“In Metaverse Cryptocurrencies We (Dis)Trust?”: Mediators and Moderators of Blockchain-Enabled Non-Fungible Token (NFT) Adoption in AI-Powered Metaverses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Foundations, Theoretical Underpinning, and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Blockchain Technologies and Cryptocurrencies in Metaverses

2.2. AI-Powered Virtual Influencers in Metaverses

2.3. Cryptocurrency-Based Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) in Metaverses

3. Research Models and Methodology

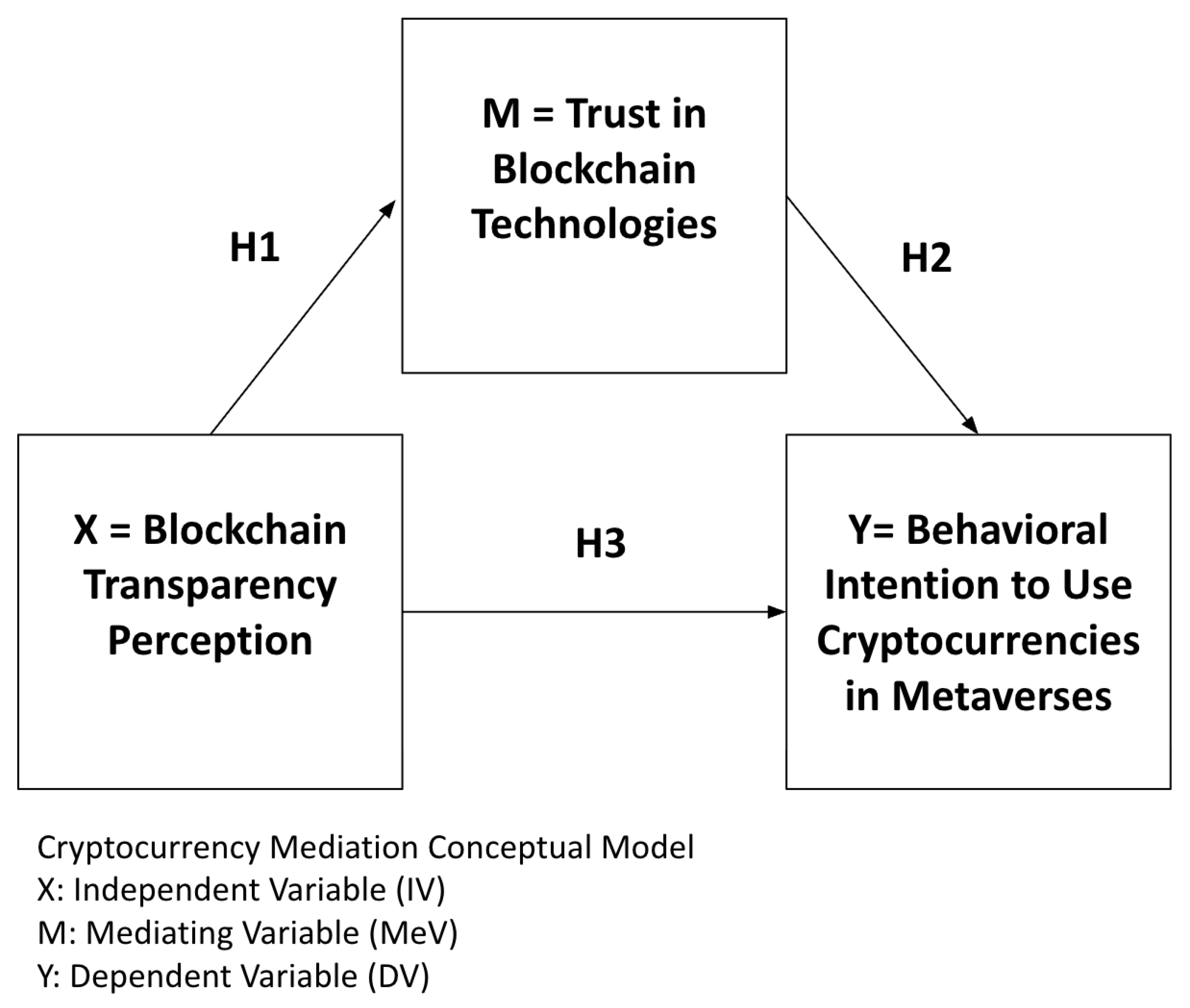

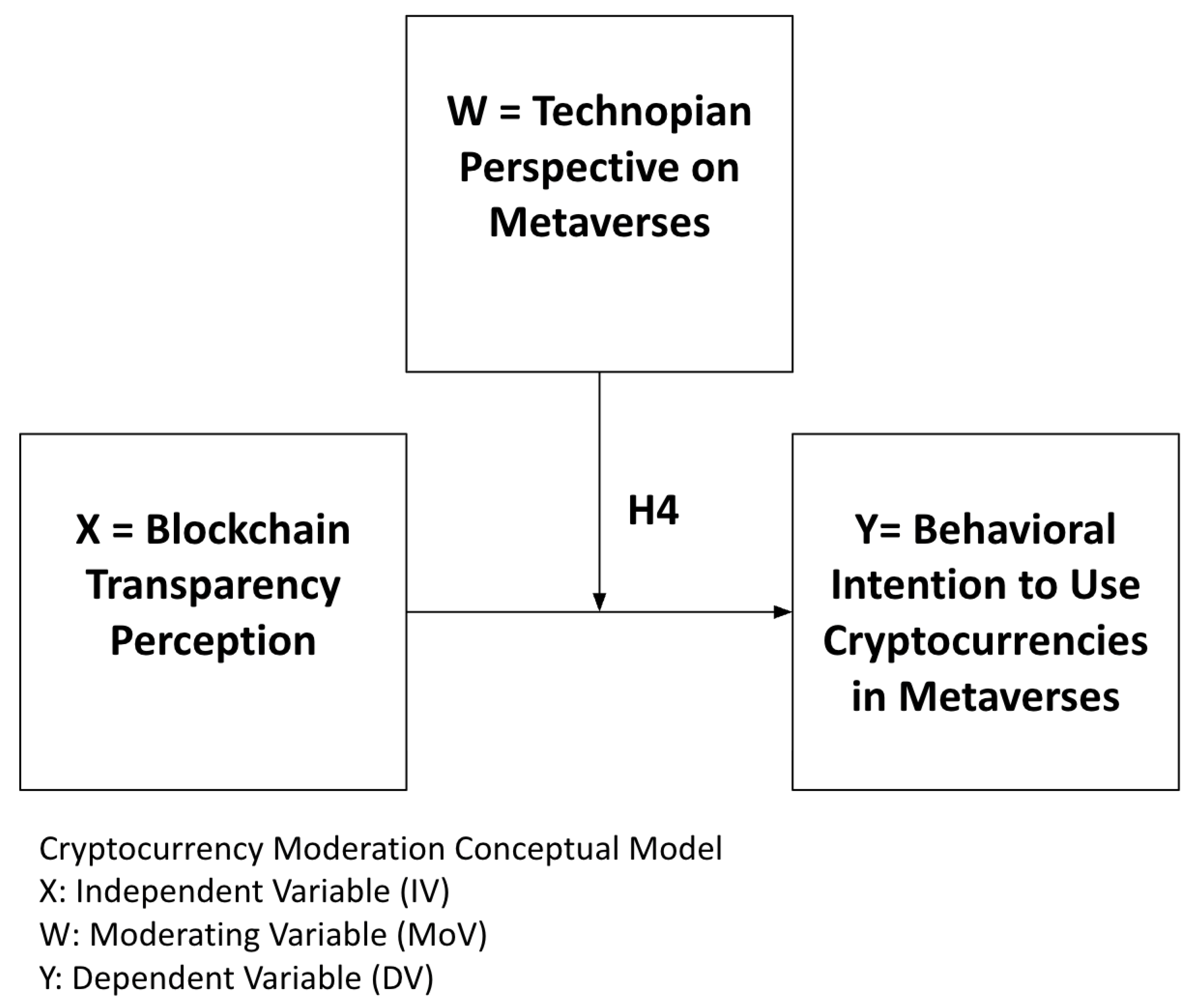

3.1. Study 1 Theoretical Models and Methodology

3.1.1. Study 1 Respondents and Data Collection

3.1.2. Study 1 Measures

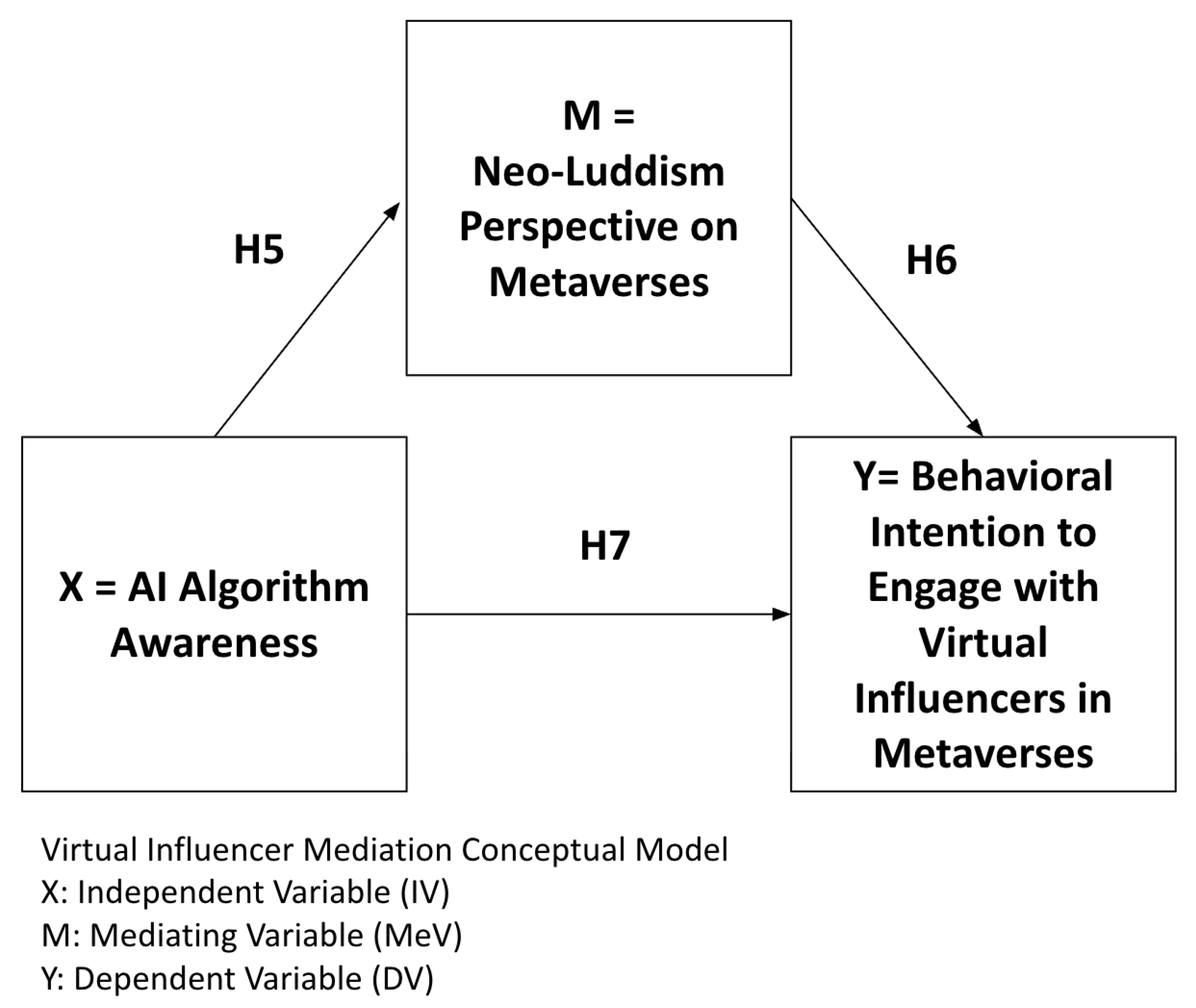

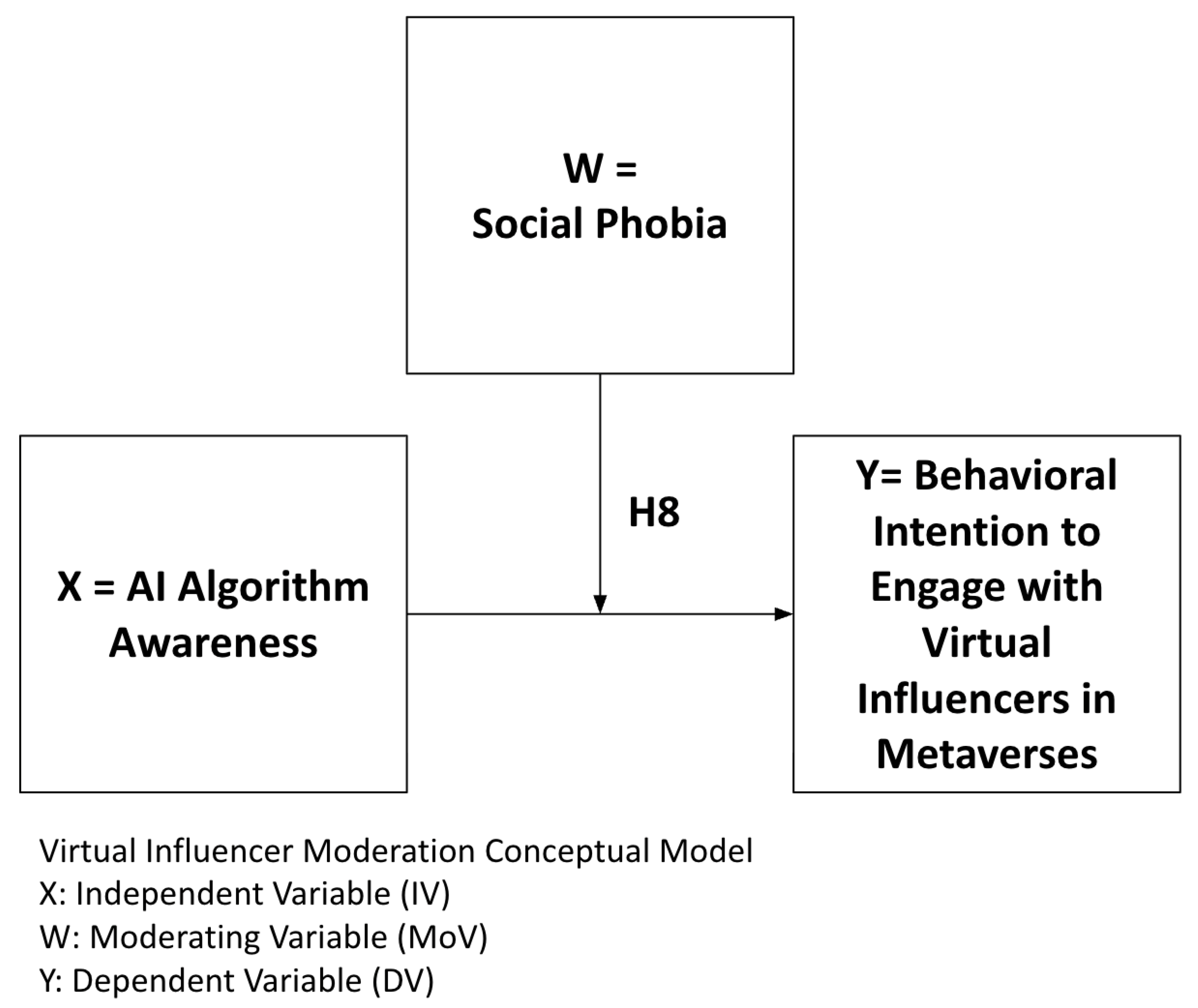

3.2. Study 2 Theoretical Model and Methodology

3.2.1. Study 2 Respondents and Data Collection

3.2.2. Study 2 Measures

4. Results

4.1. Study 1 Results

4.1.1. Study 1 Descriptive Statistics

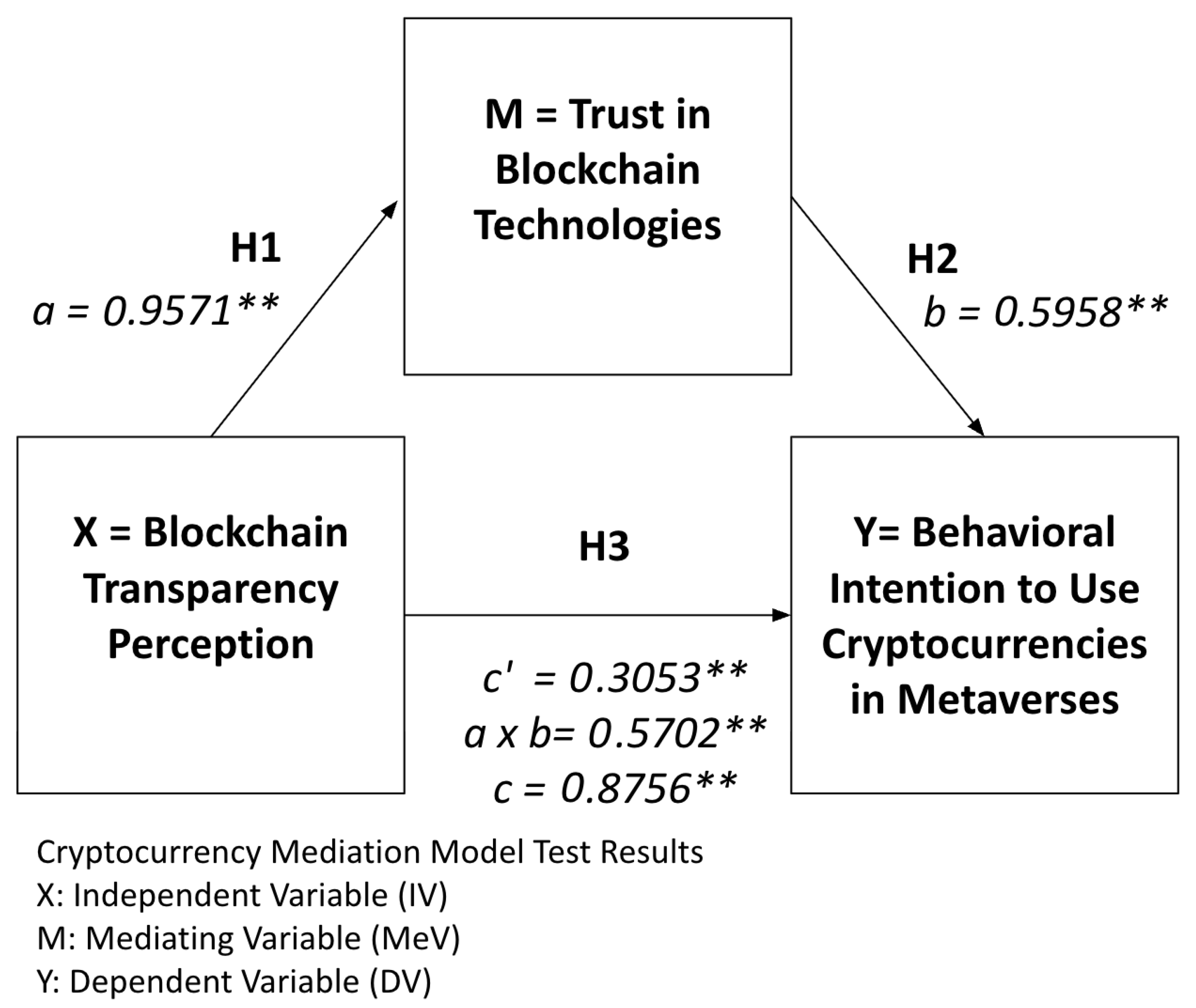

4.1.2. Mediation Effect of Trust in Blockchain Technologies

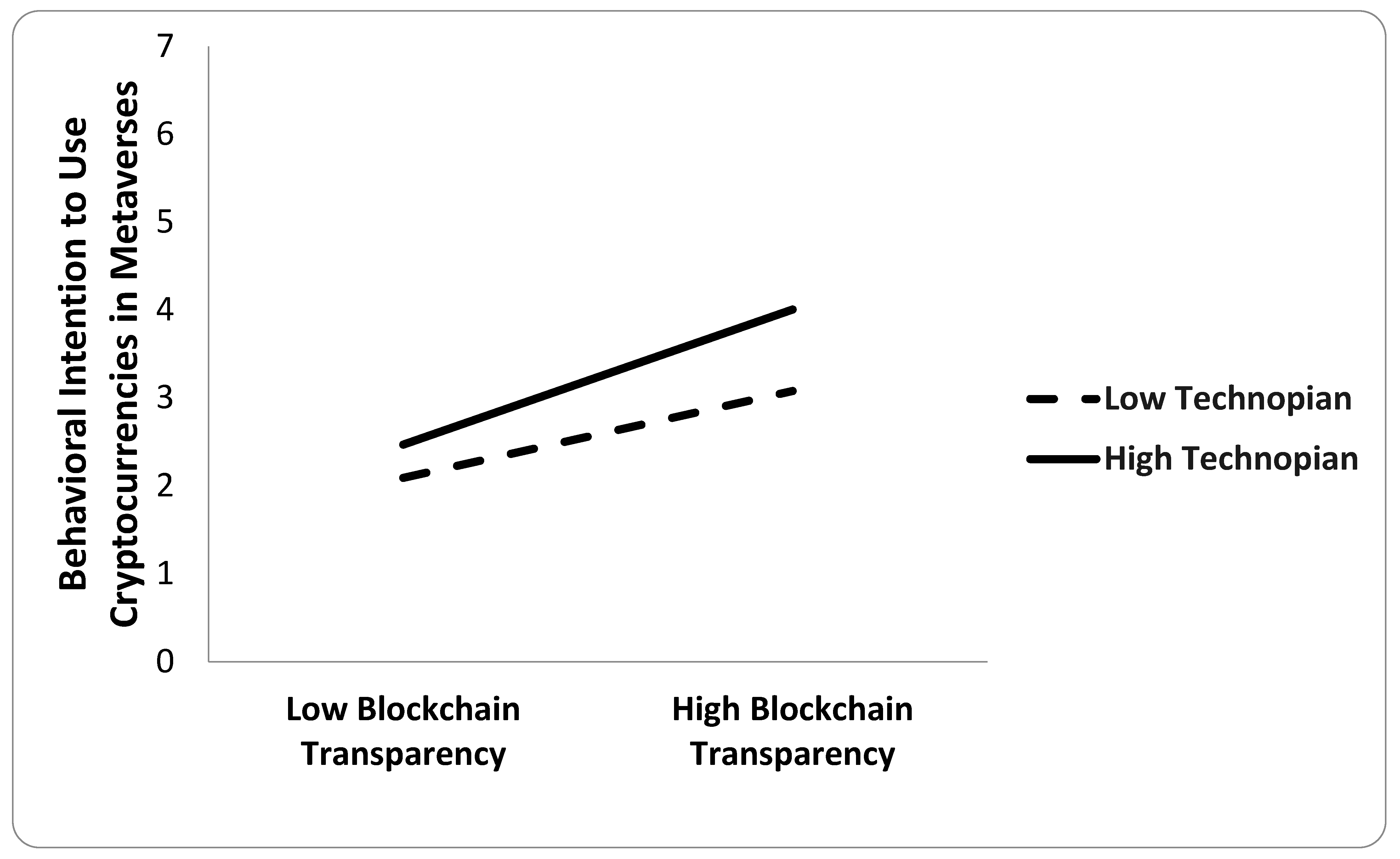

4.1.3. Moderation Effect of Technopian Perspectives Regarding Metaverses

4.1.4. Mediation Effect of Neo-Luddism Regarding Metaverses

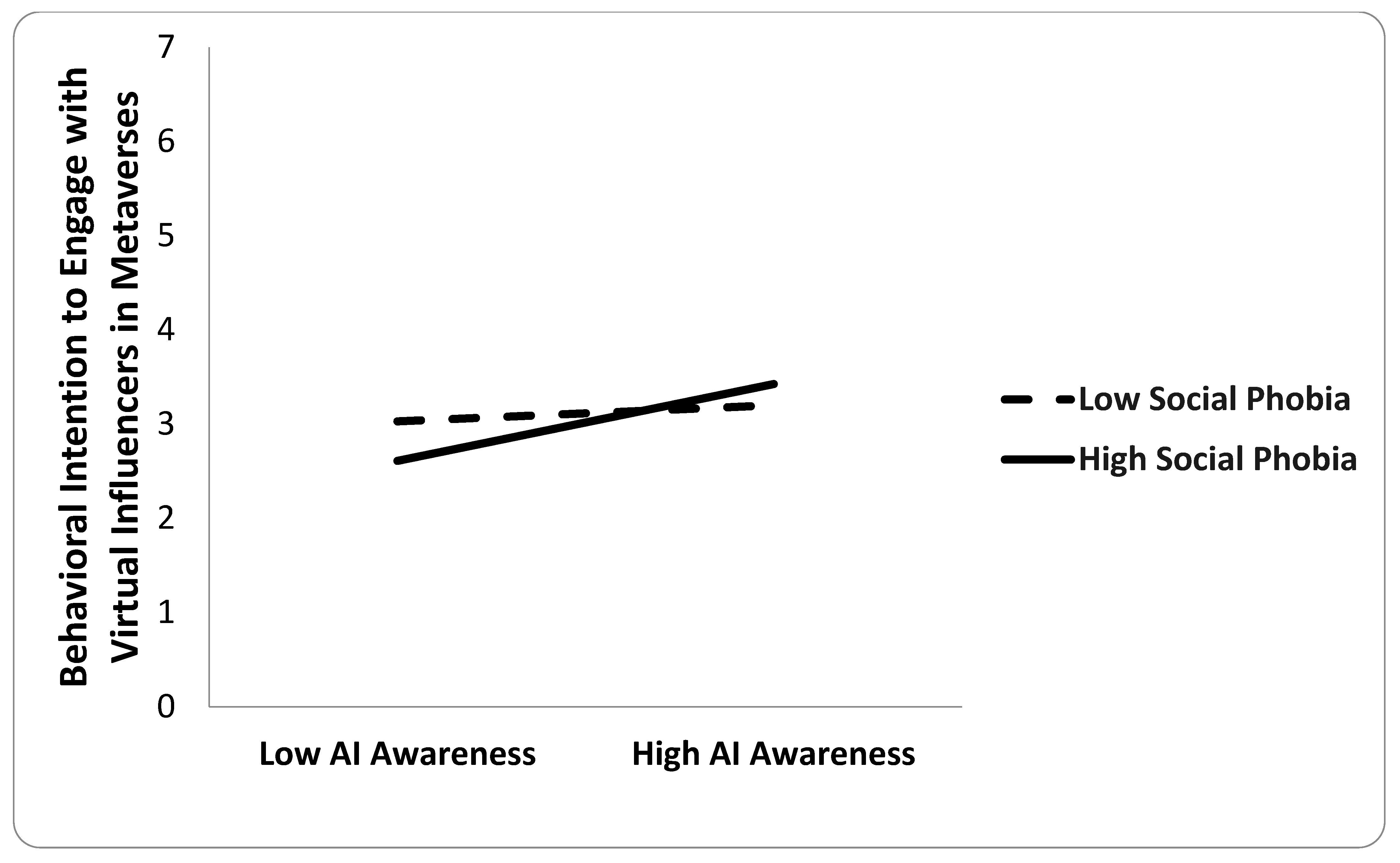

4.1.5. Moderation Effect of Social Phobia

4.2. Study 2 Results

4.2.1. Study 2 Descriptive Statistics

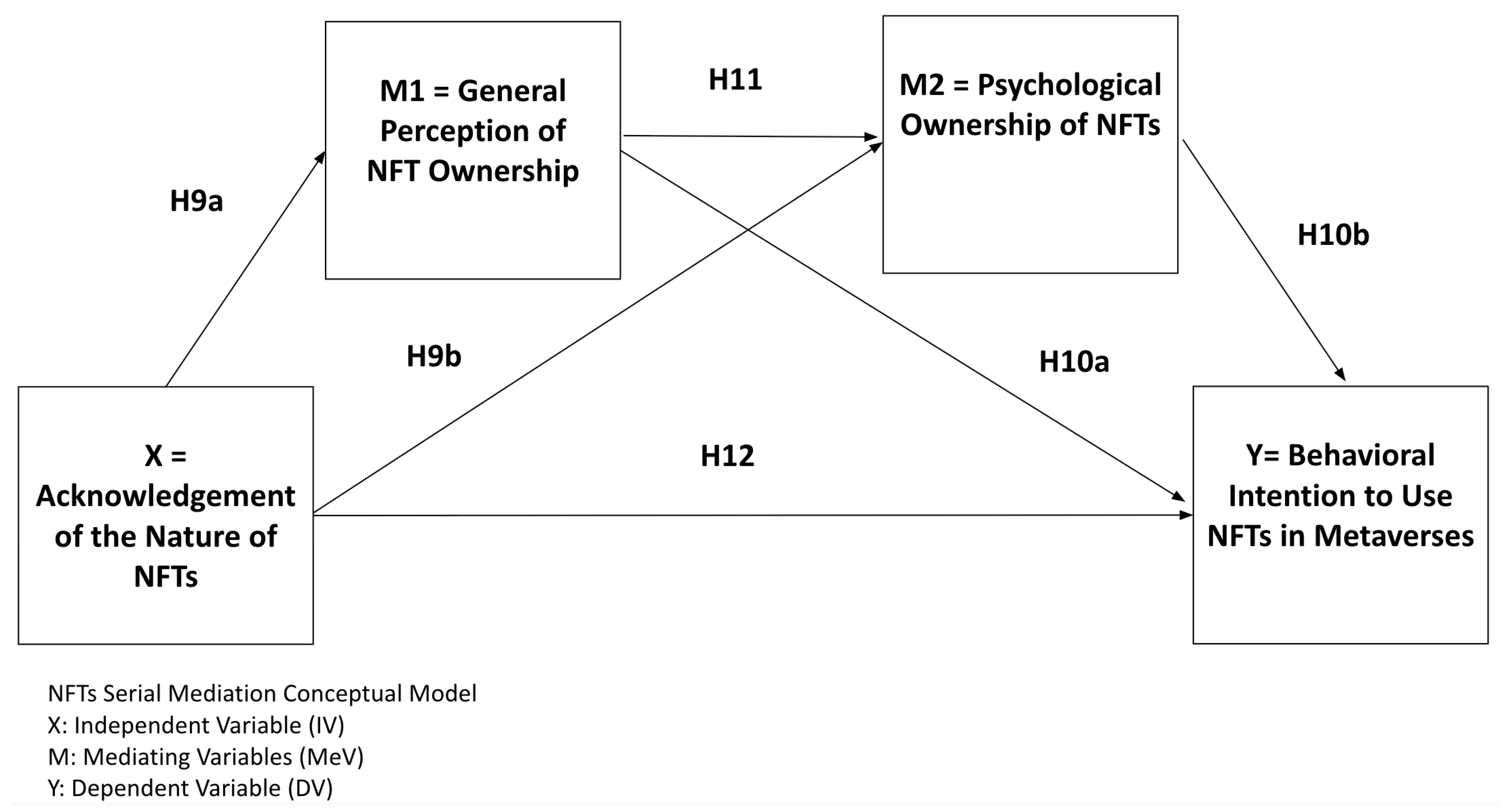

4.2.2. Serial Mediation Effects of the General Perception of NFT Ownership and Psychological Ownership of NFTs

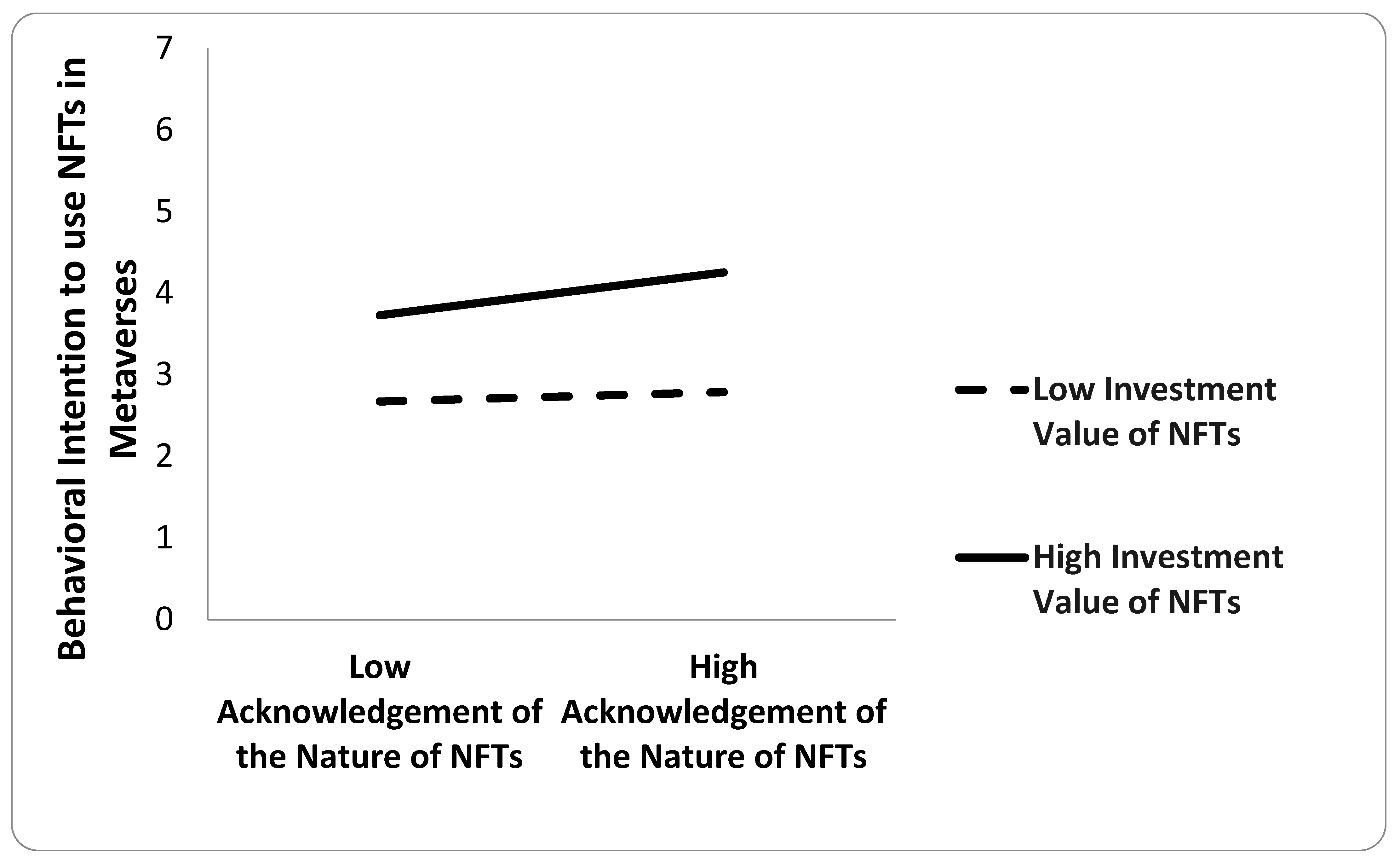

4.2.3. Moderation Effect of Investment Value of NFTs

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Key Findings and Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical and Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| NFT | Non-Fungible Token |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

References

- Stephenson, N. Snow Crash. Bantam Spectra 1992. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snow_Crash (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, L.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S.; Giannakis, M.; Al-Debei, M.M.; Dennehy, D.; Metri, B.; Buhalis, D.; Cheung, C.M.; et al. Metaverse beyond the hype: Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice, and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 66, 102542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, J. Information Bodies: Computational anxiety in Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash. Interdiscip. Lit. Stud. 2017, 19, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, J.M.; Cascio, J.; Paffendorf, J. Metaverse Roadmap: Pathways to the 3D Web. 2007. Available online: https://www.w3.org/2008/WebVideo/Annotations/wiki/images/1/19/MetaverseRoadmapOverview.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Vidal-Tomas, D. The new crypto niche: NFTs, play-to-earn, and metaverse tokens. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 47, 102742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrol, A. 7 Key Technologies that Are Powering the Metaverse. 2022. Available online: https://www.blockchain-council.org/metaverse/technologies-powering-metaverse/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Barata, J.; Kayser, I. How will the digital twin shape the future of industry 5.0? Technovation 2024, 134, 103025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, K.G.; Shah, D. Marketing in the Metaverse: Conceptual understanding, framework, and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvarikova, K.; Trnka, M.; Lăzăroiu, G. Immersive extended reality and remote sensing technologies, simulation modeling, and spatial data acquisition tools, and cooperative decision and control algorithms in a real-time interoperable decentralized Metaverse. Linguist. Philos. Investig. 2023, 22, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Sands, S.; Ferraro, C.; Tsao, H.-Y.; Mavrommatis, A. From data to action: How marketers can leverage AI. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Leszkiewicz, A.; Kumar, V.; Bijmolt, T.; Potapov, D. Digital analytics: Modeling for insights and new methods. J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 51, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W.D.; Kroschke, M.; Schmitt, B.; Kraume, K.; Shankar, V. Transforming the customer experience through new technologies. J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 51, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golf-Papez, M.; Heller, J.; Chylinski, M.; de Ruyter, K.; Keeling, D.I.; Mahr, D. Embracing falsity through the metaverse: The case of synthetic customer experiences. Bus. Horiz. 2022, 65, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollensen, S.; Kotler, P.; Opresnik, M.O. Metaverse- the new marketing universe. J. Bus. Strategy 2023, 44, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.; Humayun, M.; Brouard, M. Money, possessions, and ownership in the Metaverse: NFTs, cryptocurrencies, Web 3.0 and Wild Markets. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 153, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, M.; Sajtos, L.; Haenlein, M. Challenges and opportunities for marketing scholars in times of the fourth industrial revolution. J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 51, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Ryu, E. Unraveling the dynamics of digital equality and trust in AI-empowered metaverses and AI-VR-Convergence. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2025, 210, 123877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawlitschek, F.; Notheisen, B.; Teubner, T. A 2020 perspective on “The limits of trust-free systems: A literature review on blockchain technology and trust in the sharing economy”. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 40, 100935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V. “To comply or to react, that is the question:” The roles of humanness versus eeriness of AI-powered virtual influencers, loneliness, and threats to human identities in AI-driven digital transformation. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2023, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameye, N.; Bughin, J.; van Zeebroeck, N. How uncertainty shapes herding in the corporate use of artificial intelligence technology. Technovation 2023, 127, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, A.; Hussain, A.; Tab, M.A. Towards a more general theory of blockchain technology adoption—Investigating the role of mass media, social media, and technophilia. Technol. Soc. 2023, 73, 102225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozic, B. Consumer trust repair: A critical literature review. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Camerer, C. Not so Different After All: Cross-Discipline View of Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardon, R.; Belk, R. Materializing digital collecting: An extended view of digital materiality. Mark. Theory 2018, 18, 543–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Viswanathan, V. “Threatened and empty selves following AI-based virtual influencers”: Comparison between followers and non-followers of virtual influencers in AI-driven digital marketing. AI Soc. 2024, 40, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B. Towards an ontology and ethics of virtual influencers. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, H. Decentralized blockchain-based electronic marketplaces. Commun. AMC 2018, 61, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaswamy, A.; Moch, N.; Felten, C.; van Bruggen, G.; Wieringa, J.E.; Wirtz, J. The role of marketing in digital business platforms. J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 51, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economist. The Promise of the Blockchain: The Trust Machine. Economist 2015, 31, 27. Available online: https://www.economist.com/leaders/2015/10/31/the-trust-machine (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Boukis, A. Exploring the implications of blockchain technology for brand-consumer relationships: A future research agenda. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 29, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, M.; Pattanayak, P.; Verma, S.; Kalyanaraman, V. Blockchain Technology: Beyond Bitcoin. Appl. Innov. Rev. 2016, 2, 6–10. Available online: https://scet.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/AIR-2016-Blockchain.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Jain, G.; Kamble, S.S.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Shrivastava, A.; Belhadi, A.; Venkatesh, M. Antecedents of blockchain-enabled e-commerce platforms (BEEP) adoption by customers—A study of second-hand small and medium apparel retailers. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 149, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casino, F.; Dasaklis, T.K.; Patsakis, C. A systematic literature review of blockchain-based applications: Current status, classification, and open issues. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 36, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Xing, X. A conceptual model and case study of blockchain- enabled social media platform. Technovation 2023, 119, 102610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiblmaier, H.; Sillaber, C. The impact of blockchain on e-commerce: A framework for salient research topics. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2021, 48, 101054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahbodi, A.; Pang, G.; Peng, L. Determinants of consumers’ adoption intention for blockchain technology in e-commerce. J. Digit. Econ. 2022, 1, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Ishfaq, K.; Hussain, S.; Asmi, F.; Siddiquei, A.N.; Anwar, M.A. Investigating e-retailers’ intentions to adopt cryptocurrency considering the mediation of technostress and technology involvement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basulto, D. This Recent Move by Amazon could be a Game-Changer for Crypto. 2022. Available online: https://www.fool.com/investing/2022/09/30/this-recent-move-by-amazon-could-be-a-game-changer/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Marthews, A.; Tucker, C. What blockchain can and can’t do: Applications to marketing and privacy. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2023, 40, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.F.; Moro, S. Blockchain technology as an enabler of consumer trust: A text mining literature analysis. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 60, 101593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Miraz, M.H.; Gazi, M.A.I.; Rahaman, M.A.; Habib, M.M.; Hossain, A.I. Factors affecting cryptocurrency adoption in digital business transactions: The mediating role of customer satisfaction. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroma, J.; Rongting, Z.; Muhideen, S.; Akintunde, T.Y.; Amosun, T.S.; Dauda, S.J.; Sawaneh, I.A. Assessing citizens’ behavior towards blockchain cryptocurrency adoption in the Mano River Union States: Mediation, moderation role of trust and ethical issues. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R. How Transparent is Blockchain Technology? 2018. Available online: https://www.thefastmode.com/quick-take/12252-how-transparent-is-blockchain-technology (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Nilashi, M.; Jannach, D.; Bin Ibrahim, O.; Esfahani, M.D.; Ahmadi, H. Recommendation quality, transparency, and website quality for trust-building in recommendation agents. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016, 19, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, K.; Swanson, D. The supply chain has no clothes: Technology adoption of blockchain for supply chain transparency. Logistics 2018, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TP&P Technology. Why Blockchain Is a Key Technology for the Metaverse? 2022. Available online: https://www.tpptechnology.com/en/blog/why-blockchain-is-a-key-technology-for-the-metaverse/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Chang, S.E.; Chen, Y.C.; Lu, M.F. Supply chain re-engineering using blockchain technology: A case of smart contract based tracking process. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 144, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.M.; Saraniemi, S. Trust in blockchain-enabled exchanges: Future directions in blockchain marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2023, 51, 914–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoub, G.; Castillo, M. Blockchain in your grocery basket: Trust and traceability as a strategy. J. Bus. Strategy 2022, 43, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Sharma, S.K. Application of blockchain technology in shaping the future of food industry based on transparency and consumer trust. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 1237–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apte, S.; Petrovsky, N. Will Blockchain Technology Revolutionize Excipient Supply Chain Management? J. Excip. Food Chem. 2016, 7, 76–78. Available online: https://jefc.scholasticahq.com/article/910 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Hughes, A.; Park, A.; Kietzmann, J.; Archer-Brown, C. Beyond bitcoin: What blockchain and distributed ledger technologies mean for firms. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toufaily, E. An integrative model of trust toward crypto-tokens applications: A customer perspective approach. Digit. Bus. 2022, 2, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S.; Jin, S.V. In AI we trust? The effects of parasocial interaction and technopian versus luddite ideological views on chatbot-based customer relationship management in the emerging “feeling economy”. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, S.; Ferraro, C.; Demsar, V.; Chandler, G. False idols: Unpacking the opportunities and challenges of falsity in the context of virtual influencers. Bus. Horiz. 2022, 65, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.D.; Whaling, K.; Carrier, L.M.; Cheever, N.A.; Rokkum, J. The media and technology usage attitude scale: An empirical investigation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 2501–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayenaka, T. CGI-Created Virtual Influencers Are the New Trend in Social Media Marketing. Entrepreneur Europe. 2020. Available online: https://www.entrepreneur.com/science-technology/cgi-created-virtual-influencers-are-the-new-trend-in-social/352937 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Wagman, K.B. A New Bot on the Block: The Rise of Virtual Influencers and What It Means for Our Online Communities. 2020. Available online: http://fixingsocialmedia.mit.edu/index.html%3Fp=578.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Oliveira, A.B.S.; Chimenti, P. “Humanized robots”: A proposition of categories to understand virtual influencers. Aust. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, L. Meta-Influencers: 7 Asian Metaverse Influencers that Brands Love. 2022. Available online: https://www.tatlerasia.com/style/fashion/metafluencers-metaverse-influencers-nft-rozy-lil-miquela-ailynn-sua-imma-ayayi-zinn-plusticboy (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Hyde, J. The Ethics of ‘Virtual Influencers’. 2022. Available online: https://iconagency.com.au/news/2022-07-13-ethics-virtual-influencers (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Axhela Digital. Will AI Influencers Replace Human Influencers: Are they a Threat to Brands That Use Them? 2025. Available online: https://axheladigital.com/2025/07/13/will-ai-influencers-replace-human-influencers-are-they-a-threat-to-brands-that-use-them/?srsltid=AfmBOopHxkfFiuePbzCJimXiTOIq93llBwXHB8Mz6xG6TCPWwi9I0QUs (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Gerlich, M. The Power of Virtual Influencers: Impact on Consumer Behaviour and Attitudes in the Age of AI. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baklanov, N. The Top Virtual Instagram Influencers in 2021. 2021. Available online: https://hypeauditor.com/blog/the-top-instagram-virtual-influencers-in-2021/ (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Brougham, D.; Haar, J. Smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithms (STARA): Employees’ perceptions of our future workplace. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Yuan, Y.; Baruch, Y.; Bu, N.; Jiang, X.; Wang, K. Influences of artificial intelligence (AI) awareness on career competency and job burnout. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Guo, G.; Shu, L.; Gong, Q.; Luo, P. Investigating the double-edged sword effect of AI awareness on employee’s service innovative behavior. Tour. Manag. 2022, 92, 104564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.E. Against Technology: From the Luddites to Neo-Luddism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A. Luddite and proud: The spirit of the 19th-century textile worker lives on, if vainly. New Sci. 2011, 212, 40–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Youn, S. Why do consumers with social phobia prefer anthropomorphic customer service chatbots? Evolutionary explanations of the moderating roles of social phobia. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 62, 101644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gennaro, M.; Krumhuber, E.G.; Lucas, G. Effectiveness of an empathic chatbot in combating adverse effects of social exclusion on mood. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabholkar, P.A.; Bagozzi, R.P. An attitudinal model of technology-based self- service: Moderating effects of consumer traits and situational factors. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, S.; Navarro-Bailon, M.A.; Molina-Castillo, F.-J. Privacy Concerns in Quick Response Code Mobile Promotion: The Role of Social Anxiety and Situational Involvement. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2012, 16, 91–119. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41739750 (accessed on 22 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Peres, R.; Schreier, M.; Schweidel, D.A.; Sorescu, A. Blockchain meets marketing: Opportunities, threats, and avenues for future research. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2023, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borri, N.; Liu, Y.; Tsyvinski, A. The Economics of Non-Fungible Tokens. 2022. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4052045 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Chohan, R.; Paschen, J. NFT marketing: How marketers can use nonfungible tokens in their campaigns. Bus. Horiz. 2023, 66, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Far, S.B.; Bamakan, S.M.H.; Qu, Q.; Jiang, Q. A review of non-fungible tokens applications in the real-world and Metaverse. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 214, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takyar, A. A Complete Guide on NFT (Non-Fungible Token). 2022. Available online: https://www.leewayhertz.com/nft-non-fungible-token/#What-are-non-fungible-tokens? (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Duguleana, M.; Gîrbacia, F. Augmented reality meets Non-Fungible Tokens: Insights towards preserving property rights. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), Bari, Italy, 4–8 October 2021; pp. 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y. When makers meet the metaverse: Effects of creating NFT metaverse exhibition in maker education. Comput. Educ. 2023, 194, 104693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiort, A. Top 9 NFTs Launched by Virtual Influencers. 2021. Available online: https://www.virtualhumans.org/article/top-9-nfts-launched-by-virtual-influencers (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Coca Cola Company. Updated: Coca-Cola to Offer First-Ever NFT Collectibles in International Friendship Day Charity Auction. 2021. Available online: https://investors.coca-colacompany.com/news-events/press-releases/detail/1032/coca-cola-to-auction-its-first-ever-nft-collectibles-on-international-friendship-day (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Marr, B. Gucci Enters the Metaverse. 2022. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2022/11/30/gucci-enters-the-metaverse/?sh=6d47b2971d66 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- McDowell, M.; Shoaib, M. Louis Vuitton to Release New NFTs. 2022. Available online: https://www.voguebusiness.com/technology/louis-vuitton-to-release-new-nfts (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Apostu, S.A.; Panait, M.; Vasa, L.; Mihaescu, C.; Dobrowolski, Z. NFTs and cryptocurrencies- The metamorphosis of the economy under the sign of blockchain: A time series approach. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S. Top Luxury Fashion Brands Double-Down on NFTs Despite 2022 Crypto Fallout. 2022. Available online: https://beincrypto.com/top-luxury-fashion-brands-double-down-nfts-despite-2022-crypto-fallout/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Moore, A. The Relationship Between NFTs and the Metaverse. 2022. Available online: https://www.fintechnews.org/the-relationship-between-nfts-and-the-metaverse/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Pierce, J.L.; Kostova, T.; Dirks, K.T. The state of psychological ownership: Integrating and extending a century of research. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2003, 7, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, M. Is non-fungible token pricing driven by cryptocurrencies? Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 44, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urom, C.; Ndubuisi, G.; Guesmi, K. Dynamic dependence and predictability between volume and return of non-fungible tokens (NFTs): The roles of market factors and geopolitical risks. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 50, 103188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, R.; Schmidt, J. What Is an NFT? How Do NFTs Work? 2022. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/advisor/in/investing/cryptocurrency/what-is-an-nft-how-do-nfts-work/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Arli, D.; van Esch, P.; Bakpayev, M.; Laurence, A. Do consumers really trust cryptocurrencies? Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 39, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, C. A critical professional ethical analysis of non-fungible tokens (NFTs). J. Responsible Technol. 2022, 12, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J. Cryptopricing: Whence comes the value for cryptocurrencies and NFTs? Int. J. Res. Mark. 2023, 40, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.; Rosenzweig, C.; Moss, A.J.; Robinson, J.; Litman, L. Online panels in social science research: Expanding sampling methods beyond Mechanical Turk. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 2022–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Zinkhan, G.M. Exploring the impact of online privacy disclosures on consumer trust. J. Retail. 2006, 82, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saprikis, V.; Avlogiaris, G. Factors that determine the adoption intention of direct mobile purchases through social media apps. Information 2021, 12, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.; Davidson, J.; Churchill, L.; Sherwood, A.; Weisler, R.; Foa, E. Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN): New self-rating scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 176, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kamble, S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Kumar, V.; Belhadi, A.; Foropon, C. A machine learning based approach for predicting blockchain adoption in supply chain. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, A. How Your Brand Should Use NFTs. Harvard Business Review. 2022. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/02/how-your-brand-should-use-nfts (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Gurzki, H. How Luxury Brands Are Manufacturing Scarcity in the Digital Economy. Harvard Business Review. 2022. Available online: https://hbr.org/2022/01/how-luxury-brands-are-manufacturing-scarcity-in-the-digital-economy?ab=at_art_art_1x4_s04 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Colicev, A. How can non-fungible tokens bring value to brands. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2023, 40, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, R.; de Bellis, E.; Brandes, L.; Clegg, M.; Lamberton, C.; Reibstein, D.; Rohlfsen, F.; Schmitt, B.; Zhang, J.Z. Crypto-marketing: How non-fungible tokens (NFTs) challenge traditional marketing. Mark. Lett. 2022, 33, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiblmaier, H. Beyond blockchain: How tokens trigger the internet of value and what marketing researchers need to know about them. J. Mark. Commun. 2023, 29, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagidyala, A. Why NFTs will Shape the Future of Gaming. 2022. Available online: https://www.entrepreneur.com/money-finance/why-nfts-will-shape-the-future-of-gaming/438878 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Chalmers, D.; Fisch, C.; Matthews, R.; Quinn, W.; Recker, J. Beyond the bubble: Will NFTs and digital proof of ownership empower creative industry entrepreneurs? J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2022, 17, e00309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, Y. Non-fungible token-enabled entrepreneurship: A conceptual framework. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2022, 18, 300323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadini, M.; Alessandretti, L.; Di Giacinto, F.; Martino, M.; Aiello, L.M.; Baronchelli, A. Mapping the NFT revolution: Market trends, trade networks, and visual features. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.00647v4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Leenders, M.A.A.M.; Cong, L.M. Ownership in the virtual world and the implications for long-term user innovation success. Technovation 2018, 78, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, B. The Different Types of NFTs: A Simple Guide. 2022. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/learn/the-different-types-of-nfts-a-simple-guide/ (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Yuan, F.; Huang, X.; Zheng, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yan, X.; Gu, S.; Peng, Y. The evolution and optimization strategies for a PBFT consensus algorithm for consortium blockchains. Information 2025, 16, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Zuo, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Shu, W.; Tian, Z.; Ye, C.; Yang, J.; Mao, Z.; Huang, X.; Gu, S.; et al. AI-driven optimization of blockchain scalability, security, and privacy protection. Algorithms 2025, 18, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha | Sample Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| BTP: Blockchain Transparency Perception (IV) | 7 | 0.915 | “Blockchain promotes transparency”, “Blockchain achieves decentralized security”, “Blockchain prevents financial fraud” |

| BTR: Blockchain Trust (Mediator) | 4 | 0.959 | “Blockchain is a trustworthy technology”, “The blockchain technology can be relied on to keep its promises”, “I can count on the blockchain technology to protect customers’ personal information from unauthorized use” |

| TPM: Technopian Perspective on Metaverses (Moderator) | 5 | 0.942 | “With metaverses, anything is possible”, “The metaverse technology is a driver of social progress”, “Metaverses bring many benefits to people” |

| CUM: Cryptocurrency Adoption Intention in Metaverses (DV) | 5 | 0.978 | “I will use cryptocurrency for virtual commerce in metaverses in the future”, “I will use cryptocurrency for business purposes in metaverses”, “I will use cryptocurrency when I need swift virtual commerce transactions in metaverses” |

| AIA: AI-Algorithm Awareness (IV) | 4 | 0.910 | “I think AI might replace our jobs”, “Given that AI is being widely used in the workplace, I’m concerned about my future in various industry sectors”, “I think there is a possibility that my current job will be replaced by AI” |

| NLM: Neo-Luddism Perspective on the Metaverse (Mediator) | 5 | 0.925 | “The Metaverse is a threat to natural and authentic ways of our lives,” “The Metaverse makes people waste too much time”, “The Metaverse makes people more isolated” |

| SOP: Social Phobia (Moderator) | 5 | 0.905 | “Talking to strangers scares me”, “I avoid talking to people I do not know”, “I avoid speaking to people for fear of embarrassment” |

| VIE: Virtual Influencer Engagement Intention in Metaverses (DV) | 5 | 0.970 | “I intend to engage with virtual influencers in the Metaverse in the near future”, “I predict I would interact with virtual influencers in the Metaverse in the near future,” “I plan to engage with virtual influencers in the Metaverse for virtual commerce in the near future” |

| Variable | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha | Sample Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| NFT: Acknowledgment of the Nature of NFTs (IV) | 5 | 0.905 | “NFTs are unique”, “NFT cannot be copied, substituted, or subdivided”, “NFTs are non-fungible” |

| GPO: General Perception of NFT Ownership (Mediator) | 3 | 0.903 | “NFTs allow the buyer to own the original item”, “NFTs can serve as a proof of ownership”, “NFTs can be used to represent ownership of unique items” |

| PPO: Perceived Psychological Ownership of NFTs (Mediator) | 5 | 0.954 | “I sense that NFTs could be mine”, “I feel some degree of personal ownership for NFTs”, “I think I can own NFTs” |

| PIV: Perceived Investment Value of NFTs (Moderator) | 3 | 0.959 | “NFTs are valuable”, “NFTs are assets”, “NFTs are worth investing in” |

| NFM: Behavioral Intention to use NFTs in Metaverses (DV) | 7 | 0.980 | “I predict I would use NFTs (non-fungible tokens) in metaverses in the near future”, “I intend to purchase NFTs (non-fungible tokens) using cryptocurrency in metaverses in the near future”, “I intend to sell NFTs (non-fungible tokens) using cryptocurrency in metaverses in the near future” |

| Variable | M | SD | 1. BTP | 2. BTR | 3. TPM | 4. CUM | 5. AIA | 6. NLM | 7. SOP | 8. VIE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BTP: Blockchain Transparency (IV) | 4.3203 | 1.30025 | 1 | |||||||

| 2. BTR: Blockchain Trust (Mediator) | 3.9017 | 1.57771 | 0.789 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. TPM: Technopian Perspective on the Metaverse (Moderator) | 4.3710 | 1.62717 | 0.586 ** | 0.577 ** | 1 | |||||

| 4. CUM: Cryptocurrency Usage Intention in the Metaverse (DV) | 3.1000 | 2.01285 | 0.570 ** | 0.627 ** | 0.511 ** | 1 | ||||

| 5. AIA: AI-Algorithm Awareness (IV) | 3.5162 | 1.68026 | 0.116 * | 0.114 * | 0.121 * | 0.221 ** | 1 | |||

| 6. NLM: Neo-Luddism Perspective on Metaverses (Mediator) | 3.8420 | 1.61615 | −0.009 | −0.049 | −0.181 * | −0.032 | 0.446 ** | 1 | ||

| 7. SOP: Social Phobia (Moderator) | 3.5000 | 1.64711 | 0.041 | 0.034 | 0.035 | 0.028 | 0.290 ** | 0.243 ** | 1 | |

| 8. VIE: Virtual Influencer Engagement Intention in the Metaverse (DV) | 3.1922 | 1.85299 | 0.493 ** | 0.569 ** | 0.616 ** | 0.690 ** | 0.221 ** | −0.162 ** | 0.028 | 1 |

| Relationship | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Confidence Interval | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| Blockchain Transparency Perception → Trust in Blockchain Technologies → Intention to Adopt Cryptocurrency in Metaverses | 0.8756 (p = 0.0000) | 0.3053 (p = 0.0021) | 0.5702 | 0.3935 | 0.7394 | Partial Mediation |

| Relationship | Total E. | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Confidence Interval | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| AI-Algorithm Awareness → Neo-Luddism Perspective on the Metaverse → Intention to Engage with Virtual Influencers in Metaverses | 0.2443 (p = 0.0000) | 0.4018 (p = 0.0000) | −0.1575 | −0.2435 | −0.0859 | Partial Mediation |

| Variable | M | SD | 1. NFT | 2. GPO | 3. PPO | 4. PIV | 5. NFM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NFT: Acknowledgment of the Nature of NFTs (IV) | 4.8163 | 1.54688 | 1 | ||||

| 2. GPO: General Perception of NFT Ownership | 4.8697 | 1.71161 | 0.733 ** | 1 | |||

| 3. PPO: Perceived Psychological Ownership of NFTs (Mediator) | 3.9927 | 1.93388 | 0.585 ** | 0.516 ** | 1 | ||

| 4. PIV: Perceived Investment Value of NFTs (Moderator) | 4.5110 | 1.87192 | 0.672 ** | 0.720 ** | 0.725 ** | 1 | |

| 5. NFM: Behavioral Intention to use NFTs in Metaverses (DV) | 3.5558 | 2.02372 | 0.461 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.755 ** | 0.624 ** | 1 |

| Relationship | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Confidence Interval | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| NFT Nature Acknowledgment → Psychological Ownership of NFTs → Intention to Use NFTs in Metaverses | 0.5999 (p = 0.0000) | 0.0318 (p = 0.5883) | 0.5680 | 0.4469 | 0.6911 | Total Mediation |

| NFT Nature Acknowledgement → General Ownership Perception of NFTs → Psychological Ownership of NFTs → Intention to Use NFTs in Metaverses | 0.5999 (p = 0.0000) | 0.0475 (p = 0.5257) | 0.1041 | 0.0279 | 0.1941 | Total Serial Mediation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, S.V. “In Metaverse Cryptocurrencies We (Dis)Trust?”: Mediators and Moderators of Blockchain-Enabled Non-Fungible Token (NFT) Adoption in AI-Powered Metaverses. AI 2025, 6, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6110286

Jin SV. “In Metaverse Cryptocurrencies We (Dis)Trust?”: Mediators and Moderators of Blockchain-Enabled Non-Fungible Token (NFT) Adoption in AI-Powered Metaverses. AI. 2025; 6(11):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6110286

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Seunga Venus. 2025. "“In Metaverse Cryptocurrencies We (Dis)Trust?”: Mediators and Moderators of Blockchain-Enabled Non-Fungible Token (NFT) Adoption in AI-Powered Metaverses" AI 6, no. 11: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6110286

APA StyleJin, S. V. (2025). “In Metaverse Cryptocurrencies We (Dis)Trust?”: Mediators and Moderators of Blockchain-Enabled Non-Fungible Token (NFT) Adoption in AI-Powered Metaverses. AI, 6(11), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6110286