Persistent Geographic Patterns of Coral Recruitment in Hawaiʻi

Abstract

1. Introduction

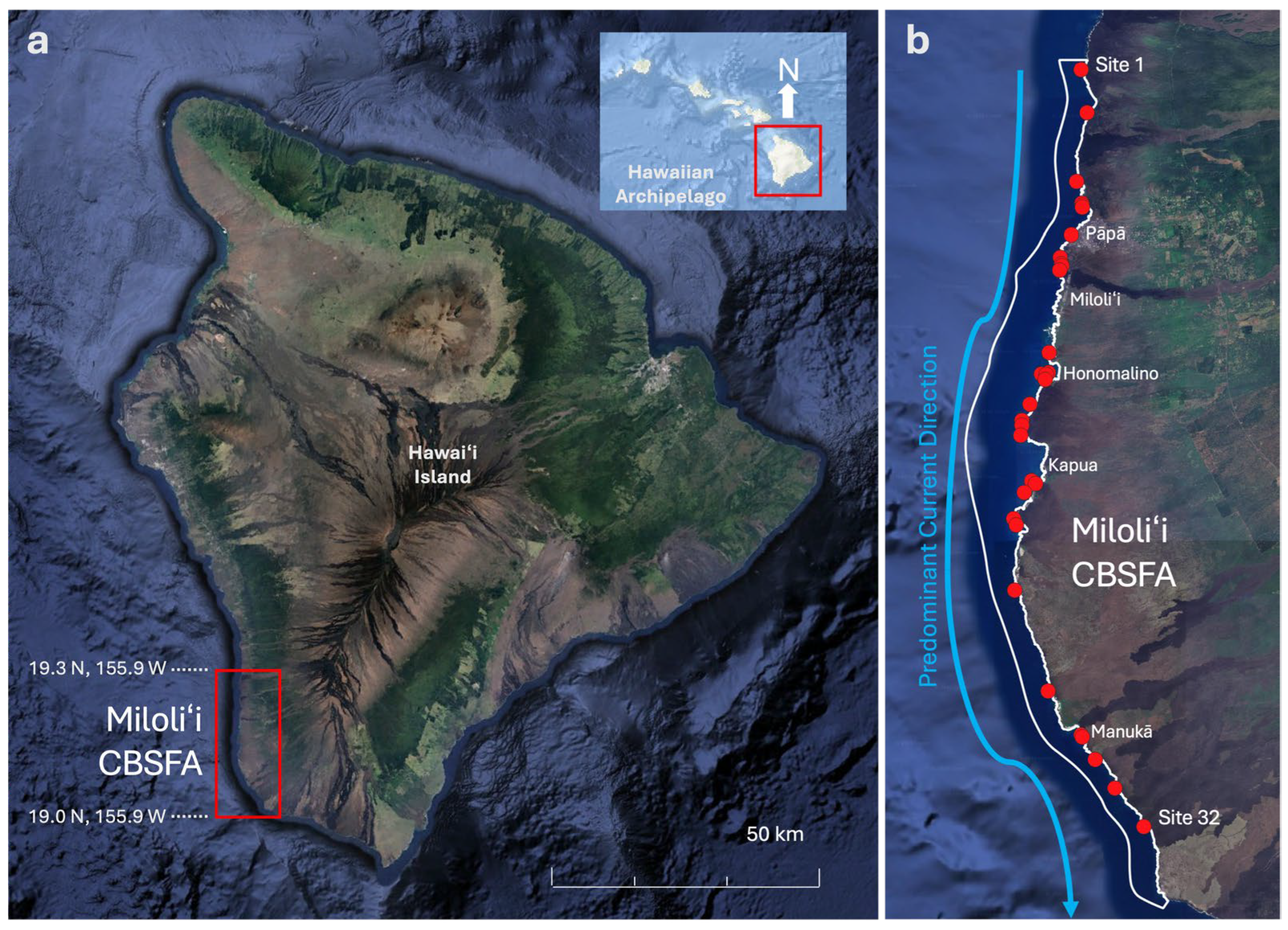

2. Materials and Methods

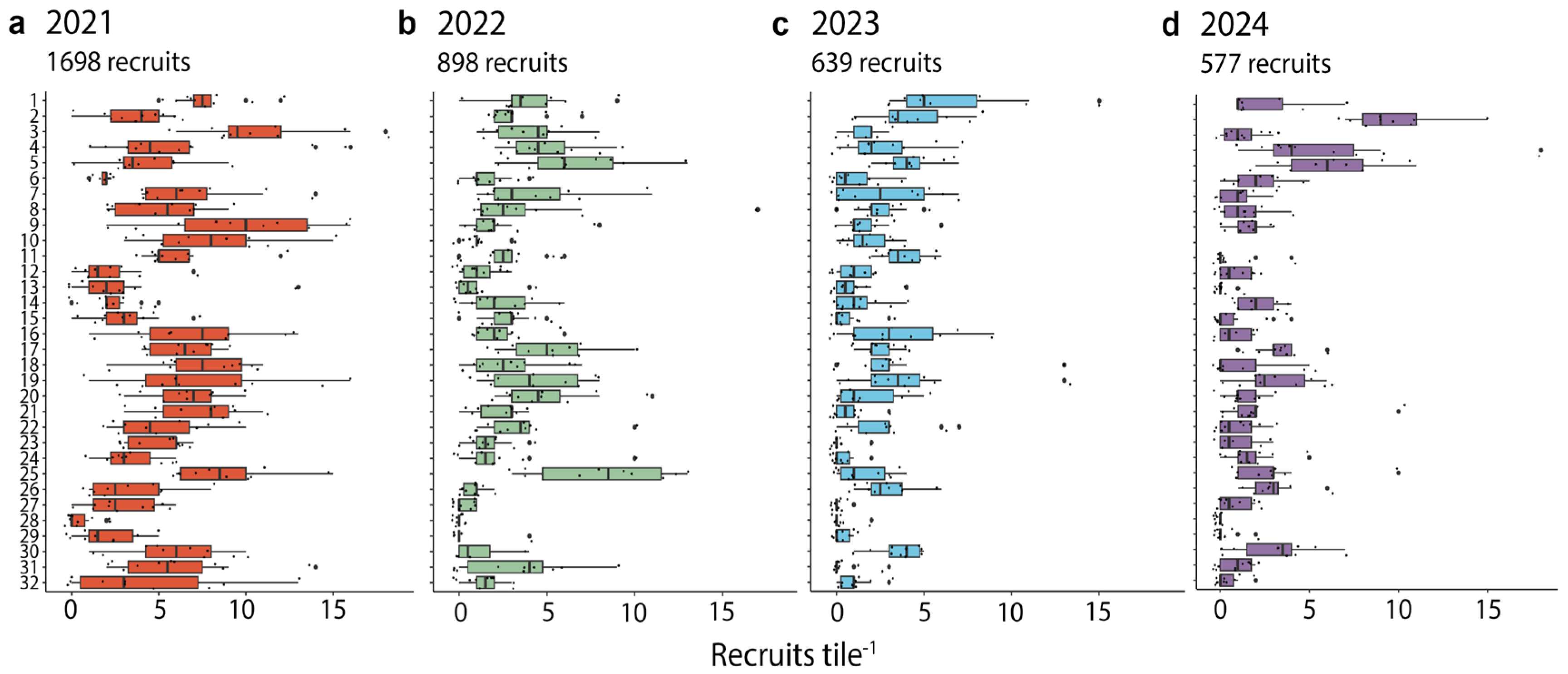

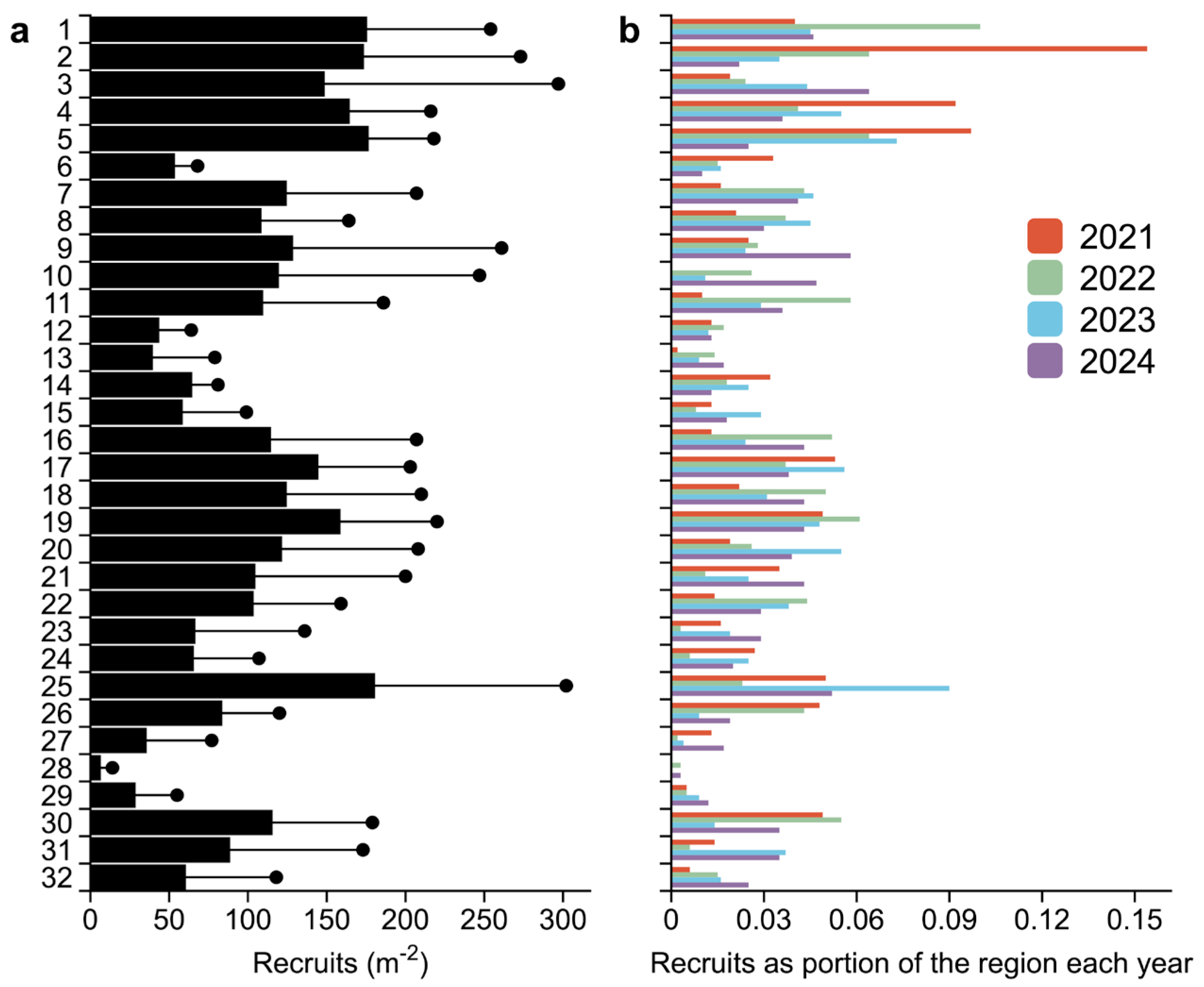

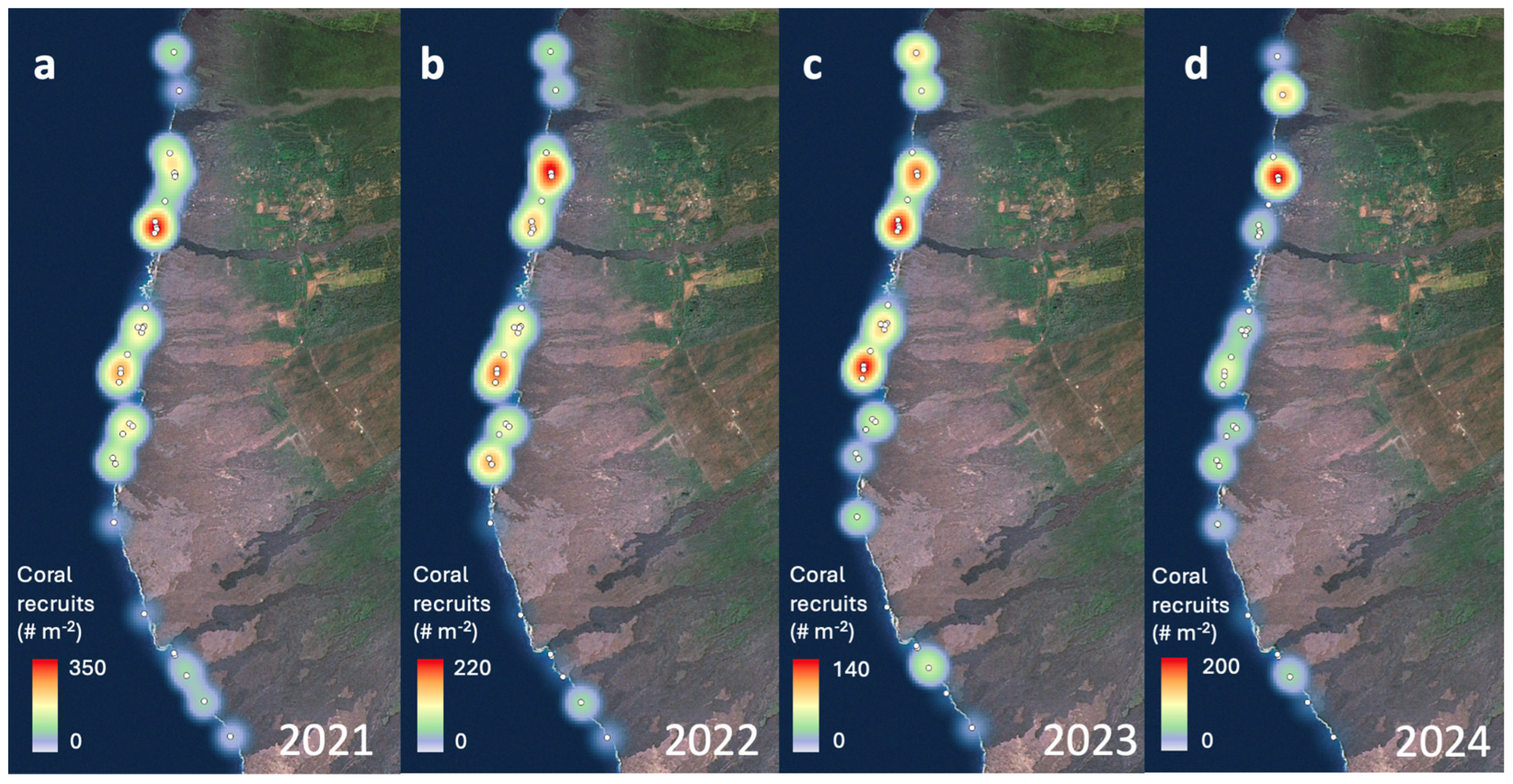

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Site | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 8 |

| 2 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| 3 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| 4 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| 6 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7 |

| 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 12 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 13 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 14 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| 15 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 16 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 6 |

| 17 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| 18 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 |

| 19 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 20 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| 21 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 22 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 23 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 6 |

| 24 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 25 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| 26 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 |

| 27 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 28 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

| 29 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 10 |

| 30 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 10 |

| 31 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 32 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

References

- Nativ, H.; Scucchia, F.; Martinez, S.; Einbinder, S.; Chequer, A.; Goodbody-Gringley, G.; Mass, T. In Situ Estimation of Coral Recruitment Patterns From Shallow to Mesophotic Reefs Using an Optimized Fluorescence Imaging System. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 709175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.L.; Wallace, C.C. Reproduction, Dispersal and Recruitment of Scleractinian Corals. In Coral Reefs; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; Volume 25, pp. 133–207. [Google Scholar]

- Stubler, A.D.; Stevens, A.K.; Peterson, B.J. Using Community-Wide Recruitment and Succession Patterns to Assess Sediment Stress on Jamaican Coral Reefs. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2016, 474, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Roach, S.; Johnston, E.; Fontana, S.; Jury, C.P.; Forsman, Z. Daytime Spawning of Pocillopora Species in Kaneohe Bay, Hawai‘i. Galaxea. J. Coral Reef Stud. 2014, 16, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenstein, M.A.; Gysbers, D.J.; Marhaver, K.L.; Kattom, S.; Tichy, L.; Quinlan, Z.; Tholen, H.M.; Wegley Kelly, L.; Vermeij, M.J.; Wagoner Johnson, A.J. Millimeter-Scale Topography Facilitates Coral Larval Settlement in Wave-Driven Oscillatory Flow. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guibert, I.; Hayden, R.; Sidobre, C.; Lecellier, G.; Berteaux-Lecellier, V. Effect of Coral-giant Clam Artificial Reef on Coral Recruitment: Insights for Restoration and Conservation Efforts. Restor. Ecol. 2024, 32, e14145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanovski, R.; Abelson, A. Structural Complexity Enhancement as a Potential Coral-Reef Restoration Tool. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 132, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, R.R.; Crowder, L.B.; Martin, R.E.; Asner, G.P. The Effect of Reef Morphology on Coral Recruitment at Multiple Spatial Scales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2311661121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botosoamananto, R.L.; Todinanahary, G.; Gasimandova, L.M.; Randrianarivo, M.; Guilhaumon, F.; Penin, L.; Adjeroud, M. Coral Recruitment in the Toliara Region of Southwest Madagascar: Spatio-Temporal Variability and Implications for Reef Conservation. Mar. Ecol. 2024, 45, e12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjeroud, M.; Penin, L.; Carroll, A. Spatio-Temporal Heterogeneity in Coral Recruitment around Moorea, French Polynesia: Implications for Population Maintenance. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2007, 341, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, E.; Marques da Silva, I.; Glassom, D. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Coral Recruitment at Vamizi Island, Quirimbas Archipelago, Mozambique. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2015, 37, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, D.P.; Babcock, R.C.; Evans, R.D.; Feng, M.; Moustaka, M.; Orr, M.; Slawinski, D.; Wilson, S.K.; Hoey, A.S. Coral Larval Recruitment in North-Western Australia Predicted by Regional and Local Conditions. Mar. Environ. Res. 2021, 168, 105318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjeroud, M.; Peignon, C.; Gauliard, C.; Penin, L.; Kayal, M. Extremely High but Localized Pulses of Coral Recruitment in the Southwestern Lagoon of New Caledonia and Implications for Conservation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2022, 692, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojis, B.L.; Quinn, N.J. The Importance of Regional Differences in Hard Coral Recruitment Rates for Determining the Need for Coral Restoration. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2001, 69, 967–974. [Google Scholar]

- Bak, R.; Meesters, E. Coral Population Structure: The Hidden Information of Colony Size-Frequency Distributions. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1998, 162, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjeroud, M.; Kayal, M.; Iborra-Cantonnet, C.; Vercelloni, J.; Bosserelle, P.; Liao, V.; Chancerelle, Y.; Claudet, J.; Penin, L. Recovery of Coral Assemblages despite Acute and Recurrent Disturbances on a South Central Pacific Reef. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmunds, P.J. Why Keep Monitoring Coral Reefs? BioScience 2024, 74, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, N.; Muko, S.; Legendre, L.; Steneck, R.; van Oppen, M.; Albright, R.; Ang, P.J.; Carpenter, R.; Chui, A.; Fan, T.; et al. Global Biogeography of Coral Recruitment: Tropical Decline and Subtropical Increase. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2019, 621, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, P.J. Recruitment Hotspots and Bottlenecks Mediate the Distribution of Corals on a Caribbean Reef. Biol. Lett. 2021, 17, 20210149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asner, G.P.; Vaughn, N.; Grady, B.W.; Foo, S.A.; Anand, H.; Carlson, R.R.; Shafron, E.; Teague, C.; Martin, R.E. Regional Reef Fish Survey Design and Scaling Using High-Resolution Mapping and Analysis. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 683184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong-Ala, J.A.; Comfort, C.M.; Gove, J.M.; Hixon, M.A.; McManus, M.A.; Powell, B.S.; Whitney, J.L.; Neuheimer, A.B. How Life History Characteristics and Environmental Forcing Shape Settlement Success of Coral Reef Fishes. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abecassis, M.; Polovina, J.; Baird, R.W.; Copeland, A.; Drazen, J.C.; Domokos, R.; Oleson, E.; Jia, Y.; Schorr, G.S.; Webster, D.L.; et al. Characterizing a Foraging Hotspot for Short-Finned Pilot Whales and Blainville’s Beaked Whales Located off the West Side of Hawai‘i Island by Using Tagging and Oceanographic Data. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukunaga, A.; Asner, G.P.; Grady, B.W.; Vaughn, N.R. Fish Assemblage Structure, Diversity and Controls on Reefs of South Kona, Hawaiʻi Island. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gove, J.M.; Williams, G.J.; Lecky, J.; Brown, E.; Conklin, E.; Counsell, C.; Davis, G.; Donovan, M.K.; Falinski, K.; Kramer, L.; et al. Coral Reefs Benefit from Reduced Land–Sea Impacts under Ocean Warming. Nature 2023, 621, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, D.; Stephens, T.G.; Tinoco, A.I.; Richmond, R.H.; Cleves, P.A. Life on the Edge: Hawaiian Model for Coral Evolution. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2022, 67, 1976–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Gamiño, J.L.; Gates, R.D. Spawning Dynamics in the Hawaiian Reef-Building Coral Montipora Capitata. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012, 449, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideout, J.R.; Bolyen, E.; McDonald, D.; Baeza, Y.V.; Alastuey, J.C.; Pitman, A.; Morton, J.; Zhu, Q.; Navas, J.; Gorlick, K.; et al. Scikit-Bio/Scikit-Bio: Scikit-Bio 0.7.0; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, J.L.; Gove, J.M.; McManus, M.A.; Smith, K.A.; Lecky, J.; Neubauer, P.; Phipps, J.E.; Contreras, E.A.; Kobayashi, D.R.; Asner, G.P. Surface Slicks Are Pelagic Nurseries for Diverse Ocean Fauna. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asner, G.P.; Vaughn, N.R.; Heckler, J.; Knapp, D.E.; Balzotti, C.; Shafron, E.; Martin, R.E.; Neilson, B.J.; Gove, J.M. Large-Scale Mapping of Live Corals to Guide Reef Conservation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 33711–33718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, M.; Oliver, T.; Couch, C.; Donovan, M.K.; Asner, G.P.; Conklin, E.; Fuller, K.; Grady, B.W.; Huntington, B.; Kageyama, K.; et al. Coral Taxonomy and Local Stressors Drive Bleaching Prevalence across the Hawaiian Archipelago in 2019. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asner, G.P.; Vaughn, N.R.; Martin, R.E.; Foo, S.A.; Heckler, J.; Neilson, B.J.; Gove, J.M. Mapped Coral Mortality and Refugia in an Archipelago-Scale Marine Heat Wave. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2123331119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, E.C.; Counsell, C.W.; Sale, T.L.; Burgess, S.C.; Toonen, R.J. The Legacy of Stress: Coral Bleaching Impacts Reproduction Years Later. Funct. Ecol. 2020, 34, 2315–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, P.J. Spatiotemporal Variation in Coral Recruitment and Its Association with Seawater Temperature. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2021, 66, 1394–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA (NCEI) Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) 2025. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/pdo/ (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Li, X.; Hu, Z.; McPhaden, M.J.; Zhu, C.; Liu, Y. Triple-dip La Niñas in 1998–2001 and 2020–2023: Impact of Mean State Changes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2023JD038843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, J.; Daly, J.; Zuchowicz, N.; Lager, C.; Henley, E.M.; Quinn, M.; Hagedorn, M. Solar Radiation, Temperature and the Reproductive Biology of the Coral Lobactis Scutaria in a Changing Climate. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokiel, P.L.; Coles, S.L. Effects of Temperature on the Mortality and Growth of Hawaiian Reef Corals. Mar. Biol. 1977, 43, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokiel, P.L.; Guinther, E.B. Effects of Temperature on Reproduction in the Hermatypic Coral Pocillopora Damicornis. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1978, 28, 786–789. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, C.H. The Ecology of an Hawaiian Coral Reef; The Bernice P. Bishop Museum: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1928; Volume 45. [Google Scholar]

- Henley, E.M.; Quinn, M.; Bouwmeester, J.; Daly, J.; Zuchowicz, N.; Lager, C.; Bailey, D.W.; Hagedorn, M. Reproductive Plasticity of Hawaiian Montipora Corals Following Thermal Stress. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Installation | Removal | Days Deployed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 16 April | 29 September | 166 |

| 2022 | 6 May | 8 December | 216 |

| 2023 | 10 April | 15 November | 219 |

| 2024 | 15 April | 15 April 2025 | 365 |

| Year | 5 m Depth | 10 m Depth |

|---|---|---|

| Annual | ||

| 2021 | 26.4|0.8|24.6|28.1 | 26.4|0.8|24.5|28.0 |

| 2022 | 26.2|0.9|24.6|28.1 | 26.2|0.8|24.0|28.1 |

| 2023 | 26.1|0.8|23.8|28.2 | 26.1|0.8|23.6|27.8 |

| 2024 | 26.0|0.9|23.9|28.2 | 25.9|0.8|23.5|27.9 |

| Spawning Season | ||

| 2021 | 26.5|0.7|24.7|28.1 | 26.4|0.6|23.8|28.0 |

| 2022 | 26.4|0.6|25.1|28.1 | 26.3|0.6|24.9|27.6 |

| 2023 | 26.3|0.5|25.4|28.1 | 26.2|0.5|25.2|27.7 |

| 2024 | 26.2|0.7|24.8|27.7 | 26.1|0.6|24.7|27.6 |

| Genus | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porites | 588 (34.9%) | 279 (31.1%) | 207 (32.4%) | 331 (57.5%) |

| Pocillopora | 817 (48.4%) | 448 (49.9%) | 264 (41.4%) | 212 (36.8%) |

| Montipora | 281 (16.7%) | 171 (19.0%) | 168 (26.2%) | 33 (5.7%) |

| PERMANOVA | ||||

| Recruits | Term | n | Pseudo F | p Value |

| Total | Year | 1226 | −1.51 × 103 | 1.00 |

| Total | Site | 1226 | 13.01 | <0.01 |

| Total | Year × Site | 1226 | 7.53 | <0.01 |

| Genus | Year | 948 | 15.34 | <0.01 |

| Genus | Site | 948 | 2.7 | <0.01 |

| Genus | Year × Site | 948 | 2.63 | <0.01 |

| Montipora | Site | 1226 | 3.67 | <0.01 |

| Montipora | Year | 1226 | 1.51 × 10−13 | 1.00 |

| Montipora | Year × Site | 1226 | 2.73 | <0.01 |

| Pocillopora | Site | 1226 | 12.01 | <0.01 |

| Pocillopora | Year | 1226 | −2.27 × 10−13 | 1.00 |

| Pocillopora | Year × Site | 1226 | 5.97 | <0.01 |

| Porites | Site | 1226 | 6.84 | <0.01 |

| Porites | Year | 1226 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Porites | Year × Site | 1226 | 4.60 | <0.01 |

| Mantel Test | ||||

| Recruits | Year-1 | Year-2 | Mantel r | p value |

| Total | 2021 | 2022 | 0.16 | <0.01 |

| Total | 2021 | 2023 | 0.12 | 0.02 |

| Total | 2021 | 2024 | 0.02 | 0.70 |

| Total | 2022 | 2023 | 0.14 | 0.02 |

| Total | 2022 | 2024 | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| Total | 2023 | 2024 | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| Genus | 2021 | 2022 | 0.01 | 0.96 |

| Genus | 2021 | 2023 | 0.09 | 0.31 |

| Genus | 2021 | 2024 | 0.04 | 0.60 |

| Genus | 2022 | 2023 | 0.09 | 0.31 |

| Genus | 2022 | 2024 | 0.03 | 0.74 |

| Genus | 2023 | 2024 | 0.09 | 0.30 |

| Spearman’s Rank Correlation | ||||

| Recruits | Year-1 | Year-2 | rho | p value |

| Total | 2021 | 2022 | 0.54 | <0.01 |

| Total | 2021 | 2023 | 0.46 | <0.01 |

| Total | 2021 | 2024 | 0.35 | 0.05 |

| Total | 2022 | 2023 | 0.5 | <0.01 |

| Total | 2022 | 2024 | 0.56 | <0.01 |

| Total | 2023 | 2024 | 0.53 | <0.01 |

| Total | All years | All years | 0.76 | <0.01 |

| Genus | 2021 | 2022 | 0.97 | <0.01 |

| Genus | 2021 | 2023 | 0.97 | <0.01 |

| Genus | 2021 | 2024 | 0.87 | 0.05 |

| Genus | 2022 | 2023 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| Genus | 2022 | 2024 | 0.89 | 0.04 |

| Genus | 2023 | 2024 | 0.89 | 0.04 |

| Genus | All years | All years | 0.59 | 0.04 |

| Montipora | 2021 | 2022 | 0.33 | 0.07 |

| Montipora | 2021 | 2023 | 0.37 | 0.04 |

| Montipora | 2021 | 2024 | 0.05 | 0.81 |

| Montipora | 2022 | 2023 | −0.06 | 0.76 |

| Montipora | 2022 | 2024 | 0.35 | 0.05 |

| Montipora | 2023 | 2024 | 0.11 | 0.55 |

| Montipora | All years | All years | 0.19 | 0.04 |

| Pocillopora | 2021 | 2022 | 0.66 | <0.01 |

| Pocillopora | 2021 | 2023 | 0.64 | <0.01 |

| Pocillopora | 2021 | 2024 | 0.34 | 0.06 |

| Pocillopora | 2022 | 2023 | 0.55 | <0.01 |

| Pocillopora | 2022 | 2024 | 0.59 | <0.01 |

| Pocillopora | 2023 | 2024 | 0.40 | 0.02 |

| Pocillopora | All years | All years | 0.53 | <0.01 |

| Porites | 2021 | 2022 | 0.26 | 0.15 |

| Porites | 2021 | 2023 | 0.18 | 0.31 |

| Porites | 2021 | 2024 | 0.11 | 0.56 |

| Porites | 2022 | 2023 | 0.36 | 0.04 |

| Porites | 2022 | 2024 | 0.40 | 0.02 |

| Porites | 2023 | 2024 | 0.48 | <0.01 |

| Porites | All years | All years | 0.30 | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asner, G.P.; Carlson, R.R.; Labo, C.; Harrison, D.E.; Martin, R.E. Persistent Geographic Patterns of Coral Recruitment in Hawaiʻi. Oceans 2025, 6, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040080

Asner GP, Carlson RR, Labo C, Harrison DE, Martin RE. Persistent Geographic Patterns of Coral Recruitment in Hawaiʻi. Oceans. 2025; 6(4):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040080

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsner, Gregory P., Rachel R. Carlson, Caleb Labo, Dominica E. Harrison, and Roberta E. Martin. 2025. "Persistent Geographic Patterns of Coral Recruitment in Hawaiʻi" Oceans 6, no. 4: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040080

APA StyleAsner, G. P., Carlson, R. R., Labo, C., Harrison, D. E., & Martin, R. E. (2025). Persistent Geographic Patterns of Coral Recruitment in Hawaiʻi. Oceans, 6(4), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040080