Structural Dynamics of E-Bike Drive Units: A Flexible Multibody Approach Revealing Fundamental System-Level Interactions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theory of Flexible Multibody Dynamics

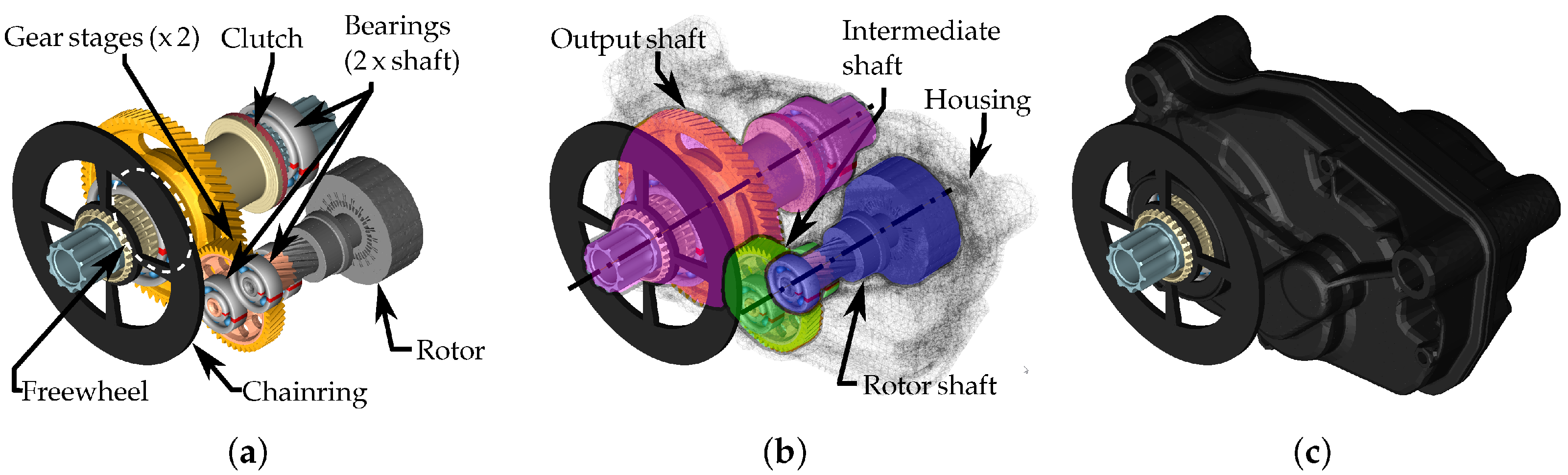

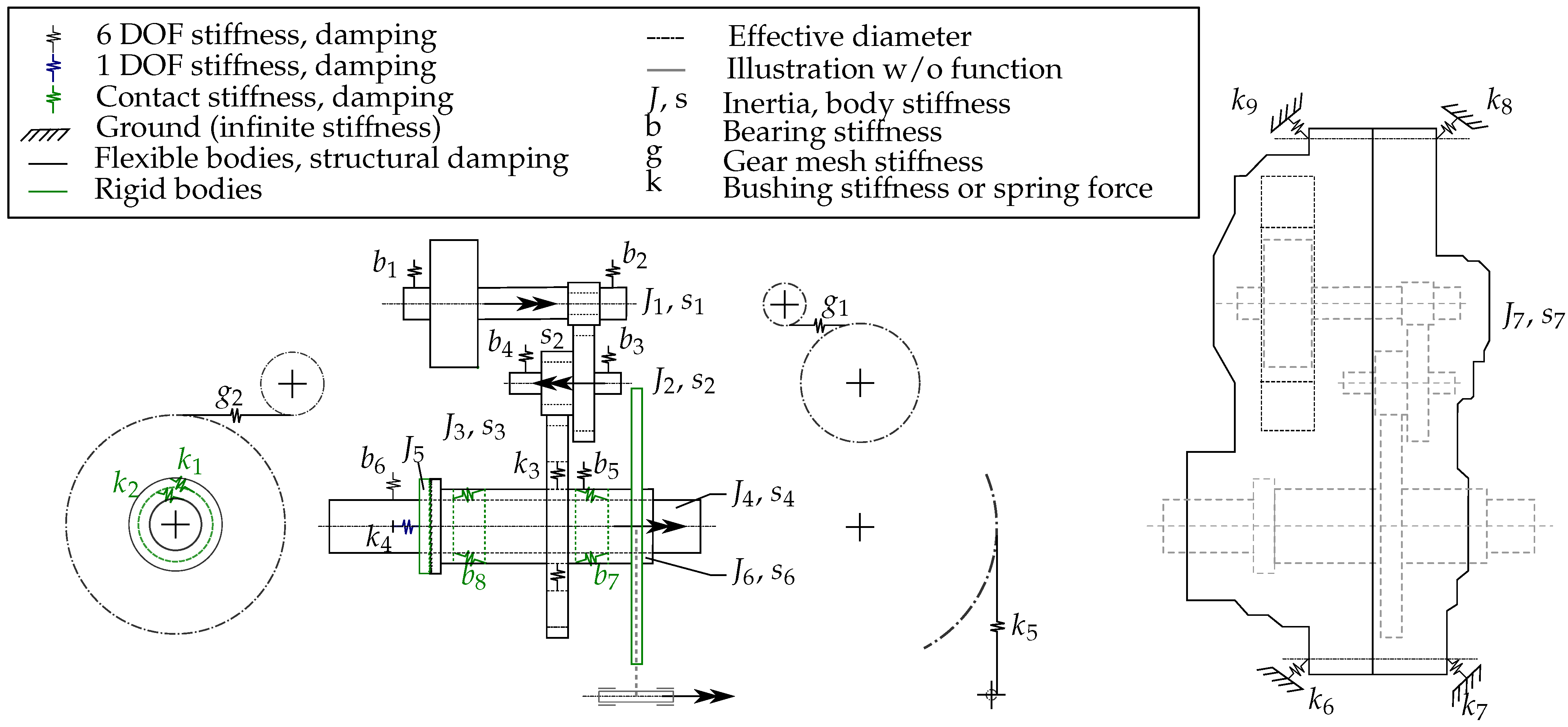

2.2. Topology and Modelling

2.3. Dynamic System Relations

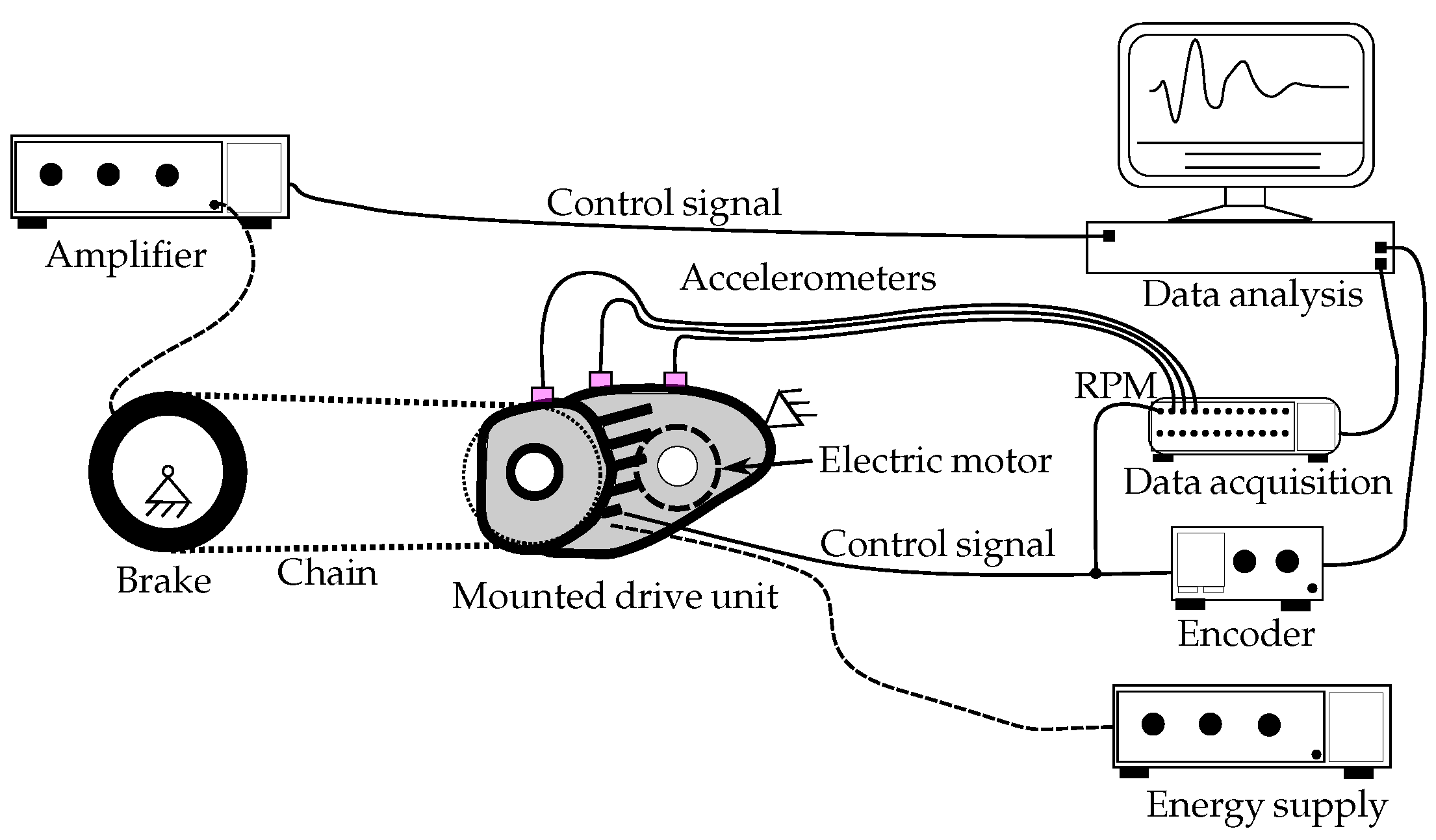

2.4. Test Environment

3. Results and Discussion

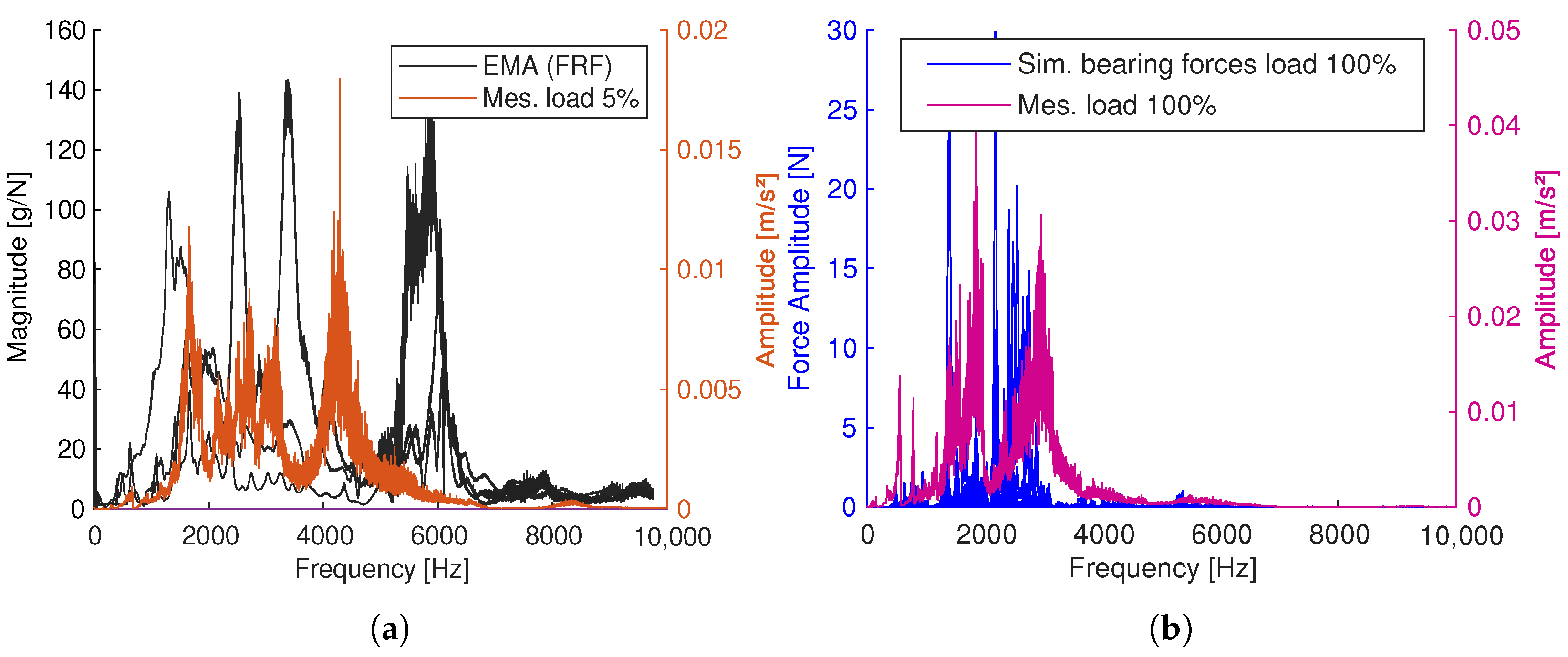

3.1. Dynamics

3.2. Mode Shapes

3.3. Torsional Response Behaviour

3.4. Relevant Frequency Range

3.5. Modelling Restrictions

- 1.

- The chain is simplified by considering only its stiffness, which neglects both the resonances from chain modes and the influence of the mass moment of inertia. The flexibility of the two chainrings is disregarded as well as the precise dynamics of the brake, which is simply constrained by a given rotational motion. This is assumed valid, since the chain stiffness contributes to a decoupling from the drivetrain, while the dynamic behaviour of the brake (and downstream systems) is of no interest.

- 2.

- The gear stage modelling approach substitutes the tooth geometry of the gear bodies with rigid gear rims on which the surrogate models of the flexible teeth are employed. By this, some degrees of freedom for the modal representation of the gear body may be constrained by the artificially employed rigidity of the coupling interface nodes. This is particularly relevant in the present modelling of the very thin-walled gear bodies (see Appendix A.5), whereas the rigidity influence of the coupling nodes at thicker gear bodies is negligible.

- 3.

- The ball bearings are based on a surrogate stiffness, which is quasi-statically exploited. This approach simplifies the rolling behaviour of the balls and neglects elastohydrodynamic contact. Since the dynamic system behaviour of the e-bike drive unit contains a maximum revolution of 5000 min−1 and the resulting fault is expected to be small, this approach is considered valid. Moreover, due to simplified geometric representation and available nominal values, the precise depiction of the inner geometry may differ, leading to divergent stiffness curves (see Appendix A.6).

- 4.

- The clutch and slide bearings are considered as rigid bodies with contact stiffness. This enhances the computational efficiency but neglects the influence of structural deformations. This may distort the contact behaviour and the resulting stiffness, e.g., visible as deviation in curves from the geometric elastic FEM to the geometric rigid MBD (see Appendix A.2). Also, dry friction is applied, which in this particular case is assumed valid, since the relative velocity of the clutch and slide bearing is zero in theory, as long as the system is engaged. Otherwise, the maximum frequency at the output shaft is very low, e.g., 2 , which corresponds to an almost implausible high rider cadency of 120 min−1.

- 5.

- The frictionally engaged freewheel is substituted by a surrogate stiffness which represents the elasticity of the clamping bodies. The influence of the clamping bodies’ mass is expected to be negligibly low and, hence, attributed to the gear body. The load-dependent stiffness behaviour reflects the actual state of the system, but does not provide a precise representation of the geometric positions of the clamping bodies. This is assumed valid, because the underlying measurement system is similar in geometric installation and operation to the applied system. However, it is conceivable that the gradient of the stiffness curves differs in the spatial directions, dependent on the clamping engagement. Moreover, this approach does not capture slip effects caused by load switches.

- 6.

- Analogous to points number 2 and 7, the shaft assemblies consist of the modal reduced structures using CMS, with a partially implemented surrogate model of the gear tooth flexibility. Due to the geometric linear isotropic material behaviour, the CMS method is well-suited for the shafts, except for the rotor. The rotor exhibits nonlinear behaviour [29,30,31], so either linear-elastic models for each load point would be needed or a nonlinear approach is needed. However, the workflow delivers approximate close mode shapes and natural frequencies after the reduction and gear implementation (see Appendix A.7), assuming it is valid.

- 7.

- The housing is simplified using the component mode synthesis (CMS) via Craig–Bampton and orthonormalisation. The resulting modal representation is linearised at one specific operating point. Hence, potential geometric nonlinearities arising from the load influence are not captured, which might be present due to the complex geometry. Moreover, in the modelling, the two housing segments, including the stator, are tied to each other, neglecting any influence from contact points and joint damping. In the scope of this work, the housing has minor relevance, which becomes evident when comparing the spectrum of the system with rigid and flexible housing approaches (see Appendix A.8), However, this should be taken into account in future work for more precise modelling.

- 8.

- The fixation of the housing to the ground is not mapped properly and substituted by an approximated bushing stiffness. This needs to be further examined, as the rigidity of the fixation significantly influences the possible motion of the entire e-bike drive unit. Deviations towards measurements may result from this contribution.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Mass matrix | |

| Global stiffness matrix | |

| Craig–Bampton stiffness | |

| Bushing stiffness | |

| Global damping matrix | |

| Craig–Bampton damping contribution | |

| Rotation matrix in the inertial frame | |

| Transformation matrix of the bushing into the reference frame | |

| Damping matrix of the bushing | |

| Relative displacement in the bushing between bodies a and b | |

| Relative velocity between the two bodies | |

| Jacobian with respect to rigid coordinates | |

| Jacobian with respect to flexible coordinates | |

| Relative rigid Jacobian of the bushing | |

| Relative flexible Jacobian of the bushing | |

| Frequency-dependent effective stiffness | |

| Stiffness matrix of the bushing | |

| Generalised coordinates | |

| Rigid-body generalised coordinates | |

| Flexible generalised coordinates | |

| Time derivative of rigid coordinates | |

| Time derivative of flexible coordinates | |

| Acceleration of rigid coordinates | |

| Acceleration of flexible coordinates | |

| Rigid part of an eigenvector | |

| Flexible part of an eigenvector | |

| External forces | |

| Coriolis and centrifugal forces | |

| Constraint forces (e.g., from bushings) | |

| Rigid-body translation | |

| Body-fixed coordinates in the undeformed state | |

| Global position of the considered point | |

| Velocity of the point | |

| Acceleration of the point | |

| Mode matrix / spatial shape functions | |

| Craig–Bampton constraint modes | |

| Craig–Bampton fixed-interface modes | |

| Individual shape function in the Rayleigh–Ritz approximation | |

| Elastic displacement at position | |

| Rigid-body motion parameters | |

| Flexible modal coordinates | |

| Circular frequency |

Abbreviations

| Adams | Automated dynamic analysis of mechanical systems |

| AT | Advanced technology |

| CAN | Controller area network |

| CMS | Component mode synthesis |

| CB | Craig–Bampton |

| EMA | Experimental modal analysis |

| FE | Finite element |

| FEM | Finite element method |

| FFRF | Floating frame of reference formulation |

| FRF | Frequency response function |

| HHT | Hilbert–Hughes–Taylor |

| MBD | Multibody dynamic |

| MNF | Modal neutral file |

| MSC | MacNeal-Schwendler corporation |

| RMS | Root means square |

| SQP | Sequential quadratic programming |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

Appendix A.3

Appendix A.4

Appendix A.5

Appendix A.6

Appendix A.7

Appendix A.8

References

- Zweirad-Industrie-Verband (ZIV). Verteilung des Fahrradabsatzes in Deutschland nach Modellgruppen im Jahr 2024. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/6062/umfrage/anteil-der-fahrradmodelle-in-deutschland (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Statista. Elektrofahrräder Weltweit. 2025. Available online: https://de.statista.com/outlook/mmo/mikromobilitaet/fahrraeder/elektrofahrraeder/weltweit (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Bosch eBike Systems. Performance Line CX. 2025. Available online: https://www.bosch-ebike.com/us/products/performance-line-cx (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Amflow. PL Carbon. 2025. Available online: https://www.amflowbikes.com/de/pl-carbon (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Steinbach, K.; Lechler, D.; Kraemer, P.; Groß, I.; Reith, D. A Novel Approach to Predict the Structural Dynamics of E-Bike Drive Units by Innovative Integration of Elastic Multi-Body-Dynamics. Vehicles 2023, 5, 1227–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, K.; Lechler, D.; Kraemer, P.; Groß, I.; Reith, D. Structural dynamic effects of the freewheel-clutch in e-bike drive units using a hybrid measurement and simulation approach. J. Vib. Control 2025, 10775463251344657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnejat, H.; Johns-Rahnejat, P.; Dolatabadi, N.; Rahmani, R. Multi-body dynamics in vehicle engineering. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part K J. Multi-Body Dyn. 2023, 238, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Tang, X.; Jia, T.; Duan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, L. Noise and vibration suppression in hybrid electric vehicles: State of the art and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 124, 109782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 4210; Safety Requirements for Bicycles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- EN 15194; Electrically Power Assisted Cycles. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- DIN 79010; Lastenfahrräder–Sicherheitstechnische Anforderungen und Prüfverfahren. Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V: Berlin, Germany, 2020.

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Virtual manufacturing in Industry 4.0: A review. Data Sci. Manag. 2024, 7, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jans, J.; Wyckaert, K.; Brughmans, M.; Kienert, M.; Van der Auweraer, H.; Donders, S.; Hadjit, R. Reducing Body Development Time by Integrating NVH and Durability Analysis from the Start. In Proceedings of the SAE 2006 World Congress & Exhibition, Detroit, MI, USA, 3–6 April 2006; SAE Technical Paper Series. SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, M.; Drichel, P.; Schröder, M.; Berroth, J.; Jacobs, G.; Hameyer, K. Die Kopplung elektrotechnischer und strukturdynamischer Domänen zu einem NVH-Systemmodell eines elektrischen Antriebsstrangs. Elektrotechnik Informationstechnik 2020, 137, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonisoli, E.; Lisitano, D.; Dimauro, L. Detection of critical mode-shapes in flexible multibody system dynamics: The case study of a racing motorcycle. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 180, 109370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gufler, V.; Wehrle, E.; Zwölfer, A. A review of flexible multibody dynamics for gradient-based design optimization. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2021, 53, 379–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, K.; Lechler, D.; Kraemer, P.; Gross, I.; Reith, D. Efficient parameter identification in nonlinear multi-body dynamics through frequency response and harmonic distortion analysis. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rill, G.; Schaeffer, T.; Borchsenius, F. Grundlagen und Computergerechte Methodik der Mehrkörpersimulation: Vertieft in Matlab-Beispielen, Übungen und Anwendungen; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, R.R.; Bampton, M.C.C. Coupling of substructures for dynamic analyses. AIAA J. 1968, 6, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Lu, N.; Che, R. Dynamic analysis on rigid-flexible coupled multi-body system with a few flexible components. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Quality, Reliability, Risk, Maintenance, and Safety Engineering, Xi’an, China, 17–19 June 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, A.A. Flexible Multibody Dynamics: Review of Past and Recent Developments. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 1997, 1, 189–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Klerk, D.; Rixen, D.J.; Voormeeren, S.N. General Framework for Dynamic Substructuring: History, Review and Classification of Techniques. AIAA J. 2008, 46, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauchau, O.A. Flexible Multibody Dynamics; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F. The Schur Complement and Its Applications; Methods and Algorithms; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Mevada, H.; Patel, D. Experimental Determination of Structural Damping of Different Materials. Procedia Eng. 2016, 144, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, F.; Schmidt, G.; Forrai, L. On the significance of antiresonance frequencies in experimental structural analysis. J. Sound Vib. 1999, 219, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akima, H. A New Method of Interpolation and Smooth Curve Fitting Based on Local Procedures. J. ACM 1970, 17, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, H. Stirnradverzahnung, 2, vollständig überarbeitete auflage ed.; Hanser eLibrary, Hanser Verlag: München, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Siegl, G. Das Biegeschwingungsverhalten von Rotoren, die Mit Blechpaketen Besetzt Sind. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Fasihi, A.; Shahgholi, M.; Kudra, G.; GhandchiTehrani, M.; Awrejcewicz, J. The influence of rotor-stator contact on the nonlinear vibration of an asymmetrical rotor. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 27435–27457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chocholaty, B.; Liu, Y.; Marburg, S. Nonlinear dynamic behavior of a rotor-bearing system considering time-varying misalignment. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 284, 109772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Captured DOF | Reference | Acquisition Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| i Ball bearing | 5 (no torsion) | MSC Adams, Bearing AT | integrated FE preprocessing |

| ii Gear (meshing) | 6 | MSC Adams, Gear AT | integrated FE preprocessing |

| iii Freewheel 1 | 4 (no radial) | see Steinbach et al. [6] | Stiffness extraction |

| iv Bicycle chain | 1 (axial) | see Appendix A.1 | Stiffness extraction |

| v Clutch 2 | 1 (torsion) | Abaqus, MSCSQP | Contact stiffness calculation |

| vi Slide bearings | 2 (radial) | Abaqus, MSCSQP | Contact stiffness calculation |

| vii Structural parts | 6 | Abaqus | FE preprocessing |

| Mode Shape | Frequency [Hz] | Damping [%] | Mode Shape | Frequency [Hz] | Damping [%] | Mode Shape | Frequency [Hz] | Damping [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rigid | 24 | 0.2 | rigid | 1801 | 1.3 | combined | 4506 | 14.2 |

| rigid | 520 | 0.7 | combined | 2050 | 4.6 | damped | 4704 | 50.5 |

| rigid | 546 | 3.2 | combined | 2342 | 2.6 | combined | 5673 | 9.0 |

| rigid | 547 | 0.7 | rigid | 2507 | 3.9 | flexible | 7250 | 1.9 |

| rigid | 614 | 9.5 | rigid | 2535 | 15.3 | damped | 7317 | 96.7 |

| damped | 735 | 99.5 | combined | 3339 | 3.4 | flexible | 7810 | 0.8 |

| rigid | 831 | 1.0 | flexible | 3934 | 4.3 | flexible | 8009 | 1.3 |

| rigid | 1103 | 0.4 | flexible | 3955 | 2.8 | flexible | 8742 | 8.1 |

| rigid | 1459 | 12.6 | damped | 4010 | 86.1 | flexible | 10,568 | 6.0 |

| rigid | 1661 | 1.8 | damped | 4152 | 41.3 | combined | 11,321 | 7.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Steinbach, K.; Lechler, D.; Kraemer, P.; Groß, I.; Reith, D. Structural Dynamics of E-Bike Drive Units: A Flexible Multibody Approach Revealing Fundamental System-Level Interactions. Vehicles 2025, 7, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040158

Steinbach K, Lechler D, Kraemer P, Groß I, Reith D. Structural Dynamics of E-Bike Drive Units: A Flexible Multibody Approach Revealing Fundamental System-Level Interactions. Vehicles. 2025; 7(4):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040158

Chicago/Turabian StyleSteinbach, Kevin, Dominik Lechler, Peter Kraemer, Iris Groß, and Dirk Reith. 2025. "Structural Dynamics of E-Bike Drive Units: A Flexible Multibody Approach Revealing Fundamental System-Level Interactions" Vehicles 7, no. 4: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040158

APA StyleSteinbach, K., Lechler, D., Kraemer, P., Groß, I., & Reith, D. (2025). Structural Dynamics of E-Bike Drive Units: A Flexible Multibody Approach Revealing Fundamental System-Level Interactions. Vehicles, 7(4), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040158