1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infection can lead to gastritis, peptic ulcer, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, and is a well-established risk factor for gastric adenocarcinoma [

1]. Given that

H. pylori contributed to approximately 4.8% of global cancer incidence in 2018 (excluding non-melanoma skin cancers), controlling this infection is a public health priority. Early detection and eradication of

H. pylori have been shown to reduce the incidence of gastric cancer [

2]. The success of eradication programs partly depends on public awareness and engagement. Unfortunately, knowledge of

H. pylori in the general population is often poor, and individuals with low awareness are less likely to undergo testing or adhere to treatment. This gap highlights the importance of effective patient education in improving disease outcomes [

3].

Patient education initiatives for

H. pylori aim to clearly and understandably convey information on transmission, risks, testing, and treatment to encourage informed decision-making and adherence [

4]. Traditional patient education materials (pamphlets, websites) require significant efforts by experts to create content that is accurate, comprehensive, and pitched at the right literacy level [

5]. In recent years, advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have led to the development of new tools for generating health information. Large language models (LLMs) like OpenAI’s ChatGPT can produce human-like text and have been explored in various medical applications (e.g., drafting medical notes and assisting clinical decision support) [

6]. In gastroenterology, there is growing interest in using LLMs to address patient questions and provide guidance on conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and

H. pylori infection. LLMs offer the potential for an on-demand, scalable approach to disseminate health information, but their reliability and quality must be rigorously evaluated before clinical integration [

7].

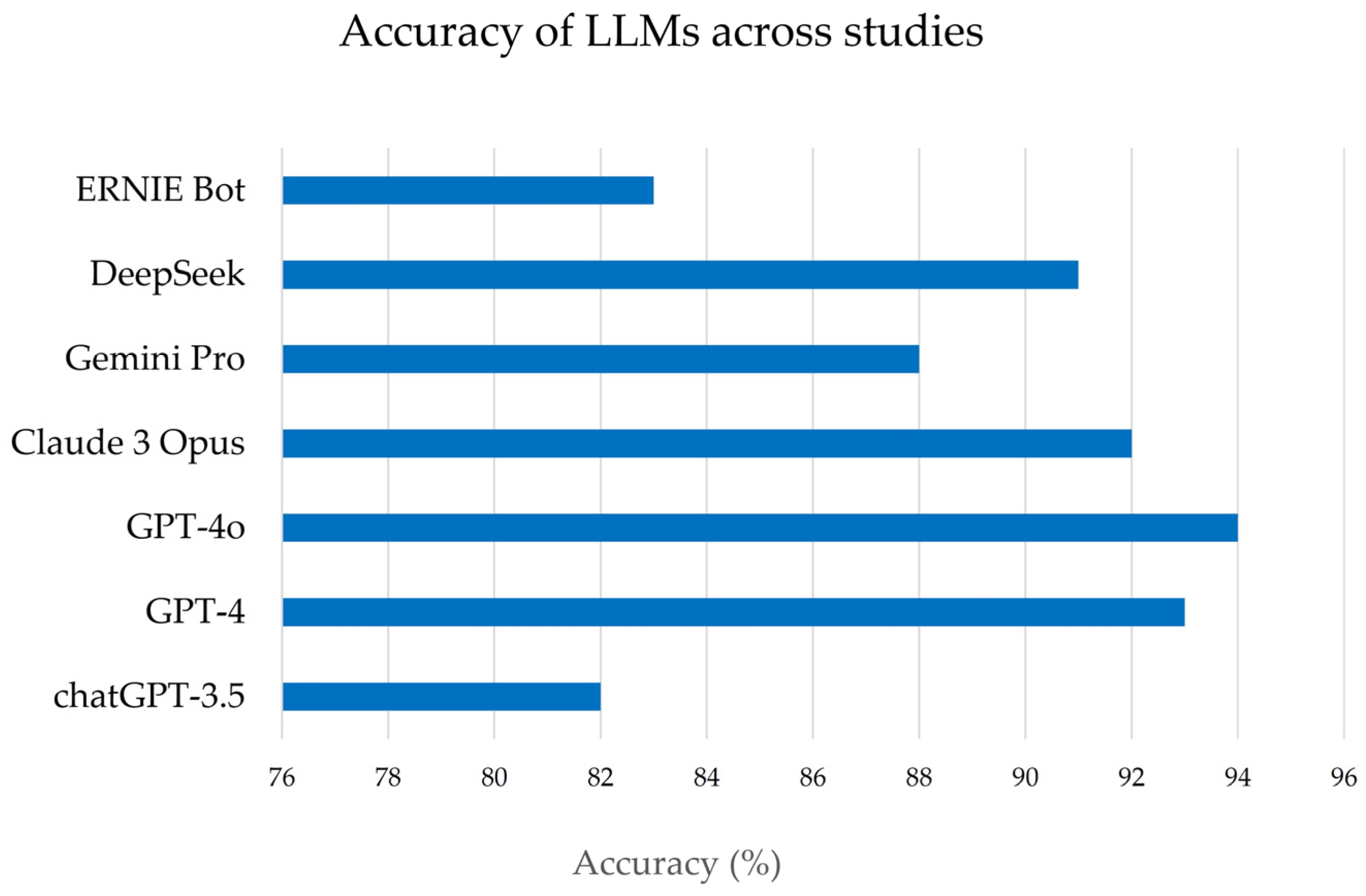

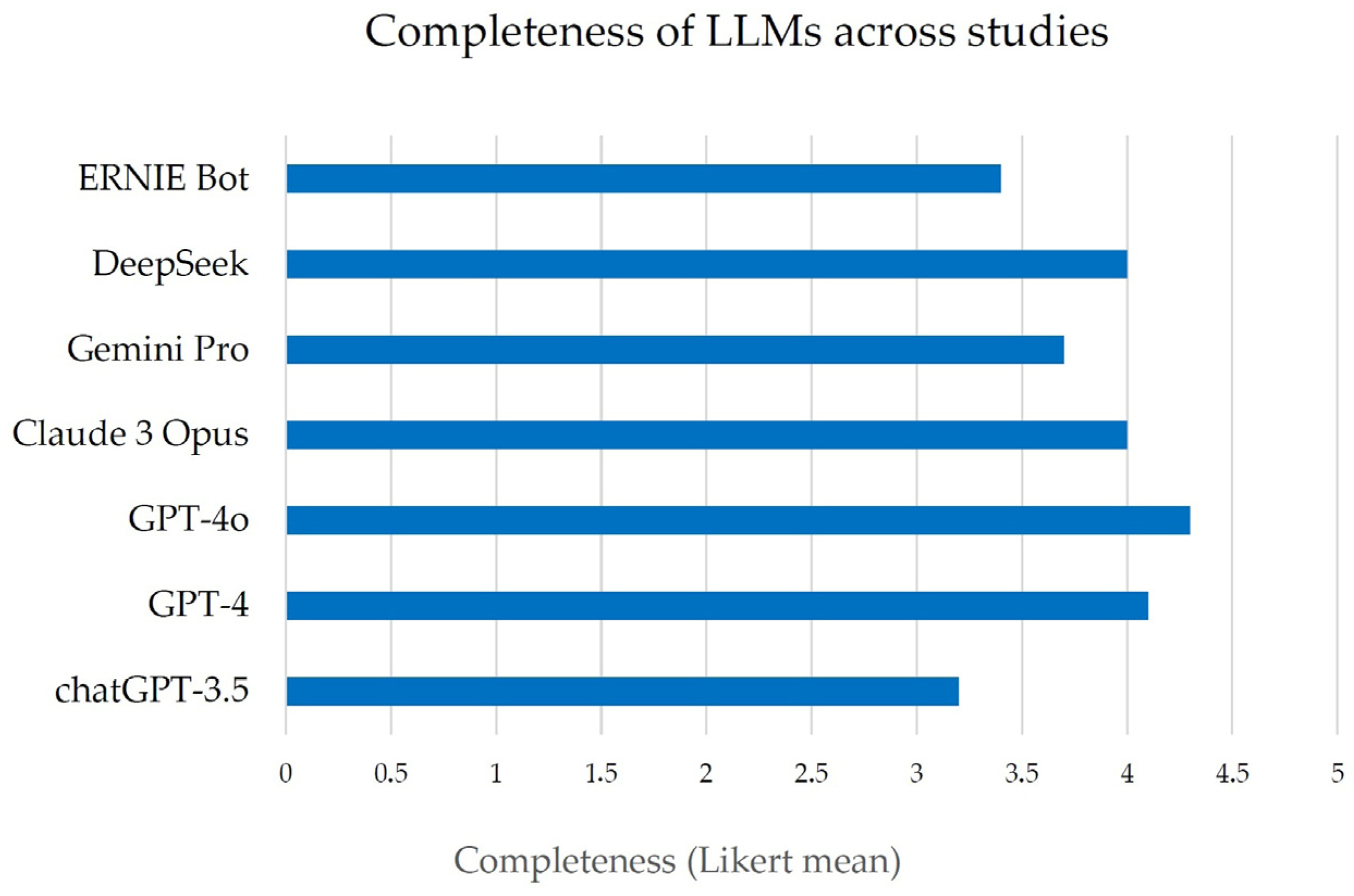

Early studies evaluated LLM-generated information on H. pylori. They examined content quality on multiple fronts, including factual accuracy, completeness of information, readability for the average patient, and safety (absence of misleading or harmful advice). They also gauge how well patients understand the AI-provided information and how satisfied users are with the answers, compared to traditional expert-derived content.

Importantly, successive editions of ChatGPT (e.g., GPT-3.5, GPT-4, GPT-4o) and other LLMs differ in training data, architecture, and alignment procedures, which can materially influence the accuracy, completeness, and style of their responses. Evaluating individual model versions, rather than treating “ChatGPT” as a single entity, is therefore essential for a nuanced understanding of performance.

Several recent narrative and umbrella reviews have examined the broader use of LLMs in healthcare, including gastroenterology research and clinical practice [

6,

7]. However, to our knowledge, no prior review has focused explicitly on LLM-generated patient-educational materials for

H. pylori infection. Given the high prevalence of

H. pylori, its established role in gastric carcinogenesis, and the availability of multiple empirical studies directly comparing LLM-generated and gastroenterologist-written materials in this domain,

H. pylori provides a timely and clinically relevant case study to explore the opportunities and limitations of AI-based patient education.

In this context, “educational materials” in the present article are defined as written or text-based resources intended primarily for patients or laypersons, rather than for the education of medical students, residents, or other healthcare professionals.

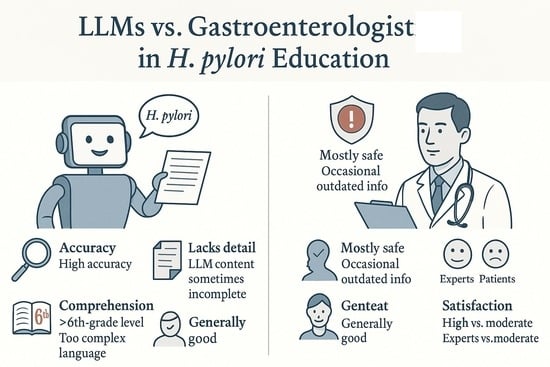

This review provides a summary analysis of LLM-generated H. pylori educational content in comparison with content written by gastroenterologists. We focus on six key quality domains: (i) accuracy (correctness of information); (ii) completeness (breadth and depth of content); (iii) readability (reading level and ease of understanding); (iv) patient comprehension (how well target audiences understand the material); (v) safety (freedom from harmful or misleading information); and (vi) user satisfaction. By synthesizing results from recent studies, we aim to determine whether LLMs can serve as reliable patient education tools in H. pylori infection and identify any necessary improvements or safeguards to enhance their usefulness in clinical practice.

The present article is conceived as a narrative, non-systematic review, providing an integrative synthesis of a rapidly emerging evidence base rather than a systematic meta-analysis.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Scope

The primary objective was to synthesize recent evidence on the quality of LLM-generated educational materials on H. pylori infection, compared with content produced by human gastroenterology experts. Our focus was explicitly on patient-facing information rather than on educational resources for medical trainees. Given the limited number of available studies and their methodological heterogeneity, the review does not follow the PRISMA guidelines and does not conduct a formal meta-analysis. Instead, we provide a structured qualitative synthesis complemented by descriptive summaries.

2.2. Search Strategy

We searched PubMed/MEDLINE and Google Scholar for English-language, peer-reviewed publications from January 2023 to January 2025. The following keyword combinations were used: (“Helicobacter pylori” OR “H. pylori”) AND (“large language model” OR “LLM” OR “ChatGPT” OR “artificial intelligence”) AND (“patient education” OR “educational materials” OR “information” OR “counseling”). The reference lists of relevant articles were also manually screened to identify additional studies.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (i) empirical research articles or letters reporting original data; (ii) evaluation of at least one LLM (e.g., ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, ChatGPT-4o, Gemini, ERNIE Bot, DeepSeek) in answering H. pylori-related questions or generating H. pylori educational materials; (iii) comparison of LLM-generated content with information provided by clinicians (e.g., gastroenterologists) or established references; and (iv) assessment of at least one of the six predefined domains: accuracy, completeness, readability, comprehension, safety, or user satisfaction.

Exclusion criteria were: non-empirical articles (e.g., commentaries, editorials without original data), conference abstracts without complete data, technical AI papers without patient-facing content, and studies not specific to H. pylori.

Two authors (G.O., M.P.D.) independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance, followed by full-text assessment of potentially eligible articles. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion among the authors. The final selection comprised seven studies (six original research articles and one letter), which are summarized in

Table 1. Because of differences in study design, outcome definitions, scoring scales, and prompting strategies, a formal PRISMA flow diagram and meta-analytic pooling were not undertaken.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

For each included study, we extracted information on: study design; LLMs and versions evaluated; comparators; type of raters or respondents (e.g., board-certified gastroenterologists, trainees, patients, laypersons); language(s); and outcomes related to accuracy, completeness, readability, comprehension, safety, and user satisfaction. Particular attention was paid to the prompts used to query the LLMs (e.g., instructions regarding reading level or language), as these may influence performance. Given the heterogeneity of metrics (e.g., different Likert scales, percentages of correct answers, various readability indices), results were synthesized qualitatively (

Table 1).

These studies collectively examined multiple LLM platforms (including various versions of OpenAI’s ChatGPT, such as GPT-3.5, GPT-4, GPT-4.5, GPT4o, and other models like ERNIE Bot and DeepSeek, Gemini, etc.). They often included multiple languages (typically English and Chinese). For each study, we extracted data pertaining to the six predefined domains of interest: accuracy, completeness, readability, patient comprehension, safety, and user satisfaction (for both patients and providers). Due to heterogeneity in study designs and measurement scales, a meta-analytic quantitative synthesis was not feasible; instead, results were integrated qualitatively. Key findings from each domain were compared and summarized, emphasizing consistent patterns or notable discrepancies between LLM- and expert-generated content. We ensured that the source data from these studies supported any interpretative claims. All data presented are reported as originally stated in the studies, with representative examples and statistical results cited to illustrate each point. No additional experimental data were generated for this review.

4. Discussion

This comparative analysis suggests that LLMs have significant potential to complement gastroenterologists in providing patient education about

H. pylori infection; however, critical challenges must be addressed before LLM-generated content can be adopted in practice. Accuracy emerged as a clear strength of modern LLMs. The reviewed studies uniformly show that these models can deliver factually correct answers to

H. pylori questions at a level comparable to clinicians. This high accuracy is consistent with reports that most of the AIs under study have passed medical exams, suggesting that, on average, patients querying an advanced LLM are likely to receive generally reliable information. Such a capability could be invaluable in settings where physicians are not readily available to answer every question. For instance, patients often have numerous concerns about

H. pylori (ranging from transmission to diet to treatment side effects) that they may not fully address during a brief clinic visit. An LLM-based tool could provide immediate, accurate answers as a supplement to the physician’s advice, potentially improving patient understanding and reducing anxiety. However, accuracy alone is not sufficient. The completeness of information is where LLM responses currently fall short in comparison to a thorough consultation or a well-crafted pamphlet by an expert. In practice, an incomplete answer can be as problematic as an incorrect one when critical guidance is omitted. The observation that LLMs frequently provide only partial answers (e.g., lacking detail on follow-up testing or omitting certain risk factors) underscores the risk that patients using these tools might encounter knowledge gaps. A patient might recognize that

H. pylori causes ulcers and can be treated with antibiotics (information that an LLM is likely to provide), but not realize that family members should also be tested, or that antibiotic resistance could affect therapy, nuances that an expert would emphasize [

13]. One strategy to improve completeness is better prompting: clinicians or developers could design structured prompts that ensure all key topics are covered. Another approach is an interactive Q&A, where the AI can prompt the user to learn about related issues (for example, “Would you like to hear about how to prevent reinfection?”). Until such solutions are implemented, it may be advisable for any AI-derived content to undergo review by a healthcare provider to identify and address any issues before the material is provided to patients [

9].

Regarding readability and comprehension, our review underscores that current AI-generated content is not yet optimized for all patient populations. The fact that none of the evaluated materials met the target reading level for 6th graders is a call to action for both AI technology and health communication practices. Even the gastroenterologist-written materials were linguistically too advanced, a known challenge in patient education; explaining medical concepts in elementary language is difficult [

11]. LLMs, with proper training or constraints, might be able to simplify language more consistently than busy clinicians. Future LLM development could focus on a “patient-friendly mode” that prioritizes shorter sentences, familiar words, and clear definitions of medical terms. Additionally, the multilingual capabilities of LLMs are a considerable asset: these models can instantly produce content in multiple languages, a task that would require significant human resources and time. This can help bridge language barriers and reach patient groups who speak different languages. Ensuring readability in each language (not just direct translation) is essential [

9,

11]. Our findings on patient comprehension, especially the gap between experts and laypeople in perceiving clarity, suggest that involving actual patients in the development and testing of LLM-based tools is vital. By observing where non-experts get confused, developers can tweak the AI’s explanations. The AI might also incorporate visual aids and analogies to enhance understanding.

In terms of safety, although most LLMs generally adhered to clinical guidelines, some studies did report a certain level of “harmful” responses. This was primarily due to outdated or incomplete information, such as treatment recommendations that are no longer considered adequate (for example, using an antibiotic regimen that has become ineffective), which can lead to treatment failure. Nonetheless, in several studies, ChatGPT consistently included a recommendation to consult a physician alongside to the information provided, which may help mitigate potential risks. Thus, minimizing the dissemination of outdated or partial content remains crucial [

8,

10,

13]. One solution is to continually update LLM knowledge bases with current clinical guidelines, although models like GPT-4 are not easily updatable in real time [

13]. Future systems may incorporate live data or retrieve information from trusted databases. Another safety measure is transparency: if the AI provides citations or sources (as some LLM-based medical assistants are starting to do), patients and providers can verify the information against reputable references. Ultimately, we envision that LLM-generated patient education will not operate in isolation but rather under a framework of human-AI collaboration: clinicians could supervise the content, or the AI could triage questions and draft answers that a clinician then reviews for accuracy and safety. Such a model would harness the efficiency of AI while prioritizing patient well-being.

User satisfaction and engagement are essential for the practical success of any patient-facing tool. Early positive feedback from physicians and trainees suggests that, if the content is of high quality, healthcare professionals are willing to trust and even recommend these AI resources. This is important, as doctors could serve as facilitators. A doctor might guide a patient to use a vetted chatbot for follow-up questions at home. However, lukewarm responses from some lay users indicate a need to improve the user experience. Patients will be satisfied not just with correct answers, but with the feeling that their concerns were addressed [

9]. LLMs can adopt a conversational style that can be friendly and empathetic, but they currently lack the true personalization and emotional intelligence of a human provider. Future development could incorporate more adaptive responses, in which the AI asks the user whether the answer was helpful or if they have other concerns, thereby mimicking dialog with a doctor. Moreover, some patients might distrust information from an “algorithm.” Building trust will require showing that the AI’s information is endorsed or co-developed by medical experts and that it has been tested in real patient populations with good outcomes. Over time, as patients become more accustomed to digital health tools, their satisfaction is likely to increase, provided the information is reliable and comprehensible. An often-mentioned benefit is the 24/7 availability of LLM-based assistance; patients can get answers at any time, which could improve satisfaction in the context of anxiety (e.g., a patient worrying at night about their

H. pylori test results might consult the AI for immediate information on what to expect).

Despite ongoing technological advances, the core evaluation domains: accuracy, completeness, readability, comprehension, safety, and user satisfaction, remain essential benchmarks. Methodologically, a recurrent limitation across studies is the predominant use of Likert-type scales to assess accuracy, completeness, and comprehensibility. Although convenient, these instruments are inherently subjective; variation in rater interpretation, ceiling effects, and inconsistent scale formats undermine comparability across studies. Moreover, several investigations did not specify whether raters were blinded to the source of the material (LLM vs. clinician) or report inter-rater reliability. Small sample sizes, single-center designs, and limited information on the representativeness of patient cohorts further restrict generalizability. Collectively, these limitations highlight the need for more rigorous, blinded, and standardized evaluation protocols.

Additional heterogeneity stems from prompt design. Some studies used detailed instructions regarding reading level, content scope, or language, whereas others relied on broad, open-ended queries. Because prompts can substantially shape LLM outputs, affecting factual content, length, structure, and clarity, comparisons between models tested with different prompts must be interpreted cautiously. Future research should fully report and, ideally, standardize prompts to isolate model-specific differences better.

Similar concerns have been raised in other specialties, for example, in dermatology, where AI-generated case-based questions lacked depth and educational nuance compared with expert-written material, highlighting the importance of careful oversight when generating any form of educational content [

15].

Finally, although existing studies assessed informational quality and user perceptions, none evaluated downstream clinical outcomes such as treatment adherence, completion of eradication regimens, follow-up testing, or long-term rates of peptic ulcer recurrence and H. pylori-associated gastric cancer. While more accurate and comprehensible educational materials may, in theory, improve adherence and clinical outcomes, these benefits remain largely speculative. Prospective, real-world studies are required to determine whether appropriately supervised, workflow-integrated LLM-based educational interventions yield measurable improvements in patient knowledge, decision-making, adherence, and health outcomes.

5. Conclusions

In this narrative review, we synthesized evidence from 7 recent studies evaluating LLM-generated educational materials for H. pylori infection compared with content produced by gastroenterology experts. Overall, contemporary LLMs demonstrated high accuracy, often approaching that of practicing specialists, and generally acceptable patient comprehensibility, indicating that these tools can effectively address many common patient questions. By generating standardized, evidence-based information across languages and regions, LLMs have the potential to markedly expand access to reliable educational resources.

Nevertheless, important limitations persist. LLM-generated responses were frequently judged to be only partially complete, written above recommended patient reading levels, and occasionally inconsistent with guideline-based management, particularly regarding treatment. Such issues were exacerbated by methodological heterogeneity across studies, including small sample sizes, subjective Likert-scale ratings, variable prompting strategies, and insufficient blinding of evaluators. These factors temper the overall strength of the available evidence.

Taken together, current data suggest that LLMs may serve as valuable adjuncts to traditional gastroenterology care [

16], empowering patients with greater knowledge, reinforcing physicians’ counseling, and potentially improving management of

H. pylori infection. However, fully realizing this promise will require deliberate attention to completeness, readability, safety, and continuous expert oversight to maintain alignment with evolving clinical guidelines.

Looking forward, high-quality prospective studies are essential to determine whether LLM-based patient education leads to measurable clinical benefits, such as improved knowledge retention, reduced decisional conflict, enhanced treatment adherence, and better real-world outcomes. Establishing these effects will be crucial for defining the clinical role of this rapidly advancing technology.