Key metabolic enzymes such as hexokinase (HK), citrate synthase (CS), and pyruvate kinase (PK) play central roles in glycolysis and mitochondrial function. Dysregulation of these enzymes may serve as indicators of altered energy metabolism and bioenergetic stress in PE and GDM. Their assessment may help reveal subtle shifts in metabolic pathways that precede clinical symptoms.

Emerging evidence also implicates neurovascular pathways in pregnancy complications. Acetylcholine esterase (AChE), an enzyme of the cholinergic system, regulates vasodilation, inflammation, and fetal brain development. Altered AChE activity may reflect impaired autonomic and vascular function in PE and GDM [15]. Nitric oxide (NO), produced through the activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), acts as a key vasodilator and regulator of platelet aggregation and immune function. In PE and GDM, NO bioavailability may be reduced due to oxidative stress, inflammation, and eNOS uncoupling, contributing to vascular resistance and hypertension [16].

Recent studies highlight that PE coexisting with GDM represents a distinct clinical phenotype rather than a simple coexistence of two disorders. The combined condition exhibits greater endothelial dysfunction, exaggerated placental ischemia, amplified systemic inflammation, and more pronounced metabolic dysregulation, compared with either condition alone [17]. Additionally, immune tolerance breakdown appears more severe in PE + GDM, with reports of altered T-cell subsets, exaggerated cytokine responses, and impaired antioxidant defenses [18].

Despite these advancements, a significant mechanistic gap persists regarding how immune activation, oxidative stress, and metabolic enzyme alterations converge within circulating lymphocytes during PE and PE + GDM. Most existing studies examine these pathways independently, limiting the understanding of their integrated contribution to disease severity.

Despite increasing evidence linking inflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and environmental exposures to adverse pregnancy outcomes, most studies have examined these pathways separately. A comprehensive understanding of how these processes converge in PE and GDM is lacking. Given these observations, we hypothesized that women with PE and PE + GDM would display distinct immunometabolic alterations in circulating PBMCs, characterized by exaggerated PHA-induced lymphocyte activation, shifts in mitochondrial and glycolytic enzyme activity, and heightened oxidative–nitrosative stress.

This study aims to simultaneously evaluate immune function (lymphocyte proliferation, cytokines TNF-α, IL-6), antioxidant status (SOD, CAT, GPx, GST), metabolic enzyme activities (HK, CS, and PYK), and neurovascular stress markers (TBARS, nitric oxide, AChE) in pregnant women diagnosed with PE and GDM compared to normotensive pregnant (NP) controls. By investigating these interconnected pathways, the study seeks to elucidate shared and distinct biochemical signatures of PE and GDM and clarify how these findings address the identified mechanistic gap and identify early, non-invasive molecular indicators for risk assessment and targeted intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

A cross-sectional investigation was carried out involving PE, GDM, and NP. A total of fifty Indian pregnant women, who voluntarily participated in the study, were divided into three groups: NP (N = 15), PE (N = 20), and PE with GDM (N = 15). Informed consent, biochemical and anthropometric characteristics, were collected from each participant and documented. Sociodemographic variables were collected from the questionnaire responses, including age, weight, general health profile, family history, lifestyle factors such as alcohol use and smoking, and gynecological profile. The research received approval from the institutional ethics committee for human studies at SRM Medical College Hospital and Research Centre (SRMCHRC) (Ethical clearance: 8469/IEC/2022).

Inclusion criteria: singleton pregnancy, age 21–41 years, diagnosis of PE or GDM according to ACOG and DIPSI guidelines, and gestational age ≥20 weeks. Exclusion criteria: chronic hypertension, pre-existing diabetes mellitus, autoimmune disease, known infections, renal disorders, or use of anti-inflammatory, antihypertensive, or corticosteroid medications.

PE was classified based on ACOG criteria. Participants included had non-severe PE, defined by systolic BP 140–159 mmHg and/or diastolic BP 90–109 mmHg with proteinuria (≥300 mg/24 h or ≥1+ dipstick). No cases of severe PE were included.

2.2. Demographic Profile

Demographic and clinical information collected from all participants, including their age, gestational BMI, blood pressure (systolic and diastolic), and gestational age are detailed in our previous publication [4]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2) using measured anthropometric data.

2.3. Sample Collection

PE and GDM were defined following the guidelines recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG and the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group India (DIPSI). Pregnant women who had any other complications were excluded. Five mL of blood sample was collected from 24 to 34 weeks of pregnant women in clot activator and EDTA-coated vacutainers between 8:00 and 9:00 a.m. at SRMCHRC at the outpatient (OP). Following that, serum and plasma samples were separated and refrigerated at −80 °C for future examination.

2.3.1. Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG) and Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

FPG values, obtained after a minimum of 8 h of fasting, were retrieved from participants’ medical records. Each participant also underwent a 1 h and 2 h OGTT (PP1 and PP2) following administration of a 75 g glucose load.

2.3.2. Albumin Analysis

Urinary albumin levels were determined using the heat coagulation method with 1% acetic acid. In addition, routine urine analysis was performed using the dipstick technique, where albumin concentration was semi-quantitatively graded as nil, trace, single plus (+), or double plus (++).

2.4. Isolation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) and Lymphocytes

Density gradient centrifugation was used to separate PBMCs from plasma samples. Erythrocytes were removed by layering the plasma cell suspension onto Histopaque 1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and centrifuging it at 2500 rpm for 30 min. Lymphocytes were prepared as described in previous research [19]. Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) [PHA-M Himedia TC209] induced lymphocyte culture was used for further assays [20]. All functional assays including cytokine quantification, metabolic enzyme activity, antioxidant enzyme assays, NO production, TBARS, and AChE activity—were performed on PHA-stimulated PBMC-derived lymphocytes unless otherwise specified.

2.5. PHA-Induced Proliferation of Lymphocytes

PBMCs (2 × 105 cells/mL) were cultured with 0.5, 2.5, and 5 μg/mL of mitogen PHA in 96-well, flat-bottom tissue culture plates at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After 72 h, lymphocyte proliferation induced by PHA was assessed in triplicate using the MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assay. In brief, the cells were incubated with MTT reagent for 3 h, after which the resulting formazan crystals were completely dissolved using isopropanol containing 37% HCl [21]. The optical density was determined at 492 nm and 620 nm using an ELISA reader (Robonik readwell TOUCH, Mumbai, India). The same assay conditions were used across all three groups, and proliferation indices were validated for inter-assay consistency.

2.6. PHA-Induced Cytokine Production

PBMCs (2 × 105 cells/well) were cultured in 24-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates with 5 μg/mL of PHA and without PHA, supplemented in RPMI medium, and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h [22]. After 24 h of cell lysis, the supernatant and cell lysate were separated and stored at −80 °C. Cytokine assay (TNF-α and IL-6) was performed using GENLISATM Human ELISA kits (Krishgen Biosystems, Mumbai, India) from the supernatant of PHA-induced lymphocytes.

2.7. Metabolic Enzyme Activity

After 40 cycles of freezing and thawing, the supernatant was collected from the lymphocyte-cell lysate. The PHA-induced lymphocyte was lysed in a freshly prepared RIPA buffer containing 0.005 M Tris, 0.001 M EDTA, 100 μg/mL PMSF, and 1 mM activated sodium orthovanadate (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Then, the supernatant was used to perform protein estimation using Lowry’s method, followed by enzyme assays. Metabolic enzyme assays were conducted on stimulated lymphocyte lysates to evaluate immune cell-specific metabolic responses, which are relevant for immunometabolic dysfunction in PE and GDM.

2.7.1. Hexokinase Activity

Hexokinase (HK) activity was measured using an incubation medium composed of 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), 13.3 mM MgCl2, 6.8 mM NAD, 16.5 mM ATP, 0.67 mM glucose, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (0.03 IU) [23]. Absorbance was measured at 340 nm using a spectrophotometer, and the enzyme activity was expressed in terms of activity/min/mg protein.

2.7.2. Pyruvate Kinase Activity

Pyruvate kinase (PYK) was determined in a basic medium containing 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4), 100 mM MgCl2, 500 mM KCl, 2 mM NADH, 10 mM ADP, 20 mM phospho-enol pyruvate, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) enzyme (20 units/mL) [24]. Then the absorbance was measured at 340 nm at an interval of 1 min up to 5 min and enzyme activity was expressed in terms of activity/min/mg protein.

2.7.3. Citrate Synthase Activity

The reaction mixture used to assay citrate synthase (CS) activity consisted of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.1), 0.1 mM acetyl coenzyme A (CoA), 0.2 mM 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), and 0.25 mM oxaloacetate. Citrate synthase (CS) activity was assessed by monitoring the formation of CoA-SH [25]. Enzyme activity was analyzed at 405 nm, and its activity was expressed in terms of activity/min/mg protein.

2.7.4. Cytochrome C Oxidase Assay

The activity of cytochrome c oxidase in stimulated lymphocytes was quantified by the decrease in the rate of oxidation of ferro cytochrome c to ferricytochrome c by cytochrome c oxidase by measuring the absorbance at 550 nm [24]. The result was expressed in terms of cytochrome c oxidase activity/min/mg protein (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.8. Antioxidant Enzyme Assays

2.8.1. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity

The SOD activity was measured in terms of percentage inhibition of epinephrine auto-oxidation. The cell lysate was homogenized in a 5:3 ice-cold ethanol-chloroform mixture, centrifuged, and the resulting supernatant was collected for the assay. The sample was diluted in 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 10) and mixed with equal volumes of 0.6 mM EDTA and 1.3 mM epinephrine prepared in the same buffer [25]. Absorbance was then recorded at 480 nm using a spectrophotometer at 0, 30, and 60 s intervals. The results were expressed as units per minute per milligram of protein.

2.8.2. Catalase (CAT) Activity

Total catalase (CAT) activity was determined using a hydrogen peroxide-based assay, in which hydrogen peroxide reacts with ammonium molybdate to form a measurable complex. The sample was suspended in 60 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 65 mM hydrogen peroxide and incubated for 4 min. The reaction was then terminated with 32.4 mM ammonium molybdate, and the absorbance was recorded at 405 nm. CAT activity was expressed as units per minute per milligram of protein [25].

2.8.3. Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) Activity

Glutathione peroxidase (GPx, isoform GPx1) activity was determined using Ellman’s reagent. The sample was diluted in 0.4 M phosphate buffer (pH 7) containing 10 mM sodium azide, 4 mM reduced glutathione, and 2.5 mM hydrogen peroxide, and incubated for 0, 1, 1.5, and 3 min. The reaction was terminated with 10% trichloroacetic acid and centrifuged. To the resulting supernatant, 0.3 M disodium hydrogen phosphate and 1 mM 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) in 1% sodium citrate were added [25]. Absorbance was immediately measured at 412 nm, and GPx activity was expressed as units per minute per milligram of protein.

2.8.4. Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST) Activity

The GST activity was estimated for the samples by using 1-Chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB). Glutathione (GSH) was combined with a catalyst, GST, and CDNB was used as the substrate [25]. The absorbance was measured at 340 nm for 0, 30, and 60 s.

2.9. Nitric Oxide Production

Total nitric oxide (NO) production was assessed in 72 h culture supernatants using the Griess reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The samples were incubated with equal volumes of 0.1% N-1-naphthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride in water and 1% sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid for 10 min, after which absorbance was measured at 520 nm [23]. A standard curve was generated using serial dilutions of 0.1 M sodium nitrite in water, and results were expressed as μg sodium nitrite equivalents per milliliter.

2.10. Lipid Peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation was assessed by measuring the formation of adducts with thiobarbituric acid (TBA). The sample was first treated with ice-cold 10% trichloroacetic acid to precipitate proteins, incubated for 15 min, and centrifuged at 2200× g for 15 min. The resulting supernatant was then mixed with an equal volume of 0.67% TBA and incubated in a boiling water bath for 10 min. After cooling, absorbance was measured at 532 nm [23]. A standard curve was prepared using serial dilutions of 1,1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane or malondialdehyde (MDA) in distilled water, and the results were expressed as MDA equivalents per minute per milligram of protein.

2.11. Cholinesterase Activity

Cholinesterase activity was determined using Ellman’s reagents, with DTNB as the chromogenic agent and acetylthiocholine iodide as the substrate. Samples were supplemented with 0.4 mM DTNB and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Following this, 1 mM acetylthiocholine iodide was added and mixed thoroughly, and absorbance was recorded at 436 nm at 60 s intervals over 5 min. Enzyme activity was expressed as units per minute per milligram of protein [26].

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Group differences were evaluated using ANOVA in GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 (244). Parameters showing significance (p < 0.05) in ANOVA were further subjected to Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Data are presented as mean ± SD, and a two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Pearson correlation analysis was performed between anthropometrical variables and biochemical parameters of PE and PE with GDM. All statistical procedures followed assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance.

3. Results

3.1. Biochemical Parameters of Pregnant Women

Glucose parameters such as FBG, PP1, PP2, and HbA1c showed a significant increase in PE with GDM compared to NP. The values of these glucose parameters were tabulated in the table (Table 1).

Table 1.

Biochemical variables of Pregnant women.

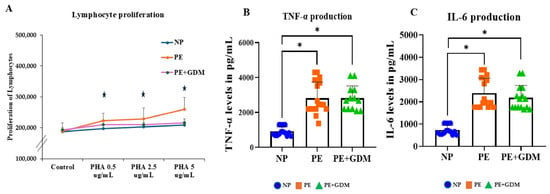

3.2. Lymphocyte Proliferative Activity

Confounding factors such as age above 30 years, was used to analyze the lymphocyte proliferation, which shows a significant (p < 0.05) change in proliferation in both PE and PE with GDM disease conditions. Lymphocyte proliferation in response to PHA stimulation was significantly (p < 0.05) increased in the PE and PE with GDM groups compared to NP; confirming heightened mitogenic responsiveness in disease groups (Figure 1A). A significant increase in lymphocyte proliferative response was observed at 0.5, 2.5, and 5 µg/mL of PHA concentrations, compared to the NP group, indicating dose-dependent mitogenic activation. The assay displayed consistent dose-dependent proliferation across groups, with no variability across replicates.

Figure 1.

(A). PHA-induced proliferation of lymphocytes from NP, PE, and PE with GDM women. Lymphocyte (2 × 105 cells/mL) were incubated with 0, 0.5, 1.25, or 5 μg/mL of PHA for 72h, and proliferation was assessed using the MTT assay. PHA-induced proliferation of lymphocytes increased in PE women compared to NP. (B). TNF-α and (C). IL-6, the proinflammatory cytokine production, were increased in 5 μg /mL of PHA-induced lymphocytes among PE and PE with GDM women compared to NP. * represents (p < 0.05) significance compared to NP.

3.3. Response of Proinflammatory Cytokine Production

Proinflammatory cytokine markers such as TNF-α and IL-6 contributed to the development of disease progression by endothelial dysfunction and organ damage. The PE group showed significantly (p < 0.05) elevated TNF-α levels compared to the NP, indicating severe systemic inflammation. The PE with GDM also exhibited significantly (p < 0.05) higher TNF-α levels, suggesting a potential synergistic inflammatory effect due to the coexistence of gestational diabetes (Figure 1B). Similarly, significantly (p < 0.05) increased IL-6 production was observed in PE and PE with GDM (Figure 1C). The PE + GDM group exhibited the highest cytokine levels, consistent with a compounded proinflammatory state.

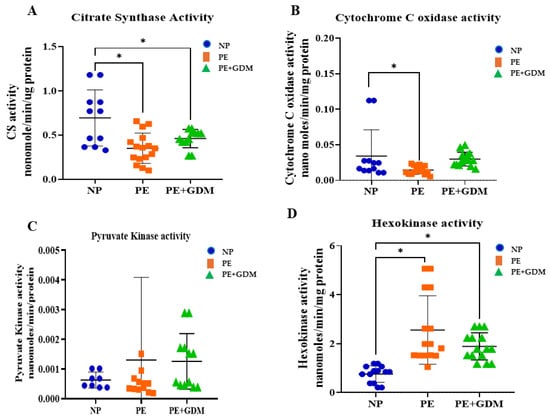

3.4. Effects of Rate-Limiting Metabolic Enzyme Activity

Key metabolic enzymes, such as CS, exhibited significantly (p < 0.05) diminished activities (Figure 2A) in PE and PE with GDM groups compared to NP, suggesting mitochondrial dysfunction—a potential impairment in mitochondrial oxidative capacity. PYK activity, however, did not demonstrate significant alterations between the groups (Figure 2B). The mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase activity (Figure 2C) was significantly (p < 0.05) suppressed in the PE group, indicative of disrupted electron transport chain function, whereas HK activity elevated and impaired glycolytic flux (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Metabolic enzyme activities, including (A). Citrate synthase (CS), (B). Cytochrome C oxidase, mitochondrial enzyme activities are decreased, and (C). Pyruvate kinase (PYK); (D). Hexokinase, a glycolytic enzyme activity, increased in PE and PE with GDM compared to NP. * represents (p < 0.05) significant compared to NP.

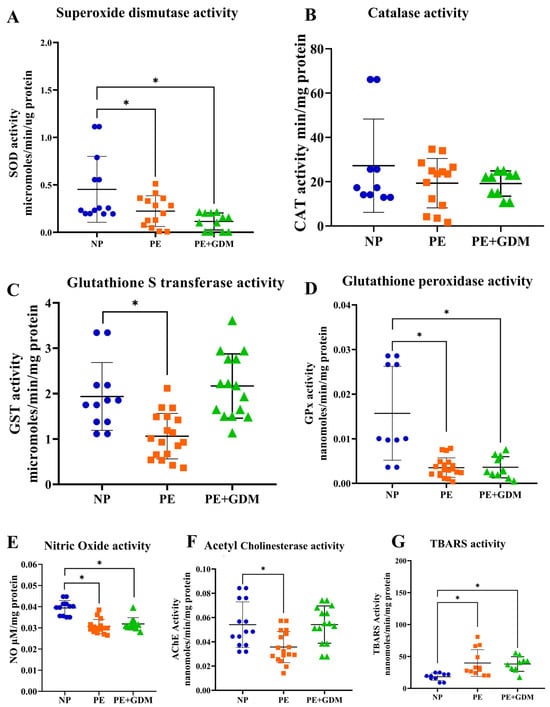

3.5. Effects of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

Lymphocyte antioxidant enzyme activities showed marked reductions in disease groups. SOD activity was significantly (p < 0.05) decreased in both PE and PE with GDM groups compared to NP (Figure 3A), indicating compromised superoxide radical scavenging capacity. Similarly, GST and GPx activities were significantly (p < 0.05) lower in the PE group (Figure 3C,D) compared to NP. Notably, GPx activity was also significantly (p < 0.05) reduced in PE with GDM compared to NP, reflecting impaired enzymatic detoxification of hydrogen peroxide and lipid hydroperoxides. Whereas catalase activity does not show significant changes in PE and PE with GDM groups compared to NP.

Figure 3.

Antioxidant enzyme activities (A). SOD activities, (B). CAT, (C). GST, and (D). GPx decreased PE and PE with GDM compared to NP, (E). NO production decreased in PE with GDM compared to NP, (F). Choline esterase activities are decreased in PE and PE with GDM compared to NP, (G). Lipid peroxidation increased in PE and PE with GDM compared to NP. * represents (p < 0.05) significant compared to NP.  NP

NP  PE

PE  PE + GDM.

PE + GDM.

NP

NP  PE

PE  PE + GDM.

PE + GDM.

3.6. Effects of Reactive Nitrogen Species, Lipid Peroxidation, and Choline Esterase Activities

NO production significantly (p < 0.05) decreased in the PE with the GDM group compared to NP, potentially contributing to oxidative and nitrosative stress (Figure 3E). Decreased NO in PHA-stimulated lymphocytes may reflect impaired immunomodulatory NO signaling under oxidative–inflammatory stress. AChE activity was significantly (p < 0.05) reduced in PE compared to NP, which may reflect altered cholinergic signaling or oxidative impairment of membrane-bound enzymes (Figure 3F). Reduced AChE activity may be indicative of impaired neurovascular regulation in disease states. Concurrently, lipid peroxidation levels, measured by TBARS, were significantly (p < 0.05) elevated in both the PE and PE with GDM groups (Figure 3G) compared to NP. This elevation supports the observation of reduced antioxidant defense activity in the same group.

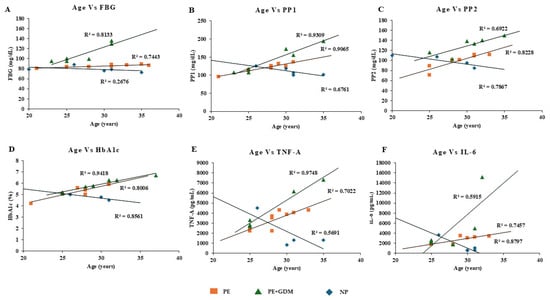

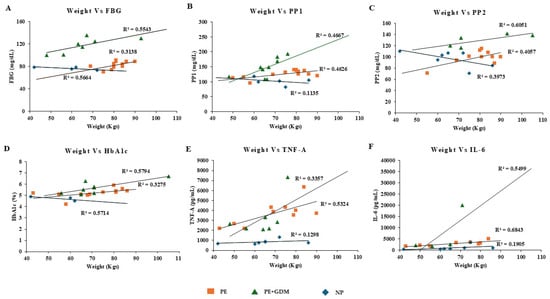

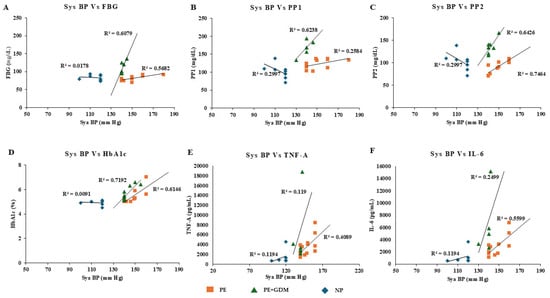

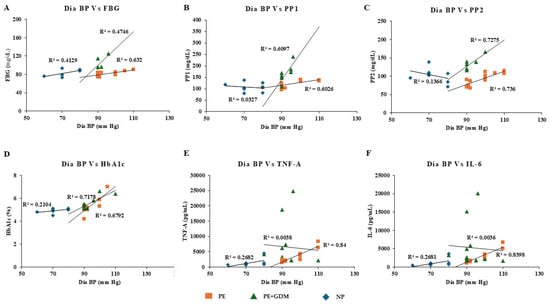

3.7. Correlations of Anthropometric Variables with Biochemical Parameters

Correlation analysis was observed between maternal age, weight, blood pressure, gestational age, and biochemical markers (glycemic profile and proinflammatory markers). After adjusting the confounding variables, significant positive correlation was observed between maternal age and glycemic profile (>R2 = 0.7 to 0.94), including FBS, PP1 and PP2, and HbA1c among PE and PE with GDM (Figure 4A–D). Similarly, a positive correlation was also observed between the maternal age of PE with GDM and proinflammatory markers such as TNF-α and IL-6 (>R2 = 0.59 to 0.97) (Figure 4E,F). Whereas maternal weight showed significant correlation with proinflammatory markers such as TNF-α (Figure 5E) for PE with GDM (R2 = 0.5) and IL-6 (Figure 5F) for PE and PE with GDM (>R2 = 0.54 to 0.68). Systolic and diastolic BP showed a significant positive correlation with glycemic profile, including FBG, PP2, and HbA1c (>R2 = 0.47 to 0.7) in PE. Whereas proinflammatory markers did not show a significant correlation Iin PE with GDM women, significant positive correlation was observed between BP and glycemic profile (>R2 = 0.6 to 0.74) (Figure 6 and Figure 7A–D), similarly significant positive correlation was observed for systolic BP and diastolic BP (>R2 = 0. 41 to 0.84) with proinflammatory markers in PE (Figure 6 and Figure 7E,F). Pearson correlation graph for all the patient samples included in the Figures S1–S4 (Supplementary Materials).

Figure 4.

Pearson positive correlation analysis was observed for maternal age with glycemic profile and proinflammatory markers. (A) FBG, (B) PP1, (C) PP2, (D) HbA1c, (E) TNF-α, (F) IL-6.

Figure 5.

Pearson positive correlation analysis was observed for maternal weight with glycemic profile and proinflammatory markers. (A) FBG, (B) PP1, (C) PP2, (D) HbA1c, (E) TNF-α, (F) IL-6.

Figure 6.

Pearson positive correlation analysis was observed for systolic BP with glycemic profile and proinflammatory markers. (A) FBG, (B) PP1, (C) PP2, (D) HbA1c, (E) TNF-α, (F) IL-6.

Figure 7.

Pearson positive correlation analysis was observed for diastolic BP with glycemic profile and proinflammatory markers. (A) FBG, (B) PP1, (C) PP2, (D) HbA1c, (E) TNF-α, (F) IL-6.

4. Discussion

PE and GDM are among the most serious complications of pregnancy, contributing substantially to maternal and perinatal morbidity worldwide [1,2]. Their coexistence markedly increases the risk of adverse outcomes, including preterm delivery, FGR, and long-term cardiometabolic disease in both mother and offspring [5,27]. Although the two disorders differ clinically, they share overlapping pathophysiological features, notably systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and metabolic reprogramming [8,28,29]. The present study simultaneously examined immune, oxidative, nitrosative, neurovascular, and mitochondrial pathways in peripheral blood lymphocytes from women with PE alone, PE complicated by GDM, and normotensive pregnant controls. The integrated approach reveals a consistent pattern of immune hyper-responsiveness, impaired antioxidant capacity, heightened oxidative and nitrosative stress, cholinergic dysregulation, and a shift from mitochondrial respiration toward aerobic glycolysis.

A striking finding was the significantly enhanced proliferative response of lymphocytes to phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) in both PE and PE + GDM groups, most evident at higher mitogen concentrations. Heightened PHA-induced proliferation has been described in several pregnancy complications and is interpreted as evidence of pre-activated or “primed” T cells [30,31]. In normal pregnancy, maternal immunity is finely tuned to tolerate fetal alloantigens, with a bias toward Th2 and regulatory responses [32]. In contrast, PE is characterized by a shift toward Th1/Th17 dominance, increased circulating activated T cells, and reduced Treg suppression [33,34]. The enhanced proliferative response observed here aligns with this proinflammatory skew and is consistent with reports of increased T-cell activation markers (CD69, HLA-DR) in PE [35]. The even greater response in the PE + GDM group supports the concept of synergistic immune activation when metabolic and hypertensive insults converge [36,37].

This heightened lymphocyte reactivity was accompanied by markedly elevated production of IL-6 and TNF-α following PHA stimulation. Both cytokines are central orchestrators of the inflammatory milieu in PE and GDM [38]. TNF-α promotes endothelial activation, up-regulates adhesion molecules, and contributes to the anti-angiogenic state through stimulation of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) release [39]. IL-6, in turn, drives hepatic C-reactive protein synthesis, impairs insulin signaling via SOCS3 activation, and amplifies vascular inflammation [40,41]. The stronger cytokine elevation in the combined PE + GDM phenotype corroborates clinical observations that co-existing hyperglycemia exacerbates the inflammatory burden of PE [17]. Thus, circulating lymphocytes not only mirror but actively propagate the systemic inflammatory state characteristic of these disorders.

Oxidative stress is a well-recognized convergent pathway in PE and GDM [42,43]. We observed significant reductions in the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and glutathione-S-transferase (GST), coupled with increased lipid peroxidation (TBARS). GPx exhibited the most pronounced decline, consistent with its critical role in detoxifying lipid hydroperoxides generated during endothelial membrane damage [44,45]. The compromised antioxidant defense aligns with numerous placental and maternal blood studies in PE [16,46], and with evidence of hyperglycemia-driven ROS overproduction in GDM [47,48]. The additive effect in PE + GDM likely reflects the combined impact of placental ischemia–reperfusion injury and glucose-mediated oxidative pathways (polyol, hexosamine, and advanced glycation end-products) [49].

Nitric oxide bioavailability was significantly reduced, particularly in the PE + GDM cohort. NO is essential for maintaining vascular tone, inhibiting platelet aggregation, and limiting leukocyte adhesion [50]. Its depletion in PE arises from eNOS uncoupling, asymmetric dimethylarginine accumulation, and scavenging by superoxide to form peroxynitrite [51,52]. The greater NO deficit in the combined phenotype probably reflects intensified oxidative consumption and underscores the severity of endothelial dysfunction when metabolic and hypertensive stressors coexist [36].

We also documented reduced acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in disease groups. Although AChE is classically associated with synaptic transmission, non-neuronal cholinergic signaling modulates inflammation and vascular tone [53]. Lower AChE activity increases acetylcholine availability, which can exert anti-inflammatory effects via α7 nicotinic receptors on immune cells [54]. Paradoxically, chronic acetylcholine excess in a pro-oxidative environment may contribute to autonomic dysregulation and impaired uteroplacental perfusion [15,55]. The observed reduction may therefore represent a maladaptive response to sustained neurovascular stress.

Metabolic reprogramming of immune cells emerged as another prominent characteristic. Hexokinase activity was significantly elevated, whereas citrate synthase and cytochrome-c oxidase activities were suppressed. Heightened hexokinase reflects increased glycolytic flux, a hallmark of activated lymphocytes undergoing the Warburg effect to meet biosynthetic and energy demands rapidly [56,57]. Conversely, reduced citrate synthase and cytochrome-c oxidase indicate diminished mitochondrial oxidative capacity, consistent with ultrastructural and functional mitochondrial abnormalities reported in PE placentae and maternal leukocytes [58,59]. This metabolic shift is increasingly recognized in chronic inflammatory states and may perpetuate ROS production via electron transport chain leakage [14,60]. The parallel increase in glycolysis and mitochondrial impairment mirrors patterns seen in hypoxia-driven pathologies and reinforces the concept of bioenergetic stress as a common denominator in PE and GDM [61,62].

Correlation analyses further highlighted the interconnected nature of these disturbances. Maternal weight, blood pressure, glycemic indices, and proinflammatory cytokines showed strong positive inter-relationships, especially in the PE + GDM group. These findings are in agreement with epidemiological data linking pre-pregnancy obesity, excessive gestational weight gain, and insulin resistance to heightened PE risk and illustrate how adiposity amplifies inflammatory and oxidative pathways [63,64,65,66]. A recent study highlights that diverse etiological agents, including metabolic overload from obesity and ultra--processed diets, environmental pollutants, and infections, activate NF-κB/STAT signaling and sustained production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and chemokines). This exaggerated inflammatory milieu disrupts the normal transition between pro- and anti-inflammatory phases of gestation; impairs maternal–fetal immune tolerance; and contributes directly to major complications such as PE, GDM, PTB, and FGR through endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, and altered fetal programming [67]. Our previously published questionnaire-based study also supported that the use of processed foods and a modernized lifestyle contribute to various organ dysfunctions in PE and GDM [4].

The strengths of this study lie in its multi-parametric assessment within the same lymphocyte population, allowing direct linkage of immune activation with metabolic and redox alterations. By focusing on circulating immune cells rather than placental tissue, the results reflect systemic rather than localized pathology, which is relevant to the maternal syndrome of PE. Nevertheless, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, and the modest sample size, although comparable to many mechanistic studies in pregnancy, limits generalizability. Enzymatic assays, while well-established, provide indirect evidence of mitochondrial function; future studies employing high-resolution respirometry or Seahorse analysis would strengthen conclusions.

In conclusion, the present work demonstrates that PE and, to a greater extent, PE complicated by GDM are characterized by a coordinated immunometabolic disturbance in circulating lymphocytes: exaggerated proliferative and cytokine responses, depleted antioxidant defenses, reduced NO bioavailability, cholinergic dysregulation, and a shift from mitochondrial respiration to aerobic glycolysis. These alterations converge to perpetuate systemic inflammation, oxidative injury, and endothelial dysfunction. The lymphocyte profile described here may serve as an accessible window into the systemic pathology of these disorders for risk stratification and monitoring. Ultimately, targeting immune–metabolic crosstalk—through antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, or mitochondrial-protective strategies—could open new therapeutic avenues for these high-risk pregnancies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/reprodmed6040043/s1. Figure S1: Pearson positive correlation analysis was observed for maternal age with glycemic profile and proinflammatory markers. Figure S2: Pearson positive correlation analysis was observed for maternal weight with glycemic profile and proinflammatory markers. Figure S3: Pearson positive correlation analysis was observed for systolic BP with glycemic profile and proinflammatory markers. Figure S4: Pearson positive correlation analysis was observed for diastolic BP with glycemic profile and proinflammatory markers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B., H.P.P. and R.V.; methodology, U.R.B.; software, G.M.; validation, S.B. and R.V.; formal analysis, U.R.B. and R.S.N.; investigation, S.B. and R.V.; resources, H.P.P.; data curation, U.R.B., R.S.N. and G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, U.R.B.; writing—review and editing, R.V. and G.M.; visualization, U.R.B. and R.V.; supervision, H.P.P. and S.B.; project administration, R.V. and S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board [Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC)] of SRM Institute of Science and Technology. (Ethical Clearance number: 8469/IEC/2022 and date of approval: 26 May 2022) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The supporting data for this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions but can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the EDART lab students and the Department of Biotechnology, School of Bioengineering, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Kattankulathur campus, for their immense support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PE | Preeclampsia |

| GDM | Gestational Diabetes Mellitus |

| NP | Normotensive pregnant |

| FBG | Fasting Blood Glucose |

| PP1 | Postprandial glucose after 1 h |

| PP2 | Postprandial glucose after 2 h |

| HbA1c | Glycated Hemoglobin A1c |

| PHA | phytohemagglutinin |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| AChE | acetylcholine esterase |

| IL-6 | Interleukin- 6 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| FGR | Fetal growth restriction |

| PTB | Preterm birth |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | catalase |

| GPx | glutathione peroxidase |

| GST | glutathione S-transferase |

| HK | hexokinase |

| CS | citrate synthase |

| PK | pyruvate kinase |

| eNOS | endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| DIPSI | Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group India |

| PBMCs | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| MTT | (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide |

| DTNB | di-Thio-nitrobenzene |

| CDNB | 1-Chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene |

| SHS | Suboptimal Health Status |

| IUGR | Intrauterine growth restriction |

References

- Abalos, E.; Cuesta, C.; Carroli, G.; Qureshi, Z.; Widmer, M.; Vogel, J.P.; Souza, J.P. WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health Research Network Pre-Eclampsia, Eclampsia and Adverse Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes: A Secondary Analysis of the World Health Organization Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 121, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 222. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, e237–e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, A.A.; Devi Rajeswari, V. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus–A Metabolic and Reproductive Disorder. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balu, U.R.; Vasantharekha, R.; Paromita, C.; Ali, K.; Mudgal, G.; Kesari, K.K.; Seetharaman, B. Linking EDC-Laden Food Consumption and Modern Lifestyle Habits with Preeclampsia: A Non-Animal Approach to Identifying Early Diagnostic Biomarkers through Biochemical Alterations. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 194, 115073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankiewicz, K.; Szczerba, E.; Fijałkowska, A.; Sierdziński, J.; Issat, T.; Maciejewski, T.M. The Impact of Coexisting Gestational Diabetes Mellitus on the Course of Preeclampsia. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robillard, P.-Y.; Boukerrou, M.; Dekker, G.; Scioscia, M.; Bonsante, F.; Boumahni, B.; Iacobelli, S. Risk Factors for Early and Late Onset Preeclampsia in Reunion Island: Multivariate Analysis of Singleton and Twin Pregnancies. A 20-Year Population-Based Cohort of 2120 Preeclampsia Cases. Reprod. Med. 2021, 2, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, F.; Khan, M.F.; Moiz, A. Gestational diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia as the risk factors of preeclampsia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Lemoine, E.; Granger, J.P.; Karumanchi, S.A. Preeclampsia: Pathophysiology, Challenges, and Perspectives. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1094–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Torres, J.; Espino-y-Sosa, S.; Martinez-Portilla, R.; Borboa-Olivares, H.; Estrada-Gutierrez, G.; Acevedo-Gallegos, S.; Ruiz-Ramirez, E.; Velasco-Espin, M.; Cerda-Flores, P.; Ramirez-Gonzalez, A.; et al. A Narrative Review on the Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, D.C.; Cottrell, J.; Amaral, L.M.; LaMarca, B. Inflammatory Mediators: A Causal Link to Hypertension during Preeclampsia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 1914–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelen, V.; Şengül, E.; Atila, G.; Uslu, H.; Makav, M. Association of Gestational Diabetes and Proinflammatory Cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β). J. Embryol. 2017, 1, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P. Decidual Vasculopathy and Spiral Artery Remodeling Revisited III: Hypoxia and Re-Oxygenation Sequence with Vascular Regeneration. Reprod. Med. 2020, 1, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cindrova-Davies, T.; Yung, H.-W.; Johns, J.; Spasic-Boskovic, O.; Korolchuk, S.; Jauniaux, E.; Burton, G.J.; Charnock-Jones, D.S. Oxidative Stress, Gene Expression, and Protein Changes Induced in the Human Placenta during Labor. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 171, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.-Q.; Zhang, L. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2022, 24, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijomone, O.K.; Erukainure, O.L.; Shallie, P.; Naicker, T. Neurotoxicity in Pre-Eclampsia Involves Oxidative Injury, Exacerbated Cholinergic Activity and Impaired Proteolytic and Purinergic Activities in Cortex and Cerebellum. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2021, 40, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkova-Parlapanska, K.; Kostadinova-Slavova, D.; Angelova, M.; Sadi J Al-Dahwi, R.; Georgieva, E.; Goycheva, P.; Karamalakova, Y.; Nikolova, G. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Status in Pregnant Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Late-Onset Complication of Pre-Eclampsia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, N. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Preeclampsia: Correlation and Influencing Factors. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 831297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Du, N.; Sun, H.; Chen, L.; Bao, H.; Zhao, Q.; Qu, Q.; Ma, D.; Kwak-Kim, J.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Molecules on T Cell Subsets of Pregnancies with Preeclampsia and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2020, 142, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, H.P.; Sharma, U.; Gopinath, S.; Sharma, V.; Hima, L.; ThyagaRajan, S. Menstrual Cycle and Reproductive Aging Alters Immune Reactivity, NGF Expression, Antioxidant Enzyme Activities, and Intracellular Signaling Pathways in the Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells of Healthy Women. Brain Behav. Immun. 2013, 32, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbakht, M.; Pakbin, B.; Nikbakht Brujeni, G. Evaluation of a New Lymphocyte Proliferation Assay Based on Cyclic Voltammetry; an Alternative Method. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, H.P.; Pratap, U.P.; Nair, R.S.; Vasantharekha, R.; ThyagaRajan, S. Estrogen-Receptor Status Determines Differential Regulation of A1- and A2-Adrenoceptor-Mediated Cell Survival, Angiogenesis, and Intracellular Signaling Responses in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Med. Oncol. 2024, 41, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratap, U.P.; Hima, L.; Kannan, T.; Thyagarajan, C.; Priyanka, H.P.; Vasantharekha, R.; Pushparani, A.; Thyagarajan, S. Sex-Based Differences in the Cytokine Production and Intracellular Signaling Pathways in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arch. Rheumatol. 2020, 35, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratap, U.P.; Patil, A.; Sharma, H.R.; Hima, L.; Chockalingam, R.; Hariharan, M.M.; Shitoot, S.; Priyanka, H.P.; ThyagaRajan, S. Estrogen-Induced Neuroprotective and Anti-Inflammatory Effects Are Dependent on the Brain Areas of Middle-Aged Female Rats. Brain Res. Bull. 2016, 124, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratap, U.P.; Sharma, H.R.; Mohanty, A.; Kale, P.; Gopinath, S.; Hima, L.; Priyanka, H.P.; ThyagaRajan, S. Estrogen Upregulates Inflammatory Signals through NF-κB, IFN-γ, and Nitric Oxide via Akt/mTOR Pathway in the Lymph Node Lymphocytes of Middle-Aged Female Rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 29, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.S.; Patel, M.N.; Kannan, T.; Gour, S.; Hariharan, M.M.; Prasanna, V.; Thirumalai, A.; Chockalingam, R.; Vasantharekha, R.; ThyagaRajan, S.; et al. Effects of 17β-Estradiol and Estrogen Receptor Subtype-Specific Agonists on Jurkat E6.1 T-Cell Leukemia Cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2025, 106, 106057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasantharekha, R.; Priyanka, H.P.; Nair, R.S.; Hima, L.; Pratap, U.P.; Srinivasan, A.V.; ThyagaRajan, S. Alterations in Immune Responses Are Associated with Dysfunctional Intracellular Signaling in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells of Men and Women with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 2964–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yin, B.; Jiang, N.; Zhu, B. Effect of Combined Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Preeclampsia on Pregnancy Outcomes. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 52, 27065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro, E.U.; Mamerto, T.P.; Chung, G.; Villavieja, A.; Gaus, N.L.; Morgan, E.; Pineda-Cortel, M.R.B. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Harbinger of the Vicious Cycle of Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, G.J.; Redman, C.W.; Roberts, J.M.; Moffett, A. Pre-Eclampsia: Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. BMJ 2019, 366, l2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.; Nakashima, A.; Shima, T.; Ito, M. Th1/Th2/Th17 and Regulatory T-Cell Paradigm in Pregnancy. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2010, 63, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmochwal-Kolarz, D.; Kludka-Sternik, M.; Tabarkiewicz, J.; Kolarz, B.; Rolinski, J.; Leszczynska-Gorzelak, B.; Oleszczuk, J. The Predominance of Th17 Lymphocytes and Decreased Number and Function of Treg Cells in Preeclampsia. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2012, 93, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mor, G.; Aldo, P.; Alvero, A.B. The Unique Immunological and Microbial Aspects of Pregnancy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deer, E.; Herrock, O.; Campbell, N.; Cornelius, D.; Fitzgerald, S.; Amaral, L.M.; LaMarca, B. The Role of Immune Cells and Mediators in Preeclampsia. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2023, 19, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmon, A.C.; Cornelius, D.C.; Amaral, L.M.; Faulkner, J.L.; Cunningham, M.W.; Wallace, K.; LaMarca, B. The Role of Inflammation in the Pathology of Preeclampsia. Clin. Sci. 2016, 130, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toldi, G.; Rigó, J.; Stenczer, B.; Vásárhelyi, B.; Molvarec, A. Increased Prevalence of IL-17-Producing Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes in Pre-Eclampsia. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011, 66, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwain, C.J.; Tuboly, E.; McCarthy, F.P.; McCarthy, C.M. Mechanisms of Endothelial Dysfunction in Pre-Eclampsia and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Windows into Future Cardiometabolic Health? Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Duan, X.; Peng, W.; Liu, R.; Li, W.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Y. Association between Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Offspring Health: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2025, 25, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathy, R. Cytokines as Key Players in the Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia. Med. Princ. Pract. 2013, 22 (Suppl. S1), 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudihy, D.; Lee, R.V. The Pathophysiology of Pre-Eclampsia: Current Clinical Concepts. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2009, 29, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, O.P.; Mandrup-Poulsen, T. Interleukin-6 and Diabetes: The Good, the Bad, or the Indifferent? Diabetes 2005, 54 (Suppl. S2), S114–S124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, K.K.; Meeker, J.D.; McElrath, T.F.; Mukherjee, B.; Cantonwine, D.E. Repeated Measures of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Preeclamptic and Normotensive Pregnancies. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 216, 527.e1–527.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Aranguren, L.C.; Prada, C.E.; Riaño-Medina, C.E.; Lopez, M. Endothelial Dysfunction and Preeclampsia: Role of Oxidative Stress. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaka, V.R.; McMaster, K.M.; Cunningham, M.W.; Ibrahim, T.; Hazlewood, R.; Usry, N.; Cornelius, D.C.; Amaral, L.M.; LaMarca, B. Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Reactive Oxygen Species in Mediating Hypertension in the Reduced Uterine Perfusion Pressure Rat Model of Preeclampsia. Hypertension 2018, 72, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myatt, L.; Cui, X. Oxidative Stress in the Placenta. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 122, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijmakers, M.T.M.; Roes, E.M.; Poston, L.; Steegers, E.A.P.; Peters, W.H.M. The Transient Increase of Oxidative Stress during Normal Pregnancy Is Higher and Persists after Delivery in Women with Pre-Eclampsia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2008, 138, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, V.; Rani, A.; Patil, V.; Pisal, H.; Randhir, K.; Mehendale, S.; Wagh, G.; Gupte, S.; Joshi, S. Increased Oxidative Stress from Early Pregnancy in Women Who Develop Preeclampsia. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2016, 38, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappas, M.; Hiden, U.; Desoye, G.; Froehlich, J.; Hauguel-de Mouzon, S.; Jawerbaum, A. The Role of Oxidative Stress in the Pathophysiology of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2011, 15, 3061–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, M.T.; Vervaart, P.P.; Permezel, M.; Georgiou, H.M.; Rice, G.E. Altered Placental Oxidative Stress Status in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Placenta 2004, 25, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madazli, R.; Benian, A.; Gümüştaş, K.; Uzun, H.; Ocak, V.; Aksu, F. Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidants in Preeclampsia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1999, 85, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johal, T.; Lees, C.C.; Everett, T.R.; Wilkinson, I.B. The Nitric Oxide Pathway and Possible Therapeutic Options in Pre-Eclampsia. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 78, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, K.P.; Benyo, D.F. Placental Cytokines and the Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1997, 37, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possomato-Vieira, J.S.; Khalil, R.A. Mechanisms of Endothelial Dysfunction in Hypertensive Pregnancy and Preeclampsia. Adv. Pharmacol. 2016, 77, 361–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borovikova, L.V.; Ivanova, S.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Botchkina, G.I.; Watkins, L.R.; Wang, H.; Abumrad, N.; Eaton, J.W.; Tracey, K.J. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Attenuates the Systemic Inflammatory Response to Endotoxin. Nature 2000, 405, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klapproth, H.; Reinheimer, T.; Metzen, J.; Münch, M.; Bittinger, F.; Kirkpatrick, C.J.; Höhle, K.D.; Schemann, M.; Racké, K.; Wessler, I. Non-Neuronal Acetylcholine, a Signalling Molecule Synthezised by Surface Cells of Rat and Man. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1997, 355, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, F.K.; Mohammed, A.A.; Garmavy, H.M.; Rashid, H.M. Association of Reduced Maternal Plasma Cholinesterase Activity With Preeclampsia: A Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2023, 15, e47220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artyomov, M.N.; Van den Bossche, J. Immunometabolism in the Single-Cell Era. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 710–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Motomura, K.; Galaz, J.; Gershater, M.; Lee, E.D.; Romero, R.; Gomez-Lopez, N. Cellular Immune Responses in the Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2022, 111, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralimanoharan, S.; Maloyan, A.; Myatt, L. Mitochondrial Function and Glucose Metabolism in the Placenta with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Role of miR-143. Clin. Sci. 2016, 130, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.N.; Wang, X.; Thomas, D.G.; Tatum, R.E.; Booz, G.W.; Cunningham, M.W. The Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Preeclampsia: Causative Factor or Collateral Damage? Am. J. Hypertens. 2021, 34, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, R.; Chiarello, D.I.; Abad, C.; Rojas, D.; Toledo, F.; Sobrevia, L. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Early-Onset and Late-Onset Preeclampsia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, F.; Vasam, G.; Green, A.E.; Bainbridge, S.A.; Menzies, K.J. Placental Mitochondrial Function and Dysfunction in Preeclampsia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlapinski, S.K.; Hill, D.J. Metabolic Adaptations to Pregnancy in Healthy and Gestational Diabetic Pregnancies: The Pancreas–Placenta Axis. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2021, 19, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spradley, F.T.; Palei, A.C.; Granger, J.P. Immune Mechanisms Linking Obesity and Preeclampsia. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 3142–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, L.M.; Ness, R.B.; Markovic, N.; Roberts, J.M. The Risk of Preeclampsia Rises with Increasing Prepregnancy Body Mass Index. Ann. Epidemiol. 2005, 15, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lan, Y.; Shao, H.; Peng, L.; Chen, R.; Yu, H.; Hua, Y. Associations between Prepregnancy Body Mass Index, Gestational Weight Gain, and Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Twin Pregnancies: A Five-Year Prospective Study. Birth 2022, 49, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, P.M.; Shankar, K. Obesity and Pregnancy: Mechanisms of Short Term and Long Term Adverse Consequences for Mother and Child. BMJ 2017, 356, j1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-morales, A.; Lomas-soria, C.; Granados-higa, G.; García-quiroz, J.; Avila, E.; Olmos-ortiz, A.; Díaz, L. Inflammation in Pregnancy: Key Drivers, Signaling Pathways and Associated Complications. Arch. Med. Res. 2026, 2, 103301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).