Role of Lee Wave Turbulence in the Dispersion of Sediment Plumes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

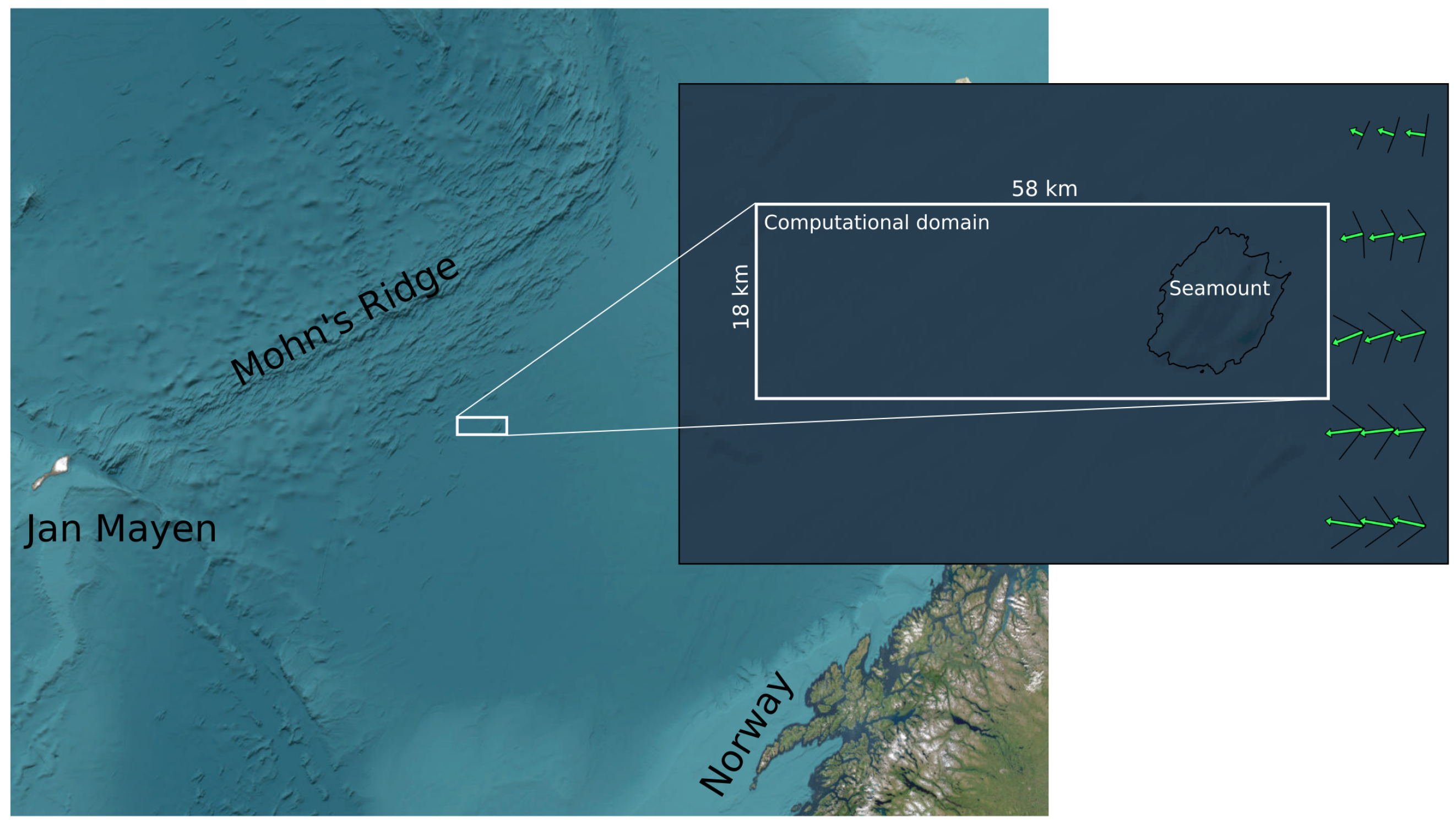

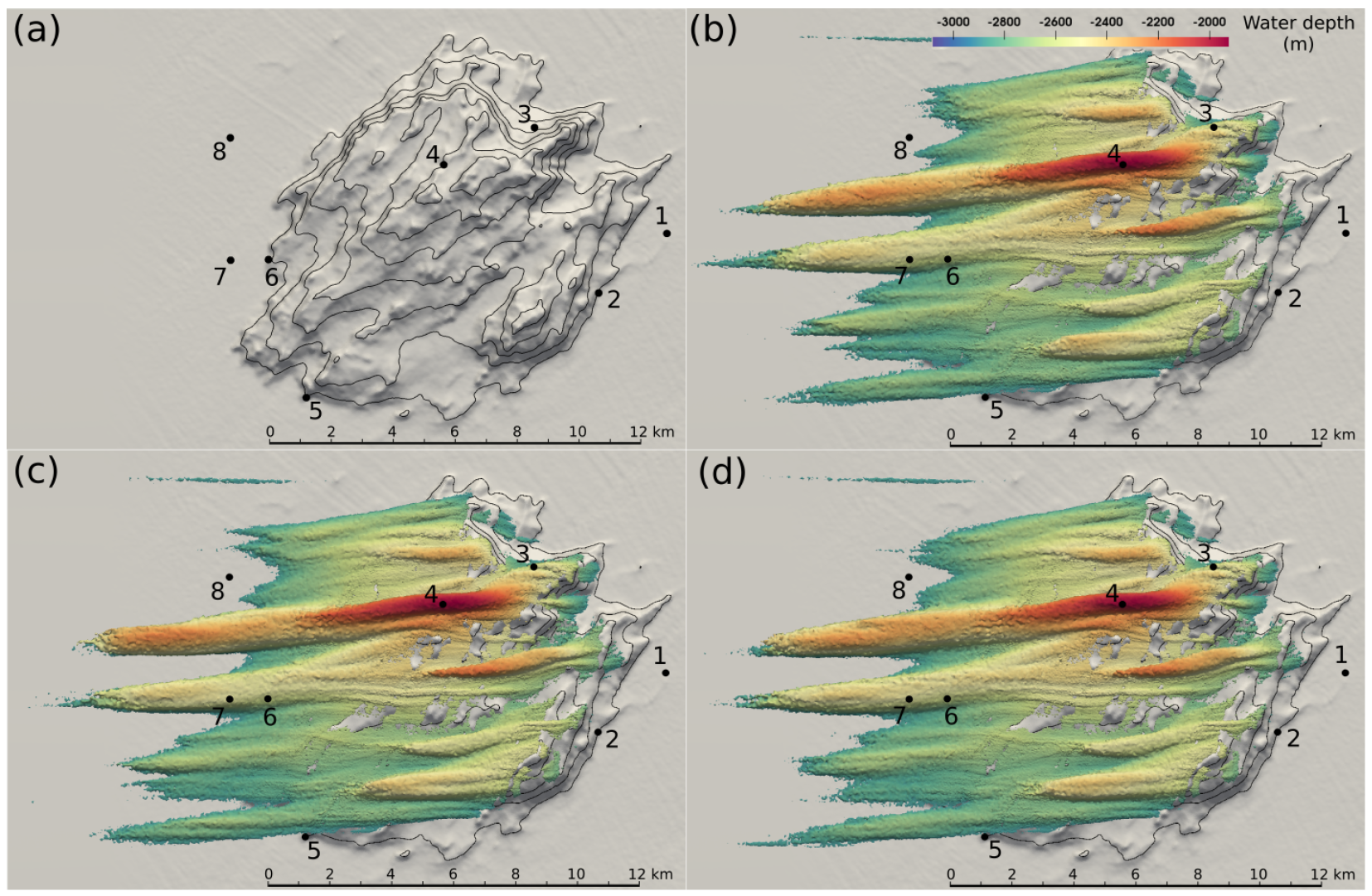

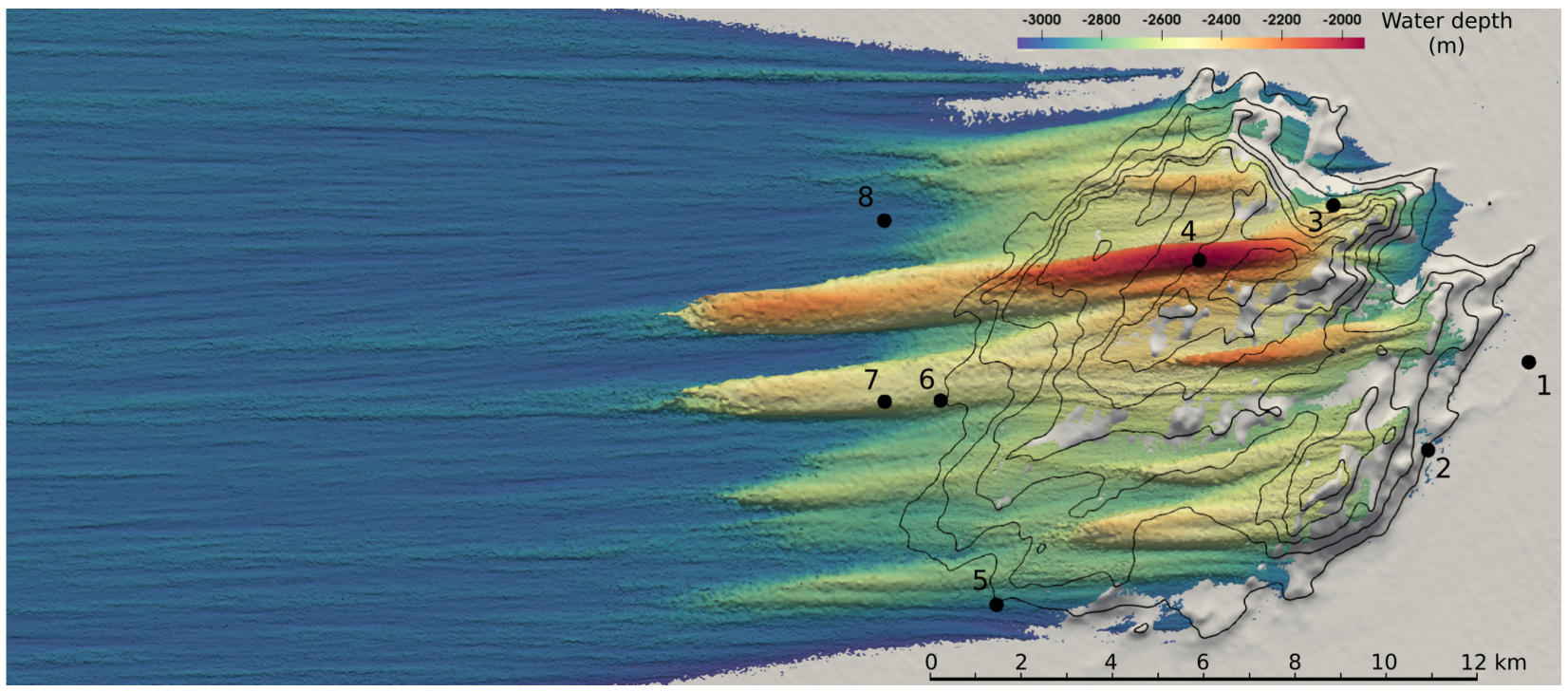

2.1. Region of Interest and Ocean Data

2.2. Numerical Model

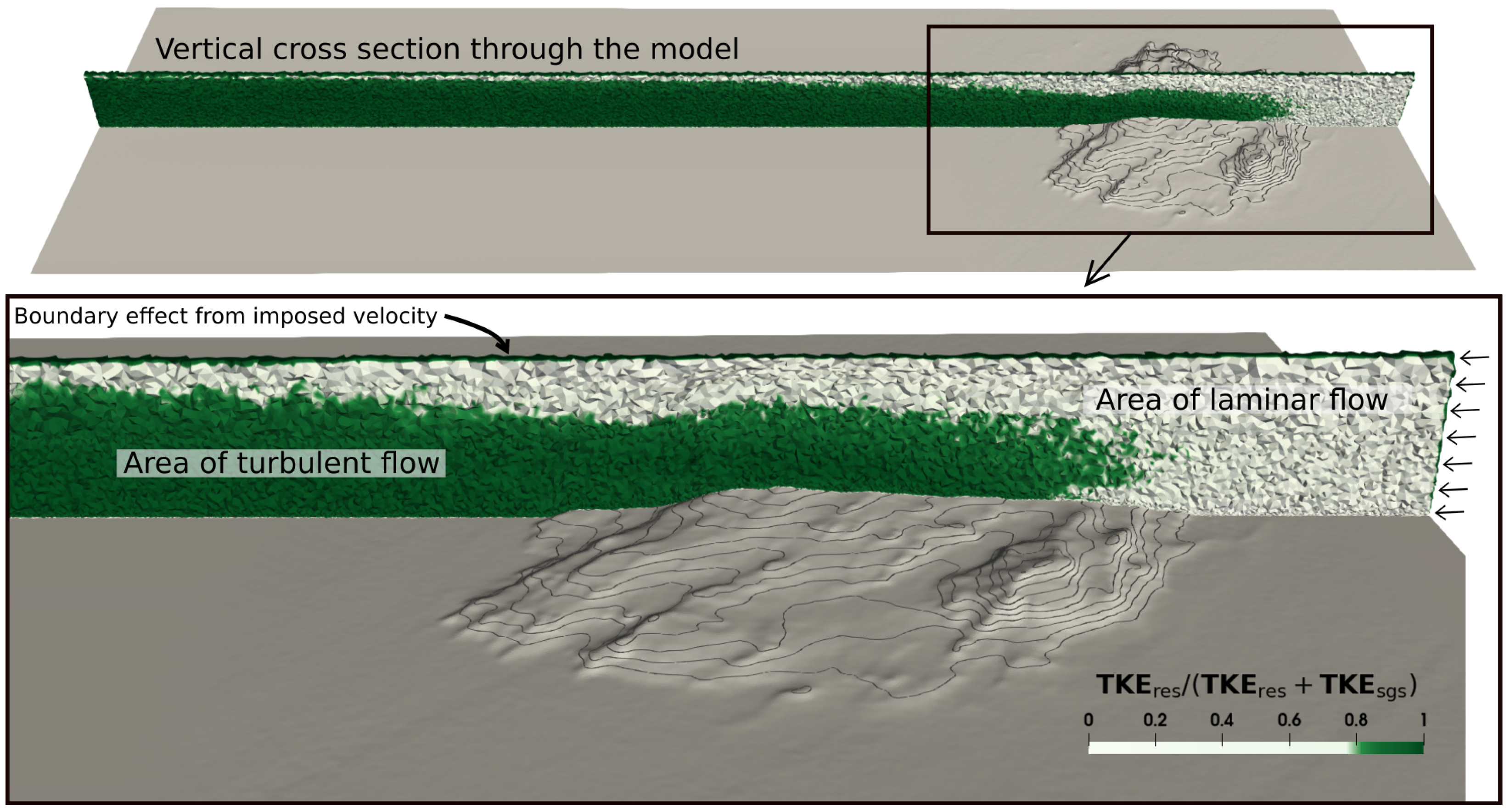

2.2.1. Large Eddy Simulation

2.2.2. Geometry and Mesh

2.2.3. Initial and Boundary Conditions

2.2.4. Reynolds Number

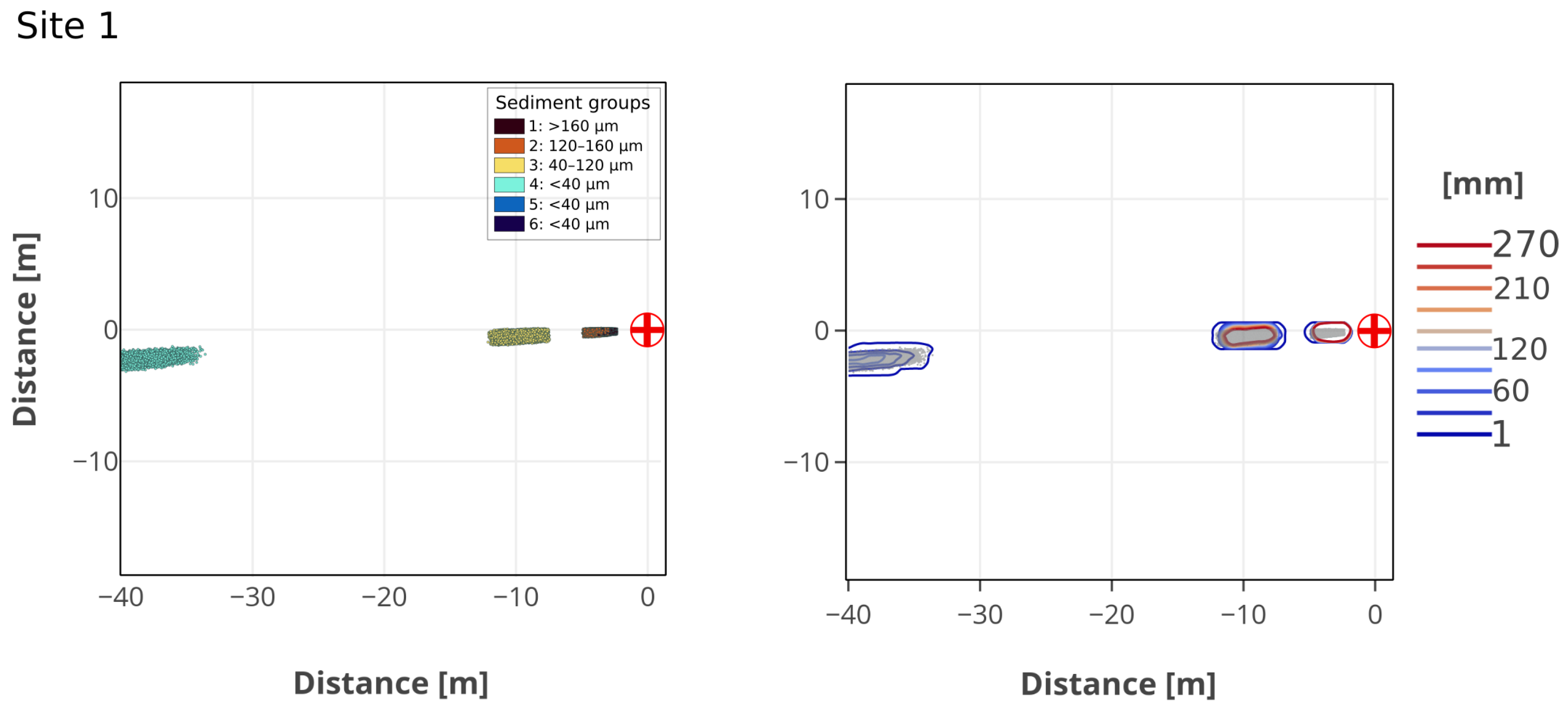

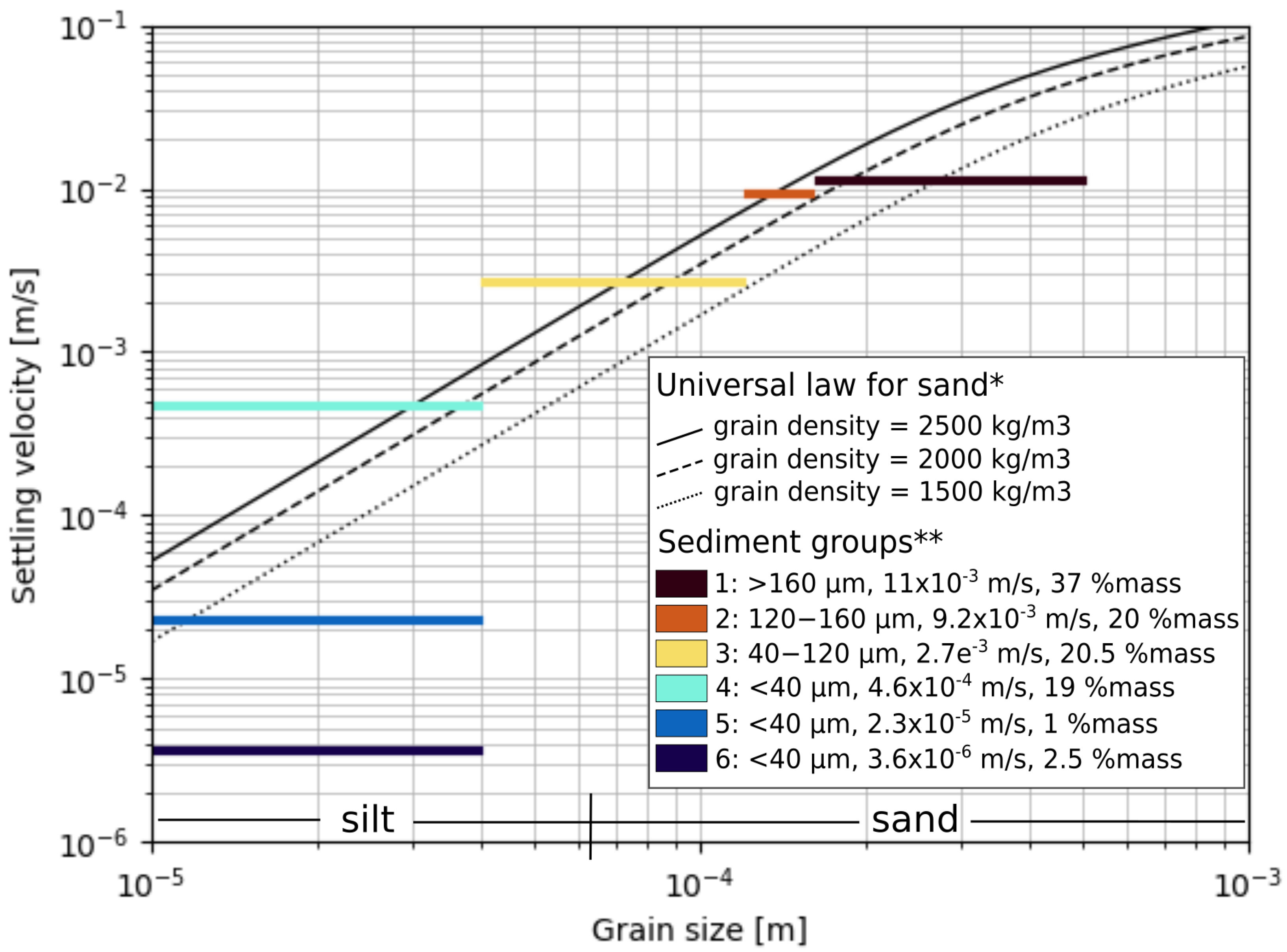

2.3. Particle Settling Model

3. Results

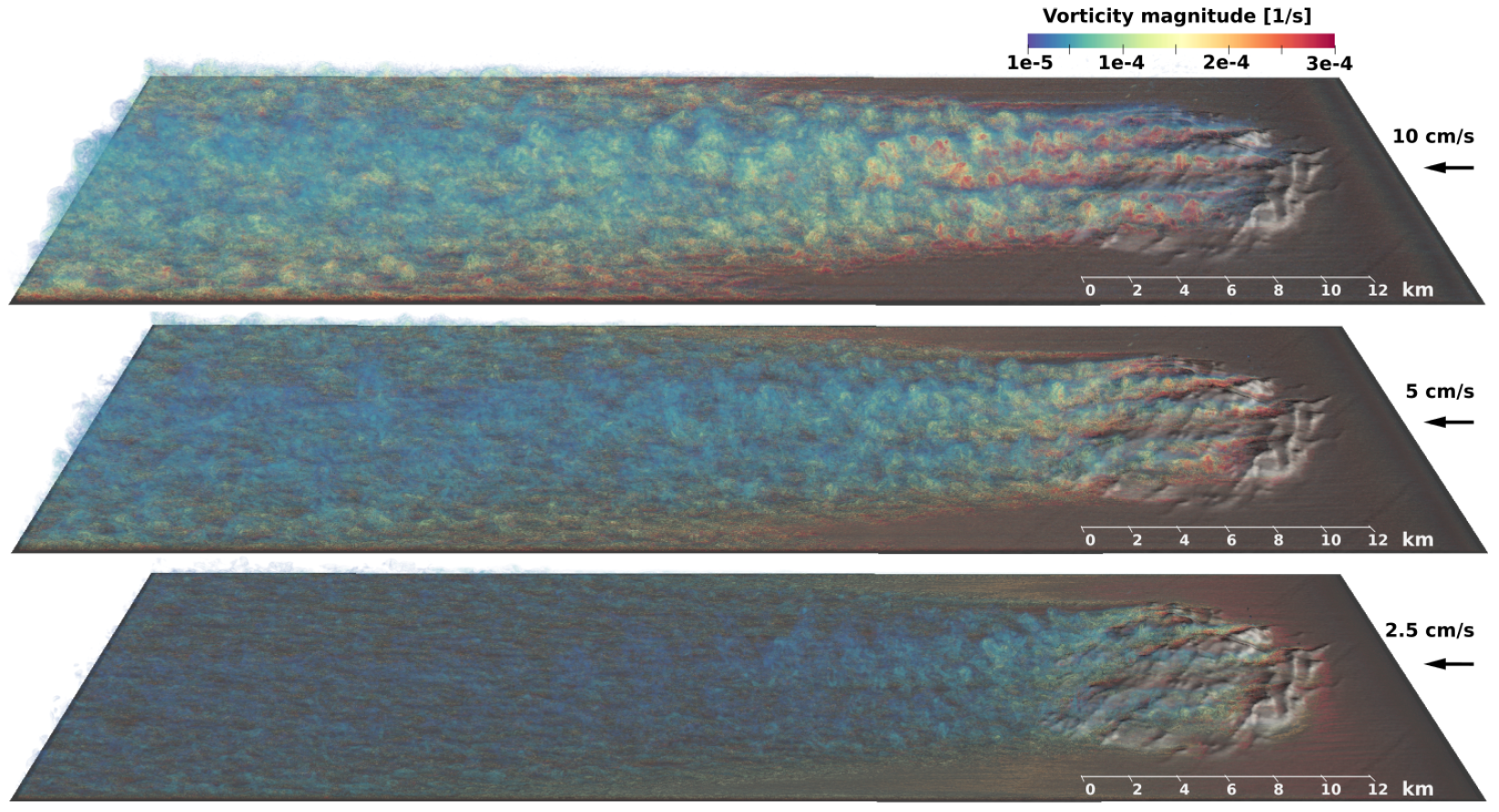

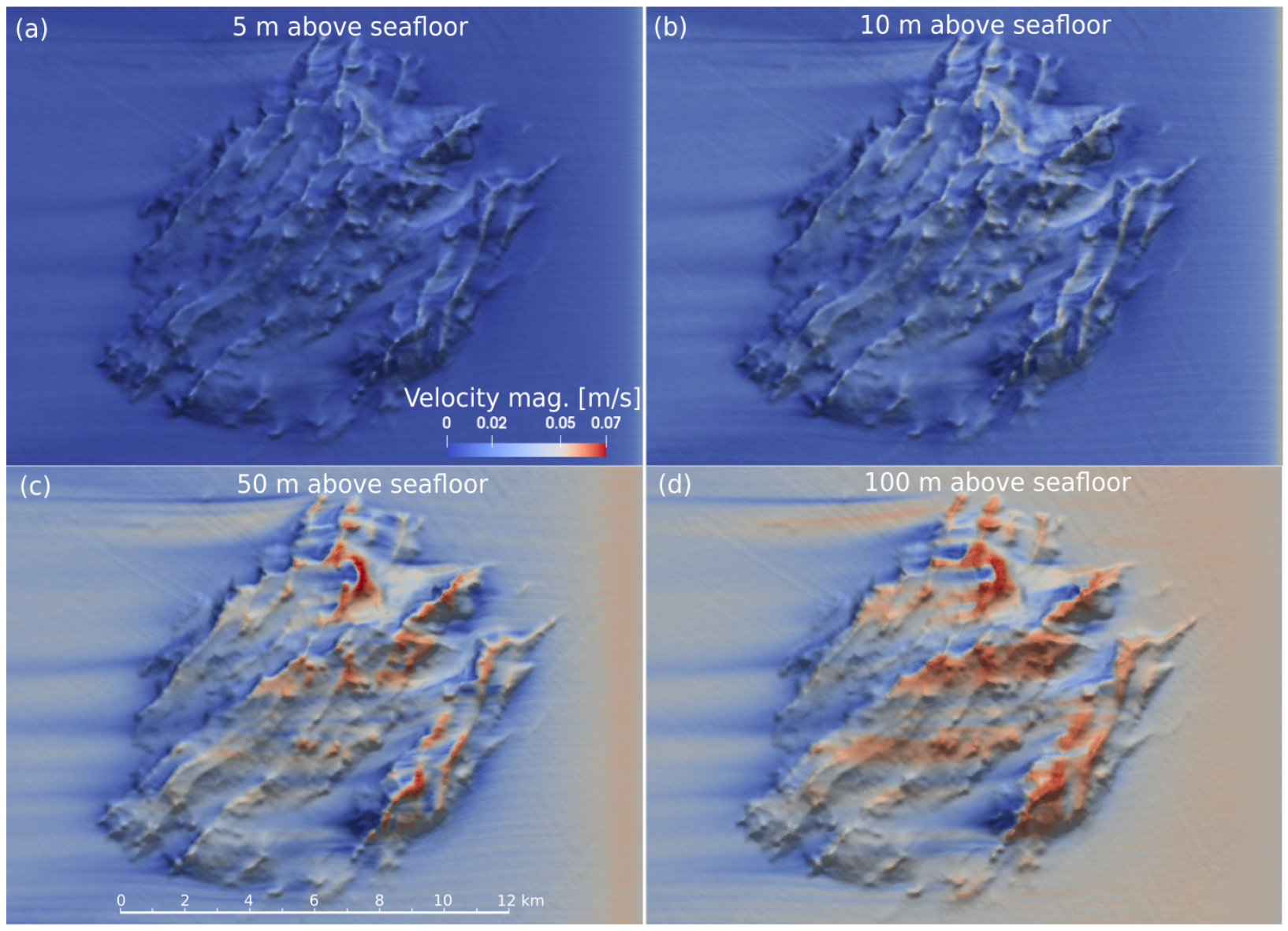

3.1. Turbulent Flow

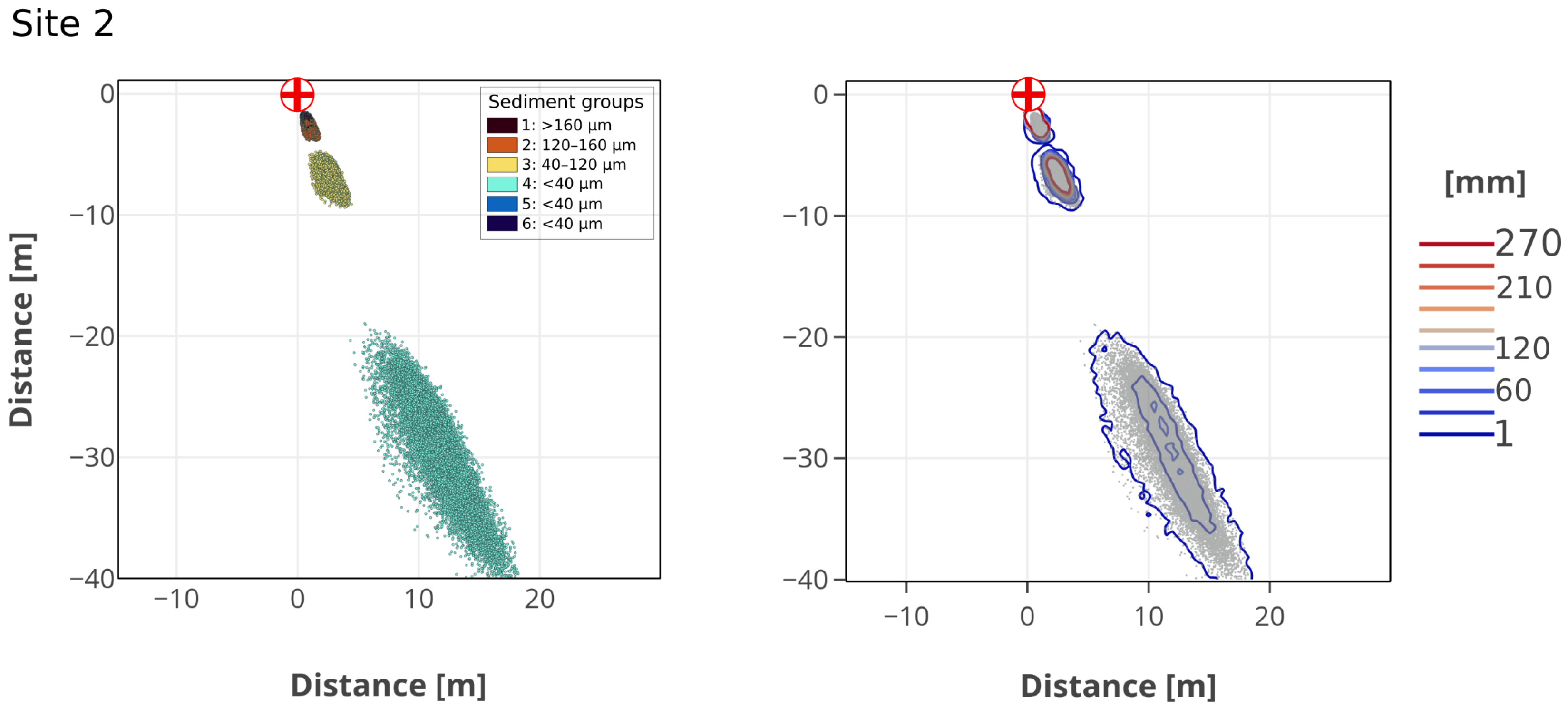

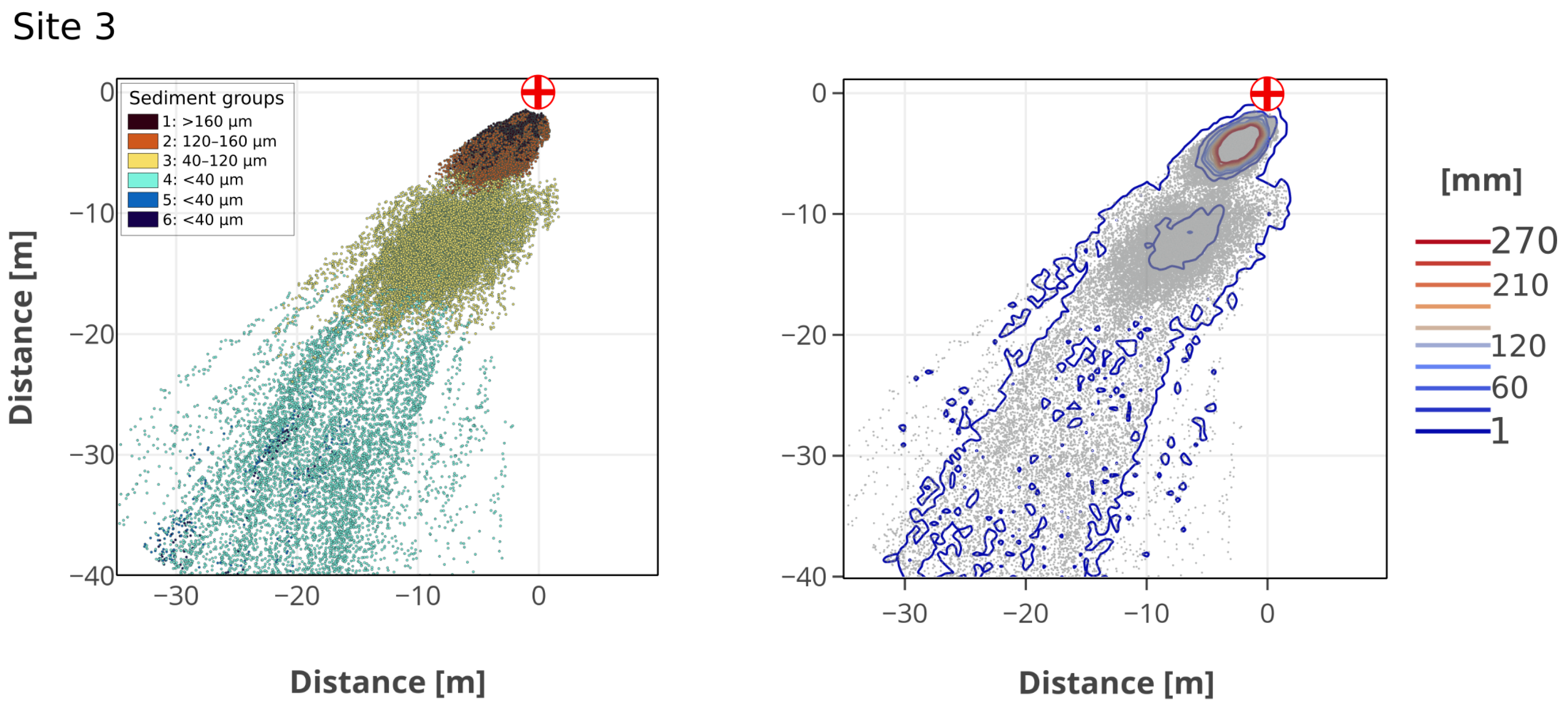

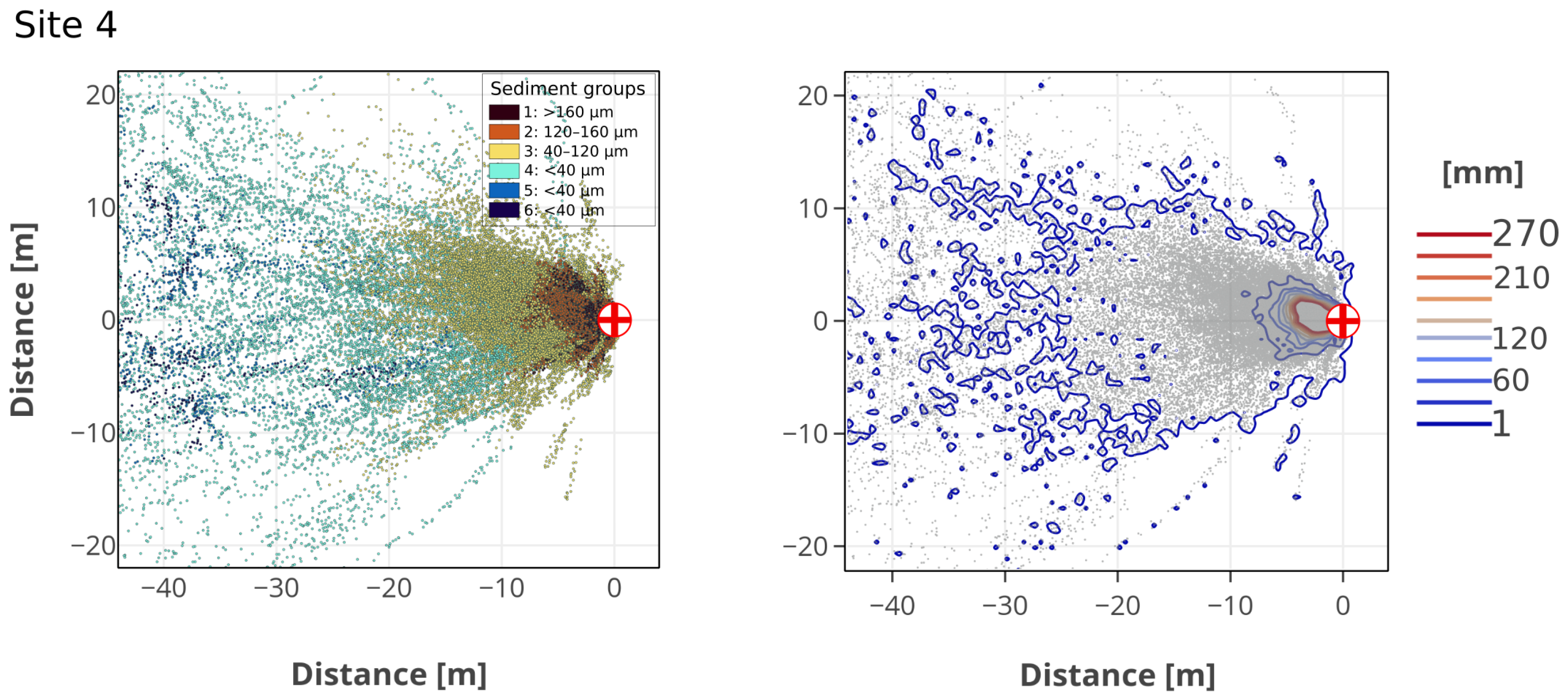

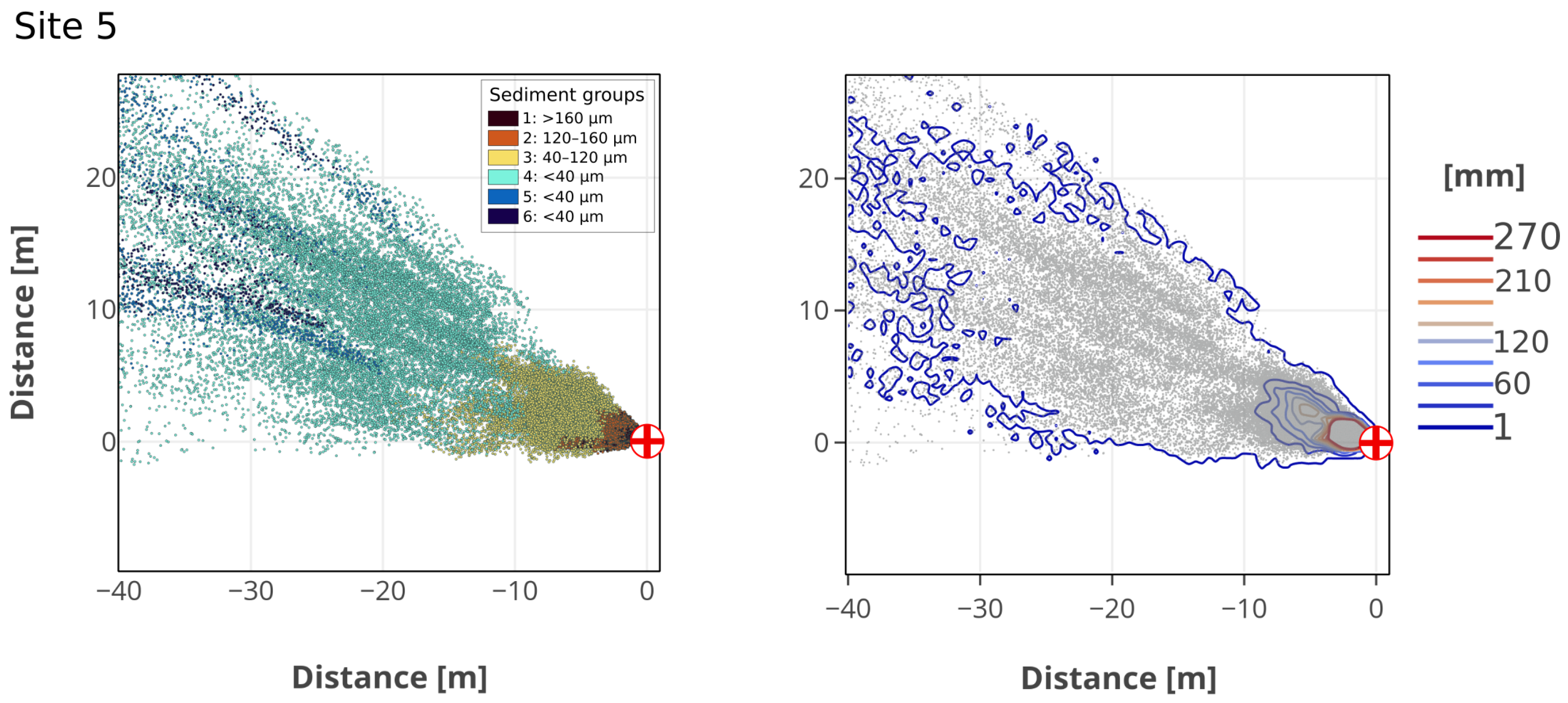

3.2. Particle Spreading

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Lee Wave Dynamics

4.2. Sediment Interactions with Turbulence

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Water density | |

| Water dynamic viscosity | |

| Time steps | for inlet velocity scenario of |

| for inlet velocity scenario of | |

| for inlet velocity scenario of | |

| Smagorinsky constant |

References

- Jones, D.O.B.; Kaiser, S.; Sweetman, A.K.; Smith, C.R.; Menot, L.; Vink, A.; Trueblood, D.; Greinert, J.; Billett, D.S.M.; Arbizu, P.M. Biological responses to disturbance from simulated deep-sea polymetallic nodule mining. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, J.A.; Zielke, W. The mesoscale sediment transport due to technical activities in the deep sea. Deep. Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2001, 48, 3487–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Royo, C.; Ouillon, R.; El Mousadik, S.; Alford, M.H.; Peacock, T. An in situ study of abyssal turbidity-current sediment plumes generated by a deep seabed polymetallic nodule mining preprototype collector vehicle. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouillon, R.; Meiburg, E.; Ouellette, N.T.; Koseff, J.R. Interaction of a downslope gravity current with an internal wave. J. Fluid Mech. 2019, 873, 889–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouillon, R.; Kakoutas, C.; Meiburg, E.; Peacock, T. Gravity currents from moving sources. J. Fluid Mech. 2021, 924, A43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, T.; Ouillon, R. The Fluid Mechanics of Deep-Sea Mining. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2023, 55, 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazis, I.Z.; de Stigter, H.; Mohrmann, J.; Heger, K.; Diaz, M.; Gillard, B.; Baeye, M.; Veloso-Alarcón, M.E.; Purkiani, K.; Haeckel, M.; et al. Monitoring benthic plumes, sediment redeposition and seafloor imprints caused by deep-sea polymetallic nodule mining. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleynik, D.; Inall, M.E.; Dale, A.; Vink, A. Impact of remotely generated eddies on plume dispersion at abyssal mining sites in the Pacific. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, J.W.; Mohn, C. Motion, commotion, and biophysical connections at deep ocean seamounts. Oceanography 2010, 23, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, T.C. Ocean eddies generated by seamounts in the North Pacific. Science 1978, 199, 1063–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chapman, D.C.; Haidvogel, D.B. Formation of Taylor caps over a tall isolated seamount in a stratified ocean. Geophys. Astrophys. Fluid Dyn. 1992, 64, 31–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shank, T.M. Seamounts: Deep-ocean laboratories of faunal connectivity, evolution, and endemism. Oceanography 2010, 23, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldner, D.R.; Chapman, D.C. Flow and particle motion induced above a tall seamount by steady and tidal background currents. Deep. Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1997, 44, 719–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, M.H.; Girton, J.B.; Voet, G.; Carter, G.S.; Mickett, J.B.; Klymak, J.M. Turbulent mixing and hydraulic control of abyssal water in the Samoan Passage. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 4668–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, J.; Naveira Garabato, A.; Smeed, D.; Girton, J. Observation of a large lee wave in the Drake Passage. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2017, 47, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Haren, H. Abyssal plain hills and internal wave turbulence. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 4387–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfect, B.; Kumar, N.; Riley, J.J. Energetics of seamount wakes. Part I: Energy exchange. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2020, 50, 1365–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, J.A.; Zhao, Z.; Whalen, C.B.; Waterhouse, A.F.; Trossman, D.S.; Sun, O.M.; Laurent, L.C.S.; Simmons, H.L.; Polzin, K.; Pinkel, R. Climate process team on internal wave–driven ocean mixing. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 98, 2429–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voet, G.; Quadfasel, D.; Mork, K.A.; Søiland, H. The mid-depth circulation of the Nordic Seas derived from profiling float observations. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 2010, 62, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosse, A.; Fer, I. Mean structure and seasonality of the Norwegian Atlantic Front Current along the Mohn Ridge from repeated glider transects. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 13170–13179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Marine Data Store. Global Ocean Physical Analysis and Forecasting; Product GLOBAL_ANALYSISFORECAST_PHY_00-1_024; Copernicus: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bø, J.; Bergersen, A.; Valen-Sendstad, K.; Mortensen, M. Implementation, Verification and Validation of Large Eddy Simulation Models in Oasis. In Proceedings of the MekIT’15 Eighth National Conference on Computational Mechanics, Trondheim, Norway, 18–19 May 2015; Skallerud, B.H., Andersson, H.I., Eds.; CIMNE: Barcelona, Spain, 2015; pp. 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Canuto, V.M.; Cheng, Y. Determination of the Smagorinsky–Lilly constant CS. Phys. Fluids 1997, 9, 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, M.; Valen-Sendstad, K. Oasis: A high-level/high-performance open source Navier–Stokes solver. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2015, 188, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, S.B. Ten questions concerning the large-eddy simulation of turbulent flows. New J. Phys. 2004, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansley, C.E.; Marshall, D.P. Flow past a cylinder on a β plane, with application to Gulf Stream separation and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2001, 31, 3274–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; McWilliams, J.C.; Shchepetkin, A.F. Island wakes in deep water. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2007, 37, 962–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, J.; Taylor, J.; Crossouard, N.; Cooper, A.; Turnbull, M.; Manning, A.; Lee, M.; Murton, B. Measurement and modelling of deep sea sediment plumes and implications for deep sea mining. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soulsby, R.L. Dynamics of marine sands: A manual for practical applications. Oceanogr. Lit. Rev. 1997, 9, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillard, B.; Purkiani, K.; Chatzievangelou, D.; Vink, A.; Iversen, M.H.; Thomsen, L. Physical and hydrodynamic properties of deep sea mining-generated, abyssal sediment plumes in the Clarion Clipperton Fracture Zone (eastern-central Pacific). Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2019, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentworth, C.K. A scale of grade and class terms for clastic sediments. J. Geol. 1922, 30, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elerian, M.; Huang, Z.; van Rhee, C.; Helmons, R. Flocculation effect on turbidity flows generated by deep-sea mining: A numerical study. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 277, 114250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman-Roisin, B.; Beckers, J.M. Introduction to Geophysical Fluid Dynamics: Physical and Numerical Aspects; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 101. [Google Scholar]

- Vic, C.; Naveira Garabato, A.C.; Green, J.M.; Waterhouse, A.F.; Zhao, Z.; Melet, A.; De Lavergne, C.; Buijsman, M.C.; Stephenson, G.R. Deep-ocean mixing driven by small-scale internal tides. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Souche, A.; Hartz, E.H.; Rüpke, L.H.; Schmid, D.W. Role of Lee Wave Turbulence in the Dispersion of Sediment Plumes. Oceans 2025, 6, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040077

Souche A, Hartz EH, Rüpke LH, Schmid DW. Role of Lee Wave Turbulence in the Dispersion of Sediment Plumes. Oceans. 2025; 6(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040077

Chicago/Turabian StyleSouche, Alban, Ebbe H. Hartz, Lars H. Rüpke, and Daniel W. Schmid. 2025. "Role of Lee Wave Turbulence in the Dispersion of Sediment Plumes" Oceans 6, no. 4: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040077

APA StyleSouche, A., Hartz, E. H., Rüpke, L. H., & Schmid, D. W. (2025). Role of Lee Wave Turbulence in the Dispersion of Sediment Plumes. Oceans, 6(4), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040077