Quaternionic and Octonionic Frameworks for Quantum Computation: Mathematical Structures, Models, and Fundamental Limitations

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Review and unification of quaternionic frameworks. We collect and streamline existing results on quaternionic quantum mechanics and computation, including the circuit model of Fernández and Schneeberger [6], the simulation of quaternionic dynamics and channels on complex Hilbert spaces [7,8], and classical treatments of quaternionic quantum theory [3,4]. We recast these in a right--module language aligned with the modern quantum-information toolkit (states, channels, POVMs, and tensor products).

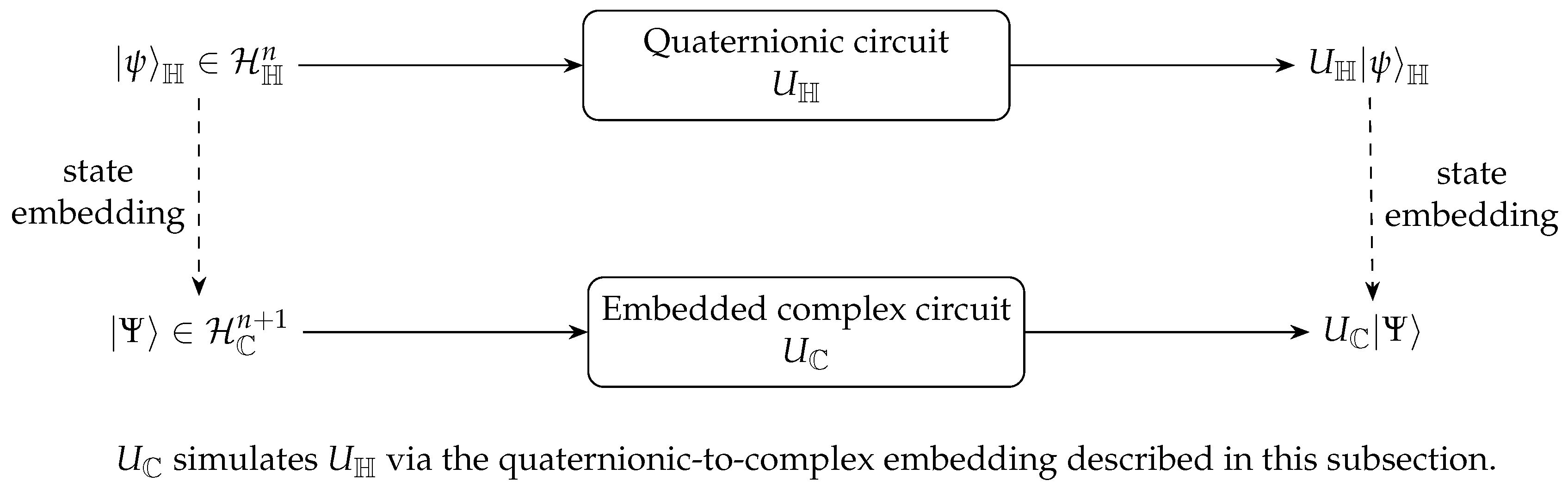

- Original: encoded -based model of quantum computation. Building on this background, we formulate a complete -based circuit model with well-defined quaternionic qubit registers, gates, measurements, and tensor products, together with an explicit embedding into standard complex qubit circuits via the map . Our construction yields a polynomial-time, ancilla-efficient simulation of any quaternionic process by complex circuits, extending the circuit-level result of [6] to general channels and measurement patterns and making the computational equivalence with BQP fully explicit (see Theorem 2 and Proposition 7).

- Review of octonionic proposals. We summarize relevant prior work on octonions in physics and quantum information, in particular the measurement-only scheme for universal quantum computation based on octonionic equiangular projections [9] and earlier studies of octonionic structures in quantum theory [2].

- Original: systematic obstruction and mitigation analysis for -based models. We show that promoting to a gate-based computational model faces three structural obstructions (loss of associative tensor products, path-dependent dynamics, and nonlocal measurement postulates), and we organize possible workarounds into four concrete strategies (M1)–(M4): associative confinement, -invariant coding, associator-suppressing dynamical decoupling, and seven-factor synthesis. We analyse their resource overheads and limits in terms of qubit counts, control complexity, and fault-tolerance, clarifying in what sense octonionic frameworks can be realised only as encoded or effective complex-qubit models.

1.1. Extended Related Work

1.2. Introduction: Bridging Theory and Experiment—Additional Details

From Abstract Algebras to Physical Systems

- The Challenge of Scale and Coherence: Can we build, initialize, and maintain the coherence of the complex, multi-qubit entangled states required to represent even a single octo-qubit?

- The Challenge of Control and Fidelity: Can we implement the sophisticated, multi-gate sequences required for the mitigation strategies (e.g., -symmetric codes or dynamical decoupling) with a fidelity high enough to overcome the intrinsic associator errors?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Standard Quantum Computation over

2.2. Normed Division Algebras

2.3. Quaternionic and Octonionic Preliminaries

- (right linearity);

- (quaternionic Hermiticity);

- and vanishes iff (positivity).

- Adjoint/inner product ambiguity: Without associativity, the defining relation becomes parenthesization-dependent unless dynamics and observables are confined to associative subalgebras.

- Non-associative tensor products: For right -modules , the identification is not canonical in general; different parenthesizations yield inequivalent scalar actions. Thus, there is no canonical multipartite structure unless one restricts to an associative (quaternionic) sector.

- Path dependence in evolution: For , the propagator acquires higher-order terms involving associators in Magnus-like expansions. Reordering control slices can change even for the same time-averaged H, leading to intrinsic path dependence outside associative sectors.

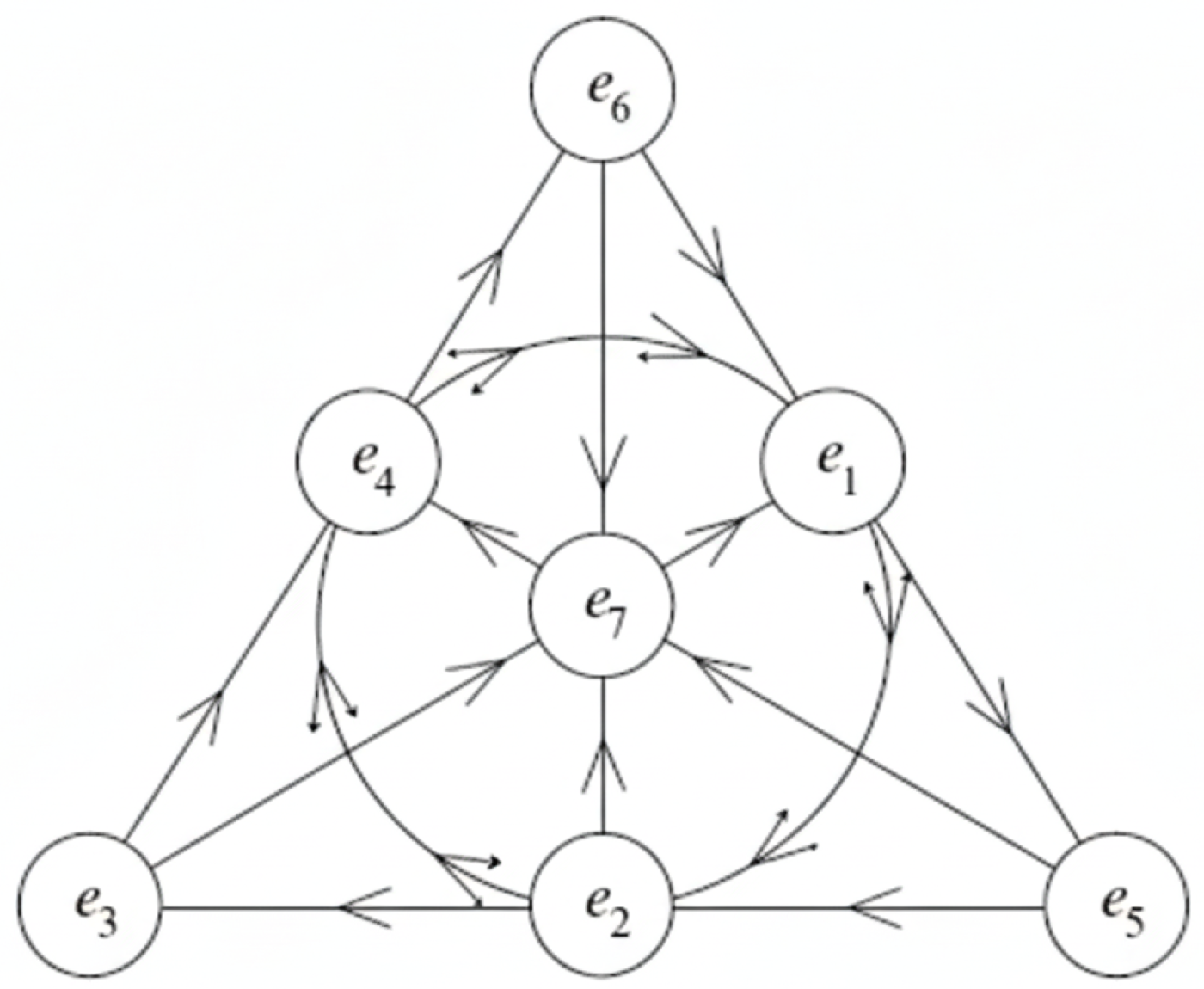

2.4. Structure of Octonions and the Fano Plane

2.5. Geometric and Group-Theoretic Side Notes

2.6. Quaternionic Formalism

- Single-quaternionic qubit layer: identifies unit quaternions with native rotations on the encoded pair, so calibrated single-qubit pulses implement quaternionic rotations exactly (Lemma 1).

- Two-quaternionic qubit entanglers: Any standard entangling gate (e.g., CNOT/CZ) on the encoded pairs realizes an entangler over ; universality follows from a dense single-quaternionic qubit set plus one fixed entangler (Proposition 1).

2.7. Octonionic Formalism

2.8. Hybrid Architectures and Embeddings—Additional Details

2.8.1. The Quaternionic-to-Complex Embedding Protocol in Practice

Mapping Quaternionic States to Complex Qubit States

Circuit Diagrams and Practical Implications

- Resource Overhead: Each logical quaternionic qubit requires two physical complex qubits. An algorithm operating on N quaternionic qubits would thus require complex qubits (or for the optimized ancilla method [6]). This linear overhead makes simulation feasible for moderate N.

- Gate Depth and Fidelity: Each quaternionic gate translates to a fixed number of standard complex gates. While this increases the overall circuit depth, it’s a constant factor overhead per logical gate, meaning total error accumulation remains manageable within fault-tolerance thresholds for complex systems.

- Hardware Compatibility: This protocol makes quaternionic quantum computing immediately compatible with any existing universal quantum computing platform (superconducting, trapped-ion, photonic, etc.), as it merely requires standard gate sets.

- Algorithm Development: Researchers can develop and test quaternionic quantum algorithms using existing quantum simulators and hardware, leveraging the richer algebraic structure for potential optimization or physical simulation, even if the underlying hardware is complex-valued.

2.8.2. Simulating Octonionic Dynamics via Associative Decomposition

The Simulation Protocol

2.9. Mitigation Palette: Constructions and Workflows

2.10. Cayley–Dickson Product

2.11. Associative Subalgebras and Confinement

3. Results

3.1. Quaternionic Model: Structural, Universality, and Simulation Results

3.2. Octonionic Model: Formal Obstructions and Limits

3.3. Mitigation Strategies: Correctness Guarantees and Quantitative Effects

3.4. Complexity Landscape and Feasibility

3.5. Computational Equivalence and Circuit Simplification—Elaboration

3.5.1. Theoretical Equivalence to Complex Quantum Circuits

Mapping Quaternionic States to Complex States

Mapping Quaternionic Gates to Complex Gates

3.5.2. Resource Analysis and the Potential for Circuit Simplification

Compact Representation of Rotations

- Reduced Circuit Depth: A single, more complex gate replaces a sequence of three simpler ones, reducing the overall time required for the computation.

- Lower Error Rates: Each additional gate in a circuit introduces a small amount of error. By concatenating fewer gates, the total accumulated error is reduced, leading to higher-fidelity computations.

- Simplified Quantum Control: Designing optimal control pulses to implement a single quaternionic rotation may be a simpler problem than designing and calibrating three separate, sequential pulses, potentially leading to more robust gate implementations.

Applications in Quantum Simulation and VQE

3.6. Emerging Applications and Future Directions—Elaboration

3.6.1. Quantum Simulation with Algebraic Symmetries ( and )

Symmetries in Quaternionic Quantum Simulation

- Spin Systems and Magnetic Materials: Hamiltonians describing interacting spins (e.g., Heisenberg models, spin-liquid candidates) inherently possess symmetry. Representing spin states and their dynamics directly with quaternionic amplitudes and gates might offer a more natural and compact formalism than their complex counterparts. The rotation group SO(3), which is homomorphic to , is directly representable by unit quaternions, making quaternionic gates ideal for simulating geometric phases and Berry connections in these systems [75].

- Molecular Dynamics and Rotations: Simulating the rotational dynamics of molecules, especially in complex environments, can benefit from a representation that natively handles 3D rotations. Quaternions provide a singularity-free and computationally efficient way to parameterize rotations, potentially simplifying the ansatz design for variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) aimed at molecular ground states or dynamics [76].

- Gauge Theories: Certain lattice gauge theories, particularly those related to quantum chromodynamics (QCD) or models of interacting fermions, involve gauge fields. Quaternionic formalisms could provide a more direct mapping of these fundamental symmetries onto quantum circuits, potentially leading to more efficient Hamiltonian simulation strategies.

Symmetries in Octonionic Quantum Simulation

- Simulating Exceptional Symmetries: The group is a fundamental mathematical structure that appears in various advanced physical theories, including certain grand unified theories (GUTs), supergravity, and string theory [2,10]. A quantum simulator capable of exploiting symmetry could provide unique insights into these theories, even if the general-purpose octonionic computation is limited. For instance, simulating particle interactions or field theories that possess as a fundamental symmetry could be more natural within an octonionic framework that natively represents this group.

- Protected Octonionic Dynamics: As discussed in Chapter 5 [5], -symmetric codes or confinement to -invariant subspaces could be used to protect quantum information from associator errors [77]. While this limits universality, it enables controlled, high-fidelity operations within these protected sectors. Such controlled octonionic dynamics could be used to simulate specific physical phenomena that inherently operate within such constrained algebraic environments, offering a unique “algebraic-topological” form of protection against certain error models.

- Quantum Gravity Analogues: Some speculative theories of quantum gravity or pre-geometric models involve non-associative algebras. An octonionic quantum simulator, even a limited one, could serve as a valuable tool for exploring these theoretical constructs, allowing for the computational study of scenarios where spacetime might acquire an emergent non-associative structure [2].

Connections to Topological Quantum Computation

3.6.2. Hypercomplex Quantum Machine Learning

Quaternionic Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs)

- Compact Data Encoding: Quaternions can encode more information per parameter compared to real or complex numbers. For example, a single quaternion can naturally represent a 3D vector and an orientation, potentially reducing the number of logical qubits or qudits required to encode certain features.

- Exploiting Rotational Symmetries: For datasets with inherent rotational symmetries (e.g., medical images, robotics data, physical simulations), QQNNs could natively incorporate these symmetries, leading to more efficient learning and better generalization, similar to how convolutional neural networks exploit translational symmetries.

- Reduced Parameter Space: By using quaternionic weights and biases, the total number of trainable parameters in a quantum neural network could be significantly reduced, potentially alleviating issues like barren plateaus in VQAs.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Over , quantum computation is mathematically sound, universal, and polynomially equivalent to the complex model, with viable high-fidelity realizations.

- Over , structural barriers from non-associativity necessitate confinement to associative sectors, symmetry protection or decoupling, with nontrivial overheads.

- Future directions include scaling associative-confinement architectures, refining -invariant codes, advancing algebra-aware compilers, and exploring hypercomplex encodings in simulation and learning [5].

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Quaternion-to-Complex Embedding and Proof Details

Appendix A.1. Explicit Embedding

Appendix A.2. Complexity Overhead—Proof-LEVEL Details

Appendix A.3. Synthesis of Contributions and Answers to Research Questions—Additional Details

- Mathematical Consistency: We rigorously defined quaternionic qubits within a two-dimensional right module over , complete with a well-behaved quaternionic-valued inner product and a normalization condition. The geometric representation of a single quaternionic qubit on a Bloch hypersphere () was introduced, demonstrating a richer parameter space compared to the complex Bloch sphere ().

- Universal Gate Set: We showed that single-qubit gates are represented by unitary quaternionic matrices, forming a group isomorphic to , thus allowing all standard single-qubit operations. The construction of multi-qubit systems via the associative tensor product in was formalized, enabling the definition of entangling gates like CNOT and CZ, and preserving the possibility of entanglement.

- Computational Equivalence: A central finding is that quaternionic quantum computing, despite its richer algebraic structure, does not offer greater computational power than the conventional complex model. As proven by seminal works, any computation on n quaternionic qubits can be efficiently simulated by a standard complex quantum circuit on qubits with only polynomial overhead, thereby retaining the same complexity class, BQP [6,7]. This answers our research question regarding the applicability of quaternionic algebra in creating universal logical gates, confirming full applicability without hyper-computational advantage.

- Practical Advantages: While not computationally superior, the quaternionic formalism provides a more intuitive and compact language for describing rotations and symmetries, which is advantageous for quantum simulation of physical systems (e.g., magnetic materials, molecular rotations) and for variational quantum algorithms (VQAs). This representational efficiency can lead to reduced circuit depth and potentially lower error rates in specific applications, as a single quaternionic rotation can replace multiple complex Euler rotations [71].

- Breakdown of Foundations: We demonstrated that an unconstrained octonionic quantum system suffers from an ill-defined Hamiltonian due to ambiguous operator ordering, leading to emergent non-local interaction terms (associators). Consequently, energy conservation is violated unless dynamics are confined to associative subspaces. Time evolution becomes path-dependent, as the standard Dyson series is ill-defined, and the composition of gates is ambiguous, fundamentally undermining the universality of the standard circuit model. The eigenvalue problem for octonionic Hermitian operators does not guarantee real eigenvalues, breaking the bedrock of physical measurement [11,20].

- Mitigation Strategies: To overcome these limitations, we developed and analyzed several algebraic mitigation strategies:

- Restriction to Associative Subalgebras: Confining all operations and state amplitudes to a single quaternionic subalgebra (e.g., ) ensures consistency by eliminating associator errors. However, this comes at the cost of discarding half of the octonionic algebraic degrees of freedom and introducing “context-switching” overhead via complex transformations to access different subspaces. This effectively reduces the system to an inefficient quaternionic computer.

- -Symmetric Codes: We proposed conceptual -symmetric quantum error-correcting codes, leveraging the automorphism group of the octonions. In this model, non-associative errors manifest as detectable symmetry violations (associator syndromes), drawing parallels with topological quantum computation [77,81]. While theoretically powerful, this approach incurs high resource overhead for practical implementation.

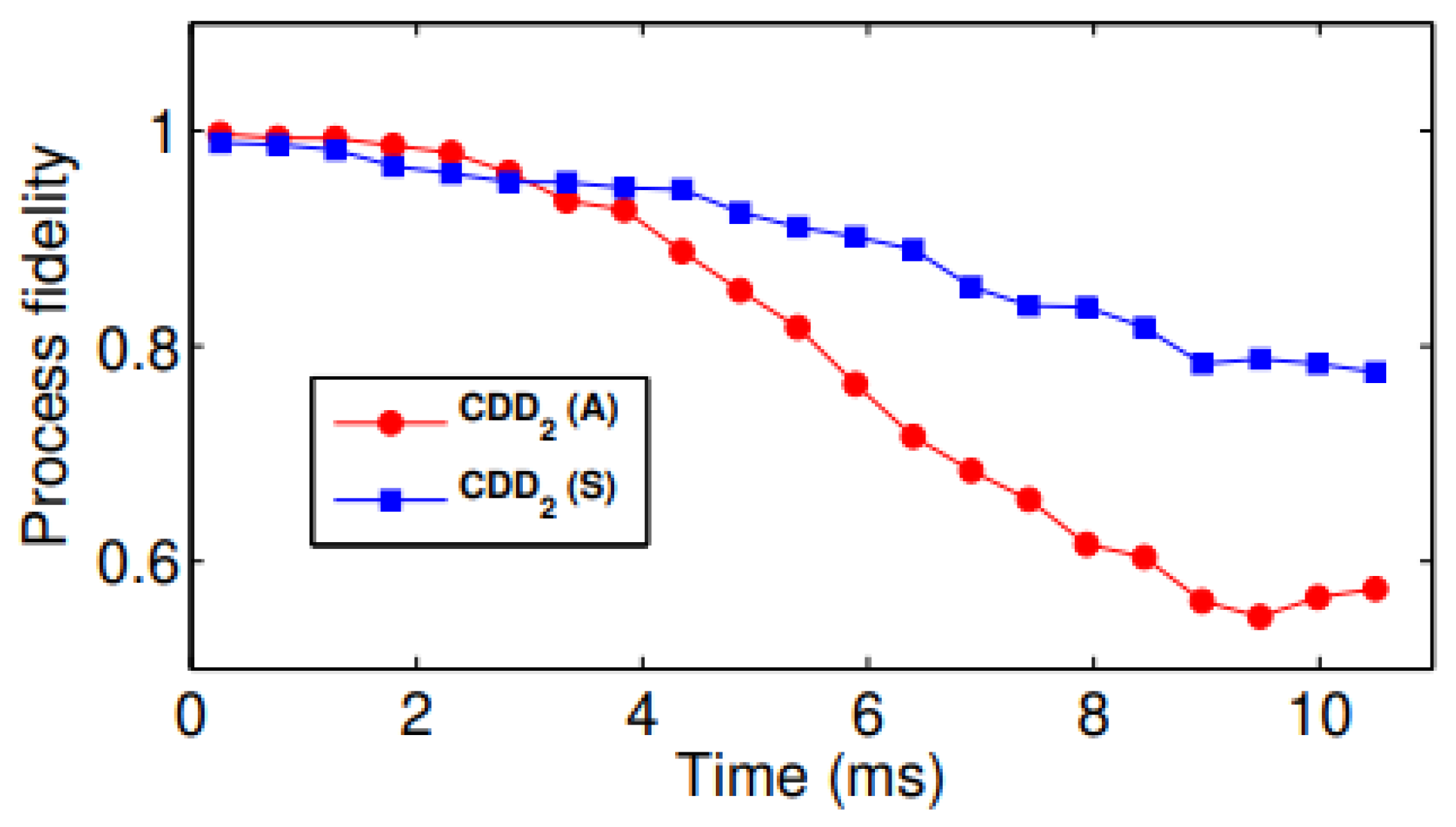

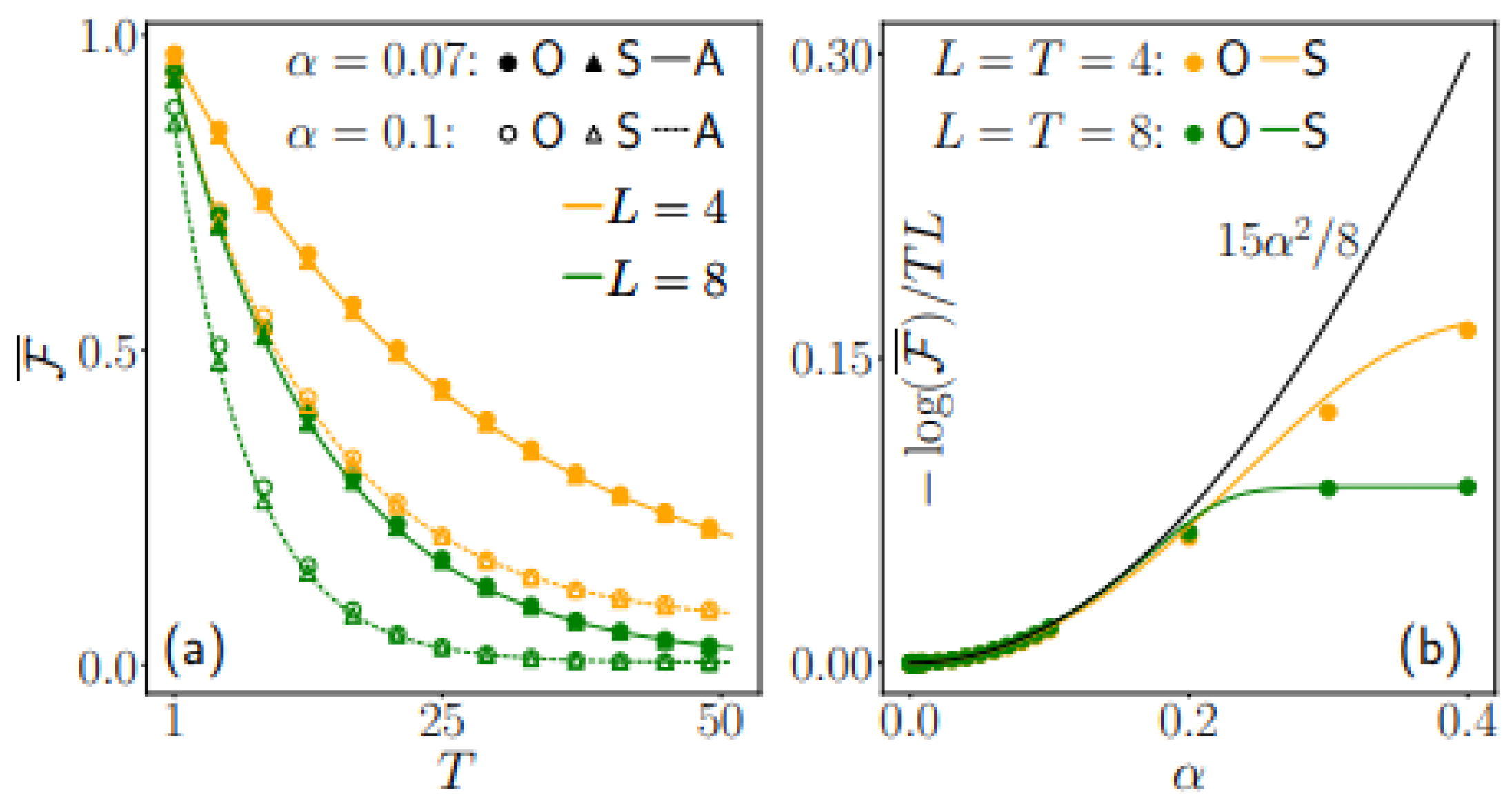

- Dynamical Decoupling: We showed that associator errors can be treated as a coherent noise source and actively suppressed using dynamical decoupling sequences (e.g., quaternionic XY-4 pulses) [18,80]. Numerical simulations demonstrated a dramatic suppression of fidelity decay, suggesting this is a viable experimental method for extending coherence in octonionic systems.

- Algebraic Gate Synthesis: We developed a universal constructive method to implement arbitrary octonionic gates by decomposing them into sequences of simpler, associative rotations around the seven imaginary octonion units [66]. This provides theoretical universality but introduces a significant gate overhead (at least 7 primitive gates per logical operation) and rapid fidelity degradation due to compounded errors, making high-fidelity quantum computation largely unfeasible with current technology.

- Computational Complexity Penalties: The extensive resource analysis confirmed substantial overheads for octonionic computation. A single octo-qubit requires embedding into at least three complex physical qubits [82], leading to an exponential state-space overhead ( vs. ). The gate overhead for managing non-associativity (polynomial ) further suggests that BQOP is likely a strictly less powerful class than BQP (), implying no hyper-computational advantage [2,9].

- Quaternions are within reach: Implementing quaternionic gates and simulating quaternionic dynamics is directly compatible with existing quantum hardware platforms (superconducting qubits, trapped ions, photonics, NV centers) through appropriate embeddings and pulse shaping techniques [19,63,83,84]. The challenge lies in optimizing control and demonstrating potential practical advantages (e.g., circuit simplification for -symmetric simulations).

- Octonions require sophisticated strategies: A “true” octonionic quantum computer remains highly speculative. Practical investigation relies on embedding octonionic logical units into larger complex qubit registers and implementing complex mitigation strategies (like dynamical decoupling or -symmetric codes) to combat intrinsic non-associativity. Trapped-ion and superconducting platforms appear most promising for such complex experimental demonstrations due to their high coherence and control capabilities.

- Hybrid models are a pragmatic path: The most viable path forward for octonions involves hybrid architectures where stable quaternionic computation forms the core, supplemented by specialized octonionic subroutines only where their unique (albeit constrained) symmetries might offer an advantage.

- Interferometric subcircuits probing quaternionic phases. Peres’ classic proposal for distinguishing complex from quaternionic quantum theory via three-path interference [85] and its modern single-photon Sagnac implementations with metamaterials [86] already realize small quantum circuits whose output statistics are sensitive to non-commuting quaternionic phases. In our framework, these setups implement specific one-quaternionic qubit phase-gate patterns that can be embedded as subroutines of larger quaternionic algorithms. Multi-path and multi-particle generalizations of the Peres test [87] provide a natural route towards few-qubit network experiments on photonic or microwave platforms that directly constrain the admissible hypercomplex deviations from the standard complex model.

- Embedded quaternionic circuits on existing processors. Our embedding results show that any n-quaternionic qubit circuit can be represented as a complex circuit on physical qubits with polynomial overhead. This yields a concrete implementation recipe for gate-based quantum computers: choose a genuinely quaternionic algorithm (for instance, one that exploits quaternionic symmetries in -invariant simulation), compile its gates into the corresponding complex unitaries, and execute the resulting circuit on current superconducting, trapped-ion, or photonic hardware. Structural tests of the underlying number system, analogous to the real-vs-complex dimension-witness games already realized on superconducting and photonic platforms [88,89], can then be formulated directly in our quaternionic circuit language and implemented as small benchmark circuits on present-day devices.

- Encoded octonionic dynamics and measurement-only schemes. For octonions, where no native hardware implementation is known, two complementary strategies emerge. First, as in our complexity analysis, one can digitally encode each logical octo-qubit into a small register of complex qubits and compile octonionic gates—including order-sensitive associator corrections—into ordinary multi-qubit gates, yielding proof-of-principle simulations of octonionic computation on noisy intermediate-scale devices. Second, the measurement-only model based on equiangular projections associated with the octonions [9] suggests that certain octonionic circuit identities can be tested via sequences of projective measurements on highly entangled resource states (cluster-state or topological architectures). Both approaches connect the abstract octonionic model to concrete experimental protocols that fit within the standard toolbox of quantum computing experiments.

Appendix A.3.1. Gate Overhead from Associativity Management

- A first computational step calculates the intermediate state . This operation must be performed using a gate set and on a state that lives within a single quaternionic subalgebra.

- A second step calculates . This again must be associative.

- A third step computes the final state .

Appendix A.3.2. State-Space Overhead: The Cost of Complex Embedding

Appendix B. Path-Ordered Propagators and Magnus Expansion with Associators

Appendix B.1. Path-Ordered Evolution in

Appendix B.2. Magnus-like Expansion

Appendix B.3. Strategy 1: Restriction to Associative Subalgebras—Additional Details

Appendix B.4. The Non-Associative Hamiltonian and Its Consequences—Additional Details

Appendix B.4.1. Operator Ordering and Emergent Non-Local Effects

- Grouping 1:This corresponds to a physical process where the 1-2 interaction occurs first, followed by the resulting field interacting with particle 3 via the channel. Using the Fano plane rules, this yields the following:

- Grouping 2:This corresponds to a different process where the 2-3 interaction () and the 1-3 interaction () combine first, and the resulting field then interacts with particle 1. This yields the following:

Appendix B.4.2. The Breakdown of Energy Conservation: A Formal Derivation

Appendix B.4.3. The Principle of Associative Confinement

For any given computational step, all operators, gates, and state vector amplitudes involved must belong to a single, pre-defined associative subalgebra of the octonions.

- The associator for any product of three elements within the subalgebra is identically zero: .

- Consequently, the Hamiltonian becomes an effective quaternionic Hamiltonian. The anomalous term in the Heisenberg equation of motion vanishes, and energy is conserved.

- The time evolution operator becomes a standard, well-defined exponential. The Dyson series is valid, and the evolution is path-independent.

- The composition of gates becomes associative, and the standard circuit model is recovered.

Appendix B.4.4. Implementing Gates in an Associative Subspace

Appendix C. Seven-Factor Decomposition and Decoupling Sequences

Appendix C.1. Seven-Factor Algebraic Synthesis

Appendix C.2. Associator-Suppressing Dynamical Decoupling

| Algorithm A1 Associator-Suppressing Decoupling (ASD) |

|

References

- Hurwitz, A. Über die Composition der quadratischen Formen von beliebig vielen Variablen. In Nachrichten der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse; Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften: Göttingen, Germany, 1898; pp. 309–316. [Google Scholar]

- Baez, J.C. The Octonions. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 2002, 39, 145–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, D.; Jauch, J.M.; Schiminovich, S.; Speiser, D. Foundations of Quaternion Quantum Mechanics. J. Math. Phys. 1962, 3, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, S.L. Quaternionic Quantum Mechanics and Quantum Fields; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rúa, J.H. Mathematical Aspects of Quantum Computing on Quaternions and Octonions. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, J.M.; Schneeberger, W.A. Quaternionic Computing. arXiv 2008, arXiv:quant-ph/0307017. [Google Scholar]

- Gantner, J. On the Equivalence of Complex and Quaternionic Quantum Mechanics. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1709.07289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graydon, M.A. Quaternionic quantum dynamics on complex Hilbert spaces. Found. Phys. 2013, 43, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M.; Shokrian-Zini, M.; Wang, Z. Quantum Computing with Octonions. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.08580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, P. Lecture Notes on Electron Correlation and Magnetism; World Scientific: Singapore, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dray, T.; Janesky, J.; Manogue, C.A. Octonionic Hermitian Matrices with Non-Real Eigenvalues. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebr. 2000, 10, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A. Mathematical Problems of Non-perturbative Quantum General Relativity. arXiv 1994, arXiv:gr-qc/9302024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altland, A.; Zirnbauer, M.R. Nonstandard symmetry classes in mesoscopic normal-superconducting hybrid structures. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 55, 1142–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, R. The periodicity theorem for the classical groups and some of its applications. Adv. Math. 1970, 4, 353–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M.; Fock, V. Beweis des Adiabatensatzes. Z. Phys. 1928, 51, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullion, T.; Baker, D.B.; Conradi, M.S. New, compensated Carr-Purcell sequences. J. Magn. Reson. 1990, 89, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeberlen, U.; Waugh, J.S. Coherent averaging effects in magnetic resonance. Phys. Rev. 1968, 175, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, L.; Knill, E.; Lloyd, S. Dynamical Decoupling of Open Quantum Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 2417–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ji, W.; Kong, X.; Wang, M.; Sun, H.; Zhou, J.; Chai, Z.; Rong, X.; Shi, F.; Wang, Y.; et al. Single-Shot Readout of a Solid-State Electron Spin Qutrit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 132, 060601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, S.; Ducati, G. The octonionic eigenvalue problem. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2012, 45, 315203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayro-Corrochano, E.; Solis-Gamboa, S. Quaternion Quantum Neurocomputing. Int. J. Wavelets Multiresolut. Inf. Process. 2022, 20, 204001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicata, G.; Bagarello, F.; Gargano, F.; Spagnolo, S. Quantum mechanical settings inspired by RLC circuits. J. Math. Phys. 2018, 59, 042112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, Y.; Fu, L. Topological Crystalline Insulators and Topological Superconductors: From Concepts to Materials. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2015, 6, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbóth, J.K.; Oroszlány, L.; Pályi, A. A Short Course on Topological Insulators: Band Structure and Edge States in One and Two Dimensions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernevig, B.A.; Hughes, T.L.; Zhang, S.-C. Quantum Spin Hall Effect and Topological Phase Transition in HgTe Quantum Wells. Science 2006, 314, 1757–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernevig, B.A.; Hughes, T.L. Topological Insulators and Topological Superconductors; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bistritzer, R.; MacDonald, A.H. Transport between twisted graphene layers. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 245412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bistritzer, R.; MacDonald, A.H. Moiré bands in twisted double-layer graphene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 12233–12237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brihuega, I.; Mallet, P.; González-Herrero, H.; de Laissardière, G.T.; Ugeda, M.M.; Magaud, L.; Gómez-Rodríguez, J.M.; Ynduráin, F.; Veuillen, J.-Y. Unraveling the Intrinsic and Robust Nature of van Hove Singularities in Twisted Bilayer Graphene by Scanning Tunneling Microscopy and Theoretical Analysis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 196802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzezicki, W.; Hyart, T. Hidden Chern number in one-dimensional non-Hermitian chiral-symmetric systems. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 161105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bychkov, Y.A.; Rashba, E.I. Oscillatory effects and the magnetic susceptibility of carriers in inversion layers. JETP Lett. 1984, 39, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, E.V.; Novoselov, K.S.; Morozov, S.V.; Peres, N.M.R.; dos Santos, J.M.B.L.; Nilsson, J.; Guinea, F.; Geim, A.K.; Neto, A.H.C. Biased Bilayer Graphene: Semiconductor with a Gap Tunable by the Electric Field Effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 216802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayssol, J. Introduction to Dirac materials and topological insulators. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1303.5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikin, P.M.; Lubensky, T.C. Principles of Condensed Matter Physics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 495–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Z.; Zhang, J.; Feng, X.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, M.; Li, K.; Ou, Y.; Wei, P.; Wang, L.; et al. Experimental Observation of the Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect in a Magnetic Topological Insulator. Science 2013, 340, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-C.; Niu, Q. Berry Phase, Hyperorbits, and the Hofstadter Spectrum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1348–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Jiang, L.; Wu, S.; Lyu, B.; Li, H.; Chittari, B.L.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Shi, Z.; Jung, J.; et al. Evidence of a gate-tunable Mott insulator in a trilayer graphene moiré superlattice. Nat. Phys. 2019, 15, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Sharpe, A.L.; Fox, E.J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L.; Lyu, B.; Li, H.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; et al. Tunable correlated Chern insulator and ferromagnetism in a moiré superlattice. Nature 2020, 579, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittari, B.L.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Jung, J. Gate-Tunable Topological Flat Bands in Trilayer Graphene Boron-Nitride Moiré Superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 016401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.-K.; Teo, J.C.; Schnyder, A.P.; Ryu, S. Classification of topological quantum matter with symmetries. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2016, 88, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-K.; Schnyder, A.P. Classification of reflection-symmetry-protected topological semimetals and nodal superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 205136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Kemmer, J.; Pengg, Y.; Thomson, A.; Arora, H.; Polski, R.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, H.; Alicea, J.; Refael, G.; et al. Electronic correlations in twisted bilayer graphene near the magic angle. Nat. Phys. 2019, 15, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Sarma, S.; Adam, S.; Hwang, E.H.; Rossi, E. Electronic transport in two-dimensional graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 407–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila, M.E.; Xian, L.; Cahangirov, S.; Rubio, A.; Le Lay, G. Germanene: A novel two-dimensional germanium allotrope akin to graphene and silicene. New J. Phys. 2014, 16, 095002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Heer, W.A.; Berger, C.; Wu, X.; Sprinkle, M.; Hu, Y.; Ruan, M.; Stroscio, A.J.; First, P.N.; Haddon, R.; Piot, B.; et al. Epitaxial graphene electronic structure and transport. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2010, 43, 374007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Léséleuc, S.; Lienhard, V.; Scholl, P.; Barredo, D.; Weber, S.; Lang, N.; Büchler, H.P.; Lahaye, T.; Browaeys, A. Observation of a symmetry-protected topological phase of interacting bosons with Rydberg atoms. Science 2019, 365, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, D.; Jozsa, R. Rapid solution of problems by quantum computation. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. Math. Phys. Sci. 1992, 439, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Wang, C.; Shaw, J.C.; Cheng, R.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, X.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, A.; et al. Lateral epitaxial growth of two-dimensional layered semiconductor heterojunctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 1024–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyakonov, M.; Perel, V. Current-induced spin orientation of electrons in semiconductors. Phys. Lett. A 1971, 35, 459–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyakonov, M.; Perel, V. Spin relaxation of conduction electrons in noncentrosymmetric semiconductors. JETP Lett. 1971, 13, 467–469. [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi, T.; Gilkey, P.B.; Hanson, A.J. Gravitation, gauge theories and differential geometry. Phys. Rep. 1980, 66, 213–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epple, M. Topology, Matter, and Space, I: Topological Notions in 19th-Century Natural Philosophy. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 1998, 52, 297–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezawa, M. Higher-order topological electric circuits and topological corner resonance on the breathing kagome and pyrochlore lattices. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 201402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezawa, M. Electric circuits for non-Hermitian Chern insulators. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 081401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Nagaosa, N.; Takahashi, K.S.; Asamitsu, A.; Mathieu, R.; Ogasawara, T.; Yamada, H.; Kawasaki, M.; Tokura, Y.; Terakura, K. The Anomalous Hall Effect and Magnetic Monopoles in Momentum Space. Science 2003, 302, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, M.; Molenkamp, L. (Eds.) Topological Insulators; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Kane, C.L. Time reversal polarization and a Z2 adiabatic spin pump. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 195312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Kane, C.L. Topological insulators with inversion symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 045302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Fu, N.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, D.; Ke, S. Extended SSH Model in Non-Hermitian Waveguides with Alternating Real and Imaginary Couplings. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geim, A.K.; Grigorieva, I.V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 2013, 499, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghatak, A.; Das, T. New topological invariants in non-Hermitian systems. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2019, 31, 263001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, X.; Shi, G.; Lei, S.; Lin, Z.; Zou, X.; Ye, G.; Vajtai, R.; Yakobson, B.I.; et al. Vertical and in-plane heterostructures from WS2/MoS2 monolayers. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, N.; Morvan, A.; Marinelli, B.L.; Mitchell, B.K.; Nguyen, L.B.; Naik, R.K.; Chen, L.; Jünger, C.; Kreikebaum, J.M.; Santiago, D.I.; et al. High-fidelity qutrit entangling gates for superconducting circuits. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, A.; Salamo, G.J.; Duchesne, D.; Morandotti, R.; Volatier-Ravat, M.; Aimez, V.; Siviloglou, G.A.; Christodoulides, D.N. Observation of PT-Symmetry Breaking in Complex Optical Potentials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 093902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldane, F.D.M. Model for a Quantum Hall Effect without Landau Levels: Condensed-Matter Realization of the “Parity Anomaly”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1988, 61, 2015–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.C. Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Representations: An Elementary Introduction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.H. On a New Action of the Magnet on Electric Currents. Am. J. Math. 1879, 2, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.H. XVIII. On the “Rotational Coefficient” in Nickel and Cobalt. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1881, 12, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, B.I. Quantized Hall conductance, current-carrying edge states, and the existence of extended states in a two-dimensional disordered potential. Phys. Rev. B 1982, 25, 2185–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenco, A.; Bennett, C.H.; Cleve, R.; DiVincenzo, D.P.; Margolus, N.; Shor, P.; Sleator, T.; Smolin, J.A.; Weinfurter, H. Elementary gates for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 1995, 52, 3457–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.M.; Álvarez, G.A.; Suter, D. Effects of time reversal symmetry in dynamical decoupling. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1110.1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samos Sáenz de Buruaga, N.; Bistroń, R.; Rudziński, M.; Pereira, R.M.C.; Życzkowski, K.; Ribeiro, P. Fidelity decay and error accumulation in random quantum circuits. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2404.11444. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Sanders, B.C.; Kais, S. Qudits and High-Dimensional Quantum Computing. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 589504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.V. Quantal phase factors accompanying adiabatic changes. Proc. R. Soc. A 1984, 392, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ionas, R. An analogue of the Gibbons-Hawking Ansatz for quaternionic Kähler spaces. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.11166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M.H. A simple construction of quantum codes from classical error correcting codes. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 103, 042416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, C.; Simon, S.H.; Stern, A.; Freedman, M.; Das Sarma, S. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2008, 80, 1083–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, V.; Pachos, J.K. A short introduction to topological quantum computation. SciPost Phys. 2017, 3, 021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodjasteh, K.; Viola, L. Dynamically Error-Corrected Gates for Universal Quantum Computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 080501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaev, A.Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 2003, 303, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. Matrix Theory over the Complex Quaternion Algebra. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebr. 2000, 10, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzoi, F.; Gambetta, J.M.; Rebentrost, P.; Wilhelm, F.K. Simple Pulses for Elimination of Leakage in Weakly Nonlinear Qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 110501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorz, L.; Meyer-Scott, E.; Nitsche, T.; Potoček, V.; Gábris, A.; Barkhofen, S.; Jex, I.; Silberhorn, C. Photonic quantum walks with four-dimensional coins. Phys. Rev. Res. 2019, 1, 033036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, A. Proposed test for complex versus quaternion quantum theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1979, 42, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procopio, L.M.; Rozema, L.A.; Wong, Z.J.; Hamel, D.R.; O’Brien, K.; Zhang, X.; Dakic, B.; Walther, P. Single-photon test of hyper-complex quantum theories using a metamaterial. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saruhan, E.I.; von Zanthier, J.; Pleinert, M.-O. Multipath and Multiparticle Tests of Complex versus Hypercomplex Quantum Theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 060201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-D.; Mao, Y.-L.; Weilenmann, M.; Tavakoli, A.; Chen, H.; Feng, L.; Yang, S.-J.; Renou, M.-O.; Trillo, D.; Le, T.P.; et al. Testing Real Quantum Theory in an Optical Quantum Network. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 128, 040402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-C.; Wang, C.; Liu, F.-M.; Wang, J.-W.; Ying, C.; Shang, Z.-X.; Wu, Y.; Gong, M.; Deng, H.; Liang, F.-T.; et al. Ruling Out Real-Valued Standard Formalism of Quantum Theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 128, 040403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhunushaliev, V. Toy Models of a Nonassociative Quantum Mechanics. Adv. High Energy Phys. 2007, 2007, 012387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strategy | Scope | Primary Benefit | Main Overheads/Limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| (M1) Associative confinement | Restores associative composition and tensoring | Sector-change depth/calibration; restricted reachable set under strict confinement. | |

| (M2) -invariant codes | Protected subspaces | Detect associator syndromes; symmetry robustness | Detection only; non-canonical tensoring persists. |

| (M3) ASD (decoupling) | Time-domain control | Cancels leading associator terms; short-time fidelity gains | Higher-order residuals; finite-pulse errors; calibration load. |

| (M4) Seven-factor synthesis | Gate compilation | Systematic construction within associative factors | Depth amplification; error accumulation; suited to simulation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rúa Muñoz, J.H.; Mahecha Gómez, J.E.; Pineda Montoya, S. Quaternionic and Octonionic Frameworks for Quantum Computation: Mathematical Structures, Models, and Fundamental Limitations. Quantum Rep. 2025, 7, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/quantum7040055

Rúa Muñoz JH, Mahecha Gómez JE, Pineda Montoya S. Quaternionic and Octonionic Frameworks for Quantum Computation: Mathematical Structures, Models, and Fundamental Limitations. Quantum Reports. 2025; 7(4):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/quantum7040055

Chicago/Turabian StyleRúa Muñoz, Johan Heriberto, Jorge Eduardo Mahecha Gómez, and Santiago Pineda Montoya. 2025. "Quaternionic and Octonionic Frameworks for Quantum Computation: Mathematical Structures, Models, and Fundamental Limitations" Quantum Reports 7, no. 4: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/quantum7040055

APA StyleRúa Muñoz, J. H., Mahecha Gómez, J. E., & Pineda Montoya, S. (2025). Quaternionic and Octonionic Frameworks for Quantum Computation: Mathematical Structures, Models, and Fundamental Limitations. Quantum Reports, 7(4), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/quantum7040055