1. Introduction

Hydrogen is increasingly recognized as a central element in the global transition to clean, sustainable energy. As a versatile, low-carbon energy carrier, it has considerable potential to reduce emissions across a wide range of industrial and transportation sectors [

1]. When utilized in fuel cells, hydrogen produces only water as a byproduct and offers substantially higher efficiency than conventional combustion-based systems. These attributes make it an appealing solution for enhancing both environmental sustainability and long-term energy security [

2]. Among the different fuel cell technologies, proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) have attracted particular attention due to their ability to operate at relatively low temperatures, deliver high power density in compact configurations, and rapidly respond to fluctuations in load demand. Such features make PEMFCs suitable for a broad spectrum of applications, including automotive, rail, and aerospace propulsion, as well as stationary, portable, and backup power generation [

3]. Their modular architecture also enables integration into both small-scale and distributed energy systems, while their compatibility with renewable sources contributes to grid stability and energy diversification [

4]. With continuous progress in cost reduction and hydrogen infrastructure development, PEMFC technology remains one of the most promising avenues for supporting a low-carbon, resilient energy future across multiple sectors [

5].

PEMFCs are inherently complex systems in which electrochemical reactions and various transport processes, such as the movement of hydrogen, oxygen, and water, are intricately coupled. To manage this complexity, researchers have developed mathematical models capable of replicating the cell’s behavior under a wide range of operating conditions. These models enable performance prediction, design exploration, and operational optimization without the expense and time associated with extensive experimental testing. Several notable modeling approaches have been reported in the literature: the empirical polarization model introduced in [

6], the mechanistic–empirical parametric formulation discussed in [

7], the variable-inclusive semi-empirical model presented in [

8], and the Simulink-based implementation described in [

9]. Among these, the seven-parameter model has become one of the most widely adopted frameworks for representing PEMFC voltage characteristics and performance across diverse operating conditions [

10,

11]. This model incorporates seven principal parameters, commonly denoted as

that describe activation and concentration losses, ohmic resistance, and other electrochemical phenomena occurring within the cell. Achieving accurate estimates of these parameters is critical, as it directly determines the model’s reliability for design, diagnostics, and control applications. When these parameters are carefully calibrated using experimental data and suitable optimization algorithms, the resulting models can reproduce real fuel cell behavior with high fidelity [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. However, determining these parameters remains a challenging task because of their strong nonlinear interdependencies, sensitivity to temperature, and humidity. As a result, advanced metaheuristic and machine-learning-based optimization techniques have gained prominence, offering effective means to overcome these challenges, improve predictive accuracy, and enhance the robustness of the seven-parameter model in practical engineering applications [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Heuristic and metaheuristic optimization algorithms have gained widespread attention in PEM fuel cell modeling, particularly for parameter estimation. These algorithms, often inspired by natural processes, animal behavior, and social interactions, are well-suited to address the nonlinear, high-dimensional nature of PEMFC models, which are typically difficult to solve using classical optimization methods [

19]. PEMFC models involve nonlinear relationships among current, voltage, and internal physical parameters, making analytical or direct parameter-estimation approaches impractical. Consequently, algorithms capable of efficiently exploring large search spaces are required to identify optimal parameter values. In [

15], the Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm enhanced with Lévy flight dynamics was employed to accurately estimate unknown PEMFC parameters. This approach effectively avoids entrapment in local minima, thereby improving global search capability. Similarly, the Spotted Hyena Optimizer, inspired by the cooperative hunting strategies of hyenas, has been applied to navigate the complex parameter space of PEMFC models [

20]. The Orthogonal Learning GOOSE Algorithm [

11] refines the classical goose optimization framework, improving both adaptability and robustness across diverse fuel cell operating scenarios. A hybrid Teaching–Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO) approach was proposed in [

21] for combined solar and PEMFC systems, demonstrating superior performance compared to earlier optimization variants. Additionally, the Wild Horse Optimizer introduced in [

22] was designed for adaptive PEMFC modeling that accounts for membrane degradation effects over time.

Recent advances in optimization techniques and machine-learning-assisted estimators have broadened the landscape of PEMFC parameter identification and degradation [

23]. Several deep-learning and hybrid metaheuristic approaches have reported improved prediction accuracy and adaptive capability under varying operating conditions. Examples include neural networks and probability-pool networks [

17,

18]; modern evolutionary optimizers such as the improved Walrus optimization algorithm (IWOA) [

24]; energy-guided neural models [

17]; a hybrid salp swarm algorithm with a chaotic system [

25]; the phototropic growth algorithm [

26]; the polar lights optimizer [

27]; eel foraging optimization [

28]; the training-imitation strategy and coronavirus mask protection optimizer [

29]; and the human-inspired optimization algorithm [

30]. These developments underline the increasing need for robust benchmarking frameworks.

By maximizing the agreement between simulated and experimental results, commonly through minimizing the sum of squared errors, these algorithms significantly enhance the quantitative accuracy of PEMFC models. With each new development, researchers continue to advance the boundaries of accuracy, convergence speed, and reliability, making PEMFC modeling increasingly capable of meeting real-world operational demands.

In this study, a novel application of the Cloud Drift Optimization (CDO) algorithm [

31] is introduced to determine the optimal parameters of the seventh-order steady-state PEMFC model. The motivation for employing CDO arises from its distinct advantages, which address several limitations commonly encountered in other metaheuristic algorithms:

- -

Adaptive balance between exploration and exploitation: The algorithm uses nonlinear control functions such as tanh and atanh to enable a smooth, adaptive transition between global exploration and local exploitation phases, thereby enhancing convergence stability.

- -

Dynamic weighting mechanism: CDO dynamically updates the weights of candidate solutions, promoting higher-performing “clouds” while maintaining population diversity. This strategy helps prevent premature convergence to suboptimal local minima.

- -

Probabilistic two-phase search: By integrating a global stochastic drift process with a locally focused refinement phase, CDO improves robustness and efficiency when dealing with multimodal objective functions.

- -

Competitive benchmark performance: Comparative studies have demonstrated that CDO frequently outperforms several state-of-the-art metaheuristics, such as the Harris Hawks Optimization, Marine Predators Algorithm, and Grey Wolf Optimizer, particularly in terms of convergence speed and solution quality.

- -

Proven versatility in engineering applications: Beyond fuel cell modeling, CDO has shown superior performance in structural engineering problems, including truss and cantilever beam optimization, spring design, and pressure vessel analysis, even under complex constraint-handling conditions.

The primary objectives of this paper are as follows:

- -

To apply the CDO algorithm for extracting the seven key parameters of the semi-empirical PEMFC model across three different commercial fuel cell stacks.

- -

To validate the accuracy and reliability of the CDO results by comparing them with published findings in the literature and by analyzing corresponding statistical performance measures.

- -

To implement the CDO algorithm on a Horizon 100 W PEMFC stack developed in an experimental setup at A’Sharqiyah University, evaluating its parameter estimation capability under both normal and degraded operating conditions.

2. Semi-Empirical Model of PEMFCs

The PEMFC-generalized steady-state electrochemical model developed by Mann and others [

32] offers several notable benefits over earlier approaches, particularly in its practicality, adaptability, and balance between theoretical and empirical elements. It is a general-purpose model, meaning it can be applied to a wide variety of PEM fuel cells regardless of differences in physical design or operating conditions—such as changes in active cell area, membrane thickness, temperature, pressure, or gas composition. Unlike older models designed for very specific cell types, this framework can be adjusted to fit different PEM configurations by using a range of design and operating parameters as inputs. Most of the terms used in the model are derived from physical principles, giving it both scientific meaning and predictive strength. This is especially clear in its treatment of voltage losses, which include activation, ohmic, and concentration polarization effects. Although the ohmic loss term is largely empirical, it maintains a semi-mechanistic structure, allowing calibration of the model to real operating conditions while still reflecting the underlying physics. Another strength of the model is its inclusion of a factor for membrane aging, which addresses the gradual decline in the membrane’s ability to transport water, an important issue in long-term PEMFC operation. Water management is further simplified by introducing a single semi-empirical parameter (λ) to describe membrane hydration. This approach provides both flexibility and accuracy, making it easier to fine-tune the model so it reflects the actual performance of working fuel cells. Concentration-voltage loss arises when reactant supply cannot keep up with consumption at the catalyst surfaces, leading to an additional voltage drop at higher currents. Although Mann’s model inherently includes effects related to reactant concentrations at the catalyst/membrane, in this paper, the concentration voltage loss is expressed explicitly as given in [

33,

34,

35,

36].

The stack voltage equation represents the maximum possible cell voltage, adjusted for temperature and reactant pressures. This equation is described by Equation (1).

where

is the number of stack cells,

is the thermodynamic potential,

is the activation voltage loss,

is the condensation voltage loss, and

is the ohmic voltage loss.

The thermodynamic potential is based on the Nernst equation for the O

2/H

2 fuel cell. Considering the standard entropy change, this equation is represented in Equation (2).

where

is the cell temperature,

is the hydrogen partial pressure, and

is the oxygen partial pressure.

The combined anode and cathode activation voltage loss is given by Equation (3).

where

to

are semi-empirical variables,

is the oxygen concentration defined by Equation (4), and

is the stack input current.

The ohmic voltage loss is given by Ohm’s law in Equation (5).

where

is the membrane resistance to protons, and

is the resistance to electron flow. The resistance

is unpredictable and unknown. The membrane resistance

can be represented by Equations (6) and (7).

where

is the membrane-specific resistivity,

is the stack current density,

is the membrane length, and

is the cell area. In Equation (6), the term

represents the specific resistivity at 303 absolute temperature and zero current density. The temperature correction factor is included in the exponential term; the other terms are empirical and are used for specific resistivity correction due to water content and cell temperature. The variable

is utilized for resistivity empirical correction for the effect of water content on current density and cell temperature.

Equation (6) describes hydration-dependent membrane resistivity but does not account for long-term chemical degradation, such as radical attack, peroxide formation, or fluoride emission, all of which increase membrane resistance over time. As a result, the model captures short-term hydration effects but may underestimate aging-related resistivity growth. Incorporating chemical-degradation kinetics or accelerated-aging corrections would offer a more complete representation of membrane deterioration.

Concentration voltage loss arises from reactant transport limitations at high current densities. Its effect is a sharp voltage drop, efficiency reduction, and possible long-term damage due to reactant starvation, particularly at high current densities. It can be expressed by Equation (8):

where

is the empirical variable introduced in the concentration voltage loss equation to bridge the gap between ideal theory and real-world PEMFC behavior, accounting for gas diffusion complexities, electrode microstructure, and operating conditions.

The parameters λ and B carry important physical interpretations. The hydration coefficient λ reflects the water content within the polymer membrane and directly influences proton mobility and ohmic resistance. Higher λ values correspond to increased water retention and lower membrane resistivity. The empirical mass-transport parameter B in the concentration overpotential term accounts for diffusion limitations within the gas diffusion layer (GDL), including the effects of pore microstructure, tortuosity, and liquid water saturation. Although treated empirically in this study, B indirectly represents the transport penalties associated with oxygen starvation and two-phase flow constraints. Recent work [

37] has shown that compression-induced porosity gradients within the GDL significantly alter water transport and gas diffusivity. It should also be noted that the thermodynamic representation in Equation (2) assumes constant activation energy for proton conduction. At lower temperatures (<60 °C), the membrane’s conductivity becomes more sensitive to temperature, and deviations from this simplified model may occur.

In reviewing the semi-empirical PEMFC model, seven uncertain parameters must be determined for accurate modeling, namely

to

, R

e, λ, and

. These parameters can be estimated from polarization curve data for a PEMFC. In such cases, heuristic optimization techniques can be employed to identify the parameters by minimizing the sum of squared errors between the model’s output voltage and the experimental data, as expressed in Equation (9).

where

is the objective function,

is the number of data points,

is the stack output voltage calculated from the model equations, and

is the data available from measurements.

3. Cloud Drift Optimization Algorithm

The CDO algorithm is a nature-inspired metaheuristic based on the dynamic behavior of clouds drifting under atmospheric forces. The goal is to minimize (or maximize) an objective function

over a bounded search space

:

where

and

are the lower and upper bounds of the solution vector

.

The initial population of

candidate solutions (“clouds”) is randomly distributed in the search space:

where

is a uniform random number between 0 and 1. This simulates the random initial positions of cloud particles. Each cloud’s dynamic weight

is updated based on its fitness relative to the best and worst solutions found so far:

where

is the best fitness so far,

is the worst fitness, and

prevents division by zero. This weighting scheme balances focus on better solutions and exploration.

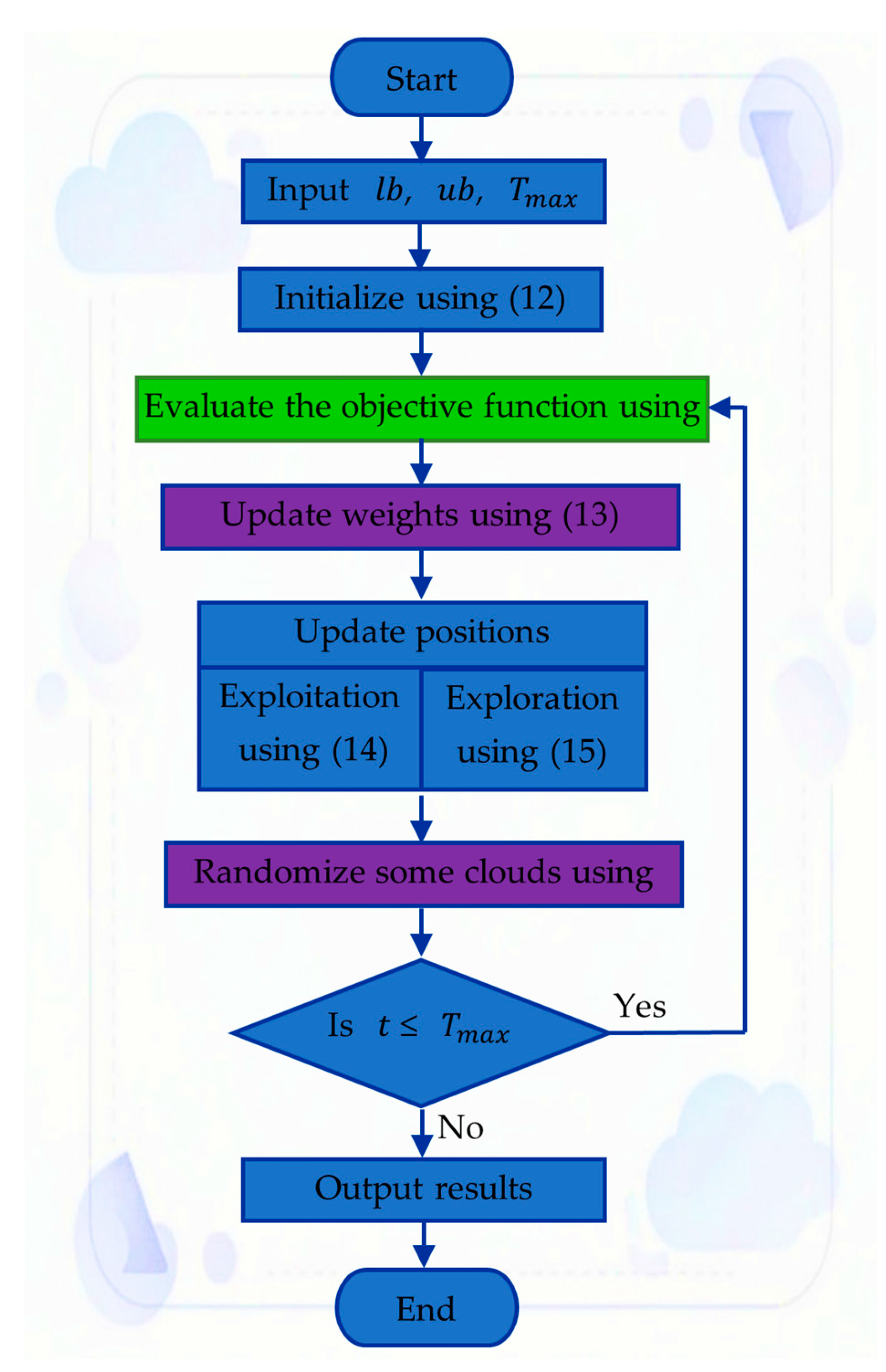

The position of each cloud is updated based on two phases, the exploitation phase (local refinement) and the exploration phase (global search). These two phases are described by Equations (13) and (14), respectively.

where

∼U (−0.2a, 0.2a) is a small random factor controlled by

,

is the current iteration, and

is the maximum number of iterations.

and

are positions of randomly selected clouds. This simulates the gradual local movement of clouds.

where

decreases over time from exploration to exploitation. This phase ensures diversity and escape from local optima. To avoid premature convergence, some clouds are randomly reinitialized with probability z decreasing over iterations:

In the CDO framework, the nonlinear control functions tanh and atanh play a central role in regulating the drift velocity and ensuring that the search naturally transitions from broad exploration to focused exploitation. During early iterations, the tanh argument remains small, so the function behaves almost linearly, allowing clouds to make relatively large moves across the search space. As the iteration count increases, tanh progressively saturates, compressing the effective displacement and encouraging localized refinement around promising regions. A similar effect occurs with atanh, which amplifies exploratory jumps when candidate solutions are far from the best cloud but becomes more conservative as the population converges. This nonlinear scheduling modulated through the evolution of the control parameter a prevents the search from collapsing prematurely around suboptimal minima. In addition, the re-initialization probability z, which decreases gradually over time, injects controlled diversity early in the run and preserves rare but meaningful opportunities to escape shallow basins. Together, these mechanisms produce the smooth exploration–exploitation transition that characterizes CDO and help explain its improved stability compared with classical heuristics such as PSO, which lack both nonlinear drift shaping and an explicit diversity-renewal mechanism.

As emphasized in the literature, exploration focuses on sampling previously unvisited regions to promote diversity, whereas exploitation intensifies the search around regions already identified as promising. If exploration dominates, convergence slows or becomes erratic; if exploitation dominates too early, the algorithm risks becoming trapped in local minima. CDO manages this balance by allowing the exploration phase Equation (15) to dominate during early iterations through wide, stochastic displacements, while the exploitation phase Equation (14) gradually becomes predominant as the nonlinear drift functions compress the step size. This controlled handover ensures a smooth progression from diversity-oriented search to convergence-oriented refinement, in line with the principles described in [

38]. The process of the CDO algorithm is illustrated by the flowchart in

Figure 1.

4. Test Cases

The performance of the proposed CDO approach is evaluated using three commercially available PEMFC systems. The primary objective is to benchmark CDO against a range of heuristic-based optimization methods reported in prior scientific literature. To ensure a comprehensive assessment under steady-state operating conditions, this study employs established and widely referenced commercial PEMFC units. To facilitate a rigorous analysis and establish a meaningful basis for comparison, the nominal specifications and datasheets of the three PEMFC stacks under consideration are presented in

Table 1 [

33,

34,

35]. The selected stacks include the 250-W, BCS 500-W, and Ned stack PS6 PEMFC units, all of which have been extensively examined in previous research. Additional technical details and performance characteristics can be found in studies, which provide further insights into these commercial systems. The comparative procedures are performed using MATLAB 2024 b on a system with an Intel(R) Core(TM) Ultra 7165U (2.10 GHz) processor and 32 GB RAM.

To ensure a fair comparison among all optimization algorithms, identical population sizes (100) and iteration limits (200) were used for CDO, PSO, and TGCOA unless noted otherwise. These settings follow the recommended configurations in the respective references and are commonly adopted in PEMFC parameter identification studies. All algorithms were executed under identical stopping criteria, search-space boundaries, and error metrics. This uniform setup ensures that the performance differences arise solely from the intrinsic characteristics of the algorithms, rather than differences in numerical tuning.

For each test scenario, CDO is executed across 20 independent runs, and statistical metrics, including minimum, maximum, average, and standard deviation, are compiled for each case study to assess robustness. The search space is limited to the lower and upper limits shown in

Table 2 [

33,

34,

35,

36].

The seven PEMFC parameters exhibit strong nonlinear coupling, as activation, ohmic, and concentration losses influence one another across different regions of the polarization curve. CDO mitigates these dependencies through a combination of physically informed bounds (

Table 2), evaluation of the objective function across the entire I–V range, and a population-based search strategy that maintains diversity long enough to explore multiple parameter combinations. Because the SSE penalizes mismatches in all three voltage-loss regimes—activation-dominated, ohmic-dominated, and mass-transport-dominated—unrealistic parameter “trade-offs” are naturally rejected by the objective function.

4.1. The 250-W PEMFC Stack

The 250 W PEMFC stack model has been investigated using various heuristic algorithms in numerous papers. Therefore, it is a good candidate for comparisons with CDO as summarized in

Table 3. These are the output results of the IWOA [

24], whale optimization algorithm (WOA) [

33], enhanced artificial hummingbird algorithm (EAHA) [

34], improved artificial ecosystem optimizer (IAEO) [

35], and the Jellyfish search algorithm (JSA) [

39]. CDO converged to the minimum objective of 0.33138 among all challenging optimizers. Although the IAEO algorithm has a zero standard deviation (St. D.), it is stocked at a local minimum of 0.336.

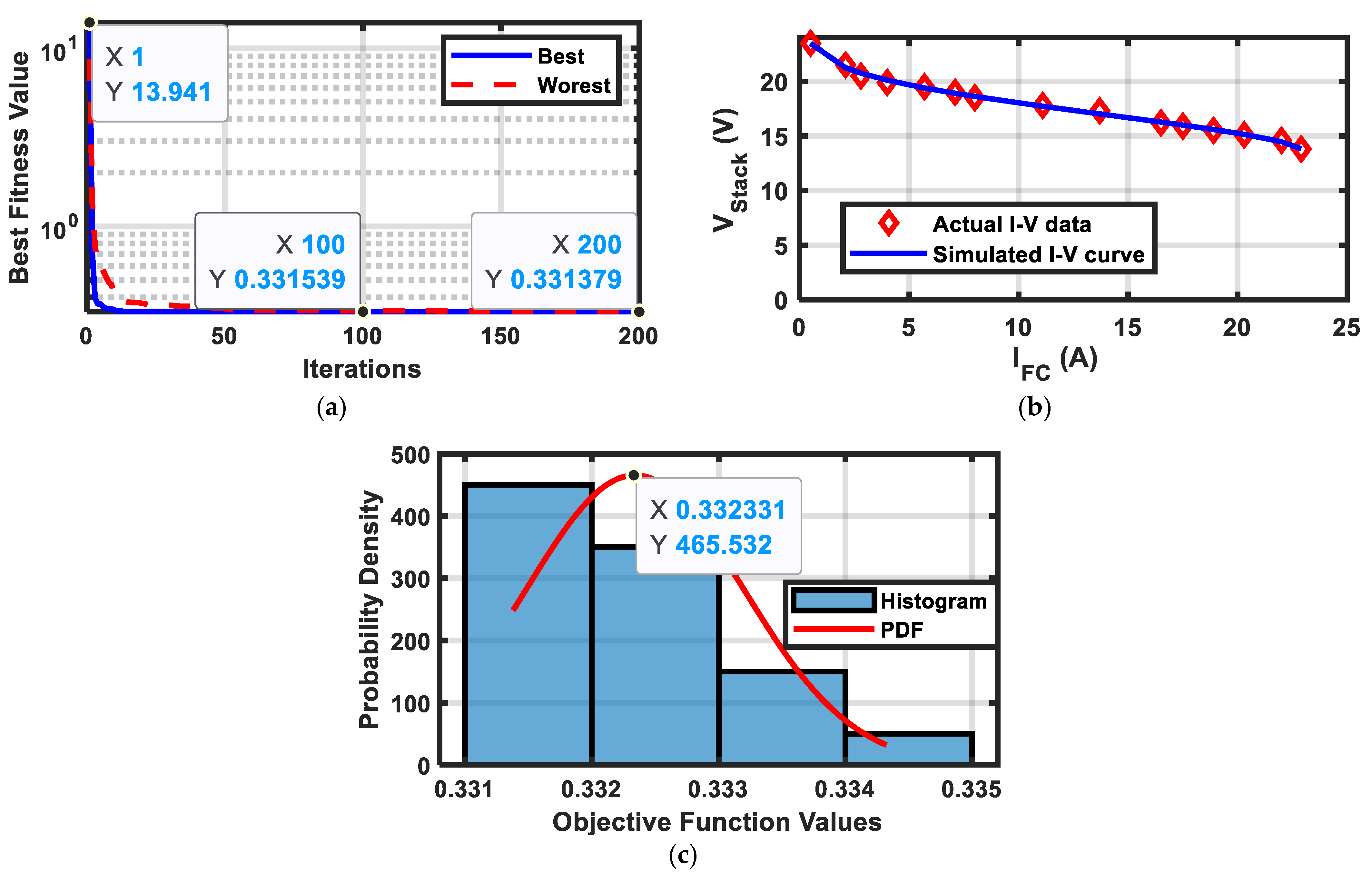

Figure 2a illustrates the convergence behavior of the CDO algorithm, showing the best and worst trials among 20 runs. The initial SSE of 13.941 is reduced to 0.3315 after 100 iterations and further decreased to 0.331379 after 200 iterations. This small SSE is reflected in

Figure 2b, where a clear agreement between the model’s I–V curve and the actual data can be observed.

Figure 2c shows a histogram with a probability density function (PDF) fit; it illustrates how frequently different values of the objective function occur in the dataset. The red curve shows the theoretical probability density for that distribution. The maximum PDF value occurs at the mean of 0.3324, and its high value of 465.532 reflects how tightly the data are clustered around the mean, with a small St. D. of 0.0008569.

Among the elements contributing to CDO’s performance, the dynamic weight update in Equation (13) is especially important for robustness. By normalizing each cloud’s fitness relative to the current best and worst solutions, the algorithm consistently recenters the search around the most promising region while still retaining a minimum degree of diversity. This adaptive focusing mechanism, combined with the stochastic global drift term, plays a key role in producing the notably small standard deviations observed across the 20 independent runs, demonstrating that CDO is highly repeatable and less susceptible to run-to-run variability.

4.2. The BCS 500-W PEMFC Stack

The BCS 500-W PEMFC stack is designed to deliver a nominal power output of 500 watts, comprising 32 cells with a total active area of 64 cm2 per cell. It operates at a nominal voltage of around 19 V and a current of approximately 26.3 A, with a maximum current capacity close to 30 A.

The stack functions optimally within a temperature range of 25 to 65 °C, with hydrogen partial pressure approximately 1 atm and oxygen partial pressure approximately 0.2095 atm. The cropped results of some challenging optimizers found in the literature for this stack are summarized in

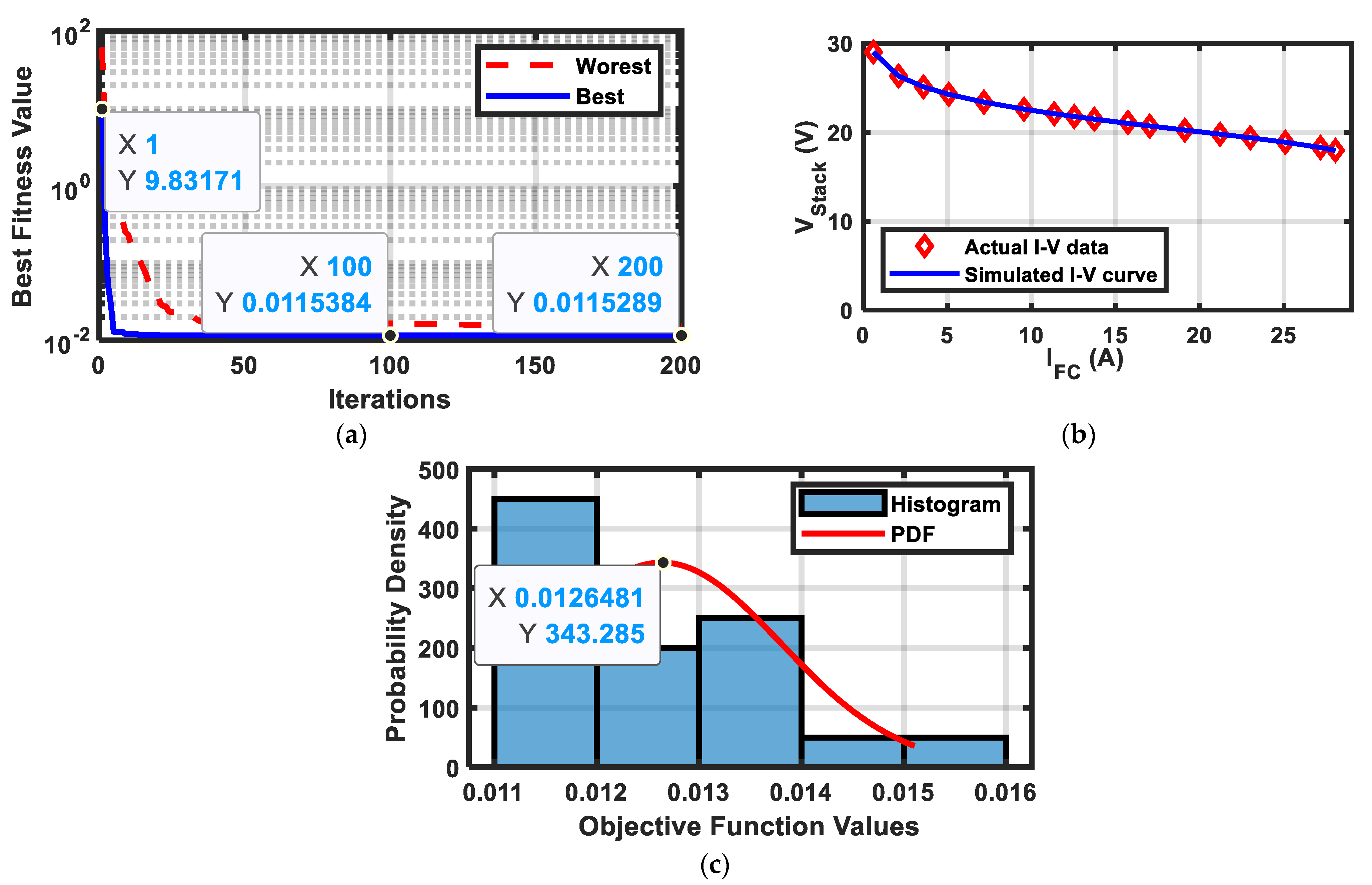

Table 4. The CDO algorithm reached a minimum SSE of 0.011529, which is the smallest among other heuristic optimization methods. The convergence curve in

Figure 3a confirms the capability of the CDO algorithm to approach the minimum objective within 200 iterations.

Figure 3b shows a strong agreement between the model output and the test data. Although in some of the 20 trials the algorithm was trapped in a local minimum, as illustrated by the worst case in

Figure 3a, in most trials it successfully reached the global minimum, as evidenced by the histogram and probability density function (PDF) in

Figure 3c. The figure demonstrates that the algorithm converges reliably near 0.0126, with high probability density, confirming its effectiveness in finding the minimum objective function.

4.3. The Ned Stack PS6 PEMFC Stack

The Ned Stack PS6 PEMFC stack is a high-performance PEMFC system rated at 6 kW. It is designed to operate within a temperature range of 343.15–353.15 K and can handle maximum currents up to 225 A, with operating voltages ranging from 32 to 60 V depending on the load. For operation, the stack uses hydrogen and air as reactants. The partial pressures of hydrogen and oxygen are each typically set at 1.0 bar during standard operating conditions for laboratory and model validation purposes. This model is widely adopted in both research and industrial applications for fuel cell performance evaluation, optimization, and steady-state modeling.

Table 5 presents the results obtained from the compared optimization algorithms. However, it should be noted that in [

34], the EAHA method was not applied to the NedStack PS6 PEMFC. The CDO achieved an SSE of 2.10025 after 200 iterations, whereas the IWOA reached an SSE of 1.955 after 2000 iterations. Moreover, the population size and standard deviation used for IWOA are not reported in [

24]. The CDO outcome is further illustrated in

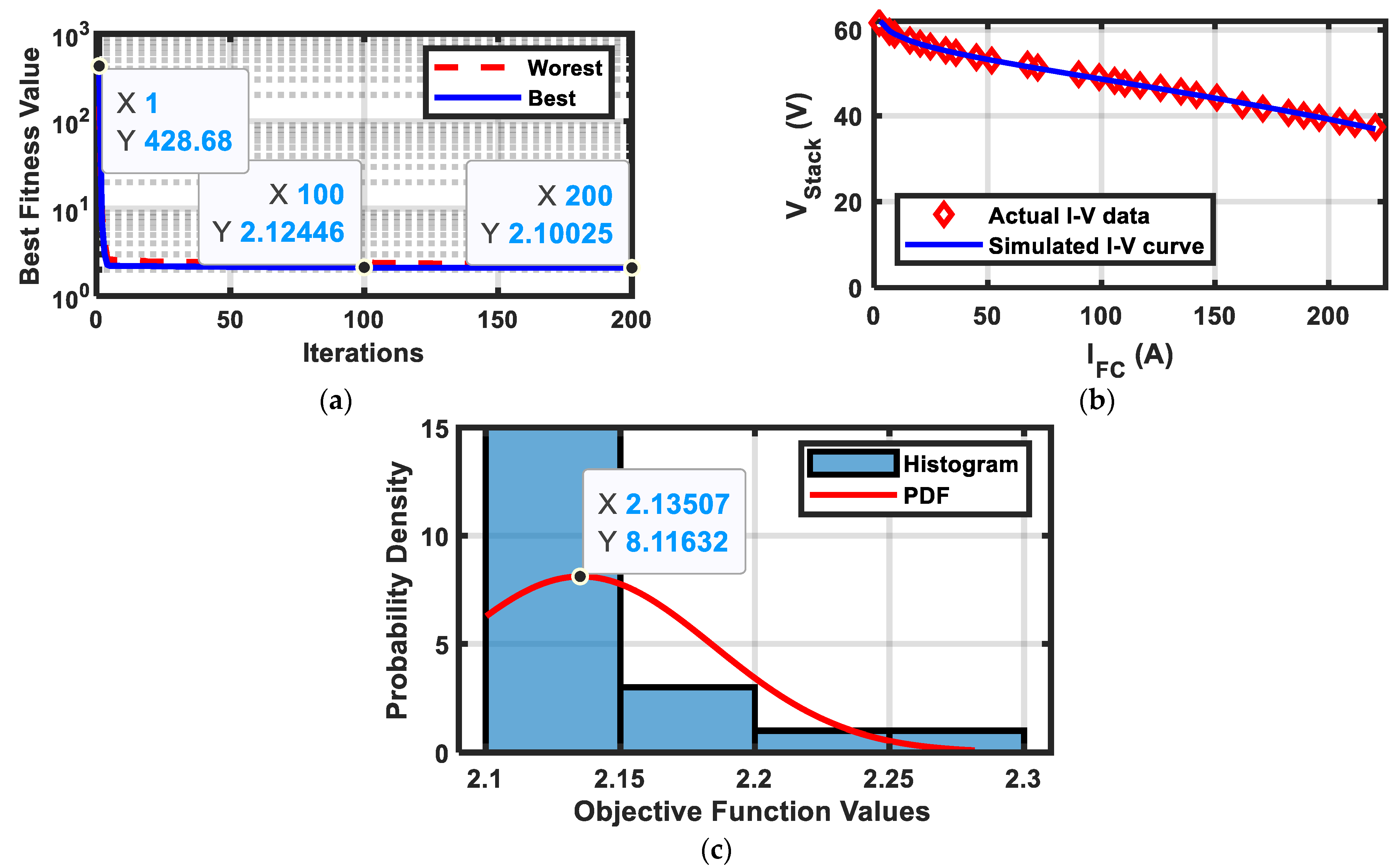

Figure 4a, where the initial SSE of 428.68 was reduced to 2.0025 after 200 iterations.

Figure 4b shows the model I-V output curve, which closely matches the actual I–V dataset.

Figure 4c indicates that the optimization algorithm consistently converged around an objective function value of 2.13507, which represents its most likely performance across the trials. Moreover, most of the results of the 20 runs lie near to this minimum error, as illustrated in

Figure 4c.

4.4. The Horizon 100-W Experimental Setup

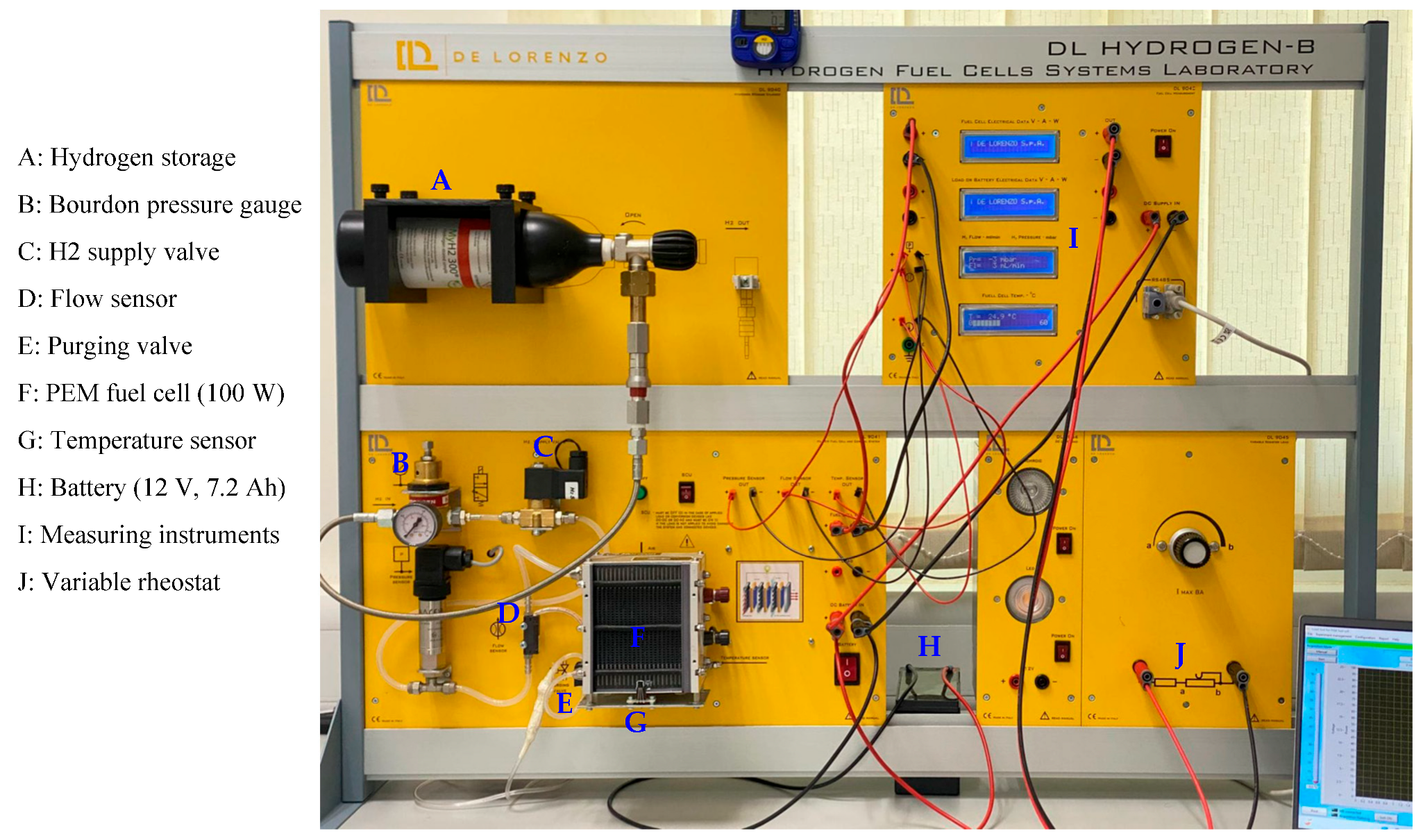

The primary objective of this case study is to validate the effectiveness of the CDO algorithm in accurately identifying the unknown parameters of a Horizon100 W PEMFC stack available in our laboratory.

Figure 5 illustrates the experimental setup of this stack, which is located in the Renewable Energy Laboratory, Faculty of Engineering, A’Sharqiyah University, Oman. Two experimental datasets were recorded for this stack: the first was obtained when the stack was in normal conditions, and the second was collected after the stack had been left idle for a few months. It was observed that the output power deteriorated significantly after this idle period. Hence, this condition presents a valuable opportunity to investigate and identify the stack parameters under degraded performance.

In the experimental setup shown in

Figure 5, the purging valve mounted on the anode outlet is used to prevent anode flooding and ensures that hydrogen reaches the catalyst with adequate purity, thereby improving measurement stability during the I–V sweeps. The hydrogen flow rate is monitored through an in-line flow sensor (accuracy ±5%) positioned between the supply valve and the stack inlet, while the stack temperature is measured using a surface-mounted LM35 sensor with ±0.25 °C at room temperature and ±0.75 °C over a full temperature range (−55 °C to 150 °C) attached near the central cells. Both sensors are connected to an integrated data-acquisition board located within the measuring instruments module, which records the flow, temperature, current, and voltage signals. All sensors were calibrated by De Lorenzo.

4.4.1. The Horizon 100-W Stack at Normal Conditions

The Horizon 100 W PEMFC stack operates at a temperature of 25 °C and a standard pressure of 0.5 bar. During the tests, the fuel cell was progressively loaded up to 9.29 A. The hydrogen pressure was regulated using a pneumatic valve and monitored with a pneumatic gauge, while a thermometer was positioned on the PEMFC to record the stack temperature. The main technical specifications of the stack are as follows: 20 series-connected cells, an active area of 20 cm

2, a membrane thickness of 36 µm, a maximum current density of 0.55 A/cm

2, a fuel cell temperature of 298.15 K, a hydrogen partial pressure of 0.5 atm, and an oxygen pressure of 1 atm. To validate the CDO algorithm, the well-established particle swarm optimizer (PSO) [

40] and the recently developed tetragonula carbonaria optimization algorithm (TGCOA) [

41] are applied to extract the 100-W stack parameters.

For this experiment, I–V characteristic measurements were collected under steady-state operating conditions, as summarized in

Table 6. The final objective values obtained with CDO from these runs were highly consistent, with a standard deviation of 1.2114 × 10

−7, confirming the algorithm’s robust performance. The best convergence behavior is illustrated in

Figure 6a, where the CDO convergence is monotonic and fast; it started randomly with an SSE of 3.092, the largest SSE among the three algorithms; however, it converged to the smallest SSE.

Figure 6b shows the excellent agreement between the experimental and modeled data, with a minimum SSE of 1.037 across 28 I–V points, as recorded in

Table 7. The histogram and PDF in

Figure 6c show tight concentration around the optimum SSE, again verifying algorithmic precision. The boxplot in

Figure 6d demonstrates the lowest median error and variance for CDO, followed by PSO, with TGCOA showing the widest spread.

Table 7 indicates that the St. D. of CDO and PSO are very small so that they achieved extremely low variance, confirming high convergence consistency and robustness with respect to the TGCOA.

4.4.2. The Horizon 100-W Stack with Degraded Performance

This case study shows the cropped results by CDO when the Horizon 100-W stack is left without use for a few months. The term “degraded performance” in this study refers to the clear performance deterioration observed after the stack remained unused for several months. The most prominent indicator was a reduction of nearly 50% in the maximum achievable output power compared to the normal operating state. Additionally, the polarization curve exhibited a steeper slope at moderate and high current densities. Although membrane thickness, catalyst surface area loss, and ionomer decay were not measured directly, these electrical signatures provide a widely accepted practical means for identifying degradation in PEMFC research.

The I–V measured pairs are represented in

Table 8. The extracted parameters along with the statistical measures are presented in

Table 9. CDO and PSO algorithms reached almost the same minimum objective value with a very small St. D. of the 20 trials. The convergence trend of the three algorithms is shown in

Figure 7a; although the CDO started with the largest SSE of 2.616, it converged to the minimum SSE of 0.44707. PSO almost has the same performance as CDO, while TGCOA has fewer statistical measures. Alignment between model and measured data is illustrated in

Figure 7b. The histogram/PDF indicates convergence toward a stable minimum for CDO, confirming robustness under degraded conditions as shown in

Figure 7c.

The higher concentration-loss parameter B, compared with normal conditions, suggests stronger mass-transport limitations, potentially arising from pore blockage, altered water saturation profiles, or microstructural changes within the GDL.

5. Discussion

The membrane resistivity formulation used in this study follows the classical Mann-type hydration-based model. While this model captures the dominant effect of water content on membrane conductivity, it does not explicitly include chemical degradation pathways such as free-radical attack, peroxide formation, or fluoride emission. Including corrections based on accelerated aging tests or chemical-degradation kinetics would provide a more comprehensive representation of long-term membrane health and is noted here as a worthwhile future enhancement. It is important to acknowledge that several PEMFC parameters, particularly activation and concentration-loss coefficients, are not strictly constant over the lifetime of the stack. Transient hydration cycles, catalyst accessibility changes, and gas-diffusion effects can lead to reversible voltage recovery phenomena. Recent studies on fuel cell life prediction have demonstrated that part of the voltage loss can rebound when operating conditions are restored to optimal hydration and temperature levels. This creates a natural link between parameter drift and reversible degradation.

Incorporating such recovery-aware models with CDO-extracted parameters represents an important direction for future research, especially for long-term forecasts and online health assessment. Although CDO demonstrates strong convergence behavior and low variance, the current work focuses on offline optimization. Real-time implementation on embedded hardware was not tested and is identified as an avenue for future development.

The CDO-identified parameters naturally support health-state estimation frameworks based on polarization-loss decomposition, as each parameter maps directly to activation, ohmic, or concentration losses. Monitoring their evolution over time provides a compact and physically meaningful representation of stack health, consistent with recent model-based approaches that quantify degradation by separating the underlying loss mechanisms. Although the present work focuses on steady-state extraction, extending CDO to dynamic identification introduces additional challenges due to the need to capture time-dependent species transport, thermal behavior, transient water dynamics, and hysteresis, all of which increase computational complexity within iterative optimizers. Multi-objective formulations such as jointly optimizing efficiency, durability, and cost further require Pareto-based or scalarized strategies. A practical pathway forward is to use CDO offline to estimate slowly varying or degradation-related parameters, while relying on online learning methods, observers, or model predictive control to track fast dynamics. Such CDO online-learning schemes offer promising opportunities for real-time diagnostics, monitoring, and life-prediction applications in PEMFC energy management systems.

6. Conclusions

This paper introduced a robust optimization-based framework for the accurate estimation of PEMFC model parameters, supported by extensive experimental validation. The CDO algorithm was applied to extract seven key parameters of the semi-empirical PEMFC model across several commercial and laboratory fuel cell stacks. The proposed method was applied to three known commercial stacks, namely the 250 W, BCS 500 W, and NedStack PS6 PEMFC units, as well as an experimentally tested Horizon 100 W stack developed in A’Sharqiyah University’s Renewable Energy Laboratory. Compared with other challenging metaheuristic algorithms such as PSO, TGCOA, EAHA, IAEO, and JSA. The proposed method consistently achieved faster convergence, smaller objective function values, and superior stability. For the 250-W PEMFC stack, the CDO algorithm yields an SSE of 0.33138 and an SD of 0.0008569; for the BCS 500-W PEMFC stack, SSE and SD are 0.011529 and 0.001162, respectively; for the Ned Stack PS6 PEMFC, SSE and SD are 2.10025 and 0.049152; and for the Horizon 100 W PEMFC stack, SSE and SD are 1.0337 and . The experiments conducted on the Horizon 100 W PEMFC stack under both normal and degraded conditions confirmed that the CDO algorithm not only maintained precise parameter estimation but also effectively captured the deterioration in stack performance. These results, supported by statistical analysis and visual validation through polarization and convergence plots, demonstrate that CDO is both accurate and repeatable. It cannot be claimed that CDO is globally optimal across all estimator types reported in the literature; CDO remains a steady-state, physics-guided optimizer whose performance is tied to the underlying semi-empirical model and the polarization data used for calibration.