Perspectives on Ethics Related to Aesthetic Dental Practices Promoted in Social Media—A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Aesthetic and Cosmetic Dentistry

1.2. Social Media and Aesthetic Dentistry

1.3. The Nature of Dental Profession

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Survey Instrument

- a.

- To identify the risk of overtreatment, unnecessary procedures, or underdiagnosed diseases related to aesthetic treatments;

- b.

- To highlight difficulties in truth-telling patients;

- c.

- To explore participants’ understanding of the duty to promote the patient’s good (exception, case 3).

- Case Scenario 1: An 18-year-old patient, Alice, presents to the dental clinic requesting a cosmetic dental treatment. She shows the dentist a photo of a well-known social media influencer—who is also a patient of the clinic—and expresses her desire to achieve the same smile. However, her dental anatomy is markedly different, and the proposed treatment is contraindicated at her age due to both functional and developmental concerns. When asked about her motivation, Alice says she wants to look like her favorite Instagram celebrity and is willing to pay any amount to achieve this outcome.How should this case be approached?

- A.

- Proceed with the treatment, as the patient is insistent and able to pay.

- B.

- Refuse the treatment, explain the patient’s young age and the associated risks, and provide a rationale for the refusal.

- C.

- Inform the patient’s parents about the aesthetic request, along with the risks and benefits of the proposed treatment.

- D.

- Choose an alternative option and describe it in one sentence.

- Case Scenario 2: Cecily, a 23-year-old patient, visits the clinic to receive a free tooth whitening treatment offered during a promotional campaign advertised on social media. During the consultation, the dentist observes that Cecily appears underweight and exhibits signs of severe enamel erosion, consistent with bulimia. The dentist explains that the yellowing of her teeth may be due to repeated vomiting and that this underlying issue must be addressed before any aesthetic treatment can be effective. Cecily denies any such habit and insists her teeth have always looked that way.How should this case be approached?

- A.

- Proceed with the whitening treatment, as it was the reason for her visit and is offered free of charge.

- B.

- Refuse the treatment, explaining that it would not be effective.

- C.

- Refuse the treatment unless the patient provides evidence of receiving appropriate care, assuring her that she will still be eligible for the promotional offer at a later time.

- D.

- Choose an alternative option and describe it in one sentence.

- Case Scenario 3: Anna, a 20-year-old patient, arrives for a dental appointment and is greeted warmly by the dentist, who acknowledges her role in promoting the clinic on Instagram. As part of a referral incentive, the dentist pays Anna €50 for every five new patients she refers. The clinic’s social media following, and patient base have expanded significantly as a result. After eight months, Anna returns to request veneers for both her upper and lower front teeth, referencing their earlier informal agreement.How should this case be approached?

- A.

- Proceed with the veneers as previously discussed.

- B.

- Decline the request, as the treatment is too invasive for a 21-year-old.

- C.

- Refuse the veneers, explain the associated risks and long-term consequences, and propose less invasive alternatives, such as whitening or orthodontic correction.

- D.

- Choose an alternative option and describe it in one sentence.

- Case Scenario 4: Lucy, a 34-year-old public figure known for her presence on social media, attends a dental clinic for scaling. During the visit, the dentist notices a mild vestibulo-version of her upper central incisors. Although this issue is not severe, the patient may benefit from an orthodontic consultation. Lucy does not raise any aesthetic concerns during the appointment.How should this case be approached?

- A.

- Avoid recommending orthodontic treatment, as aesthetic requests should be initiated by the patient.

- B.

- Recommend an orthodontic consultation within the same clinic, assuming she may wish to continue treatment there.

- C.

- Recommend an orthodontic evaluation, while leaving the decision about whether and where to proceed entirely to the patient.

- D.

- Choose an alternative option and describe it in one sentence.

2.3. Setting and Participants

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

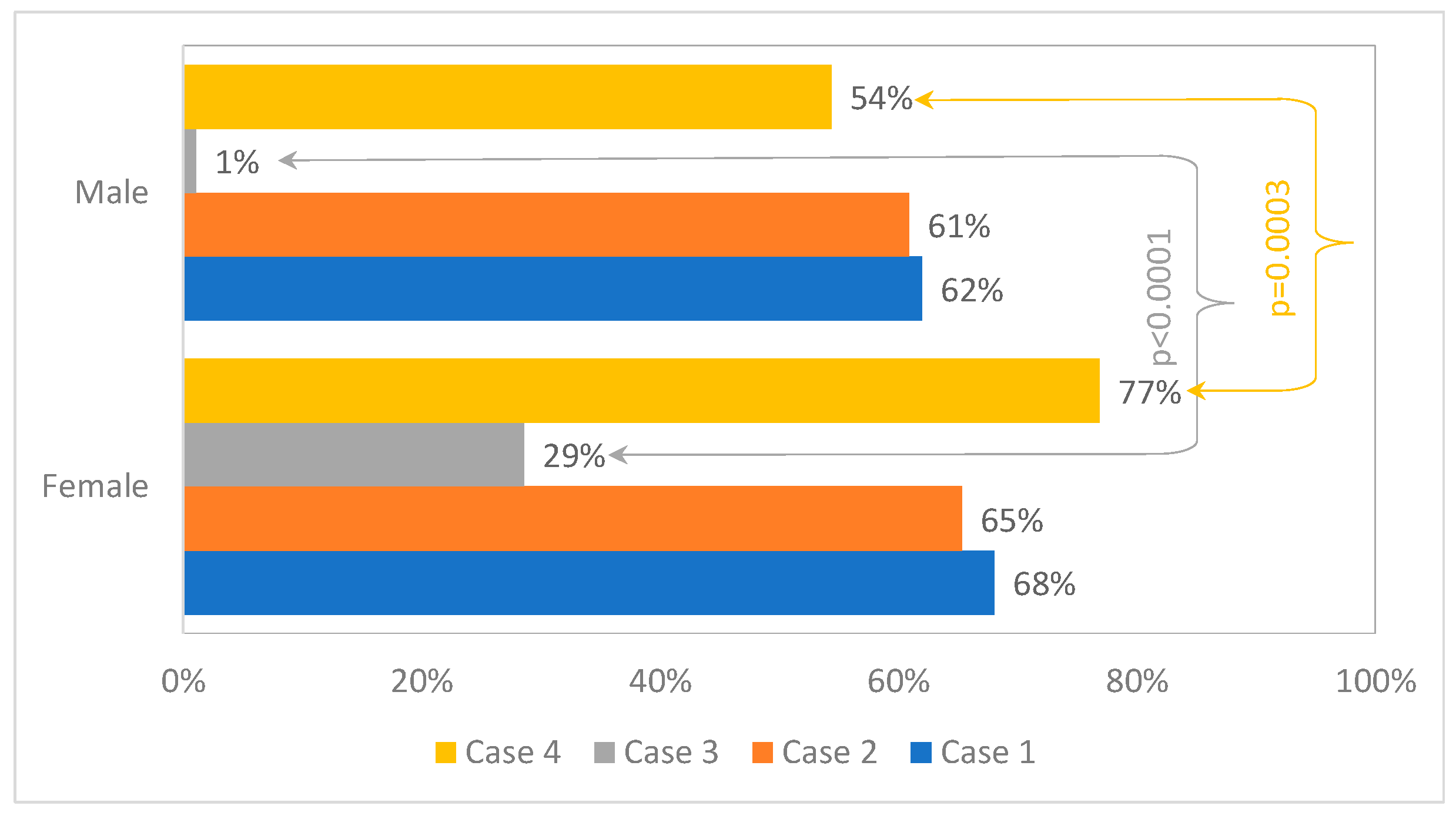

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, I. An introduction to aesthetic dentistry. BDJ Team 2021, 8, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aesthetic Dentistry. Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. 2008. Available online: https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Aesthetic+dentistry (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Abbasi, M.S.; Lal, A.; Das, G.; Salman, F.; Akram, A.; Ahmed, A.R.; Maqsood, A.; Ahmed, N. Impact of Social Media on Aesthetic Dentistry: General Practitioners’ Perspectives. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The American Dental Association. Glossary of Dental Clinical and Administrative Terms. Dental Medical Billing University. 2017. Available online: https://dentalmedicalbilling.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Glossary-of-Dental-Clinical-and-Administrative-Terms.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Wilmont Family Dentistry. Difference Between Aesthetic and Cosmetic Dentistry. Available online: https://wilmotfamilydentistry.com/difference-between-aesthetic-and-cosmetic-dentistry/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Cohen, N. Interview Rencontre avec Paul Miara. Le Fil Dent. Spécial Esthet. Sourire 2007, 23, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). Social Media and Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory [Internet]; US Department of Health and Human Services, Social Media and Youth Mental Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594759/ (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Edwards, B.; Doery, K.; Arnup, J.; Chowdhury, I.; Edwards, D.; Kylie, H. GENERATION Survey: Young People, 2024 Release (Wave 1-2). 2023. Available online: https://dataverse.ada.edu.au/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.26193/YMMO4L (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Freire, Y.; Gómez Sánchez, M.; Sánchez Ituarte, J.; Frías Senande, M.; García, V.D.F.; Suárez, A. Social media impact on students’ decision-making regarding aesthetic dental treatments based on cross-sectional survey data. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binalrimal, S. Effect of Social Media on the Perception and Demand of Aesthetic Dentistry. J. Adv. Med. Dent. Sci. Res. 2019, 18, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Salim, N.A.; Jubair, F.; Hassona, Y.M.; Izriqi, S.; Al-Fuqaha’a, D. Esthetic Dentistry on Twitter: Benefits and Dangers. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 2021, 5077886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamzadeh, M.; Rahimi, F. Aesthetic dentistry and ethics: A systematic review of marketing practices and overtreatment in cosmetic dental procedures. BMC Med. Ethics 2025, 26, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Word Dental Federation General Assembly. International Principles of Ethics for the Dental Profession. 1997. Available online: https://www.fdiworlddental.org/international-principles-ethics-dental-profession (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Hoseinzadeh, M.; Motallebi, A.; Kazemian, A. General dentists’ treatment plans in response to cosmetic complains; a field study using unannounced-standardized-patient. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoneim, A.; Yu, B.; Lawrence, H.; Glogauer, M.; Shankardass, K.; Quiñonez, C. What influences the clinical decision-making of dentists? A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233652, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253183.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruess, S.R.; Cruess, R.L. Professionalism and Medicine’s Social Contract with Society. Virtual Mentor. 2004, 6, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moeller, J.; Quiñonez, C.R. Dentistry’s social contract is at risk. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2020, 151, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Kelleher, M. The Dangers of Social Media and Young Dental Patients’ Body Image. DentalUpdate 2018, 45, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmetic Dentistry Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Product (Dental Systems & Equipment, Dental Implants, Dental Crowns & Bridges), by Region, and Segment Forecasts, 2022–2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/cosmetic-dentistry-market (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Kelleher, M. Ethical issues, dilemmas and controversies in ‘cosmetic’ or aesthetic dentistry. A personal opinion. Br. Dent. J. 2012, 212, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghiu, I.M.; Nicola, G.; Scarlatescu, S.; Al Alouli, A.O.; Iliescu, A.A.; Suciu, I.; Perlea, P. Current Trends and Ethical Challenges in Cosmetic Dentistry. Rom. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 29, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDI World Dental Federation. Ethics in Dentistry 2024. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMatteo, A.M. Dissecting the Debate Over the Ethics of Esthetic Dentistry. Inside Dent. 2007, 3. Available online: https://insidedentistry.net/2007/09/dissecting-the-debate-over-the-ethics-of-esthetic-dentistry (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Kovács, S.D. Suggestion for Determining Treatment Strategies in Dental Ethics. J. Bioethical Inq. 2024, 21, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Masoura, E.; Devetziadou, M.; Rahiotis, C. Ethical Dilemmas for Dental Students in Greece. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Minh Duc, N.T.; Luu Lam Thang, T.; Nam, N.H.; Ng, S.J.; Abbas, K.S.; Huy, N.T.; Marušić, A.; Paul, C.L.; Kwok, J.; et al. A Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS). J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 3179–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnon, Y.C. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook, 2nd ed.; Presses Universitaires de Quebec: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ozar, D.T.; Sokol, D.J.; Patthoff, D.E. Dental Ethics at Chairside: Professional Obligations and Practical Applications, 3rd ed.; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Westgarth, D. The commercialisation of dentistry. BDJ Pract. 2023, 36, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, A.C.L. Dentistry’s social contract and the loss of professionalism. Aust. Dent. J. 2017, 62, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustrell-Torrent, J.M.; Buxarrais-Estrada, M.R.; Ustrell-Torrent Riutord-Sbert, P. Ethical relationship in the dentist-patient interaction. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2021, 13, e61–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.L.; Webb, S.A.; Committee on Bioethics. Informed Consent in Decision-Making in Pediatric Practice. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Thornton, I.; Kopitnik, N.L.; Hipskind, J.E. Informed Consent. [Updated 2024 Nov 24]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430827/ (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Satyanarayana Rao, K.H. Informed consent: An ethical obligation or legal compulsion? J. Cutan. Aesthet. Surg. 2008, 1, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raab, E.L. The parameters of informed consent. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 2004, 102, 225–230; discussion 230–232. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.; Mccullough, L.; Richman, B. Informed Consent: It’s Not Just Signing a Form. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2005, 15, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocanour, C. Informed consent—It’s more than a signature on a piece of paper. Am. J. Surg. 2017, 214, 993–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, Z.; Ahmad, N.; Sawai, M.; Sultan, N.; Bhardwaj, A. Digital Smile Design—An innovative tool in aesthetic dentistry. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2020, 10, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Bhushan, P.; Mahato, M.; Solanki, B.B.; Dutta, D.; Hota, S.; Raut, A.; Mohanty, A.K. The Recent Use, Patient Satisfaction, and Advancement in Digital Smile Designing: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e62459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militi, A.; Sicari, F.; Portelli, M.; Merlo, E.M.; Terranova, A.; Frisone, F.; Nucera, R.; Alibrandi, A.; Settineri, S. Psychological and Social Effects of Oral Health and Dental Aesthetic in Adolescence and Early Adulthood: An Observational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haute Authorite de Sante (HAS). Detection and Management of Dental Problems by Dentists. 2019. Available online: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2021-02/detection_and_management_of_dental_problems_by_dentists_-_toolkit_7.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Schwartz, B. The Ethical Implications of Patient Rewards. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2006, 72, 631–633. [Google Scholar]

- Balevi, B. Ethical care is good dentistry. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2023, 154, 535–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scambler, S.; Gupta, A.; Asimakopoulou, K. Patient-centred care—What is it and how is it practised in the dental surgery? Health Expect 2015, 18, 2549–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naamati-Schneider, L. Strategic changes and challenges of private dental clinics and practitioners in Israel: Adapting to a competitive environment. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2024, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, A.C.L. Consumer-driven and commercialized practice in dentistry: An ethical and professional problem? Med. Health Care Philos. 2018, 21, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Ghanem, E.J.; AlGhanem, N.A.; AlFaraj, Z.S.; AlShayib, L.Y.; AlGhanem, D.A.; AlQudaihi, W.S.; AlGhanem, S.Z. Patient Satisfaction with Dental Services. Cureus 2023, 15, e49223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, A.C.L.; Adam, L.; Thomson, W.M. Dentists’ Perspectives on Commercial Practices in Private Dentistry. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2020, 7, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, A.C.L.; Adam, L.; Thomson, W.M. The relationship between professional and commercial obligations in dentistry: A scoping review. Br. Dent. J. 2020, 228, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, C. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, J.L., III; Gordan, V.V.; Rouisse, K.M.; McClelland, J.; Gilbert, G.H.; Dental Practice-Based Research Network Collaborative Group. Differences in male and female dentists’ practice patterns regarding diagnosis and treatment of dental caries: Findings from The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2011, 142, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemian, A.; Berg, I.; Finkel, C.; Yazdani, S.; Zeilhofer, H.F.; Juergens, P.; Reiter-Theil, S. How much dentists are ethically concerned about overtreatment; a vignette-based survey in Switzerland. BMC Med. Ethics 2015, 19, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasseh, K.; Bowblis, J.R.; Vujicic, M. Pricing in commercial dental insurance and provider markets. Health Serv. Res. 2021, 56, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, D.M. Oral Health: A Gateway to Overall Health. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2021, 12, 211–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Scenario | Correct Answer | Rationale for the Correct Approach |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | B | The correct approach is based on the principle of valid informed consent, which requires an assessment of risks and benefits. Ethical concerns include overtreatment, the provision of unnecessary dental interventions, and the obligation to act in the best interest of the patient. |

| 2 | C | This case raises concerns regarding informed consent, professional integrity, and patient wellbeing. Treating without addressing the underlying condition may constitute overtreatment. Ethical practice requires ensuring the patient’s best interests are prioritized and that the intervention is appropriate and beneficial. |

| 3 | C | This scenario involves ethical issues related to inducement and professionalism. Performing irreversible treatment based on a promotional agreement compromises informed consent. The dentist must act in the patient’s best interest and offer evidence-based, minimally invasive options. |

| 4 | C | Recommendations should be made in the patient’s interest while avoiding coercion. Ethical concerns include maintaining the integrity of informed consent and respecting patient autonomy. The clinician’s role is to inform and advise, not to influence decisions based on commercial or aesthetic assumptions. |

| Characteristic | All (n = 242) | Millennials (n = 136) | Z Generation (n = 106) | Stat. (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1.8 (0.1830) * | |||

| Female | 147 (60.7) | 88 (64.7) | 59 (55.7) | |

| Male | 92 (38) | 47 (34.6) | 45 (42.5) | |

| I prefer not to say | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Citizenship | 20.9 (<0.0001) | |||

| Romania | 132 (54.5) | 91 (66.9) | 41 (38.7) | |

| French | 78 (32.2) | 35 (25.7) | 43 (40.6) | |

| Other # | 32 (13.2) | 10 (7.4) | 22 (20.8) | |

| Professional status | 76.5 (<0.0001) | |||

| Dental resident | 85 (35.1) | 80 (58.8) | 5 (4.7) | |

| Student | 157 (64.9) | 56 (41.2) | 101 (95.3) |

| Case | All (n = 242) | Millennials (n = 136) | Z Generation (n = 106) | Stat. (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 0.1 (0.7670) | |||

| A | 9 (3.7) | 6 (4.4) | 3 (2.8) | |

| B | 160 (66.1) | 91 (66.9) | 69 (65.1) | |

| C | 61 (25.2) | 34 (25.0) | 27 (25.5) | |

| Other | 12 (5.0) | 5 (3.7) | 7 (6.6) | |

| Second | 1.1 (0.2845) | |||

| A | 12 (5) | 8 (5.9) | 4 (3.8) | |

| B | 69 (28.5) | 40 (29.4) | 29 (27.4) | |

| C | 153 (63.2) | 82 (60.3) | 71 (67.0) | |

| Other | 8 (3.3) | 6 (4.4) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Third | 5.5 (0.0187) | |||

| A | 67 (27.7) | 42 (30.9) | 25 (23.6) | |

| B | 23 (9.5) | 17 (12.5) | 6 (5.7) | |

| C | 137 (56.6) | 68 (50.0) | 69 (65.1) | |

| Other | 8 (3.3) | 6 (4.4) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Forth | 1.7 (0.1885) | |||

| A | 15 (6.2) | 5 (3.7) | 10 (9.4) | |

| B | 59 (24.4) | 31 (22.8) | 28 (26.4) | |

| C | 166 (68.6) | 98 (72.1) | 68 (64.2) | |

| Other | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aluaș, M.; Bolboacă, S.D.; Georgiu, B.M.; Porz, R.C.; Lucaciu, O.P. Perspectives on Ethics Related to Aesthetic Dental Practices Promoted in Social Media—A Cross-Sectional Study. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7040098

Aluaș M, Bolboacă SD, Georgiu BM, Porz RC, Lucaciu OP. Perspectives on Ethics Related to Aesthetic Dental Practices Promoted in Social Media—A Cross-Sectional Study. Prosthesis. 2025; 7(4):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7040098

Chicago/Turabian StyleAluaș, Maria, Sorana D. Bolboacă, Bianca M. Georgiu, Rouven C. Porz, and Ondine P. Lucaciu. 2025. "Perspectives on Ethics Related to Aesthetic Dental Practices Promoted in Social Media—A Cross-Sectional Study" Prosthesis 7, no. 4: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7040098

APA StyleAluaș, M., Bolboacă, S. D., Georgiu, B. M., Porz, R. C., & Lucaciu, O. P. (2025). Perspectives on Ethics Related to Aesthetic Dental Practices Promoted in Social Media—A Cross-Sectional Study. Prosthesis, 7(4), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7040098