1. Introduction

Implant-supported prosthetic restorations are widely used to manage partial edentulism and multiple tooth loss. Their long-term success depends, among other factors, on achieving passive fit—defined as the tension-free adaptation of the prosthetic framework to implant components without inducing internal stress [

1,

2,

3]. Lack of passive fit may lead to screw loosening, component fracture, and marginal bone resorption, compromising prosthesis stability and implant survival [

4,

5]. Because the impression is the foundation of the restorative workflow, errors introduced at this stage, whether analog or digital, can be amplified through model fabrication, CAD/CAM design, and manufacturing [

6,

7].

Passive fit can be influenced by several clinical and technical parameters. One of these is the accuracy of the dental impression, which serves as the foundation for the prosthetic fabrication process [

6,

7]. The impression transfers the three-dimensional spatial relationship of implants, soft tissue contours, and adjacent teeth to the dental laboratory, either in physical or digital form. Errors introduced during this stage may be magnified during model fabrication, CAD/CAM design, and prosthesis production. For example, in conventional workflows, inadequate splinting of impression copings, improper seating of the tray, or material shrinkage during polymerization can introduce spatial discrepancies. Analog errors may also arise from distortion of impression materials, expansion of dental stone, or misalignment during analog insertion [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. In digital workflows, incomplete capture of the scan-body geometry, deviation from a standardized scan path, or the presence of reflective surfaces can result in stitching errors or inconsistent surface rendering [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Conventional impressions typically rely on elastomeric materials such as polyvinyl siloxane (PVS) or polyether, used in combination with open-tray or closed-tray techniques [

21,

22]. When handled properly, these materials provide accurate surface reproduction and dimensional stability. However, the analog workflow involves multiple interdependent steps (tray selection, adhesive application, coping placement, impression material handling, and model pouring), each of which can introduce variability. In addition, these procedures are often associated with patient discomfort, particularly in posterior areas or when trays extend into the soft palate, triggering a gag reflex. They are also technique-sensitive and time-consuming, often requiring remakes or adjustments in the laboratory [

23].

Digital impressions, captured with intraoral scanners (IOS), have emerged as an alternative that simplifies several of these steps. IOS systems record optical data of the dentogingival and implant environment, producing a virtual model in real time. The scanned data can be exported in STL (stereolithography) files and imported into CAD software (i.e., Exocad, 3Shape, Blender for Dentistry, etc.), enabling virtual prosthesis planning and fabrication. Examples of commonly used scanners in implant prosthodontics include the 3Shape TRIOS and Medit i700 systems. Compared to conventional methods, digital workflows eliminate tray distortion, material shrinkage, and cast-related errors. They also improve communication with dental laboratories through rapid STL file sharing, reduce the need for repeat appointments, and generally improve patient acceptance, especially in those with limited mouth opening or a strong gag reflex [

24,

25].

The Group 5 ITI Consensus Report on Digital Technologies supports the clinical reliability of digital impressions in single-unit and short-span prosthetic cases [

26]. It highlights comparable, and in some cases, superior, accuracy relative to conventional techniques and recommends intraoral scanning as a valid option in routine clinical practice [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. However, certain challenges remain. For example, digital workflows may be less predictable in full-arch cases, where stitching errors or scan-body misalignment can accumulate across the arch. Deep subgingival margins, multiple angulated implants, and reflective metallic components may also complicate scanning. Moreover, factors such as scanner brand, software compatibility, cost, and operator experience may influence outcomes and limit adoption in some settings [

36,

37,

38].

While several studies [

6,

29,

39,

40,

41,

42] have evaluated the accuracy of digital impressions in vitro, fewer have investigated clinical outcomes under real-world conditions [

13,

43,

44]. Furthermore, direct comparisons between digital and conventional impressions often focus on one variable (i.e., fit, time, or subjective experience) rather than all three. The clinical relevance of a workflow is best evaluated by combining objective measurements (such as prosthetic misfit or adjustment frequency) with workflow efficiency and patient-reported satisfaction.

The present study directly compares conventional elastomeric impressions and digital intraoral-scanner impressions in partially edentulous patients receiving fixed implant restorations. We assessed clinical fit (Sheffield test and radiography), workflow efficiency (chairside time and steps), and patient-reported outcomes (10-item VAS). We hypothesized that digital impressions would provide comparable or superior clinical outcomes and greater patient satisfaction than conventional methods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

This retrospective, comparative clinical investigation evaluated accuracy, passive fit, and patient-reported outcomes in implant-supported restorations fabricated using either conventional elastomeric impressions or digital intraoral scanners. The sample size (n = 40) reflects all consecutive eligible cases within the study timeframe; no a priori power calculation was performed due to the retrospective design (acknowledged as a limitation).

The study included patients requiring partial implant-supported restorations (ranging from two to six implants per arch) and was structured around predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure homogeneity and clinical relevance. Also, this study was conducted in collaboration with the Faculty of Dentistry, “Victor Babeș” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timișoara.

The protocol received ethical clearance from the Ethics Committee for Scientific Research of the “Victor Babeș” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timișoara, under approval number 16/21.01.2025. All procedures followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and each participant provided written informed consent prior to inclusion.

The study outcomes analyzed included:

Radiographic accuracy of the prosthesis–implant interface;

Intraoral clinical misfit assessments using mechanical and visual methods;

Patient satisfaction scores using a structured VAS.

This design allowed for a clinically relevant comparison of impression accuracy, fabrication workflow efficiency, and patient-centered factors across conventional and digital workflows in implant prosthodontics. This was a retrospective clinical analysis based exclusively on previously completed implant-supported restoration cases. No patient was prospectively enrolled or exposed to additional diagnostic procedures for the purpose of this study.

2.2. Patient Selection and Group Allocation

A total of 40 patients were included in this study, each requiring prosthetic rehabilitation with implant-supported restorations in partially edentulous arches. All treatments were carried out at the Dental Clinic under standardized clinical conditions. Patients were divided into two equal groups of 20, according to the impression method used. Group A received conventional impressions using elastomeric materials and the open-tray/closed-tray techniques, while Group B underwent digital impressions using intraoral scanners (Medit i700 (Seoul, Republic of Korea) and 3Shape TRIOS 3 (Copenhagen, Denmark)). Accordingly, Group A combined two tray techniques (open/closed) and two impression materials (PVS/polyether), and Group B combined two intraoral scanners (TRIOS 3/Medit i700). No subgroup stratification was performed in this clinical series; this heterogeneity reflects real-world practice and is explicitly considered in the Discussion and Conclusions.

Patients were included in the study if they were aged 18 years or older, presented with at least two integrated implants per arch requiring splinted restorations, demonstrated sufficient bone support clinically and radiographically, were able to attend follow-up visits, and provided signed informed consent for participation and data use.

Exclusion criteria comprised complete edentulism in either arch, the presence of severe parafunctional habits such as bruxism or clenching, limited mouth opening that would impair either intraoral scanning or tray seating, systemic health conditions negatively affecting bone healing or integration (e.g., uncontrolled diabetes or immunodeficiencies), and pregnancy or breastfeeding status.

To ensure consistency, both groups were matched for implant distribution, arch configuration, and prosthetic design complexity, enabling a clinically relevant comparison between digital and conventional workflows.

2.3. Conventional Impression Technique

2.3.1. Materials

Conventional impressions were obtained using elastomeric materials with clinically validated dimensional stability. Polyvinyl siloxane (PVS; Elite HD+, Zhermack, Badia Polesine, Italy) was selected for its elastic recovery and accuracy; while polyether (Impregum, 3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany) was chosen in cases requiring increased rigidity and hydrophilic performance. All impressions were performed using custom-fabricated rigid trays made from autopolymerizing acrylic resin to minimize deformation during handling and seating. To enhance three-dimensional accuracy, impression copings were splinted intraorally using GC Pattern Resin LS (GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Type IV gypsum stone (FujiRock EP, GC, Tokyo, Japan) was used for model pouring, enabling the fabrication of high-precision working casts. In

Figure 1 photos of closed and open tray impressions and the form of closed and open tray are presented.

2.3.2. Procedure

The impression protocol followed an open-tray technique. Implant-level impression copings were placed intraorally and verified radiographically for full seating. Custom acrylic trays were perforated to permit access to the coping screws, and a tray adhesive was applied uniformly to ensure optimal bonding with the impression material. The selected elastomeric material (PVS or polyether) was prepared according to the manufacturer’s guidelines and carefully injected around each coping. The tray was then seated with uniform pressure and maintained in place until full polymerization was achieved. Once set, the copings were unscrewed intraorally and the tray was removed, capturing the implant positions in a stable impression medium.

To reduce positional distortion, impression copings were splinted prior to impression-taking using autopolymerizing acrylic resin. After the tray removal, impressions were disinfected and poured within 30 min using Type IV dental stone. Implant analogs were inserted into the negative imprint corresponding to each coping to create the master cast (

Figure 2). Subsequently, an acrylic resin verification jig was fabricated and tested clinically to confirm the accuracy of implant analog positioning within the cast. Passive fit was confirmed prior to advancing to the CAD/CAM prosthetic planning stage.

2.4. Digital Impression Technique

2.4.1. Materials

Two intraoral scanners were employed in this study to capture digital impressions: the Medit i700 (Medit Corp., Seoul, Republic of Korea) and the 3Shape TRIOS 3 (3Shape A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark). Both devices offer high-resolution image acquisition and have been validated for use in implant prosthodontics. The digital impression data were saved in STL file format and subsequently processed using Exocad 3.2 Elefsina 9036 DentalCAD software (Exocad GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). This software facilitated the generation of virtual models, digital framework design, and CAD/CAM workflow integration. Final models and restorations were fabricated via additive and subtractive manufacturing using high-resolution 3D printing and milling systems. Two examples were presented in

Figure 3. The examples are not from our cases; it is just illustrative, to present the digital impressions.

2.4.2. Procedure

Digital impressions followed a standardized scan path to ensure consistent and complete capture of intraoral structures. The protocol began with the occlusal surfaces, proceeded to the buccal and lingual aspects, and ensured that scan bodies, soft tissue margins, and occlusal relationships were clearly recorded. The scanning process was executed under controlled lighting and moisture-free conditions to optimize image acquisition and reduce digital noise, as in the recommended protocol from each intraoral scanner manual.

Once acquired, the STL datasets were exported into the Exocad environment, where virtual models were constructed and verified. The software allowed for precise alignment of implant scan bodies, visualization of angulation, and real-time adjustment of prosthetic parameters, including emergence profile and occlusal morphology. The finalized prosthetic designs were then transferred to the production phase, using either CAD/CAM milling or stereolithographic 3D printing with photopolymer resins.

Figure 4 shows a finalized digital model made with the help of an impression acquired using Medit i700 intraoral scanner. The scan captures three implant scan bodies and surrounding soft tissue contours within the mandibular arch. The color-coded gingiva mask (highlighted in pink) represents the digitally defined emergence profile and anatomical boundaries of the peri-implant region. This digital model serves as the foundation for virtual prosthetic design and framework planning, enabling precise evaluation of implant angulation, spatial constraints, and occlusal integration prior to CAD/CAM fabrication.

Digital frameworks were evaluated for precision and passive fit prior to clinical insertion. This workflow significantly reduced impression time, minimized patient discomfort, and facilitated direct collaboration with the dental laboratory by enabling rapid digital communication and remote design modifications.

The scan data captured with the TRIOS 3 system enabled accurate reproduction of soft tissue contours and implant emergence profiles, supporting precise prosthetic adaptation. The model demonstrates high anatomical fidelity and is used for laboratory fit verification of the digitally designed restoration (

Figure 5a). In

Figure 5b, the model features a three-unit implant-supported fixed partial denture on a soft tissue analog base. The gingiva mask and restoration were fabricated based on scan data captured with the Medit scanner. The resulting model offers comparable anatomical accuracy and restorative detail, validating the Medit system’s suitability for clinical and laboratory digital workflows.

2.5. Evaluation Methods

Clinical and radiographic evaluations were performed at multiple stages during treatment to assess the accuracy and fit of the implant-supported restorations. These evaluations aimed to quantify both objective misfit and patient-reported outcomes.

Radiographic assessments were conducted during the initial impression phase, provisional restoration try-in, and final prosthesis delivery. CBCT, panoramic radiographs, and intraoral periapical radiographs were used to visualize the implant–abutment interface and prosthetic fit. All imaging was performed using standardized exposure parameters, with radiographs analyzed using calibrated digital imaging software to assess marginal gaps and seating accuracy. In

Figure 6, a representative case is presented, illustrating the radiographic sequence from the patient’s initial visit to the annual follow-up appointments.

Figure 6a shows the panoramic radiograph (OPG) obtained at the first visit.

Figure 6b corresponds to the postoperative image taken immediately after implant placement.

Figure 6c illustrates the situation six months after surgery, following the delivery of the temporary restoration.

Figure 6d shows the radiograph taken six months after provisional restoration was delivered, immediately after delivery of the definitive restorations.

Figure 6e–i represent the annual recall examinations. Vertical marginal discrepancies were quantified as linear distances in millimeters (mm) at the implant–abutment interface. All radiographic examinations (periapical, panoramic, or CBCT) included in the analysis were obtained strictly for clinical diagnostic and follow-up purposes according to standard treatment protocols. No supplementary exposures were performed for research reasons. Data were analyzed retrospectively from existing clinical records. Impression procedure duration was recorded in minutes (min). Patient-reported outcomes were collected as Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores on a 1–10 scale (dimensionless) (

Appendix A). The same diagnostic criteria were applied across both digital and conventional groups to ensure consistency.

Prosthetic misfit was clinically evaluated using the Sheffield test (also known as the one-screw test), a validated clinical method for detecting vertical or rotational discrepancies in prosthetic frameworks. Each restoration was initially seated using a single central screw, and any lifting or rocking of the prosthetic structure was visually and tactically assessed. A passive fit was confirmed when no visible or palpable displacement occurred after sequential tightening of the remaining screws.

Measurements were performed directly within the Planmeca Romexis software, which allows for calibrated linear distance evaluation on all digital images. The Sheffield test was performed by the two experienced clinicians, Dr. Ioan Borșanu and Dr. Sergiu-Manuel Antonie, both trained in the same implant prosthodontic protocol to ensure consistent tactile and visual assessment of passive fit.

Quantitative comparison of marginal discrepancies was performed using radiographic measurements at the implant–abutment interface (

Figure 7b). The presence of vertical gaps, angular misalignments, or overextensions was noted and compared between groups.

Patient-centered outcomes were assessed through a structured VAS questionnaire completed after final prosthesis delivery. Patients were asked to rate their experience across ten categories, including comfort during the impression procedure, presence of gag reflex, esthetic satisfaction with both temporary and final restorations, ability to chew and speak, daily comfort, ease of adaptation, willingness to undergo the procedure again, and overall treatment satisfaction. Each parameter was scored from 1 (very dissatisfied or very uncomfortable) to 10 (extremely satisfied or extremely comfortable), and the results were used to statistically compare the subjective acceptability of the two workflows.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data were compiled and statistically analyzed to evaluate differences between the conventional and digital impression groups. Continuous variables, such as impression time, marginal gap measurements, and VAS scores, were expressed as means with standard deviations. Categorical data, including the presence or absence of clinical misfit (Sheffield test results), were reported as frequencies and percentages.

Comparisons between the two groups were performed using the independent-samples t-test for normally distributed continuous variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric data. The chi-square test was used for categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the StatsKingdom online platform (

https://www.statskingdom.com/, accessed on 21 May 2025), a validated web-based tool for biomedical data analysis. The use of StatsKingdom ensured reproducibility and transparency in statistical calculations. Graphs and tables were created using Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Accuracy and Misfit

A total of 40 implant-supported prosthetic restorations were evaluated, with 20 fabricated using the conventional impression technique (Group A) and 20 using digital impressions (Group B). Passive fit was assessed using both clinical and radiographic methods at multiple stages of treatment.

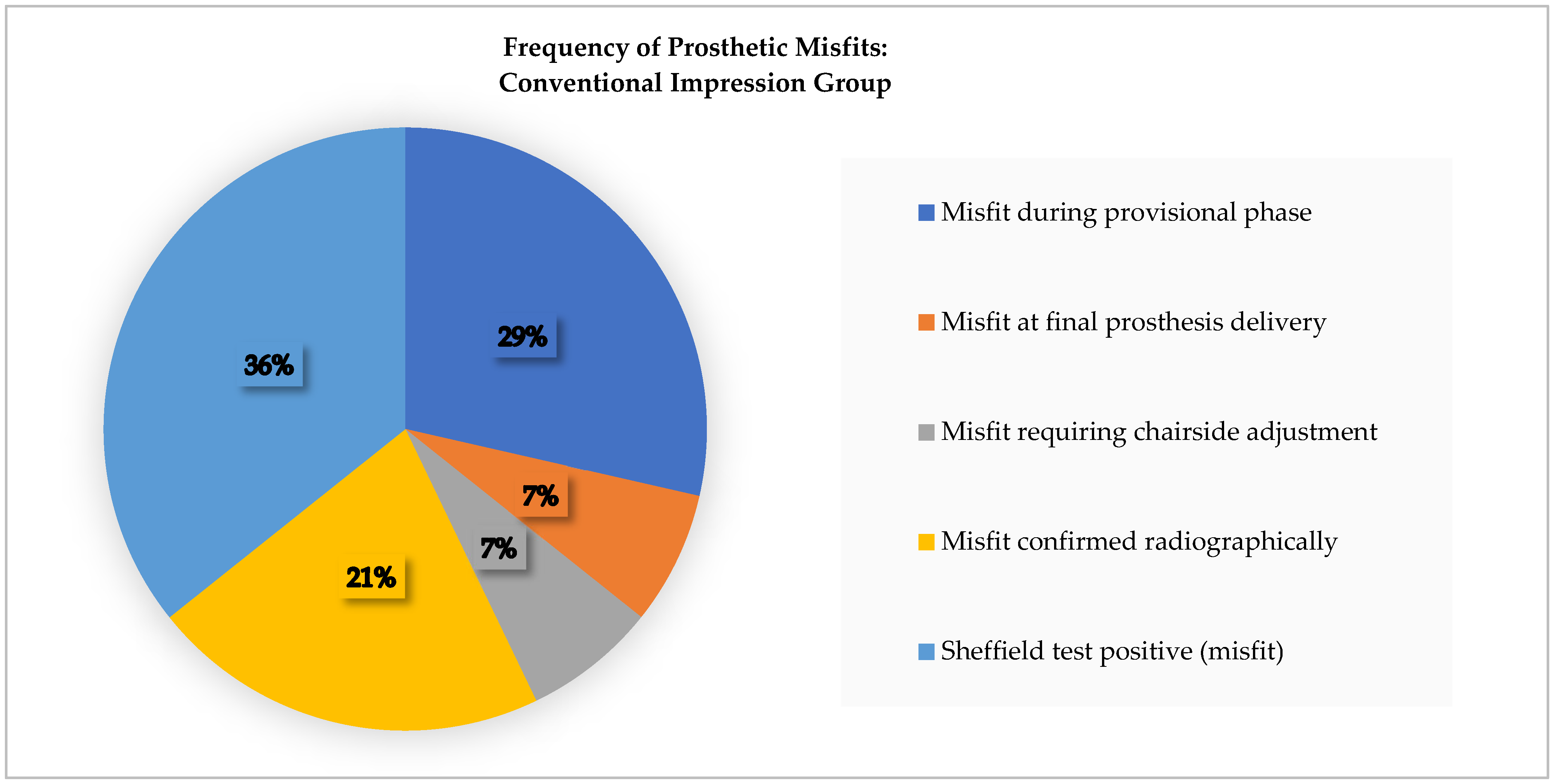

In Group A (conventional), five restorations (25%) demonstrated prosthetic misfit. No misfits were detected immediately following impression-taking; however, four cases exhibited vertical lifting or framework instability during the temporary restoration phase. These were attributed to analog mispositioning or material expansion during cast fabrication. One additional misfit was identified at the final prosthesis delivery stage and required minor intraoral adjustment to achieve passive fit. Radiographic evaluation revealed marginal gaps at the implant–abutment interface in three of the five misfit cases, confirming the clinical findings. Sheffield testing in this group frequently revealed framework rocking or uneven seating, consistent with incomplete adaptation.

In Group B (digital), three restorations (15%) were identified with misfit during the provisional phase. No misfits were observed at the scan stage or at final delivery. The discrepancies were limited to the temporary restorations and were likely related to minor digital design errors or resin shrinkage during provisional fabrication. All final restorations in Group B achieved passive fit clinically and radiographically without the need for chairside adjustments. Sheffield testing confirmed stable seating in all 20 digital restorations at the final insertion. A summary of the clinical misfit findings observed throughout the workflow is presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 8 shows the distribution of prosthetic misfit occurrences within the Conventional Group.

When comparing groups, digital impressions were associated with a lower rate of clinically significant misfit and greater reproducibility across the workflow. While both techniques could produce acceptable results, the digital approach demonstrated more consistent adaptation at both the temporary and definitive stages.

3.2. Procedural Efficiency

Significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of clinical workflow efficiency and chair-side time. Digital impressions consistently require less time and fewer procedural steps compared to conventional techniques.

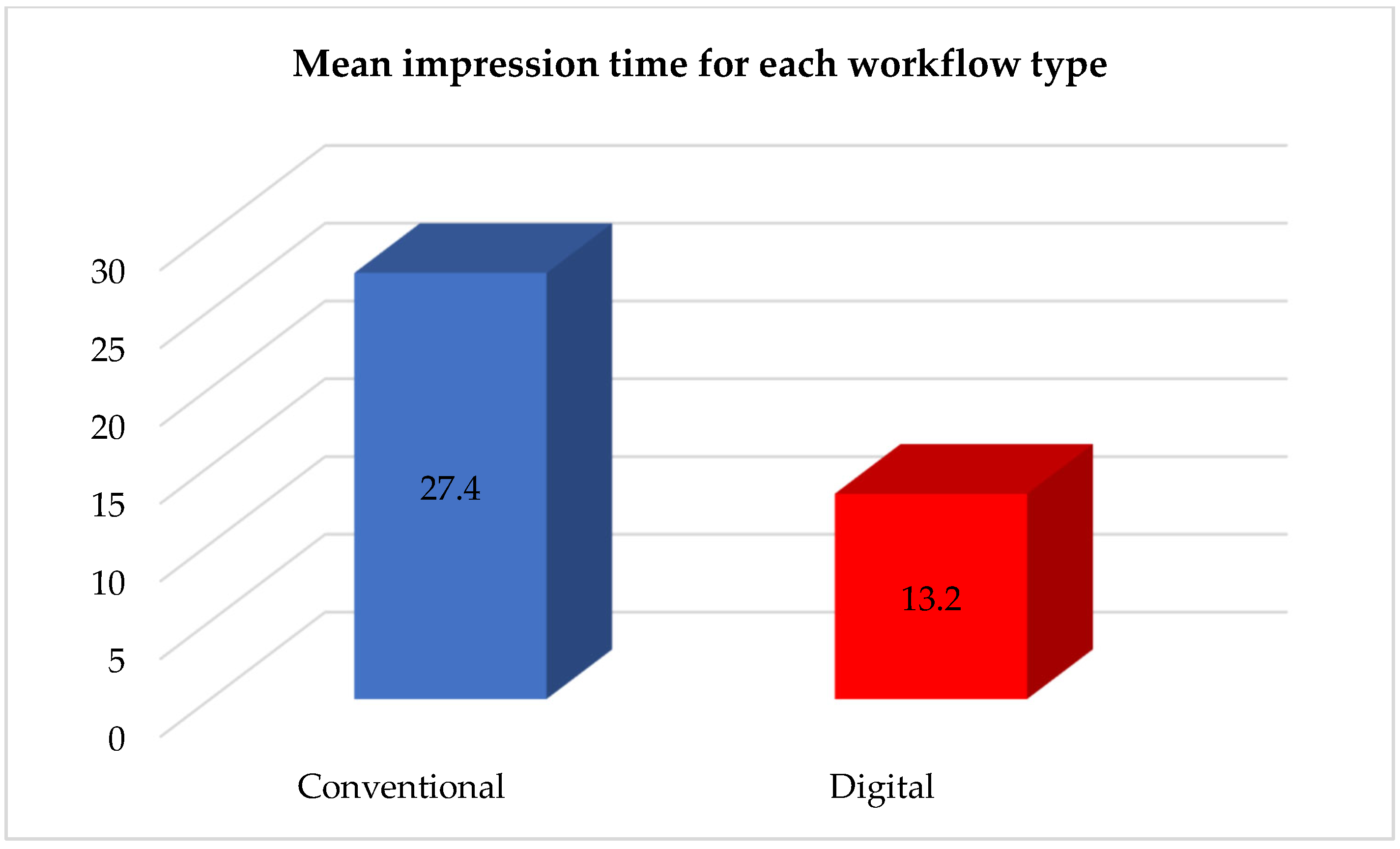

In the conventional group (Group A), the mean chairside time for the impression procedure was approximately 27.4 ± 3.1 min. This included tray selection, tray adhesive application, coping splinting, material mixing, impression setting time, and tray removal. Additional time was often required for post-impression disinfection and analog positioning. Although no repeat impressions were necessary in this group, minor framework adjustments were needed in three cases due to minor seating issues.

In the digital group (Group B), the mean impression time was significantly shorter, averaging 13.2 ± 2.5 min (

p < 0.001). The procedure involved real-time intraoral scanning and STL file generation, with no need for impression materials or trays. None of the digital impressions required repetition, and no framework adjustments were needed at the final delivery stage. Additionally, communication with the laboratory was more efficient, as STL files were transmitted digitally, allowing for immediate feedback and design validation. A comparative analysis of the clinical efficiency and workflow characteristics between the conventional and digital protocols is summarized in

Table 2, while

Table 3 and

Figure 9 show the fact that the mean impression time differed substantially between the two workflows.

Clinicians also reported greater predictability in the digital workflow, with smoother transitions from scanning to design and delivery phases. The reduced need for physical storage, impression pouring, and analog placement contributed to a more streamlined and reproducible process.

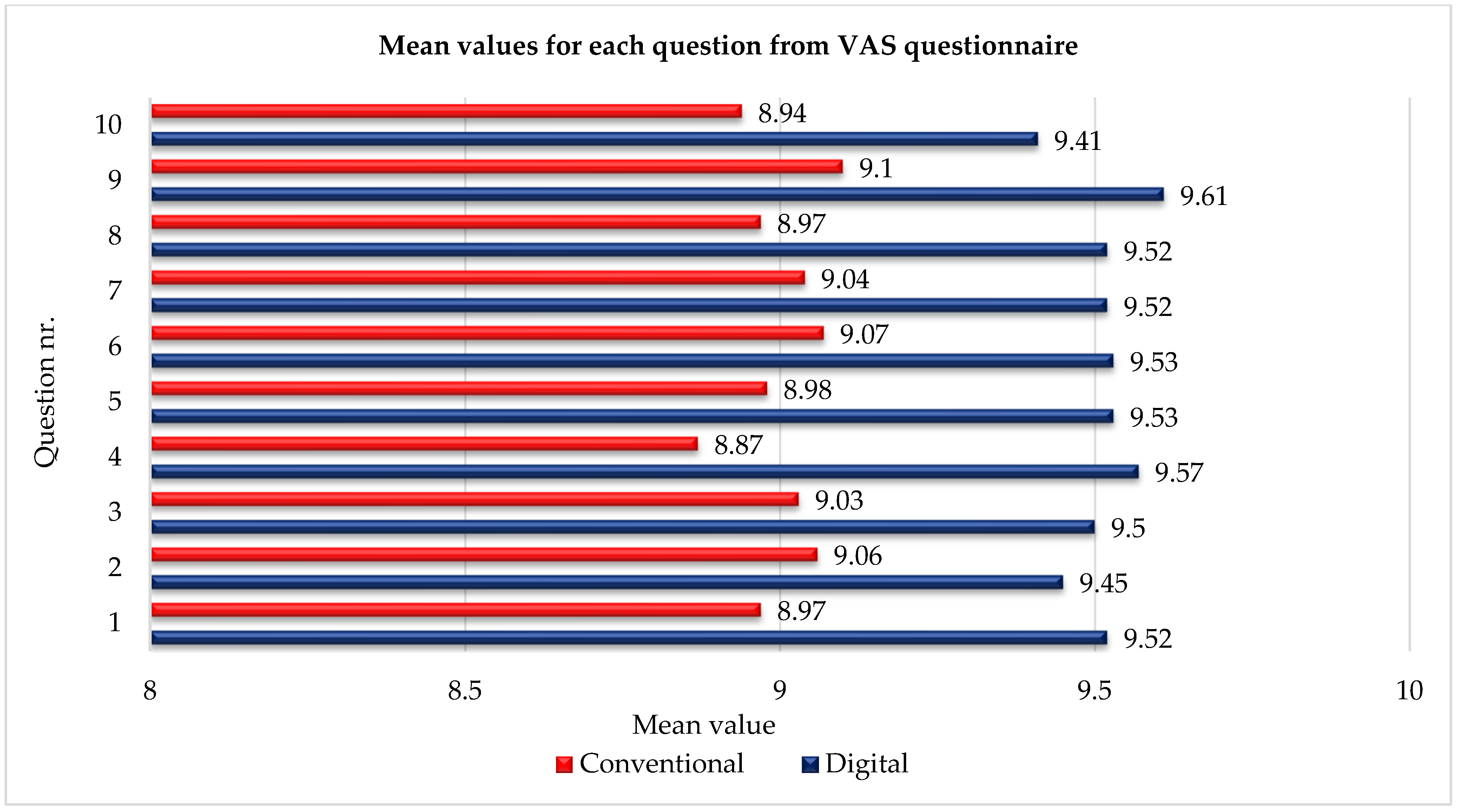

3.3. Patient-Reported Outcomes

Patient satisfaction and comfort were evaluated using a 10-item Visual Analog Scale (VAS) questionnaire completed after the final prosthesis delivery. Each item was scored on a scale from 1 (not satisfied/very uncomfortable) to 10 (extremely satisfied/very comfortable). All 40 patients completed the questionnaire, providing a full dataset for comparison between the two impression workflows (

Table 4 and

Table 5).

The digital impression group (Group B) consistently reported higher satisfaction across all 10 parameters. The mean overall VAS score for Group B was 9.52 ± 0.15, while the conventional impression group (Group A) reported a slightly lower mean score of 9.03 ± 0.27. The most significant differences were observed in parameters related to procedural comfort, gag reflex, and ease of adaptation. For example, the average comfort rating during the impression procedure was 9.52 in Group B versus 8.97 in Group A. The gag reflex was notably less prevalent in the digital group, with a mean score of 9.45 compared to 9.06 in the conventional group.

Patients in the digital group also reported better satisfaction with the esthetics of both temporary and final restorations, with ratings exceeding 9.5 in most cases. Functional parameters, including chewing ability and speech clarity, were slightly higher in the digital group but not statistically significant. However, the overall satisfaction and willingness to undergo the same treatment again were significantly greater in Group B (mean score 9.61) compared to Group A (mean score 9.10,

p < 0.05), as illustrated in

Figure 10.

These results indicate that patients perceived the digital workflow as more comfortable and predictable, with superior procedural experience and esthetic outcomes. The consistently high scores across all VAS items support the clinical preference for digital impressions, particularly in patients with a strong gag reflex or low tolerance for conventional trays.

A summary of the principal clinical and patient-reported outcomes comparing the two impression workflows is provided in

Table 6, highlighting differences in misfit rates, procedure duration, and overall patient satisfaction.

4. Discussion

This study provides clinical evidence that digital impression techniques can enhance the accuracy, efficiency, and patient experience of implant-supported prosthetic rehabilitation compared to conventional elastomeric methods. The digital group demonstrated a lower incidence of prosthetic misfit (15% vs. 25%) and achieved full passive fit in all definitive restorations. Patients also reported significantly higher satisfaction, particularly in relation to comfort, gag reflex, and esthetics. These findings suggest that intraoral scanners not only reduce technical errors but also deliver tangible patient-centered benefits.

The current results align with the findings of the Group 5 ITI Consensus Report on Digital Technologies [

26], which supports intraoral scanning as a reliable method for single-unit and short-span prostheses. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses reinforce this position: Park et al. (2025) found digital impressions to have significantly lower linear deviations than conventional methods in partially dentate patients [

45], while Elashry et al. (2024) demonstrated that deviations recorded with intraoral scanners were clinically acceptable [

46]. From a patient perspective, Pachiou et al. (2025) confirmed that digital impressions yield higher satisfaction and comfort [

47]. In vitro investigations, such as that of Ben-Izhack et al. (2024), also corroborate improved reproducibility of implant axis determination with digital workflows [

48]. Taken together, these studies contextualize our findings within the broader body of contemporary evidence.

We note that each study group aggregated commonly used sub-techniques/devices (open/closed tray and PVS/polyether in Group A; TRIOS 3/Medit i700 in Group B), introducing methodological heterogeneity; future studies should stratify or randomize by single technique/material/scanner to isolate their individual effects. This methodological heterogeneity reflects real-world clinical variability and was considered an inherent characteristic of routine prosthodontic workflows. Nevertheless, it is acknowledged as a limitation and should be refined in future randomized or single-technique studies.

From an economic standpoint, although the initial purchase of intraoral scanners and CAD/CAM systems involves higher costs, these are offset by reduced chairside time, fewer remakes, and improved laboratory communication. In addition, our long-term clinical experience indicates that the cumulative costs of conventional impression materials for several hundred impressions (e.g., approximately 300 cases) can exceed the investment in a single intraoral scanner, further supporting the cost-effectiveness of digital workflows.

From a clinical standpoint, the advantages of digital impressions extend beyond accuracy. The digital workflow simplifies procedures, shortens chairside time, and eliminates errors related to tray distortion, polymerization shrinkage, or cast expansion. Moreover, the ability to capture real-time data and instantly correct scanning artifacts improves reproducibility. These benefits are particularly valuable in patients with strong gag reflexes, limited mouth opening, or high esthetic demands. Importantly, our data showed that digital workflows minimized the need for chairside adjustments, thereby improving predictability and efficiency.

Despite the promising results, several limitations must be acknowledged. The study had a modest sample size (

n = 40) and was retrospective in nature. Patients were divided into two independent groups, without crossover or split-mouth design, limiting direct intra-patient comparisons. Furthermore, the scanners evaluated—TRIOS 3 and Medit i700—are previous-generation devices; their performance may not fully represent newer systems. Each group also combined multiple sub-techniques, which may introduce heterogeneity, as noted above. Our fit evaluation relied on clinical and radiographic assessments rather than three-dimensional deviation analysis, which may have limited sensitivity to micro-misfits. Finally, the study focused only on partial-arch restorations, and extrapolation to full-arch or immediate-loading protocols requires caution. Similar findings were reported by Iliescu et al. [

49], who observed that peri-implant mucosal lesions were more frequent in immediately loaded implants compared to delayed protocols, highlighting the need for careful consideration of loading strategies.

From an economic perspective, the adoption of intraoral scanning (IOS) in our clinic has resulted in clear long-term cost saving despite the higher initial investment. In our experience, the recurrent expenses previously associated with elastomeric materials, tray fabrication, disinfection, and the production and storage of cast models have markedly decreased since the implementation of digital workflows. These findings are consistent with recent studies demonstrating that intraoral scanning reduces overall procedural costs and chairside time when compared to conventional impression methods in implant dentistry [

50]. Although the acquisition of scanners and CAD/CAM infrastructure entails substantial upfront costs, the amortization period is short due to the elimination of consumable materials, fewer remakes, and improved communication with dental laboratories. Market analyses also confirm that the widespread adoption of digital impression systems is driven by their long-term economic efficiency and workflow optimization [

51]. Furthermore, beyond cost and time efficiency, a 2025 meta-analysis emphasized that patient preference and comfort further strengthen the clinical justification for digital impression techniques [

47]. Altogether, these observations suggest that, for clinics performing moderate to high case volumes, digital workflows are both clinically and economically advantageous compared to traditional analog approaches.

Future research should therefore include multicenter randomized trials with larger sample sizes, standardized 3D deviation analysis of STL datasets, and long-term follow-up. Cost–benefit analyses comparing digital and conventional workflows across the entire treatment lifecycle would also be valuable. Additional investigations into dynamic occlusion integration, guided surgery, and biologic outcomes such as peri-implant bone stability and soft-tissue health will further clarify the role of digital workflows in implant dentistry. Looking ahead, studies employing prospective or crossover designs could provide stronger evidence by reducing bias and allowing within-patient comparisons of digital and conventional techniques. Such approaches would help clarify causal relationships and minimize the variability inherent in retrospective analyses. Larger, multicenter clinical trials with standardized protocols and long-term follow-up would also make it possible to evaluate the durability, biological integration, and cost-effectiveness of digital workflows with greater precision.

5. Conclusions

This retrospective comparative clinical study indicates that digital impression techniques offer meaningful advantages over conventional elastomeric methods for implant-supported prosthetic restorations in partially edentulous patients. Clinically, the digital workflow showed a lower incidence of prosthetic misfit (15% vs. 25%), no misfits at the definitive stage, and substantially shorter impression times (13.2 ± 2.5 min vs. 27.4 ± 3.1 min). These gains likely reflect the elimination of tray-related distortions and material-handling errors, along with real-time scan verification and more predictable CAD/CAM integration. Patient-reported outcomes paralleled these findings, with higher scores across all ten VAS domains—particularly for comfort, reduced gag reflex, and esthetic satisfaction—underscoring the patient-centered benefits of intraoral scanning. Operationally, streamlined laboratory communication (STL exchange), fewer procedural steps, and fewer chairside adjustments further improved efficiency and predictability. Although a full economic analysis was beyond our scope, routine clinical experience suggests that time savings, fewer remakes, and reduced material use can offset the upfront cost of scanner acquisition over typical case volumes.

As this was a retrospective study, the devices available during the treatment period were previous-generation intraoral scanners. It is likely that newer devices would demonstrate equal or greater advantages for digital workflows. Moreover, each group combined sub-techniques/devices (tray technique and material in the conventional group; scanner brand in the digital group), which may contribute to variability; future trials should stratify or randomize by a single technique/material/scanner. While the present study demonstrated clear clinical and patient-centered advantages of digital impressions, it did not evaluate potential differences at the STL dataset level between scanners or between scanned analog impressions and direct intraoral scans. Future research incorporating quantitative deviation analysis of STL files would provide further insight into reconstruction accuracy and may strengthen the comparative evaluation of conventional and digital workflows. It should also be noted that patients in this study were allocated to separate groups, without a crossover or split-mouth design, which limited direct intra-patient comparability.

Beyond these device- and design-related constraints, the sample size was modest (n = 40) and restricted to partial-arch restorations; therefore, extrapolation to full-arch or immediate-load protocols should be cautious. Misfit assessment relied on clinical and radiographic methods rather than three-dimensional deviation analyses, which could detect micro-discrepancies more sensitively.

In summary, for partial-arch implant rehabilitation, digital impressions represent a clinically effective, patient-preferred, and workflow-efficient alternative to conventional methods. Analog techniques remain viable when performed under rigorous protocols, but the balance of accuracy, efficiency, and patient acceptance observed here supports the growing adoption of digital workflows in contemporary implant prosthodontics. Future studies should include larger, multicenter randomized designs, stratification by single technique/material/scanner, quantitative STL-based analyses, and long-term biologic outcomes to refine clinical recommendations and broaden generalizability.