Burden and Costs of Severe Burn Injury in Victoria, Australia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Study Design

2.2.1. The Victorian State Trauma Registry (VSTR)

2.2.2. Victorian Admitted Episodes Dataset and Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset

2.2.3. National Coronial Information System

2.3. Analysis

2.3.1. Inpatient Stay and Emergency Department Re-Imbursement

2.3.2. Calculation of Disability-Adjusted Life Years

2.3.3. Economic Burden of Severe Burns

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

3.2. Total Re-Imbursements

3.3. Re-Imbursement by Size of Burn

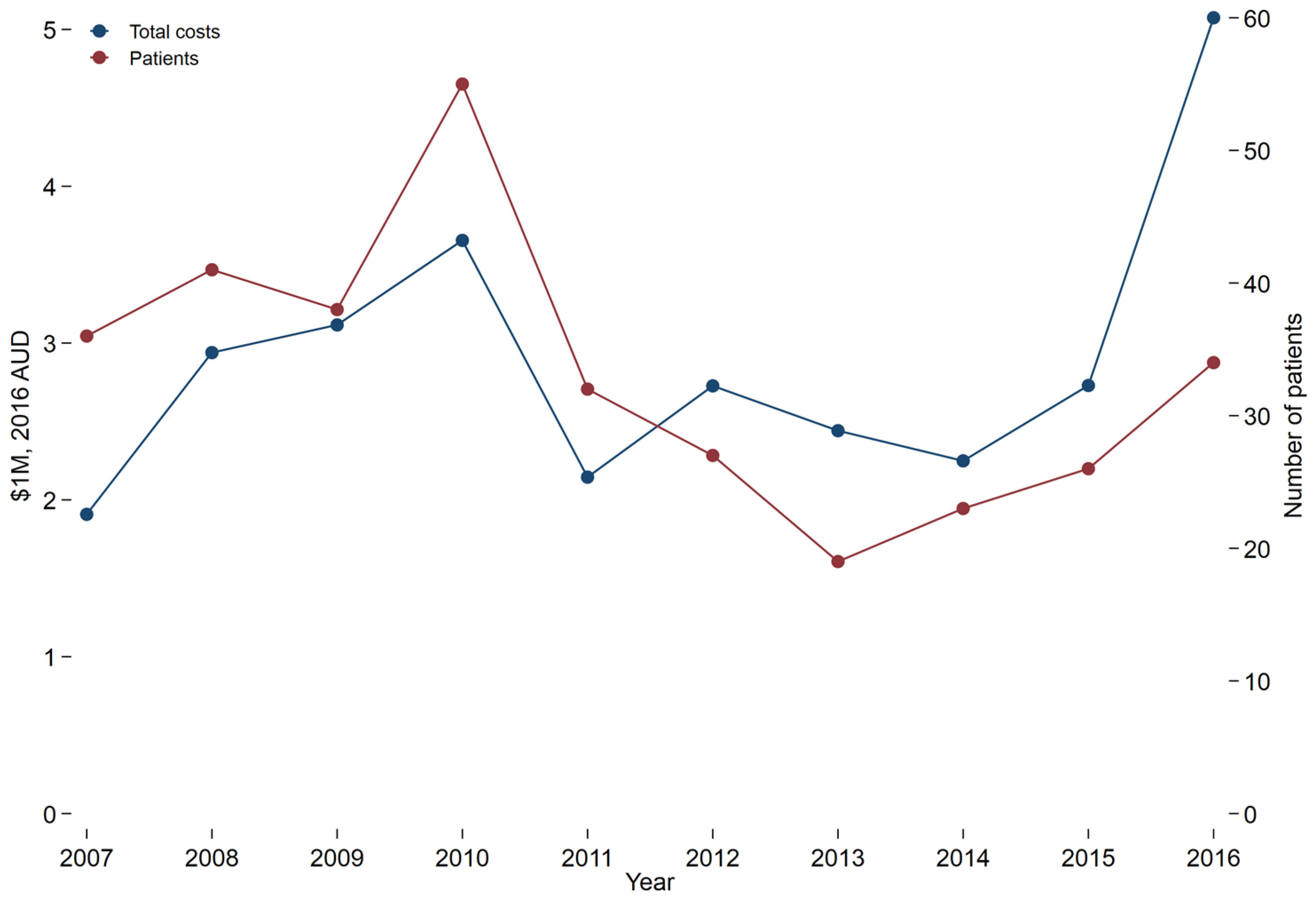

3.4. Re-Imbursement for Treatment by Year

3.5. Quality of Life and Disability Adjusted Life Years

4. Discussion

4.1. Health-Care Re-Imbursement

4.2. Overall Burden of Injury

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, S.R.; Sensing, T.A.; Thede, K.A.; Johnson, R.M.; Fox, J.P. Hospital-based, acute care within 30 days following discharge for acute burn injury. Burns 2021, 47, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppi, J.; Cleland, H.; Gabbe, B. Severe burns in Australian and New Zealand adults: Epidemiology and burn centre care. Burns 2019, 45, 1456–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, C.S.; Maitz, P.K.M. The true cost of burn. Burns 2012, 38, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabbe, B.J.; Cleland, H.J.; Cameron, P.A. Profile, transport and outcomes of severe burns patients within an inclusive, regionalized trauma system. ANZ J. Surg. 2011, 81, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Policy and Funding Guidelines; Victorian Government: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, K.; Lam, M.; Mitchell, R.; Dickson, C.; McDonnell, K. Major trauma: The unseen financial burden to trauma centres, a descriptive multicentre analysis. Aust. Health Rev. 2014, 38, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duncan, R.T.; Dunn, K.W. Burn service costing using a mixed model methodology. Burns 2020, 46, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Life Tables, States, Territories and Australia, 2013–2015. 2016. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/3302.0.55.0012013-2015 (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- State of Victoria. Victorian State Trauma Registry. Available online: https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/hospitals-and-health-services/patient-care/acute-care/state-trauma-system/state-trauma-registry (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Green, J.; Gordon, R.; Kobel, C.; Blanchard, M.; Eagar, K. The Australian National Subacute and Non-Acute Patient Classification AN-SNAP, 4th ed.; IHPA: Wollongong, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Haagsma, J.A.; Graetz, N.; Bolliger, I.; Naghavi, M.; Higashi, H.; Mullany, E.C.; Abera, S.F.; Abraham, J.P.; Adofo, K.; Alsharif, U.; et al. The global burden of injury: Incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Inj. Prev. 2016, 22, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beck, B.; Cameron, P.A.; Fitzgerald, M.C.; Judson, R.T.; Teague, W.; Lyons, R.A.; Gabbe, B.J. Road safety: Serious injuries remain a major unsolved problem. Med. J. Aust. 2017, 207, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbe, B.J.; Lyons, R.A.; Fitzgerald, M.C.; Judson, R.; Richardson, J.; Cameron, P.A. Reduced Population Burden of Road Transport–related Major Trauma After Introduction of an Inclusive Trauma System. Ann. Surg. 2015, 261, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Öster, C.; Willebrand, M.; Dyster-Aas, J.; Kildal, M.; Ekselius, L. Validation of the EQ-5D questionnaire in burn injured adults. Burns 2009, 35, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbe, B.J.; Simpson, P.M.; Cameron, P.; Ponsford, J.; Lyons, R.A.; Collie, A.; Fitzgerald, M.; Judson, R.; Teague, W.J.; Braaf, S.; et al. Long-term health status and trajectories of seriously injured patients: A population-based longitudinal study. PLOS Med. 2017, 14, e1002322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of Best Practice Regulation, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Best Practice Regulation Guidance Note: Value of Statistical Life; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://obpr.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-06/value-of-statistical-life-guidance-note-2.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Hop, M.J.; Polinder, S.; Van Der Vlies, C.H.; Middelkoop, E.; Van Baar, M.E. Costs of burn care: A systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2014, 22, 436–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prasad, J.K.; Bowden, M.L.; Thomson, P.D. A review of the reconstructive surgery needs of 3167 survivors of burn injury. Burns 1991, 17, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikehult, B.; Willebrand, M.; Kildal, M.; Lannerstam, K.; Fugl-Meyer, A.; Ekselius, L.; Gerdin, B. Use of healthcare a long time after severe burn injury; relation to perceived health and personality characteristics. Disabil. Rehabil. 2005, 27, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eidelson, S.A.; Parreco, J.; Mulder, M.B.; Dharmaraja, A.; Kaufman, J.I.; Proctor, K.G.; Pizano, L.R.; Schulman, C.I.; Namias, N.; Rattan, R. Variation in National Readmission Patterns After Burn Injury. J. Burn Care Res. 2018, 39, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterwijk, A.M.; Mouton, L.J.; Schouten, H.; Disseldorp, L.M.; van der Schans, C.P.; Nieuwenhuis, M.K. Prevalence of scar contractures after burn: A systematic review. Burns 2017, 43, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karashchuk, I.P.; Solomon, E.A.; Greenhalgh, D.G.; Sen, S.; Palmieri, T.L.; Romanowski, K.S. Follow-up After Burn Injury Is Disturbingly Low and Linked with Social Factors. J. Burn Care Res. 2021, 42, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckett, S.J.; Breadon, P.; Weidmann, B.; Nicola, I. Controlling Costly Care: A Billion-Dollar Hospital Opportunity; Grattan Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2014; ISBN 978-1-925015-52-22014. [Google Scholar]

- Jeevan, R.; Rashid, A.; Lymperopoulos, N.S.; Wilkinson, D.; James, M.I. Mortality and treatment cost estimates for 1075 consecutive patients treated by a regional adult burn service over a five year period: The Liverpool experience. Burns 2014, 40, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemington-Gorse, S.J.; Potokar, T.S.; Drew, P.J.; Dickson, W.A. Burn care costing: The Welsh experience. Burns 2009, 35, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, T.; Koljonen, V.; Seifert, B.; Volbracht, J.; Giovanoli, P.; Plock, J.; Moos, R.M. Total inpatient treatment costs in patients with severe burns: Towards a more accurate reimbursement model. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2015, 145, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gabbe, B.; Lyons, R.; Simpson, P.; Rivara, F.; Ameratunga, S.; Polinder, S.; Derrett, S.; Harrison, J. Disability weights based on patient-reported data from a multinational injury cohort. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 806–816C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spronk, I.; Edgar, D.W.; Van Baar, M.E.; Wood, F.M.; Van Loey, N.E.E.; Middelkoop, E.; Renneberg, B.; Öster, C.; Orwelius, L.; Moi, A.L.; et al. Improved and standardized method for assessing years lived with disability after burns and its application to estimate the non-fatal burden of disease of burn injuries in Australia, New Zealand and the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spronk, I.; Legemate, C.; Oen, I.; van Loey, N.; Polinder, S.; van Baar, M. Health related quality of life in adults after burn injuries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koljonen, V.; Laitila, M.; Rissanen, A.M.; Sintonen, H.; Roine, R.P. Treatment of Patients with Severe Burns—Costs and Health-Related Quality of Life Outcome. J. Burn Care Res. 2013, 34, e318–e325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.L.A.; Bastida, J.L.; Martínez, M.M.; Moreno, J.M.M.; Chamorro, J.J. Socio-economic cost and health-related quality of life of burn victims in Spain. Burns 2008, 34, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | % Total Body Surface Area | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–29% | 30–39% | 40–89% | All Patients | |

| Total N | 148 | 65 | 118 | 331 |

| Demographics and injury characteristics | ||||

| Died | * Hidden, <10 | 9 (13.85%) | 62 (52.54%) | 74 (22.36%) |

| Male sex | 114 (77.03%) | 42 (64.62%) | 90 (76.27%) | 246 (74.32%) |

| Patient age category (years) | ||||

| 16–34 | 57 (38.51%) | 26 (40.00%) | 29 (24.58%) | 112 (33.84%) |

| 35–64 | 67 (45.27%) | 25 (38.46%) | 70 (59.32%) | 162 (48.94%) |

| 65+ | 24 (16.22%) | 14 (21.54%) | 19 (16.10%) | 57 (17.22%) |

| Length of stay (days), mean (SD) | 26.71 (18.64) | 36.58 (20.34) | 37.23 (42.95) | 32.40 (30.25) |

| ICU admission | 69 (46.62%) | 43 (66.15%) | 89 (75.42%) | 201 (60.73%) |

| Hours ventilated (If stayed in ICU), median (IQR) | 40.00 (15.00, 194.00) | 176.00 (57.00, 337.00) | 193.00 (13.00, 498.00) | 98.00 (16.00, 312.00) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) | ||||

| None | 103 (69.59%) | 36 (55.38%) | 79 (66.95%) | 218 (65.86%) |

| CCI = 1 | 29 (19.59%) | 20 (30.77%) | 13 (11.02%) | 62 (18.73%) |

| CCI > 1 | 16 (10.81%) | 9 (13.85%) | 26 (22.03%) | 51 (15.41%) |

| Intentional injury | 17 (11.49%) | 5 (7.69%) | 43 (36.44%) | 65 (19.64%) |

| Compensation status | ||||

| Not compensable | 123 (83.11%) | 56 (86.15%) | 107 (90.68%) | 286 (86.40%) |

| Compensable | 25 (16.89%) | 9 (13.85%) | 11 (9.32%) | 45 (13.60%) |

| 20–29% TBSA | 30–39% TBSA | 40–89% TBSA | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INITIAL INJURY TREATMENT | ||||

| Number of patients | 148 | 65 | 118 | 331 |

| Emergency Department (2016 AUD), median (IQR) | $1403 ($873, $1744) | $1364 ($873, $1691) | $1364 ($1250, $2145) | $1403 ($950, $1993) |

| Emergency Department (2016 AUD), mean (SD) | $1465 ($661) | $1454 ($591) | $1684 ($887) | $1542 ($745) |

| Hospital admission (2016 AUD), median (IQR) | $25,772 ($15,979, $83,028) | $93,173 ($26,120, $138,668) | $78,831 ($2,729, $214,092) | $37,256 ($12,398, $135,633) |

| Hospital admission (2016 AUD), mean (SD) | $52,867 ($57,980) | $102,902 ($91,202) | $118,401 ($124,823) | $86,055 ($97,769) |

| Total (2016 AUD), median (IQR) | $27,760 ($17,267, $84,476) | $94,405 ($27,523, $139,490) | $79,919 ($4,644, $214,981) | $39,343 ($13,844, $137,452) |

| Total (2016 AUD), mean (SD) | $54,292 ($58,177) | $104,312 ($91,357) | $120,085 ($124,899) | $87,570 ($97,913) |

| FOLLOW UP TREATMENT WITHIN 2 YEARS OF INJURY | ||||

| Number of ED visits, median (IQR) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) |

| Emergency Department (2016 AUD), median (IQR) | $730 ($375, $1518) | $829 ($380, $1307) | $1087 ($639, $1963) | $789 ($380, $1624) |

| Emergency Department (2016 AUD), mean (SD) | $1370 ($2022) | $1167 ($1113) | $1561 ($1466) | $1370 ($1757) |

| Number of Hospital admissions, median (IQR) | 1.00 (0.00, 2.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 2.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 2.00) |

| Hospital admission (2016 AUD), median (IQR) | $4648 ($2147, $10,985) | $5732 ($2198, $20,583) | $12,074 ($,5224, $25,659) | $6976 ($2303, $15,249) |

| Hospital admission (2016 AUD), mean (SD) | $9343 ($13,519) | $13,226 ($17,230) | $21,129 ($28,105) | $13,376 ($19,841) |

| Total (2016 AUD), median (IQR) | $2870 ($1057, $9788) | $ 3947 ($1307, $14,492) | $12,179 ($5160, $22,990) | $5120 ($1461, $13,699) |

| Total (2016 AUD), mean (SD) | $8172 ($13,275) | $ 11,163 ($16,756) | $ 20,936 ($28,492) | $11,853 ($19,320) |

| Year | Cases with Disability | Total Deaths | Prehospital Deaths | Years of Life Lost (YLLs) | Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) | Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 52 | 45 | 34 | 933 | 63 | 996 |

| 2008 | 62 | 54 | 41 | 1027 | 72 | 1099 |

| 2009 | 64 | 232 | 220 | 4665 | 72 | 4737 |

| 2010 | 82 | 27 | 21 | 538 | 102 | 640 |

| 2011 | 65 | 34 | 27 | 612 | 79 | 691 |

| 2012 | 62 | 33 | 29 | 732 | 73 | 805 |

| 2013 | 52 | 40 | 31 | 816 | 63 | 879 |

| 2014 | 56 | 52 | 41 | 962 | 66 | 1028 |

| 2015 | 58 | 43 | 31 | 778 | 66 | 844 |

| 2016 | 72 | 37 | 23 | 685 | 81 | 766 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cleland, H.; Sriubaite, I.; Gabbe, B. Burden and Costs of Severe Burn Injury in Victoria, Australia. Eur. Burn J. 2022, 3, 391-400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3030034

Cleland H, Sriubaite I, Gabbe B. Burden and Costs of Severe Burn Injury in Victoria, Australia. European Burn Journal. 2022; 3(3):391-400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3030034

Chicago/Turabian StyleCleland, Heather, Ieva Sriubaite, and Belinda Gabbe. 2022. "Burden and Costs of Severe Burn Injury in Victoria, Australia" European Burn Journal 3, no. 3: 391-400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3030034