Lithium Silicate-Based Glass Ceramics in Dentistry: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Microstructure

- Lithium disilicate (Li2Si2O5): a layered silicate (i.e., phyllosilicate) in which silicon shares three oxygen atoms with its neighbouring atoms; this phase exists between 800 and 850 °C;

- Lithium metasilicate (Li2SiO3): a single-chain silicate (i.e., inosilicate) where silicon shares only two oxygen atoms; this phase is metastable and exists exclusively between 600 and 800 °C;

- Cristobalite (SiO2): a stable silica framework, i.e., tectosilicate, in which silicon shares all four oxygen atoms; this secondary phase crystallises following that of Li2Si2O5.

- Lithium disilicate ceramic (LDS): predominantly lithium disilicate (Li2Si2O5);

- Lithium metasilicate ceramic (LM): predominantly lithium metasilicate (Li2SiO3);

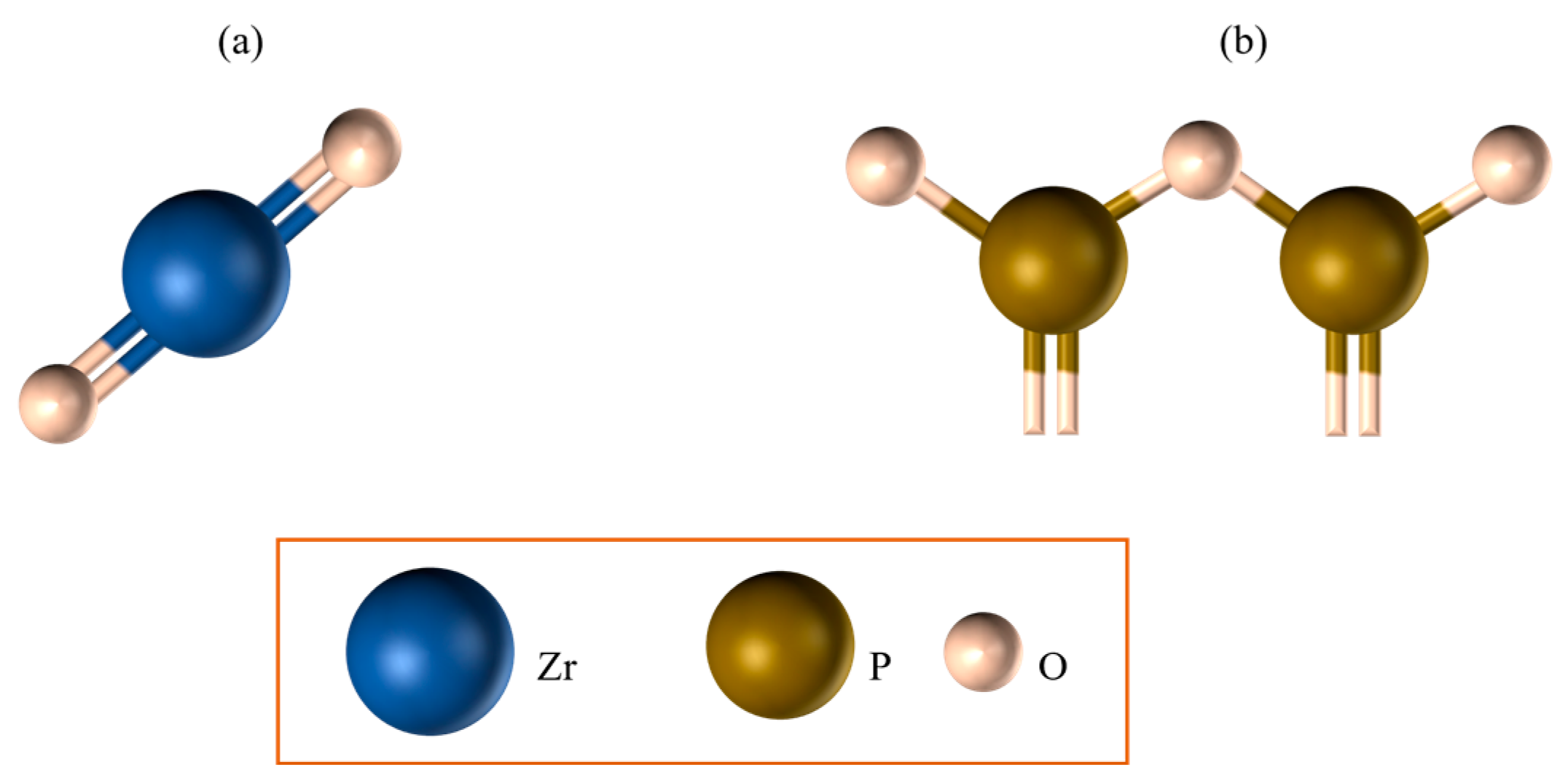

- Zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate (ZLS): biphasic lithium metasilicate/lithium disilicate (Li2SiO3/Li2Si2O5);

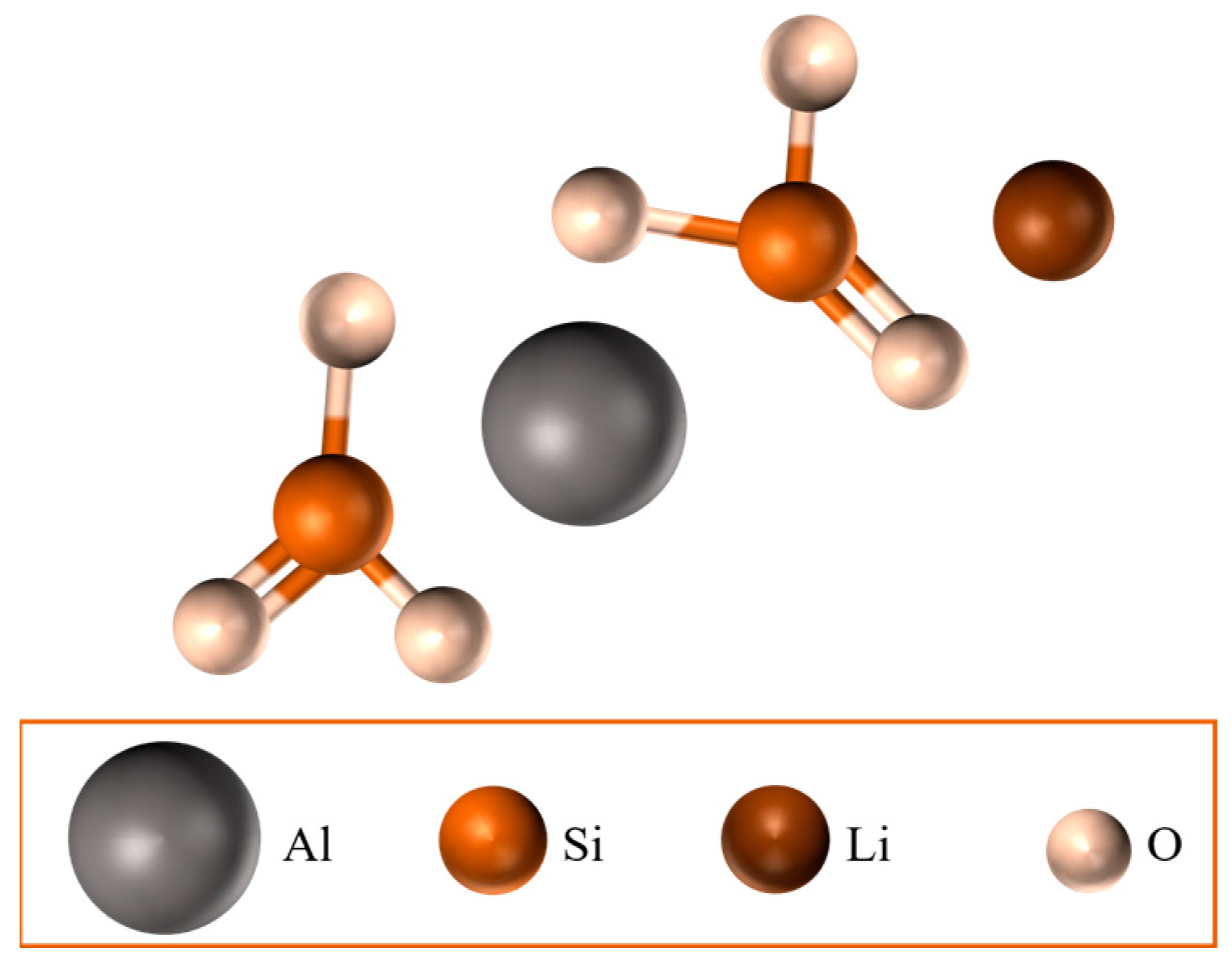

- Lithium aluminium disilicate (ALD): biphasic spodumene/lithium disilicate (LiAlSi2O6/Li2Si2O5).

2.1. Zirconia-Reinforced Lithium Silicate Ceramics (ZLSs)

2.2. Lithium–Aluminium Disilicates (ALDs)

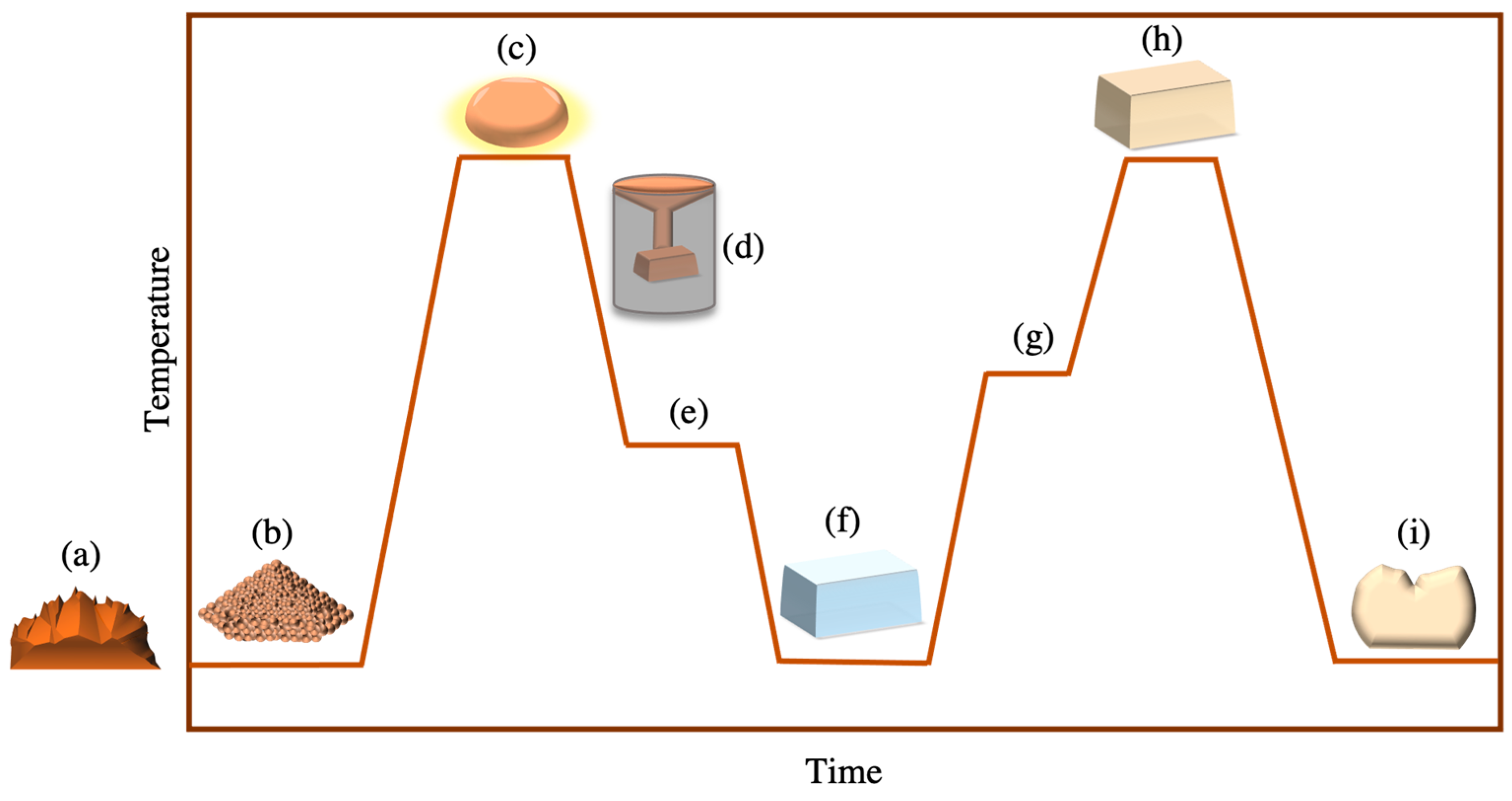

3. Manufacturing Techniques

3.1. Melting Casting Crystallisation Method

3.2. Powder Sintering Method

3.3. Sol–Gel Method

4. Strengthening Mechanisms

- Intrinsic strengthening mechanisms

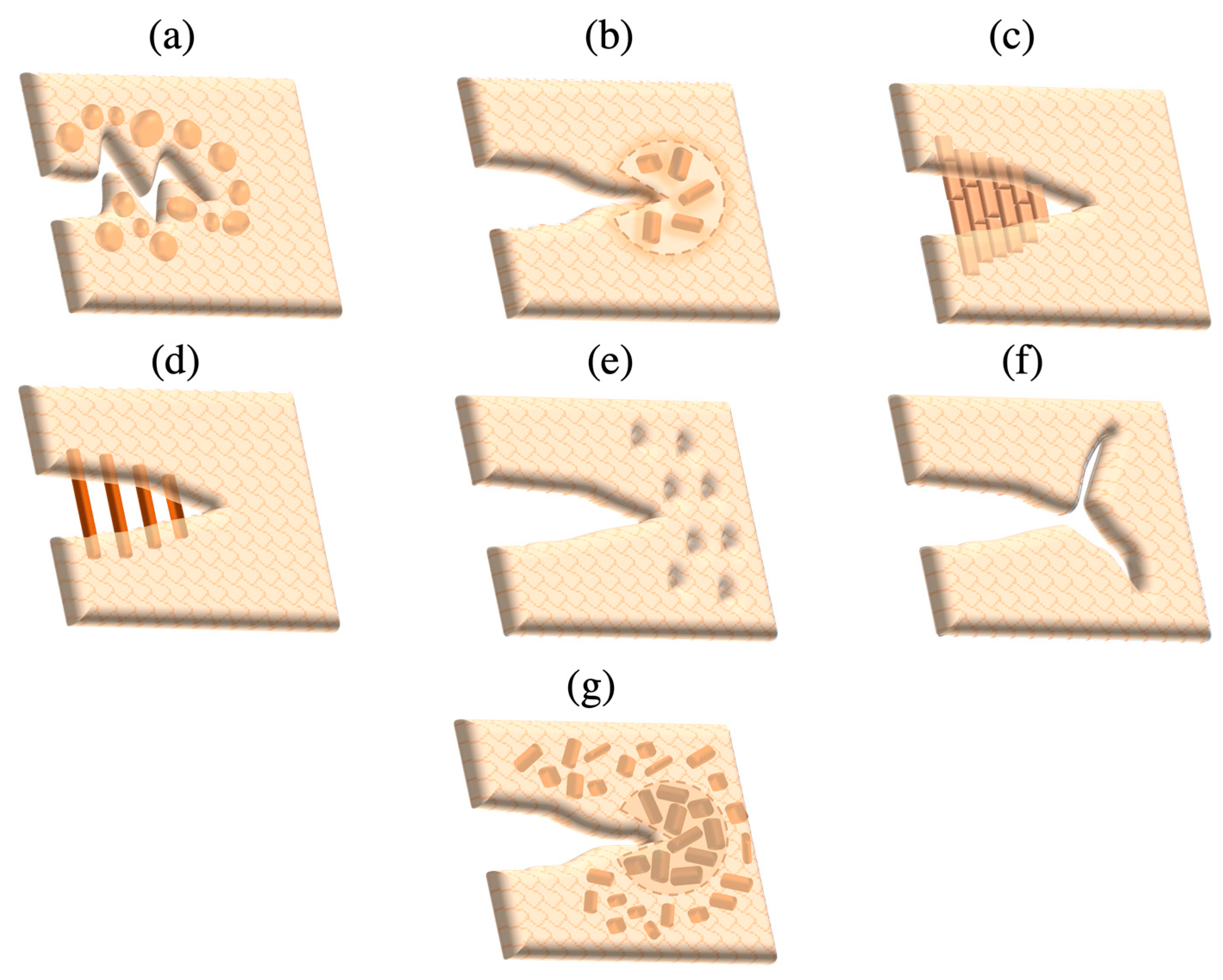

- Crack tip deflection: Added particles in the glass matrix act as obstacles deflecting the crack into an altered plane, increasing the surface area per distance of the crack and consequently causing crack advancement to be decelerated as extra energy is needed for its propagation.

- Crack tip shielding: This is triggered by high stresses within the crack tip vicinity, where residual stresses arise from mismatches in the coefficients of thermal expansion (CTE) between crystalline particles and the glass matrix; the greater CTE of crystals than that of the surrounding glass matrix stimulates compressive stresses at the crack tip that minimise its opening.

- Crack bridging: In ceramic networks of high crystalline density, cracks spread in an inter-granular manner, thereby causing friction to be generated between the grains along crack surfaces, triggering grain pull-out, frictional interlocking and bridging, and thus impeding further crack extension. Bridging can also be accomplished via the reinforcement of added fibres or whiskers within the ceramic matrix.

- Microcrack formation and crack branching: Concentrated stress around the crack tip generates microcracks within adjacent inherent flaws and grain boundaries oriented perpendicularly to the stress plane. Microcracks dissolve the crack expansion energy within the tip region, thereby hindering further crack advancement. Branching at the crack tip also acts to delay crack motion by increasing the crack surface area.

- Transformation toughening: Stresses surrounding the crack tip region prompt crystalline phase transformations that are accompanied by volumetric expansion exerting favourable compressive residual stresses coalescing the crack tip.

- Extrinsic strengthening mechanisms

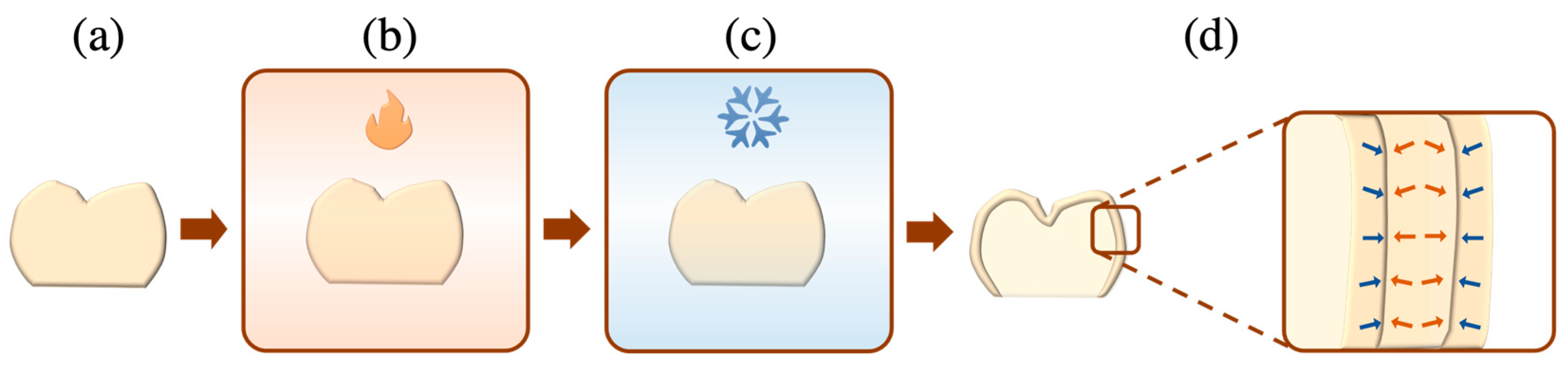

- Thermal tempering: This involves the controlled heating of a ceramic to a temperature that is slightly above the glass transition point (Tg) and beneath the softening point (Ts), creating a rigid exterior surface that envelopes a molten centre [45]. Upon cooling, the molten core contracts and a temperature gradient is generated between the surface and bulk, yielding residual compressive stresses within the former and inner residual tensile stresses within the latter (Figure 6). Therefore, to fracture tempered ceramic restorations, externally applied tensile loads must counter the residual compressive stresses of the ceramic surface.

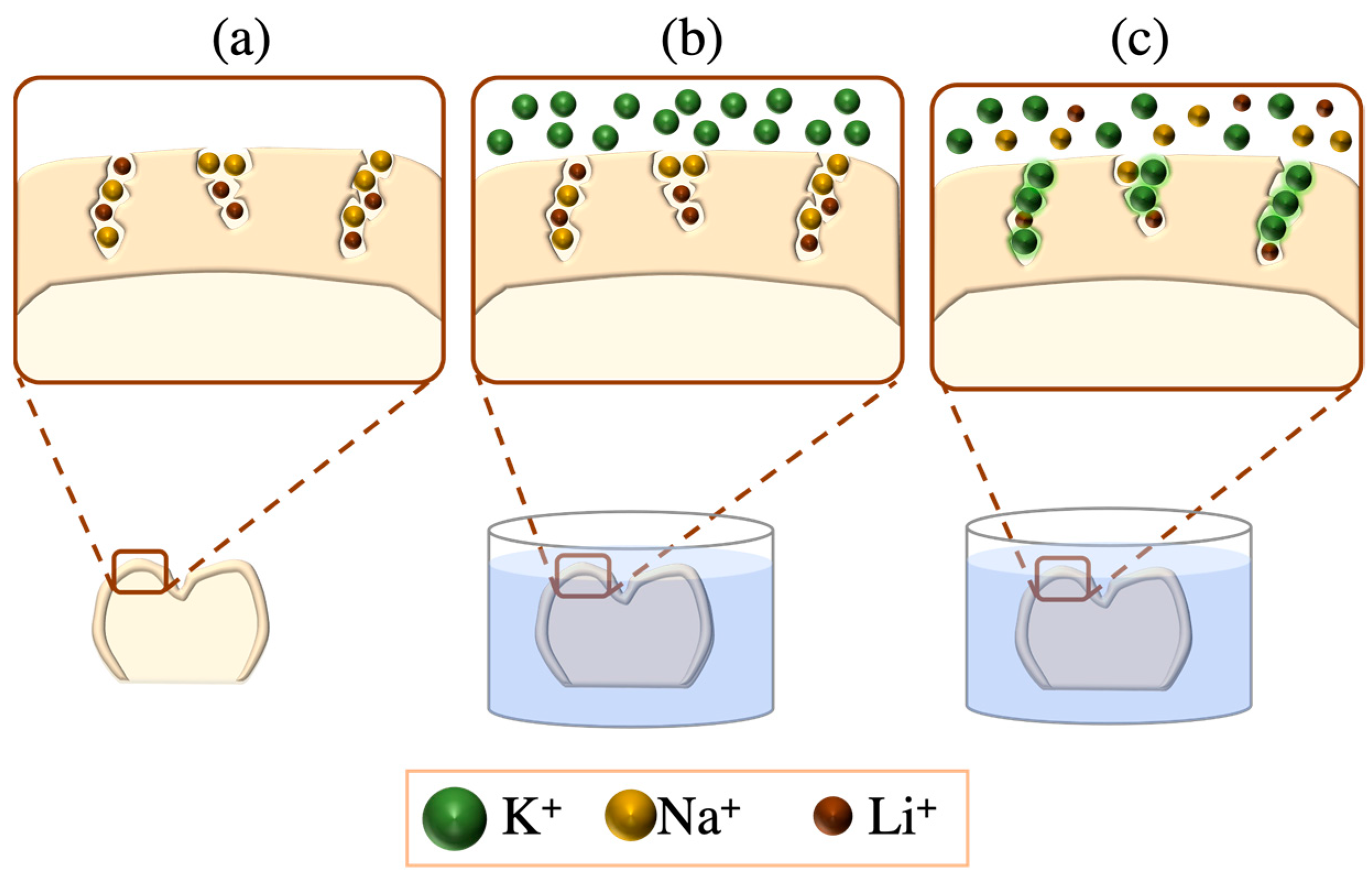

- Chemical tempering: This is also known as ion exchange or ion stuffing, where the exchange of different sized ions at the outer ceramic surfaces yields residual compressive stresses as the larger ions swap those of smaller sizes. This is achieved via the immersion of the LSC in a molten potassium nitrate (KNO3) salt bath; smaller-sized ions on the LSC surface (e.g., Na+ and Li+) are substituted by larger ions in the salt bath (e.g., K+). The resultant chemically tempered ceramics are electroneutral by virtue of the equivalent counter ion flux diffusion (Figure 7) [43,46,47].

5. Fabrication Methods

5.1. Heat Pressing

5.2. CAD-CAM Technology

- Computer-aided manufacturing: Upon finalising the LSC restoration design, it can be manufactured via subtractive (SM), additive (AM) or hybrid SM and AM mechanisms.

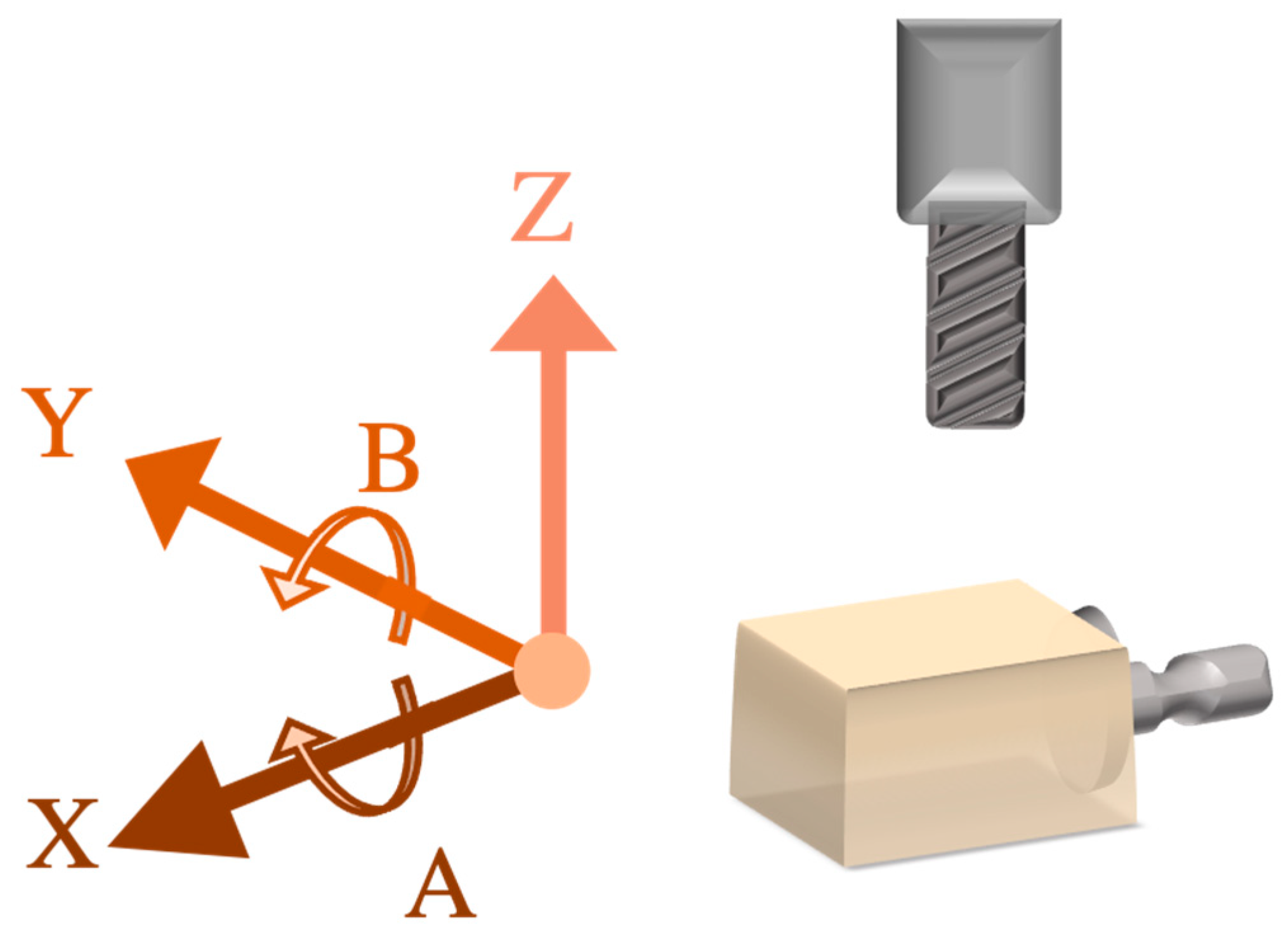

5.2.1. Subtractive Manufacturing

5.2.2. Additive Manufacturing

- Material jetting (MJ): This is also recognised as direct inkjet printing, in which a layer of tiny droplets of the print material (i.e., ink) are selectively deposited onto a build platform, where the latter is heated or exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation to the facilitate immediate photopolymerisation of the jetted layer ink before the subsequent ink layer is added. Ceramic particles can be suspended into water, organic solvents or wax solutions to create the ceramic ink needed to fabricate dental restorations via the material jetting method.

- Vat polymerisation (VP): This entails the selective photocuring of radiation-sensitive liquid polymers contained within a tank (i.e., vat). This is the most frequently used additive method for fabricating dental ceramics, wherein ceramic suspensions are developed through the incorporation of resin polymers in high concentrations within ceramics powders. VP can be further subdivided into three main technologies; stereolithography (in which a concentrated UV-laser beam is directed onto a photosensitive liquid resin generating layers of the desired object through the crosslinking of the polymers), digital light processing (a digital UV screen simultaneously deposits and photocures an entire layer of photopolymerisable liquid) and continuous liquid interface production (a vat with transparent base serves as an oxygen-permeable window, where resin polymerisation is prevented and can flow freely, creating continuous printed material rather than layered material).

- Binder jetting (BJ): Binding liquid agents and powder print materials are deposited in alternating layers to create the final build, and the binder acts as an adhesive between powder layers. Layer-wise slurry deposition is a variant of BJ that uses a ceramic slip instead of dry powder.

- Material extrusion (ME): This is also known as fusion deposition modelling, direct ink writing or robocasting, wherein a heated nozzle contains a thermoplastic filament that is melted into an ink and deposited in layers to generate the 3D object. The fabrication of LSCS via ME is achieved by using a ceramic slurry—composed of chemically or heat-bonded ceramic particles—as the ink material.

- Powder bed fusion (PBF): In this process, a powdered material is selectively melted and fused via laser or electron beams to fabricate the final product. This method can be further subdivided into the following: selective laser sintering, selective laser melting and electron beam Melting. This method has not been successful in fabricating LSC restorations, due to the laser-induced cracks that result from drastic temperature fluctuations.

- Sheet lamination (SL): In this process, multiple layered sheets of the build are superimposed, laminated and then cut into the final shape using lasers or CNC milling devices.

- Direct energy deposition (DED): Deposited materials are concurrently melted and fused via focused thermal energy into their final morphologies. Based on the type of thermal energy employed (focused electron beam or focused laser), this method is further divided into laser engineering net shape or electron beam additive manufacturing, respectively.

6. Properties

6.1. Biocompatibility

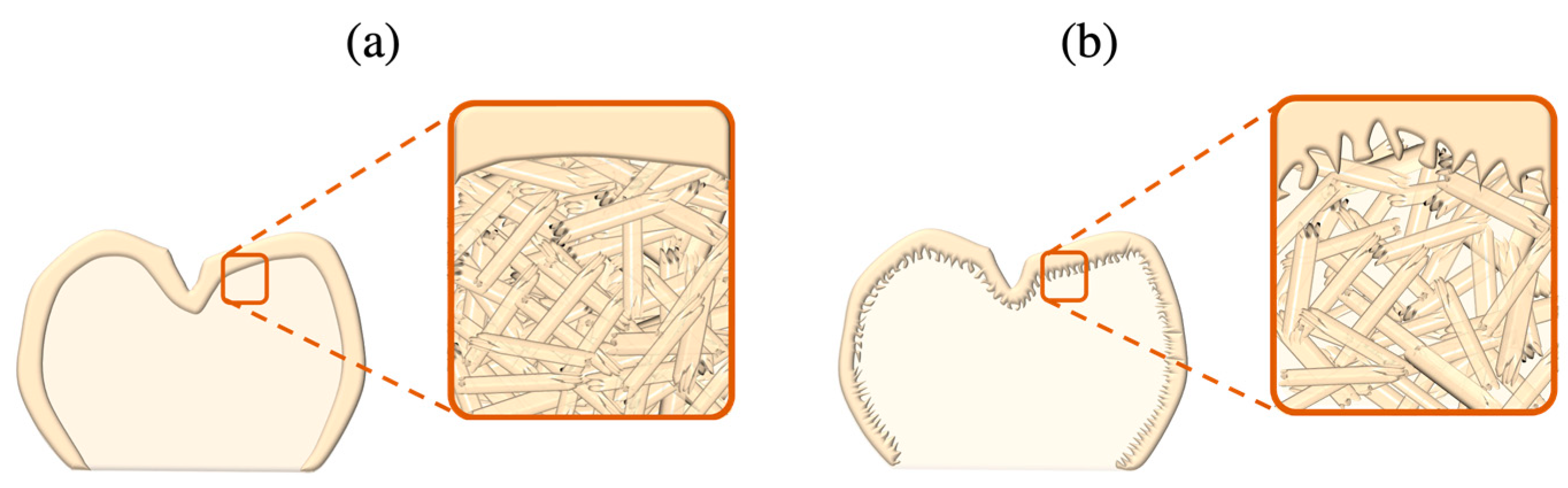

6.2. Mechanical Properties

6.3. Optical Properties

7. Surface Treatments of LSCs

7.1. Intaglio Surface Treatments

7.1.1. Mechanical Surface Treatments

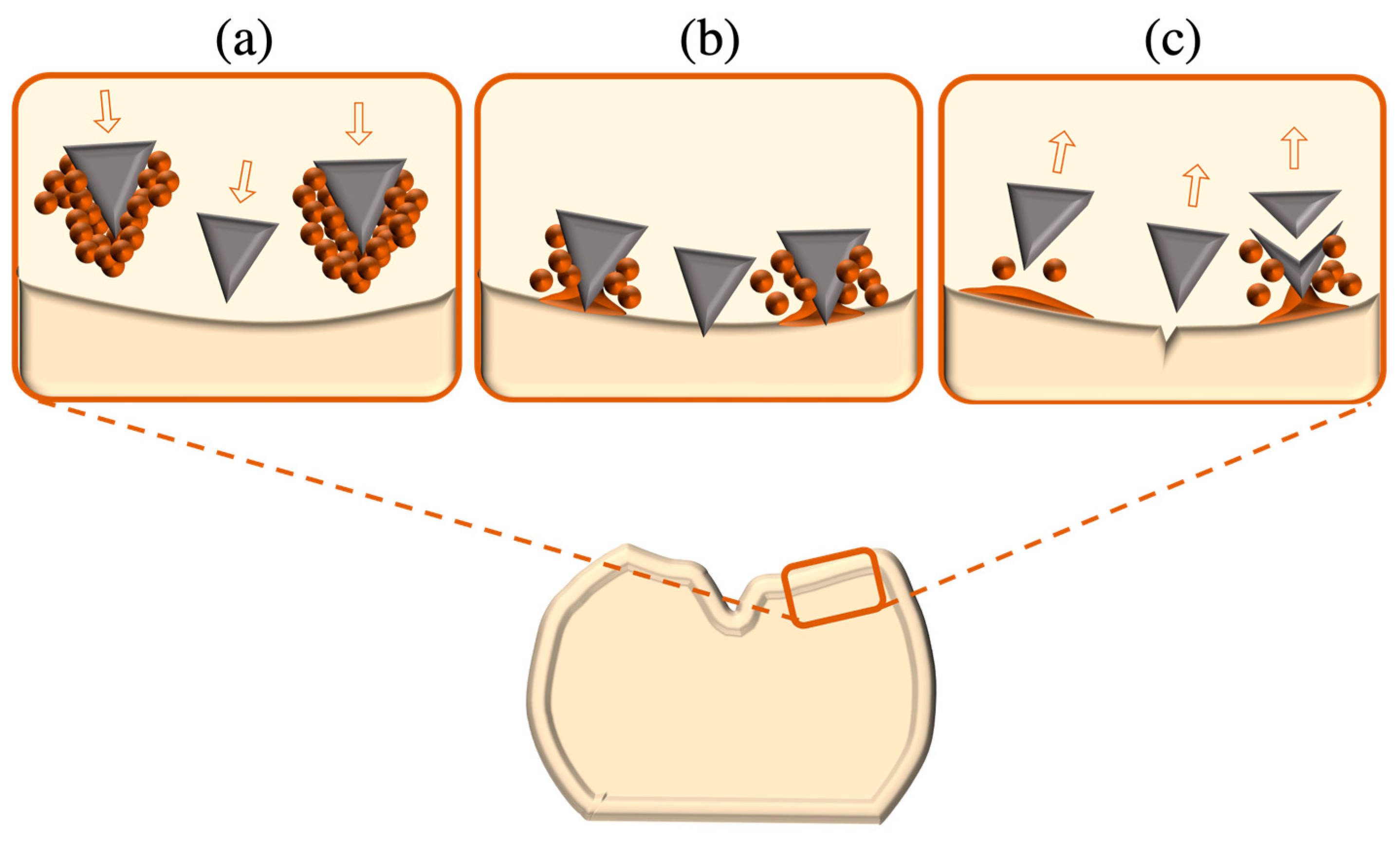

- Airborne particle abrasion: Sandblasting with alumina oxide or silica oxide particles creates surface alterations that are determined by the size, hardness, pressure, incident angle and velocity of abrading particles and the distance between the substrate and sandblasting nozzle. Since sharp edges of alumina particles chip away weaker glassy phases creating microcracks, this method could have a degrading impact on LSCs with high glass contents [108,109].

- Laser irradiation: Heat introduction by a laser creates conchoidal (scalloped) defects within LSC surfaces, promoting the micromechanical retention needed for bonding. Erbium: yttrium aluminium garnet laser is commonly employed [110,111], as is CO2 laser, to treat LSC surfaces, owing to their complete absorption of CO2 wavelengths [112]. Recently, femtosecond laser treatments have been explored to treat LSC surfaces, wherein ultrashort optical pulses are generated per femtosecond, producing micro-retentive topographical changes [113].

7.1.2. Chemical Surface Treatments

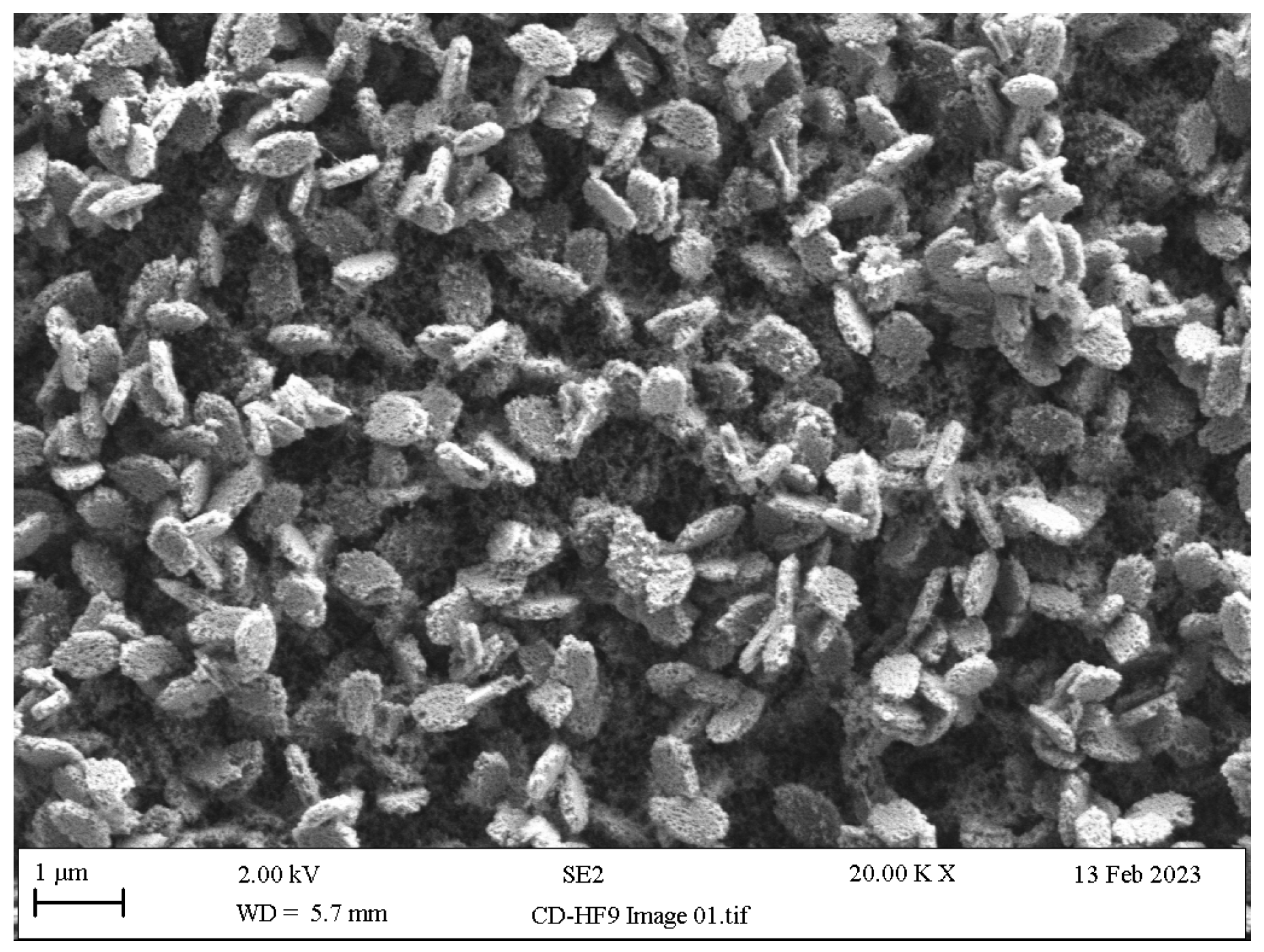

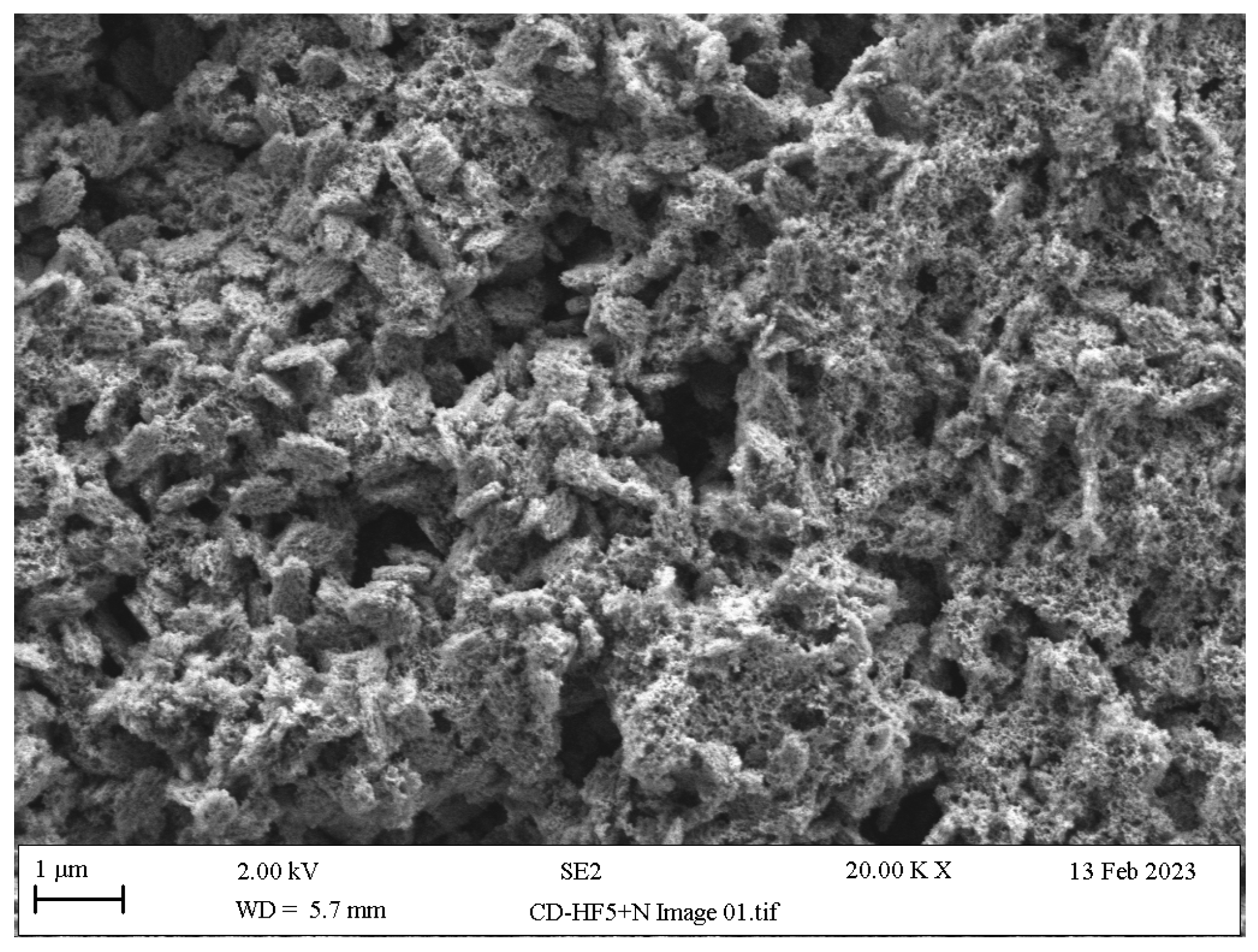

- Hydrofluoric acid etching: The etching of LSC restorations is most frequently performed using buffered hydrofluoric acid (HF), since the unbuffered version of HF is highly caustic; most HF etching products offered in the dental market are buffered down to 5% or 10% concentrations through the addition of an ammonium fluoride (NH4F) buffering agent. HF reacts with silica in the glassy matrix, yielding a tetrafluorosilane compound (SiF4), succeeded by a hexafluorosilicate complex ([SiF6]−2) and subsequently soluble hydrofluorosilicic acid (H2[SiF6]) that is washed away along with the glassy matrix, hence exposing the underlying crystalline network (Figure 9) and providing the retention needed for LSC cementation [69,107,114,115].

- Acid etching with HF substitutes: Owing to the toxic and corrosive potential of HF as a result of its low dissociation constant, it can easily penetrate dermal, epidermal and mucosal tissues entering into the blood stream; however, its slow interaction with nerve endings delays the burning sensation. Hence, HF must be handled with utmost caution in extra-oral conditions, only with adequate ventilation and protective gear [107,128]. Attempts in minimising occupational hazards with HF have led to the exploration of alternative etching modalities with agents of reduced acidic capacities:

- Acidulated phosphate fluoride (APF): This is composed of 1.23% fluoride ions derived from sodium fluoride and hydrofluoric acid that become acidified through the addition of phosphoric acid. APF has proven to be a more efficient etchant for leucite-based ceramics than for LDS, due to the faster crystalline dissolution rate in the former [130], with greater bond strengths reported upon longer APF etching durations [107].

- Ammonium bifluoride (ABF): Herein, a linear etching pattern is formed due to the targeted action of ABF on grain boundaries and pre-existing cracks within LSCs, reacting with the silica matrix and generating silicon tetrafluoride and ammonium fluoride:As ABF is less toxic than HF, longer etching times are required to create etching patterns similar to those of HF of similar concentrations. While etching with ABF results in adequate bonding strengths, it is mainly used as an intermediate for fabricating HF [107,131].4 NH4HF2 +SiO2 → SiF4 + 4 NH4F + 2 H2O

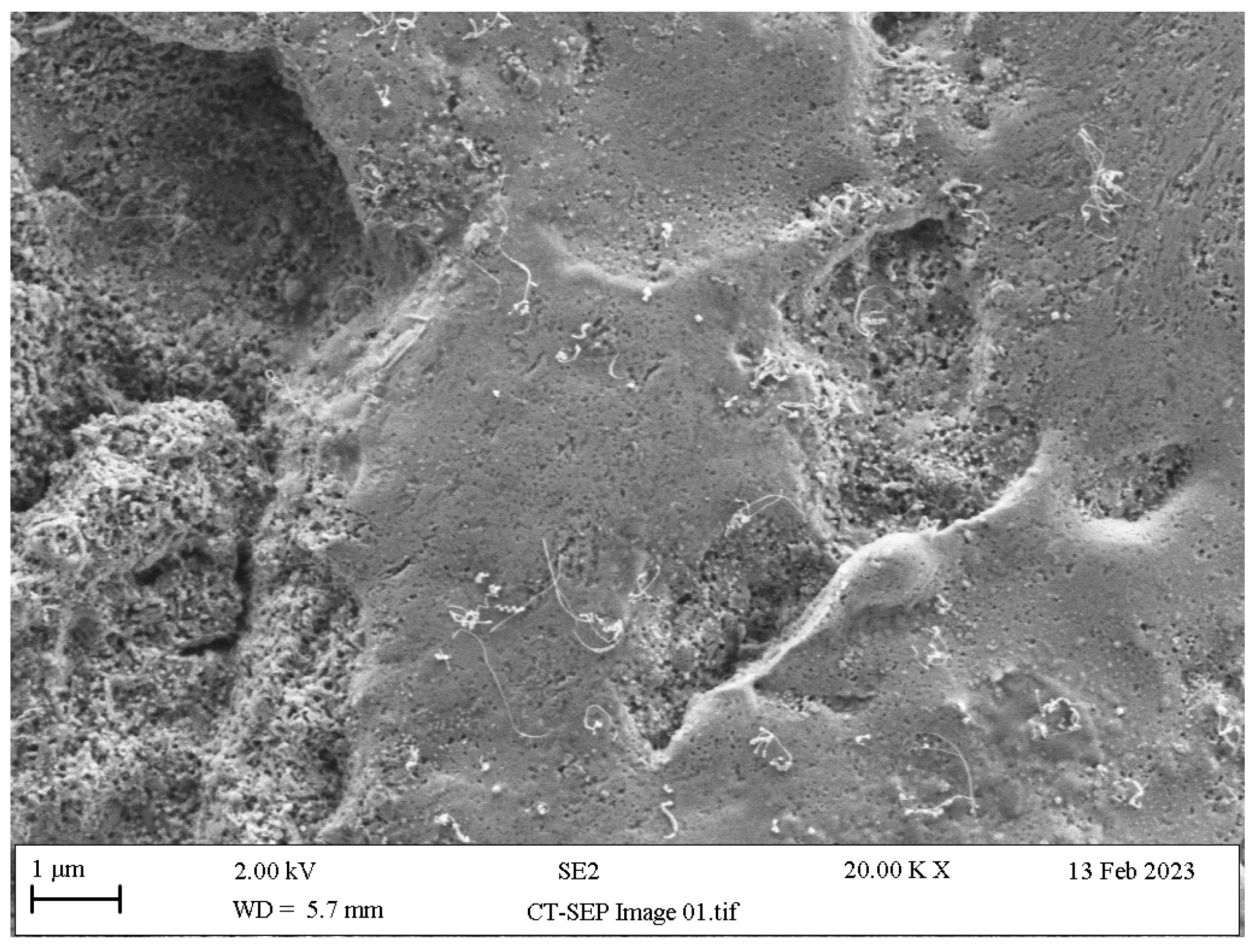

- Ammonium polyfluoride (AP): This is provided within the composition of self-etching ceramic primers (SEP), serves as a silane coupling agent stabiliser and, despite its notably low acidity, has been shown to create sufficient micro-retentive etching patterns in LSCs [132,133] (Figure 11) and reliable adhesion to the tooth substrate [134,135].

- Acid neutralisation: Alkaline agents such as calcium gluconate, sodium bicarbonate and calcium carbonate have been used to neutralise the acidity of LSC surfaces caused by HF residues through an acid–base reaction that produces sodium fluoride and calcium fluoride salts and that arrests further etching by HF residues by generating adverse topographical changes (Figure 12) [136,137,138,139,140,141].HF + Na2CO3 + Ca2CO3 → NaF + CaF2 + H2CO3

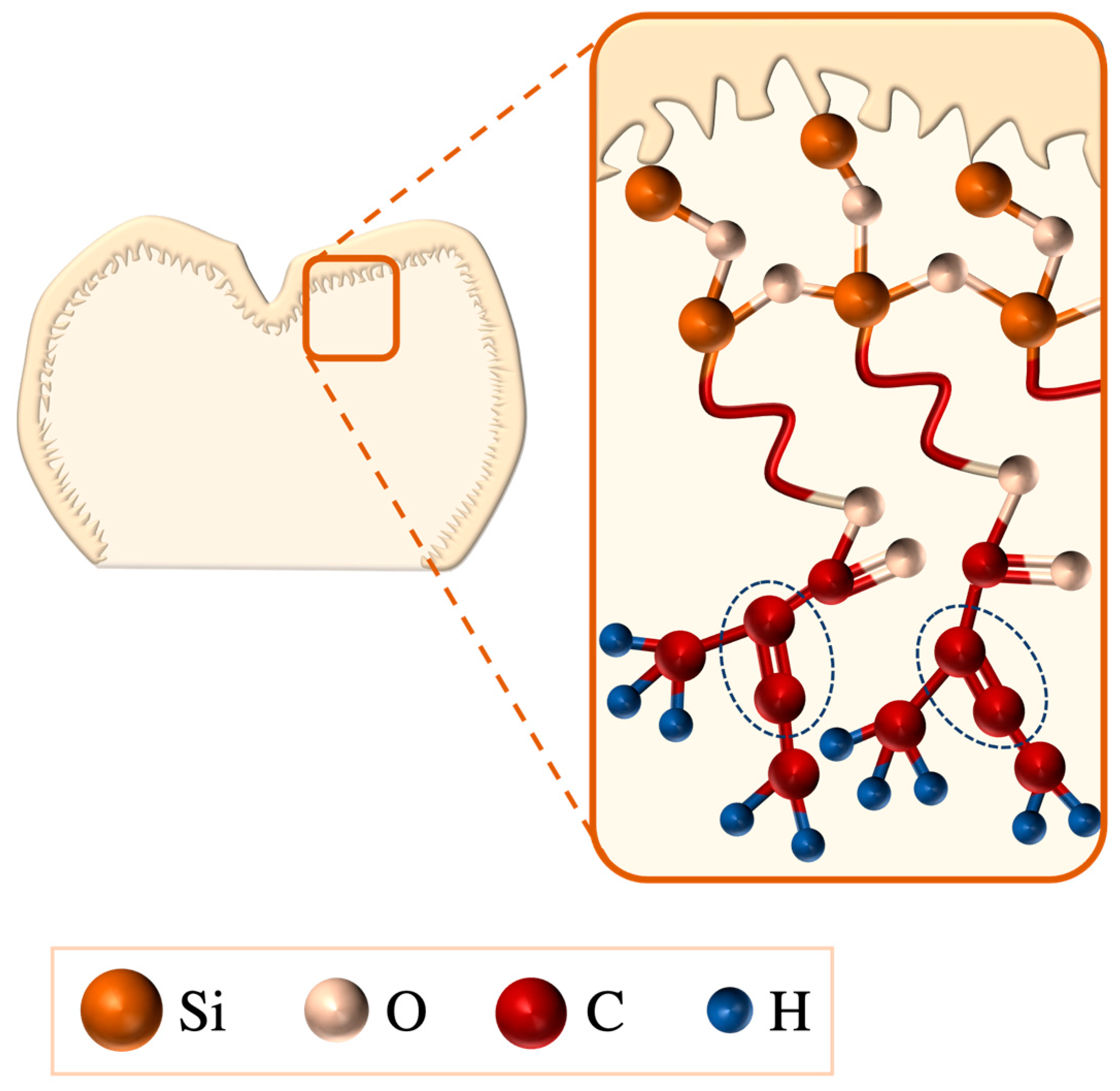

- Salinisation: Silanes comprise a γ-methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane molecule that enables bonding between LSC and resin surfaces via its bifunctional monomers; the alkoxy group (methacryloxy, Si-O-CH3) reacts with the LSCs hydroxyl group (-OH), forming silanol (Si-OH), and, on the silane monomer end, a methacrylate group (C=C) reacts with the organic-matrix monomers of the resin, resulting in a bridging siloxane compound (-Si-O-Si-O-) (Figure 13) that improves LSC wettability and resin penetration [107,109,145]. To achieve the optimal bonding effects of a silane coating, LSCs must be pre-treated, e.g., etched, to increase their roughness [107].

- Plasma treatment: When low-temperature atmospheric-pressure plasma is applied to LSCs, it acts at a molecular level without violating bulk integrity, thereby decontaminating LSCs and increasing their surface energy. Moreover, the dry conditions in which plasma treatment is carried out eliminate the risk of strength-limiting hydrolytic damage, yielding sufficient bond strength values for LSCs bonding to resin cements [146,147,148].

- 10-methacryloyloxyidecyl-dihydrogenphosphate application (10-MDP): 10-MDP is a phosphate ester monomer found in primers as well as resin cements that can chemically react with zirconia by forming a bond with its hydroxyl groups. It has displayed promising bonding performance when used following the silanisation of HF-etched ZLS surfaces [149,150].

7.1.3. Chemo-Mechanical Surface Treatments

7.2. External Surface Treatments

8. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stookey, S. Catalyzed crystallization of glass in theory and practice. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1959, 51, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, G. Design and properties of glass-ceramics. Ann. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1992, 22, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, A.; Chu, T.M.G. The science and application of IPS e. Max dental ceramic. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Vardhaman, S.; Rodrigues, C.S.; Lawn, B.R. A Critical Review of Dental Lithia-Based Glass-Ceramics. J. Dent. Res. 2023, 102, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubauer, J.; Belli, R.; Peterlik, H.; Hurle, K.; Lohbauer, U. Grasping the Lithium hype: Insights into modern dental Lithium Silicate glass-ceramics. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarone, F.; Ruggiero, G.; Leone, R.; Breschi, L.; Leuci, S.; Sorrentino, R. Zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate (ZLS) mechanical and biological properties: A literature review. J. Dent. 2021, 109, 103661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phark, J.H.; Duarte, S., Jr. Microstructural considerations for novel lithium disilicate glass ceramics: A review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 34, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeCeanne, A.V.; Fry, A.L.; Wilkinson, C.J.; Dittmer, M.; Ritzberger, C.; Rampf, M.; Mauro, J.C. Experimental analysis and modeling of the Knoop hardness of lithium disilicate glass-ceramics containing lithium tantalate as a secondary phase. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2022, 585, 121540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmer, M.; Ritzberger, C.; Höland, W.; Rampf, M. Controlled precipitation of lithium disilicate (Li2Si2O5) and lithium niobate (LiNbO3) or lithium tantalate (LiTaO3) in glass-ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 38, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCeanne, A.V.; Fry, A.L.; Wilkinson, C.J.; Dittmer, M.; Ritzberger, C.; Rampf, M.; Mauro, J.C. Examining the phase evolution of lithium disilicate glass-ceramics with lithium tantalate as a secondary phase. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 105, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanasirmkit, K.; Srimaneepong, V.; Kanchanatawewat, K.; Monmaturapoj, N.; Thunyakitpisal, P.; Jinawath, S. Improving shear bond strength between feldspathic porcelain and zirconia substructure with lithium disilicate glass-ceramic liner. Dent. Mater. J. 2015, 34, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thammajaruk, P.; Buranadham, S.; Guazzato, M.; Swain, M.V. Influence of ceramic-coating techniques on composite-zirconia bonding: Strain energy release rate evaluation. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, e31–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thammajaruk, P.; Buranadham, S.; Thanatvarakorn, O.; Ferrari, M.; Guazzato, M. Influence of glass-ceramic coating on composite zirconia bonding and its characterization. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manziuc, M.; Kui, A.; Chisnoiu, A.; Labuneț, A.; Negucioiu, M.; Ispas, A.; Buduru, S. Zirconia-Reinforced Lithium Silicate Ceramic in Digital Dentistry: A Comprehensive Literature Review of Our Current Understanding. Medicina 2023, 59, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrentino, R.; Ruggiero, G.; Di Mauro, M.I.; Breschi, L.; Leuci, S.; Zarone, F. Optical behaviors, surface treatment, adhesion, and clinical indications of zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate (ZLS): A narrative review. J. Dent. 2021, 112, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, I.V.; Finck, N.S.; Rodrigues, C.S.; Moraes, R.R. Laboratory processing methods and bonding to glass ceramics: Systematic review. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2024, 129, 103572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacher, E.; França, R. Dental Biomaterials; World Scientific: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, A.L.; Rodrigues, C.S.; Guiberteau, F.; Zhang, Y. Microstructural development during crystallization firing of a dental-grade nanostructured lithia-zirconia glass-ceramic. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 5728–5739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simba, B.G.; Ribeiro, M.V.; Alves, M.F.R.P.; Vasconcelos Amarante, J.E.; Strecker, K.; dos Santos, C. Effect of the temperature on the mechanical properties and translucency of lithium silicate dental glass-ceramic. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 9933–9940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, R. Lithium disilicate-based glass-ceramics. In Dental Biomaterials; World Scientific: Singapore, 2019; pp. 173–209. [Google Scholar]

- Belli, R.; Wendler, M.; de Ligny, D.; Cicconi, M.R.; Petschelt, A.; Peterlik, H.; Lohbauer, U. Chairside CAD/CAM materials. Part 1: Measurement of elastic constants and microstructural characterization. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendler, M.; Belli, R.; Petschelt, A.; Mevec, D.; Harrer, W.; Lube, T.; Danzer, R.; Lohbauer, U. Chairside CAD/CAM materials. Part 2: Flexural strength testing. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krüger, S.; Deubener, J.; Ritzberger, C.; Höland, W. Nucleation kinetics of lithium metasilicate in ZrO2-bearing lithium disilicate glasses for dental application. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 2013, 4, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentsply Sirona. Scientific Documentation Celtra Duo. 2017. Available online: https://www.dentsplysirona.com/content/dam/master/education/documents/upload/6/67835_Celtra_Duo_Broschyr_LowRes.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- von Maltzahn, N.F.; El Meniawy, O.I.; Breitenbuecher, N.; Kohorst, P.; Stiesch, M.; Eisenburger, M. Fracture Strength of Ceramic Posterior Occlusal Veneers for Functional Rehabilitation of an Abrasive Dentition. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2018, 31, 451–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieper, K.; Wille, S.; Kern, M. Fracture strength of lithium disilicate crowns compared to polymer-infiltrated ceramic-network and zirconia reinforced lithium silicate crowns. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 74, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsaka, S.E.; Elnaghy, A.M. Mechanical properties of zirconia reinforced lithium silicate glass-ceramic. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Johani, H.; Haider, J.; Silikas, N.; Satterthwaite, J. Effect of repeated firing on the topographical, optical, and mechanical properties of fully crystallized lithium silicate-based ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 741.e1–741.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Nde, C.; Campos, T.M.; Paz, I.S.; Machado, J.P.; Bottino, M.A.; Cesar, P.F.; de Melo, R.M. Microstructure characterization and SCG of newly engineered dental ceramics. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monmaturapoj, N.; Lawita, P.; Thepsuwan, W. Characterisation and properties of lithium disilicate glass ceramics in the SiO2-Li2OK2O-Al2O3 system for dental applications. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 2013, 763838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurle, K.; Lubauer, J.; Belli, R.; Lohbauer, U. On the assignment of quartz-like LiAlSi2O6—SiO2 solid solutions in dental lithium silicate glass-ceramics: Virgilite, high quartz, low quartz or stuffed quartz derivatives? Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 1558–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazerian, M.; Dutra Zanotto, E. History and trends of bioactive glass-ceramics. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2016, 104, 1231–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Li, K.; Ning, C. Sintering properties of sol–gel derived lithium disilicate glass ceramics. J. Solgel Sci. Technol. 2018, 87, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Engqvist, H.; Xia, W. Glass–ceramics in dentistry: A review. Materials 2020, 13, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yao, X.; Zhang, R.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; et al. Recent advances in glass-ceramics: Performance and toughening mechanisms in restorative dentistry. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2023, 112, e35334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalkhali, Z.; Yekta, B.E.; Marghussian, V. Preparation of lithium disilicate glass-ceramics as dental bridge material. J. Ceram. Sci. Technol. 2014, 5, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Kou, H.; Ning, C. Sintering and mechanical properties of lithium disilicate glass-ceramics prepared by sol-gel method. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2021, 552, 120443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, R.L.; Ferracane, J.; Powers, J.M. Craig’s Restorative Dental Materials-e-Book, 14th ed.; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazy, M.H.; Madina, M.M.; Aboushelib, M.N. Influence of fabrication techniques and artificial aging on the fracture resistance of different cantilever zirconia fixed dental prostheses. J. Adhes. Dent. 2012, 14, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gonzaga, C.C.; Cesar, P.F.; Miranda, W.G.; Yoshimura, H.N. Slow crack growth and reliability of dental ceramics. Dent. Mater. 2011, 27, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rösler, J.; Harders, H.; Bäker, M. Mechanical Behaviour of Engineering Materials: Metals, Ceramics, Polymers, and Composites; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy, A.; Shenoy, N. Dental ceramics: An update. J. Conserv. Dent. 2010, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruales-Carrera, E.; Dal Bó, M.; Fernandes das Neves, W.; Fredel, M.C.; Maziero Volpato, C.A.; Hotza, D. Chemical tempering of feldspathic porcelain for dentistry applications: A review. Open Ceram. 2022, 9, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Bei, G. Toughening Mechanisms in Nanolayered MAX Phase Ceramics—A Review. Materials 2017, 10, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Chen, Z.X.; Zhang, Y.M.; Li, X.C.; Meng, M.; He, L.; Zhang, Z.Z. Improved reliability of mechanical behavior for a thermal tempered lithium disilicate glass-ceramic by regulating the cooling rate. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 114, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Cryst. A 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.C.; Meng, M.; Li, D.; Wei, R.; He, L.; Zhang, S.F. Strengthening and toughening of a multi-component lithium disilicate glass-ceramic by ion-exchange. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 4635–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, E.; Giordano, R. Ceramics overview: Classification by microstructure and processing methods. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2010, 31, 682–684. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M.J.; Costa, M.D.; Rubo, J.H.; Pegoraro, L.F.; Santos, G.C., Jr. Current all-ceramic systems in dentistry: A review. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2015, 36, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, T.; Hotta, Y.; Kunii, J.; Kuriyama, S.; Tamaki, Y. A review of dental CAD/CAM: Current status and future perspectives from 20 years of experience. Dent. Mater. J. 2009, 28, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samra, A.P.B.; Morais, E.; Mazur, R.F.; Vieira, S.R.; Rached, R.N. CAD/CAM in dentistry—A critical review. Rev. Odonto Ciência. 2016, 31, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Hotta, Y. CAD/CAM systems available for the fabrication of crown and bridge restorations. Aust. Dent. J. 2011, 56 (Suppl. S1), 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rekow, E.D. Digital dentistry: The new state of the art—Is it disruptive or destructive? Dent. Mater. 2020, 36, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkyilmaz, I.; Wilkins, G.N. Milling Machines in Dentistry: A Swiftly Evolving Technology. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2021, 32, 2259–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Noort, R. The future of dental devices is digital. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abduo, J.; Lyons, K.; Bennamoun, M. Trends in computer-aided manufacturing in prosthodontics: A review of the available streams. Int. J. Dent. 2014, 2014, 783948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galante, R.; Figueiredo-Pina, C.G.; Serro, A.P. Additive manufacturing of ceramics for dental applications: A review. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 825–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Hamad, K.Q.; Al-Rashdan, B.A.; Ayyad, J.Q.; Al Omrani, L.M.; Sharoh, A.M.; Al Nimri, A.M.; Al-Kaff, F.T. Additive Manufacturing of Dental Ceramics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 31, e67–e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tigmeanu, C.V.; Ardelean, L.C.; Rusu, L.-C.; Negrutiu, M.-L. Additive Manufactured Polymers in Dentistry, Current State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives-A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Wang, S.; Dong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, W. Recent progress in additive manufacturing of ceramic dental restorations. J. Mater. Res Technol. 2023, 26, 1028–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsico, C.; Carpenter, I.; Kutsch, J.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Arola, D. Additive manufacturing of lithium disilicate glass-ceramic by vat polymerization for dental appliances. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 2030–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhdar, Y.; Tuck, C.; Binner, J.; Terry, A.; Goodridge, R. Additive manufacturing of advanced ceramic materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 116, 100736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, S.; Gmeiner, R.; Schönherr, J.A.; Stampfl, J. Stereolithography-based additive manufacturing of lithium disilicate glass ceramic for dental applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020, 116, 111180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, C.; Li, Z.; Hao, L.; Li, Y. A comprehensive review on additive manufacturing of glass: Recent progress and future outlook. Mater. Des. 2023, 227, 111736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Chan, A.M.M. A virtual prototyping system for rapid product development. Comput. Aided Des. 2004, 36, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, C.; Stumpf, A. Dental Ceramics: Microstructure, Properties and Degradation; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lygre, H. Prosthodontic biomaterials and adverse reactions: A critical review of the clinical and research literature. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2002, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallineni, S.K.; Nuvvula, S.; Matinlinna, J.P.; Yiu, C.K.; King, N.M. Biocompatibility of various dental materials in contemporary dentistry: A narrative insight. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2013, 4, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, G.W.; Matinlinna, J.P. Insights on ceramics as dental materials. Part I: Ceramic material types in dentistry. Silicon 2011, 3, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulet, J.; Söderholm, K.; Longmate, J. Effects of treatment and storage conditions on ceramic/composite bond strength. J. Dent. Res. 1995, 74, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suprinity, V. Technical and Scientific Documentation; Vita Zahnfabrik: Bad Säckingen, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca Pedro, G.; Carvalho Geraldo, A.; Franco Aline, B.; Simone, K.; Avila Gisseli, B.; Dias Sergio, C. Zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate biocompatibility polished in different Stages-An In vitro study. J. Int. Dent. Med. Res. 2018, 11, 759–764. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, M.M.; Ali, I.A.; Khan, K.; Mattheos, N.; Murbay, S.; Matinlinna, J.P.; Neelakantan, P. The influence of surface roughening and polishing on microbial biofilm development on different ceramic materials. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 30, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavriqi, L.; Valente, F.; Murmura, G.; Sinjari, B.; Macrì, M.; Trubiani, O.; Caputi, S.; Traini, T. Lithium disilicate and zirconia reinforced lithium silicate glass-ceramics for CAD/CAM dental restorations: Biocompatibility, mechanical and microstructural properties after crystallization. J. Dent. 2022, 119, 104054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizo-Gorrita, M.; Luna-Oliva, I.; Serrera-Figallo, M.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, J.L.; Torres-Lagares, D. Comparison of Cytomorphometry and Early Cell Response of Human Gingival Fibroblast (HGFs) between Zirconium and New Zirconia-Reinforced Lithium Silicate Ceramics (ZLS). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denry, I.; Holloway, J.A. Ceramics for dental applications: A review. Materials 2010, 3, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Rawls, H.R.; Esquivel-Upshaw, J.F. Phillips’ Science of Dental Materials, 13th ed.; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bajraktarova-Valjakova, E.; Korunoska-Stevkovska, V.; Kapusevska, B.; Gigovski, N.; Bajraktarova-Misevska, C.; Grozdanov, A. Contemporary dental ceramic materials, a review: Chemical composition, physical and mechanical properties, indications for use. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mörmann, W.H.; Stawarczyk, B.; Ender, A.; Sener, B.; Attin, T.; Mehl, A. Wear characteristics of current aesthetic dental restorative CAD/CAM materials: Two-body wear, gloss retention, roughness and Martens hardness. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2013, 20, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, N.C.; Bansal, R.; Burgess, J.O. Wear, strength, modulus and hardness of CAD/CAM restorative materials. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, e275–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivoclar Vivadent. Scientific Documentation IPS e.max CAD. Available online: https://www.ivoclar.com/en_li/products/digital-processes/ips-e.max-cad (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Ritzberger, C.; Apel, E.; Höland, W.; Peschke, A.; Rheinberger, V.M. Properties and Clinical Application of Three Types of Dental Glass-Ceramics and Ceramics for CAD-CAM Technologies. Materials 2010, 3, 3700–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akhali, M.; Chaar, M.S.; Elsayed, A.; Samran, A.; Kern, M. Fracture resistance of ceramic and polymer-based occlusal veneer restorations. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 74, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Yoon, H.I.; Park, E.J. Load-bearing capacity of various CAD/CAM monolithic molar crowns under recommended occlusal thickness and reduced occlusal thickness conditions. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2017, 9, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamza, T.A.; Sherif, R.M. Fracture resistance of monolithic glass-ceramics versus bilayered zirconia-based restorations. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, e259–e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arcangelo, C.; Vanini, L.; Rondoni, G.D.; De Angelis, F. Wear properties of dental ceramics and porcelains compared with human enamel. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Haj Husain, N.; Dürr, T.; Özcan, M.; Brägger, U.; Joda, T. Mechanical stability of dental CAD-CAM restoration materials made of monolithic zirconia, lithium disilicate, and lithium disilicate–strengthened aluminosilicate glass-ceramic with and without fatigue conditions. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirel, M.; Diken Türksayar, A.A.; Donmez, M.B. Translucency, color stability, and biaxial flexural strength of advanced lithium disilicate ceramic after coffee thermocycling. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 35, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Johani, H.; Haider, J.; Silikas, N.; Satterthwaite, J. Effect of surface treatments on optical, topographical and mechanical properties of CAD/CAM reinforced lithium silicate glass ceramics. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, J.S.; Souza, L.F.B.; Pereira, G.K.R.; May, L.G. Surface properties and flexural fatigue strength of an advanced lithium disilicate. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 147, 106154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preis, V.; Behr, M.; Hahnel, S.; Rosentritt, M. Influence of cementation on in vitro performance, marginal adaptation and fracture resistance of CAD/CAM-fabricated ZLS molar crowns. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirel, M.; Donmez, M.B. Fabrication trueness and internal fit of different lithium disilicate ceramics according to post-milling firing and material type. J. Dent. 2024, 144, 104987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falahchai, M.; Babaee Hemmati, Y.; Neshandar Asli, H.; Neshandar Asli, M. Marginal adaptation of zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate overlays with different preparation designs. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2020, 32, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizk, A.; El-Guindy, J.; Abdou, A.; Ashraf, R.; Kusumasari, C.; Eldin, F.E. Marginal adaptation and fracture resistance of virgilite-based occlusal veneers with varying thickness. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrini, F.; Paolone, G.; Di Domenico, G.L.; Pagani, N.; Gherlone, E.F. SEM Evaluation of the Marginal Accuracy of Zirconia, Lithium Disilicate, and Composite Single Crowns Created by CAD/CAM Method: Comparative Analysis of Different Materials. Materials 2023, 16, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höland, W.; Beall, G.H. Glass-Ceramic Technology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vafaee, F.; Heidari, B.; Khoshhal, M.; Hooshyarfard, A.; Izadi, M.; Shahbazi, A.; Moghimbeigi, A. Effect of resin cement color on the final color of lithium disilicate all-ceramic restorations. J. Dent. 2018, 15, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtulmus-Yilmaz, S.; Cengiz, E.; Ongun, S.; Karakaya, I. The effect of surface treatments on the mechanical and optical behaviors of CAD/CAM restorative materials. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, e496–e503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliu, R.-D.; Porojan, S.D.; Bîrdeanu, M.I.; Porojan, L. Effect of Thermocycling, Surface Treatments and Microstructure on the Optical Properties and Roughness of CAD-CAM and Heat-Pressed Glass Ceramics. Materials 2020, 13, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Bona, A.; Nogueira, A.D.; Pecho, O.E. Optical properties of CAD–CAM ceramic systems. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, D.; Stawarczyk, B.; Liebermann, A.; Ilie, N. Translucency of esthetic dental restorative CAD/CAM materials and composite resins with respect to thickness and surface roughness. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 113, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subaşı, M.G.; Alp, G.; Johnston, W.M.; Yilmaz, B. Effect of thickness on optical properties of monolithic CAD-CAM ceramics. J. Dent. 2018, 71, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacchi, A.; Boccardi, S.; Alessandretti, R.; Pereira, G.K.R. Substrate masking ability of bilayer and monolithic ceramics used for complete crowns and the effect of association with an opaque resin-based luting agent. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2019, 63, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunal, B.; Ulusoy, M.M. Optical properties of contemporary monolithic CAD-CAM restorative materials at different thicknesses. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2018, 30, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, J.; Jackson, T.; Cook, R.; Sulaiman, T.A. Optical properties of a novel glass–ceramic restorative material. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 1160–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebermann, A.; Mandl, A.; Eichberger, M.; Stawarczyk, B. Impact of resin composite cement on color of computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing ceramics. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, G.W.; Matinlinna, J.P. Insights on ceramics as dental materials. Part II: Chemical surface treatments. Silicon 2011, 3, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswal, G.; Nair, C. Effects of various parameters of alumina air abrasion on the mechanical properties of low-fusing feldspathic porcelain laminate material. S. Afr. Dent. J. 2015, 70, 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim, R.; Vermudt, A.; Pereira, J.R.; Pamato, S. The surface treatment of dental ceramics: An overview. J. Res. Dent. 2018, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladağ, S.Ü.; Ayaz, E.A. Repair bond strength of different CAD-CAM ceramics after various surface treatments combined with laser irradiation. Lasers Med. Sci. 2023, 38, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altan, B.; Cinar, S.; Tuncelli, B. Evaluation of shear bond strength of zirconia-based monolithic CAD-CAM materials to resin cement after different surface treatments. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2019, 22, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, J.C.M.; Raffaele-Esposito, A.; Carvalho, O.; Silva, F.; Özcan, M.; Henriques, B. Surface modification of zirconia or lithium disilicate-reinforced glass ceramic by laser texturing to increase the adhesion of prosthetic surfaces to resin cements: An integrative review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 3331–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inokoshi, M.; Yoshihara, K.; Kakehata, M.; Yashiro, H.; Nagaoka, N.; Tonprasong, W.; Xu, K.; Minakuchi, S. Preliminary Study on the Optimization of Femtosecond Laser Treatment on the Surface Morphology of Lithium Disilicate Glass-Ceramics and Highly Translucent Zirconia Ceramics. Materials 2022, 15, 3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, G.A.; Sophr, A.M.; De Goes, M.F.; Sobrinho, L.C.; Chan, D.C. Effect of etching and airborne particle abrasion on the microstructure of different dental ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003, 89, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, G.W.; Matinlinna, J.P. Evaluation of the microtensile bond strength between resin composite and hydrofluoric acid etched ceramic in different storage media. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2011, 25, 2671–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, R.; Bebsh, M.; Haimeur, A.; Fernandes, A.C.; Sacher, E. Physicochemical surface characterizations of four dental CAD/CAM lithium disilicate-based glass ceramics on HF etching: An XPS study. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalavacharla, V.K.; Lawson, N.C.; Ramp, L.C.; Burgess, J.O. Influence of Etching Protocol and Silane Treatment with a Universal Adhesive on Lithium Disilicate Bond Strength. Oper. Dent. 2015, 40, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zogheib, L.V.; Bona, A.D.; Kimpara, E.T.; Mccabe, J.F. Effect of hydrofluoric acid etching duration on the roughness and flexural strength of a lithium disilicate-based glass ceramic. Braz. Dent. J. 2011, 22, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshmand, T.; Parvizi, S.; Keshvad, A. Effect of surface acid etching on the biaxial flexural strength of two hot-pressed glass ceramics. J. Prosthodont. 2008, 17, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiaoping, L.; Dongfeng, R.; Silikas, N. Effect of etching time and resin bond on the flexural strength of IPS e. max Press glass ceramic. Dent. Mater. 2014, 30, e330–e336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menees, T.S.; Lawson, N.C.; Beck, P.R.; Burgess, J.O. Influence of particle abrasion or hydrofluoric acid etching on lithium disilicate flexural strength. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarda, G.B.; Correr, A.B.; Gonçalves, L.S.; Costa, A.R.; Borges, G.A.; Sinhoreti, M.A.; Correr-Sobrinho, L. Effects of surface treatments, thermocycling, and cyclic loading on the bond strength of a resin cement bonded to a lithium disilicate glass ceramic. Oper. Dent. 2013, 38, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruo, Y.; Nishigawa, G.; Irie, M.; Yoshihara, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Minagi, S. Does acid etching morphologically and chemically affect lithium disilicate glass ceramic surfaces? J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2017, 15, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundfeld, D.; Correr-Sobrinho, L.; Pini, N.I.P.; Costa, A.R.; Sundfeld, R.H.; Pfeifer, C.S.; Martins, L.R. The effect of hydrofluoric acid concentration and heat on the bonding to lithium disilicate glass ceramic. Braz. Dent. J. 2016, 27, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuzic, C.; Jivanescu, A.; Negru, R.M.; Hulka, I.; Rominu, M. The Influence of Hydrofluoric Acid Temperature and Application Technique on Ceramic Surface Texture and Shear Bond Strength of an Adhesive Cement. Materials 2023, 16, 4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyva Del Rio, D.; Sandoval-Sanchez, E.; Campos-Villegas, N.E.; Azpiazu-Flores, F.X.; Zavala-Alonso, N.V. Influence of Heated Hydrofluoric Acid Surface Treatment on Surface Roughness and Bond Strength to Feldspathic Ceramics and Lithium-Disilicate Glass-Ceramics. J. Adhes. Dent. 2021, 23, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, H.; Hooshmand, T.; Aghajani, F. Effect of Ceramic Surface Treatments after Machine Grinding on the Biaxial Flexural Strength of Different CAD/CAM Dental Ceramics. J. Dent. 2015, 12, 621–629. [Google Scholar]

- Loomans, B.A.; Mine, A.; Roeters, F.J.; Opdam, N.J.; De Munck, J.; Huysmans, M.C.; Van Meerbeek, B. Hydrofluoric acid on dentin should be avoided. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayad, M.F.; Fahmy, N.Z.; Rosenstiel, S.F. Effect of surface treatment on roughness and bond strength of a heat-pressed ceramic. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2008, 99, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajraktarova-Valjakova, E.; Grozdanov, A.; Guguvcevski, L.; Korunoska-Stevkovska, V.; Kapusevska, B.; Gigovski, N.; Mijoska, A.; Bajraktarova-Misevska, C. Acid etching as surface treatment method for luting of glass-ceramic restorations, part 1: Acids, application protocol and etching effectiveness. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, G.C.; Perdigão, J.; Baptista, D.; Ballarin, A. Does a Self-etching Ceramic Primer Improve Bonding to Lithium Disilicate Ceramics? Bond Strengths and FESEM Analyses. Oper. Dent. 2019, 44, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tribst, J.P.; Diamantino, P.J.; de Freitas, M.R.; Tanaka, I.V.; Silva-Concílio, L.R.; de Melo, R.M. Effect of active application of self-etching ceramic primer on the long-term bond strength of different dental CAD/CAM materials. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2021, 13, e1089–e1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tribst, J.; Anami, L.C.; Özcan, M.; Bottino, M.A.; Melo, R.M.; Saavedra, G. Self-etching Primers vs Acid Conditioning: Impact on Bond Strength Between Ceramics and Resin Cement. Oper. Dent. 2018, 43, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, R.; da Silva, N.R.; de Miranda, L.M.; de Araújo, G.M.; Moura, D.; Barbosa, H. Two-year Follow-up of Ceramic Veneers and a Full Crown Treated With Self-etching Ceramic Primer: A Case Report. Oper. Dent. 2020, 45, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schestatsky, R.; Zucuni, C.P.; Venturini, A.B.; de Lima Burgo, T.A.; Bacchi, A.; Valandro, L.F.; Pereira, G.K.R. CAD-CAM milled versus pressed lithium-disilicate monolithic crowns adhesively cemented after distinct surface treatments: Fatigue performance and ceramic surface characteristics. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 94, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriamporn, T.; Kraisintu, P.; See, L.P.; Swasdison, S.; Klaisiri, A.; Thamrongananskul, N. Effect of Different Neutralizing Agents on Feldspathic Porcelain Etched by Hydrofluoric Acid. Eur. J. Dent. 2019, 13, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Panah, F.G.; Rezai, S.M.; Ahmadian, L. The influence of ceramic surface treatments on the micro-shear bond strength of composite resin to IPS Empress 2. J. Prosthodont. 2008, 17, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, L.; You, C.; Ye, C.; Jiang, R.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Han, C. A review of treatment strategies for hydrofluoric acid burns: Current status and future prospects. Burns 2014, 40, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özcan, M.; Volpato, C. Surface conditioning protocol for the adhesion of resin-based materials to glassy matrix ceramics: How to condition and why. J. Adhes. Dent. 2015, 17, 292–293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saavedra, G.; Ariki, E.K.; Federico, C.D.; Galhano, G.; Zamboni, S.; Baldissara, P.; Bottino, M.A.; Valandro, L.F. Effect of acid neutralization and mechanical cycling on the microtensile bond strength of glass-ceramic inlays. Oper. Dent. 2009, 34, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottino, M.; Snellaert, A.; Bergoli, C.; Özcan, M.; Bottino, M.; Valandro, L. Effect of ceramic etching protocols on resin bond strength to a feldspar ceramic. Oper. Dent. 2015, 40, E40–E46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ramakrishnaiah, R.; Alkheraif, A.A.; Divakar, D.D.; Alghamdi, K.F.; Matinlinna, J.P.; Lung, C.Y.K.; Cherian, S.; Vallittu, P.K. The effect of lithium disilicate ceramic surface neutralization on wettability of silane coupling agents and adhesive resin cements. Silicon 2018, 10, 2391–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiry, M.A.; AlShahrani, I.; Alaqeel, S.M.; Durgesh, B.H.; Ramakrishnaiah, R. Effect of two-step and one-step surface conditioning of glass ceramic on adhesion strength of orthodontic bracket and effect of thermo-cycling on adhesion strength. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 84, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.d.P.; Cotes, C.; Yamamoto, L.T.; Rossi, N.R.; da Cruz Macedo, V.; Kimpara, E.T. Flexural strength of a pressable lithium disilicate ceramic: Influence of surface treatments. Appl. Adhes. Sci. 2013, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Benetti, A.R.; Papia, E.; Matinlinna, J.P. Bonding ceramic restorations. Nor. Tann. Tid. 2019, 129, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.-H.; Han, G.-J.; Oh, K.-H.; Chung, S.-N.; Chun, B.-H. The effect of plasma polymer coating using atmospheric-pressure glow discharge on the shear bond strength of composite resin to ceramic. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 2755–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Okawa, T.; Fukumoto, T.; Tsurumi, A.; Tatsuta, M.; Fujii, T.; Tanaka, J.; Tanaka, M. Influence of atmospheric pressure low-temperature plasma treatment on the shear bond strength between zirconia and resin cement. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2016, 60, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birk, L.; Rener-Sitar, K.; Benčina, M.; Junkar, I. Dental silicate ceramics surface modification by nonthermal plasma: A systematic review. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itthipongsatorn, N.; Srisawasdi, S. Dentin microshear bond strength of various resin luting agents to zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 124, 237.e1–237.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Hui, R.; Gao, L.; Ma, Y.; Wu, X.; Meng, Y.; Hao, Z. Effect of surface treatments on bond durability of zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate ceramics: An in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 1350.e1–1350.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalla-Nora, F.; Guilardi, L.F.; Zucuni, C.P.; Valandro, L.F.; Rippe, M.P. Fatigue Behavior of Monolithic Zirconia-Reinforced Lithium Silicate Ceramic Restorations: Effects of Conditionings of the Intaglio Surface and the Resin Cements. Oper. Dent. 2021, 46, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Thagafi, R.; Al-Zordk, W.; Saker, S. Influence of Surface Conditioning Protocols on Reparability of CAD/CAM Zirconia-reinforced Lithium Silicate Ceramic. J. Adhes. Dent. 2016, 18, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Madina, M.M.; Ozcan, M.; Badawi, M.F. Effect of surface conditioning and taper angle on the retention of IPS e.max Press crowns. J. Prosthodont. 2010, 19, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaoka, N.; Yoshihara, K.; Tamada, Y.; Yoshida, Y.; Meerbeek, B.V. Ultrastructure and bonding properties of tribochemical silica-coated zirconia. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.; Billington, R.; Pearson, G. The in vivo perception of roughness of restorations. Br. Dent. J. 2004, 196, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, C.M.; Papaioanno, W.; Van Eldere, J.; Schepers, E.; Quirynen, M.; Van Steenberghe, D. The influence of abutment surface roughness on plaque accumulation and peri-implant mucositis. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 1996, 7, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksoy, G.; Polat, H.; Polat, M.; Coskun, G. Effect of various treatment and glazing (coating) techniques on the roughness and wettability of ceramic dental restorative surfaces. Colloids Surf. B 2006, 53, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, M.; Bankoğlu Güngör, M.; Karakoca Nemli, S.; Turhan Bal, B. Effects of glazing methods on the optical and surface properties of silicate ceramics. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2020, 64, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumchai, H.; Juntavee, P.; Sun, A.F.; Nathanson, D. Effect of glazing on flexural strength of full-contour zirconia. Int. J. Dent. 2018, 2018, 8793481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anusavice, K.J. Standardizing failure, success, and survival decisions in clinical studies of ceramic and metal-ceramic fixed dental prostheses. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malament, K.A.; Natto, Z.S.; Thompson, V.; Rekow, D.; Eckert, S.; Weber, H.-P. Ten-year survival of pressed, acid-etched e. max lithium disilicate monolithic and bilayered complete-coverage restorations: Performance and outcomes as a function of tooth position and age. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sailer, I.; Karasan, D.; Todorovic, A.; Ligoutsikou, M.; Pjetursson, B.E. Prosthetic failures in dental implant therapy. Periodontol. 2000 2022, 88, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, M.; Sasse, M.; Wolfart, S. Ten-year outcome of three-unit fixed dental prostheses made from monolithic lithium disilicate ceramic. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2012, 143, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garling, A.; Sasse, M.; Becker, M.E.E.; Kern, M. Fifteen-year outcome of three-unit fixed dental prostheses made from monolithic lithium disilicate ceramic. J. Dent. 2019, 89, 103178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfart, S.; Eschbach, S.; Scherrer, S.; Kern, M. Clinical outcome of three-unit lithium-disilicate glass-ceramic fixed dental prostheses: Up to 8 years results. Dent. Mater. 2009, 25, e63–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Breemer, C.R.; Vinkenborg, C.; van Pelt, H.; Edelhoff, D.; Cune, M.S. The Clinical Performance of Monolithic Lithium Disilicate Posterior Restorations after 5, 10, and 15 Years: A Retrospective Case Series. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 30, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotiadou, C.; Manhart, J.; Diegritz, C.; Folwaczny, M.; Hickel, R.; Frasheri, I. Longevity of lithium disilicate indirect restorations in posterior teeth prepared by undergraduate students: A retrospective study up to 8.5 years. J. Dent. 2021, 105, 103569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, G. Zirconia: Most durable tooth-colored crown material in practice-based clinical study. Clin. Rep. 2018, 11, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, M.; Koller, C.; Mehl, A.; Hickel, R. Indirect zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate ceramic CAD/CAM restorations: Preliminary clinical results after 12 months. Quintessence Int. 2017, 48, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rinke, S.; Pfitzenreuter, T.; Leha, A.; Roediger, M.; Ziebolz, D. Clinical evaluation of chairside-fabricated partial crowns composed of zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate ceramics: 3-year results of a prospective practice-based study. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2020, 32, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinke, S.; Zuck, T.; Hausdörfer, T.; Leha, A.; Wassmann, T.; Ziebolz, D. Prospective clinical evaluation of chairside-fabricated zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate ceramic partial crowns—5-year results. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, M.; Cagidiaco, E.F.; Goracci, C.; Sorrentino, R.; Zarone, F.; Grandini, S.; Joda, T. Posterior partial crowns out of lithium disilicate (LS2) with or without posts: A randomized controlled prospective clinical trial with a 3-year follow up. J. Dent. 2019, 83, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degidi, M.; Nardi, D.; Sighinolfi, G.; Piattelli, A. Fixed Partial Restorations Made of a New Zirconia-Reinforced Lithium Silicate Material: A 2-Year Short-Term Report. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 34, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölken, F.; Dietrich, H. Restoring Teeth with an Advanced Lithium Disilicate Ceramic: A Case Report and 1-Year Follow-Up. Case Rep. Dent. 2022, 2022, 6872542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bompolaki, D.; Punj, A.; Fellows, C.; Truong, C.; Ferracane, J.L. Clinical Performance of CAD/CAM Monolithic Lithium Disilicate Implant-Supported Single Crowns Using Solid or Predrilled Blocks in a Fully Digital Workflow: A Retrospective Cohort Study With Up To 33 Months of Follow Up. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 31, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BS EN ISO 6872:2015+A1:2018; Dentistry—Ceramic Materials. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

| Ceramic Type | Product Name, Manufacturer (Launch Date) | Chemical Composition (wt%) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Clinical Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium- disilicate (Li2Si2O5) | IPS e.max® Press, Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein (2005) | SiO2 (57.0–80.0), Li2O (11.0–19.0), K2O (<13.0), P2O5 (<11.0) ZrO2 (<8.0), ZnO (<8.0), colouring oxides (<12.0) | 470 | Inlays, onlays, veneers, crowns, 3-unit FPDs up to 2nd premolar, implant-supported crowns |

| InitialTM LiSi Press, GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan (2016) | SiO2 (71.0), Li2O (13.0), Al2O3 (5.4), Na2O (1.4), K2O (2.0), P2O5 (2.6), ZrO2 (1.7), B2O3 (0.007), CeO2 (1.2), V2O5 (0.15), Tb2O3 (0.35), Er2O4 (0.4), HfO2 (0.03) | 508 | Inlays, onlays, veneers, anterior and posterior crowns, implant crowns, 3-unit FPDs on teeth or implants up to 2nd premolar | |

| Amber® Press, HASS Corp., Gangwon State, Korea (2020) | SiO2 (<78), Li2O (<12), colouring oxides (<12) | 460 | Inlays, onlays, veneers, anterior and posterior crowns, 3-unit FPDs on teeth up to 2nd premolar | |

| Livento Press, Cendres + Métaux, Biel/Bienne, Switzerland (2019) | SiO2 (65–80), Al2O3 (<11), Li2O (11–19), K2O (<7), Na2O (<5), CaO (<10), P2O5 (1.5–7), ZnO (<7), others (<15) | 300 | Inlays and onlays, veneers, partial crowns, anterior and posterior crowns, hybrid abutment crowns, 3-unit anterior and posterior bridges up to 2nd premolar | |

| Zirconia reinforced lithium silicates (Li2SiO3/Li2Si2O5) | Celtra® Press, Dentsply Sirona, Salzburg, Austria (2017) | SiO2 (58), Li2O (18.5), ZrO2 (10.1), P2O5 (5), Al2O3 (1.9), CeO2 (2), Tb4O7 (1) | >500 | Inlays, onlays, veneers, anterior and posterior crowns, 3 unit anterior bridges |

| VITA AMBRIA®, VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany (2021) | SiO2 (58–66), Li2O (12–16), Al2O3 (1–4), K2O (1–4), P2O5 (2–6), ZrO2 (8–12), B2O3 (1–4), CeO2 (<4), V2O5 (<1) Tb2O3 (1–4), Er2O4 (<1), Pr6O11 (<1) | 400 | Inlays, onlays, veneers, anterior and posterior crowns, implant crowns, 3-unit FPDs on teeth or implants up to 2nd premolar |

| Ceramic Type | Product Name, Manufacturer (Launch Date) | Chemical Composition (wt.%) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Processing | Clinical Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium- disilicate (Li2Si2O5) | IPS e.max® CAD, Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein (2006) | SiO2 (57.0–80.0), Li2O (11.0–19.0), K2O (<13), P2O5 (<11), ZrO2 (<8.0), ZnO (<8.0), Al2O3 (<5.0), MgO (<5.0), pigments (<0.8) | 360 ± 40 | Two-step | Inlays, onlays, veneers, anterior and posterior crowns, 3-unit FPDs up to 2nd premolar, implant supported crowns |

| Rosetta SM, HASS Corp., Gangwon State, Korea (2013) | SiO2 (<78), Li2O (<120, colouring oxides (<12) | 400 | Two-step | Inlays, onlays, veneers, anterior and posterior crowns, 3-unit anterior FPDs | |

| Amber® Mill, HASS Corp., Gangwon State, Korea (2018) | SiO2 (<78), Li2O (<12), colouring oxides (<12) | 450 | Two-step | Inlays, onlays, veneers, anterior and posterior crowns, 3-unit FPDs (up to 2nd premolar) | |

| InitialTM LiSi Blocks, GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan (2021) | SiO2 (81), P2O5 (8.1), K2O (5.9), Al2O3 (3.8), TiO2 (0.5), CeO2 (0.6) | 408 | One-step | Inlays, onlays, veneers, anterior and posterior crowns, implant-supported crowns | |

| Lithium-metasilicate (Li2SiO3) | Obsidian®, Glidewell Laboratories, CA, USA (2013) | SiO2 (50–58), Li2O (10–20), GeO2 (1–10), K2O (2–6), P2O5 (2–4), Al2O3 (2–4), ZrO2 (2–4), others (<10) | 385 | Two-step | Inlays, onlays, veneers, anterior and posterior crowns |

| Zirconia reinforced lithium silicates (Li2SiO3/Li2Si2O5) | Celtra® Duo, Dentsply Sirona, Salzburg, Austria (2013) | SiO2 (58), Li2O (18.5), ZrO2 (10.1), P2O5 (5), Al2O3(1.9), CeO2 (2), Tb4O7 (1) | 370 | One-step | Inlays, onlays, veneers, partial crowns, anterior and posterior crowns, implant-supported crowns |

| VITA Suprinity® VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany (2013) | SiO2 (56–64), Li2O (15–21), ZrO2 (8–12), P2O5 (3–8), Al2O3 (1–4), K2O (1–4), CeO2 (<4), La2O3 (0.1), pigments (<6) | 420 | Two-step | Inlays, onlays, veneers, partial crowns, anterior and posterior crowns, implant-supported crowns | |

| Lithium aluminium disilicate (LiAlSi2O6/Li2Si2O5) | n!ce®, Straumann, Basel, Switzerland (2017) | SiO2 (64–70), Li2O (10.5–12.5), Al2O3 (10.5–11.5), Na2O (1–3), K2O (0–3), P2O5 (3–8), ZrO2 (<0.5), CaO (1–2), colouring oxides (<9) | 350 ± 50 | One-step | Inlays, onlays, veneers, anterior and posterior crowns, implant-supported crowns |

| CEREC TesseraTM, Dentsply Sirona, Salzburg, Austria (2021) | Li2Si2O5 (90), Li3PO4 (5), Li0.5Al0.5Si2.5O6 (5) | 700 | Two-step | Inlays, onlays, veneers, anterior and posterior crowns |

| Database | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Pubmed/ Medline | “Lithium silicate-based glass-ceramics” OR “Lithium disilicate” OR “Zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate” OR “Lithium aluminum disilicate” OR “Advanced lithium disilicate” OR “Glass-ceramics” OR “Dental ceramics” OR “dental materials” [Mesh] OR “dentistry” [Mesh] OR “CAD/CAM” [Mesh] OR “machinable lithium silicate” OR “pressable lithium silicate” OR “heat pressed lithium silicate” |

| Scopus | “Lithium AND silicate-based AND dental AND ceramics” OR “Zirconia-reinforced AND lithium AND silicate” OR “Advanced AND lithium AND disilicate” OR “Reinforced AND lithium AND silicate” OR “CAD/CAM AND lithium AND silicate” OR “Heat AND pressed AND lithium AND silicate” |

| Google Scholar | “Lithium silicate-based glass-ceramics” OR “Lithium disilicate” OR “Zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate” OR “Lithium aluminum disilicate” OR “Advanced lithium disilicate” OR “Glass-ceramics” OR “CAD/CAM lithium silicates” OR “machinable lithium silicate” OR “pressable lithium silicate” OR “heat pressed lithium silicate” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Johani, H.; Haider, J.; Satterthwaite, J.; Silikas, N. Lithium Silicate-Based Glass Ceramics in Dentistry: A Narrative Review. Prosthesis 2024, 6, 478-505. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis6030034

Al-Johani H, Haider J, Satterthwaite J, Silikas N. Lithium Silicate-Based Glass Ceramics in Dentistry: A Narrative Review. Prosthesis. 2024; 6(3):478-505. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis6030034

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Johani, Hanan, Julfikar Haider, Julian Satterthwaite, and Nick Silikas. 2024. "Lithium Silicate-Based Glass Ceramics in Dentistry: A Narrative Review" Prosthesis 6, no. 3: 478-505. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis6030034

APA StyleAl-Johani, H., Haider, J., Satterthwaite, J., & Silikas, N. (2024). Lithium Silicate-Based Glass Ceramics in Dentistry: A Narrative Review. Prosthesis, 6(3), 478-505. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis6030034