1. Introduction

The paranasal sinuses are air-filled spaces in the frontal, ethmoid, and sphenoid bones and maxilla. Their evolutionary role is not entirely clear, but they probably play an important role in conditioning air for the lower respiratory tract by humidifying and warming it, acting as a buffer for rapid outer temperature changes (i.e., maintaining a stable head temperature), acting as protection for the brain in head trauma, reducing head weight, and increasing the resonance of speech [

1].

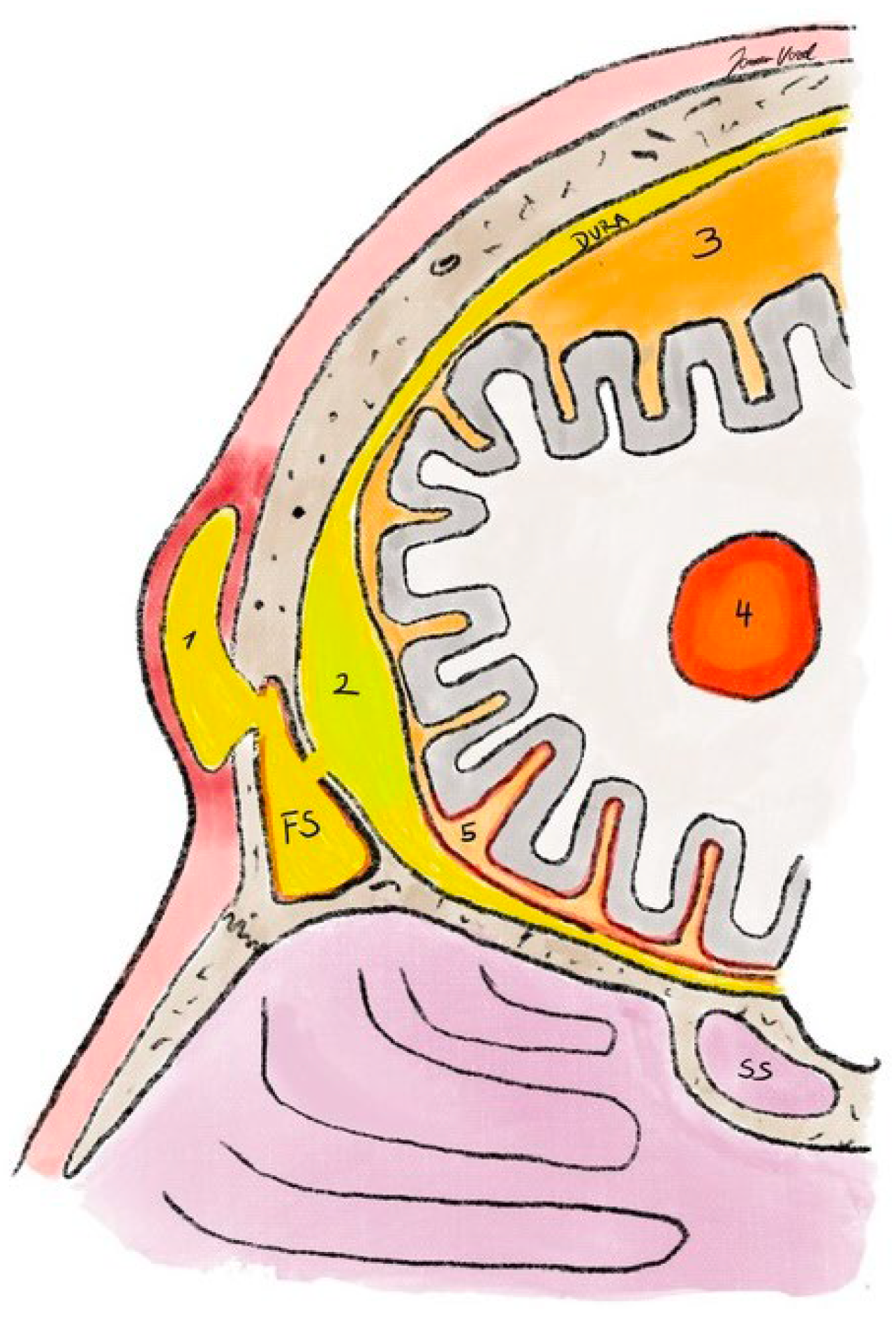

They are in proximity to the nasal cavity, the oral cavity, the orbit, the skull base, the brain, and important neurovascular structures, including the eye bulb, the optic nerve, the internal carotid artery, the pituitary gland, the maxillary nerve, the Vidian nerve (

nervus canalis pterygoidei), and the cavernous sinus. These anatomical features are beneficial for transnasal orbital and skull base surgery but also pose a risk for the progression of infections to these delicate areas (

Figure 1).

The relationship of the paranasal sinuses with these structures depends on the degree of pneumatization of the paranasal sinuses. The temporal course of pneumatization varies between the paranasal sinuses; therefore, the localization of inflammation depends mainly on the age of the patient. In the population of preschool children, infections of the ethmoid sinuses predominate, but, with growth, infections of the maxillary sinus, the frontal sinus, and the sphenoid sinus also occur. The localization of sinusitis therefore determines the type of complication.

On average, children experience seven and adults three episodes of acute rhinosinusitis (ARS or the common cold) annually, such that, regardless of age, each individual experiences an average of five episodes per year. Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis develops in 1.3% of ARS in adults and in 8% of ARS in children (i.e., about 5% on average) [

2]. In children, complications develop in 1 in 12,000 and in adults in 1 in 32,000 episodes of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis [

3].

Moreover, due to the high prevalence of sinusitis in the pediatric and adult population, knowledge of sinusitis and its complications is important for physicians from primary to tertiary healthcare levels, including pediatricians, family physicians, emergency physicians, otorhinolaryngologists, neurologists, neurosurgeons, ophthalmologists, neuroradiologists, and infectious disease specialists.

2. Classification of Inflammation in the Sinonasal Region

In the sinonasal area, we speak of a unified airway, and acute rhinitis is often not distinguished from sinusitis, as they occur at the same time. For this reason, otorhinolaryngologists mostly refer to inflammation of the sinonasal areas as rhinosinusitis. If the symptoms and signs of inflammation of the nasal mucosa predominate, we may first speak of rhinitis. Chronic allergic rhinitis is a typical representative, which, as a rule, does not cause complications and symptomatology in the paranasal sinuses. In the case of a predominance of inflammation in one paranasal sinus, we speak of sinusitis, although inflammation is usually also present in the nose and adjacent paranasal sinuses, e.g., in maxillary sinusitis, inflammation is also present in the anterior ethmoid cells [

4].

Depending on the causative agent, there are non-infectious and infectious inflammations. The latter are divided into viral, bacterial, and fungal. Viral is most commonly called the common cold or ARS and does not directly cause complications. The opposite is true for bacterial and fungal ones, where the chance of complications is significantly higher. Non-infectious inflammation includes a large group of inflammations ranging from primary (e.g., chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis) to secondary rhinosinusitis (e.g., cystic fibrosis, maxillary sinus aspergilloma, granulomatosis with polyangiitis) [

4].

3. Diagnostic Criteria for Rhinitis, Rhinosinusitis, and Sinusitis

There are no separate diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, and sinusitis, considering the unified airway and the clinical diversity of pathology.

At the primary level, the patient’s description of the problem (i.e., symptoms) without clinical signs is sufficient to make the diagnosis. Most acute rhinosinusitis is self-limiting, meets the criteria below but does not require specific treatment or referral, and is usually without complications [

4]. However, the otorhinolaryngologist should also consider the clinical status based on endoscopy and/or imaging to diagnose rhinosinusitis [

4] (

Figure 2).

To diagnose acute bacterial (rhino)sinusitis (ABRS), at least three of the following must be present in addition to meeting the above criteria for acute sinusitis [

4]:

Uniform diagnostic criteria allow for the recognition or confirmation of disease, but they cannot determine the duration, extent, or prognosis of the disease. Acute rhinosinusitis in the form of the common cold, which does not require a visit to the doctor, or chronic rhinosinusitis, which has a completely different etiology and requires a slightly modified diagnostic and therapeutic approach, may meet these criteria.

In contrast, the criteria for recognizing the complications of rhinosinusitis are very clear, and they are presented in the section on the clinical picture and recognition of complications.

4. Pathophysiology of Sinusitis Complications

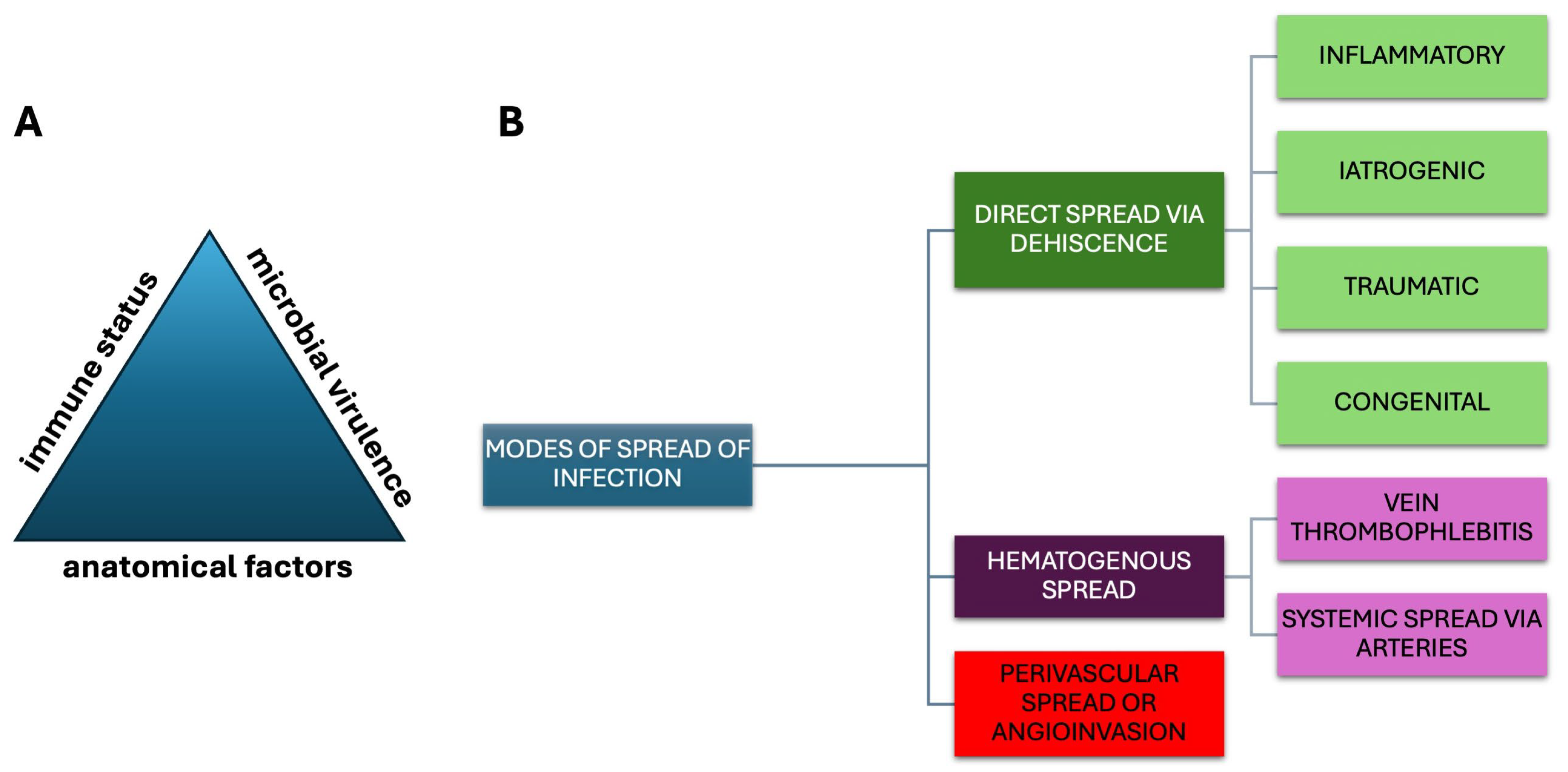

The complications of sinusitis depend on the immune status, the anatomical conditions of the patient, and the virulence of the microbe. Typically, viral infection (cold or ARS) is the first to occur, causing impairment of mucociliary transport and the epithelial barrier. This is followed by bacterial superinfection, causing ABRS. In the case of fungal colonization of the nasal and paranasal cavities or a pre-existing non-invasive fungal infection (e.g., paranasal sinus aspergilloma), invasive fungal infection, i.e., invasive fungal rhinosinusitis, may develop in the case of immunodeficiency [

5].

When the infection of the paranasal sinus extends beyond the anatomical boundaries of the sinonasal area into adjacent (e.g., orbit, facial bones, skull base, intracranial space) or distant anatomical areas (i.e., into the blood), we speak of a sinusitis complication. Modes of spread of infection are depicted in

Figure 3.

5. Classification of Sinusitis Complications

Traditionally, the complications of sinusitis are divided into orbital, bony, and intracranial. However, there are other complications that cannot be classified into any of these groups, and it can be more appropriate to divide the complications into intracranial and extracranial complications and subgroups of the latter (

Table 1). Extracranial complications occur more frequently than intracranial complications. Of the extracranial complications, orbital complications are the most common [

6].

6. Clinical Presentation of Sinusitis Complications

The complications of sinusitis usually follow problems related to acute or chronic inflammation of the nose and the sinuses extending beyond the paranasal sinuses, so a patient or physician should recognize ten alarming symptoms and signs:

Swelling or redness in the orbital area;

Globe malposition/protrusion/strabismus;

Diplopia;

Ophthalmoplegia;

Reduced visual acuity;

Severe headache;

Swelling of the forehead;

Signs or symptoms of sepsis;

Signs or symptoms of meningitis;

Signs or symptoms of neurological impairment.

In the presence of the above-mentioned alarm signs or symptoms, urgent referral for further hospital treatment is required [

4].

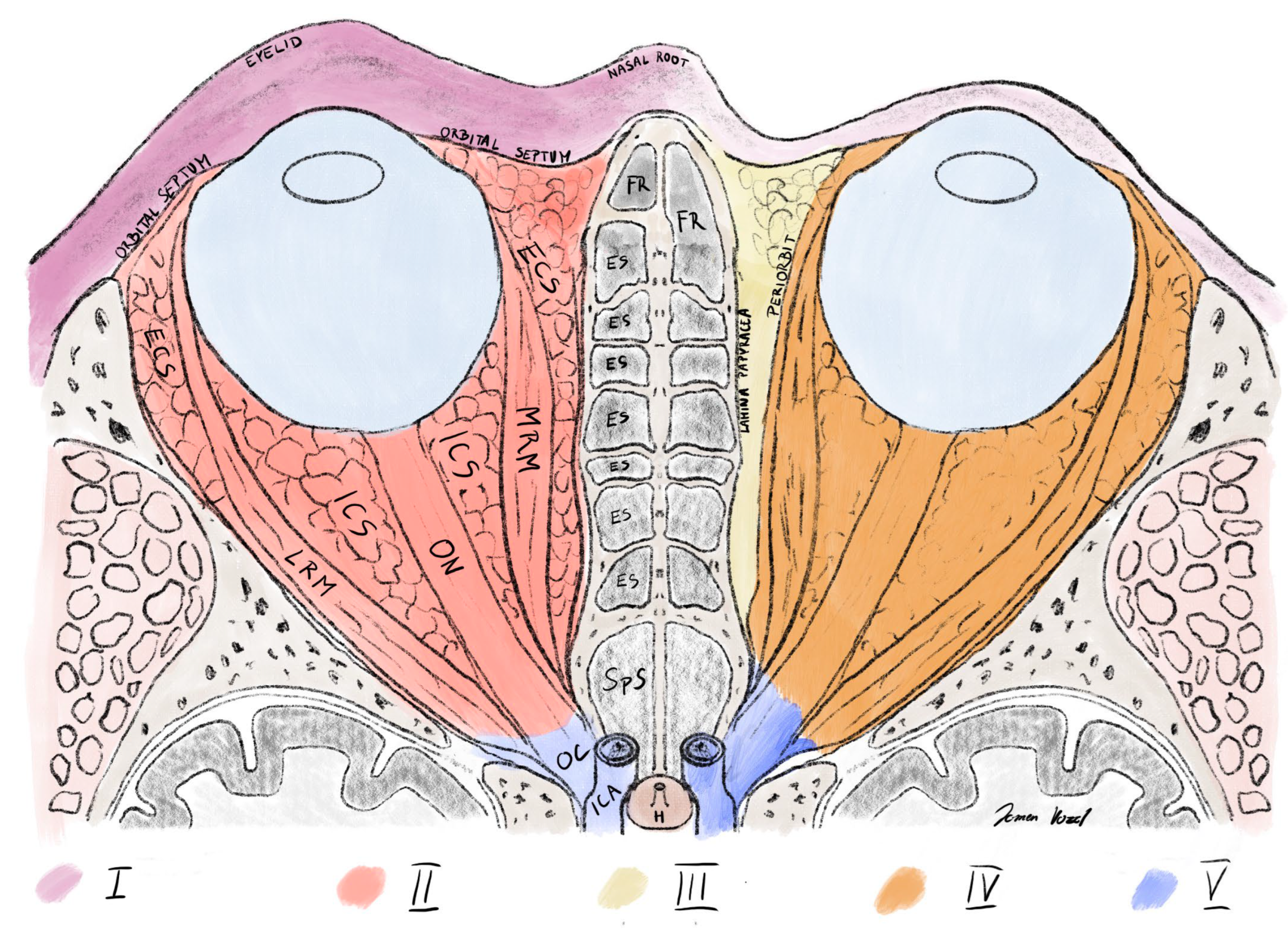

7. Orbital Complications

Orbital complications are divided into five types according to Chandler (

Table 2,

Figure 4). A higher grade corresponds to a higher degree of impairment, worse prognosis of the disease, and a more aggressive treatment modality [

8].

All orbital complications occur most frequently in the pediatric population at a mean age of approximately 7 years and in the male sex [

9]. Preseptal cellulitis of the orbit (type I) is the most common complication of sinusitis, accounting for up to 85% of all complications of sinusitis. The incidence of other complications decreases from type I to V [

3,

10,

11,

12]. In adults, orbital complications of sinusitis are more likely to require surgical treatment [

13].

The characteristics and management of orbital complications are shown in

Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics and management of orbital complications of sinusitis.

Table 2.

Characteristics and management of orbital complications of sinusitis.

| Type | Clinical Picture | Diagnosis | Treatment |

|---|

| I | Eyelid edema and erythema

(partial) eye closure | ENT | medical |

| II | Eyelid edema and erythema

(partial) eye closure

Conjunctival erythema and chemosis

Painful eye

Proptosis

Ophthalmoplegia and painful eye movements

Possible vision loss | ENT + CT p.s. | medical + (surgical) |

| III | Proptosis

Ophthalmoplegia and painful eye movement

Painful eye

Possible vision loss

Possible conjunctival erythema and chemosis

Possible eyelid edema and erythema | ENT + CT p.s. | surgical + medical |

| IV | See II | ENT + CT p.s. | surgical + medical |

| V * | See II

Severe headache/facial pain in forehead, eye, and/or cheek (CN V1, V2 damage)

Ptosis and mydriasis (CN III palsy)

Possible disturbed eye abduction as an initial sign (CNVI)

Typically, but rarely, bilateral clinical picture of II

Meningism | ENT + CT p.s. + CTV head | surgical + medical |

Orbital complications arise from two mechanisms: direct spread of infection from the paranasal sinus to the orbital wall or retrograde thrombophlebitis of non-valvular veins. In children, infection in the orbit most commonly spreads from the ethmoid sinus (i.e., acute ethmoiditis) to the porous medial orbital wall [

13]. In adults, infection in the orbit most commonly spreads due to acquired orbital wall dehiscence either post-traumatically or iatrogenically [

11]. In adults, compared to the pediatric population, the other paranasal sinuses are also frequently affected [

11,

12] and signs of chronic rhinosinusitis are present [

11].

Orbital complications rarely cause blindness or death in modern times since the introduction of antimicrobial therapy. Blindness in orbital complications can result from three mechanisms [

13]:

Ischemic optic neuropathy due to obstruction of flow through the arteries and veins of the eye (i.e., due to pressure on the vessels when intraorbital pressure is elevated);

Ischemic optic neuropathy due to pressure directly on the optic nerve;

Optic neuritis due to the direct spread of inflammation to the optic nerve.

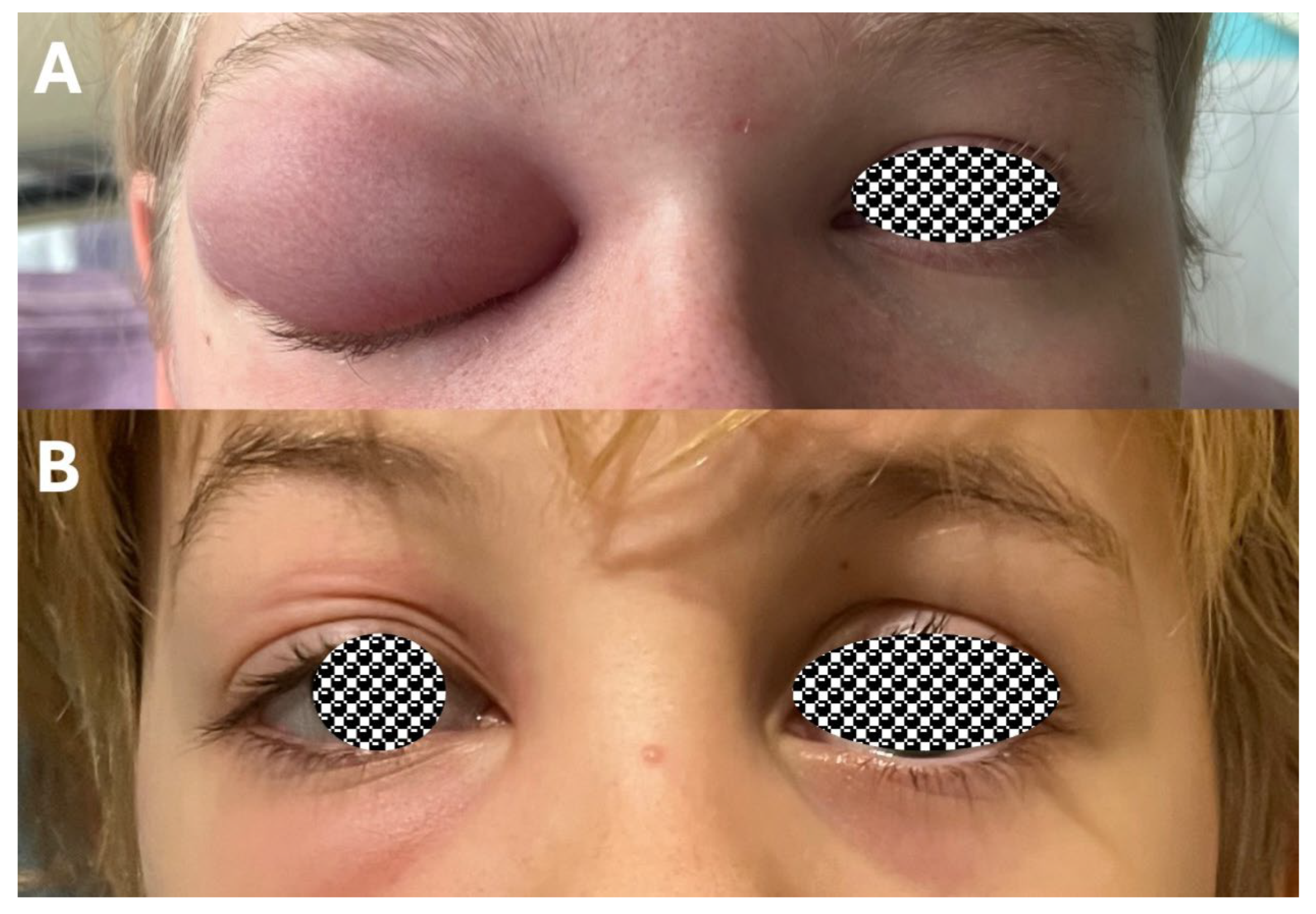

7.1. Preseptal Orbital Cellulitis (Type I)

Preseptal cellulitis of the orbit is inflammation of the subcutaneous tissue anterior to the orbital septum (

Figure 4) [

8,

13]. It is probably due to disturbed venous drainage and congestion of the eyelid veins due to extension of the inflammation beyond the sinus, causing swelling in front of the orbital septum [

14].

It presents as swelling, redness, and tenderness of the lower and upper eyelids, and the eye is either partially or completely closed (

Figure 5). The sclera is pale, in a normal position, and with normal eye movements [

13]. In a child with such a clinical picture, no imaging diagnosis is necessary. If the condition worsens or does not improve within 24–48 h of initiation of therapy, contrast–enhanced CT of the paranasal sinuses is performed [

15]. CT is also primarily useful later during surgery [

13]. In an adult with this clinical picture, there is a higher likelihood of other orbital complications of sinusitis or other diseases in the paranasal sinuses and orbit, and therefore contrast-enhanced CT of the paranasal sinuses is decided on earlier.

Treatment of preseptal orbital cellulitis is always conservative. Early initiation of empiric antimicrobial therapy is important, followed by targeted antimicrobial therapy [

13]. Prior to the initiation of antimicrobial therapy, it is necessary to obtain infectious material through aspiration or nasal swab [

13,

16]. According to the European position paper on diagnostic tools in rhinology, samples for microbiological analyses should be taken in cases of ABRS non-responsive to empirical antimicrobial therapy and topical nasal steroids and in sinusitis complications. Swabs should not be non-directed (e.g., nasal or nasopharyngeal swab) but should be endoscopically directed towards the middle meatus. The latter presents the zone of maxillary, frontal, and anterior ethmoid sinus drainage. Due to technical challenges, these swabs should be taken by otorhinolaryngologists [

18].

In mild cases of preseptal cellulitis (for example, if the eye is more than half open and oral antibiotic ingestion will be feasible (e.g., school child)), oral antimicrobial therapy can be initiated on an outpatient basis and the condition reassessed after 24–48 h on an outpatient basis [

15]. Other cases are treated in hospital with intravenous antimicrobial therapy [

13,

15]. In addition to systemic antimicrobial therapy, patients also receive a topical nasal therapy with a nasal decongestant (e.g., a topical nasal corticosteroid (e.g., mometasone) is also commonly added [

17], but research does not support this in ABRS [

4,

19]. There is no firm evidence for the efficacy of nasal aspiration with negative pressure (i.e., jargon for “displacement” or Prötz aspiration) [

20,

21].

In some institutions, ABRS complications in children and adults are also effectively treated with systemic corticosteroids [

9,

17,

19,

22,

23]. Corticosteroids (e.g., 1 mg/kg body weight daily, 3–4 days [

9]) reduce hospitalization time but not the need for surgery according to systematic reviews [

19,

23], but sufficient high-quality research is still lacking to introduce this therapy into routine use [

22].

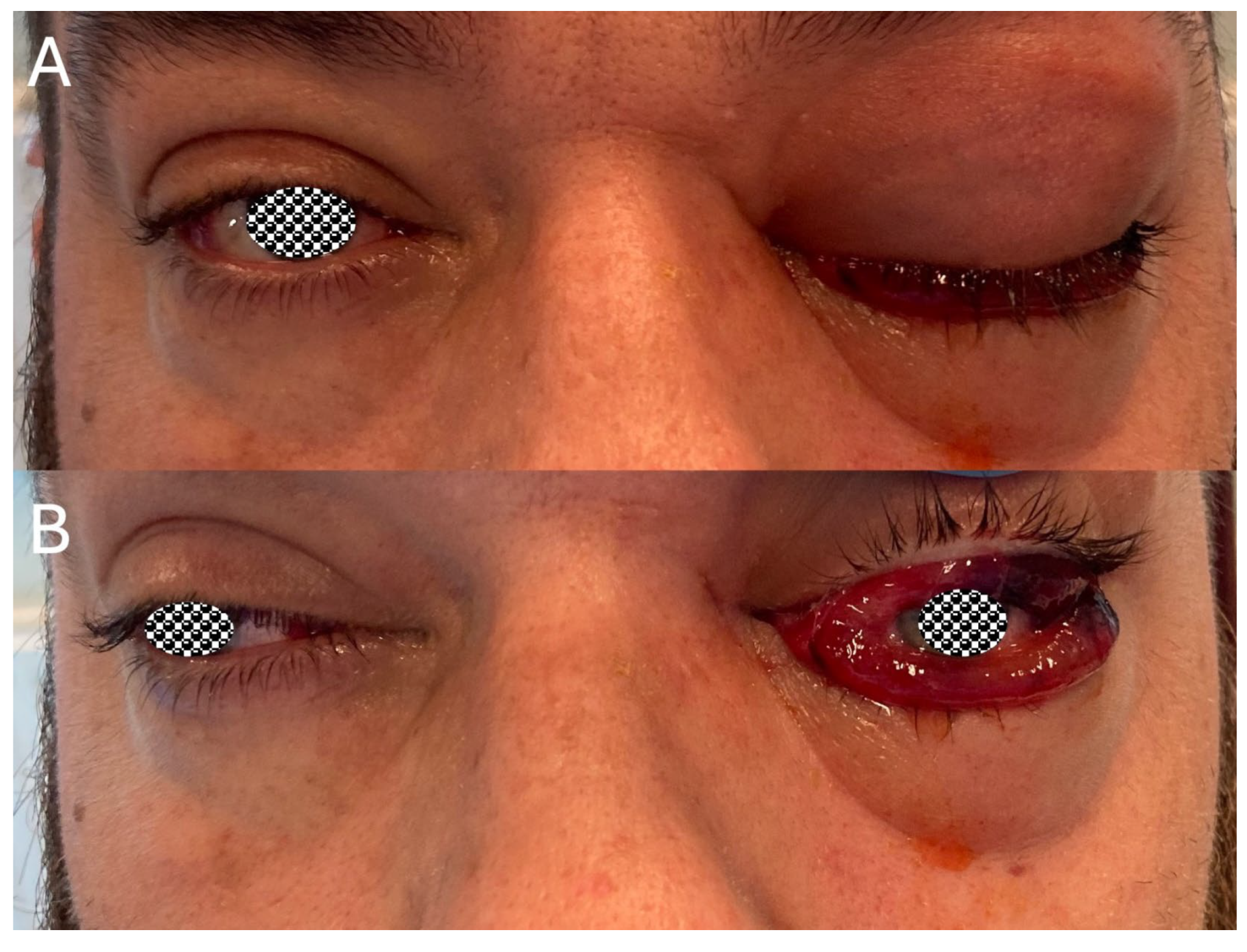

7.2. Orbital Cellulitis (Type II)

Orbital cellulitis refers to inflammation of the soft tissues of the orbit posterior to the orbital septum and is therefore sometimes referred to as postseptal cellulitis (

Figure 4). In the case of sinusitis, it can arise because of spreading of the preseptal cellulitis posteriorly through the orbital septum or directly from the infected sinus [

13].

In addition to swelling, redness, and a closed eye, conjunctival swelling (i.e., chemosis) and globe proptosis are typically present, followed by ocular pain in 80% and then painful and impaired eye movements with double vision (

Figure 6). The eye is reddened due to the swelling and inflammation of the conjunctiva. In severe cases, complete ophthalmoplegia occurs, followed by color vision impairment due to impaired optic nerve function (first perception of red), followed by deterioration of visual acuity to complete blindness with relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) [

6,

13]. In orbital cellulitis, compared with preseptal cellulitis, the clinical picture of systemic involvement is more pronounced, with fever, chills, general weakness, and high laboratory signs of inflammation.

As with other orbital complications, the diagnosis of orbital cellulitis requires careful clinical examination. In the case of a completely closed eye, it should be opened to assess the conjunctiva, eye movements, and pupillary reactions. At the same time, color vision is assessed through Ishihara orientation. In the case of clinical suspicion of orbital cellulitis, a contrast-enhanced CT of the paranasal sinuses and ophthalmological treatment are urgently required. The ophthalmologist can objectify, among other things, signs of optic nerve damage and visual impairment [

13]. It is more difficult for the ophthalmologist to assess visual impairment in a preschool child, so, in this case, we rely mainly on ENT examination and CT.

As with preseptal cellulitis, treatment of orbital cellulitis is primarily conservative, with systemic antibiotic therapy and adjuvant topical intranasal therapy (nasal decongestant, nasal corticosteroid, and saline). After collection of sputum specimens, empiric antibiotic therapy is instituted as directed by the infectious disease specialist pending the results of the microbiological examination of the pus, as antibiotic therapy varies in different age groups. Polymicrobial infection is more common in older children and adults. Surgical treatment of orbital cellulitis is extremely rare due to the efficacy of antimicrobial therapy, and it is only performed in cases of visual impairment or deterioration despite conservative treatment [

13]. In case of worsening, a CT of the paranasal sinuses should therefore be repeated first to exclude abscess (type III and IV) or cavernous sinus thrombosis (type V). The aim of surgical treatment in orbital cellulitis is to drain the infected paranasal sinuses, obtain sputum, and reduce intraorbital pressure via a transnasal endoscopic approach and/or an extranasal approach through upper eyelid and/or face incision if necessary.

7.3. Subperiosteal Orbital Abscess (Type III)

A subperiosteal orbital abscess is a purulent infection between the periosteum of the orbit (i.e., periorbita) and the bony wall of the orbit (

Figure 4). It typically occurs in the medial wall of the orbit in the context of recovering ethmoiditis, but, in adolescents and adults, it occurs more commonly in the upper wall of the orbit due to frontal sinus infection. It can occur in the context of preseptal or postseptal cellulitis or in isolation [

13].

In a medial orbital wall abscess, the globe is displaced inferolateral and proptosis, impaired eye movements, double vision, visual impairment, and chemosis in the case of elevated intraorbital pressure are present. In associated cellulitis, eyelid swelling is also present (

Figure 7). A small abscess may present only with an uncharacteristic clinical picture of sinusitis [

6,

13].

Subperiosteal orbital abscess is diagnosed through a combination of clinical examination and CT of the paranasal sinuses with CS. If an abscess is found, an ophthalmological examination is performed to determine visual acuity, intraocular pressure, RAPD, proptosis, and impaired eye movements [

24].

Treatment of subperiosteal orbital abscess is always conservative and often surgical. The frequency of surgical treatment varies between institutions [

17,

25]. Surgical intervention is required when there is visual impairment or deterioration of the condition despite conservative therapy [

13]. Different criteria for non-surgical treatment have been developed for abscesses in the pediatric and adult populations (

Table 3) [

13,

25,

26].

Table 3.

Criteria for non-surgical treatment of subperiosteal orbital abscess.

Table 3.

Criteria for non-surgical treatment of subperiosteal orbital abscess.

| Conservative treatment |

| Age 1–9 years |

| No visual impairment |

| Abscess less than 10 mm wide on the medial wall |

| Absence of intracranial infection |

| Absence of frontal sinusitis |

| No anaerobic infection expected (no air inclusions on CT or suspected odontogenic infection) |

In subperiosteal abscess in children over 9 years and adults, the threshold for surgical treatment is lower due to the higher incidence of polymicrobial infection. In neonates and infants, subperiosteal abscess is very rare, but surgical treatment is advised due to the specificity of the causative agents [

13,

25,

26].

Surgical treatment of subperiosteal orbital abscesses medial to the mid-pupillary line is usually performed transnasally endoscopically, whereas abscesses superolateral to the midline are treated through an incision in the face or the upper eyelid. Where a causative transnasal endoscopic approach is not sufficient, an extranasal approach by upper eyelid and/or face incision may be necessary [

13].

7.4. Orbital Abscess (Type IV)

Refers to an abscess within the periorbita, which may arise from the progression of orbital cellulitis or spillage of a subperiosteal abscess (

Figure 4). It is divided into extraconal (i.e., outside of the outer eye muscles) and intraconal abscess (i.e., inside of the outer eye muscles) based on its localization within the cone of the orbit [

13].

Clinically, it is very challenging to differentiate orbital abscess from orbital cellulitis and subperiosteal abscess, and a contrast-enhanced CT of the paranasal sinuses should be performed. As with subperiosteal abscess and orbital cellulitis, an ophthalmological examination is required. Patients have marked systemic symptoms and signs of infection. Compared with orbital cellulitis and subperiosteal abscess, visual impairment is usually present [

6,

13].

Treatment of orbital abscess is always conservative and surgical. The latter can be performed transnasally endoscopically with or without drainage through an incision on the face and/or eyelid [

13,

17].

7.5. Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis (Type V)

Cavernous sinus thrombosis can be classified as an orbital complication (

Table 1 and

Table 2,

Figure 4), orbital apex complication, or intracranial sinusitis complication. In addition to sinusitis, other causes of septic cavernous sinus thrombosis are primary infection of the orbit, face, oral cavity, pharynx, and ears. Aseptic causes of thrombosis are rare and include, e.g., trauma, tumors, surgery, and autoimmune causes (e.g., Tolosa–Hunt syndrome) [

27,

28]. The diagnostic process is particularly challenging in the diagnosis of Tolosa–Hunt syndrome, which is a granulomatous inflammation of unknown cause affecting mainly the cavernous sinus and, more rarely, the apex of the orbit and the mandibular and maxillary nerves [

29].

The cavernous sinus is a cerebral venous sinus located lateral to the sphenoid sinus, posterolateral to the ethmoid cells, and posterolateral to the orbit and therefore often arises in the context of an infection of the sphenoid sinus or the ethmoid sinus or infection in the orbit due to retrograde thrombophlebitis of the small veins or a direct infection via the ophthalmic vein draining into the cavernous sinus. Infection can progress to adjacent venous sinuses (e.g., petrous sinus) and to the contralateral cavernous sinus via the intercavernous sinuses (

Figure 1B and

Figure 4) [

13].

Thrombosis of the cavernous sinus can manifest in different ways depending on the extent of infection in the orbit and the involvement of structures in the cavernous sinus. Typically, the former manifests as a rapidly progressive unilateral stabbing headache in the forehead, eye, and cheek due to damage to the first and second branches of the trigeminal nerves (i.e., ophthalmic and maxillary nerve), which are in the wall of the cavernous sinus. In the initial absence of signs of orbital infection, the disease progresses to a clinical picture of severe orbital cellulitis due to disturbed venous drainage of the orbit causing a rise in intraorbital pressure. Ophthalmoplegia is due to intraorbital involvement and damage to the cranial nerves in the cavernous sinus innervating the external ocular muscles (oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerve). The damage to the n. oculomotorius is also manifested as ptosis and mydriasis. In the case of thrombosis due to sphenoid sinusitis, the initial sign may be impaired abduction of the eye, as the n. abducens runs most medially in the cavernous sinus. Typically, but rarely, cavernous sinus thrombosis presents with bilateral orbital signs resembling severe bilateral orbital cellulitis (

Table 2) [

13]. Clinical suspicion of cavernous sinus thrombosis due to sinusitis should also be established in the setting of a clinical picture of meningism (e.g., quantitative disturbances of consciousness, photophobia, positive meningeal signs, fever) [

13].

Diagnosis of cavernous sinus thrombosis is radiological, and urgent CT venography of the brain with contrast-enhanced CT of the paranasal sinuses should be performed, which often shows inflammation of the paranasal sinuses and a filling defect of the cavernous sinus. In case of persistent suspicion of cavernous sinus thrombosis or intracranial infection, head MR venography or CT venography is urgently performed, which is the most sensitive method to diagnose thrombosis. A chest X-ray is performed to exclude distant complications (e.g., septic pulmonary thromboembolism) (

Figure 8) [

30].

Septic thrombosis of the cavernous sinus is treated conservatively and surgically. Surgical drainage of the affected paranasal sinuses and orbital decompression in case of elevated intraorbital pressure are performed [

13,

30,

31]. Due to an 11% mortality rate and, in a third of cases, permanent functional visual impairment despite modern management of the disease [

31], patients are usually admitted to the intensive care unit of the infectious diseases department. In addition to antimicrobial and supportive therapies, anticoagulant therapy with heparin is usually introduced to reduce disease mortality [

32], although strong supportive evidence for the effectiveness of this therapy is still lacking [

30,

32].

8. Bony Complications

Bony complications can be divided into Pott’s puffy tumor and atypical skull base osteomyelitis (ASBO).

8.1. Pott’s Puffy Tumor

Sir Percival Pott first described osteomyelitis of the cranial bone in 1775 in a patient with a subpericranial abscess following injury to the frontal bone [

33]. Later, it was recognized that osteomyelitis of the frontal bone was more common in frontal sinusitis, and the name Pott’s puffy tumor was coined. Typical cases are a young male with infection of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus and overlying soft tissues with abscess formation [

34,

35].

The typical presentation is redness and supraorbital swelling. Fluctuation and, in advanced cases, fistulation of the abscess outwards may occur. Often, there are signs of inflammation of the eye due to inflammation or direct spread of infection preseptally (e.g., upper eyelid abscess) or postseptally into the orbit (e.g., subperiosteal orbital ceiling abscess) (

Figure 9). Due to the spread of infection via the diploic veins of the frontal bone draining intracranially, the disease is complicated by intracranial infection in approximately 30–70% (

Figure 10) [

34,

36,

37,

38].

In addition to clinical examination, imaging is important in the diagnosis of the disease, including contrast-enhanced CT of the paranasal sinuses and contrast-enhanced MRI of the head. Elevated parameters of bacterial infection are seen in laboratory blood tests [

34,

36].

The treatment of Pott’s puffy tumor is primarily surgical and antimicrobial. The gold standard of care is mainly endoscopic sinus surgery to restore frontal sinus drainage and concomitant drainage of the abscess with or without some form of external procedure. In cases of extensive disease or chronic inflammation, cranialization or obliteration of the frontal sinus is performed [

36,

37].

8.2. Atypical Skull Base Osteomyelitis

ASBO is a rare but fatal disease that usually involves infection of the ethmoid, sphenoid, occipital, or temporal bones that constitute the skull base. Unlike typical osteomyelitis of the skull base (i.e., otogenic osteomyelitis, which is usually due to advanced necrotizing infection of the external auditory meatus), atypical osteomyelitis does not have an otogenic cause. Some authors refer to it as sinonasal or non-otogenic osteomyelitis of the skull base. It is most commonly caused by infection of the nose and paranasal sinuses with bacteria (

Staphylococcus aureus,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and atypical mycobacteria) or fungi (e.g.,

Aspergillus spp.) in patients with immunodeficiency (e.g., diabetes mellitus) [

39].

The distinction between typical and ASBO is challenging, as inflammation in both types can involve the clivus. In this case, they can be distinguished clinically, especially otoscopically, as typical usually presents symptoms and signs of inflammation of the external auditory canal or middle ear. The latter is also a more familiar disease, and diagnosis is usually not difficult. Conversely, the diagnosis and treatment of ASBO are challenging [

39].

ASBO usually presents with non-specific symptoms, such as headache and facial pain. At the same time, other symptoms are usually present as part of a nasal and paranasal sinus infection (e.g., clinical picture of sinusitis) or facial (e.g., cellulitis or furuncle), oral (e.g., odontogenic abscess), or pharyngeal (e.g., pharyngitis) infection, which is confirmed through clinical examination. Otalgia may be present but without otoscopic signs of ear infection, in which case osteomyelitis would be diagnosed as typical. Fever is present in less than 20%. ASBO should always be considered in a patient with ENT infection when signs and symptoms of concomitant cerebral nerve damage, especially of the VI and lower cerebral nerves (especially IX and X), disturbances of consciousness, and other neurological deficits are present. Cerebral nerve impairment is present in about half of cases. Facial palsy, manifested by facial paresis, is present in 21%, although it is more typical of the typical form. The role of the otorhinolaryngologist is essential in carrying out a thorough clinical examination, including examination of cranial nerve function, hearing, and balance tests, if the patient’s condition permits [

39].

ASBO is diagnosed through MRI and CT of the skull base and occasionally through nuclear imaging diagnostic tests (e.g., scintigraphy, fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), and single photon emission computer tomography (SPECT)). Definitive diagnosis requires identification of the causative agent through pathohistological and microbiological examination of specimens taken intraoperatively. In case of negative results of microbiological examinations and identification of fungi in pathohistological examinations, paraffin sections of the samples can be degraded, and methods for characterization of the fungal species can be used [

39].

The cornerstone of treatment of ASBO is long-term targeted antimicrobial therapy. Surgical treatment is indicated for specimen sampling, decompression of critical neurovascular structures (e.g., optic nerve, brainstem), treatment of complications (e.g., intracranial abscess), debridement (i.e., drainage of abscess, sequestrectomy), and drainage of paranasal sinuses. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is an adjunctive treatment modality [

39].

9. Orbital Apex Complications

Orbital apex complications can be divided into orbital apex syndrome, superior orbital fissure syndrome, Horner syndrome, and cavernous sinus thrombosis (

Table 1). These complications have in common that the disease process occurs in the apex of the orbit, which consists of neurovascular structures that pass through the optic canal, the superior orbital fissure, and the inferior orbital fissure. In the case of sinusitis complication in the apex of the orbit, the infection most often progresses from the sphenoid and posterior ethmoid sinus due to anatomical proximity. In the case of perineural spread of infection in the context of an invasive fungal infection, the infection may also spread to the apex of the orbit from the maxillary sinus via the pterygopalatine sinus [

7,

40].

All four syndromes differ in their anatomical location and, above all, in their clinical presentation (

Table 1). Horner syndrome is a combination of ptosis, anhidrosis, and miosis. In the case of complicated sinusitis, it is caused by damage to the sympathetic nerve fibers around the internal carotid artery (e.g., pericarotid nerve plexus), mainly in its skull base segment. Orbital apex syndrome comprises optic, oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerve dysfunctions, which course via the optic canal and the superior orbital fissure, respectively. This includes decreased visual acuity, ophthalmoplegia, abnormal pupillary responses (due to optic nerve and oculomotor nerve impairment), and disturbed sensation of the forehead, the upper eyelid, and the lateral surface of the nose. Superior orbital fissure syndrome comprises the same dysfunctions as orbital apex syndrome without optic nerve impairment, i.e., visual acuity is preserved [

7,

40].

In a patient with one of the above-mentioned syndromes, other causes should be excluded rather than a complication of sinusitis. These are other types of inflammation (e.g., sarcoidosis, Tolosa–Hunt syndrome, IgG4-related disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis), craniomaxillofacial trauma, iatrogenic defects (e.g., after transnasal endoscopic or orbital surgery), vascular reasons (e.g., carotid–cavernous fistula, other causes of cavernous sinus thrombosis, aneurysm of the internal carotid artery), endocrine causes (e.g., thyroid orbitopathy), bone metabolism disorders (e.g., fibrous dysplasia), and tumors (e.g., cancers and benign tumors) [

40].

10. Intracranial Complications

If infection from the paranasal sinuses progresses intracranially, we refer to intracranial infection or complication (

Figure 10). The spread occurs due to the close proximity of the paranasal sinuses to the intracranial space and due to venous drainage of the paranasal sinuses into the cerebral venous sinuses [

41]. In most cases, symptoms are non-specific with headache and fever in addition to the clinical picture of sinusitis [

42].

In addition to clinical examination, contrast-enhanced CT of the head and paranasal sinuses is important in the diagnosis and can confirm some intracranial complications, especially abscess. Head MRI is subsequently performed to define more precisely intracranial involvement, as accessibility in emergency situations is often poor. If meningitis is suspected and there are no signs of impending brainstem opacification, a lumbar puncture is performed to confirm the diagnosis of meningitis and guide targeted antimicrobial therapy [

42].

Treatment of intracranial complications should be prompt and aggressive to prevent permanent neurological impairment or death. It consists of conservative (i.e., in the same manner as for other complications) and surgical treatment. Surgical treatment includes neurosurgery and rhinological surgery depending on the type of complication. The indication for neurosurgery is given by a neurosurgeon and for rhinological surgery by an otorhinolaryngologist subspecialized in rhinology. Both types of intervention are performed during the same operation, usually with neurosurgery first to intervene into the sterile area. Due to the severity of intracranial complications, the patient is usually admitted to the intensive care unit of the infectious diseases department [

43].

11. Conclusions

Sinusitis is a common disease in the pediatric and adult population, which is managed at the primary level by family medicine physicians, pediatricians, and emergency physicians. Regardless of the appropriateness of treatment, complications may occur depending on the patient’s anatomical features of the nose and paranasal sinuses, the immune status of the patient, and the virulence of the microbe. Complications of sinusitis, which are rare, should be suspected in the presence of ten alarming symptoms and signs that point to orbital, bony, intracranial, and systemic complications. These are swelling or redness in the orbital area, globe malposition, protrusion or strabismus, diplopia, ophthalmoplegia, reduced visual acuity, severe headache, swelling of the forehead, and signs or symptoms of sepsis, meningitis, or neurological impairment. The management of the complication is then continued in hospitals specialized in the treatment of diseases of the nose and paranasal sinuses, with the possibility of direct collaboration between specialists in otorhinolaryngology, neurology, neurosurgery, ophthalmology, neuroradiology, and infectious disease specialists. The cornerstone of treatment is early antimicrobial therapy and surgery for abscess, visual impairment, or involvement of critical neurovascular structures.