Provider Survey on Burn Care in India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient and Public Involvement

2.2. Ethics and Consent

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

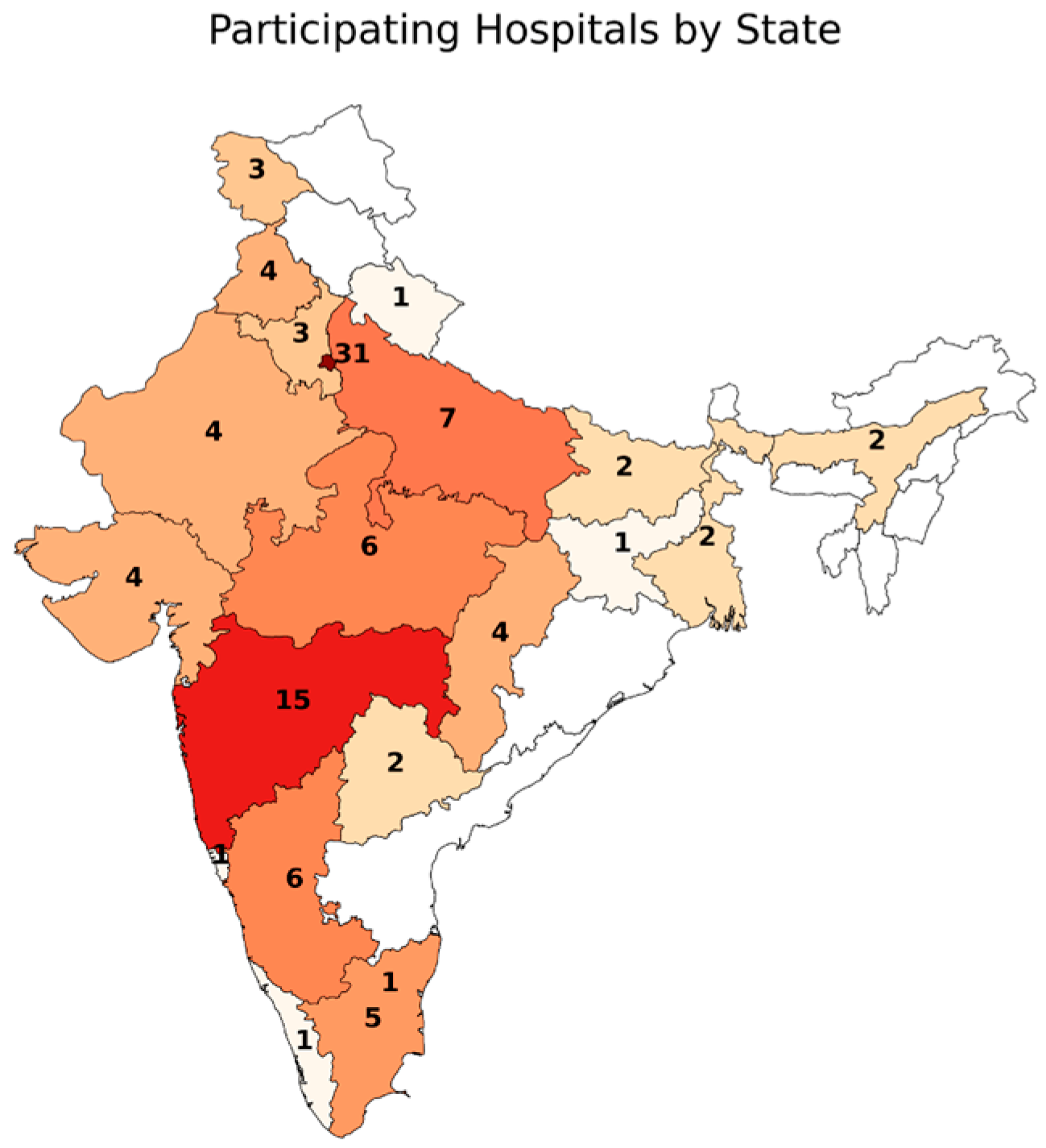

3.1. Origin and Characteristics of the Respondents

3.2. Characteristics of the Healthcare Facility

3.2.1. Type of Hospital and Geographical Access

3.2.2. Funding and Payment

3.2.3. Patient Demographics and Pattern of Injuries

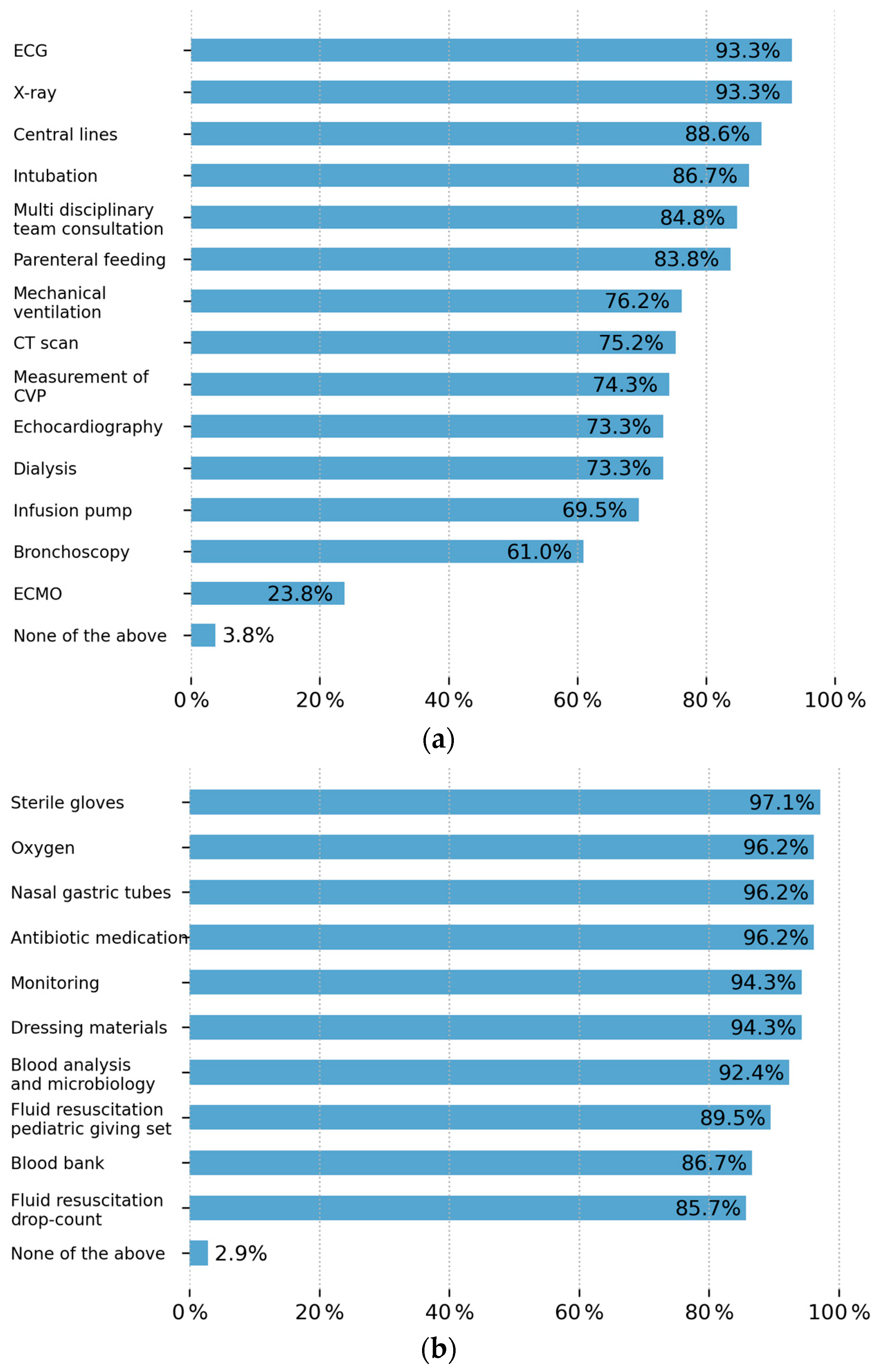

3.2.4. Available Infrastructure

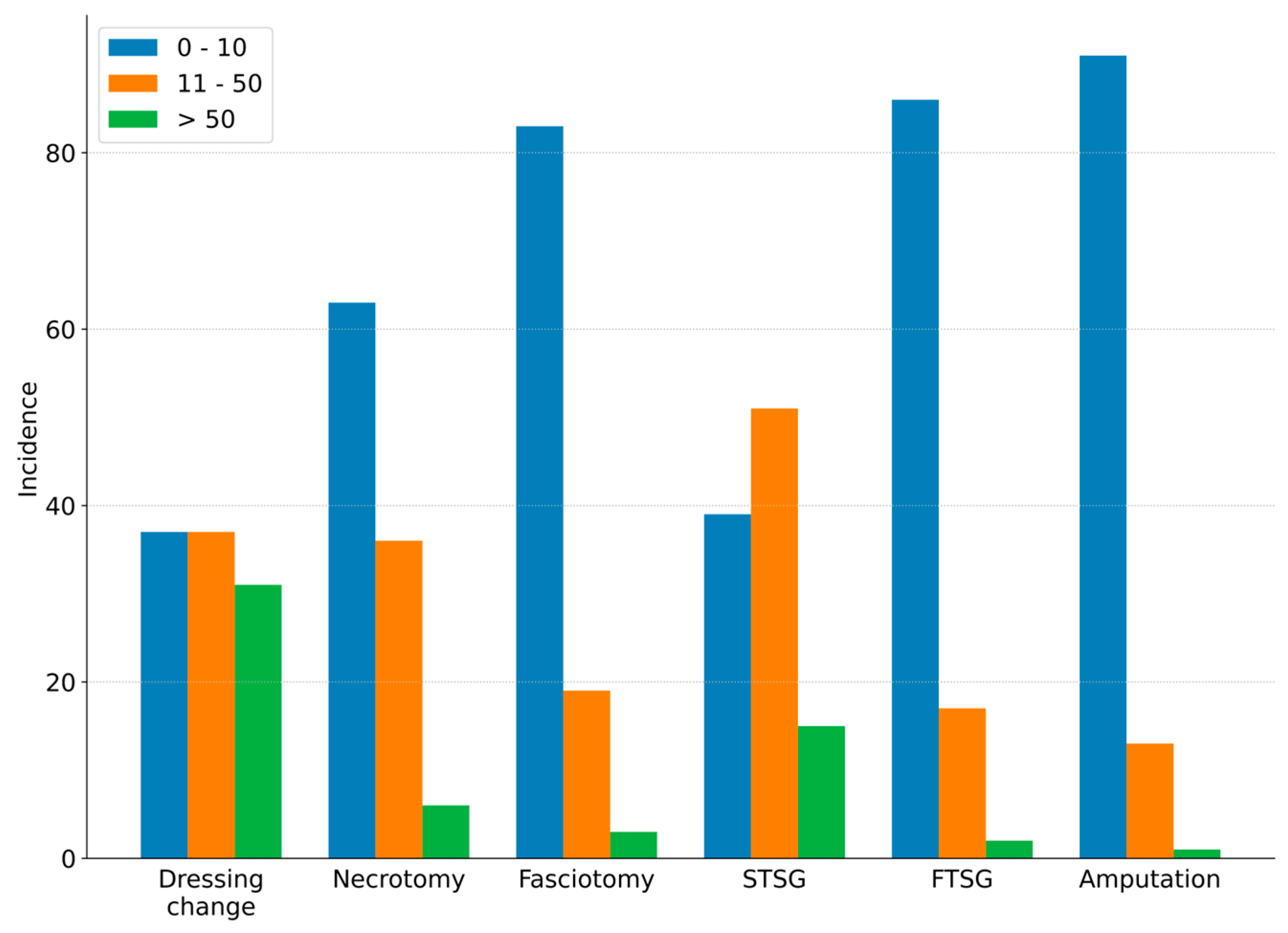

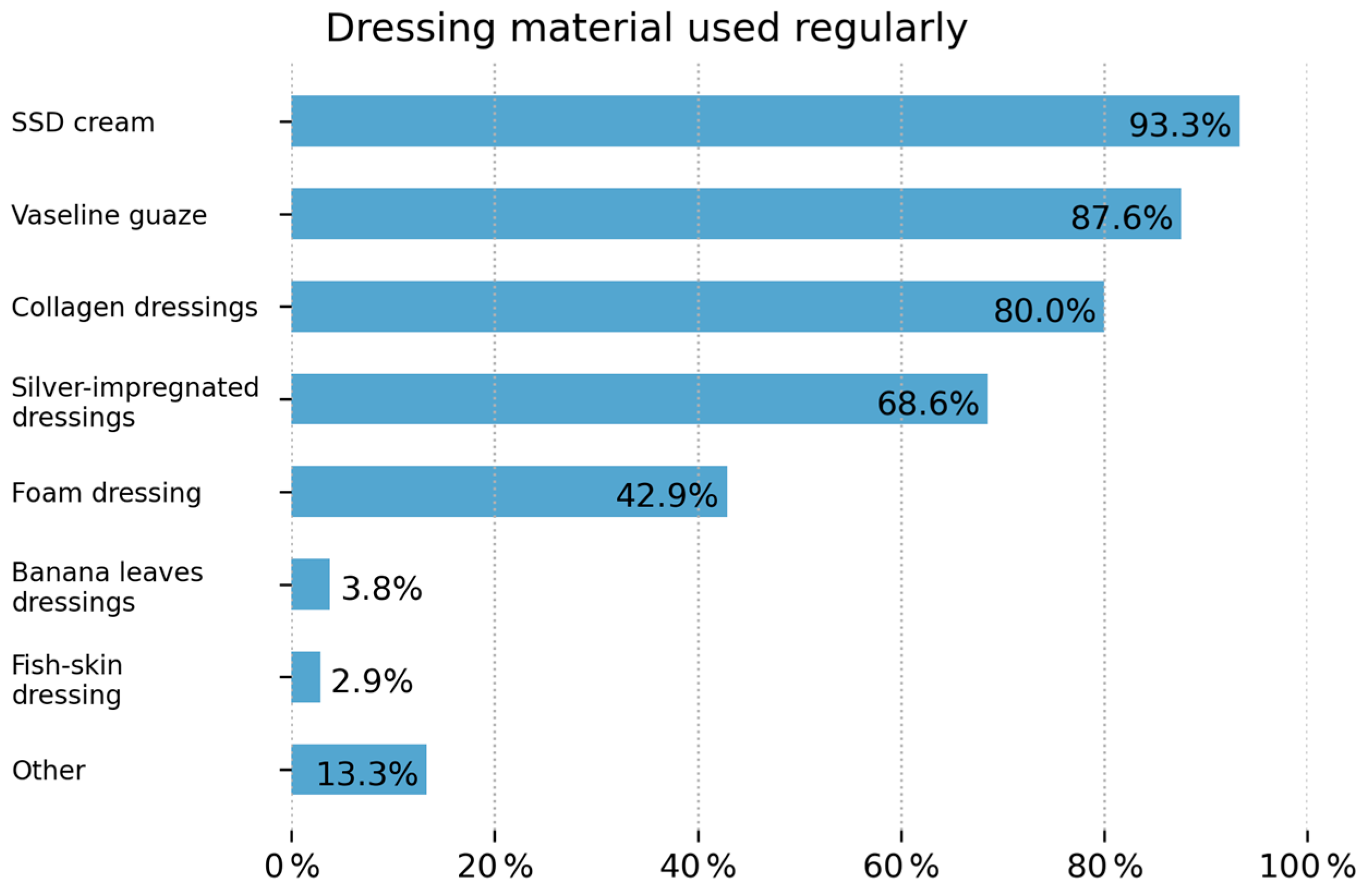

3.2.5. Surgical Care

3.2.6. Potential for Improvement

4. Discussion

4.1. Respondent Characteristics

4.2. Equipment and Out-of-Pocket Payments

4.3. Infrastructure

4.4. Advanced Wound Care

4.5. Skin Grafting

4.6. Outcomes and Opportunities to Improve

5. Conclusions

- Enhanced staff education and training;

- Improved intensive care monitoring;

- Strengthened adherence to infection prevention protocols.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BTM | Biodegradable Temporizing Matrix |

| CVP | Central Venous Pressure |

| DALY | Disability-Adjusted Life Years |

| HIC | High-Income Country |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| LMIC | Low- and Middle-Income Country |

| NPPMRBI | National Programme for Prevention, Management and Rehabilitation of Burn Injuries |

| PIPES | Personnel, Infrastructure, Procedures, Equipment and Supplies-Assessment of Surgery Capacity |

| STSG | Split Thickness Skin Graft |

| TBSA | Total Body Surface Area |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Fact Sheets. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Keshri, V.R.; Abimbola, S.; Parveen, S.; Mishra, B.; Roy, M.P.; Jain, T.; Peden, M.; Jagnoor, J. Navigating health systems for burn care: Patient journeys and delays in Uttar Pradesh, India. Burns 2023, 49, 1745–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, R.; Agrawal, K.; Narayan, R.P.; Tiwari, V.; Prakash, V.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, S. Firecracker injuries during Diwali festival: The epidemiology and impact of legislation in Delhi. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2012, 45, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasor, S.E.; Chung, K.C. Upper Extremity Burns in the Developing World. Hand Clin. 2019, 35, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindert, J.; Bbaale, D.; Mohr, C.; Chamania, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Boettcher, J.; Katabogama, J.B.; Alliance, B.W.; Elrod, J. State of burns management in Africa: Challenges and solutions. Burns 2023, 49, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markin, A.; Barbero, R.; Leow, J.J.; Groen, R.S.; Perlman, G.; Habermann, E.B.; Apelgren, K.N.; Kushner, A.L.; Nwomeh, B.C. Inter-Rater Reliability of the PIPES Tool: Validation of a Surgical Capacity Index for Use in Resource-Limited Settings. World J. Surg. 2014, 38, 2195–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potokar, T.; Bendell, R.; Phuyal, K.; Dhital, A.; Karim, E.; Falder, S.; Kynge, L.; Price, P. The development of the Delivery Assessment Tool (DAT) to facilitate quality improvement in burns services in low-middle income countries. Burns 2022, 48, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhija, L.; Bajaj, S.; Gupta, J. National programme for prevention of burn injuries. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2010, 43, S6–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zodpey, S.; Sharma, A.; Zahiruddin, Q.S.; Gaidhane, A.; Shrikhande, S. Allopathic Doctors in India. J. Health Manag. 2018, 20, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V. Sushruta: The father of surgery. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 8, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meara, J.G.; Leather, A.J.M.; Hagander, L.; Alkire, B.C.; Alonso, N.; Ameh, E.A.; Bickler, S.W.; Conteh, L.; Dare, A.J.; Davies, J.; et al. Global Surgery 2030: Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015, 386, 569–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, T.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; Zadey, S. Measuring timely geographical access to surgical care in India: A geospatial modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghia, C.; Rambhad, G. Implementation of equity and access in Indian healthcare: Current scenario and way forward. J. Mark. Access Health Policy 2023, 11, 2194507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Venkataraman, R.; Bajan, K.; Mehta, Y.; Govil, D.; Ramakrishnan, N.; Zirpe, K.; Sircar, M.; Gurav, S.; Samavedam, S.; et al. Intensive Care in India in 2018–2019: The Second Indian Intensive Care Case Mix and Practice Patterns Study. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 25, 1093–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirupakuzhi Vijayaraghavan, B.K.; Nainan Myatra, S.; Mathew, M.; Lodh, N.; Divatia, J.V.; Hammond, N.; Jha, V.; Venkatesh, B. Challenges in the delivery of critical care in India during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2021, 22, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabu, D.; Gousalya, V.; Rajmohan, M.; Dhamodhar Dinesh, M.; Bharathwaj, V.V.; Sindhu, R.; Sathiyapriya, S. Need Analysis of Indian Critical Health Care Delivery in Government Sectors and Its Impact on the General Public: A Time to Revamp Public Health Care Infrastructure. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 27, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, R.; Vashistha, K.; Saini, C.; Dutt, T.; Raman, D.; Bansal, V.; Singh, H.; Bhandari, G.; Ramakrishnan, N.; Seth, H.; et al. Critical care practice in India: Results of the intensive care unit need assessment survey (ININ2018). World J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 9, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Mittal, A.; Bansal, P.; Singh, S.K. Regulatory approval process for advanced dressings in India: An overview of rules. J. Wound Care 2019, 28, S32–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keswani, S.M.; Mishra, M.G.; Karnik, S.; Dutta, S.; Mishra, M.; Panda, S.; Varghese, R.; Virkar, T.; Upendran, V. Skin banking at a regional burns centre—The way forward. Burns 2018, 44, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, J.L.; Pham, J.; Shen, J.; Stewart, K.; Hoyte-Williams, P.E.; Mehta, K.; Rai, S.; Pedraza, J.M.; Allorto, N.; Pham, T.N.; et al. Lessons Learned From Implementation and Management of Skin Allograft Banking Programs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. J. Burn. Care Res. 2020, 41, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, R.B.; Goswami, P. Cost of providing inpatient burn care in a tertiary, teaching, hospital of North India. Burns 2013, 39, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alok, A. Problem of Poverty in India. Int. J. Res. Rev. 2020, 7, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Josyula, K.L.; Sheikh, K.; Nambiar, D.; Narayan, V.V.; Sathyanarayana, T.; Porter, J.D. “Getting the water-carrier to light the lamps”: Discrepant role perceptions of traditional, complementary, and alternative medical practitioners in government health facilities in India. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 166, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | Number | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delhi | n = 26 | Punjab | n = 4 | Telangana | n = 2 |

| Maharashtra | n = 15 | Rajasthan | n = 4 | West Bengal | n = 2 |

| Kamataka | n = 6 | Jammu and Kashmir | n = 3 | Goa | n = 1 |

| Madhya Pradesh | n = 6 | Haryana | n = 3 | Jharkhand | n = 1 |

| Uttar Pradesh | n = 6 | Tamilnadu | n = 3 | Kerala | n = 1 |

| New Delhi | n = 5 | Assam | n = 2 | Puducherry | n = 1 |

| Chhattisgarh | n = 4 | Bihar | n = 2 | Uttar Pradesh | n = 1 |

| Gujarat | n = 4 | Tamil Nadu | n = 2 | Uttarakhand | n = 1 |

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Profession n= | Specialist Plastic Surgery | 90 | 85.7 |

| Specialist General Surgery | 6 | 5.7 | |

| Student | 3 | 2.8 | |

| Physician Assistant | 1 | 1 | |

| Years of experience treating burn patients | Less than 2 years | 23 | 21.9 |

| 2–5 years | 15 | 14.3 | |

| 6–10 years | 10 | 9.5 | |

| More than 10 years | 57 | 54.3 |

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical payment of treatment for burns (multiple choice) | Patient pays on arrival | 18 | 17.1 |

| Patients pay later | 29 | 27.6 | |

| Free healthcare for all patients | 45 | 42.9 | |

| Free healthcare for small children | 5 | 4.8 | |

| Free healthcare for special groups (other than children) | 12 | 11.4 | |

| Partly free, some basic costs are covered by the families | 27 | 25.7 | |

| Mainly paid by insurance | 7 | 6.7 | |

| If patients need to pay, what they pay for | |||

| Consumables for dressings | 52 | 49.5 | |

| Consumables for surgical interventions (sutures, blades) | 54 | 51.4 | |

| Fee for intervention (surgery, dressing) | 39 | 37.1 | |

| Fee for hospital stay | 49 | 46.6 | |

| Fee for laboratory | 42 | 40.0 | |

| No extra payment | 32 | 30.5 |

| Patient presents late due to previous treatment by traditional healer | n = 81 |

| Patient refuses treatment or leave the hospital early | n = 44 |

| Patient cannot afford treatment (no means for treatment) | n = 41 |

| Overall lack of staff | n = 23 |

| Lack of trained staff | n = 22 |

| Lack of an intensive care unit (defined as constant availability of monitoring, oxygen, fluid management) | n = 15 |

| Lack of dedication of the staff | n = 13 |

| Lack of theater space capacity | n = 12 |

| Lack of dressing material | n = 7 |

| Lack of sedation/anesthesia | n = 5 |

| Lack to perform skin grafting | n = 4 |

| Lack of blood bank | n = 3 |

| Lack of constant power supply | n = 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the European Burns Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bbaale, D.; Nathani, P.; Patel, S.; Mahajan, A.; Chavla, B.; Mohr, C.; Elrod, J.; Chamania, S.; Lindert, J. Provider Survey on Burn Care in India. Eur. Burn J. 2026, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj7010003

Bbaale D, Nathani P, Patel S, Mahajan A, Chavla B, Mohr C, Elrod J, Chamania S, Lindert J. Provider Survey on Burn Care in India. European Burn Journal. 2026; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleBbaale, Dorothy, Priyansh Nathani, Shlok Patel, Anshul Mahajan, Bhavna Chavla, Christoph Mohr, Julia Elrod, Shobha Chamania, and Judith Lindert. 2026. "Provider Survey on Burn Care in India" European Burn Journal 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj7010003

APA StyleBbaale, D., Nathani, P., Patel, S., Mahajan, A., Chavla, B., Mohr, C., Elrod, J., Chamania, S., & Lindert, J. (2026). Provider Survey on Burn Care in India. European Burn Journal, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj7010003