Effects of Dispositional Mindfulness and Mindfulness-Based Interventions on the Psychosocial Consequences of Burn Injuries: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

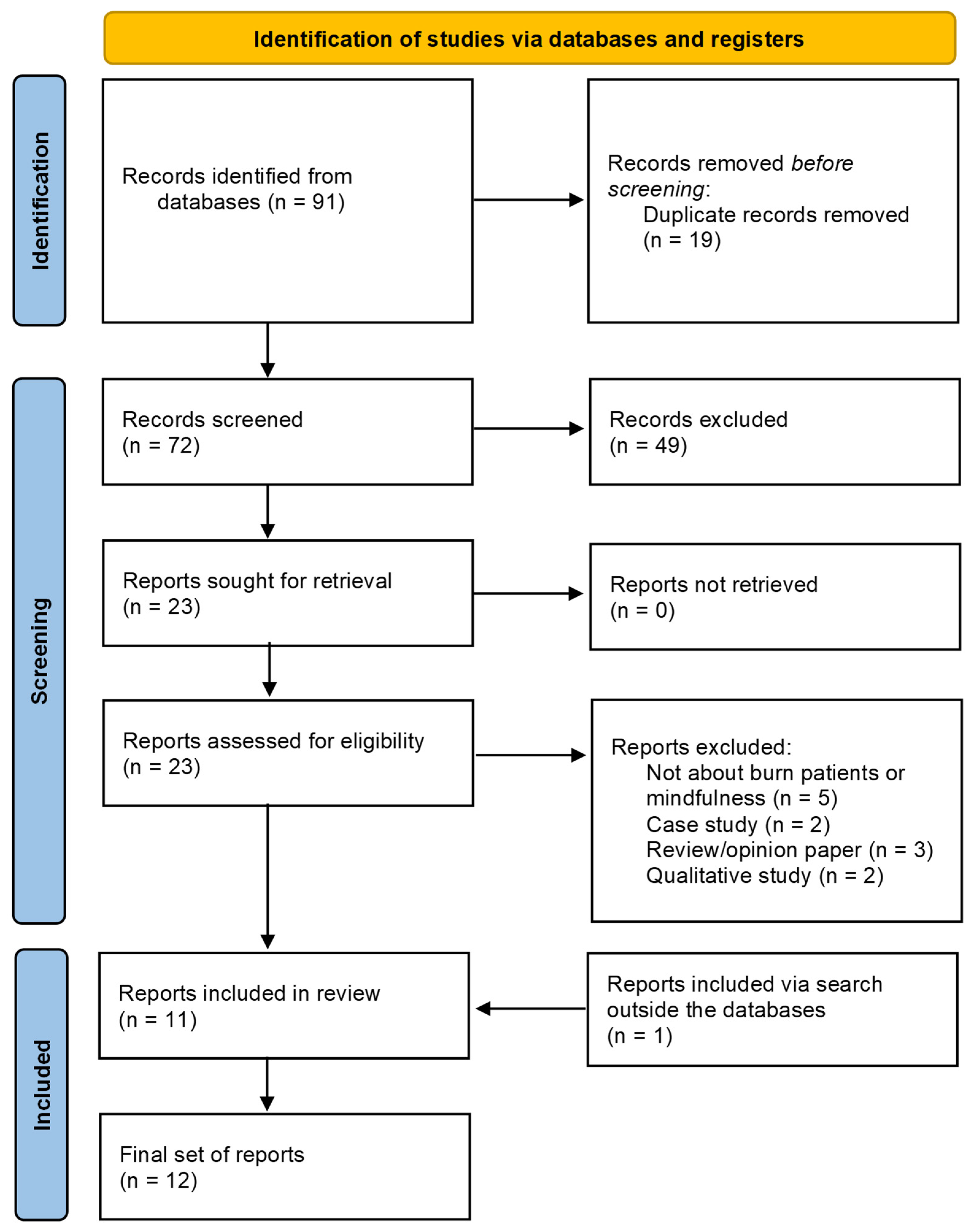

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Cross-Sectional Studies

3.2. Mindfulness Interventions

3.3. Yoga Interventions

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Loey, N.E.E.; Van Son, M.J.M. Psychopathology and Psychological Problems in Patients with Burn Scars. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2003, 4, 245–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare-Kaseb, A.; Hajialibeigloo, R.; Dadkhah-Tehrani, M.; Otaghsara, S.M.T.; Zeydi, A.E.; Ghazanfari, M.J. Role of Mindfulness in Improving Psychological Well-Being of Burn Survivors. Burns 2023, 49, 984–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latarjet, J.; Choinère, M. Pain in Burn Patients. Burns 1995, 21, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, E.E.; Griffiths, T.A. Psychological Consequences of Burn Injury. Burns 1991, 17, 478–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodha, P.; Shah, B.; Karia, S.; De Sousa, A. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (Ptsd) Following Burn Injuries: A Comprehensive Clinical Review. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2020, 33, 276. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, D.R.; Everett, J.J.; Bombardier, C.H.; Questad, K.A.; Lee, V.K.; Marvin, J.A. Psychological Effects of Severe Burn Injuries. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKibben, J.B.A.; Bresnick, M.G.; Wiechman Askay, S.A.; Fauerbach, J.A. Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Prospective Study of Prevalence, Course, and Predictors in a Sample With Major Burn Injuries. J. Burn. Care Res. 2008, 29, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thombs, B.D.; Bresnick, M.G.; Magyar-Russell, G. Depression in Survivors of Burn Injury: A Systematic Review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2006, 28, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, S.; Arslan, S. Pain and Anxiety in Burn Patients. Int. J. Caring 2017, 10, 1723. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, M.; Khadilkar, N.; De Sousa, A. Burn-Related Factors Affecting Anxiety, Depression and Self-Esteem in Burn Patients: An Exploratory Study. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2017, 30, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Spronk, I.; Legemate, C.M.; Dokter, J.; van Loey, N.E.E.; van Baar, M.E.; Polinder, S. Predictors of Health-Related Quality of Life after Burn Injuries: A Systematic Review. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohrtman, E.A.; Shapiro, G.D.; Simko, L.C.; Dore, E.; Slavin, M.D.; Saret, C.; Amaya, F.; Lomelin-Gascon, J.; Ni, P.; Acton, A.; et al. Social Interactions and Social Activities After Burn Injury: A Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation (LIBRE) Study. J. Burn. Care Res. 2018, 39, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, E.; Crijns, T.J.; Ring, D.; Coopwood, B. Social Factors and Injury Characteristics Associated with the Development of Perceived Injury Stigma among Burn Survivors. Burns 2021, 47, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, L.; Rosenberg, M.; Rimmer, R.B.; Fauerbach, J.A. Psychosocial Recovery and Reintegration of Patients With Burn Injuries. In Total Burn Care, 5th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 709–720.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayuo, J.; Wong, F.K.Y. Issues and Concerns of Family Members of Burn Patients: A Scoping Review. Burns 2021, 47, 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.F.; Perry, S.W.; Kulchycky, S.; Goodwin, C. Stress and Coping in Relatives of Burn Patients: A Longitudinal Study. Psychiatr. Serv. 2006, 39, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landolt, M.A.; Grubenmann, S.; Meuli, M. Family Impact Greatest: Predictors of Quality of Life and Psychological Adjustment in Pediatric Burn Survivors. J. Trauma—Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2002, 53, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeney, P.E.; Rosenberg, L.; Rosenberg, M.; Faber, A.W. Psychosocial Care of Persons with Severe Burns. Burns 2008, 34, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisely, J.A.; Hoyle, E.; Tarrier, N.; Edwards, J. Where to Start?: Attempting to Meet the Psychological Needs of Burned Patients. Burns 2007, 33, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J.E.; Lanius, R.A.; McKinnon, M.C. Mindfulness-Based Treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Review of the Treatment Literature and Neurobiological Evidence. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2018, 43, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, L.; Hempel, S.; Ewing, B.A.; Apaydin, E.; Xenakis, L.; Newberry, S.; Colaiaco, B.; Maher, A.R.; Shanman, R.M.; Sorbero, M.E.; et al. Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Strauss, C.; Bond, R.; Cavanagh, K. How Do Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Improve Mental Health and Wellbeing? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Mediation Studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wang, T.-Y. Mindfulness-Based Interventions in the Light of Burns. Burns 2024, 50, 1711–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Segal, Z.V.; Abbey, S.; Speca, M.; Velting, D.; et al. Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2004, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlmeijer, E.; Prenger, R.; Taal, E.; Cuijpers, P. The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Therapy on Mental Health of Adults with a Chronic Medical Disease: A Meta-Analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 68, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, E.K.; Creswell, J.D. Mechanisms of Mindfulness Training: Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 51, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simione, L.; Saldarini, F. A Critical Review of the Monitor and Acceptance Theory of Mindfulness. Mindfulness 2023, 14, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, E.K.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness, Acceptance, and Emotion Regulation: Perspectives from Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluth, K.; Kiken, L.G.; Palsson, O.S.; Gaylord, S.A.; Garland, E.L. From a State to a Trait: Trajectories of State Mindfulness in Meditation during Intervention Predict Changes in Trait Mindfulness. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2015, 81, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.L.; Fredrickson, B.L. Positive Psychological States in the Arc from Mindfulness to Self-Transcendence: Extensions of the Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory and Applications to Addiction and Chronic Pain Treatment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. Self-Compassion: Theory, Method, Research, and Intervention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluth, K.; Neff, K.D. New Frontiers in Understanding the Benefits of Self-Compassion. Self Identity 2018, 17, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, M.C.; Thompson, D.R.; Ski, C.F. Yoga, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Stress-Related Physiological Measures: A Meta-Analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 86, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, H.; Lauche, R.; Anheyer, D.; Pilkington, K.; de Manincor, M.; Dobos, G.; Ward, L. Yoga for Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 830–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness; Delta Trade Paperbacks: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Z.V.; Williams, J.M.G.; Teasdale, J.D. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781462537037. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, B.; Lindsay, E.K.; Greco, C.M.; Brown, K.W.; Smyth, J.M.; Wright, A.G.C.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness Interventions Improve Momentary and Trait Measures of Attentional Control: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2021, 150, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, A. The Difficulty of Defining Mindfulness: Current Thought and Critical Issues. Mindfulness 2013, 4, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, A.; Serretti, A. A Systematic Review of Neurobiological and Clinical Features of Mindfulness Meditations. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1239–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veehof, M.M.; Trompetter, H.R.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; Schreurs, K.M.G. Acceptance- and Mindfulness-Based Interventions for the Treatment of Chronic Pain: A Meta-Analytic Review. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2016, 45, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolardi, V.; Simione, L.; Scaringi, D.; Malinowski, P.; Yordanova, J.; Kolev, V.; Mauro, F.; Giommi, F.; Barendregt, H.P.; Aglioti, S.M.; et al. The Two Arrows of Pain: Mechanisms of Pain Related to Meditation and Mental States of Aversion and Identification. Mindfulness 2022, 15, 753–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, A.R.; Abbott, M.J.; Norberg, M.M.; Hunt, C. A Systematic Review of Mindfulness and Acceptance-Based Treatments for Social Anxiety Disorder. J. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 71, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, E.K.; Young, S.; Brown, K.W.; Smyth, J.M.; Creswell, J.D. Mindfulness Training Reduces Loneliness and Increases Social Contact in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3488–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yi, P.; Ma, L.; Liu, W.; Deng, W.; Yang, X.; Liang, M.; Luo, J.; Li, N.; Li, X. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Social Anxiety Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 300, 113935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Waltz, T.; Zettle, R.D. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Lykins, E.; Button, D.; Krietemeyer, J.; Sauer, S.; Walsh, E.; Duggan, D.; Williams, J.M.G. Construct Validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in Meditating and Nonmeditating Samples. Assessment 2008, 15, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, L.; Centifanti, L.C.M.; Holman, N.; Taylor, P. Parental Adjustment Following Pediatric Burn Injury: The Role of Guilt, Shame, and Self-Compassion. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2019, 44, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghabeesh, S.H.; Mahmoud, M.M. Mindfulness and Its Positive Effect on Quality of Life among Chronic Burn Survivors: A Descriptive Correlational Study. Burns 2022, 48, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghabeesh, S.H. Coping Strategies, Social Support, and Mindfulness Improve the Psychological Well-Being of Jordanian Burn Survivors: A Descriptive Correlational Study. Burns 2022, 48, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghabeesh, S.H.; Mahmoud, M.; Rayan, A.; Alnaeem, M.; Algunmeeyn, A. Mindfulness, Social Support, and Psychological Distress Among Jordanian Burn Patients. J. Burn. Care Res. 2024, 45, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, L.; Reynolds, D.P.; Turner, A.; O’Boyle, C.P.; Thompson, A.R. The Role of Psychological Flexibility in Appearance Anxiety in People Who Have Experienced a Visible Burn Injury. Burns 2019, 45, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, L.; Sirois, F.M.; Harcourt, D.; Norman, P.; Aaron, D.; Adkins, K.; Cartwright, A.; Hodgkinson, E.; Murphy, N.; Thompson, A.R. A Multi-Centre Prospective Cohort Study Investigating the Roles of Psychological Flexibility and Self-Compassion in Appearance Concerns after Burn Injuries. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2024, 30, e12754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd Elalem, S.M.; Shehata, O.S.M.H.; Shattla, S.I. The Effect of Self-Care Nursing Intervention Model on Self-Esteem and Quality of Life among Burn Patients. Clin. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamikrouli, E.; Kool, M.B.; van Schie, C.; Van Loey, N.E.E. Feasibility of Mindfulness for Burn Survivors and Parents of Children with Burns. Eur. Burn. J. 2023, 4, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveen, J.; Andersson, G.; Buhrman, B.; Sjöberg, F.; Willebrand, M. Internet-Based Information and Support Program for Parents of Children with Burns: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Burns 2017, 43, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. An Outpatient Program in Behavioral Medicine for Chronic Pain Patients Based on the Practice of Mindfulness Meditation: Theoretical Considerations and Preliminary Results. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1982, 4, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life; Hyperion Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir, A.; Saritas, S. Effect of Yoga Nidra on the Self-Esteem and Body Image of Burn Patients. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2019, 35, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambi, G.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Elshehawy, A.A.; Eltrawy, H.H.; Abodonya, A.M.; Saleh, A.K.; Hussein, R.S. Yoga in Burn: Role of Pranayama Breathing Exercise on Pulmonary Function, Respiratory Muscle Activity and Exercise Tolerance in Full-Thickness Circumferential Burns of the Chest. Burns 2021, 47, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, A.S.; Hall, M.S.; Quinn, K.; Wiggins, B.; Memmott, C.; Brusseau, T.A. An Examination of a Yoga Intervention with Pediatric Burn Survivors. J. Burn. Care Res. 2017, 38, e337–e342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauerbach, J.A.; Pruzinsky, T.; Saxe, G.N. Psychological Health and Function After Burn Injury: Setting Research Priorities. J. Burn. Care Res. 2007, 28, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. Explorations into the Nature and Function of Compassion. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.; Raffone, A.; Aglioti, S.M. The Pattern Theory of Compassion. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2024, 28, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albertson, E.R.; Neff, K.D.; Dill-Shackleford, K.E. Self-Compassion and Body Dissatisfaction in Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Brief Meditation Intervention. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.D.; Park, C.L.; Gorin, A. Self-Compassion, Body Image, and Disordered Eating: A Review of the Literature. Body Image 2016, 17, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.; Kent, G. Adjusting to Disfigurement: Processes Involved in Dealing with Being Visibly Different. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 21, 663–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudson-Cooper, M.S. Adjustment to Visible Stigma: The Case of the Severely Burned. Soc. Sci. Med. B 1981, 15, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.; Niemann, L.; Schmidt, S.; Walach, H. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Health Benefits: A Meta-Analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 57, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U.R.; Alberts, H.J.E.M.; Feinholdt, A.; Lang, J.W.B. Benefits of Mindfulness at Work: The Role of Mindfulness in Emotion Regulation, Emotional Exhaustion, and Job Satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 98, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, F.; Martucci, K.T.; Kraft, R.A.; Gordon, N.S.; McHaffie, J.G.; Coghill, R.C. Brain Mechanisms Supporting the Modulation of Pain by Mindfulness Meditation. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 5540–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, B.; Neely, L.; Vocke, S. The Power of Yoga: Clinical Outcomes and Cutaneous Functional Unit Recruitment for a Patient with Cervical and Upper Extremity Burn Scar Contracture. J. Burn. Care Res. 2018, 39, S135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, J.; Hoffman, H.G.; Bistricky, S.L.; Gonzalez, M.; Rosenberg, L.; Sampaio, M.; Garcia-Palacios, A.; Navarro-Haro, M.V.; Alhalabi, W.; Rosenberg, M.; et al. The Use of Virtual Reality Facilitates Dialectical Behavior Therapy® “Observing Sounds and Visuals” Mindfulness Skills Training Exercises for a Latino Patient with Severe Burns: A Case Study. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spijkerman, M.P.J.; Pots, W.T.M.; Bohlmeijer, E.T. Effectiveness of Online Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Improving Mental Health: A Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 45, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommers-Spijkerman, M.; Austin, J.; Bohlmeijer, E.; Pots, W. New Evidence in the Booming Field of Online Mindfulness: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e28168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotink, R.A.; Meijboom, R.; Vernooij, M.W.; Smits, M.; Hunink, M.G.M. 8-Week Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction Induces Brain Changes Similar to Traditional Long-Term Meditation Practice—A Systematic Review. Brain Cogn. 2016, 108, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.Y.; Lu, Q.; Geng, X.; Stein, E.A.; Yang, Y.; Posner, M.I. Short-Term Meditation Induces White Matter Changes in the Anterior Cingulate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 15649–15652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, L.; Atchley, R.M.; Oken, B.S. Adherence to Practice of Mindfulness in Novice Meditators: Practices Chosen, Amount of Time Practiced, and Long-Term Effects Following a Mindfulness-Based Intervention. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fardin, A.; Rezaei, S.A.; Maslakpak, M.H. Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Anxiety in Burn Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 49, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.M.; Hunter, K.; Clapham, K.; Ryder, C.; Kimble, R.; Griffin, B. Efficacy and Cultural Appropriateness of Psychosocial Interventions for Paediatric Burn Patients and Caregivers: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, C.J.; Lutz, A.; Davidson, R.J. Reconstructing and Deconstructing the Self in Three Families of Meditation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 19, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.C.R.; Dixon, M.L.; Nijeboer, S.; Girn, M.; Floman, J.L.; Lifshitz, M.; Ellamil, M.; Sedlmeier, P.; Christoff, K. Functional Neuroanatomy of Meditation: A Review and Meta-Analysis of 78 Functional Neuroimaging Investigations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 65, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yordanova, J.; Kolev, V.; Mauro, F.; Nicolardi, V.; Simione, L.; Calabrese, L.; Malinowski, P.; Raffone, A. Common and Distinct Lateralised Patterns of Neural Coupling during Focused Attention, Open Monitoring and Loving Kindness Meditation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, K.; O’Neill, S.; Dockray, S. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Mindfulness Interventions on Cortisol. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 2015, 1359105315569095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.E.; Speca, M.; Faris, P.; Patel, K.D. One Year Pre-Post Intervention Follow-up of Psychological, Immune, Endocrine and Blood Pressure Outcomes of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) in Breast and Prostate Cancer Outpatients. Brain Behav. Immun. 2007, 21, 1038–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sveen et al. (2017) | Conn et al. (2017) | Abd Elalem et al. (2018) | Ozdemir & Saritas (2019) | Hawkins et al. (2019) | Sheperd et al. (2019) | Nambi et al. (2021) | Al-Ghabeesh (2022) | Al-Ghabeesh & Mahmoud (2022) | Papamikrouli et al. (2023) | Al-Ghabeesh et al. (2024) | Sheperd et al. (2024) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research question | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Study population | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Participation and drop-out | 1 | 1 | N | N | 0 | N | 1 | N | N | 1 | N | 1 |

| Participant selection | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sample size | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Timeframe of the study | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | N | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Reliable assessment and statistics | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Follow-up assessment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Assessment of outcomes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Blindness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Confounding control | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Quality rating (good, fair, or poor) | G | F | P | G | F | P | G | F | P | F | F | G |

| Year | Authors | Design | Sample | Intervention/ Instruments | Main Findings | Quality Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Sveen et al. | IS (RCT) | 62 parents of children with burn injuries. Mean age = 36.4; females = 42. | Six-week program including psychoeducational factors and mindfulness vs. waitlist control program. | The support program reduced symptoms of posttraumatic stress in parents at post-intervention and 3-month follow-up, but not at 12-month follow-up, with respect to the control group. | Good |

| 2017 | Conn et al. | IS with no control group | 40 children with burn injuries. Mean age = 9.45 years; females = 7. | 4-day yoga intervention (Burn Camp Yoga Kids program). | The program significantly reduced somatic and cognitive anxiety. | Fair |

| 2018 | Abd Elalem et al. | IS with no control group | 34 adults in the burn unit. Mean age = 40.4; females = 18. | 8-week self-care nursing intervention including mindfulness meditations, body scanning, and breathing exercises. | Improvement of self-esteem and QOL at post-intervention. | Poor |

| 2019 | Ozdemir & Saritas | IS (RCT) | 110 burn patients. Mean age = 40.5 years; females = 58. | 4-week program including 30 min of yoga 3 times a week vs. no practice (control). | Yoga Nidra practice significantly increased self-esteem and improved body image in burn patients with respect to the control group. | Good |

| 2019 | Hawkins et al. | CS | 91 parents and primary caregivers of 71 children with burn injuries. Mean age = 33.62; females = 63. | Self-Compassion Scale—Short Form (SCS-SF) | Self-compassion was related to reduced depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms, but not anxiety. | Fair |

| 2019 | Sheperd et al. | CS | 78 burns patients. Mean age = 45.2 years; females = 47. | Derriford Appearance Scale (DAS-24), Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II (AAQ-II), Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire (CFQ), Committed Action Questionnaire (CAQ-8), Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). | Increased appearance anxiety was related to reduced acceptance and cognitive defusion, as well as to reduced levels of various mindfulness facets. | Poor |

| 2021 | Nambi et al. | IS (RCT) | 30 subjects with restrictive lung disease following circumferential burns of the chest. Mean age = 35.2 years; females = 8. | 4-week program of yogic pranayama-based breathing exercise vs. 4-week diaphragmatic breathing exercise. | Pranayama breathing exercise showed more significant improvements in pain intensity, quality of life, pulmonary function, respiratory muscle activity, and exercise tolerance compared to conventional breathing exercise. The results were held at a three-month follow-up. | Good |

| 2022 | Al-Ghabeesh | CS | 224 burn survivors. Mean age = 35.13 years; females = 98. | Mindful awareness and attention scale (MAAS), HADS. | Mindfulness was negatively associated with the level of psychological distress. | Fair |

| 2022 | Al-Ghabeesh & Mahmoud | CS | 212 burn survivors. Mean age = 34.93 years; females = 93. | Mindful Awareness and Attention Scale (MAAS), Burn-Specific QOL (BSHS-B). | QOL was significantly and positively correlated with mindfulness, even while controlling for demographic and clinical variables. | Poor |

| 2023 | Papamikrouli et al. | IS with no control group | 8 burn survivors (mean age = 49.4 years; females = 7) and 9 parents of children with burns (mean age = 52.2 years; female parents = 6). | 8-week MBSR program | The intervention improved mindfulness skills and self-compassion in parents. Both groups reported increased personal goal scores immediately after the intervention and three months later. | Fair |

| 2024 | Al-Ghabeesh et al. | CS | 212 burn survivors. Mean age = 34.93 years; females = 93 | Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6), Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) | Mindfulness was related to reduced psychological distress while controlling for social support and demographic variables. | Fair |

| 2024 | Sheperd et al. | CS * | 175 burns patients. Mean age = 42.2 years; females = 58. | Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II) and Self-Compassion Scale—Short Form (SCS-SF) | Acceptance and self-compassion at admission were associated with decreased appearance concerns cross-sectionally and prospectively at two- and six-month follow-up. | Good |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the European Burns Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simione, L. Effects of Dispositional Mindfulness and Mindfulness-Based Interventions on the Psychosocial Consequences of Burn Injuries: A Systematic Review. Eur. Burn J. 2025, 6, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6020025

Simione L. Effects of Dispositional Mindfulness and Mindfulness-Based Interventions on the Psychosocial Consequences of Burn Injuries: A Systematic Review. European Burn Journal. 2025; 6(2):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6020025

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimione, Luca. 2025. "Effects of Dispositional Mindfulness and Mindfulness-Based Interventions on the Psychosocial Consequences of Burn Injuries: A Systematic Review" European Burn Journal 6, no. 2: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6020025

APA StyleSimione, L. (2025). Effects of Dispositional Mindfulness and Mindfulness-Based Interventions on the Psychosocial Consequences of Burn Injuries: A Systematic Review. European Burn Journal, 6(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6020025