Tricuspid Atresia and Fontan Circulation: Anatomy, Physiology, and Perioperative Considerations

Abstract

1. Introduction

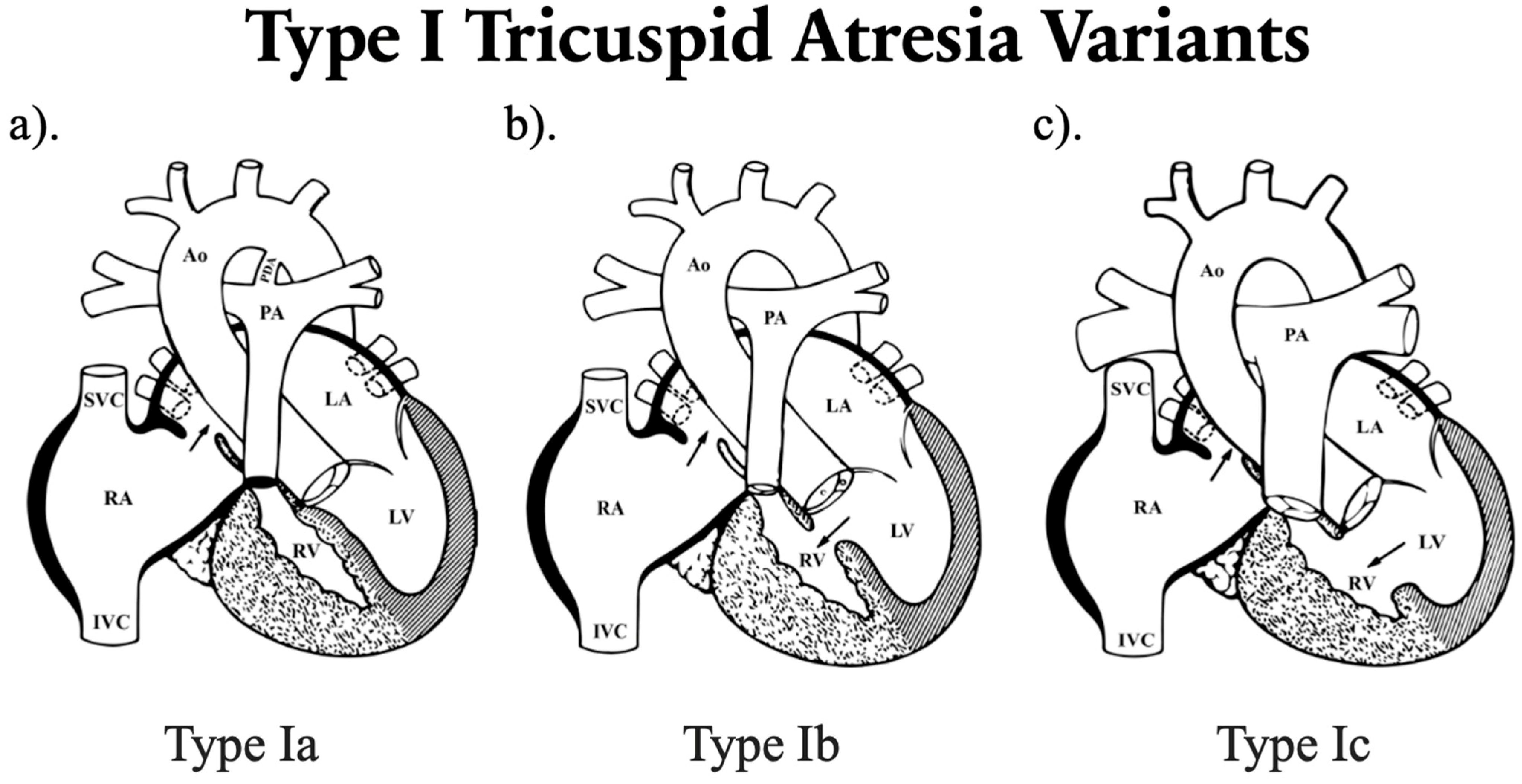

2. Classification

3. Genetic and Syndromic Associations

- VACTERL association, defined by vertebral anomalies such as hemivertebrae, fused vertebrae, or scoliosis; anal atresia including imperforate anus or other anorectal malformations; cardiac defects such as ASD, VSD, TGA, or tetralogy of Fallot (ToF); tracheoesophageal fistula with or without esophageal atresia; renal anomalies including renal agenesis, dysplasia, horseshoe kidney, or vesicoureteral reflux; and limb abnormalities such as radial aplasia, hypoplastic thumb, or polydactyly [20].

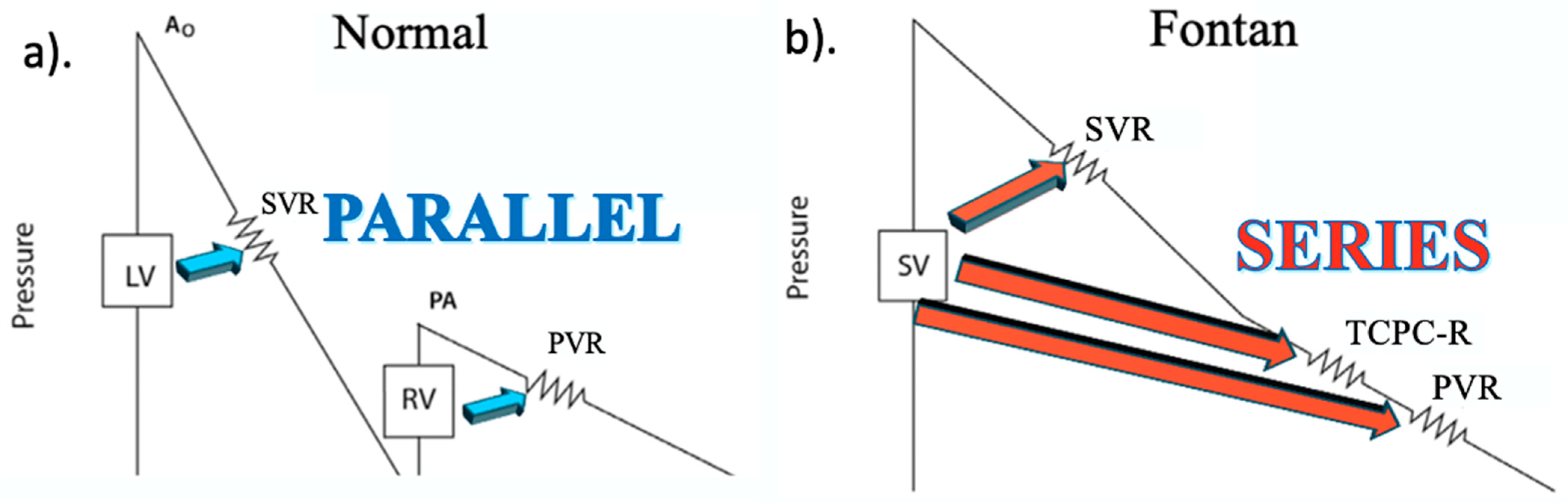

4. Pathophysiology

5. Clinical Presentation and Surgical Management

6. Surgical Palliation/Fontan Procedure

7. Perioperative Risk

8. Preoperative Assessment

8.1. History

8.2. Physical Examination

8.3. Auscultation

8.4. Electrocardiogram (ECG)

8.5. Two-Dimensional Echocardiography (2DE)

8.6. Three-Dimensional Echocardiography (3DE)

8.7. Computed Tomography (CT) Angiography

8.8. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR) Imaging

8.9. Cardiac Catheterization

9. Preoperative Optimization

9.1. Antibiotics

9.2. Anticoagulation

9.3. Lymphatic Drainage

10. Intraoperative Management

10.1. Positioning

10.2. Hemodynamics

10.3. Ventilation

11. Postoperative Management

12. Long-Term Outcomes

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | American College of Cardiology |

| ACCP | American College of Chest Physicians |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| Ao | Aorta |

| ASD | Atrial septal defect |

| ASE | American Society of Echocardiography |

| AP | Atriopulmonary |

| BDG | Bidirectional Glenn |

| CHD | Congenital heart disease |

| CPAP | Continuous positive airway pressure |

| CMR | Cardiac magnetic resonance |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| CTA | Computed tomography angiography |

| CVP | Central venous pressure |

| DKS | Damus–Kaye–Stansel |

| DOAC | Direct oral anticoagulant |

| D-TGA | Dextro-transposition of the great arteries |

| EACVI | European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging |

| EC | Extracardiac |

| ECV | Extracellular volume fraction |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| ETCO2 | End-tidal carbon dioxide |

| FALD | Fontan-associated liver disease |

| FiO2 | Fraction of inspired oxygen |

| IVC | Inferior vena cava |

| LA | Left atrium |

| LAP | Left atrial pressure |

| LGE | Late gadolinium enhancement |

| LPA | Left pulmonary artery |

| LT | Lateral tunnel (Fontan) |

| L-TGA | Levo-transposition of the great arteries |

| LV | Left ventricle |

| MAP | Mean arterial pressure |

| MAPCAs | Major aortopulmonary collateral arteries |

| mBTTS | Modified Blalock–Taussig–Thomas shunt |

| mPAP | Mean pulmonary artery pressure |

| MPA | Main pulmonary artery |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MRL | Magnetic resonance lymphangiography |

| NASCI | North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging |

| NRGA | Normally related great arteries |

| PA | Pulmonary artery |

| PaCO2 | Arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide |

| PAP | Pulmonary artery pressure |

| PDA | Patent ductus arteriosus |

| PDE-5 | Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor |

| PFO | Patent foramen ovale |

| PLE | Protein-losing enteropathy |

| PPV | Positive pressure ventilation |

| PVR | Pulmonary vascular resistance |

| Qp:Qs | Pulmonary-to-systemic flow ratio |

| RA | Right atrium |

| RPA | Right pulmonary artery |

| RV | Right ventricle |

| SCMR | Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance |

| SPR | Society for Pediatric Radiology |

| SVC | Superior vena cava |

| SV | Stroke volume |

| SVR | Systemic vascular resistance |

| TA | Tricuspid atresia |

| TCPC | Total cavopulmonary connection |

| TDE | Thoracic duct embolization |

| TEE | Transesophageal echocardiography |

| TGA | Transposition of the great arteries |

| TTE | Transthoracic echocardiography |

| VKA | Vitamin K antagonist (e.g., warfarin) |

| VSD | Ventricular septal defect |

| vWF | von Willebrand factor |

References

- Rowe, R.D.; Freedom, R.M.; Mehrizi, A.; Bloom, K.R. The Neonate with Congenital Heart Disease. Second Edition. Major Probl. Clin. Pediatr. 1981, 5, 3–716. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P.S. Demographic Features of Tricuspid Atresia. In Tricuspid Atresia; Rao, P.S., Ed.; Futura Publishing Co.: Mt. Kisco, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P.S. A Unified Classification for Tricuspid Atresia. Am. Heart J. 1980, 99, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhne, M. Über Zwei Fälle Kongenitaler Atresie Des Ostium Venosum Dextrum. Jahresber. Kinderheilkd. 1906, 63, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.E.; Burchell, H.B. Congenital Tricuspid Atresia; a Classification. Med. Clin. N. Am. 1949, 33, 1177–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, J.D.; Rowe, R.D.; Vlad, P. Heart Disease in Infancy and Childhood. J. Med. Educ. 1958, 33, 608. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, J.D.; Rowe, R.D.; Vlad, P. Tricuspid Atresia. In Heart Disease in Infancy and Childhood; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1967; pp. 518–541. [Google Scholar]

- Vlad, P. Tricuspid Atresia. In Heart Disease in Infancy and Childhood; Keith, J.D., Rowe, R.D., Vlad, P., Eds.; Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 518–541. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, A.M.; Lauer, R.M.; Shanker, K.R. Tricuspid Atresia. In Heart Disease in Infants, Children and Adolescents; Moss, A.J., Adams, F.H., Eds.; Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1968; pp. 517–526. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, A.; Dick, M. Tricuspid Atresia. In Moss’ Heart Disease in Infants, Children, and Adolescents; Adams, F., Emmanouilides, G., Riemenschneider, T., Eds.; Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cetta, F.; Dearani, J.A.; O’Leary, P.W. Tricuspid Valve Disorders: Atresia, Dysplasia, and Ebstein Anomaly. In Moss & Adams’ Heart Disease in Infants, Children, and Adolescents: Including the Fetus and Young Adult; Shaddy, R.E., Penny, D.J., Feltes, T.F., Cetta, F., Mital, S., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 1976–2026. ISBN 978-1-9751-1660-6. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, V.G.; DiNardo, J.A. Single-Ventricle Lesions. In The Pediatric Cardiac Anesthesia Handbook; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 161–180. ISBN 978-1-119-09556-9. [Google Scholar]

- Park, I.S.; Kim, S.-J.; Goo, H.W. Tricuspid Atresia. In An Illustrated Guide to Congenital Heart Disease: From Diagnosis to Treatment –From Fetus to Adult; Park, I.S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 253–267. ISBN 978-981-13-6978-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sleiman, A.-K.; Sadder, L.; Nemer, G. Human Genetics of Tricuspid Atresia and Univentricular Heart. In Congenital Heart Diseases: The Broken Heart: Clinical Features, Human Genetics and Molecular Pathways; Rickert-Sperling, S., Kelly, R.G., Haas, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 875–884. ISBN 978-3-031-44087-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.; Ji, X.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y.; Cheng, J.; Ma, D.; Cao, L.; Yi, L.; Xu, Z. 22q11.2 Microduplication in a Family with Recurrent Fetal Congenital Heart Disease. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2011, 54, e433–e436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, C.; David, F.; Hernández, M.; Argüero, R.; Ortegón, J.; Martínez, A.; López, D.; Jiménez, S.; Sánchez, A. Tricuspid Atresia Associated with Common Arterial Trunk and 22q11 Chromosome Deletion. Arch. Cardiol. Mex. 2003, 73, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miller, G.A.; Paneth, M.; Lennox, S.C. Surgical Management of Pulmonary Atresia with Intact Ventricular Septum in First Month of Life. Br. Heart J. 1973, 35, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Trost, D.; Engels, H.; Bauriedel, G.; Wiebe, W.; Schwanitz, G. Congenital cardiovascular malformations and chromosome microdeletions in 22q11.2. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 1999, 124, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizárraga, M.A.; Mintegui, S.; Sánchez Echániz, J.; Galdeano, J.M.; Pastor, E.; Cabrera, A. Heart malformations in trisomy 13 and trisomy 18. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 1991, 44, 605–610. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, R.M.; Tham, E.B.; McCrindle, B.W.; Goff, D.A.; McAuliffe, F.M.; Golding, F.; Jaeggi, E.T.; Hornberger, L.K.; Tworetzky, W.; Nield, L.E. Outcome after Prenatal Diagnosis of Tricuspid Atresia: A Multicenter Experience. Am. Heart J. 2007, 153, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, D.W.; Basson, C.T.; MacRae, C.A. New Understandings in the Genetics of Congenital Heart Disease. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 1996, 8, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Klamt, B.; Schumacher, N.; Glaeser, C.; Hansmann, I.; Fenge, H.; Gessler, M. Phenotypic Variability in Hey2 -/- Mice and Absence of HEY2 Mutations in Patients with Congenital Heart Defects or Alagille Syndrome. Mamm. Genome 2004, 15, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rassy, I.; Bou-Abdallah, J.; Al-Ghadban, S.; Bitar, F.; Nemer, G. Absence of NOTCH2 and Hey2 Mutations in a Familial Alagille Syndrome Case with a Novel Frameshift Mutation in JAG1. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part. A 2008, 146A, 937–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Frias, J.; Kondamudi, N.P. Alagille Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, J.D.; Tkachenko, N.; Soares, A.R. Ellis-van Creveld Syndrome. In GeneReviews®; Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington, Seattle: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, E.C.; Huggins, G.S.; Lin, H.; Clendenin, C.; Jiang, F.; Tufts, R.; Dardik, F.B.; Leiden, J.M. A Syndrome of Tricuspid Atresia in Mice with a Targeted Mutation of the Gene Encoding Fog-2. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallmeyer, B.; Fenge, H.; Nowak-Göttl, U.; Schulze-Bahr, E. Mutational Spectrum in the Cardiac Transcription Factor Gene NKX2.5 (CSX) Associated with Congenital Heart Disease. Clin. Genet. 2010, 78, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkozy, A.; Conti, E.; D’Agostino, R.; Digilio, M.C.; Formigari, R.; Picchio, F.; Marino, B.; Pizzuti, A.; Dallapiccola, B. ZFPM2/FOG2 and HEY2 Genes Analysis in Nonsyndromic Tricuspid Atresia. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2005, 133A, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Person, A.D.; Klewer, S.E.; Runyan, R.B. Cell Biology of Cardiac Cushion Development. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2005, 243, 287–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.S. Congenital Malformations of the Tricuspid Valve: Diagnosis and Management—Part I. Ann. Vasc. Med. Res. 2022, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakkak, W.; Alahmadi, M.H.; Oliver, T.I. Ventricular Septal Defect. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gillam-Krakauer, M.; Mahajan, K. Patent Ductus Arteriosus. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alahmadi, M.H.; Sharma, S. Major Aortopulmonary Collateral Arteries. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer, D.E.; Hsu, H.H.; Co-Vu, J.; Anderson, R.H.; Fricker, F.J. Ventricular Septal Defect. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.S.; Alapati, S. Tricuspid Atresia in the Neonate. Neonatol. Today 2012, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Agasthi, P.; Graziano, J.N. Pulmonary Artery Banding. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, V.G.; DiNardo, J.A. The Pediatric Cardiac Anesthesia Handbook; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1-119-83541-7. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, S.W. Congenital Heart Disease in the Newborn Requiring Early Intervention. Korean J. Pediatr. 2011, 54, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauser-Heaton, H.; Price, K.; Weber, R.; El-Said, H. Stenting of the Patent Ductus Arteriosus: A Meta-Analysis and Literature Review. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2023, 2, 101052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.S. Management of Congenital Heart Disease: State of the Art—Part II—Cyanotic Heart Defects. Children 2019, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leval, M.R.; McKay, R.; Jones, M.; Stark, J.; Macartney, F.J. Modified Blalock-Taussig Shunt. Use of Subclavian Artery Orifice as Flow Regulator in Prosthetic Systemic-Pulmonary Artery Shunts. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1981, 81, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahmadi, M.H.; Sharma, S.; Bishop, M.A. Modified Blalock-Taussig-Thomas Shunt. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Crupi, G.; Alfieri, O.; Locatelli, G.; Villani, M.; Parenzan, L. Results of Systemic-to-Pulmonary Artery Anastomosis for Tricuspid Atresia with Reduced Pulmonary Blood Flow. Thorax 1979, 34, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annecchino, F.P.; Fontan, F.; Chauve, A.; Quaegebeur, J. Palliative Reconstruction of the Right Ventricular Outflow Tract in Tricuspid Atresia: A Report of 5 Patients. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1980, 29, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, J.L.; Rothman, M.T.; Rees, M.R.; Parsons, J.M.; Blackburn, M.E.; Ruiz, C.E. Stenting of the Arterial Duct: A New Approach to Palliation for Pulmonary Atresia. Br. Heart J. 1992, 67, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siblini, G.; Rao, P.S.; Singh, G.K.; Tinker, K.; Balfour, I.C. Transcatheter Management of Neonates with Pulmonary Atresia and Intact Ventricular Septum. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Diagn. 1997, 42, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwi, M.; Choo, K.K.; Latiff, H.A.; Kandavello, G.; Samion, H.; Mulyadi, M.D. Initial Results and Medium-Term Follow-up of Stent Implantation of Patent Ductus Arteriosus in Duct-Dependent Pulmonary Circulation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 44, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullan, D.M.; Permut, L.C.; Jones, T.K.; Johnston, T.A.; Rubio, A.E. Modified Blalock-Taussig Shunt versus Ductal Stenting for Palliation of Cardiac Lesions with Inadequate Pulmonary Blood Flow. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 147, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minocha, P.K.; Horenstein, M.S.; Phoon, C. Tricuspid Atresia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rychik, J.; Atz, A.M.; Celermajer, D.S.; Deal, B.J.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Gewillig, M.H.; Hsia, T.-Y.; Hsu, D.T.; Kovacs, A.H.; McCrindle, B.W.; et al. Evaluation and Management of the Child and Adult with Fontan Circulation: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 140, e234–e284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilling, C.; Dalziel, K.; Nunn, R.; Du Plessis, K.; Shi, W.Y.; Celermajer, D.; Winlaw, D.; Weintraub, R.G.; Grigg, L.E.; Radford, D.J.; et al. The Fontan Epidemic: Population Projections from the Australia and New Zealand Fontan Registry. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 219, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontan, F.; Baudet, E. Surgical Repair of Tricuspid Atresia. Thorax 1971, 26, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leval, M.R.; Kilner, P.; Gewillig, M.; Bull, C. Total Cavopulmonary Connection: A Logical Alternative to Atriopulmonary Connection for Complex Fontan Operations. Exp. Stud. Early Clin. Experience. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1988, 96, 682–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leval, M.R.; Deanfield, J.E. Four Decades of Fontan Palliation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2010, 7, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelletti, C.; Como, A.; Giannico, S.; Marino, B. Inferior Vena Cava-Pulmonary Artery Extracardiac Conduit. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1990, 100, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Udekem, Y.; Iyengar, A.J.; Cochrane, A.D.; Grigg, L.E.; Ramsay, J.M.; Wheaton, G.R.; Penny, D.J.; Brizard, C.P. The Fontan Procedure Contemporary Techniques Have Improved Long-Term Outcomes. Circulation 2007, 116, I–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Kim, W.-H.; Lim, H.-G.; Lee, J.-Y. Outcome of 200 Patients after an Extracardiac Fontan Procedure. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2008, 136, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshaies, C.; Hamilton, R.M.; Shohoudi, A.; Trottier, H.; Poirier, N.; Aboulhosn, J.; Broberg, C.S.; Cohen, S.; Cook, S.; Dore, A.; et al. Thromboembolic Risk After Atriopulmonary, Lateral Tunnel, and Extracardiac Conduit Fontan Surgery. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahm, A.L.; Razzouk, J.A.; Foster, C.S.; Voleti, S.L.; Razzouk, A.J.; Fortuna, R.S. Does the External Pericardial Lateral Tunnel Fontan Pathway Enlarge to Accommodate Somatic Growth? A Preliminary Analysis. World J. Pediatr. Congenit. Heart Surg. 2024, 15, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Doorn, C.A.; Leval, M.R. de The Lateral Tunnel Fontan. Oper. Tech. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2006, 11, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nürnberg, J.H.; Ovroutski, S.; Alexi-Meskishvili, V.; Ewert, P.; Hetzer, R.; Lange, P.E. New Onset Arrhythmias After the Extracardiac Conduit Fontan Operation Compared with the Intraatrial Lateral Tunnel Procedure: Early and Midterm Results. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2004, 78, 1979–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, M.; Colan, S.D.; Rhodes, J.; DiNardo, J. Fontan Physiology Revisited. Anesth. Analg. 2015, 121, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodefeld, M.D.; Boyd, J.H.; Myers, C.D.; Presson, R.G.; Wagner, W.W.; Brown, J.W. Cavopulmonary Assist in the Neonate: An Alternative Strategy for Single-Ventricle Palliation. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2004, 127, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewillig, M.; Brown, S.C. The Fontan Circulation after 45 Years: Update in Physiology. Heart 2016, 102, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller-Hance, W.C. Anesthesia for Noncardiac Surgery in Children with Congenital Heart Disease. In A Practice of Anesthesia for Infants and Children, 6th ed.; Coté, C.J., Lerman, J., Anderson, B.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 534–559.e9. ISBN 978-0-323-42974-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sundareswaran, K.S.; Pekkan, K.; Dasi, L.P.; Whitehead, K.; Sharma, S.; Kanter, K.R.; Fogel, M.A.; Yoganathan, A.P. The Total Cavopulmonary Connection Resistance: A Significant Impact on Single Ventricle Hemodynamics at Rest and Exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 295, H2427–H2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbers-Visser, D.; Kapusta, L.; van Osch-Gevers, L.; Strengers, J.L.M.; Boersma, E.; de Rijke, Y.B.; Boomsma, F.; Bogers, A.J.J.C.; Helbing, W.A. Clinical Outcome 5 to 18 Years after the Fontan Operation Performed on Children Younger than 5 Years. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2009, 138, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, G.; Bährle, S. Contractility-Afterload Mismatch after the Fontan Operation. Cardiol. Young 2005, 15 (Suppl. 3), 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, B.G.; Posner, K.L.; Wong, J.K.; Oakes, D.A.; Kelly, N.E.; Domino, K.B.; Ramamoorthy, C. Factors Contributing to Adverse Perioperative Events in Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: A Structured Analysis of Cases from the Closed Claims Project: Adverse Perioperative Events in ACHD. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2015, 10, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, B.G.; Williams, G.D.; Ramamoorthy, C. Knowledge and Attitudes of Anesthesia Providers about Noncardiac Surgery in Adults with Congenital Heart Disease. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2014, 9, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.L.; DiNardo, J.A.; Odegard, K.C. Patients with Single Ventricle Physiology Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery Are at High Risk for Adverse Events. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2015, 25, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbitts, J.A.; Groenewald, C.B.; Mauermann, W.J.; Barbara, D.W.; Burkhart, H.M.; Warnes, C.A.; Oliver, W.C.; Flick, R.P. Outcomes of General Anesthesia for Noncardiac Surgery in a Series of Patients with Fontan Palliation. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2013, 23, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, C.; Lachmann, R.; Kaiser, C.; Kozlowski, P.; Stressig, R.; Schneider, M.; Asfour, B.; Herberg, U.; Breuer, J.; Gembruch, U.; et al. Prenatal Diagnosis of Tricuspid Atresia: Intrauterine Course and Outcome. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 35, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M.K.; Bergman, J.E.H.; Krikov, S.; Amar, E.; Cocchi, G.; Cragan, J.; de Walle, H.E.K.; Gatt, M.; Groisman, B.; Liu, S.; et al. Prenatal Diagnosis and Prevalence of Critical Congenital Heart Defects: An International Retrospective Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, M.; Rosenthal, A.; Bove, E.; Rao, P.S. The Clinical Profile of Tricuspid Atresia. In Tricuspid Atresia; Futura Publishing Company: Mount Kisco, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhorn, R.H. Evaluation and Management of the Cyanotic Neonate. Clin. Pediatr. Emerg. Med. 2008, 9, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.S. Tricuspid Atresia. In A Comprehensive Approach to Congenital Heart Diseases; Jaypee Brothers Medical Pub: New Delhi, India, 2020; pp. 397–413. ISBN 978-93-5270-195-7. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Tacy, T. Tricuspid Valve Atresia; UpToDate Inc.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Law, M.A.; Collier, S.A.; Sharma, S.; Tivakaran, V.S. Coarctation of the Aorta. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- McPhee, S.J. Clubbing. In Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations; Walker, H.K., Hall, W.D., Hurst, J.W., Eds.; Butterworths: Boston, MA, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-409-90077-4. [Google Scholar]

- Perloff, J.K. Cardiac Auscultation. Dis. A Mon. 1980, 26, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felner, J.M. The Second Heart Sound. In Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations; Walker, H.K., Hall, W.D., Hurst, J.W., Eds.; Butterworths: Boston, MA, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-409-90077-4. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, J.; Horenstein, M.S.; Kyriakopoulos, C. Pulmonary Stenosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Neill, C.A.; Brink, A.J. Left Axis Deviation in Tricuspid Atresia and Single Ventricle. Circulation 1955, 12, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davachi, F.; Lucas, R.V.; Moller, J.H. The Electrocardiogram and Vectorcardiogram in Tricuspid Atresia. Correlation with Pathologic Anatomy. Am. J. Cardiol. 1970, 25, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, P.; Poirier, N.; Mercier, L.-A. Univentricular Heart. Circulation 2007, 115, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, E.; Gaxiola, A. Diagnostic Contribution of the Vectorcardiogram in Hemodynamic Overloading of the Heart. Am. Heart J. 1960, 60, 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, P.; Neill, C. Vectorcardiographic Study in Ten Cases of Tricuspid Atresia. In Electrocardiography in Infants and Children; Cassels, D., Ziegler, R., Eds.; Grune and Stratton: New York, NY, USA, 1966; pp. 269–272. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R.P. Left Axis Deviation; an Electrocardiographic-Pathologic Correlation Study. Circulation 1956, 14, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, R.P. Peri-Infarction Block. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 1959, 2, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, R.; Gersony, W.M.; Nadas, A.S. The Electrocardiogram in Tricuspid Atresia and Pulmonary Atresia with Intact Ventricular Septum. Circulation 1966, 34, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peguero, J.G.; Lo Presti, S.; Perez, J.; Issa, O.; Brenes, J.C.; Tolentino, A. Electrocardiographic Criteria for the Diagnosis of Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 1694–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Kulungara, R.; Boineau, J. Electrovectorcardiographic Features of Tricuspid Atresia. In Tricuspid Atresia; Rao, P., Ed.; Futura Publishing Co.: Mount Kisco, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 141–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, E.W.; Deal, B.J.; Mirvis, D.M.; Okin, P.; Kligfield, P.; Gettes, L.S. AHA/ACCF/HRS Recommendations for the Standardization and Interpretation of the Electrocardiogram. Circulation 2009, 119, e251–e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, P.S. Echocardiography in the Diagnosis and Management of Tricuspid Atresia. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, L.; Forster, J.; Gamlin, W.; Duarte, N.; Burgess, O.; Harkness, A.; Li, W.; Simpson, J.; Bedair, R. A Practical Guideline for Performing a Comprehensive Transthoracic Echocardiogram in the Congenital Heart Disease Patient: Consensus Recommendations from the British Society of Echocardiography. Echo Res. Pract. 2022, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.; Castela, E. Transposition of the Great Arteries. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2008, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlettaz, R. Echocardiographic Evaluation of Patent Ductus Arteriosus in Preterm Infants. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.; Saurers, D.L.; Barker, P.C.A.; Cohen, M.S.; Colan, S.D.; Dwyer, J.; Forsha, D.; Friedberg, M.K.; Lai, W.W.; Printz, B.F.; et al. Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Pediatric Transthoracic Echocardiogram: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2024, 37, 119–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.S. Noninvasive Evaluation of Patients with Tricuspid Atresia (Roentgenography, Echocardiography, and Nuclear Angiography). In Tricuspid Atresia; Futura Publishing Co.: Mt. Kisco, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski, M.W.; Moore, S.M.; Kritzmire, S.M.; Thomas, A.; Goyal, A. Transposition of the Great Arteries. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P.S. Natural History of Ventricular Septal Defects in Tricuspid Atresia. In Tricuspid Atresia; Futura Publishing Co.: Mt. Kisco, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 261–293. [Google Scholar]

- Goo, H.W. Double Outlet Right Ventricle: In-Depth Anatomic Review Using Three-Dimensional Cardiac CT Data. Korean J. Radiol. 2021, 22, 1894–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhansali, S.; Horenstein, M.S.; Phoon, C. Truncus Arteriosus. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, S.; Walker, S.; Loudon, B.L.; Gollop, N.D.; Wilson, A.M.; Lowery, C.; Frenneaux, M.P. Assessment of Pulmonary Artery Pressure by Echocardiography—A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2016, 12, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Oh, J.H. Echocardiographic Diagnosis of Right-to-Left Shunt Using Transoesophageal and Transthoracic Echocardiography. Open Heart 2020, 7, e001150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, J.; Lopez, L.; Acar, P.; Friedberg, M.K.; Khoo, N.S.; Ko, H.H.; Marek, J.; Marx, G.; McGhie, J.S.; Meijboom, F.; et al. Three-Dimensional Echocardiography in Congenital Heart Disease: An Expert Consensus Document from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017, 30, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirali, G.S. Three Dimensional Echocardiography in Congenital Heart Defects. Ann. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2008, 1, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanaki, A.; Kabir, S.; Stephenson, N.; van Poppel, M.P.M.; Benetti, V.; Simpson, J. 3D Approaches in Complex CHD: Where Are We? Funny Printing and Beautiful Images, or a Useful Tool? J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turton, E.W.; Ender, J. Role of 3D Echocardiography in Cardiac Surgery: Strengths and Limitations. Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 2017, 7, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saremi, F.; Hassani, C.; Millan-Nunez, V.; Sánchez-Quintana, D. Imaging Evaluation of Tricuspid Valve: Analysis of Morphology and Function with CT and MRI. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015, 204, W531–W542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.K.; Lesser, J.R. CT Imaging in Congenital Heart Disease: An Approach to Imaging and Interpreting Complex Lesions after Surgical Intervention for Tetralogy of Fallot, Transposition of the Great Arteries, and Single Ventricle Heart Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2013, 7, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.S.; Haramati, L.B.; Chen, J.J.-S.; Levsky, J.M. Cardiac Imaging; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-19-982947-7. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, J.R.; Hernandez, R.J. Role of CT in the Evaluation of Congenital Cardiovascular Disease in Children. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2009, 192, 1219–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Bhatia, M. Computed Tomography in the Evaluation of Fontan Circulation. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 29, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiner, T.; Bogaert, J.; Friedrich, M.G.; Mohiaddin, R.; Muthurangu, V.; Myerson, S.; Powell, A.J.; Raman, S.V.; Pennell, D.J. SCMR Position Paper (2020) on Clinical Indications for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2020, 22, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puricelli, F.; Voges, I.; Gatehouse, P.; Rigby, M.; Izgi, C.; Pennell, D.J.; Krupickova, S. Performance of Cardiac MRI in Pediatric and Adult Patients with Fontan Circulation. Radiol. Cardiothorac. Imaging 2022, 4, e210235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detterich, J.; Taylor, M.D.; Slesnick, T.C.; DiLorenzo, M.; Hlavacek, A.; Lam, C.Z.; Sachdeva, S.; Lang, S.M.; Campbell, M.J.; Gerardin, J.; et al. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Determine Single Ventricle Function in a Pediatric Population Is Feasible in a Large Trial Setting: Experience from the Single Ventricle Reconstruction Trial Longitudinal Follow Up. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2023, 44, 1454–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse-Wortmann, L.; Wald, R.M.; Valverde, I.; Valsangiacomo-Buechel, E.; Ordovas, K.; Raimondi, F.; Browne, L.; Babu-Narayan, S.V.; Krishnamurthy, R.; Yim, D.; et al. Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Guidelines for Reporting Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Examinations in Patients with Congenital Heart Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2024, 26, 101062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegari, A.; Marcora, S.; Burkhardt, B.; Voutat, M.; Kellenberger, C.J.; Geiger, J.; Valsangiacomo Buechel, E.R. Myocardial Deformation in Fontan Patients Assessed by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Feature Tracking: Correlation with Function, Clinical Course, and Biomarkers. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2021, 42, 1625–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijnberg, F.M.; Westenberg, J.J.M.; van Assen, H.C.; Juffermans, J.F.; Kroft, L.J.M.; van den Boogaard, P.J.; Terol Espinosa de Los Monteros, C.; Warmerdam, E.G.; Leiner, T.; Grotenhuis, H.B.; et al. 4D Flow Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Derived Energetics in the Fontan Circulation Correlate with Exercise Capacity and CMR-Derived Liver Fibrosis/Congestion. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2022, 24, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijnberg, F.M.; Hazekamp, M.G.; Wentzel, J.J.; de Koning, P.J.H.; Westenberg, J.J.M.; Jongbloed, M.R.M.; Blom, N.A.; Roest, A.A.W. Energetics of Blood Flow in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2018, 137, 2393–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.; Riesenkampff, E.; Yim, D.; Yoo, S.-J.; Seed, M.; Grosse-Wortmann, L. Pediatric Fontan Patients Are at Risk for Myocardial Fibrotic Remodeling and Dysfunction. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 240, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwaki, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Wada, N.; Saiki, Y.; Nagai, K.; Nogami, A.; Kawai, S.; Koyama, S.; Utsunomiya, D.; Nakajima, A.; et al. Efficacy of Magnetic Resonance Elastography in Fontan-Associated Liver Disease. JGH Open 2025, 9, e70274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiina, Y.; Inai, K.; Shimada, E.; Sakai, R.; Tokushige, K.; Niwa, K.; Nagao, M. Abdominal Lymphatic Pathway in Fontan Circulation Using Non-Invasive Magnetic Resonance Lymphangiography. Heart Vessel. 2023, 38, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, R.J.; Stirrat, C.G.; Semple, S.I.R.; Newby, D.E.; Dweck, M.R.; Mirsadraee, S. Assessment of Myocardial Fibrosis with T1 Mapping MRI. Clin. Radiol. 2016, 71, 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogel, M.A.; Anwar, S.; Broberg, C.; Browne, L.; Chung, T.; Johnson, T.; Muthurangu, V.; Taylor, M.; Valsangiacomo-Buechel, E.; Wilhelm, C. Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance/European Society of Cardiovascular Imaging/American Society of Echocardiography/Society for Pediatric Radiology/North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging Guidelines for the Use of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Pediatric Congenital and Acquired Heart Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2022, 24, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltes, T.F.; Bacha, E.; Beekman, R.H.; Cheatham, J.P.; Feinstein, J.A.; Gomes, A.S.; Hijazi, Z.M.; Ing, F.F.; de Moor, M.; Morrow, W.R.; et al. Indications for Cardiac Catheterization and Intervention in Pediatric Cardiac Disease. Circulation 2011, 123, 2607–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, W.R.; Gewitz, M.; Lockhart, P.B.; Bolger, A.F.; DeSimone, D.C.; Kazi, D.S.; Couper, D.J.; Beaton, A.; Kilmartin, C.; Miro, J.M.; et al. Prevention of Viridans Group Streptococcal Infective Endocarditis: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e963–e978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monagle, P.; Cochrane, A.; McCrindle, B.; Benson, L.; Williams, W.; Andrew, M. Thromboembolic Complications after Fontan Procedures--the Role of Prophylactic Anticoagulation. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1998, 115, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monagle, P.; Karl, T.R. Thromboembolic Problems after the Fontan Operation. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. Pediatr. Card. Surg. Annu. 2002, 5, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkiewicz-Pajak, L.; Hoffman, P.; Trojnarska, O.; Lipczyńska, M.; Podolec, P.; Undas, A. Abnormalities in Blood Coagulation, Fibrinolysis, and Platelet Activation in Adult Patients after the Fontan Procedure. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 147, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, J.M.; Mirhaidari, G.J.M.; Chang, Y.-C.; Shinoka, T.; Breuer, C.K.; Yates, A.R.; Hor, K.N. Evaluating the Longevity of the Fontan Pathway. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2020, 41, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Helm, S.; Sparks, C.N.; Ignjatovic, V.; Monagle, P.; Attard, C. Increased Risk for Thromboembolism After Fontan Surgery: Considerations for Thromboprophylaxis. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 803408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E.W.Y.; Chay, G.W.; Ma, E.S.K.; Cheung, Y. Systemic Oxygen Saturation and Coagulation Factor Abnormalities before and after the Fontan Procedure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 96, 1571–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odegard, K.C.; McGowan, F.X.; Zurakowski, D.; DiNardo, J.A.; Castro, R.A.; del Nido, P.J.; Laussen, P.C. Procoagulant and Anticoagulant Factor Abnormalities Following the Fontan Procedure: Increased Factor VIII May Predispose to Thrombosis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2003, 125, 1260–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, C.; Huang, J.; Monagle, P.; Ignjatovic, V. Pathophysiology of Thrombosis and Anticoagulation Post Fontan Surgery. Thromb. Res. 2018, 172, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, M.; Kreutzer, J.; Zurakowski, D.; Bacha, E.; Jonas, R.A. Evaluation of Hemostatic and Coagulation Factor Abnormalities in Patients Undergoing the Fontan Operation. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2000, 120, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odegard, K.C.; McGowan, F.X.; Zurakowski, D.; DiNardo, J.A.; Castro, R.A.; del Nido, P.J.; Laussen, P.C. Coagulation Factor Abnormalities in Patients with Single-Ventricle Physiology Immediately Prior to the Fontan Procedure. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2002, 73, 1770–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rychik, J.; Dodds, K.M.; Goldberg, D.; Glatz, A.C.; Fogel, M.; Rossano, J.; Chen, J.; Pinto, E.; Ravishankar, C.; Rand, E.; et al. Protein Losing Enteropathy After Fontan Operation: Glimpses of Clarity Through the Lifting Fog. World J. Pediatr. Congenit. Heart Surg. 2020, 11, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Balushi, A.; Mackie, A.S. Protein-Losing Enteropathy Following Fontan Palliation. Can. J. Cardiol. 2019, 35, 1857–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eynde, J.; Possner, M.; Alahdab, F.; Veldtman, G.; Goldstein, B.H.; Rathod, R.H.; Hoskoppal, A.K.; Saraf, A.; Feingold, B.; Alsaied, T. Thromboprophylaxis in Patients with Fontan Circulation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monagle, P.; Chan, A.K.C.; Goldenberg, N.A.; Ichord, R.N.; Journeycake, J.M.; Nowak-Göttl, U.; Vesely, S.K. Antithrombotic Therapy in Neonates and Children: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th Ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. CHEST 2012, 141, e737S–e801S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berganza, F.M.; Alba, C.G.; de Egbe, A.C.; Bartakian, S.; Brownlee, J. Prevalence of Aspirin Resistance by Thromboelastography plus Platelet Mapping in Children with CHD: A Single-Centre Experience. Cardiol. Young 2019, 29, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Singh, R.; Preuss, C.V.; Patel, N. Warfarin. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- McCrindle, B.W.; Michelson, A.D.; Van Bergen, A.H.; Suzana Horowitz, E.; Pablo Sandoval, J.; Justino, H.; Harris, K.C.; Jefferies, J.L.; Miriam Pina, L.; Peluso, C.; et al. Thromboprophylaxis for Children Post-Fontan Procedure: Insights from the UNIVERSE Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e021765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, R.M.; Burns, K.M.; Glatz, A.C.; Li, D.; Li, X.; Monagle, P.; Newburger, J.W.; Swan, E.A.; Wheaton, O.; Male, C. A Multi-National Trial of a Direct Oral Anticoagulant in Children with Cardiac Disease: Design and Rationale of the SAXOPHONE Study. Am. Heart J. 2019, 217, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaied, T.; Possner, M.; Van den Eynde, J.; Kreutzer, J. Anticoagulation Algorithm for Fontan Patients. 2023. Available online: https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2023/04/05/14/10/Anticoagulation-Algorithm-For-Fontan-Patients (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- d’Udekem, Y.; Iyengar, A.J.; Galati, J.C.; Forsdick, V.; Weintraub, R.G.; Wheaton, G.R.; Bullock, A.; Justo, R.N.; Grigg, L.E.; Sholler, G.F.; et al. Redefining Expectations of Long-Term Survival After the Fontan Procedure. Circulation 2014, 130, S32–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Chennapragada, M.; Ugaki, S.; Sholler, G.F.; Ayer, J.; Winlaw, D.S. The Lymphatic Circulation in Adaptations to the Fontan Circulation. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2017, 38, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leval, M.R. The Fontan Circulation: A Challenge to William Harvey? Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2005, 2, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RochéRodríguez, M.; DiNardo, J.A. The Lymphatic System in the Fontan Patient—Pathophysiology, Imaging, and Interventions: What the Anesthesiologist Should Know. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2022, 36, 2669–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, G.A.; Gribaudo, E.; Agnoletti, G. The Pathophysiology and Complications of Fontan Circulation. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, A.S.; Veldtman, G.R.; Thorup, L.; Hjortdal, V.E.; Dori, Y. Plastic Bronchitis and Protein-Losing Enteropathy in the Fontan Patient: Evolving Understanding and Emerging Therapies. Can. J. Cardiol. 2022, 38, 988–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciliberti, P.; Ciancarella, P.; Bruno, P.; Curione, D.; Bordonaro, V.; Lisignoli, V.; Panebianco, M.; Chinali, M.; Secinaro, A.; Galletti, L.; et al. Cardiac Imaging in Patients After Fontan Palliation: Which Test and When? Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 876742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasulo, C.E.; Chen, J.M.; Smith, C.L.; Maeda, K.; Rome, J.J.; Dori, Y. Lymphatic Disorders and Management in Patients with Congenital Heart Disease. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 113, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P.D.; Jobes, D.R. The Fontan Patient. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2009, 27, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redington, A. The Physiology of the Fontan Circulation. Progress. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2006, 22, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senzaki, H.; Masutani, S.; Ishido, H.; Taketazu, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Sasaki, N.; Asano, H.; Katogi, T.; Kyo, S.; Yokote, Y. Cardiac Rest and Reserve Function in Patients with Fontan Circulation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, 2528–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimes, K.; Abdul-Khaliq, H.; Ovroutski, S.; Hui, W.; Alexi-Meskishvili, V.; Spors, B.; Hetzer, R.; Felix, R.; Lange, P.E.; Berger, F.; et al. Pulmonary and Caval Blood Flow Patterns in Patients with Intracardiac and Extracardiac Fontan: A Magnetic Resonance Study. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2007, 96, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbers-Visser, D.; Helderman, F.; Strengers, J.L.; van Osch-Gevers, L.; Kapusta, L.; Pattynama, P.M.; Bogers, A.J.; Krams, R.; Helbing, W.A. Pulmonary Artery Size and Function after Fontan Operation at a Young Age. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2008, 28, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gewillig, M. THE FONTAN CIRCULATION. Heart 2005, 91, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewillig, M.; Boshoff, D.E. Missing a Sub-Pulmonary Ventricle: The Fontan Circulation. In The Right Ventricle in Health and Disease; Voelkel, N.F., Schranz, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 135–157. ISBN 978-1-4939-1065-6. [Google Scholar]

- Khambadkone, S. The Fontan Pathway: What’s the down Road? Ann. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2008, 1, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, M.R.; Nasr, V.G. Failing Fontan. In Congenital Cardiac Anesthesia: A Case-based Approach; Spaeth, J.P., Berenstain, L.K., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 226–238. ISBN 978-1-108-49416-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gewillig, M.; Brown, S.C.; Eyskens, B.; Heying, R.; Ganame, J.; Budts, W.; La Gerche, A.; Gorenflo, M. The Fontan Circulation: Who Controls Cardiac Output? Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2010, 10, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeije, R.; Vachiery, J.-L.; Yerly, P.; Vanderpool, R. The Transpulmonary Pressure Gradient for the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Vascular Disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 41, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widrich, J.; Shetty, M. Physiology, Pulmonary Vascular Resistance. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, G.; Koestenberger, M.; Alastalo, T.-P.; Apitz, C.; Austin, E.D.; Bonnet, D.; Budts, W.; D’Alto, M.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Hasan, B.S.; et al. 2019 Updated Consensus Statement on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension: The European Pediatric Pulmonary Vascular Disease Network (EPPVDN), Endorsed by AEPC, ESPR and ISHLT. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2019, 38, 879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, S.S.; Feinstein, J.A. Pulmonary Vascular Disease in the Single-Ventricle Patient: Is It Really Pulmonary Hypertension and If So, How and When Should We Treat It? Adv. Pulm. Hypertens. 2019, 18, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagle, S.S.; Daves, S.M. The Adult with Fontan Physiology: Systematic Approach to Perioperative Management for Noncardiac Surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2011, 25, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Su, Z.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Y. Nitric Oxide and Milrinone: Combined Effect on Pulmonary Circulation after Fontan-Type Procedure: A Prospective, Randomized Study. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2008, 86, 882–888; discussion 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoon, R.; Makhija, N.; Jangid, S.K. Balancing a Single-Ventricle Circulation: ‘Physiology to Therapy’. Indian. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 36, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.; Uebing, A.; Hansen, J.H. Pulmonary Vascular Disease in Fontan Circulation—Is There a Rationale for Pulmonary Vasodilator Therapies? Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2021, 11, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greaney, D.; Honjo, O.; O’Leary, J.D. The Single Ventricle Pathway in Paediatrics for Anaesthetists. BJA Educ. 2019, 19, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, S.R.; Hurwitz, R.A.; Caldwell, R.L.; Girod, D.A. Ventricular Function in the Single Ventricle before and after Fontan Surgery. Am. J. Cardiol. 1991, 67, 1390–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, T.; Benson, L.N.; Green, M.; Ash, J.; Gilday, D.L.; Williams, W.G.; Freedom, R.M. Ventricular Performance before and after Fontan Repair for Univentricular Atrioventricular Connection: Angiographic and Radionuclide Assessment. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1992, 20, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bigelow, A.M.; Ghanayem, N.S.; Thompson, N.E.; Scott, J.P.; Cassidy, L.D.; Woods, K.J.; Woods, R.K.; Mitchell, M.E.; Hraŝka, V.; Hoffman, G.M. Safety and Efficacy of Vasopressin After Fontan Completion: A Randomized Pilot Study. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 108, 1865–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, J.; Townsley, M.M.; Briston, D.; Villablanca, P.A.; Alegria, J.R.; Ramakrishna, H. Fontan Palliation for Single-Ventricle Physiology: Perioperative Management for Noncardiac Surgery and Analysis of Outcomes. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2017, 31, 2296–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyvi, G.; Wasnick, J.D. Single-Ventricle Patient: Pathophysiology and Anesthetic Management. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2010, 24, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, A.; Tomkiewicz, L.; Podolec, P.; Tracz, W.; Malec, E. Cardiorespiratory Response to Exercise in Children after Modified Fontan Operation. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2002, 36, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellers, T.M.; Driscoll, D.J.; Mottram, C.D.; Puga, F.J.; Schaff, H.V.; Danielson, G.K. Exercise Tolerance and Cardiorespiratory Response to Exercise before and after the Fontan Operation. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1989, 64, 1489–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewillig, M.H.; Lundström, U.R.; Bull, C.; Wyse, R.K.; Deanfield, J.E. Exercise Responses in Patients with Congenital Heart Disease after Fontan Repair: Patterns and Determinants of Performance. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1990, 15, 1424–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, R.G.; Satomi, G.; Yoshigi, M.; Momma, K. Maximal Hemodynamic Response after the Fontan Procedure: Doppler Evaluation during the Treadmill Test. Pediatr. Cardiol. 1994, 15, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takken, T.; Tacken, M.H.; Blank, A.C.; Hulzebos, E.H.; Strengers, J.L.; Helders, P.J. Exercise Limitation in Patients with Fontan Circulation: A Review. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2007, 8, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaufox, A.D.; Sleeper, L.A.; Bradley, D.J.; Breitbart, R.E.; Hordof, A.; Kanter, R.J.; Stephenson, E.A.; Stylianou, M.; Vetter, V.L.; Saul, J.P.; et al. Functional Status, Heart Rate, and Rhythm Abnormalities in 521 Fontan Patients 6 to 18 Years of Age. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2008, 136, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowton, G.E.; Balcon, R.; Cross, D.; Frick, M.H. Measurement of the Angina Threshold Using Atrial Pacing. A New Technique for the Study of Angina Pectoris. Cardiovasc. Res. 1967, 1, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, G.; Di Sessa, T.; Child, J.S.; Perloff, J.K.; Laks, H.; George, B.L.; Williams, R.G. Hemodynamic Responses to Isolated Increments in Heart Rate by Atrial Pacing after a Fontan Procedure. Am. Heart J. 1988, 115, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Linde, D.; Konings, E.E.M.; Slager, M.A.; Witsenburg, M.; Helbing, W.A.; Takkenberg, J.J.M.; Roos-Hesselink, J.W. Birth Prevalence of Congenital Heart Disease Worldwide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Duca, D.; Tadevosyan, A.; Karbassi, F.; Akhavein, F.; Vaniotis, G.; Rodaros, D.; Villeneuve, L.R.; Allen, B.G.; Nattel, S.; Rohlicek, C.V.; et al. Hypoxia in Early Life Is Associated with Lasting Changes in Left Ventricular Structure and Function at Maturity in the Rat. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012, 156, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.M.; Seslar, S.P.; den Boer, K.; Juraszek, A.L.; McGowan, F.X.; Cowan, D.B.; Nido, P.D.; Triedman, J.K.; Berul, C.I.; Walsh, E.P. Atrial Remodeling After the Fontan Operation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009, 104, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlqvist, J.A.; Karlsson, M.; Wiklund, U.; Hörnsten, R.; Strömvall-Larsson, E.; Berggren, H.; Hanseus, K.; Johansson, S.; Rydberg, A. Heart Rate Variability in Children with Fontan Circulation: Lateral Tunnel and Extracardiac Conduit. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2012, 33, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stee, E.W. Autonomic Innervation of the Heart. Environ. Health Perspect. 1978, 26, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.-Y.; Huang, H.; Tang, Y.-H.; Wang, X.; Okello, E.; Liang, J.-J.; Jiang, H.; Huang, C.-X. Relationship between Autonomic Innervation in Crista Terminalis and Atrial Arrhythmia. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2009, 20, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, R.A. The Intra/Extracardiac Conduit Fenestrated Fontan. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. Pediatr. Card. Surg. Annu. 2011, 14, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodefeld, M.D.; Bromberg, B.I.; Schuessler, R.B.; Boineau, J.P.; Cox, J.L.; Huddleston, C.B. Atrial Flutter after Lateral Tunnel Construction in the Modified Fontan Operation: A Canine Model. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1996, 111, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Khairy, P.; Poirier, N. Is the Extracardiac Conduit the Preferred Fontan Approach for Patients with Univentricular Hearts? The Extracardiac Conduit Is Not the Preferred Fontan Approach for Patients with Univentricular Hearts. Circulation 2012, 126, 2516–2525; discussion 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, A.N.; Nair, K.; Fish, F.A.; Khairy, P. Catheter Ablation of Atrial Arrhythmias in Patients Post-Fontan. Can. J. Cardiol. 2022, 38, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, J.R.; McMahon, A.; Griffin, M. Perioperative Management of the Fontan Patient for Cardiac and Noncardiac Surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2022, 36, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unegbu, C.; Deutsch, N. Extracardiac Fontan. In Congenital Cardiac Anesthesia: A Case-based Approach; Spaeth, J.P., Berenstain, L.K., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 217–225. ISBN 978-1-108-49416-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, N.D.; Lock, J.E.; Castaneda, A.R. Baffle Fenestration with Subsequent Transcatheter Closure. Modification of the Fontan Operation for Patients at Increased Risk. Circulation 1990, 82, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertens, L.; Hagler, D.J.; Sauer, U.; Somerville, J.; Gewillig, M. Protein-Losing Enteropathy after the Fontan Operation: An International Multicenter Study. PLE Study Group. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1998, 115, 1063–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutzer, J.; Lock, J.E.; Jonas, R.A.; Keane, J.F. Transcatheter Fenestration Dilation and/or Creation in Postoperative Fontan Patients. Am. J. Cardiol. 1997, 79, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemler, M.S.; Scott, W.A.; Leonard, S.R.; Stromberg, D.; Ramaciotti, C. Fenestration Improves Clinical Outcome of the Fontan Procedure: A Prospective, Randomized Study. Circulation 2002, 105, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, N.D.; Castaneda, A.R. The Fenestrated Fontan Procedure. Herz 1992, 17, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nayak, S.; Booker, P.D. The Fontan Circulation. Contin. Educ. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain. 2008, 8, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, V.G.; Markham, L.W.; Clay, M.; DiNardo, J.A.; Faraoni, D.; Gottlieb-Sen, D.; Miller-Hance, W.C.; Pike, N.A.; Rotman, C.; on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young and Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention. Perioperative Considerations for Pediatric Patients with Congenital Heart Disease Presenting for Noncardiac Procedures: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2023, 16, e000113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNardo, J.A.; Shukla, A.C.; McGowan, F.X. Anesthesia for Congenital Heart Surgery. In Smith’s Anesthesia for Infants and Children; Mosby: St. Louis, Mo, USA, 2011; pp. 605–673. ISBN 978-0-323-06612-9. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, V.C. The Adult Patient with Congenital Heart Disease. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 1996, 10, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, C.L.; d’Udekem, Y. Life After Surviving Fontan Surgery: A Meta-Analysis of the Incidence and Predictors of Late Death. Heart Lung Circ. 2018, 27, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittiwangkul, R.; Azakie, A.; Van Arsdell, G.S.; Williams, W.G.; McCrindle, B.W. Outcomes of Tricuspid Atresia in the Fontan Era. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2004, 77, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, P.; Fernandes, S.M.; Mayer, J.E.; Triedman, J.K.; Walsh, E.P.; Lock, J.E.; Landzberg, M.J. Long-Term Survival, Modes of Death, and Predictors of Mortality in Patients with Fontan Surgery. Circulation 2008, 117, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, C.; Hornung, T.; Celermajer, D.S.; Radford, D.J.; Justo, R.N.; Andrews, D.; du Plessis, K.; Iyengar, A.J.; Winlaw, D.; d’Udekem, Y. Modes of Late Mortality in Patients with a Fontan Circulation. Heart 2020, 106, 1427–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantine, A.; Ferrero, P.; Gribaudo, E.; Mitropoulou, P.; Krishnathasan, K.; Costola, G.; Lwin, M.T.; Fitzsimmons, S.; Brida, M.; Montanaro, C.; et al. Morbidity and Mortality in Adults with a Fontan Circulation beyond the Fourth Decade of Life. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2024, 31, 1316–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, C.-H.; Park, C.S.; Choi, E.S.; Ko, H.; An, H.S.; Kang, I.S.; Yoon, J.K.; Baek, J.S.; et al. The Long-Term Outcomes and Risk Factors of Complications After Fontan Surgery: From the Korean Fontan Registry (KFR). Korean Circ. J. 2024, 54, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaied, T.; Bokma, J.P.; Engel, M.E.; Kuijpers, J.M.; Hanke, S.P.; Zuhlke, L.; Zhang, B.; Veldtman, G.R. Predicting Long-Term Mortality after Fontan Procedures: A Risk Score Based on 6707 Patients from 28 Studies. Congenit Heart Dis 2017, 12, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafstedde, M.; Nordmeyer, S.; Schleiger, A.; Nordmeyer, J.; Berger, F.; Kramer, P.; Ovroutski, S. Persisting and Reoccurring Cyanosis after Fontan Operation Is Associated with Increased Late Mortality. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 61, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of TA | Frequency (%) | Pulmonary Flow | Aortic Blood Flow Pathway | Pulmonary Blood Flow Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I: Normally related great arteries (NRGA) | 70% | |||

| Ia: No VSD with PA | 10% | ↓ | LV → Ao | Ao → PDA/MAPCAs → PA |

| Ib: Restrictive VSD with PS | 50% | ↓ | LV → Ao | LV → VSD → RV → PA |

| Ic: Nonrestrictive VSD with no PS | 10% | ↔ | LV → Ao | LV → VSD → RV → PA |

| Type II: D-transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA) | 30% | |||

| IIa: Nonrestrictive VSD with PA | 2% | ↓ | LV → VSD → RV → Ao | Ao → PDA/MAPCAs → PA |

| IIb: Nonrestrictive VSD with PS | 8% | ↔ | LV → VSD → RV → Ao | LV → PA |

| IIc: Restrictive VSD with no PS | 20% | ↑ | LV → VSD → RV → Ao | LV → PA |

| Type III: Malposition of the great arteries other than D-TGA | <1% | |||

| IIIa: D-loop ventricles, L-TGA, subpulmonic stenosis | ↓ | LV → Ao | LV → VSD → RV → PA | |

| IIIb: L-loop ventricles, L-MGA, subaortic stenosis | ↑ | LV → VSD → RV → Ao | LV → PA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garrity, M.; Poppers, J.; Richman, D.; Bacon, J. Tricuspid Atresia and Fontan Circulation: Anatomy, Physiology, and Perioperative Considerations. Hearts 2025, 6, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/hearts6040030

Garrity M, Poppers J, Richman D, Bacon J. Tricuspid Atresia and Fontan Circulation: Anatomy, Physiology, and Perioperative Considerations. Hearts. 2025; 6(4):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/hearts6040030

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarrity, Madison, Jeremy Poppers, Deborah Richman, and Jonathan Bacon. 2025. "Tricuspid Atresia and Fontan Circulation: Anatomy, Physiology, and Perioperative Considerations" Hearts 6, no. 4: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/hearts6040030

APA StyleGarrity, M., Poppers, J., Richman, D., & Bacon, J. (2025). Tricuspid Atresia and Fontan Circulation: Anatomy, Physiology, and Perioperative Considerations. Hearts, 6(4), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/hearts6040030