Short-Term Mortality Trends in Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases Among Adults (45 and Older) in Mississippi, 2018–2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

2.2. Disease Classification and Mortality Rates

2.3. Trend Analysis Approach

2.4. Calculating APC and AAPC

2.4.1. Annual Percentage Change (APC)

2.4.2. Average Annual Percentage Change (AAPC)

3. Results

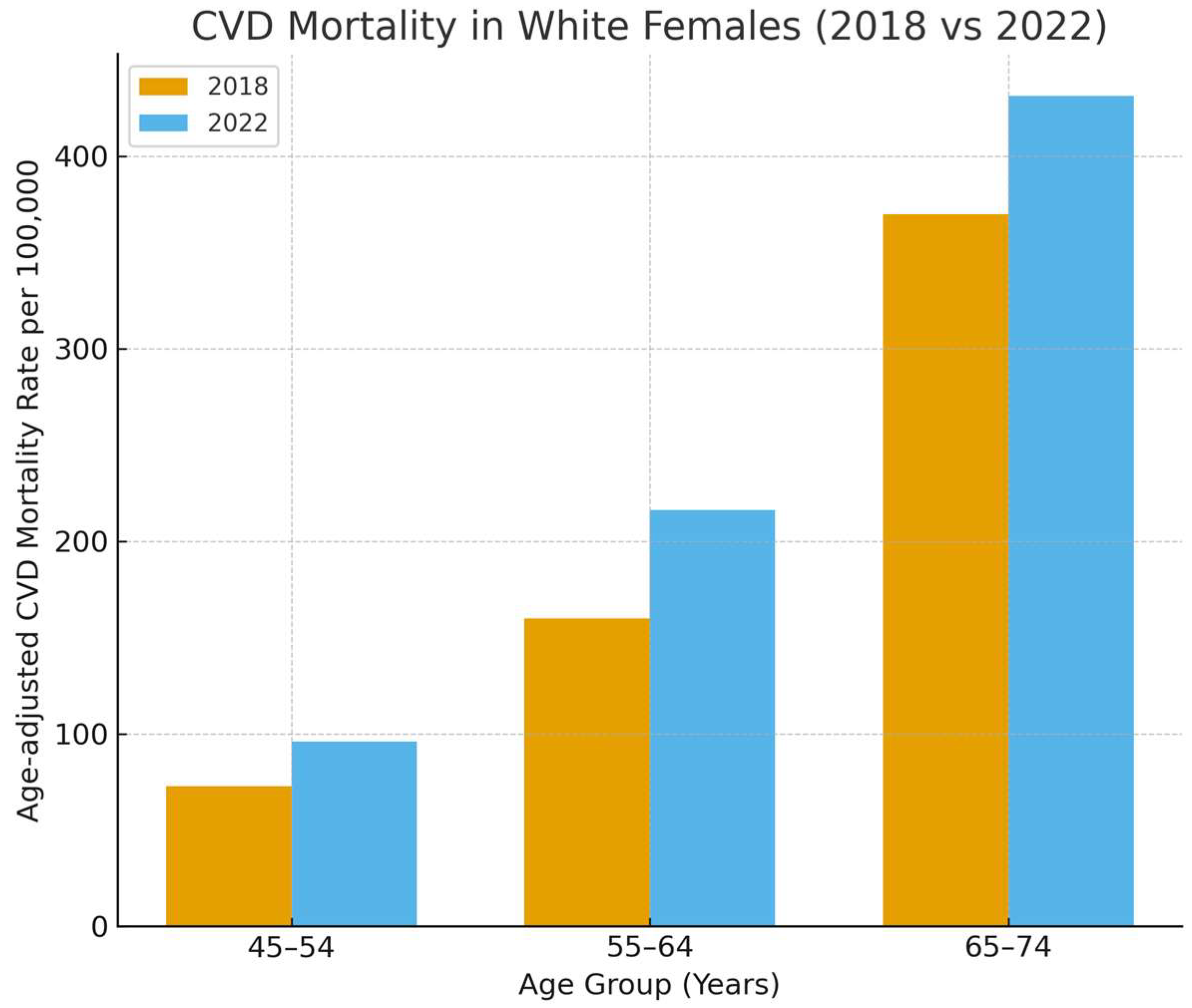

3.1. Cardiovascular Disease Mortality in Females

3.2. Cardiovascular Disease Mortality in Males

3.3. Cerebrovascular Disease Mortality in Females

3.4. Cerebrovascular Disease Mortality in Males

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FastStats. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Sidney, S.; Quesenberry, C.P., Jr.; Jaffe, M.G.; Sorel, M.; Nguyen-Huynh, M.N.; Kushi, L.H.; Go, A.S.; Rana, J.S. Recent Trends in Cardiovascular Mortality in the United States and Public Health Goals. JAMA Cardiol. 2016, 1, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Tong, X.; Schieb, L.; Vaughan, A.; Gillespie, C.; Wiltz, J.L.; King, S.C.; Odom, E.; Merritt, R.; Hong, Y.; et al. Vital Signs: Recent Trends in Stroke Death Rates—United States, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stats of the States—Heart Disease Mortality. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/heart_disease_mortality/heart_disease.htm (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Stats of the States—Stroke Mortality. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/stroke_mortality/stroke.htm (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Benjamin, E.J.; Muntner, P.; Alonso, A.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Das, S.R.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mississippi State Department of Health. Mississippi Behavioral Risk Factor Report; Mississippi State Department of Health: Jackson, MS, USA, 2023.

- Mendy, V.L.; Rowell-Cunsolo, T.; Bellerose, M.; Vargas, R.; Enkhmaa, B.; Zhang, L. Cardiovascular Disease Mortality in Mississippi, 2000–2018. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2022, 19, E09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhera, R.K.; Shen, C.; Gondi, S.; Chen, S.; Kazi, D.S.; Yeh, R.W. Cardiovascular Deaths During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mississippi State Department of Health. COVID-19 Provisional Mississippi Death Counts; Mississippi State Department of Health: Jackson, MS, USA, 2023; p. 19.

- CDC Heart Disease Facts. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/heart-disease/data-research/facts-stats/index.html (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Heart Disease Remains Leading Cause of Death as Key Health Risk Factors Continue to Rise. Available online: https://newsroom.heart.org/news/heart-disease-remains-leading-cause-of-death-as-key-health-risk-factors-continue-to-rise (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Wasfy, J.H.; Lin, Y.; Price, M.; Newhouse, J.P.; Blacker, D.; Hsu, J. Postpandemic Cardiac Mortality Rates. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2512919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obesity—Mississippi State Department of Health. Available online: https://msdh.ms.gov/page/43,0,289.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Office of Health Surveillance and Research; Office of Preventive Health and Health Equity. Hypertension Prevalence, Mississippi—2021; Mississippi State Department of Health: Jackson, MS, USA, 2023.

- Explore High Blood Pressure in Mississippi|AHR. Available online: https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/measures/Hypertension/MS (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Mississippi State Department of Health. Diabetes Among Adults in Mississippi: Analysis of 2022 Mississippi Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Data; Mississippi State Department of Health: Jackson, MS, USA, 2024. Available online: https://msdh.ms.gov/page/resources/20496.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Jain, V.; Minhas, A.M.K.; Morris, A.A.; Greene, S.J.; Pandey, A.; Khan, S.S.; Fonarow, G.C.; Mentz, R.J.; Butler, J.; Khan, M.S. Demographic and Regional Trends of Heart Failure–Related Mortality in Young Adults in the US, 1999-2019. JAMA Cardiol. 2022, 7, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heart Disease Risk Factors Rise in Young Adults|Harvard Medical School. Available online: https://hms.harvard.edu/news/heart-disease-risk-factors-rise-young-adults (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- More Adults in Rural America Are Dying from Cardiovascular Diseases. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/news/2024/11/15/more-adults-in-rural-america-are-dying-from-cardiovascular-diseases (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- CDC About Women and Heart Disease. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/heart-disease/about/women-and-heart-disease.html (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Emerging Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease in Women. Available online: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/996577 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Mississippi State Department of Health, Office of Health Data and Research. Annual Mississippi Health Disparities & Inequities Report; Mississippi State Department of Health: Jackson, MS, USA, 2023.

- McClure, E.S.; Gartner, D.R.; Bell, R.A.; Cruz, T.H.; Nocera, M.; Marshall, S.W.; Richardson, D.B. Challenges with Misclassification of American Indian/Alaska Native Race and Hispanic Ethnicity on Death Records in North Carolina Occupational Fatalities Surveillance. Front. Epidemiol. 2022, 2, 878309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age Group/Race | 2018 | 2022 | Average (2018–2022) | APC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | ||||

| 45–54 | 72.9 | 95.9 | 87.7 | 7.25 (0.32, 15.51) |

| 55–64 | 159.9 | 216.1 | 194.9 | 7.46 (2.85, 12.94) |

| 65–74 | 369.7 | 431.3 | 391.8 | 4.12 (1.23, 7.30) |

| 75–84 | 1016.47 | 1103.4 | 1093.9 | 2.65 (−0.48, 5.94) |

| 85+ | 4123.2 | 4283.1 | 4292.4 | 1.55 (−0.37, 3.49) |

| Black | ||||

| 45–54 | 117.7 | 142.0 | 139.4 | 4.49 (−7.20, 18.34) |

| 55–64 | 287.7 | 328.5 | 305.5 | 5.51 (−1.40, 13.88) |

| 65–74 | 510.5 | 572.5 | 543.4 | 3.53 (−2.05, 9.45) |

| 75–84 | 1152.3 | 1312.6 | 1250.6 | 4.43 (−5.08, 15.10) |

| 85+ | 3501.2 | 3471.5 | 3549.7 | 0.57 (−4.80, 6.39) |

| Other | ||||

| 55–64 | 115.8 | 67.2 | 91.1 | −0.21 (−32.92, 54.17) |

| 65–74 | 227.1 | 150.6 | 235.8 | −7.57 (−35.15, 21.59) |

| 75–84 | 793.7 | 368.1 | 437.3 | −21.95 (−42.22, −9.88) |

| 85+ | 1084.6 | 1040.1 | 1226.8 | 0.049 (−23.12, 30.17) |

| Age Group/Race | 2018 | 2022 | Average (2018–2022) | APC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | ||||

| 45–54 | 170.5 | 186.0 | 183.5 | 2.33 (−2.54, 7.62) |

| 55–64 | 369.1 | 458.7 | 435.6 | 5.59 (−1.19, 13.54) |

| 65–74 | 741.4 | 803.5 | 796.7 | 2.61 (−0.64, 6.00) |

| 75–84 | 1612.7 | 1896.3 | 1755.6 | −0.82 (−3.51, 1.81) |

| 85+ | 5488.1 | 5789.1 | 5450.9 | 1.90 (−4.34, 8.90) |

| Black | ||||

| 45–54 | 262.6 | 324.1 | 308.9 | 5.40 (−0.82, 12.27) |

| 55–64 | 542.7 | 649.8 | 616.9 | 6.03 (−5.50, 20.74) |

| 65–74 | 1019.7 | 1015.5 | 1077.2 | 2.04 (−11.63, 19.20) |

| 75–84 | 1903.3 | 1767.0 | 1846.5 | −0.82 (−3.51, 1.81) |

| 85+ | 3458.8 | 4300.7 | 4138.0 | 2.67 (−13.14, 20.89) |

| Other | ||||

| 45–54 | 96.6 | 221.9 | 143.1 | 18.14 (1.78, 43.97) |

| 55–64 | 330.0 | 346.7 | 280.9 | 2.25 (−23.50, 39.51) |

| 65–74 | 277.9 | 219.6 | 337.7 | 2.61 (−0.64, 6.00) |

| 75–84 | 747.1 | 979.6 | 703.4 | 7.96 (−19.31, 50.22) |

| 85+ | 344.8 | 735.3 | 1071.0 | 7.17 (−41.05, 120.08) |

| Age Group/Race | 2018 | 2022 | Average (2018–2022) | APC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | ||||

| 45–54 | 19.6 | 15.3 | 18.1 | −1.42 (−23.92, 29.33) |

| 55–64 | 39.4 | 45.4 | 40.7 | 5.72 (−6.52, 21.84) |

| 65–74 | 87.8 | 96.0 | 101.1 | 1.17 (−4.60, 7.34) |

| 75–84 | 318.3 | 350.5 | 326.6 | 3.19 (−1.15, 7.90) |

| 85+ | 1124.5 | 1014.8 | 1093.1 | −0.024 (−11.95, 14.02) |

| Black | ||||

| 45–54 | 35.2 | 46.4 | 43.3 | 7.90 (−7.64, 28.96) |

| 55–64 | 77.0 | 74.1 | 75.8 | 0.23 (−2.52, 2.98) |

| 65–74 | 146.2 | 168.1 | 168.2 | 3.67 (−2.71, 10.81) |

| 75–84 | 379.2 | 393.8 | 396.9 | 2.21 (−6.20, 12.03) |

| 85+ | 944.8 | 1079.8 | 1003.0 | 3.13 (−1.13, 7.64) |

| Other | ||||

| 65–74 | 189.3 | 60.2 | 67.4 | −30.93 (−72.34, 16.72) |

| 75–84 | 238.1 | 122.7 | 155.2 | −8.76 (−40.86, 32.66) |

| 85+ | 216.9 | 891.5 | 483.3 | 48.39 (22.00, 153.01) |

| Age Group/Race | 2018 | 2022 | Average (2018–2022) | APC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | ||||

| 45–54 | 22.9 | 27.8 | 23.8 | 6.00 (−2.47, 16.29) |

| 55–64 | 62.1 | 60.4 | 57.4 | 1.75 (−7.66, 12.81) |

| 65–74 | 119.7 | 125.3 | 124.3 | −2.12 (−11.42, 7.11) |

| 75–84 | 303.9 | 329.8 | 350.5 | 1.40 (−14.39, 20.34) |

| 85+ | 923.6 | 995.5 | 929.2 | 2.61 (−2.16, 7.83) |

| Black | ||||

| 45–54 | 71.9 | 42.9 | 57.9 | −4.46 (−26.53, 24.34) |

| 55–64 | 151.0 | 143.3 | 152.7 | 0.61 (−8.03, 9.94) |

| 75–84 | 487.6 | 490.1 | 532.0 | 3.17 (−10.32, 19.50) |

| 85+ | 608.7 | 1082.9 | 996.6 | 8.80 (−19.00, 51.97) |

| Other | ||||

| 55–64 | 27.5 | 99.1 | 52.0 | 30.00 (8.00, 85.66) |

| 75–84 | 320.2 | 244.9 | 228.1 | −6.67 (−20.95, 6.46) |

| 85+ | 344.8 | 245.1 | 563.7 | 8.90 (−36.52, 109.91) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elhendawy, A.; Jones, E. Short-Term Mortality Trends in Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases Among Adults (45 and Older) in Mississippi, 2018–2022. Hearts 2025, 6, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/hearts6040031

Elhendawy A, Jones E. Short-Term Mortality Trends in Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases Among Adults (45 and Older) in Mississippi, 2018–2022. Hearts. 2025; 6(4):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/hearts6040031

Chicago/Turabian StyleElhendawy, Ahmed, and Elizabeth Jones. 2025. "Short-Term Mortality Trends in Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases Among Adults (45 and Older) in Mississippi, 2018–2022" Hearts 6, no. 4: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/hearts6040031

APA StyleElhendawy, A., & Jones, E. (2025). Short-Term Mortality Trends in Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases Among Adults (45 and Older) in Mississippi, 2018–2022. Hearts, 6(4), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/hearts6040031