A Novel Recurrent Neural Network Framework for Prediction and Treatment of Oncogenic Mutation Progression

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Prior Research

1.1.1. Biological Research

1.1.2. Time-Series Analysis and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

1.1.3. Deep Learning for Genomics

1.2. Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

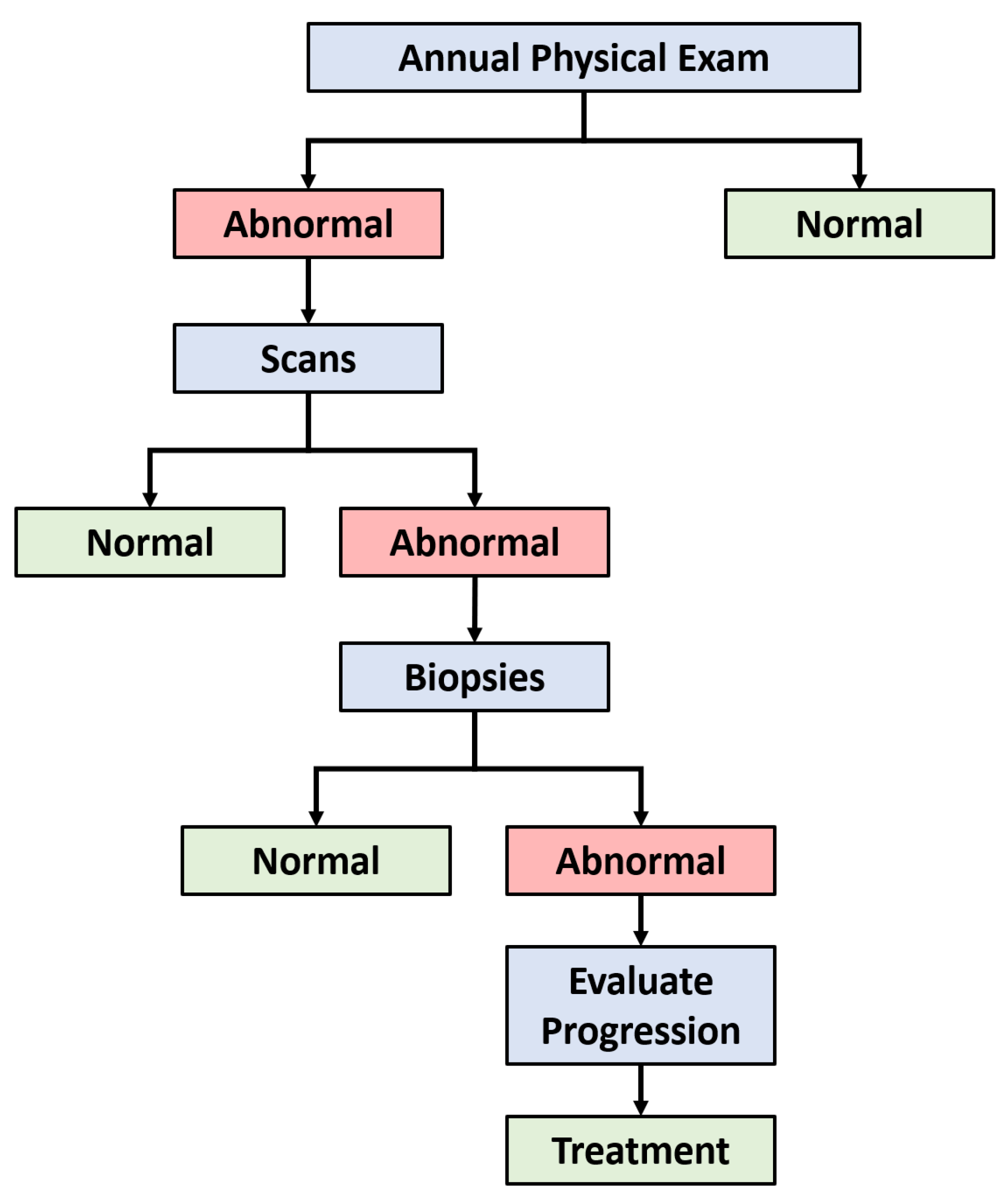

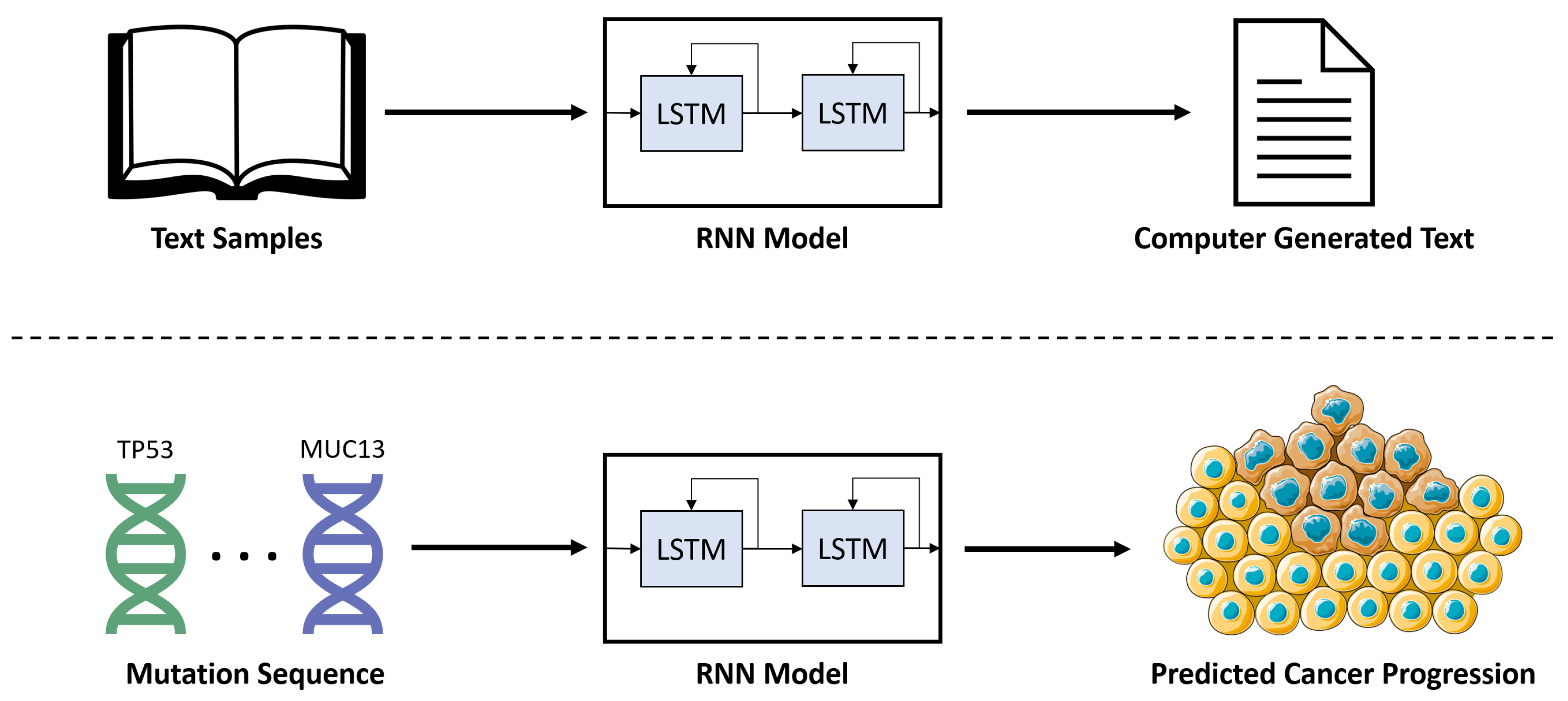

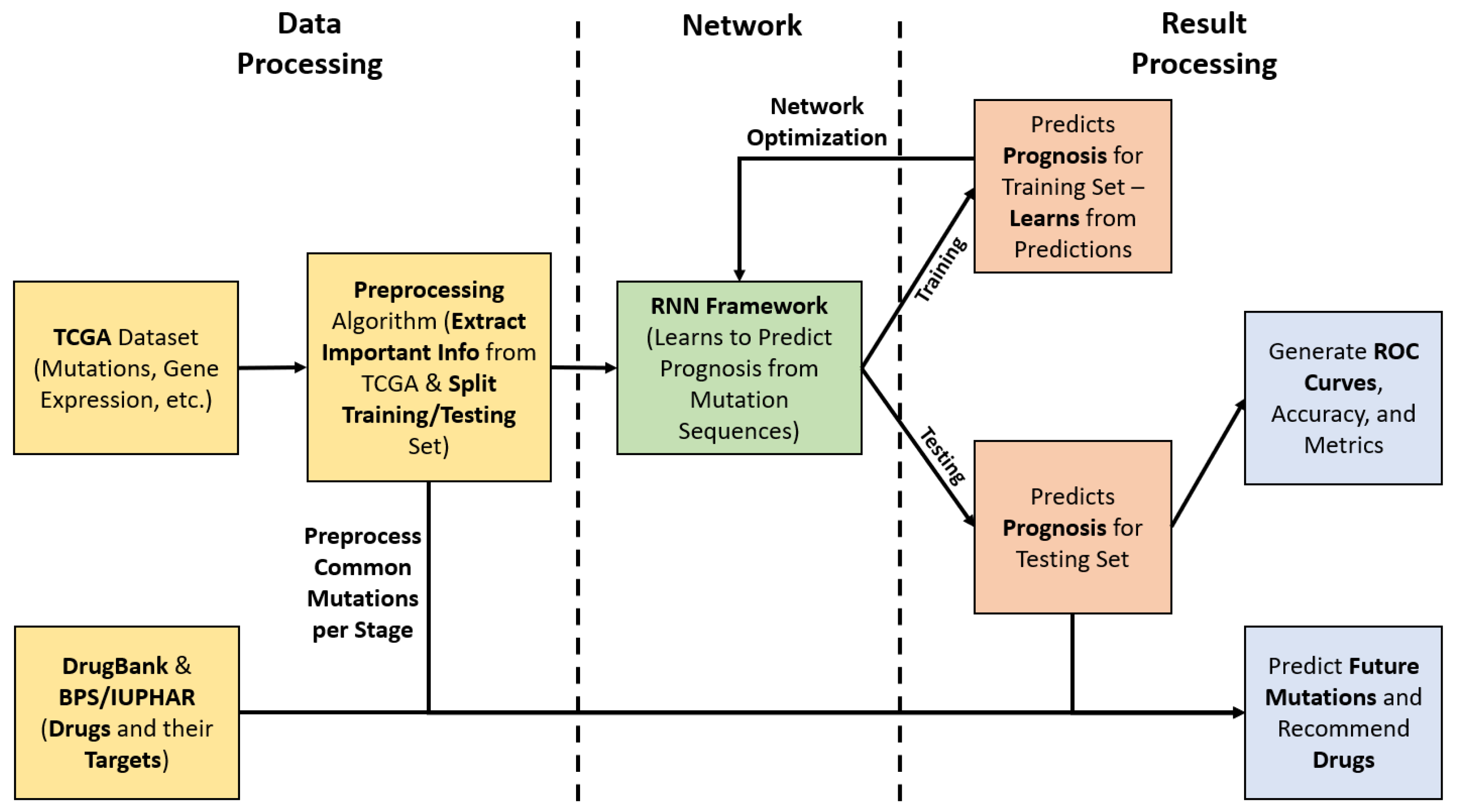

2.1. End-to-End Framework

2.2. Dataset

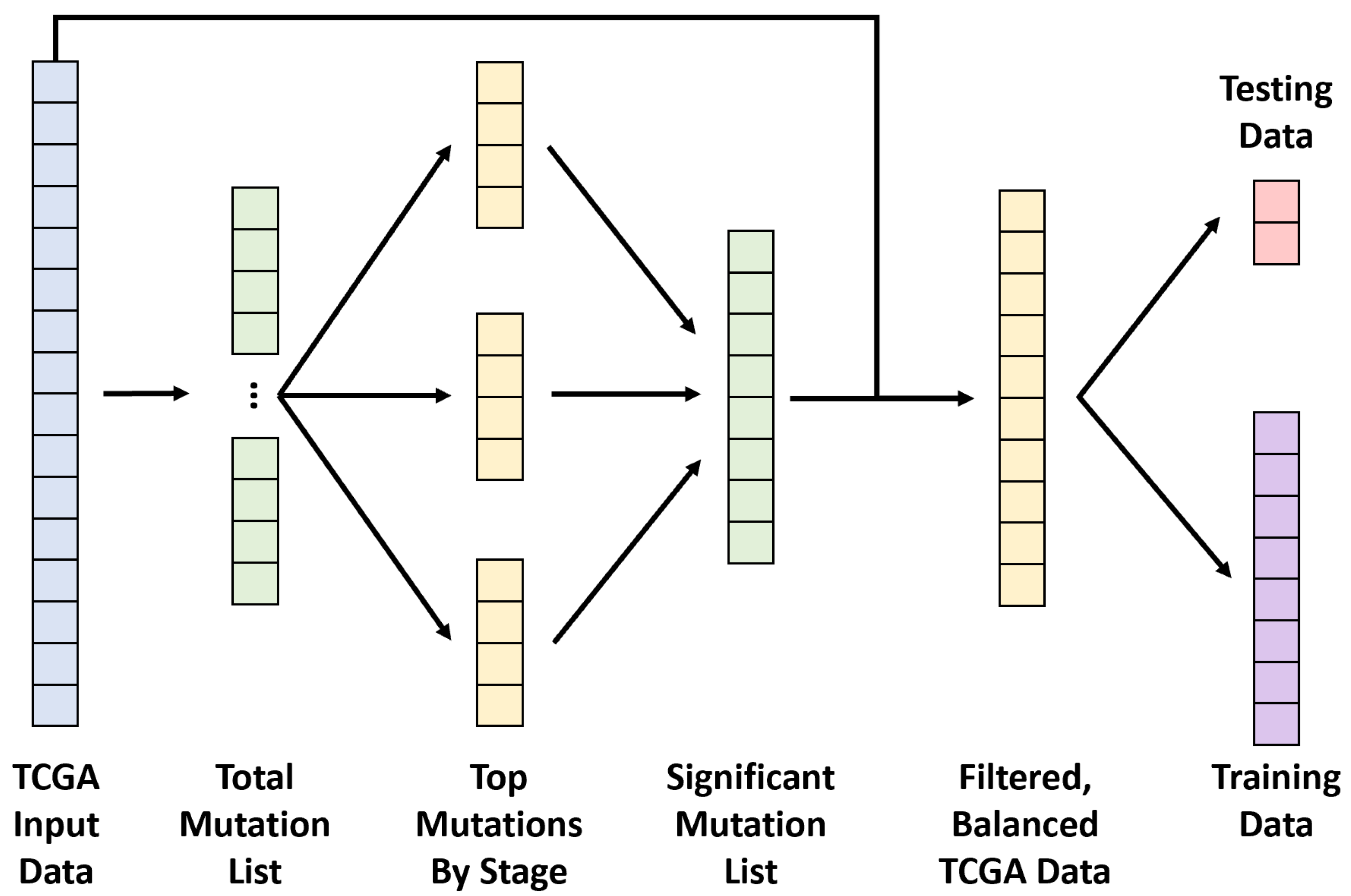

2.3. Data Preprocessing

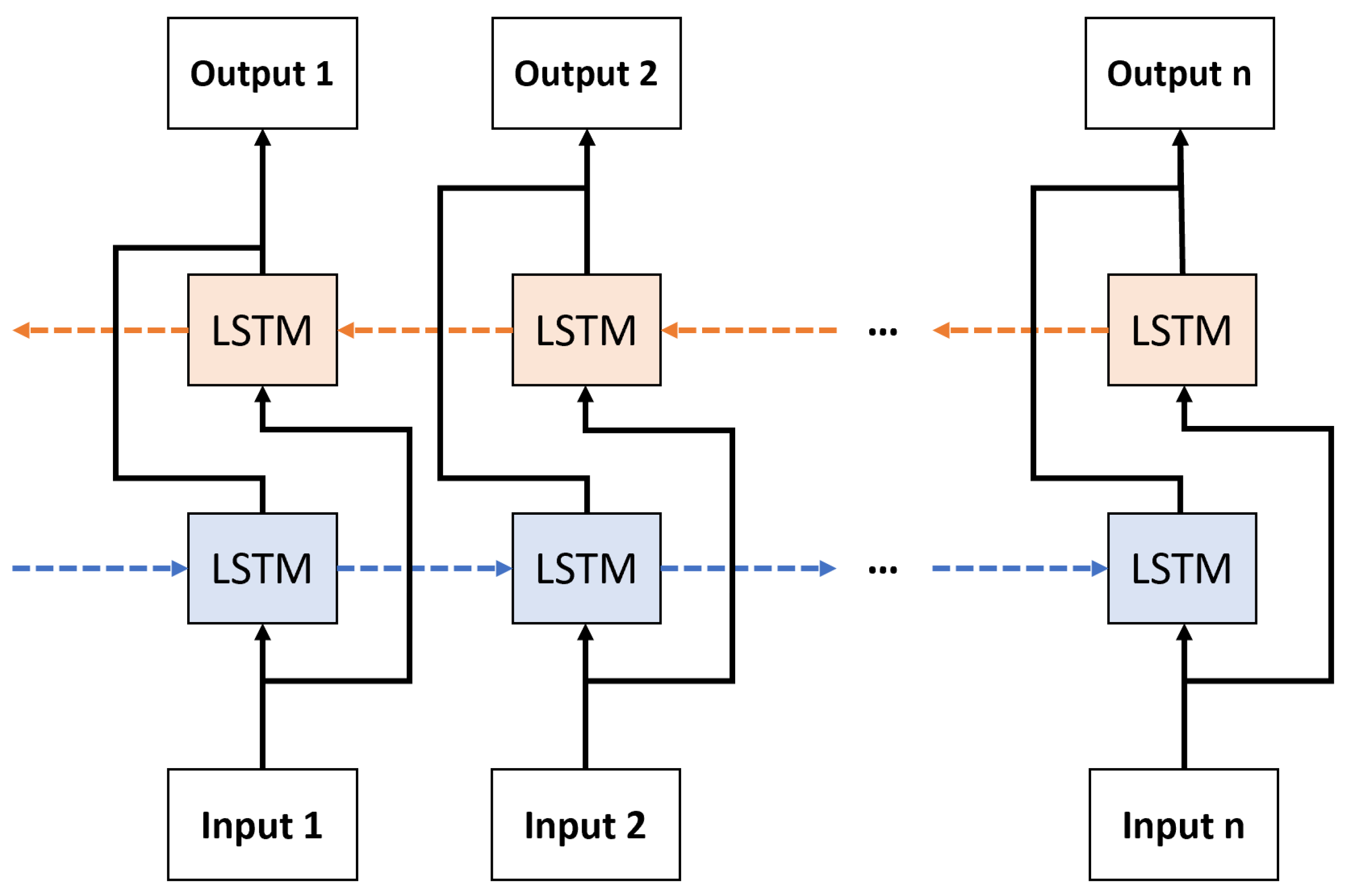

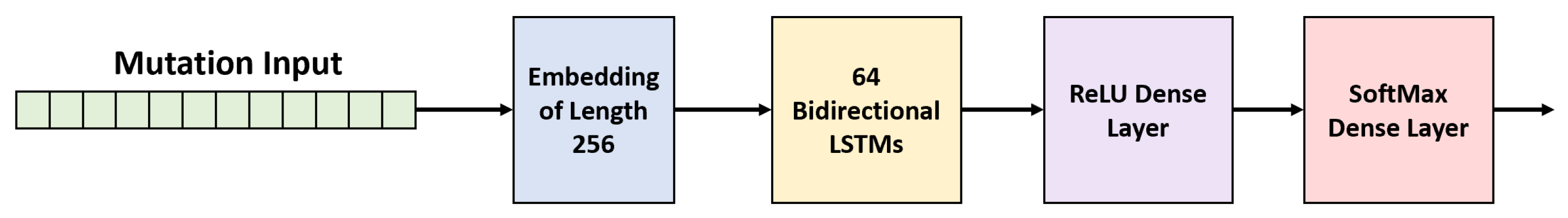

2.4. Recurrent Neural Network (RNN)

2.5. Experimental Setup and Implementation

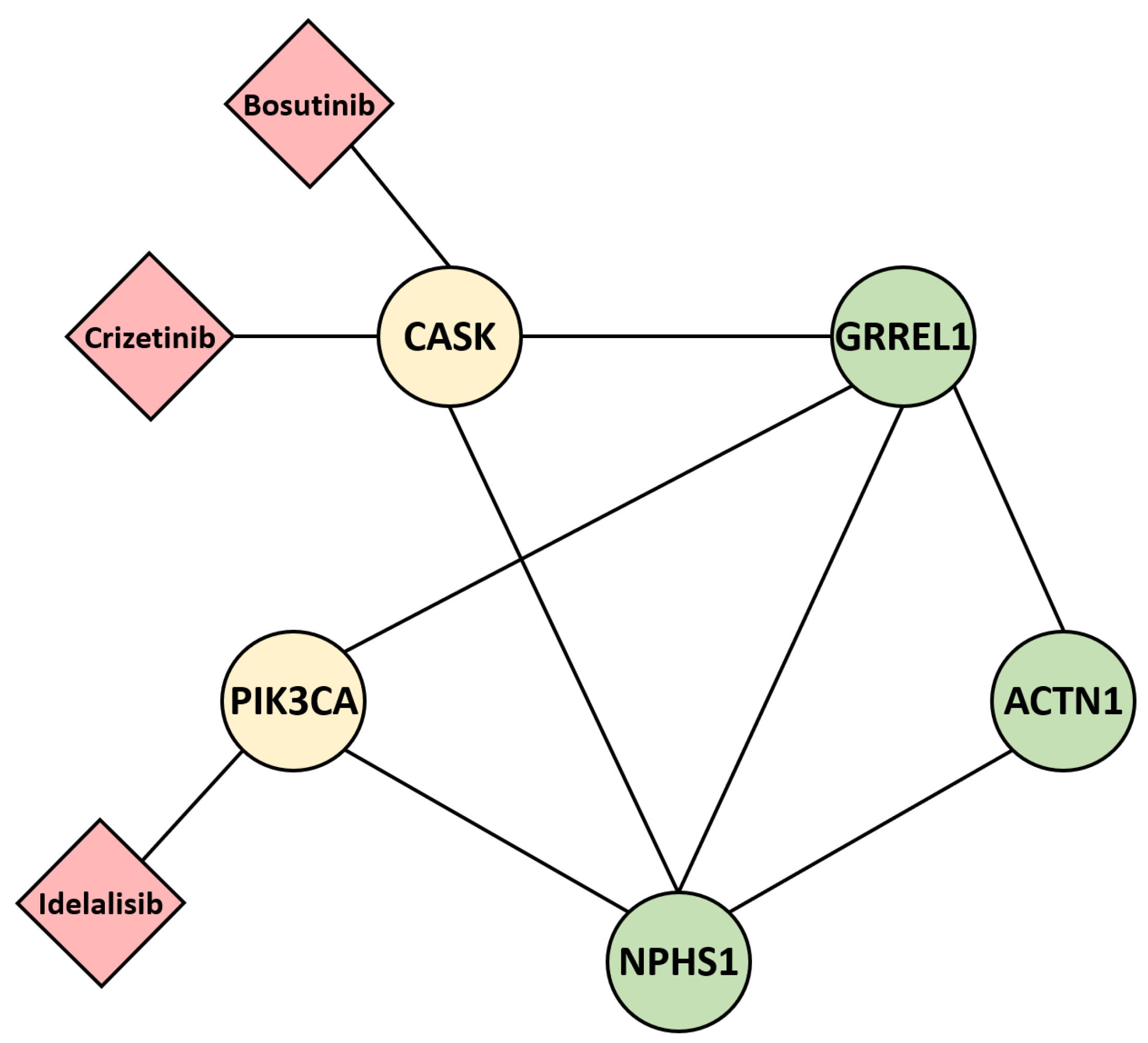

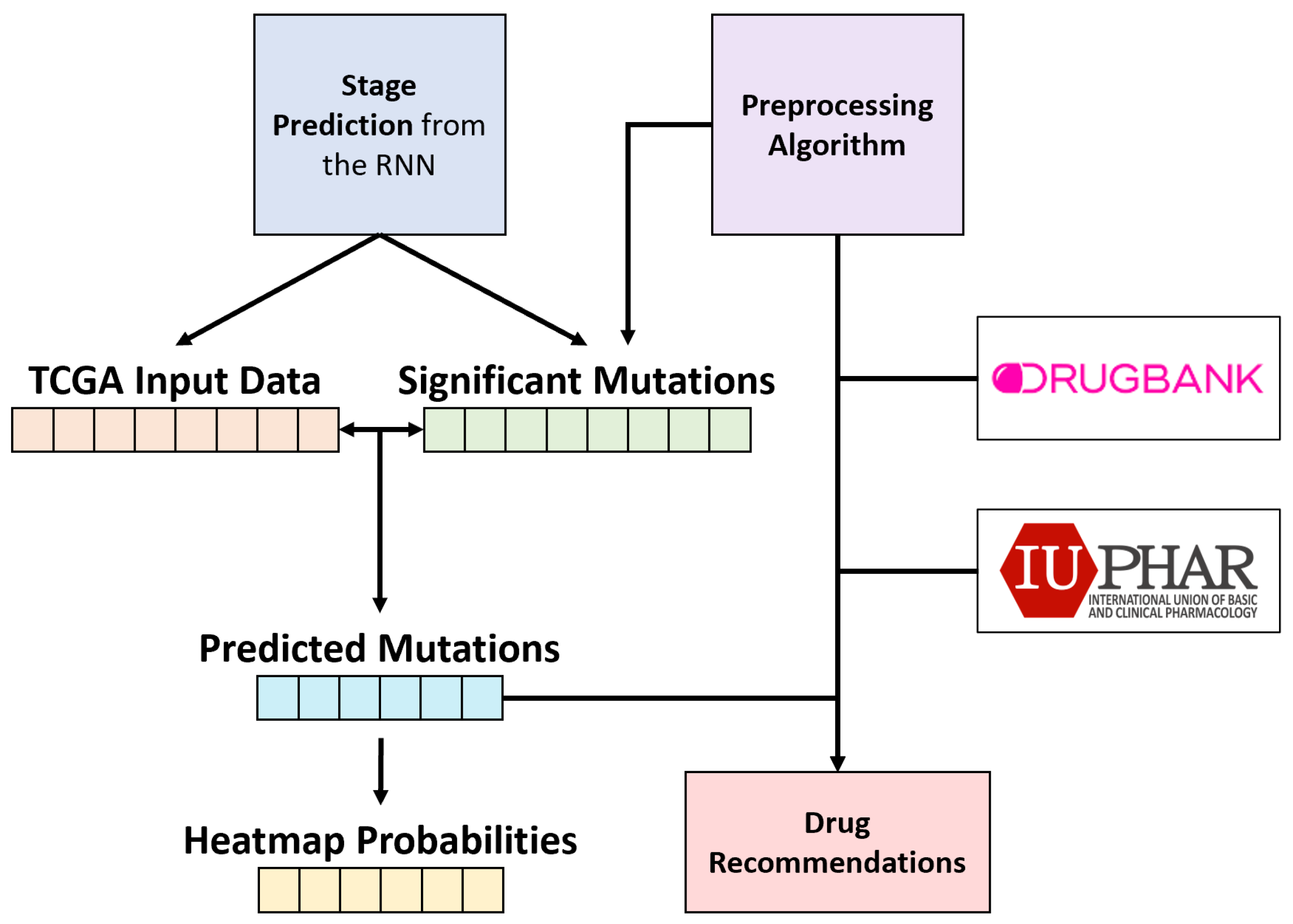

2.6. Post Hoc Gene–Drug Prediction

3. Results

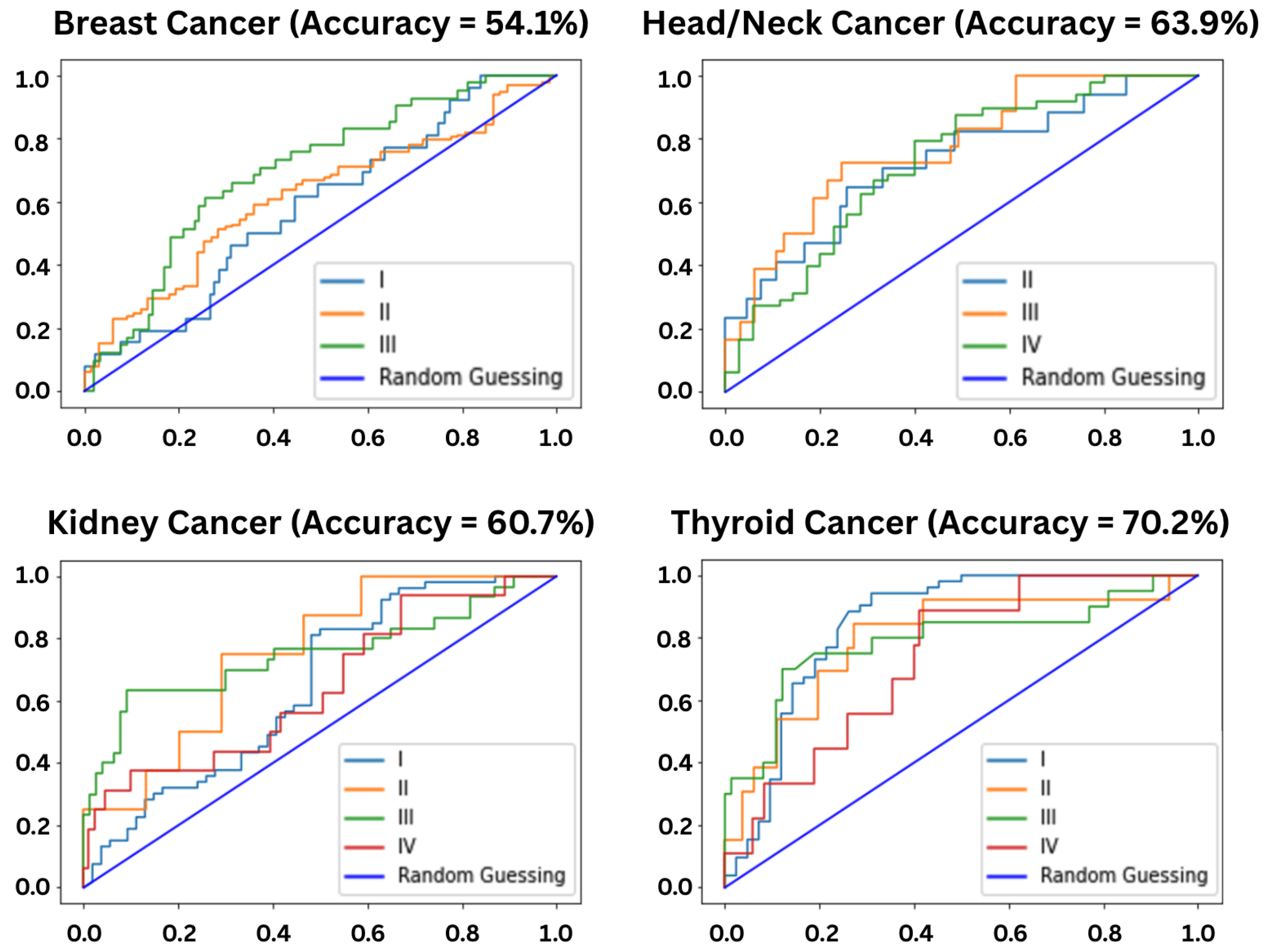

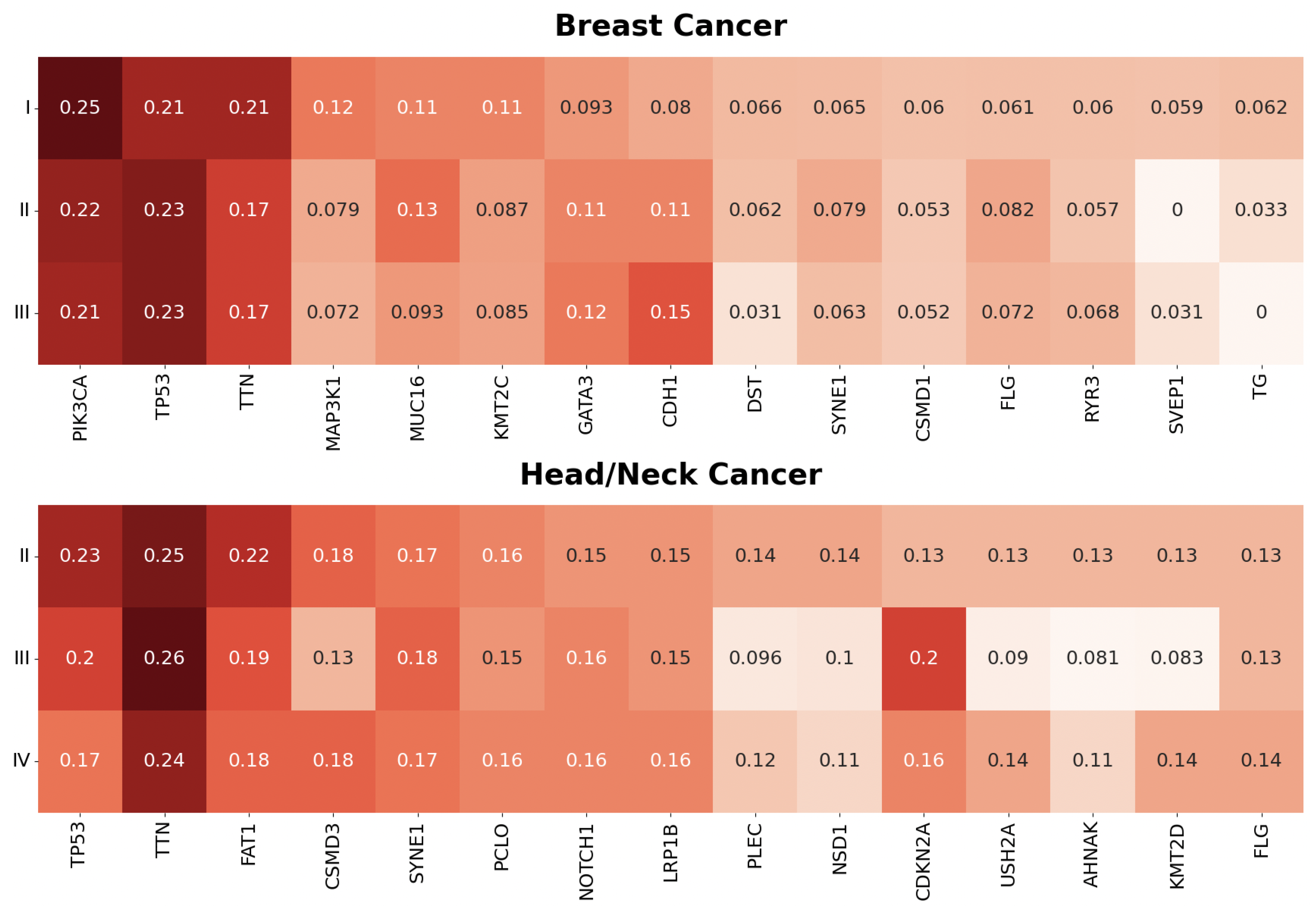

3.1. Stage Predictions

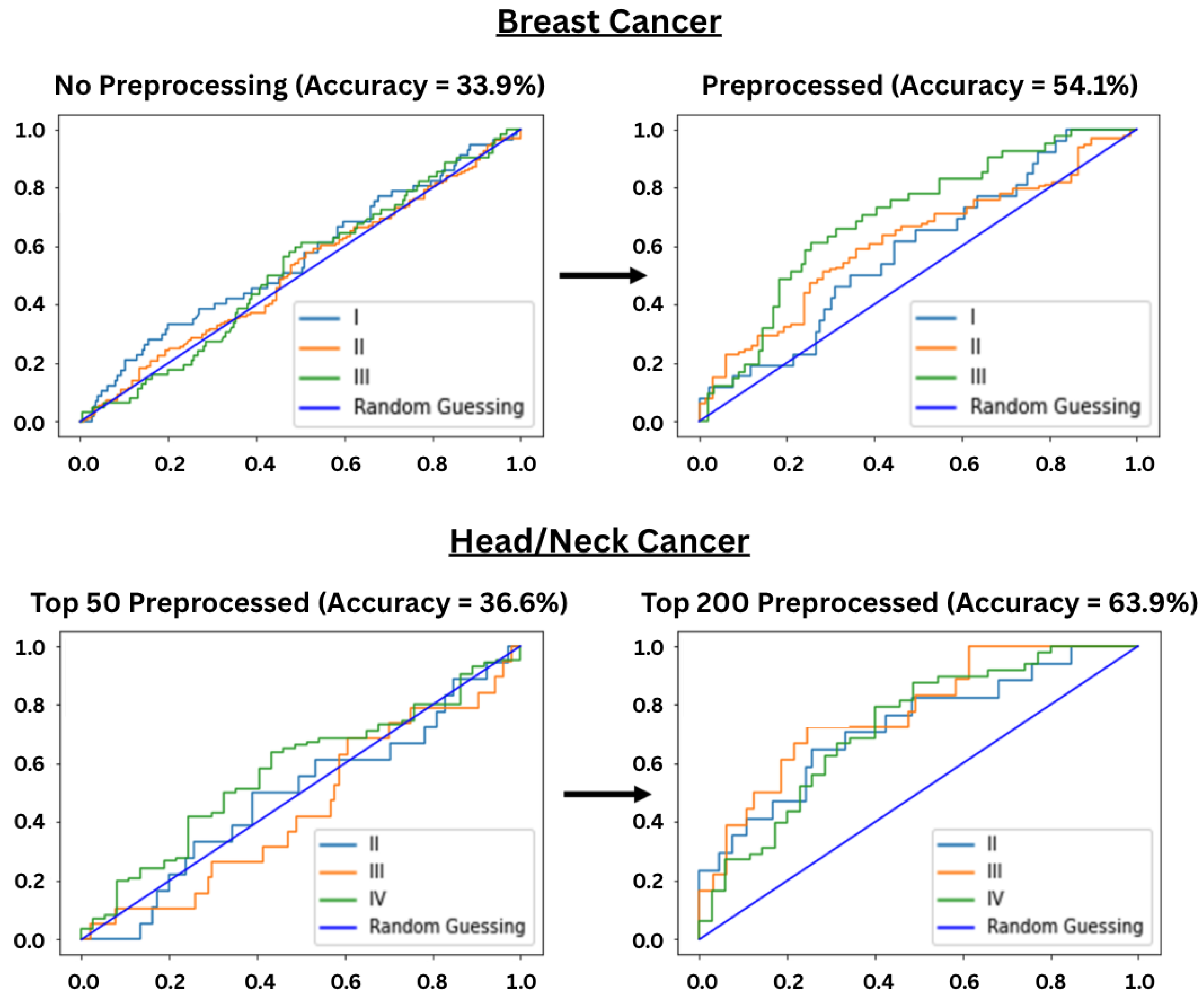

3.2. Preprocessing Performance

4. Discussion

Limitations of Stage-Based Prediction

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housman, G.; Byler, S.; Heerboth, S.; Lapinska, K.; Longacre, M.; Synder, N.; Sarkar, S. Drug resistance in cancer: An overview. Cancers 2014, 6, 1769–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggio, A.I.; Varley, K.E.; Welm, A.L. The lingering mysteries of metastatic recurrence in breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P.; Sunkara, T.; Gaduputi, V. Epidemiology of Pancreatic Cancer: Global Trends, Etiology and Risk Factors. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonorezos, E.S.; Barnea, D.; Moskowitz, C.S.; Chou, J.F.; Sklar, C.A.; Elkin, E.B.; Wong, R.J.; Li, D.; Tuttle, R.M.; Korenstein, D.; et al. Screening for thyroid cancer in survivors of childhood and young adult cancer treated with neck radiation. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Wilcox, W.R. Changing paradigm of cancer therapy: Precision medicine by next-generation sequencing. Cancer Biol. Med. 2016, 13, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chougrad, H.; Zouaki, H.; Alheyane, O. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for breast cancer screening. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2018, 157, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, R.; Chang, P.; Mema, E.; Mutasa, S.; Karcich, J.; Wynn, R.T.; Liu, M.Z.; Jambawalikar, S. Fully Automated Convolutional Neural Network Method for Quantification of Breast MRI Fibroglandular Tissue and Background Parenchymal Enhancement. J. Digit. Imaging 2019, 32, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, X. Breast cancer histopathological image classification using convolutional neural networks with small SE-ResNet module. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Liu, H.; Ni, H.; Wang, X.; Su, M.; Guo, W.; Wang, K.; Jiang, T.; Qian, Y. A Fast and Refined Cancer Regions Segmentation Framework in Whole-slide Breast Pathological Images. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurc, T.; Bakas, S.; Ren, X.; Bagari, A.; Momeni, A.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Kumar, A.; Thibault, M.; Qi, Q.; et al. Segmentation and Classification in Digital Pathology for Glioma Research: Challenges and Deep Learning Approaches. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Mercan, E.; Bartlett, J.; Weave, D.; Elmore, J.G.; Shapiro, L. Y-Net: Joint Segmentation and Classification for Diagnosis of Breast Biopsy Images. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2018; Frangi, A., Schnabel, J., Davatzikos, C., Alberola-López, C., Fichtinger, G., Eds.; Springer: Granada, Spain, 2018; pp. 893–901. [Google Scholar]

- Işın, A.; Direkoğlu, C.; Şah, M. Review of MRI-based Brain Tumor Image Segmentation Using Deep Learning Methods. Proc. Comput. Sci. 2016, 102, 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, S.; Oliveira, A.; Alves, V.; Silva, C.A. On hierarchical brain tumor segmentation in MRI using fully convolutional neural networks: A preliminary study. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 5th Portuguese Meeting on Bioengineering (ENBENG), Coimbra, Portugal, 16–18 February 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.K.H.; Guo, W.; Liu, J.; Dong, F.; Li, Z.; Patterson, T.A.; Hong, H. Machine learning and deep learning for brain tumor MRI image segmentation. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 248, 1974–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, W.; Hussain, J.; Aslam, M.Z.; Jan, S.; Riaz, T.B.; Iqbal, A.; Arif, M.; Khan, I. Enhanced brain tumor segmentation in medical imaging using multi-modal multi-scale contextual aggregation and attention fusion. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collins, F.S.; Green, E.D.; Guttmacher, A.E.; Guyer, M.S. A vision for the future of genomics research. Nature 2003, 422, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.F.; Mardis, E.R. The emerging clinical relevance of genomics in cancer medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talukder, A.; Barham, C.; Li, X.; Hu, H. Interpretation of deep learning in genomics and epigenomics. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa177. [Google Scholar]

- Montesinos-López, O.A.; Montesinos-López, A.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Barrón-López, J.A.; Martini, J.W.R.; Fajardo-Flores, S.B.; Gaytan-Lugo, L.S.; Santana-Mancilla, P.C.; Crossa, J. A review of deep learning applications for genomic selection. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyers, C. Targeted cancer therapy. Nature 2004, 432, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidini, M.; Petrelli, F.; Ghidini, A.; Tomasello, G.; Hahne, J.C.; Passalacqua, R.; Barni, S. Clinical development of mTor inhibitors for renal cancer. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2017, 26, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, G.A.R.; Paiva, R.M.A. Gene therapy: Advances, challenges and perspectives. Einstein 2017, 15, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzdin, A.; Sorokin, M.; Garazha, A.; Sekacheva, M.; Kim, E.; Zhukov, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Kar, S.; Hartmann, C.; et al. Molecular pathway activation—New type of biomarkers for tumor morphology and personalized selection of target drugs. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 53, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridelli, C.; De Marinis, F.; Di Maio, M.; Cortinovis, D.; Cappuzzo, F.; Mok, T. Gefitinib as first-line treatment for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with activating epidermal growth factor receptor mutation: Review of the evidence. Lung Cancer 2011, 71, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, P.; Sirota, M.; Butte, A.J. Ten years of pathway analysis: Current approaches and outstanding challenges. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, e1002375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mziou-Sallami, M.; Roger, P.; Gloaguen, A.; Dandine-Roulland, C.; Ngaho, T.J.; Brohard, S.; Muret, K.; Sandron, F.; Bonnet, E.; Deleuze, J.-F.; et al. GNNenrich: A novel method for pathway enrichment analysis based on graph neural network. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, btaf478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotovskaia, M.A.; Sorokin, M.I.; Emelianova, A.A.; Borisov, N.M.; Kuzmin, D.V.; Borger, P.; Garazha, A.V.; Buzdin, A.A. Pathway Based Analysis of Mutation Data Is Efficient for Scoring Target Cancer Drugs. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Kui, L.; Tang, M.; Li, D.; Wei, K.; Chen, W.; Miao, J.; Dong, Y. High-Throughput Transcriptome Profiling in Drug and Biomarker Discovery. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivachenko, A.Y.; Yuryev, A. Pathway analysis software as a tool for drug target selection, prioritization and validation of drug mechanism. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2007, 11, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choonoo, G.; Blucher, A.S.; Higgins, S.; Boardman, M.; Jeng, S.; Zheng, C.; Jacobs, J.; Anderson, A.; Chamberlin, S.; Evans, N.; et al. Illuminating biological pathways for drug targeting in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpathy, A. The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks. 2015. Available online: http://karpathy.github.io/2015/05/21/rnn-effectiveness/ (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Moghar, A.; Hamiche, M. Stock Market Prediction Using LSTM Recurrent Neural Network. Proc. Comput. Sci. 2020, 170, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shertinsky, A. Fundamentals of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Xie, L.; Han, J.; Guo, X. The Application of Deep Learning in Cancer Prognosis Prediction. Cancers 2020, 12, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, E.; Poli, M.; Faizi, M.; Thomas, A.W.; Sykes, C.B.; Wornow, M.; Patel, A.; Rabideau, C.; Massaroli, S.; Bengio, Y.; et al. HyenaDNA: Long-Range Genomic Sequence Modeling at Single Nucleotide Resolution. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023), New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–19 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, E.; Poli, M.; Durrant, M.G.; Kang, B.; Katrekar, D.; Li, D.B.; Bartie, L.J.; Thomas, A.W.; King, S.H.; Brixi, G.; et al. Sequence modeling and design from molecular to genome scale with Evo. Science 2024, 386, eado9336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, A.; Gunsalus, L.; Nair, S.; Biancalani, T.; Eraslan, G. gReLU: A comprehensive framework for DNA sequence modeling and design. Nat. Methods 2025, 22, 2253–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Zhang, R.; Xie, Y.; Li, C.; Qin, W. Multimodal deep learning for cancer prognosis prediction with clinical information prompts integration. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afreen, S.; Bhurjee, A.K.; Aziz, R.M. Cancer classification using RNA sequencing gene expression data based on Game Shapley local search embedded binary social ski-driver optimization algorithms. Microchem. J. 2024, 205, 111280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, R.; Guo, Y.; Shang, X. GLIMS: A two-stage gradual-learning method for cancer genes prediction using multi-omics data and co-splicing network. iScience 2024, 27, 109387. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, R.; Vafaee, F. Multi-omics prognostic marker discovery and survival modelling: A case study on multi-cancer survival analysis of women’s specific tumours. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auslander, N.; Wolf, Y.I.; Koonin, E.V. In silico learning of tumor evolution through mutational time series. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 9501–9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmahy, A.; Aly, S.; Elkhwsky, F. Cancer Stage Prediction From Gene Expression Data Using Weighted Graph Convolution Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Innovative and Creative Information Technology (ICITech), Salatiga, Indonesia, 23–25 September 2021; pp. 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- Gkotzamanidou, M.; Papavasileiou, K.; Papavasileiou, V.; Merkouris, C.; Karras, A. 1191P Efficient lung cancer stage prediction and outcome informatics with Bayesian deep learning and MCMC method. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanzholova, A.; Coskun, A. Enhancing cancer stage prediction through hybrid deep neural networks: A comparative study. Front. Big Data 2024, 7, 1359703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Cao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, Z.; Xu, Y. Co-expression based cancer staging and application. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. The Cancer Genome Atlas Program: Genomic Data Commons Data Portal. Available online: https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/ (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Cerami, E.; Gao, J.; Dogrusoz, U.; Gross, B.E.; Sumer, S.O.; Aksoy, B.A.; Jacobsen, A.; Byrne, C.J.; Heuer, M.L.; Larsson, E.; et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Aksoy, B.A.; Dogrusoz, U.; Dresdner, G.; Gross, B.; Sumer, S.O.; Sun, Y.; Jacobsen, A.; Sinha, R.; Larsson, E.; et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, pl1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBerardinis, R.J.; Chandel, N.S. Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1600200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.Y.G.L.; van Oortmarssen, G.J.; de Koning, H.J.; Boer, R.; Habbema, J.D.F. The MISCAN-Fadia continuous tumor growth model for breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2006, 36, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, H.; Choi, H. Investigating the Clinico-Molecular and Immunological Evolution of Lung Adenocarcinoma Using Pseudotime Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 828505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazyari, M.J.; Saadat, Z.; Firouzjaei, A.A.; Aghaee-Bakhtiari, S.H. Deciphering colorectal cancer progression features and prognostic signature by single-cell RNA sequencing pseudotime trajectory analysis. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2023, 35, 101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Yang, K.; Yang, G.; Chen, D.; Tang, H.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, C. Aberrant expression of clock gene period and its correlations with the growth, proliferation and metastasis of buccal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55894. [Google Scholar]

- Abou Youssif, T.; Tanguay, S. Natural history and management of small renal masses. Curr. Oncol. 2009, 16, S2–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wishart, D.S.; Feunang, Y.D.; Guo, A.C.; Lo, E.J.; Marcu, A.; Grant, J.R.; Sajed, T.; Johnson, D.; Li, C.; Sayeeda, Z.; et al. DrugBank 5.0: A major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D1074–D1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, V.; Knox, C.; Djoumbou, Y.; Jewison, T.; Guo, A.C.; Liu, Y.; Maciejewski, A.; Arndt, D.; Wilson, M.; Neveu, V.; et al. DrugBank 4.0: Shedding new light on drug metabolism. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D1091–D1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, C.; Law, V.; Jewison, T.; Liu, P.; Ly, S.; Frolkis, A.; Pon, A.; Banco, K.; Mak, C.; Neveu, V.; et al. DrugBank 3.0: A comprehensive resource for ‘omics’ research on drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D1035–D1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Knox, C.; Guo, A.C.; Cheng, D.; Shrivastava, S.; Tzur, D.; Gautam, B.; Hassanali, M. DrugBank: A knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions and drug targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, D901–D906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wishart, D.S.; Knox, C.; Guo, A.C.; Shrivastava, S.; Hassanali, M.; Stothard, P.; Chang, Z.; Woolsey, J. DrugBank: A comprehensive resource for in silico drug discovery and exploration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, D668–D672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, S.D.; Armstrong, J.F.; Faccenda, E.; Southan, C.; Alexander, S.P.H.; Davenport, A.P.; Pawson, A.J.; Spedding, M.; Davies, J.A.; NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2022: Curating pharmacology for COVID-19, malaria and antibacterials. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D1282–D1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, M.R.; Campbell, P.J.; Futreal, P.A. The cancer genome. Nature 2009, 458, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, B.K.; Deng, C.X. Characterization of potential driver mutations involved in human breast cancer by computational approaches. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 50252–50272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Bridle, J.S. Training Stochastic Model Recognition Algorithms as Networks can Lead to Maximum Mutual Information Estimation of Parameters. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2 (NIPS 1989), Denver, CO, USA, 27–30 November 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Survey on categorical data for neural networks. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Paliwal, K.K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1997, 45, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R.; Nishio, M.; Do, R.K.G.; Togashi, K. Convolutional neural networks: An overview and application in radiology. Insights Imaging 2018, 9, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajian-Tilaki, K. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis for Medical Diagnostic Test Evaluation. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 4, 627–635. [Google Scholar]

- Corbacioglu, S.K.; Aksel, G. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic accuracy studies: A guide to interpreting the area under the curve value. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 23, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, M.H.; Tokheim, C.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Sengupta, S.; Bertrand, D.; Weerasinghe, A.; Colaprico, A.; Wendi, M.C.; Kim, J.; Reardon, B.; et al. Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell 2018, 173, 371–385.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranzo, J.; Martincorena, I.; Koonin, E.V. Cancer-mutation network and the number and specificity of driver mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E6010–E6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-García, G.; Jerez, J.M.; Franco, L.; Veredas, F.J. Transfer learning with convolutional neural networks for cancer survival prediction using gene-expression data. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, C.; Park, S.; Ko, S.; Ahn, J. Increasing prediction accuracy of pathogenic staging by sample augmentation with a GAN. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, K.; Fenton, J.J.; Duberstein, P.R.; Epstein, R.M.; Xing, G.; Tancredi, D.J.; Hoerger, M.; Gramling, R.; Kravitz, R.L. Prognostic accuracy of patients, caregivers, and oncologists in advanced cancer. Cancer 2019, 125, 2684–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkovova, K.; Bilanicova, D.; Bartonova, A.; Letašiová, S.; Dusinska, M. Associations between environmental factors and incidence of cutaneous melanoma. Environ. Health 2012, 11, S12. [Google Scholar]

- Parkin, D.M.; Boyd, L.; Walker, L.C. 16. The fraction of cancer attributable to lifestyle and environmental factors in the UK in 2010. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 105, S77–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, D.E.; Chan, T.; Waldron, L.; Speers, C.; Feng, F.Y.; Ogunwobi, O.O.; Osborne, J.R. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Genomic Sequencing. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1070–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pharoah, P.D.; Guilford, P.; Caldas, C.; The International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium. Incidence of gastric cancer and breast cancer in CDH1 (E-cadherin) mutation carriers from hereditary diffuse gastric cancer families. Gastroenterology 2001, 121, 1348–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Veronesi, P.; Sacchini, V.; Galimberti, V. Prognosis and outcome in CDH1-mutant lobular breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2018, 27, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Intra, M.; Trentin, C.; Veronesi, P.; Galimberti, V. CDH1 germline mutations and hereditary lobular breast cancer. Fam. Cancer 2016, 15, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.S.; Bindra, R.S.; Mo, A.; Hayman, T.; Husain, Z.; Contessa, J.N.; Gaffney, S.G.; Townsend, J.P.; Yu, J.B. CDKN2A Copy Number Loss Is an Independent Prognostic Factor in HPV-Negative Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Gadhikar, M.A.; Zhang, J.; Shen, L.; Rao, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, M.; Kalu, N.N.; Johnson, F.M.; Byers, L.A.; Heymach, J.; et al. CDKN2A/p16 Deletion in Head and Neck Cancer Cells Is Associated with CDK2 Activation, Replication Stress, and Vulnerability to CHK1 Inhibition. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 781–797. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Shen, Z.; Ye, D.; Li, Q.; Deng, H.; Liu, H.; Li, J. The Association and Clinical Significance of CDKN2A Promoter Methylation in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 50, 868–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sáez, O.; Chic, N.; Pascual, T.; Adamo, B.; Vidal, M.; González-Farré, B.; Sanfeliu, E.; Schettini, F.; Conte, B.; Brasó-Maristany, F.; et al. Frequency and spectrum of PIK3CA somatic mutations in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, J.; Song, X.; DuCote, T.J.; Byrd, A.L.; Wang, C.; Brainson, C.F. EZH2 inhibition confers PIK3CA-driven lung tumors enhanced sensitivity to PI3K inhibition. Cancer Lett. 2022, 524, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E.J.; Mollon, L.E.; Dean, J.L.; Warholak, T.L.; Aizer, A.; Platt, E.A.; Tang, D.H.; Davis, L.E. A Systematic Review of the Prevalence and Diagnostic Workup of PIK3CA Mutations in HR+/HER2− Metastatic Breast Cancer. Int. J. Breast Cancer 2020, 2020, 3759179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, K.; Tischkowitz, M. Clinical implications of germline mutations in breast cancer: TP53. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 167, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Pan, C.; Bei, J.-X.; Li, B.; Liang, C.; Xu, Y.; Fu, X. Mutant p53 in Cancer Progression and Targeted Therapies. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 595187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivlin, N.; Brosh, R.; Oren, M.; Rotter, V. Mutations in the p53 Tumor Suppressor Gene: Important Milestones at the Various Steps of Tumorigenesis. Genes Cancer 2011, 2, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, F.; Ciruelos, E.; Rubovszky, G.; Campone, M.; Loibl, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Iwata, H.; Conte, P.; Mayer, I.A.; Kaufman, B.; et al. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-Mutated, Hormone Receptor-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1929–1940. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyling, M.; Santoro, A.; Mollica, L.; Leppä, S.; Follows, G.; Lenz, G.; Kim, W.S.; Nagler, A.; Dimou, M.; Demeter, J.; et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of the PI3K inhibitor copanlisib in patients with relapsed or refractory indolent lymphoma: 2-year follow-up of the CHRONOS-1 study. Am. J. Hematol. 2020, 95, 362–371. [Google Scholar]

- Soria, J.C.; LoRusso, P.; Bahleda, R.; Lager, J.; Liu, L.; Jiang, J.; Martini, J.-F.; Macé, S.; Burris, H. Phase I dose-escalation study of pilaralisib (SAR245408, XL147), a pan-class I PI3K inhibitor, in combination with erlotinib in patients with solid tumors. Oncologist 2015, 20, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, R.N.; Lambracht-Washington, D.; Yu, G.; Xia, W. Genomics of Alzheimer Disease: A Review. JAMA Neurol. 2016, 73, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Cutting, G.R. The genetics and genomics of cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2020, 19, S5–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Accuracy Range | Cancer Types | |

|---|---|---|---|

| This Work | RNN | 36–70% | 11 types |

| López-García et al. [76] | CNN | 68% | Lung |

| López-García et al. [76] | ML | 62–70% | Lung |

| Kwon et al. [77] | GAN + CNN | 41–80% | 12 types |

| Kwon et al. [77] | GAN + RF | 47–74% | 12 types |

| Kwon et al. [77] | GAN + DNN | 42–77% | 12 types |

| Yu et al. [49] | C5.0 | 70–95% | 8 types |

| Elmahy et al. [46] | GCN | 82% | Renal |

| Gkotzamanidou et al. [47] | BNN | 93% | Lung |

| Amanzholova et al. [48] | Ensemble | 89–97% | 3 types |

| Malhotra et al. [78] | Oncologists | 62% | Advanced |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Parthasarathy, R.; Bhowmik, A.K. A Novel Recurrent Neural Network Framework for Prediction and Treatment of Oncogenic Mutation Progression. AI 2026, 7, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai7020054

Parthasarathy R, Bhowmik AK. A Novel Recurrent Neural Network Framework for Prediction and Treatment of Oncogenic Mutation Progression. AI. 2026; 7(2):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai7020054

Chicago/Turabian StyleParthasarathy, Rishab, and Achintya K. Bhowmik. 2026. "A Novel Recurrent Neural Network Framework for Prediction and Treatment of Oncogenic Mutation Progression" AI 7, no. 2: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai7020054

APA StyleParthasarathy, R., & Bhowmik, A. K. (2026). A Novel Recurrent Neural Network Framework for Prediction and Treatment of Oncogenic Mutation Progression. AI, 7(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai7020054