Potential Prognostic Parameters from Patient Medical Files for Inhalation Injury Presence and/or Degree: A Single-Center Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

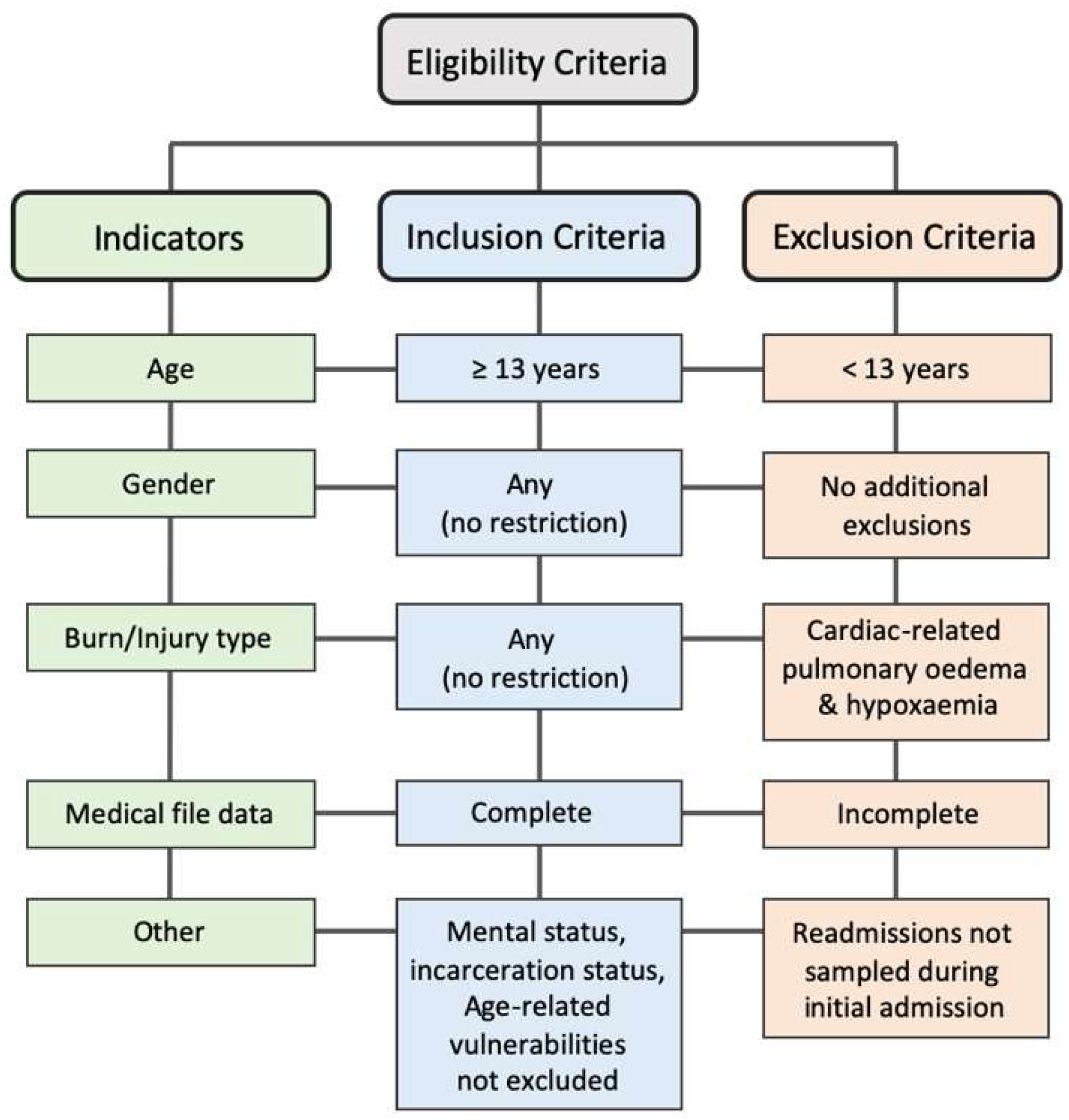

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Data Collection and Sorting

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

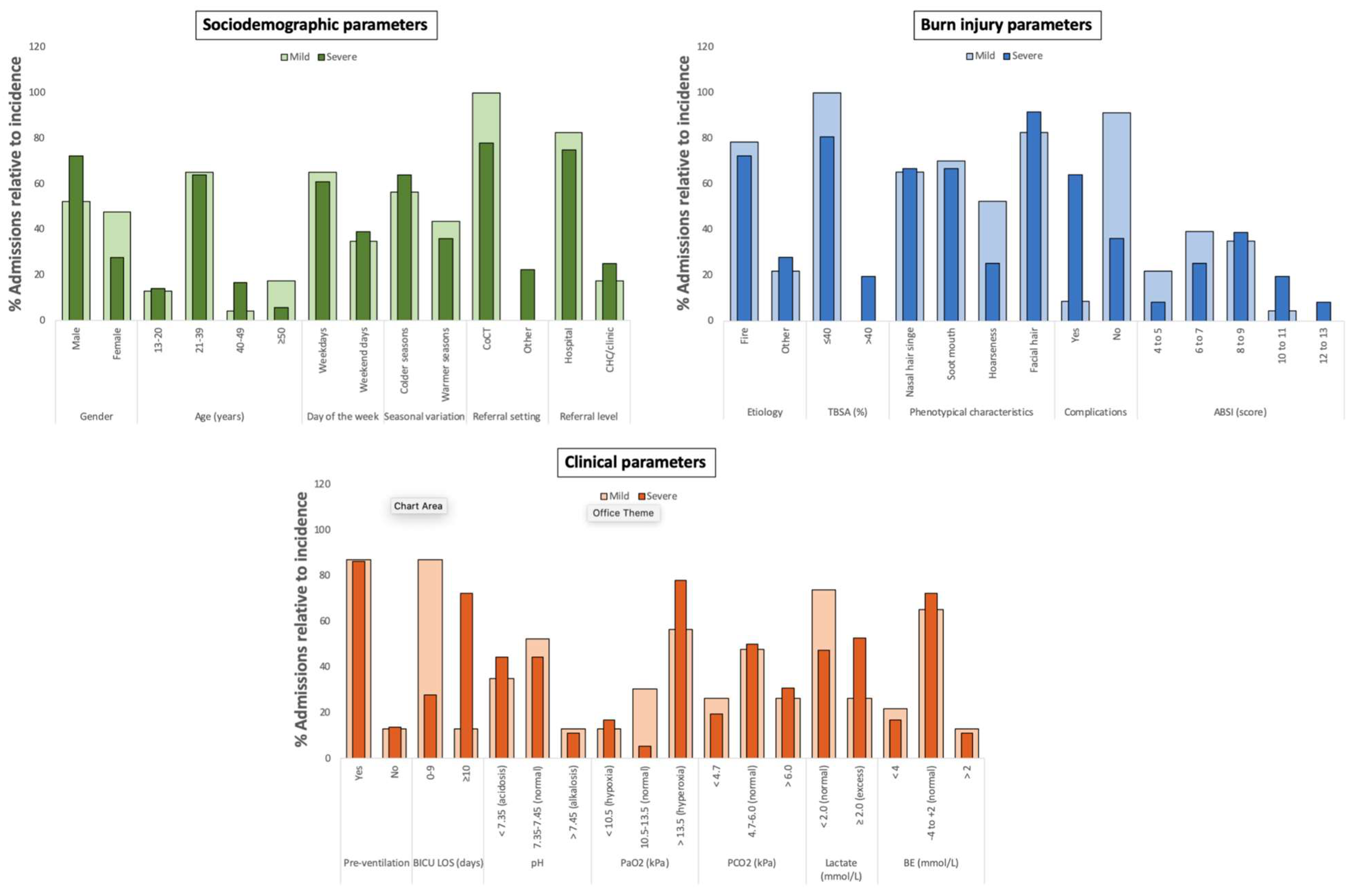

3.1. Sociodemographic, Burn Injury, and Clinical Parameters of Patients with Mild and Severe Inhalation Injury

3.2. Marked Associations with Sociodemographic, Burn Injury, and Clinical Parameters for Inhalation Injury Presence and/or Degree

3.3. Predictive Contribution with Sociodemographic, Burn Injury, and Clinical Parameters for Inhalation Injury Presence and/or Degree

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TBSA | Total body surface area |

| BICU LOS | Burns intensive care unit length of stay |

| VIP | Variable Importance in the Projection |

| WCPATBC | Western Cape Provincial Adult Tertiary Burns Centre |

| TBH | Tygerberg Hospital |

| WC | Western Cape |

| CoCT | City of Cape Town |

| ABSI | Abbreviated Burn Severity Index |

| BICU LOS | Burn Intensive Care Unit Length of Stay |

| ABG | Arterial blood gas |

| BE | Base excess |

References

- Gill, P.; Martin, R.V. Smoke Inhalation Injury. BJA Educ. 2015, 15, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.F.; Buehner, M.F.; Wood, L.A.; Boyer, N.L.; Driscoll, I.R.; Lundy, J.B.; Cancio, L.C.; Chung, K.K. Diagnosis and management of inhalation injury: An updated review. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Peláez, Y.A. Airway Burn or Inhalation Injury: Should All Patients Be Intubated? Colomb. J. Anesthesiol. 2018, 46 (Suppl. S1), 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, R.L. Fire-Related Inhalation Injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dries, D.J.; Endorf, F.W. Inhalation Injury: Epidemiology, Pathology, Treatment Strategies. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2013, 21, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, J.M.; Davis, C.S.; Bird, M.D.; Ramirez, L.; Kim, H.; Burnham, E.L.; Gamelli, R.L.; Kovacs, E.J. The Acute Pulmonary Inflammatory Response to the Graded Severity of Smoke Inhalation Injury. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipovy, B.; Rihová, H.; Gregorova, N.; Hanslianova, M.; Zaloudikova, Z.; Kaloudova, Y.; Brychta, P. Epidemiology of Ventilator-Associated Tracheobronchitis and Vantilator-Associated Pneumonia in Patients with Inhalation Injury at the Burn Centre in Brno (Czech Republic). Ann. Burns Fire Disasters 2011, 24, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- You, K.; Yang, H.-T.; Kym, D.; Yoon, J.; Haejun, Y.; Cho, Y.-S.; Hur, J.; Chun, W.; Kim, J.-H. Inhalation Injury in Burn Patients: Establishing the Link between Diagnosis and Prognosis. Burns 2014, 40, 1470–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, M.J.; Enkhbaatar, P.; Lee, J.O. Inhalation Injury. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2024, 38, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galeiras, R. Smoke inhalation injury: A narrative review. Mediastinum 2021, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S. Pediatric inhalation injury. Burn. Trauma 2017, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foncerrada, G.; Culnan, D.M.; Capek, K.D.; González-Trejo, S.; Cambiaso-Daniel, J.; Woodson, L.C.; Herndon, D.N.; Finnerty, C.C.; Lee, J.O. Inhalation Injury in the Burned Patient. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2018, 80, S98–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masanès, M.-J.; Legendre, C.; Lioret, N.; Saizy, R.; Lebeau, B. Using Bronchoscopy and Biopsy to Diagnose Early Inhalation Injury: Macroscopic and Histologic Findings. Chest 1995, 107, 1365–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-C.; Chen, M.-H.; Wen, B.-S.; Lee, M.-H.; Ma, H. The impact of inhalation injury in patients with small and moderate burns. Burns 2014, 40, 1481–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancio, L.C. Airway Management and Smoke Inhalation Injury in the Burn Patient. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2009, 36, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kym, D.; Hur, J.; Yoon, J.; Yim, H.; Cho, Y.S. Does Inhalation Injury Predict Mortality in Burns Patients or Require Redefinition? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.W.; Williams, F.N.; Cairns, B.A.; Cartotto, R. Inhalation Injury: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2017, 44, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enkhbaatar, P.; Pruitt, B.A., Jr.; Suman, O.; Mlcak, R.; Wolf, S.E.; Sakurai, H.; Herndon, D.N. Pathophysiology, Research Challenges, and Clinical Management of Smoke Inhalation Injury. Lancet 2016, 388, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodson, L.C. Diagnosis and Grading of Inhalation Injury. J. Burn Care Res. 2009, 30, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, N.N.; Hemington-Gorse, S.; Shelley, O.; Philp, B.; Dziewulski, P. Prognostic Scoring Systems in Burns: A Review. Burns 2011, 37, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinn, A.N.; Kemp Bohan, P.M.; Rauschendorfer, C.; Le, T.D.; Rizzo, J.A. Inhalation Injury Severity Score on Admission Predicts Overall Survival in Burn Patients. J. Burn Care Res. 2023, 44, 1273–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Chung, K.; Allen, A.; Batchinsky, A.; Huzar, T.; King, B.; Wolf, S.; Sjulin, T.; Cancio, L. Admission Chest CT Complements Fiberoptic Bronchoscopy in Prediction of Adverse Outcomes in Thermally Injured Patients. J. Burn Care Res. 2012, 33, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissin, C.; Wallis, L.A.; Kleintjes, W.; Laflamme, L. Admission Factors Associated with the In-Hospital Mortality of Burns Patients in Resource-Constrained Settings: A Two-Year Retrospective Investigation in a South African Adult Burns Centre. Burns 2019, 45, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloake, T.; Haigh, T.; Cheshire, J.; Walker, D. The Impact of Patient Demographics and Comorbidities upon Burns Admitted to Tygerberg Hospital Burns Unit, Western Cape, South Africa. Burns 2017, 43, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritz, D.; Wallis, L.; Van Der Merwe, E.; Nel, D. The Aetiology of Adult Burns in the Western Cape, South Africa. Burns 2012, 38, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Wellness. Tygerberg Hospital: Overview. Western Cape Government. Available online: https://d7.westerncape.gov.za/your_gov/153#:~:text=Tygerberg%20Hospital%20is%20a%20tertiary,of%20Stellenbosch’s%20Health%20Science%20Faculty.&text=To%20provide%20affordable%20world%20class,excellent%20educational%20and%20research%20opportunities.&text=To%20be%20the%20best%20academic,Out%2DPatients%20Department%20Contact%20List (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Matzopoulos, R. A Profile of Fatal Injuries in South Africa: Fifth Annual Report of the National Injury Mortality Surveillance System, 2003. Medical Research Council-University of South Africa Crime, Violence and Lead Programme. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?&title=A%20Profile%20of%20Fatal%20Injuries%20in%20South%20Africa%3A%206th%20Annual%20Report%20of%20the%20National%20Injury%20Mortality%20Surveillance%20System%2C%202004&publication_year=2005&author=Matzopoulos%2CR#:~:text=A%20profile%20of%20fatal%20injuries%20in%20South%20Africa%3A%20Fifth%20Annual%20Report%20of%20the%20National%20Injury%20Mortality%20Surveillance%20System%2C%202003 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Western Cape Government. Tygerberg Hospital’s Specialised Burn Centre a Beacon of Hope for Burns Victims. 2023. Available online: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/health-wellness/article/tygerberg-hospitals-specialised-burn-centre-beacon-hope-burns-victims?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Carolissen, S.; Kleintjes, W.; Gool, F.; Gilbert, S. Outcomes of complex burn injury patients managed at two primary and one tertiary level burns facilities in the Western Cape province of South Africa—A retrospective review. S. Afr. J. Surg. 2023, 61, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parbhoo, A.; Louw, Q.A.; Grimmer-Somers, K.A. Profile of hospital-admitted paediatric burns patients in South Africa. BMC Res. Notes 2010, 3, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- South African Government. Government Gazette. No. 4 of 2013: Protection of Personal Information Act; South African Government: Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/3706726-11act4of2013popi.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Tobiasen, J.; Hiebert, J.M.; Edlich, R.F. The Abbreviated Burn Severity Index. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1982, 11, 260–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancey, C.P.; Reidy, J. Statistics Without Maths for Psychology; Pearson Education/Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wold, H. Partial Least Squares. In Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences; Kotz, S., Johnson, N.L., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 581–591. [Google Scholar]

- Ramabulana, A.-T.; Steenkamp, P.A.; Madala, N.E.; Dubery, I.A. Profiling of Altered Metabolomic States in Bidens Pilosa Leaves in Response to Treatment by Methyl Jasmonate and Methyl Salicylate. Plants 2020, 9, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarachantachote, N.; Chadcham, S.; Saithanu, K. Cutoff Threshold of Variable Importance in Projection for Variable Selection. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2014, 94, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, C.; Albrecht, K.A.; Sonke, C.C.; Azad, S. Approach to Burn Treatment in the Rural Emergency Department. Can. Fam. Physician 2024, 70, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancio, L.C.; Barillo, D.J.; Kearns, R.D.; Holmes, J.H.; Conlon, K.M.; Matherly, A.F.; Cairns, B.A.; Hickerson, W.L.; Palmieri, T. Guidelines for Burn Care Under Austere Conditions. J. Burn Care Res. 2017, 38, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, S.; Osuka, A.; Kuroki, Y.; Ueyama, M. Indications of Early Intubation for Patients with Inhalation Injury. Acute Med. Surg. 2017, 4, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, G.; Watson, P.; Maughan, R.J.; Shirreffs, S.M.; Nevill, A.M. A Spurious Correlation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004, 97, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K. Mathematical Contributions to the Theory of Evolution—On a Form of Spurious Correlation Which May Arise When Indices Are Used in the Measurement of Organs. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1897, 60, 489–498. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Statistics Notes: Correlation, Regression, and Repeated Data. BMJ 1994, 308, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.-Y.; Chen, S.-J.; Hsiao, Y.-C.; Kuo, L.-W.; Liao, C.-H.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Bajani, F.; Fu, C.-Y. Positive Signs on Physical Examination Are Not Always Indications for Endotracheal Tube Intubation in Patients with Facial Burn. BMC Emerg. Med. 2022, 22, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, D.; Silva, I.; Egipto, P.; Magalhães, A.; Filipe, R.; Silva, A.; Rodrigues, A.; Costa, J. Inhalation Injury in a Burn Unit: A Retrospective Review of Prognostic Factors. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2017, 30, 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Elrod, J.; Mohr, C.; Wolff, R.; Boettcher, M.; Reinshagen, K.; Bartels, P.; Registry, G.B.; Koenigs, I. Using Artificial Intelligence to Obtain More Evidence? Prediction of Length of Hospitalization in Pediatric Burn Patients. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 8, 613736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.C.B.T.; de Aguiar Júnior, W.; Whitaker, I.Y. The association between burn and trauma severity and in-hospital complications. Burns 2020, 46, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockly, O.R.; Wolfe, A.E.; Carrougher, G.J.; Stewart, B.T.; Gibran, N.S.; Wolf, S.E.; McMullen, K.; Bamer, A.M.; Kowalske, K.; Cioffi, W.G.; et al. Inhalation injury is associated with long-term employment outcomes in the burn population: Findings from a cross-sectional examination of the Burn Model System National Database. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.J.; Kok, Y.O.; Tay, R.X.Y.; Ramesh, D.S.; Tan, K.C.; Tan, B.K. Quantifying the Impact of Inhalational Burns: A Prospective Study. Burn. Trauma 2018, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.W.; Zhou, H.; Ortiz-Pujols, S.M.; Maile, R.; Herbst, M.; Joyner, B.L., Jr.; Zhang, H.; Kesic, M.; Jaspers, I.; Short, K.A.; et al. Bronchoscopy-Derived Correlates of Lung Injury Following Inhalational Injuries: A Prospective Observational Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, M.; Burnham, E.L.; Joyce, C.; Gagnon, R.; Dunn, R.; Albright, J.M.; Ramirez, L.; Repine, J.E.; Netzer, G.; Kovacs, E.J. Injury Characteristics and von Willebrand Factor for the Prediction of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Patients with Burn Injury. Ann. Surg. 2019, 270, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, E.; Sheridan, R. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Mechanical Ventilation, and Inhalation Injury in Burn Patients. Surg. Clin. 2023, 103, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.; Garcia, L.; Oliveira, B.; Tanita, M.; Festti, J.; Cardoso, L.; Lavado, L.; Grion, C. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Burn Patients: Incidence and Risk Factor Analysis. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2016, 29, 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, N.N.; Hung, T.D. ARDS among Cutaneous Burn Patients Combined with Inhalation Injury: Early Onset and Bad Outcome. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2019, 32, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, H.; Malgerud, E.; Asmussen, S.; Lopez, E.; Salzman, A.L.; Enkhbaatar, P. R-100 improves pulmonary function and systemic fluid balance in sheep with combined smoke-inhalation injury and Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, M.; Hamahata, A.; Traber, D.L.; Esechie, A.; Jonkam, C.; Bansal, K.; Nakano, Y.; Traber, L.D.; Enkhbaatar, P. A murine model of sepsis following smoke inhalation injury. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 391, 1555–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, S.; Pellegrini, E.; Green-Saxena, A.; Summers, C.; Hoffman, J.; Calvert, J.; Das, R. Supervised Machine Learning for the Early Prediction of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). J. Crit. Care 2020, 60, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trillo-Alvarez, C.; Cartin-Ceba, R.; Kor, D.J.; Kojicic, M.; Kashyap, R.; Thakur, S.; Thakur, L.; Herasevich, V.; Malinchoc, M.; Gajic, O. Acute Lung Injury Prediction Score: Derivation and Validation in a Population-Based Sample. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 37, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshrefi, S.; Sheckter, C.C.; Shepard, K.; Pereira, C.; Davis, D.J.; Karanas, Y.; Rochlin, D.H. Preventing Unnecessary Intubations: A 5-Year Regional Burn Center Experience Using Flexible Fiberoptic Laryngoscopy for Airway Evaluation in Patients with Suspected Inhalation or Airway Injury. J. Burn Care Res. 2019, 40, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, K. Mechanical Ventilation. JAMA 2021, 326, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss, R.S.; Moldawer, L.L.; Opal, S.M.; Reinhart, K.; Turnbull, I.R.; Vincent, J.-L. Sepsis and Septic Shock. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016, 2, 16045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshiakh, S.M. Role of Serum Lactate as Prognostic Marker of Mortality among Emergency Department Patients with Multiple Conditions: A Systematic Review. SAGE Open Med. 2023, 11, 20503121221136401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godinjak, A.; Jusufovic, S.; Rama, A.; Iglica, A.; Zvizdic, F.; Kukuljac, A.; Tancica, I.; Rozajac, S. Hyperlactatemia and the Importance of Repeated Lactate Measurements in Critically Ill Patients. Med. Arch. 2017, 71, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthukumar, V.; Arumugam, P.K.; Narasimhan, A.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, U.; Sharma, S.; Kain, R. Blood Lactate and Lactate Clearance: Refined Biomarker and Prognostic Marker in Burn Resuscitation. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2020, 33, 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.J.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, T.Y.; Kang, C.; Lee, S.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Lee, S.B.; Lim, D. Serum Lactate upon Emergency Department Arrival as a Predictor of 30-Day in-Hospital Mortality in an Unselected Population. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.C.; Sohn, H.A.; Park, Z.-Y.; Oh, S.; Kang, Y.K.; Lee, K.M.; Kang, M.; Jang, Y.J.; Yang, S.J.; Hong, Y.K.; et al. A Lactate-Induced Response to Hypoxia. Cell 2015, 161, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, F.J.; Haidar, M.K.; Jouffroy, R.; Raphalen, J.-H.; Lamhaut, L.; Carli, P. Determinants of Lactic Acidosis in Acute Cyanide Poisonings. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, e523–e529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gicheru, B.; Shah, J.; Wachira, B.; Omuse, G.; Maina, D. The Diagnostic Accuracy of an Initial Point-of-Care Lactate at the Emergency Department as a Predictor of in-Hospital Mortality among Adult Patients with Sepsis and Septic Shock. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1173286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokline, A.; Abdenneji, A.; Rahmani, I.; Gharsallah, L.; Tlaili, S.; Harzallah, I.; Gasri, B.; Hamouda, R.; Messadi, A.A. Lactate: Prognostic Biomarker in Severely Burned Patients. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2017, 30, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo, S.M.; Kim, W.Y. Clinical Applications of Lactate Testing in Patients with Sepsis and Septic Shock. J. Emerg. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G.A. Cell–Cell and Intracellular Lactate Shuttles. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 5591–5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G.A. Lactate Shuttles in Nature. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002, 30, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.N.; Amin, M.A.; ElHalim, M.M.A.; Nawar, K.I.K. Evaluation of Blood Lactate Concentrations as a Marker for Resuscitation and Prognosis in Patients with Major Burns. QJM Int. J. Med. 2023, 116 (Suppl. S1), hcad069.688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero De Lucas, E.; Sanchez-Sanchez, M.; Cachafeiro Fuciños, L.; Agrifoglio Rotaeche, A.; Martínez Mendez, J.R.; Flores Cabeza, E.; Millan Estañ, P.; García-de-Lorenzo, A. Lactate and Lactate Clearance in Critically Burned Patients: Usefulness and Limitations as a Resuscitation Guide and as a Prognostic Factor. Burns 2020, 46, 1839–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamolz, L.-P.; Andel, H.; Schramm, W.; Meissl, G.; Herndon, D.N.; Frey, M. Lactate: Early predictor of morbidity and mortality in patients with severe burns. Burns 2005, 31, 986–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mild | Severe | |

|---|---|---|

| Central indices (Mean, 95% CI) | 2.7 (2.3–3.4) | 11.2 (9.5–12.9) |

| Total admissions (n = 59) | 23 | 36 |

| % mortality relative to admissions | 4.3 | 38.9 |

| Mortality (n = 15) | 1 | 14 |

| % mortality relative to mortality incidences | 6.7 | 93.3 |

| Study Variables | Fisher’s p-Value | Correlation Coefficient (rho) | rho p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||

| Gender (male/female) | 0.350 | −0.049 | 0.712 | −0.308 to 0.217 |

| Age (years) | 0.080 | 0.095 | 0.474 | −0.173 to 0.350 |

| Day of the week (week/weekend days) | 0.379 | −0.006 | 0.963 | −0.269 to 0.258 |

| Seasonal variation (colder/warmer) | 0.421 | −0.013 | 0.920 | −0.276 to 0.251 |

| Referral setting (CoCT/other districts) | 0.161 | 0.151 | 0.252 | −0.117 to 0.399 |

| Referral Level (hospitals or CHC/clinics) | 0.082 | 0.107 | 0.419 | −0.161 to 0.360 |

| Days between injury & admission (days) | 0.311 | −0.109 | 0.409 | −0.289 to 0.238 |

| Injury characteristics | ||||

| Etiology (fire/other sources) | 0.351 | 0.118 | 0.373 | −0.150 to 0.370 |

| TBSA (%) | 0.008* | 0.357 | 0.006 ** | 0.103–0.567 |

| Singed nasal hairs (yes/no) | 0.472 | 0.068 | 0.611 | −0.199 to 0.325 |

| Soot around/in mouth (yes/no) | 0.908 | 0.046 | 0.730 | −0.220 to 0.306 |

| Hoarseness (yes/no) | 0.178 | −0.314 | 0.015* | −0.533 to 0.055 |

| Facial burns (yes/no) | 0.750 | 0.091 | 0.492 | −0.176 to 0.346 |

| Complications (yes/no) | <0.001 * | 0.690 | <0.000 ** | 0.522–0.807 |

| ABSI scores (4−13 points range) | 0.163 | 0.347 | 0.007 ** | 0.093–0.560 |

| Clinical parameters | ||||

| BICU LOS (days) | <0.001 * | 0.908 | <0.001 ** | 0.847–0.945 |

| Ventilation prior to admission (yes/no) | 0.267 | 0.019 | 0.887 | −0.246 to 0.281 |

| pH | 0.936 | −0.223 | 0.090 | −0.399 to 0.116 |

| PaO2 (kPa) | 0.381 | 0.006 | 0.964 | −0.258 to 0.269 |

| PCO2 (kPa) | 0.955 | −0.089 | 0.503 | −0.179 to 0.344 |

| Sats (%) | 0.626 | 0.200 | 0.129 | −0.067 to 0.440 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 0.060 | 0.331 | 0.011 * | 0.074 to 0.556 |

| Base excess (mmol/L) | 0.936 | −0.040 | 0.763 | −0.300 to 0.226 |

| Predicted variances of latent factors for inhalation injury presence | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| X-variance | 0.509 | 0.216 | 0.087 | 0.188 |

| Y-variance | 0.729 | 0.082 | 0.008 | 0.000 |

| Adjusted R-square (R2) | 0.725 | 0.805 | 0.809 | 0.806 |

| VIP values per variable for inhalation injury presence prediction | ||||

| Complications | 1.117 | 1.064 | 1.070 | 1.070 |

| %TBSA | 0.487 | 0.606 | 0.609 | 0.609 |

| BICU LOS | 1.495 | 1.491 | 1.487 | 1.487 |

| Lactate | 0.527 | 0.544 | 0.542 | 0.543 |

| Predicted variances of latent factor 1 for inhalation injury presence and severe degree | ||

| Inhalation injury presence | Severe inhalation injury | |

| X-variance | 0.490 | 0.492 |

| Y-variance | 0.604 | 0.401 |

| Adjusted R-square (R2) | 0.597 | 0.390 |

| VIP values per variable sub-groups for injury presence and severe degree prediction | ||

| Complications (present) | 1.229 | 1.229 |

| %TBSA (>40 days) | 0.590 | 0.662 |

| BICU LOS (≥10 days) | 1.372 | 1.303 |

| Lactate (Excess) | 0.509 | 0.594 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the European Burns Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Prinsloo, T.K.; Kleintjes, W.G.; Najaar, K. Potential Prognostic Parameters from Patient Medical Files for Inhalation Injury Presence and/or Degree: A Single-Center Study. Eur. Burn J. 2026, 7, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj7010002

Prinsloo TK, Kleintjes WG, Najaar K. Potential Prognostic Parameters from Patient Medical Files for Inhalation Injury Presence and/or Degree: A Single-Center Study. European Burn Journal. 2026; 7(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj7010002

Chicago/Turabian StylePrinsloo, Tarryn Kay, Wayne George Kleintjes, and Kareemah Najaar. 2026. "Potential Prognostic Parameters from Patient Medical Files for Inhalation Injury Presence and/or Degree: A Single-Center Study" European Burn Journal 7, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj7010002

APA StylePrinsloo, T. K., Kleintjes, W. G., & Najaar, K. (2026). Potential Prognostic Parameters from Patient Medical Files for Inhalation Injury Presence and/or Degree: A Single-Center Study. European Burn Journal, 7(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj7010002