Lightweight Aluminum–FRP Crash Management System Developed Using a Novel Hybrid Forming Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Manufacturing of Metal–FRP Hybrid and FRP Structures

1.2. Finite Element Modeling

1.3. Target and Structure of the Work

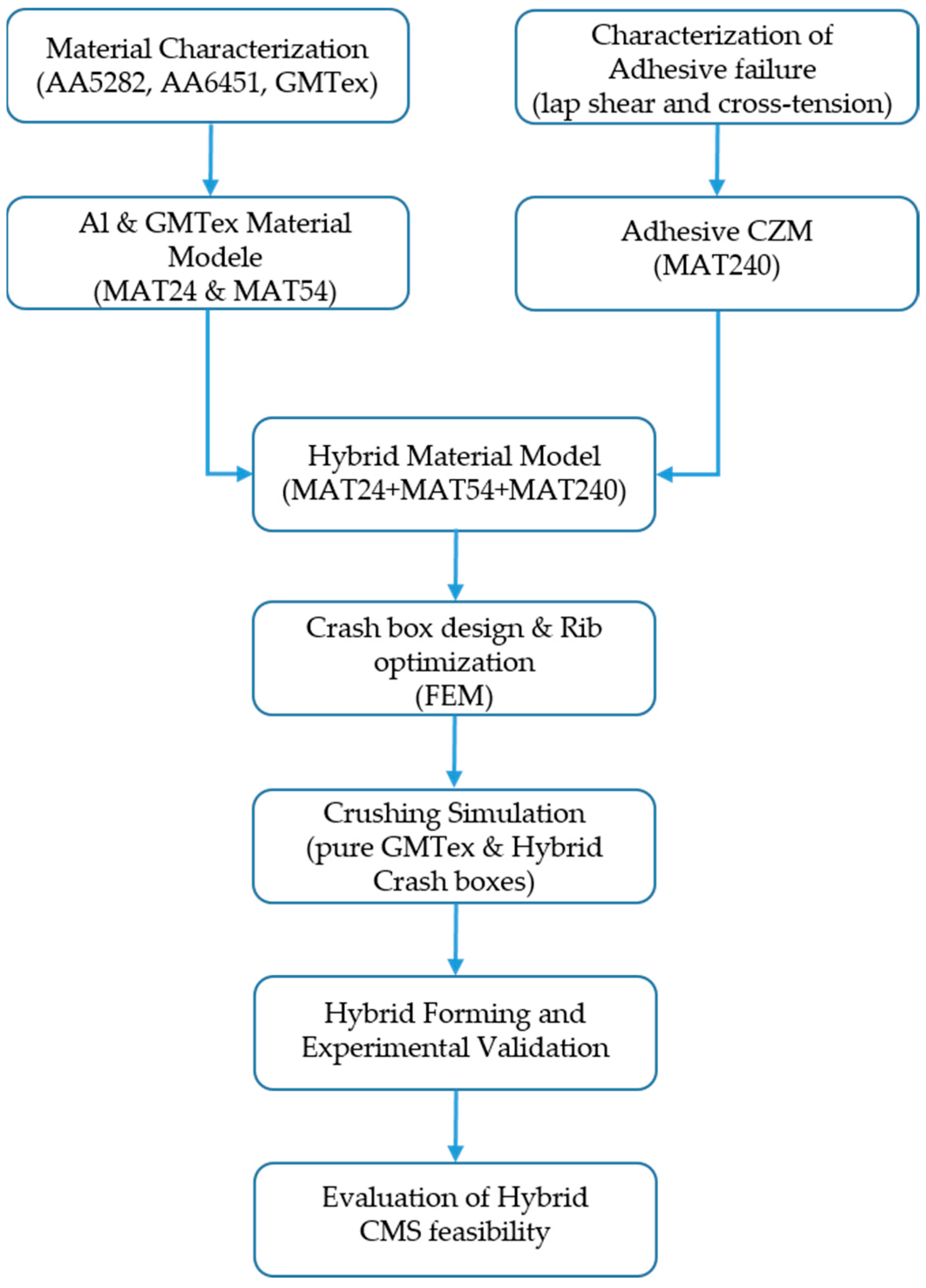

2. Methods

2.1. Material Selection

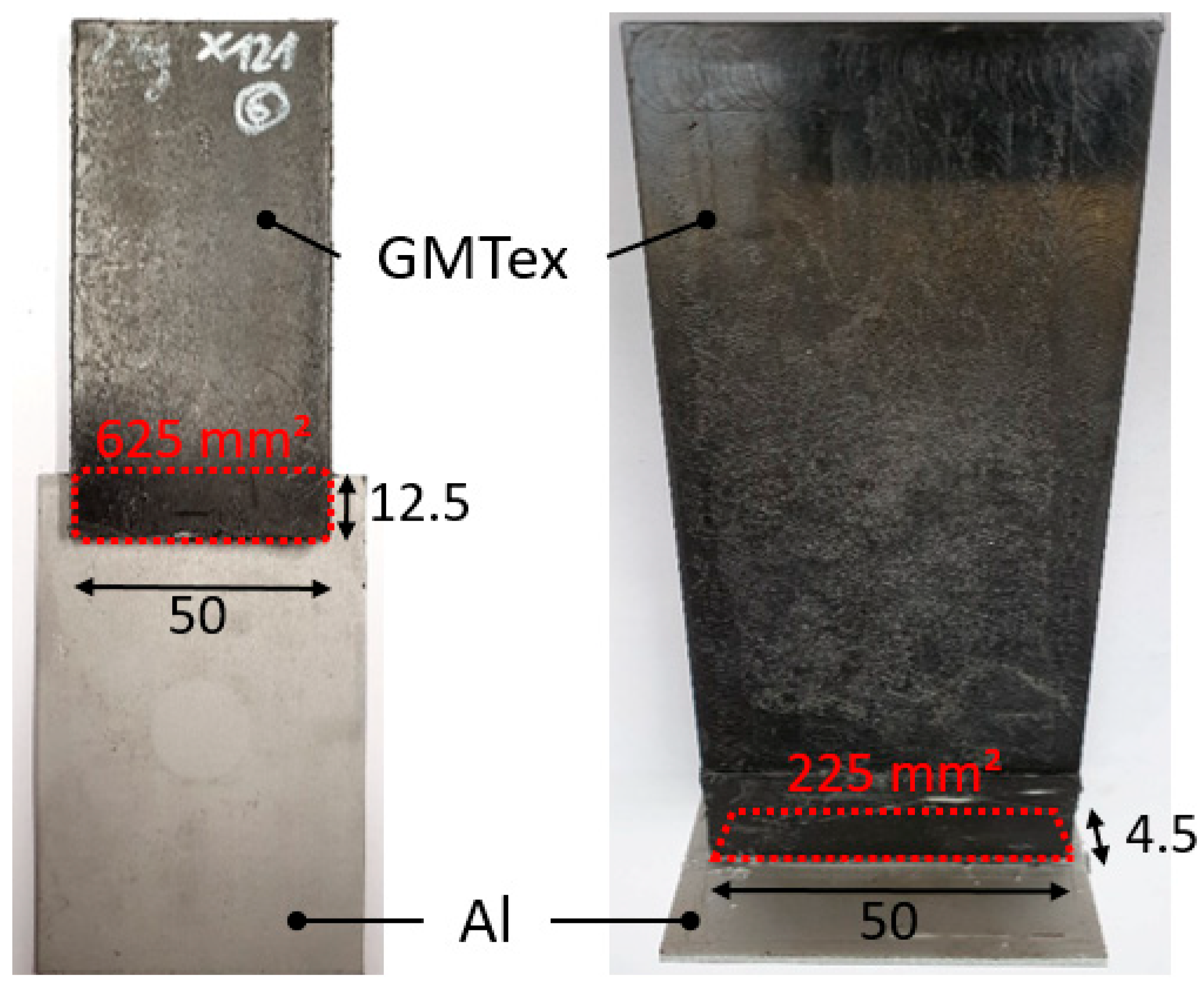

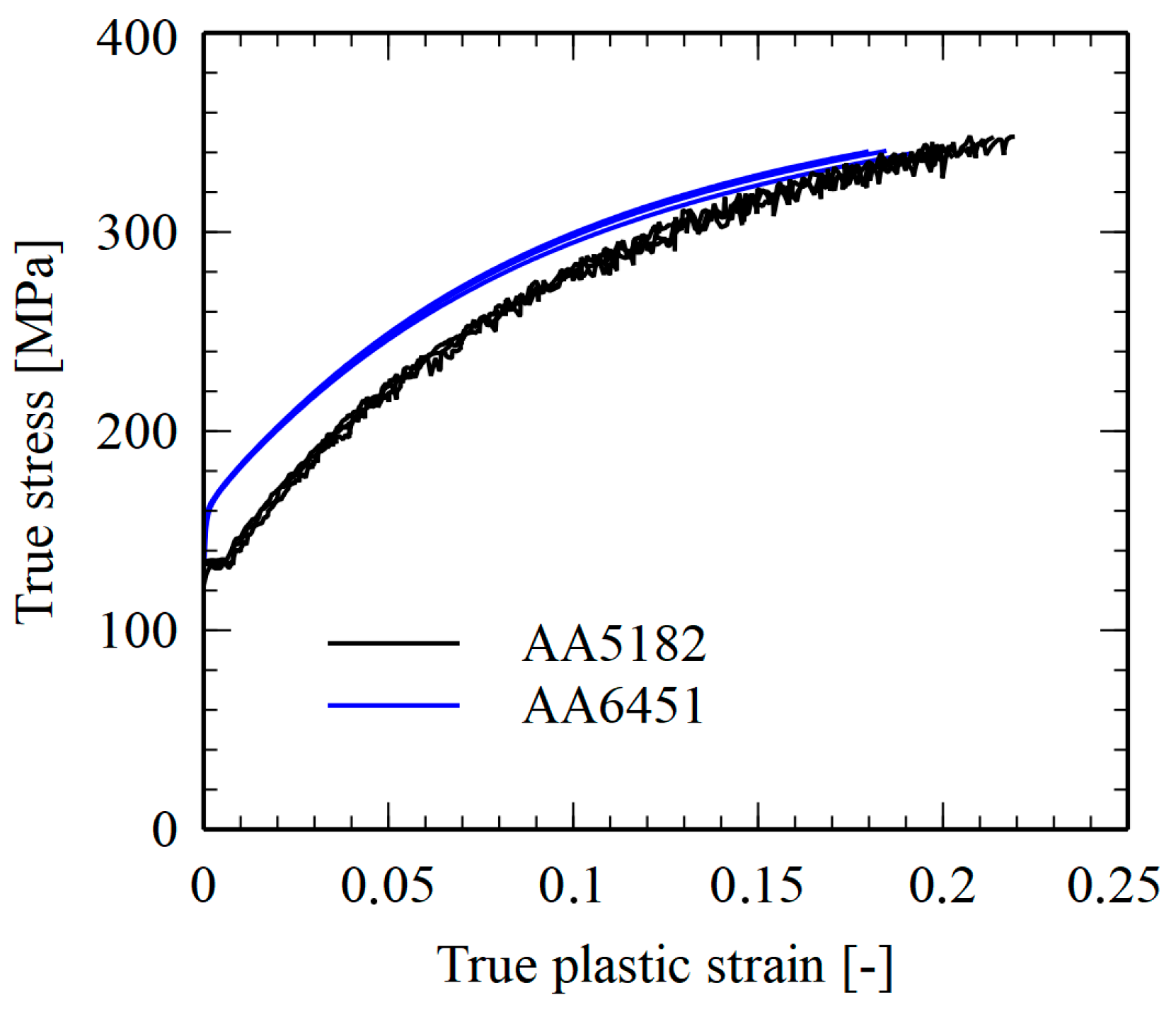

2.2. Material Characterization

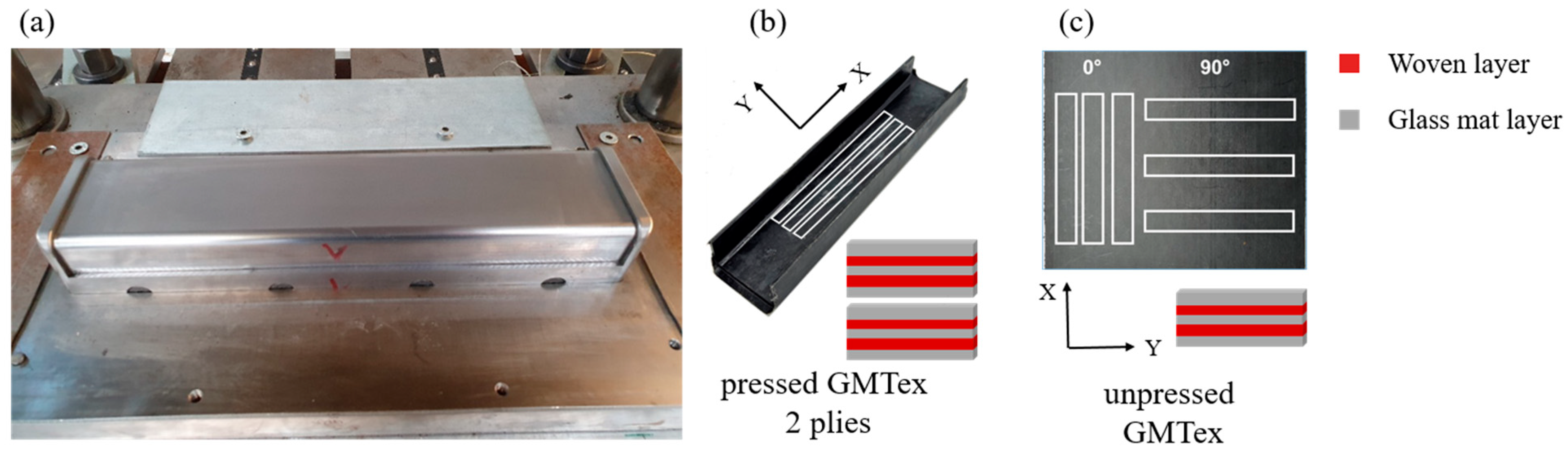

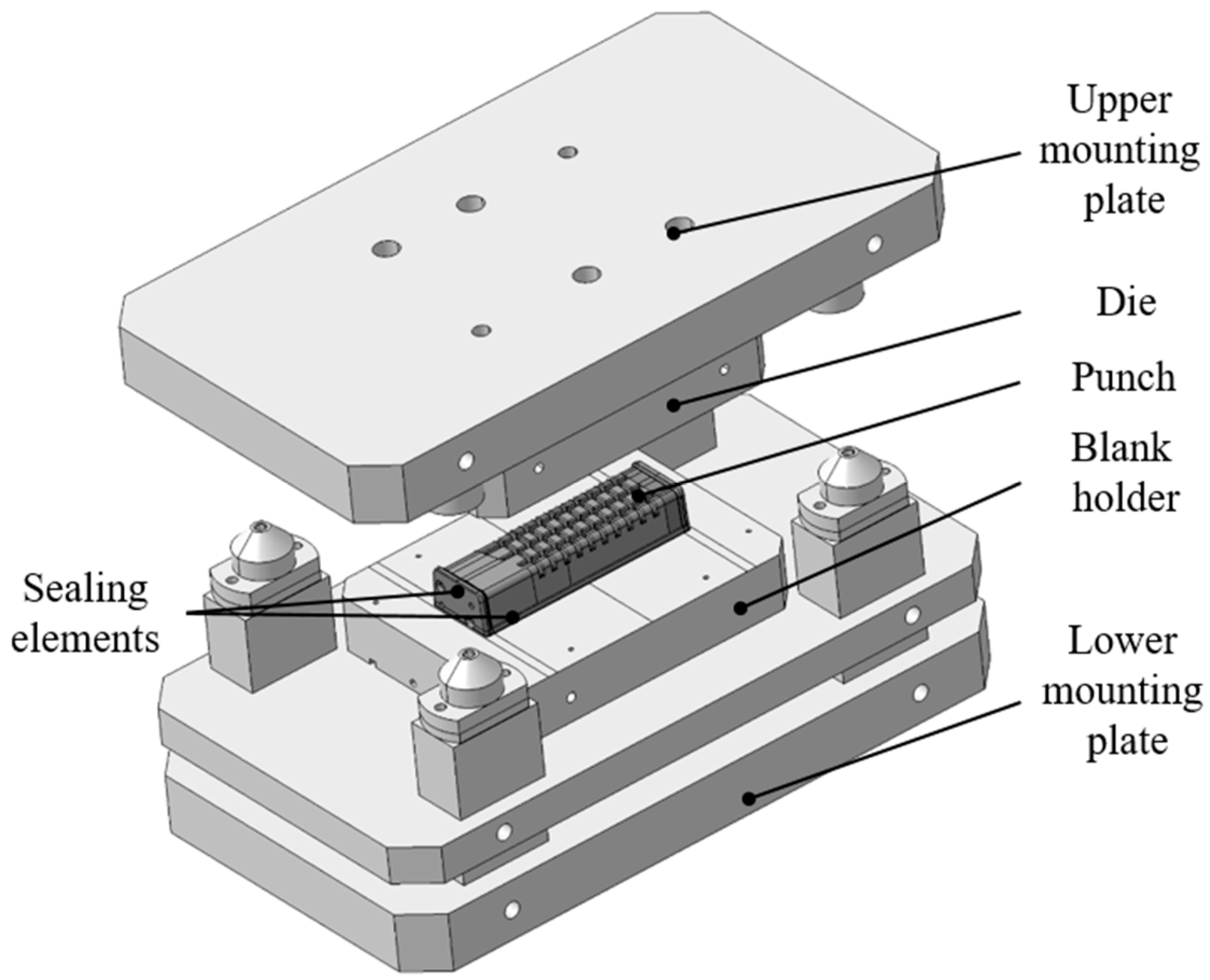

2.3. Hydraulic Press and Forming Tool Concept

2.4. Drop Tower Test

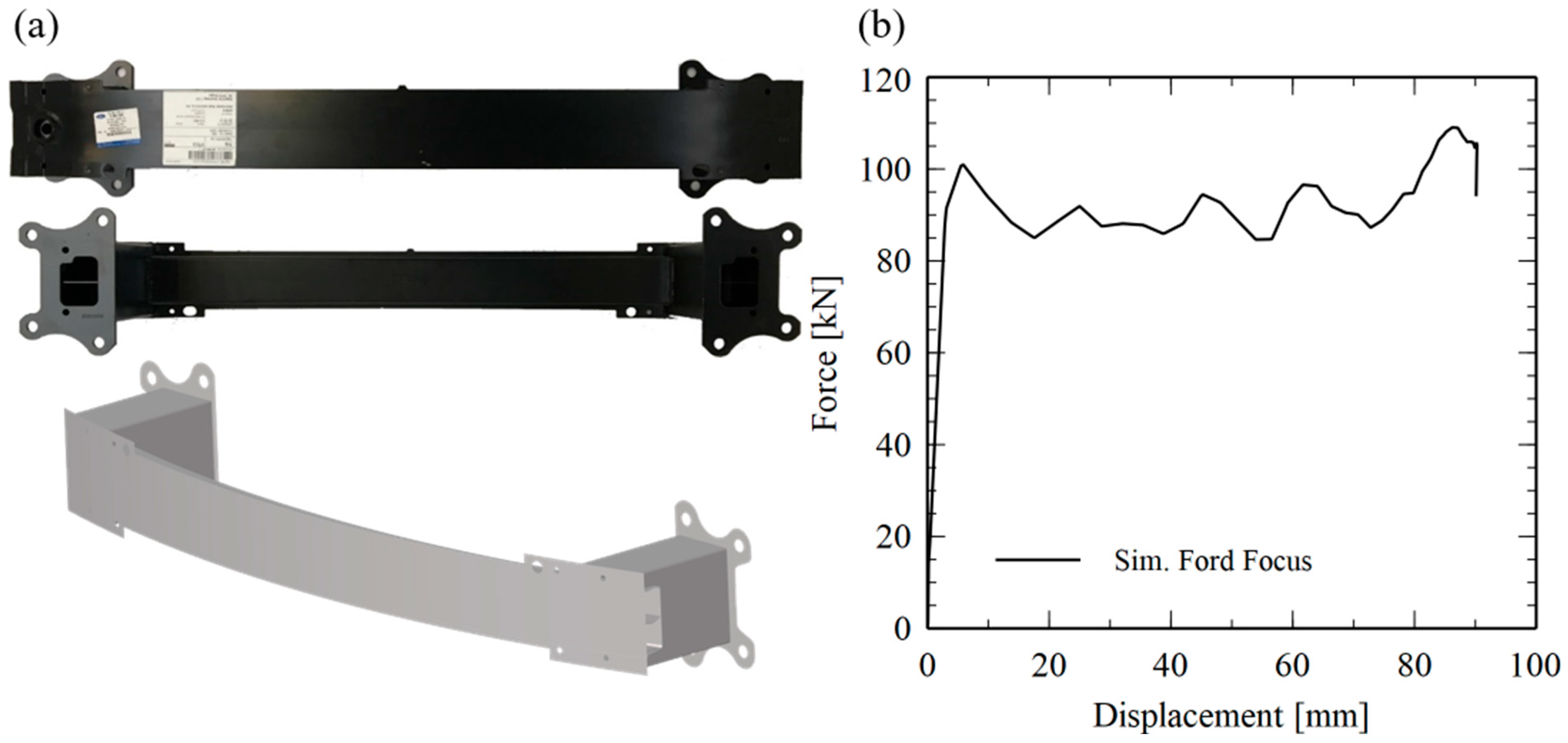

2.5. Benchmarking and Target Setting

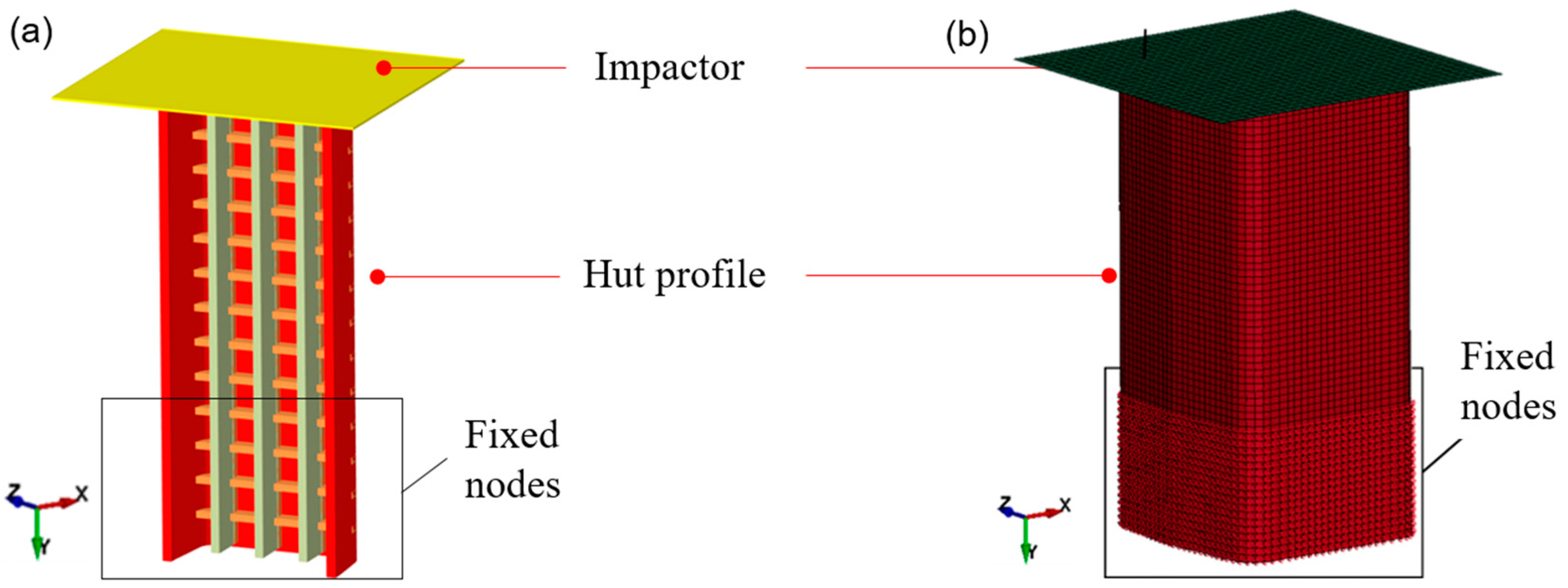

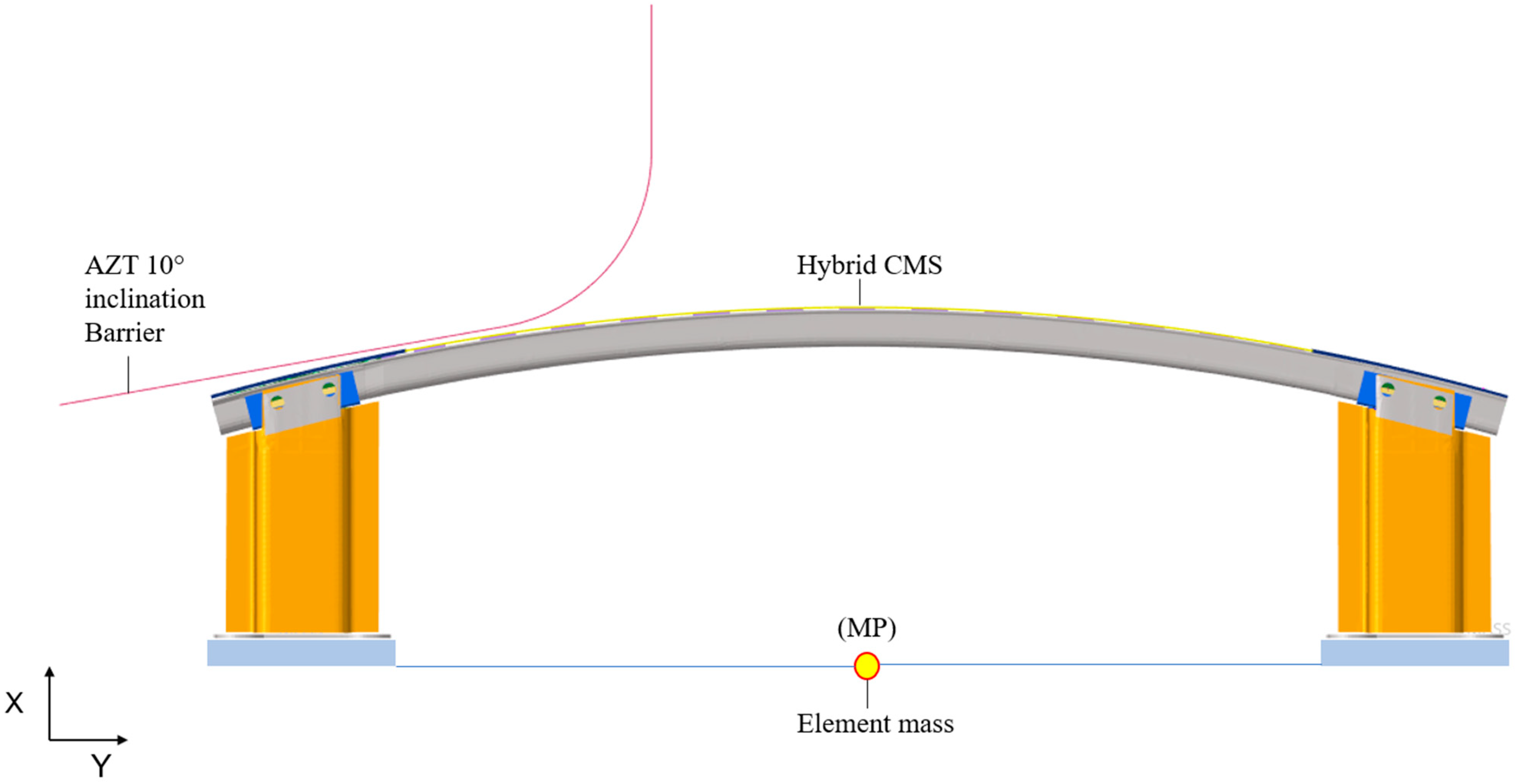

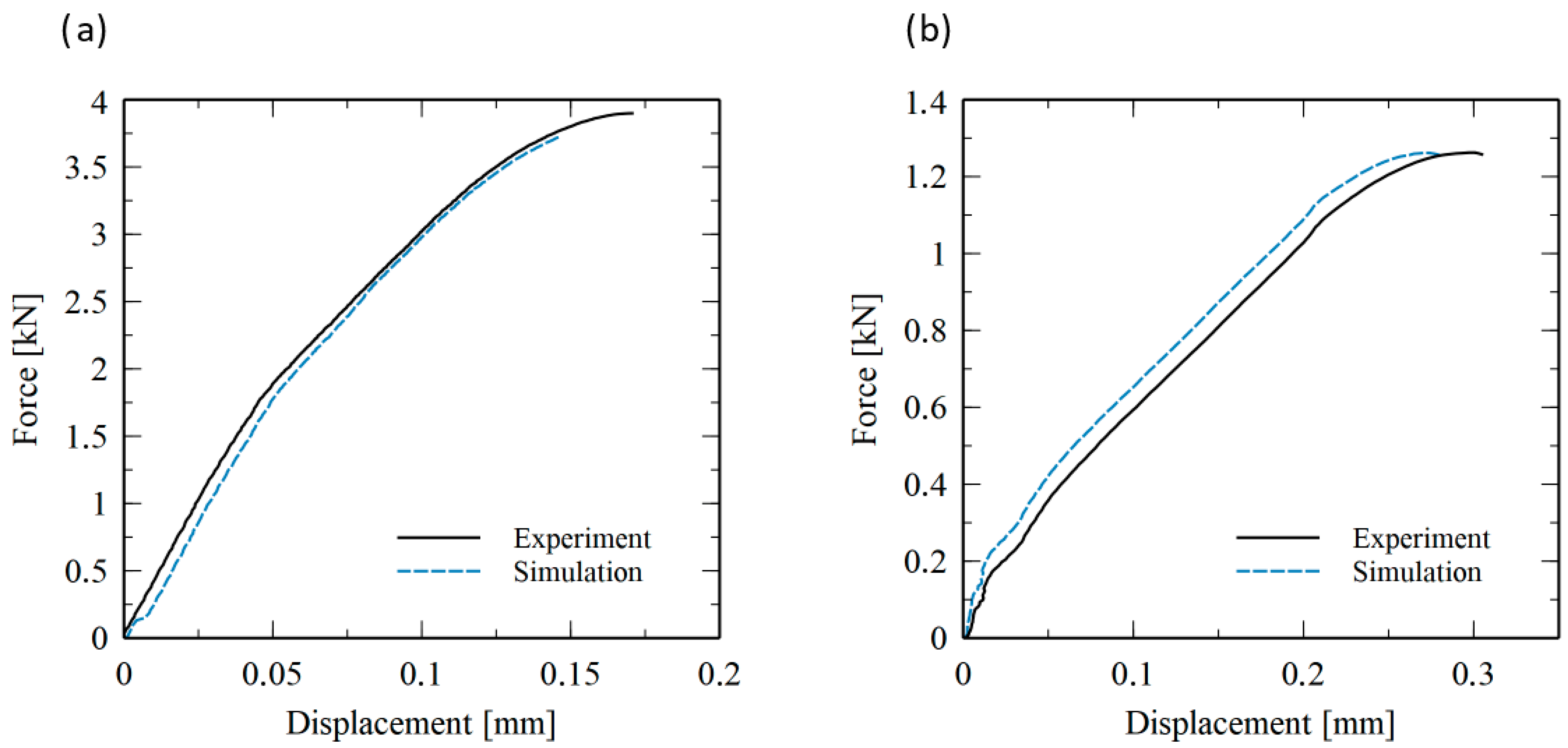

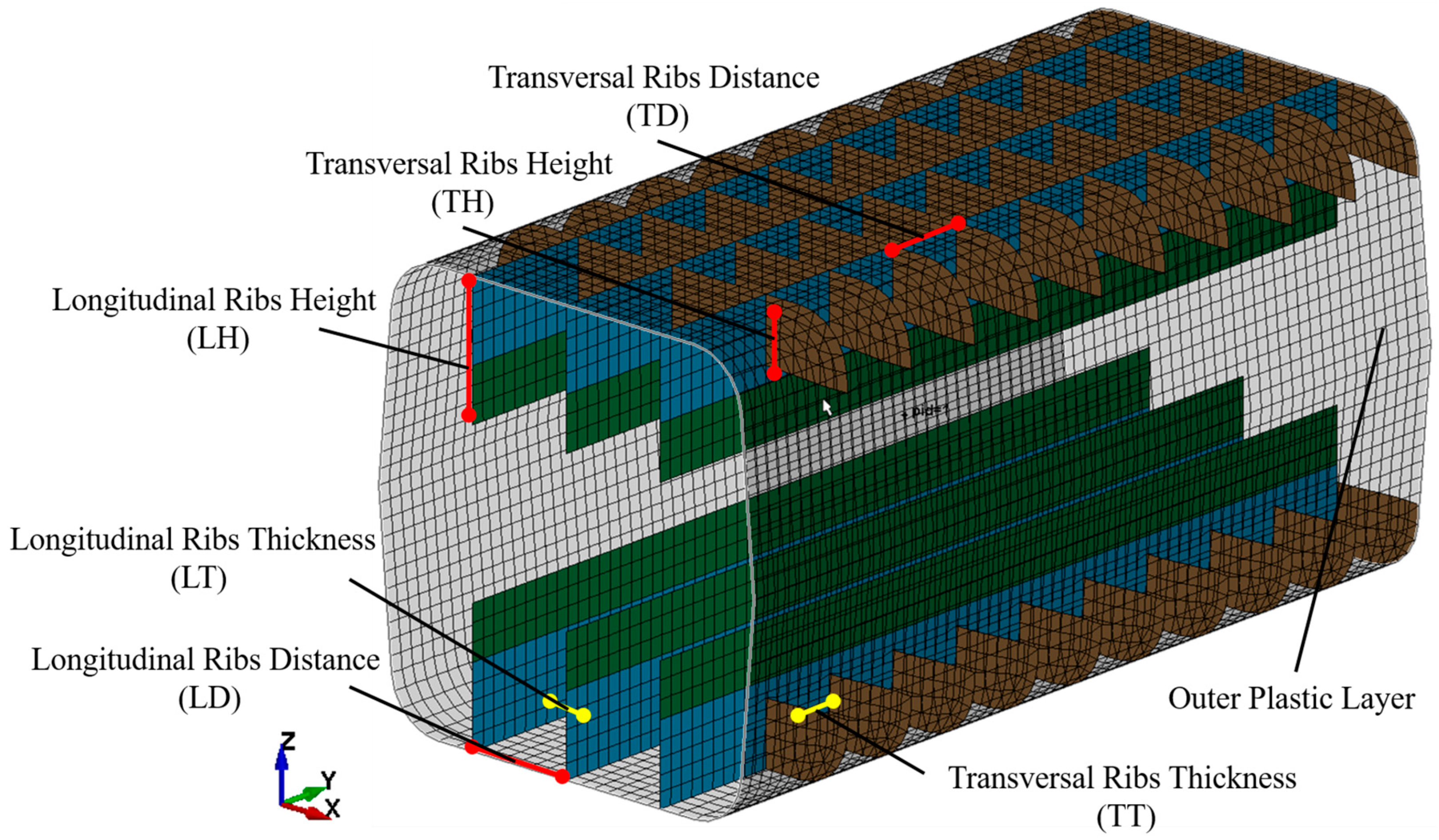

2.6. Finite Element Models

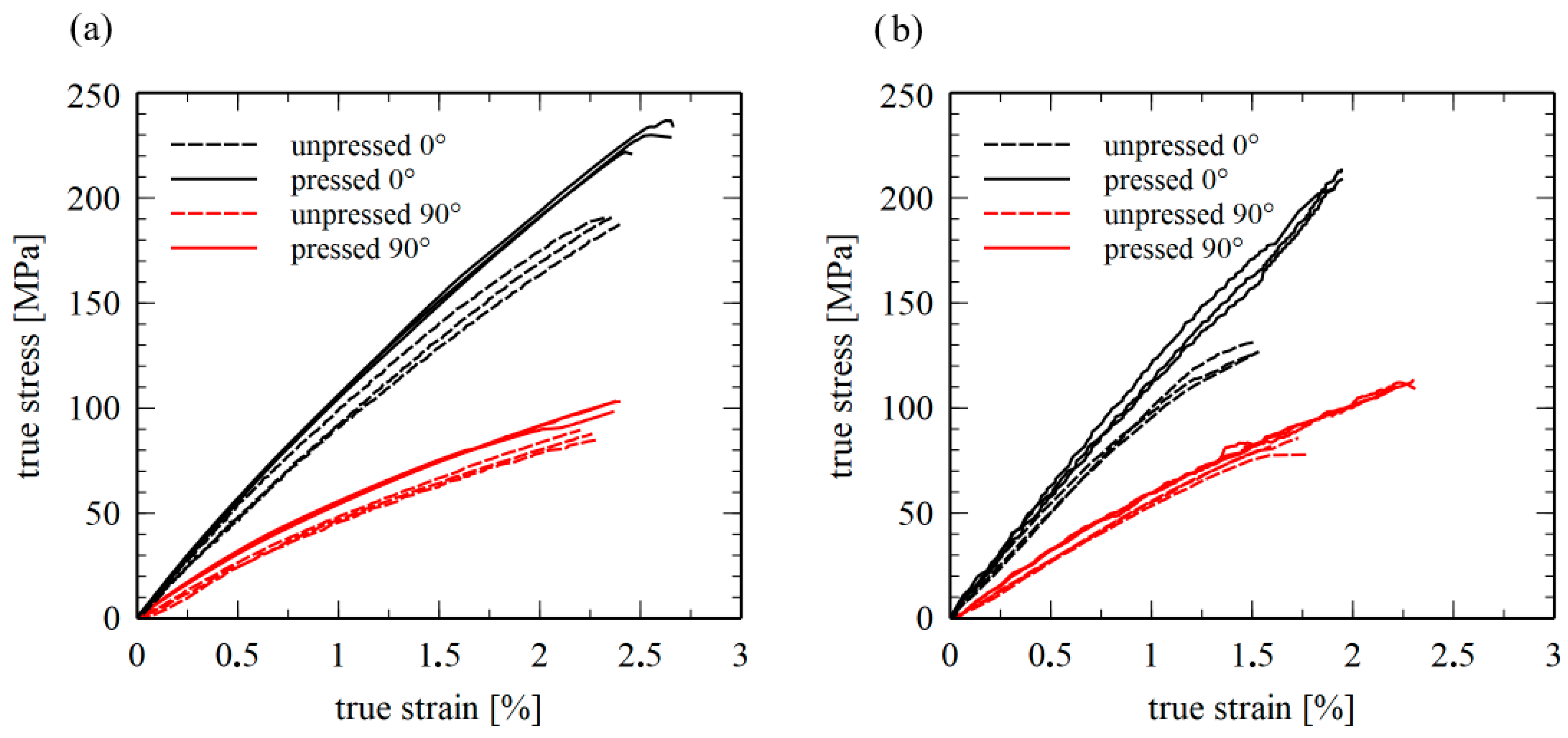

3. Material Test Results for CMS Development

4. Design of the Hybrid Crash Box of the CMS

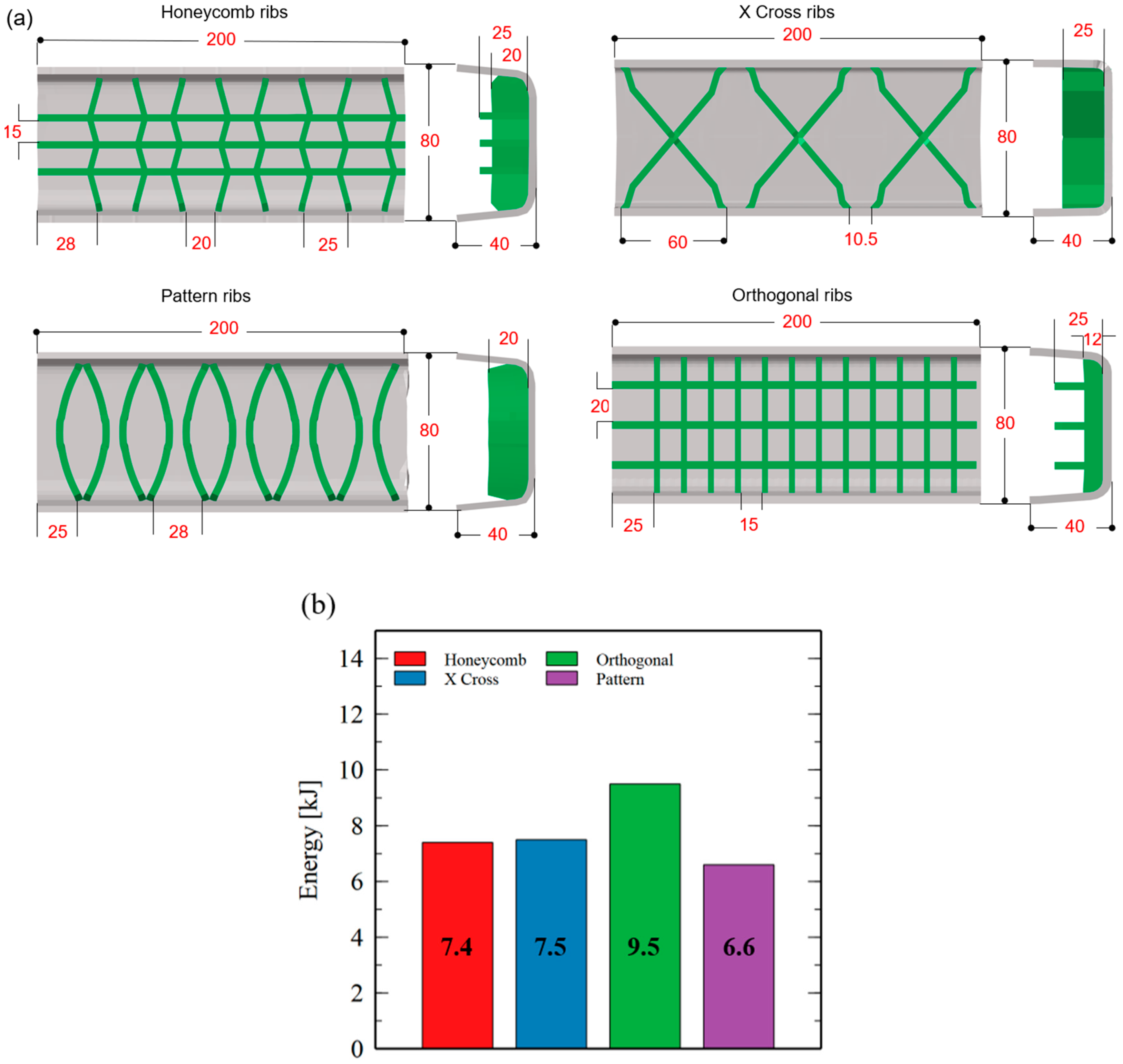

4.1. Crash Box Design and Optimization

4.2. Crash Box Manufacturing and Evaluation

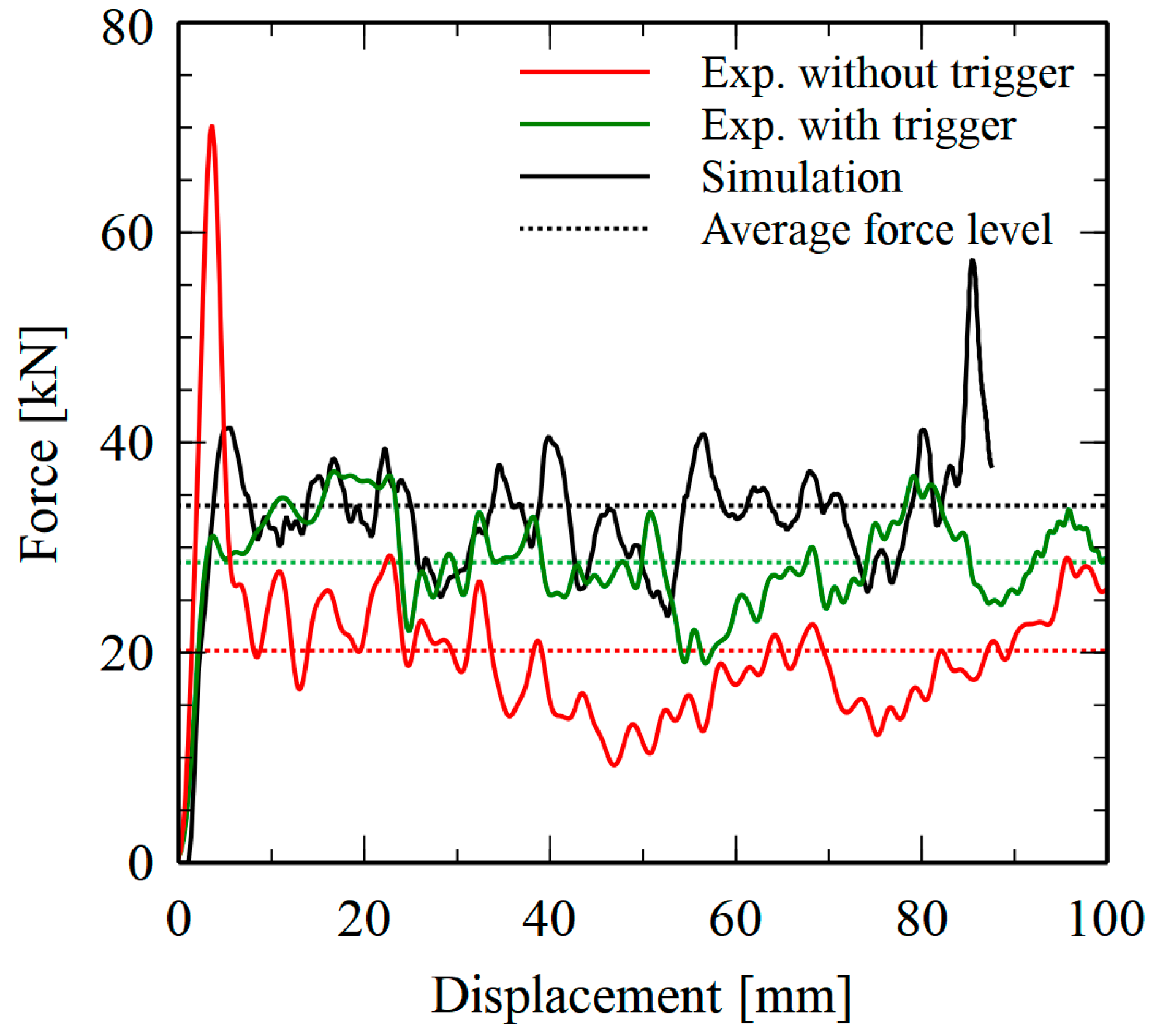

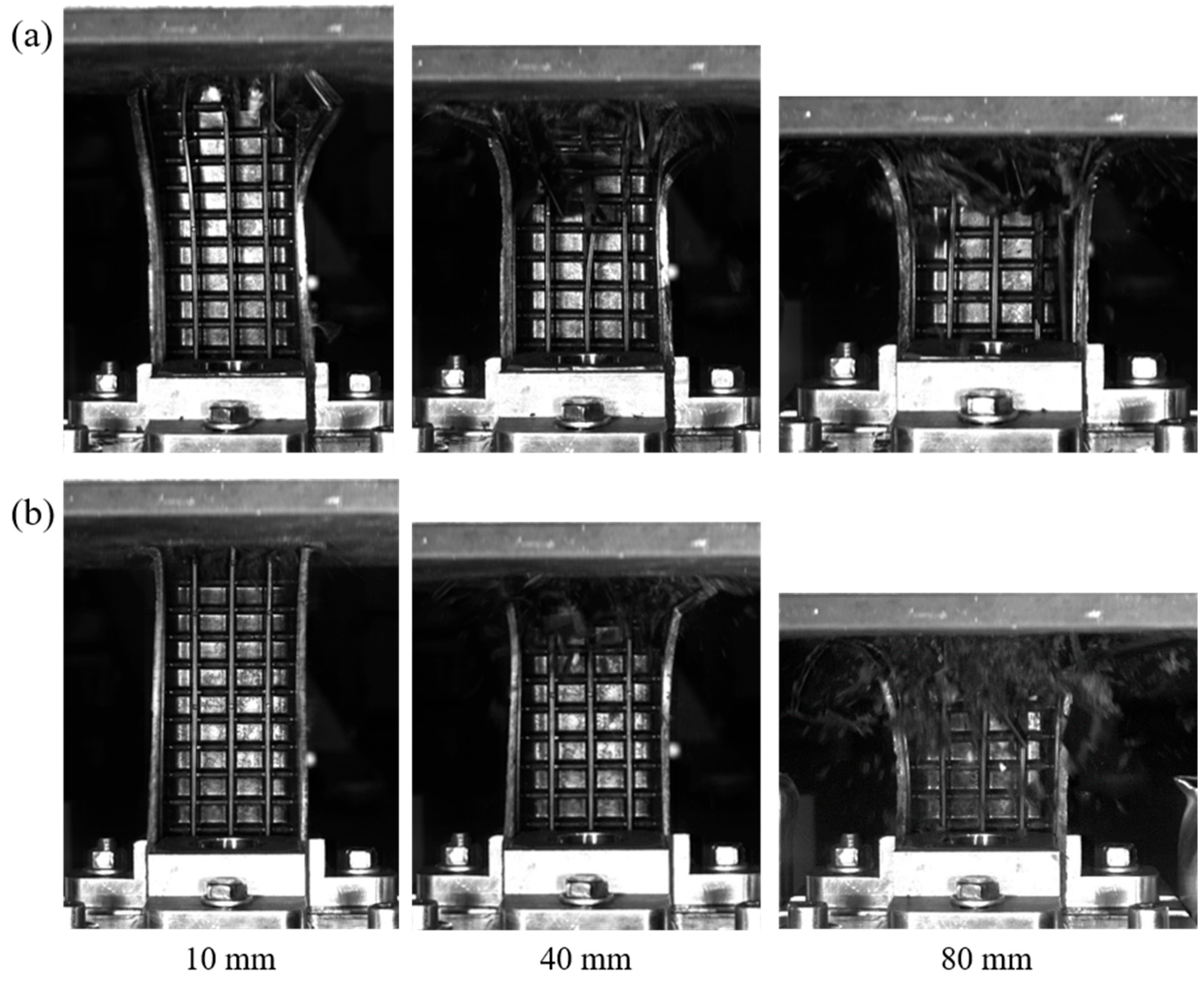

4.3. Dynamic Drop Tower Test

4.4. Intermediate Conclusions on Crash Box Development

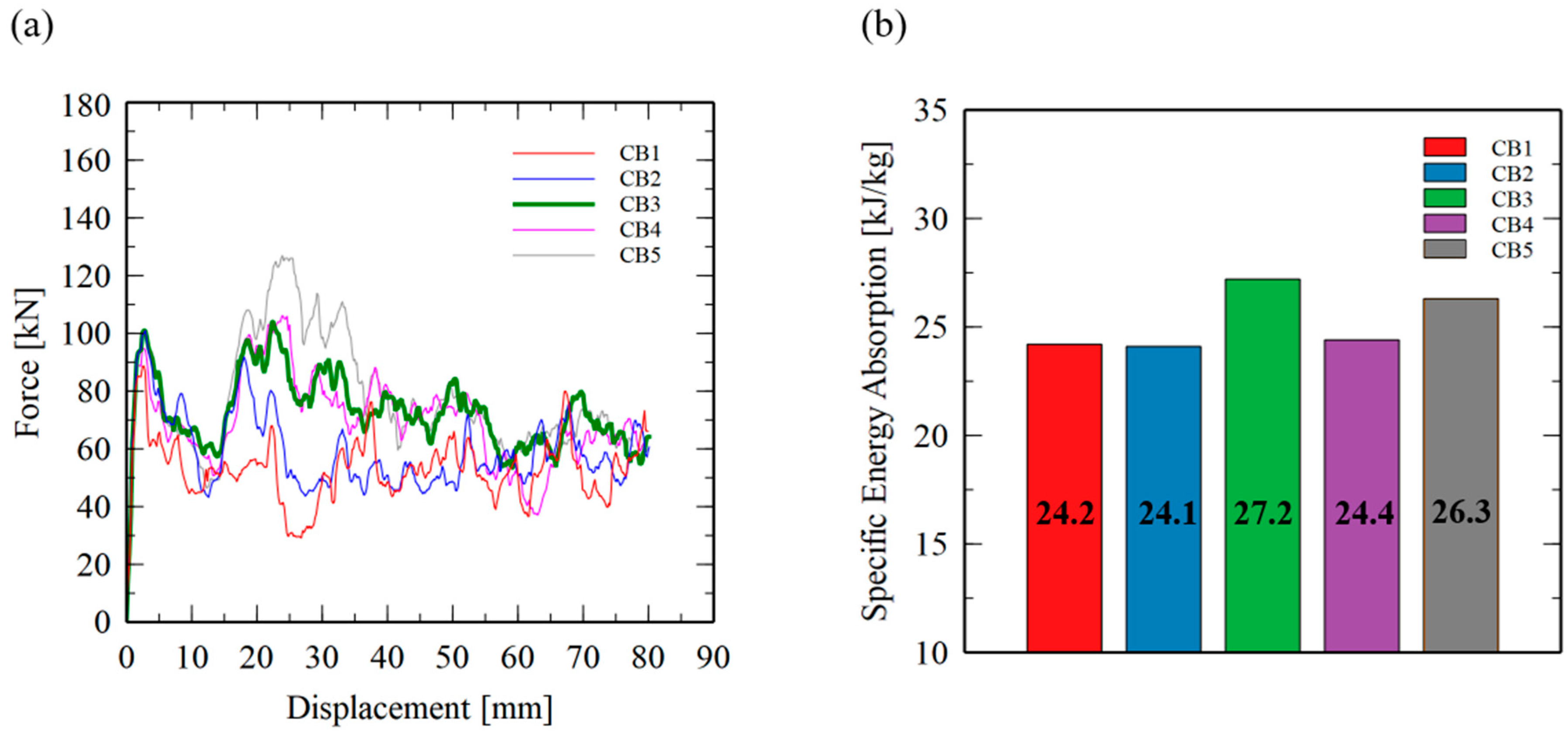

- 1.

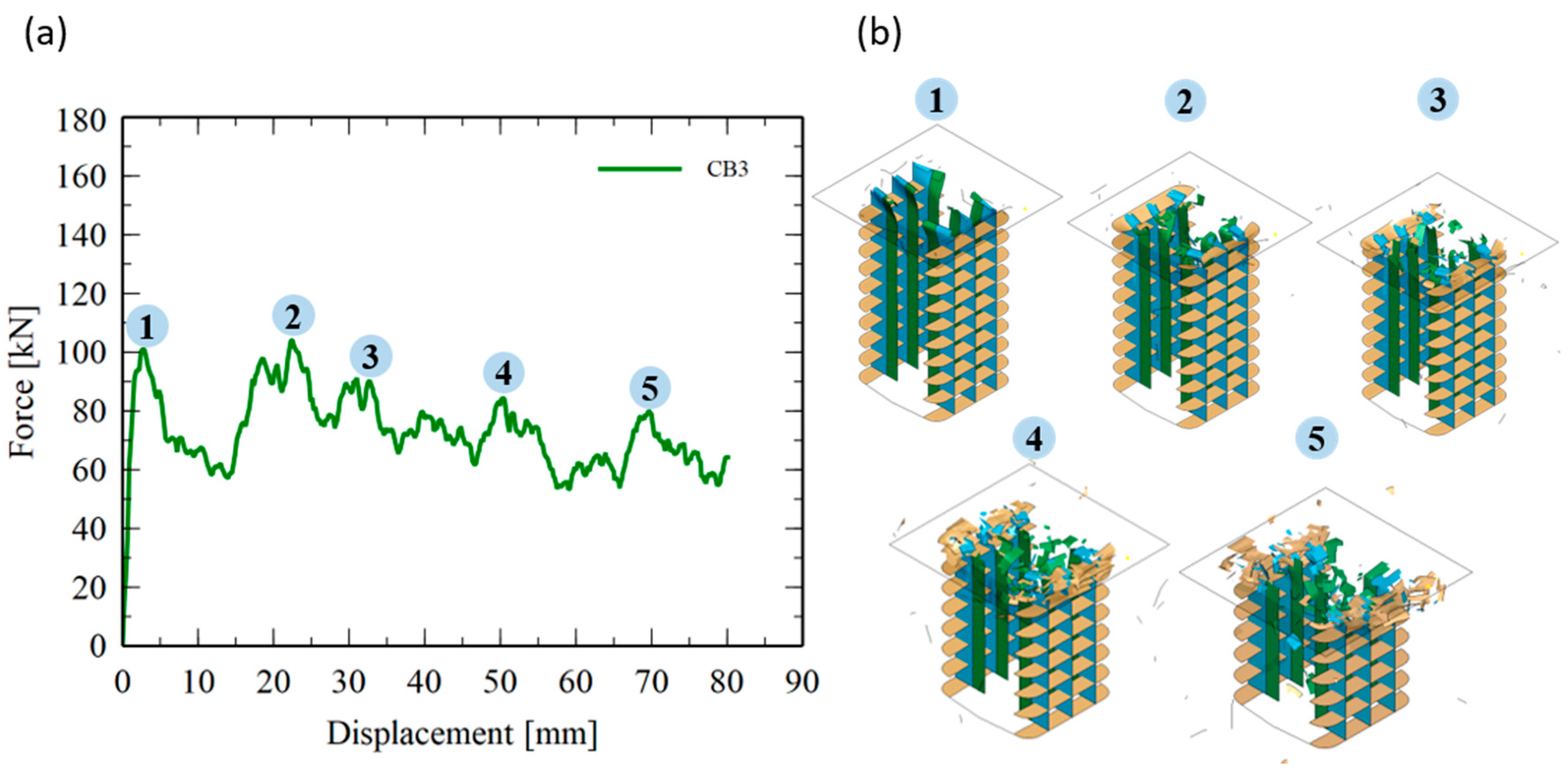

- Rib structure optimization: The orthogonal rib configuration (CB3) demonstrated the most favorable balance of high specific energy absorption (SEA) and homogeneous force–displacement behavior, making it the optimal pure GMTex reference design.

- 2.

- Behavior of pure GMTex crash boxes: Pure GMTex crash boxes exhibited highly progressive crushing behavior with low force fluctuations when an appropriate trigger was applied. Their SEA values exceeded those of conventional metallic crash boxes; however, fragmentation and material ejection were observed, which limits their direct applicability in automotive crash structures.

- 3.

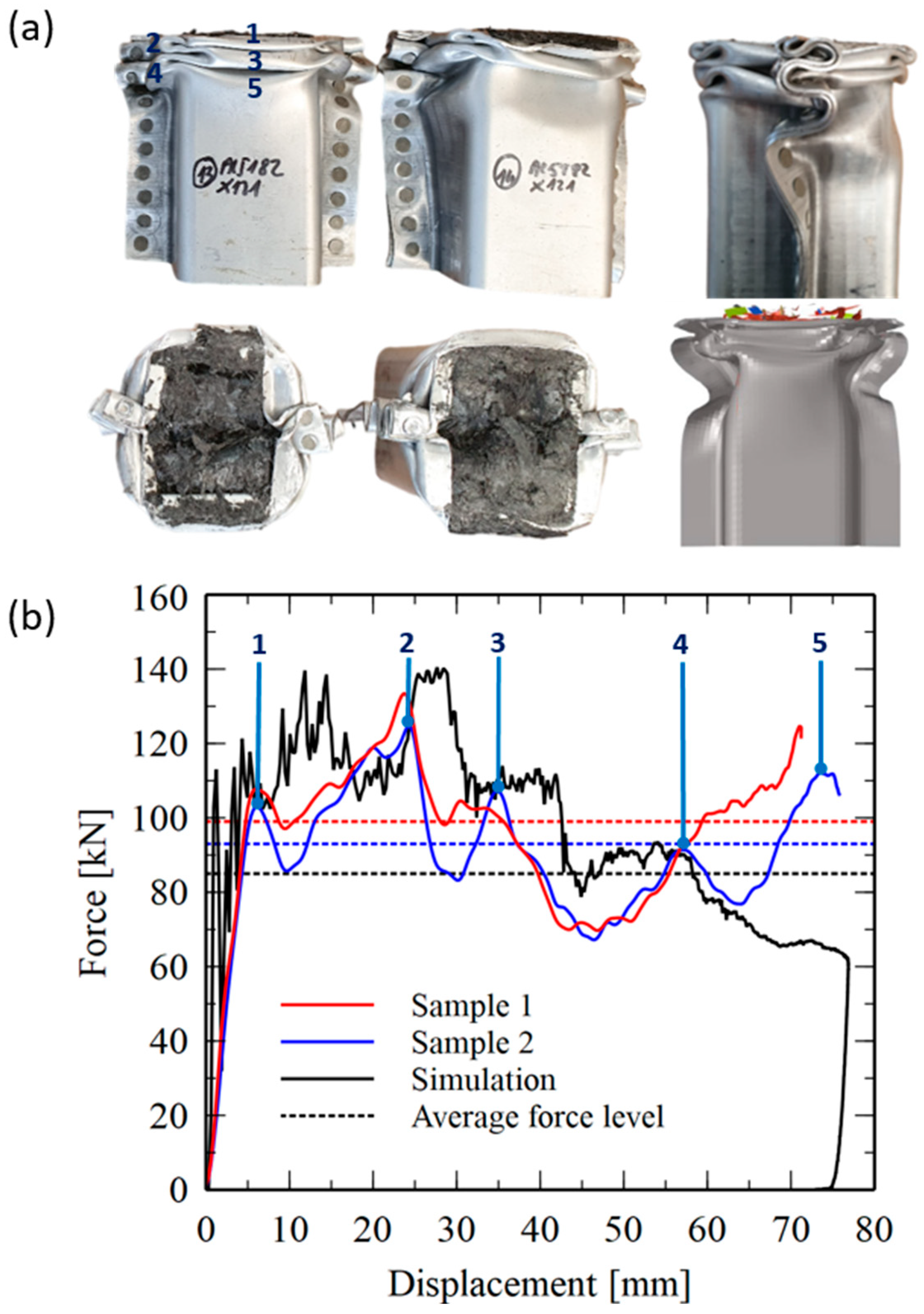

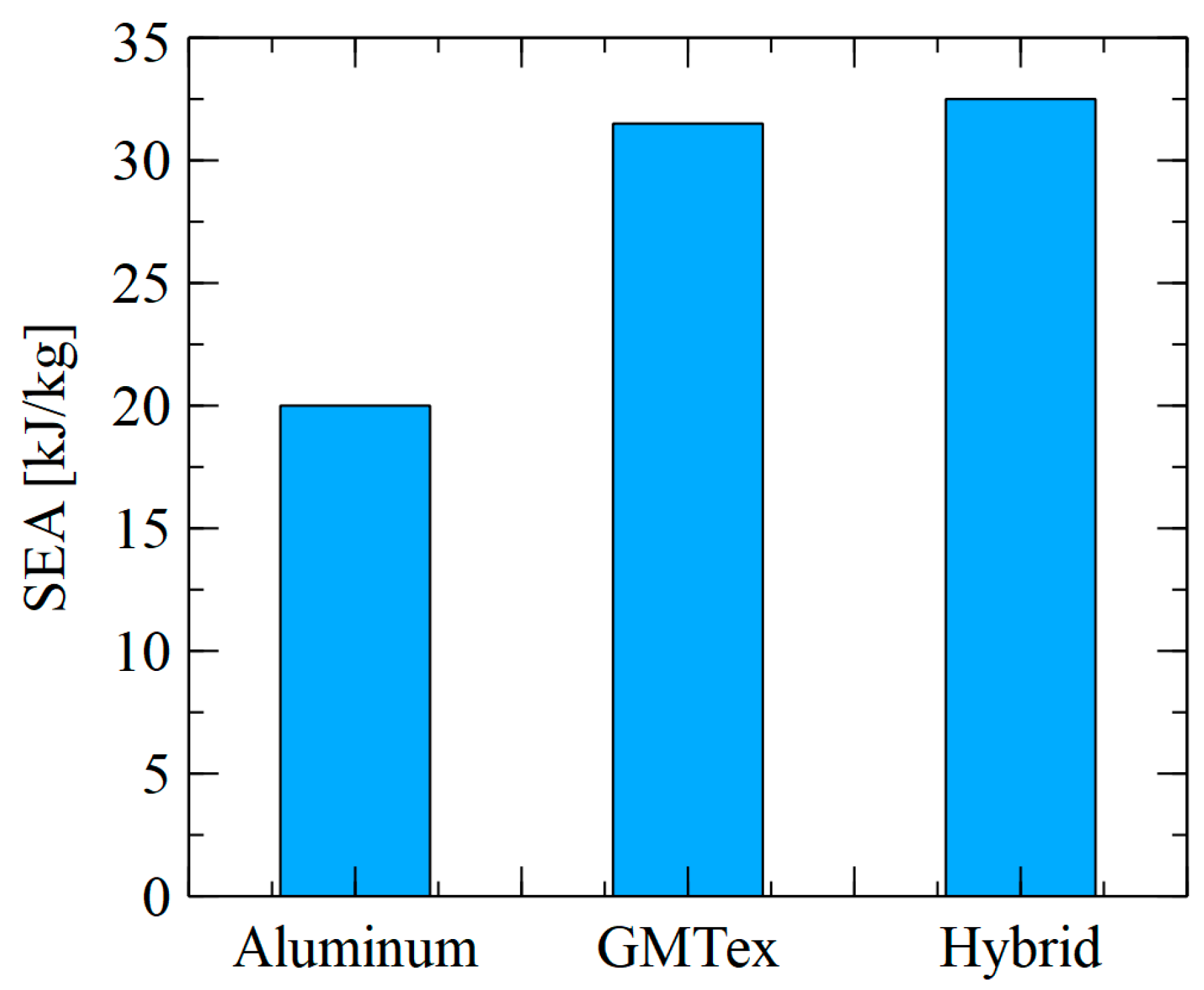

- Behavior of hybrid aluminum–GMTex crash box: The hybrid crash boxes achieved SEA values slightly higher than pure GMTex, as shown in Figure 21, and offered significantly greater deformation stability. The aluminum shell confined the GMTex fragments, ensured controlled folding, and prevented debris from escaping the profile. This improves functional robustness and makes the hybrid design more practical for real vehicle integration.

- 4.

- Simulation-Experiment agreement: The finite element simulations reproduced the folding sequence, load levels, and energy absorption characteristics with good consistency, confirming the suitability of the calibrated material and cohesive-zone models.

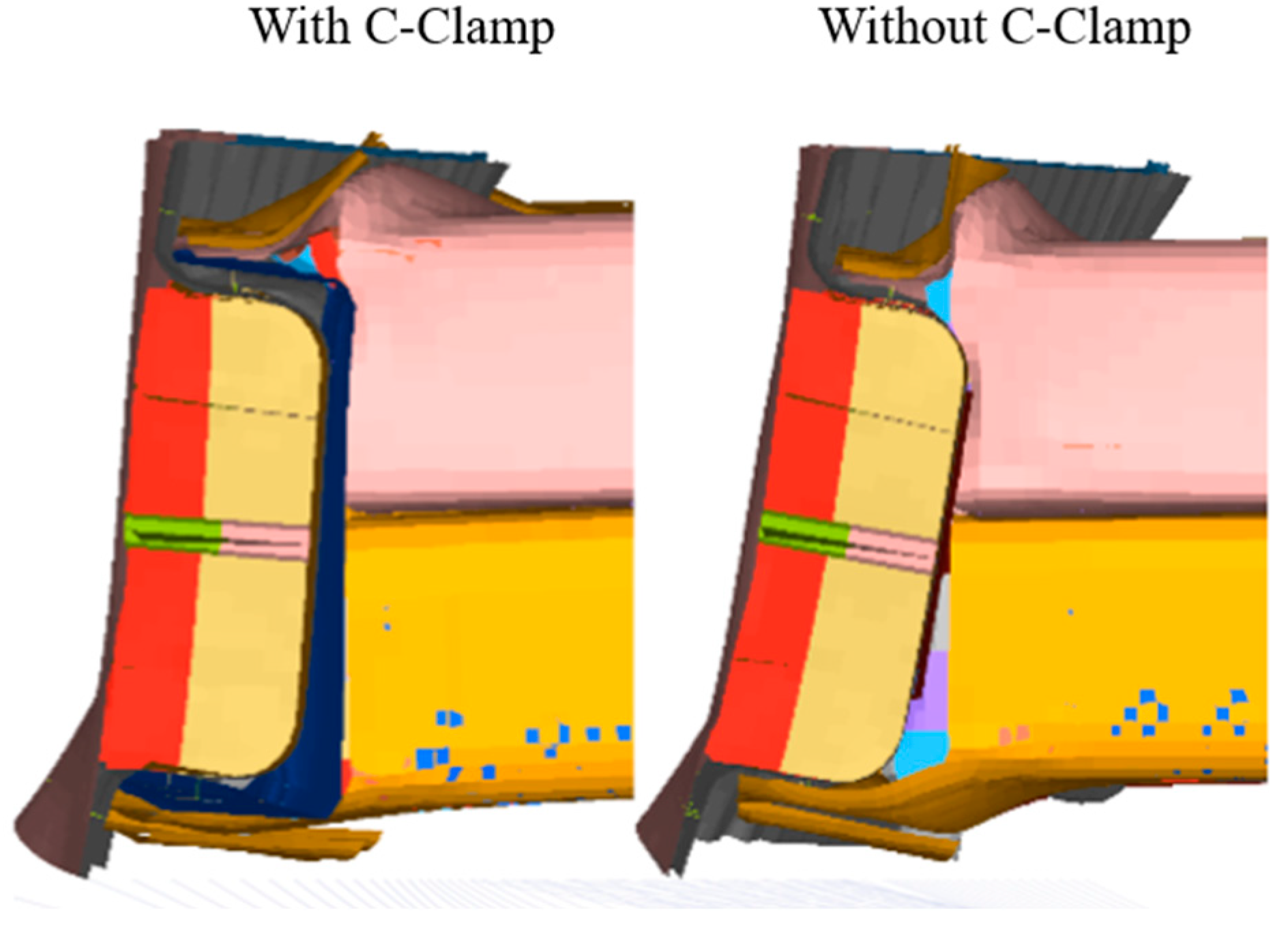

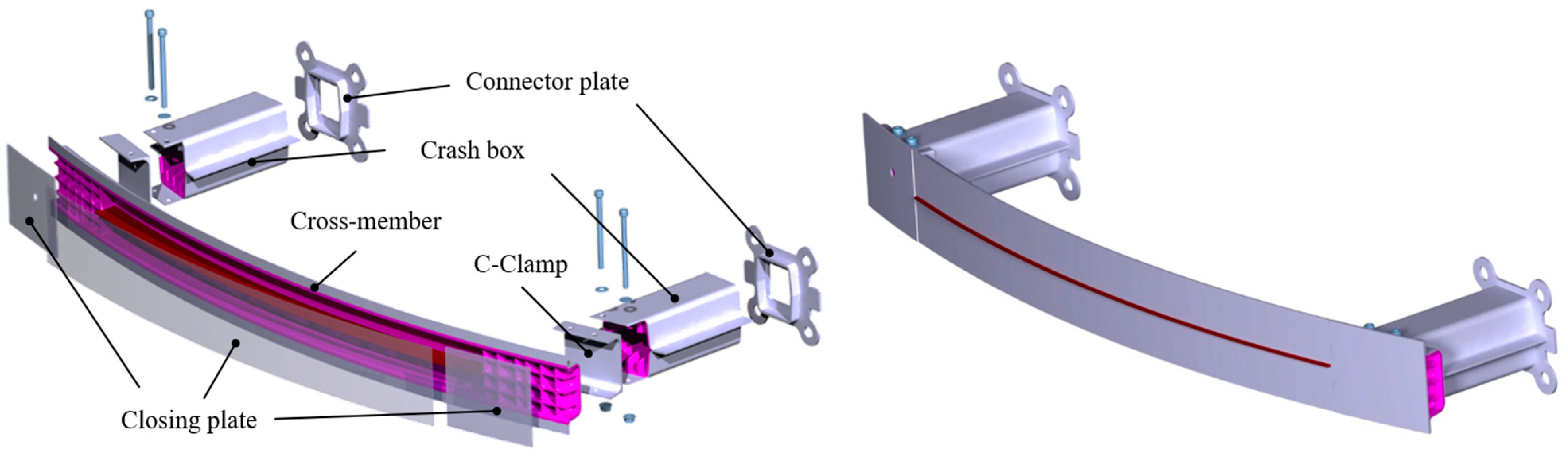

5. Design and Optimization of Al–GMT Hybrid CMS

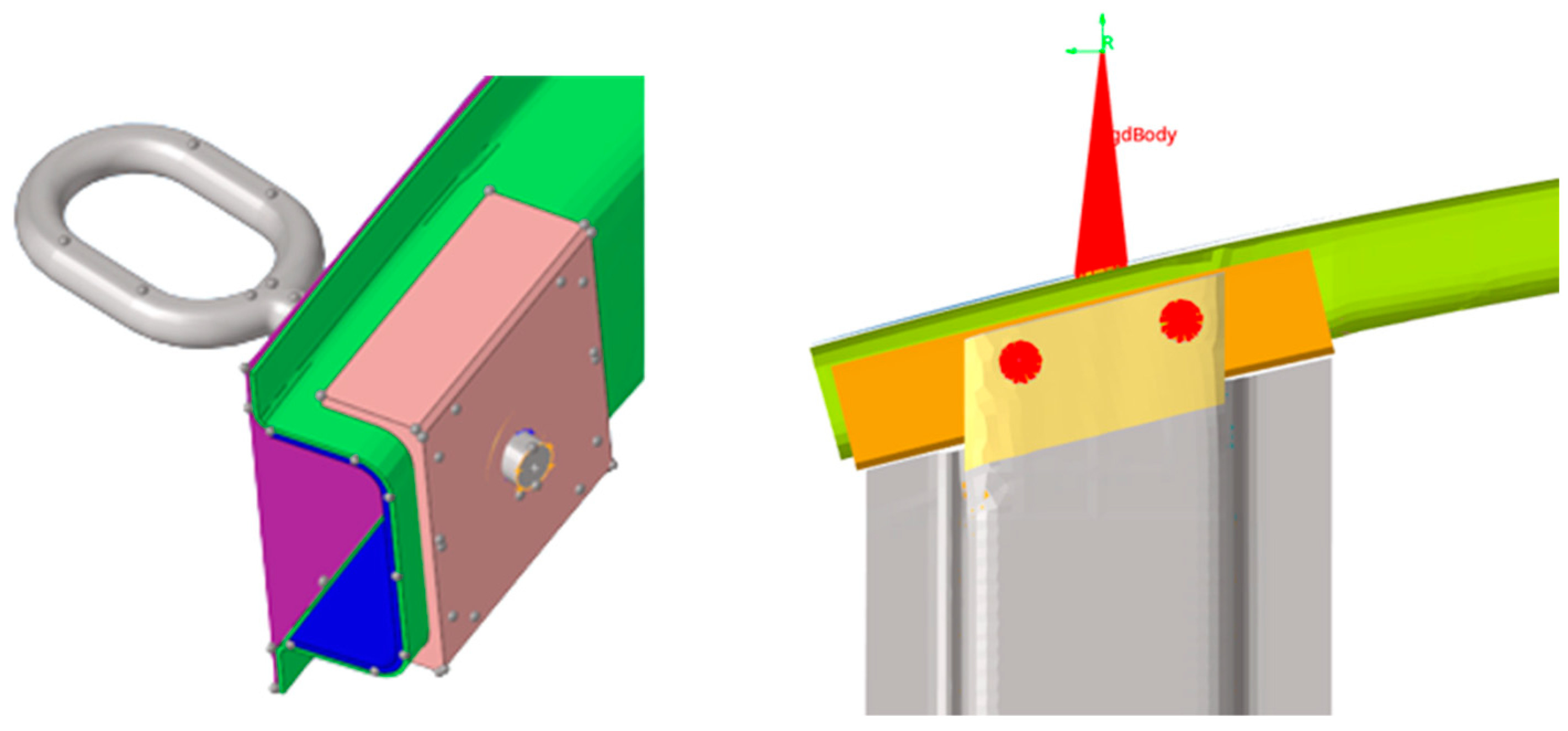

5.1. Design of the Crash Box as Part of CMS

5.2. Design of the Cross-Member as Part of CMS

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The mechanical properties of GMTex material are significantly influenced by the number of stacked plies and the woven fabric’s orientation. GMTex pressed in two plies shows higher tensile and compressive strengths of 240 MPa and 210 MPa, respectively, compared to 190 MPa and 130 MPa for unpressed GMTex. GMTex in the longitudinal direction of compression molding flow direction exhibits higher tensile and compressive strength compared to the transverse direction.

- (2)

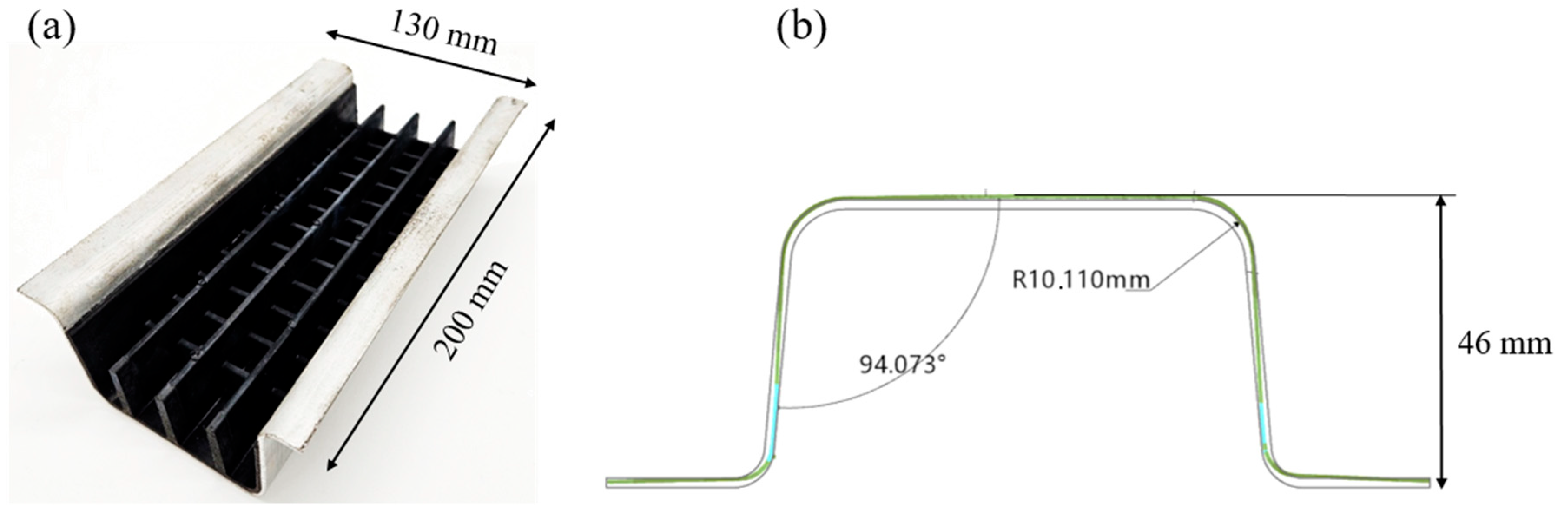

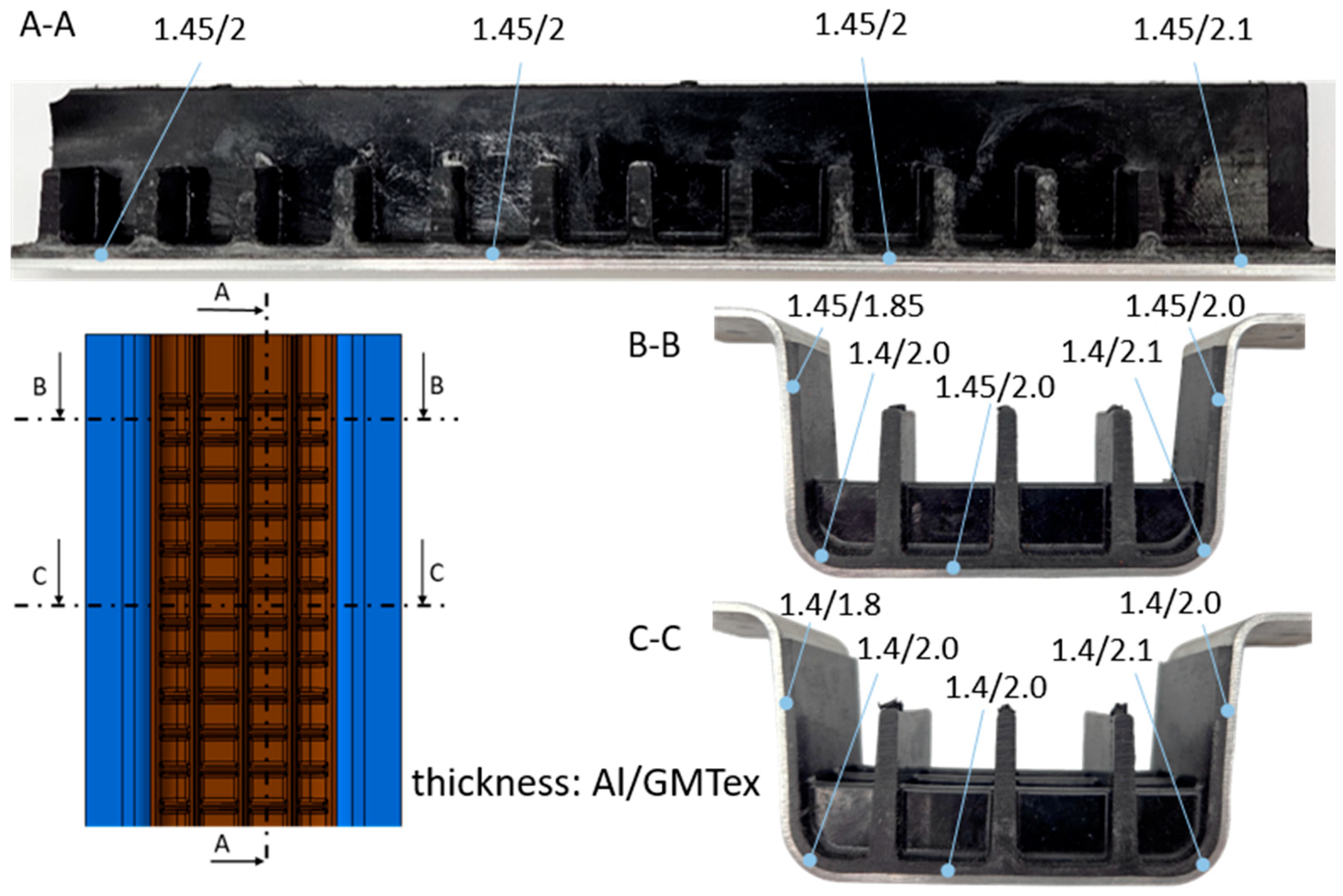

- Using the predeveloped tooling concept, both pure GMTex and an Al–GMT hybrid crash box could be successfully hybrid-formed. The GMTex thickness distribution was homogeneous and thus can be considered satisfactory. However, the fiber filling of GMTex in thin ribs was limited, restricting the design freedom of GMTex.

- (3)

- During axial loading in drop tower tests, pure GMTex crash boxes can enable continuous and progressive failure under axial impact loading through GMTex matrix and fiber failure as well as delamination. The deformation and failure behavior of the hybrid crash box is a superposition of both GMTex and Al materials, which is the folding of Al and crushing of GMTex.

- (4)

- The orthogonal rib configuration (CB3) demonstrated the most favorable balance of high specific energy absorption (SEA) and homogeneous force–displacement behavior. The pure GMTex crash box with this kind of optimized structure shows an SEA value of 31.4 kJ/kg, compared to ca. 20 kJ/kg for pure aluminum. The Al–GMTex hybrid has a SAE of 32.5 kJ/kg, which is only 3% higher than pure GMTex. However, it prevents any splits of the GMTex materials from escaping the Al profile.

- (5)

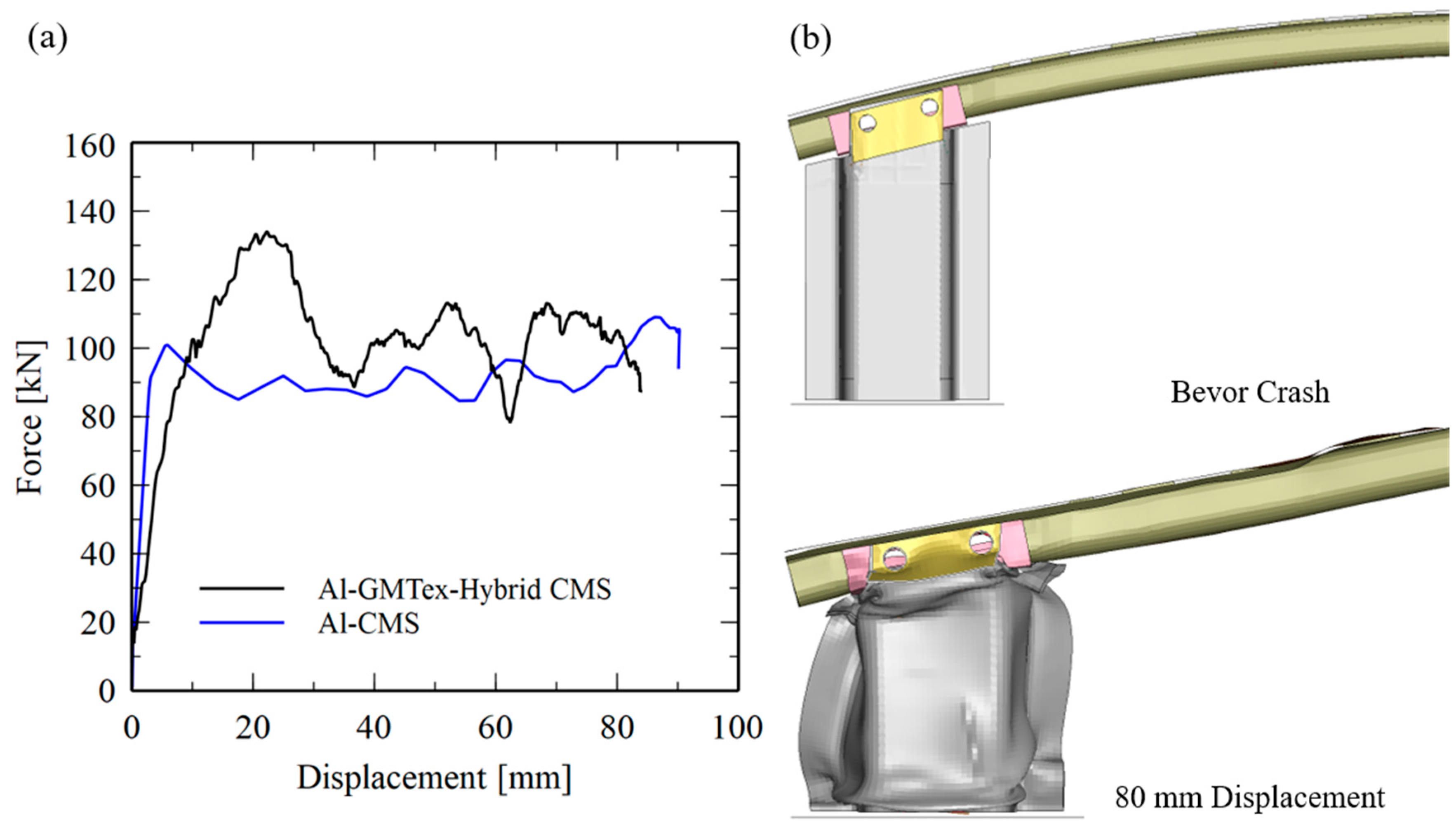

- An Al–GMTex hybrid CMS was developed within the current limitations of weldability of the hybrid parts. Without welding limitations, a weight reduction was achieved, however, with consideration of the weldability, the hybrid Al–GMTex CMS was equal to the reference CMS.

- (6)

- The hybrid CMS shows approx. 10% less intrusion and 10% higher mean force level. This could be considered additional weight-saving potential that could not be utilized during this work due to the limitations of minimum aluminum and GMTex rib thicknesses.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jambor, A.; Beyer, M. New cars—New materials. Mater. Des. 1997, 18, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisagni, C.; Di Pietro, G.; Fraschini, L.; Terletti, D. Progressive crushing of fiber-reinforced composite structural components of a Formula One racing car. Compos. Struct. 2005, 68, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.F. Karosserieentwicklung und-Leichtbau: Eine Ganzheitliche Betrachtung von Design über Konzept- und Materialauswahlprinzipien bis zur Auslegung und Fertigung; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenstein, G.W. (Ed.) Handbuch Kunststoff-Verbindungstechnik; Hanser: München, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Messler, R.W. Trends in key joining technologies for the twenty-first century. Assem. Autom. 2000, 20, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Sugiyama, S.; Yanagimoto, J. Applicability of adhesive–embossing hybrid joining process to glass-fiber-reinforced plastic and metallic thin sheets. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2014, 214, 2018–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambiase, F.; Di Ilio, A. Mechanical clinching of metal–polymer joints. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2015, 215, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallmeister, T.; Tröster, T. In-Mold-Assembly of Hybrid Bending Structures by Compression Molding. Key Eng. Mater. 2022, 926, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lauter, C.; Sanitther, B.; Camberg, A.; Troester, T. Manufacturing and investigation of steel-CFRP hybrid pillar structures for automotive applications by intrinsic resin transfer moulding technology. Int. J. Automot. Compos. 2016, 2, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simacek, P.; Advani, S.G.; Iobst, S.A. Modeling Flow in Compression Resin Transfer Molding for Manufacturing of Complex Lightweight High-Performance Automotive Parts. J. Compos. Mater. 2008, 42, 2523–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, R.; Kobayashi, S.; Todoroki, A.; Mizutani, Y. Full-field monitoring of resin flow using an area-sensor array in a VaRTM process. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2011, 42, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.M.; Rauscher, B.; Tekkaya, A.E. Wirkmedienbasierte Herstellung hybrider Metall-Kunststoff-Verbundbauteile mit Kunststoffschmelzen als Druckmedium. Mater. Werkst. 2008, 39, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossel, W.-G.; Lies, C.; Albert, A.; Haase, R.; Müller, R.; Scholz, P. Process combinations for the manufacturing of metal-plastic hybrid parts. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 118, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgrebe, D.; Kräusel, V.; Rautenstrauch, A.; Albert, A.; Wertheim, R. Energy-efficiency in a Hybrid Process of Sheet Metal Forming and Polymer Injection Moulding. Procedia CIRP 2016, 40, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehmeyer, R. Herstellung von Kunststoff/Metall-Bauteilen Mit Integrierter Umformung im Spritzgießprozess: Production of Plastic/Metal-Hybrid Parts with Integrated Forming in the Injection Moulding Process; Günter Mainz Verlag: Aachen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hopmann, C.; Schild, J.; Wurzbacher, S.; Tekkaya, A.E.; Hess, S. Combination technology of deep drawing and back-moulding for plastic/metal hybrid components. J. Polym. Eng. 2018, 38, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S. Effects of fiber length and fiber orientation distributions on the tensile strength of short-fiber-reinforced polymers. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1996, 56, 1179–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Gandhi, U.; Sekito, T.; Vaidya, U.K.; Hsu, J.; Yang, A.; Osswald, T. A Novel CAE Method for Compression Molding Simulation of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composite Sheet Materials. J. Compos. Sci. 2018, 2, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Gandhi, U.; Pérez, C.; Osswald, T.; Vallury, S.; Yang, A. Method to account for the fiber orientation of the initial charge on the fiber orientation of finished part in compression molding simulation. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 100, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemme, M. LFT—Development status and perspectives. Plast. Addit. Compd. 2008, 10, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.F.; Kloska, T. Hybrid forming of sheet metals with long Fiber-reinforced thermoplastics (LFT) by a combined deep drawing and compression molding process. Int. J. Mater. Form. 2020, 13, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.F.; Kloska, T.; Hajdarevic, A. Die Concepts and formability for simultaneous forming of sheet metals and FRPs. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1238, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloska, T.; Fang, X.F. Lightweight Chassis Components—The Development of a Hybrid Automotive Control Arm from Design to Manufacture. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2021, 22, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belingardi, G.; Beyene, A.T.; Koricho, E.G.; Martorana, B. Alternative lightweight materials and component manufacturing technologies for vehicle frontal bumper beam. Compos. Struct. 2015, 120, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, A.R.M.; Ahmadian, M.T. Design and Analysis of an Automobile Bumper with the Capacity of Energy Release Using GMT Materials. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. Int. J. Mech. Aerosp. Ind. Mechatron. Manuf. Eng. 2011, 5, 865–872. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Lin, Z.; Jiang, A.; Chen, G. Experimental study of glass-fiber mat thermoplastic material impact properties and lightweight automobile body analysis. Mater. Des. 2004, 25, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belingardi, G.; Beyene, A.T.; Jichuan, D. Energy absorbing capability of GMT, GMTex and GMT-UD composite panels for static and dynamic loading—Experimental and numerical study. Compos. Struct. 2016, 143, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Chen, D.; Zhu, G.; Li, Q. Lightweight hybrid materials and structures for energy absorption: A state-of-the-art review and outlook. Thin-Walled Struct. 2022, 172, 108760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Pang, T.; Zhang, B.; Fang, J.; Li, Q.; Sun, G. On the crashworthiness of thin-walled multi-cell structures and materials: State of the art and prospects. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 189, 110734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, C.; Tröster, T. Crashworthiness and numerical simulation of hybrid aluminium-CFRP tubes under axial impact. Thin-Walled Struct. 2017, 117, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Shen, C.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, T. Study on energy absorption performance of variable thickness CFRP/aluminum hybrid square tubes under axial loading. Compos. Struct. 2021, 276, 114469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, M.; Mahbod, M.; Asgari, M. Topology-optimized hybrid solid-lattice structures for efficient mechanical performance. Structures 2021, 29, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qiu, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xia, L. A multi-material topology optimization approach to hybrid material structures with gradient lattices. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 425, 116969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, A.; Ghasemnejad, H. Finite Element Modelling Approach for Progressive Crushing of Composite Tubular Absorbers in LS-DYNA: Review and Findings. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Morris, Z.; Teoli, M.; Tameer, D.; Kim, I.Y. Stress-Constrained Multi-Material Topology Optimization. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Prac. Mobil. 2025, 7, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörmann, M.; Wacker, M. Simulation of the Crash Performance of Crash Boxes based on Advanced Thermoplastic Composite. In Proceedings of the 5th European LS-DYNA User Conference, Birmingham, UK, 25–26 May 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Feraboli, P.; Wade, B.; Deleo, F.; Rassaian, M.; Higgins, M.; Byar, A. LS-DYNA MAT54 modeling of the axial crushing of a composite tape sinusoidal specimen. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2011, 42, 1809–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, S.; Hajdarevic, A.; Anand, S.; Fang, X.F. Experimental and FE analyses of the crushing and bending behaviors of GMT and hybrid-formed Al-GMT structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 186, 110648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartlen, D.C.; Montesano, J.; Cronin, D.S. Cohesive Zonen Modeling of Adhesively Bonded Interfaces: The Effect of a Adherend Geometry, Element Selection, and Loading Condition. In Proceedings of the 16th International LS-DYNA® Users Conference, Virtual, 10–11 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- DIN EN ISO 6892-1; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature (ISO 6892-1:2019). DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2019.

- DIN EN ISO 527-4; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 4: Test Conditions for Isotropic and Orthotropic Fibre-Reinforced Plastic Composites (ISO 527-4:2023). DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2019.

- ASTM D 6641/D 6641M; Standard Test Method for Compressive Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials Using a Combined Loading Compression (CLC) Test Fixture. American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM): West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- DIN EN 1465; Adhesives—Determination of Tensile Lap-Shear Strength of Bonded Assemblies. DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2009.

- Kloska, T. Leichtbaupotenziale im Fahrwerk—Multi-Material-Design Durch Simultane Umformung von Metallblechen und Urformung von Langfaserverstärkten Thermoplasten (LFT); Universitätsverlag Siegen: Siegen, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar, S.; Anand, S.; Fang, X. Design Optimization and Validation of GMT Hat Structures. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on the Technology of Plasticity—Current Trends in the Technology of Plasticity, Mandelieu-La Napoule, France, 24–29 September 2023; Mocellin, K., Bouchard, P.-O., Bigot, R., Balan, T., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.T.W.; Said, M.R.; Yaakob, M.Y. On the effect of geometrical designs and failure modes in composite axial crushing: A literature review. Compos. Struct. 2012, 94, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striewe, J.; Reuter, C.; Sauerland, K.-H.; Tröster, T. Manufacturing and crashworthiness of fabric-reinforced thermoplastic composites. Thin-Walled Struct. 2018, 123, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, B.; Deleo, F.; Feraboli, P.; Rassaian, M. Crushing of Composite Structures: Experiment and Simulation. In Proceedings of the 50th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, Palm Springs, CA, USA, 4–7 May 2009; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Palm Springs, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Wang, Q.; Ke, S. Energy absorption characteristics of thin-walled steel tube filled with paper scraps. BioResources 2021, 16, 5985–6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocke, F.; Schreiner, T.; Schüler, M.; Zeis, M. Material Removal Simulation for Abrasive Water Jet Milling. Procedia CIRP 2018, 68, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüler, M.; Heidrich, D.; Herrig, T.; Fang, X.F.; Bergs, T. Automotive hybrid design production and effective end machining by novel abrasive waterjet technique. Procedia CIRP 2021, 101, 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wickert Press WKP 2000 S | Value |

|---|---|

| Parameter | |

| Pressing force [kN] | 600 |

| Die velocity [mm/s] | 5 |

| Holding time [s] | 30 |

| Tool temperature [°C] | 80 |

| Material | Temperature [°C] | Rp0.2 [MPa] | Rm [MPa] | A15 [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al crash box | RT | 110 | 230 | 17 |

| Al cross-member | RT | 160 | 350 | 18 |

| Material | Temperature [°C] | Rp0.2 [MPa] | Rm [MPa] | A15 [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA5182 H111/O | RT | 132.3 ± 0.4 | 284.4 ± 0.5 | 30 ± 0.6 |

| AA6451 T4 | RT | 161.5 ± 3.1 | 281.6 ± 2.0 | 30.9 ± 0.3 |

| GFRP | Max. Tensile Stress [MPa] | Tensile Modulus [MPa] | Max. Tensile Strain [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| PP GMT 40% GF | 85 | 6100 | 1.95 |

| PP GMTex 40% GF | 235 | 11,200 | 2.6 |

| PP GMTex 60% GF | 380 | 18,600 | 2.3 |

| PA6 LFT 40% GF | 160 | 10,600 | 2.5 |

| PP LFT 40% GF | 100 | 9100 | 2 |

| Parameter | Range of Values for Parameter [mm] |

|---|---|

| Transversal rib height (TH) | 5–12–15 |

| Transversal rib thickness (TT) | 2.5–3.5–4 |

| Transversal rib distance (TD) | 15–20–25–30 |

| Longitudinal rib height (LH) | 30 |

| Longitudinal rib thickness (LT) | 3.5–4–4.5 |

| Longitudinal rib distance (LD) | 20 |

| TH [mm] | TT [mm] | TD [mm] | LH [mm] | LT [mm] | LD [mm] | Mean Force Level [kN] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB1 | 5 | 2.5 | 15 | 30 | 3.5 | 20 | 52.8 |

| CB2 | 5 | 3.5 | 15 | 30 | 3.5 | 20 | 58.8 |

| CB3 | 12 | 3.5 | 15 | 30 | 4.5 | 20 | 72.2 |

| CB4 | 12 | 2.5 | 15 | 30 | 4.5 | 20 | 69 |

| CB5 | 15 | 3.5 | 15 | 30 | 4 | 20 | 76 |

| Parameter | Experiment with Trigger | Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Initial peak force [kN] | 29 ± 4 | 41 |

| Mean force level [kN] | 28.5 ± 0.7 | 33 |

| Max. intrusion [mm] | 104 ± 5 | 88 |

| SEA [kJ/kg] | 31.4 ± 0.2 | 32.3 |

| Parameter | Experiment | Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Initial peak force [kN] | 104 ± 4 | 113 |

| Mean force level [kN] | 96 ± 5 | 85 |

| Max. intrusion [mm] | 73.5 ± 3.1 | 77 |

| SEA [kJ/kg] | 32.5 ± 2.3 | 32 |

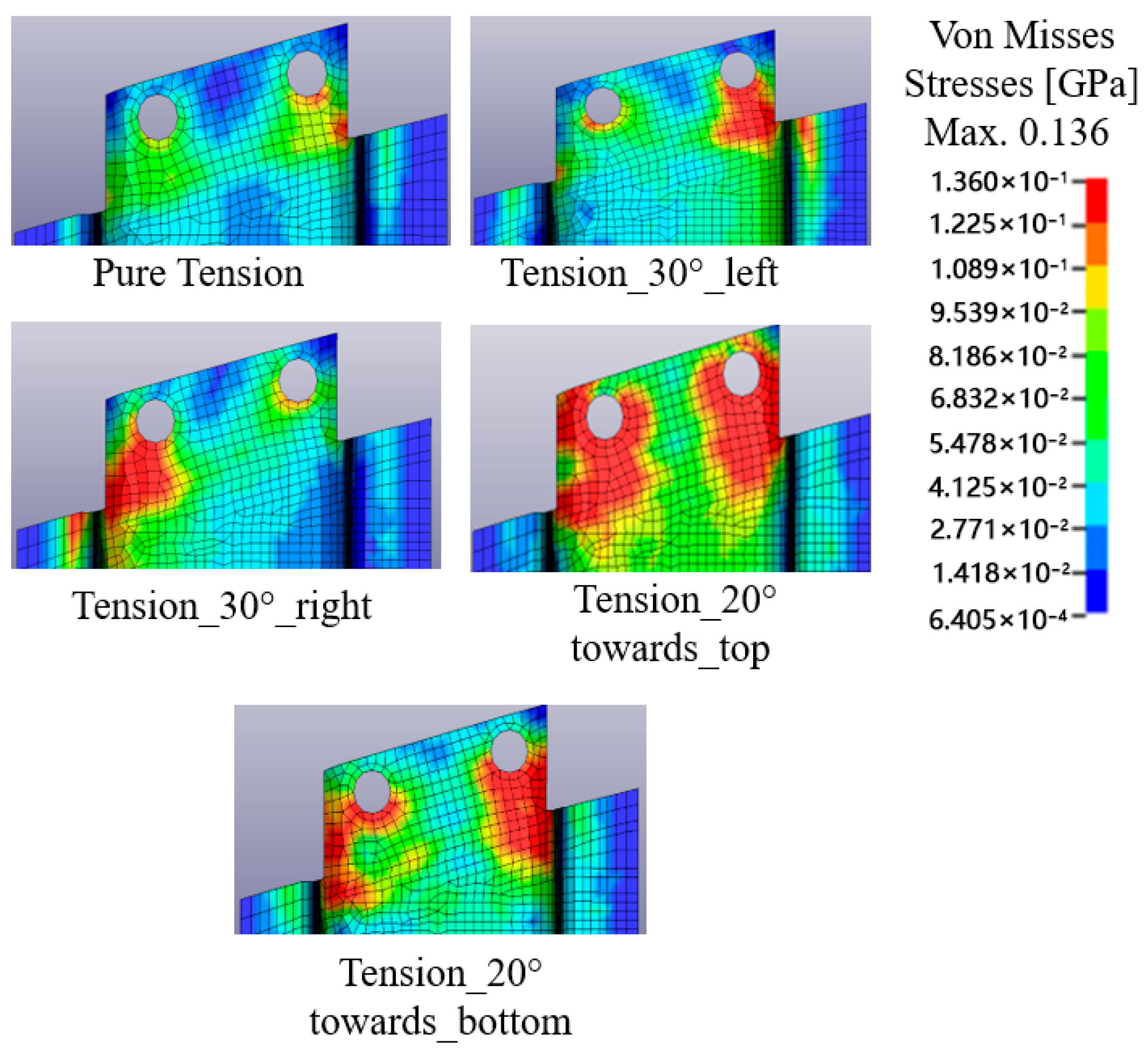

| Loading Angle [°] | Load [kN] |

|---|---|

| Pure tension | 13 |

| Tension 30°_to_left | 13 |

| Tension 30°_to_right | 13 |

| Tension 20°_towards_top | 13 |

| Tension 20°_towards_bottom | 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hajdarevic, A.; Fang, X.; Jayakumar, S.; Anand, S.C. Lightweight Aluminum–FRP Crash Management System Developed Using a Novel Hybrid Forming Technology. Vehicles 2026, 8, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles8010002

Hajdarevic A, Fang X, Jayakumar S, Anand SC. Lightweight Aluminum–FRP Crash Management System Developed Using a Novel Hybrid Forming Technology. Vehicles. 2026; 8(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles8010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleHajdarevic, Amir, Xiangfan Fang, Saarvesh Jayakumar, and Sharath Christy Anand. 2026. "Lightweight Aluminum–FRP Crash Management System Developed Using a Novel Hybrid Forming Technology" Vehicles 8, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles8010002

APA StyleHajdarevic, A., Fang, X., Jayakumar, S., & Anand, S. C. (2026). Lightweight Aluminum–FRP Crash Management System Developed Using a Novel Hybrid Forming Technology. Vehicles, 8(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles8010002