Artificial Intelligence-Driven Facial Image Analysis for the Early Detection of Rare Diseases: Legal, Ethical, Forensic, and Cybersecurity Considerations

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Medicine, specifically genetics;

- Technology, with a focus on cutting-edge AI models for facial analysis;

- Law, with a focus on privacy laws (e.g., GDPR);

- Ethics, i.e., ethical considerations around using citizen data;

- Forensics in identifying missing persons and suspects within a legal framework;

- Cybersecurity in addressing security risks of handling highly sensitive facial and genetic data.

- -

- Raise awareness: Highlight the transformative potential of AI in healthcare, particularly for rare diseases where early detection is critical;

- -

- Spark ethical discussion: Provoke debate about the ethical boundaries of the use of government-held data, emphasizing the individual’s right to privacy versus the potential public health benefits;

- -

- Inform policymakers: Provide insights to help policymakers craft responsible legislation governing the use of AI for genetic screening within existing privacy laws;

- -

- Highlight cybersecurity risks: Provide information on the specific vulnerabilities associated with AI-assisted genetic analysis and the handling of large amounts of AI data, highlighting the need for robust security measures;

- -

- Explore forensic applications: Open a discourse on the potential and ethical considerations of using AI facial analysis tools in forensics;

- -

- Stimulate further research: Identify gaps in current knowledge and technology and challenge researchers to address limitations, biases, and ethical dilemmas in the field.

2. Concept and Methods

2.1. The Concept

- The technological advancements enabling early detection;

- Conflicting perspectives on privacy in the age of AI;

- The potential for AI-powered forensics;

- The urgency of cybersecurity safeguards in this domain.

2.2. The Outline

2.2.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Government-held national ID databases (ensuring adherence to all legal and privacy requirements);

- Publicly available image databases with appropriate permissions and consent (only if the study extends beyond ID databases);

- Normalization: Standardization of image size, resolution, and orientation;

- Face detection and extraction: Locating and cropping faces within the images;

- Anonymization and/or pseudonymization: Implementing appropriate techniques to protect individual identities in line with ethical and privacy regulations discussed in the Legal section of this paper.

2.2.2. AI Model Development and Selection

- Choice of AI Algorithm: AI algorithms for facial phenotyping:

- Aspects of strengths, risks, and limitations of deep learning models like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in this context;

- Considerations of commercially available algorithms like Face2Gene with analysis of their risks and limitations and necessary adaptations.

- Training and Validation Dataset: Design of dataset used to train the AI system:

- Source of labeled images (known rare disease diagnoses with corresponding photos);

- Data splitting strategies (training, validation, testing);

- Identification of potential biases and methods employed for mitigation.

- Evaluation Metrics: The following are used to assess the AI model’s effectiveness:

- Accuracy, precision, recall, sensitivity, and specificity for different genetic conditions;

- Consider using receiver operating characteristic curves and area under the curve to evaluate overall performance.

2.2.3. AI Implementation and Data Analysis

- Framework: Appropriate AI framework, considering requirements such as the following:

- Scalability for population-level screening;

- Interpretability (potential use of explainable AI or XAI);

- Integration with existing healthcare/government systems.

- Deployment and Security:

- Secure storage and processing of sensitive facial image data, as dictated by legal and cybersecurity considerations;

- Protocols for encryption and access controls;

- Strategies to prevent data leakage and malicious attacks.

- Data Analysis:

- AI-generated data will lead to valuable population prevalence studies;

- Statistical analysis methods for data interpretation and visualization.

2.2.4. Ethical, Legal, and Regulatory Considerations

- Informed Consent: Consideration of an opt-in or opt-out model to be applied and the mechanisms in place to protect individual choice and privacy;

- Transparency: Communication of the findings and their implications to the public and healthcare providers;

- Regulatory Compliance: Ensure the concept fully aligns with the following:

- GDPR in the EU context, as well as other relevant national legislation;

- Medical device regulations (if the AI system is classified as such);

- Evolving regulations specific to AI, such as the EU AI Act.

2.2.5. Forensic Applications

- Person Identification: Workflow protocols about how the AI system could aid in the following:

- Matching missing persons with NID records;

- Identification of suspects (ethical considerations must be emphasized).

- Phenotyping: Potential to predict traits from images relevant to forensics (age, ancestry, etc.)—acknowledgment of limitations and need for validation.

2.2.6. Limitations and Future Directions

- Acknowledge limitations: Dataset biases, AI errors, and the need for further research to optimize accuracy and handle rare conditions;

- Future Directions: Recommendation of avenues such as the following:

- Expanding image datasets for inclusivity;

- Research on synthetic image generation for data augmentation;

- Integration with genetic sequencing for higher precision.

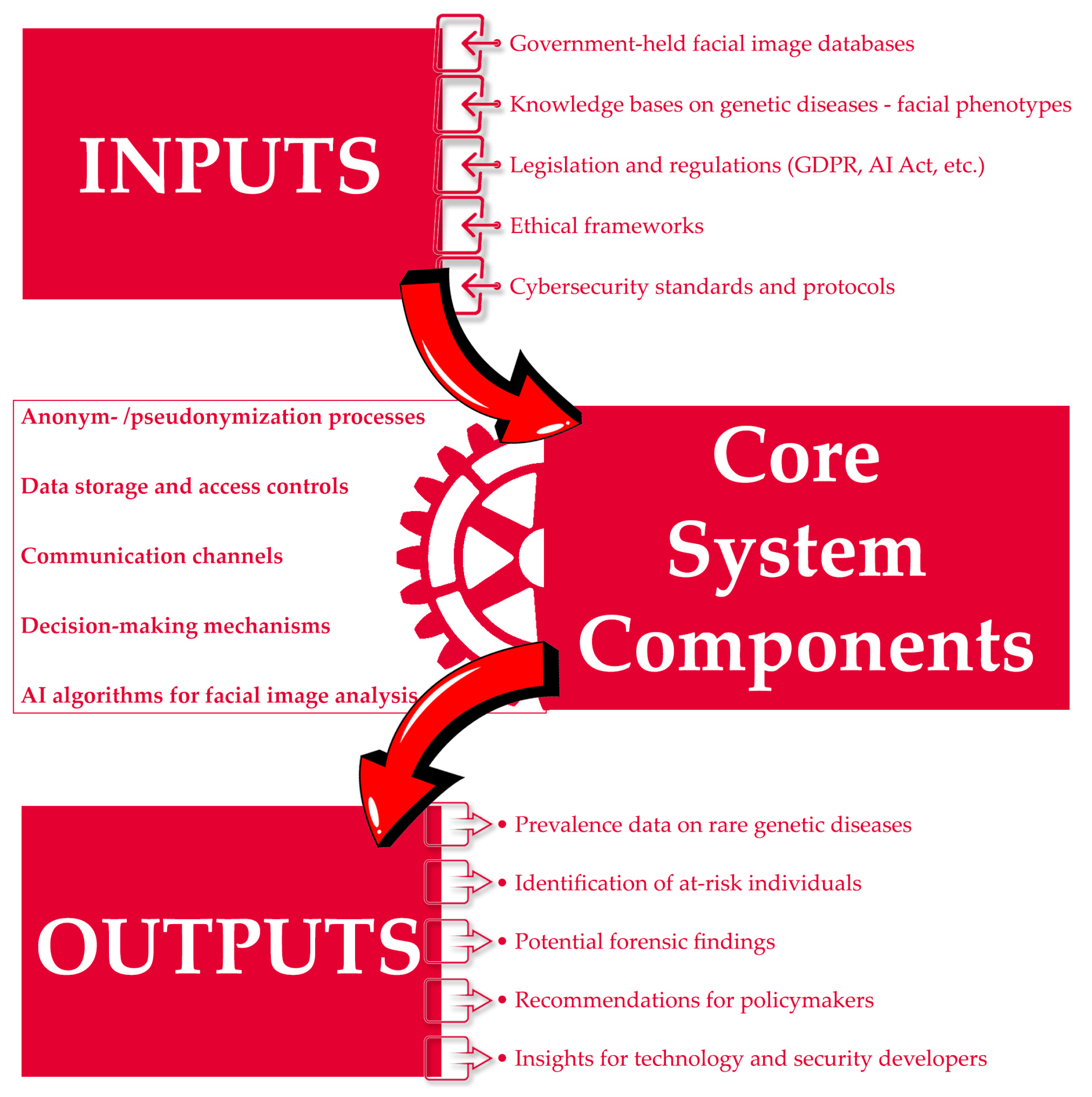

2.3. Conceptual System Model

- Facial image databases maintained by the government;

- Knowledge repositories on genetic diseases and corresponding facial phenotypes;

- Applicable legislation and regulations (such as GDPR, AI Act, etc.);

- Ethical guidelines;

- Cybersecurity standards and protocols.

- AI algorithms designed for facial image analysis;

- Processes for anonymization and pseudonymization;

- Data storage and access control mechanisms;

- Decision-making frameworks (e.g., identifying cases for further evaluation);

- Communication channels (e.g., dissemination of results for public health interventions).

- Data on the prevalence of rare genetic diseases;

- Identification of individuals at risk;

- Potential findings for forensic applications;

- Policy recommendations for lawmakers;

- Insights for developers in technology and security sectors.

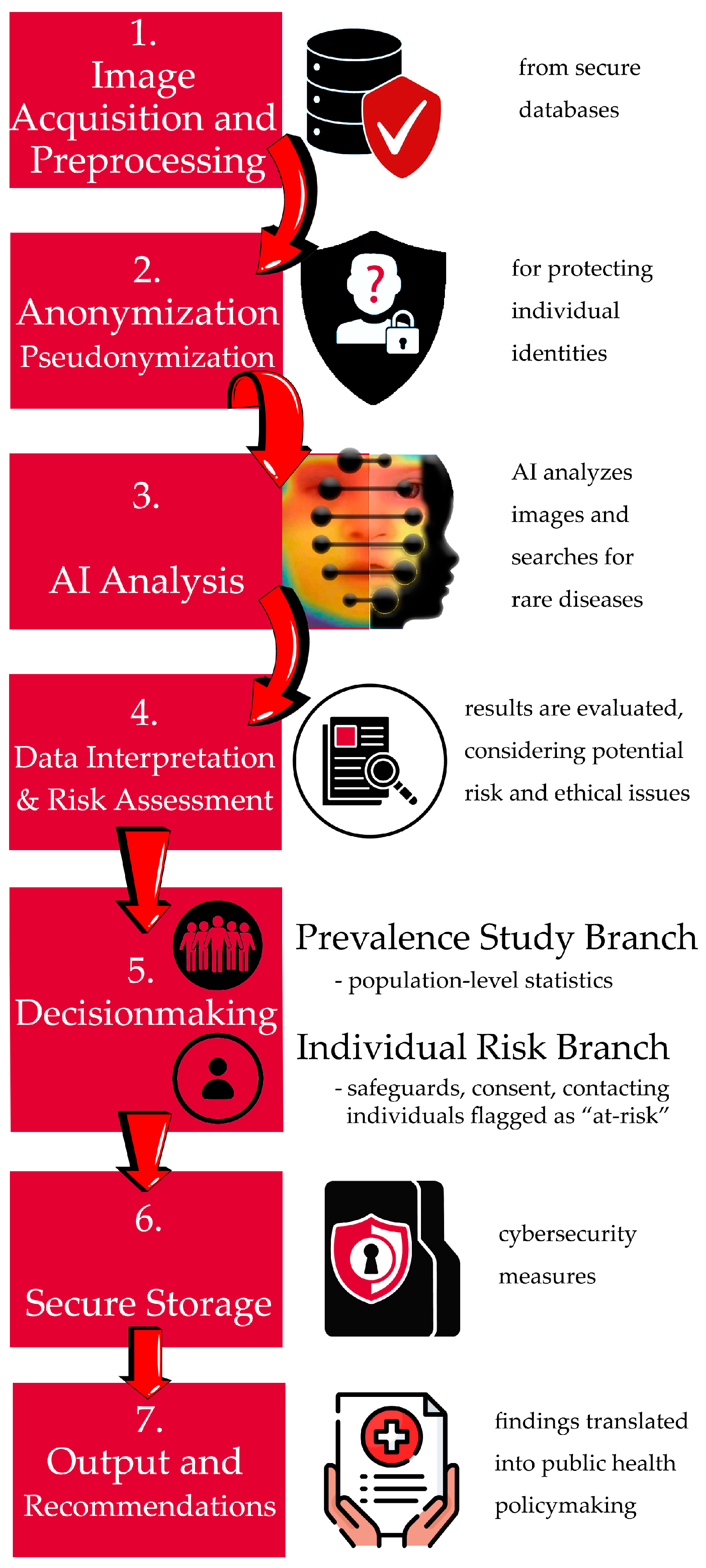

2.4. Workflow-Based System Model

- Image acquisition and preprocessing: Images are obtained from secure databases, ensuring that all legal and privacy requirements are met. These images are then standardized in terms of size, resolution, and orientation to prepare them for AI analysis;

- Anonymization/pseudonymization: Techniques such as anonymization and pseudonymization are applied to the images to protect individual identities in compliance with ethical and privacy regulations;

- AI analysis: The AI model processes the images using advanced algorithms to identify potential phenotypic markers indicative of rare genetic diseases;

- Data interpretation and risk assessment: The results generated by the AI model are carefully evaluated, considering potential risks and ethical implications. This step ensures that the analysis is accurate and that any identified risks are appropriately managed;

- Decision-making:

- Prevalence study branch: Anonymized data are utilized to contribute to population-level statistics, helping to map the prevalence of rare genetic diseases without revealing individual identities;

- Individual risk branch: With adequate safeguards and informed consent in place, individuals flagged as potentially at-risk by the AI analysis may be contacted for further assessment or preventive measures.

- Secure storage: All data, including images and analysis results, are stored securely, with strict access controls and robust cybersecurity measures to prevent unauthorized access and data breaches;

- Output and recommendations: The findings from the AI analysis are translated into actionable insights and recommendations. These outputs can be used for various purposes, including public health interventions, policymaking, and forensic applications, ensuring that the data are utilized effectively while maintaining privacy and security.

Practical Challenges Specific to Forensic Applications

2.5. Review Methodology

2.6. General Legal Limitations and Considerations

- (a)

- Photos and NUTS 2 location only for the prevalence study;

- (b)

- Photos and the assigned pseudonymous code for studies with an option to identify those at risk and facilitate preventive actions, with a separate database allowing identification when necessary.

2.7. Privacy Safeguards in the Study Design

2.8. Cybersecurity Aspects and Specific Strategies for Mitigating Risks

3. Discussion

4. Application in the United States: Integration with National Health Databases

5. Application in the European Union: Cross-Border Data Sharing and GDPR Compliance

- Diverse data collection: Collect comprehensive datasets from underrepresented populations, including different ethnicities, ages, and genders, to reduce bias in AI models;

- Bias detection and mitigation: Develop and implement fairness-aware algorithms and bias correction techniques. Use transfer learning to improve model generalizability and reduce bias;

- Explainable AI (XAI): Focus on building models that provide transparent and interpretable results to build trust and facilitate bias identification;

- Robust validation frameworks: Establish rigorous validation protocols that assess AI models across diverse demographic groups before deployment;

- Multidisciplinary collaboration: Encourage collaboration between geneticists, data scientists, ethicists, and legal experts to ensure comprehensive evaluation and ethical deployment;

- Standardized protocols: Develop standardized data collection, model training, and validation protocols across jurisdictions to improve reliability and acceptability.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Key Points

- AI’s potential in genetic disease screening: Artificial intelligence and facial recognition technologies (like Face2Gene) have revolutionized early diagnosis of rare genetic diseases. Analyzing facial images for phenotypic traits saves time and resources compared to traditional biological sample testing;

- Population-level vs. individual screening: AI-driven phenotyping can be used for both large-scale population studies (to map disease prevalence) and to identify individuals at risk (enabling preventive measures);

- Privacy and ethical concerns: The use of facial images, which can reveal sensitive genetic information, raises significant concerns about data protection, consent, and potential for discrimination or misuse;

- Legal considerations within the EU: Implementing AI-powered screening on national ID databases requires overcoming hurdles posed by the EU’s stringent privacy laws (GDPR). Consent, a clear legal basis (such as public interest or health), and robust security measures are essential;

- The impact of AI regulation: Medical device regulations and the recently passed EU Artificial Intelligence Act will shape the development and deployment of AI tools in this area;

- Forensic applications: AI-based phenotyping could greatly benefit missing persons investigations and suspect identification. However, profound ethical debates are needed to ensure responsible implementation in law enforcement contexts.

6.2. Main Conclusions

- AI-powered phenotyping holds immense promise for revolutionizing the diagnosis and management of rare genetic diseases;

- The EU’s strong privacy framework poses both challenges and safeguards when considering large-scale genetic screening programs;

- Advancing this technology demands meticulous attention to ethics, informed consent, and mitigation of potential biases or misuse;

- Careful legal development and further research are needed, especially for the complex ethical issues surrounding the use of AI-based phenotyping in forensic contexts.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Directorate General for Research and Innovation. Collaboration: A Key to Unlock the Challenges of Rare Diseases Research; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Haendel, M.; Vasilevsky, N.; Unni, D.; Bologa, C.; Harris, N.; Rehm, H.; Hamosh, A.; Baynam, G.; Groza, T.; McMurry, J.; et al. How many rare diseases are there? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, L. 2009 ANNUAL REPORT of the Chief Medical Officer. 2010. Available online: http://www.sthc.co.uk/documents/cmo_report_2009.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Dawkins, H.J.; Molster, C.M.; Youngs, L.M.; O’Leary, P.C.; Noc, T.N.O.C. Awakening Australia to Rare Diseases: Symposium report and preliminary outcomes. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2011, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, A.W.; Senior, T.P. The common problem of rare disease in general practice. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 185, 82–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox-Brinkman, J.; Vedder, A.; Hollak, C.; Richfield, L.; Mehta, A.; Orteu, K.; Wijburg, F.; Hammond, P. Three-dimensional face shape in Fabry disease. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 15, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, P.; Suttie, M. Large-scale objective phenotyping of 3D facial morphology. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 33, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, D.; Zheng, Y.-Y.; Xin, Y.; Sun, L.; Yang, H.; Lin, M.-Y.; Liu, C.; Li, B.-N.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Zhuang, J.; et al. Genetic syndromes screening by facial recognition technology: VGG-16 screening model construction and evaluation. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, H.; De Jong, G.; Maal, T.; Claes, P. Static and Motion Facial Analysis for Craniofacial Assessment and Diagnosing Diseases. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 2022, 5, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roosenboom, J.; Hens, G.; Mattern, B.C.; Shriver, M.D.; Claes, P. Exploring the Underlying Genetics of Craniofacial Morphology through Various Sources of Knowledge. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudding-Byth, T.; Baxter, A.; Holliday, E.G.; Hackett, A.; O’Donnell, S.; White, S.M.; Attia, J.; Brunner, H.; De Vries, B.; Koolen, D.; et al. Computer face-matching technology using two-dimensional photographs accurately matches the facial gestalt of unrelated individuals with the same syndromic form of intellectual disability. BMC Biotechnol. 2017, 17, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, A.R.; Rosenbaum, K.; Tor-Diez, C.; Summar, M.; Linguraru, M.G. Development and evaluation of a machine learning-based point-of-care screening tool for genetic syndromes in children: A multinational retrospective study. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e635–e643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P. Smartphone Mobile Network Subscriptions Worldwide 2016–2028. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide (accessed on 23 September 2023).

- Gurovich, Y.; Hanani, Y.; Bar, O.; Nadav, G.; Fleischer, N.; Gelbman, D.; Basel-Salmon, L.; Krawitz, P.M.; Kamphausen, S.B.; Zenker, M.; et al. Identifying facial phenotypes of genetic disorders using deep learning. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latorre-Pellicer, A.; Ascaso, Á.; Trujillano, L.; Gil-Salvador, M.; Arnedo, M.; Lucia-Campos, C.; Antoñanzas-Pérez, R.; Marcos-Alcalde, I.; Parenti, I.; Bueno-Lozano, G.; et al. Evaluating Face2Gene as a Tool to Identify Cornelia de Lange Syndrome by Facial Phenotypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Z.; Hazel, J.W.; Clayton, E.W.; Vorobeychik, Y.; Kantarcioglu, M.; Malin, B.A. Sociotechnical safeguards for genomic data privacy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D. Australian Biometrics and Global Surveillance. Int. Crim. Justice Rev. 2007, 17, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, I.N. Facial recognition in police hands: Assessing the ‘Clearview case’ from a European perspective. New J. Eur. Crim. Law. 2020, 11, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics. Overview. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the European Health Data Space. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52022PC0197 (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Kabata, F.; Thaldar, D. The human genome as the common heritage of humanity. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1282515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabani, M.; Borry, P. Rules for processing genetic data for research purposes in view of the new EU General Data Protection Regulation. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 26, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lwoff, L. Council of Europe adopts protocol on genetic testing for health purposes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 17, 1374–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council of the European Union. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Laying down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and Amending Certain Union Legislative Acts. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52021PC0206 (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Council of the European Union. Artificial Intelligence Act: Council calls for Promoting Safe AI That Respects Fundamental Rights. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/12/06/artificial-intelligence-act-council-calls-for-promoting-safe-ai-that-respects-fundamental-rights (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Council of the European Union. Transport, Telecommunications and Energy Council (Telecommunications), 6 December 2022. Meeting n°3917-1. 2022. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/tte/2022/12/06/ (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Directorate General for Communication European Parliament. Artificial Intelligence Act: Deal on Comprehensive Rules for Trustworthy AI. 2023. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/pdfs/news/expert/2023/12/press_release/20231206IPR15699/20231206IPR15699_en.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- European Commission. White Paper on Artificial Intelligence a European Approach to Excellence and Trust. 2020. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/white-paper-artificial-intelligence-european-approach-excellence-and-trust_en (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Thurzo, A.; Stanko, P.; Urbanova, W.; Lysy, J.; Suchancova, B.; Makovnik, M.; Javorka, V. The WEB 2.0 Induced Paradigm Shift in the e-Learning and the Role of Crowdsourcing in Dental Education. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2010, 111, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Thurzo, A.; Jančovičová, V.; Hain, M.; Thurzo, M.; Novák, B.; Kosnáčová, H.; Lehotská, V.; Varga, I.; Kováč, P.; Moravanský, N. Human Remains Identification Using Micro-CT, Chemometric and AI Methods in Forensic Experimental Reconstruction of Dental Patterns after Concentrated Sulphuric Acid Significant Impact. Molecules 2022, 27, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurzo, A.; Strunga, M.; Havlínová, R.; Reháková, K.; Urban, R.; Surovková, J.; Kurilová, V. Smartphone-Based Facial Scanning as a Viable Tool for Facially Driven Orthodontics? Sensors 2022, 22, 7752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, I.; Oliva, G.; Vitale, G.; Bellugi, B.; Bertana, G.; Focardi, M.; Grassi, S.; Dalessandri, D.; Pinchi, V. A Semi-Automatic Method on a Small Italian Sample for Estimating Sex Based on the Shape of the Crown of the Maxillary Posterior Teeth. Healthcare 2023, 11, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlQahtani, S.M.; Almutairi, D.S.; BinAqeel, E.A.; Almutairi, R.A.; Al-Qahtani, R.D.; Menezes, R.G. Honor Killings in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2022, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameriere, R.; Scendoni, R.; Ferrante, L.; Mirtella, D.; Oncini, L.; Cingolani, M. An Effective Model for Estimating Age in Unaccompanied Minors under the Italian Legal System. Healthcare 2023, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richmond, S.; Howe, L.J.; Lewis, S.; Stergiakouli, E.; Zhurov, A. Facial Genetics: A Brief Overview. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goddard, M. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): European Regulation that has a Global Impact. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 59, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruschka, N.; Mavroeidis, V.; Vishi, K.; Jensen, M. Privacy Issues and Data Protection in Big Data: A Case Study Analysis under GDPR. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Seattle, WA, USA, 10–13 December 2018; pp. 5027–5033. [Google Scholar]

- Basch, C.H.; Hillyer, G.C.; Samuel, L.; Datuowei, E.; Cohn, B. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing in the news: A descriptive analysis. J. Community Genet. 2022, 14, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalokairinou, L.; Howard, H.C.; Slokenberga, S.; Fisher, E.; Flatscher-Thöni, M.; Hartlev, M.; van Hellemondt, R.; Juškevičius, J.; Kapelenska-Pregowska, J.; Kováč, P.; et al. Legislation of direct-to-consumer genetic testing in Europe: A fragmented regulatory landscape. J. Community Genet. 2018, 9, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Feng, X.; Cao, X.; Xu, X.; Hu, D.; López, M.B.; Liu, L. Facial Kinship Verification: A Comprehensive Review and Outlook. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 1494–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shade, J.; Coon, H.; Docherty, A.R. Ethical implications of using biobanks and population databases for genetic suicide research. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B 2019, 180, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Position of the European Parliament Adopted at First Reading on 13 March 2024 with a View to the Adoption of Regulation (EU) 2024/… of the European Parliament and of the Council Laying down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence and Amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2024-0138_EN.html (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Coley, R.Y.; Johnson, E.; Simon, G.E.; Cruz, M.; Shortreed, S.M. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in the Performance of Prediction Models for Death by Suicide after Mental Health Visits. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olczak, K.; Pawlicka, H.; Szymański, W. Root and canal morphology of the maxillary second premolars as indicated by cone beam computed tomography. Aust. Endod. J. 2023, 49, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumaka, A.; Cosemans, N.; Lulebo Mampasi, A.; Mubungu, G.; Mvuama, N.; Lubala, T.; Mbuyi-Musanzayi, S.; Breckpot, J.; Holvoet, M.; De Ravel, T.; et al. Facial dysmorphism is influenced by ethnic background of the patient and of the evaluator. Clin. Genet. 2017, 92, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, O.R. Marijuana: Forensics of Abuse, Medical Uses, Controversy, and AI. Forensic Sci. 2023, 3, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováč, P.; Alexandra, B.; Ivan, V.; Lukáš, M.; Michal, A.; Martin, S.; Thurzo, A. Phenotyping Genetic Diseases Through Artificial Intelligence Use of Large Datasets of Government-stored Facial Photographs: Concept, Legal Issues, and Challenges in the European Union. Preprints 2023, 2023040344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GDPR Data Processing Legal Basis | Prevalence Study | Individual Risk Study |

|---|---|---|

| Article 6 (1) (a) Data subject consent | Unsuitable due to lacking possibility to identify data subject | Suitable with opt-in study design |

| Article 6 (1) (b) Performance of a contract to which the data subject is party or in order to take steps at the request of the data subject prior to entering into a contract | Unsuitable due to the absence of contract | Unsuitable due to the absence of contract |

| Article 6 (1) (c) For compliance with a legal obligation | Suitable after adoption of appropriate legislation | Only marginally suitable after adoption of appropriate legislation |

| Article 6 (1) (d) To protect the vital interests of the data subject | Unsuitable due to the need to protect one’s life shall exist to exploit this legal basis | Generally unsuitable due to the need to protect one’s life shall exist to exploit this legal basis |

| Article 6 (1) (e) Performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority | Suitable after adoption of appropriate legislation | Unsuitable due to the disproportional incursions in one’s privacy |

| Article 6 (1) (f) Legitimate interests pursued by the controller or by a third party | Unsuitable—interests and fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject are prevailing | Unsuitable—interests and fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject are prevailing |

| Article 9 (2) (a) Data subject has given explicit consent | Unsuitable due to lack of possibility to identify data subject | Suitable with opt-in study design |

| Article 9 (2) (b) Processing is necessary for carrying out the obligations and exercising specific rights of the controller or of the data subject in the field of employment and social security and social protection law | Unsuitable—study aim outside of the scope | Unsuitable—study aim outside of the scope |

| Article 9 (2) (c) Vital interests of the data subject or of another natural person where the data subject is physically or legally incapable of giving consent | Unsuitable due to the need to protect one’s life shall exist to exploit this legal basis | Generally unsuitable due to the need to protect one’s life shall exist to exploit this legal basis |

| Article 9 (2) (d) Legitimate activities with appropriate safeguards by a foundation, association, or any other not-for-profit body with a political, philosophical, religious, or trade union aim related to the member of such entities | Unsuitable as the whole study population would be required to be members of foundations, associations, etc. | Unsuitable as the whole study population would be required to be members of foundations, associations, etc. |

| Article 9 (2) (e) Personal data are manifestly made public by the data subject | Unsuitable—with publicly available data, the aim of the study cannot be reached | Unsuitable—with publicly available data, the aim of the study cannot be reached |

| Article 9 (2) (f) Establishment, exercise, or defense of legal claims | Unsuitable due to no such legal claims existing | Unsuitable due to no such legal claims existing |

| Article 9 (2) (g) Substantial public interest | (Possibly) suitable, further study with respect to the study aims and design will be required | Unsuitable—the study design aims to identify the individual at risk with possible follow-up |

| Article 9 (2) (h) Preventive or occupational medicine, assessment of the working capacity of the employee, medical diagnosis, provision of health or social care or treatment, or the management of health or social care systems and services on the basis of European Union or member state law or pursuant to contract with a health professional and subject to the conditions and safeguards | Suitable after adoption of the appropriate legislation to support medical diagnosis | Suitable after adoption of the appropriate legislation to support medical diagnosis |

| Article 9 (2) (i) Public interest in the area of public health, such as protecting against serious cross-border threats to health or ensuring high standards of quality and safety of health care and of medicinal products or medical devices | Possibly suitable, further study with respect to the study aims and design will be required | Unsuitable as the aim of the study is to protect individual health |

| Article 9 (2) (j) Archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes, or statistical purposes in accordance with GDPR Article 89 (1) | Possibly suitable in the case of scientific research, further study with respect to the study aims and design will be required Unsuitable with regard to archiving, historical, or statistical purposes. | Unsuitable with regard to archiving, historical, or statistical purposes as the aim of the study is to protect individual health Also unsuitable for scientific research—considering ethical point of view, individual subjects shall consent to participation in research |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kováč, P.; Jackuliak, P.; Bražinová, A.; Varga, I.; Aláč, M.; Smatana, M.; Lovich, D.; Thurzo, A. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Facial Image Analysis for the Early Detection of Rare Diseases: Legal, Ethical, Forensic, and Cybersecurity Considerations. AI 2024, 5, 990-1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai5030049

Kováč P, Jackuliak P, Bražinová A, Varga I, Aláč M, Smatana M, Lovich D, Thurzo A. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Facial Image Analysis for the Early Detection of Rare Diseases: Legal, Ethical, Forensic, and Cybersecurity Considerations. AI. 2024; 5(3):990-1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai5030049

Chicago/Turabian StyleKováč, Peter, Peter Jackuliak, Alexandra Bražinová, Ivan Varga, Michal Aláč, Martin Smatana, Dušan Lovich, and Andrej Thurzo. 2024. "Artificial Intelligence-Driven Facial Image Analysis for the Early Detection of Rare Diseases: Legal, Ethical, Forensic, and Cybersecurity Considerations" AI 5, no. 3: 990-1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai5030049

APA StyleKováč, P., Jackuliak, P., Bražinová, A., Varga, I., Aláč, M., Smatana, M., Lovich, D., & Thurzo, A. (2024). Artificial Intelligence-Driven Facial Image Analysis for the Early Detection of Rare Diseases: Legal, Ethical, Forensic, and Cybersecurity Considerations. AI, 5(3), 990-1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai5030049