Adjoint Optimization for Hyperloop Aerodynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Gap-aware optimization: To our knowledge, the first adjoint optimization of a Hyperloop pod that explicitly targets gap-induced choking and wall–jet interactions in a full pod–tube model.

- Verified methodology: A mesh-verified RANS/GEKO framework (medium vs. fine deviation 0.59%) suitable for design studies at 10 kPa and M = 0.5–0.7.

- Headline results: 27.5% drag reduction, ~70% delay of choking onset, and critical gap lowered from d/D ≈ 0.025 to ≈0.008 for M = 0.7.

- Design rule-of-thumb: For transonic cruise at 10 kPa, standard pods must maintain a clearance-to-diameter ratio (d/D) above 0.025 to prevent choked flow. An optimized pod, however, remains stable down to a ratio of approximately 0.008. This lower limit is a practical design target, as it accommodates the millimeter-level gaps used in magnetic levitation systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Description and Computational Domain

2.2. Computational Grid

2.3. Boundary Conditions

2.4. Adjoint Design Optimization

2.5. Validation and Verification

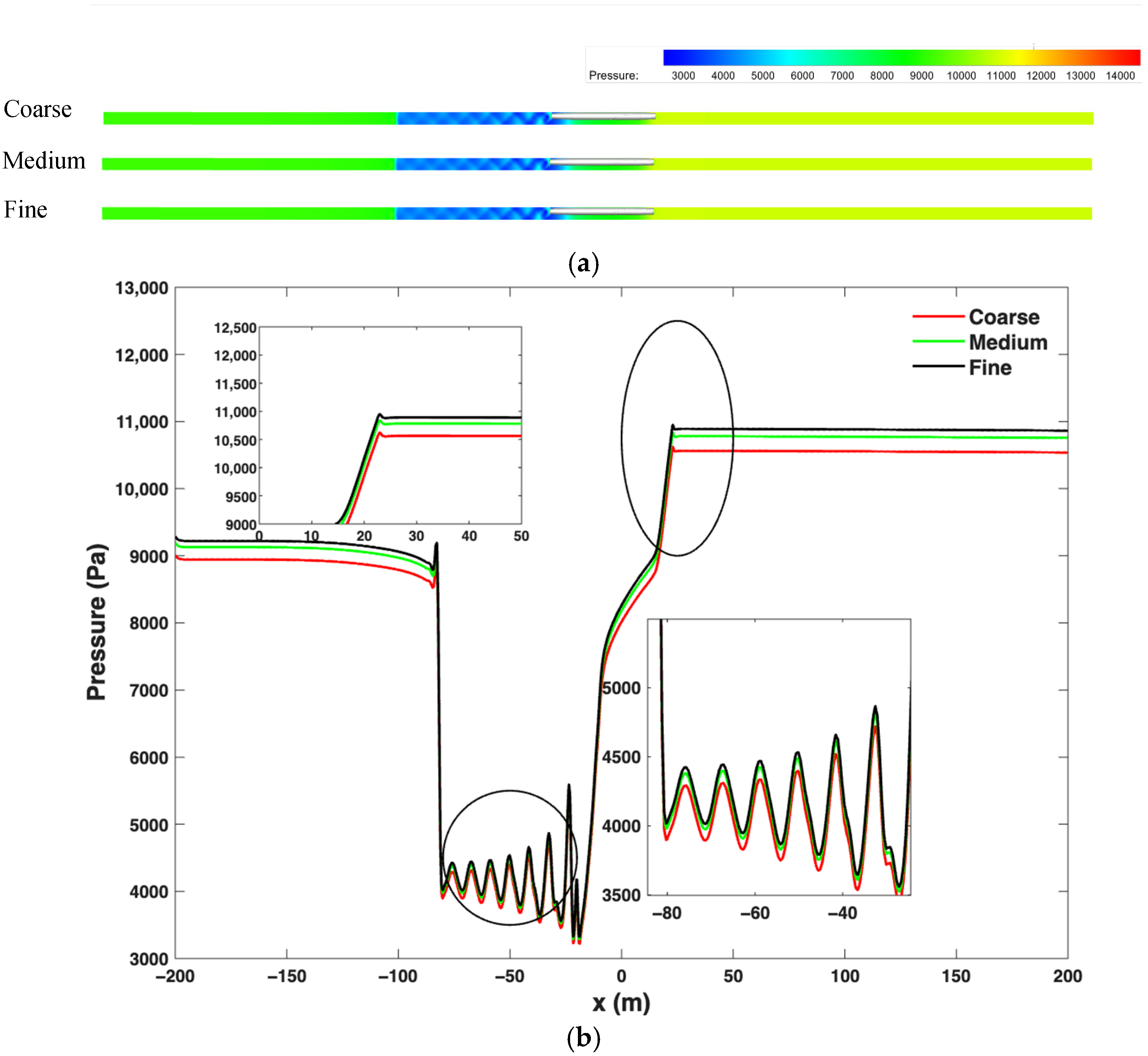

Grid Independence Study

2.6. Experimental Validation Model

3. Results

3.1. Aerodynamic Analysis of the Baseline Model with Various Suspension Gaps

3.2. Gap Effects on the Aerodynamic Drag and Lift Forces

3.3. Baseline Model Flow Structure

3.4. Adjoint Aerodynamic Shape Optimization of the Vehicle

3.5. Optimized Model Performance with Various Suspension Gaps

3.6. The Effect of the Optimization Process on the Kantrowitz Limit

4. Discussion and Implications

4.1. Verified Numerics Support the Design Claims

4.2. Headline Performance with System-Level Meaning

4.3. Impacts on Hyperloop Design

- (i)

- Power and energy: At fixed cruise speed, P = D·V; therefore, a 27.5% drag cut implies a comparable reduction in required propulsive power. For a given duty cycle, it reduces energy per km and can shrink power-electronics margins. (See Section 3.4; Figure 19, Figure 20 and Figure 21 for the drag trends that underpin this mapping.)

- (ii)

- Tube and suspension sizing: Lowering the critical gap from d/D ≈ 0.025–0.033 to ≈0.008 widens the safe-gap envelope (Figure 20), enabling smaller clearances without encountering choking. This can relax tube-diameter and suspension-mass requirements at the system level (Section 3.4).

- (iii)

- Stability margins: By mitigating shock-induced lift excursions near the wall (Figure 13, Figure 15 and Figure 16), the optimized shape improves static stability in near-critical gaps (Section 3.2 and Section 3.3), reducing risk of wall strikes and easing control-law demands.

- (iv)

- Manufacturability & integration: The aft-body updates are compatible with composite lay-up and ±2 mm tooling tolerances; integration with maglev suspensions and linear motors is straightforward because the optimization acts on outer mold lines, not on the levitation/propulsion hardware.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Vehicle area | |

| Tube area | |

| a | Speed of sound |

| b | Vehicle jet exit diameter |

| Cp | Specific heat at constant pressure |

| d | Gap distance between the vehicle and the taube wall |

| D | Drag force |

| Dv | Vehicle diameter |

| Knudsen number | |

| Vehicle’s length | |

| M | Mach number |

| Mass flow rate | |

| Operating pressure | |

| Free stream pressure | |

| Nozzle exit pressure | |

| R | Gas constant |

| Re | Reynolds number |

| T | Temperature |

| Jet velocity | |

| Free stream velocity | |

| x, y, z | Coordinate system |

| Blockage ratio = | |

| Specific heat for ideal air | |

| ρ | Flow density |

| Jet core inclination angle | |

| Wall shear stress |

References

- Raghunathan, R.S.; Kim, H.D.; Setoguchi, T. Aerodynamics of High-Speed Railway Train. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2002, 38, 469–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givoni, M. Development and Impact of the Modern High-Speed Train: A Review. Transp. Rev. 2006, 26, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaub, F. ESPAS—Global Trends to 2030; European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS): Brussels, Belgium, 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/assets/epsc/pages/espas/index.html (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Hodaib, A.E.; Hashem, M.A. Design and Analysis of a Hyperloop Linear Induction Motor. Bachelor’s Thesis, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, E.C. Vaccum Tube Transportation. U.S. Patent 2,511,979, 20 June 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, W.; Wang, K.; Cheng, A.; Kong, X.; Cao, X.; Li, Q. Air Flow and Differential Pressure Characteristics in the Vacuum Tube Transportation System Based on Pressure Recycle Ducts. Vacuum 2018, 150, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkoumas, K. Hyperloop Academic Research: A Systematic Review and a Taxonomy of Issues. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jang, K.S.; Le, T.T.G.; Lee, K.S.; Ryu, J. Theoretical and Numerical Analysis of Pressure Waves and Aerodynamic Characteristics in Hyperloop System under Cracked-Tube Conditions. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 123, 107458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HYPERLOOP (Noun) Definition and Synonyms|Macmillan Dictionary. Available online: https://www.macmillandictionary.com/dictionary/british/hyperloop (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Musk, E. Hyperloop Alpha. Tesla 2013, 1–58. Available online: https://www.tesla.com/sites/default/files/blog_images/hyperloop-alpha.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Abdulla, M.; Juhany, K.A. A Rapid Solver for the Prediction of Flow-Field of High-Speed Vehicle Moving in a Tube. Energies 2022, 15, 6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, M.M.; Alzhrani, S.; Juhany, K.A. Aerodynamics Analysis of Vehicle Moving in a Tube. In Proceedings of the HiSST: 2nd International Conference on High-Speed Vehicle Science Technology, Bruges, Belgium, 11–15 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, M.S.; Winslow, A.; Iida, M.; Fukuda, T. Rapid Calculation of the Compression Wave Generated by a Train Entering a Tunnel with a Vented Hood: Short Hoods. J. Sound Vib. 2008, 311, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, W.A.; Pope, C.W. A Generalised Flow Prediction Method for the Unsteady Flow Generated by a Train in a Single-Track Tunnel. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1981, 7, 331–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.K.; Kim, K.H.; Kwon, H. bin Aerodynamic Characteristics of a Tube Train. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2011, 99, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Jin, Y.; Kwon, H.; Kim, K. A Study on the Aerodynamic Drag of Transonic Vehicle in Evacuated Tube Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2017, 18, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.S.; Le, T.T.G.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.-S.; Ryu, J. Effects of Compressible Flow Phenomena on Aerodynamic Characteristics in Hyperloop System. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 117, 106970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.G.; Kim, J.; Jang, K.S.; Lee, K.-S.; Ryu, J. Numerical Study of Unsteady Compressible Flow Induced by Multiple Pods Operating in the Hyperloop System. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2022, 226, 105024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Y. Aerodynamic Phenomena and Drag of a Maglev Train Running Dynamically in a Vacuum Tube. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 096111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Qin, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, T. Aerodynamic Characteristics of the Evacuated Tube Maglev Train Considering the Suspension Gap. Int. J. Rail Transp. 2022, 10, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W. Effect of Tracks on the Flow and Heat Transfer of Supersonic Evacuated Tube Maglev Transportation. J. Fluids Struct. 2021, 107, 103413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, W. Effect of cross passage on aerodynamic characteristics of super-high-speed evacuated tube transportation. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2021, 211, 104562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opgenoord, M.M.J.; Caplan, P.C. Aerodynamic Design of the Hyperloop Concept. AIAA J. 2018, 56, 4261–4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opgenoord, M.M.J.; Caplan, P.C. On the Aerodynamic Design of the Hyperloop Concept. In Proceedings of the 35th AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 5–9 June 2017; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath, N.; Maloo, T.; Ramesh, P.; Agarwal, D. Numerical Investigation and Multi-Objective Optimization of the Aerodynamics of a Hyperloop Pod. In Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo, J.; Dolz, V.; Navarro, R.; Pallás, B.; Torres, G. Methodology for a Numerical Multidimensional Optimization of a Mixer Coupled to a Compressor for Its Integrationin a Hyperloop Vehicle. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stannard, A.; Qin, N. Hybrid Mesh Deformation for Aerodynamic-Structural Coupled Adjoint Optimization. AIAA J. 2022, 60, 3438–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.C.; Yang, Z.M.; Zhang, L.; Li, R. Adjoint Optimization Method for Head Shape of High- Speed Maglev Train. J. Appl. Fluid. Mech. 2021, 14, 1839–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Paniagua, J.; García, J. Aerodynamic Surrogate-Based Optimization of the Nose Shape of a High-Speed Train for Crosswind and Passing-by Scenarios. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2019, 184, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.G.; Kim, J.; Cho, M.; Ryu, J. Effects of Tail Shapes/Lengths of Hyperloop Pod on Aerodynamic Characteristics and Wave Phenomenon. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 131, 107962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, B.K.; Mukherjea, S.K. Aerodynamic Simulation of Evacuated Tube Transport Trains with Suction at Tail. ASME Int. Mech. Eng. Congr. Expo. Proc. (IMECE) 2014, 12, V012T15A036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, M.; Alzhrani, S.; Juhany, K.A.; AlQadi, I. Application of Adjoint Aerodynamics Optimization for a High-Speed Vehicle Moving in a Tube. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2772, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stine, H.A.; Wanlass, K. Theoretical and Experimental Investigation of Aerodynamic-Heating and Isothermal Heat-Transfer Parameters on a Hemispherical Nose with Laminar Boundary Layer at Supersonic Mach Numbers; Ames Aeronautical Laboratory: Moffett Field, CA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Menter, F.R.; Matyushenko, A.; Lechner, R. Development of a Generalized K-ω Two-Equation Turbulence Model. In Notes on Numerical Fluid Mechanics and Multidisciplinary Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 142, pp. 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F.R.; Matyushenko, A. Generalized k–ω (GEKO) Two-Equation Turbulence Model. AIAA J. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.J.; Connolly, D.P.; de Boer, G.; Shahpar, S.; Hinchliffe, B.; Gilkeson, C.A. Confined Transonic Aerodynamics: From Rifle Bullets to Hyperloop Vehicles. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation Forum and ASCEND 2024, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 29 July–2 August 2024; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, A.J.; Connolly, D.P.; de Boer, G.; Shahpar, S.; Hinchliffe, B.; Gilkeson, C.A. A Review of Hyperloop Aerodynamics. Comput. Fluids 2024, 273, 106202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautrup, B. Continuous Matter. In Physics of Continuous Matter; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F.; Lechner, R.; Matyushenko, A. Best Practice: Generalized k-Omega (GEKO) Two-Equation Turbulence Modeling in Ansys CFD. AIAA J. 2021, 63, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, K.; Chin, J.; Peng, A.; Summers, C.; Nguyen, G.; Oberlander, A.; Sakib, G.; Sharifrazi, N.; Heath, C.; Gray, J.; et al. Conceptual Feasibility Study of the Hyperloop Vehicle for Next-Generation Transport. In Proceedings of the AIAA SciTech Forum—55th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Grapevine, TX, USA, 9–13 January 2017; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.S.; Mader, C.A.; Kenway, G.K.W.; Martins, J.R.R.A. Modeling Boundary Layer Ingestion Using a Coupled Aeropropulsive Analysis. J. Aircr. 2018, 55, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzozero, M.; Sato, Y.; Sayed, M.A. Aerodynamic Study of a Hyperloop Pod Equipped with Compressor to Overcome the Kantrowitz Limit. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2021, 218, 104784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Ding, G.; Wang, Y.; Niu, J. Aeroheating and Aerodynamic Performance of a Transonic Hyperloop Pod with Radial Gap and Axial Channel: A Contrastive Study. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2021, 212, 104591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Sui, Y.; Yu, Q.; Cao, X.; Yuan, Y. Numerical Study on the Impact of Mach Number on the Coupling Effect of Aerodynamic Heating and Aerodynamic Pressure Caused by a Tube Train. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2019, 190, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Wang, T.; Qian, B.; Qin, B.; Lu, Y. Aerodynamic Noise Simulation and Quadrupole Noise Problem of 600 km/h High-Speed Train. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 124866–124875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Gong, C.; Gu, L. Three-Dimensional CST Parameterization Method Applied in Aircraft Aeroelastic Analysis. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2017, 2017, 1874729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Zhu, Z. Vehicle Aerodynamic Optimization: On a Combination of Adjoint Method and Efficient Global Optimization Algorithm. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars—Mech. Syst. 2019, 12, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, J.; Mader, C.A.; Yildirim, A.; Martins, J.R.R.A. Robust Aerodynamic Shape Optimization—From a Circle to an Airfoil. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 87, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.R.R.A. Aerodynamic Design Optimization: Challenges and Perspectives. Comput. Fluids 2022, 239, 105391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.R.R.A.; Lambe, A.B. Multidisciplinary Design Optimization: A Survey of Architectures. AIAA J. 2013, 51, 2049–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.R.R.A.; Ning, A. Engineering Design Optimization; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; ISBN 9781108833417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.R.R.A. Perspectives on Aerodynamic Design Optimization. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2020 Forum, Orlando, FL, USA, 6–10 January 2020; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, A.; Vassberg, J.C. Computational Fluid Dynamics for Aerodynamic Design: Its Current and Future Impact. In Proceedings of the 39th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, NV, USA, 8–11 January 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, E.J.; Anderson, W.K. Aerodynamic Design Optimization on Unstructured Meshes Using the Navier–Stokes Equations. J. Aircr. 2012, 37, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramanzini, J.-R. Adjoint-Based Airfoil Shape Optimization in Transonic Flow. Master’s Thesis, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, MO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, A. Aerodynamic Shape Optimization Using Adjoint Method. In Proceedings of the COBEM2003, 17th International Congress of Mechanical Engineering, São Paulo, Brazil, 11–14 November 2003; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, M.B.; Pierce, N.A. An Introduction to the Adjoint Approach to Design. Flow Turbul. Combust. 2000, 65, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Kenway, G.K.W.; Martins, J.R.R.A. Aerodynamic Shape Optimization Investigations of the Common Research Model Wing Benchmark. AIAA J. 2015, 53, 968–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhász, I. A NURBS Transition between a Bézier Curve and Its Control Polygon. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2021, 396, 113626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othmer, C. Adjoint Methods for Car Aerodynamics. J. Math. Ind. 2014, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halila, G.L.; Martins, J.R.; Fidkowski, K.J. Adjoint-Based Aerodynamic Shape Optimization Including Transition to Turbulence Effects. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 107, 106243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenMDAO OpenMDAO XDSM. Available online: https://github.com/onodip/OpenMDAO-XDSM (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Liu, C.; Zhou, G.; Shyy, W.; Xu, K. Limitation Principle for Computational Fluid Dynamics. Shock Waves 2019, 29, 1083–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Niu, J.; Ricco, P.; Yuan, Y.; Yu, Q.; Cao, X.; Yang, X. Impact of Vacuum Degree on the Aerodynamics of a High-Speed Train Capsule Running in a Tube. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2021, 88, 108752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Operating Pressure | 10,000 | |

| Operating Temperature | 300 K | |

| Vehicle’s Diameter (D) | 3.0 m | |

| Tube Diameter | 5.0 m | |

| Vehicle’s Length | 42.0 m | |

| Vehicle’s Mach number | 0.5–0.7 | |

| Baseline Design Blockage Ratio | 0.36 | |

| Gap Distance | 25–300 mm |

| Mach Number | (kg/s) |

|---|---|

| 0.5 | 107 |

| 0.7 | 150 |

| Function or Variable | Description | Quantity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimize | Drag force | ||

| with respect to | coordinate of FFD points | 250 | |

| Total design variables | 250 | ||

| subject to | Thrust constraint | 1 | |

| Minimum-tail/nose exit jet radius constraint | 2 | ||

| Minimum Nose/tail part length | 2 | ||

| Design variable bounds | 1 | ||

| Total constraints | 256 | ||

| Grid Level | Grid Size (Elements) | Element Size | Y+ | Drag, (N) | Error, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse | 2,405,210 | 10 mm | ~10 | 9920 | 2.27% |

| Medium | 8,159,310 | 7.5 mm | ~5 | 10,210 | 0.59% |

| Fine | 16,159,310 | 2.5 mm | ~1 | 10,150 | 0.00% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdulla, M.M.; Alzhrani, S.; Juhany, K.; AlQadi, I. Adjoint Optimization for Hyperloop Aerodynamics. Vehicles 2025, 7, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040160

Abdulla MM, Alzhrani S, Juhany K, AlQadi I. Adjoint Optimization for Hyperloop Aerodynamics. Vehicles. 2025; 7(4):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040160

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdulla, Mohammed Mahdi, Seraj Alzhrani, Khalid Juhany, and Ibraheem AlQadi. 2025. "Adjoint Optimization for Hyperloop Aerodynamics" Vehicles 7, no. 4: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040160

APA StyleAbdulla, M. M., Alzhrani, S., Juhany, K., & AlQadi, I. (2025). Adjoint Optimization for Hyperloop Aerodynamics. Vehicles, 7(4), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040160