The Artificial Intelligence Quotient (AIQ): Measuring Machine Intelligence Based on Multi-Domain Complexity and Similarity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Existing Benchmarks

1.2. Existing Frameworks

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definition of a Test

2.2. Dimensions of Intelligence

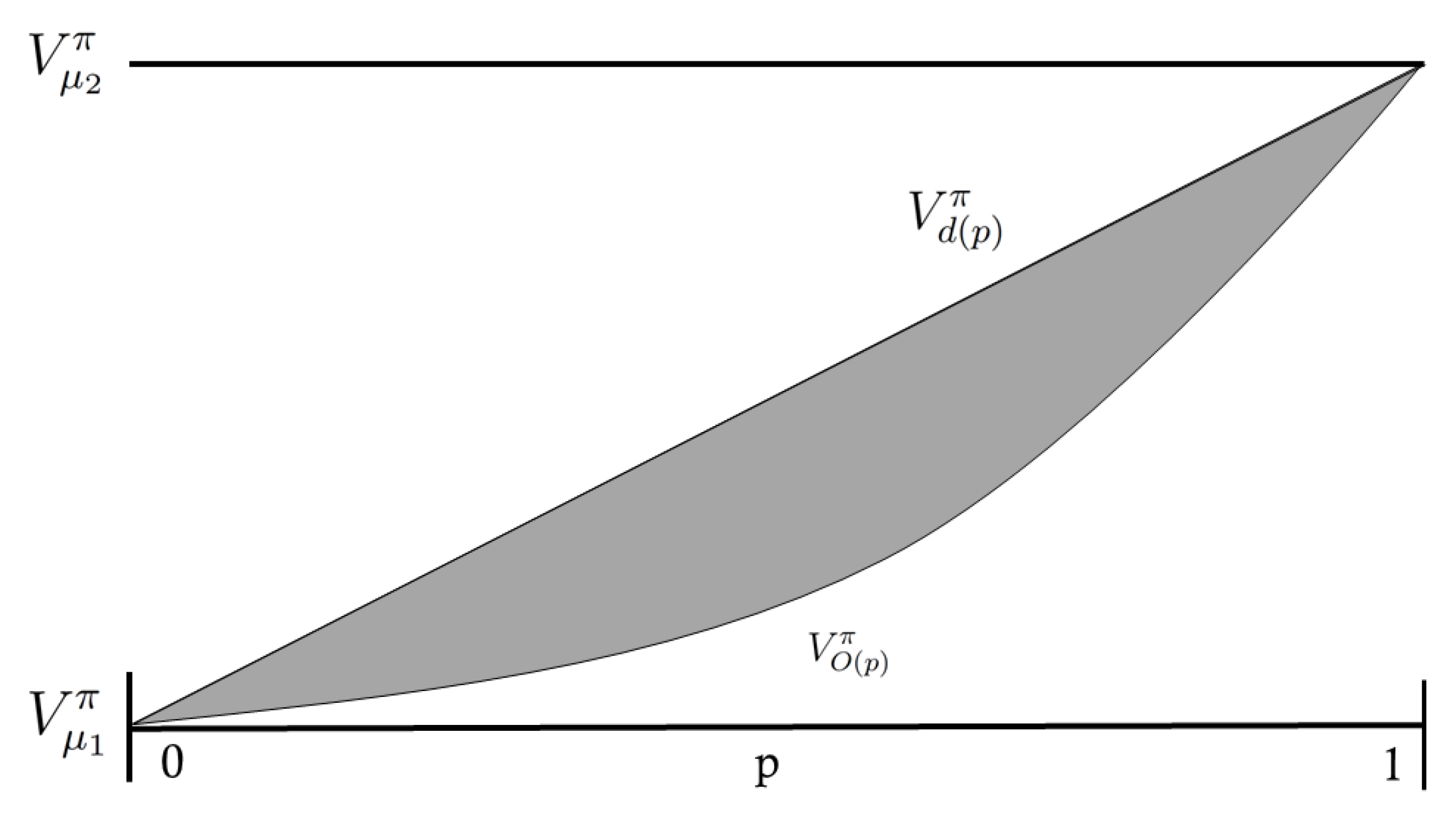

2.3. Agent Capacitance

2.4. Complexity

2.4.1. Definition

2.4.2. Ideal Measure

2.4.3. Practical Measures

2.5. Dissimilarity

2.5.1. Definition

2.5.2. Ideal Measure

2.5.3. Practical Measure

2.6. Artificial Intelligence Quotient (AIQ)

2.6.1. Intelligence Space

2.6.2. Equation Form

2.6.3. AIQ as a Benchmark

3. Results

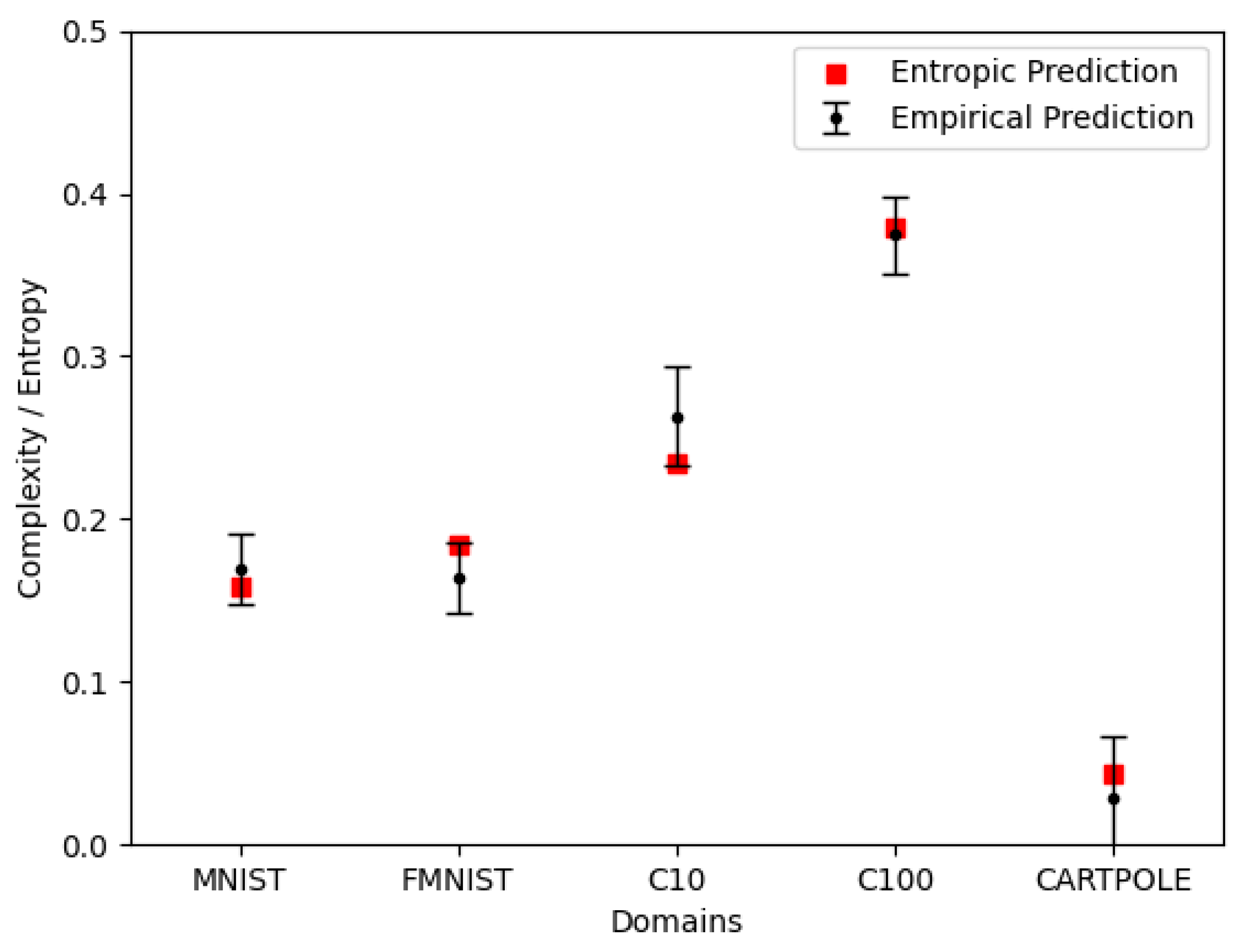

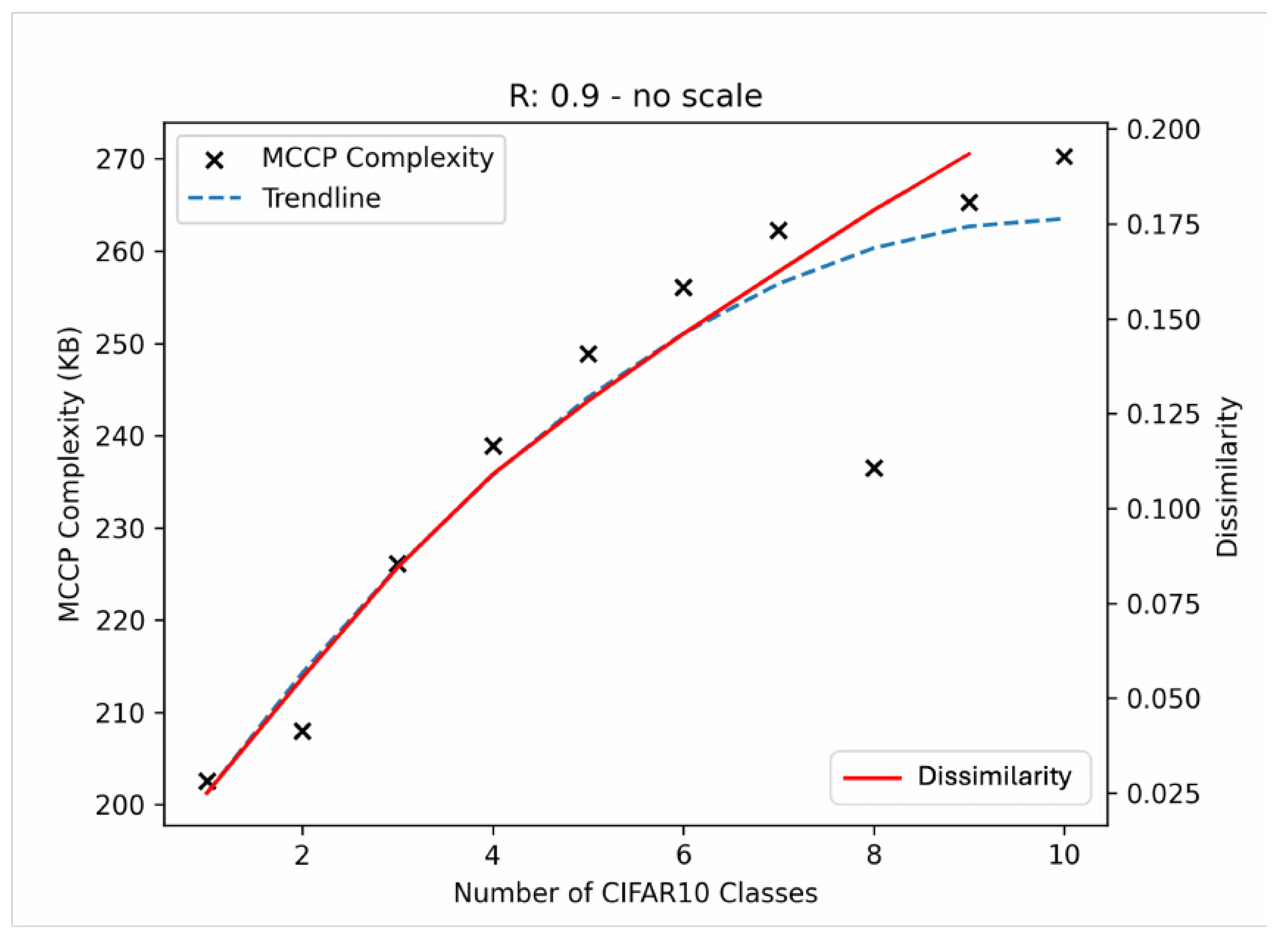

3.1. Complexity Results

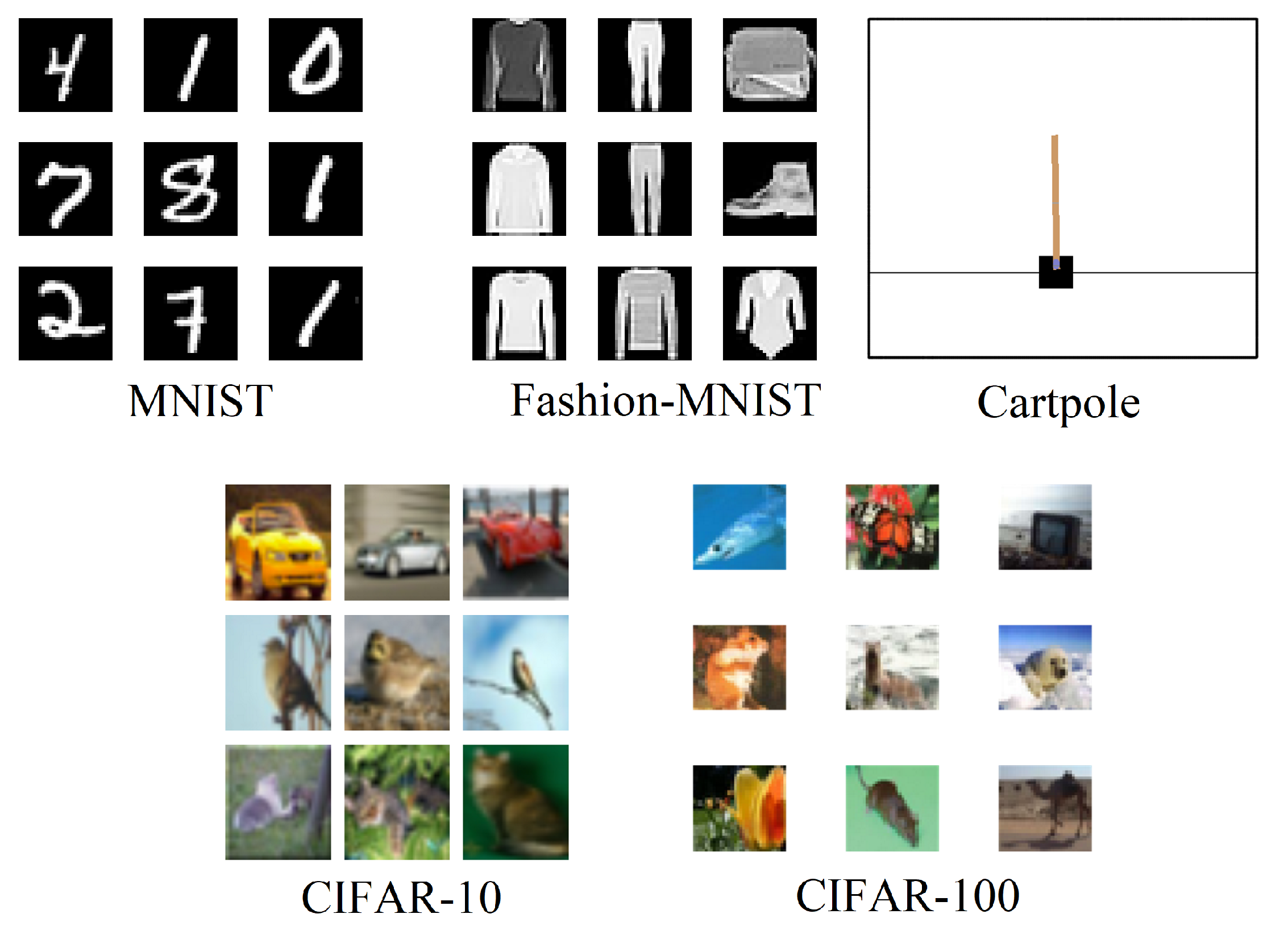

3.1.1. Domains

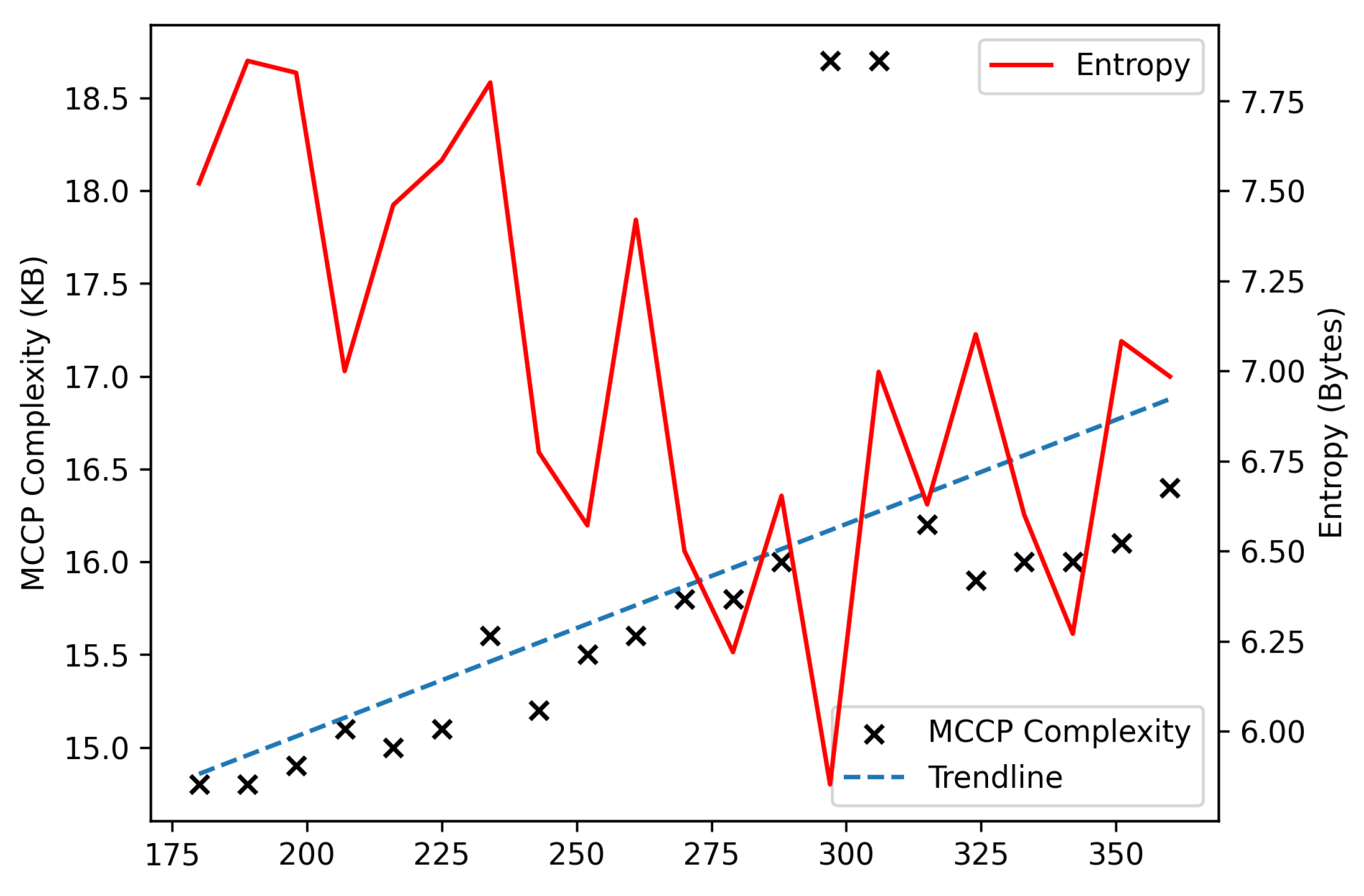

3.1.2. Entropic Verification

3.1.3. Known Difficulty Verification

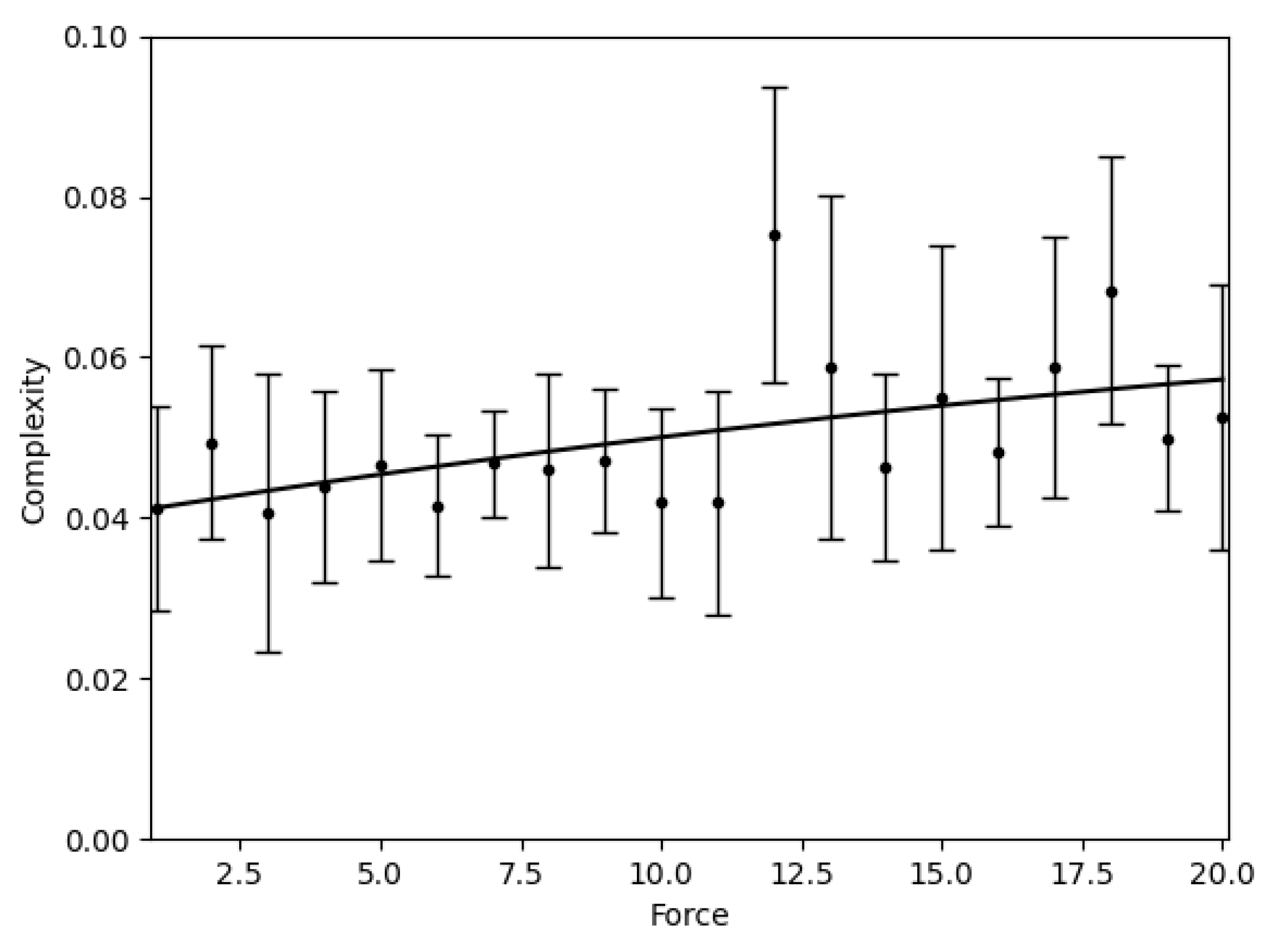

3.1.4. Parameter Analysis

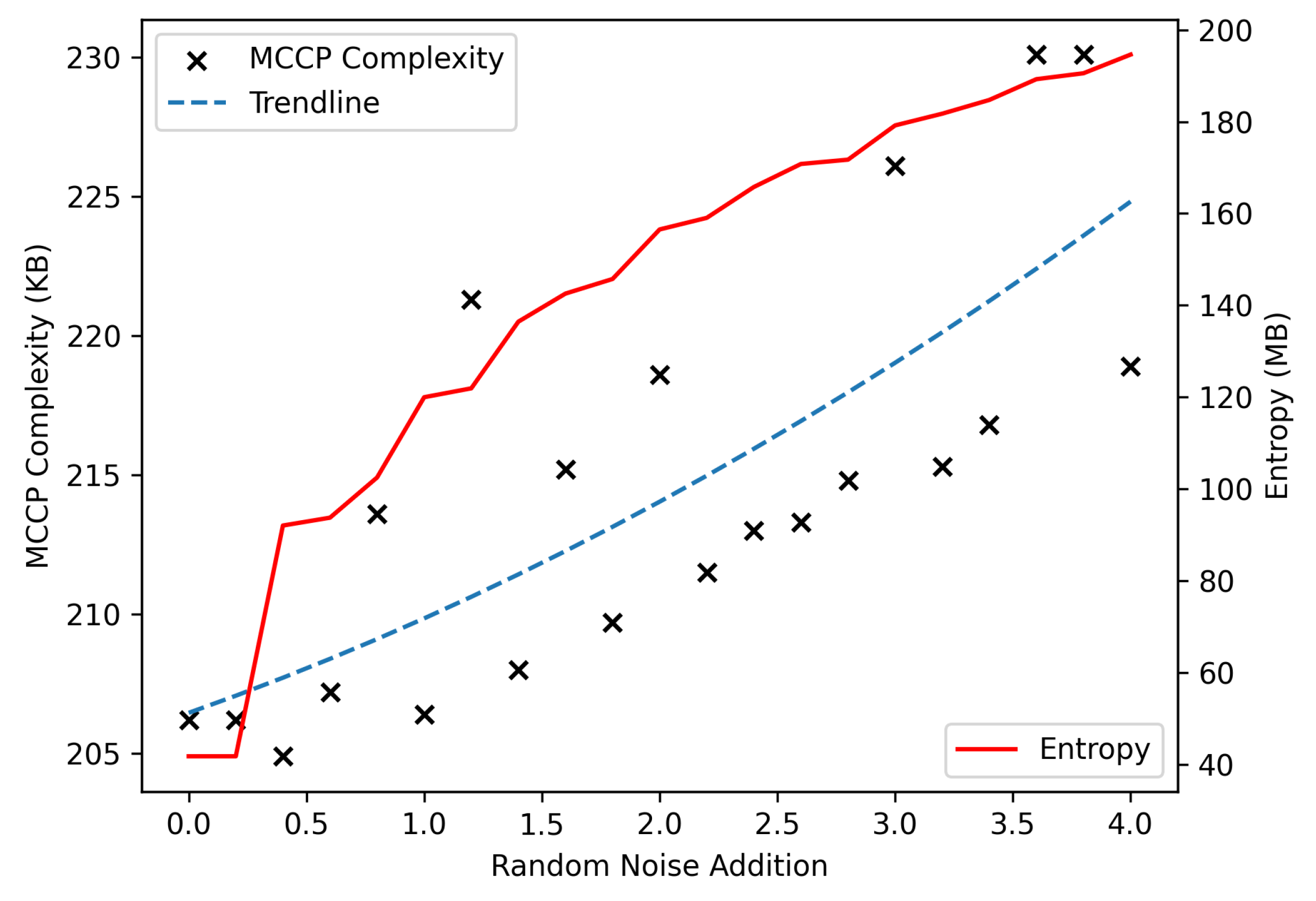

3.1.5. MNIST Noise

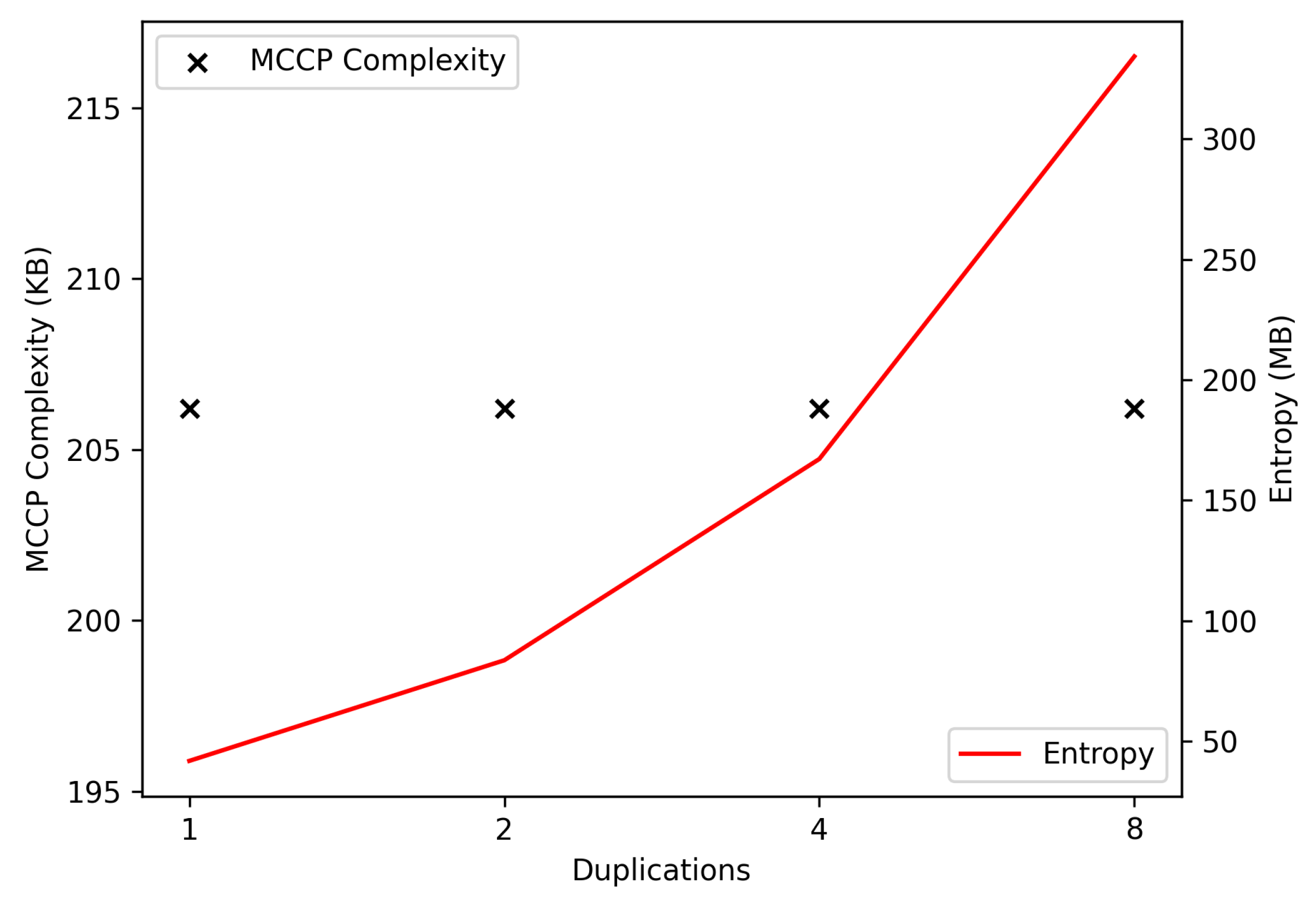

3.1.6. MNIST Duplication

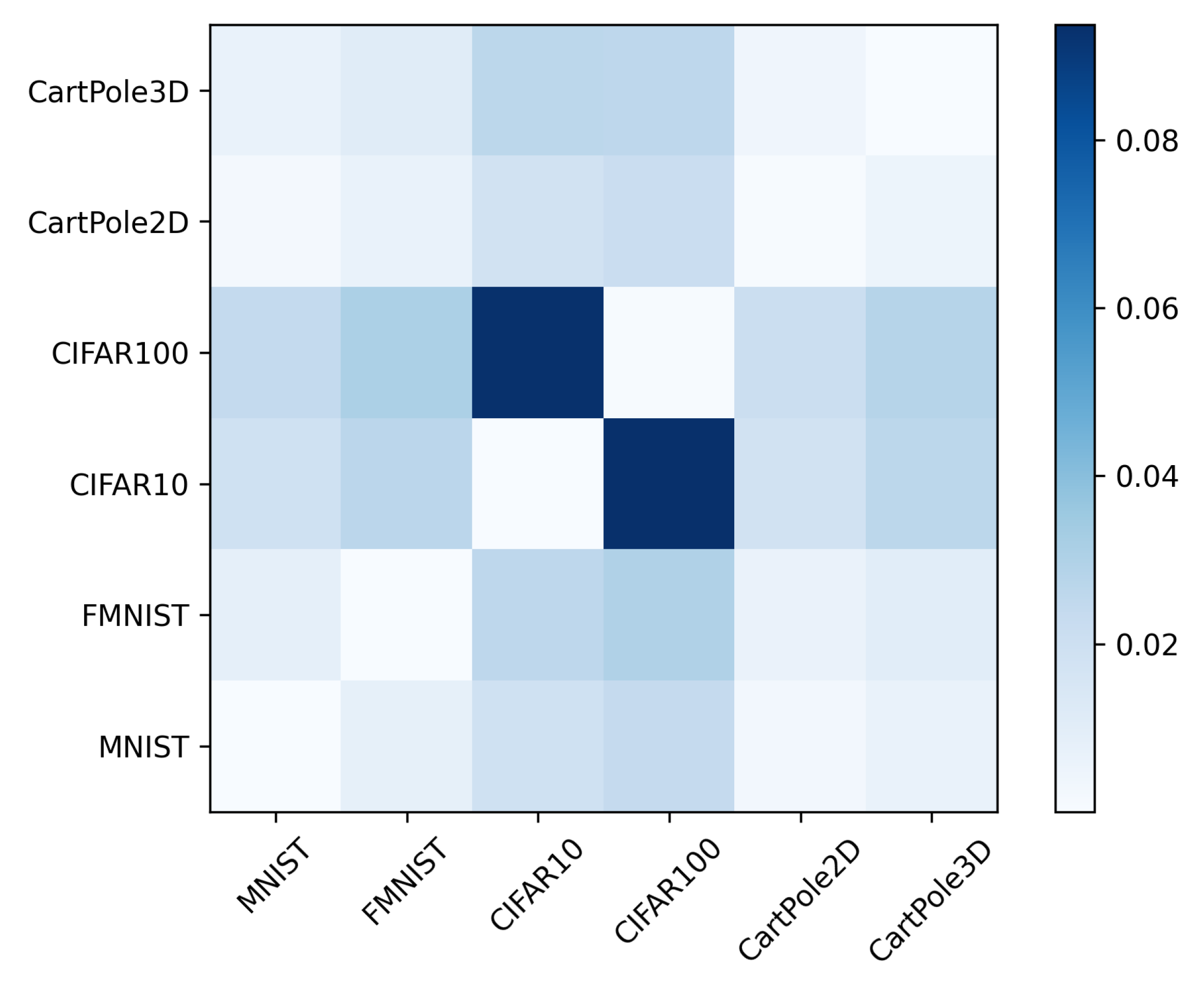

3.2. Dissimilarity Results

3.2.1. Zero Distance

3.2.2. Different, but Similar Domains

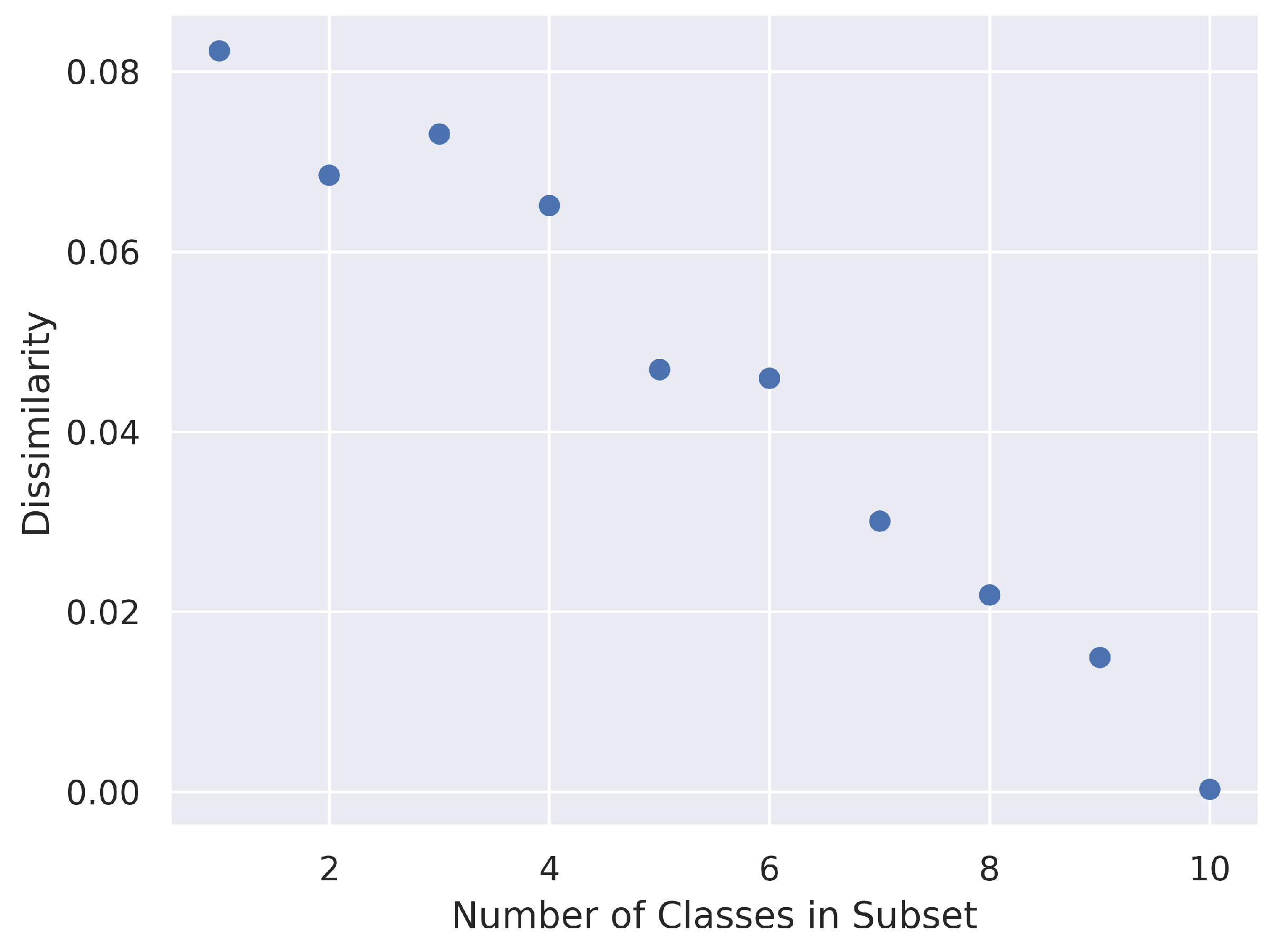

3.2.3. Subset Distance

3.2.4. Known Parametric Shift

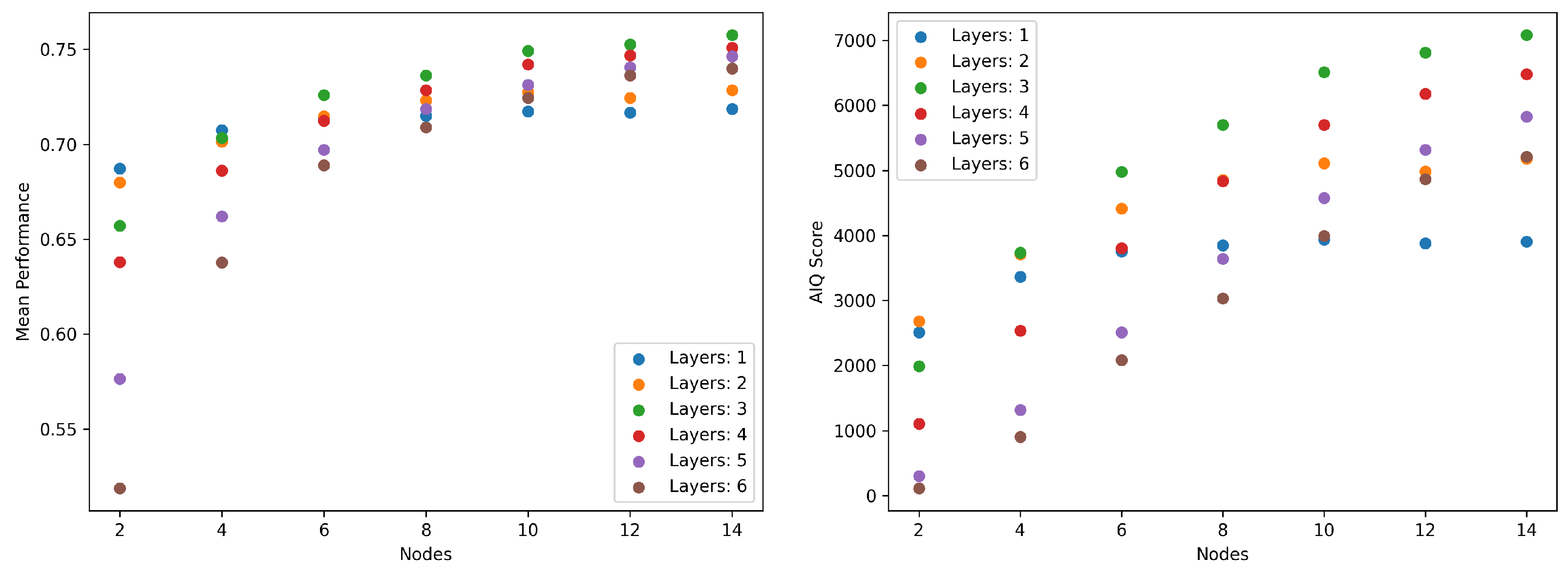

3.3. AIQ Results

3.3.1. Complexity vs. Dissimilarity

3.3.2. AIQ Benchmark Complexity

3.3.3. AIQ Benchmark Dissimilarity

3.3.4. AIQ Benchmark Complexity vs. Dissimilarity

3.3.5. AIQ Benchmark Intelligence

3.3.6. AIQ Handicapping

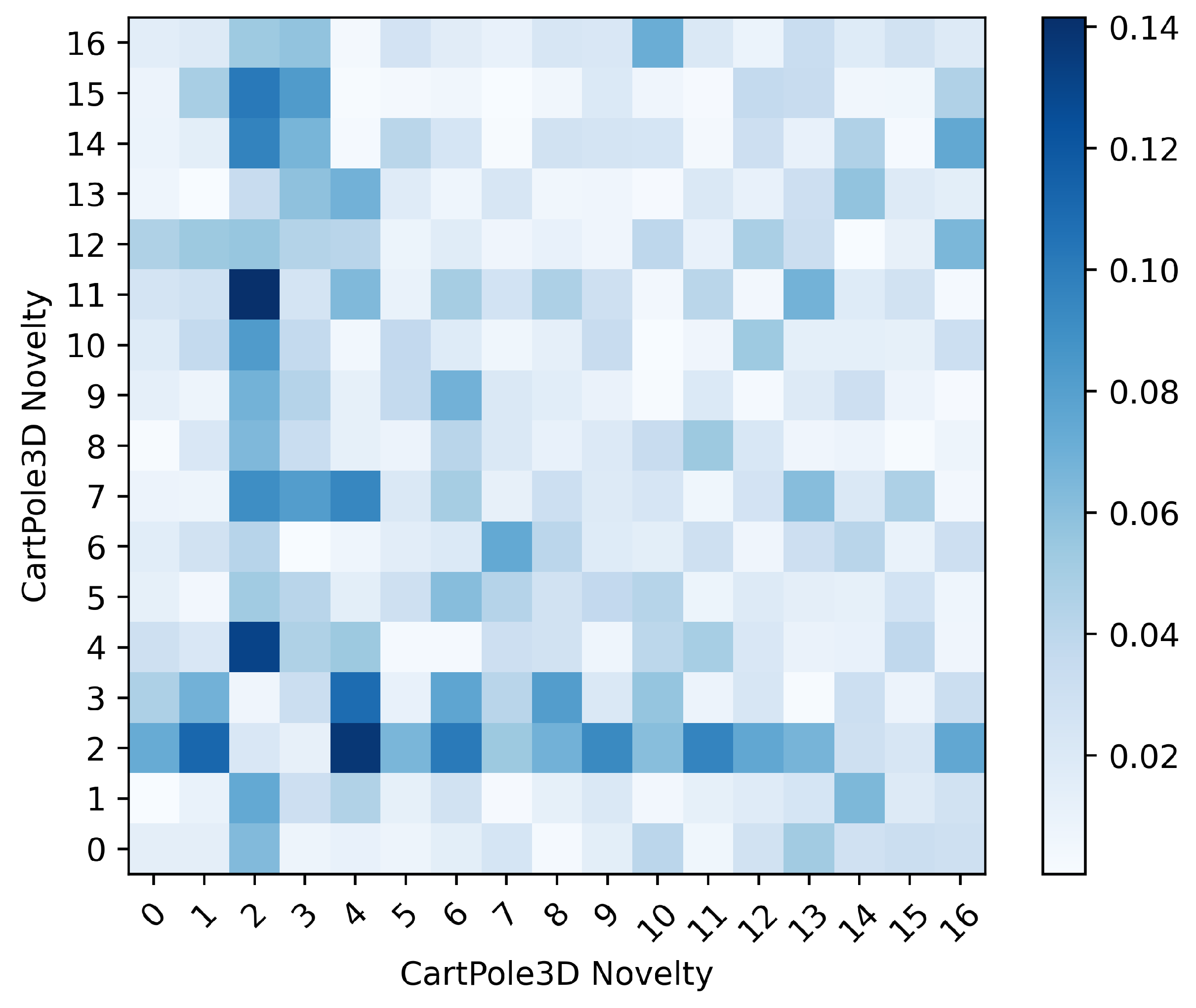

3.4. Application to Open-World Novelty

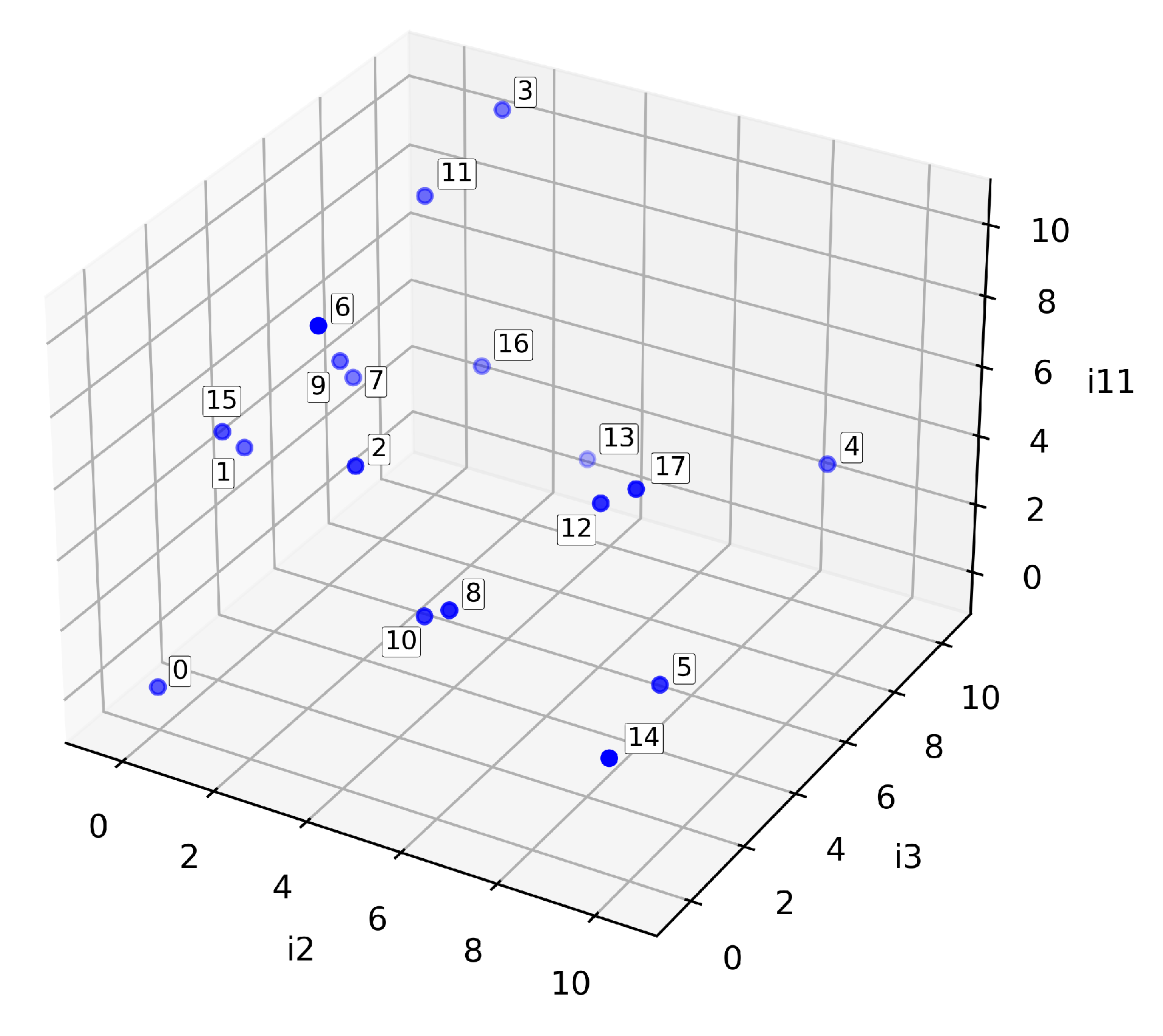

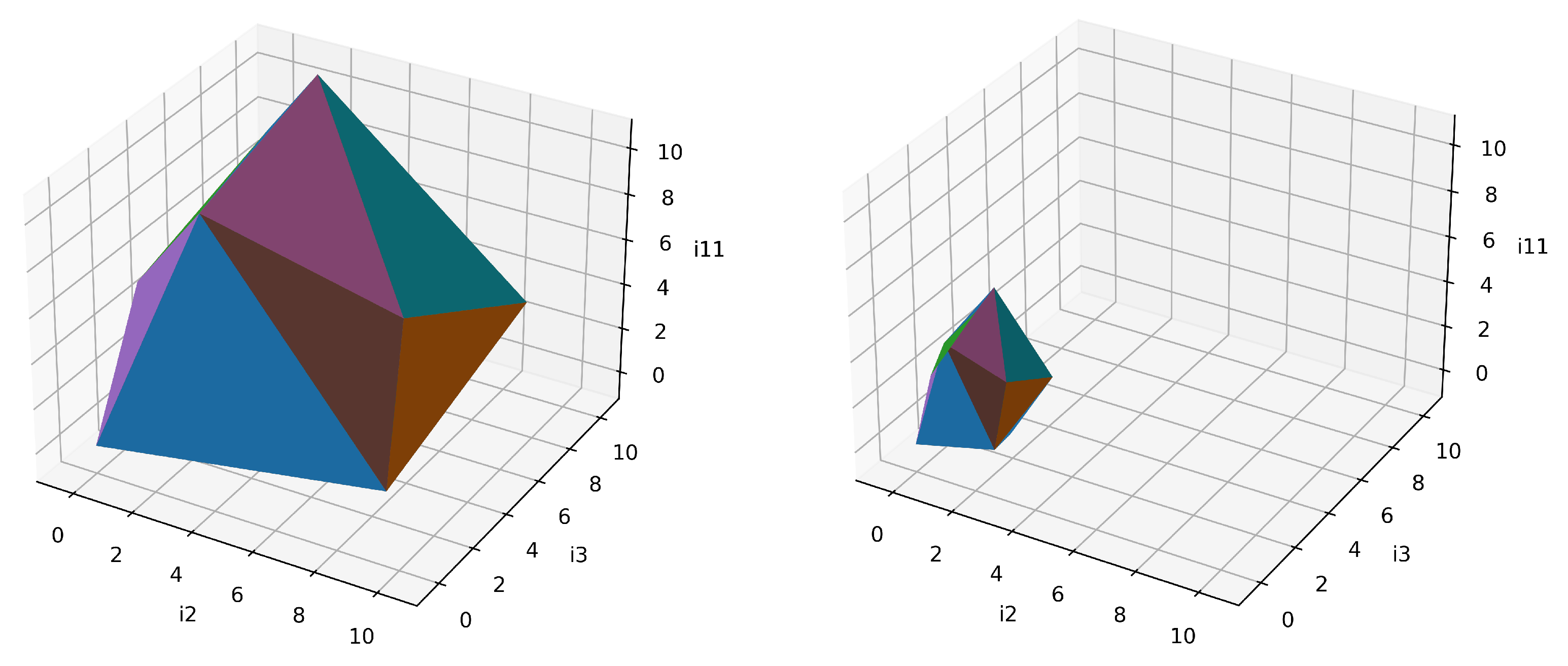

3.4.1. CartPole3D Domain

3.4.2. SAIL-ON Metrics

3.4.3. CartPole3D AI Systems

3.4.4. AIQ Results on CartPole3D

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGI | Artificial General Intelligence |

| AIQ | Artificial Intelligence Quotient |

| ALE | Arcade Learning Environment |

| ANU | Australian National University |

| APTI | Asymptotic Performance Task Improvement |

| ARC | Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus |

| ARO | Army Research Office |

| AuC | Area under Curve |

| CIFAR | Canadian Institute For Advanced Research |

| DARPA | Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency |

| DoD | Department of Defense |

| DQN | Deep Q-learning Network |

| FMNIST | Fashion MNIST |

| GLUE | General Language Understanding Evaluation |

| GRE | Graduate Records Exam |

| GVGAI | General Video Game AI |

| HELM | Holistic Evaluation of Language Models |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| MCCP | Monte Carlo Cross Performance |

| MDL | Minimum Description Length |

| MNIST | Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| PARC | Palo Alto Research Center |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| SAIL-ON | Science of AI and Learning for Open-world Novelty |

| SAT | Scholastic Aptitude Test |

| SOTA | State of the Art |

| UCCS | University of Colorado at Colorado Springs |

| UMass | University of Massachusetts Amherst |

| WSU | Washington State University |

References

- Turing, A.M. Computing machinery and intelligence. In Parsing the Turing Test: Philosophical and Methodological Issues in the Quest for the Thinking Computer; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2009; pp. 23–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, G.; Liu, B. Breaking the closed world assumption in text classification. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; Association for Computational Linguistics: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 506–514. [Google Scholar]

- Berner, C.; Brockman, G.; Chan, B.; Cheung, V.; Debiak, P.; Dennison, C.; Farhi, D.; Fischer, Q.; Hashme, S.; Hesse, C.; et al. Dota 2 with Large Scale Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.06680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rony, J.; Hafemann, L.; Oliveira, L.; Ayed, I.B.; Sabourin, R.; Granger, E. Decoupling Direction and Norm for Efficient Gradient-Based L2 Adversarial Attacks and Defenses. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, M. Identifying AI Hazards and Responsibility Gaps. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 54338–54349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Singh, A.; Michael, J.; Hill, F.; Levy, O.; Bowman, S.R. GLUE: A Multi-Task Benchmark and Analysis Platform for Natural Language Understanding. In EMNLP 2018-2018 EMNLP Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP, Proceedings of the 1st Workshop; Association for Computational Linguistics: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Pruksachatkun, Y.; Nangia, N.; Singh, A.; Michael, J.; Hill, F.; Levy, O.; Bowman, S.R. SuperGLUE: A Stickier Benchmark for General-Purpose Language Understanding Systems. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 3266–3280. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3454287.3454581 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Wang, B.; Xu, C.; Wang, S.; Gan, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, J.; Awadallah, A.H.; Li, B. Adversarial glue: A multi-task benchmark for robustness evaluation of language models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.02840. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson, T.; Geva, M.; Gupta, A.; Gardner, M.; Goldberg, Y.; Deutch, D.; Berant, J. Break it down: A question understanding benchmark. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2020, 8, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Pinto, V.; Zhang, P.; Gamage, C.; Nikonova, E.; Renz, J. Science Birds Novelty: An Open-world Learning Test-bed for Physics Domains. In Proceedings of the AAAI Spring Symposium on Designing AI for Open-World Novelty, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 21–23 March 2022; Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Goss, S.; Steininger, R.; Narayanan, D.; Olivença, D.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, P.; Amato, J.; Voit, E.; Voit, W.; Kildebeck, E. Polycraft World AI Lab (PAL): An Extensible Platform for Evaluating Artificial Intelligence Agents. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.11891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kejriwal, M.; Thomas, S. A multi-agent simulator for generating novelty in monopoly. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2021, 112, 102364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balloch, J.; Lin, Z.; Hussain, M.; Srinivas, A.; Wright, R.; Peng, X.; Kim, J.; Riedl, M. Novgrid: A flexible grid world for evaluating agent response to novelty. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.12117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boult, T.; Windesheim, N.; Zhou, S.; Pereyda, C.; Holder, L. Weibull-Open-World (WOW) Multi-Type Novelty Detection in CartPole3D. Algorithms 2022, 15, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliani, A.; Khalifa, A.; Berges, V.P.; Harper, J.; Teng, E.; Henry, H.; Crespi, A.; Togelius, J.; Lange, D. Obstacle Tower: A Generalization Challenge in Vision, Control, and Planning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.01378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngblood, M.; Nolen, B.; Ross, M.; Holder, L. Building Test Beds for AI with the Q3 Mode Base; Technical report; University of Texas at Arlington: Arlington, TX, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cobbe, K.; Hesse, C.; Hilton, J.; Schulman, J. Leveraging Procedural Generation to Benchmark Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual Event, 13–18 July 2020; Daume, H., Singh, A., Eds.; PMLR: Mc Kees Rocks, PA, USA, 2020; Volume 119, pp. 2048–2056. [Google Scholar]

- Torrado, R.R.; Bontrager, P.; Togelius, J.; Liu, J.; Perez-Liebana, D. Deep Reinforcement Learning for General Video Game AI. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence and Games (CIG 2018), Maastricht, The Netherlands, 14–17 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bellemare, M.; Naddaf, Y.; Veness, J.; Bowling, M. The Arcade Learning Environment: An Evaluation Platform for General Agents. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2013, 47, 253–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Rastogi, A.; Rao, A.; Shoeb, A.A.M.; Abid, A.; Fisch, A.; Brown, A.R.; Santoro, A.; Gupta, A.; Garriga-Alonso, A.; et al. Beyond the Imitation Game: Quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 104, 00012. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, P.; Bommasani, R.; Lee, T.; Tsipras, D.; Soylu, D.; Yasunaga, M.; Zhang, Y.; Narayanan, D.; Wu, Y.; Kumar, A.; et al. Holistic Evaluation of Language Models. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, W.; Cui, R.; Guo, Y.; Liang, Y.; Lu, S.; Wang, Y.; Saied, A.; Chen, W.; Duan, N. AGIEval: A Human-Centric Benchmark for Evaluating Foundation Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.06364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. On the Measure of Intelligence. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.01547. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, J. The Raven’s Progressive Matrices: Change and Stability over Culture and Time. Cogn. Psychol. 2000, 41, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, I.D.; Bender, E.M.; Paullada, A.; Denton, E.; Hanna, A. AI and the Everything in the Whole Wide World Benchmark. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.15366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Orallo, J. Beyond the turing test. J. Logic, Lang. Inf. 2000, 9, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, S.; Hutter, M. Universal intelligence: A definition of machine intelligence. Minds Mach. 2007, 17, 391–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, S.; Veness, J. An approximation of the universal intelligence measure. In Algorithmic Probability and Friends. Bayesian Prediction and Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 236–249. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Orallo, J.; Dowe, D. Measuring universal intelligence: Towards an anytime intelligence test. Artif. Intell. 2010, 174, 1508–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Orallo, J. Evaluation in artificial intelligence: From task-oriented to ability-oriented measurement. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2017, 48, 397–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Orallo, J. A (hopefully) Unbiased Universal Environment Class for Measuring Intelligence of Biological and Artificial Systems. In Proceedings of the Artificial General Intelligence-Proceedings of the Third Conference on Artificial General Intelligence, AGI 2010, Lugano, Switzerland, 5–8 March 2010; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 80–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insa-Cabrera, J.; Dowe, D.; Hernández-Orallo, J. Evaluating a reinforcement learning algorithm with a general intelligence test. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 7023, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J. The Three-Stratum Theory of Cognitive Abilities; The Guilford Press: Fredericksburg, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, J.; McGrew, K. The Cattell-Horn-Carroll theory of cognitive abilities. Contemp. Intellect. Assess. Theor. Tests Issues 2018, 733, 163. [Google Scholar]

- Pereyda, C.; Holder, L. Toward a General-Purpose Artificial Intelligence Test by Combining Diverse Tests. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence (ICAI), Stockholm, Sweden, 13–19 July 2018; pp. 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, C.; Dowe, D. Minimum message length and Kolmogorov complexity. Comput. J. 1999, 42, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A. Three approaches to the quantitative definition of information. Probl. Inf. Transm. 1965, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiger, L. A tight upper bound on Kolmogorov complexity and uniformly optimal prediction. Theory Comput. Syst. 1998, 31, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Orallo, J. The Measure of All Minds: Evaluating Natural and Artificial Intelligence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, L. Universal sequential search problems. Probl. Peredachi Informatsii 1973, 9, 115–116. [Google Scholar]

- Halmos, P. A Hilbert Space Problem Book; Graduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, A. Generalia de Genesi Figurarum Planarum et Inde Pendentibus Earum Affectionibus; Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Digitized): Munich, Germany, 1769. [Google Scholar]

- Allgower, E.; Schmidt, P. Computing volumes of polyhedra. Math. Comput. 1986, 46, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L. The MNIST database of handwritten digit images for machine learning research. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2012, 29, 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Rasul, K.; Vollgraf, R. Fashion-mniST: A novel image dataset for benchmarking machine learning algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.07747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A. Learning Multiple Layers of Features from Tiny Images; Technical Report; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barto, A.; Sutton, R.; Anderson, C. Neuronlike Adaptive Elements That Can Solve Difficult Learning Control Problems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1983, SMC-13, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.; Zolna, K.; Parisotto, E.; Colmenarejo, S.G.; Novikov, A.; Barth-Maron, G.; Gimenez, M.; Sulsky, Y.; Kay, J.; Springenberg, J.T.; et al. A Generalist Agent. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.06175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veness, J.; Ng, K.S.; Hutter, M.; Uther, W.; Silver, D. A Monte-Carlo AIXI Approximation. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2011, 40, 95–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockman, G.; Cheung, V.; Pettersson, L.; Schneider, J.; Schulman, J.; Tang, J.; Zaremba, W. OpenAI Gym. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.01540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galatolo, S.; Hoyrup, M.; Rojas, C. Effective symbolic dynamics, random points, statistical behavior, complexity and entropy. Inf. Comput. 2010, 208, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowicz, P.; Pereyda, C.; Clary, K.; Stern, R.; Boult, T.; Jensen, D.; Holder, L. Novelty in 2D CartPole Domain. In A Unifying Framework for Formal Theories of Novelty; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DARPA. Teaching AI Systems to Adapt to Dynamic Environments. 2019. Available online: https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2019-02-14 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Chadwick, T.; Chao, J.; Izumigawa, C.; Galdorisi, G.; Ortiz-Pena, H.; Loup, E.; Soultanian, N.; Manzanares, M.; Mai, A.; Yen, R.; et al. Characterizing Novelty in the Military Domain. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.12314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, L.B.; Eaves, B.; Shafto, P.; Pereyda, C.; Thomas, B.; Cook, D.J. Detecting and reacting to smart home novelties. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2025, 39, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wydmuch, M.; Kempka, M.; Jaśkowski, W. Vizdoom competitions: Playing doom from pixels. IEEE Trans. Games 2019, 11, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coumans, E.; Bai, Y. Pybullet, a Python Module for Physics Simulation for Games, Robotics and Machine Learning, 2016–2023. Available online: https://pybullet.org (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Xue, C.; Nikonova, E.; Zhang, P.; Renz, J. Rapid Open-World Adaptation by Adaptation Principles Learning. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, W.; Stern, R.; Sher, Y.; Le, J.; Klenk, M.; deKleer, J.; Mohan, S. Learning to Operate in Open Worlds by Adapting Planning Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Richland, SC, USA, 29 May – 2 June 2023; AAMAS ’23. pp. 2610–2612. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, R.; Piotrowski, W.; Klenk, M.; de Kleer, J.; Perez, A.; Le, J.; Mohan, S. Model-Based Adaptation to Novelty for Open-World AI. In Proceedings of the ICAPS Workshop on Bridging the Gap Between AI Planning and Learning, Virtual Conference, 13–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Boult, T.; Windesheim, N.; Zhou, S.; Pereyda, C.; Holder, L. Novetly in 3D CartPole Domain. In A Unifying Framework for Formal Theories of Novelty: Discussions, Guidelines, and Examples for Artificial Intelligence; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clary, K. Evaluation of Learned Representations in Open-World Environments for Sequential Decision-Making. In Proceedings of the AAAI Doctoral Consortium, Washington, DC, USA, 7–8 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pereyda, C.; Holder, L. Measuring the Relative Similarity and Difficulty Between AI Benchmark Problems. In Proceedings of the AAAI META-EVAL, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Novelty Level | Effect |

|---|---|

| 0 | No change. |

| 1 | Change to mass of cart. |

| 2 | Block is unmovable in plane of cart. |

| 3 | Blocks initially pushed towards random point. |

| 4 | Change in size of block. |

| 5 | Blocks pushed away from each other. |

| 6 | Gravity increased and does affect blocks. |

| 7 | Blocks attracted to origin. |

| 8 | Additional stopped blocks spawned over time. |

| 9 | Cartpole pole length increase. |

| 10 | Blocks move on fixed axis in plane of cartpole. |

| 11 | Blocks initially pushed towards cartpole. |

| 12 | Increase bounciness of blocks. |

| 13 | Blocks attracted to each other. |

| 14 | Wind force applied. |

| 15 | Blocks pushed towards pole tip. |

| 16 | Additional blocks spawned over time. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereyda, C.; Holder, L. The Artificial Intelligence Quotient (AIQ): Measuring Machine Intelligence Based on Multi-Domain Complexity and Similarity. AI 2025, 6, 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6120313

Pereyda C, Holder L. The Artificial Intelligence Quotient (AIQ): Measuring Machine Intelligence Based on Multi-Domain Complexity and Similarity. AI. 2025; 6(12):313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6120313

Chicago/Turabian StylePereyda, Christopher, and Lawrence Holder. 2025. "The Artificial Intelligence Quotient (AIQ): Measuring Machine Intelligence Based on Multi-Domain Complexity and Similarity" AI 6, no. 12: 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6120313

APA StylePereyda, C., & Holder, L. (2025). The Artificial Intelligence Quotient (AIQ): Measuring Machine Intelligence Based on Multi-Domain Complexity and Similarity. AI, 6(12), 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6120313