2.1. Overview of Current AEB Test Methods

2.1.1. Road Tests

The main type of AEB research is conducting road tests according to certain test scenarios. One of the most popular programs for testing and evaluating these systems is the European New Car Assessment Program (EuroNCAP). In this study, the Euro NCAP protocol was used as a foundational reference for designing the test scenarios due to its global recognition, comprehensive nature, and its role as a de facto industry standard, which facilitates the comparison of our findings with a wide range of published data and vehicle safety ratings.

The tests in the EuroNCAP assessment program are conducted according to the protocols of the provided test scenarios, which are designed to simulate the most common traffic collision situations. The collisions simulated include those with a car, an adult pedestrian, a child, and a cyclist. Car tests, when one car approaches another from behind, consider three scenarios:

- −

The target car is stationary;

- −

The target car is moving slower than the one being tested;

- −

The target vehicle slows down smoothly and abruptly at various distances ahead of the test vehicle [

8].

For the first two scenarios (stationary and slow-moving target vehicle), the tests are repeated for the left and right offset where the centerline of the target vehicle does not match the centerline of the vehicle under test.

Since 2020, testing automatic emergency braking systems has included another mandatory scenario. In this case, the tested car takes a turn (for example, to a secondary road), crossing the path of an oncoming car. During the test, the speeds of the vehicle under test and the approaching target change, with points awarded based on how effectively the AEB system detects an oncoming threat and stops the vehicle in a timely manner. Since during these tests, the sensors of the vehicle being tested can recognize various parts of the leading target vehicle, AEB testing and certification is carried out using a special Global Vehicle Target (GVT) remote-controlled layout shown in

Figure 1.

This target is a prefabricated structure in the form of a passenger car. The IR reflectivity of the surfaces of which is indicated in

Table 1 and should be in the wavelength range from 850 to 910 nm.

In the described tests, the highest score is awarded to those car models whose automatic emergency braking systems can avoid a collision under test conditions or significantly reduce the consequences of an accident. At the same time, it should be borne in mind that the AEB is auxiliary, and the driver bears full responsibility for traffic safety. In more complex situations, the AEB may not be effective enough, or it may be triggered lately and will not completely avoid an accident, but the impact velocity can be significantly reduced. Effective protection of passengers remains critical to prevent serious accident consequences. At low speeds, when testing with a stationary target vehicle, only the operation of the automatic braking function is evaluated. This is because the test scenario simulates a common urban situation where a driver may be inattentive and fail to notice a stationary vehicle ahead until it is too late. In such cases, the system prioritizes immediate automatic braking over a driver warning, as any delay in deceleration could result in a collision that could otherwise be avoided [

9].

When testing scenarios involve high speeds, a different type of target is used. In this case, the target vehicle is a kind of inflatable trailer towed by an auxiliary vehicle. The type of this target is shown in

Figure 2.

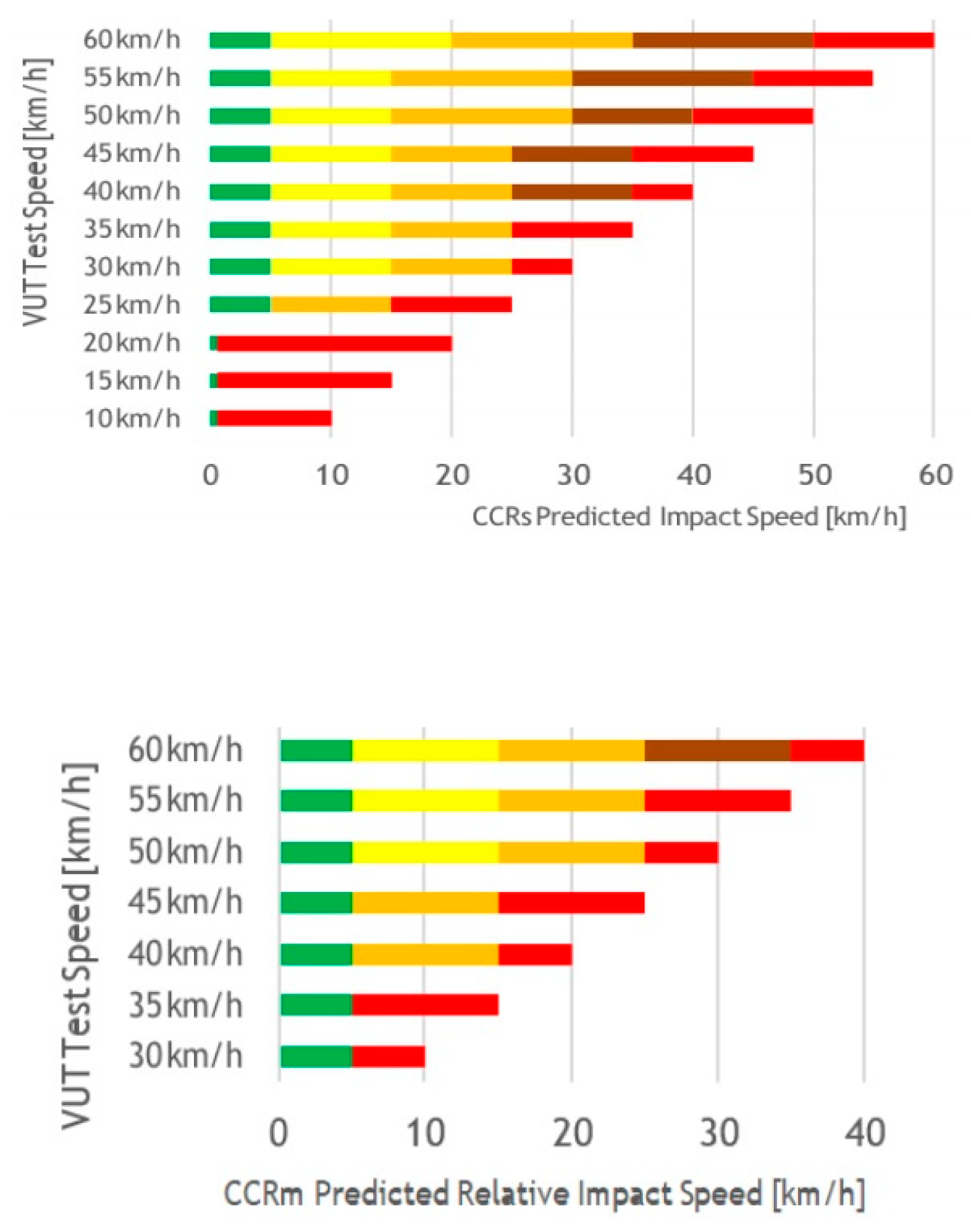

There are 3 types of test scenarios for a moving target car: CCRs, CCRm, and CCRb. Scenarios according to EuroNCAP protocols check the AEB (automatic braking system) function and the FCW (collision warning system) function separately [

10].

Table 2 below presents a gradation of speeds, distances, and decelerations according to these scenarios. The step of the tested function response speeds is 10 km/h. CCRs scenarios involve simulating a collision with a stationary target vehicle. CCRm scenarios involve simulating a collision with a uniformly moving target car. CCRb scenarios involve simulating a collision with a moving target vehicle that decelerates.

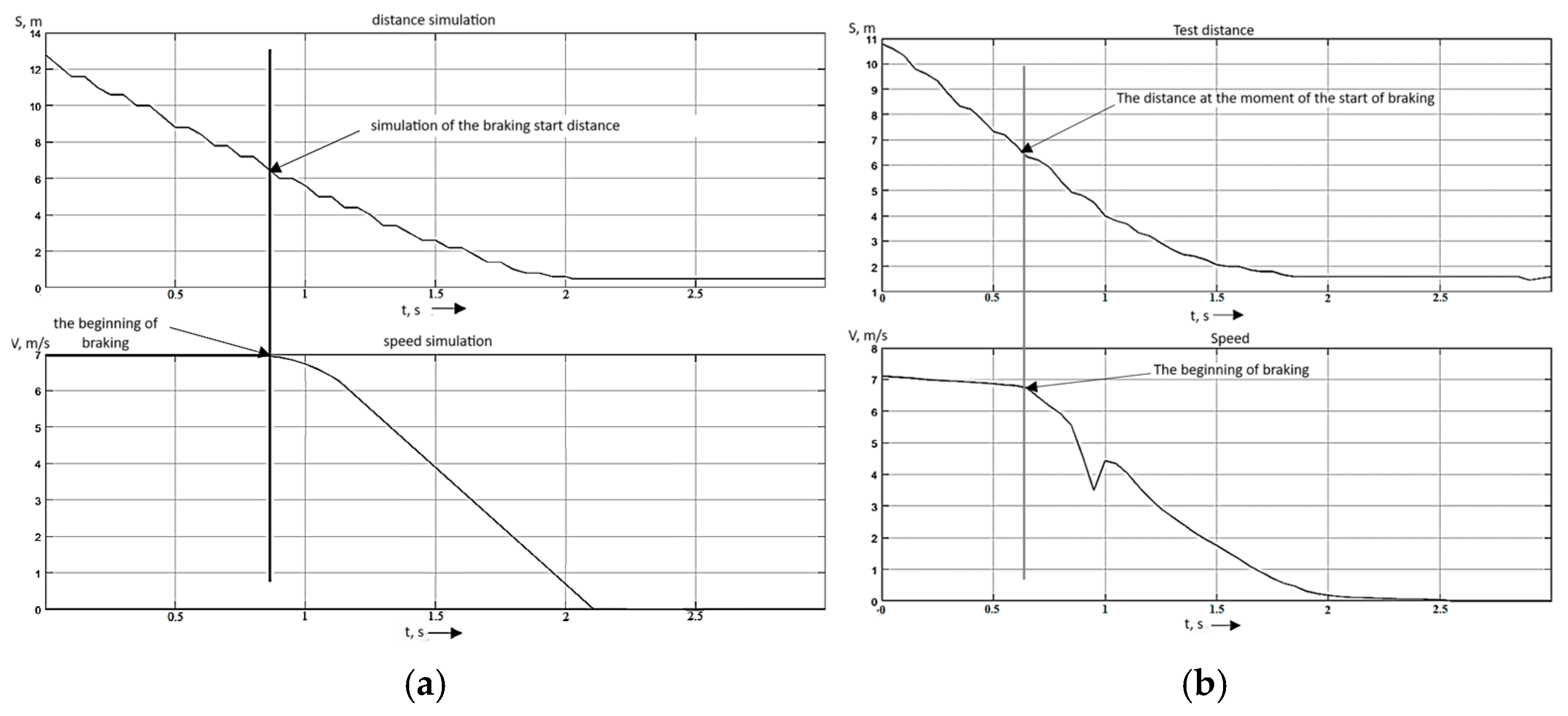

For the experimental validation of the braking distance and timing parameters in this study, the fundamental “vehicle–stationary target” scenario (CCRs) was selected as the primary test condition. This scenario represents a critical and standardized use case for evaluating the core performance of an AEB system in a controlled yet representative environment.

Figure 3 shows a diagram for the gradation depending on the level of collision velocity compensation. For each color of the chart, the following coefficients are applied based on the test results:

Green zone 1.00

The yellow zone is 0.75

The orange zone is 0.50

Brown zone 0.25

Red zone 0.00

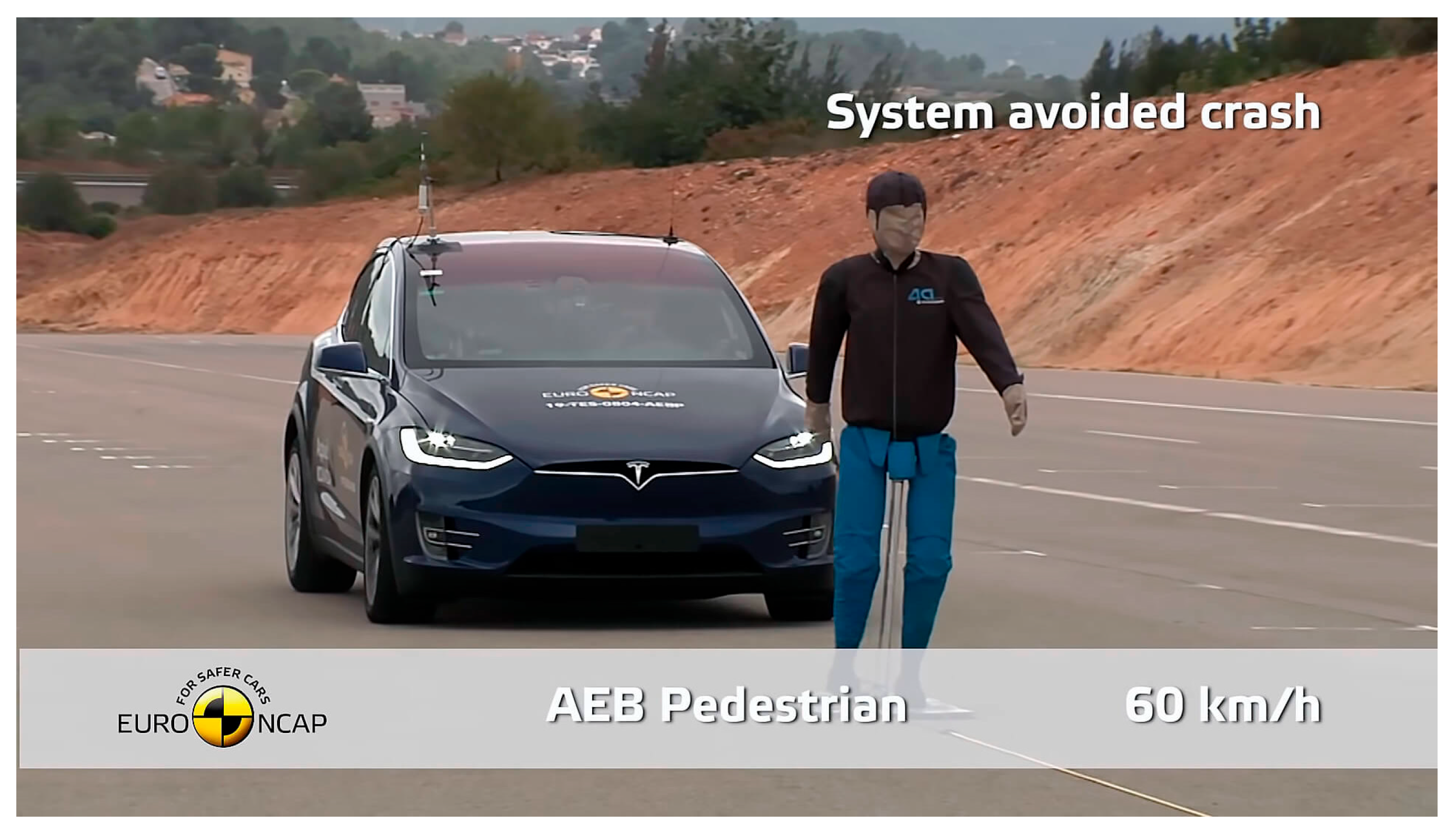

2.1.2. Tests with Pedestrians

To detect pedestrians, EuroNCAP checks three traffic accident scenarios in which a pedestrian crosses the path directly in front of the vehicle being tested. The pedestrian is walking in the same direction as the vehicle. Pedestrian speed is 5 km/h. The speed of the test vehicle is from 20 km/h to 60 km/h (

Figure 4).

There are 3 main scenarios in the Pedestrian Crossing the Road test:

A pedestrian crosses the road from right to left at a speed of 5 km/h;

A pedestrian runs across the road from left to right at a speed of 8 km/h;

A pedestrian or child crosses the road from right to left due to a parked car at a speed of 5 km/h [

11].

The above tests are carried out at night with no street lighting on.

A new type of AEB testing using the EuroNCAP method is to test the system’s operation when performing a turn maneuver at an intersection. The system should detect and prevent a collision with an oncoming car when turning left, as well as avoid hitting a pedestrian when turning right (

Figure 5) [

12].

Car manufacturers participating in the AEB assessment tests according to EuroNCAP protocols finance 20 verification tests, and also have the opportunity to finance additional tests: 10 for AEB and 10 for FCW. The result is determined by the ratio of the test results to the results expected by the automaker initially. This ratio is a correction factor:

The requirements for the external conditions of the EuroNCAP tests are almost ideal for the efficient operation of the system. The tests are carried out on a dry paved surface with a uniform slope of no more than 1% and a high coefficient of adhesion. The ambient temperature should be from 5 °C or above, no precipitation, visibility at least 1000 m [

13].

Undoubtedly, under such external conditions, AEB can have high performance, but in real conditions, and especially in difficult road and climatic conditions in Russian regions, such a testing system cannot measure the real efficiency of the system. Even small changes in weather conditions such as rain can increase the braking distance of a car by several meters, which renders preventing a collision impossible.

Based on the climatic and road conditions of vehicle operation in Russia, a national system for testing automotive safety systems called RuNCAP is being created. A four-party agreement was signed on 9 November 2018 by Rosstandart, NAMI, Autoreview and MADI.

The RuN CAP tests will be conducted voluntarily and according to standards that take into account the specifics of transport operation in the Russian Federation. RuNCAP will form a national rating of vehicles that have passed confirmation of compliance with increased safety requirements [

14,

15,

16].

Tests conducted under the RuNCAP protocols should have sophisticated system tests that are as close as possible to the actual operating conditions of vehicles and account for the specifics of the Russian climate zone.

2.2. The Methodology of Conducting Tests in the Framework of the Current Study

Four stages were included in the tests to evaluate the effectiveness of the AEB algorithm.

At the first stage, we determine the correspondence of coefficients depending on the design features of the brake system under study.

The second stage is testing if the predicted coefficient of adhesion to the bearing surface corresponds to the actual one. The external experimental conditions for testing were chosen so they were as close to everyday operating conditions as possible and included:

- −

A section of road with dry asphalt;

- −

A section of road with wet asphalt;

- −

A section of road with packed snow.

The third stage tested the operation of the AEB, taking into account all the correction factors in soft target collision tests.

The fourth stage tested the operation of the AEB on public roads in various conditions, including in difficult road and climatic conditions of the Far north, to assess the effectiveness and reliability of operation in daily use.

The formula for calculating the stopping distance has the form

In this context, the term “calculated” values refers to the results obtained from this offline mathematical model. These pre-defined calculations are then validated against experimental data, as opposed to being derived from a real-time simulation running concurrently with the test.

This formula contains variables and parameters that depend on the design features.

Where

—the calculated stopping distance.

—the predicted tire–road adhesion coefficient.

—the acceleration due to gravity.

—the brake actuator operation time.

—the vehicle speed at the moment of braking initiation.

—a correction factor for the brake actuator operation.

—the time to achieve steady deceleration.

—a correction factor for the deceleration build-up time.

—the total system response time.

Modeling Assumptions and Rationale.

The mathematical model presented in Equation (1) is a core, real-time capable model representative of the logic used in production AEB electronic control units (ECUs) for immediate risk assessment and braking decision-making. We acknowledge that more elaborate high-fidelity simulations, which incorporate tire characteristics (e.g., Pacejka model), dynamic load shift, and suspension dynamics, are possible and are powerful tools for vehicle design and offline analysis. However, such models are computationally intensive and are not typically deployed for the millisecond-level, online calculations required by a safety-critical system like AEB. The model in Equation (1) was therefore selected for validation because it captures the dominant dynamics—brake system response and tire–road adhesion—that are fundamental to AEB performance prediction. This level of simplification, which also omits secondary factors like air resistance and rolling resistance, is a deliberate and established practice for this application domain, as it balances sufficient accuracy with the computational efficiency and robustness required for real-time operation. The primary goal of this study is not to propose a new complex model, but to validate the practical accuracy of this class of embedded models against real-world data.

The objectives of the experimental study are as follows:

- −

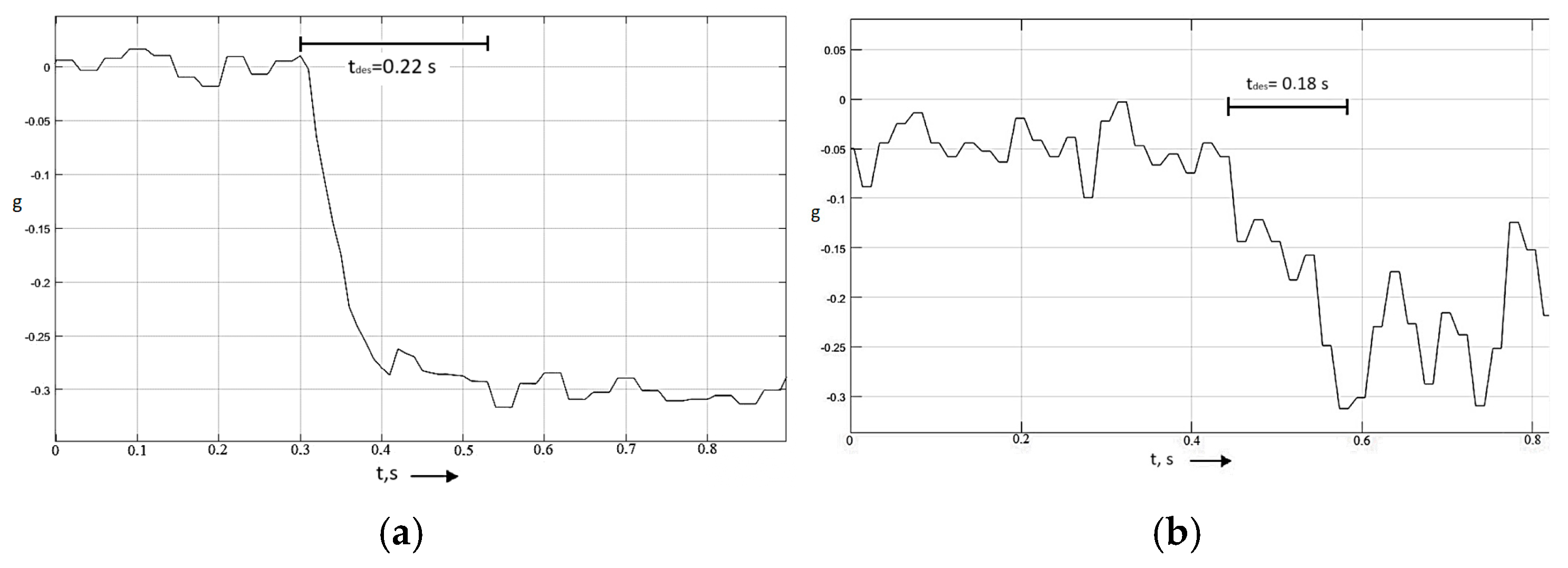

To verify that the estimated operating time of the brake actuator corresponds to the actual one ();

- −

To verify that the actual coefficient of adhesion to the roadway corresponds to the predicted value of ;

- −

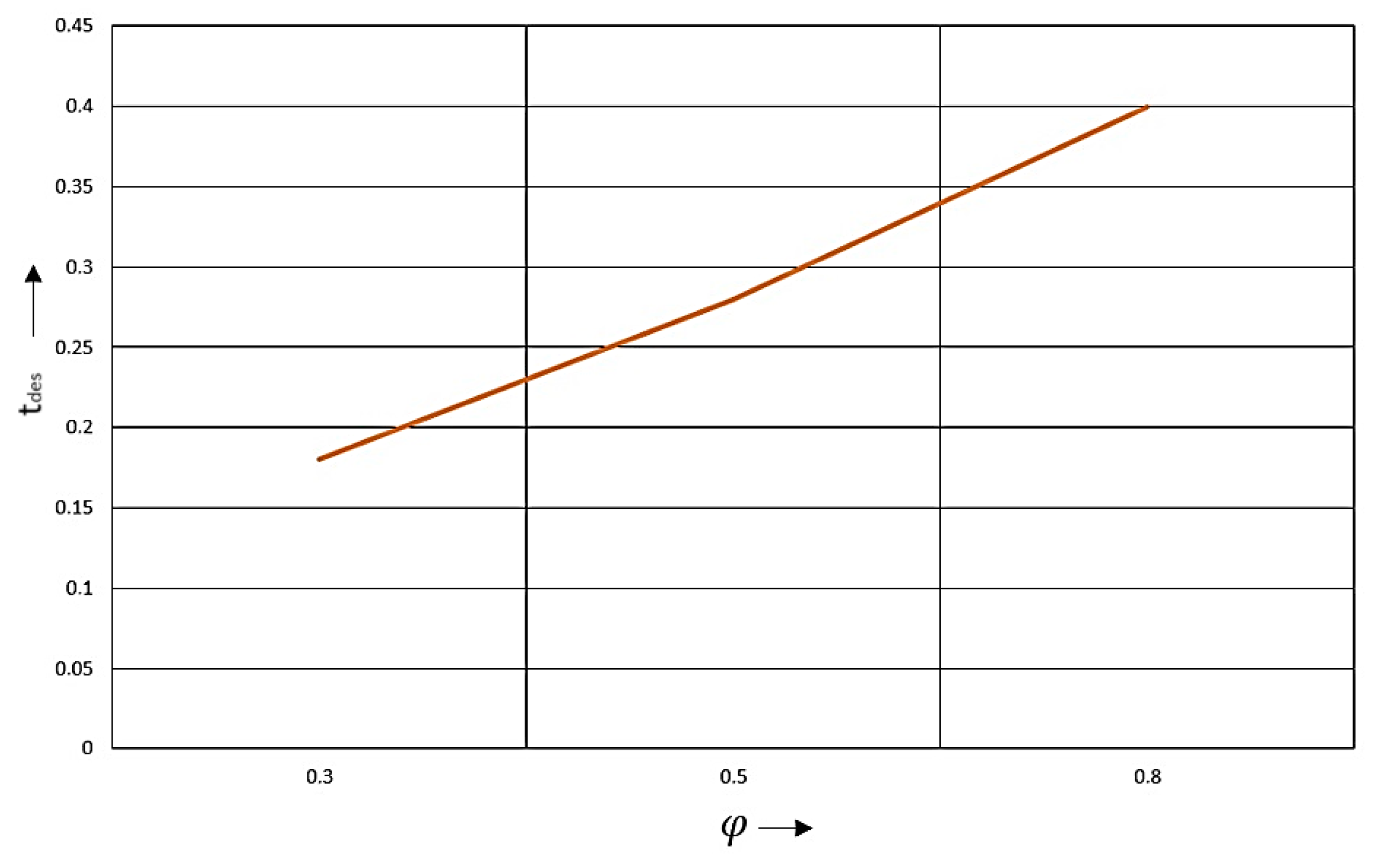

Checking whether the predicted time to achieve steady-state deceleration corresponds to the actual time ();

- −

Verification of the correspondence of the calculated stopping distance to the mathematical model and the stopping distance obtained experimentally.

The following indicators were selected as indicators characterizing the effectiveness of the coupling coefficient prediction algorithm, allowing for an objective comparative assessment:

—speed at which braking was activated;

—measured steady-state deceleration value;

—predicted steady-state deceleration value;

—predicted coefficient of tire adhesion to the bearing surface (calculated using a forecasting algorithm).

—actual coefficient of adhesion of the tire to the bearing surface.

The relationship between deceleration and the adhesion coefficient is fundamental to this assessment. The predicted steady-state deceleration is given by

Conversely, the actual coefficient of adhesion is derived from the measured steady-state deceleration:

It is important to note that this physical model, which equates deceleration to the product of the adhesion coefficient and gravity, is applicable under the key assumption that the braking force is sufficient to operate the tire at or near its adhesion limit, thereby maximizing deceleration. This is the intended operational state for an effective AEB intervention.

The proposed parameters should fully reflect the main performance indicators of the system.

The correspondence of the predicted stopping distance to the actual one under various external conditions, taking into account dynamically changing external factors, was taken as an indicator of the effectiveness of the synthesized AEB functioning algorithm.

The variables and constant parameters used in the braking distance calculation (Equation (1)) and the subsequent analysis are summarized in

Table 3.

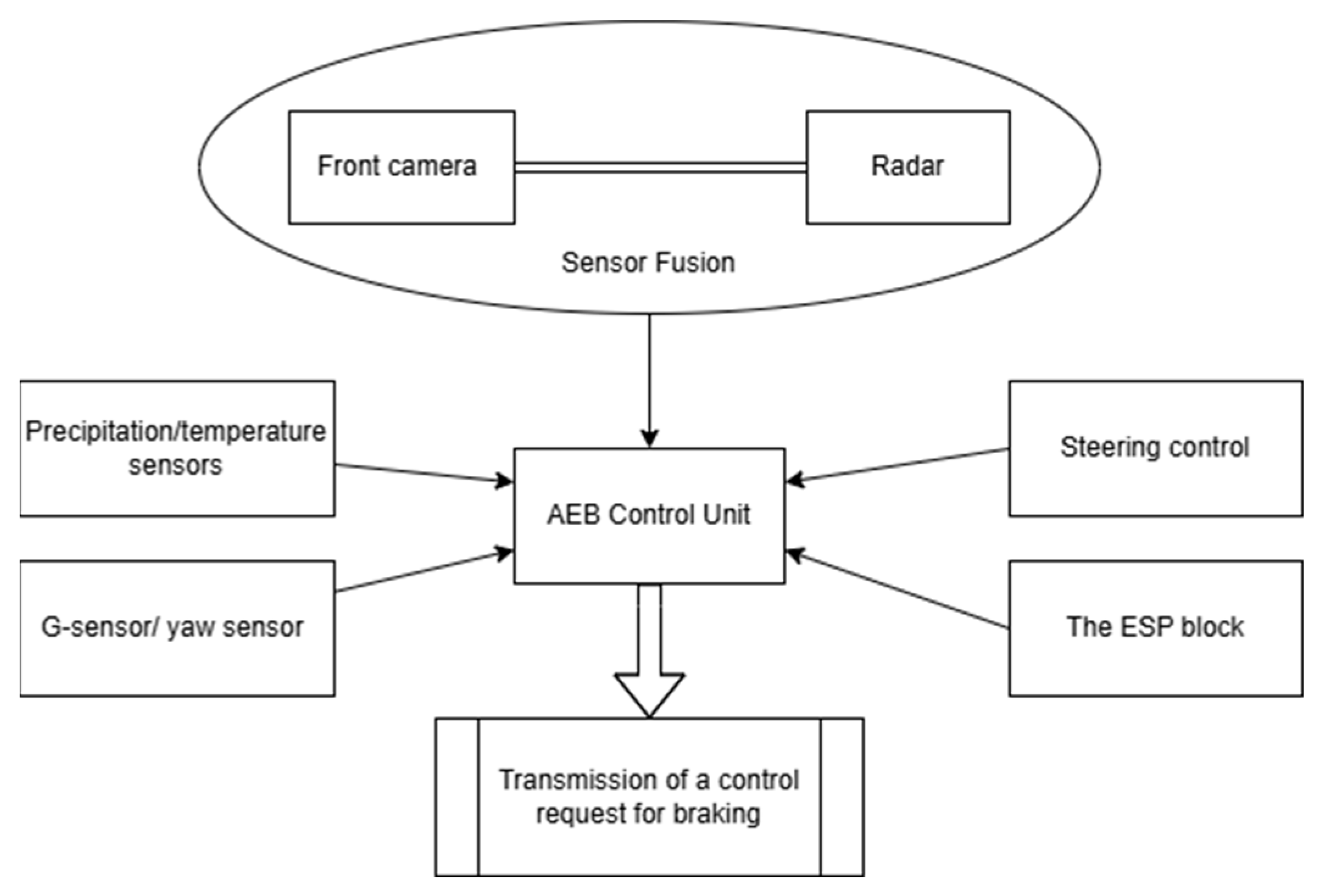

2.2.1. Tire–Road Adhesion Coefficient Forecasting Algorithm

The predicted coefficient of tire adhesion to the bearing surface () is a critical input for the AEB system’s stopping distance calculation. The forecasting algorithm used in this study is based on a rule-based logic that synthesizes data from multiple vehicle sensors in real-time. The algorithm does not rely on a single direct measurement but infers the most likely adhesion level from a set of available signals.

The primary inputs to the forecasting algorithm are the following:

- −

ESP/ABS activity: the frequency and intensity of interventions from the Electronic Stability Program and Anti-lock Braking System. High activity, especially during normal driving, is a strong indicator of a low-adhesion surface (e.g., snow, ice).

- −

Wheel speed sensors: differences in rotational speed between driven and non-driven wheels, indicating wheel slip.

- −

Longitudinal acceleration sensor: the actual deceleration of the vehicle during gentle braking maneuvers, compared to the commanded brake pressure.

- −

Ambient temperature and precipitation data: signals from the rain/light sensor and the external temperature sensor. The presence of precipitation (rain/snow) coupled with low temperatures (near or below 0 °C) directly lowers the initial adhesion estimate.

- −

Wiper status: the intensity of the windshield wiper operation serves as a proxy for rain intensity.

- −

Historical data: the recent history of the aforementioned parameters over the last few seconds of driving.

The algorithm operates by assigning a base value of (typically ~0.8–0.9 for dry asphalt) which is then progressively scaled down by correction factors based on the inputs. For instance, if the ambient temperature is below 2 °C and the rain sensor is active, the base value is significantly reduced. This preliminary estimate is then further refined and validated against the vehicle’s dynamic response (e.g., if the measured deceleration during a minor brake application is lower than expected for the current base value, is adjusted downwards). The final output is a filtered and validated estimate of that is updated continuously and supplied to the AEB control logic.

2.2.2. The Object of Research

The object of the research was one of the working prototypes created within the framework of the Experimental Manufacturing Plant (EMP) of the Russian State Scientific Centre Federal State Unitary Enterprise «NAMI» (

Figure 6). It is important to note that the term “working prototype” here refers to the vehicle platform itself. The AEB system installed on this prototype, however, constitutes a current-generation system. It is implemented using series-production, state-of-the-art hardware components (front radar, front camera, intelligent control unit) and employs algorithms and performance targets that are representative of, and comparable to, those used in modern mass-produced vehicles (

Figure 7). Therefore, the findings of this study are directly relevant to the performance assessment of contemporary AEB technology. The prototype is equipped with a hydraulic brake drive featuring a pre-installed hardware set for Automatic Emergency Braking (AEB).

The characteristics of the test sample are shown in

Table 4.

The test vehicle was equipped with a complete set of automatic emergency braking systems: a front object recognition camera, a front radar, an intelligent driver assistance control unit, and the operation of the vehicle’s standard sensors (rain sensor, wiper intensity, temperature, skid detection sensor, and anti-lock braking system) was checked.

2.2.3. Measuring and Recording Equipment

Since the main parameters required for analysis are the speed and acceleration of the car, one of the most commonly used devices for recording data in this format is the racelogic VBOX. This device has the ability to connect to the CAN bus and has a GPS connection with a refresh rate of up to 100 Hz.

The ESP system is installed on the test vehicle, which has a wide range of parameters: the rotation speed of each wheel, longitudinal and lateral accelerations, vehicle speed, etc. Since the test vehicle has the ability to connect to control units, as well as access to ESP parameters, it is possible to simplify data recording and trial tests were performed to select the recording option. the investigated parameters.

A Vector VN 1630 adapter and a laptop were used to connect to the vehicle CAN bus.

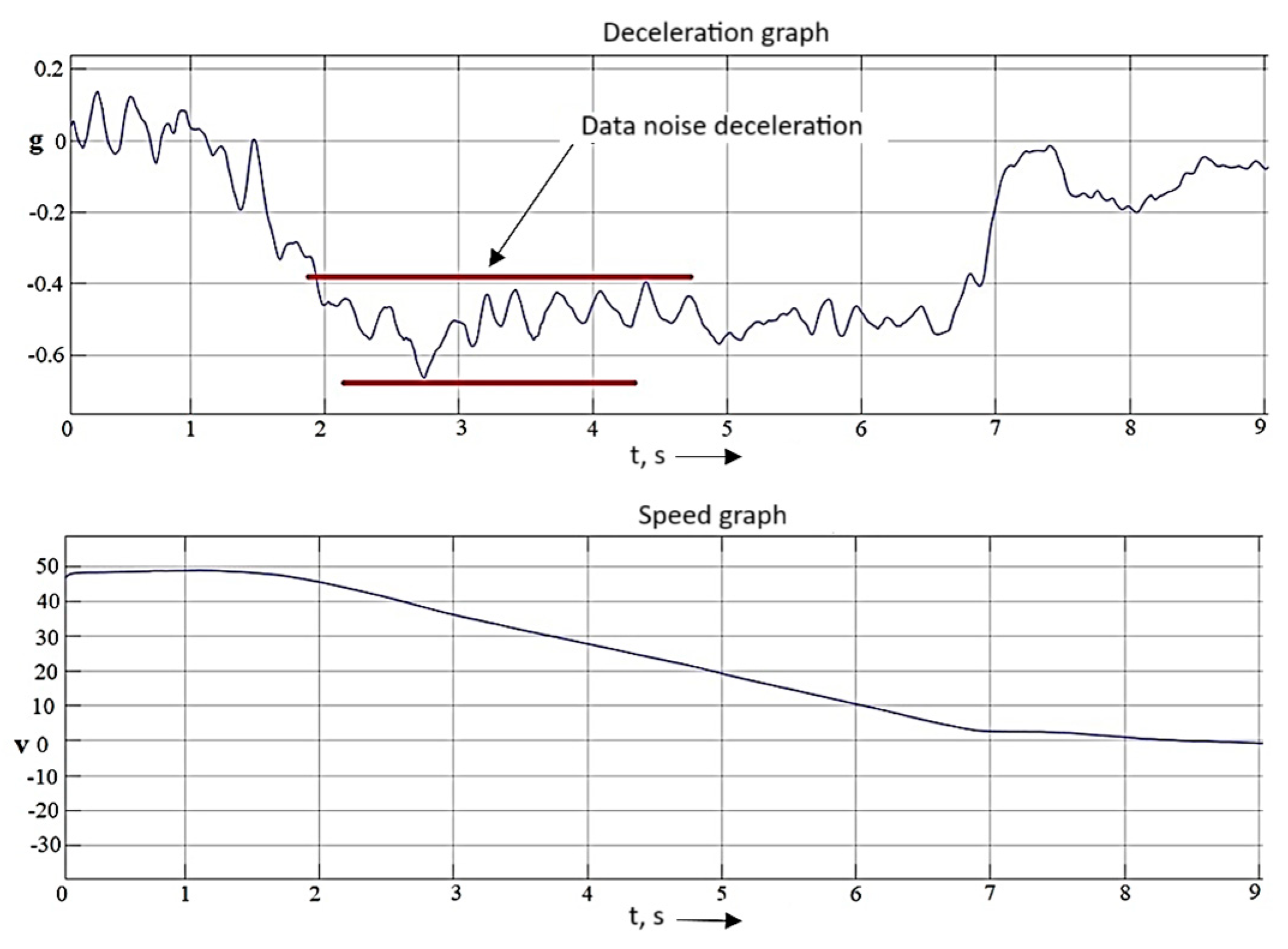

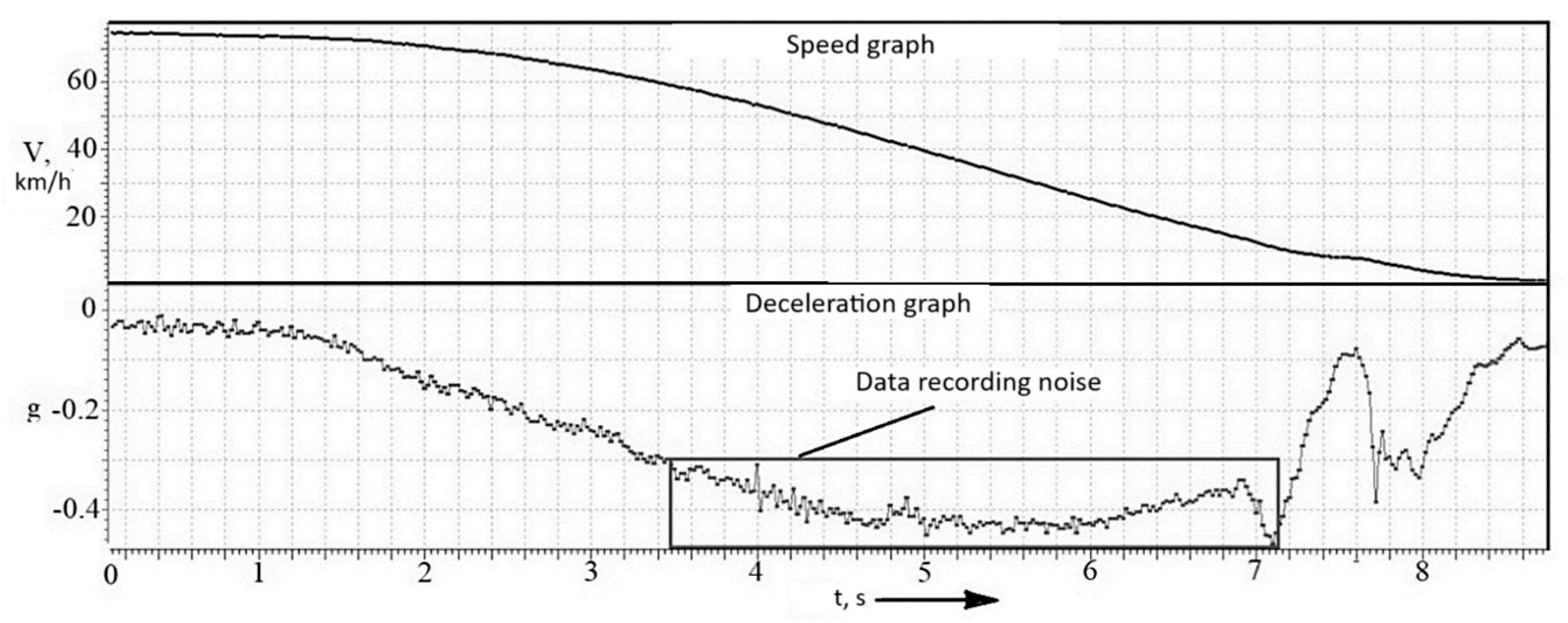

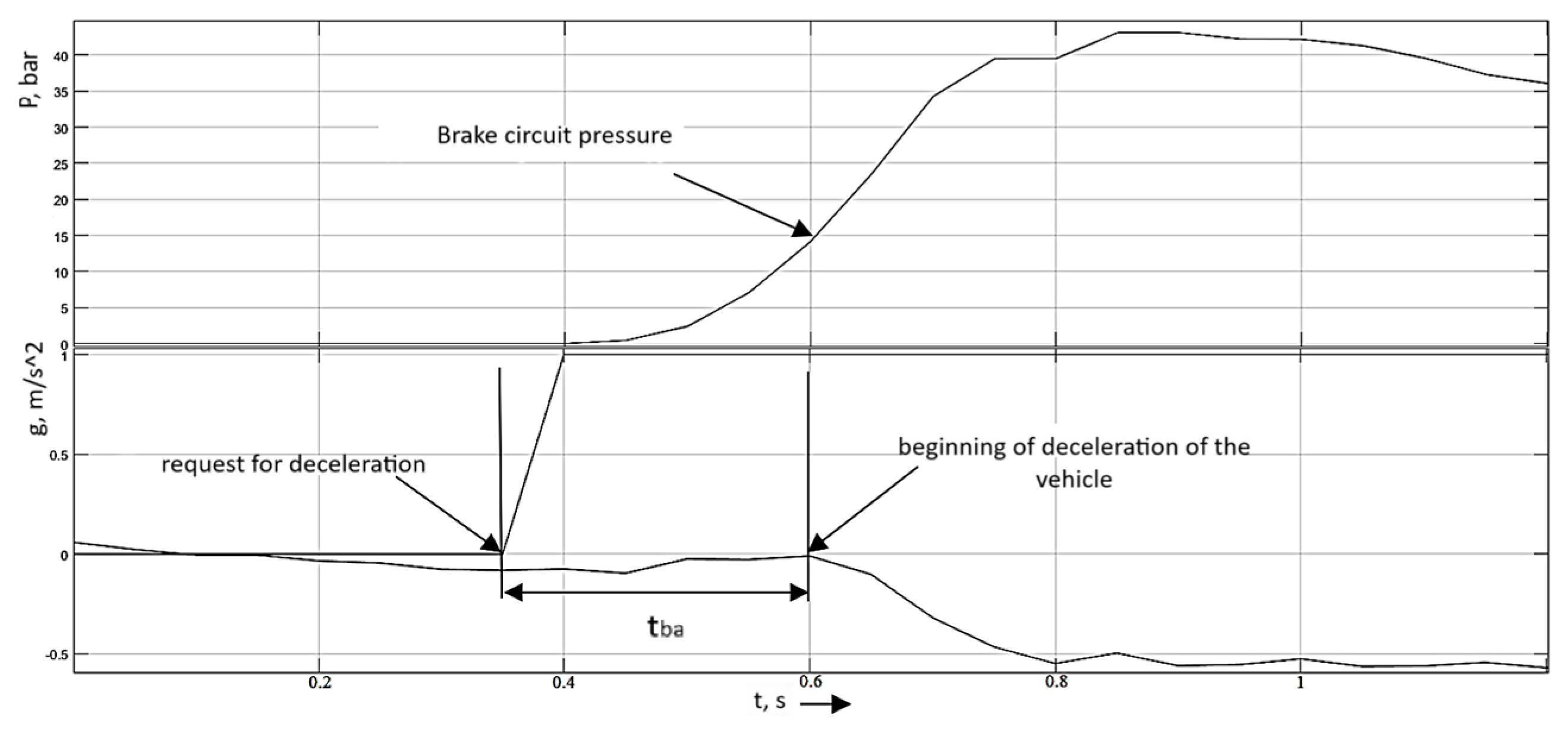

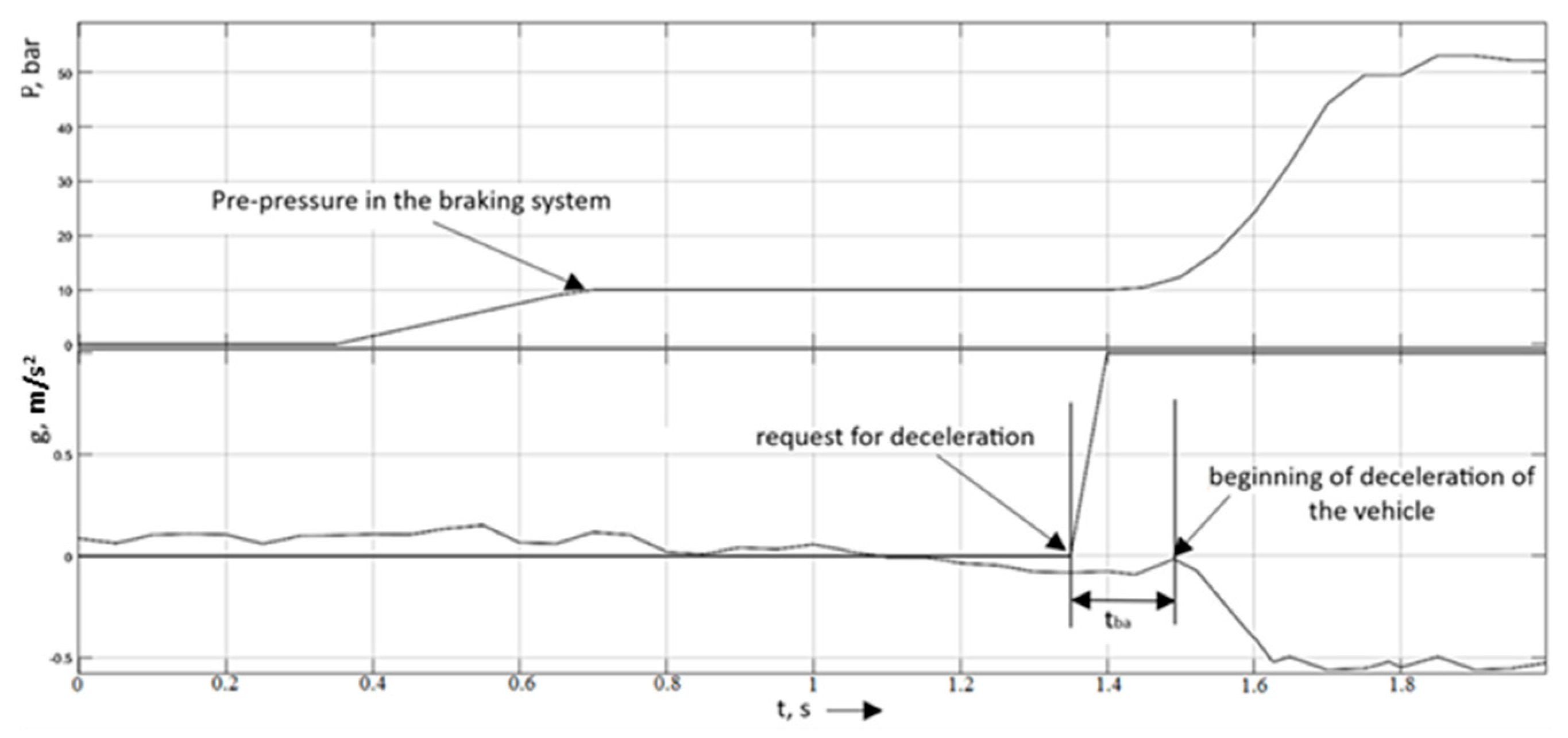

To compare the accuracy of the recorded data and the choice of recording device, braking was performed on dry, flat asphalt at 80 km/h. The deceleration value was chosen as the main criterion for evaluation.

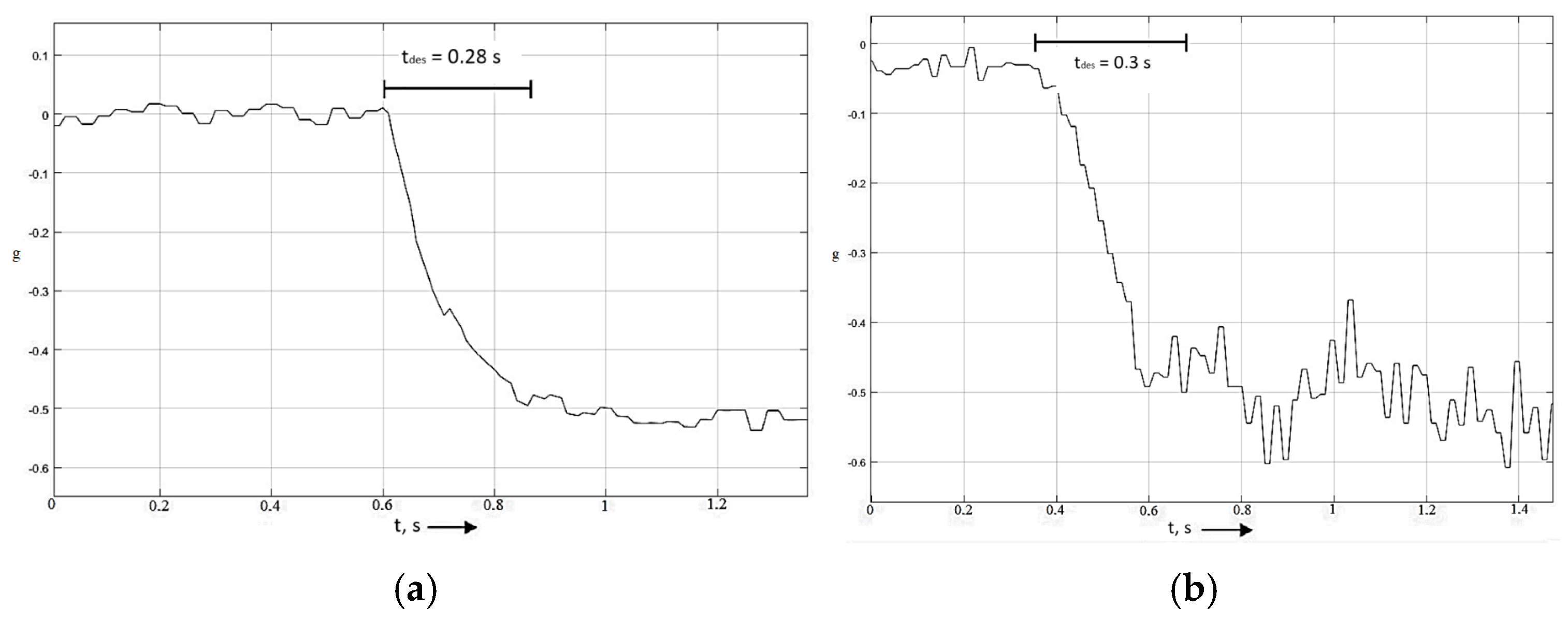

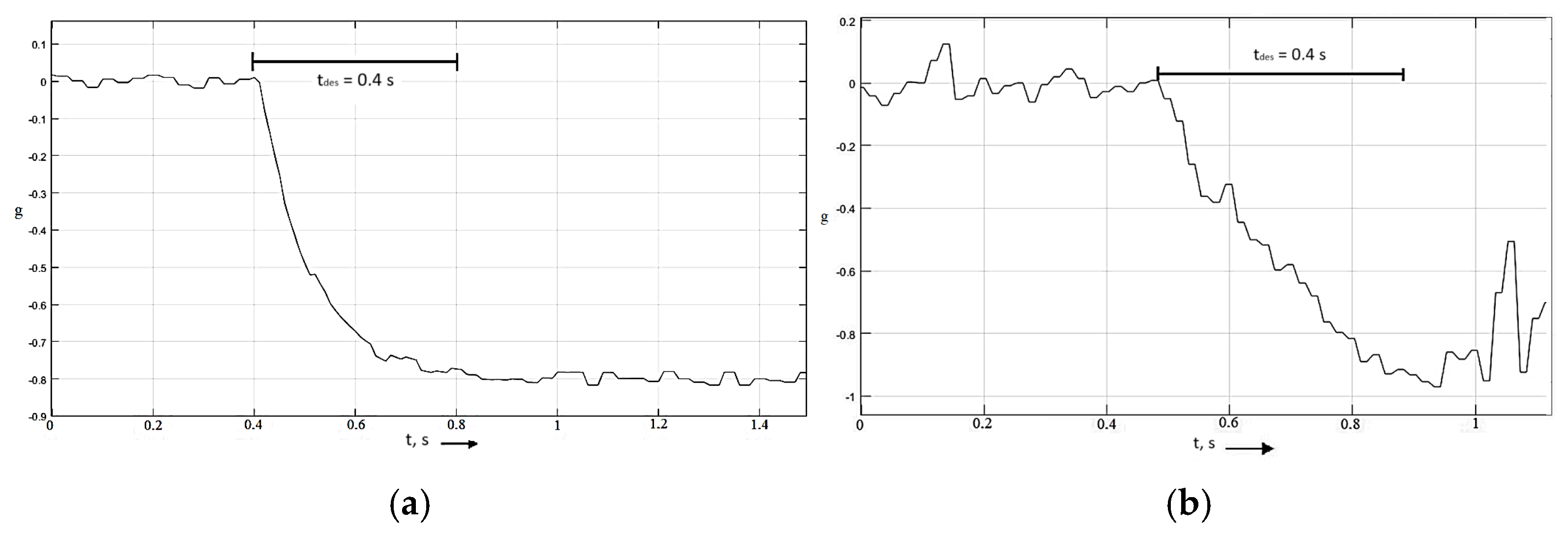

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show graphs of the recorded data. As you can see in the upper graph of

Figure 8, the deceleration value from the racelogic VBOX has a noise value of about 0.2 m/s

2.

Figure 9 shows the deceleration graph recorded from the ESP unit using Vector VN 1630. The noise of the deceleration value is also at the level of 0.2 m/s

2.

Based on the tests of the recording equipment, it was found that the recording of values from the ESP unit has sufficient accuracy to carry out the necessary tests. Based on this, the following equipment was used:

- −

Recording equipment—Vector VN 1630, laptop.

- −

Program for processing recorded data—Canalyzer v 9.0

Registered parameters:

- −

Vehicle speed;

- −

Speeding up the car;

- −

Brake circuit pressure;

- −

Request for braking.

2.2.4. Determination of the Minimum Number of Repeated Experiments

To determine the minimum number of races, a preliminary experiment, consisting of 7 measurements of the recorded values was conducted. Based on the results of preliminary measurements, the minimum number of races was determined so that repetition would allow measurements to be carried out with a confidence probability of at least

Calculation of the standard deviation:

where

is the arithmetic mean of the parameter at a given time:

where

is the value of the parameter in the i-th measurement;

n is the number of trial runs.

The number of repeated experiments is determined by the formula

where

—Coefficient of Student’s t-distribution at confidence probability.

= 0.97,

n = 3,

= 2.57.

To provide the specified accuracy of the experiment, we assume = 3.