Electronic Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Burn Scar Rehabilitation: A Guide to Implementation and Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Organisation of the Paper and Context behind Recommendations

3. Body Section

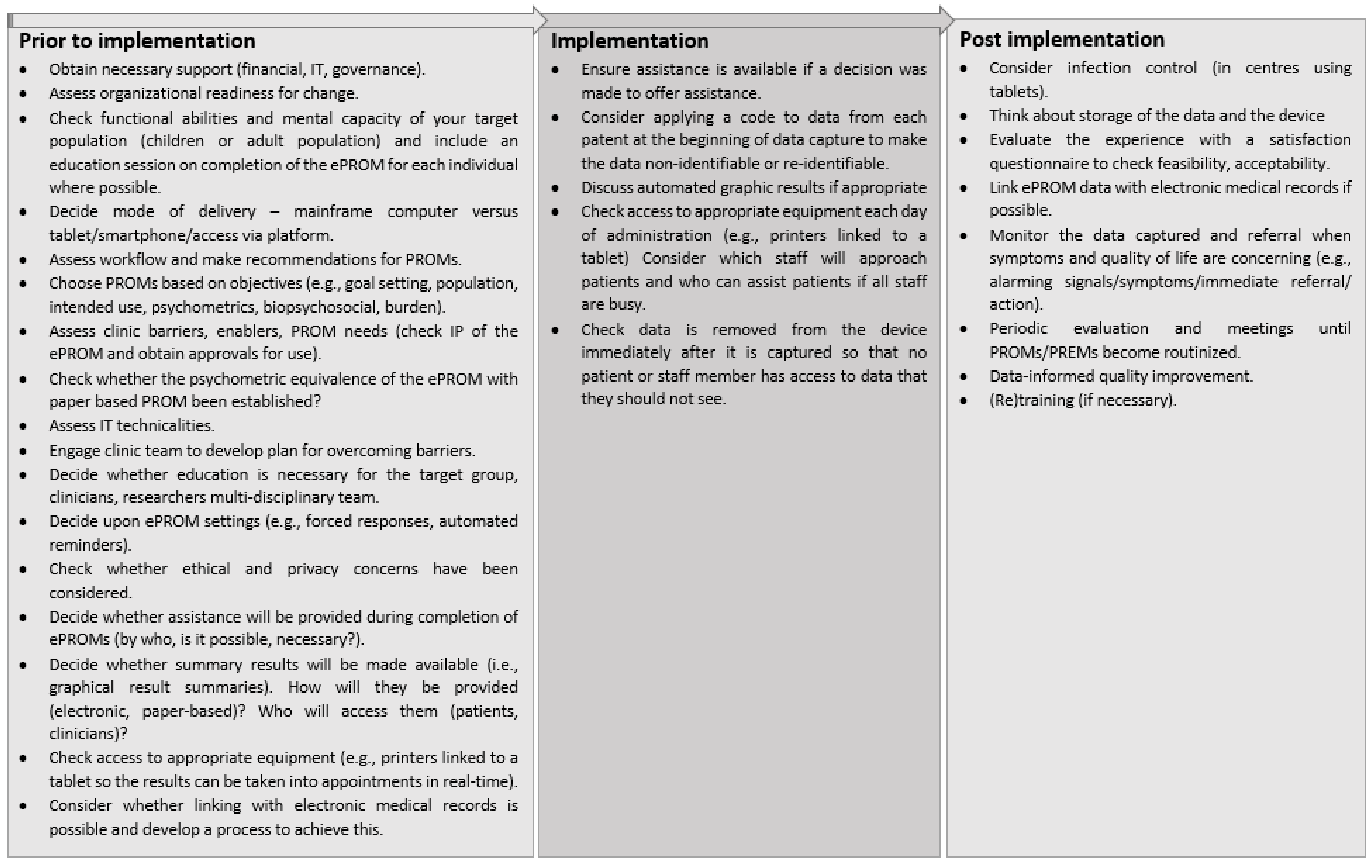

3.1. Processes and Strategies for Implementing ePROMs

3.1.1. Preparing for Implementation

- Population

- Context and setting

- Resources

- Mode of administration

3.1.2. Selecting, Administering, and Scoring PROMs

- Selecting

- Administering

- Scoring

3.1.3. ePROM Results, Feedback, Evaluation, and Training

3.1.4. Overarching Considerations

- Ethical considerations

- Security

- Policy and culture

- Changing behaviour and readiness for implementing ePROMs

- Equity of access

- Conceptual frameworks

- Dissemination of information

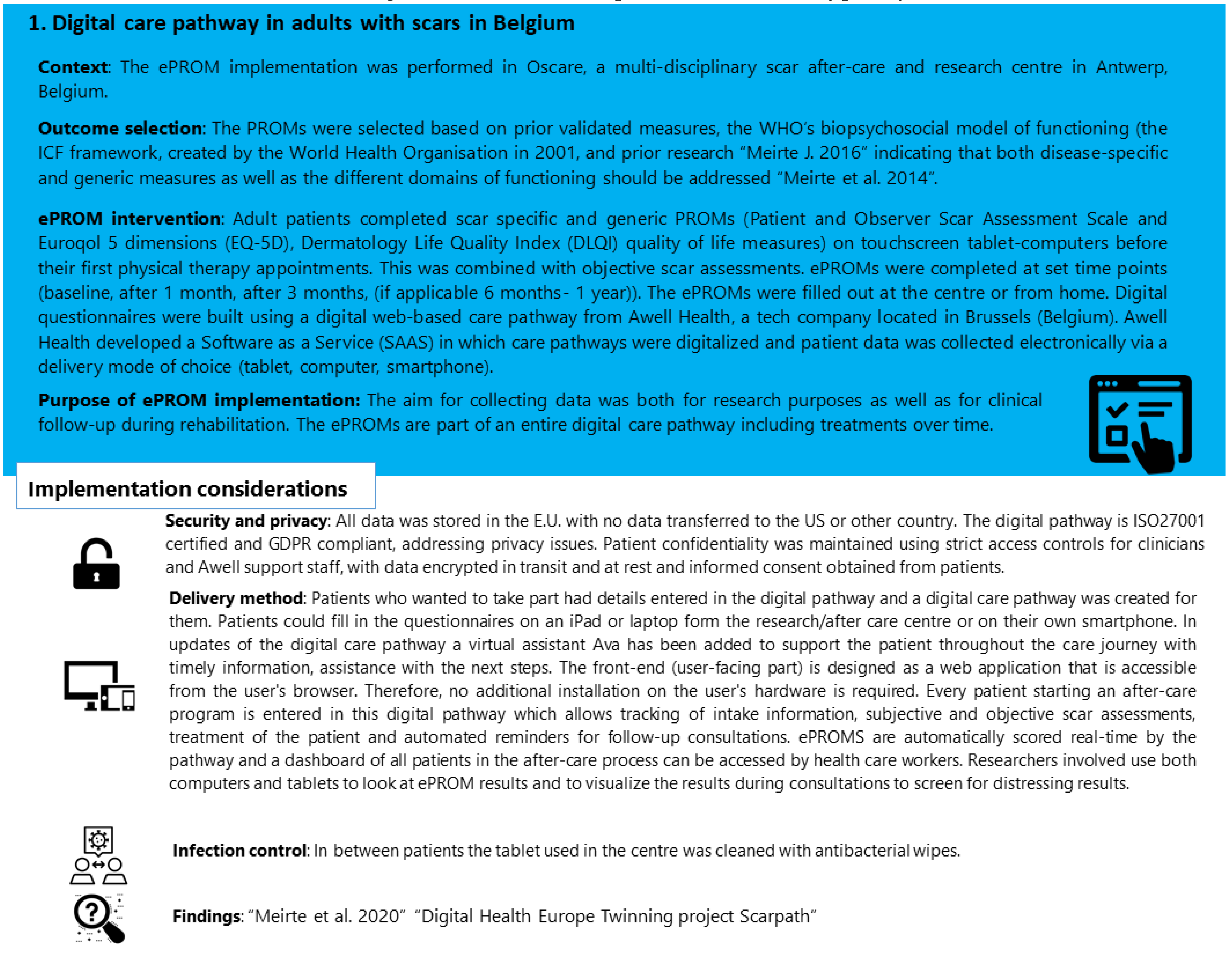

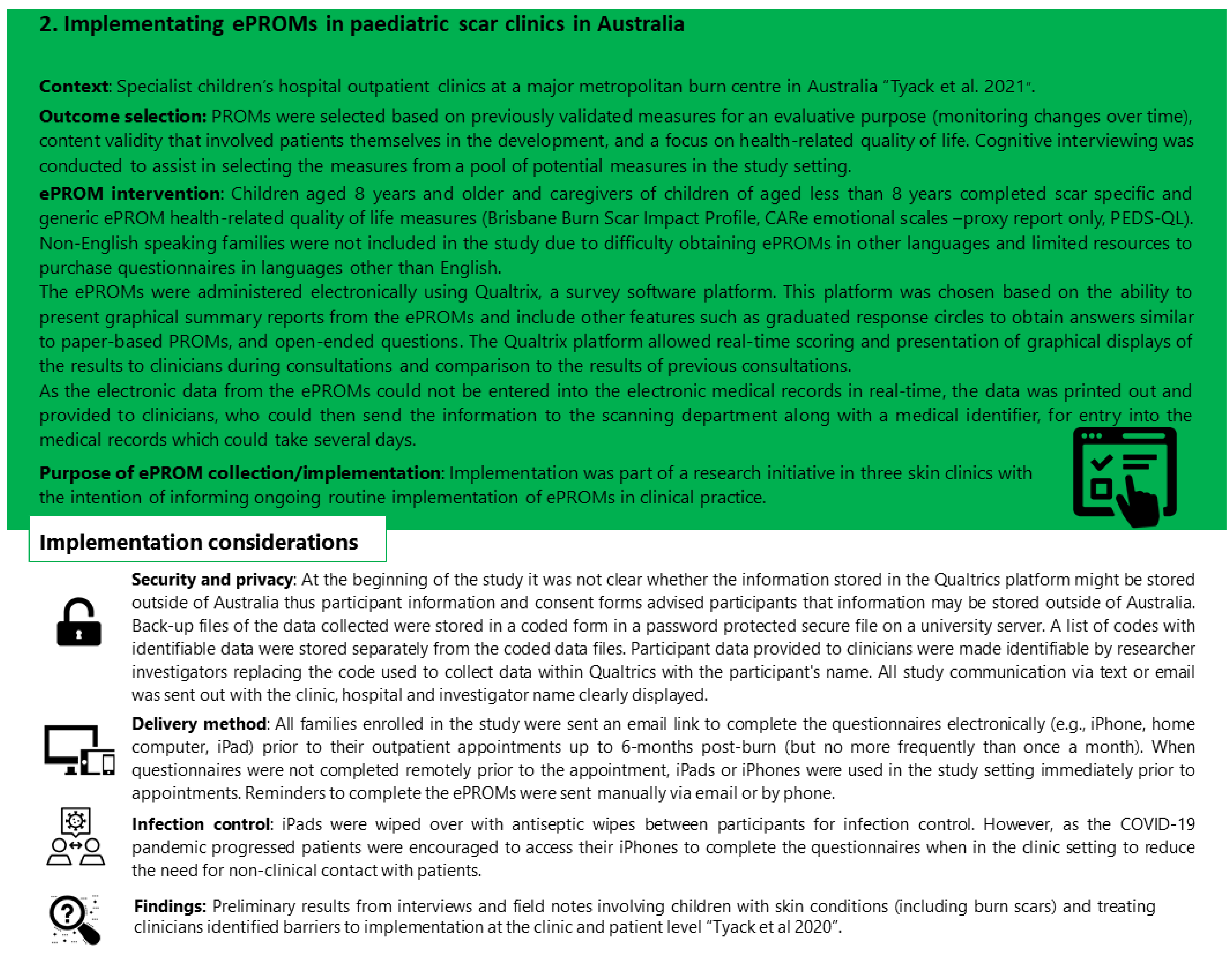

3.2. Case Studies

3.3. Lessons Learned

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Resources to Support Choosing and Implementing PROMs in Routine Clinical Care

| Broad Description | Key Information and Relevant Points of Attention | |

| Clinical guidelines and processes | ISOQOL user’s guide implementing PROMs in clinical practice. Version 2. 2015 | This guide aims to help clinicians interested in using PROMs in their clinical practice to think through key aspects of implementation. Questions addressed include: 1. What are your goals for collecting PROs in your clinical practice? 2. What resources are available? 3. Which key barriers require attention? 4. Which groups of patients will you assess? 5. How do you select which questionnaire to use? 6. How often should patients complete questionnaires? 7. How will the PROs be administered and scored? 8. What tools are available to assist in interpretating PROMs? 9. When, where, how, and to whom will results be presented? 10. What will be done to respond to issues identified through PROMs? [11] |

| ISOQOL companion guide and users guide | This guide builds on the user’s guide to assist clinicians to address considerations involved in implementing and using PROMs in clinical care using information from real-world case studies [20]. | |

| A PROM implementation cycle across four phases is presented with accompanying instruments, checklists, methods, handbooks, and standards. | The four phases of implementation are: 1. Goal setting 2. Selecting PROs and PROMs 3. Developing and testing quality indicators 4. Implementing and evaluating the PROMs and indicators [68]. | |

| Selecting outcomes and evaluation in burn and burn scar populations | Patient-Reported Outcomes in routine care—a true innovation but only if used correctly | Choosing the right PROMs depends on the purpose of use, for example whether it is for clinical use or for research, for a single measure or for longitudinal follow-up. This paper suggests three questions to prepare for implementation: 1. Is the goal to measure change at an individual or a group level? 2. Do the PROMs ask questions that are relevant to my patients, clinic, and/or research? 3. Is the PROM validated for my population of interest? [69] |

| Systematic review of PROMs used in adult burn research in articles from January 2001 to September 2016 * | Thirteen generic PROMs were reported to have evidence of validation data with English speaking adults with burn injuries: 1. Perceived Stigmatization Questionnaire (PSQ) 2. Social Comfort Questionnaire (SCQ) 3. Satisfaction with Appearance Scale (SWAP) 4. Short Form 36-item Medical 5. Outcomes Survey (SF-36) 6. DASH and QuickDash 7. POSAS 8. LLFI-10 9. Community Integration Questionnaire 10. Brief Cope 11. McGill Pain Scale 12. Brief Fatigue Inventory 13. Davidson Trauma Scale Four burn-specific PROMs were reported to have been validated in English with adults with a burn: 1. Burn-Specific Health Scale-Abbreviated (BSHS-A) 2. Burn-Specific Health Scale-Brief (BSHS-B) 3. Young Adults Burns Outcomes Questionnaire (YABOQ) 4. Burn-Specific Pain Anxiety Scale (BSPAS) [3] | |

| Systematic review of PROMs used in child and adolescent burn research from January 2001 to March 2013 * | Two generic PROMs were validated in English with children and adolescents with burns: 1. Perceived Stigmatisation Questionnaire 2. Social Comfort Scale One burn-specific PROM was validated with adolescents with burns: 1. Children Burn Outcomes Questionnaire for children aged 5–18 Note: the search was limited to articles that had been written up for research purposes [4] | |

| Outcomes important to patients with burns during scar management and comparison to burn-specific PROMs based on qualitative research | Eight core outcome domains were identified as important to children and adults in burn scar management: 1. scar characteristics and appearance 2. movement and function 3. scar sensation 4. psychological distress, adjustments, and a sense of normality 5. body image and confidence 6. engagement in activities 7. impact on relationships 8. treatment burden [70] | |

| Seeding the value-based healthcare and standardised measurement of quality of life after burn debate * | Call to use the same quality of life measure at 4 weeks and 3 months post burn. Quality of life measures for the adult burn population established and emerging were: SF-36, EQ-5D, BSHS-B, VR-36 and LIBRE profile. [71] Strong suggestion for teams to pilot a standardised schedule of administration at 4–6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months after burn injury date. | |

| Core Outcome Set for Burns (COSB) which may have relevance in choosing outcomes to measure preventing or treating patients with burn scars * | Consensus methods used to identify the seven highest ranked outcomes for burns involving clinicians and patients across different stages of burn care: 1. death 2. specified complications 3. ability to do daily tasks 4. wound healing 5. neuropathic pain and itch 6. psychological well-being 7. time to return to work/school [72] | |

| A systematic review of the quality of burn scar rating scales for clinical and research use and guide for choosing burn scar scales based on an updated systematic review | Quality of burn rating scales:

The content, purpose, test sample characteristics, and feasibility of eight scales is reviewed in depth, including POSAS, VSS, modified VSS, Matching Assessment using Photographs with Scars (MAPS), and Visual Analogue Scale [74]. | |

| Checklists for assessing study quality related to PROM development and validation by COSMIN | Available checklists can be used to assess the methodological quality of PROMs and studies on PROM development or testing. Checklists have been developed by the COSMIN (COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments) group and include:

| |

| Barriers to PROM implementation | Remarkably consistent barriers to the implementation of PROMs have been reported across settings and studies and should be considered prior to implementation | Four consistent barriers to PROM implementation have been identified: 1. Technology 2. Stakeholder uncertainty about the use of PROMs 3. Stakeholder concerns about negative impacts of PROM use 4. Competing demands from established clinical workflows [47] Difficulty tailoring to individual patients has also been identified as a barrier to implementation in a review of systematic reviews. [18] |

| Measurement equivalence of paper and ePROMs | Recommendations on evidence needed to support measurement equivalence between paper and ePROMs | A general framework for decisions regarding the level of evidence needed to support modifications that are made to PROMs when they are migrated from paper to ePROM devices. Key issues:

Consider the nature of each response scale in the instrument to evaluate the appropriateness for migration to the target mode. Response scales such as graduated circles may be difficult to transition from paper to electronic platforms without alteration [75]. |

| Pediatrics considerations | Report of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) and Patient Reported Outcomes (PRO) on good research practices for the assessment of children and adolescents task force | Good research practices outlined are related to:

|

| Include child self-report perspectives | Child self-report about what makes a good life should be prioritised and may differ to parent report [76,77,78]. Where it is difficult to obtain self-report, it has been suggested that proxy report be obtained alongside child self-report where possible [78]. | |

| Frequently used generic PROMs | Six PROMs were evaluated to report health states: 1. Pediatric Quality-of-Life inventory 4.0 (PedsQL) 2. Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ) 3. KIDSCREEN 4. KINDL 5. DISABKIDS 6. Child Health and Illness Profile (CHIP). All capture domains of physical, social, emotional health, and school activities. No measure appropriately captured all relevant age-appropriate domains in PROMs:

| |

| Additional resources | Training clinicians to use PROMs in clinical practice | Drawing from case studies of training programs for PROM implementation across three countries and in diverse clinical areas (adult oncology, lung transplant, paediatrics) it was concluded that training sessions should be:

|

| Best Practices for Migrating Existing Patient-Reported Outcome Instruments to a New Data Collection Mode | Created by an ePRO consortium. Addresses issues that should be considered when migrating existing patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments to any available data collection mode (e.g., paper, interactive voice response [IVR] system, tablet, web, handheld) [23] | |

| * The relevance of burn outcomes to those with burn scars is not clear; thus, we advocate prioritising research targeting burn scar populations to guide the selection of PROMs for people with burn scars until further evidence emerges regarding the relevance of burn outcomes to people with burn scars. | ||

References

- Rivera, S.C.; Mercieca-Bebber, R.; Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Scott, J.; Hunn, A.; Fernandez, C.; Ives, J.; Ells, C.; Price, G.; Draper, H.; et al. The need for ethical guidance for the use of patient-reported outcomes in research and clinical practice. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 572–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyack, Z.; Simons, M.; McPhail, S.M.; Harvey, G.; Zappala, T.; Ware, R.S.; Kimble, R.M. Improving the patient-centred care of children with life-altering skin conditions using feedback from electronic patient-reported outcome measures: Protocol for a hybrid effectiveness-implementation study (PEDS-ePROM). BMJ Open 2021, 11, e041861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, C.; Guest, E.; White, P.; Gaskin, E.; Rumsey, N.; Pleat, J.; Harcourt, D. A Systematic Review of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Used in Adult Burn Research. J. Burn Care Res. 2017, 38, e521–e545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, C.; Armstrong-James, L.; White, P.; Rumsey, N.; Pleat, J.; Harcourt, D. A systematic review of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) used in child and adolescent burn research. Burns 2014, 41, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Nair, D.; Peipert, J.D.; Schick-Makaroff, K.; Mucsi, I. A narrative review of current evidence supporting the implementation of electronic patient-reported outcome measures in the management of chronic diseases. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ 2013, 346, f167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.; Doll, H.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Jenkinson, C.; Carr, A.J. The routine use of patient reported outcome measures in healthcare settings. BMJ 2010, 340, c186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Burn Care Review Committee. A Review of Burn Care in the British Isles; National Burn Care Review Committee: London, UK, 2001; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.M.; Lee, A.F.; Kazis, L.E.; Shapiro, G.D.; Schneider, J.C.; Goverman, J.; Fagan, S.P.; Wang, C.; Kim, J.; Sheridan, R.L.; et al. Is Real-Time Feedback of Burn-Specific Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Clinical Settings Practical and Useful? A Pilot Study Implementing the Young Adult Burn Outcome Questionnaire. J. Burn Care Res. 2016, 37, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tyack, Z.; Simons, M.; Zappala, T.; Harvey, G.; McPhail, S.; Kimble, R. Barriers and benefits to the routine use of electronic patient-reported outcome measures in treating children with life altering skin conditions. In 27th Annual Conference of the International Society for Quality of Life Research. Qual Life Res. 2020, 29 (Suppl. S1), S46. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, J.; Gooding, K.; Gibbons, E.; Dalkin, S.; Wright, J.; Valderas, J.; Black, N. How do patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) support clinician-patient communication and patient care? A realist synthesis. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2018, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, G.; Booth, L.; Smith, A.B.; Brown, P.M.; Lynch, P.; Brown, J.M.; Selby, P.J. Measuring Quality of Life in Routine Oncology Practice Improves Communication and Patient Well-Being: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, M.; Sawatzky, R. Relational use of an electronic quality of life and practice support system in hospital palliative consult care: A pilot study. Palliat. Support. Care 2018, 17, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espallargues, M.; Valderas, J.M.; Alonso, J. Provision of Feedback on Perceived Health Status to Health Care Professionals. Med. Care 2000, 38, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, C.; Porter, I.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C.; Stoilov, S.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Tsangaris, E.; Gangannagaripalli, J.; Davey, A.; Gibbons, E.J.; Kotzeva, A.; et al. Routine provision of feedback from patient-reported outcome measurements to healthcare providers and patients in clinical practice. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021. Issue 10. Art. No. CD011589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.S.; Kirchner, J. Implementation science: What is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Res. 2019, 283, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meirte, J.; Hellemans, N.; Anthonissen, M.; Denteneer, L.; Maertens, K.; Moortgat, P.; Van Daele, U. Benefits and Disadvantages of Electronic Patient-reported Outcome Measures: Systematic Review. JMIR Perioper. Med. 2020, 3, e15588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, A.; Croot, L.; Brazier, J.; Harris, J.; O’Cathain, A. The facilitators and barriers to implementing patient reported outcome measures in organisations delivering health related services: A systematic review of reviews. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2018, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, N.; Choucair, A.; Elliott, T. User’s guide to implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice. Int. Soc. Qual. Life Res. 2015, Version 2, 1–47. Available online: https://www.isoqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/2015UsersGuide-Version2.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Chan, E.K.H.; Edwards, T.C.; Haywood, K.; Mikles, S.; Newton, L. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in clinical practice: A companion guide to the ISOQOL user’s guide. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 28, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmin Checklists for Assessing Methodological Study Quality. Available online: https://www.cosmin.nl/tools/checklists-assessing-methodological-study-qualities/ (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Matza, L.S.; Patrick, D.L.; Riley, A.W.; Alexander, J.J.; Rajmil, L.; Pleil, A.M.; Bullinger, M. Pediatric Patient-Reported Outcome Instruments for Research to Support Medical Product Labeling: Report of the ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices for the Assessment of Children and Adolescents Task Force. Value Heal. 2013, 16, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ePRO Consortium. Best Practices for Migrating Existing Patient-Reported Outcome Instruments to a New Data Collection Mode. 2014. Available online: https://c-path.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/BestPracticesForMigratingExistingPROInstrumentstoaNewDataCollectionMode.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Mangunkusumo, R.T.; Moorman, P.W.; Ruiter, A.E.V.D.B.-D.; Van Der Lei, J.; De Koning, H.J.; Raat, H. Internet-administered adolescent health questionnaires compared with a paper version in a randomized study. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2005, 36, 70.e1–70.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raat, H.; Mangunkusumo, R.T.; Landgraf, J.M.; Kloek, G.; Brug, J. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of adolescent health status measurement by the Child Health Questionnaire Child Form (CHQ-CF): Internet administration compared with the standard paper version. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, N.L.; Varni, J.W.; Snider, L.; McCormick, A.; Sawatzky, B.; Scott, M.; King, G.; Hetherington, R.; Sears, E.; Nicholas, D. The Internet is valid and reliable for child-report: An example using the Activities Scale for Kids (ASK) and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL). J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engan, H.; Hilmarsen, C.; Sittlinger, S.; Sandmæl, J.A.; Skanke, F.; Oldervoll, L.M. Are web-based questionnaires accepted in patients attending rehabilitation? Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 2406–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keurentjes, J.C.; Fiocco, M.; So-Osman, C.; Onstenk, R.; Koopman-Van Gemert, A.W.M.M.; Poll, R.G.; Nelissen, R. Hip and knee replacement patients prefer pen-and-paper questionnaires. Bone Jt. Res. 2013, 2, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, J.G.; Becker, A.; Koch, T.; Nixdorf, M.; Willers, R.; Monser, R.; Schacher, B.; Alten, R.; Specker, C.; Schneider, M. Self-assessments of patients via Tablet PC in routine patient care: Comparison with standardised paper questionnaires. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008, 67, 1739–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartkopf, A.D.; Graf, J.; Simoes, E.; Keilmann, L.; Sickenberger, N.; Gass, P.; Wallwiener, D.; Matthies, L.; Taran, F.-A.; Lux, M.P.; et al. Electronic-Based Patient-Reported Outcomes: Willingness, Needs, and Barriers in Adjuvant and Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients. JMIR Cancer 2017, 3, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongen, P.J.; Sinnige, L.G.; van Geel, B.M.; Verheul, F.; Verhagen, W.I.; A van der Kruijk, R.; Haverkamp, R.; Schrijver, H.M.; Baart, J.C.; Visser, L.H.; et al. The interactive web-based program MSmonitor for self-management and multidisciplinary care in multiple sclerosis: Utilization and valuation by patients. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2016, 10, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McCleary, N.J.; Wigler, D.; Berry, D.; Sato, K.; Abrams, T.; Chan, J.; Enzinger, P.; Ng, K.; Wolpin, B.; Schrag, D.; et al. Feasibility of Computer-Based Self-Administered Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients with Gastrointestinal Malignancy. Oncologist 2013, 18, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintner, L.M.; Giesinger, J.M.; Zabernigg, A.; Rumpold, G.; Sztankay, M.; Oberguggenberger, A.S.; Gamper, E.M.; Holzner, B. Evaluation of electronic patient-reported outcome assessment with cancer patients in the hospital and at home. BMC Med. Informatics Decis. Mak. 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzner, B.; Giesinger, J.M.; Pinggera, J.; Zugal, S.; Schöpf, F.; Oberguggenberger, A.S.; Gamper, E.M.; Zabernigg, A.; Weber, B.; Rumpold, G. The Computer-based Health Evaluation Software (CHES): A software for electronic patient-reported outcome monitoring. BMC Med. Informatics Decis. Mak. 2012, 12, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick-Makaroff, K.; Molzahn, A. Strategies to use tablet computers for collection of electronic patient-reported outcomes. Heal. Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Touvier, M.; Méjean, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Pollet, C.; Malon, A.; Castetbon, K.; Hercberg, S. Comparison between web-based and paper versions of a self-administered anthropometric questionnaire. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrom, B.; Gwaltney, C.; Slagle, A.; Gnanasakthy, A.; Muehlhausen, W. Measurement Equivalence of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Migrated to Electronic Formats: A Review of Evidence and Recommendations for Clinical Trials and Bring Your Own Device. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2019, 53, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meirte, J.; Hellemans, N.; Anthonissen, M.; Maertens, K.; Moortgat, P.; Van Daele, U. Equivalence and feasibility of the paper based and electronic version of the POSAS, EQ-5D and DLQI in a Belgian population. In Proceedings of the 18th European Burns Association Congress, Helsinki, Finland, 4–7 September 2019. Conference report. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.; Jones, L.; Keeley, T.J.H.; Calvert, M.J.; Mathers, J. A review of patient and carer participation and the use of qualitative research in the development of core outcome sets. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coons, S.J.; Gwaltney, C.J.; Hays, R.D.; Lundy, J.J.; Sloan, J.A.; Revicki, D.A.; Lenderking, W.R.; Cella, D.; Basch, E. Recommendations on Evidence Needed to Support Measurement Equivalence between Electronic and Paper-Based Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Measures: ISPOR ePRO Good Research Practices Task Force Report. Value Heal. 2009, 12, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, A.; Freeman, E. Patients’ views of using an outcome measure in palliative day care: A focus group study. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2004, 10, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, K. Why Indeed? Res. Pr. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2020, 45, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochstenbach, L.M.; Zwakhalen, S.M.; Courtens, A.M.; van Kleef, M.; de Witte, L.P. Feasibility of a mobile and web-based intervention to support self-management in outpatients with cancer pain. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 23, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.; Guest, C.; Pickles, E.; Hollen, T.; Grzeda, L.; White, M.; Tollow, P.; Harcourt, D. The development and vali-dation of the CARe Burn Scale—Adult Form: A Patient Reported Outcome Measure (PROM) to assess quality of life for adults living with a burn injury. J. Burn. Care Res. 2017, 44, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recinos, P.; Dunphy, C.J.; Thompson, N.; Schuschu, J.; Urchek, J.L.; Katzan, I.L. Patient Satisfaction with Collection of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Routine Care. Adv. Ther. 2016, 34, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm. Ment. Heal. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, A.M.; Haverman, L.; Van Oers, H.A.; Greenhalgh, J.; Potter, C.M.; On behalf of the ISOQOL PROMs/PREMs in Clinical Practice Implementation Science Work Group. Using an implementation science approach to implement and evaluate patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) initiatives in routine care settings. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 30, 3015–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishaque, S.; Karnon, J.; Chen, G.; Nair, R.; Salter, A.B. A systematic review of randomised controlled trials evaluating the use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Qual. Life Res. 2018, 28, 567–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownson, R.C.; Kumanyika, S.K.; Kreuter, M.W.; Haire-Joshu, D. Implementation science should give higher priority to health equity. Implement. Sci. 2021, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, S.J.; Mather, C.; Ford, K.; Bywaters, D.; Campbell, S. Person-centred data collection methods to embed the authentic voice of people who experience health challenges. BMJ Open Qual. 2020, 9, e000912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesman, J.; Walsh, K.; Kinsman, L.; Ford, K.; Bywaters, D. Blending Video-Reflexive Ethnography With Solution-Focused Approach: A Strengths-Based Approach to Practice Improvement in Health Care. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Brar, A.; Roihan, N. The use of digital technology to enhance language and literacy skills for Indigenous people: A systematic literature review. Comput. Educ. Open 2021, 2, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moullin, J.C.; Dickson, K.S.; Stadnick, N.A.; Albers, B.; Nilsen, P.; Broder-Fingert, S.; Mukasa, B.; Aarons, G.A. Ten recommendations for using implementation frameworks in research and practice. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2020, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffman, S.; Stone, A.A.; Hufford, M.R. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normalization Process Theory. Available online: http://www.normalizationprocess.org (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Consolidation framework for Implementation Research. Available online: https://cfirguide.org/ (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Harvey, G.; Kitson, A. PARIHS revisited: From heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implement. Sci. 2015, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, A.N.; DeNisi, A. The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 119, 254–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, E.; Haby, M.M.; Toma, T.S.; De Bortoli, M.C.; Illanes, E.; Oliveros, M.J.; Barreto, J.O.M. Knowledge translation strategies for dissemination with a focus on healthcare recipients: An overview of systematic reviews. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awell Health. Available online: http://awellhealth.com/ (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- The International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health. Available online: www.who.int/classifications/ICF/en (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Meirte, J.; van Loey, N.; Maertens, K.; Moortgat, P.; Hubens, G.; Van Daele, U. Classification of quality of life subscales within the ICF framework in burn research: Identifying overlaps and gaps. Burns 2014, 40, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meirte, J. The ICF as a Framework for Post Burn Dysfunctioning: Evaluation, Quality of Life and Vacuum Massage in Patients with Hypertrophic Burn Scars. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Digital Health Europe. Available online: https://digitalhealtheurope.eu/twinnings/dhe-twinning-results/scarpath/ (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Friedstat, J.S.; Ryan, C.M.; Gibran, N. Outcome Metrics After Burn Injury. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2017, 44, 911–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Brenner, A.T. Beginning with high value care in mind: A scoping review and toolkit to support the content, delivery, measurement, and sustainment of high value care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, A.; Pifeleti, S.; Driscoll, C. The need for translation and cultural adaptation of audiology questionnaires to enable the development of hearing healthcare policies in the Pacific Islands: A Samoan perspective. Arch. Public Heal. 2021, 79, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Wees, P.J.; Verkerk, E.W.; Verbiest, M.E.A.; Zuidgeest, M.; Bakker, C.; Braspenning, J.; De Boer, D.; Terwee, C.B.; Vajda, I.; Beurskens, A.; et al. Development of a framework with tools to support the selection and implementation of patient-reported outcome measures. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2019, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young-Afat, D.A. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Routine Care—A True Innovation but Only If Used Correctly. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.L.; Calvert, M.; Moiemen, N.; Deeks, J.J.; Bishop, J.; Kinghorn, P.; Mathers, J. Outcomes important to burns patients during scar management and how they compare to the concepts captured in burn-specific patient reported outcome measures. Burns 2017, 43, 1682–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, D.; Van Daele, U.; Spronk, I.; van Baar, M.; van Loey, N.; Wood, F.; Kazis, L.; Meirte, J. Seeding the value based health care and standardised measurement of quality of life after burn debate. Burns 2020, 46, 1721–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A. A Global Core Outcome Set to Optimise the Evidence Base for Burn Care (COSB-i); University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tyack, Z.; Simons, M.; Spinks, A.; Wasiak, J. A systematic review of the quality of burn scar rating scales for clinical and research use. Burns 2011, 38, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyack, Z.; Wasiak, J.; Spinks, A.; Kimble, R.; Simons, M. A guide to choosing a burn scar rating scale for clinical or research use. Burns 2013, 39, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjermstad, M.J.; Fayers, P.M.; Haugen, D.F.; Caraceni, A.; Hanks, G.W.; Loge, J.H.; Fainsinger, R.; Aass, N.; Kaasa, S. Studies Comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for Assessment of Pain Intensity in Adults: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2011, 41, 1073–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmingsson, H.; Ólafsdóttir, L.B.; Egilson, S.T. Agreements and disagreements between children and their parents in health-related assessments. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 39, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ólafsdóttir, L.B.; Egilson, S.T.; Árnadóttir, U.; Hardonk, S.C. Child and parent perspectives of life quality of children with physical impairments compared with non-disabled peers. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 26, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health Guidance for industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims: Draft guidance. Heal. Qual. Life Outcomes 2006, 4, 1–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsiwala, T.; Afroz, N.; Kordy, K.; Naujoks, C.; Patalano, F. Measuring What Matters for Children: A Systematic Review of Frequently Used Pediatric Generic PRO Instruments. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2021, 55, 1082–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, E.D.; Dobrozsi, S.K.; Forrest, C.B.; Gerhardt, W.E.; Kliems, H.; Reeve, B.B.; Rothrock, N.E.; Lai, J.-S.; Svenson, J.M.; Thompson, L.A.; et al. Considerations to Support Use of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Pediatric Measures in Ambulatory Clinics. J. Pediatr. 2020, 230, 198–206.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.J.; Haverman, L.; Absolom, K.; Takeuchi, E.; Feeny, D.; Grootenhuis, M.; Velikova, G. Training clinicians in how to use patient-reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1707–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meirte, J.; Tyack, Z. Electronic Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Burn Scar Rehabilitation: A Guide to Implementation and Evaluation. Eur. Burn J. 2022, 3, 290-308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3020025

Meirte J, Tyack Z. Electronic Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Burn Scar Rehabilitation: A Guide to Implementation and Evaluation. European Burn Journal. 2022; 3(2):290-308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3020025

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeirte, Jill, and Zephanie Tyack. 2022. "Electronic Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Burn Scar Rehabilitation: A Guide to Implementation and Evaluation" European Burn Journal 3, no. 2: 290-308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3020025

APA StyleMeirte, J., & Tyack, Z. (2022). Electronic Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Burn Scar Rehabilitation: A Guide to Implementation and Evaluation. European Burn Journal, 3(2), 290-308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3020025