Biodegradable 3D Screen Printing Technique for Roll-to-Roll Manufacturing of Eco-Friendly Flexible Hybrid Electronics

Abstract

1. Introduction

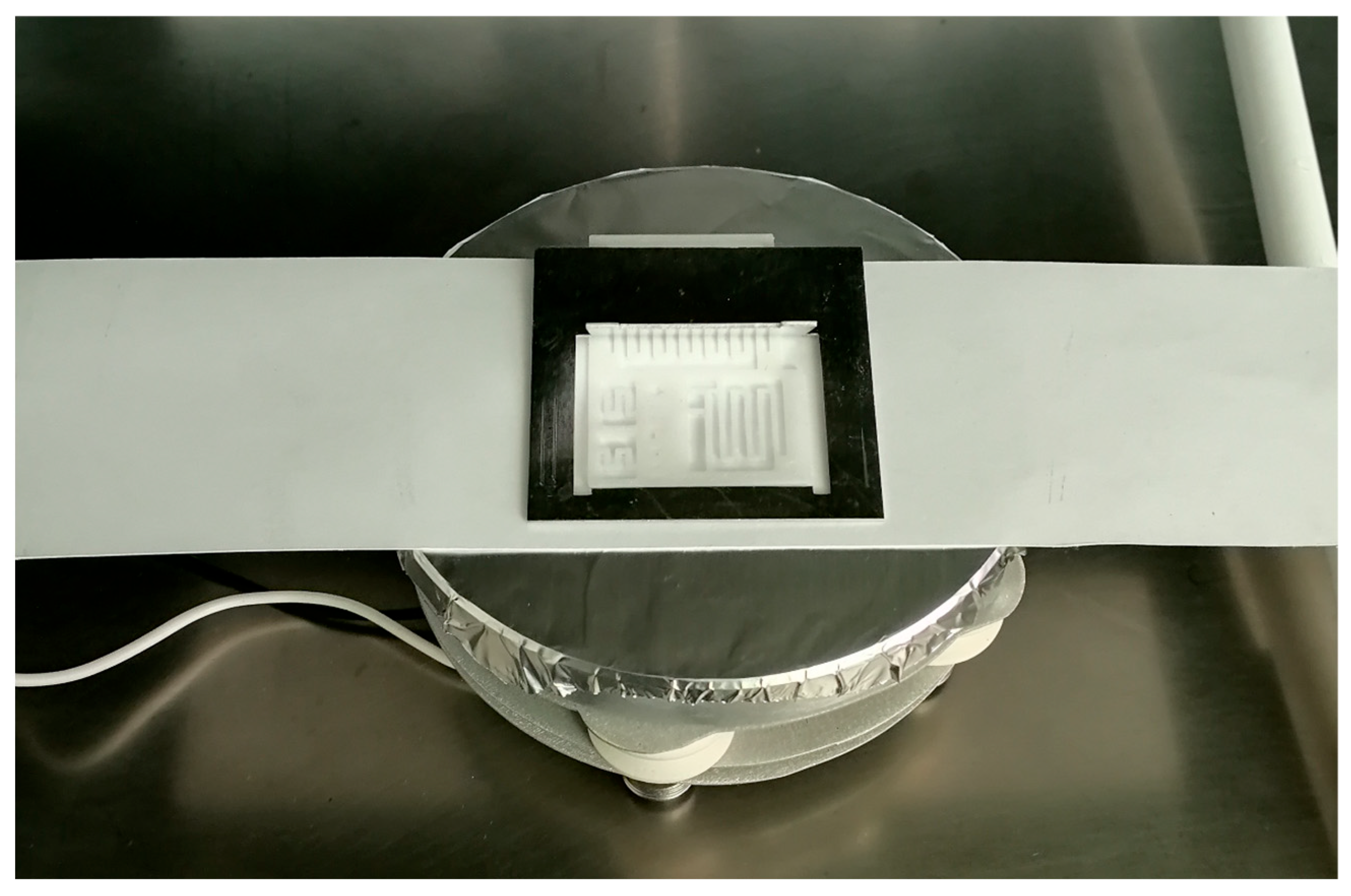

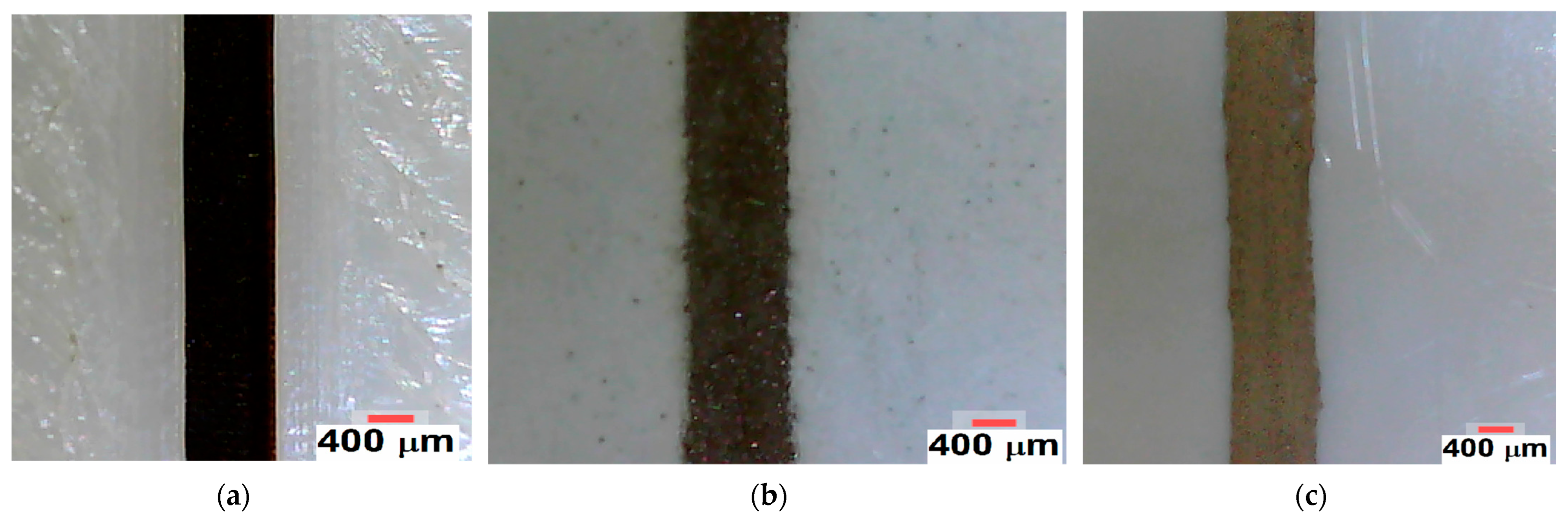

2. Materials and Methods

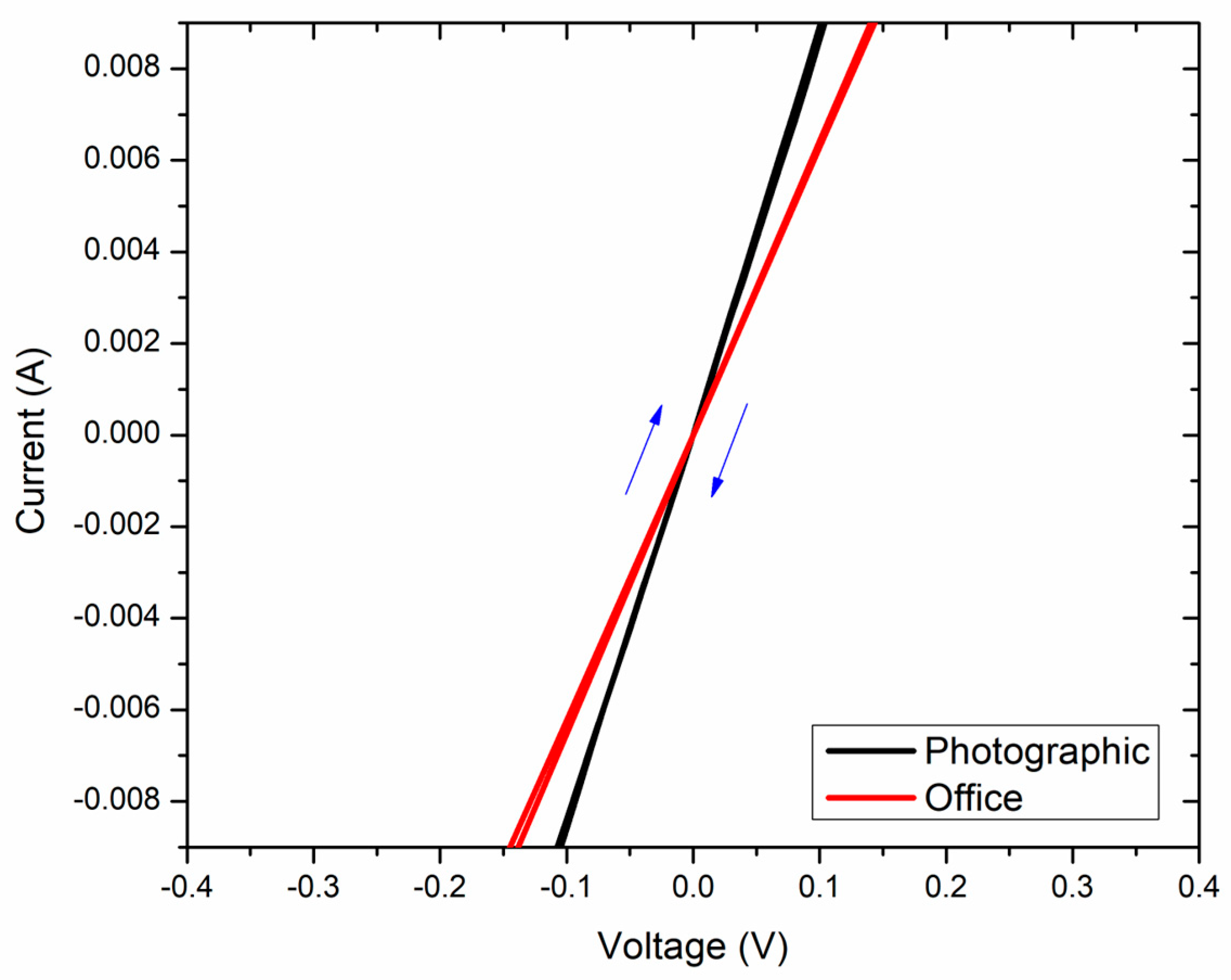

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suja, F.; Rahman, R.A.; Yusof, A.; Masdar, M.S. e-Waste Management Scenarios in Malaysia. J. Waste Manag. 2014, 2014, 609169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A.K.; Li, J.; Koh, L.; Ogunseitan, O.A. Circular economy and electronic waste. Nat. Electron. 2019, 2, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista eCommerce—Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/emo/ecommerce/worldwide?currency=usd (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Nikou, V.; Sardianou, E. Bridging the socioeconomic gap in E-waste: Evidence from aggregate data across 27 European Union countries. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2023, 5, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Tan, Q.; Yu, J.; Wang, M. A global perspective on e-waste recycling. Circ. Econ. 2023, 2, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, V.; Balde, C.P.; Kuehr, R. E-Waste Statistics: Guidelines on Classification Reporting and Indicators, 2nd ed.; United Nations University: Bonn, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, M.; Kettle, J.; Dahiya, R. Electronic Waste Reduction Through Devices and Printed Circuit Boards Designed for Circularity. IEEE J. Flex. Electron. 2022, 1, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, K.; Zhang, S.; Kettle, J. Improving the sustainability of printed circuit boards through additive printing. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Technologies for Sustainability (SusTech), Portland, OR, USA, 19–22 April 2023; pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; He, Z.; Choy, W.; Low, P.; Sonar, P.; Kyaw, A. Biodegradable Materials and Green Processing for Green Electronics. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2001591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Thielens, A.; Muin, S.; Ting, J.; Baumbauer, C.; Arias, A. A New Frontier of Printed Electronics: Flexible Hybrid Electronics. Adv. Mater. 2019, 32, 1905279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, G.; Jia, Z.; Chang, J. Flexible Hybrid Electronics: Review and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Florence, Italy, 27–30 May 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.; Huang, Y.; Bu, N.; Wang, X.; Xiong, Y. Inkjet printing for flexible electronics: Materials, processes and equipments. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2010, 55, 3383–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, C.; Denchev, Z.; Cruz, S.; Viana, J. Chemistry of solid metal-based inks and pastes for printed electronics—A review. Appl. Mater. Today 2019, 15, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrill, M.; Abele, D.; Wagner, M.; LeBlanc, S. Sterically Stabilized Multilayer Graphene Nanoshells for Inkjet Printed Resistors. Electron. Mater. 2021, 2, 394–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallan, H.; Sadie, J.; Kitsomboonloha, R.; Volkman, S.; Subramanian, V. Systematic Design of Jettable Nanoparticle-Based Inkjet Inks: Rheology, Acoustics, and Jettability. Langmuir 2014, 30, 13470–13477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutiette, A.; Toothaker, C.; Corless, B.; Boukaftane, C.; Howell, C. 3D printing direct to industrial roll-to-roll casting for fast prototyping of scalable microfluidic systems. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenfeld, J.; Rother, L.; Saccone, M.; Dulay, M.; DeSimone, J. Roll-to-roll, high-resolution 3D printing of shape-specific particles. Nature 2024, 627, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikulnig, J.; Kosel, J. Fabrication Technologies for Flexible Printed Sensors. Encycl. Sens. Biosens. 2023, 3, 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Si, B.; Hu, Y.; Yao, L.; Jin, Q.; Zheng, C.; Wu, Y.; Wu, X.; Gao, X. 3D Printing Technologies in Advanced Gas Sensing: Materials, Fabrication, and Intended Applications: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 5916–5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Gond, R.; Beniwal, A.; Li, C.; Rawat, B. Disposable and Highly Sensitive Humidity Sensor based on PEDOT:PSS/GO Heterostructure. IEEE J. Flex. Electron. 2025, 4, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Fan, Z.; Richstein, J.; Sussman, M.; Nishida, T. Fabrication of 3D Screen-Printed Micro-Cavities Towards Sweat Sensors for Integrated Flexible Hybrid Electronics. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Sensors, Kobe, Japan, 20–23 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Lan, Z.; Li, K.; Zhu, K.; Song, X.; Zhang, R.; Chen, W.; He, J.; Hou, X.; Chou, X. Fully Flexible Integrated and Self-Powered Smart Bending Strain Skin for Wireless Monitoring of Heavy Industrial Equipment. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 2502012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, E.; Beduk, T.; Lengger, S.; Vijjapu, M.; Carrara, S.; Kosel, J. Glucose Sensor Printed on Algae-Based Substrates for Eco-Conscious Point-of-Care Devices. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2025, 9, 4500204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.; Santurkar, V.; Amreen, K.; Ponnalagu, R.; Goel, S. Gold/Cerium(IV) Oxide-Modified Flexible Electrodes for Enzymatic Detection of Triglyceride. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2024, 8, 4504704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punkari, T.; Kattainen, A.; Fonseca, A.; Pronto, J.; Keskinen, J.; Mäntysalo, M. Roll-to-roll Screen Printed Monolithic Supercapacitors and Modules with Varying Electrode Areas. IEEE J. Flex. Electron. 2025, 4, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egels, M.; Venouil, A.; Hannachi, C.; Pannier, P.; Benwadih, M.; Serbutoviez, C. Screen-Printed 1 × 4 Quasi-Yagi-Uda Antenna Array on Highly Flexible Transparent Substrate for the Emerging 5G Applications. Electronics 2025, 14, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, C.; Li, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, J.; Wu, M.; Liu, W.; Shi, T.; He, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Dynamic X-ray imaging with screen-printed perovskite CMOS array. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Zou, F.; He, Y.; Sun, P.; Li, H.; Xiao, Y. High-Sensitivity and Broad Linearity Range Pressure Sensor Based on Printed Microgrids Structure. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 2372–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.; Lim, S. Optically Transparent and Rollable Metafilm for Electromagnetic Absorption using Screen Printed Metal Mesh. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2025, 24, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Jia, Z.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Tao, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Xu, Z.; Luo, C.; Chen, Z. Printed Heating and Temperature-Sensing Film in Transient Plane Source Sensor and Its Application in Measuring Thermal Conductivity. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarathna, U.; Garakani, B.; Weerawarne, D.; Alhendi, M.; Poliks, M.; Misner, M.; Burns, A.; Khinda, G.; Alizadeh, A. Reliability of Screen-printed Water-based Carbon Resistors for Sustainable Wearable Sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 6449–6463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniwal, A.; Gond, R.; Karagiorgis, X.; Rawat, B.; Li, C. Room-Temperature-Operated Fe2O3/PANI-Based Flexible and Eco-Friendly Ammonia Sensor with Sub-ppm Detectability. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2025, 9, 2000404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, L.; Dinesh, S.; Jhajharia, S.; Padmanabhan, M.; Mahajan, R.; Chithra, P. Screen Printable, Sustainable Water-Based Functional Ink from Coal-Derived Reduced Graphene Oxide for Humidity Sensing. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2025, 9, 2000204. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando, A.; Gaiardo, A.; Valt, M.; Trentini, G.; Magoni, M.; Tosato, P.; Krik, S.; Lugli, P.; Petti, L.; Lorenzelli, L. Towards Flexible & Wearable Diabetes Monitoring: Printing of Metal Oxide Materials for Chemiresistive Gas Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Flexible Electronics Technology Conference, Bologna, Italy, 15–18 September 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersan, T.; Birer, O.; Dalkilic, A.; Inal, M.; Dericioglu, A. Fabricating X Band Frequency Selective Surface on Glass Fabric by Screen Printing Method. IEEE J. Flex. Electron. 2025, 3, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunde, B.; Woldeyohannes, A. 3D printing and solar cell fabrication methods: A review of challenges, opportunities, and future prospects. Results Opt. 2023, 11, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Măghinici, A.; Bounegru, A.; Apetrei, C. Electrochemical Detection of Diclofenac Using a Screen-Printed Electrode Modified with Graphene Oxide and Phenanthroline. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.; Rocha, R.; Castro, S.; Trindade, M.; Munoz, R.; Richter, E.; Angnes, L. Posttreatment of 3D-printed surfaces for electrochemical applications: A critical review on proposed protocols. Electrochem. Sci. Adv. 2022, 2, e2100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, M.; Sanna, M.; Muñoz, J.; Ghosh, K.; Wert, S.; Pumera, M. Heterolayered carbon allotrope architectonics via multi-material 3D printing for advanced electrochemical devices. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2023, 18, e2276260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mania, S.; Staszczyk, K.; Banach, A.; Krawcewicz, R.; Mielewczyk, A.; Tylingo, R. From waste to value: Functionalized chokeberry-filled PLA filaments for 3D printing. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskakova, K.I.; Okotrub, A.V.; Bulusheva, L.G.; Sedelnikova, O.V. Manufacturing of Carbon Nanotube-Polystyrene Filament for 3D Printing: Nanoparticle Dispersion and Electromagnetic Properties. Nanomanufacturing 2022, 2, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, A.; Ahmad, I.; Eisa, M.H.; Maaza, M.; Khan, H. Manufacturing Strategies for Graphene Derivative Nanocomposites—Current Status and Fruitions. Nanomanufacturing 2023, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arockiam, A.; Subramanian, K.; Padmanabhan, R.; Selvaraj, R.; Bagal, D.; Rajesh, S. A review on PLA with different fillers used as a filament in 3D printing. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 50, 2057–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S.; Kim, Y.; Park, G.; Lee, D.; Park, J.; Mossisa, A.; Lee, S.; Myung, J. Biodegradation of 3D-Printed Biodegradable/Non-biodegradable Plastic Blends. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 5077–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceron, S.; Barba, D.; Dominguez, M.A. Solution-Processable and Eco-Friendly Functionalization of Conductive Silver Nanoparticles Inks for Printable Electronics. Electron. Mater. 2024, 5, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemune, H.; Maeda, S.; Cacucciolo, V.; Iwata, Y.; Iwase, E.; Hashimoto, S.; Sugano, S. Printed Paper Robot Driven by Electrostatic Actuator. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2017, 2, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, M.; Sosa, J. Copper phthalocyanine buffer interlayer film incorporated in paper substrates for printed circuit boards and dielectric applications in flexible electronics. Solid State Electron. 2020, 172, 107898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Shu, M.; Yuan, C.; Dou, T.; Guo, L.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, D. Desing of water-based conductive inks with enhanced printability, conductivity, and anti-fouling ability. Sens. Act. A Phys. 2025, 395, 117055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ceron, S.; Barba, D.; Dominguez, M.A. Biodegradable 3D Screen Printing Technique for Roll-to-Roll Manufacturing of Eco-Friendly Flexible Hybrid Electronics. Appl. Nano 2025, 6, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano6040029

Ceron S, Barba D, Dominguez MA. Biodegradable 3D Screen Printing Technique for Roll-to-Roll Manufacturing of Eco-Friendly Flexible Hybrid Electronics. Applied Nano. 2025; 6(4):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano6040029

Chicago/Turabian StyleCeron, Sonia, David Barba, and Miguel A. Dominguez. 2025. "Biodegradable 3D Screen Printing Technique for Roll-to-Roll Manufacturing of Eco-Friendly Flexible Hybrid Electronics" Applied Nano 6, no. 4: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano6040029

APA StyleCeron, S., Barba, D., & Dominguez, M. A. (2025). Biodegradable 3D Screen Printing Technique for Roll-to-Roll Manufacturing of Eco-Friendly Flexible Hybrid Electronics. Applied Nano, 6(4), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/applnano6040029