Abstract

Background: As the surgical repertoire for the management of sinonasal tumors evolves over time, an improved understanding of risks for postoperative complications is imperative. Objectives: To identify factors associated with 30-day postoperative complications following the resection of sinonasal tumors. Methods: The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database was queried from 2005 to 2020 for patients undergoing open or endoscopic surgical resection of sinonasal tumors. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify factors associated with postoperative complications. Kaplan–Meier survival analyses and log-rank tests were used to compare time to complication onset. Frailty was defined as a 5-factor modified frailty index score > 2. Results: Of the 859 patients with sinonasal tumors, 539 (62.7%) were male, and the average age (± SD) was 59.3 ± 14.1 years. Postoperative complications were observed in 251 (29.2%) patients. The most common 30-day complications were bleeding requiring transfusions (n = 172; 20.0%) and ventilation longer than 48 h (n = 37; 4.3%). Frailty (aHR [95% CI]: 3.58 [1.80–7.12]), malignancy (3.43 [1.59–7.38]), and maxillary tumor location (2.40 [1.86–3.09]) were associated with greater risk for 30-day postoperative complications. Similarly, patients with frailty (χ2 = 7.0; p = 0.008), malignant tumors (χ2 = 13.4; p < 0.001), or maxillary sinus tumors (χ2 = 34.6; p < 0.001) experienced earlier onset of postoperative complications. Conclusions: Frailty, malignancy status, and tumor location may modulate risk for 30-day postoperative complications following the resection of sinonasal tumors. These results may help to inform preoperative patient counseling and identify individuals at increased risk of postoperative complications.

1. Introduction

Sinonasal tumors are a relatively uncommon clinical entity, with the malignant variety of sinonasal tumors representing an estimated 5% of head and neck tumors [1]. Because of their unique anatomic location, their proximity to critical neurovascular structures, and the function of the sinonasal tract, sinonasal neoplasms may result in significant morbidity and quality of life impairments [2,3]. Sinonasal tumors commonly present with local symptoms including nasal obstruction, epistaxis, discharge, hyposmia, and visual changes, and are associated with emotional distress and a mental health burden both as a consequence of their disease and treatment [1,2,3].

The primary management of many sinonasal tumors is surgical in nature, with increasing utilization of endoscopic approaches, irrespective of malignancy status. While serious complications following the resection of sinonasal tumors are rare, the proximity of the sinuses to the brain, orbit, and critical neurovascular structures presents inherent surgical risk. Complications following the resection of sinonasal tumors may include acute bleeding, sinonasal perturbations such as nasal obstruction, surgical site infection, crusting and anosmia, ophthalmologic impairments such as visual loss or epiphora, and intracranial complications such as pneumocephalus, cerebrovascular accident, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, and meningitis [4,5]. Furthermore, odontogenic considerations may not only impact the diagnosis of sinus tumors but also the risk and presentation of postoperative surgical complications [6].

In the setting of a shifting landscape of sinonasal tumor management characterized by an increasing emphasis on endoscopic surgical techniques and improvements in sinonasal tumor detection [7,8], the risk factors for postoperative complications following the resection of sinonasal tumors are presently not well-characterized in the literature. Additionally, in the setting of an increasingly aged and frail population that is projected to double over the next thirty years [9], new challenges will emerge for clinicians providing care for a growing patient population susceptible to disease and iatrogenic complications [10,11,12,13]. An improved understanding of risks for complications is imperative to inform preoperative patient counseling and improve postoperative outcomes. In this study, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database was used to identify factors associated with 30-day postoperative complications following resection of sinonasal tumors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

The ACS NSQIP database was queried for all patients who underwent resection of sinonasal tumors between 2005 and 2020. Patients with primary sinonasal tumors undergoing resection of sinonasal tumors were identified using the ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes provided in Supplementary Table S1. Patients with metastatic cancer of unknown primary or other sinonasal pathologies were excluded from this study.

2.2. Study Population and Variables

Age at time of surgery, sex, and race/ethnicity were collected for each patient. Patient, perioperative, and intraoperative characteristics that were collected included ASA class, surgical wound class, resection approach (surgical vs. endoscopic), malignancy status, and tumor location. The malignancy status, procedural approach, and location of tumors were identified using ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic and CPT codes (Supplementary Table S1). Frailty status was assessed using the 5-factor modified frailty index (mFI-5), which has been validated for use with the ACS NSQIP database [14]. Frailty was defined categorically as an mFI-5 > 2, thus requiring frail patients to have more than half of the factors included in the mFI-5.

2.3. Outcome Measures

Perioperative outcomes included the total operation time, days from operation to discharge, and the total duration of hospital stay. Postoperative complications that were noted included life-threatening and overall complications. Life-threatening complications were those defined by the Clavien–Dindo classification system as indicative of major systemic dysfunction, and included cerebrovascular accident (CVA), unplanned reintubation, mechanical ventilation for more than 48 h, acute renal failure, cardiac arrest, pulmonary embolism, and myocardial infarction. Overall complications included bleeding requiring transfusions within 72 h of the surgical start-time, readmission, deep vein thrombosis/thrombophlebitis, unplanned reoperation, mortality, superficial incisional or deep incisional surgical site infection, and life-threatening complications. The number of days to the first overall complication was additionally collected.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Patients were separated into a “Complications” or “No Complications” group based upon whether or not they experienced any overall 30-day complication postoperatively. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and proportions and compared using chi-squared tests. Continuous variables were reported as the mean and standard deviation (SD) and compared using Student’s t-tests. Variables significant in preliminary group comparisons were further assessed using logistic regressions, with the presence of any postoperative complication as the outcome variable. Variables associated with an increased risk for overall complications were identified using a Cox proportional hazards model. The duration of time from operation to postoperative complication was plotted using Kaplan–Meier non-parametric survival analyses, and statistical significance was assessed using the log-rank test. Significance for preliminary group comparisons was defined as p < 0.05. A Dunn–Sidak correction was applied for univariable regressions due to multiple comparisons, and significance was defined as p < 0.005. A conservative Bonferroni correction was applied for multivariable regressions. Significance was defined as p < 0.01 for the multivariable logistic regression and defined as p < 0.02 for the multivariable linear regression and Cox proportional hazards model. Effect sizes for continuous variables and categorical variables were calculated using Cohen’s d coefficients and odds ratios, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Sinonasal Tumors

Of the 859 patients who underwent resection for sinonasal tumors, 251 (29.2%) patients experienced at least one postoperative complication. The majority of sinonasal tumors in the overall cohort were malignant (n = 761; 88.6%), and most patients underwent an open-surgical approach (n = 754; 87.8%). The average age of the overall cohort was 59.3 ± 14.1 years, and the majority (n = 539; 62.7%) were male. Demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and smoking history did not significantly differ between the two groups, although patients who experienced postoperative complications had a lower BMI (t = 3.2; d = 0.22; p = 0.001) and were less likely to have hypertension (χ2 = 4.2; OR [95% CI]: 0.73 [0.54–0.98]; p = 0.04) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and clinical characteristics of patients who underwent resection of sinonasal tumors with and without postoperative complications.

An mFI-5 score greater than or equal to 3 was significantly more likely among patients who experienced postoperative complications (χ2 = 6.7; OR [95% CI]: 0.61 [0.44–0.84]; p = 0.01). Patients who experienced postoperative complications were significantly more likely to have malignant tumors (χ2 = 26.1; OR [95% CI]: 6.14 [2.86–13.56]; p < 0.001), as well as to have tumors present in the nasal cavity (χ2 = 20.5; OR [95% CI]: 0.47 [0.34–0.65]; p < 0.001) or maxillary sinus (χ2 = 66.2; OR [95% CI]: 3.49 [2.57–4.72]; p < 0.001) subsites. A greater proportion of patients who experienced postoperative bleeding requiring transfusions presented with a maxillary sinus tumor subsite compared to patients who did not experience bleeding requiring transfusions (χ2 = 59.1; OR [95% CI]: 3.71 [2.61–5.28]; p < 0.001). An open-surgical approach was more common among patients with maxillary tumors compared to patients with tumors in other locations (χ2 = 9.7; OR [95% CI]: 2.18 [1.33–5.55]; p = 0.002). In the overall cohort, the resection approach (i.e., open-surgical versus endoscopic) did not significantly differ between the two groups (χ2 = 0.28; OR [95% CI]: 1.13 [0.73–1.74]; p = 0.60) (Table 1).

3.2. Perioperative Characteristics and Postoperative Complications

The total operation time for patients who experienced postoperative complications was significantly longer than for patients who did not have complications (t = 15.0; d = 1.02; p < 0.001). Additionally, the length of total hospital stay (t = 10.7; d = 0.73; p < 0.001) and the number of days from operation to discharge (t = 11.0; d = 0.75; p < 0.001) were significantly greater for patients who experienced complications. Among patients who experienced complications, the average number of complications was 1.3 ± 0.7, and the most common complications included bleeding requiring transfusions (n = 172; 68.5%), ventilation greater than 48 h (n = 37; 14.7%), any readmission (n = 50; 19.9%), and superficial incisional surgical site infection (n = 30; 12.0%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perioperative characteristics and postoperative complications for patients who underwent resection of sinonasal tumors.

3.3. Univariable Regressions Identifying Factors Associated with Postoperative Complications

Variables that were significant in preliminary group comparisons were assessed using univariable logistic regressions, with the presence of any postoperative complication as the outcome variable. In these univariable analyses, patients with a higher BMI (OR [95% CI]: 0.97 [0.94, 0.99]); p = 0.003) or nasal cavity subsite tumors (0.47 [0.34–0.65]); p < 0.001), which includes septal tumors, were significantly less likely to experience postoperative complications. Conversely, frailty (5.6 [1.71, 18.34]; p < 0.001), high ASA class (1.65 [1.28, 2.14]; p < 0.001), malignancy (6.16 [2.81, 13.49]; p < 0.001), and a maxillary sinus tumor subsite (3.51 [2.58, 4.78]; p < 0.001) were significantly associated with complications following resection of sinonasal tumors (Table 3). To investigate factors associated with postoperative bleeding requiring transfusions, additional univariable logistic regressions were performed and demonstrated a significant association with maxillary tumor location (3.71 [2.64, 5.26]; p < 0.001). Additionally, using univariable logistic regression, patients with a maxillary sinus tumor subsite were significantly less likely to undergo an endoscopic approach (0.46 [0.28, 0.76]; p = 0.002).

Table 3.

Logistic regressions identifying patient and clinical characteristics significantly associated with postoperative complications following resection of sinonasal tumors.

Using univariable linear regressions, a nasal cavity tumor subsite (β [95% CI]: −0.19 [−0.29, −0.09]; p < 0.001) was significantly associated with fewer postoperative complications. In contrast, high ASA class (0.15 [0.07, 0.23]; p < 0.001), malignancy (0.35 [0.20, 0.49]; p < 0.001), and a maxillary sinus tumor subsite (0.35 [0.26, 0.45]; p < 0.001) were predictive of a greater number of postoperative complications (Table 4).

Table 4.

Linear regressions identifying patient and clinical characteristics significantly associated with the total number of post-operative complications following resection of sinonasal tumors.

3.4. Multivariable Regressions Identifying Factors Associated with Postoperative Complications

Variables significant in univariable analyses were further assessed using multivariable regressions. Using a multivariable logistic regression, frailty (aOR [95% CI]: 5.23 [1.48, 18.50]; p = 0.009), malignancy (3.39 [1.51, 7.62]; p < 0.001) and a maxillary sinus tumor subsite (2.78 [2.02, 3.84]; p < 0.001) were significantly associated with the presence of 30-day postoperative complications (Table 3). Meanwhile, using multivariable linear regression, malignant tumors (β [95% CI]: 0.20 (0.05, 0.35); p = 0.01) and a maxillary sinus tumor subsite (0.29 (0.19, 0.39); p < 0.001) were significantly associated with a greater total number of 30-day postoperative complications (Table 4).

3.5. Relationship Between Frailty, Malignancy, and Tumor Location and Time to Overall Complication

A Cox proportional hazards model, adjusted for age, sex, and BMI, was used to assess the relationship between frailty, malignancy, and a maxillary sinus tumor subsite and the risk for postoperative complications. In this adjusted analysis, frail patients (aHR [95% CI]: 3.58 [1.80, 7.12]; p < 0.001) and patients with malignant tumors (3.43 [1.59, 7.38]; p = 0.002) were at greater than three times risk for overall postoperative complications. Additionally, a maxillary sinus tumor subsite (2.40 [1.86, 3.09]; p < 0.001) was also associated with an increased risk for postoperative complications (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazards regression assessing the relationship between frailty status, malignancy, and maxillary tumor location with risk for postoperative complications following resection of sinonasal tumors.

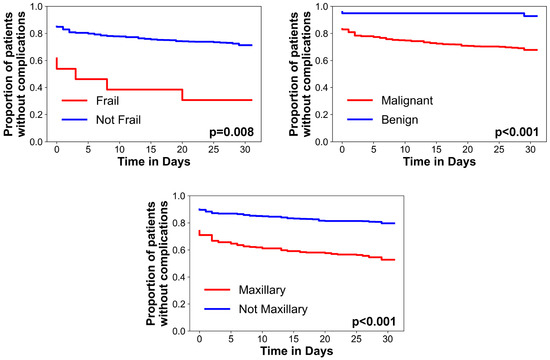

Kaplan–Meier survival analyses and log-rank tests were used to compare the time to first overall complication between frail versus non-frail patients, malignant versus benign tumors, and maxillary versus non-maxillary sinus tumor subsites. Frail patients (χ2 = 7.0; p = 0.008), patients with malignant tumors (χ2 = 13.4; p < 0.001), and patients with maxillary sinus tumor subsites (χ2 = 34.6; p < 0.001) experienced earlier onset of postoperative complications compared to their respective counterparts in the first 30-day postoperative period (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves assessing the relationships between frailty, malignancy, and maxillary tumor location with postoperative complications. A log-rank test was used to assess significance.

4. Discussion

As the emphasis on endoscopic surgical techniques, improvements in sinonasal tumor detection, and the population of older and more frail adults continue to expand, an improved understanding of risks for complications is imperative to inform preoperative patient counseling and improve postoperative outcomes in sinonasal tumor resection. In this study, we found that nearly one-third of patients experienced postoperative complications with an increase in the setting of frailty, malignancy, and maxillary tumor subsite. As sinonasal tumors are associated with high emotional distress and mental health burden both as a consequence of their disease and treatment, understanding factors that mitigate treatment-related complications is of utmost importance [1,2,3].

Frailty is increasingly recognized as a significant predictor of adverse events following surgery across many different surgical specialties. Among otolaryngologic operations, frailty has been shown to increase the risk for postoperative complications and/or mortality following inpatient head and neck surgeries by more than ten-fold [15]. In a 2016 study by Abt et al. investigating postoperative outcomes in 1193 head and neck oncologic operations, increasing degrees of frailty as quantified by the mFI-5 were significantly associated with greater risk for Clavien–Dindo grade IV complications, and were found to be a stronger overall predictor of complications compared to age, sex, BMI, and ASA class [16]. Furthermore, in a 2019 study by Goel et al. of 5346 patients from the Nationwide Readmissions Database, frail patients exhibited greater healthcare resource utilization following resection of sinonasal malignancies, including a longer total hospital stay and higher hospital costs [17]. The results of our study corroborate these findings and add to a growing understanding that in the setting of an increasingly aged population, preoperative frailty assessment may mitigate postoperative complications and their resultant morbidities.

Albeit intuitive, we additionally found in this study that positive malignancy status not only increases the risk for 30-day postoperative complications following resection of sinonasal tumors but is also associated with earlier onset of complications. Although few studies in the literature have compared the incidence of postoperative complications between benign versus malignant tumors, advanced T stage and N stage have been shown to increase the risk for postoperative complications among patients with sinonasal malignancies [4,18]. We additionally show that the subsite of sinonasal tumors, not merely malignancy status, may modulate the risk for postoperative complications. In particular, a maxillary sinus tumor location was associated with earlier onset of postoperative complications, with greater than two-fold increased risk for complications compared to tumors found in other locations. The precise mechanism underlying this relationship is difficult to rationalize, but may involve the proximity and angled course of the internal maxillary artery and its associated branches, such as the sphenopalatine artery. Indeed, a significantly greater proportion of patients who experienced bleeding requiring transfusions presented with maxillary sinus tumors. The operative approach for the management of maxillary tumors may also help to rationalize the increased risk for postoperative complications associated with a maxillary sinus tumor location. In our study, a greater proportion of patients with maxillary tumors underwent open-surgical resection compared to patients with tumors in other locations. Although the operative approach was not found to be predictive of postoperative complications in the overall patient cohort, these sub-analyses may suggest that from the perspective of mitigating postoperative complications, the management of maxillary sinus tumors may benefit from preoperative prophylactic measures, such as preoperative embolization or ligation of the relevant vascular structures.

Although not significant in multivariable analyses when assessed at a Bonferroni-corrected threshold, a higher BMI was found to be protective against 30-day postoperative complications in univariable analyses. These results align with a growing understanding of the obesity paradox, whereby patients with higher BMIs have been shown to exhibit relative protection against adverse outcomes across many different medical and surgical domains [19,20,21,22]. Indeed, in a 2021 study by Wardlow et al. that used the NSQIP database from 2006 to 2018, obesity was found to be significantly associated with decreased odds for any surgical complication, perioperative bleeding, and any adverse postoperative event. The physiological mechanism underpinning this relationship is poorly understood but may implicate altered intracellular signaling pathways among patients with excessive adipose tissue [19,20,21]. Additionally, obese patients may possess greater nutritional reserves, enabling them to mount more robust immunologic responses [23]. Future studies more closely elucidating the obesity paradox should be performed as the relationship between obesity and postoperative complications is likely multifactorial, and whether or not this relationship holds for other otolaryngologic procedures should be investigated.

Limitations

Our study was subject to several limitations inherent in the use of the ACS NSQIP database. First, as data were culled from NSQIP participant institutions, the results of our study may not be nationally representative. Second, as the NSQIP database does not collect postoperative complications beyond 30 days, postoperative complications that may present on a more long-term scale could not be assessed. Additionally, as endoscopic resection was relatively rare in our cohort, conclusions regarding complications attributable to an endoscopic approach are limited, and future studies with a larger endoscopic cohort should be performed. The limited number of endoscopic cases is likely a function of discrepancies and difficulty in retrospectively identifying endoscopic procedures via ICD and CPT codes, rather than a true dearth of endoscopic approaches during this time period. Finally, variables regarding surgical experience or oncologic characteristics—such as tumor staging or pathologic/histologic subtypes—and sinus- or skull-base-specific complications—such as orbital or intracranial complications—are not collected in the NSQIP database, and thereby could not be assessed.

5. Conclusions

Frailty, malignancy, and a maxillary sinus tumor subsite are associated with a greater number of, increased risk for, and earlier onset of 30-day postoperative complications. The results of this study may help inform preoperative patient counseling and identify patients most at risk for postoperative complications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sinusitis9010008/s1, Table S1: ICD and CPT Codes Identifying Sinonasal Tumors.

Author Contributions

R.J.S.: Study design, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing; H.A.Q.: Study design, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing; E.M.L.: Study design, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing; A.S.: Study design, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing; M.R.J.: Study design, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing; N.R.L.J.: Study design, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing; N.R.R.: Study design, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

N. R. R. was supported by the Johns Hopkins University Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, funded by the National Institute on Aging and National Institutes of Health (P30AG021334).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval from the Institutional Review Board was not required, as this study used data from a publicly available national database.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available at https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/data-and-registries/acs-nsqip/.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest associated with this study.

References

- Harvey, R.J.; Dalgorf, D.M. Sinonasal Malignancies. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2013, 27 (Suppl. S3), S35–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhenswala, P.N.; Schlosser, R.J.; Nguyen, S.A.; Munawar, S.; Rowan, N.R. Sinonasal quality-of-life outcomes after endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019, 9, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, R.; Agarwal, A.; Chitguppi, C.; Swendseid, B.; Graf, A.; Murphy, K.; Jangro, W.; Rhodes, L.; Toskala, E.; Luginbuhl, A.; et al. Quality of Life Outcomes in Patients With Sinonasal Malignancy After Definitive Treatment. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, E2212–E2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodhia, S.; Fitzgerald, C.W.R.; McLean, A.T.; Yuan, A.; Mayor, C.V.; Adilbay, D.; Mimica, X.; Gupta, P.; Cracchiolo, J.R.; Patel, S.; et al. Predictors of surgical complications in patients with sinonasal malignancy. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 124, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatelet, F.; Simon, F.; Bedarida, V.; Le Clerc, N.; Adle-Biassette, H.; Manivet, P.; Herman, P.; Verillaud, B. Surgical Management of Sinonasal Cancers: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, N.; Dorado, C.B.; Brinkmann, J.C.-B.; Ares, M.M.; Alonso, J.S.; Martínez-González, J.M. Dental considerations in diagnosis of maxillary sinus carcinoma A patient series of 24 cases. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2018, 149, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, M.; Orlandi, E.; Bossi, P. Sinonasal cancers treatments: State of the art. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2021, 33, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, G.; Likosky, D.S.; Zhou, W.; Finlayson, S.R.G.; Goodman, D.C. Trends in endoscopic sinus surgery rates in the Medicare population. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2010, 136, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, P.; Goodkind, D.; He, W. An Aging World: 2015, International Population Reports; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington DC, USA, 2016; p. 95.

- Hoogendijk, E.O.; Afilalo, J.; Ensrud, K.E.; Kowal, P.; Onder, G.; Fried, L.P. Frailty: Implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet 2019, 394, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Dan, X.; Babbar, M.; Wei, Y.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudge, A.M.; McRae, P.; Hubbard, R.E.; Peel, N.M.; Lim, W.K.; Barnett, A.G.; Inouye, S.K. Hospital-Associated Complications of Older People: A Proposed Multicomponent Outcome for Acute Care. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permpongkosol, S. Iatrogenic disease in the elderly: Risk factors, consequences, and prevention. Clin. Interv. Aging 2011, 6, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniam, S.; Aalberg, J.J.; Soriano, R.P.; Divino, C.M. New 5-Factor Modified Frailty Index Using American College of Surgeons NSQIP Data. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2018, 226, 173–181.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, P.; Ghanem, T.; Stachler, R.; Hall, F.; Velanovich, V.; Rubinfeld, I. Frailty as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in inpatient head and neck surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013, 139, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abt, N.B.; Richmon, J.D.; Koch, W.M.; Eisele, D.W.; Agrawal, N. Assessment of the Predictive Value of the Modified Frailty Index for Clavien-Dindo Grade IV Critical Care Complications in Major Head and Neck Cancer Operations. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 142, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.N.; Lee, J.T.; Gurrola, J.G.; Wang, M.B.; Suh, J.D. The impact of frailty on perioperative outcomes and resource utilization in sinonasal cancer surgery. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilbay, D.; Valero, C.; Fitzgerald, C.; Yuan, A.; Mimica, X.; Gupta, P.; Wong, R.J.; Shah, J.P.; Patel, S.G.; Ganly, I.; et al. Outcomes in surgical management of sinonasal malignancy—A single comprehensive cancer center experience. Head Neck 2022, 44, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, D.L.; Xenos, E.S.; Hosokawa, P.; Radford, J.; Henderson, W.G.; Endean, E.D. The influence of body mass index obesity status on vascular surgery 30-day morbidity and mortality. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 49, 140–147.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, C.J.; Milani, R.V.; Ventura, H.O.; Romero-Corral, A. Body composition and heart failure prevalence and prognosis: Getting to the fat of the matter in the “obesity paradox”. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2010, 85, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippen, M.M.; Brady, J.S.; Mozeika, A.M.; Eloy, J.A.; Baredes, S.; Park, R.C.W. Impact of Body Mass Index on Operative Outcomes in Head and Neck Free Flap Surgery. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 159, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardlow, R.D.; Bernstein, I.A.; Orlov, C.P.; Rowan, N.R. Implications of Obesity on Endoscopic Sinus Surgery Postoperative Complications: An Analysis of the NSQIP Database. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 164, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, J.T.; Moorman, D.W.; Davenport, D.L. The obesity paradox: Body mass index and outcomes in patients undergoing nonbariatric general surgery. Ann. Surg. 2009, 250, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).