Lightweight Design and Topology Optimization of a Railway Motor Support Under Manufacturing and Adaptive Stress Constraints

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methodology

2.1. Materials’ Description

2.2. Methodology

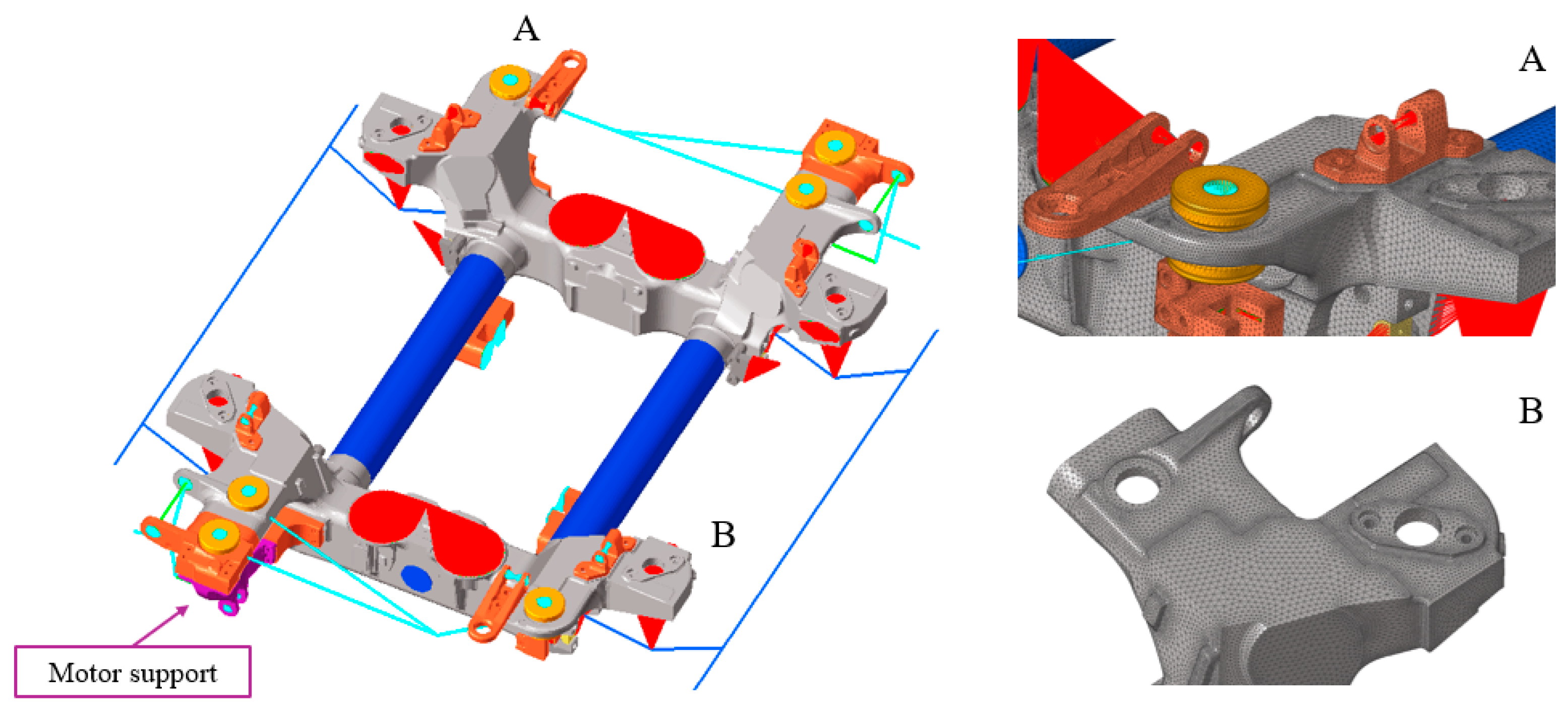

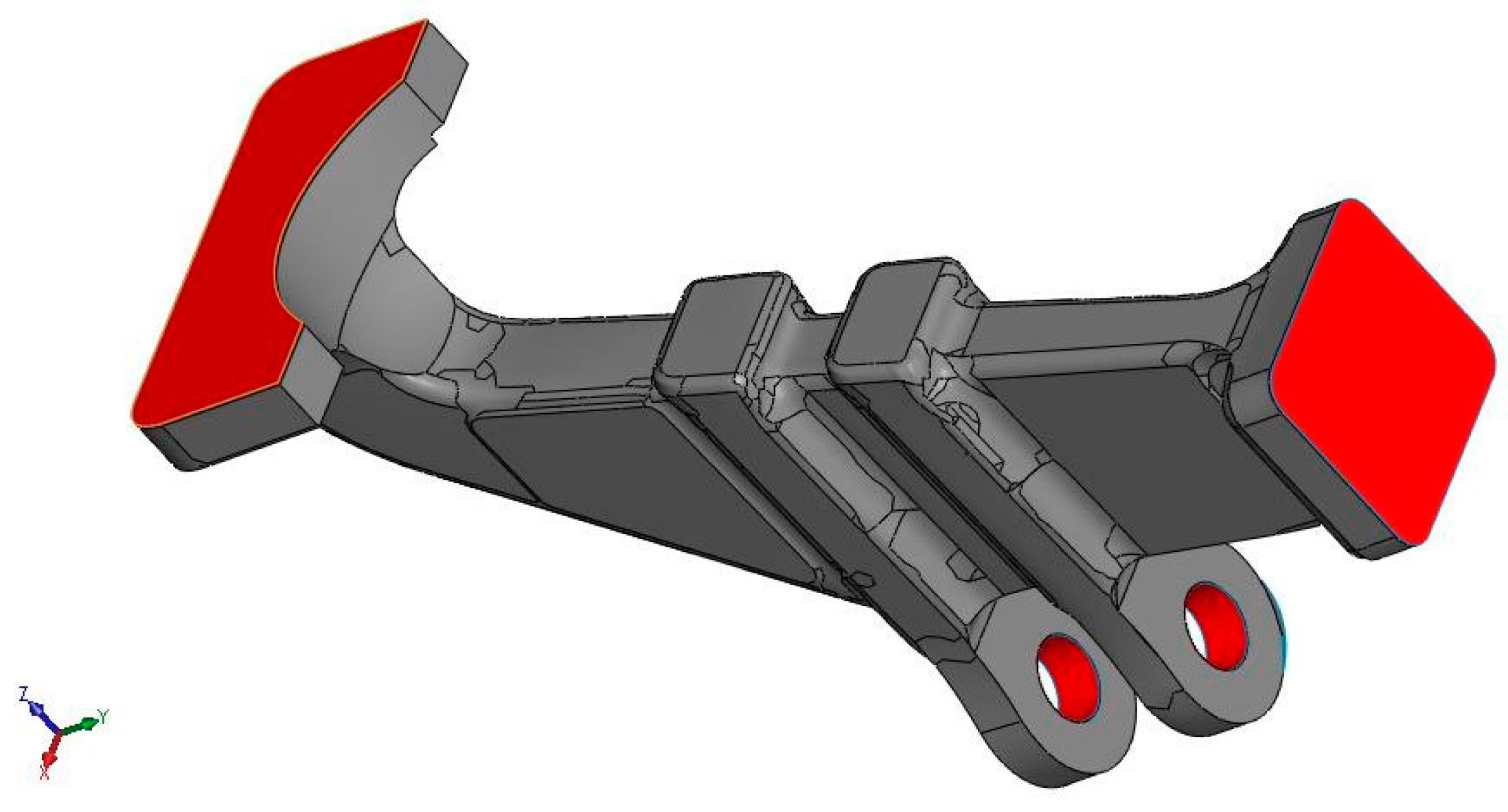

2.3. Description of the Support

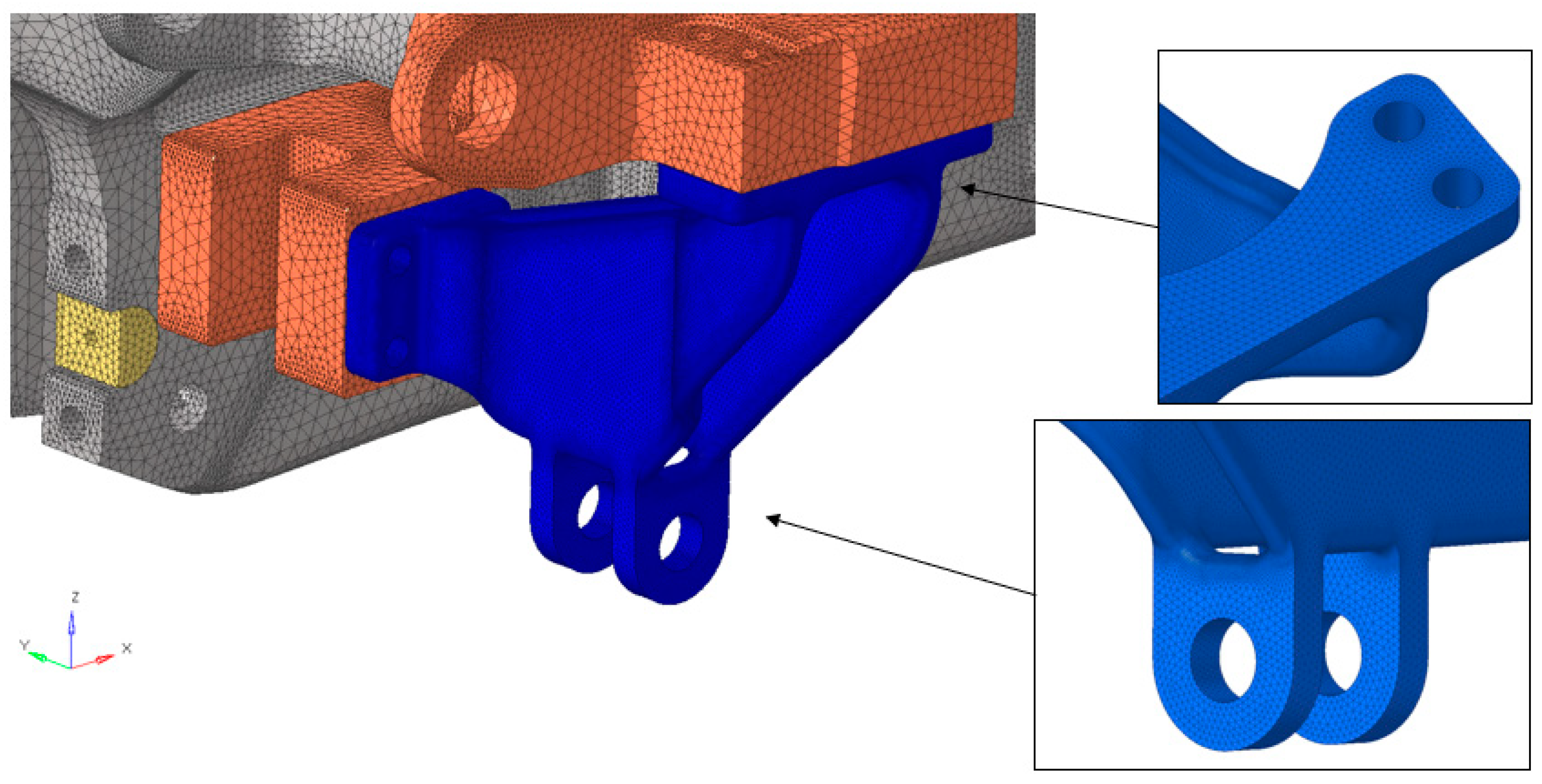

2.4. Bogie System: High Fidelity FE Model

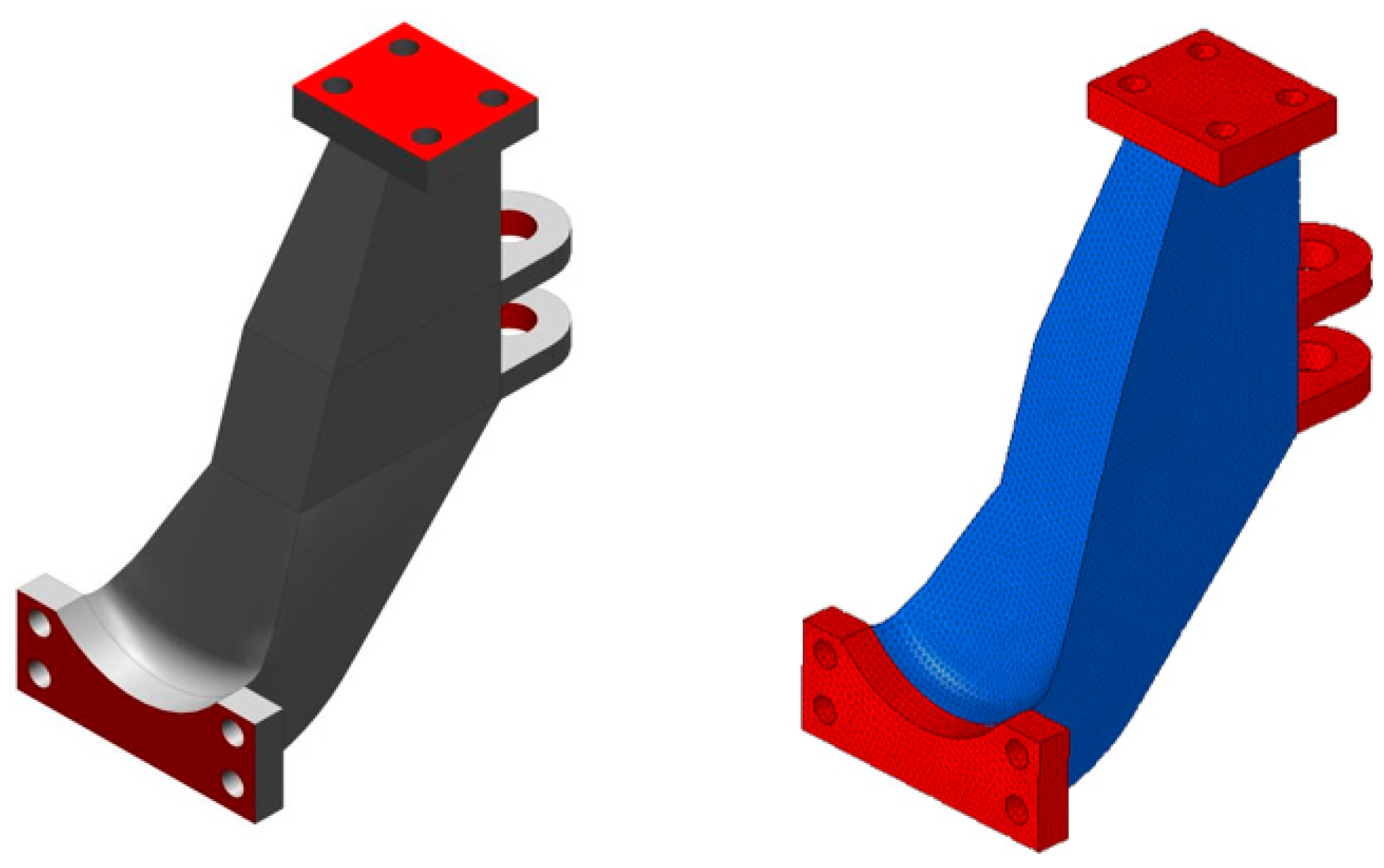

2.5. Optimization Settings

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis Setting and Preliminary Results

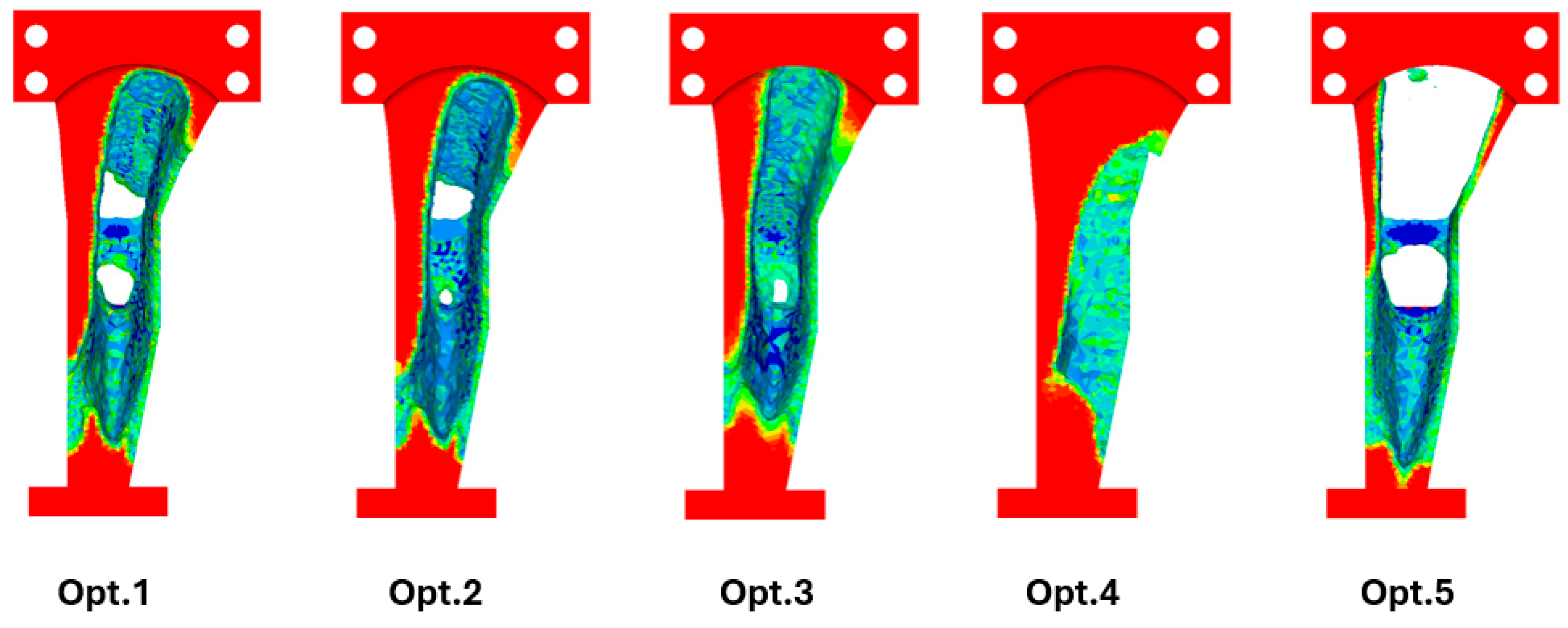

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis Framework

3.3. Optimization Algorithm and Stress Formulation

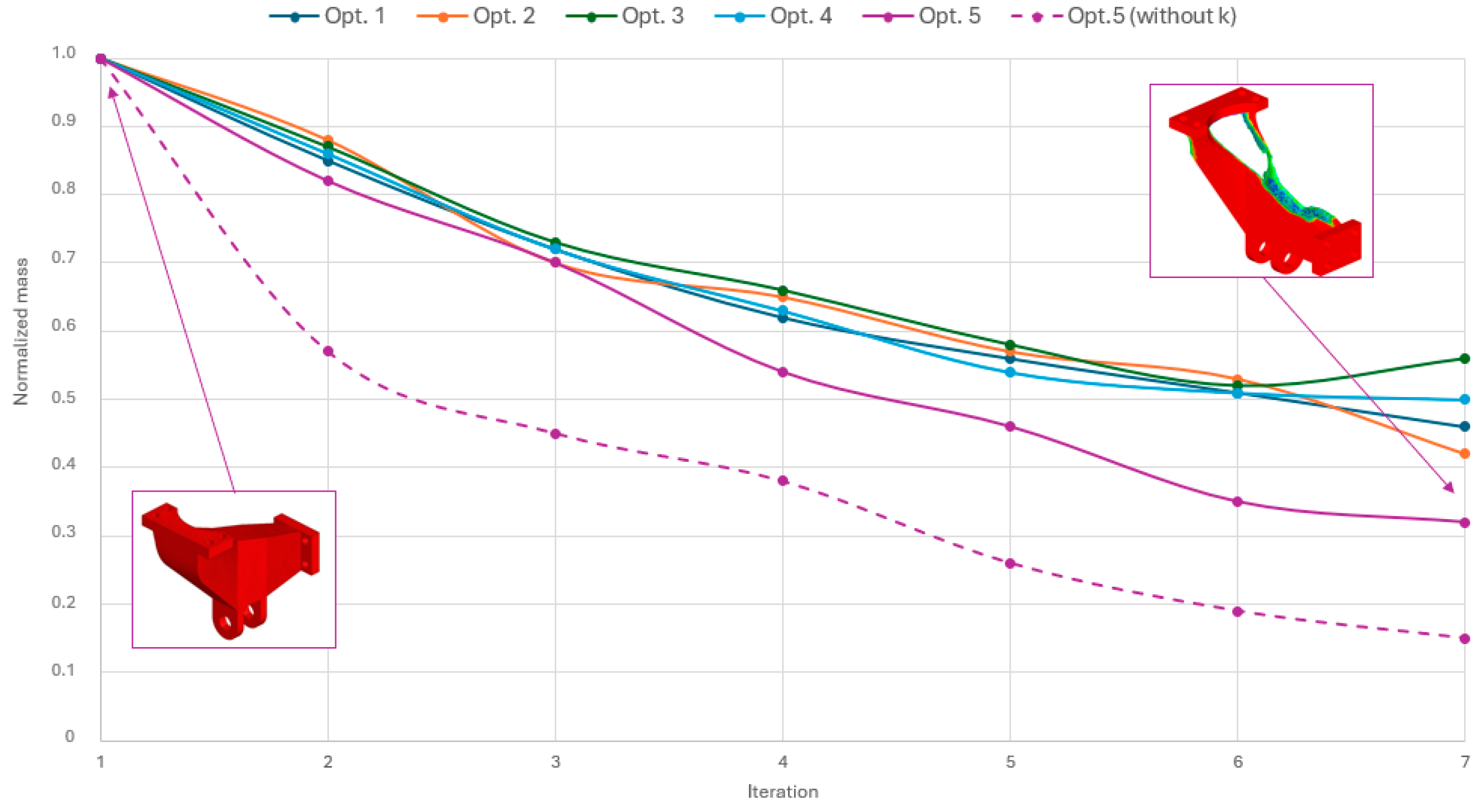

3.4. Optimization Process and Sensitivity Results

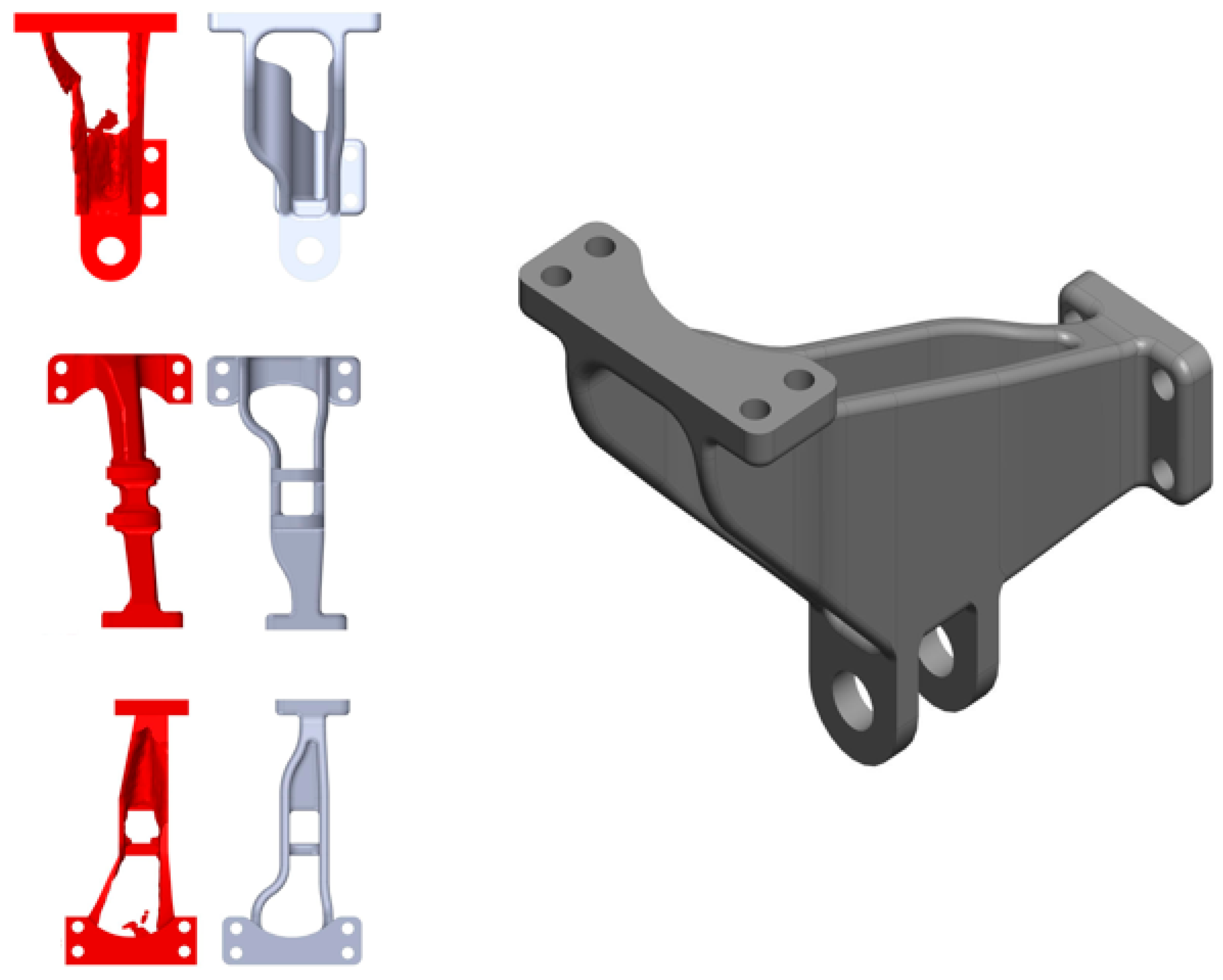

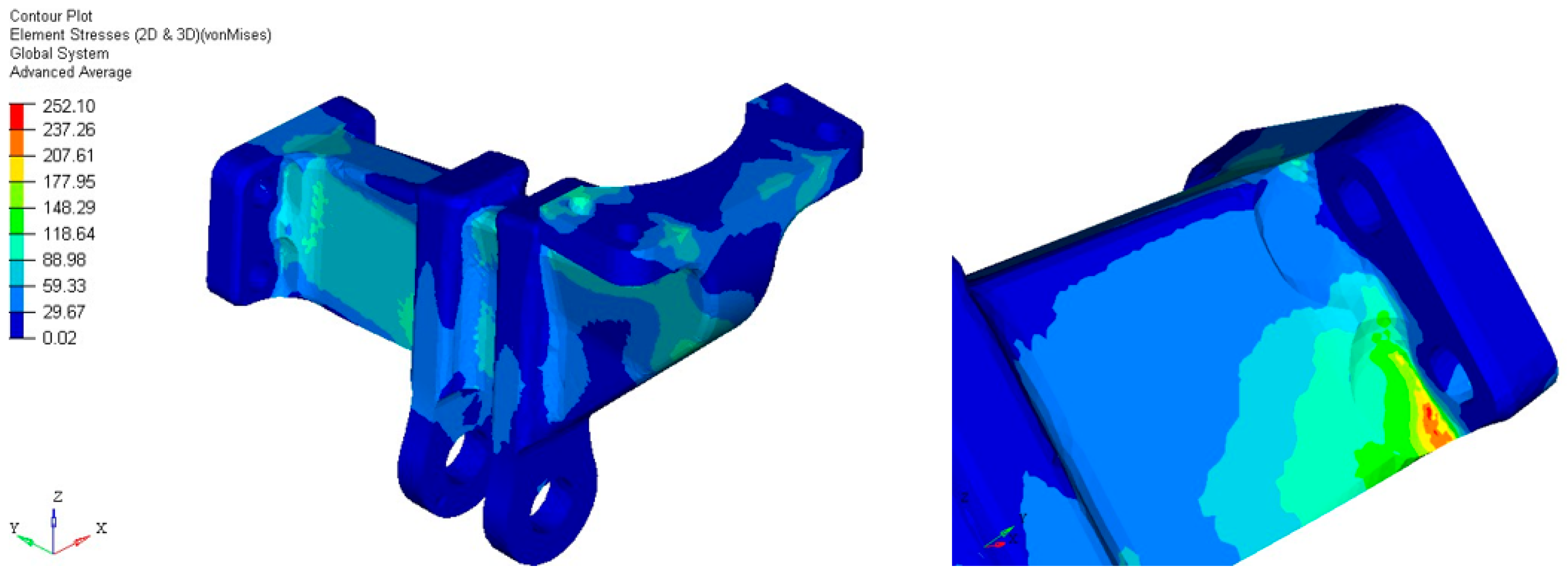

3.5. Innovated Geometry and Assessment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matsimbi, M.; Nziu, P.K.; Masu, L.M.; Maringa, M. Topology optimization of automotive body structures: A review. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 4282–4296. [Google Scholar]

- Jankovics, D.; Barari, A. Customization of automotive structural components using additive manufacturing and topology optimization. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; An, D.; Ma, L.; He, Y. A survey of multi-scale optimization methods in fiber-reinforced polymer composites design for automobile applications. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billur, S.; Raju, G.U. Mass optimization of automotive radial arm using FEA for modal and static structural analysis. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1116, 01211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viqaruddin, M.; Reddy, D.R. Structural optimization of control arm for weight reduction and improved performance. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 9230–9236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazzuti, M.; Baldini, A.; Bertocchi, E.; Costi, D.; Torricelli, E.; Moruzzi, P. High performance automotive chassis design: A topology optimization based approach. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2011, 44, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Guo, Q.; Yang, S.; Liao, X.; Qi, C. A size optimization procedure for irregularly spaced spot weld design of automotive structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021, 166, 108015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yan, L.; Qi, C. An adaptive multi-step varying-domain topology optimization method for spot weld design of automotive structures. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2018, 59, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qin, H.; Zhong, H.; Lv, C. An efficient structural optimization approach for the modular automotive body conceptual design. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2018, 58, 1275–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.; Lee, J.; Jang, W.; Han, D.; Kim, N.; Lee, H. Manufacturability-constrained optimization for enhancing quality and suitability of injection-molded short fiber-reinforced plastic/metal hybrid automotive structures. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2023, 66, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.; Jang, W.; Han, D.; Kim, N.; Lee, H. Strength and manufacturability enhancement of a composite automotive component via an integrated finite element/artificial neural network multi-objective optimization approach. Compos. Struct. 2023, 327, 117694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, A.; Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Pinelli, L. Improving aeromechanical performance of compressor rotor blisk with topology optimization. Energies 2024, 17, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, C.; Zhou, L.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, W. A review of topology optimization for additive manufacturing: Status and challenges. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2020, 34, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Munro, D.; Wang, C.; Van Keulen, F.; Wu, J. Space-time topology optimization for additive manufacturing. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2019, 61, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabiston, G.; Kim, I. 3D topology optimization for cost and time minimization in additive manufacturing. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2020, 61, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegard, T.; Paulino, G. Bridging topology optimization and additive manufacturing. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2016, 53, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietropaoli, M.; Ahlfeld, R.; Montomoli, F.; Ciani, A.; D’Ercole, M. Design for additive manufacturing: Internal channel optimization. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2016: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Volume 5B: Heat Transfer (V05BT11A013), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 13–17 June 2016; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch, K.L.; Thole, K.A. Experimental investigation of numerically optimized wavy microchannels created through additive manufacturing. J. Turbomach. 2017, 140, 021002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.G.; Koo, J.S.; Jung, H.S. A lightweight design approach for an EMU carbody using a material selection method and size optimization. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2016, 30, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, J. Integral consideration of the lightweight design for railway vehicles. In Proceedings of the Young Researchers Seminar, Copenhagen, Denmark, 8–10 June 2011; Technical University of Denmark: Lyngby, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, B.R.; Luo, Y.X.; Peng, Q.M.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, H.; Yang, Z. Multidisciplinary design optimization of lightweight carbody for fatigue assessment. Mater. Des. 2020, 194, 108910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. Dynamic size optimization approach to support railway carbody lightweight design process. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2022, 237, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. A strategy for lightweight designing of a railway vehicle car body including composite material and dynamic structural optimization. Railw. Eng. Sci. 2023, 31, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, A.; Motavalli, M.; Shahverdi, M. Recent advancements in the applications of fiber-reinforced polymer structures in railway industry—A review. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Ying, G.; Guo, W.; Yang, Y.; Xu, P.; Alqahtani, M.S. High-velocity impact behaviour of curved GFRP composites for rail vehicles: Experimental and numerical study. Polym. Test. 2022, 116, 107774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. Comparative analysis and dynamic size optimization of aluminum and carbon fiber thin-walled structures of a railway vehicle car body. Materials 2025, 18, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasso, M.; Gallone, A.; Genovese, A.; Macera, L.; Penta, F.; Pucillo, G.; Strano, S. Composite material design for rail vehicle innovative lightweight components. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering, London, UK, 1–3 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. Design and optimization of a hybrid railcar structure with multilayer composite panels. Materials 2025, 18, 5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.; Rahman, M.R.; Baini, R.; Bakri, M.K.B. Advances in Sustainable Polymer Composites; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arifurrahman, F.; Budiman, B.A.; Aziz, M. On the lightweight structural design for electric road and railway vehicles using fiber reinforced polymer composites—A review. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2018, 1, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, J.; Rong, Y.; Liu, H.; Feng, X.; Zhao, Z. Structural topology optimization method with adaptive support design. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2025, 201, 103830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Cai, J.; Yi, J.; Zhou, Q.; Rong, J. Integrated topology and size optimization for frame structures considering displacement, stress, and stability constraints. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2024, 67, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Xie, Y. Simultaneously optimizing supports and topology in structural design. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2021, 197, 103633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changizi, N.; Jalalpour, M. Robust topology optimization of frame structures under geometric or material properties uncertainties. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2017, 56, 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl, T. Simultaneous topology optimization of structure and supports. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2002, 23, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersborg, A.R.; Andreasen, C.S. An explicit parameterization for casting constraints in gradient driven topology optimization. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2011, 44, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. Development of a methodology for railway bolster beam design enhancement using topological optimization and manufacturing constraints. Eng 2024, 5, 1485–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzheim, L.; Graf, G. A review of optimization of cast parts using topology optimization: I—Topology optimization without manufacturing constraints. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2005, 30, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.; Radford, D.W. Design optimization of a composite rail vehicle anchor bracket. Urban Rail Transit 2021, 7, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.K.; Shukla, S. Topology optimization: Weight reduction of Indian railway freight bogie side frame. Int. J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 6, 4374–4383. [Google Scholar]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. Development of a design procedure combining topological optimization and a multibody environment: Application to a tram motor bogie frame. Vehicles 2024, 6, 1843–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. A new strategy for railway bogie frame designing combining structural–topological optimization and sensitivity analysis. Vehicles 2024, 6, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M. Non-parametric optimization of railway wheel web shape based on fatigue design criteria. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 134, 105463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsabbagh, A.; El-Kashif, E.; Sayed, S. Mechanical and fatigue behavior of G22NiMoCr5-6 and G18NiMoCr3-6 used in heavy-duty crawler track plates. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2024, 71, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Fan, H.; Feng, K. Effects of tempering process on microstructure and mechanical properties of G18NiMoCr3-6. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 493, 012141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Li, Y.; Jin, X.; Chen, B.; Tang, C.; Zhu, P. Effect of tempering process on microstructure and mechanical properties of G18NiMoCr3-6 cast steel. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 394, 032128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callister, W.D.; Rethwisch, D.G. Materials Science and Engineering, 4th ed.; EdiSES: Napoli, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zanardi Fonderie S.p.A. Ductile Austempered Iron (ADI). 2025. Available online: https://zanardifonderie.com/it/ghisa-sferoidale-austemperata-adi/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Zanardi Fonderie, S.p.A. Main Characteristics of ADI and IDI Cast Irons. 2025. Available online: https://www.zanardifonderie.com/wp-content/uploads/aca-Infosheet-1-Material-properties-ADI-Structural-grades.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Società Alluminio Veneto S.p.A. European Standards EN 1676—Aluminium Alloy Ingots for Remelting and EN 1706—Castings: Chemical Composition and Mechanical Properties. 2023. Available online: https://www.sav-al.com/file?oid=5e299db410834b0439bb3d8a (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- EN 13749:2021; Railway Applications—Wheelsets and Bogies—Method of Specifying the Structural Requirements of Bogie Frames. BSI Standards: London, UK, 2021.

- Jameson, A. Gradient Based Optimization Methods. MAE Technical Report No, (2057). 1995. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Antony-Jameson/publication/267248024_Gradient_Based_Optimization_Methods/links/545ae39c0cf2c16efbbbca26/Gradient-Based-Optimization-Methods.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

| Material | Young’s Modulus [MPa] | Poisson’s Ratio | Shear Modulus [MPa] | Density [kg/m3] | Yield Strength [MPa] | Ultimate Strength [MPa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G18NiMoCr3 | 206,800 | 0.29 | 80,155 | 7820 | 700 | 830 |

| GJS-1050-6 | 170,000 | 0.27 | 66,929 | 7200 | 700 | 1050 |

| Al-Cu4MnMg | 72,000 | 0.33 | 27,068 | 2790 | 310 | 370 |

| Parameters and Settings of Optimization Problem | ||

|---|---|---|

| Global settings | Objective | min (Weighted compliance) |

| Mass constraint | Mass fraction < 0.5 | |

| Stress constraint | ||

| Technological settings | Minimum feature size | 10 mm |

| Draw single | Removing material along a reference direction | |

| Scenario of Load (SL) | Description |

|---|---|

| SL 1—Turnout (Switch Passage) | The applied loads originate from the carbody weight, bogie inertia, and mounted equipment during vehicle passage over turnouts. The constraints are applied at the wheel contact points. |

| SL 2—Curving | The applied loads result from the combined effects of the carbody, bogie inertia, and onboard equipment under curved track operation, with a distribution pattern different from LC1. Constraints are applied at the wheel locations. |

| SL 3—Coupling Impact | The applied loads derive from the vehicle coupling event, generating an acceleration equivalent to 3 g on the bogie mass. Constraints are applied at the wheel contact points. |

| SL 4—Lifting Condition | The applied loads correspond to vehicle lifting operations, with the bogies suspended below the carbody. Constraints are applied at the wheel contact regions. |

| SL 5—Short-Circuit Condition | The applied loads are induced by a short-circuit event occurring in the traction motor. Constraints are applied at the wheel positions. |

| SL 6—Inertial Masses | The applied loads are associated with the inertial effects of the suspended masses acting on the bogie frame. Constraints are applied at the wheel locations. |

| SL 7—Dampers Action | The applied loads originate from the reaction forces transmitted by the damping devices. Constraints are applied at the wheel contact points. |

| Case ID | Material | Draw | Min. Feature Size [mm] | Constraint Setup | Test Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opt.1 | G18NiMoCr3 | Z-axis | 25 | Mass fraction < 0.5 | Material sensitivity |

| Opt.2 | GJS-1050-6 | Z-axis | 25 | Mass fraction < 0.5 | Material sensitivity |

| Opt.3 | Al-Cu4MnMg | Z-axis | 25 | Mass fraction < 0.5 | Material sensitivity |

| Opt.4 | GJS-1050-6 | X-axis | 25 | Mass fraction < 0.5 | Manufacturing constraint—draw direction |

| Opt.5 | GJS-1050-6 | Z-axis | 10 | Mass fraction < 0.5 | Manufacturing constraint—feature size |

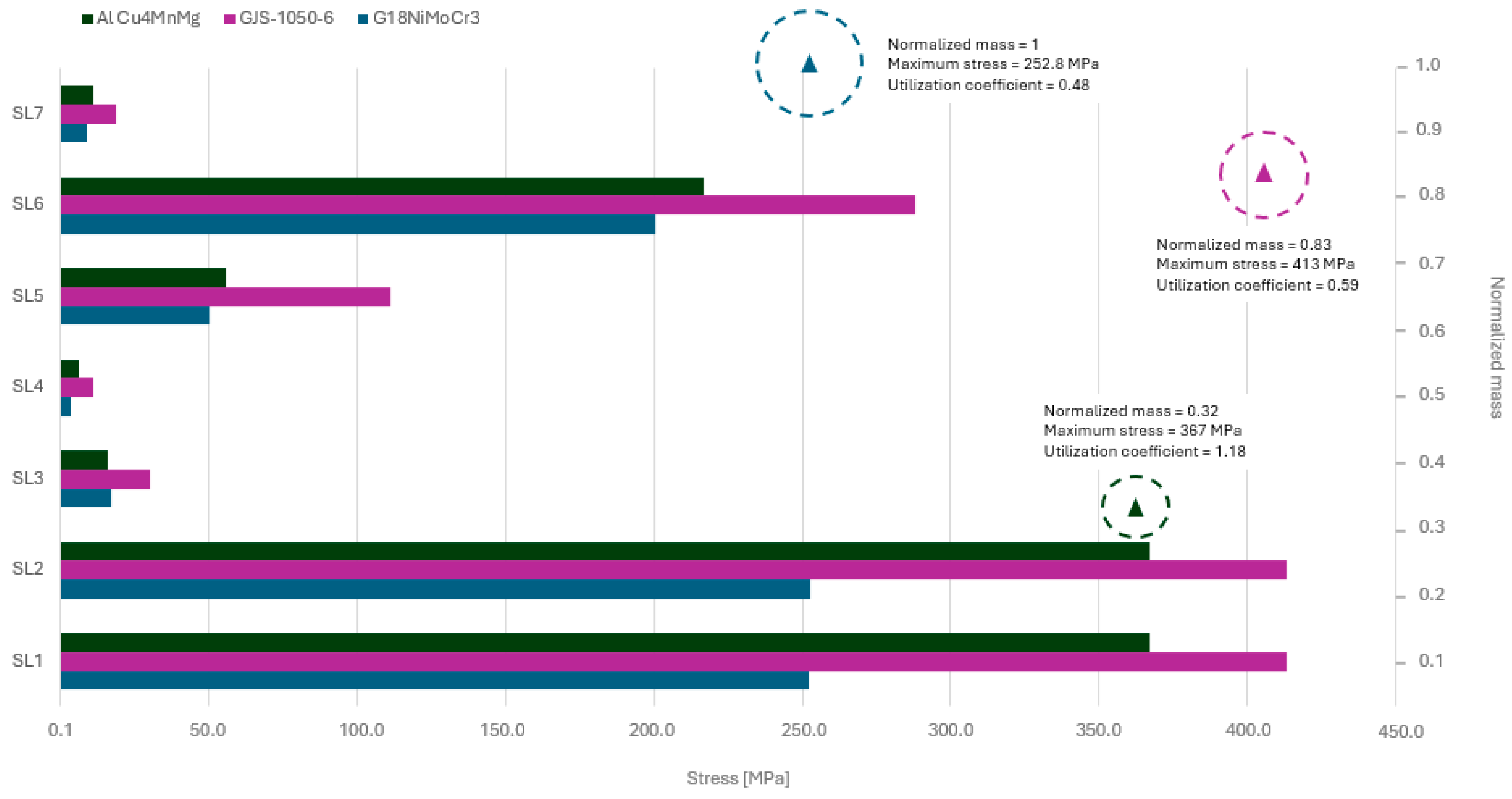

| G18NiMoCr3 | GJS-1050-6 | Al Cu4MnMg | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Load Case | σc [MPa] | U | σc [MPa] | U | σc [MPa] | U |

| SL1 | 252.0 | 0.48 | 413 | 0.59 | 367 | 1.18 |

| SL2 | 252.8 | 0.48 | 413 | 0.59 | 367 | 1.18 |

| SL3 | 17.3 | 0.03 | 30 | 0.04 | 16 | 0.05 |

| SL4 | 3.8 | 0.01 | 11 | 0.02 | 6 | 0.02 |

| SL5 | 50.3 | 0.10 | 111 | 0.16 | 56 | 0.18 |

| SL6 | 200.3 | 0.38 | 288 | 0.41 | 217 | 0.70 |

| SL7 | 9.0 | 0.02 | 19 | 0.03 | 11 | 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. Lightweight Design and Topology Optimization of a Railway Motor Support Under Manufacturing and Adaptive Stress Constraints. Vehicles 2026, 8, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles8010003

Cascino A, Meli E, Rindi A. Lightweight Design and Topology Optimization of a Railway Motor Support Under Manufacturing and Adaptive Stress Constraints. Vehicles. 2026; 8(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles8010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleCascino, Alessio, Enrico Meli, and Andrea Rindi. 2026. "Lightweight Design and Topology Optimization of a Railway Motor Support Under Manufacturing and Adaptive Stress Constraints" Vehicles 8, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles8010003

APA StyleCascino, A., Meli, E., & Rindi, A. (2026). Lightweight Design and Topology Optimization of a Railway Motor Support Under Manufacturing and Adaptive Stress Constraints. Vehicles, 8(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles8010003