Solar-Driven Photodegradation of Methylene Blue Dye Using Al-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Photocatalysts

2.2. Characterization

2.3. Photocatalytic Degradation Investigation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. XRD Analysis

3.2. FTIR Analysis

3.3. FESEM Analysis

3.4. EDS Analysis

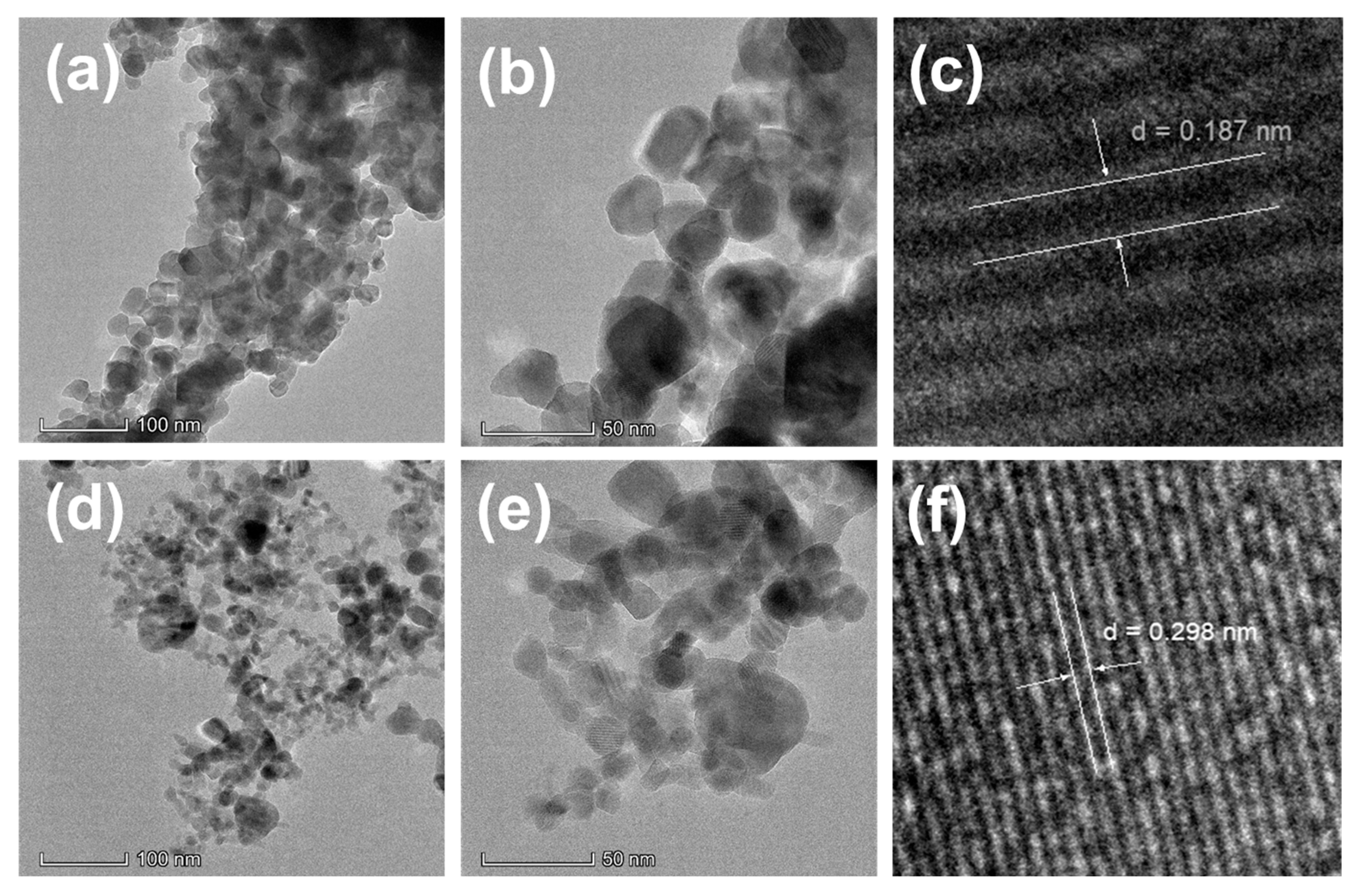

3.5. TEM Analysis

3.6. UV-DRS Analysis

3.7. XPS Analysis

3.8. Photocatalytic Degradation of MB

3.9. Photocatalytic Degradation Mechanism

3.10. Photocatalyst Reusability

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Halim, O.M.A.; Mustapha, N.H.; Fudzi, S.N.M.; Azhar, R.; Zanal, N.I.N.; Nazua, N.F.; Nordin, A.H.; Azami, M.S.M.; Ishak, M.A.M.; Ismail, W.I.N.W.; et al. A review on modified ZnO for the effective degradation of methylene blue and rhodamine B. Results Surf. Inter. 2025, 18, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanjwani, M.F.; Tuzen, M.; Khuhawar, M.Y.; Saleh, T.A. Trends in photocatalytic degradation of organic dye pollutants using nanoparticles: A review. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 159, 111613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiong, S.; Sathiyaseelan, A.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jin, T.; Wang, M.-H. Recent advances in photocatalytic nanomaterials for environmental remediation: Strategies, mechanisms, and future directions. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebanezar John, A.; Mishra, D.; Thankaraj Salammal, S.; Akram Khan, M. Factors that enhance the efficiency of TiO2 based heterogeneous photocatalyst for its application in wastewater treatment containing organic dye. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 10, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Bhagya, T.C.; Mukhanova, E.A.; Soldatov, A.V.; Henaish, A.M.A.; Mao, Y.; Shibli, S.M.A. Engineering strontium titanate-based photocatalysts for green hydrogen generation: Recent advances and achievements. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 342, 123383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shathy, R.A.; Fahim, S.A.; Sarker, M.; Quddus, M.S.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Masum, S.M.; Molla, M.A.I. Natural Sunlight Driven Photocatalytic Removal of Toxic Textile Dyes in Water Using B-Doped ZnO/TiO2 Nanocomposites. Catalysts 2022, 12, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Hu, J.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, X. Semiconductor heterojunction photocatalysts: Design, construction, and photocatalytic performances. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5234–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, H.; Sun, H.; Liu, S.; Tade, M.O.; Wang, S.; Jin, W. Recent advances in non-metal modification of graphitic carbon nitride for photocatalysis: A historic review. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 7002–7023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Kumar, A.; Dhiman, P.; Mola, G.T.; Sharma, G.; Lai, C.W. Recent advances in photocatalytic removal of sulfonamide pollutants from wastewater by semiconductor heterojunctions: A review. Mater. Today Chem. 2023, 30, 101603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusdianto, K.; Nugraha, D.F.; Sekarnusa, A.; Madhania, S.; Machmudah, S.; Winardi, S. ZnO-TiO2 nanocomposite materials: Fabrication and its applications. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1053, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfan, M.; Siddiqui, D.N.; Shahid, T.; Iqbal, Z.; Majeed, Y.; Akram, I.; Noreen; Bagheri, R.; Song, Z.; Zeb, A. Tailoring of nanostructures: Al doped CuO synthesized by composite-hydroxide-mediated approach. Results Phy. 2019, 13, 102187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Wang, J. Thermodynamic and kinetic studies of the performance effect of Al doping in the Ge-Sb-Te phase change materials. Calphad 2025, 91, 102892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiye, A.; Xu, Q.; Feng, G.; Wang, C.; Song, C.; Lu, H. Enhanced gas sensing performance of Al-doped bipyramid TiO2 crystal for advanced triethylamine detection. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 48, 113655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, F.D.; Ştefan, L.-M.; Dumitrescu, C.R.; Rahim, N.L.; Matei, M.; Boboc, M. Assessing the photocatalytic activity of ZnO/HA composites obtained through an advanced mechano-chemical grinding method. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 589, 03006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, J.; Jhun, C.G. ZnO Nanospheres Fabricated by Mechanochemical Method with Photocatalytic Properties. Catalysts 2021, 11, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alirezazadeh, F.; Sheibani, S. Facile mechano-chemical synthesis and enhanced photocatalytic performance of Cu2ZnSnS4 nanopowder. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 26715–26723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, R.S.; Navaneethan, M.; Mani, G.K.; Ponnusamy, S.; Tsuchiya, K.; Muthamizhchelvan, C.; Kawasaki, S.; Hayakawa, Y. Influence of Al doping on the structural, morphological, optical, and gas sensing properties of ZnO nanorods. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 698, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, M.; Ghosh, A.; Mondal, A.; Kargupta, K.; Ganguly, S.; Banerjee, D. Facile synthesis of aluminium doped zinc oxide-polyaniline hybrids for photoluminescence and enhanced visible-light assisted photo-degradation of organic contaminants. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 402, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, R.; Talesh, S.S.A. Sol-gel synthesis, structural and enhanced photocatalytic performance of Al doped ZnO nanoparticles. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017, 28, 1418–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Al-Hartomy, O.A.; El Okr, M.; Nawar, A.; El-Gazzar, S.; El-Tantawy, F.; Yakuphanoglu, F. Semiconducting properties of Al doped ZnO thin films. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 131, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, W.; Khan, Z.A.; Saad, A.A.; Shervani, S.; Saleem, A.; Naqvi, A.H. Synthesis and characterization of al doped ZnO nanoparticles. Int. J. Mod. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2013, 22, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putul, R.A.; Fahim, S.A.; Masum, S.M.; Molla, M.A.I. Fabrication and characterisation of B-ZnO nanoparticles for photodegradation of ciprofloxacin antibiotic and textile dyes. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2025, 105, 4208–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, A.F.; Barzinjy, A.A.; Hamad, S.M.; Almessiere, M.A. Impact of Radio Frequency Plasma Power on the Structure, Crystallinity, Dislocation Density, and the Energy Band Gap of ZnO Nanostructure. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 31605–31614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamiri, R.; Singh, B.; Scott Belsley, M.; Ferreira, J.M.F. Structural and dielectric properties of Al-doped ZnO nanostructures. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 6031–6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuili, M.; Fazouan, N.; El Makarim, H.A.; El Halani, G.; Atmani, E.H. Comparative first principles study of ZnO doped with group III elements. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 688, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdağ, A.; Budak, H.F.; Yılmaz, M.; Efe, A.; Büyükaydın, M.; Can, M.; Turgut, G.; Sönmez, E. Structural and Morphological Properties of Al doped ZnO Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016, 707, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achehboune, M.; Khenfouch, M.; Boukhoubza, I.; Leontie, L.; Doroftei, C.; Carlescu, A.; Bulai, G.; Mothudi, B.; Zorkani, I.; Jorio, A. Microstructural, FTIR and Raman spectroscopic study of Rare earth doped ZnO nanostructures. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 53, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallika, A.N.; Ramachandrareddy, A.; Sowribabu, K.; Reddy, K.V. Synthesis and optical characterization of aluminum doped ZnO nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 12171–12177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidhambaram, N. Augmented antibacterial efficacies of the aluminium doped ZnO nanoparticles against four pathogenic bacteria. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 075061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Kriti; Kaur, S.; Arora, D.; Rahul; Kandasami, A.; Singh, D.P. Correlation among lattice strain, defect formation and luminescence properties of transition metal doped ZnO nano-crystals prepared via low temperature technique. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 115920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Fang, T.; Hung, F.; Ji, L.; Chang, S.; Young, S.; Hsiao, Y. The crystallization and physical properties of Al-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 5791–5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Alqahtany, F.Z. Comparative Studies of the Synthesis and Physical Characterization of ZnO Nanoparticles Using Nerium oleander Flower Extract and Chemical Methods. J. Inorg. Organomet Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 3750–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapalis, A.; Fry, P.W.; Kennedy, K.; Farrer, I.; Kean, A.; Sharman, J.; Heffernan, J. Investigation of a novel AlZnN semiconductor alloy. Mater. Lett. X 2020, 7, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Rahul; Kaur, S.; Kriti; Arora, D.; Asokan, K.; Singh, D.P. Correlation between lattice deformations and optical properties of Ni doped ZnO at dilute concentration. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 26, 3436–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesha, A.; Nagaraja, M.; Madhu, A.; Suriyamurthy, N.; Reddy, S.S.; Al-Dossari, M.; Abd EL-Gawaad, N.S.; Manjunatha, S.O.; Gurushantha, K.; Srinatha, N. Chromium-doped ZnO nanoparticles synthesized via auto-combustion: Evaluation of concentration-dependent structural, band gap-narrowing effect, luminescence properties and photocatalytic activity. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 22890–22901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, Z.N.; Bashir, Z.; Riaz, S.; Naseem, S.; Saddiqe, Z. Transparent boron-doped zinc oxide films for antibacterial and magnetic applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 11911–11926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ahmad, M.I. Role of defects in the electronic properties of Al doped ZnO films deposited by spray pyrolysis. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 7877–7895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirirak, R.; Phettakua, P.; Rangdee, P.; Boonruang, C.; Klinbumrung, A. Unveiling the impact of excessive dopant content on morphology and optical defects in carbonation synthesis of nanostructured Al-doped ZnO. Powder Technol. 2024, 435, 119444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Shen, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Bi2O2CO3 co-catalyst modification BiOBr driving efficient photoreduction CO2. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 725, 137731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, A.; Islam, M.M. Highly efficient bimetallic counter cations-based tungsten bronzes electrocatalysts developed for sustainable oxygen evolution in acidic solution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 91, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailili, R.R.; Ji, H.; Wang, K.; Dong, X.; Chen, C.; Sheng, H.; Bahnemann, D.W.; Zhao, J. ZnO with Controllable Oxygen Vacancies for Photocatalytic Nitrogen Oxide Removal. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 10004–10017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Farsi, L.; Al-Marzouqi, F.; Al Farsi, B.; Myint, M.Z.; Varanasi, S.R.; Issac, A.; Al Abri, M.; Widatallah, H.; Souier, T. Synthesis and characterization of Al-doped ZnO nanorod array as a photocatalyst under visible light irradiation. Opt. Mater. 2025, 169, 117593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alprol, A.E.; Manaa, A.; Basaham, A.S.; Ghandour, I.M.; El-Regal, M.A.A.; El-Metwally, M.E.A. Optimized removal of methylene blue from wastewater using an activated Carbon-Zinc Oxide-Ammonia composite. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 38834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zyoud, A.; Zyoud, A.H.; Zyoud, S.H.; Nassar, H.; Zyoud, S.H.; Qamhieh, N.; Hajamohideen, A.; Hilal, H.S. Photocatalytic degradation of aqueous methylene blue using ca-alginate supported ZnO nanoparticles: Point of zero charge role in adsorption and photodegradation. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. 2023, 30, 68435–68449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molla, M.A.I.; Furukawa, M.; Tateishi, I.; Katsumata, H.; Kaneco, S. Fabrication of Ag-doped ZnO by mechanochemical combustion method and their application into photocatalytic Famotidine degradation. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A Toxic Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 2019, 54, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, R.; Saifullah, M.A.K.; Ahmed, A.Z.; Masum, S.M.; Molla, M.A.I. Synthesis of N-Doped ZnO Nanocomposites for Sunlight Photocatalytic Degradation of Textile Dye Pollutants. J. Compos. Sci. 2020, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, M.A.I.; Furukawa, M.; Tateishi, I.; Katsumata, H.; Kaneco, S. Mineralization of Diazinon with nanosized-photocatalyst TiO2 in water under sunlight irradiation: Optimization of degradation conditions and reaction pathway. Environ. Technol. 2020, 41, 3524–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molla, M.A.I.; Tateishi, I.; Furukawa, M.; Katsumata, H.; Suzuki, T.; Kaneco, S. Evaluation of reaction mechanism for photocatalytic degradation of dye with self-sensitized TiO2 under visible light irradiation. Open J. Inorg. Non-Met. Mater. 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nanoparticles | FWHM (100) (deg) | FWHM (002) (deg) | FWHM (101) (deg) | Avg. Crystallite Size (nm) | Lattice Constants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c (nm) | a (nm) | |||||

| ZnO | 0.22479 | 0.2315 | 0.24626 | 30.05 | 0.5206 ± 0.0001 | 0.3250 ± 0.0001 |

| 1% Al–ZnO | 0.28258 | 0.3114 | 0.31837 | 24.56 | 0.5207 ± 0.0001 | 0.3250 ± 0.0001 |

| 3% Al–ZnO | 0.19478 | 0.2024 | 0.21074 | 33.73 | 0.5206 ± 0.0001 | 0.3250 ± 0.0001 |

| 5% Al–ZnO | 0.19722 | 0.2048 | 0.20812 | 34.10 | 0.5203 ± 0.0001 | 0.3248 ± 0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rana, M.S.; Putul, R.A.; Salsabil, N.; Kabir, M.T.; Hossain, M.S.; Masum, S.M.; Molla, M.A.I. Solar-Driven Photodegradation of Methylene Blue Dye Using Al-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles. Appl. Nano 2026, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano7010003

Rana MS, Putul RA, Salsabil N, Kabir MT, Hossain MS, Masum SM, Molla MAI. Solar-Driven Photodegradation of Methylene Blue Dye Using Al-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles. Applied Nano. 2026; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleRana, Md. Shakil, Rupna Akther Putul, Nanziba Salsabil, Maliha Tasnim Kabir, Md. Shakhawoat Hossain, Shah Md. Masum, and Md. Ashraful Islam Molla. 2026. "Solar-Driven Photodegradation of Methylene Blue Dye Using Al-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles" Applied Nano 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano7010003

APA StyleRana, M. S., Putul, R. A., Salsabil, N., Kabir, M. T., Hossain, M. S., Masum, S. M., & Molla, M. A. I. (2026). Solar-Driven Photodegradation of Methylene Blue Dye Using Al-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles. Applied Nano, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano7010003