Abstract

Electroencephalography (EEG) provides excellent temporal resolution for brain activity analysis but limited spatial resolution at the sensors, making source unmixing essential. Our objective is to enable accurate brain activity analysis from EEG by providing a fast, calibration-free alternative to independent component analysis (ICA) that preserves ICA-like component interpretability for real-time and large-scale use. We introduce a convolutional neural network (CNN) that estimates ICA-like component activations and scalp topographies directly from short, preprocessed EEG epochs, enabling real-time and large-scale analysis. EEG data were acquired from 44 participants during a 40-min lecture on image processing and preprocessed using standard EEGLAB procedures. The CNN was trained to estimate ICA-like components and evaluated against ICA using waveform morphology, spectral characteristics, and scalp topographies. We term the approach “adaptive” because, at test time, it is calibration-free and remains robust to user/session variability, device/montage perturbations, and within-session drift via per-epoch normalization and automated channel quality masking. No online weight updates are performed; robustness arises from these inference-time mechanisms and multi-subject training. The proposed method achieved an average F1-score of 94.9%, precision of 92.9%, recall of 97.2%, and overall accuracy of 93.2%. Moreover, mean processing time per subject was reduced from 332.73 s with ICA to 4.86 s using the CNN, a ~68× improvement. While our primary endpoint is ICA-like decomposition fidelity (waveform, spectral, and scalp-map agreement), the clean/artifact classification metrics are reported only as a downstream utility check confirming that the CNN-ICA outputs remain practically useful for routine quality control. These results show that CNN-based EEG decomposition provides a practical and accurate alternative to ICA, delivering substantial computational gains while preserving signal fidelity and making ICA-like decomposition feasible for real-time and large-scale brain activity analysis in clinical, educational, and research contexts.

1. Introduction

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a widely utilized non-invasive technique for monitoring electrical brain activity, particularly the synchronous firing of pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex. The recorded voltage fluctuations reflect cognitive processes and neuronal coordination across brain networks. Due to its millisecond-level temporal resolution and non-invasive nature, EEG has become indispensable in neuroscience, clinical diagnostics, neural engineering, and cognitive psychology [1,2,3]. It is frequently applied in the diagnosis of epilepsy, sleep disorders, and consciousness impairments, as well as in cognitive and affective research [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Despite its strengths, EEG inherently suffers from limited spatial resolution due to signal attenuation and distortion as electrical potentials propagate through the scalp, skull, and cerebrospinal fluid. This challenge introduces spatial correlation among electrode signals, thereby complicating source localization. As a result, signal separation and enhancement techniques have become essential in EEG research. Conventional analysis pipelines involve sequential stages of preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification, utilizing time-domain, frequency-domain, time-frequency domain, and nonlinear statistical methods [10,11,12,13]. However, these pipelines are computationally costly, assumption-dependent, and often require manual component curation, which limits real-time feasibility and scalability.

Among signal processing methods, independent component analysis (ICA) is one of the most frequently employed for separating artifacts (e.g., eye blinks, muscle noise) from neural sources [14,15]. EEGLAB, a MATLAB (version R2024a)-based toolbox, provides a comprehensive suite of ICA-based preprocessing tools and supports a wide array of EEG formats, visualization methods, and analysis workflows. However, ICA relies on strict assumptions such as linear mixing, statistical independence, and signal stationarity. These assumptions often do not hold in real-world datasets, limiting its effectiveness and scalability [16,17]. Additionally, EEGLAB lacks native support for real-time EEG processing, reducing its applicability in brain–computer interface (BCI) systems and adaptive clinical applications [18]. To address these limitations, machine learning (ML) approaches have gained popularity for EEG signal processing. ML techniques can learn complex and nonlinear patterns from data, enabling classification or prediction without explicit rule-based programming. These methods have been successfully applied to tasks such as mental workload estimation, seizure detection, and motor imagery classification. In particular, deep learning (DL) models, which leverage multiple neural network layers to extract hierarchical features, have shown promise in EEG research [19,20]. However, both the assumptions behind ICA and the intrinsic low spatial resolution of scalp EEG due to volume conduction make source unmixing the central challenge we address next.

EEG signals limited spatial resolution means that each scalp channel captures a mixture of multiple neural and non-neural sources because of volume conduction. This spatial mixing reduces interpretability, blurs region-specific effects, and makes artifact contamination (e.g., ocular or muscle activity) harder to isolate, which can bias condition- or patient-level conclusions. Improving effective spatial resolution therefore requires source unmixing to separate overlapping generators into components with stable scalp topographies and spectra. Our approach targets precisely this need by providing an ICA-like decomposition with real-time, large-scale feasibility, preserving the interpretability of spatially meaningful components while removing the computational bottleneck of ICA.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are especially well-suited for EEG analysis due to their ability to extract spatial-temporal features from raw signals and transformed representations, such as spectrograms and time-frequency maps [21]. CNNs eliminate the need for handcrafted feature extraction and are robust against noise and variability in high-dimensional data. Their end-to-end architecture allows them to learn complex neural signatures directly from input data. While prior research has primarily focused on CNN applications for classifying EEG activity in specific frequency bands, such as alpha (8–13 Hz) and gamma (30–100 Hz), this study targets a more fundamental task: signal decomposition. Rather than applying CNNs to downstream classification problems, this research proposes a CNN-based model that emulates the functionality of ICA as implemented in EEGLAB [22,23,24,25]. This approach addresses core limitations of ICA by removing reliance on prior statistical assumptions and manual intervention, while significantly improving computational efficiency. In this work, CNN-ICA is not introduced as a theoretical alternative to ICA, but rather as a computational surrogate designed to reproduce ICA-like outputs with high fidelity. The approach specifically targets practical limitations of ICA, such as long runtimes and manual intervention, while retaining the interpretability of ICA-derived components.

Once trained, CNN models generalize across sessions and subjects, enabling real-time EEG decomposition and integration into automated systems.

Nonetheless, applying DL to EEG presents challenges, including the risk of overfitting, limited interpretability, and inter-individual variability. These issues necessitate rigorous training, validation, and architectural optimization, as well as hybrid strategies combining DL with domain-specific tools like EEGLAB [26,27,28]. The present study is motivated by these persistent obstacles. While ICA remains widely used, it is computationally expensive, statistically constrained, and often requires manual component curation, which limits its feasibility for high-throughput and real-time applications. Recurrent neural networks [29], particularly long short-term memory [30] models, have been widely applied to EEG analysis because of their ability to capture long-range temporal dependencies. However, CNNs offer complementary advantages: they capture local spatiotemporal patterns within short epochs, require fewer parameters, and achieve faster training and inference. Given the scale of our dataset and our focus on real-time feasibility, we selected a CNN framework as the most efficient approach for approximating ICA outputs.

CNNs present a promising alternative to traditional EEG decomposition methods, as they are capable of learning data-driven representations directly from raw signals without relying on restrictive statistical assumptions. Once trained, these models provide fast and reliable inference, enabling seamless integration into real-time analysis pipelines. Their scalability makes them suitable for a wide range of applications, including clinical diagnostics, cognitive neuroscience, and educational technologies. Moreover, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven EEG processing is gaining increasing attention in neurology and psychiatry for purposes such as real-time monitoring, adaptive neurofeedback, and personalized interventions [31,32,33], as well as in educational settings for cognitive assessment and engagement analysis [34,35].

Whereas prior CNN–EEG research has largely centered on classification tasks such as seizure detection or abnormal EEG identification [36,37,38], the present study addresses a fundamentally different goal: the development of a CNN-based surrogate for ICA signal decomposition. Rather than labeling EEG epochs, the proposed model learns to replicate ICA-derived components at the signal level, validated using correlation, mean squared error, and spectral cosine similarity. This decomposition-oriented framing distinguishes our contribution from classification-focused CNN studies and positions the method as a practical and computationally efficient alternative to conventional ICA.

Accordingly, we seek an inference-time adaptive solution: robust to inter-subject and inter-session variability, resilient to device/channel perturbations or dropouts, and stable under gradual behavioral or statistical drift, while avoiding any per-user calibration or online retraining. In large-scale EEG, high sampling rates and inter-subject/device heterogeneity impose substantial computational load and practical scheduling constraints on modern CPU/GPU systems; our goal is an inference-time efficient, calibration-free decomposition that meets real-time latency budgets via per-epoch processing, parallelizable preprocessing, and batched CNN inference.

In this study, a CNN framework is introduced that emulates ICA while remaining calibration-free and efficient, demonstrating ICA-level fidelity, generalization across users/sessions and devices/montages, and scalability for real-time and large-scale EEG analysis. The proposed model is designed to generalize across subjects and experimental sessions, making it suitable for real-time EEG analysis. This scalable and automated approach supports next-generation EEG processing pipelines in clinical, research, and educational settings, where speed, reliability, and minimal manual intervention are critical. This work introduces a CNN-based surrogate for ICA that directly regresses sensor-level signals toward EEGLAB-ICA outputs, validated for temporal, amplitude, and spectral fidelity across 64 channels and 44 participants, and benchmarked for runtime to demonstrate substantial speedup suitable for real-time and large-scale EEG analysis. Our goal is to deliver an ICA-like decomposition that is calibration-free and fast enough for real-time and large-scale brain activity analysis. Specifically, we (i) evaluate fidelity to ICA using component morphology, spectra, and scalp topographies together with F1, precision, recall, and accuracy; (ii) quantify efficiency by measuring per-subject runtime; and (iii) assess practical robustness across users/sessions, devices/montages, and within-session drift using per-epoch normalization and automated channel quality masking, with fixed model weights at test time. These objectives define the scope of the study and organize the results.

This study situates its contribution squarely within artificial intelligence (AI) by casting EEG source unmixing as supervised model distillation. A convolutional neural network is trained to emulate independent component analysis, producing ICA-like component activations, spectra, and scalp topographies through a single feed-forward pass rather than iterative optimization. The approach preserves interpretability while introducing systems-level efficiency: multi-subject training, per-epoch normalization, and automated channel quality masking yield inference-time robustness and generalization to unseen subjects, sessions, and device or montage variations. Under subject-independent evaluation, the model attains fidelity comparable to ICA with a substantial reduction in runtime (on the order of tens of times faster), enabling real-time and large-scale deployment. By replacing a computationally intensive optimization procedure with a learned surrogate that is both interpretable and reliable, the work advances core AI objectives in algorithmic distillation, generalization, and efficient deployment for biosignal analysis.

2. Experiment and Pre-Processing

An experimental study was conducted involving 44 undergraduate students who attended a 40-min lecture on image processing, specifically focusing on image contrast. This topic was chosen to deliver sustained, structured visual stimulation and a consistent attention load while limiting movement and speech, thereby reducing artifacts. The lecture content included definitions of contrast, demonstrations of histogram equalization on example images, and short instructor prompts, providing continuous, naturalistic EEG suitable for large-scale evaluation of the proposed method.

During the session, participants’ brain activity was recorded in real time using the eego™ mylab EEG system (ANT Neuro, Hengelo, Netherlands). The dataset comprised 44 undergraduate students (mean age = 25.1 years, age range of 21–31, 35 males, 10 females), recruited via voluntary sign-up in laboratory courses. Inclusion criteria were normal or corrected-to-normal vision and no self-reported neurological or psychiatric disorders. The sample represents a convenience group intended for methodological validation of CNN-ICA rather than population-level inference. Across 44 participants, 40-min sessions segmented into 2-s epochs yield ≈ 5.3 × 104 epochs; analyses focus on ICA-like component fidelity (waveform morphology, spectral characteristics, scalp topographies) rather than high-resolution source localization.

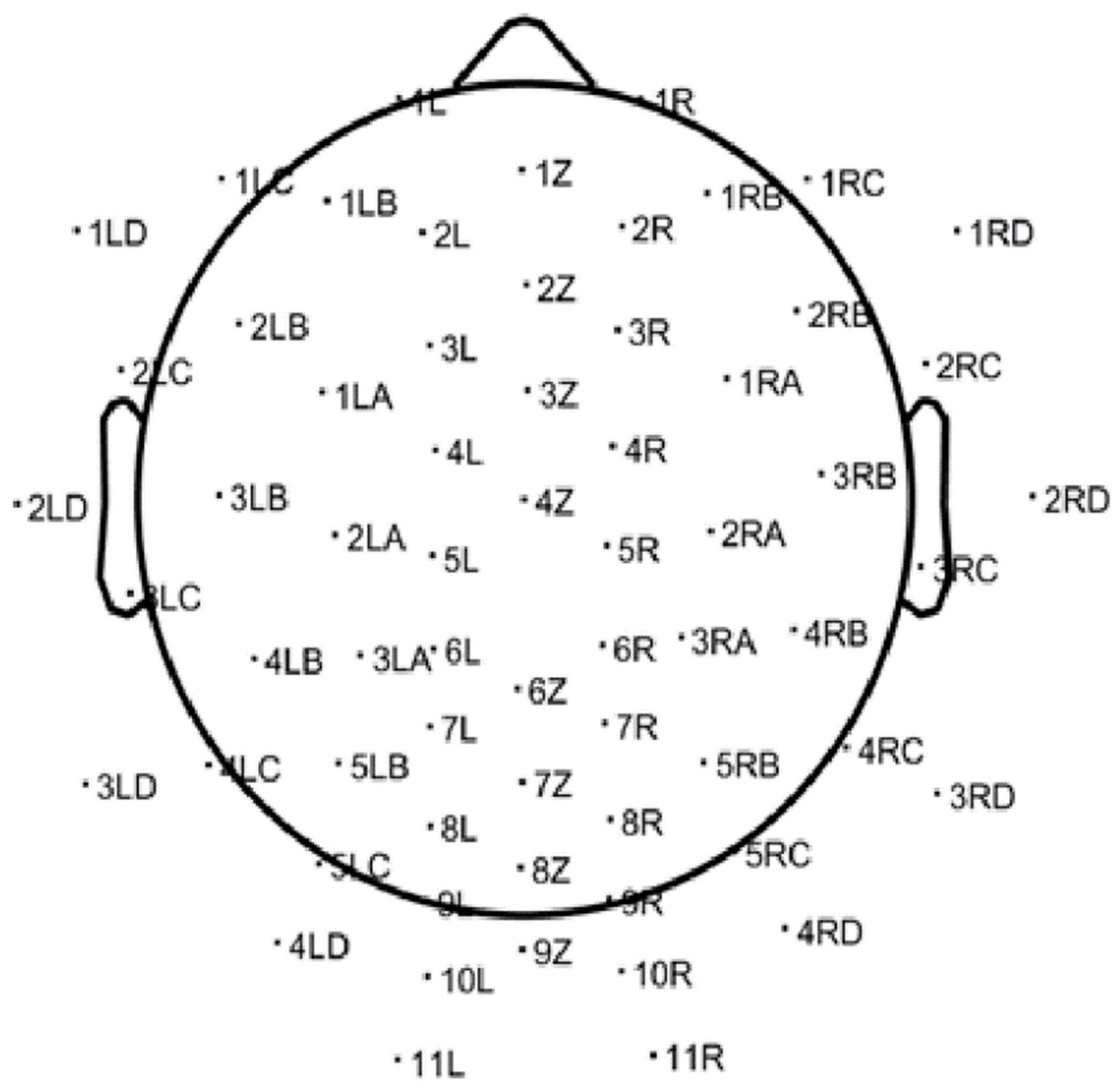

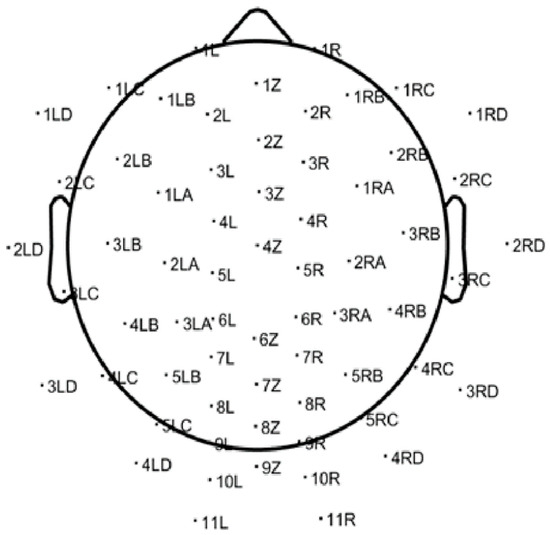

Recordings targeted the alpha frequency band (8–13 Hz) and were acquired using a 64-channel EEG headset at a sampling rate of 500 Hz. The raw EEG data were saved in ANT EEProbe CNT file format and subsequently processed using the EEGLAB toolbox (version 2022) within the MATLAB environment. EEGLAB’s native import function was used to load the CNT files. Following import, electrode positions were registered using a standardized 64-channel electrode location file, enabling spatial mapping of each channel across the scalp. These mappings, as shown in Figure 1, provided anatomical context for subsequent signal analysis and interpretation.

Figure 1.

Standard 64-channel electrode layout used for EEG acquisition, as visualized in EEGLAB. This scalp map provides spatial references for the cortical sources of the recorded brain activity.

The EEG preprocessing pipeline was developed to prepare raw recordings for machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) tasks, with a specific focus on alpha-band activity (8–13 Hz). The primary objective was to clean, segment, and normalize the data in a consistent manner across all participants, thereby ensuring compatibility with downstream computational models.

The process began with the application of a bandpass filter to isolate the alpha frequency range. Following filtering, signal quality was assessed on a per-channel basis using the standard deviation as a measure of variability. Channels were considered noisy if their standard deviation exceeded a predefined threshold of 15 µV. These channels were marked as poor quality and excluded from further analysis by setting their values to zero.

After minimizing the impact of noisy channels, the continuous EEG signals were segmented into non-overlapping epochs of 2 s each. The segmented data were then reshaped into a three-dimensional tensor with dimensions [epochs × channels × time], which is compatible with most ML and DL frameworks.

Finally, each epoch was normalized using the global mean and standard deviation calculated across all epochs and time points, as expressed in Equation (1)

where is a single element in a 3D matrix. and are the global mean and the standard deviation of the 3D matrix respectfully.

Following segmentation, the dataset comprised approximately 1200 non-overlapping 2-s epochs per participant, yielding a total of 52,800 epochs across 44 subjects. Data were split at the participant level. We used grouped K-fold cross-validation (subjects as the grouping unit) for model selection with a 70/10/20 train/validation/test partition by participant, reserving a subject-independent 20% hold-out test set for final evaluation only. Concretely, this corresponds to approximately 31 train, 5 validation, and 8 test participants (40-min sessions, ~1200 2-s epochs per subject; ~37.2 k/6.0 k/9.6 k epochs, respectively). All preprocessing statistics were computed per epoch; hyperparameter tuning and early stopping used validation only, and no information from test subjects was used during training or tuning. During data acquisition, participants engaged in a 40-min lecture on image processing, which provided a naturalistic yet consistent cognitive context across the cohort. Quality-control safeguards included automated channel rejection (standard-deviation threshold = 15 µV), bandpass filtering (8–13 Hz), and normalization of each epoch. A natural dropout procedure was applied to mask noisy channels, ensuring consistent input dimensionality across participants. All preprocessing steps were implemented in EEGLAB (2022) with custom MATLAB scripts to guarantee reproducibility. The resulting dataset was anonymized and aligned with institutional ethical standards.

For ICA decomposition, the Extended Infomax algorithm (EEGLAB function runica, with the “extended = 1” option) was applied to each dataset. This implementation is the stand and default in EEGLAB and has been widely adopted in EEG research. The choice of Infomax ensured consistency with prior work and reproducibility of the ICA ground-truth signals used as training targets.

To support adaptive inference, we apply automated channel quality screening with masking of noisy electrodes and per-epoch global normalization across channels and time. The CNN is trained on multi-subject data and applied per epoch with the same normalization/masking, yielding a calibration-free pipeline that tolerates user/session/device variability without online weight updates. After preprocessing, the data are ready for input to the CNN.

3. Materials and Theory

3.1. CNN Model

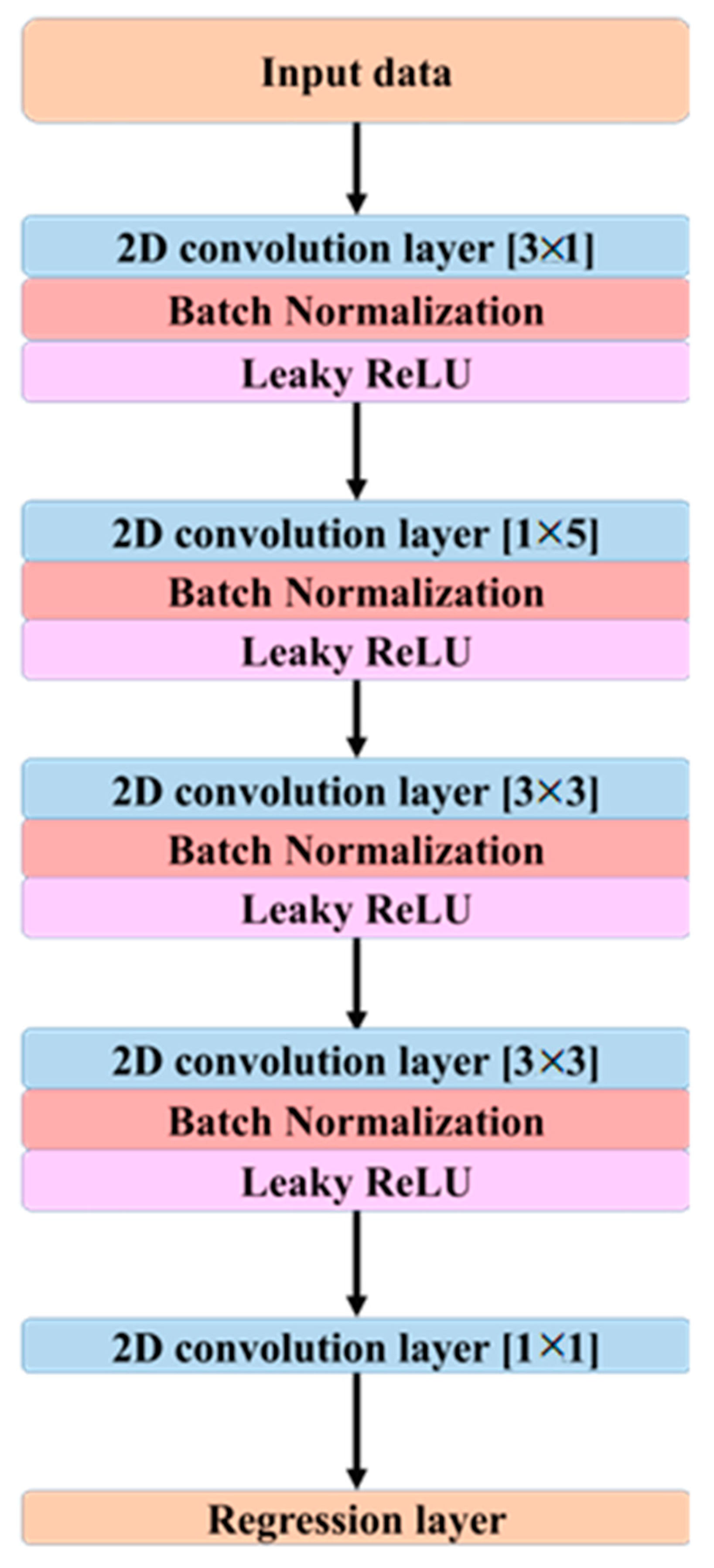

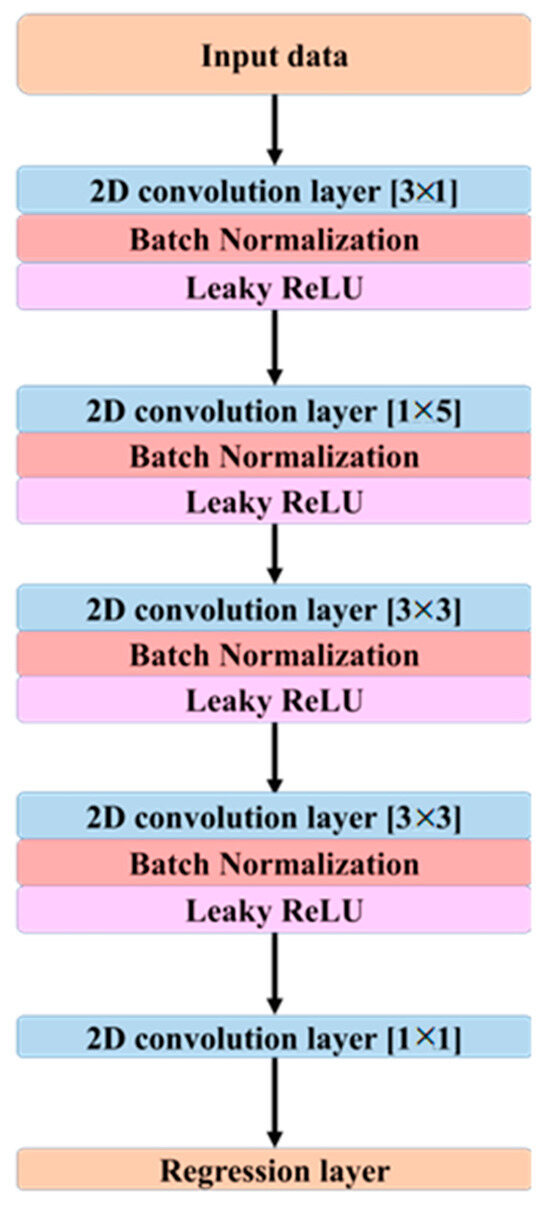

Figure 2 outlines the CNN model architecture which was used to analyze the data:

Figure 2.

Architecture of the proposed CNN model designed for EEG signal decomposition and ICA approximation. The network consists of multiple 2D convolutional layers with varying kernel sizes, each followed by batch normalization and Leaky ReLU activation. A final regression layer outputs the reconstructed component signals.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the proposed CNN architecture employs a series of 2D convolutional layers to extract spatial and temporal features from the EEG data. The first convolutional layer applies a kernel of size [3 × 1], which captures spatial dependencies across multiple channels at a single time point. The second layer utilizes a [1 × 5] kernel to extract temporal patterns from a single channel across consecutive time samples. The third convolutional layer employs a [3 × 3] kernel to integrate spatio-temporal features, while the fourth layer, also using a [3 × 3] kernel, refines the extracted features further to enhance signal representation.

Although the network does not include recurrent or attention mechanisms, temporal dependencies are captured implicitly via temporal convolutions applied within each 2-s epoch. In particular, kernels of size [1 × 5] act along time and [3 × 1] act across neighboring channels, while [3 × 3] layers integrate spatio-temporal patterns. With stride of 1 and dilation of 1 throughout, stacking these layers expands the effective temporal receptive field, allowing the model to aggregate longer-range context without the computational overhead of recurrent architectures. The objective is not to replace the theory of ICA but to learn a direct, data-driven mapping from preprocessed sensor signals to ICA-processed sensor outputs with high fidelity and efficiency suitable for real-time use. Each 40-min recording (500 Hz) yielded 1200 non-overlapping 2-s epochs per participant (total 52,800 epochs across 44 participants), with inputs and targets shaped as 64 × 1000 per epoch.

Each convolutional layer is followed by a batch normalization operation, which maintains activation values within a stable range, thereby improving training stability and accelerating convergence. Leaky ReLU is employed as the activation function throughout the network. The Leaky ReLU activation function is defined in Equation (2).

where is the argument of the function and controls the functions slope for negative inputs and it’s in the range of 0.3 to 0.01 and in this study the value set to 0.1 to allow negative values to have a more significant impact, which can lead to faster learning.

Additionally, an implicit form of dropout is applied at the input layer. The choice of LeakyReLU as the activation function was specifically motivated by its ability to maintain gradient flow even when negative output values are encountered, effectively mitigating the vanishing gradient problem commonly associated with standard ReLU activation.

As the model’s layers are connected sequentially, the increasing depth enables a gradual transition from learning simple, localized features in the initial layers such as edges or basic temporal patterns to capturing more complex, abstract, and hierarchical spatio-temporal relationships in the deeper layers, which are essential for understanding higher-order structures and dynamics within the data.

3.2. Model Performance Evaluation

To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, a comprehensive assessment was conducted during the inference phase. The trained CNN was applied to previously unseen EEG data in order to generate predictions based on the learned spatio-temporal patterns. The evaluation addressed both computational efficiency and predictive quality, using four key quantitative metrics: execution time, classification accuracy, precision-recall-based measures (including the F1-score), and waveform alignment.

In addition to these quantitative metrics, waveform alignment was also inspected visually by two experienced EEG analysts as a supplementary qualitative check, providing confirmation that the CNN outputs were consistent with the quantitative findings. Runtime was recorded for critical stages including training, inference, and evaluation. These measurements provided insight into the computational cost and potential scalability of the model for real-time or high-throughput applications. Classification performance was evaluated using four widely used metrics [39]: accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1-score. These measures provide complementary perspectives, with accuracy offering an overall estimate of predictive correctness, precision reflecting the reliability of positive predictions, recall indicating sensitivity to positive cases, and the F1-score balancing both. As these definitions are standard in the machine learning literature, the corresponding formulas are not restated here.

For validation, CNN-ICA outputs were compared with decompositions obtained from EEGLAB-ICA, which is widely used as a standard benchmark in EEG studies. EEGLAB-ICA is not treated as a gold standard, but rather as a reference point for assessing the fidelity of the proposed method. To objectively assess how closely the CNN-ICA decomposition replicates the conventional EEGLAB-ICA outputs, three complementary similarity measures were computed which are pearson correlation coefficient (r), mean squared error (MSE) and spectral cosine similarity (CosSim). The r metric evaluates the temporal alignment between CNN-ICA and EEGLAB-ICA signals which given by

where XEEGLAB(t) and XCNN(t) represent the temporal samples of EEGLAB-ICA and CNN-ICA signals, respectively. are the means over the epoch.

The MSE reflects the average squared amplitude deviation between CNN-ICA and EEGLAB-ICA outputs and given by

where T is the number of temporal samples in the epoch.

To compare spectral fidelity, the power spectral density (PSD) of CNN-ICA and EEGLAB-ICA signals was computed, and cosine similarity is given by

where PEEGLAB(f) and PCNN(f) denote the PSD values at frequency f. A CosSim close to 1 indicates highly similar spectral distributions.

Supervised targets (‘ground truth’) were obtained by running EEGLAB-ICA on the band-passed EEG and using the resulting sensor-level ICA-processed signals aligned to each 2-s epoch as reference outputs. Thus, the training objective explicitly optimizes a surrogate mapping from raw/preprocessed EEG to ICA-like sensor signals. Quantitative similarity was assessed with r, MSE, and CosSim across all channels and participants.

Binary labels were derived deterministically from the continuous CNN-ICA outputs at 2-s resolution. For each channel × epoch, an artifact score was computed from standard EEG quality-control features extracted from the CNN-ICA sensor-level signals: z-scored peak-to-peak amplitude, kurtosis, high-frequency power ratio, and a 50/60-Hz line-noise ratio. A segment was labeled artifact if any criterion was met; |z-scored peak-to-peak amplitude| > 3.5; kurtosis > 5; high- to low-frequency power ratio (30–80 Hz/8–13 Hz) > 1.5; line-noise ratio (50/60 Hz ±1 Hz band/baseline) > 1.3; otherwise, it was labeled clean. Thresholds were fixed on the training set using Youden’s J on ROC curves and were applied unchanged to validation and test. All reported classification metrics and Figure 10 use artifact as the positive class. This procedure converts the continuous decomposition into reproducible binary labels without manual curation.

4. Decoding Results

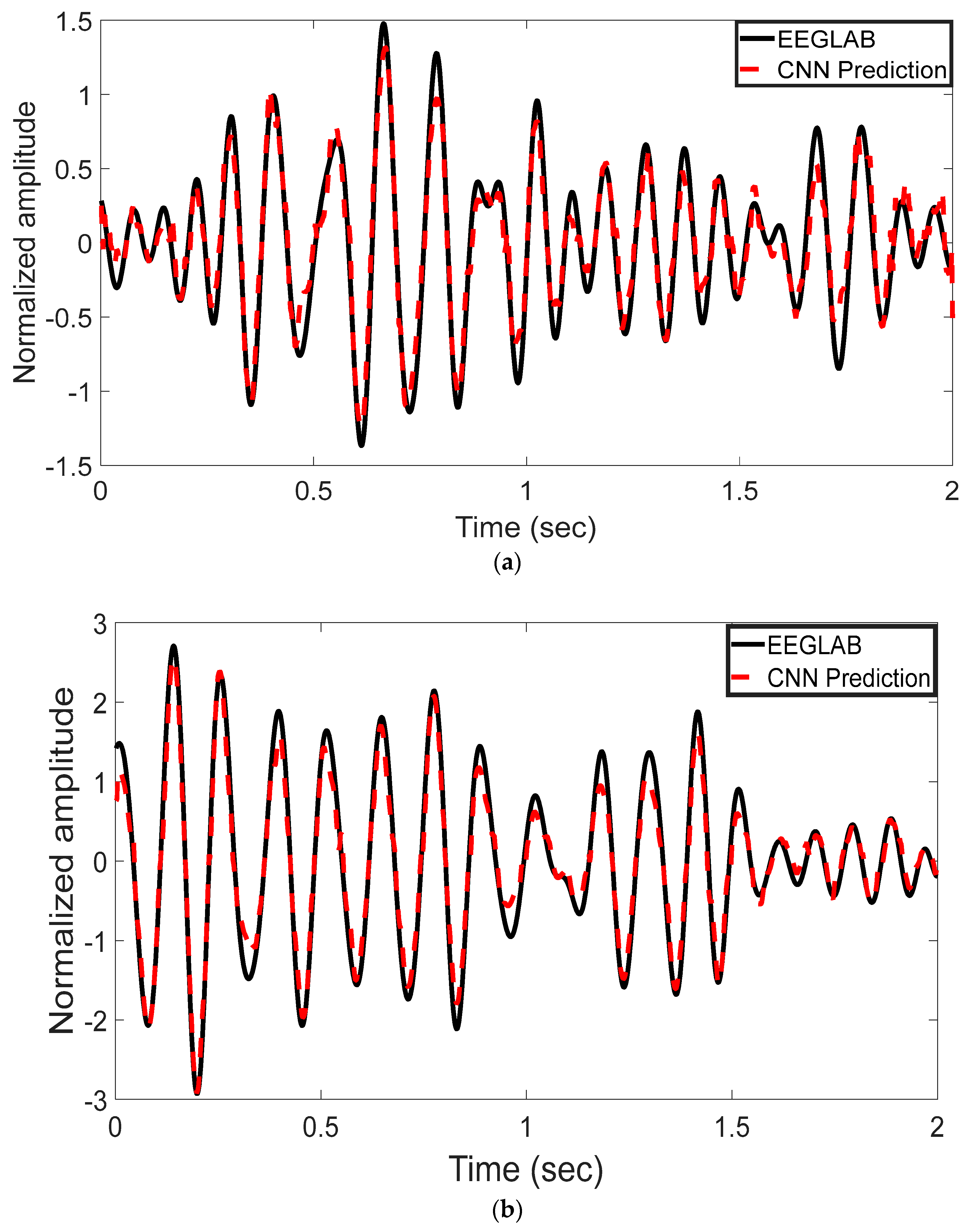

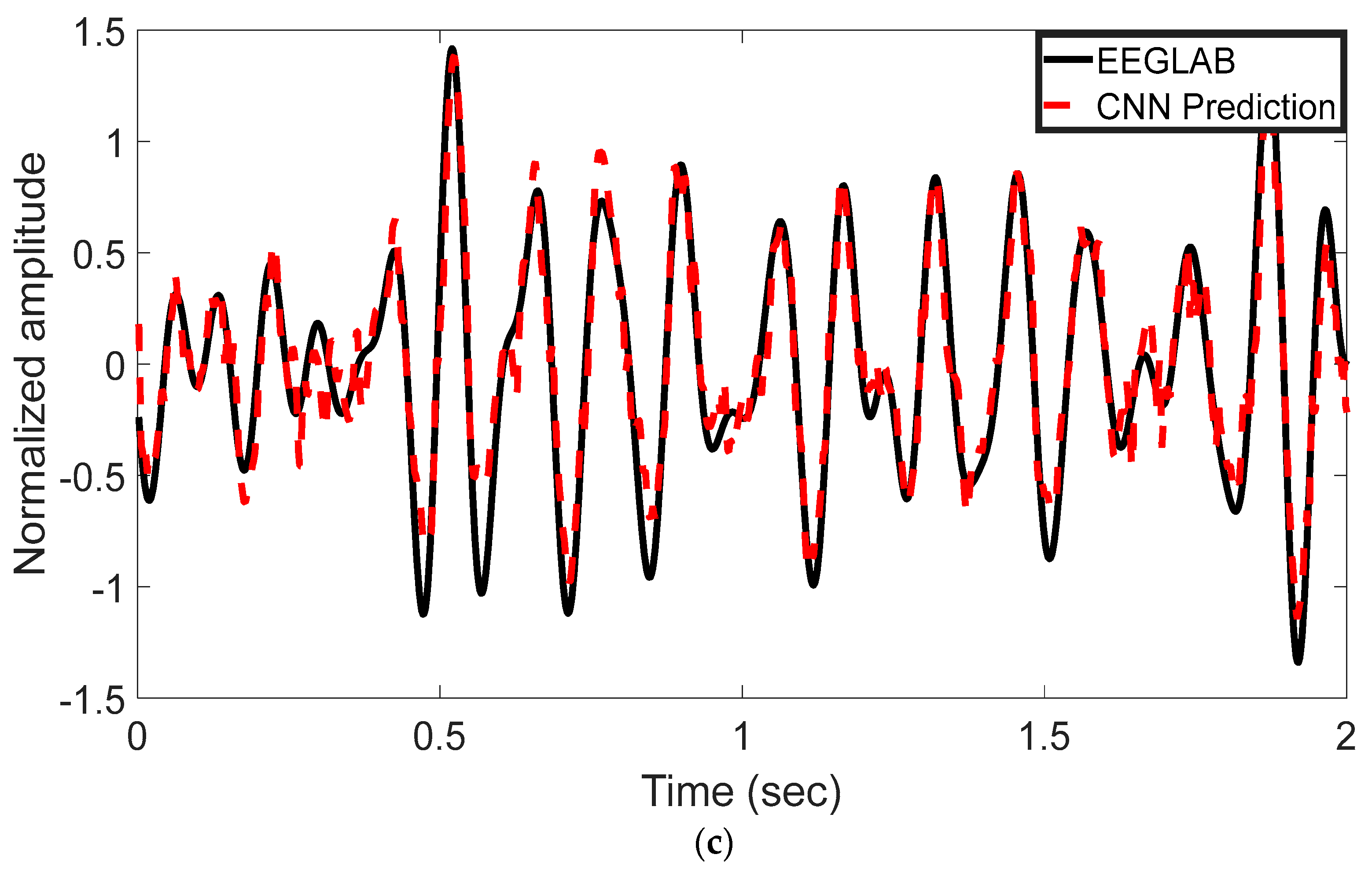

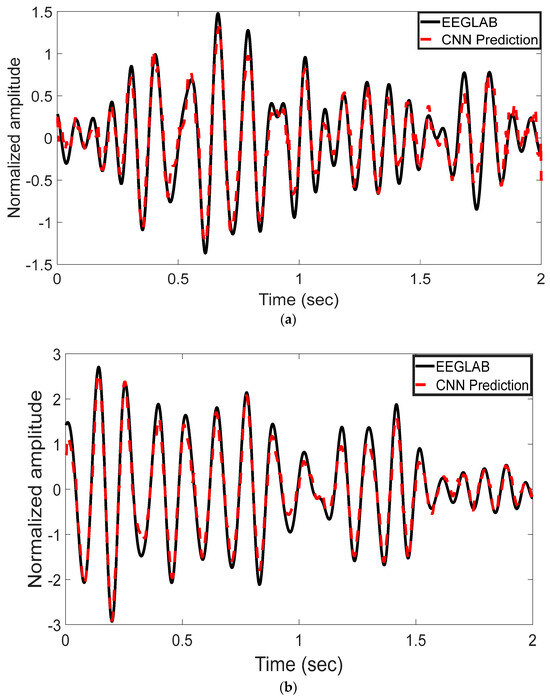

The EEG signal decoding process was performed using MATLAB R2022b. The experimental results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed CNN-based approach for automated analysis of EEG signals in the 8–13 Hz alpha frequency band. Reported test metrics are from the subject-independent 20% hold-out; grouped cross-validation (by subject) shows consistent trends. This method was evaluated for its ability to reconstruct and classify neural activity with high accuracy. Time-domain representations of the EEG signals were used to assess the model’s reconstruction performance. As shown in Figure 3a–c, the CNN model’s predictions (represented by red dashed lines) are plotted alongside the ICA-derived outputs from EEGLAB (depicted by black solid lines). These comparisons were conducted across multiple test epochs and electrode channels. The CNN model exhibited strong agreement with the ICA outputs, effectively capturing the temporal waveform characteristics of the underlying EEG components. Representative results are shown for channel 1LD in Figure 3a, channel 2L in Figure 3b, and channel 5LB in Figure 3c. The visual similarities observed across these channels support the model’s ability to replicate ICA-like signal decomposition with high fidelity.

Figure 3.

Time-domain comparison between CNN predictions and ICA-derived signals across three EEG channels. (a) Channel 1LD, test epoch 3; (b) Channel 2L, test epoch 4; (c) Channel 5LB, test epoch 5. The black solid line represents the EEGLAB ICA output, and the red dashed line denotes the CNN-based prediction. The CNN model closely approximates the ICA waveform across all channels, capturing key temporal dynamics.

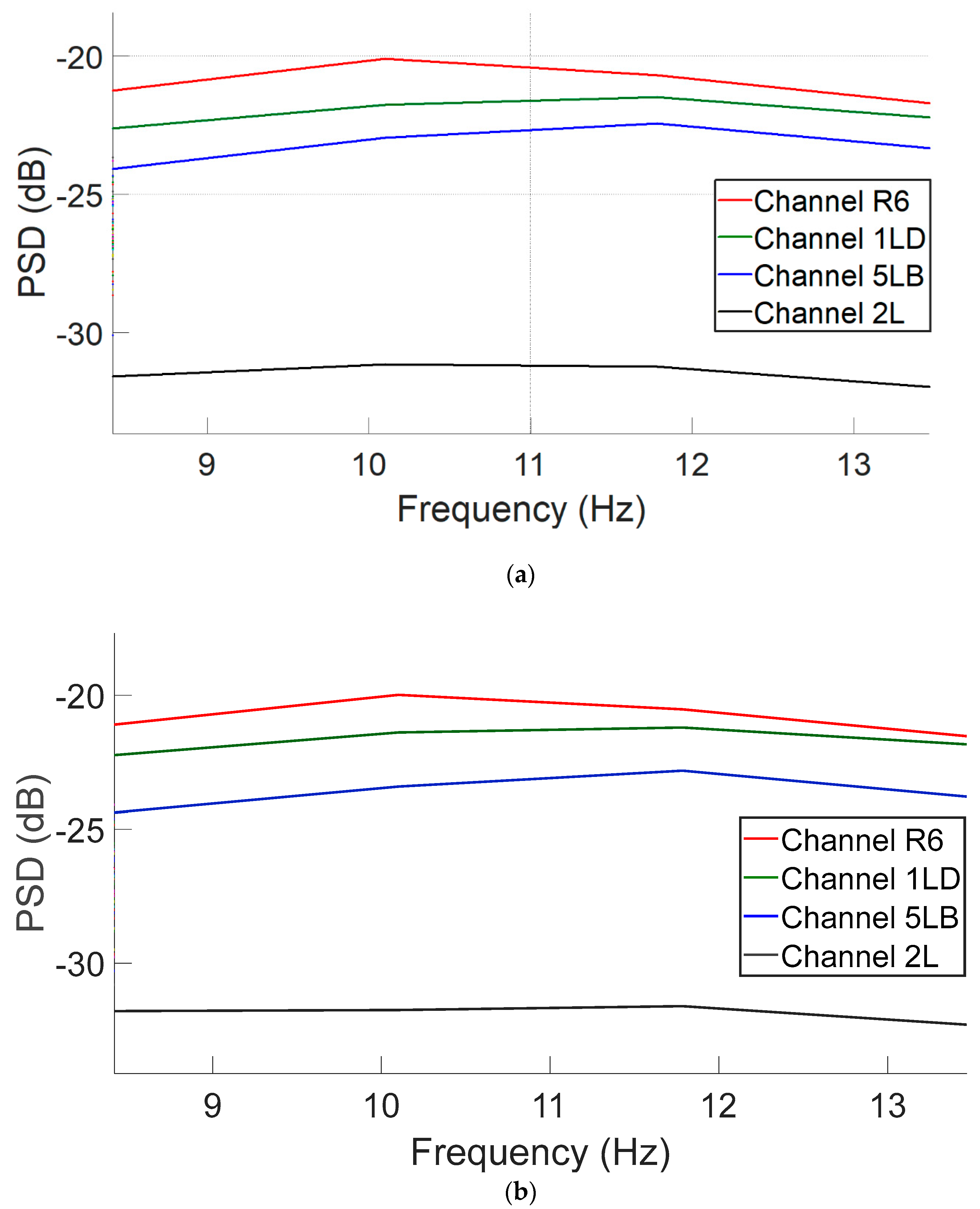

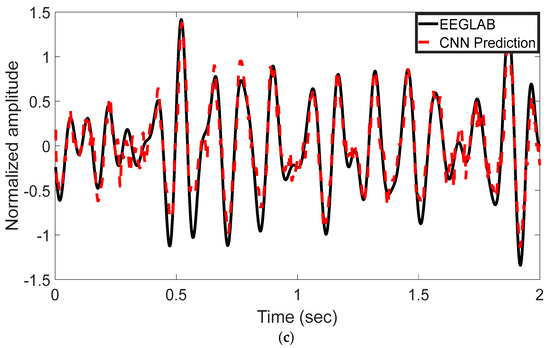

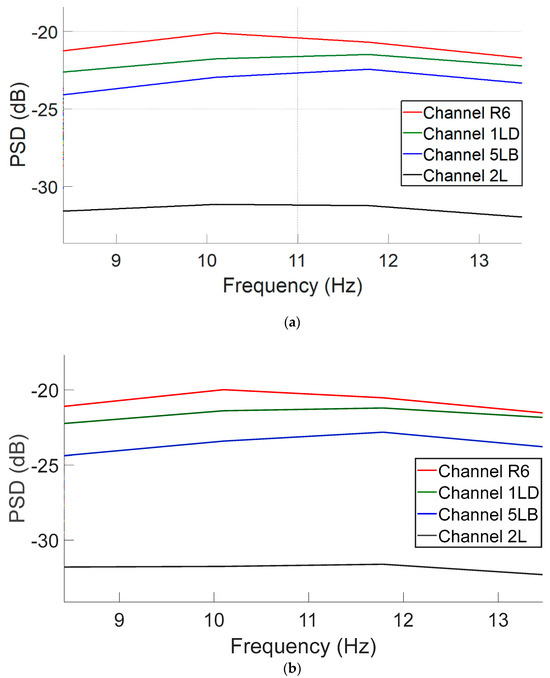

Figure 4a,b illustrate the power spectral density (PSD) distributions following ICA decomposition using the EEGLAB method and the proposed CNN-based model, respectively. The plots compare post-ICA PSD curves across EEG channels. As shown, both methods yield highly similar spectral profiles, with only minor differences in amplitude across the frequency spectrum. This suggests that the CNN model is capable of effectively approximating the spectral characteristics of traditional ICA-based processing. This analysis reveals that similar spectral behavior is observed across additional EEG channels, thereby confirming that the spectral profiles produced by the CNN-based model closely align with those generated by traditional ICA. These findings indicate that the CNN model effectively replicates the frequency characteristics of ICA across the entire channel set.

Figure 4.

PSD curves in the 8–13 Hz alpha band range for four representative EEG channels following ICA decomposition: (a) EEGLAB-derived components and (b) CNN-predicted components.

To move beyond illustrative examples, we applied the similarity metrics defined in Equations (3)–(5) across all 64 channels and 44 participants, in combination with our proposed decoding method. For each metric, we calculated the mean and standard deviation (STD) across the entire dataset. As summarized in Table 1, the CNN-ICA outputs showed high agreement with EEGLAB-ICA (r = 0.93 ± 0.03, MSE = 0.018 ± 0.007, CosSim = 0.96 ± 0.02), confirming strong temporal, amplitude, and spectral fidelity while substantially reducing computational time.

Table 1.

Similarity metrics comparing CNN-ICA and EEGLAB-ICA Outputs.

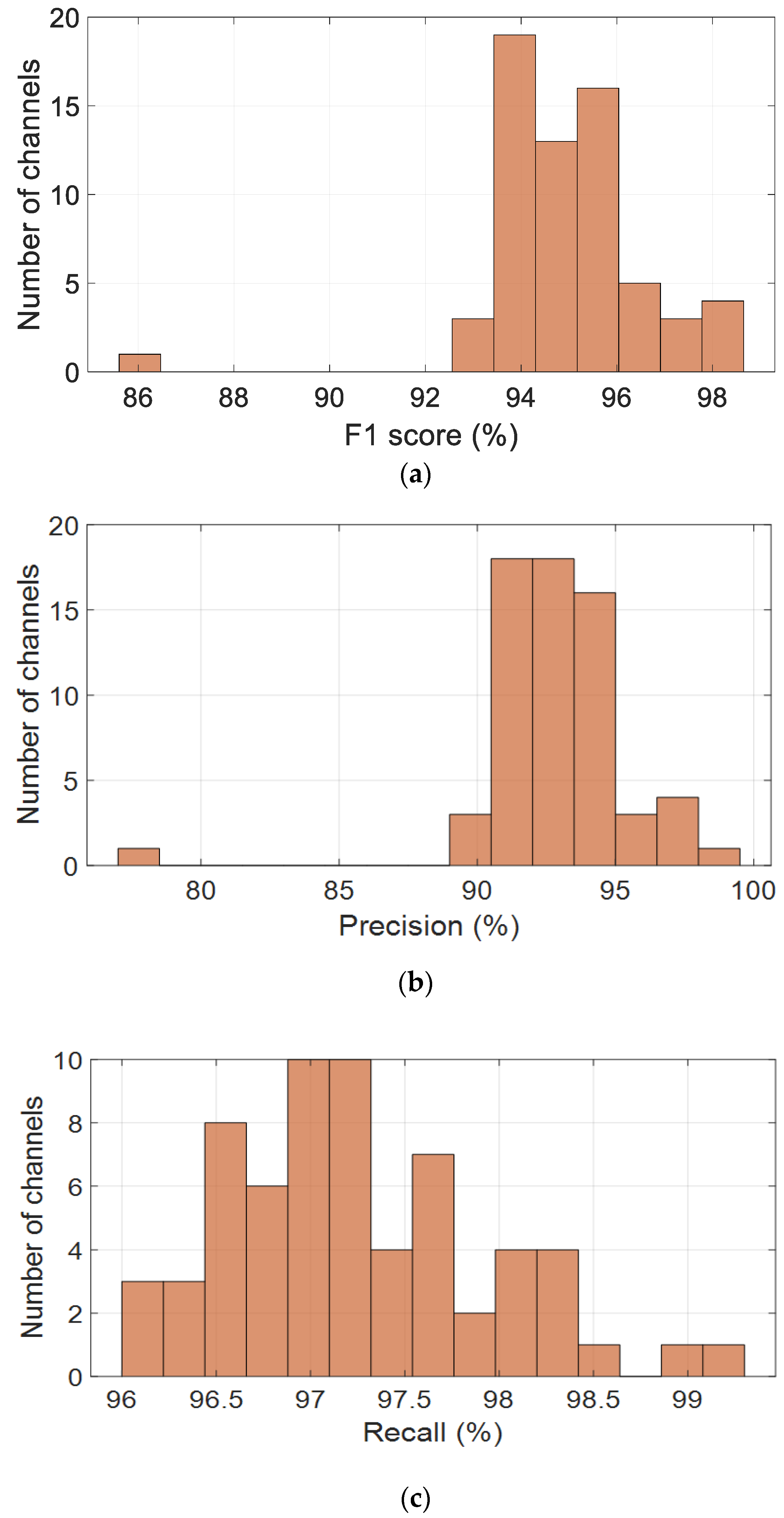

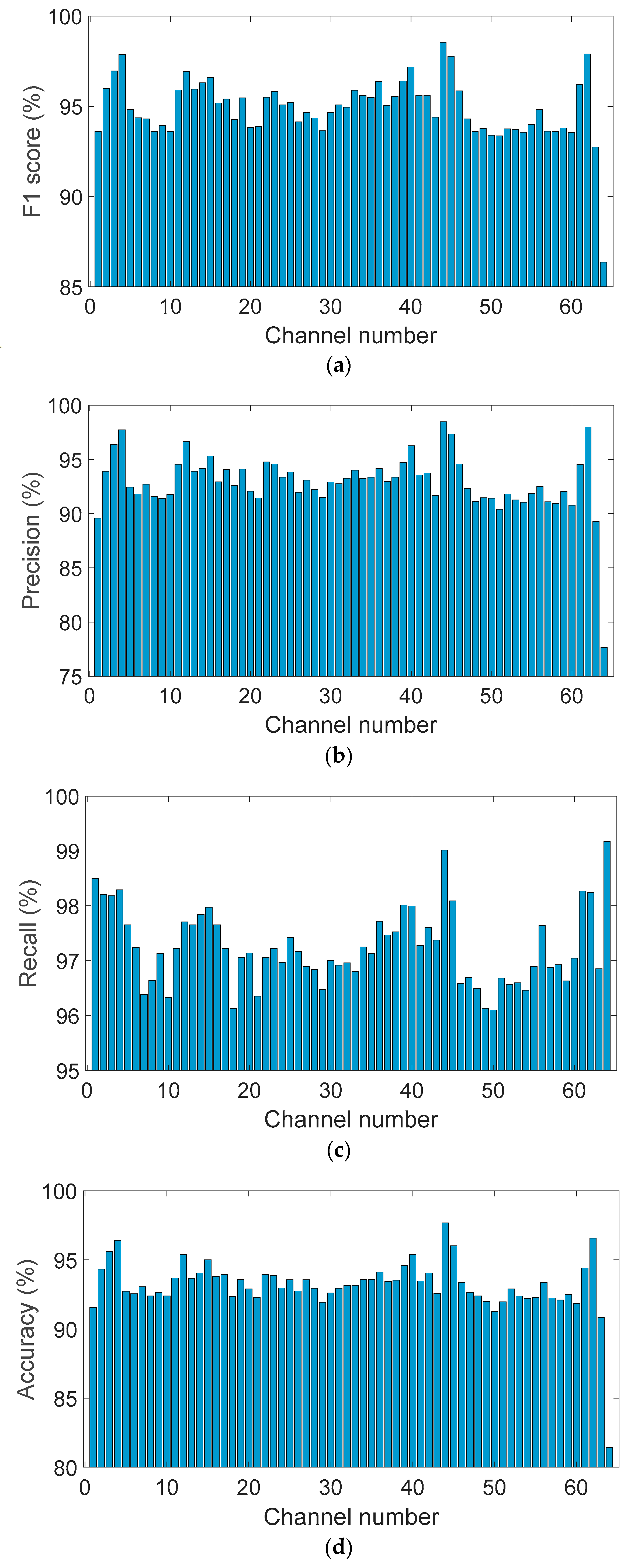

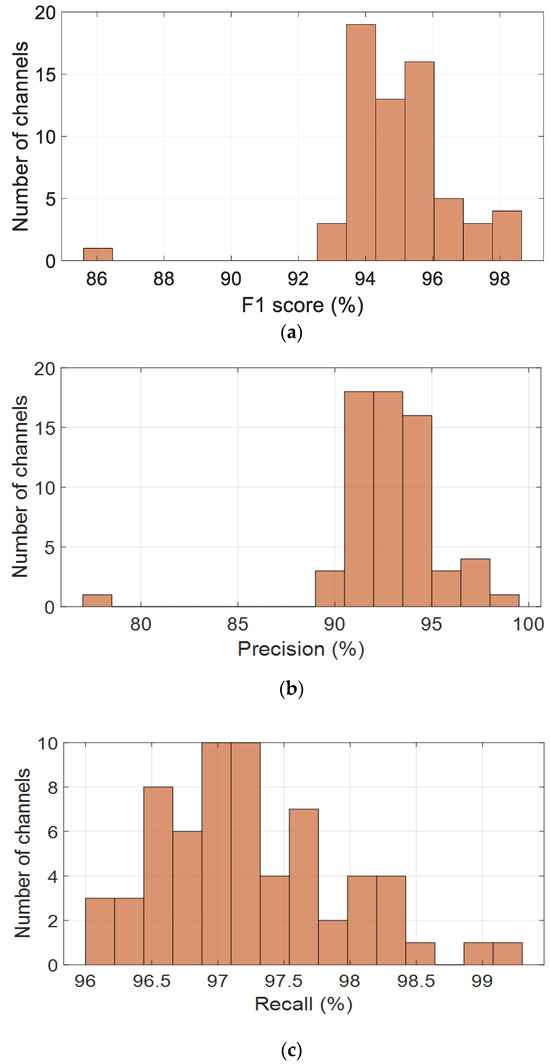

To evaluate the performance of the proposed CNN-based model across the spatial domain of EEG recordings, four key classification metrics were computed per channel and visualized as histograms, as shown in Figure 5. These metrics include the F1-score, precision, recall, and accuracy, providing a comprehensive assessment of the model’s robustness across all 64 channels.

Figure 5.

Channel-wise performance distribution of the CNN model across the alpha band (8–13 Hz), based on key classification metrics: (a) F1-score, (b) precision, (c) recall, and (d) accuracy.

Figure 5a presents the distribution of F1-scores, which are consistently high across most channels, with values clustered between 93% and 96%. The average F1-score is 94.9%, with a standard deviation of 1.7%, indicating stable and reliable performance. Precision values, shown in Figure 5b, are slightly more dispersed but remain concentrated between 90% and 96%, peaking around 93–94%. The average precision is 92.90%, with a standard deviation of 2.75%, suggesting strong predictive accuracy, although a few channels may contribute to occasional false positives.

Recall values, illustrated in Figure 5c, are tightly distributed, with most channels falling between 96% and 98.5%. The mean recall is 97.24%, accompanied by a low standard deviation of 0.68%, demonstrating the model’s excellent ability to detect true positives across the EEG channels. This high recall rate is particularly advantageous for EEG-based cognitive monitoring, where missed detections are critical.

As shown in Figure 5d, accuracy scores follow a similar pattern, with most values ranging from 91% to 95%. The mean accuracy is 93.16%, with a standard deviation of 1.98%, indicating that the model generalizes well spatially. A small number of outlier channels with lower performance suggest the need for further investigation, potentially due to individual variability or local noise artifacts.

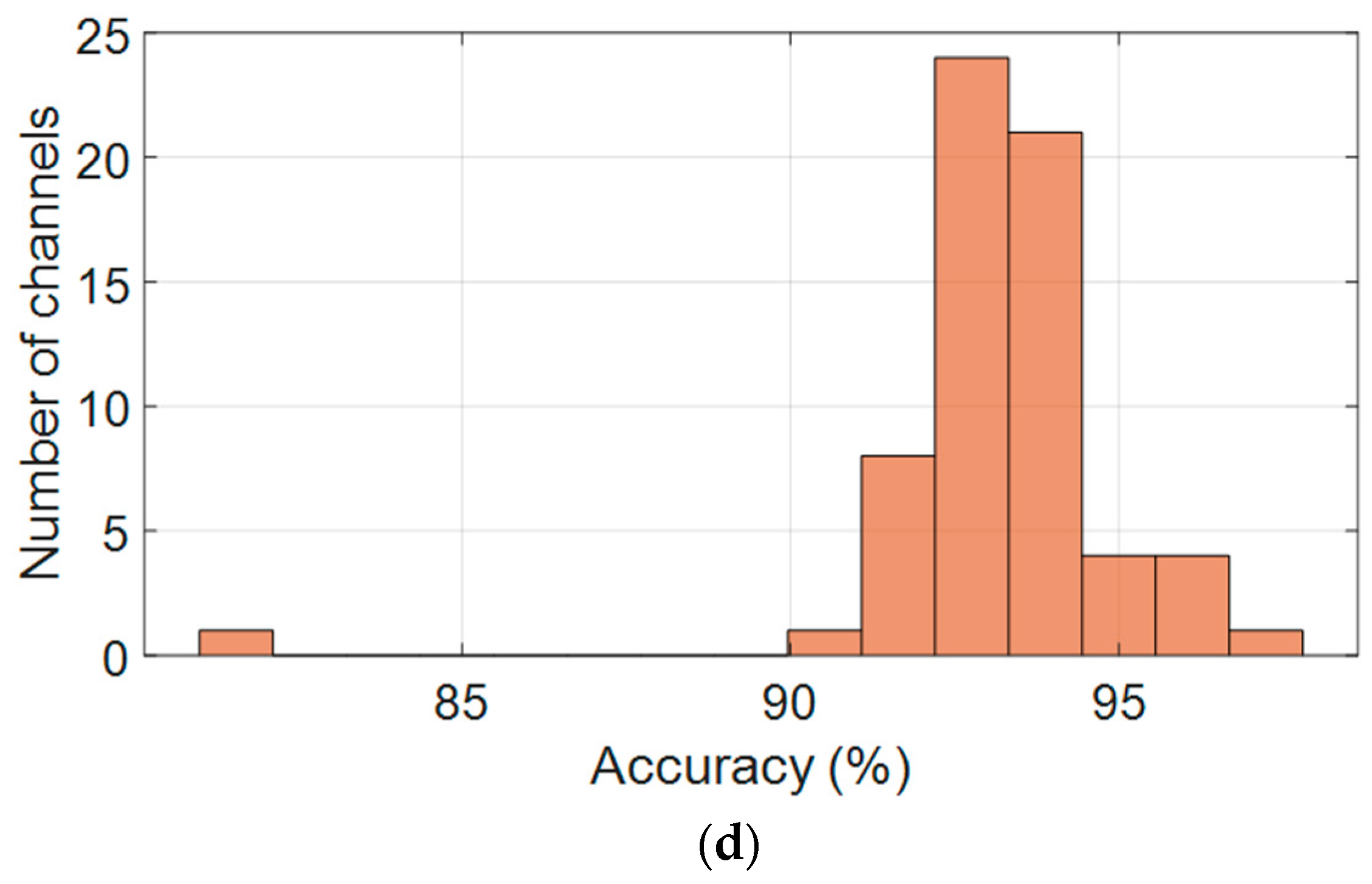

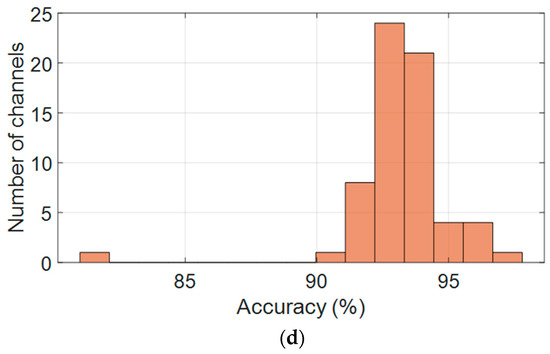

Figure 6a presents the per-channel F1-scores, demonstrating consistent classification performance across the full set of 64 EEG electrodes. The model achieved an average F1-score of 94.9% ± 1.7%, with the majority of channels ranging between 90% and 98%. These results indicate strong generalization capability across spatial locations, with minimal degradation in performance across any particular subset of electrodes.

Figure 6.

Per-channel performance metrics across all 64 EEG electrodes: (a) F1-score, (b) Precision, (c) Recall, and (d) Accuracy.

Figure 6b shows the distribution of precision values per channel. While precision was slightly more variable than the F1-score, it maintained a robust average of 92.9% ± 2.8%. Most electrodes achieved precision above 90%, although a limited number of channels exhibited lower scores approaching 88%, suggesting isolated tendencies toward false-positive predictions in specific scalp regions. Nevertheless, the distribution remained narrow, underscoring the model’s specificity.

Figure 6c illustrates the channel-wise recall distribution, which emerged as the most stable metric across the dataset. The average recall was 97.24% ± 0.7%, with most values clustered between 96% and 98.5%, and some channels exceeding 99%. This strong consistency reflects the model’s high sensitivity and reliable detection of true positives across all regions of the scalp, irrespective of anatomical or noise-related variation.

Figure 6d displays the per-channel accuracy scores. Accuracy values were tightly grouped between 91% and 95%, with an average of 93.16% ± 2.0%. A small number of outlier channels showed slightly reduced accuracy, likely due to localized signal artifacts; however, no spatial trend of underperformance was observed.

Taken together, these spatial performance metrics confirm that the proposed CNN model delivers balanced and robust classification across all EEG channels. Its consistent accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score across the electrode array highlight its suitability for real-time, full-head EEG decoding and scalable large-cohort analysis.

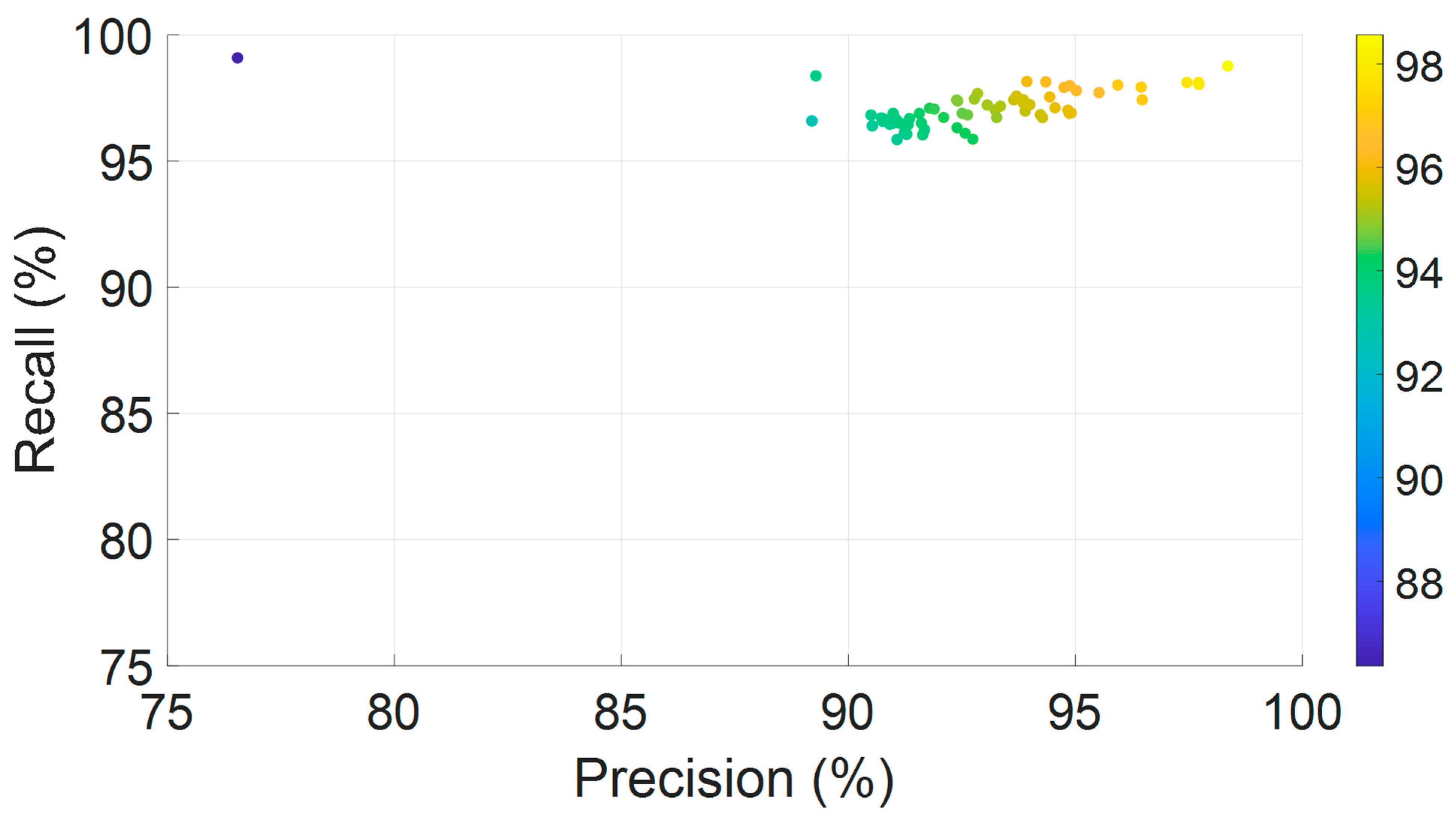

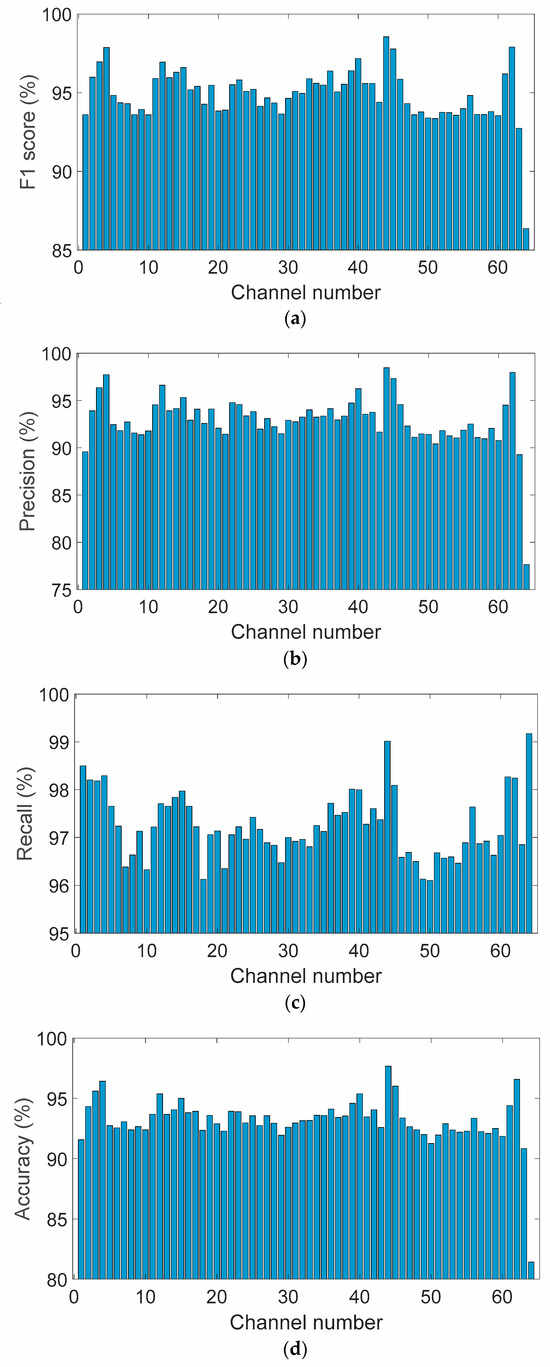

Figure 7 presents a scatter plot depicting the joint distribution of precision and recall values across all 64 EEG channels. Each point represents an individual channel, with color encoding the corresponding F1-score. The majority of data points are concentrated in the upper-right quadrant, indicating high precision and recall levels. This dense clustering reflects the model’s ability to achieve both strong sensitivity and specificity across spatially distributed EEG signals. The color gradient reveals consistently high F1-scores, predominantly exceeding 94%, underscoring the model’s balanced and robust performance in accurately identifying true positive events while limiting false positives across a heterogeneous electrode array.

Figure 7.

Joint distribution of precision and recall across all 64 EEG channels, color-coded by F1-score.

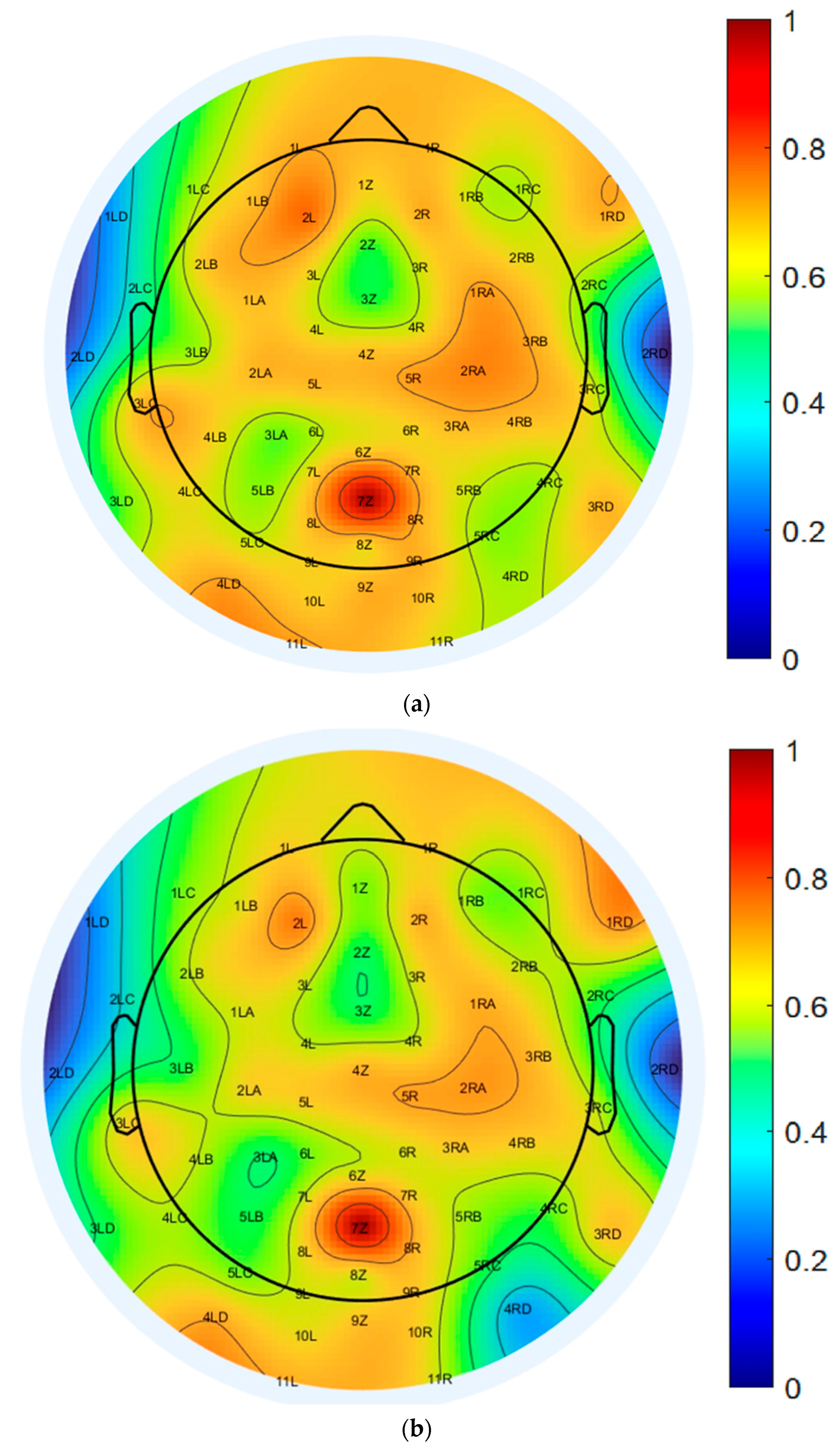

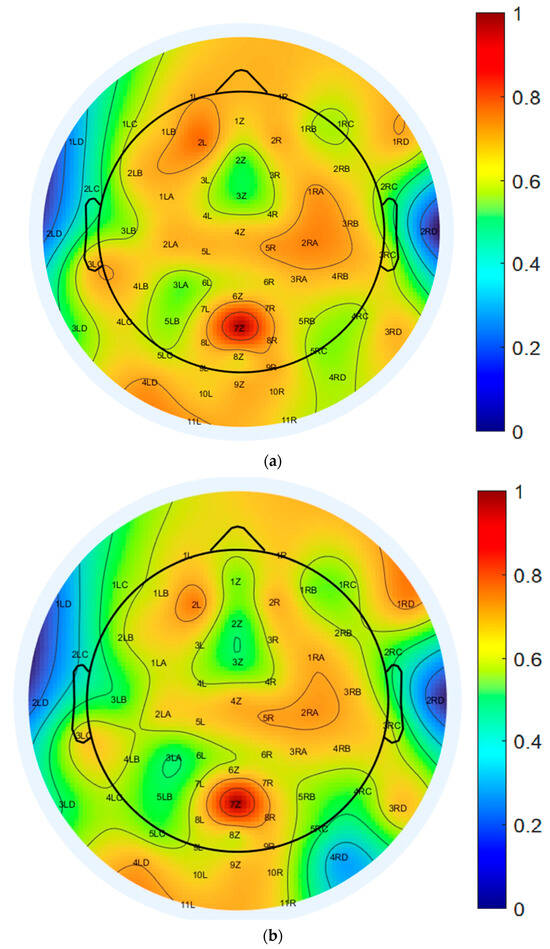

To further assess the spatial characteristics of neural activity, scalp topography maps at 10 Hz were generated using both EEGLAB-based ICA decomposition and the proposed CNN model, as illustrated in Figure 8a,b. Both topographic plots capture the distribution of power within the alpha frequency band and reveal broadly consistent activation patterns, with elevated power localized predominantly over the central scalp regions.

Figure 8.

Topographical distribution of normalized PSD at 10 Hz across all 64 EEG channels: (a) EEGLAB-based ICA decomposition, and (b) CNN-based decomposition.

The color-coded maps represent normalized PSD values, ranging from −77.5 dB to −51.8 dB, offering a detailed spatial quantification of EEG signal strength. The EEGLAB-based ICA map, shown in Figure 8a, displays more pronounced and spatially localized power peaks, particularly over the central and parietal electrodes, suggesting stronger focal sources and greater spatial variability. In contrast, the CNN-based map, shown in Figure 8b, exhibits a smoother and more evenly distributed power profile across the scalp, indicating improved spatial consistency while preserving the core topographic features identified by ICA.

This reduced spatial variability in the CNN-derived map implies a robustness to noise and artifact contamination, reflecting the model’s capacity to generalize across spatial domains without compromising the accuracy of source localization. Collectively, these results support the CNN model’s ability to reconstruct ICA-equivalent spatial activation patterns while enhancing stability and uniformity in scalp-level EEG representations within the 10 Hz alpha band.

Minimal differences were observed between the spatial activation patterns extracted by EEGLAB ICA and those derived from the CNN-based decomposition across the majority of EEG channels. These results indicate that the proposed CNN model effectively captures key spatial features while providing the advantage of significantly faster and fully automated analysis. The most notable deviations were localized in the right parietal and posterior regions, particularly at channels 3RC, 4RC, 3RD, and 4RD. Smaller discrepancies were also observed in channels 4LD, 4LC, 3LC, 7Z, 8Z, and 9Z. These regions are often susceptible to overlapping neural sources, muscle artifacts, or visual processing noise, which may contribute to the observed spatial variation.

In contrast, strong consistency between the two methods was found in frontal and central regions, including channels associated with attention and sensorimotor functions. This spatial agreement supports the CNN model’s capacity to reliably identify relevant neural components across core cognitive regions. Overall, the CNN-based approach maintains the interpretability of traditional ICA while enabling scalable, real-time EEG analysis. These attributes are particularly advantageous for large-scale datasets, BCI systems, and clinical applications where rapid and automated processing is essential.

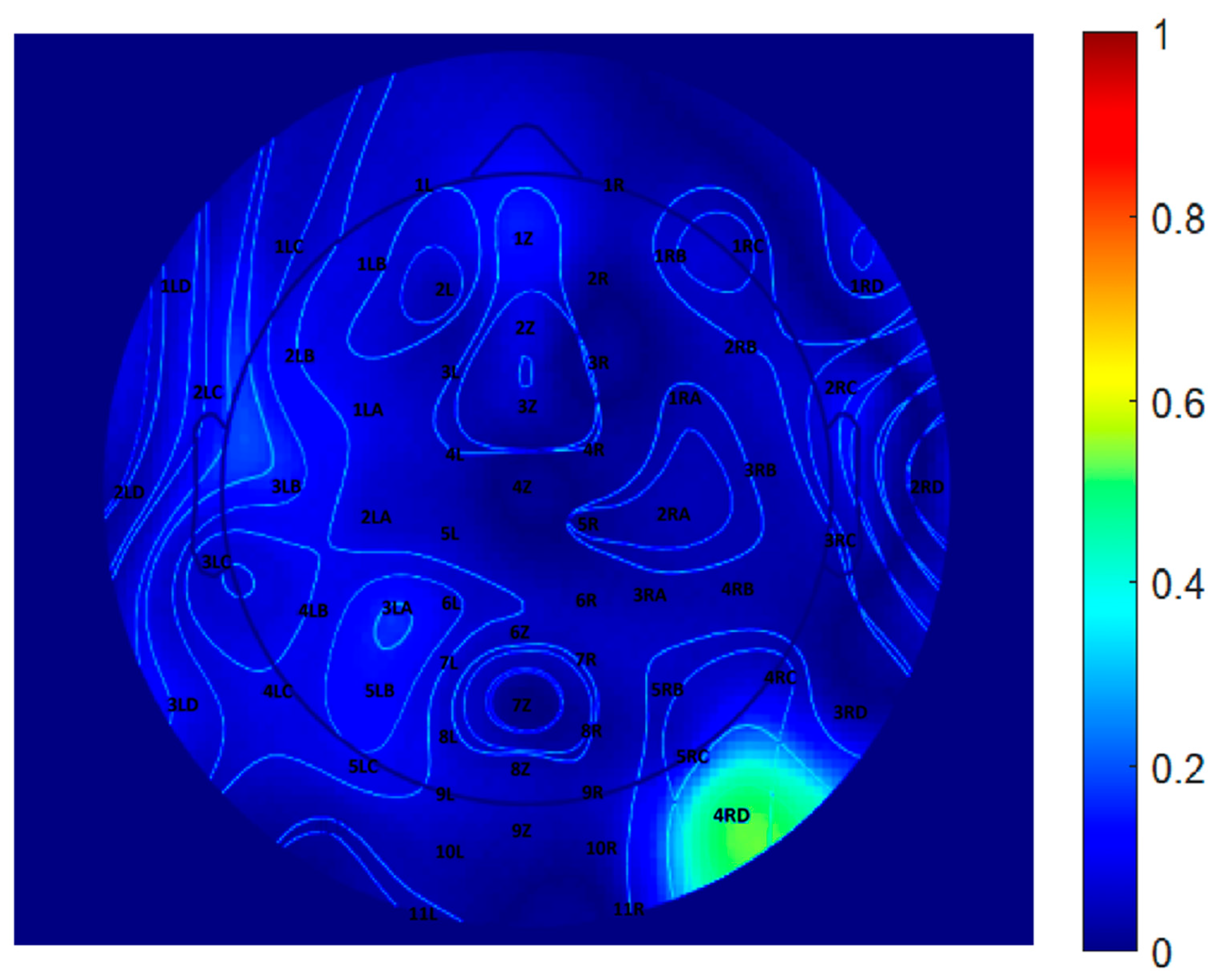

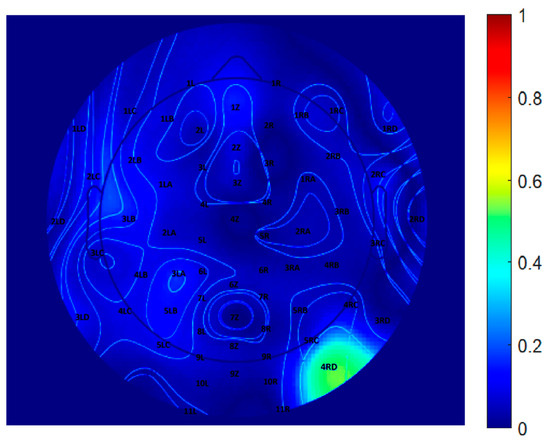

To further quantify the differences between the two decomposition methods, a difference map was generated by computing the pointwise subtraction between the EEGLAB and CNN topographic distributions, as shown in Figure 9. Warmer colors represent regions of greater discrepancy, while cooler colors indicate higher similarity. This visualization highlights specific scalp regions where method-specific differences are pronounced, potentially reflecting variations in component weighting, spatial filtering, or representation strategies inherent to each algorithm. Difference maps such as this are valuable for evaluating spatial agreement across the electrode array and for identifying areas where decomposition methods diverge in their interpretation of EEG source activity.

Figure 9.

Difference map between EEGLAB and CNN-derived topographical distributions at 10 Hz.

5. Discussion

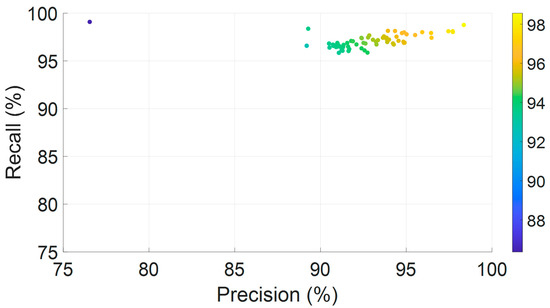

The proposed automated approach significantly accelerates the EEG analysis process compared to traditional manual methods implemented in EEGLAB. To evaluate the computational efficiency of the CNN-based method, a comparative analysis of processing time was conducted against the EEGLAB ICA pipeline. While both approaches involve similar preprocessing steps, they differ markedly in execution speed. The CNN model achieved substantially faster average per-sample processing times, demonstrating a significant improvement in runtime performance relative to ICA. Moreover, the CNN-based system processed EEG data at a considerably higher throughput, highlighting its suitability for large-scale or time-sensitive applications. These time savings not only enhance the feasibility of real-time analysis but also facilitate the exploration of larger datasets within constrained timeframes. To quantify this improvement, a runtime comparison was performed using data from a single subject, with results summarized in Table 2. This benchmark highlights the practical benefits of adopting the CNN-based pipeline for efficient and scalable EEG signal decomposition.

Table 2.

Runtime comparison between the CNN-based inference model and the EEGLAB ICA pipeline for EEG data analysis (n = 1 subject). Total processing time, per-sample average, and standard deviation are reported.

The total runtime for CNN-based inference was substantially shorter than that of the EEGLAB ICA method. The average per-sample processing time for the CNN model was significantly lower, confirming its computational efficiency. Furthermore, the STD of the CNN’s runtime was notably smaller (±0.4567 s) compared to EEGLAB (±93.5716 s), indicating more consistent and stable performance across samples. Overall, the CNN model achieved a speedup factor of 68.36 relative to EEGLAB, underscoring its suitability for real-time and large-scale EEG data processing applications.

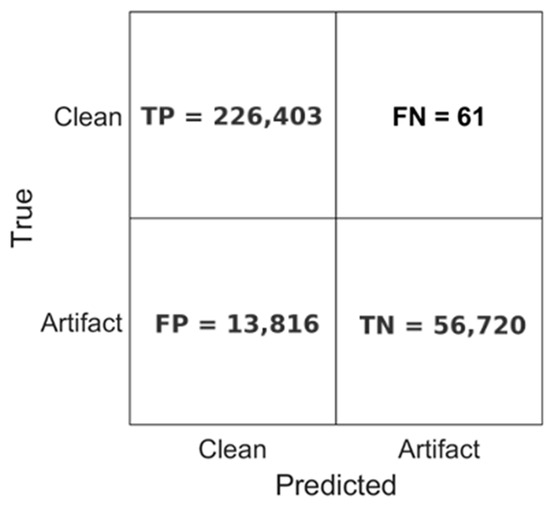

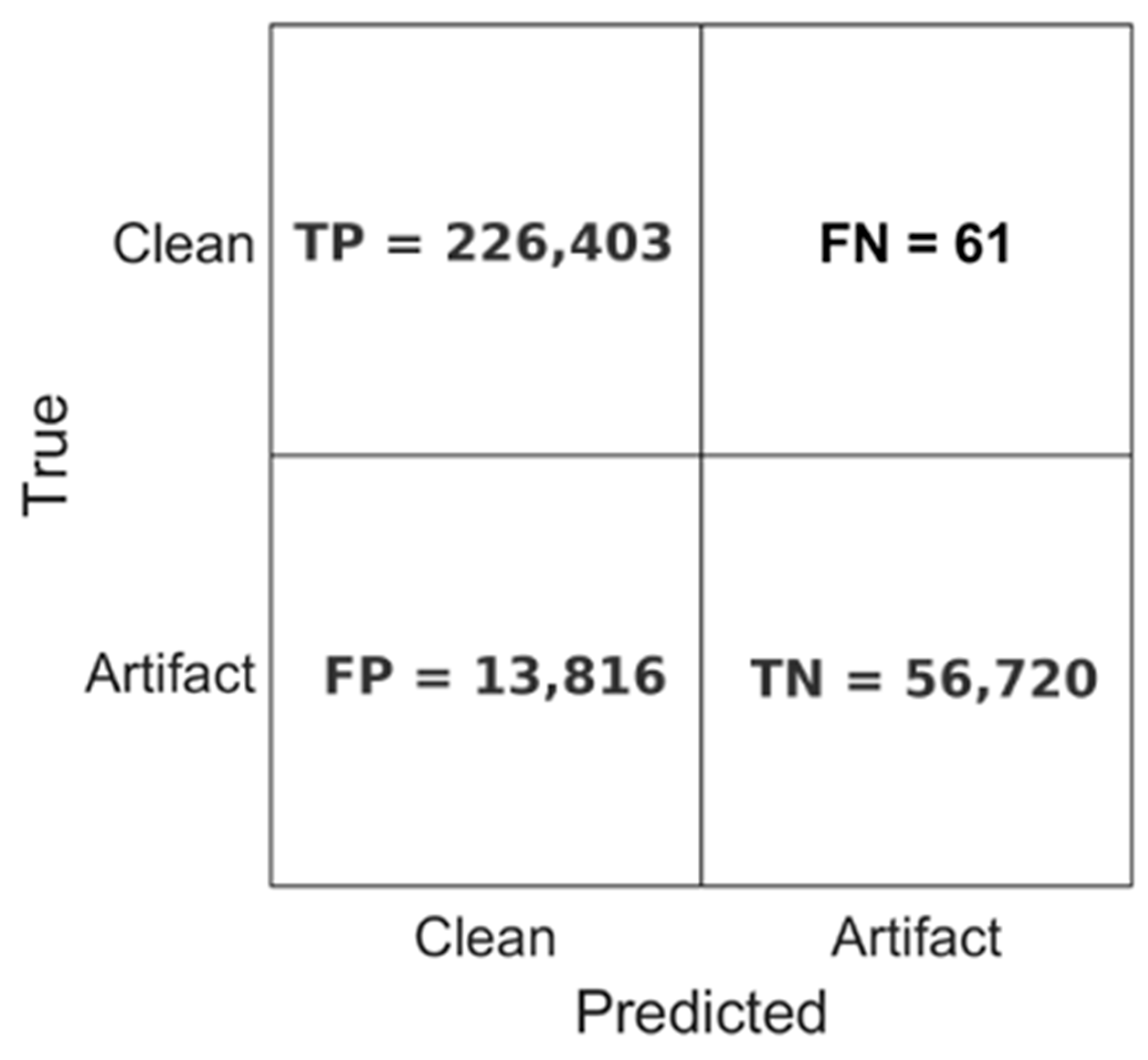

As a pragmatic downstream check, we use the decomposition to perform segment-level clean vs. artifact screening. The classification performance of the model is further illustrated in Figure 10, which presents the confusion matrix obtained during inference. The CNN accurately classified 226,403 EEG segments as clean and correctly identified 56,720 segments as containing artifacts. Misclassifications were minimal, with only 61 clean segments falsely labeled as artifacts (false negatives). However, 13,816 artifact-labeled segments were misclassified as clean (false positives), suggesting a conservative bias toward preserving clean EEG data.

These results demonstrate the model’s strong sensitivity and precision, particularly in preserving valid neural signals, which is a critical requirement for reliable EEG analysis. The combination of high classification accuracy, consistent runtime performance, and rapid processing speed highlights the CNN model’s potential as a robust tool for automated, real-time EEG monitoring and scalable neural data analysis.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrix of the test set.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrix of the test set.

This study presents a machine learning-based framework for EEG signal processing, employing CNNs to replicate and enhance the functionality of ICA. The approach specifically addresses known limitations of ICA, such as its sensitivity to noise, high dimensionality, and inefficiency in real-time processing. Initial preprocessing and ground-truth generation were performed using MATLAB and EEGLAB. Subsequently, the CNN model was trained to process multi-channel EEG recordings and reconstruct ICA-like components with high accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency.

Quantitative similarity metrics confirmed strong agreement between CNN-ICA and EEGLAB-ICA across channels and participants, reinforcing the robustness of our method beyond visual inspection.

The model exhibited consistent and reliable performance across the entire EEG dataset. The CNN achieved a high average F1-score of 94.9% across all channels, with minimal variability. Precision and recall metrics further confirmed the model’s balanced classification performance, maintaining a recall of 97.24% and a precision of 92.9%, thereby indicating its ability to detect true positives while minimizing false positives. Time-domain waveform analyses demonstrated that the CNN accurately reproduced the temporal structure of ICA components across multiple channels and epochs, with F1-score frequently exceeding 90% and reaching up to 98.6% in certain channels. These classification outcomes are not only strong in absolute terms but also meaningful in the context of ICA emulation. Since the functional goal of ICA in EEG preprocessing is to separate neural signals from artifacts, the high F1-score, precision, and recall values confirm that CNN-ICA achieves this separation with fidelity comparable to ICA. In other words, classification metrics serve here as a proxy for decomposition quality, reinforcing the evidence from waveform alignment, PSD spectra, and topographic maps that CNN-ICA preserves relevant neural features while effectively suppressing artifacts.

Spectral analysis showed that the CNN effectively preserved the essential PSD features of the ICA decomposition, while offering improved consistency. Unlike ICA, which exhibited greater variability across channels and frequency bands, the CNN produced tightly clustered and uniform PSD curves, ensuring stable component separation throughout the 8–13 Hz alpha frequency band. Spatial topography comparisons at 10 Hz further validated the CNN’s performance, demonstrating strong alignment with ICA-derived scalp activation patterns. Additionally, the CNN generated smoother and more evenly distributed power maps, as observed in both color and grayscale representations, underscoring the model’s robustness in spatial representation.

A key advantage of the proposed method lies in its computational efficiency. Runtime comparison showed that the CNN-based model processed data approximately 68.38 times faster than the EEGLAB ICA method, reducing the per-subject processing time from 332.73 s to just 4.86 s. Furthermore, the CNN model demonstrated significantly lower variability in execution time, confirming its consistency and reliability. These improvements highlight the model’s applicability in real-time and high-throughput EEG analysis scenarios, making it particularly suitable for large-scale studies, BCIs, and clinical workflows requiring rapid and automated processing.

Beyond EEG signal processing, the method advances core AI goals in algorithmic distillation and efficient inference by replacing an iterative optimization (ICA) with a learned, interpretable surrogate that generalizes across unseen subjects and devices under strict subject-independent evaluation.

Overall, the CNN model reliably reproduces the outputs of ICA while providing substantial enhancements in speed, consistency, and scalability. These advantages position the framework as a valuable and versatile tool for modern EEG research pipelines. It holds strong potential for applications involving real-time cognitive monitoring, longitudinal neurophysiological studies, and integration into clinical decision-support systems that demand efficient and reproducible neural data interpretation.

Despite its promising results, the study has certain limitations. The dataset used in this work was relatively small and homogeneous, consisting of 44 participants recorded during a single educational session and restricted to the alpha frequency band. Future work should focus on validating the model across larger and more diverse populations, exploring additional frequency bands such as beta and gamma, and assessing performance across various cognitive tasks, experimental paradigms, and real-world settings.

Future work could explore multi-modal pipelines that combine EEG with IoT streams, building on evidence from systematic reviews of ML-IoT integration [40].

6. Conclusions

This study introduces a CNN-based framework as a high-performance and scalable alternative to traditional ICA for EEG signal decomposition. The proposed method addresses several limitations of ICA, including its computational inefficiency, reliance on strict statistical assumptions, and limited suitability for real-time or large-scale applications. By leveraging deep learning, the CNN model effectively replicates ICA-derived outputs across temporal waveforms, PSD profiles, and spatial topographies, while reducing computation time by more than 68-fold compared to EEGLAB’s ICA implementation. By combining visual inspection with large-scale quantitative validation, we demonstrated that CNN-ICA reproduces ICA-like decompositions with high fidelity while substantially reducing runtime, making it a practical alternative for real-time and large-scale EEG analysis. Experimental evaluations demonstrated the model’s robustness and generalizability across all 64 EEG channels. The CNN achieved strong performance metrics, including an average F1-score of 94.9%, precision of 92.9%, recall of 97.24%, and accuracy of 93.16%. In addition to replicating spatial activation patterns at 10 Hz with high fidelity, the CNN produced smoother and more stable spectral distributions, contributing to improved interpretability and reliability in both clinical and research settings. Furthermore, confusion matrix analysis confirmed the model’s ability to accurately differentiate clean EEG segments from artifacts, reflecting its utility for automated signal quality control.

The CNN framework’s computational efficiency and classification accuracy make it well suited for real-time EEG applications, including adaptive cognitive monitoring, high-throughput neurophysiological studies, and BCI systems. Its consistent performance and minimal runtime variability are especially advantageous in time-sensitive or large-scale environments.

In summary, unlike prior CNN–EEG studies that focus on classification, the present work introduces a CNN-based surrogate for ICA, trained directly on EEGLAB-derived decompositions. This approach establishes novelty by reframing CNNs for signal-level decomposition, validating fidelity across time, amplitude, and spectral domains, and demonstrating a substantial runtime advantage for real-time applications.

Despite these promising results, the study has certain limitations. The dataset was limited in size and context, consisting of EEG recordings from 44 participants in a structured educational setting, and the analysis focused solely on the alpha frequency band (8–13 Hz). Future research should validate CNN-ICA on larger and more diverse populations, extend decomposition to multiple frequency bands (beta, gamma), and examine performance across a broader range of tasks and naturalistic conditions to better establish generalizability.

In summary, the proposed CNN-based approach represents a significant advancement in EEG signal processing. It offers a fast, reliable, and scalable solution that aligns with the growing demand for automated and interpretable neural data analysis. The framework holds strong potential for integration into next-generation EEG research platforms, real-time neurotechnological systems, and clinical diagnostic tools.

Author Contributions

D.M. conceived the core idea of the study, supervised all phases of the research, and provided detailed guidance throughout, with a particular focus on mentoring. N.A. D.M. also led the decoding strategy and contributed to the integration of the cognitive findings with the interpretation of the neural signals. N.A. led the research and was instrumental in developing the cognitive framework, designing the experiment, and carrying out the data analysis. D.B. and T.G. implemented the decoding pipeline and performed the decoding analyses under the guidance of D.M., and also contributed to data preprocessing and statistical validation. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript. D.M. and N.A. led the revision of the manuscript and the preparation of the response letter to the reviewers. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with the institutional guidelines of the Holon Institute of Technology. Formal approval by an institutional review board was not required for this study, as only anonymized EEG signal data were collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Each participant received a detailed explanation of the experimental procedures and voluntarily agreed to participate by signing a consent form. No personally identifying information or images were recorded. The privacy rights of all subjects were fully protected.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected and analyzed in this study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions and privacy considerations. All relevant analyses derived from the data are presented in the manuscript. The EEG data and participant information are securely stored in accordance with institutional guidelines at the Holon Institute of Technology and are not shared to protect participant confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Malka, D.; Vegerhof, A.; Cohen, E.; Rayhshtat, M.; Libenson, A.; Aviv Shalev, M.; Zalevsky, Z. Improved Diagnostic Process of Multiple Sclerosis Using Automated Detection and Selection Process in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Y.; Banville, H.; Albuquerque, I.; Gramfort, A.; Falk, T.H.; Faubert, J. Deep learning-based EEG analysis: A systematic review. J. Neural. Eng. 2019, 16, 051001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frid, A. Differences in phase synchrony of brain regions between regular and dyslexic readers. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 28th Convention of Electrical & Electronics Engineers in Israel (IEEEI), Eilat, Israel, 3–5 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Alturki, R. An improved deep learning mechanism for EEG recognition in sports health informatics. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 35, 14577–14589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Naranjo, D.; López, E.M.C.; Acuña, A.A.C.; Rodríguez, A.H.F.; Ponce, R.C.; Bravo, J.C.M. Brain-activity based machine learning models predict three-class cognitive performance during multimodal and traditional learning. In World Engineering Education Forum—Global Engineering Deans Council (WEEF-GEDC); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Feyissa, A.M.; Tatum, W.O. Adult EEG. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2019, 160, 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, M.P.; Hosseini, A.; Ahi, K. A review on machine learning for EEG signal processing in bioengineering. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 14, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TaghiBeyglou, B.; Shahbazi, A.; Bagheri, F.; Akbarian, S.; Jahed, M. Detection of ADHD cases using CNN and classical classifiers of raw EEG. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. Update 2022, 2, 100080. [Google Scholar]

- Wójcik, G.M.; Leski, J.M.; Napieralski, A.; Gola, M. Analysis of decision-making process using methods of quantitative electroencephalography and machine learning tools. Front. Neuroinform. 2019, 13, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, H.U.; Malik, A.S.; Ahmad, R.F.; Kamel, N.; Hussain, M. Classification of EEG signals based on pattern recognition approach. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Behroozi, M.; Shalchyan, V.; Daliri, M.R. Classification of epileptic EEG signals by wavelet-based CFC. In Proceedings of the 2018 Electric Electronics, Computer Science, Biomedical Engineerings’ Meeting (EBBT), Istanbul, Turkey, 18–19 April 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Maimaiti, B.; Song, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, M. An overview of EEG-based machine learning methods in seizure prediction and opportunities for neurologists in this field. Neuroscience 2022, 481, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, C.J.; Amlani, M.; Ghosh Hajra, S.; Chaurasia, A.; Ghosh, S. Deep learning of resting-state electroencephalogram signals for three-class classification of Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment and healthy ageing. J. Neural Eng. 2021, 18, 046087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, D.; Sophia, S. GA-CNN: Analyzing student’s cognitive skills with EEG data using a hybrid deep learning approach. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 90, 105888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, O.A.P.; Quijano, Y.; Doniz, M.; Quero, J.E.C. Development of an EEG signal processing program based on, EEGLAB. In Proceedings of the 2011 Pan American Health Care Exchanges, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 28 March–1 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Avital, N.; Nahum, E.; Levi, G.C.; Malka, D. Cognitive state classification using convolutional neural networks on gamma-band EEG signals. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Barstein, J.; Ethridge, L.E.; Mosconi, M.W.; Takarae, Y.; Sweeney, J.A. Resting state EEG abnormalities in autism spectrum disorders. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2013, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lin, J.; Cheng, S.; Chang, C.; Hesse, S.; Miyakoshi, M. ICA’s bug: How ghost ICs emerge from effective rank deficiency caused by EEG electrode interpolation and incorrect re-referencing. Front. Signal Process. 2023, 3, 1064138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munjal, R.; Varshney, T.; Choudhary, A.; Dhiman, R. Convolutional neural network-based models for identification of brain state associated with Isha Shoonya meditation. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computing, Communication, and Intelligent Systems (ICCCIS), Greater Noida, India, 3–4 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Mao, Z.; Huang, Y.F.; Xu, L.; Ding, G. Deep learning models for EEG-based rapid serial visual presentation event classification. J. Inf. Hiding Multimed. Signal Process. 2018, 9, 177–187. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Tian, C.; Rui, C.; Wang, B.; Niu, Y.; Hu, T.; Guo, H.; Xiang, J. Epileptic seizure detection based on EEG signals and CNN. Front. Neuroinformatics 2018, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Ran, X.; Liu, K.; Yao, C.; Yao, Y.; Wu, H.; Liu, Q. Machine learning applications on neuroimaging for diagnosis and prognosis of epilepsy: A review. J. Neurosci. Methods 2022, 368, 109441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, R.; Dass, S.; Malik, A. Electroencephalogram-based decoding cognitive states using convolutional neural network and likelihood ratio-based score fusion. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, T.R.; Kothe, C.A.E.; Chi, Y.M.; Ojeda, A.; Kerth, T.; Makeig, S.; Jung, T.-P.; Cauwenberghs, G. Real-time neuroimaging and cognitive monitoring using wearable dry EEG. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 62, 2553–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieracitano, C.; Mammone, N.; Bramanti, A.; Marino, S.; Hussain, A.; Morabito, F.C. A time-frequency-based machine learning system for brain states classification via EEG signal processing. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Budapest, Hungary, 14–19 July 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, T.; Xu, K.; Zheng, X.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Nie, W. Towards mental load assessment for high-risk works driven by psychophysiological data: Combining a 1D-CNN model with random forest feature selection. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 96, 106615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, M.; DelRosso, L.M.; Elble, R.; Ferri, R.; Horak, F.B.; Lehericy, S.; Shibasaki, H. Evaluation of movement and brain activity. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 132, 2608–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, S.; Sriraam, N.; Temel, Y.; Rao, S.V.; Kubben, P.L. EEG-based multi-class seizure type classification using convolutional neural network and transfer learning. Neural Netw. 2020, 124, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdary, M.K.; Anitha, J.; Hemanth, D.J. Emotion Recognition from EEG Signals Using Recurrent Neural Networks. Electronics 2022, 11, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craik, A.; He, Y.; Contreras-Vidal, J.L. Deep Learning for Electroencephalogram (EEG) Classification Tasks: A Review. J. Neural Eng. 2019, 16, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratić, B.; Kurbalija, V.; Ivanović, M.; Oder, I.; Bosnić, Z. Machine learning for predicting cognitive diseases: Methods, data sources and risk factors. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Phua, K.; Yu, J.; Selvaratnam, T.; Toh, V.; Khan, I.; Wang, J. Image-based motor imagery EEG classification using convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics, Chicago, IL, USA, 19–22 May 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Avital, N.; Shulkin, N.; Malka, D. Automatic calculation of average power in electroencephalography signals for enhanced detection of brain activity and behavioral patterns. Biosensors 2025, 15, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovitch, A.; Baruch, E.B.; Siton, M.; Avital, N.; Yeari, M.; Malka, D. Efficient detection of mind wandering during reading aloud using blinks, pitch frequency, and reading rate. AI 2025, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avital, N.; Egel, I.; Weinstock, I.; Malka, D. Enhancing real-time emotion recognition in classroom environments using convolutional neural networks: A step towards optical neural networks for advanced data processing. Inventions 2024, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajwal, S.; Aggarwal, S. Convolutional neural network-based EEG signal analysis: A systematic review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 30, 3585–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, U.R.; Oh, S.L.; Hagiwara, Y.; Tan, J.H.; Adeli, H. Deep convolutional neural network for the automated detection and diagnosis of seizure Using EEG Signals. Comput. Biomed. 2018, 101, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Li, F. Deep convolutional neural network-based epileptic electroencephalogram (EEG) signal classification. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foody, G. Challenges in the real-world use of classification accuracy metrics: From recall and precision to the Matthews correlation coefficient. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahal, A.; Addula, S.R.; Jain, A.; Gulia, P.; Gill, N.S.; Dhandayuthapani, V.B. Systematic analysis based on conflux of machine learning and Internet of Things using bibliometric analysis. J. Intell. Syst. Internet Things 2024, 13, 196–224. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).